MAINTAIN YOUR PLOT

MAINTAIN YOUR PLOT26 FOG

No one born of woman likes fog at sea. It strikes us more or less blind, which the sighted majority are unable to come to terms with. A sharp summer gale may be grist to a sailor’s mill, but whoever he is, fog causes the gnawings of unease deep in his vitals. At the worst, it can frighten him into irrationality.

These anxieties are akin to fear of the dark. Just as the growth of adult reason dispels this childhood horror almost completely, education and experience go far towards neutralising fear of fog, though for most of us, the ghost of doubt always remains.

There’s nothing inherently lethal about fog. It’s the same stuff as that magic mist that creeps across the fields on late summer evenings. It doesn’t even make you ill, but at sea it means you can’t see where you are going and neither, in all probability, can anyone else. Radar helps, of course, but many of us don’t have a set, and some who do cannot use it to its best advantage. The result is that we are liable to collide with vessels unknown, and while, with sensible use of GPS, we are no longer in doubt of our position, we are still thrown entirely on to our instruments if we are to keep out of navigational difficulties. Without GPS, we are not necessarily lost, but we are undoubtedly exposed to substantial additional danger.

The best thing to do about fog is to listen to the forecast before you leave harbour and give the whole project a resounding miss if fog is predicted. Most of us suffer from the besetting sin of hoping for the best, however, so for those walloping bravely on regardless, here are some useful policies to adopt.

MAINTAIN YOUR PLOT

MAINTAIN YOUR PLOT

The most important single action to take when your eyebrows start getting dewy, when the navigation lamps develop a halo and when damp starts dripping from the mainsail even if it’s not raining, is to determine your position. If it’s not foggy already, with signs like these it soon will be. If, by any chance, your GPS is not working, make sure that you fix your position visually at the last possible moment. If this proves impossible, work up a current EP. It is from this position that all your tactical decisions will stem, so it needs to be as accurate as you can make it. If you’ve been careless about running your plot, you’ll regret it now. Even if you have a GPS receiver, a solitary unconfirmed electronic fix sitting self-consciously on a clean chart does little to dispel the anxiety of a prudent mariner.

FOG SEAMANSHIP

FOG SEAMANSHIP

As soon as you have serviced your primary need by plotting your position, you can attend to the immediate well-being of ship and crew.

Double the lookout

This is always worth doing if possible. The collision regs demand it. Furthermore, if visibility is 164 ft (50 m) or less, and your converging speed with another vessel is a boat’s length per second, as it often is, one lookout is just not enough. Ideally, the extra lookout should be stationed on the foredeck where he will be comparatively undisturbed by engine noise if you are motoring. He’ll be listening for foghorns, engines and even bow-waves. Knocking the engine off every few minutes will help enormously. On some vessels it is also useful to contain the drone of the machinery by keeping the hatches closed.

The direction of sound is often distorted by fog, so be circumspect about leaping to conclusions. It is, however, unusual for a foghorn on the port bow to sound as if it is coming from the starboard quarter. If a sound is repeated at regular intervals it’s often possible to detect a pattern in its direction that will prove useful. For example, homing in on a siren at a harbour mouth can usually be achieved successfully, given a reasonably wide safe path of approach.

Listen out for unexpected sounds and use them creatively. I once navigated along the north coast of Norfolk on a mixture of echo sounder, compass, wild-fowlers’ guns and dogs barking on various bathing beaches.

Be seen

Hoist your radar reflector, if it isn’t already aloft; it is your number one protection against collision. Turn on your navigation lights, as required by the Colregs, and begin sounding your foghorn if it seems remotely possible that anyone may hear it. One long blast if you are under power (Here I come, sounding one); one long and two short blasts if you are sailing.

Leave your mainsail hoisted if you are motoring. Not only will it dampen your tendency to roll, it will also increase your prominence to a lookout high up on a ship’s bridge.

Prepare for the worst

One of the few occasions when those able to swim should wear lifejackets at sea on an undamaged yacht is in fog. If you were run down you could sink virtually without warning. If all hands have their ‘lifers’ round their necks, there will be no unseemly scrabble for them in a rapidly filling cabin, or subsequently in the water for the only one that bobs up after the bubbles have stopped rising.

Don’t let anyone fall overboard in fog. This may sound obvious, but even so, it does no harm to remind the more boisterous of your crew that if they go over the wall, they may be lost to view and to everything else. If in doubt, clip on.

FOG TACTICS

FOG TACTICS

Having prepared your ship and crew (a matter of minutes) and plotted your whereabouts, you are now in a strong position to decide what you should do.

