Hearing Loss

Joseph Haddad Jr, Sonam N. Dodhia, Jaclyn B. Spitzer

Incidence and Prevalence

Bilateral neural hearing loss is categorized as mild (20-30 dB hearing level, HL), moderate (30-50 dB HL), moderately severe (50-70 dB HL), severe (75-85 dB HL), or profound (>85 dB). The World Health Organization estimates that approximately 360 million people (5% of the world's population, including 32 million children) have disabling hearing loss. An additional 364 million people have mild hearing loss. Half of these cases could have been prevented. In the United States, the average incidence of neonatal hearing loss is 1.6 per 1,000 infants; the rate by state varies from 0.22 to 3.61 per 1,000. Among children and adolescents, the prevalence of mild or greater hearing loss is 3.1% and is higher among Latin Americans, African Americans, and persons from lower-income families.

Onset of hearing loss in children can occur at any time in childhood. When less-severe hearing loss or the transient hearing loss that commonly accompanies middle-ear disease in young children is considered, the number of affected children increases substantially.

Types of Hearing Loss

Hearing loss can be peripheral or central in origin. Peripheral hearing loss can be conductive, sensorineural, or mixed. Conductive hearing loss (CHL) commonly is caused by dysfunction in the transmission of sound through the external or middle ear. CHL is the most common type of hearing loss in children and occurs when sound transmission is physically impeded in the external and/or middle ear. Common causes of CHL in the ear canal include aural atresia or stenosis, impacted cerumen, or foreign bodies. In the middle ear , perforation of the tympanic membrane (TM), discontinuity or fixation of the ossicular chain, otitis media (OM) with effusion, otosclerosis, and cholesteatoma can cause CHL.

Damage to or maldevelopment of structures in the inner ear can cause sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) . Causes include hair cell destruction from noise, disease, or ototoxic agents; cochlear malformation; perilymphatic fistula of the round or oval window membrane; and failure in development or lesions of the acoustic division of the 8th nerve. Coexistent CHL and SNHL is considered a mixed hearing loss .

An auditory deficit originating along the central auditory nervous system pathways from the proximal 8th nerve to the cerebral cortex usually is considered central (or retrocochlear ) hearing loss. Tumors or demyelinating disease of the 8th nerve and cerebellopontine angle can cause hearing deficits but spare the outer, middle, and inner ear. These causes of hearing loss are rare in children. Functional disorders of the eighth nerve and/or brainstem pathways may manifest in a variety of clinical defects known collectively as auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD) or auditory dyssynchrony, without abnormalities demonstrable on imaging. Other forms of central auditory deficits, known as central auditory processing disorders , include those that make it difficult even for children with normal hearing sensitivity to listen selectively in the presence of noise, to combine information from the 2 ears properly, to process speech when it is slightly degraded, and to integrate auditory information when it is delivered faster although they can process it when delivered at a slow rate. These deficits can manifest as specific language disorders or poor attention, or as academic or behavior problems in school. Strategies for coping with such disorders are available for older children, and identification and documentation of the central auditory processing disorder allow parents and teachers to make appropriate accommodations to enhance learning.

Etiology

Most CHL is acquired, with middle-ear fluid the most common cause. Congenital causes include anomalies of the pinna, external ear canal, TM, and ossicles. Rarely congenital cholesteatoma or other masses in the middle ear manifest as CHL. TM perforation (e.g., trauma, OM), ossicular discontinuity (e.g., infection, cholesteatoma, trauma), tympanosclerosis, acquired cholesteatoma, or masses in the ear canal or middle ear (Langerhans cell histiocytosis, salivary gland tumors, glomus tumors, rhabdomyosarcoma) also can manifest as CHL. Uncommon diseases that affect the middle ear and temporal bone and can manifest with CHL include otosclerosis, osteopetrosis, fibrous dysplasia, and osteogenesis imperfecta.

SNHL may be congenital or acquired. Acquired SNHL may be caused by genetic, infectious, autoimmune, anatomic, traumatic, ototoxic, and idiopathic factors (Tables 655.1 to 655.4 ). The recognized risk factors account for approximately 50% of cases of moderate to profound SNHL.

Table 655.3

Common Types of Early-Onset Hereditary Nonsyndromic Sensorineural Hearing Loss

| LOCUS | GENE | AUDIO PHENOTYPE |

|---|---|---|

| DFN3 | POU3F4 | Conductive hearing loss as a result of stapes fixation mimicking otosclerosis; superimposed progressive SNHL |

| DFNA1 | DIAPH1 | Low-frequency loss beginning in the 1st decade and progressing to all frequencies to produce a flat audio profile with profound losses throughout the auditory range |

| DFNA2 | KCNQ4 | Symmetric high-frequency sensorineural loss beginning in the 1st decade and progressing over all frequencies |

| GJB3 | Symmetric high-frequency sensorineural loss beginning in the 3rd decade | |

| DFNA3 | GJB2 | Childhood-onset, progressive, moderate-to-severe high-frequency sensorineural hearing impairment |

| GJB6 | Childhood-onset, progressive, moderate-to-severe high-frequency sensorineural hearing impairment | |

| DFNA6, 14, and 38 | WFS1 | Early-onset low-frequency sensorineural loss; approximately 75% of families dominantly segregating this audio profile carry missense mutations in the C-terminal domain of wolframin |

| DFNA8, and 12 | TECTA | Early-onset stable bilateral hearing loss, affecting mainly mid to high frequencies |

| DFNA10 | EYA4 | Progressive loss beginning in the 2nd decade as a flat to gently sloping audio profile that becomes steeply sloping with age |

| DFNA11 | MYO7A | Ascending audiogram affecting low and middle frequencies at young ages and then affecting all frequencies with increasing age |

| DFNA13 | COL11A2 | Congenital midfrequency sensorineural loss that shows age-related progression across the auditory range |

| DFNA15 | POU4F3 | Bilateral progressive sensorineural loss beginning in the 2nd decade |

| DFNA20, and 26 | ACTG1 | Bilateral progressive sensorineural loss beginning in the 2nd decade; with age, the loss increases with threshold shifts in all frequencies, although a sloping configuration is maintained in most cases |

| DFNA22 | MYO6 | Postlingual, slowly progressive, moderate to severe hearing loss |

| DFNB1 | GJB2, GJB6 | Hearing loss varies from mild to profound. The most common genotype, 35delG/35delG, is associated with severe to profound SNHL in about 90% of affected children; severe to profound deafness is observed in only 60% of children who are compound heterozygotes carrying 1 35delG allele and any other GJB2 SNHL-causing allele variant; in children carrying 2 GJB2 SNHL-causing missense mutations, severe to profound deafness is not observed |

| DFNB3 | MYO7A | Severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss |

| DFNB4 | SLC26A4 | DFNB4 and Pendred syndrome (see Table 655.5 ) are allelic. DFNB4 hearing loss is associated with dilation of the vestibular aqueduct and can be unilateral or bilateral. In the high frequencies, the loss is severe to profound; in the low frequencies, the degree of loss varies widely. Onset can be congenital (prelingual), but progressive postlingual loss also is common |

| DFNB7, and 11 | TMC1 | Severe-to-profound prelingual hearing impairment |

| DFNB9 | OTOF | OTOF -related deafness is characterized by two phenotypes: prelingual nonsyndromic hearing loss and, less frequently, temperature-sensitive nonsyndromic auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder. The nonsyndromic hearing loss is bilateral severe-to-profound congenital deafness |

| DFNB12 | CDH23 | Depending on the type of mutation, recessive mutations of CDH23 can cause nonsyndromic deafness or type 1 Usher syndrome (USH1), which is characterized by deafness, vestibular areflexia, and vision loss as a result of retinitis pigmentosa |

| DFNB16 | STRC | Early-onset nonsyndromic autosomal recessive sensorineural hearing loss |

| mtDNA 1555A > G | 12S rRNA | Degree of hearing loss varies from mild to profound but usually is symmetric; high frequencies are preferentially affected; precipitous loss in hearing can occur after aminoglycoside therapy |

