THE PASSAGE PLAN

THE PASSAGE PLAN24 PASSAGE NAVIGATION

This chapter describes three different ways of making a typical 12-hour passage in a sailing boat, much of which is out of sight of land. Most people make such passages choosing GPS as their main fixing system. Many will also use waypoints in conjunction with a paper chart, while chart plotters are gaining rapidly in acceptance and popularity. Electronic navigation is here to stay, and mostly we are glad of it, but I would be selling readers short if I did not describe a system of sound practice using no electronic aids whatever. It’s not so long since we all had no option, and there will come a time for every one of us when circumstances throw us back on the basics. Besides, I believe that a skipper who can find a foreign port in indifferent visibility after 60 miles or more of dead reckoning will be able to extract far more benefit from a plotter than one who cannot. I am going to describe a passage from Yarmouth, Isle of Wight to Cherbourg in Northern France. First, I’ll take it from the standpoint of a navigator unassisted by printed circuit boards. Second, I’ll look at it as though I were using GPS and a paper chart; last, I’ll switch on the chart plotter and see what difference that makes.

You’ll notice that in each case, I keep up my log book religiously. The reason is simple. Whatever system I am working to, I must retain the capacity to work up an EP within an hour of my last known position. If I’m navigating by the ‘Four Ls’ of ‘lead, log, lookout and trust-in-the-Lord’, the information is of primary importance. If I’m using GPS and plotting on paper, I need an EP of some sort to check my GPS fix, even if I don’t plot these hourly in their entirety. This is not really to cover me in case the instrument is wrong, because this is highly unlikely. It is to supply a second opinion to my own workings. I know how easy it is to err while plotting a fix or to misread all those numbers when I’m tired, so I keep an old-fashioned plot running just to make sure. And of course, if I lose my GPS, I’ll be in a strong position to carry on regardless.

Even with my brain in plotter mode I must keep up my log book so I can step seamlessly into paper-chart navigation if one facet of the interfaced system goes on the blink and drags the rest down with it. This has happened to me before, as it has to many others, but so long as there’s a recent lat/long position with a course and distance recorded between it and now, there’s really no problem. I just produce the chart, plot my last position, work in an up-to-date EP, then lay off a new course. Easy. If the log book’s staring at me blankly, I might as well be on the Moon!

