PART 1

Liquid Aids

Techniques involving liquids seem the obvious place to start this book, since watercolor is itself a liquid medium. Moving and flowing, splashing or spattering, dripped, drizzled, or daubed, liquid aids complement watercolor in a special and most natural way.

This section covers the various ways to incorporate liquid aids into your paintings, exploring their effects as you go along. Some of these you may already have tried, some are old standbys, while others may be new to you—the new materials and supplies constantly being introduced in the marketplace keep us on our toes and give us new avenues to explore.

Use these tricks and techniques judiciously. Don’t let them take over your work, but remember to have fun! Keep an open mind as you give the ideas here a try, and perhaps they’ll spark something entirely new and different.

PAINT CHARACTERISTICS

Tube vs. Pan Colors

Some artists feel that tube colors are somehow better than artist-grade pan colors, but usually they are of comparable quality. It’s more a matter of how you work.

At times, manufacturers will tell you their paints won’t work as well if you let them dry on the palette and re-wet them. I have not found that to be true in practice, but you should make your own decision.

The main advantage to using tube paint fresh from the tube, for some artists, is that they feel more able to mix a large wash quickly. If I pre-wet my pan paints, however, I can mix a wash very easily, and often more smoothly than with freshly-squeezed tube paint.

Artist’s-Quality vs. Student-Grade Paints

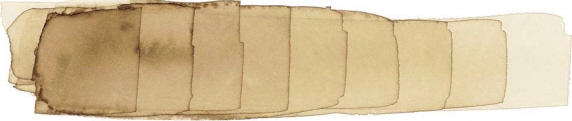

The quality of your paints is just as important as the transparency, opacity, brilliance, staining properties, or anything else, and perhaps even more so. Cheap, student-grade paints may fade, be difficult to lift or mix, flake, change color, or otherwise disappoint you. Other student-grade paints (bottom row, above) may be perfectly satisfactory—you should experiment, but to save money, I suggest starting with a few artist-grade paints (top row, above) in colors you prefer.

Pan Color

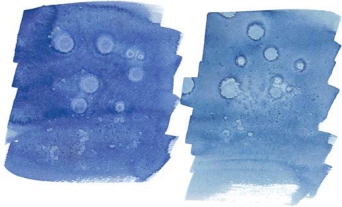

I moistened the pan colors on the left and used them immediately. For the colors on the right, I pre-wet the pans half a minute before starting to paint. What a difference in intensity and saturation!

Tube Color

Here I let my tube colors dry on the palette. Then, for colors on the left, I moistened the color and applied it immediately. I pre-wet the colors on the right before applying them. As you can see, in both pan and tube colors, pre-wetting a moment or two before painting produces a much richer, more saturated color.

PAINT CHARACTERISTICS

Know Your Paints

Perhaps the first order of business is getting to know your paints; this will allow you to work some very subtle and effective tricks and techniques. Learn the properties and possibilities inherent in your paints, and you’ll have more confidence with any new technique you may want to try.

My advice is to keep it simple, at least to begin with. Choose a few basic paints and learn what they will do, alone and in combination. A warm and cool of each primary color (the primaries are red, yellow and blue, from which all other colors can be mixed) will see you through nearly any situation. With the judicious addition of a few of what I consider convenience colors (a couple of earth colors, and perhaps Payne’s Gray, Indanthrene Blue or Indigo) and a green or two, you’ll be able to paint anything.

These are four of the “convenience colors” I often include on my palette: (top to bottom) Burnt Umber, Payne’s Gray, Yellow Ochre and Burnt Sienna.

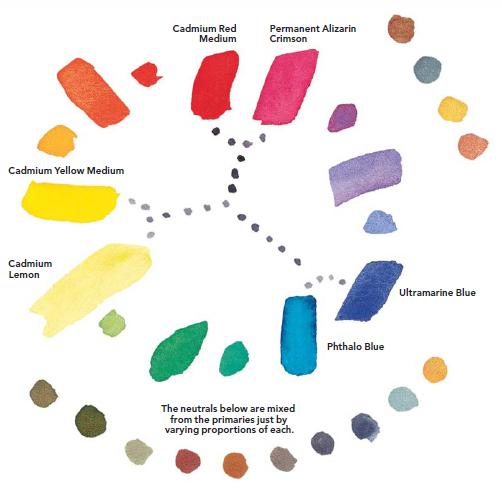

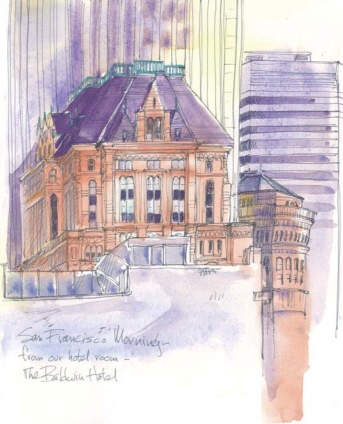

Make a Color Wheel With Your Paints

This is a simple, basic color wheel palette that’s plenty to start with or stay with! You can always add new colors, one by one, as you discover effects you want to try. (If you buy sets of paint, of course, the colors are already chosen for you. I prefer to buy tube paints or individual moist pans and get exactly what I need.)

Here are the main warm and cool primaries on my palette with the secondary colors mixed from those basics shown in between.

Warm vs. Cool Colors

By warms and cools, I mean those versions of a color that lean toward one temperature or the other on the color wheel. For instance, a Cadmium Red Medium or similar hue leans more toward orange (warmer), while Quinacridone Red and Permanent Alizarin Crimson lean toward purple (cooler).

Being aware of temperature makes color mixing much more versatile, as well as simpler. Colors can be more intense, cleaner, or fresher when warms are mixed with warms, and less intense, more subtle, or grayed when warms and cools are used together. Get to know the possibilities.

For More on Paint Properties...

For more detailed information on paints and their properties, check Bruce MacEvoy’s comprehensive Handprint site at www.handprint.com.

PAINT CHARACTERISTICS

Compare Paint Brands

Learn about all your chosen paints. Understanding their unique properties will help you make the best possible choices for you. Even the brand can make a difference. At first, it may be best to settle on one manufacturer and stick to it unless you can remember which company makes what paint or color you prefer. For instance, three samples of paint with the same name from different manufacturers can vary substantially, even though all have the same pigment.

Take time to become fully acquainted with each new tube you buy—put it through its paces, and review your old colors while you’re at it. Make color charts to explore the range of tints (light) and shades (darker) each paint is capable of, glaze one color over another, drop some paint onto wet paper to see how it diffuses, and try lifting color from the paper with a damp brush and clean water. If you’ve never played with your paints before, now is the time! And it is play—you’ll discover some delightful properties; fresh, new effects; and a world of possibilities.

Yellow Ochre:

Winsor & Newton, Schmincke Horadam

Burnt Umber:

Winsor & Newton, Daniel Smith

Ultramarine Blue:

Daniel Smith, M. Graham, Schmincke Horadam

Cadmium Orange:

Winsor & Newton, Schmincke Horadam

Burnt Sienna:

Winsor & Newton, Schmincke Horadam, Kremer Pigments

Phthalo Blue:

Winsor & Newton, Daniel Smith, Schmincke Horadam

Cadmium Red:

Winsor & Newton, Schmincke Horadam

Raw Sienna:

Kremer Pigments, Maimeri Blu

Manganese Blue Hue:

Winsor & Newton, Holbein

Brand Comparisons

This chart gives you an idea of the variety possible from brand to brand. If you have several brands on hand to explore, make a similar chart to familiarize yourself with their differences. I was astounded particularly by the differences between the various brands of siennas, umbers and blues I owned. Such diversity is not too surprising, though, when you consider that the various companies may choose different ingredients or combinations of ingredients to make their paints (or may get ingredients from different sources or locales that can affect color and handling properties). For example, “Sap Green” may be made from seven or more different pigments, depending on the manufacturer (though normally each manufacturer chooses two or three from these possibilities), so you see that the color name is sometimes not enough to go on.

PAINT CHARACTERISTICS

The Importance of Pigments

Pigments (and dyes, which appear in some liquid watercolors) are what make up your paints, whether they be watercolors, acrylics or oils. Pigments are finely ground raw materials which can be made into usable paints with the addition of a binder or vehicle like gum arabic, honey or sugar, plasticisers, humectants and other ingredients. Pigments don’t dissolve in water; they are suspended in the additives that help them disperse in liquid and adhere to your paper. (Think of silt particles suspended in a muddy river to picture this suspension.)

Pigments are organic or inorganic, and may be classified as natural or synthetic. Both types are useful to the artist and essential to some of us. When you know what makes up the paint you choose, you have a better idea of how that paint will react and how best to use it in your paintings.

Grinding Pigment Into Paint

Daniel Smith’s Natural Sleeping Beauty Turquoise was used here. Most of us are familiar with this gemstone; it’s recognizable in all its forms and makes a lovely color when ground into paint.