SNHL , Sensorineural hearing loss.

Adapted from Smith RJH, Bale JF Jr, White KR: Sensorineural hearing loss in children. Lancet 365:879–890, 2005.

Table 655.4

Common Types of Syndromic Sensorineural Hearing Loss

| SYNDROME | GENE | PHENOTYPE |

|---|---|---|

| DOMINANT | ||

| Waardenburg (WS1) | PAX3 | Major diagnostic criteria include dystopia canthorum, congenital hearing loss, heterochromic irises, white forelock, and an affected 1st-degree relative. Approximately 60% of affected children have congenital hearing loss; in 90%, the loss is bilateral. |

| Waardenburg (WS2) | MITF , others | Major diagnostic criteria are as for WS1 but without dystopia canthorum. Approximately 80% of affected children have congenital hearing loss; in 90%, the loss is bilateral. |

| Branchiootorenal | EYA1 | Diagnostic criteria include hearing loss (98%), preauricular pits (85%), and branchial (70%), renal (40%), and external-ear (30%) abnormalities. The hearing loss can be conductive, sensorineural, or mixed, and mild to profound in degree. |

| CHARGE syndrome | CHD7 | Choanal atresia, colobomas, heart defect, retardation, genital hypoplasia, ear anomalies, deafness. Can lead to sensorineural or mixed hearing loss. Can be autosomal dominant or isolated cases. |

| Goldenhar syndrome | Unknown | Part of the hemifacial microsomia spectrum. Facial hypoplasia, ear anomalies, hemivertebrae, parotid gland dysfunction. Can cause conductive or mixed hearing loss. Can be autosomal dominant or sporadic. |

| RECESSIVE | ||

| Pendred syndrome | SLC26A4 | Diagnostic criteria include sensorineural hearing loss that is congenital, nonprogressive, and severe to profound in many cases, but can be late-onset and progressive; bilateral dilation of the vestibular aqueduct with or without cochlear hypoplasia; and an abnormal perchlorate discharge test or goiter. |

| Alport syndrome | COL4A3, COL4A4, and COL4A5 | Nephritis, deafness, lens defects, retinitis. Can lead to bilateral sensorineural hearing loss in the 2,000-8,000 Hz range. The hearing loss develops gradually and is not generally present in early infancy. |

| Usher syndrome type 1 (USH1) | USH1A, MYO7A, USH1C, CDH23, USH1E, PCDH15, USH1G | Diagnostic criteria include congenital, bilateral, and profound hearing loss, vestibular areflexia, and retinitis pigmentosa (commonly not diagnosed until tunnel vision and nyctalopia become severe enough to be noticeable). |

| Usher syndrome type 2 (USH2) | USH2A, USH2B, USH2C, others | Diagnostic criteria include mild to severe, congenital, bilateral hearing loss and retinitis pigmentosa; hearing loss may be perceived as progressing over time because speech perception decreases as diminishing vision interferes with subconscious lip reading. |

| Usher syndrome type 3 (USH3) | USH3 | Diagnostic criteria include postlingual, progressive sensorineural hearing loss, late-onset retinitis pigmentosa, and variable impairment of vestibular function. |

Adapted from Smith RJH, Bale JF Jr, White KR: Sensorineural hearing loss in children. Lancet 365:879–890, 2005.

Sudden SNHL in a previously healthy child is uncommon but may be from OM or other cochlear pathologies such as autoimmunity. Usually these causes are obvious from the history and physical examination. Sudden loss of hearing in the absence of obvious causes often is the result of a vascular event affecting the cochlear apparatus or nerve, such as embolism or thrombosis (secondary to prothrombotic conditions), or an autoimmune process. Additional causes include perilymph fistula, drugs, trauma, and the first episode of Meniere syndrome. In adults, sudden SNHL is often idiopathic and unilateral; it may be associated with tinnitus and vertigo. Identifiable causes of sudden SNHL include infections (Epstein-Barr virus, varicella-zoster virus, herpes simplex virus), vascular injury to the cochlea, enlarged vestibular aqueduct, endolymphatic hydrops, and autoimmune inflammatory diseases. In most patients with sudden SNHL, no etiology is discovered, and it is termed idiopathic sudden SNHL .

Infectious Causes

The most common infectious cause of congenital SNHL is cytomegalovirus (CMV) , which infects 1 in 100 newborns in the United States (see Chapters 131 and 282 ). Of these, 6,000-8,000 infants each year have clinical manifestations, including approximately 75% with SNHL. Congenital CMV warrants special attention because it is associated with hearing loss in its symptomatic and asymptomatic forms with bilateral and unilateral hearing loss, respectively; the hearing loss may be progressive. Some children with congenital CMV have suddenly lost residual hearing at 4-5 yr of age. Much less common congenital infectious causes of SNHL include toxoplasmosis and syphilis. Congenital CMV, toxoplasmosis, and syphilis also can manifest with delayed onset of SNHL months to years after birth. Rubella, once the most common viral cause of congenital SNHL, is very uncommon because of effective vaccination programs. In utero infection with herpes simplex virus is rare, and hearing loss is not an isolated manifestation.

Other postnatal infectious causes of SNHL include neonatal group B streptococcal sepsis and bacterial meningitis at any age. Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common cause of bacterial meningitis that results in SNHL after the neonatal period and has become less common with the routine administration of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Haemophilus influenzae type b, once the most common cause of meningitis resulting in SNHL, is rare owing to the H. influenzae type b conjugate vaccine. Uncommon infectious causes of SNHL include Lyme disease, parvovirus B19, and varicella. Mumps, rubella, and measles, all once common causes of SNHL in children, are rare owing to vaccination programs. When these infectious etiologies occur, the resulting hearing loss is frequently bilateral and severe.

Genetic Causes

Genetic causes of SNHL probably are responsible for as many as 50% of SNHL cases (see Tables 655.3 and 655.4 ). These disorders may be associated with other abnormalities, may be part of a named syndrome, or can exist in isolation. SNHL often occurs with abnormalities of the ear and eye and with disorders of the metabolic, musculoskeletal, integumentary, renal, and nervous systems.

