Pheochromocytoma

Perrin C. White

Pheochromocytomas are catecholamine-secreting tumors arising from chromaffin cells. The most common site of origin (approximately 90%) is the adrenal medulla; however, tumors may develop anywhere along the abdominal sympathetic chain and are likely to be located near the aorta at the level of the inferior mesenteric artery or at its bifurcation. They also appear in the periadrenal area, urinary bladder or ureteral walls, thoracic cavity, and cervical region. Ten percent occur in children, in whom they present most frequently between 6 and 14 yr of age. Tumors vary from 1 to 10 cm in diameter; they are found more often on the right side than on the left. In more than 20% of affected children, the adrenal tumors are bilateral; in 30–40% of children, tumors are found in both adrenal and extraadrenal areas or only in an extraadrenal area.

Etiology

Pheochromocytomas may be associated with genetic syndromes such as von Hippel-Lindau disease, as a component of multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndromes MEN2A and MEN2B, and more rarely in association with neurofibromatosis (type 1) or tuberous sclerosis. The classic features of von Hippel-Landau syndrome, which occurs in 1 in 36,000 individuals, include retinal and central nervous system hemangioblastomas, renal clear cell carcinomas, and pheochromocytomas, but kindreds differ in their propensity to develop pheochromocytoma; in some kindreds, pheochromocytoma is the only tumor to develop. Germline mutations in the VHL tumor-suppressor gene on chromosome 3p25-26 have been identified in patients with this syndrome. Mutations of the RET protooncogene on chromosome 10q11.2 have been found in families with MEN2A and MEN2B. Patients with MEN2 are at risk of developing medullary thyroid carcinoma and parathyroid tumors; approximately 50% develop pheochromocytoma, with patients carrying mutations at codon 634 of the RET gene being at particularly high risk. Mutations are present in the NF1 gene on chromosome 17q11.2 in neurofibromatosis type 1 patients.

Pheochromocytomas may occur in kindreds along with paragangliomas, particularly at sites in the head and neck. Such families typically carry mutations in the SDHB , SDHD , and, rarely, the SDHC genes encoding subunits of the mitochondrial enzyme succinate dehydrogenase . These mutations lead to intracellular accumulation of succinate, an intermediate of the Krebs cycle, which inhibits α-ketoglutarate–dependent dioxygenases and results in epigenetic alterations that affect expression of genes involved in cell differentiation. Approximately 50% of tumors with SDHB mutations are malignant.

In addition to associations with other tumors in MEN-2 patients, pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas can occur in association with gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs; the association is termed the Carney-Stratakis dyad) and/or pulmonary chondromas (Carney-Stratakis triad) and adrenocortical tumors. These associations have heterogenous genetic etiologies but often involve mutations in SDH genes.

Clinical Manifestations

Pheochromocytomas detected by surveillance of patients who are known carriers of mutations in tumor-suppressor genes may be asymptomatic. Otherwise, patients are detected owing to hypertension, which results from excessive secretion of metanephrines, epinephrine and norepinephrine. All patients have hypertension at some time. Paroxysmal hypertension should particularly suggest pheochromocytoma as a diagnostic possibility, but in contrast to adults, the hypertension in children is more often sustained rather than paroxysmal. When there are paroxysms of hypertension, the attacks are usually infrequent at first, but become more frequent and eventually give way to a continuous hypertensive state. Between attacks of hypertension, the patient may be free of symptoms. During attacks, the patient complains of headache, palpitations, abdominal pain, and dizziness; pallor, vomiting, and sweating also occur. Seizures and other manifestations of hypertensive encephalopathy may occur. In severe cases, precordial pains radiate into the arms; pulmonary edema and cardiac and hepatic enlargement may develop. Symptoms may be exacerbated by exercise, or with use of nonprescription medications containing stimulants such as pseudoephedrine. Patients have a good appetite but because of the hypermetabolic state may not gain weight, and severe cachexia may develop. Polyuria and polydipsia can be sufficiently severe to suggest diabetes insipidus. Growth failure may be striking. The blood pressure may range from 180 to 260 mm Hg systolic and from 120 to 210 mm Hg diastolic, and the heart may be enlarged. Ophthalmoscopic examination may reveal papilledema, hemorrhages, exudate, and arterial constriction.

Laboratory Findings

The urine may contain protein, a few casts, and occasionally glucose. Gross hematuria suggests that the tumor is in the bladder wall. Polycythemia is occasionally observed. The diagnosis is established by demonstration of elevated blood and 24 hr urinary levels of total metanephrines.

