In the first chapter, we gave a broad historical sketch of the development of US health care up through the eve of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), and then in the following two chapters we studied the FDA and Medicare in detail. In the next part of the book, we will show that the ACA won’t solve the festering problems in the US health care system, but rather, will exacerbate them and hasten the degradation of the private sector.

The present chapter serves as a transition from the historical trends to the present realities of America under the ACA. In this chapter we summarize some of the major problems with the economics of health care in the United States. Once we correctly identify the problems in this fashion, you will easily see that the ACA only makes them worse. The following problems are not necessarily listed in order of importance, but taken together provide a quick summary of what the heck went wrong with America’s medical care.

There are legitimate reasons why people associate health care with insurance, but the two concepts are quite different. If we are to make sensible decisions—regarding both government policy and personal medical options—we need to keep these concepts distinct. The popular tendency to interchange these terms inappropriately is epitomized when people refer to the Affordable Care Act, which is a massive piece of legislation dealing with insurance, as “health care reform.”

Note that we are not merely being quibblers over grammar here. One of the biggest problems with the entire US health care system is the predominance of third-party payment. Thus, when people casually conflate health insurance and health care, they are unwittingly perpetuating the problem; it is impossible to fix something if your very vocabulary makes the solution impossible to articulate.

It is understandable that Americans conflate health care with health insurance, because “health insurance” no longer functions as insurance. The way insurance is supposed to work is that you enter into a contractual arrangement with the insurance company: you the policyholder make premium payments, and if a well-defined event occurs, the insurer sends you a specified amount of money. Note that if the event occurs and you receive a check, it’s not even necessary for you to spend the money replacing or repairing the loss; the purpose of the insurance is to financially compensate you to offset the bad fortune of an unlikely event that could strike many people but happened to hit you.

By their very nature, “insurable events” should be expensive and unpredictable for the specific policyholder. It wouldn’t make any sense to ask your car insurance company to reimburse you for your oil changes, because they would simply have to charge you on the front end what they knew you’d be requesting on the back end—and then they’d slap that on top of the actual insurance against rare-but-expensive events like a collision. However, in the unlikely event that you do need your car insurance company because of a serious accident, then you will typically be insured for the full value of the property.

Notice that typical health insurance in the United States operates nothing like this model. Many health insurance policies cover routine care such as office visits, the human equivalent of an oil change.1 Moreover, if a specified “health event” occurs, the policyholder (typically) can’t simply request a check for the amount listed in the contract— the way a motorist could have his new car totaled, take the insurance money, and switch to a cheaper vehicle to pocket the difference. On the contrary, with health insurance the policyholder (typically) only gets paid—with the payments very often going right to the provider— for services actually performed to address the “health event.”

Another difference between health insurance and other types of insurance is that many health plans—even “good” ones offered by reputable employers—have caps on total coverage, or insist on co-pay percentages that could overwhelm the policyholder in the event of a serious illness. In his book critiquing the US health care system, economist John Goodman first quotes a news article explaining that some employers are requiring employees to pay a quarter, a third, or even more of the cost of “specialty drugs.” Goodman then comments: “Increasingly, the health plans employers offer defy all of the traditional principles of rational insurance, which require people to pay out of their own pockets for the expenses they can afford but protect them against catastrophic costs they cannot afford.”2

THE POLITICS OF U.S. HEALTH CARE

“In the US Medicare program, policymakers achieve through patient cost sharing what other countries achieve through the rationing of services: They punish the sick to reward the healthy. For example, although basic Medicare pays for many minor services that most seniors could easily afford to purchase out of pocket, it leaves the elderly exposed to thousands of dollars of catastrophic costs. This is exactly the opposite of how insurance is supposed to work.”