Autosomal dominant hearing losses account for approximately 10% of all cases of childhood SNHL. Waardenburg (types I and II) and branchiootorenal syndromes represent two of the most common autosomal dominant syndromic types of SNHL. Types of SNHL are coded with a 4-letter code and a number, as follows: DFN = deafness, A = dominant, B = recessive, and number = order of discovery (e.g., DFNA 13). Autosomal dominant conditions in addition to those just discussed include DFNA 1-18, 20-25, 30, 36, 38, and mutations in the crystallin gene (CRYM).

Autosomal recessive genetic SNHL, both syndromic and nonsyndromic, accounts for approximately 80% of all childhood cases of SNHL. Usher syndrome (types 1, 2, and 3: all associated with blindness, retinitis pigmentosa), Pendred syndrome, and the Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome (one form of the long Q-T syndrome) are three of the most common syndromic recessive types of SNHL. Other autosomal recessive conditions include Alström syndrome, type 4 Bartter syndrome, biotinidase deficiency, and DFNB 1-18, 20-23, 26-27, 29-33, 35-40, 42, 44, 46, 48, 49, 53, and 55.

Unlike children with an easily identified syndrome or with anomalies of the outer ear, who may be identified as being at risk for hearing loss and consequently monitored, children with nonsyndromic hearing loss present greater diagnostic difficulty. Mutations of the connexin-26 and -30 genes are identified in autosomal recessive (DNFB 1) and autosomal dominant (DNFA 3) SNHL and in sporadic patients with nonsyndromic SNHL; up to 50% of nonsyndromic SNHLs may be related to a mutation of connexin-26. Mutations of the GJB2 gene colocalize with DFNA 3 and DFNB 1 loci on chromosome 13, are associated with autosomal nonsyndromic susceptibility to deafness, and are associated with as many as 30% of cases of sporadic severe to profound congenital deafness and 50% of cases of autosomal recessive nonsyndromic deafness. In addition, mutations in GJB6 are associated with approximately 5% of recessive nonsyndromic deafness. Sex-linked disorders associated with SNHL, thought to account for 1–2% of SNHLs, include Norrie disease, the otopalatal digital syndrome, Nance deafness, and Alport syndrome. Chromosomal abnormalities such as trisomy 13-15, trisomy 18, and trisomy 21 also can be accompanied by hearing impairment. Patients with Turner syndrome have monosomy for all or part of one X chromosome and can have CHL, SNHL, or mixed hearing loss. The hearing loss may be progressive. Mitochondrial genetic abnormalities also can result in SNHL (see Table 655.3 ).

Many genetically determined causes of hearing impairment, both syndromic and nonsyndromic, do not express themselves until sometime after birth. Alport, Alström, Down, and Hunter-Hurler syndromes and von Recklinghausen disease are genetic diseases that can have SNHL as a late manifestation.

Physical Causes

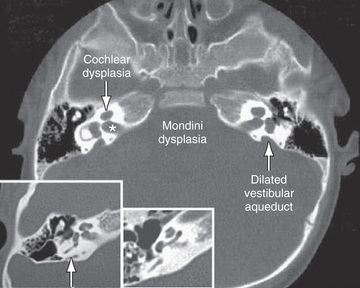

Agenesis or malformation of cochlear structures may be genetic; these include the Scheibe, Mondini (Fig. 655.1 ), Alexander, and Michel anomalies, enlarged vestibular aqueducts (in isolation or associated with Pendred syndrome), and semicircular canal anomalies. These anomalies most likely develop before the 8th wk of gestation and result from arrest in normal development, aberrant development, or both. Many of these anomalies also have been described in association with other congenital conditions such as intrauterine CMV and rubella infections. These abnormalities are quite common; in as many as 20% of children with SNHL, obvious or subtle temporal bone abnormalities are seen on high-resolution CT scanning or MRI.

Conditions, diseases, or syndromes that include craniofacial abnormalities may be associated with CHL and possibly with SNHL. Pierre Robin Sequence and Treacher Collins, Klippel-Feil, Crouzon, and branchiootorenal syndromes and osteogenesis imperfecta often are associated with hearing loss. Congenital anomalies causing CHL include malformations of the ossicles and middle-ear structures and atresia of the external auditory canal.

SNHL also can occur secondary to exposure to toxins, chemicals, antimicrobials, and noise exposure. Early in pregnancy, the embryo is particularly vulnerable to the effects of toxic substances. Ototoxic drugs, including aminoglycosides, loop diuretics, and chemotherapeutic agents (cisplatin) also can cause SNHL. Congenital SNHL can occur secondary to exposure to these drugs as well as to thalidomide and retinoids. Certain chemicals, such as quinine, lead, and arsenic, can cause hearing loss both prenatally and postnatally. Among adolescents, the use of personal listening devices at high volume settings has been found to be correlated to hearing loss.

Trauma, including temporal bone fractures, inner ear concussion, head trauma, iatrogenic trauma (e.g., surgery, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation), radiation exposure, and noise, also can cause SNHL. Other uncommon causes of SNHL in children include autoimmune disease (systemic or limited to the inner ear), metabolic abnormalities, and neoplasms of the temporal bone.

Effects of Hearing Impairment

The effects of hearing impairment depend on the nature and degree of the hearing loss and on the individual characteristics of the child. Hearing loss may be unilateral or bilateral, conductive, sensorineural, or mixed; mild, moderate, severe, or profound; of sudden or gradual onset; stable, progressive, or fluctuating; and affecting a part or all of the audible spectrum. Other factors, such as intelligence, medical or physical condition (including accompanying syndromes), family support, age at onset, age at time of identification, and promptness of intervention, also affect the impact of hearing loss on a child.

Most hearing-impaired children have some usable hearing. Only 6% of those in the hearing-impaired population have bilateral profound hearing loss. Hearing loss very early in life can affect the development of speech and language, social and emotional development, behavior, attention, and academic achievement. Some cases of hearing impairment are misdiagnosed because affected children have sufficient hearing to respond to environmental sounds and can learn some speech and language but when challenged in the classroom cannot perform to full potential.

Even mild or unilateral hearing loss can have a detrimental effect on the development of a young child and on school performance. Children with such hearing impairments have greater difficulty when listening conditions are unfavorable (e.g., background noise and poor acoustics), as can occur in a classroom. The fact that schools are auditory-verbal environments is unappreciated by those who minimize the impact of hearing impairment on learning. Hearing loss should be considered in any child with speech and language difficulties or below-par performance, poor behavior, or inattention in school (Table 655.5 ).