The first consideration is not to be run down. If you have a radar set, it will be warmed up by now because the Colregs specifically oblige you to use it in restricted visibility. Plot your contacts, take the relevant avoiding action, but don’t forget that the fishing boat that may sink you is out there in the real world, not lurking in your glowing tube. In other words, use your radar by all means, but don’t neglect your lookout.

If you have no radar, clear yourself right away from the remote vicinity of any avoidable areas of shipping concentration. Having done this, you can decide where to go next, if anywhere. While you are inspecting the chart, the watch on deck can make an informed guess at the range of visibility. Try to relate this to the scale of known visible objects as they appear: buoys are best, seabirds come next and waves are last but are still better than nothing. If it’s oily calm, good luck to you. Without birds, buoys, passing seaweed or convenient flotsam you’ve nothing to go on but your wake and the length of your yacht, so unless you are very rich, your guess is unlikely to be accurate.

Should you be well out at sea and clear of shipping, you will undoubtedly plump for option number one. This is simply to press on with caution at a safe speed and maintain your plot. A variant of option one, when no better possibility presents itself, is to stay at sea and heave to, even if your passage is not advanced by doing so. At least you are safe from rocks and shoals out there. Options two and three involve the shore.

A fog bank can creep up unexpectedly so keep a weather eye open.

A fog bank can creep up unexpectedly so keep a weather eye open.

Fog – is it set in for the day, or is it just land fog that the sun will burn off any time now?

Fog – is it set in for the day, or is it just land fog that the sun will burn off any time now?

If there is no convenient safe harbour, you might choose option two. Work your boat into water too shallow for commercial vessels, then either anchor or stooge about until visibility improves.

There is much to be said for this tactic, particularly if the wind is offshore. So long as you can find an area clear of dangers, it involves little navigational finesse and gives you a good chance of keeping out of trouble. If you have no GPS, you can still use your sounder and work a plot from your starting-point. This will give you an approximate position, which may well be good enough to be safe.

The big negative feature of option two is that it leaves you at sea. You’ll be more popular with your crew if you can manage to get in somewhere.

Option three is to go looking for a harbour. Once secured alongside, you are as safe as you can be, so long as you can enter this happy state with minimal risk of stranding in the search. GPS and radar, if you have them, make the whole proposition infinitely less stressful than it was even in the 1980s. However, since nothing under heaven can be absolutely relied upon, we’ll first consider the business from the viewpoint of Natural Man, unassisted by anything but traditional systems.

If, by any chance, you find yourself with no electronics working save your echo sounder, one thing not to do is aim straight for the harbour of your choice. Unless visibility is within the error of your EP, you will almost certainly miss. You won’t know whether to turn to port or starboard when you see the beach or come on to soundings, and you will then be officially lost.

