Osteogenesis Imperfecta

Joan C. Marini

Osteoporosis is fragility of the skeletal system and a susceptibility to fractures of the long bones or vertebral compressions from mild or inconsequential trauma (see Chapter 726 ). Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI ) (brittle bone disease), the most common genetic cause of osteoporosis, is a generalized disorder of connective tissue. The spectrum of OI is extremely broad, ranging from forms that are lethal in the perinatal period to a mild form in which the diagnosis may be equivocal in an adult.

Etiology

Structural or quantitative defects in type I collagen cause the full clinical spectrum of OI (types I-IV). Type I collagen is the primary component of the extracellular matrix of bone and skin. Between 15% and 20% of patients clinically indistinguishable from OI do not have a molecular defect in type I collagen (Table 721.1 ). These cases are caused by defects in genes whose protein products interact with type I collagen. One group of patients has overmodified collagen, with similar biochemical findings to those with collagen structural defects and severe or lethal OI bone dysplasia. These cases are caused by recessive null mutations in any of the three components of the collagen prolyl 3-hydroxylation complex, prolyl 3-hydroxylase 1 (coded by the LEPRE1 gene on chromosome 1p34.1) or its associated protein, CRTAP, or cyclophilin B (CyPB, encoded by PPIB ). A second set of cases without collagen defects have biochemically normal collagen. Defects in IFITM5 and SERPINF1 account for defects in mineralization in types V and VI OI, while mutations in SERPINH1 , encoding the collagen chaperone HSP47, and FKBP10 , encoding the peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase FKBP65, cause types X and XI OI, respectively. Rare mutations in BMP1, the enzyme that processes the C-propeptide of type I collagen, also cause a recessive form of OI. The most recent set of genes added to the recessive OI causative panel (SP7 , type XIII OI; TMEM38B , type XIV OI; WNT1 , type XV OI; CREB3L1 , type XVI OI, SPARC , type XVII OI, and MBTPS2 , type XVIII OI) not only are involved in osteoblast differentiation but also affect collagen synthesis and cross linking. There are very few individuals with OI whose genetic defect is not in a known causative gene.

Table 721.1

Osteogenesis Type, Gene Defects, and Phenotypes

| OI TYPE | INHERITANCE | DEFECTIVE GENE | DEFECTIVE PROTEIN |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEFECTS IN COLLAGEN SYNTHESIS AND STRUCTURE | |||

| Type I, II, III, IV | AD | COL1A1 or COL1A2 | α1(1) or α2(1) collagen |

| DEFECTS IN BONE MINERALIZATION | |||

| Type V | AD | IFITM5 | BRIL |

| Type VI | AR | SERPINF1 | PEDF |

| DEFECTS IN COLLAGEN MODIFICATION | |||

| Type VII | AR | CRTAP | CRTAP |

| Type VIII | AR | LEPRE1 | P3H1 |

| Type IX | AR | PPIB | PPIB (CyPB) |

| DEFECTS IN COLLAGEN PROCESSING AND CROSSLINK | |||

| Type X | AR | SERPINH1 | HSP47 |

| Type XI | AR | FKBP10 | FKBP65 |

| Unclassified | AR | PLOD2 | LH2 |

| Type XII | AR | BMP1 | BMP1 |

| DEFECTS IN OSTEOBLAST DIFFERENTIATION AND FUNCTION | |||

| Type XIII | AR | SP7 | SP7 (OSTERIX) |

| Type XIV | AR | TMEM38B | TRIC-B |

| Type XV | AR/AD | WNT1 | WNT1 |

| Type XVI | AR | CREB3L1 | OASIS |

| Type XVII | AR | SPARC | SPARC (Osteonectin) |

| Type XVIII | XR | MBTPS2 | S2P |

AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; XR, X-linked recessive.

From Kang H, Aryal ACS, Marini JC: Osteogenesis imperfecta: new genes reveal novel mechanisms in bone dysplasia. Transl Res 181:27–48, 2017, Table 1, p. 29.

Epidemiology

The autosomal dominant forms of OI occur equally in all racial and ethnic groups, whereas recessive forms occur predominantly in ethnic groups with consanguineous marriages or as a founder effect in an isolated population. The West African founder mutation for type VIII OI has a carrier frequency of 1 in 200-300 among African Americans. The collective incidence of all types of OI detectable in infancy is approximately 1 in 20,000. There is a similar incidence of the mild form OI type I.