Table 655.5

Hearing Handicap as a Function of Average Hearing Threshold Level of the Better Ear

| AVERAGE THRESHOLD LEVEL (dB) AT 500-2,000 Hz (ANSI) | DESCRIPTION | COMMON CAUSES | WHAT CAN BE HEARD WITHOUT AMPLIFICATION | DEGREE OF HANDICAP (IF NOT TREATED IN 1ST YR OF LIFE) | PROBABLE NEEDS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-15 | Normal range | Conductive hearing loss | All speech sounds | None | None |

| 16-25 | Slight hearing loss | Otitis media, TM perforation, tympanosclerosis; eustachian tube dysfunction; some SNHL | Vowel sounds heard clearly, may miss unvoiced consonant sounds |

Mild auditory dysfunction in language learning Difficulty in perceiving some speech sounds |

Consideration of need for hearing aid, speech reading, auditory training, speech therapy, appropriate surgery, preferential seating |

| 26-30 | Mild | Otitis media, TM perforation, tympanosclerosis, severe eustachian dysfunction, SNHL | Hears only some speech sounds, the louder voiced sounds |

Auditory learning dysfunction Mild language retardation Mild speech problems Inattention |

Hearing aid Lip reading Auditory training Speech therapy Appropriate surgery |

| 31-50 | Moderate hearing loss | Chronic otitis, ear canal/middle ear anomaly, SNHL | Misses most speech sounds at normal conversational level |

Speech problems Language retardation Learning dysfunction Inattention |

All of the above, plus consideration of special classroom situation |

| 51-70 | Severe hearing loss | SNHL or mixed loss due to a combination of middle-ear disease and sensorineural involvement | Hears no speech sound of normal conversations |

Severe speech problems Language retardation Learning dysfunction Inattention |

All of the above; probable assignment to special classes |

| 71+ | Profound hearing loss | SNHL or mixed | Hears no speech or other sounds |

Severe speech problems Language retardation Learning dysfunction Inattention |

All of the above; probable assignment to special classes or schools |

ANSI , American National Standards Institute; SNHL , sensorineural hearing loss; TM , tympanic membrane.

Modified from Northern JL, Downs MP: Hearing in children, ed 4, Baltimore, 1991, Williams & Wilkins.

Children with moderate, severe, or profound hearing impairment, and those with other handicapping conditions, often are educated in classes or schools for children with special needs. There is a strong trend toward integrating a child with hearing loss into the least restrictive learning environment; this approach can only be successful if there are sufficient supportive services available to support auditory and other learning needs. The auditory management and choices regarding modes of communication and education for children with hearing handicaps must be individualized, because these children are not a homogeneous group. A team approach to individual case management is essential, because each child and family unit has unique needs and abilities.

Hearing Screening

Hearing impairment can have a major impact on a child's development, and because early identification improves prognosis, screening programs have been widely and strongly advocated. The National Center for Hearing Assessment and Management estimates that the detection and treatment at birth of hearing loss saves $400,000 per child in special education costs; screening costs approximately $8-$50/child. Data from the Colorado newborn screening program suggest that if hearing-impaired infants are identified and treated by age 6 mo, these children (with the exception of those with bilateral profound impairment) should develop the same level of language as their age-matched peers who are not hearing impaired. These data provide compelling support for establishing mandated newborn hearing screening programs for all children. The American Academy of Pediatrics endorses the goal of universal detection of hearing loss in infants before 3 mo of age, with appropriate intervention no later than 6 mo of age. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that of the approximately 4 million infants born in the United States in 2014, 97.9% were screened for hearing loss.

Until mandated screening programs are established universally, many hospitals will continue to use other criteria to screen for hearing loss. Some use the high-risk criteria (see Table 655.1 ) to decide which infants to screen; some screen all infants who require intensive care; and some do both. The problem with using high-risk criteria to screen is that 50% of cases of hearing impairment will be missed, either because the infants are hearing impaired but do not meet any of the high-risk criteria or because they develop hearing loss after the neonatal period.

The recommended hearing screening techniques are either otoacoustic emissions (OAE) testing or auditory brainstem evoked responses (ABRs). The ABR test, an auditory evoked electrophysiologic response that correlates highly with hearing, has been used successfully and cost-effectively to screen newborns and to identify further the degree and type of hearing loss. OAE tests, used successfully in most universal newborn screening programs, are quick, easy to administer, and inexpensive, and they provide a sensitive indication of the presence of hearing loss. Results are relatively easy to interpret. OAE tests elicit no response if hearing is worse than 30-40 dB, no matter what the cause; children who fail OAE tests undergo an ABR for a more definitive evaluation as meta-analyses have demonstrated that ABR has a higher sensitivity and specificity. It is recommended that both OAE measurement and ABR screening be used in the intensive care unit setting. Screening methods such as observing behavioral responses to uncalibrated noisemakers or using automated systems such as the Crib-o-gram (Canon) or the auditory response cradle (in which movement of the infant in response to sound is recorded by motion sensors) are not recommended.

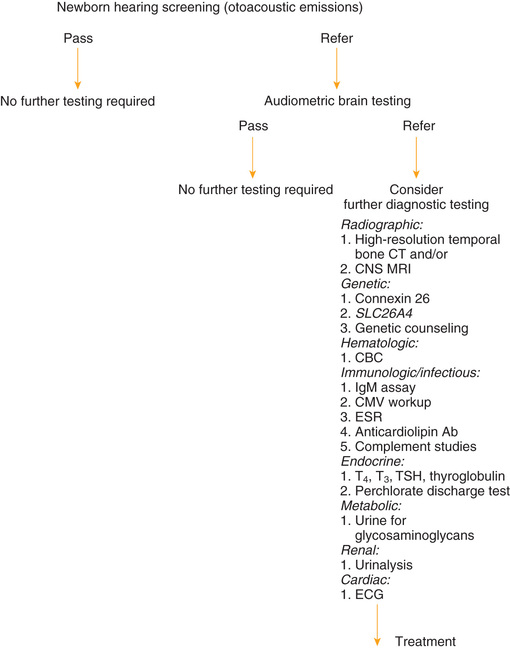

Many children become hearing impaired after the neonatal period and therefore are not identified by newborn screening programs. Often it is not until children are in preschool or kindergarten that further hearing screening takes place; an evidence-based systematic review has identified pure-tone and OAE screening to be effective, with pure-tone screening having higher sensitivity. Among adolescents, high frequency hearing loss is associated with exposure to loud noises, so attention should be paid to those frequencies on a hearing screen; most noise-induced hearing loss is around 4 kHz. Fig. 655.2 provides recommendations for postneonatal screening.

Identification of Hearing Impairment

The impact of hearing impairment is greatest on an infant who has yet to develop language; consequently, identification, diagnosis, description, and treatment should begin as soon as possible. Infants with a prenatal or perinatal history that puts them at risk (see Table 655.3 ) or those who have failed a formal hearing screening should be evaluated by an experienced clinical audiologist until a reliable assessment of auditory sensitivity has been obtained. Pediatricians should encourage families to cooperate with the follow-up plan. Infants who are born at risk but who were not screened as neonates (e.g., because of transfer from one hospital to another) should have a hearing screening by age 3 mo.