—Health economist John Goodman3

Finally and perhaps most perverse, the health insurance company expects you to keep paying your premiums even if a specified “health event” is triggered. Notice that we have been using the odd phrase “health event” not because it is standard in the field, but precisely because it sounds so foreign. In any other area of insurance, there are well-defined events that trigger a payment, and that’s why it makes perfect sense for the policyholder to no longer owe premium payments at that point. For example, if a man dies, his widow gets the death benefit check from the life insurance company, period; she isn’t expected to continue making premium payments on the policy.4

Yet this isn’t true with health insurance. If you are diagnosed with cancer and begin very expensive treatment, you will—at the bare minimum—need to keep making premium payments, in addition to whatever co-pays or deductibles you may owe. We do not mean to suggest that this is some sinister feature dreamed up by the health insurers; there are obvious differences between a one-off event (such as death or a car accident that takes the vehicle off the road) and a person receiving expensive medical treatment but still needing continuing health insurance for other possible expenses. Nonetheless, it is perverse that someone could have “good health insurance” to cover major illness, then because of that illness lose his or her ability to afford the premiums, and hence lose coverage for the continued expenses. This is particularly relevant because so many Americans have their (expensive) health insurance premiums paid directly by their employers as part of the overall compensation package—the topic of the next section.

One of the major problems with the existing health insurance market—and yet another way in which it differs from other types of insurance—is that so many Americans are reliant on their employer to provide them coverage. Indeed, during the period of 2011 to 2012, some 48 percent of Americans—almost 150 million people—received their health coverage from their employer.5 This is inherently unusual; people don’t lose their auto insurance if they get laid off.

The connection between employer and health insurance is partially responsible for the vulnerability many felt in the pre-Affordable Care Act status quo, particularly because insurance policies are not easily portable from one job to the next. If someone develops a serious condition while working for one employer, and then attempts to switch jobs, that employee would now bring a “pre-existing condition” with him or her to the new job.

The built-in turnover of health insurance policies, due to employment changes, greatly weakens the rationale of insurance in the first place. Consider for a moment what this would mean in the context of life insurance. For example, a 20-year-old breadwinner supporting a wife and two young children might take out a $1 million 30-year life insurance term policy with a fixed premium. This allows the young man to “lock in” his life insurance protection through age 50. Even if he develops a brain tumor the week after signing the contract, the young man can keep his life insurance policy in force, so long as he pays the original premium.

Now what if we tweaked this scenario and said that, for whatever reason, every three years people had to drop whatever life insurance policy they had and reapply for a new policy? In this case, our young man—and his family—would be in serious financial trouble, above and beyond the medical bills. If he should happen to survive to the third year, then at that point he would lose his existing life insurance and have to reapply. But at that point, having a brain tumor, he would be denied. (Or, if we used a less extreme example than a brain tumor, he would have to pay a much higher premium on the newly issued policy, in light of his recently diagnosed condition.) Thus we see that our hypothetical rule that forces people to drop and reapply for life insurance every three years would greatly rob life insurance of its value to society.

Something akin to our fictitious story is what happens in the real world with health insurance. People typically can’t lock in long-term coverage at contractually guaranteed fixed premiums, making these policies less like genuine insurance as we know it in other fields. There are several factors driving this outcome, but a major one is—to repeat— the fact that a huge segment of the market consists of employer-based coverage, and that employees are not allowed to take their policies with them when they change jobs.

Throughout this book, we will be breaking this particular problem down into its root causes, but here it is definitely useful to put our finger on the fact that the vast majority of Americans do not feel as if they’re really paying for their health care services. When they get a bill after a visit to the doctor’s office or (hold onto your hat) the hospital, the numbers don’t even seem real. This feeling of unreality is partly because the numbers are often outrageous and seemingly bear no relationship to the service or goods involved, but it also occurs because experience has shown that after working with the insurance company, the health care provider will end up “adjusting” the actual amount that the patient owes out of pocket. Furthermore, even after the dust settles—a process that could take months after the actual date of service— if the amount is still astronomical, then the office fully expects patient requests for lengthy installment payment plans (at 0 percent interest), and already knows the drill of how to refer a delinquent account to collections when the patient reneges on the payback plan.

Everyone who participates in this system—either on the side of suppliers or customers—knows that it’s nutty. Precisely because Americans don’t treat their doctor or hospital bills as “real” in the same way that a trip Disneyworld or a new set of tires cost “real money,” they are not as conscious about price when agreeing to a battery of tests that their physician recommends. We imagine the people in your social circle know which are the priciest steakhouses in town, and whether they are “worth it,” and they also have an idea of where to go when buying a new car. But do they have a similar feel for the pricing structure of the local hospitals or clinics? Probably not, which leads to our next section.

