You won’t need to buy any exotic foods to properly follow the Paleo Diet for Athletes. No matter if you live in a big city or in the country, the diet’s mainstays (fresh meats, fish, and fruits and vegetables) are almost always on hand at your local grocery store or supermarket. In Chapter 9 we laid out a comprehensive list of the foods you should limit or exclude from your diet. In this chapter, we’ll show you all the delicious, health-giving choices you have the luxury to eat. We’ll also give you some practical pointers on how to pull off a Stone Age diet in the 21st century.

When you’re hungry in the United States, getting something to eat is as easy as the nearest vending machine, fast-food restaurant, or convenience store. But you know what? You have to look long and hard to find “real” food—food that is not adulterated with sugar, salt, refined grains, and trans fats—at any of these places. The incredible overabundance and easy access to processed foods in this country make it easy to derail your plans to improve your diet—particularly when you’re famished and need food now.

One of the keys to the Paleo Diet for Athletes is fresh foods. I repeat—fresh foods! They really are so much better for you than their canned, processed, frozen, and prepackaged counterparts that there is no comparison. Canned, sugar-laced peaches don’t hold a candle to fresh peaches, either in taste or nutrition. A fatty hot dog with its added salt, sugar, and preservatives, whether it’s ground from leftover pork or beef, bears little nutritional resemblance to fresh pork loin or beef flank steak.

As an athlete, you know that small but perceptible extra efforts during training, day in and day out, season in and season out, will pay off over the long haul. Pushing that last interval to the max hurts, but by doing so regularly, you will become fitter and stronger and your performance will improve—maybe by only 1 to 2 percent, but, as we pointed out in Chapter 8, that seemingly minuscule difference can be huge when it comes to racing. This same principle holds true with the foods you eat. By methodically eating fresh, wholesome foods whenever and wherever you can, the overall trace nutrient (vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals) density of your diet will ultimately improve. And, as we have previously pointed out, there is a mountain of scientific evidence to show that your immune system functions better when properly nourished. A healthy immune system can more effectively ward off illness and help you to recover more rapidly from injuries, thereby allowing you to train at higher levels. Do yourself a favor—get fresh fruits, veggies, lean meats, and seafood into your diet whenever you can.

If you’re like most Americans, fresh fruits and veggies occupy a small drawer in your fridge, where they get wilted, soft, and brown, and they end up thrown out more often than eaten. This will change with your new diet, and here are some practical pointers to help you get more fresh produce into your meal plans.

How about organic produce—any advantages to it? Should you pay the higher price? Table 11.1 is adapted from the results of a study that compiled numerous publications comparing the nutrient content of organic versus conventionally produced plant foods. Data from this study as well as other comprehensive reviews of the literature generally conclude that, except for a slightly higher vitamin C content and possibly protein in organically produced vegetables (but not fruits), no differences exist for any other vitamins or minerals. So, if you’re contemplating buying organic produce for its greater nutritional value, it’s simply not worth it.

However, do note that the levels of nitrate in organically produced fruits and veggies are consistently lower than in conventional produce. Both the World Health Organization and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the United States have set limits for daily nitrate intake (1.6 milligrams/nitrate/kilogram body weight). Generally, both conventional and organic fruits and vegetables fall below acceptable limits. Similarly, some studies have demonstrated reduced amounts of pesticides in organic produce. Elevated environmental and dietary exposure to both nitrates and pesticides is associated with an elevated risk for developing certain cancers. If either of these issues is of concern to you, then go with organic produce.

TABLE 11.1

| NUTRIENT | % INCREASED | % REMAINED SAME | % DECREASED | NO. OF STUDIES |

| Vitamin C | 58.3 | 33.3 | 8.3 | 36 |

| Beta-carotene | 38.5 | 38.5 | 23.0 | 13 |

| Zinc | 25.0 | 56.3 | 18.7 | 16 |

| B vitamins | 12.5 | 75.0 | 12.5 | 16 |

| Calcium | 44.7 | 42.5 | 12.8 | 47 |

| Protein | 100 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Magnesium | 37.7 | 53.3 | 8.0 | 45 |