Hearing-impaired infants, who are born at risk or are screened for hearing loss in a neonatal hearing screening program, account for only a portion of hearing-impaired children. Children who are congenitally deaf because of autosomal recessive inheritance or subclinical congenital infection often are not identified until 1-3 yr of age. Usually those with more-severe hearing loss are identified at an earlier age, but identification often occurs later than the age at which intervention can provide an optimal outcome, especially in countries lacking technologic resources. Children who hear normally develop extensive receptive and expressive language by 3-4 yr of age (Table 655.6 ) and exhibit behavior reflecting normal auditory function (Table 655.7 ). Failure to fulfill these criteria should be the reason for an audiologic evaluation. Parents’ concern about hearing and any delayed development of speech and language should alert the pediatrician, because parents’ concern usually precedes formal identification and diagnosis of hearing impairment by 6 mo to 1 yr of age.

Table 655.6

From Matkin ND: Early recognition and referral of hearing-impaired children. Pediatr Rev 6:151–156, 1984. Reproduced by permission of Pediatrics.

Table 655.7

From Matkin ND: Early recognition and referral of hearing-impaired children. Pediatr Rev 6:151–156, 1984.

Clinical Audiologic Evaluation

When hearing impairment is suspected in a young child, reliable and valid estimates of auditory function can be obtained using electrophysiologic and age-appropriate behavioral measurement. Successful treatment strategies for hearing-impaired children rely on prompt identification and ongoing assessment to define the dimensions of auditory function. Cooperation among the pediatrician and specialists in areas such as audiology, speech and language pathology, education, and child development is necessary to optimize auditory-verbal development. Therapy for hearing-impaired children may include an amplification device, a frequency modulation (FM) system in the classroom, close monitoring of hearing and auditory skills, speech and language therapy, counseling of parents and families, advising teachers, and dealing with public agencies.

Audiometry

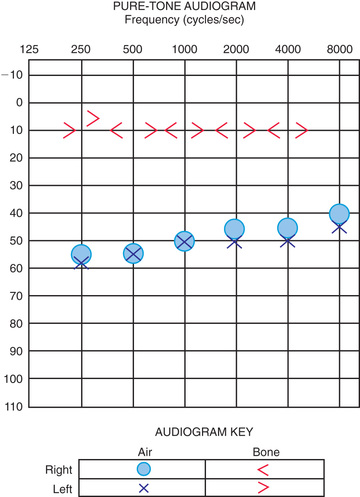

Audiologic evaluation technique varies as a function of the age and developmental level of the child, the reason for the evaluation, and the child's otologic condition or history. An audiogram provides the fundamental description of hearing sensitivity (Fig. 655.3 ). Hearing thresholds are assessed as a function of frequency using pure tones (single frequency stimuli) at octave intervals from 250 to 8,000 Hz. When the child is old enough to accept their placement, earphones typically are used to assess each ear independently. Prior to this stage, testing may be performed in a sound treated environment with stimuli delivered via speakers; this approach permits description only of the better hearing ear.

Air-conducted signals are presented through earphones (or loudspeakers) and are used to provide information about the sensitivity of the entire auditory system. These same test sounds can be delivered to the ear through an oscillator that is placed on the head, usually on the mastoid. Such signals are considered bone-conducted because the bones of the skull transmit vibrations as sound energy directly to the inner ear, essentially bypassing the outer and middle ears. In a normal ear, and also in children with SNHL, the air- and bone-conduction thresholds are equivalent. In those with CHL, bone-conduction thresholds are more sensitive than air- conducted responses; this is called the air–bone gap , which indicates the amount of hearing loss attributable to dysfunction in the outer and/or middle ear. In mixed hearing loss, both the bone- and air-conduction thresholds are abnormal, and there is additionally an air–bone gap.

Speech-Recognition Threshold

Another measure useful for describing auditory function is the speech-recognition threshold (SRT) , which is the lowest intensity level at which a score of approximately 50% correct is obtained on a task of recognizing spondee words. Spondee words are 2-syllable words or phrases that have equal stress on each syllable, such as baseball , hotdog , and pancake . Listeners must be familiar with all the words for a valid test result to be obtained. The SRT should correspond to the average of pure-tone thresholds at 500, 1,000, and 2,000 Hz, the pure-tone average. The SRT is relevant as an indicator of a child's potential for development and use of speech and language; it also serves as a check of the validity of a test because children with nonorganic hearing loss (malingerers) might show a discrepancy between the pure-tone average and SRT. An SRT may be obtained in a child with expressive speech or language limitations using modified techniques, such a picture-pointing responses.

The basic battery of hearing tests concludes with an assessment of a child's ability to understand monosyllabic words when presented at a comfortable listening level. Performance on such word recognition tests assists in the differential diagnosis of hearing impairment and provides a measure of how well a child performs when speech is presented at loudness levels similar to those encountered in conversation. For speech recognition as well, a picture pointing response may be obtained with standardized tests.

Play Audiometry

Hearing testing technique is age dependent. For children at or above the developmental level of a 5-6 yr old, conventional test methods can be used. For children 30 mo to 5 yr of age, play audiometry can be used. Responses in play audiometry usually are conditioned motor activities associated with a game, such as dropping blocks in a bucket, placing rings on a peg, or completing a puzzle. The technique can be used to obtain a reliable audiogram for a preschool child.

Visual Reinforcement Audiometry

For children between the ages of about 6 and 30 mo, visual reinforcement audiometry (VRA) is commonly used. In this technique, the child is conditioned to turn his/her head in response to a tonal signal from a speaker in the same location as an animated (mechanical) toy or video reinforcer. If infants are properly conditioned, by presenting sounds associated with the reinforcer, VRA can provide reliable estimates of hearing sensitivity for tonal signals and speech sounds. In most applications of VRA, sounds are presented by loudspeakers in a sound field, so ear-specific information is not obtained. Assessment of an infant often is designed to rule out hearing loss that would be sufficient to affect the development of speech and language. Normal sound-field response levels of infants indicate sufficient hearing for this purpose despite the possibility of different HLs in the 2 ears. When ear-specific information is needed in this age group, the ABR is conducted under sleep deprived or sedated conditions.

Behavioral Observation Audiometry

Used as a screening device for infants <5 mo of age, behavioral observation audiometry is limited to unconditioned, reflexive responses to complex (not frequency-specific) test sounds such as warble tones, narrow band noise, speech, or music presented using calibrated signals from a loudspeaker. Response levels can vary widely within and among infants and usually do not provide a reliable estimate of sensitivity. The types of responses observed during this testing may include alterations in sucking behavior, initiation or cessation in crying, pupillary dilatation, and alterations in respiration.

Assessment of a child with suspected hearing loss is not complete until pure-tone hearing thresholds and SRTs (a reliable audiogram) have been obtained in each ear. Behavioral observation audiometry and VRA in sound-field testing give estimates of hearing responsivity in the better-hearing ear . When significant hearing loss is suspected in infants, electrophysiologic assessments must be conducted to permit early intervention.