THE PASSAGE PLAN

THE PASSAGE PLAN

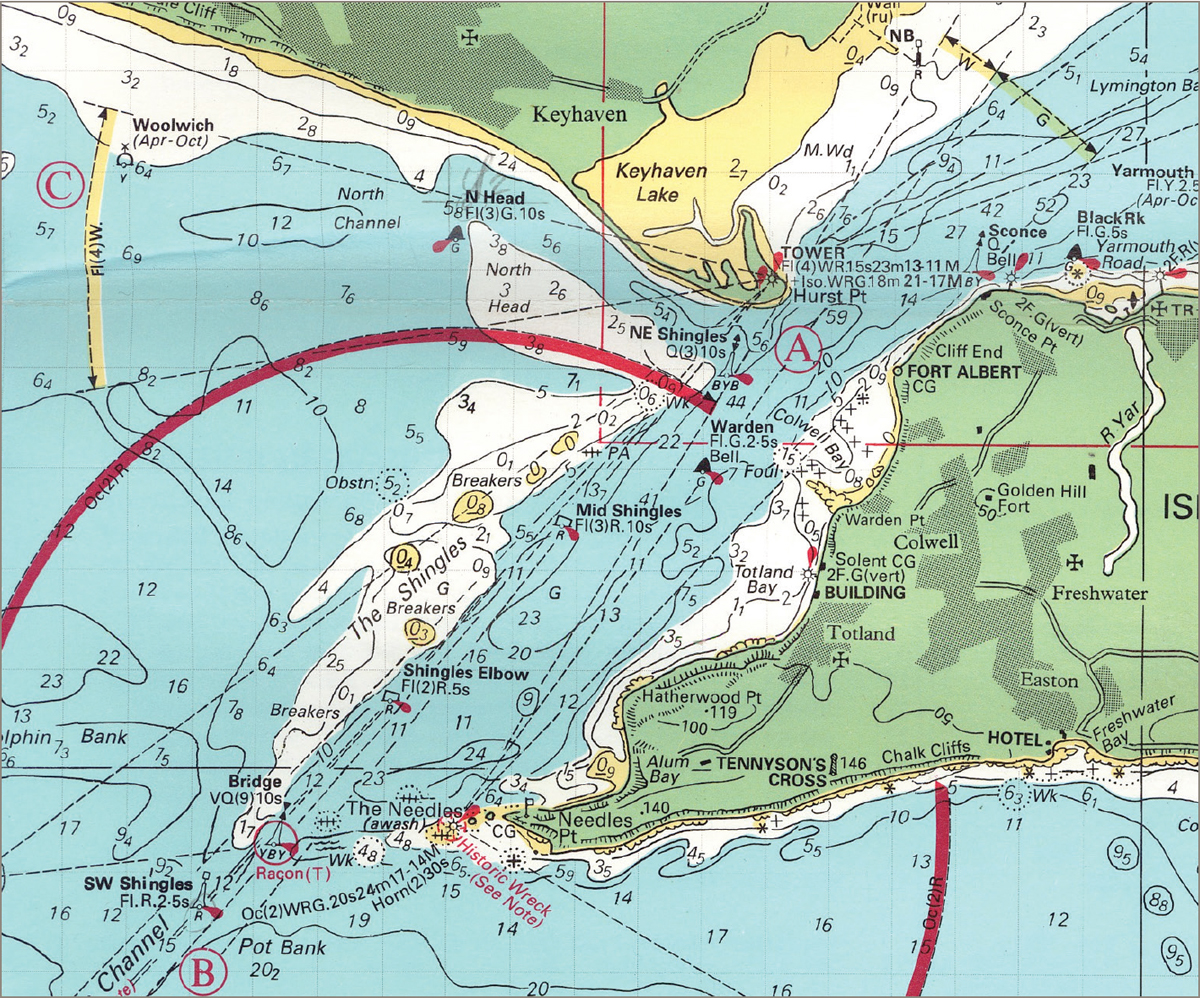

The wind is forecast westerly, about force 4, and it’s spring tides. A quick look at the passage chart reveals here that the journey breaks into two parts. The first will be a 5½-mile beat down to the buoy labelled ‘Bridge’ just west of the Needles light. I might get lucky and be able to lay this in one, but the frustrations of a lifetime suggest that I shan’t. I’ll therefore definitely need fair tide for that section because I can see from the atlas that streams run strongly.

Thereafter, it’s about 60 miles almost due south to Cherbourg. A study of the tide tables tells me that streams off the French coast run like an express train, so I’ll plan to arrive uptide of my destination, even if that means I’m a bit downwind. Making up ground with a 3-knot tide under you is easy. Trying to fight back against it after a long day is brutal. I don’t need that, so I’ll make sure right from the outset that it doesn’t happen.

The tide will be ebbing west past Yarmouth from 0300 until 0900, which will get me off to an early start. It’s August, so dawn is around 0530. I’ll turn out at 0500 and chuck some bacon in the pan to make butties; my shipmates will soon smell it and wake up slavering. Far more civilised than booting them out of their bunks. Our boat is 35 ft long and I expect we’ll be out and under sail by 0600. We’ll have the earlymorning forecast under our belts, and if nothing has changed, we’ll go for it. No need for any alternative heavy weather harbours in force 4 – a good thing, because there aren’t any mid-Channel!

The passage from Yarmouth to the Bridge buoy.

The passage from Yarmouth to the Bridge buoy.

Our VMG (velocity made good to windward) should be around 3½ knots, but with 2½ knots of tide we’ll be out by the Bridge in an hour or so – could be less if we get a slant. Then we’ll set course straight down the rhumb line and see how fast we’re going. The likelihood is we’ll make 6 knots. If we don’t, we want shooting. That’ll be around 10 hours to Cherbourg. If so, and we’re at the Bridge by 0700, we’ll have the last 2 hours of the west-going tide, then we’ll receive the full 6 hours of east-going, followed by a short, stiff shove to the westward at the end. I’ll add up all the east-going and subtract the west-going from it. I’ll also make up a little table showing what the tide will actually be doing at my probable hourly positions, assuming 6 knots or so. That will be useful for plotting EPs and will save trouble on passage.

