Pneumomediastinum

Glenna B. Winnie, Aarthi P. Vemana, Suraiya K. Haider

Air or gas in the mediastinum is called pneumomediastinum.

Etiology

Pneumomediastinum is typically caused by alveolar rupture which can be due to either a spontaneous or traumatic cause. A spontaneous pneumomediastinum can either be primary without an underlying etiology or can occur secondary to an underlying cause. Primary pneumomediastinum can be due to increases in intrathoracic pressure as is seen with a Valsalva maneuver, vomiting, Boerhaave syndrome (esophageal perforation), weightlifting, and choking events. Common causes of secondary pneumomediastinum in children younger than age 7 years are lower respiratory tract infections and asthma exacerbations. Simultaneous pneumothorax is unusual in these patients. Other causes of secondary pneumomediastinum are anorexia nervosa, normal menses, and diabetes mellitus with ketoacidosis. Traumatic causes of pneumomediastinum include both iatrogenic (dental extractions, adenotonsillectomy, high flow nasal cannula therapy, esophageal perforation, and inhalation of helium gas), and non-iatrogenic (inhaled foreign body, penetrating chest trauma, and illicit drug use).

Pathogenesis

According to the Macklin effect , after an intrapulmonary alveolar rupture, air dissects along the pressure gradient through the perivascular sheaths and other soft tissue planes toward the hilum and enters the mediastinum.

Clinical Manifestations

Dyspnea and transient stabbing chest pain that may radiate to the neck are the principal features of pneumomediastinum. Other symptoms may be present and may include globus pharyngeus, abdominal pain, cough, chest tightness, facial swelling, choking, tachypnea, fever, stridor, and sore throat. Pneumomediastinum is difficult to detect by physical examination alone. Subcutaneous emphysema is present in the majority of patients. When present, Hamman sign (a mediastinal “crunch”) is nearly pathognomonic for pneumomediastinum. Cardiac dullness to percussion may be decreased, but the chests of many patients with pneumomediastinum are chronically overinflated and it is unlikely that the clinician can be sure of this finding.

Laboratory Findings

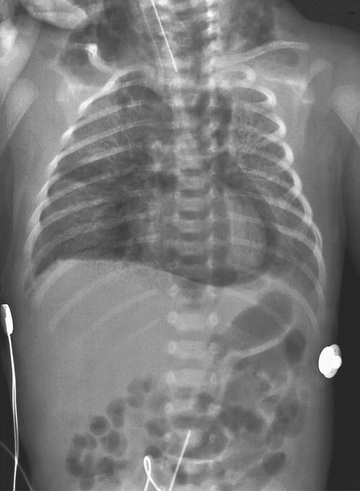

Chest radiography reveals mediastinal air, with a more distinct cardiac border than normal (Figs. 440.1 and 440.2 ). A “spinnaker sail sign” or “angel wing sign” occurs when air deviates the thymus upward and outward, which is seen more often in pediatric patients. On the lateral projection, the posterior mediastinal structures are clearly defined, there may be a lucent ring (“ring sign”) around the right pulmonary artery, and retrosternal air can usually be seen. Vertical streaks of air in the mediastinum and subcutaneous air are often observed (see Fig. 440.1 ). If a pneumomediastinum is clinically suspected, but is not visualized on a chest x-ray, a chest CT can be performed to provide further radiologic evidence.

Treatment

Treatment is directed primarily at the underlying obstructive pulmonary disease or other precipitating condition. Children who have had pneumomediastinum should be screened for asthma. Analgesics are occasionally needed for chest pain. Children can be observed in the emergency room and discharged if stable. They should be cautioned to avoid heavy lifting and the Valsalva maneuver. Hospital admission with supplemental oxygen administration is more common for patients with secondary pneumomediastinum. Rarely, subcutaneous emphysema can cause sufficient tracheal compression to justify tracheotomy; the tracheotomy also decompresses the mediastinum.

Complications

Pneumomediastinum is rarely a major problem in older children because the mediastinum can be depressurized by escape of air into the neck or abdomen. In the newborn, however, the rate at which air can leave the mediastinum is limited, and pneumomediastinum can lead to dangerous cardiovascular compromise or pneumothorax (see Chapters 122.14 and 439 ).