Acoustic Immittance Testing

Acoustic immittance testing is a standard part of the clinical audiologic test battery and includes tympanometry, acoustic reflex threshold measurement, and acoustic reflex decay testing. It is a useful objective assessment technique that provides information about the status of the TM, middle ear and acoustic reflex arc. Tympanometry can be performed in a physician's office and is helpful in the diagnosis and management of OM with effusion, a common cause of mild to moderate hearing loss in young children.

Tympanometry

Tympanometry provides a graph (tympanogram) of the middle ear's ability to transmit sound energy (admittance or compliance) or impede sound energy (impedance) as a function of air pressure in the external ear canal. Because most immittance test instruments measure acoustic admittance, the term admittance is used here. The principles apply to whatever units of measurement are used.

A probe is inserted into the entrance of the external ear canal so that an airtight seal is obtained. A manometer in the probe varies air pressure, while a sound generator presents a tone, and a microphone measures the sound pressure level reflected back. The sound pressure measured in the ear canal relative to the known intensity of the probe signal is used to estimate the acoustic admittance of the ear canal and middle-ear system. Admittance can be expressed in a unit called a millimho (mmho) or as a volume of air (mL) with equivalent acoustic admittance. Additionally, an estimate can be made of the volume of air enclosed between the probe tip and TM. The acoustic admittance of this volume of air is deducted from the overall admittance measure to obtain a measure of the admittance of the middle-ear system alone. Estimating ear canal volume also has a diagnostic benefit, because an abnormally large value is consistent with the presence of an opening in the TM (perforation, pressure equalization tube, or surgical defect).

Once the admittance of the air mass in the external auditory canal has been eliminated, it is assumed that the remaining admittance measure accurately reflects the admittance of the entire middle-ear system. Its value is controlled largely by the dynamics of the TM. Abnormalities of the TM can dictate the shape of tympanograms, thus obscuring abnormalities medial to the TM. In addition, the frequency of the probe tone, the speed and direction of the air pressure change, and the air pressure at which the tympanogram is initiated can all influence the outcome. The effect of the probe tone frequency is well documented, and in young children (<4-6 mo) with small ear canals, use of a high frequency probe tone, either 678 or 1,000 Hz, is recommended.

When air pressure in the ear canal is equal to that in the middle ear, the middle-ear system is functioning optimally. That is, the pressure equalization function of the eustachian tube permits the middle ear to rest at atmospheric pressure, equivalent to the condition in the ear canal. Therefore the ear canal pressure at which there is the greatest flow of energy (admittance) should be a reasonable estimate of the air pressure in the middle-ear space. This pressure is determined by finding the maximum or peak admittance on the tympanogram and obtaining its value on the x -axis. The value on the y -axis at the tympanogram peak is an estimate of peak admittance based on admittance tympanometry (Table 655.8 ). This peak measure sometimes is referred to as static acoustic admittance , even though it is estimated from a dynamic measure. Normative values for peak admittance as a function of air pressure are well established.

Table 655.8

Norms for Peak (Static) Admittance Using a 226-Hz Probe Tone for Children and Adults

| AGE GROUP | ADMITTANCE (mL) | SPEED OF AIR PRESSURE SWEEP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤50 daPa/sec* | 200 daPa/sec † | ||

| Children (3-5 yr) | Lower limit | 0.30 | 0.36 |

| Median | 0.55 | 0.61 | |

| Upper limit | 0.90 | 1.06 | |

| Adults | Lower limit | 0.56 | 0.27 |

| Median | 0.85 | 0.72 | |

| Upper limit | 1.36 | 1.38 | |

* Ear canal volume measurement based on admittance at lowest tail of tympanogram.

† Ear canal measurement based on admittance at lowest tail of tympanogram for children and at +200 daPa for adults.

daPa , decaPascals.

Adapted from Margolis RH, Shanks JE: Tympanometry: basic principles of clinical application. In Rintelman WS, editor: Hearing assessment , ed 2, Austin, 1991, PRODED, pp. 179–245.

Tympanometry in Otitis Media With Effusion

Children who have OM with effusion often have reduced peak admittance or high negative tympanometric peak pressures (see Fig. 658.5C in Chapter 658 ). However, in the diagnosis of effusion, the tympanometric measure with the greatest sensitivity and specificity is the shape of the tympanogram rather than its peak pressure or admittance. The tympanogram is classified based on shape and peak admittance location. The greater the stiffening of the TM and ME, the lower the peak. As negative pressure within the middle ear increases, the peak becomes more negatively displaced. The more rounded the peak (or, in an absent peak, a flat tympanogram), the higher is the probability that an effusion is present (see Fig. 658.5B in Chapter 658 ). The stage of OM may affect the tympanometric findings. An immobile TM/ME system based on significant effusion, as reflected in flat tympanogram, may evolve into findings of negative ME pressure and later positive pressure as the OM resolves, returning to a normal tympanogram.

Acoustic Reflex Threshold Test

The acoustic reflex threshold test also is part of the immittance test battery. With a properly functioning middle-ear system, admittance at the TM decreases due to the stiffening action of the middle ear muscles (stapedius and, to a lesser extent, tensor tympani). In healthy ears, the stapedial reflex occurs after exposure to loud sounds as a protective mechanism. Admittance instruments are designed to present reflex activating signals (pure tones of various frequencies or noise), either to the same ear or the contralateral ear, while measuring the concomitant changes in admittance. Very small admittance changes that are time locked to presentations of the signal are considered to be a result of middle-ear muscle reflexes. Admittance changes may be absent when the hearing loss is sufficient to prevent the signal from reaching the loudness level necessary to elicit the reflex or when a middle-ear condition affects HLs or introduces sufficient stiffening to obscure reading the reflex activity. The acoustic reflex test also is used in the assessment of SNHL and the integrity of the neurologic components of the reflex arc, including crossed and uncrossed activity of cranial nerves VII and VIII.

Auditory Brainstem Response

The auditory brainstem response (ABR) test is used to screen newborn hearing, confirm hearing loss in young children, obtain ear-specific information in young children, and test children who cannot, for whatever reason, cooperate with behavioral test methods. It also is important in the diagnosis of auditory dysfunction (i.e., estimation of hearing thresholds) and of disorders of the auditory nervous system. The ABR test is a far-field recording of minute electrical discharges from numerous neurons. The stimulus, therefore, must be able to cause synchronous discharge of the large numbers of neurons involved. Stimuli with very rapid onset, such as clicks or tone bursts, must be used. Unfortunately, the rapid onset required to create a measurable ABR also causes energy to be spread in the frequency domain, reducing the frequency-specificity of the response.

The ABR result is not affected by sedation or general anesthesia. Infants and children from about 4 mo to 4 yr of age routinely are sedated to minimize electrical interference caused by muscle activity during testing. The ABR also can be performed in the operating room when a child is anesthetized for another procedure. Children younger than 4 mo of age might sleep for a long enough period of time after feeding to allow an ABR to be done.

The ABR is recorded as 5-7 waves. Waves I, III, and V can be obtained consistently in all age groups; waves II and IV appear less consistently. The latency of each wave (time of occurrence of the wave peak after stimulus onset) increases, and the amplitude decreases with reductions in stimulus intensity; latency also decreases with increasing age, with the earliest waves reaching mature latency values earlier in life than the later waves. Age-specific normative data have been obtained in several studies.