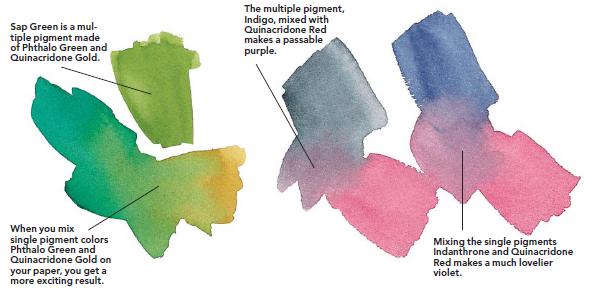

The Differences Between Single-and Multiple-Pigment Paints

Some artists prefer to stick to single-pigment paints—those with only one code. Paints made by mixing pigments will have multiple codes. It doesn’t bother me if two (or more) pigments have gone into the tube, since I’m going to be mixing them anyway. However, sticking to single-pigment paints will allow you to choose more consistently from brand to brand, and may help you achieve cleaner mixtures.

Different Paint Names, Same Pigments

Pigment designations are found on most tubes of paint and on manufacturers’ charts. Look for the name and identifying pigment code (e.g. “Pigment: Cobalt Blue, PB28” which stands for Pigment Blue 28). Even if paint names vary by brand, all brands use the same code for specific pigments.

PAINT CHARACTERISTICS

Earth Colors

Earth colors refer to the range of browns, ochres, siennas and umbers (as well as a few others) that are made from ground earth pigments—mineral-rich soil, clay and so on. They are usually inorganic (Van Dyke Brown, a fugitive color that’s liable to fade, is an exception) and not so saturated or intense; they have a low tinting strength. (Think dirt, but highly refined dirt!)

Of course, there are many more possibilities than are shown here—that’s left for you to explore. Work with these paints to discover which paints diffuse most on damp paper, which “crawl,” which stay pretty much where you put them and which settle smoothly, so you can decide how to use the various properties to create effects all your own.

Practice Painting Wet-Into-Wet and Direct

Here I tested how earth colors diffuse on wet paper. When that dried, I made two strokes of pure color directly on top. Painting with earth colors produces diverse effects although a bit unsaturated.

Test the Staining and Opacity

The colors I’ve used here are (top to bottom) Raw Sienna, Burnt Sienna, Yellow Ochre, Burnt Umber and Venetian Red.

PAINT CHARACTERISTICS

Carbon Colors

The carbon compounds are organic and usually transparent and staining; use with care and you’ll enjoy their unique properties. They include Permanent Alizarin Crimson, Phthalo Blue, Phthalo Green and the quinac-ridones. Artists often erroneously refer to carbon colors as dye colors because of their tendency to stain, though technically they are not true dyes.

Test the Transparency

Carbon colors are quite transparent as you can see when they are painted over a strip of waterproof ink. I tried lifting the color on the right side; I was surprised at how well the Phthalo Green lifted!

Gorgeous Glazes

Because carbon colors are so transparent, you can glaze one over another and still see the color below. To prevent mixing, it’s best to let the first layer dry thoroughly before adding the next color. Use these colors where you want strong, transparent color, or thin them for very subtle color alterations, such as a shadow on a flower.

PAINT CHARACTERISTICS

Essential Mineral Colors

The mineral colors include the cadmiums, Ultramarine Blue and Cobalt Blue. These are essential colors on many artists’ palettes. These traditional pigments are very useful when you want a good, strong color. You can also use them to glaze over other colors, but while they are brilliantly colored, they can be rather opaque. Experiment with these old favorites to learn their capabilities and what they can do for you.

Test the Transparency

Mineral colors are quite opaque as you can see when they are painted over a strip of waterproof ink.

Cadmium Orange Adds Brilliance to a Winter Scene

Cadmium Orange really captures the slanting light of this winter sunset. It is a somewhat opaque, heavy color, and when used wet and dropped into a damp wash, it pushes that wash back to create a nice edge. You can see this most clearly in the bottom edge of the tree at the far right.

Practice Painting Wet-Into-Wet and Direct

Here I tested how the mineral colors will diffuse on wet paper. When that dried, I stroked on a swatch of direct color. Then, when that dried, I lifted color with clear water.

PAINT CHARACTERISTICS

Novelty Mineral Colors

There are a number of new mineral colors on the market—Daniel Smith’s PrimaTek line, Joe Miller’s Signature Series, and Natural Pigments all offer new paint possibilities for paints made from minerals. Some are older, historical pigments that are given a new look, while others are completely new. In many cases, the pigments are ground from semi-precious gemstones, and they can give your art a new dimension. You owe it to yourself to experiment with at least a few of these colors.

Beautiful Granulation Qualities

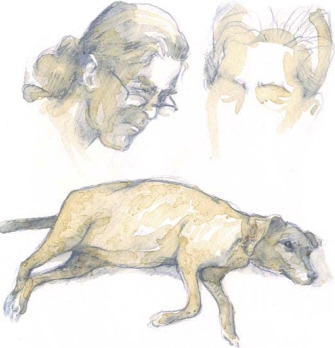

This little sketch shows some of the possibilities of the 8-pan Natural Pigments set. This set is modeled after the eighteenth-century artist John Robert Cozen’s palette. Here I mostly used the rich red browns, browns and blacks, which granulate nicely to suggest foliage.

Purpurite Genuine

Rhodonite Genuine

Natural Sleeping Beauty Turquoise Genuine

Minnesota Pipestone

Natural Amazonite Genuine

Serpentine Genuine

Zoisite

Tiger’s Eye Genuine

Bright Minerals

Some mineral paints are quite subdued in color, but they don’t have to be! Those made from semiprecious stones can be quite colorful. Here are swatches from the Daniel Smith paint line.

Try Painting With the New Bright Minerals

In this painting I used some of the brighter of the new mineral colors in several different ways—applying paint wet-into-wet, as glazes and as direct painting.

PAINT CHARACTERISTICS

Explore Your Paints

Again, getting to know your paints and the pigments that go into them help you get the effects you want. You can make them do amazing things, if you know which ones to reach for on your palette! From bold and bright to the subtlest of neutrals, all these are at your fingertips with a bit of experimentation and practice.

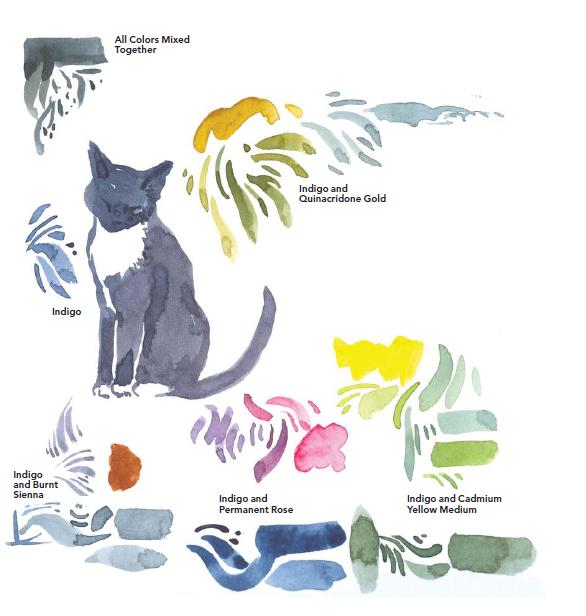

Test Any New Colors You Add to Your Palette

Here I was trying out a new tube of Indigo in my journal, mixing it with other colors on my palette. This kind of “play” is fun and instructive, and suggests fresh alternatives to your usual tried-and-true color mixes.

Test Your Pigments’ Permanence

If you’re just playing or working in a journal that will normally be closed, lightfastness (the permanence of the colors you choose) isn’t such a big issue. If you’re doing paintings intended to be framed and hung where they will be exposed to light, however, you should definitely keep permanence in mind.

Student-grade paints have a tendency to fade even if not exposed to direct sun. Even some artist-grade paints have this same issue.

To test pigments on your own, make a strongly saturated stripe of each of your colors and label them with the name (and brand, if you like), then cover half with a piece of thick, opaque or black paper. Put this setup in a sunny window for three to six months, then check back to see which colors have faded.

PAINT CHARACTERISTICS

Transparency and Opacity

Sometimes it is important to know the transparency or opacity of colors. After all, when you just want to lay in a transparent glaze to alter mood or color, you’d be disappointed to end up with a foggy veil instead, and when you want to cover something with a strong opaque or add that subtle, smoky look, it’s frustrating to have your overglaze disappear as if it had never been. The cadmiums are quite opaque and can be used as bright “jewels,” touches of pure color, even over a fairly dark preliminary wash. Make a handy chart of all your colors to help you see the transparency/opacity of all your colors for future use.

The Perfect Subject for Bold Opaques

This quick sketch of a friend’s Schnauzer shows the bold granulating and opaque qualities that make Kremer paints so interesting.

Make a Color Chart for Transparency and Opacity

Anytime you try out new colors, it’s always a good idea to test the transparency and opacity to see how they will react when you go to paint with them. To do this, lay down a strip or two of black India ink and let it dry thoroughly. Then, simply paint a strip of each of your pigments over these black bars. Some colors will almost cover the black (these are more oaque), and some will seem to disappear (these are more transparent).

On the left, I’ve tested the Daniel Smith, Winsor & Newton and Schminke colors normally on my palette. On the right, I’ve tested a relative newcomer to the field, Kremer Pigments. Kremer colors are richly pigmented, somewhat grainy and more opaque than some of the other brands, but great fun to experiment with.

PAINT CHARACTERISTICS

Staining and Sedimenting Paints

Staining and sedimenting are two interesting properties you may want to explore. Some colors, by the nature of their pigments or the ingredients used, will sink into the paper and be harder to remove; some have larger pigment grains that settle into the grain of the paper to make interesting texture (see the Schnauzer sketch).