Pathology

The collagen structural mutations in OI cause the bones to be globally abnormal. The bone matrix contains abnormal type I collagen fibrils and relatively increased levels of types III and V collagen. Several noncollagenous proteins of bone matrix are also reduced. Bone cells contribute to OI pathology, with abnormal osteoblast differentiation and increased numbers of active bone resorbing osteoclasts. The hydroxyapatite crystals deposited on this matrix are poorly aligned with the long axis of fibrils, and there is paradoxical hypermineralization of bone.

Pathogenesis

Type I collagen is a heterotrimer composed of 2 α1(I) chains and 1 α2(I) chain. The chains are synthesized as procollagen molecules with short globular extensions on both ends of the central helical domain. The helical domain is composed of uninterrupted repeats of the sequence Gly-X-Y, where Gly is glycine, X is often proline, and Y is often hydroxyproline. The presence of glycine at every third residue is crucial to helix formation because its small side chain can be accommodated in the interior of the helix. The chains are assembled into trimers at their carboxyl ends; helix formation then proceeds linearly in a carboxyl to amino direction. Concomitant with helix assembly and formation, helical proline and lysine residues are hydroxylated by prolyl 4-hydroxylase and lysyl hydroxylase, and some hydroxylysine residues are glycosylated.

Collagen structural defects are predominantly of two types: 80% are point mutations causing substitutions of helical glycine residues or crucial residues in the C-propeptide by other amino acids, and 20% are single exon splicing defects. The clinically mild OI type I has a quantitative defect, with null mutations in one α1(I) allele leading to a reduced amount of normal collagen.

The glycine substitutions in the two α chains have distinct genotype–phenotype relationships. One third of mutations in the α1 chain are lethal, and those in α2(I) are predominantly nonlethal. Two lethal regions in α1(I) align with major ligand binding regions of the collagen helix. Lethal mutations in α2(I) occur in eight regularly spaced clusters along the chain that align with binding regions for matrix proteoglycans in the collagen fibril.

Classical OI (Sillence types I-IV) is an autosomal dominant disorder, as is type V OI. Some familial recurrences of OI are caused by parental mosaicism for dominant collagen mutations. Recessive OI accounts for 7–10% of newly diagnosed OI in North America. Three recessive types are caused by null mutations in the genes coding for the components of the collagen prolyl 3-hydroxylation complex in the endoplasmic reticulum (LEPRE1 , CRTAP, or PPIB) . It is not yet clear whether absence of the complex itself or of the modification is the crucial feature of these types of recessive OI. Other recessive types are caused by null mutations in genes whose products are involved in collagen folding (SERPINH1, FKBP10 ), or mineralization (SERPINF1) , or defects in osteoblast differentiation and function (SP7, TMEM38B, WNT1, CREB3L1, SPARC, MBTPS2 ).

Clinical Manifestations

Classical OI was described with the triad of fragile bones, blue sclerae, and early deafness, although most cases do not have all of these features. The Sillence classification divides OI into four types based on clinical and radiographic criteria. Types V and VI were later proposed based on histologic distinctions. Subsequent types VII-XVIII were based on identification of the molecular defect, followed by clinical description.

Osteogenesis Imperfecta Type I (Mild)

OI type I is sufficiently mild that it is often found in large pedigrees. Many type I families have blue sclerae, recurrent fractures in childhood, and presenile (i.e. beginning in early adulthood) hearing loss (30–60%). Both types I and IV are divided into A and B subtypes, depending on the absence (A) or presence (B) of dentinogenesis imperfecta, a type of dentin dysplasia resulting in discolored (often blue-gray or amber), translucent teeth that wear down rapidly or break. Other possible connective tissue abnormalities include hyperextensible joints, easy bruising, thin skin, joint laxity, scoliosis, wormian bones, hernia, and mild short stature compared with family members. Fractures result from mild to moderate trauma but decrease after puberty.

Osteogenesis Imperfecta Type II (Perinatal Lethal)

Infants with OI type II may be stillborn or die in the 1st yr of life. Birthweight and length are small for gestational age. There is extreme fragility of the skeleton and other connective tissues. There are multiple intrauterine fractures of long bones, which have a crumpled appearance on radiographs. There are striking micromelia and bowing of extremities; the legs are held abducted at right angles to the body in the frogleg position. Multiple rib fractures create a beaded appearance, and the small thorax contributes to respiratory insufficiency. The skull is large for body size, with enlarged anterior and posterior fontanels. Sclerae are dark blue-gray. The cerebral cortex has multiple neuronal migration and other defects (agyria, gliosis, periventricular leukomalacia).