The ABR test has 2 major uses in a pediatric setting. As an audiometric test, it provides information on the ability of the peripheral auditory system to transmit information to the auditory nerve and beyond. It also is used in the differential diagnosis or monitoring of central nervous system pathology. For hearing threshold estimation, the goal is to find the minimum stimulus intensity that yields an observable ABR, generally relying on wave V, the most robust aspect of morphology. Plotting latency versus intensity for various waves also aids in the differential diagnosis of hearing impairment. A major advantage of auditory assessment using the ABR test is that ear-specific threshold estimates can be obtained on infants or patients who are difficult to test. ABR thresholds using click stimuli correlate best with behavioral hearing thresholds in the higher frequencies (1,000-4,000 Hz); responsivity in the low frequencies requires different stimuli (tone bursts/pips or filtered clicks) or the use of masking, neither of which isolates the low-frequency region of the cochlea in all cases, and this can affect interpretation.

The ABR test does not assess “hearing.” It reflects auditory neuronal electrical responses that can be correlated to behavioral hearing thresholds, but a normal ABR result only suggests that the auditory system, up to the level of the midbrain, is responsive to the stimulus used. Conversely, a failure to elicit an ABR indicates an impairment of the system's synchronous response but does not necessarily mean that there is no “hearing.” The behavioral response to sound sometimes is normal when no ABR can be elicited, such as in neurologic demyelinating disease.

Hearing losses that are sudden, progressive, or unilateral are indications for ABR testing. Although it is believed that the different waves of the ABR reflect activity in increasingly rostral levels of the auditory system, the neural generators of the response have not been precisely determined. Each ABR wave beyond the earliest waves probably is the result of neural firing at many levels of the system, and each level of the system probably contributes to several ABR waves. High-intensity click stimuli are used for the neurologic application. The morphology of the response and wave, interwave latencies, and interaural latency differences are examined in respect to age-appropriate forms. Delayed or missing waves in the ABR result often have diagnostic significance.

The ABR and other electrical responses are extremely complex and difficult to interpret. A number of factors, including instrumentation design and settings, environment, degree and configuration of hearing loss, and patients’ characteristics, can influence the quality of the recording. Therefore testing and interpretation of electrophysiologic activity as it possibly relates to hearing should be carried out by trained audiologists to avoid the risk that unreliable or erroneous conclusions will affect a patient's care.

Otoacoustic Emissions

During normal hearing, OAEs originate from the outer hair cells in the cochlea and are detected by sensitive amplifying processes. They travel from the cochlea through the middle ear to the external auditory canal, where they can be detected using miniature microphones. Transient evoked OAEs (TEOAEs) may be used to check the integrity of the cochlea. In the neonatal period, detection of OAEs can be accomplished during natural sleep, and TEOAEs can be used as screening tests in infants and children for hearing down to the 30 dB level of hearing loss. They are less time consuming and elaborate than ABRs, and may be used when behavioral tests cannot be accomplished. TEOAEs are reduced or absent owing to various dysfunctions in the middle and inner ears. They are absent in patients with >30 dB of hearing loss and are not used to determine the hearing threshold; rather, they provide a screen for whether hearing is present at >30-40 dB. CHL, such as OM or congenitally abnormal middle-ear structures, reduce the transfer of TEOAEs and may be incorrectly interpreted as a cochlear hearing disorder. If a hearing loss is suspected based on the absence of OAEs, the ears should be examined for the evidence of pathology, tympanometry should be conducted, and then ABR testing should be used for confirmation and identification of the type, degree, and laterality of hearing loss.

Treatment

With the use of universal hearing screening within the United States, the early diagnosis and treatment of children with hearing loss is common. Testing for hearing loss is possible even in very young children, and it should be done if parents suspect a problem. Any child with a known risk factor for hearing loss should be evaluated in the first 6 mo of life.

Once a hearing loss is identified, a full developmental and speech and language evaluation is needed. Counseling and involvement of parents are required in all stages of the evaluation and treatment or rehabilitation. A CHL often can be corrected through treatment of a middle-ear effusion (i.e., ear tube placement) or surgical correction of the abnormal sound-conducting mechanism. Dependent on the level of hearing loss, children with SNHL should be evaluated for possible hearing aid use by a pediatric audiologist. Current guidelines indicate that within 1 mo of diagnosis of SNHL, children should be fitted with hearing aids , and hearing aids may be fitted for children as young as 1 mo of age. Compelling evidence from the hearing screening program in Colorado shows that identification and amplification before age 6 mo makes a very significant difference in the speech and language abilities of affected children, compared with cases identified and amplified after the age of 6 mo. In these children, repeat audiologic testing is needed to reliably identify the degree of hearing loss and to fine-tune the use of hearing aids. Hearing aids remain the rehabilitative device of choice, in the context of an individually designed treatment plan, for children with mild, moderate, or moderately severe CHL, mixed HL, or SNHL. For children with severe or profound SNHL, a trial with hearing aids is needed to determine if this approach is sufficient for the development of language; other options may need to be explored if there are indications that speech and language are delayed with a hearing aid in this HL group. Importantly, efficacy of hearing aids depends on their consistent use. There is great variability in how often children wear their hearing aids. Though there is no specific recommendation regarding the minimal number of hours per day that the hearing aids should be worn, parents should be encouraged to have their child use hearing aids full-time in order to facilitate speech and language development.

When it is clear that hearing aids are not providing the auditory stimulation needed to support language development, the parents require counseling to consider alternative treatments. A cochlear implant may be necessary to facilitate intelligible oral communication (i.e., oralism). This approach requires years of intensive speech and language training and is dependent on providing the best possible auditory stimulation possible. This option is very attractive to parents with hearing because it is the most familiar form of communication to them. While there is a heavy emphasis in the medical world valuing the development of oral language (speech production), parents should also be provided with information about alternatives such as sign language, total communication, and cued speech. Each of these communication modalities has advantages and disadvantages. Sign language allows the child to develop a language system early and can support academic training. The consequence of this option is that the dominant hearing world does not interact easily with users of sign language and the child is likely to become part of the deaf community and may face significant challenges integrating into hearing society. Such possibilities as academic success and college/graduate school training are not excluded by the use of sign language, but a narrower set of venues may be available to accommodate the child's learning needs. While this option is acceptable to deaf parents already in the deaf culture, many hearing parents are uncomfortable with this path for their child. This option also requires that the parents become fluent in sign language.

Total communication is an educational philosophy in which both sign and oral language are encouraged. In theory, the two systems support and clarify information transfer and enhance academic progress. Depending on the particular school and/or teachers, one system may be emphasized over the other. Cued speech is an approach in which the development of oral language is supported by a system of hand gestures near the mouth and throat to disambiguate confusions that result from lip reading alone. This system can be highly successful in supporting spoken language, and requires that parents become fluent in the use of the cues. Other factors should be taken into account in making the choice of communication modality. Significant comorbidities, such as visual impairment or other developmental delays, may limit the ability of a child to derive benefit from some choices. Support for the parents in making this decision may require counseling from an audiologist, social worker, deaf educator, and/or psychologist. Organizations of parents of deaf children, such as the A.G. Bell Association and the John Tracy Clinic, can provide a wealth of support and information to parents in this process.