| Nitrate | 12.5 | 25.0 | 62.5 | 40 |

| Iron | 42.9 | 40.0 | 17.1 | 35 |

Potatoes maintain high glycemic loads and should be eaten only during the postexercise window, as explained in Chapter 4. If you have an autoimmune disease, you should proceed cautiously with potatoes, as they contain antinutrients that increase intestinal permeability, a significant step toward autoimmunity. Corn on the cob is a cereal grain and should therefore be excluded. Most of us have never tasted cassava roots, but they also should be avoided because of their high glycemic loads. Otherwise, virtually all fresh vegetables are perfectly acceptable: asparagus, parsnip, radish, broccoli, lettuce, mushrooms, dandelion greens, mustard greens, watercress, purslane, onions, green onions, carrots, parsley, squash of all varieties, all peppers, artichokes, tomatoes, cauliflower, cabbage, Brussels sprouts, celery, cucumbers, tomatillos, collards, Swiss chard, endive, beets, beet greens, rutabaga, kohlrabi, kale, eggplant, pumpkin, sweet potatoes, turnips, turnip greens, spinach, seaweed, yams.

As with vegetables, any fresh fruits you can get your hands on are fair game, except for people who are overweight or have one or more symptoms of metabolic syndrome (type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, or heart disease). In this case, you should follow the recommendations we have made for fruit in Chapter 9. For athletes, the only exceptions are dried fruits (such as raisins, dates, and figs), which, like potatoes, have high glycemic loads and should be limited to the postexercise window. Reach for these and other fruits anytime: apples, oranges, pears, peaches, plums, kiwifruit, pomegranates, grapes, watermelon, cantaloupe, honeydew melon, cassava melon, pineapple, guava, nectarines, apricots, strawberries, blackberries, blueberries, raspberries, avocado, carambola, cherimoya, cherries, grapefruit, lemon, lime, lychee, mango, papaya, passion fruit, persimmon, tangerine, star fruit, gooseberries, boysenberries, cranberries, rhubarb.

As you know by now, getting the fatty acid balance right is essential in replicating hunter-gatherer diets with modern foods. For our Stone Age ancestors, this problem was a no-brainer. Because their only food choices were wild plants and animals, the fatty acid balance always fell within healthful limits. By following our simple advice of eating fresh meats, seafood, and fatty fish along with healthful oils, you won’t have to give a second thought to the correct balance, either.

Always choose fresh meat, preferably free range or grass-fed. Almost all cuts of beef, pork, and poultry are good choices, and as we have outlined in Chapter 9, fattier cuts of meat can be included in your diet without increasing your risk for heart disease. Nevertheless, know that fatty meat contains less protein than leaner cuts do and hence is not as nutritionally dense as lean meat. A good financial strategy is to look for sales and buy your meat in bulk and then freeze it.

Eggs are high in protein, vitamins, and minerals and should be regularly included in your diet. Look for eggs produced by free-ranging chickens or for omega-3-enriched eggs. Virtually all recent human studies confirm that egg consumption will not increase your risk for cardiovascular disease.

Organ meats, except for marrow and brains, of commercially produced animals are quite lean. However, the liver and kidneys, which cleanse and detoxify the animal’s body, frequently contain high concentrations of environmental contaminants. We recommend eating only calves’ liver because virtually all calves slaughtered in the United States haven’t found their way to the toxic feedlot environment; all are pasture fed. Brains contain high concentrations of omega-3 fatty acids and were relished by our hunter-gatherer ancestors. However, because of the small risk of developing prion disease (mad cow disease), we do not advise eating the brains of any animal, domestic or wild. Cholesterol-lowering monounsaturated fatty acids are the dominant (about 65 percent) fatty acids in marrow and tongue, both of which are quite healthful and tasty. Beef, lamb, and pork sweetbreads are infrequently eaten, but contain healthful fatty acids.