A manufacturer’s paint chart will tell you which paints stain and which granulate or sediment. Combining these two types of paint in a single painting can produce interesting effects.

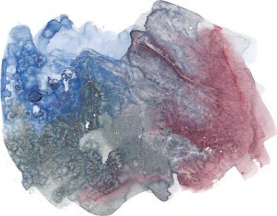

Mix Staining and Sedimenting Colors for Exciting Effects

Here I applied Ultramarine Blue at upper left, Zoisite in the center, and Manganese Blue Hue at upper right; all dropped into a wash of Permanent Alizarin Crimson. Often you will get a kind of halo as the heavier sedimenting color settles into the grain of your paper and the staining color diffuses. I’ve accentuated the effect here by tipping my paper back and forth and allowing the Permanent Alizarin Crimson to flow, to help you better see the effects. This technique could be useful in any number of ways, to depict a foggy morning or a soft sunset, or to suggest shadows on flesh.

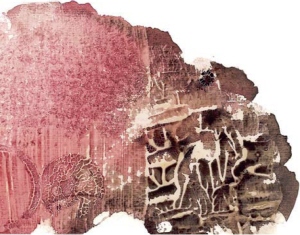

Apply Sedimentary Paint Over Ink

An ink underdrawing can give you a wonderful framework on which to float sedimenting colors. Allow them to flow and settle in interesting ways. Tipping your paper back and forth while the wash is wet will encourage maximum settling. This technique works best if you are using a paper with some texture, such as cold press or rough. Here I’ve used Cobalt Blue and Venetian Red in various mixtures.

MIXING COLORS

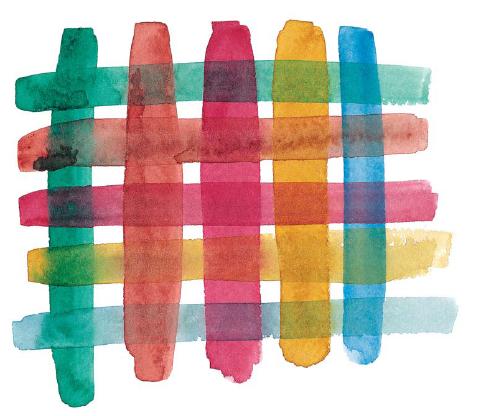

Mixing on the Paper vs. Mixing on Your Palette

It makes a huge difference whether you mix your chosen pigments on the palette or on the paper; the contrast can be dramatic. If you are after a smooth, homogenized blending for flat or especially subtle effects, mix on your palette. For exciting, varied effects, try mixing directly on your paper.

Mixing on the Paper for a Foliage Effect

Here I drew the spiderweb with liquid mask, then dropped in blues and yellows and allowed them to mix mostly on the paper. I sprayed some with clear water and spattered with more of the colors used for a soft, varied effect that suggests distant foliage.

Paper vs. Palette

Mixing Sap Green, Yellow Ochre and Cobalt Violet on the palette (top) produces a uniform tone, neutral in color and a bit muddy.

Mixing the same colors on paper instead of the palette (bottom) produces a much more varied effect. Of course, you can mix somewhat more thoroughly than I have done here—this is an extreme example. Normally, I just introduce little “jewels” of pure color here and there in an area of the painting.

MIXING COLORS

Mixing Grays and Neutrals

It’s not necessary to buy gray in tube form, unless you just want to. Mixing grays and neutrals can give you some wonderful color choices. I like to mix my grays with earth colors or use a “palette gray,” the gray that results from mixing all the colors left on your palette. Try both approaches as each has its use.

Full-Palette Grays

Grays mixed from whatever colors are on your palette at the time can be very luminous, especially if you’ve used no sedimenting colors. They can be warmed or cooled according to the puddle of paint that you draw your brush through. Here Phthalo Blue, Ultramarine Blue, Permanent Alizarin Crimson, Cadmium Orange, Sap Green and Raw Sienna were variously mixed to produce the grays you see. These lovely grays work well with people, florals, and interiors, or any place you want a subtle, luminous, or light-filled gray.

Burnt Umber and Ultramarine Blue

Burnt Sienna and Ultramarine Blue

Burnt Sienna and Manganese Blue Hue

Raw Sienna and Cobalt Blue

Earth Grays

The sedimenting earth and mineral colors produce atmospheric, grainy grays, wonderful for painting the details of nature. In this sample, I’ve mixed my warms and cools to offer some suggestions. Some are rich and dark, others lighter in value, like the mix of Raw Sienna and Cobalt Blue here. Notice how the colors separate and make their own nice, grainy textures as the heavier pigment particles settle into the texture of the paper.

MIXING COLORS

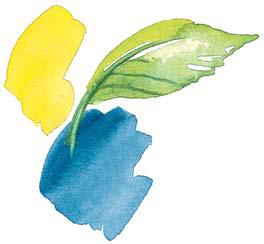

Mixing Greens

Many artists have an aversion to certain hues—colors they just can’t tolerate. For a long time, I disliked green. I used to complain about painting in the summer because of all the unvarying, everlasting greens. So I tried mixing greens from all the blues and yellows on my palette (oranges and warm browns can also act as yellows) and discovered my favorite deep rich green, which is made from Phthalo Blue and Burnt Sienna.

Olive Hue

Fresh Spring Green

Think About the Color Wheel When Mixing Greens

Be aware of the color wheel you explored, when going for the greens. Phthalo Blue and Cadmium Yellow Light or Cadmium Lemon will produce a fresh spring green, while Cadmium Yellow Medium and Ultramarine Blue produce a more olive hue.

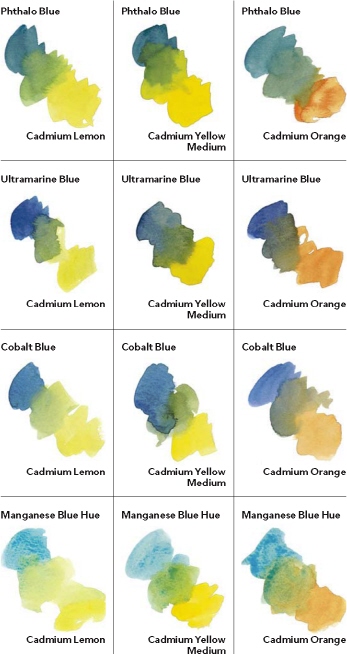

Mix a Range of Greens Using Your Palette of Colors

Try mixing all the blues you own with all the yellows and see what a wonderful variety you achieve. These greens are made the old-fashioned way, mixing yellows and blues. Phthalo Blue, Ultramarine Blue, Cobalt Blue and Manganese Blue Hue are my blues; Cadmium Lemon, Cadmium Yellow Medium and Cadmium Orange are my yellows. There are any number of other choices, of course. Try Indian Yellow, Transparent Yellow, New Gamboge, Yellow Ochre, Raw Sienna, Naples Yellow or any other yellow (or blue) that you normally use. The point is to get acquainted with the colors you have and what they will do.

Experiment Further

Try altering your tube greens with browns, blues, yellows and reds. You may find new and exciting greens that you look forward to using whenever possible.

MIXING COLORS

Don’t Be Afraid of Mixing Darks

You can get wonderful rich darks with watercolor—don’t be afraid to mix up bold washes. You can make lively, velvety blacks, wonderful shadow colors and rich pine-greens, all without resorting to tube blacks.

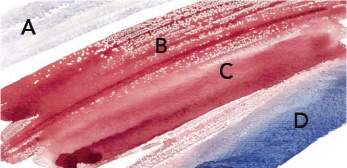

Practice Mixing Darks

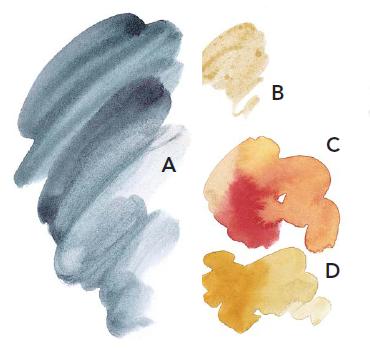

Here are some possibilities for mixing great, bold darks. Try combinations of your own, and be sure to keep notes!

A Phthalo Blue + Burnt Sienna

B Quinacridone Burnt Scarlet + Ultramarine Blue

C Burnt Umber + Ultramarine Blue

D Phthalo Green + Permanent Alizarin Crimson

E Indigo + Burnt Umber

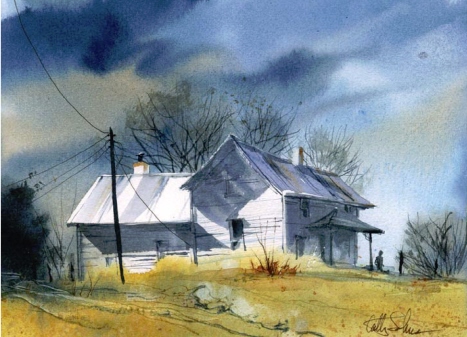

Use Darks to Portray Stormy Skies

Here I used Indigo, Payne’s Gray and Burnt Sienna in the sky, and a rich, dark mix of Phthalo Blue and Burnt Sienna on the left for the cedar tree.

Mixing Large, Dark Washes

If you need to mix up a large amount of color, use a small cup rather than your palette. Then test the color on scrap paper to make sure it is as dark as you want.