Because the actual consumers of health care in the United States care very little about the price at the “point of sale,” and because the providers must try to at least break even on average by dealing with huge bureaucracies using reimbursement formulas, we observe wildly divergent prices for similar procedures. For example, Table 4-1 reproduces data from Goodman’s book on the average cost of knee replacement, according to the location and type of patient:

Table 4-1. Knee Replacement Costs, Various Providers and Patients

LOCATION TYPE |

AMOUNT |

Asking Prices |

|

Hospital Gross Charge |

$60,000 - $65,000 |

What Private Insurers Pay |

|

Range (Dallas) |

$21,000 - $75,000 |

Average (Dallas) |

$32,500 |

Medicare (Dallas) |

|

What Medicare Pays |

$16,000 - $30,000 |

Cost Reported to Medicare |

$14,627 - $15,148 |

Physician Fees |

$1,400 - $1,700 |

Domestic Medical Tourism |

|

Medibid Rate (US) |

$12,000 |

Canadian Citizen US Cash Price |

$16,000 - $19,000 |

International Medical Tourism |

|

Medibid Rate (overseas) |

$7,000 - $15,000 |

Bumrungrad (Thailand) Median Price |

$14,916 |

US dog (Dallas) |

$3,700 - $5,000 |

SOURCE: John Goodman, Priceless, Table 2.1, p. 16

Indeed, the absurdity illustrated in the table is the type of phenomenon that led Goodman to title his book Priceless: he is obviously making a pun relating to the lack of market pricing in health care. The pattern in this table shows up throughout the health care system. For example, LASIK eye procedures, as well as cosmetic surgery, show historical pricing trends that look more like “normal” services than “US health care.” The reason isn’t physiological, but economical: because of insurers’ policies and relatively looser government regulations, these types of procedures have robust markets in which customers can walk into a “store” and pay cash, thus allowing all of the usual market forces of innovation and cost-cutting to operate.

In a market economy, prices serve to equalize the quantities produced by sellers and demanded by consumers. There tends to be a uniform price charged for “the same” good or service. Sellers constantly strive to deliver products of higher quality and lower price, while those who most urgently want items can bid them away from others by offering more money. If there is a temporary interruption in the supply— let’s say the influx of crude oil is halted—then the market price shoots up. This is exactly what we want to happen, as the unusually high price acts as a signal that motivates other producers to scramble into the market, while it causes consumers to economize on their purchases. As Friedrich Hayek explained, market prices act as a type of communication network by which humans rapidly transmit essential information all over the globe, so that producers and consumers can constantly tweak their plans in light of new revelations about resource supplies, technology, and customer desires.

Nobody likes high prices, but they serve a definite social function— so long as they are the correct prices, formed on a voluntary and genuine market. When the government imposes regulations that suppress prices below their market-clearing level, it’s not doing us any favors; it’s only muting a vital source of information. In the wake of a natural disaster, for example, the government will often make it illegal for gas stations to “gouge” their customers with large price increases. But this merely hinders the recovery effort, taking away the incentive for neighboring communities to ship in more gas and for local motorists to only take a few gallons at the pump. With price controls on gasoline, the quantity demanded exceeds the supply, leading to long lines at the pump and more arbitrary forms of rationing—such as selling gas only to vehicles with certain letters on their license plate.

Surprise surprise, the laws of economics work in the health care sector as much as in oil and gas. If the government implements policies that limit the price suppliers receive for medical products or services, then we will observe shortages. In 2003, the Medicare Modernization Act (MMA) adjusted the payment formulas in Medicare Part B to limit the speed at which prices could rise on drugs. The obvious rationale here was for the government to use its “buying power” to tighten the screws on those greedy pharmaceutical companies. But by taking the existing (crazy) system as it was, and slapping on arbitrary limits for how fast drug prices could rise, the government simply assured that bottlenecks would fester. Indeed, the new drug pricing rules spawned growing supply problems from the moment they took effect on January 1, 2005: the number of newly reported drug shortages skyrocketed from 74 in 2005 to 211 in 2010.