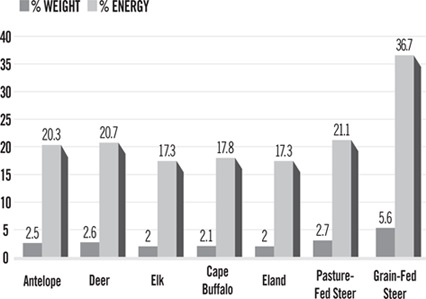

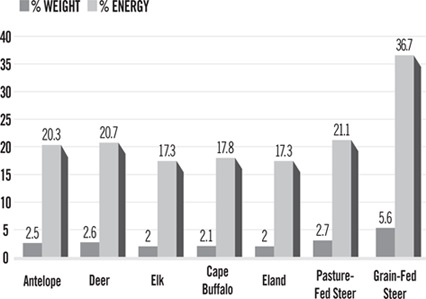

If you can find it, grass-fed (or free-ranging) meat will always be a better choice than domestic beef, pork, or poultry because it is richer in healthful omega-3 fatty acids, higher in protein (like wild game), and less likely to be tainted with hormones and pesticides. Figure 11.1 contrasts the total fat percentage among wild game, grass-fed beef, and feedlot-produced beef, while Table 11.2 compares the differences in fatty acid content.

Jo Robinson’s Web site, http://eatwild.com/, is the best and most comprehensive resource for locating farmers and ranchers in your locale that produce grass-fed meats.

You can often find organically produced beef and other meat items in health food stores or at farmers’ markets. However, organic meat and grass-fed meat are not always one and the same. Frequently, organic beef or buffalo is fattened with “organically produced” grains, yielding the same poor ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 found in feedlot animals.

TABLE 11.2

| FATTY ACID | ELK | MULE DEER | ANTELOPE |

| SAT | 610 | 989 | 895 |

| MUFA | 507 | 612 | 610 |

| PUFA | 625 | 746 | 754 |

| Omega-3 PUFA | 178 | 225 | 216 |

| Omega-6 PUFA | 448 | 524 | 536 |

| FATTY ACID | PASTURE-FED STEER | GRAIN-FED STEER |

| SAT | 910 | 1,909 |

| MUFA | 793 | 1,856 |

| PUFA | 262 | 341 |

| Omega-3 PUFA | 61 | 46 |

| Omega-6 PUFA | 138 | 243 |

SAT = total saturated fatty acids; MUFA = total monounsaturated fatty acids; PUFA = total polyunsaturated fatty acids

In the United States, the commercial sale of hunted wild game is prohibited. So, unless you are a hunter, the only way to obtain game meat is to purchase meat that has been produced on game farms or ranches—but even that, except for buffalo, is difficult to find. (One of the largest mail-order suppliers of game meat that can be found in the United States is Game Sales International.) Generally, this meat is superior to feedlot products, but it may not be as lean or as healthful as wild game. It is not an uncommon practice to feed grain to elk and buffalo to fatten them before slaughter.

Exotic meats you may want to try include kangaroo, venison, elk, alligator, reindeer, pheasant, quail, Muscovy duck, goose, wild boar, ostrich, rattlesnake, emu, turtle, African springbok antelope, New Zealand Cervena deer, squab, wild turkey, caribou, bear, buffalo, rabbit, and goat.

We no longer live in a healthy, pristine, unpolluted environment; pesticides, heavy metals, chemicals, and other toxic compounds frequently make their way into our food chain. No one knows precisely how low-level exposure to these toxins affects health over the course of a lifetime. It is prudent to try to reduce our exposure to toxic compounds whenever possible, but it is virtually impossible to eliminate exposure to environmental toxins because they now permeate even such places as the Antarctic. Fish frequently contain high concentrations of mercury and pesticides. To minimize your risk of eating contaminated fish, avoid eating freshwater fish from lakes and rivers, particularly the Great Lakes and other industrialized areas. Also avoid large, long-lived fish such as swordfish, tuna, and shark because they tend to concentrate mercury in their flesh.

Fish, seafood, and shellfish are a few of the most healthful animal foods you can consume and represent a foundation of the Paleo Diet for Athletes because they are enriched sources of the therapeutic, long-chain omega-3 fatty acids known as EPA and DHA. Fatty fish such as salmon, mackerel, sardines, and herring are particularly concentrated in both of these long-chain omega-3 fatty acids. Try to take in fish at least three times per week.

About 20 years ago, people with heart disease were advised to steer clear of shellfish, which was believed to have too much cholesterol. It’s true that shellfish is high in cholesterol—but the good news is that we don’t have to avoid it. It turns out that dietary cholesterol has a very small effect upon blood cholesterol when the food’s total saturated fat content is low. Table 11.3 shows that all shellfish are quite low in both saturated and total fat, despite having relatively high cholesterol concentrations. We encourage you to eat as much shellfish as you enjoy.