I’ll expect a net tide vector of around 5 miles to the east, so I’ll steer initially for a point 3 or 4 miles west of the rhumb line. There are two entrances a couple of miles apart, so we’ll head for the eastern, or uptide, one. That’ll give us an extra 2 miles in the bag if need be.

I’ll have plenty of time to work up a pilotage plan for my arrival on the way.

There’s one final issue. A note on the chart advises me that although the central Channel is not officially a TSS (Traffic Separation Scheme), I am told to cross the shipping lanes as nearly as practicable at right-angles. East and west-bound big-ship traffic can be expected in the area I will be crossing and the lanes are shown on the chart. Complying with this instruction will be easy with this wind and weather. It will also place me even further uptide when I reach the other side, so I’ll do it to the letter. If I were closehauled and unwilling to bear away, or otherwise hampered, I might stretch the wording of ‘as nearly as practicable’ a little, but I’d make sure that I hit that right-angle if any shipping looked like coming close enough to be interested in me. In fog, I would cross at right-angles like a shot, even if I had radar, and I’d make sure it was my course that made 90°, not my track, because that is what the regulations specify. If the area were a full-on TSS, there would be no discussion at all. Right-angles it would be.

THE PASSAGE WITHOUT ELECTRONICS

THE PASSAGE WITHOUT ELECTRONICS

Setting sail from Yarmouth with the rising sun behind me, I’ll stand out on the port tack to get clear of the rock off the harbour, then eyeball it down to the Bridge, tacking as dictated by commonsense. There are plenty of buoys and they should be visible. I’ll stay out of Colwell Bay (rocks), and I’ll take special care to tack in good time as I approach the Shingles Bank marked by red buoys. Once I’m clear of the Needles, there’s plenty of water before I reach the Bridge buoy to set course early, but I don’t know what the sea conditions will be like, so I’ll take that as it comes.

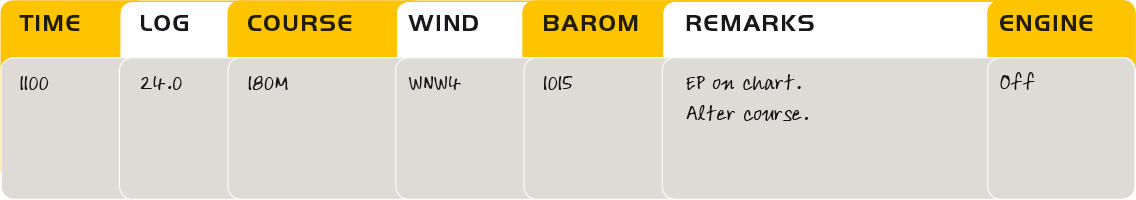

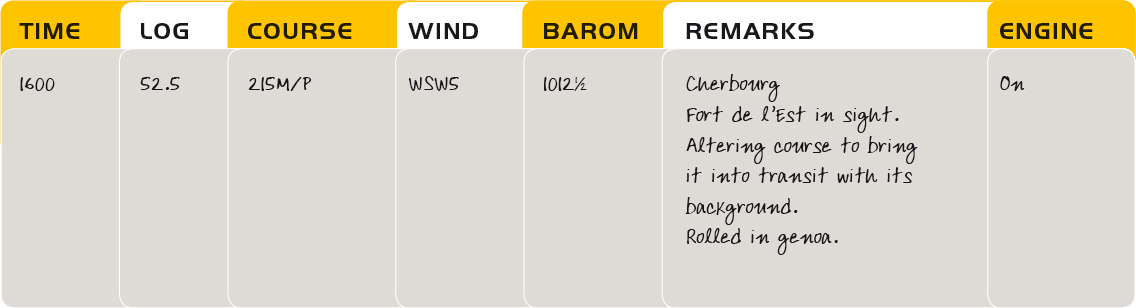

The log book might look like this:

A position of some sort every hour is sound policy, and since I can see the land clearly I should take a fix. In any case, right now it’s easier to do that than to work up an EP. I’ll cross-reference it against my course steered and distance run, but I won’t physically plot the EP. So long as it all stacks up, I’m happy. At 0920 the land is fading from view and I take a departure fix, which gives me my last certain position before I sight France. After this, it’s all EPs.

