INFLUENZA ON A TROOPSHIP: THE ATLANTIC, SEPTEMBER–OCTOBER 1918

Henry A. May: from History of the U.S.S. Leviathan

Lieutenant Commander Henry A. May, a senior medical officer assigned to the troopship USS Leviathan during the crossing of September 29–October 7, 1918 (the same voyage that brought Gibson and his regiment to France), recorded the progress of the disease as it spread among the passengers and crew. An estimated 46,000 members of the U.S. armed forces died of influenza in 1918–19.

COURSE OF THE EPIDEMIC

THIS WAS influenced materially by these main factors:

First, the widespread infection of several organizations before they embarked, and their assignment to many different parts of the ship.

Second, the type of men comprising the most heavily infected group. These men were particularly liable to infection.

Third, the absolute lassitude of those becoming ill caused them to lie in their bunks without complaint until their infection had become profound and pneumonia had begun. The severe epistaxis which ushered in the disease in a very large proportion of the cases, caused a lowering of resisting powers which was added to by fright, by the confined space, and the motion of the ship. Where pneumonia set in, not one man was in condition to make a fight for life.

As noted above, the sick bay was filled a few hours after leaving Hoboken. All pneumonia cases were placed in one isolation ward at the beginning, and another isolation unit was set aside for measles and mumps, both of which diseases were present among the troops. The other isolation units were first filled with influenza cases and later with pneumonias. Until the fifth day of the voyage, few patients could be sent to duty because of great weakness following the drop in temperature as they grew better. Only the worst cases in E-deck ward were sent to sick bay at any time, and all were potentially pneumonias. The E-deck ward was more than full all the time and there were many ill men in various troop spaces in other parts of the ship.

There are no means of knowing the actual number of sick at any one time, but it is estimated that fully 700 cases had developed by the night of September 30th. They were brought to the sick bay from all parts of the ship, in a continuous stream, only to be turned away because all beds were occupied. Most of them then lay down on the decks, inside and out, and made no effort to reach the compartment where they belonged. In fact practically no one had the slightest idea where he did belong, and he left his blankets, clothing, kit, and all his possessions to be salvaged at the end of the voyage.

During October 1st, every effort was made to increase hospital space below, as noted above. The heretofore satisfactory arrangements for army sick call were not adhered to by the army medical officers, and hundreds of men applied for treatment at the E-deck ward instead of going to the twelve outlying sick call stations. On this day, Colonel Decker, the Chief Army Surgeon, became ill. As he was the only army medical officer who had had army experience in administrative matters there was now no competent head to the army organization. Two other medical officers also became ill and remained in their rooms to the end of the voyage.

Late in the evening of this day the E-deck ward was opened on the starboard side and was filled before morning. Twenty army nurses were detailed for duty during the night. When patients were brought up, their mates carefully left their blankets and clothing below and scouting parties had to be sent through the compartments to gather up all loose blankets for use of the sick. Fortunately we had about 100 army blankets in the medical storeroom which had been salvaged on other voyages. These were used while they lasted.

HORRORS OF WAR

The conditions during this night cannot be visualized by any one who has not actually seen them.

The morning of October 2nd brought no relief. Things seemed to grow worse instead of better. Cleaning details were demanded of the army, but few men responded. Those who came would stay awhile and wander away, never to be seen again. No N.C.O.’s were sent, and there was no organization for control. The nurses made a valiant effort to clean up and the navy hospital corpsmen did marvels of work, but always against tremendous odds. Only by constant patrolling between the bunks could any impression be made upon the litter and finally our own sailors were put on the job. They took hold like veterans and the place was kept respectably clean thereafter.

The first death from pneumonia occurred on this day, and the body was promptly embalmed and encased in a navy standard casket.