TABLE 11.3

| FOOD | CHOLESTEROL (mg) | SATURATED FAT (g) | TOTAL FAT (% total energy) |

| Shrimp | 200 | 0.4 | 15 |

| Crayfish | 114 | 0.2 | 11 |

| Lobster | 95 | 0.2 | 9 |

| Abalone | 85 | 0.2 | 7 |

| Whelk | 65 | 0.03 | 3 |

| Crab | 59 | 1 | 10 |

| Oysters | 50 | 0.5 | 26 |

| Clams | 34 | 1 | 12 |

| Scallops | 33 | 0.1 | 8 |

| Mussels | 28 | 0.4 | 23 |

Here’s a list of fish and shellfish that are important components in any modern-day variety of the Stone Age diet:

Bass

Bluefish

Cod

Drum

Eel

Flatfish

Grouper

Haddock

Halibut

Herring

Mackerel

Monkfish

Mullet

Northern pike

Orange roughy

Perch

Red snapper

Rockfish

Salmon

Scrod

Shark

Striped bass

Sunfish

Tilapia

Trout

Tuna

Turbot

Walleye

Any commercially available fish

Abalone

Calamari (squid)

Crab

Crayfish

Lobster

Mussels

Octopus

Oysters

Scallops

Shrimp

Besides being rich sources of EPA and DHA, fish and seafood represent some of our best high-protein foods. The high protein content of the Paleo Diet for Athletes is central to many of its performance benefits. Protein helps you lose weight more rapidly by raising your metabolism while concurrently curbing your appetite. Additionally, protein lowers your total blood cholesterol as it simultaneously increases the good HDL molecules that rid your body of excessive cholesterol. Protein also stabilizes blood sugar and reduces the risk of high blood pressure, stroke, heart disease, and certain cancers.

Table 11.4 provides you with all the information you need to pick out the most healthful oils. Oils you use for cooking need to be stable and more resistant to the oxidizing effects of heat, whereas those you use in your salads don’t. Saturated fatty acids (SAT) are the most stable and heat resistant, followed by monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA), then polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA). Your choice of cooking oils should be high in MUFA and relatively low in PUFA. For the price, olive oil is the best oil for cooking. All oils, regardless of their fatty-acid makeup, oxidize during cooking. Consequently, you should not fry at high or searing heats; instead, sauté at low to medium temperatures and cook for shorter periods.

The stability of oil is determined not only by its relative ratio of SAT to MUFA to PUFA but also by the type of PUFA. Omega-3 PUFA are more fragile than omega-6 PUFA because of the location and number of the double bonds in the fatty acid molecule. Consequently, flaxseed and walnut oils should not be used for cooking because of their high concentrations of total PUFA and omega-3 PUFA. However, both oils are good choices for dressing salads. Flaxseed oil is the richest vegetable source of omega-3 fatty acids. Pour it over steamed veggies or incorporate it into a marinade added to meat and seafood after cooking. Both strategies are great ways to get more omega-3 fatty acids into your diet.

Because of their high MUFA and low PUFA contents, olive, macadamia and avocado oils are good choices for cooking and add a wonderful flavor to any dish. However, macadamia and avocado oils are pricey and difficult to find. Notice that coconut oil also can be used for cooking because of its high SAT and low PUFA content. It is also a highly concentrated source of a fatty acid called lauric acid, which has therapeutic effects upon gut bacterial flora. Numerous studies of indigenous traditional Pacific Island societies prior to westernization verify that coconut consumption has no adverse effects upon cardiovascular disease.

The oils we recommend are flaxseed, walnut, avocado, macadamia, coconut, and olive. Although soybean and wheat germ oils appear on paper to have acceptable fatty acid balances, both are concentrated sources of antinutrients known as lectins. Wheat germ oil is the highest dietary source of the lectin wheat germ agglutinin (WGA), and soybean oil contains soybean agglutinin (SBA). In animal models, both of those lectins have been shown to adversely influence gastrointestinal and immune function. Similarly, peanuts are not nuts but legumes. Peanut oil, just like soybean oil, is a concentrated source of the lectin peanut agglutinin (PNA).