Notice that I have plotted my EP this time. That’s to make sure the tide is behaving as expected. If it hadn’t been I could have modified my course to steer. It was, so I haven’t. It also gives me a confirmation of this important fix.

Things now proceed systematically. I go off watch, leaving instructions for the hands to record the log each hour and to call me as we approach the shipping lanes. They can manage without me until then and I need to stay fresh, so it’s down to the bunk for me with my favourite book. If I don’t do this, I’ll just sit up there with things going round and round in my head. Far better to take a break.

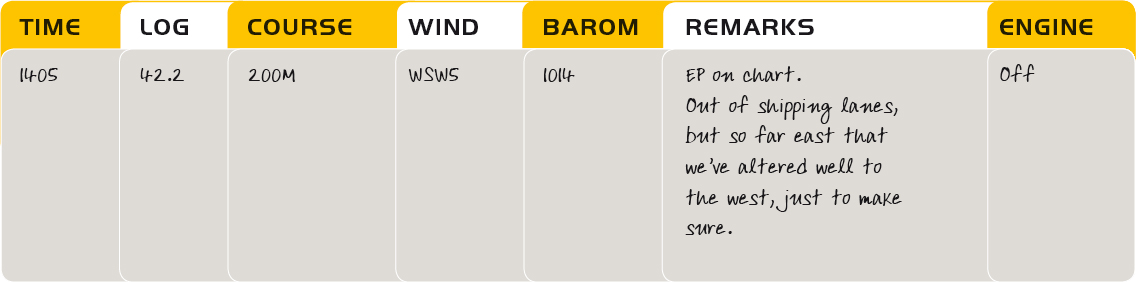

This course alteration is for the shipping lanes. The wind has veered a touch, freeing us, and I have no compunction about giving away a bit of ground to windward. I make up the plot now I’m awake, and place a fresh EP on the chart.

This next EP shows that my keenness to comply with the traffic regulations has left me well to leeward and the wind has backed unkindly. Things aren’t looking so good and we’re really going to need that westerly set.

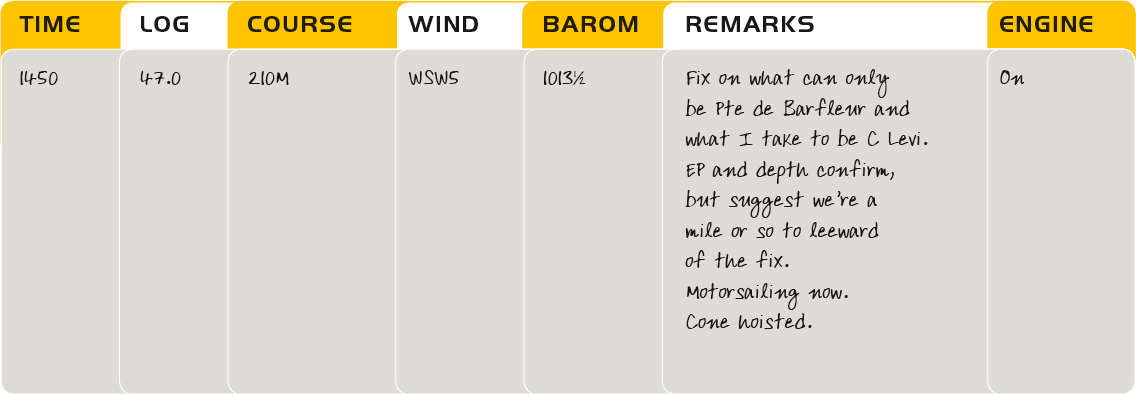

Here’s the next log entry:

Note how keeping the plot going has enabled me to make the right decision about motorsailing and has helped me identify my landfall with confidence. We went so far east looking for the first of the west-going tide that we’ll end up beating at this rate.