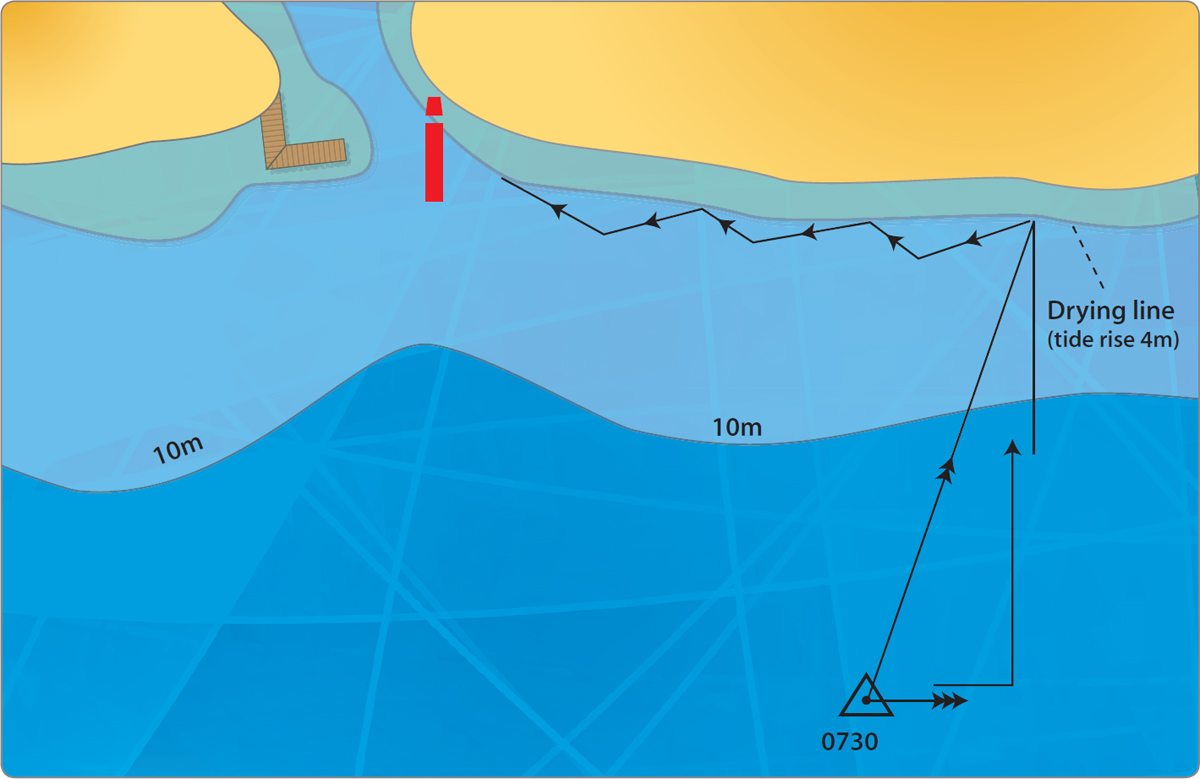

Fig 26.1 Finding a harbour entrance in fog.

Fig 26.1 Finding a harbour entrance in fog.

Well offshore, with no dangers near by, in good visibility, you shouldn’t mind at all if you are uncertain of your position to a mile or so. As soon as visibility deteriorates, however, paranoia sets in and we feel we must know our exact whereabouts. If we could see where we were going, we would be content to squirt our boats in the general direction of our destination, then refine our course as we came closer in. In fog, we can do exactly this, but one extra factor is required. Without the far-seeing eyes of electronics, we must ensure that we miss our destination, and we must miss it by far enough to one particular side, so that there can be no possible ambiguity.

Choose the side with a safe depth contour running up to the harbour mouth (Fig 26.1). If there isn’t one on either side, forget the harbour, even if you have a GPS, unless either it is cross-checked by radar, or you are prepared to take the chance that it will not let you down at the crucial moment. Your electronics are going to be used to assist the classical approach mentioned below. They don’t change anything radically unless you are equipped and confident with radar. They merely make the job easier and even more certain. If you rely on them implicitly and they go down or misread, you’re in real trouble.

If a good, clean contour presents itself, run in until your sounder picks it up, then turn along it towards the harbour. In areas of big tidal rise you’ll have to reduce your depth to soundings, but that is the only complication. Steer inshore across the contour until depths shoal, then come out 40° until you are to seaward of the line. Now come in again, and so on until you find your landfall buoy, or harbour wall, or even the suddenly deep water of your river mouth.

The technique is simple and, given suitable topography, it works every time.

A wise skipper, with GPS but no radar to supply a second source of electronic position finding, does well to adopt this policy. By refining his position and reassuring himself with the electronics, success will be assured. If, on the other hand, GPS alone is used to steer direct for the harbour, unless a fortuitous line of soundings can continuously confirm the position, the only other source of input would be what may prove a fairly dubious EP. While the EP for a sailor running in for a depth contour well to one side of a harbour entrance demands only minimal accuracy, to achieve the pinpoint precision of a direct hit in 50 yards visibility it would need to be phenomenal. The GPS would therefore be an unconfirmed source of data. If it went down, all might be lost, so unless a sure-fire route of retreat is available, stick to the old ways and augment them with GPS accuracy. If it fails, no problem! Shrug your shoulders and take more notice of the echo sounder. If you are really confident of your GPS receiver or plotter and have a spare tucked away ready for action, there’s no reason not to steer directly for a destination in fog. However, a contingency plan is important, lest the GPS satellites be jammed at some critical moment. This is unlikely, but the contingency is becoming more common. The plan will either be to aim off and go into a traditional ‘contour-running mode’, or just to turn around, sail back out to sea and wait.

| SKIPPER’S TIPS | Buoy hopping |

| Sometimes in fog it’s helpful to run from one buoy to the next, when there are enough of them to make success probable. Buoy hopping with GPS – and especially radar – presents few difficulties, and it can be most reassuring to see the metalwork loom out of the gloom. Without these aids, it should only be attempted when to fail would not be catastrophic. Miss one buoy and you’ve had it, so don’t rely on the technique exclusively if in doubt. | |

If visibility is sufficient to be certain of finding the ‘visibility bubble’ around the next buoy without electronic assistance, you are in good shape, but if the fog is thick, the buoys far apart and the currents strong, you may be backing a lame horse. Always remember that you can take a personal observation of set and drift with great accuracy (see Chapter 15). |

|