TABLE 11.4

| TYPE OF OIL | OMEGA-6: OMEGA-3 RATIO | % MUFA |

| Flaxseed | 0.24 | 20.2 |

| Canola | 2.00 | 58.9 |

| Walnut | 5.08 | 22.8 |

| Macadamia | 6.29 | 77.7 |

| Soybean | 7.5 | 23.3 |

| Wheat germ | 7.9 | 15.1 |

| Avocado | 13.0 | 67.9 |

| Olive | 13.1 | 22.5 |

| Rice bran | 20.9 | 39.3 |

| Oat | 21.9 | 35.1 |

| Tomato seed | 22.1 | 22.8 |

| Corn | 83.0 | 24.2 |

| Sesame | 137.2 | 39.7 |

| Cottonseed | 258 | 15.8 |

| Sunflower | 472.9 | 19.5 |

| Grape seed | 696 | 16.1 |

| Poppy seed | extremely high (no omega-3s) | 19.7 |

| Hazelnut | extremely high (no omega-3s) | 78.0 |

| Peanut | extremely high (no omega-3s) | 46.2 |

| Coconut | extremely high (no omega-3s) | 5.8 |

| Palm | extremely high (no omega-3s) | 11.4 |

| Almond | extremely high (no omega-3s) | 70.0 |

| Apricot kernel | extremely high (no omega-3s) | 60.0 |

| Safflower | extremely high (no omega-3s) | 14.4 |

| TYPE OF OIL | % PUFA | % SAT |

| Flaxseed | 66.0 | 9.4 |

| Canola | 29.6 | 7.1 |

| Walnut | 63.3 | 9.1 |

| Macadamia | 2.0 | 15.9 |

| Soybean | 57.9 | 14.4 |

| Wheat germ | 61.7 | 18.8 |

| Avocado | 13.5 | 11.6 |

| Olive | 8.4 | 13.5 |

| Rice bran | 35.0 | 19.7 |

| Oat | 40.9 | 19.6 |

| Tomato seed | 53.1 | 19.7 |

| Corn | 58.7 | 12.7 |

| Sesame | 41.7 | 14.2 |

| Cottonseed | 51.9 | 25.9 |

| Sunflower | 65.7 | 10.3 |

| Grape seed | 69.9 | 9.6 |

| Poppy seed | 62.4 | 13.5 |

| Hazelnut | 10.2 | 7.4 |

| Peanut | 32.0 | 16.9 |

| Coconut | 1.8 | 86.5 |

| Palm | 1.6 | 81.5 |

| Almond | 17.4 | 8.2 |

| Apricot kernel | 29.3 | 6.3 |

| Safflower | 74.6 | 6.2 |

MUFA=monounsaturated fatty acids; PUFA = polyunsaturated fatty acids; SAT = saturated fatty acids

If you look at peanut oil fatty acid composition in Table 11.4, you’ll see that almost 80 percent is made up of cholesterol-lowering monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats. Hence, on the surface, you might think that peanut oil would be helpful in preventing the artery-clogging process (atherosclerosis) that underlies coronary heart disease. Well, your idea is not a whole lot different from what nutritional scientists believed—that is, until they got around to actually testing peanut oil in laboratory animals. Starting in the 1960s and continuing into the 1980s, scientists found peanut oil to be unexpectedly atherogenic, causing arterial plaques to form in rabbits, rats, and primates—only a single study showed otherwise. In fact, peanut oil is so atherogenic that it continues to be routinely fed to rabbits to stimulate atherosclerosis to study the disease itself.

At first, it was not clear how a seemingly healthful oil could be so toxic in such a wide variety of animals. Then, in a series of experiments, David Kritchevsky, PhD, and colleagues at the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia showed that peanut oil lectin (PNA) was most likely responsible for the artery-clogging properties. A lectin is a fairly large protein molecule, and most nutritional scientists had assumed that digestive enzymes in the gut would degrade it into its component amino acids, so the intact lectin molecule would not be able to get into the bloodstream to do its dirty work. But they were wrong. It turned out that lectins were highly resistant to the gut’s protein-shearing enzymes. An experiment conducted by Dr. Wang and colleagues and published in the prestigious medical journal Lancet revealed that PNA gets into the bloodstream intact in as little as 1 to 4 hours after participants ate a handful of roasted, salted peanuts. Even though the concentrations of PNA in the blood were quite low, they were still at amounts known to cause atherosclerosis in animal experiments. Lectins are a lot like super-glue—it doesn’t take much. Because these proteins contain carbohydrates, they can bind to a wide variety of cells in the body, including the cells lining the arteries. And indeed, it was found that PNA did its damage to the arteries by binding to a specific sugar receptor. So, the practical point here is to stay away from both peanuts and peanut oil. There are better choices.