Let’s be clear what we mean: hospitals now routinely find that they simply lack generic drugs that their staff have been using for years. A June 2011 survey found that 82 percent of short-term care acute hospitals reported delaying treatment for patients because of a drug shortage, with 17 percent of all surveyed saying such an outcome occurred “frequently.” Perhaps more alarming, 35 percent of the hospitals surveyed reported that a patient had “experienced an adverse outcome” because of the shortage.6

AN ER DOCTOR REPORTS FROM THE FRONT LINES …

“In the last few years of my practice of emergency medicine, I have noted a disturbing trend: the medicines that I have found most useful, as well as the medicines that are needed for life-saving resuscitation, have been disappearing. From 1989 to about 2006 I always had at my disposal cheap medicines that were incredibly effective, as well as any medication needed to run a major resuscitation. This was particularly true for sterile injectable medications. However, beginning around 2006 I started to notice that I would order one of these medications, only to find them unavailable and ‘on national backorder.’ Initially, the shortages were infrequent and a minor nuisance. As time went by, the shortages became more and more common. The medications I relied on to manage violent or combative patients were suddenly unavailable. IV nitroglycerine for managing unstable angina or heart attacks was frequently in short supply or unavailable. Occasionally, cardiac resuscitation drugs would run out of stock in our crash carts. As it currently stands [in 2015], generic injectable sedatives, antipsychotics, and anti-nausea medications are completely unavailable. There have even been cases where my nurses and I had to hand-mix epinephrine during advanced cardiac life support. In such a situation, we have to commandeer a 1:1000 dilution used for subcutaneous allergic reactions (similar to an Epi-pen) and dilute it to the 1:10,000 dilution for IV injection. Imagine the pressure of doing this and not making a decimal point error while trying to save a dying patient! What could be the cause of all of this? My scouring of online discussions by other experts eventually led me to the government’s price controls embedded in the 2003 Medicare Modernization Act.”

—Co-author Doug McGuff

There are other ways that the implicit price controls in the US health care system manifest. For example, at least for patients dealing with the mass-market in-patient facilities (which rely almost exclusively on third-party payment), getting health care involves a lot of waiting—not only in calendar time for even routine appointments, but also sitting in various rooms for perhaps hours on end even during the officially designated appointment. This is not “how health care has to be.” Rather, it is the predictable result of price controls.

If you don’t believe us, try comparing the wait times you see in a “public” hospital emergency room setting versus a truly private outpatient medical clinic that doesn’t accept Medicare or Medicaid patients. The difference is startling—not just in terms of the structural appearance of the buildings, but also in terms of the treatment you will receive and the speediness of the visit.

One of the tragic ironies of the US government’s footprint in medical care is that on balance it doesn’t actually help the disadvantaged. It would be one thing if the government’s massive taxes, subsidies, and mandates actually created a truly egalitarian society, where the rich and politically connected had no special advantages in obtaining quality and convenient health care. Then we could have an interesting debate about what we value as a society, and whether we trumpet freedom and property rights versus safety and social equality.

Yet in practice, there is no such trade-off; we don’t have to make such hard choices. Just as the party officials in the old Soviet Union were truly members of a higher caste than the rest of their “comrades,” so too do we have a “two-tiered” (at least) system of health care in the United States, even though federal and state governments have literally spent trillions of dollars over decades in the name of providing equal opportunity for all. The solution is not to double down and try even harder to redistribute wealth or mandate “equal treatment”; theory and history show repeatedly that these attempts do not work.

We will demonstrate throughout this book that “wards of the State”—especially those on Medicaid—are helpless cogs at risk of being devoured in the US health care system. But the problem goes beyond just Medicaid patients. More generally, the sick and financially needy are left out in the cold, and their plight is exacerbated by the very government policies supposedly designed to help them.

Government reimbursement formulas and mandates (such as “community rating,” which we will study extensively in Part II) create a situation in which health insurers do not want a certain type of customer. Specifically, if you’re already sick or are likely to require expensive treatment down the road, the health insurance companies want to make it as difficult as possible for you to get one of their plans. You are a ticking time bomb and the insurance companies know that they will not be able to even “break even” on you, let alone turn a profit. Paying for your medical expenses is, to them, a cost of doing business, similar to paying corporate income taxes. They’ll do it to stay legal, but they will use every tool at their disposal to minimize the financial bleeding.

John Goodman shows how this insight explains the design of typical health insurance plans:

[T]he easiest way to overprovide to the healthy is to offer services that healthy people consume: preventive care, wellness programs, free checkups, and so on. The way to underprovide to the sick is to strictly follow evidence-based protocols and to be slow to approve expensive new drugs and other therapies. Beyond that, a health plan can underprovide to the sick and discourage their enrollment by not including the best cardiologists and the best heart treatment centers in the plan’s network, by not having the best oncologists and the best cancer treatment centers in the network, and so on.7

You may no doubt recognize the pattern Goodman has identified. However, we stress that these policies are not simply the result of greedy insurance executives screwing over the little guy. This behavior—outrageous as it is, especially for heart or cancer patients who thought they “had good insurance” and realize after being diagnosed that the best treatment in their area is “out of network”—is the unavoidable consequence of government policies that many people erroneously believe are “pro-patient.”