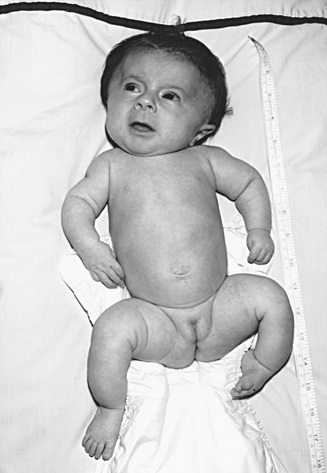

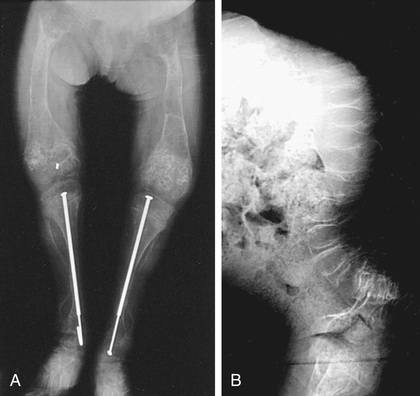

Osteogenesis Imperfecta Type III (Progressive Deforming)

OI type III is the most severe nonlethal form of OI and results in significant physical disability. Birthweight and length are often low normal. Fractures usually occur in utero. There is relative macrocephaly and triangular facies (Fig. 721.1 ). Postnatally, fractures occur from inconsequential trauma and heal with deformity. Disorganization of the bone matrix results in a “popcorn” appearance at the metaphyses (Fig. 721.2 ). The rib cage has flaring at the base, and pectal deformity is frequent. Virtually all type III patients have scoliosis and vertebral compression. Growth falls below the curve by the 1st yr; all type III patients have extreme short stature. Scleral hue ranges from white to blue. Dentinogenesis imperfecta, hearing loss, and kyphoscoliosis may be present or develop over time.

Osteogenesis Imperfecta Type IV (Moderately Severe)

Patients with OI type IV can present at birth with in utero fractures or bowing of lower long bones. They can also present with recurrent fractures after ambulation and have normal to moderate short stature. Most children have moderate bowing even with infrequent fractures. Children with OI type IV require orthopedic and rehabilitation intervention, but they are usually able to attain community ambulation skills. Fracture rates decrease after puberty. Radiographically, they are osteoporotic and have metaphyseal flaring and vertebral compressions. Scleral hue may be blue or white.

Osteogenesis Imperfecta Type V (Hyperplastic Callus) and Type VI Hyperosteoidosis (Mineralization Defect)

Types V and VI OI patients clinically have OI similar in skeletal severity to types IV and III, respectively, but they have distinct findings on bone histology. Type V patients also usually have some combination of hyperplastic callus, calcification of the interosseous membrane of the forearm, and/or a radiodense metaphyseal band. They constitute <5% of OI cases. All type V OI patients are heterozygous for the same mutation in IFITM5 , which generates a novel start codon for the bone protein BRIL. Ligamentous laxity may be present; blue sclera or dentinogenesis imperfecta are not present. Patients with type VI OI have progressive deforming OI that does not manifest at birth. They have distinctive bone histology with broad osteoid seams and fish-scale lamellation under polarized light, caused by deficiency of pigment epithelium derived factor, encoded by SERPINF1 . Types V and VI are connected in intracellular osteoblast pathways—SERPINF1 transcripts are increased in type V OI, while IFITM5 transcripts are decreased in type VI OI.

Osteogenesis Imperfecta Types VII, VIII, and IX (Autosomal Recessive)

Types VII and VIII patients overlap clinically with types II and III OI but have distinct features including white sclerae, rhizomelia, and small to normal head circumference. Surviving children have severe osteochondrodysplasia with extreme short stature and dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry L1-L2 z-score in the −6 to −7 range. Type IX OI is very rare (only 8 cases reported). The severity is quite broad, ranging from lethal to moderately severe. These children have white sclerae but do not have rhizomelia.