Since the publication of The Paleo Diet for Athletes in 2005, I have now reversed my position on canola oil and can no longer support its consumption or use. Let me explain why. Cano la oil is extracted from the seeds of the rape plant (Brassica rapa or Brassica campestris), which is a member of the broccoli, cabbage, Brussels sprouts, and kale family. Unquestionably, humans have eaten cabbage and its botanical relatives before historical times, and I still solidly support consumption of these healthy veggies. However, the concentrated oil from Brassica seeds is an entirely different proposition.

Before genetic modification by agronomists, rape plants produced a seed oil that maintained high levels (20-50 percent) of erucic acid (a monounsaturated fatty acid; lipid name: 22:1v9), which is toxic and causes tissue injury in many organs of experimental animals. In the 1970s, Canadian plant scientists developed a strain of rape plant that produced a seed with less than 2 percent erucic acid (hence the name canola oil). The erucic acid concentration of store-bought canola oil averages 0.6 percent. Nevertheless, several experiments in the 1970s demonstrated that even at low concentrations (2.0 percent and 0.88 percent), canola oil fed to rats could still cause small heart scarring that was deemed “pathological.” A succession of current rat studies of low erucic canola oil performed by Dr. Naoki Ohara and colleagues at the Hatano Research Institute in Japan reported kidney injuries, elevations in blood sodium concentrations, and irregular alterations to a hormone (aldosterone) that controls blood pressure. Other adverse effects of canola oil consumption in animals at 10 percent of calories include decreased litter sizes, behavioral changes, and liver damage. A number of current human studies of canola/rapeseed oil by Sanna Poikonen, MD, and coworkers at the University of Tampere in Finland indicated it to be a potent allergen in adults and children that causes allergic cross-reactions from other environmental allergens. Based upon these brand-new findings in both humans and animals, I favor to err on the safe side, and can no longer recommend canola oil as a part of contemporary Paleo diets.

Except for peanuts, we recommend all nuts and seeds as healthful components of the Paleo Diet for Athletes. Many people have food allergies, and nuts are one of the more common ones. Always listen to your body; if you know or suspect that nuts do not agree with you, then don’t eat them. This advice holds for all foods, including shellfish, which also frequently causes allergies. In Table 11.5, you can see the fatty acid balance for commonly available nuts. Notice that except for walnuts and macadamia nuts, all other nuts maintain high ratios of omega-6 to omega-3. The ideal ratio in your diet should be about 2:1 or slightly lower. Because nuts are so calorically dense, they can very easily derail the best-laid dietary plans. If you use nuts as staples—rather than lean meats, seafood, and fresh fruits and veggies—chances are that you will not get sufficient omega-3 fatty acids in your diet. Enjoy nuts, but use them carefully.