If you walk into a diner that has an all-you-can-eat buffet, and you want some really good eggs, you obviously order them right from the menu. You know that’s the way to get a really good serving of eggs, compared to the relative slop that they put out in the buffet. You can’t explain this difference by saying the cooks are incompetent or hate their customers, because we’re talking about the exact same cooks serving certain customers better eggs than other customers. In the case of the diner, the obvious difference is due to the pricing incentives in the buffet versus the one-off order.

The same principle carries over to health care. It makes no sense to expect hospitals, doctors, and insurance companies to provide the same quality of care to all comers regardless of payment structure. The end result is that the normal market forces of competition and innovation are crippled, resulting in massive inefficiency piled on top of the still-festering problem of the genuinely needy receiving shoddy medical care.

The state of US health care would be comical if it weren’t such a deadly serious matter. Because of the way reimbursement formulas work, patients are often asked to schedule multiple visits to see the same doctor for different conditions. Think about how ridiculous that is: if you have a few questions for your CPA or lawyer, you can schedule a phone call (or office visit) and fire away; you are either paying them a flat fee or by the hour, so they are happy to be as efficient as possible and knock all of your issues out at once. In contrast, under Medicare’s payment formula, specialists and primary care physicians typically receive either half payment or no additional payment for treating multiple conditions during the same office visit.8

Government regulations and other “best practices” standards interact with malpractice lawsuits in an insidious way. Even if a particular physician and his patient do not think a certain procedure is necessary, they may nonetheless be overruled by the hospital or insurance company, with the doctor being compelled to follow so-called “best practices.” The reason is that if the doctor does something unorthodox and then things go badly, both he and the institutions behind him are especially vulnerable to a malpractice suit.

The threat of lawsuits hangs over the entire medical profession, crippling productivity and multiplying costs. In Chapter 12, we will relay anecdotes of the perversion of safety protocols (such as “time outs” before operations) that are the understandable consequence of this litigious environment. The threat of malpractice suits explains some (but not all) of the initially shocking disparity in Table 4-1 earlier, which, if you recall, showed a human hip replacement costing up to $50,000 more than that for a dog. If something goes wrong and the dog dies, that legal liability is much lower than if the same thing happens to a human patient. To be sure, some of this makes perfect sense: it is a bigger mistake if a human dies versus a dog, and so the resulting financial compensation (if any) should be larger. Yet our point here is that the overkill in regulations and corresponding “defensive” strategies is exaggerated in the human versus dog operations as well; there are far more ways to “officially” do something wrong to a human patient.

The waste and futility of unnecessarily defensive medicine is most obvious when it comes to the widespread promotion of medical screening. Later in Chapter 13, we will assess the pros and cons of mammo-grams, colonoscopies, and PSA testing, in each case focusing on the issue as a personal decision to be made in light of the statistics.

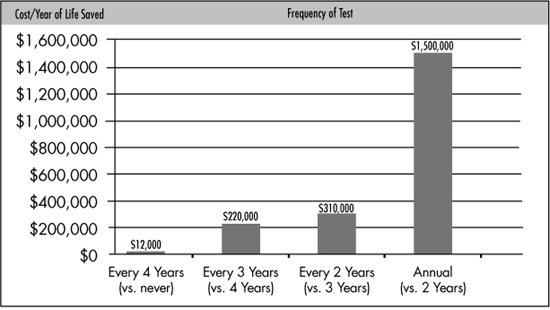

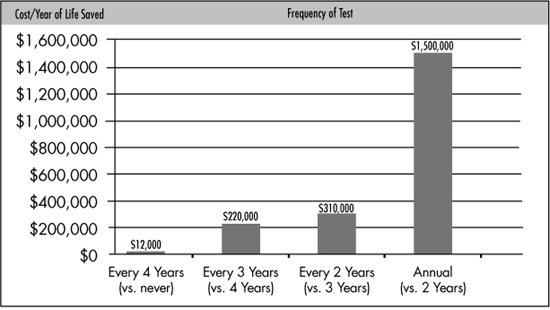

In this section, we will take the example of cervical cancer tests (Pap smears) and relate the quantifiable monetary expenses to the quantifiable benefit in terms of prolonged lifespan, as shown in Figure 4-1:

Figure 4-1. Cervical Cancer Tests: Cost per Year of Life Saved (Women Age 20)

SOURCE: John Goodman, Priceless, Figure 2.1, p. 36

Figure 4-1 contains crucial information, but we need to explain how to interpret it. The analysis, conducted in 1995 by Tammy O. Tengs, et al., estimates the marginal cost per year of life gained at various frequencies of cervical cancer testing. For example, the first column compares the two strategies of getting a cervical cancer test every four years versus never getting such a test. The first strategy costs more (you have to pay for the tests), but it leads to longer lifespans, in the statistical sense that a population of 20-year-old women who are tested once every four years will benefit from the early detection of cervical cancer—and hence will tend to live longer on average—than a population of comparable women who never get a Pap smear. When the study divided the total cost of the testing by the increase in the number of years of life, it found that the cost per year of life saved was $12,000. (Remember, the study was conducted back in 1995.) We have been liberal with our use of italics to be sure you are reading this correctly: the study didn’t find that it cost $12,000 per life saved, but rather per year gained in lifespan in the relevant population of 20-year-old women.

Now what if we increase the frequency of the cervical testing? The answer is that the cost/benefit ratio deteriorates quickly. For example, the second column in the previous chart compares the strategy of testing once every three years versus once every four years. This new strategy obviously costs more (since it involves more frequent testing), but it also enhances the benefits of early detection, leading to another incremental improvement in average lifespans among the women (in the sense we explained earlier). But when we divide the increase in cost by the increase in lifespans, we see that the marginal cost per year of life saved has skyrocketed to $220,000.

Finally, let’s skip to the last column and interpret it. When evaluating the two possible strategies of (a) administering the Pap smears on an annual basis versus (b) administering the Pap smears every other year, the study once again found that the more frequent testing would yield an increase in lifespans among the women, but only by doubling the total cost. (The women are being tested annually rather than every other year, meaning there are twice as many Pap smears to administer.) As the fourth bar in the chart shows, the study estimated that this annual approach would cost an extra $1.5 million for every additional year of life saved from early detection.

The significance of the numbers in Figure 4-1 is not so much the absolute height. For one thing, these numbers are based on older data. Another drawback is that they do not include the non-monetary but very real psychological costs of frequent cancer screening (which we will cover in Chapter 13).

Our reason for carefully walking through Figure 4-1 is to help open up your mind and pose questions about cost/benefit tradeoffs in medical decisions. Supposing the numbers in Figure 4-1 were roughly accurate, what frequency might you recommend for your 20-year-old daughter? Some readers might be tempted to say, “Annual testing— money is no object when it comes to my daughter’s health!” but that ignores reality. If cost really is irrelevant, then why not weekly or daily testing? At some point it is obvious that more frequent testing “isn’t worth it.”

No matter what you do, you will eventually die. Yet beyond this truism, there is an important economic point that many people fail to grasp: there need be nothing “irrational,” “selfish,” or “shortsighted” in eschewing expensive measures that prolong life at a very high marginal cost. For example, suppose a woman in her early 20s is a single mother who is trying to save up money for her children’s education. After reviewing the data in the prior chart, she may quite rationally, altruistically, and farsightedly decide that even getting a Pap smear every four years is not worth it, because to implicitly “spend” (in a statistical sense) $12,000 to boost her lifespan by a year is an indulgence she is not willing to make.

Our purpose in this book is not to tell readers that Pap smears are good or bad, or that they should be conducted every x numbers of years. Primarily we are trying to educate you on how to properly think through these important decisions. Unfortunately, the reimbursement, regulatory, and legal frameworks of US health care wildly over-promote medical screening, far beyond the point that makes any cost-versus-benefit sense.