Osteogenesis Imperfecta Types X and XI (Autosomal Recessive)

There have been several reports of severe to lethal type X OI caused by defects affecting the serine-type endopeptidase inhibitor domain of HSP47. This domain is responsible for the HSP47 chaperone function that helps to maintain the folded state of procollagen heterotrimers. HSP47 and FKBP65, the protein responsible for type XI OI, cooperate in collagen synthesis. Type XI OI is a more prevalent recessive form with a moderate to severe skeletal phenotype, including white sclerae and normal teeth. Congenital contractures of large joints may occur with the same mutations that cause only skeletal fragility, even in sibships. At the opposite end of the spectrum, a deletion of a single tyrosine residue causes Kuskokwim syndrome, a congenital contracture disorder with very mild vertebral findings and osteopenia. Defects in FKBP10 decrease collagen crosslinking in matrix because FKBP65 is the foldase for lysyl hydroxylase 2, which hydroxylates collagen telopeptide residues important for cross linking.

High Bone Mass Osteogenesis Imperfecta (Cleavage of the Procollagen C-Propeptide)

Autosomal dominant mutations in the C-propeptide cleavage site of procollagen or recessive defects in the enzyme responsible for its cleavage cause bone fragility with normal or elevated dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry bone density z-scores. Individuals with dominant mutations have normal stature, white sclerae and teeth, and mild to moderate OI. Null mutations in BMP1 lead to a more severe skeletal phenotype with short stature, scoliosis and bone deformity, because BMP1 has other substrates in addition to type I collagen.

Defects in Osteoblast Differentiation (Types XIII-XVIII OI)

The most recent functional grouping of genes causing recessive OI (types XIII to XVIII) affect osteoblast differentiation and are collagen related. SP7 (type XIII OI) regulates osteoblast differentiation and is critical for bone formation. TMEM38B (type XIV OI) defects are clinically indistinguishable from type IV OI. TMEM38B encodes the endoplasmic reticulum membrane cation channel TRIC-B, which affects calcium flux from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytoplasm. Since many enzymes involved in collagen metabolism are calcium dependent, collagen synthesis is globally dysregulated in the absence of TRIC-B, with significant intracellular retention. Collagen posttranslational modification is also impaired, leading to underhydroxylation of the collagen helix. WNT1 (type XV OI) recessive defects cause severe progressive deforming OI. Wnt signaling pathway activation through the Frizzled receptor on the osteoblast surface increases bone mass, but deficiency of Wnt decreases it. SPARC (type XVII OI), also known as osteonectin, is a glycoprotein component of extracellular matrix. Defects in residues important for SPARC binding to collagen were reported in two cases of moderate to severe OI.

The genes MBTPS2 and CREB3L1 , causing types XVIII and XVI OI, respectively, encode proteins involved in regulated intramembrane proteolysis (RIP). MBTPS2 encodes the transmembrane Golgi protein site-2 protease (S2P), that acts in successively with S1P to activate regulatory molecules in times of cell stress. OASIS, encoded by CREB3L1 , is an RIP substrate.

Interestingly, missense substitutions in S2P in OI patients result in underhydroxylation of the collagen residue important for crosslinking of collagen in matrix, thus impairing bone strength. In OASIS-null mice, collagen transcription has been shown to be impaired.

Other Genes for Osteogenesis Imperfecta

A very small percentage of OI patients cannot be accounted for by mutations known OI genes.

Laboratory Findings

DNA sequencing is the first diagnostic laboratory test; several Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified sequencing labs offer panels to test for dominant and recessive OI. Mutation identification is useful to determine the type with certainty and to facilitate family screening and prenatal diagnosis. It is also possible to screen for type VI OI by the determination of serum pigment epithelium-derived factor level, which is severely reduced in this type.

If dermal fibroblasts are obtained these can be useful for determining the level of transcripts of the candidate gene and for collagen biochemical testing, which is positive in most cases of types I-IV and IX OI, and in all cases of VII/VIII OI. In OI type I, the reduced amount of type I collagen results in an increase in the ratio of type III to type I collagen on gel electrophoresis.

Severe OI can be detected prenatally by level II ultrasonography as early as 16 wk of gestation. OI and thanatophoric dysplasia may be confused. Fetal ultrasonography might not detect OI type IV and rarely detects OI type I. For recurrent cases, chorionic villus biopsy can be used for biochemical or molecular studies. Amniocytes produce false-positive biochemical studies but can be used for molecular studies in appropriate cases.

In the neonatal period, the normal to elevated alkaline phosphatase levels present in OI distinguish it from hypophosphatasia. During the school-age period, children with type VI OI have notably elevated serum alkaline phosphatase.