WORKING WITH OPAQUES

Gouache and Opaque White Watercolor

Opaque white or gouache is handy stuff and has been used by artists for generations. However, these days, the use of opaque white with transparent watercolor is considered by some to be in a class with spitting on the flag or taking your martini stirred rather than shaken; I admit to a bit of that prejudice myself. But when I give in to it, I remind myself that what I’m trying to do is produce a painting, a work of art, not necessarily a pure transparent watercolor.

Retouch White and Ink

This sample shows white ink and retouch white (a bleed-proof white paint originally used by graphic designers to correct mistakes on pen and ink drawings) on top of a dried wash of Permanent Rose.

The bottom two lines are retouch white. The retouch white is a bit more opaque than the ink, and fed more smoothly from the pen nib I was using to apply it. It needs only to be thinned a little before charging your pen nib.

The rest of the whites were done with white ink, which has varied transparency, depending on how much water you mix in. In the large, top wash of ink, I thinned my mixture by about half with water, then spattered the lower edge with clear water.

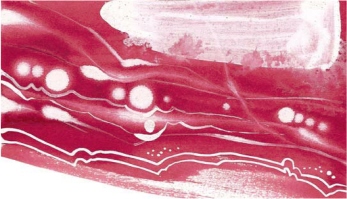

Wet-Into-Wet Opaque White Paint

Opaque white reacts interestingly with water. Try it in a wet wash to produce a soft “vapor trails” effect as seen here. Notice that I’ve also used a bit of wet-into-wet spatter; it reminds me of altocumulus clouds—high and patchy.

Opaque White Makes a Great Highlight

A tiny touch of opaque white ink can give a wonderful sparkle of life to an animal’s eye. Here my cat Oliver’s astounding multicolor mosaic eyes really lit up when I added the opaque white.

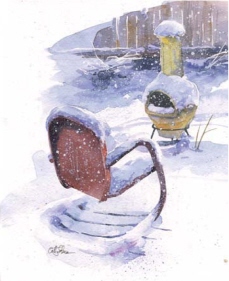

Spattering With White Gouache

There’s no better way to suggest falling snow than with a bit of opaque spatter when your painting is all but finished. Thin down opaque white to a light-cream consistency, but not so thin that it is no longer opaque. Spatter on from a stiff bristle brush or an old toothbrush. Try to vary the size of the droplets for interest, and keep them somewhat clumped to give the feeling of snow flurries.

WORKING WITH OPAQUES

Working With Opaque White and Color

Using your favorite watercolors to tint opaque white is a handy way to get a strong opaque. This type of treatment can give your work new layers and dimension. Painting with opaque color also allows you the opportunity to work on new surfaces—like tinted paper—which gives a whole new effect to your paintings. (Be aware that opaque whites range from warm to cool, and translucent to opaque. Zinc White is a warm, translucent white, whereas Titanium is a cool, more opaque white.)

Multi-Colored Opaque Spatter

The handiest and least noticeable use of opaque is in spatter. Here I’ve suggested a field of wildflowers by spattering judiciously with white, pink and yellow, made by mixing opaque white with my palette watercolors.

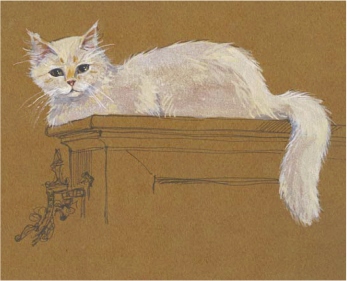

Gouache on Toned Paper

Gouache pops on toned paper. To paint my light-colored cat on this brown background, I combined opaque gouache paints with opaque white in the lightest areas. A tiny dot of opaque white creates the perfect highlight for the cat’s eye. (Be aware that you may need to restate your lights with additional or stronger washes, as opaque colors dry differently than you may expect.)

Gouache Alternatives

If you don’t want to invest in tubes of gouache paint to begin with (they are rather expensive), stick with a tube of opaque white or use a product like retouch white or correction white. Many artists prefer to use white acrylic for spatter, but remember, it is permanent when dry.

Using Gouache to Paint a Moody Portrait

DEMONSTRATION

You can get some wonderfully subtle and sophisticated effects using gouache on paper you tone yourself. I’ll show you in this painting of my youngest godchild, Nora.

MATERIALS LIST

Pigments

Acrylics: Burnt Sienna,

Ultramarine Blue

Gouache: Chinese White

Brushes

1-inch (25mm) flat

nos. 6 and 8 rounds

Surface

140-lb. (300gsm) cold-pressed

watercolor paper

Other

White colored pencil

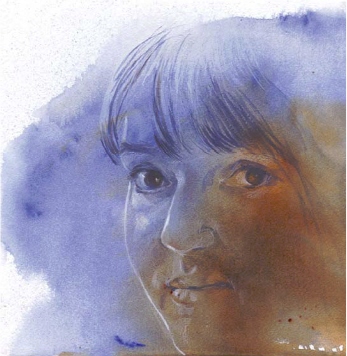

1 Tone the Paper

Use Burnt Sienna and Ultramarine Blue acrylic, thinned to a watercolor consistency, to make a loose, abstract background with your flat brush. This background wash will serve as the middle values for the painting.

Sketch in the simplest of beginnings with a white colored pencil as guidelines for your portrait.

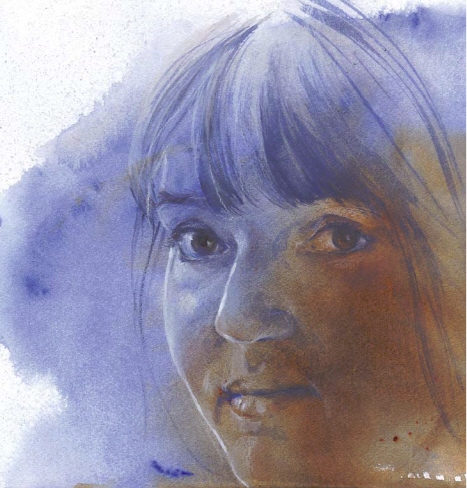

2 Develop the Subject

Add more details to your subject with Chinese White gouache. Then mix Chinese White with Ultramarine Blue and Burnt Sienna to create a dark, opaque color for the eyes. A no. 6 round offers control for details.

3 Develop Form

Work back and forth with lighter and darker versions of the acrylic/gouache mix from step 2, adjusting the likeness and the light across her face. Allow the background wash to continue to provide middle values.

4 Make Final Adjustments

Adjust some areas for greater accuracy, washing back and lifting away some of the gouache if needed to model the cheek and mouth. Add final details such as the definition of shapes on the lips, and refine the eyes. Then add more fine, silky strands of hair with your no. 8 round, spreading the brush hairs and painting with a dry-brush effect.

Old Master Tricks

The Old Masters mixed Chinese White gouache with each color on their palette for a soft, moody look. Just be sure not to apply these mixes too thickly as they can crack when dry.

SPECIALTY PAINTS

Have Fun With Specialty Paints

There are lots of new (and not-so-new) specialty paints out on the market—experiment! Some of these are considered to be novelty paints; you may not want to use them in a serious piece you plan to enter in a show.

Duochrome colors combine two color notes. Viewed from one angle they appear as one color, while from another angle, they look like a different color entirely.

Interference paints are similar, though they usually appear quite pale on the palette. Where you stand when you look at them makes a difference in their appearance. These pigments are often created with a fine, metal-oxide-coated mica powder with a variety of grain sizes that account for the color change (they are both reflective and refractive, which means they can bend light). Originally, the shimmer of interference paints came from the scales and bladders of whitefish, like herring.

A more familiar standby with a much longer history, iridescent paints reflect light directly and don’t depend on where the viewer stands. This classification includes golds, silvers, coppers and pearls.

Try all three specialty paints on one subject!

Try Mixing Specialty Colors With Your Favorite Colors

Specialty paints can be used straight from the tube or mixed with other paints to create subtly shimmering washes.

A Pearlescent mixed with Permanent Alizarin Crimson and Phthalo Blue

B Iridescent Gold

C Iridescent Gold mixed with Hansa Yellow and Cadmium Red

D Iridescent Gold mixed with Quinacridone Gold

Use Specialty Paints on a Dark Surface for the Best Pop!

Duochrome, interference and iridescent paints work best on a dark surface where they can add shine to your work.

INKS

Ink and Watercolor

The practice of doing an ink drawing and applying color with washes of watercolor has been around for hundreds of years and is enjoying a renaissance today.

There are many ways to apply ink, including dip pens, brush pens and fiber-tipped pens. Working with ink and watercolor together is interesting no matter how you choose to do it!

Apply Ink Wet-In-Wet

When applying ink over wet watercolor, the ink blooms and spreads and goes all over the place. It can be more or less controllable, depending on how wet your preliminary wash is and on the brand or kind of ink you buy.

Apply a rich wash of watercolor, and try a few ink application techniques. Here I dragged the ink bottle stopper over the wet wash, drew into it with a pen nib and dropped ink off the end of a brush.

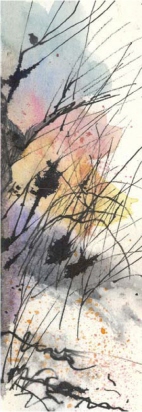

Wet-into-wet also allows for loose effects that work well in landscapes. It is great for grasses and reeds.