It is unsurprising that end-of-life care is expensive, but the relative proportions can be shocking. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) reports that in a typical year, more than 25 percent of total Medicare payments go to the roughly 5 percent of beneficiaries who die that year. For example, in 2006, Medicare spent an average of $38,975 per Medicare recipient who passed away that year, compared to an average of $5,993 in Medicare benefits for those beneficiaries who survived the year. We can break it down even more finely: during the period of 1992 to 1999, Medicare spent an average of $6,620 in the final month of a dying beneficiary’s life, versus $325 per month for those Medicare recipients who survived.9

Something is clearly wrong with these numbers. As with our discussion of Pap smears, here too we need to think “on the margin” as good economists. The question is not whether resources should be devoted to helping elderly people prolong their lives; the relevant question is, “At what point are additional resources to extend life another month not worth it?” The question is especially poignant when, in many cases, the final months are full of misery for the patient.

The issue of end-of-life care is extremely dangerous. On the one hand, figures such as the ones we’ve just quoted scream out that “something needs to be done.” But the solution is not to let government officials decide who lives and who dies, all in the name of “protecting the taxpayer.”

The fundamental problem is that the government has assumed the responsibility of paying for the elderly’s health care, while Americans do not want to cede life and death power to that same government. The public can’t have it both ways. If they want a government strong enough to take care of them, they must be willing to endure a government with the power to kill them.

In summary we note that when it comes to end-of-life care, as with just about every other problem we’ve discussed, the thorny issues all fade away when we restore personal financial responsibility. Few people would draw up an estate plan at age 40 and say, “I am willing to reduce my bequest by $6,620 at the time of my death so that I can live to be 82 and eight months rather than 82 and seven months.” And yet, because Medicare picks up the lion’s share of the expense, this is exactly the type of outcome we get.

In Chapter 2, we studied the harmful role of the FDA in driving up drug development costs. In this section we’ll provide some more specifics to show the impact of the FDA’s requirements, particularly those regarding “Phase III clinical trials.”

People often ask how much a pharmaceutical company had to spend on research, development, and testing for a particular drug, but that can be misleading. Most drugs never make it to market. In this respect, pharmaceutical companies approach drug development the way oil companies drill wells: often they will come up dry. In both industries, the companies must make so much on the drug (or well) that “hits” that they can then cover their expenses for all of the duds.

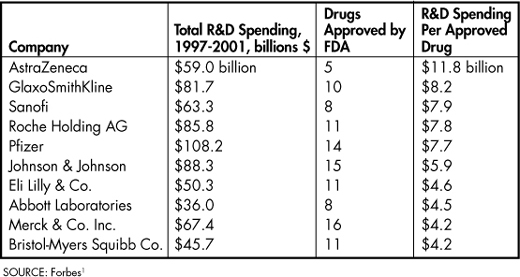

A 2012 analysis in Forbes looked at the total drug development expenses among major pharmaceutical companies over the period of 1997 to 2011, and then divided by the number of drugs actually approved by the FDA in this period. The staggering results are presented in Table 4-2:

Table 4-2. Drug Development Costs Among Major Companies, 1997-2011

As this table indicates, the expenditures to bring a new drug to market (among the companies listed) was at least $4 billion, and went nearly as high as $12 billion over the period in question. This fact alone sheds light on many of the distasteful practices of “Big Pharma.” Besides driving up prices for patients, these staggering development costs ensure that the major companies will only invest in drugs with the chance of a large market, ignoring sufferers of “niche” conditions.

We must reiterate that the explosion in drug development costs is primarily an outgrowth of FDA regulations, particularly the more onerous requirements for Phase III clinical trials (which account for about 40 percent of the total R&D spending among pharmaceutical companies). As Avik Roy explains: “From 1999 to 2005 … the average length of a clinical trial increased by 70 percent; the average number of routine procedures per trial increased by 65 percent; and the average clinical trial staff work burden increased by 67 percent.”10

Here as in other areas, there are trade-offs involved. Obviously the public would like pharmaceutical companies to engage in careful testing of their products before releasing a new drug on the market. But the explosion in cost—coupled with the poor safety record of the FDA’s oversight that we have already documented—suggest that the cost/benefit dial for drug development is extremely out of whack.

In this chapter, we’ve crystallized our historical and in-depth treatments of the first three chapters into eight takeaway problems with US health care. By this point, we have equipped you with the analytical tools and the historical knowledge to understand why the US system was in such a shambles on the eve of the Affordable Care Act (aka ObamaCare). As we will show in detail in the following Part II of the book, the situation is only going to get worse as the various provisions of the new legislation take effect.