| NUT | OMEGA-6: OMEGA-3 RATIO |

% MUFA |

| Walnuts | 4.2 | 23.6 |

| Macadamia nuts | 6.3 | 81.6 |

| Pecans | 20.9 | 59.5 |

| Pine nuts | 31.6 | 39.7 |

| Cashews | 47.6 | 61.6 |

| Pistachios | 519. | 55.5 |

| Sesame seeds | 58.2 | 39.5 |

| Hazelnuts (filberts) | 90.9 | 78.7 |

| Pumpkin seeds | 114.4 | 32.5 |

| Brazil nuts | 377.9 | 36.2 |

| Sunflower seeds | 472.0 | 9.2 |

| Almonds | Extremely high (no omega-3s) | 66.6 |

| Coconut | Extremely high (no omega-3s) | 4.4 |

| Peanuts | Extremely high (no omega-3s) | 52.1 |

| NUT | % PUFA | % SAT |

| Walnuts | 69.7 | 6.7 |

| Macadamia nuts | 1.9 | 16.5 |

| Pecans | 31.5 | 9.0 |

| Pine nuts | 44.3 | 16.0 |

| Cashews | 17.6 | 20.8 |

| Pistachios | 31.8 | 12.7 |

| Sesame seeds | 45.9 | 14.6 |

| Hazelnuts (filberts) | 13.6 | 7.7 |

| Pumpkin seeds | 47.6 | 19.9 |

| Brazil nuts | 38.3 | 25.5 |

| Sunflower seeds | 69.0 | 11.0 |

| Almonds | 25.3 | 8.1 |

| Coconut | 1.3 | 94.3 |

| Peanuts | 33.3 | 14.6 |

MUFA = monounsaturated fatty acids; PUFA = polyunsaturated fatty acids; SAT = saturated fatty acids

The Paleo Diet for Athletes is actually not a diet at all but, rather, a lifelong pattern of eating that, besides improving athletic performance, will normalize body weight and reduce the risk for heart disease, cancer, and osteoporosis. It also plays a significant role in treating diabetes, hypertension, high blood cholesterol, inflammatory gut conditions, and certain autoimmune diseases. The positive health effects are thoroughly explained in The Revised Paleo Diet (2010, John Wiley & Sons) and in The Paleo Answer (2012, John Wiley & Sons).

In order for most people to make lifelong dietary changes, a number of behavioral techniques seem to be helpful. When giving up certain foods, most people do better psychologically when they know that they do not have to completely and forever ditch some of their favorites. The Paleo Diet for Athletes allows for what we call the 85:5 rule, which means that what you do infrequently will have little negative impact on the favorable effects of what you do most of the time.

Most people consume about 21 meals per week, plus snacks. It’s perfectly acceptable and pleasurable if two or three of those meals include any food you want, as long as fresh meats, seafood, fruits, vegetables, healthful oils, and nuts and seeds make up roughly 85 percent of the balance of your weekly calories. The Paleo Diet for Athletes allows moderate alcohol and coffee consumption or occasional chocolates, bagels, or whatever your favorite food may be. Cheating and digressions now and then are of great emotional benefit, and—so long as they make up 15 percent or less of the overall diet—will have little impact on athletic performance and health effects. This recommendation, of course, does not include the non-Paleo foods that may be eaten immediately before, during, and after some workouts, as described in Chapters 2, 3, and 4.

Many restaurants cater to vegetarians and increasingly more are offering menus for low-carb dieters. But, to date, very few offer Paleo meals. However, by ordering carefully, you can usually approximate the Paleo Diet for Athletes. The best strategy for breakfast is to order either an egg dish or some kind of fresh meat along with a bowl of fresh fruit. Poached eggs are a good bet because they will not be prepared with the wrong kinds of fat, which invariably accompany omelets and fried eggs. Also, poached or hard-boiled eggs are less likely to contain oxidized cholesterol, a by-product of fried eggs that especially promotes atherosclerosis in laboratory animals.

Lunch and dinner are usually no problem; most restaurants offer some kind of fish, seafood, or lean-meat entrée for these meals. Remember, the key is to get a big piece of animal protein as your main dish. Strive for simplicity: Forsake fancy entrées made with complicated sauces for simpler versions. To even out the acid load, order a salad (hold the croutons) and request steamed veggies instead of the compulsory bread or potatoes. For the salad dressing, vinegar and oil—particularly olive oil—are fine in a pinch. See if you can get fresh fruit for dessert.

For road trips, pack a cooler with fruits, veggies, salads, and leftover meats and seafood. A good strategy at dinnertime is to cook about two or three times as much meat or seafood as you will eat, and keep the rest for breakfast and lunch the next few days. For example, barbecue a big chunk of London broil for dinner one evening, refrigerate the leftovers, and the next day slice the beef into a mixed salad and toss with flaxseed oil and lemon juice. Voilà—an instant Paleo picnic lunch! If you don’t have a cooler, check out the deli or seafood section of a supermarket to get cooked meat or shrimp. Proceed to the produce section and grab some fresh fruit, avocados, and crisp veggies. Always keep a sharp knife and some utensils in your car so that you don’t have to deal with cutting up meat with a plastic knife.