Pheochromocytomas produce norepinephrine and epinephrine. Normally, norepinephrine in plasma is derived from both the adrenal gland and adrenergic nerve endings, whereas epinephrine is derived primarily from the adrenal gland. In contrast to adults with pheochromocytoma in whom both norepinephrine and epinephrine are elevated, children with pheochromocytoma predominantly excrete norepinephrine in the urine. Total urinary metanephrine excretion usually exceeds 300 µg/24 hr. Urinary excretion of metanephrines (particularly normetanephrine) is also increased (see Fig. 592.3 in Chapter 592 ). Daily urinary excretion of these compounds by unaffected children increases with age. Although urinary excretion of vanillylmandelic acid (3-methoxy-4-hydroxymandelic acid), the major metabolite of epinephrine and norepinephrine, is increased, vanilla-containing foods and fruits can produce falsely elevated levels of this compound, which therefore is no longer routinely measured.

Elevated levels of free catecholamines and metanephrines can also be detected in plasma. In children, the best sensitivity and specificity are obtained by measuring plasma normetanephrine using gender-specific pediatric reference ranges, with plasma norepinephrine being next best. Plasma metanephrine and epinephrine are not reliably elevated in children. Additionally, the patient should be instructed to abstain from caffeinated drinks, and to avoid acetaminophen, which can interfere with plasma normetanephrine assays. If possible, the blood sample should be obtained from an indwelling intravenous catheter, to avoid acute stress associated with venipuncture.

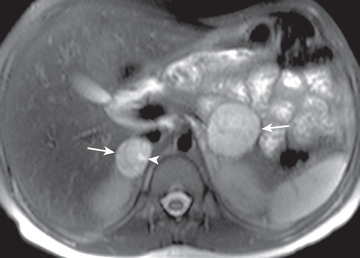

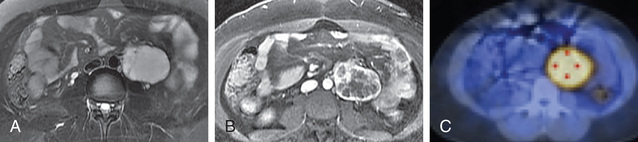

Most tumors in the area of the adrenal gland are readily localized by CT or MRI (Fig. 599.1 ), but extraadrenal tumors may be difficult to detect. 123 I-metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) is taken up by chromaffin tissue anywhere in the body and is useful for localizing small tumors. PET-CT or PET-MRI with MIBG, DOPA, succinate, or FDG is highly sensitive and a more favored imaging approach (Fig. 599.2 ) for difficult to localize tumors. Venous catheterization with sampling of blood at different levels for catecholamine determinations is now only rarely necessary for localizing the tumor.

Differential Diagnosis

Various causes of hypertension in children must be considered, such as renal or renovascular disease; coarctation of the aorta; hyperthyroidism; Cushing syndrome; deficiencies of 11β-hydroxylase, 17α-hydroxylase, or 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (type 2 isozyme); primary aldosteronism; adrenocortical tumors; and, rarely, essential hypertension (see Chapter 472 ). A nonfunctioning kidney may result from compression of a ureter or of a renal artery by a pheochromocytoma. Paroxysmal hypertension may be associated with porphyria or familial dysautonomia. Cerebral disorders, diabetes insipidus, diabetes mellitus, and hyperthyroidism must also be considered in the differential diagnosis. Hypertension in patients with neurofibromatosis may be caused by renal vascular involvement or by concurrent pheochromocytoma.

Neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma, and ganglioneuroma frequently produce catecholamines, but urinary levels of most catecholamines are higher in patients with pheochromocytoma, although levels of dopamine and homovanillic acid are usually higher in neuroblastoma. Secreting neurogenic tumors often produce hypertension, excessive sweating, flushing, pallor, rash, polyuria, and polydipsia. Chronic diarrhea may be associated with these tumors, particularly with ganglioneuroma, and at times may be sufficiently persistent to suggest celiac disease.

Treatment

These tumors must be removed surgically, but careful preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative management is essential. Manipulation and excision of these tumors result in marked increases in catecholamine secretion that increase blood pressure and heart rate. Therefore, preoperative α- and β-adrenergic blockade are required. Because these tumors are often multiple in children, a thorough transabdominal exploration of all the usual sites offers the best opportunity to find them all. Appropriate choice of anesthesia and expansion of blood volume with appropriate fluids before and during surgery are critical to avoid a precipitous drop in blood pressure during operation or within 48 hr postoperatively. Surveillance must continue postoperatively.

Although these tumors often appear malignant histologically, the only accurate indicators of malignancy are the presence of metastatic disease or local invasiveness that precludes complete resection, or both. Approximately 10% of all adrenal pheochromocytomas are malignant. Such tumors are rare in childhood; pediatric malignant pheochromocytomas occur more frequently in extraadrenal sites and are often associated with mutations in the SDHB gene encoding a subunit of succinate dehydrogenase. Prolonged follow-up is indicated because functioning tumors at other sites may be manifested many years after the initial operation. Examination of relatives of affected patients may reveal other individuals harboring unsuspected tumors that may be asymptomatic.