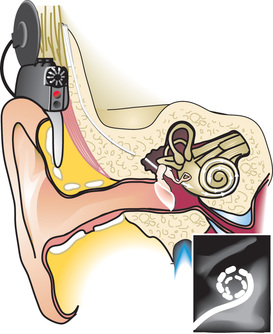

Infants and young children with profound congenital or prelingual onset of deafness have benefited from multichannel cochlear implants (Fig. 655.4 ). Cochlear implants are systems which combine internal (surgically implanted) and externally worn components. These implants consist of four main components: the externals, which include a microphone, a minicomputer sound (speech) processor, a transmitter; and the internal, an electrode array. These implants bypass injury to the organ of Corti and provide neural stimulation through the digitization of auditory stimuli into digital radiofrequency impulses. Specifically, sound is initially detected by the microphone and then is processed by the speech processor. The speech processor is programmed by an audiologist to implement (the manufacturer's) proprietary speech processing strategies that are highly sophisticated manipulations of the input signal. Signals from the speech processor are transmitted across the skin by an FM signal to the internal receiver, which converts these signals to electrical impulses. Finally, these electrical impulses are sent to the electrode array located in the cochlea, where electrical fields are created that act on the cochlear nerve. This is in contrast to the transmission of sound in a healthy ear, which involves the transmission of sound vibrations to the hair cells of the cochlea, the release of ions and neurotransmitters in the cochlea, and the transmission of neural impulses to the cochlear nerve and then the brain.

Surgical implantation is done under general anesthesia and involves mastoidectomy and widening of the facial recess. The approach to the cochlea is through the facial recess. After fastening the internal stimulator package in the mastoid process, the cochlea must be opened in order to insert the electrode array, which is most commonly done through an opening made in the round window. Care is taken to avoid contamination of the cochlear fluids by bone dust or blood. After the cochlea is closed, generally with fascia, the wound is closed. An audiologist performs testing in the operating room to verify the functional integrity of the implanted device. These electrophysiologic responses from the VIII nerve are critical to determining a starting point for programming the external device after the wound has healed. A plain x-ray is often performed in the operating room as well to document placement of the array in the scala tympani.

The healing process following surgery is approximately 3-4 wk for a child. During this time, the child cannot hear. When the child is brought in for the first stimulation using the external equipment, programs are developed that provide first access to sound. The methods to create the programs entail a combination of electrophysiologic measures and behavioral testing that is similar to the pediatric audiologic assessments described above. The initial programs are a starting point, followed by modifications and enhancements that are based on the parents’ and audiologist's observations of changing auditory awareness and vocalization.

When parents elect to pursue cochlear implantation for their child, a long-term commitment is necessary to ongoing engagement with a team of rehabilitation specialists. Audiologic management entails consistent monitoring of the child's response to the implant and impact on emerging language skills. Speech and language therapy is necessary to stimulate language and to teach parents skills to support speech development. The child should be in a preschool setting in which speech, language, social, and academic precursor skills are fostered. For some parents, this engagement is very challenging, not only in terms of time required but also in terms of the emotional consequences of attempting to minimize the impact of hearing loss on their child's future; support for the parents is often needed in this process from the team.

A serious possible complication of cochlear implantation is pneumococcal meningitis. All children receiving a cochlear implant must be vaccinated with the pneumococcal polyvalent vaccine PCV13 (Table 655.9 ), and rates of pneumococcal meningitis have declined considerably since implementation of the vaccine.

Table 655.9

Recommended Pneumococcal Vaccination Schedule for Persons With Cochlear Implants

| AGE AT FIRST PCV13 DOSE (mo)* | PCV12 PRIMARY SERIES | PCV13 ADDITIONAL DOSE | PPV23 DOSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-6 | 3 doses, 2 mo apart † | 1 dose at 12-15 mo of age ‡ | Indicated at ≥24 mo of age § |

| 7-11 | 2 doses, 2 mo apart † | 1 dose at 12-15 mo of age ‡ | Indicated at ≥24 mo of age § |

| 12-23 | 2 doses, 2 mo apart ¶ | Not indicated | Indicated at ≥24 mo of age § |

| 24-59 | 2 doses, 2 mo apart ¶ | Not indicated | Indicated § |

| ≥60 | Not indicated | | Not indicated | | Indicated |

* A schedule with a reduced number of total 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) doses is indicated if children start late or are incompletely vaccinated. Children with a lapse in vaccination should be vaccinated according to the catch-up schedule (see Chapter 209 ).

† For children vaccinated at younger than age 1 yr, minimum interval between doses is 4 wk.

‡ The additional dose should be administered 8 wk or more after the primary series has been completed.

§ Children younger than age 5 yr should complete the PCV13 series first; 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23) should be administered to children 24 mo of age or older 8 wk or more after the last dose of PCV13 (see Chapter 182 ). (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices: Preventing pneumococcal disease among infants and young children: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices [ACIP]. MMWR Recomm Rep 49[RR-9]:1–35, 2000, and Licensure of a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine [PCV13] and recommendations for use among children—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices [ACIP]. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 59(9):258–261, 2010.)

¶ Minimum interval between doses is 8 wk.

| PCV13 is not recommended generally for children age 5 yr or older.

PCV , Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; PPV , pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine.

From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices: Pneumococcal vaccination for cochlear implant candidates and recipients: Updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 52(31):739–740, 2003.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved cochlear implantation in patients over 12 mo of age with severe to profound bilateral hearing loss not benefitting from hearing aids; however, off-label use of cochlear implants has demonstrated efficacy in those younger than 12 mo and in children with residual hearing. Cochlear implantation before age 2 yr improves hearing and speech, enabling more than 90% of children to be in mainstream education. Most develop age-appropriate auditory perception and oral language skills. There is increasing evidence to support expansion of the candidacy for cochlear implantation in children to be based on outcomes of advanced testing using speech stimuli, especially in noise. To date, implantation of children with devices that combine acoustic input (similar to a hearing aid) with electric stimulation from a cochlear implant has not been approved by the FDA. These devices, called electroacoustic cochlear implants, or hybrids, may offer hope for children using hearing aids but struggling with noise in the classroom or social contexts.

Management of idiopathic sudden SNHL is controversial and has included oral prednisone, intratympanic (also called transtympanic) dexamethasone perfusion, or a combination of both; the latter combination may be the most useful.

Genetic Counseling

Families of children with the diagnosis of SNHL or a syndrome associated with SNHL and/or CHL should be referred for genetic counseling. This will give the parents an idea of the likelihood of similar diagnoses in future pregnancies, and the geneticist can assist in the evaluation and testing of the patient to establish a diagnosis.