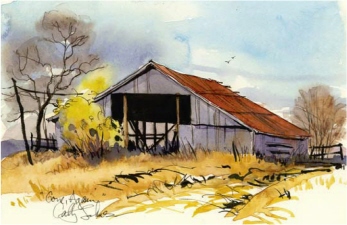

Apply Watercolor Over a Dry Ink Sketch

I sketched this scene with a Pentel Pocket-brush pen (which has a nice variable brush tip) and waterproof India ink, and let it dry. Then I washed watercolors in loosely. Rembrandt often used this technique with wonderful results. Instead of watercolor, you can complete your scene with washes of ink diluted with water for a monochrome effect.

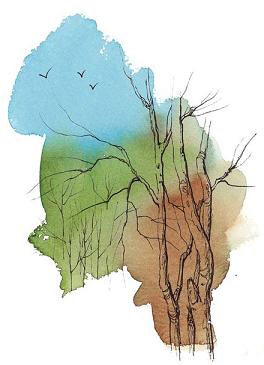

Apply Ink Over a Dry Watercolor Background

Let a loose wet-into-wet wash suggest a subject, then add ink. Here, a fresh mix of blue, green and brown created a moody background. Once it dried, I added the subject with ink.

INKS

Colored Inks

There are many wonderful colored inks available with their own very special “special effects.” Sepia is my favorite—I like it for its atmospheric moodiness and its subtlety, but you may like blue, orange or purple instead.

Try them all!

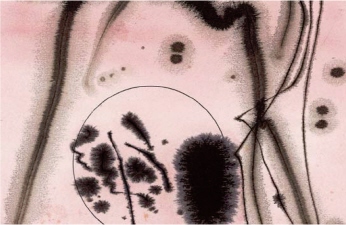

Sepia Ink on a Wet Wash

Here I’ve applied Sepia ink with a nib onto two wet pigment types, staining Permanent Alizarin Crimson and sedimentary Ultramarine Blue. The ink is a bit more active in the staining wash, but it displaces the sedimentary pigment, leaving a lighter, haloed line. I was very generous with the ink on the dark line at the right. It was quite juicy; you can see how it spread like a centipede! The pressure of the nib made a fine line down the center of each squiggle—this effect could be avoided by painting it on with a brush.

While these samples look abstract, this technique can be used in a number of ways. Use it to suggest a woodsy background, create patterns in ice or create flowers; it’s very versatile.

Bright Colors on a Wet Wash

Here I’ve worked a few of the available inks into a wet, pale Phthalo Blue wash. Where the pen had a lot of ink in it, you see wild spreading of color. The more controlled lines result from less ink in the pen or a faster stroke (applying ink from a pen slowly will allow more of it to leave the pen).

You will also get different effects according to what your base wash is, so you may want to try this out on a small sample sheet before using it in a painting.

Use Two Colors of Ink in One Painting

The brown ink on the peppers and onion keeps them inside the darker black ink basket.

EFFECTS WITH WATER

Clear Water

The simplest liquid aid of all is plain old H20 (clear water). It’s as basic to the watercolorist as paint. I often try to keep two containers of water, one to clean my brush and one for mixing fresh pigment washes, this one staying clean and unsullied, instantly available for all kinds of special effects.

A Sprayer for Every Occasion

I found this little sprayer in the travel section of my local discount store. You may also find one at art or beauty supply stores in a variety of sizes, but I couldn’t beat the price of this one. It can also act as my water supply when painting on the spot.

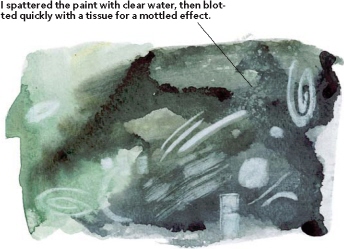

Spattering and Blotting Water

Here I’ve suggested a rock form with Burnt Umber, Burnt Sienna and Ultramarine Blue, mixed primarily on the paper rather than on my palette. As the basic wash began to lose its shine, I spattered on clear water from a stencil brush (any small, stiff brush would work as well) and also hit it, here and there, with a fine spray from a pump bottle of fresh water. I blotted occasionally to heighten the effect. I scraped in a few lines and spattered on a bit of Burnt Sienna for further texture.

Use Blooms and Backruns to Your Advantage

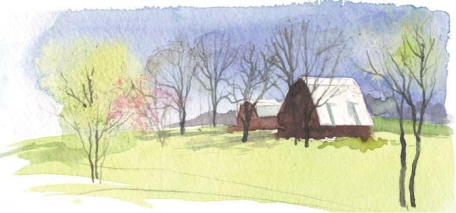

Of course, you can also make juicy washes in a lighter value and let them make deliberate backruns, as well. That’s what I did here to suggest the early spring trees against the darker blue sky. While the sky was still damp, I dropped in “blooms” of a pale green wash. That wetter color pushed the blue pigment back and made soft-colored spring trees.

Dripped and Spattered Water on a Wet Wash

In this sample I dripped and spattered clean water into a rich, wet wash of Ultramarine Blue, causing large “explosions.” Notice how the pigment crawls at the edge of each drop. (This is called a “bloom,” and usually happens in a painting by accident. But, why not do it on purpose? It can be a very effective trick.)

I spattered smaller droplets into the wash as it began to lose its shine.

This looks a bit galactic to me. Maybe it’s that deep blue “sky” wash.

EFFECTS WITH WATER

Clear Water continued

Let the Weather Work for You

Sometimes Mother Nature provides the H2O. In this case, I was painting on the spot when a drizzle started, landing in the damp sky wash. The effect worked so well, I decided to let it be. I could not have done it better myself!

Suggest Trees With Water-Sprayed Paint

This is a very useful technique, whether on a forest or a single tree. Here, I laid down Phthalo Blue and Burnt Sienna in a rich splotch of color, which I then hit judiciously with a sprayer. I suggested the limbs and twigs by pulling paint from the wet wash down into the dryer part of the paper using the tip of a sharp pencil.

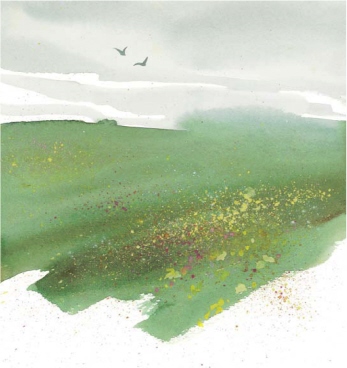

Suggest an Entire Landscape With Water-Sprayed Paint

Here I suggested landforms with juicy washes of Quinacridone Burnt Scarlet and Indigo. While they were still wet, I hit selected areas with water from a small sprayer. It made the pigment follow the shape of the spray to create lovely foliage-like effects. A flock of crows feeding in the wintry field completes the scene.

RESISTS

Liquid Masking Fluid

One of the most useful tools watercolorists can use is a resist that helps preserve the white of the paper, or saves an underlayer of paint while additional layers of paint are added on top. Resists repel liquids, allowing us to dash in loose, colorful washes or thunderous darks and still have the brilliant contrasts possible when the lightest lights are revealed.

The most common masking agent today is liquid masking fluid, also called mask, masque, drawing gum or liquid frisket, among other things. It’s available from different manufacturers in either white or tinted form; the latter helps you to see where the resist has been applied.

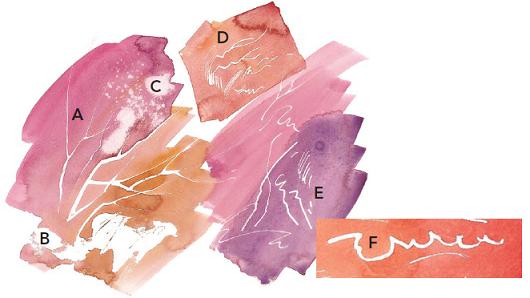

Several Ways to Apply Liquid Mask

A Feed tree-limb-like lines from the edge of a palette knife.

B Spread the creamy liquid with the flat of a palette knife.

C Spatter mask into a damp wash to make soft edges.

D Apply mask with an old-fashioned dip pen.

E Apply mask with a bamboo pen, a wooden skewer, twig, or drinking straw for even more linear effects.

F Use an Incredible Nib to apply mask. It’s a double-duty tool with a point on one end and a chisel-like nib on the other that allows a great deal of versatility. It’s easy to clean—once the mask dries, you can roll it right off the nib.

A bamboo pen works well to lay in thin lines of mask.

Tips for Using Liquid Masking Fluid

• Don’t shake it. That will make bubbles that can pop and let in paint where you don't want it.

• You can thin liquid mask with water. Just use a little at a time to avoid thinning too much.

• Don’t apply it with a good red sable. Use a nylon brush, an ink pen or a stick instead.

• Whatever brush you use to apply the liquid mask, wet it first with a bit of soap or detergent so it will rinse clean easily.

• Let liquid mask dry naturally. Drying it with heat can bond the masking agent to the paper, making it more difficult to remove.

• If you spatter liquid mask somewhere you don’t want it, just let it dry and peel it off before you paint.

• Once you remove the resist, you may want to use clear water to soften the harsh edges left behind to avoid a pasted-on look.

• You can use a mild liquid resist on an area of your painting that is already painted to protect a color instead of the white of the paper.