But fortune is kind, and my landfall fix indicates that I’ve found the tide earlier than I expect. Deteriorating sea conditions as the stream begins to set against the tide have already suggested that. I’ve logged my positions and even if the fog came in now, I’d stand a good chance.

A safe arrival. Note how the plot was maintained throughout.

The Central Channel.

The Central Channel.

THE SAME PASSAGE USING GPS AND A PAPER CHART

THE SAME PASSAGE USING GPS AND A PAPER CHART

Planning

My plan for this trip using GPS would be very similar to the non-electronic equivalent, except that I’d plot a number of waypoints. They’d be punched into my receiver and double-checked the night before. I wouldn’t use a formal GPS route for this passage in a sailing boat because I’ll be beating to start with and couldn’t possibly stay anywhere near it. Crossing the Channel, the tide may well force me to modify my plan to suit boat speed, so sticking to a route might do me no favours. Instead, I’ll place my waypoints as follows:

One at my departure point (the Bridge buoy). This will be a useful plotting aid in the early stages.

One at my departure point (the Bridge buoy). This will be a useful plotting aid in the early stages.

A second at the projected EP where I leave the shipping lanes. I could put one at the beginning of the lanes, but there really wouldn’t be much point because I’m obliged to cross them at right-angles wherever I actually fetch up. However, the point at which I leave them is a good position from which to shape a new course for Cherbourg based on where I really am at that time. By comparing this waypoint with a GPS fix, I’ll be able to assess what the tide has actually been doing and adjust my new course on that basis. Note, however, that the waypoint exists purely for planning reasons. I don’t have to go to it. Indeed, if I try to do so, I may end up forcing the boat to offset more for the tide than she needs.

A second at the projected EP where I leave the shipping lanes. I could put one at the beginning of the lanes, but there really wouldn’t be much point because I’m obliged to cross them at right-angles wherever I actually fetch up. However, the point at which I leave them is a good position from which to shape a new course for Cherbourg based on where I really am at that time. By comparing this waypoint with a GPS fix, I’ll be able to assess what the tide has actually been doing and adjust my new course on that basis. Note, however, that the waypoint exists purely for planning reasons. I don’t have to go to it. Indeed, if I try to do so, I may end up forcing the boat to offset more for the tide than she needs.

My third waypoint will be at Cherbourg, Fort de l’Est. Some people might find it useful to place one 5 miles out and uptide. The reasons would be obvious and I’d have no quarrel with this. For myself, the arrival waypoint will suffice.

My third waypoint will be at Cherbourg, Fort de l’Est. Some people might find it useful to place one 5 miles out and uptide. The reasons would be obvious and I’d have no quarrel with this. For myself, the arrival waypoint will suffice.

Notice that even though I’m using GPS, I plan to allow the boat to drift with the tide to a controlled extent. I could use the instrument’s cross-track error (XTE) function to keep her smack-bang on the rhumb line all the way, altering course to compensate for the tide, but if I did I’d end up sailing many miles further than I need. If you’re puzzling over this concept, take a quick look back at Chapter 20, where all will be revealed.

Executing the passage

Piloting

The early part of the passage is carried out in much the same way as if there were no GPS. It’s pilotage down to the Bridge buoy, then I set course just as before.

On passage

Once clear of the land, I use the fixing power of GPS to plot an hourly position of known accuracy, double-checking each lat/long fix against bearing and distance to one of my waypoints. My log book looks like this:

Note that I now have a column for position. Previously, I plotted this on the chart, because it was inevitably somewhat imprecise for numerical definition to the second decimal point. Now, however, I know where I am and it makes sense to log the position as well as plotting it. This not only allows a back-check, it also means that unskilled crew members can jot down a lat/long on the hour if the navigator is off watch. Working back from these positions, he can then see exactly where he’s been, and if the GPS fails, he knows where he was at the last reasonable moment before the lights went out.

Having an accurate fix to compare with my projected ‘EP waypoint’ when I come out of the shipping lanes helps me quantify how far east I’m being set. I can therefore alter course with more confidence. The tide has yet to turn, however, so I will continue to shape a course rather than follow a GPS bearing to my destination waypoint.