When evening came no impression had been made upon the great number of sick men about the decks and in their own bunks. So arrangements were made to enlarge the hospital space by including the port side of E.R.S. 2. On October 3rd this was accomplished and from that time to the end of the voyage we had enough bunks to accommodate practically all the worst cases. Three deaths occurred this day and all were embalmed and encased. After going through the hospital and troop spaces that night it was estimated that there were about 900 cases of influenza in the ship. In the wards we sent back to bunks below all men whose temperature reached 99 and kept all bunks filled with cases of higher fever.

October 4th, seven deaths during the day. The sea was rough and the ship rolled heavily. Hundreds of men were thoroughly miserable from seasickness and other hundreds who had been off the farm but a few weeks, were miserable from terror of the strange surroundings and the ravages of the epidemic. Dozens of these men applied at the wards for treatment and the inexperience of army doctors in the recognition of seasickness caused a great many needless admissions to the hospital.

Many officers and nurses were ill in their rooms, and required the constant attention of a corps of well nurses, and an army medical officer to attend them.

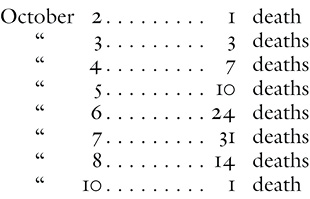

Each succeeding day of the voyage was like those preceding, a nightmare of weariness and anxiety on the part of nurses, doctors, and hospital corpsmen. No one thought of bed for himself and all hands worked day and night. On the 5th there were 10 deaths, on the 6th there were 24, and on the 7th, the day of arrival at our destination, the toll was 31. The army ambulance boat was promptly alongside, and debarkation of the sick began about noon. The sick bay was cleared first and we at once began to clean up in preparation for the wounded to be carried westbound. E-deck was then evacuated, but all the sick could not be handled before night, about 200 remaining on board.

On the 8th these were taken off by the army, but not before fourteen more deaths had occurred. Although on this day almost the entire personnel (army) had gone, the nurses remained until the last sick man was taken off.

PNEUMONIA

It is the opinion of myself and the other medical officers attached to the ship that there were fully 2,000 cases of influenza on board. How many developed pneumonia there are no means of knowing. Over 75 cases of the latter disease were admitted to the sick bay, most of them moribund. Of these, 3 improved so much that they went back to their compartments, 29 were transferred to hospital ashore, and about 40 died. As the records required to transfer patients from the army to the navy medical officers were furnished in but few cases, and as my records embrace all the dead, I had no means of knowing how many died in the sick bay and how many in the E-deck ward. Cases of pneumonia were found dying in various parts of the ship and many died in the E-deck ward a few minutes after admission. Owing to the public character of that ward, men passing would see a vacant bunk and lie down in it without applying to a medical officer at all. Records were impossible, and even identification of patients was extremely difficult because hundreds of men had blank tags tied about their necks. Many were either delirious or too ill to know their own names. Nine hundred and sixty-six patients were removed by the army hospital authorities in France.

DEATHS

Ninety-one deaths occurred among the army personnel, of whom one was an officer, as follows:

The sick officer was treated in the open air on B deck, had a special army nurse during the day, and a navy hospital corpsman at night.

HOSPITAL CORPS

I cannot speak in terms of sufficient commendation of the work of the hospital corps of this ship. Every man was called upon to exert himself to the limit of endurance during the entire round trip. No one complained, every man was on the job. Many of them worked twenty-four hours at a stretch amid conditions that can never be understood by one ashore or on a man-of-war. Some of the embalming detail, worked at their gruesome task forty-eight hours at a stretch without complaint, and at the end I had to drive them away to a bath and bed.

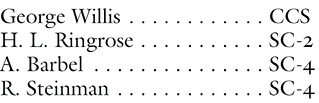

I have learned that the following named men of the Commissary Department voluntarily remained on duty with the sick on E-deck during the entire voyage.

Had we been in the midst of smallpox or plague they would doubtless have done the same. The actual danger to all hands was extremely great and all these men deserve the highest commendation for their actions.

From History of the U.S.S. Leviathan (1919)