RESISTS

Liquid Masking Fluid continued

When you really need to preserve a white or a particularly difficult-to-paint-around shape, liquid mask is your friend! (Imagine trying to paint the spiderweb without the use of liquid mask.) It can certainly be done, but why not take advantage of the technology that exists? Watercolorists often need all the help we can get.

Protect Delicate Details With Liquid Mask

For this soft, misty self-portrait, done wet-into-wet, I just needed to protect a few tiny details—light-struck hairs, details of glasses and the like. I applied the mask with a masking fluid pen and let it dry thoroughly before starting.

Try Dropping Mask Into Your Wet Paint

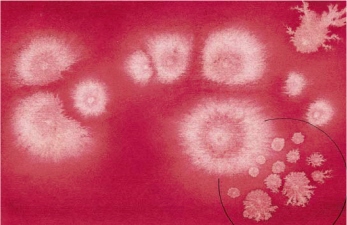

Here I dropped liquid mask into a wet Permanent Alizarin Crimson wash from the end of my brush. In the lower right circle, I made the cluster of smaller spots by dropping the liquid mask into the wash after it had lost its wet shine. I’ve used this technique to suggest seed heads or stars in a winter sky. Allow the wash to dry completely before trying to remove the mask.

Practice Different Ways to Apply Mask With a Brush

The strokes at right were protected by using a normal round watercolor brush loaded with mask. I made the larger spot in the middle with the side of the brush, and the small dots on the left by spattering on mask.

Removing Liquid Masking Fluid

• To remove liquid mask with the least damage to your paper’s surface, rub it lightly with a fingertip to start an edge, then pull off as much as you can at an acute angle to your paper.

• You can also use a rubber cement pickup (a square of India rubber), instead. Be gentle; don't scrub!

• And, some artists swear by removing mask with masking tape. Press the tape gently to the surface of the liquid mask and lift.

• If you splatter mask in a place you don’t want it, just wait for it to dry and peel it off before you paint.

Paint a Landscape With Spattering and Liquid Mask

DEMONSTRATION

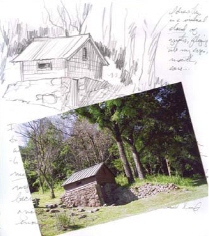

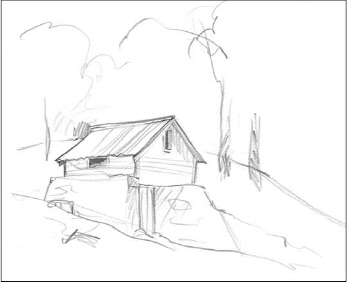

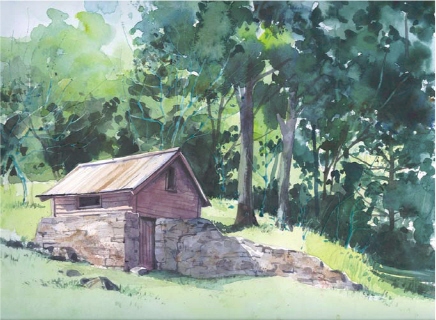

I loved this little building so much, with its deep stone foundation set into the hillside. All of the textures in this scene lent themselves to using a variety of techniques and materials.

Gather Your Reference Material

I sketched this scene quickly on location and shot a photo from the same spot.

1 Sketch in the Scene

Sketch in the roughest of guidelines with a pencil, then use a dip pen with a fine nib to lay in liquid mask and protect some of the trees and branches in the background.

MATERIALS LIST

Pigments

Burnt Sienna

Burnt Umber

Cadmium Yellow Medium

Indigo

Phthalo Blue

Quinacridone Burnt Scarlet

Ultramarine Blue

Brushes

½-inch (12mm) flat

nos. 3, 5 and 8 rounds

Oil painter’s small round bristle brush

Sharpened brush handle

Surface

140-lb. (300gsm) hot-pressed paper

Other

Craft knife

Dip pen with a fine nib

Liquid mask

Mechanical pencil

Palette knife

Small water sprayer

Sponge (natural)

2 Apply First Washes

Use a no. 8 round brush to apply a varied mix of Cadmium Yellow Medium and Phthalo Blue as the lightest washes in the grass and trees. Flood rich mixtures of Cadmium Yellow Medium and Indigo into the shadow areas. Use a mix of Burnt Sienna and Ultramarine Blue for the tree trunks.

Paint the first washes on the building with Quinacridone Burnt Scarlet mixed with a bit of Ultramarine Blue; a ½-inch (12mm) flat works well. Use a round brush to add more details in the building, using a mix of Ultramarine Blue and Burnt Sienna. Use a redder version of this mix, and apply a light, dry-brush application on the roof to suggest rust. Use variations of this mix on the stone wall as well, applying the paint roughly, spattering and blotting color.

3 Warm Up the Greens

To warm up the scene, dance a rich mix of Phthalo Blue and Burnt Sienna around the tree area using just the tip of your no. 8 round to suggest leafy areas. Make a rich wash of Indigo, Phthalo Blue and Burnt Sienna for the dark foliage, and drybrush and sponge it in the trees. Then spray clear water into the dark green wash to push back the paint and make rough-edged foliage masses.

Add in more trunks and branches with the same mix from step 2. You can drag smaller limbs out with a sharpened end of a brush handle, pulling the paint out of a rich, wet area in wonderfully calligraphic lines.

Use a no. 5 round to add more details in the stonework and on the roof and building, using various mixes of Ultramarine Blue and Burnt Sienna. Spatter a reddish version of this mix with the round bristle brush to give added texture to the stonework. Blot with a sponge to suggest stone.

4 Remove Mask and Add Depth to Trees

Once everything has dried from step 3, remove the mask and continue to develop the foliage using previous green mixes from steps 2 and 3; your no. 3 or no. 5 round will work well here.

Mask Protection

This detail shows you how clean the tree trunks and limbs remain when you remove the mask.

5 Add Final Details

Use the round bristle brush to make jabbing or stabbing upward marks or use the sharpened end of a brush handle to add grassy details.

Add a few unifying glazes with a thin wash of Phthalo Blue or Ultramarine Blue grayed with a bit of Burnt Sienna.

Add an old fence with Ultramarine Blue and Burnt Umber. A lighter or darker version of this same mix works for small twigs (try painting them with a palette knife), the shadows on the foreground stones and the small, sharp details in the building.

Finally, scratch out a few light-struck twigs and blades of grass with a sharp craft knife.

Softening Masked Areas

When you remove liquid mask you’re left with hard-edged white lines. You can create a more natural effect if you paint over these lines with a light glaze of color, and soften some edges with clear water, blotting up excess pigment. This will keep the trees from looking pasted on.

RESISTS

Permanent Masking Fluid

There’s a new addition to the traditional liquid mask choices—Winsor & Newton’s Permanent Mask. This new mask doesn’t get removed, so you won’t be able to paint over the lights it protects or soften an edge, but it can be useful when you know you want to retain a sharp-edged white with no alteration.

Applied too thickly, it will leave a shine which is also permanent. Experiment to find just the right degree of wetness on your brush, and be sure to wash the brush well immediately after applying the mask, or you’ll ruin it.

Practice Working With Permanent Mask and Your Paints

You can even mix the permanent mask with your paints instead of water, as I did here with the orange and yellow squiggles on the right. You may need to do a bit of cleanup with clear water once everything dries, as paint will sit on top of the masked areas (you can see this on the left in the blue, orange and red areas). I used a damp cotton swab to remove some of the dark paint from the yellow swatch.

White Glue as a Permanent Mask

You can also use white glue or school glue as a permanent mask or textural element in your paintings. Squeeze the glue right from the bottle onto your paper (it will destroy a brush if allowed to dry in it) and let it dry overnight. Then apply your washes of paint over the raised glue lines. The paint will puddle somewhat beside the glue lines; that’s part of the effect.

RESISTS

Melted Wax

Whatever you protect with wax stays white forever since it resists water. Historically, though, artists used wax as resists before liquid mask or rubber cement became available. If you are familiar with the art of batik, using melted wax with watercolor produces much the same effect, except that you can never completely remove the wax. This means, of course, that you can’t paint new color over it.

The batik tool called a “tjanting” is very useful in making wonderful, even lines with wax. A brush is an acceptable substitute and can make wonderful wave or surf forms with wax. Be sure not to use one of your good watercolor brushes though, as you won’t be able to remove all the wax.

Stroked on Wax

In this sample I applied strokes of melted wax with a bristle brush and allowed it to dry. Then I painted over them with Cadmium Yellow and Phthalo Blue. I like the way the watercolor washes bead on the waxed areas—it adds another nuance of texture.

Dripped on Wax

Now I’ve gone for a more controlled effect. Wax was dropped from the end of my brush and painted on in knob-ended lines. I was able to remove the majority of wax by putting the watercolor paper on a thick pad of newspaper, covering it with paper towels and melting the wax with a warm iron, but I still couldn’t paint over it with watercolor.

Melting Wax

Be careful when melting wax; it is extremely flammable. It’s best to use a double boiler. Remove it from the heat as soon as it is melted. This watery, liquid wax feeds easily through the tjanting—simply load it into the small receptacle with a spoon or other tool. If the wax is still liquid and hasn’t begun to cool and thicken, it will sink into your paper’s fibers with no need for later removal; if it does begin to thicken, you may want to pop off the hardened wax residue before continuing with your painting.