Nearing the destination

Round about the time I make landfall, I’ll begin using GPS to compare my COG (course over ground) with the bearing of Fort de l’Est. I’ll also be logging my position as ‘Fort de l’Est 14.9M, 211T’ in preference to my mid-Channel lat/long.

Knowing that the tide will strengthen, I’ll initially shape for a point uptide of the waypoint’s bearing, but as I come within an hour or so of the fort, I’ll begin steering to have the two figures coincide. If it were foggy, I’d refine the arrival waypoint to be in a very safe place after double-checking datum one more time. Then I’d reactivate the GoTo function and follow the XTE screen ‘right down the middle’ for the run-in. If ‘vis’ is good, as it is on this passage, I’ll forget the GPS once I’m absolutely certain about what I am seeing. I’ll switch into eyeball mode a few miles out and use natural transits to home in as before.

THE PASSAGE WITH A PLOTTER

THE PASSAGE WITH A PLOTTER

The plan

As with GPS and paper chart, using a plotter really changes very little at the planning stage. Depending on the machine, I might plot the same waypoints as before, but if it has the capacity to pre-plot the whole passage by predicting the tides as well, the only one I’d enter would be the arrival waypoint. While my own hardware plotter doesn’t have this capacity, I also ship out with a PC plotter that does. I’ll use this to draw a curving electronic line on the electronic chart showing where it expects I’ll be all the way at 6 knots. It won’t work out perfectly, of course, because these things never do. For one thing, I won’t be doing exactly 6 knots. Neither will the tide behave precisely as the computer predicts, but the line will at least show me approximately where I ought to be as I work my drifting track. As such, it will be very helpful for decisions about course changes. The graphic display may also prove handy in that if I find I’m being set way off track even before I reach the shipping lanes, I can modify my course visually without having to read and input numbers.

Theoretically, of course, I could do all this using GPS and a chart by pre-plotting all my EPs, but the hard fact is that few people would want all that trouble, especially if they’re feeling a touch ‘Tom and Dick’ down below at the chart table with the boat lurching along. The plotter makes it easy.

Even using a plotter, I still plan an arrival waypoint because it enables me to read quickly how far I have to go and how the bearing is shaping up numerically as well as graphically. The ETA it so boldly projects will be a load of nonsense until the tide has settled down at the end of passage, because not even my present PC plotter can crunch the numbers for the turning stream, but no doubt this will be possible as well in due course. Sooner or later, we’ll be able to sail our boats from the spare room at home…

Executing the passage with a plotter

Piloting

We’ve said very clearly in the pilotage chapter that plotters may be of limited use here, but it doesn’t do to make too many hard-and-fast rules at sea, and the initial part of our passage is a classic case where they are just what the bosun ordered. Even if the buoys are hard to spot, keeping an eye on that little boat tracking across the chart tells me exactly when to tack. I don’t get silly about it and go zooming in to the last 50 yards because I don’t have to. I just use it to remove any vestige of stress that might be left if the passage were unfamiliar to me. Lovely!

On passage

Although I’m using a plotter, I’ll still let the boat slide away to the eastwards just as before, and my log book contains exactly the same items as if I were on ‘GPS and chart’. If I’ve a big enough plotter screen, the chart might even stay in its locker, but I’ll have it ready in case I need it. And if I do, my last known position will still be my starting point, so I log everything I might need.

A successful arrival, and the Bar du Port is just around the corner.

A successful arrival, and the Bar du Port is just around the corner.

I’ll probably have the projected track switched on from the start, because it’ll be handy in the pilotage. It won’t do much for me for a few hours after the Bridge buoy, because it will show me ending up further and further to the eastwards, so I’ll carry on more or less as if I were using a paper chart until the boat is homing in on Cherbourg. Once the tide has settled down into its final west-going mode and I’ve reached the point where I’d be adjusting my course steered on the basis of the waypoint bearing and my COG, I steer so as to put the projected track line on to Fort de l’Est, and keep it there. It’s just like running an XTE screen really, but it’s a whole lot easier.