Osteoporosis

Catherine M. Gordon

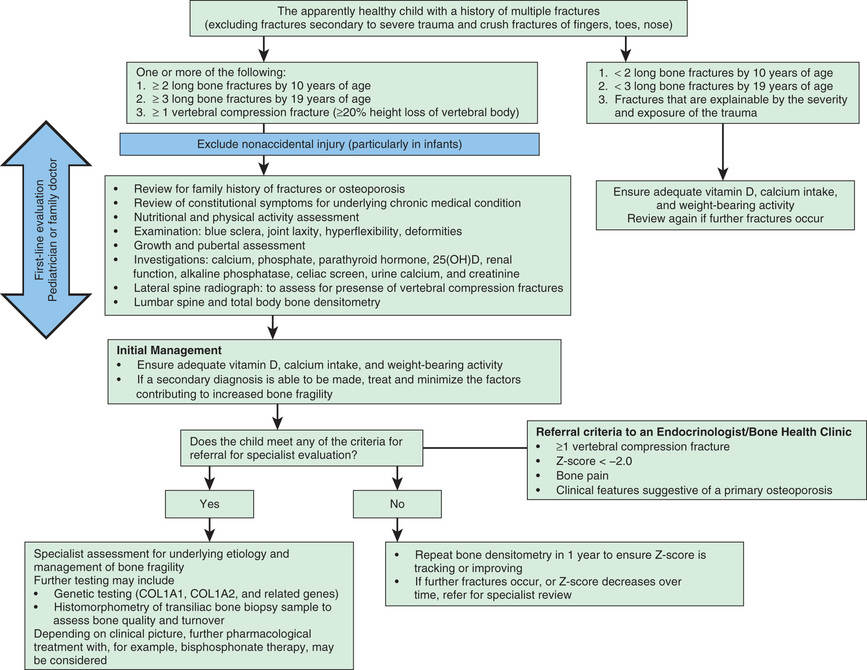

Osteoporosis, the most common bone disorder in adults, is relatively uncommon in children, and the criteria that underlie this diagnosis in pediatric patients are a source of debate. This disorder is characterized by diminished bone volume and a marked increase in the prevalence of fractures. In contrast to osteomalacia, which shows undermineralization and normal bone volume, histologic sections of bone in all forms of osteoporosis reveal a normal degree of mineralization but a reduction in the volume of bone, especially trabecular bone (vertebral bone). The diagnosis of osteoporosis in children and adolescents requires evidence of skeletal fragility (fractures) independent of a bone density measurement and, in the pediatric age group, may be primary or secondary (Table 726.1 ; Fig. 726.1 ). The primary osteoporoses can be divided into heritable disorders of connective tissue, including osteogenesis imperfecta (see Chapter 721 ), Bruck syndrome, osteoporosis-pseudoglioma syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (see Chapter 679 ), Marfan syndrome (see Chapter 722 ), homocystinuria, and idiopathic juvenile osteoporosis. Secondary forms of osteoporosis include various neuromuscular disorders, chronic illness, endocrine disorders, and drug-induced and inborn errors of metabolism, including lysinuric protein intolerance and Gaucher disease.

When no obvious primary or secondary cause can be detected, idiopathic juvenile osteoporosis should be considered, especially if the following clinical features are evident: onset before puberty, long-bone and lower back pain, vertebral fractures, long-bone and metatarsal fractures, a washed-out appearance of the spine and appendicular skeleton on standard radiographs, and improvement of bone density after puberty. Trabecular bones such as the spine and metatarsals are particularly affected by atraumatic fractures.

In general, blood values of minerals, vitamin D metabolites, alkaline phosphatase, and parathyroid hormone are normal. Evaluation of bone mineral content and bone density by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry or, less often, quantitative CT shows markedly reduced values. Several modes of therapy (including oral calcium supplements, calcitriol, bisphosphonates, and calcitonin) have been used with some success in individual conditions, but the effect of these treatments is difficult to gauge because spontaneous recovery occurs after the onset of puberty in more than 75% of cases.

Osteoporosis-pseudoglioma syndrome is an autosomal recessive disorder manifested by variable age at onset, low bone mass, fractures in childhood, and abnormal eye development; the defective gene has been mapped to chromosome 11q12-13. The mutation is a loss of function in the gene for low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5. Interestingly, gain-of-function mutations result in a gene product that increases bone density.

The life-cycle implications of either significant demineralization or osteoporosis in childhood need to be stressed. Events in childhood influence peak bone mass, and late adolescence is a period of rapid bone mineral accretion. Peak bone mass is typically achieved by 20-25 yr of age (depending on the bone measured), and the contribution during childhood is considerable. A number of measures influence bone mass: vitamin D, preferably as cholecalciferol (400-800 IU daily), calcium intake (≥1,200 mg/day in adolescents), and weight-bearing exercise throughout childhood. Weight-bearing exercise enhances bone formation and reduces bone resorption. Factors that can prevent acquisition of peak bone mass include the use of alcohol and tobacco. Excellent and convenient sources of dietary calcium include dairy products, but also bony fish, green vegetables, and calcium-supplemented drinks (e.g., orange juice). Yogurt and hard cheeses can be used in many lactase-deficient children. Because it appears that adult-onset osteoporosis stems primarily from genetic factors, representing a complex trait interaction, specific interventions during childhood to augment bone mass are not available.

The treatment of secondary osteoporosis is best achieved by treating the underlying disorder when feasible (see Fig. 726.1 ). Hypogonadism should be treated with hormone replacement therapy, but in adolescent girls, nutritional issues should first be addressed and, ultimately, prescription of transdermal over oral estrogen (see Chapter 711 ). Calcium intake should be increased to 1,500-2,000 mg/day. In glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis, an emphasis is placed on the lowest possible dose to prevent disease activity (e.g., in children with inflammatory bowel disease) with alternate-day dosing or, when appropriate, topical (e.g., eczema) or inhaled (e.g., asthma) glucocorticoids. Special diets for inborn errors of metabolism are also appropriate, as well as enzymatic replacement for diseases such as hypophosphatasia, a genetic disorder leading to deficient endogenous alkaline phosphatase production and defective bone mineralization. Screening for celiac disease should be carried out in unexplained cases of low bone mass, as adherence to a gluten-free diet can significantly enhance bone health in these patients (see Chapter 338.2). Treatment with bisphosphonates that inhibit bone resorption in certain secondary (glucocorticoid-induced) and adult-onset osteoporosis has been successful. Bisphosphonate therapy can also be beneficial for children and adolescents with osteogenesis imperfecta and cerebral palsy.