MEDIUMS

Gesso

Gesso is a handy tool borrowed from the acrylic painter’s repertoire—it is usually used to prime a surface before painting on it. You can coat your watercolor paper (or canvas or board) with gesso to make an unusual surface for watercolors.

The purpose of using gesso in a watercolor painting is to make your paper surface impermeable—your washes will sit on top of the surface and make interesting textures of their own. They will puddle, bubble and flow in unexpected ways that can give your work a fresh look. Your colors may look more intense on a gessoed surface, too.

Gesso can also be used to create unexpected textures for an abstract background. And, since the gesso allows you to lift almost back to white, you can work forward and backward, lifting and adding paint to get the likeness or effect you’re after. Working with gesso is almost like sculpting, and allows you to refine the image nearly indefinitely.

Collaging With Gesso

I painted a layer of gesso onto my watercolor paper, then attached paper towels, tissues, crumpled wax paper, wood chips and cornmeal to the surface with more gesso. (I typically recommend not using edibles in your tricks—see Wine. But, the cornmeal here is enclosed in a layer of acrylic gesso, similar to paintings I did using this technique thirty years ago, which are still untouched by insect damage.) When the gesso was completely dry, I added loose watercolor washes. This technique could inspire an abstract handling or part of a landscape.

Cadmium Red Medium

Phthalo Blue

Manganese Blue Hue

Ultramarine Blue

Quinacridone Gold

Raw Sienna

Burnt Sienna

Watercolor on a Smooth Gessoed Surface

Here I’ve begun each stroke on cold-pressed watercolor paper and finished it on the same paper with a coat of gesso. You can see the difference in how the surface accepts the washes.

Tips for Using Gesso

• Apply it as a smooth wash, then let it dry and sand it to a hard, fine surface to allow the paint you apply on it to puddle and run.

• Scratch or stamp into it when wet to create impressions, then paint over it when it dries.

• Apply it in a loose, scribbled manner for linear texture.

• Use different colored gessos or add your favorite colors to gesso to tint it.

MEDIUMS

Gloss Medium

Gloss medium resists watercolor washes, if they are quick and light. If the watercolor is darker or applied vigorously, it will overcome the medium, allowing a bit of polymer texture to show through—this can be a handy trick.

Painting on Smooth Gloss

Here Permanent Alizarin Crimson and Ultramarine Blue are contrasted on gloss medium for their staining and sedimenting qualities.

A A light wash of Ultramarine Blue is painted with a bit of Permanent Alizarin Crimson sneaked in.

B Permanent Alizarin Crimson is painted lightly and quickly on the surface.

C Permanent Alizarin Crimson is painted on thickly and with a degree of force over a layer of dried medium.

D Here I painted a strong, overwhelming wash of the Ultramarine Blue over the dried medium.

Painting on Scumbled Gloss

This time I scumbled on the gloss medium with loose strokes; you can see the subtle texture as it shows through the overwashes.

Painting Over Heavily-Textured Gloss

If you apply the gloss medium thickly and paint over it, the result will mimic impasto. Here, I used a variety of strokes and applications such as patting and scratching. I let the gloss medium dry, then painted on Ultramarine Blue and Quinacridone Burnt Scarlet to emphasize the textures in exciting ways. You can even rub off some of the paint with a damp tissue to bring out the texture of the dried medium, but be advised you will have some shine in these areas.

Lifting on Gloss Medium

Painting over a thin, smooth wash of gloss medium lets you lift even staining watercolors fairly easily, removing the color almost back to pure white.

Apply the gloss medium in a light layer with a wide, soft brush and allow it to dry, then add watercolor on top. Lift while the paint is still wet, or allow it to dry, then lift it with a clean, damp brush to loosen pigment and blot with a clean tissue.

MEDIUMS

Gel Medium

You may be familiar with the old acrylic painting standby—gel medium. It can be used in the same way as gesso, with the advantage of being transparent when dry. The only disadvantage of this medium is that it, like all polymer products, can be hard on your brushes and must be washed out immediately after working.

Apply Thick Texture

In this sample I built up various thick textures using gel medium, stamping into it with my hand (upper left) and jar lids (bottom left), and drew into it with the end of a brush (right). I then allowed it to dry overnight and washed color over top of the dried texture, wiping some color off here and there with a soft tissue. The gel medium resists the overpainted wash slightly, like gloss medium.

Add Texture to the Medium

Create effects either subtle or bold by mixing something textural such as sand or sawdust into the matte medium before painting it onto your paper.

Here I added marble dust (used by pastel painters to prepare a ground) to the gel medium and painted it roughly onto the paper then allowed it to dry thoroughly. It looked like a rough adobe wall to me, so that’s what I painted on top of the textured surface.

Use Matte Medium for More Subtlety

Polymer gel medium in the matte formula is a bit more subdued than the gloss; it’s not as obvious or intrusive.

Thin Your Paint With Gel Medium

You can see distinct brushstrokes in this sample, thanks to thinning the paint with gel medium instead of water. I used a fan brush with longer strokes to create an initial grassy feel. Then I used the same brush to make short, choppy, upward strokes below.

MEDIUMS

Texture, Granulating and Impasto Mediums

There are a number of new mediums on the market, and most of them, unlike polymers, are watersoluble.

That means different handling and different effects.

For most of these, you’ll want to have a dedicated palette, a dedicated water container and even a dedicated brush, as these mediums tend to lift back up into your wash and can be transferred back to the regular paints on your palette (a year later, my Permanent Alizarin Crimson still has a shimmer from my initial experiments with iridescent medium).

Many of these new mediums are novelty items, but they can offer some very interesting effects and are worth exploring.

Impasto Medium

There are several impasto mediums on the market meant to preserve brushstrokes or give a bit of texture to your ground. You can definitely see the brushstrokes here. I mixed color in with the impasto medium and brushed it on. I also did some finger-painting into and with the damp color.

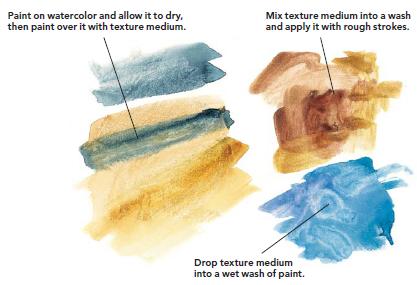

Texture Medium

This product creates an effect similar to gesso or gel medium, especially the more textured stuff. It has a somewhat gritty texture, but depending on how you apply it, you can get a little or a lot. Mix it with your paint or paint it onto your paper first and allow it to dry. It will lift during subsequent washes, though, so experiment with a light touch, and remember not to allow it to get mixed back into the paint on your palette.

Granulating Medium

Granulating medium is said to make any paint into a granulating or sedimenting paint. It works better to drop it into a wet wash than to mix it into the wash. And in practice, it works best in dark or rich mixtures.

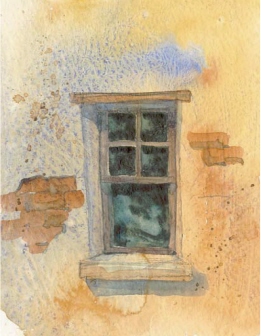

Using Texture Medium to Portray a Rough Surface

DEMONSTRATION

I was enthralled by all the textures present at a historic adobe structure site I visited. It was so gorgeous, I could have painted there for days! I decided this would be a perfect subject on which to try out texture medium.

MATERIALS LIST

Pigments

Burnt Sienna

Cobalt Blue

Phthalo Blue

Raw Sienna

Ultramarine Blue

Yellow Ochre

Brushes

½-inch (12mm) flat

no. 6 round

Surface

140-lb. (300gsm) cold-pressed watercolor paper

Other

Texture medium

1 Sketch and Apply Medium

Apply texture medium to the adobe brick areas and to some of the smoother parts, but not in the sky or background trees. In this rough sketch, the slightly tinted areas you see are where the medium has dried.

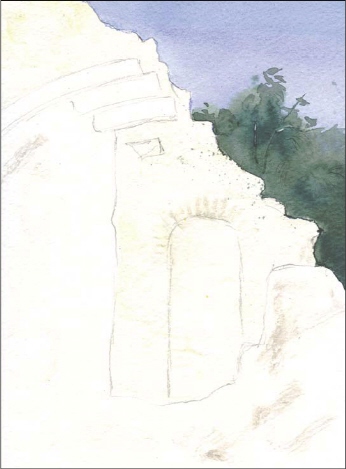

2 Lay in Background

In the areas untouched by medium, lay in quick, bold washes of Cobalt Blue with your ½-inch (12mm) flat for the sky. Use Phthalo Blue and Burnt Sienna to paint in the trees.

3 Add Color to the Adobe Structure

Add the finer foliage with a no. 6 round and the tree colors from step 2. Paint the building with Raw Sienna, Yellow Ochre and Ultramarine Blue. The result is a nice contrast between the smooth and rough areas, but the medium lifted when I added shadow washes and additional glazes, so the finished painting didn’t end up with quite the texture I had planned on.

MEDIUMS

Lifting Medium

This is a nifty product that you paint on the paper before you start to work. Let it dry in place, paint as usual, then even if you’ve used a staining pigment for its transparency, you’ll be able to lift most of it if you wish.