Complications

The morbidity and mortality of OI are cardiopulmonary. Recurrent pneumonias and declining pulmonary function occur in childhood, and cor pulmonale is seen in adults.

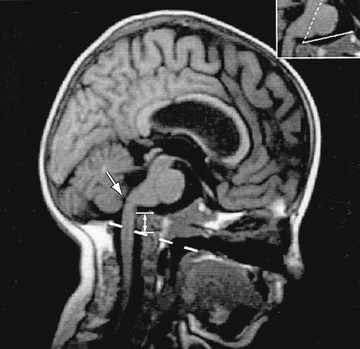

Neurologic complications include basilar invagination, brainstem compression, hydrocephalus, and syringohydromyelia. Most children with OI types III and IV have basilar invagination, but brainstem compression is uncommon. Basilar invagination is best detected with spiral CT of the craniocervical junction (Fig. 721.3 ).

Treatment

There is no cure for OI. For severe nonlethal OI, active physical rehabilitation in the early years allows children to attain a higher functional level than orthopedic management alone. Children with OI type I and some with type IV are spontaneous ambulators. Children with types III, IV, V, VI, and XI OI benefit from gait aids and a program of swimming and conditioning. Severely affected patients require a wheelchair for community mobility but can acquire transfer and self-care skills. Teens with OI can require psychologic support with body image issues. Growth hormone improves bone histology in growth-responsive children (usually types I and IV).

Orthopedic management of OI is aimed at fracture management and correction of deformity to enable function. Fractures should be promptly splinted or cast; OI fractures heal well, and cast removal should be aimed at minimizing immobilization osteoporosis. Correction of long-bone deformity requires an osteotomy procedure and placement of an intramedullary rod.

A several-year course of treatment of children with OI with bisphosphonates (IV pamidronate or oral olpadronate or risedronate) confers some benefits. Bisphosphonates decrease bone resorption by osteoclasts; OI patients have increased bone volume that still contains the defective collagen. Bisphosphonates are more beneficial for vertebrae (trabecular bone) than long bones (cortical bone). Treatment for 1-2 yr results in increased L1-L4 dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry and, more importantly, improved vertebral compressions and area. However, follow-up of bisphosphonate-treated children has shown that the incidence of scoliosis is unchanged even in children treated early, although there was a modest delay in progression in type III OI. The relative risk of long-bone fractures is modestly decreased by several years of bisphosphonates. However, the material properties of long bones are weakened by prolonged treatment and nonunion after osteotomy is increased. There is no effect of bisphosphonates on mobility scores, muscle strength, or bone pain. Limiting treatment duration to 2-3 yr in mid-childhood can maximize the benefits and minimize the detriment to cortical material properties. Benefits appear to persist several years after the treatment interval, and alternation of treatment intervals and drug holidays may be beneficial. Side effects include abnormal long-bone remodeling, increased incidence of fracture nonunion, and osteopetrotic-like brittleness to bone.

Prognosis

OI is a chronic condition that limits both life span and functional level. Infants with OI type II usually die within months to 1 yr of life. An occasional child with radiographic type II and extreme growth deficiency survives to the teen years. Persons with OI type III have a reduced life span with clusters of mortality from pulmonary causes in early childhood, the teen years, and the 40s. OI types I, IV, and V OI are compatible with a full life span. The oldest reported individuals with type VIII are in their 3rd decade, and some with type XI are in their 4th decade. The long-term prognosis for most recessive types is still emerging, and many adults with OI have not had molecular testing.

Individuals with OI type III are usually wheelchair dependent. With aggressive rehabilitation, they can attain transfer skills and household ambulation. OI type IV children usually attain community ambulation skills either independently or with gait aids.

Genetic Counseling

For autosomal dominant OI, the risk of an affected individual passing the gene to the individual's offspring is 50%. An affected child usually has about the same severity of OI as the parent; however, there is variability of expression, and the child's condition can be either more or less severe than that of the parent. The empirical recurrence risk to an apparently unaffected couple of having a second child with OI is 5–7%; this is the statistical chance that 1 parent has germline mosaicism. The collagen mutation in the mosaic parent is present in some germ cells and may be present in somatic tissues. If a parent is a mosaic carrier, the risk of recurrence may be as high as 50%.

For recessive OI, the recurrence risk is 25% per pregnancy. No known individual with severe nonlethal recessive OI has had a child.