Practice Using Lifting Medium With Various Colors

Here I painted on Permanent Rose, Cadmium Yellow and Indigo after painting the paper with the lifting medium. I was able to lift all the colors easily with a brush dampened in clear water to loosen the pigment, then blotted it up with a tissue and added a few new details.

Gum Arabic as a Lifting Medium

In generations past, artists used gum arabic as a lifting medium, and so can you! You can apply it over your entire painting surface or you can paint small details with gum arabic. Let it dry thoroughly, paint over it, then lift just those areas.

You may want to draw in the smaller shapes you wish to lift with a pencil because it’s difficult to see where the slightly shinier gum is under the dried paint; the pencil lines help!

MEDIUMS

Iridescent Medium

Iridescent medium is a watercolor medium with tiny flecks of shine. You can mix it with your watercolor wash or paint it on once the watercolor is dry, but like other new mediums, you’ll want to have not only a water source and brush dedicated to use with this product, but a palette as well, or you’ll have shimmers in everything you do afterward! I usually use a small, white plastic plate for a palette when using one of these products.

Practice Different Ways to Apply Iridescent Medium

I used iridescent medium in place of water when applying the colors on the left. On the right, I allowed three strong washes to dry then painted full strength iridescent medium on the colors in strokes and spots. This medium is more obvious when seen on a dark color.

Try Using Multiple Mediums in One Painting

I experimented with a lot of the new mediums here. Most of them can be a bit tricky or tempermental, but they are fun to play with. Since most of these are novelty tools, it seemed appropriate to paint a dragon worthy of a fantasy tale!

I used texture medium on the mane and the front of the neck to create a scaly effect. I used lifting medium on the back of the neck, so I could lift out a scale pattern. I used iridescent medium on the lower part of the neck, both mixed into the deep Indigo Blue and then painted over once that was dry.

In the background, I spattered liquid mask before painting, allowed it to dry and painted over it, and while the wash was damp, I dropped in more liquid mask, as well as granulating medium and allowed everything to dry before lifting the mask.

On the dragon’s face, I used permanent masking fluid for the highlight in the eye, and regular masking fluid on the cheek, nose and ear.

Using Gesso and Iridescent Medium in a Portrait Painting

DEMONSTRATION

Gesso makes a versatile ground when painted on your watercolor paper and allowed to dry. It’s a fairly impervious surface, so you can lift watercolor back to its pure white. Using gesso is fun and feels almost like sculpting, while iridescent medium adds sparkle and pizazz!

MATERIALS LIST

Pigments

Burnt Sienna

Payne’s Gray

Brushes

½-inch (12mm) flat

no. 6 round

Surface

140-lb. (300gsm) cold-pressed watercolor paper

Other

Gesso

Iridescent medium

1 Create a Background With Gesso and Paint

Apply gesso generously and texture it with your hand for a semirough surface. Allow it to dry, then splash on rich, deep colors and some spatter of iridescent medium. I used a ½-inch (12mm) flat with Payne’s Gray and a bit of Burnt Sienna for warmth.

2 Lift Out the Portrait Basics

Lift out some of the lights in the forehead, nose and eye area with a no. 6 round, so you can begin to explore a likeness. Add some darks and move back and forth between lifting and painting, adding a darker value back in if you lifted too much, and vice versa.

3 Add Final Details

Create lost and found edges so your work doesn’t look pasted on. You can see a soft, lost edge on the shoulder and the lower lip. Hard edges can be seen at the forehead and cheek. Strengthen shapes and shadows. Be aware that the surface is a bit delicate, and your work will need to be framed under glass or otherwise protected, so the medium doesn’t lift or get scratched.

LIQUID ADDITIVES

Soap

A bar of soap is useful for more than cleaning up after a painting session. It has also been used for generations to give definition to your strokes as you paint to keep them distinct and obvious.

This is not the place for scented, colored or deodorant soaps; the purer the better. I use a cake of plain, white Ivory soap in my studio.

This technique is useful for painting a grassy field (each stroke suggests a blade or clump of grass), weathered wood, rusty textures, hair or anything where you want your individual strokes to stand out. It gives somewhat the same final effect as painting on hot-pressed paper but more controlled.

Texture Effects of Soap

Here I’ve tried to suggest a rusty texture with my soapy brush. The effect varies with the direction of the brushstrokes, the degree of manipulation (I textured it with the side of my hand and spattered in color from the brush) and the pigment color you choose.

Working With Soap and Paint

Soap lends a bit of body to the pigment, almost like working with a slight impasto. You can see each overlapping brushstroke, even though they were all painted wet on wet. (Normally, strokes painted wet on wet would run into each other and all have the same general hue.)

Here I mixed paint wth a little bit of wet soap, varying the color mixes a bit so you can better see the effect. There is a sense of depth and layering as the later strokes seem to come forward. There are bubbles in some of the strokes, which can provide extra texture. If you want to avoid this though, mix very gently, or allow the soap mixture to stand until all the bubbles burst before you paint.

LIQUID ADDITIVES

Coffee

While the long-term effects of coffee acids on watercolor paper may be an issue down the road, once in a while it is just plain fun to paint with coffee. If you’re stuck somewhere sketching without a source of water (but your thermos is full of coffee), go for it! It’ll mix up into a wash just as well as watercolor and clear water.

You can use strong tea for a similar effect, but as with coffee, the tannic acid in tea may not go the distance, over time.

Achieving Values With Coffee

Unless you’ve gone for some seriously stout espresso, you’ll want to build up layers to get good depth. Let each layer dry thoroughly before the next, and you’ll be able to get a decent dark. With patience, you should be able to get a good strong value.

Coffee Sketches

Here I used about 3 or 4 layers of coffee (black, no cream or sugar), and managed to produce a nice effect, painting the coffee washes over blue-gray watercolor pencil sketches.

LIQUID ADDITIVES

Wine

Using wine has the same fun-factor as coffee, with the same long-term permanence issues as coffee and tea due to the acids. But painting with wine can be interesting, and it gives you something to do in between sips!

Achieving Values With Wine

Unless you’ve gone for some seriously old merlot, you’ll want to build up layers to get good depth, the same as with coffee. Let each layer dry thoroughly before the next and you’ll be able to get a decent dark. With patience, you should be able to get a good strong value.

Wine Sketches

It helps to choose a full-bodied red wine like this merlot. I painted this flower with about 3 glazes, allowing each layer to dry thoroughly before adding another.

Consider the Permanence of Additives

It may be tempting to see what ketchup (or other edibles) might do in a wash, but resist that temptation! Mold, mildew, acid and hungry bugs might make your work nothing more than a memory. Even some paints will fade or otherwise degrade with light or time.

LIQUID ADDITIVES

Turpentine

You’ve heard that oil and water don’t mix; nowhere is it more true than in watercolor painting. You can put that truism to work in your paintings, though, for atmospheric or abstract effects that can be gained in virtually no other way. (And eventually the turpentine odor does go away!)

Mixing Turpentine With Watercolor

This is the result of first mixing a puddle of watercolor, then dipping my brush in turpentine. It starts out watery, like a normal wet-into-wet wash, then becomes nicely textured and scratchy at the end of the stroke.

Painting Over Turpentine

Here I’ve first wet my paper with a clean brush and turpentine, then painted over it with watercolor. The effect is wonderfully streaked and bubbled—it would be good for somewhat abstract background effects. (Smelly for awhile, though. And remember the flammability factor—read the warning label.)

LIQUID ADDITIVES

Rubbing Alcohol

Rubbing alcohol is delightfully unpredictable, like watercolor itself. Because it has a different chemical makeup than water, it resists the water in your wash. At the same time, it soaks into the paper more deeply than water does.

Depending on how you choose to apply this liquid aid, you may suggest bubbles underwater, flowers in a field, texture on an old rock, stars in an evening sky or simply interesting textural effects. You may want to use the effects in an abstract way. Rubbing alcohol works well for many applications; practice to get the feel of it.

Try Different Application Methods

Here I applied rubbing alcohol with a bamboo pen. I like the effect, though it is quite unpredictable. At the beginning of a stroke, more alcohol spreads into the wash. I especially like the frosty look of the thinner strokes. I can see this used to depict frost-touched weeds, sun-struck grasses, or just interesting linear effects for a background.

Try Alcohol on Different Colors

Just to find out how two different blues might react with alcohol, I painted a wash of Ultramarine Blue on the left and Phthalo Blue on the right and dripped in rubbing alcohol. To my surprise, I found the alcohol had a more noticeable effect on the intense staining Phthalo Blue than on the sedimenting Ultramarine Blue. Apparently Ultramarine Blue is too heavy for alcohol to easily move it out of the way.

Layering With Rubbing Alcohol

You can make very rich, complex surfaces with rubbing alcohol applied within layers of paint. Here I painted a mix of Sap Green and Phthalo Blue and allowed it to dry. I then painted a wash of Ultramarine Blue over the top, and while it was just losing its shine, I dripped, spattered and scribed rubbing alcohol into it. Then I spattered color over that. This could be undersea, or perhaps a granite wall in a shady canyon.

Rubbing Alcohol and the Three Bears

Just like Goldilocks, you’ll need to find that “just-right” time to add alcohol into your wash of paint. lf your wash is too wet, the alcohol you drop in will look wonderful for a second, and then it will simply fill back in, losing most of its effect. On the other hand, if your wash is too dry, the alcohol will have no effect at all. That in-between time is the one to shoot for to achieve fabulous effects.