CHAPTER 6

The Nave

The Nave

Aisles, Transepts, Roofs and Porches

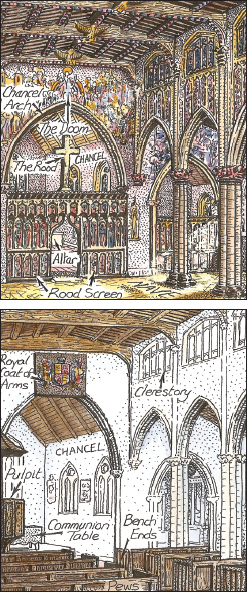

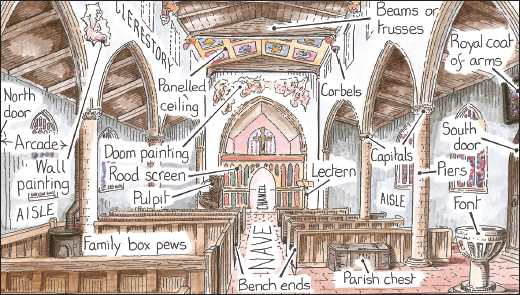

FIG 6.1: A drawing looking down the nave of a church towards the chancel at the east end with labels of some of the features you are likely to see.

THE NAVE

The nave is the main body of the church, its name derived from navis, the Latin word for ship, and it is where the congregation would stand or sit during services. As it was for the public’s use, it was generally considered their responsibility and the dating of principal building phases or lavish decoration can highlight affluent periods in the history of a parish.

The main entrance is usually by the south door but, in some, it is the north (which was used as an exit for processions in medieval times). To the west there is often a grand entrance used for special occasions, while the east end is usually divided off from the chancel by the arch and originally a screen (see Chapter 7). In the Middle Ages it was often the only large public space so it could have been used for manorial courts and fairs with stalls even erected within, while its design had to allow for the regular processions which would take place throughout the Christian calendar.

The nave is rectangular in plan with the exception of a few round ones dating from the Norman and the Georgian periods (also square and polygonal in the latter). The walls were very thick in Saxon and Norman buildings to counter the outwards thrust of the roof (see Fig 2.3), while later ones became thinner as deeper buttresses along the outer wall carried more of the load from above. The walls will usually have an outer and inner skin with rubble set in mortar in between. Timber scaffolding and hoists would have been used during construction with horizontal pieces set in the wall as it grew to hold the temporary structure firm. When it was removed upon completion the ‘putlog holes’ where the scaffolding was fixed were filled in with mortar but this often falls out later and the holes can be found today on the outer wall (especially towers).

FIG 6.2: The nave was the part on which many rich locals chose to spend their money, fitting the latest flat pitched roof and lavish decoration, while the priest and church often exhibited less enthusiasm to maintain the chancel. It is common to see a grand nave in the later Perpendicular style but with an older chancel still having a steep pitched roof, as here at Great Horwood, Bucks.

Aisles

It was common in most churches for the nave to be expanded, especially in the 13th and 14th centuries when the population reached its medieval peak, with the addition of aisles, lean-to structures along the north and south walls. When this was done the old nave wall was broken through with new arches and columns (an arcade) inserted to support the original upper part, hence it is often this latter part which may be the oldest section in the building. Aisles built in the 12th and 13th century tend to be narrow while those built in the following centuries are usually wider although many earlier ones would have been enlarged. Later, if congregations dwindled, one or both might have been abandoned, with bricked-up arches or marks on the outside wall the clues to show where they once existed (see Fig 5.4).

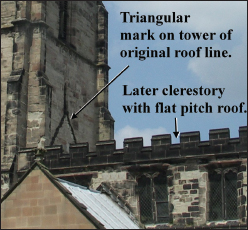

The short part of the nave wall which stands above where the aisle roof butts up is called the clerestory. When aisles were added the windows were pushed further out, making the nave darker, so to cast more light a row of small openings could be inserted along this upper section of wall. Although these may have been fitted when the aisles were built, most date from the Perpendicular period when new flatter roofs replaced older steep pitched roofs (look for a triangular mark on the tower to show where this has happened). Either the new windows replaced earlier smaller ones or they were being inserted for the first time. In the largest Norman churches the side walls of the nave could be divided further into three with a row between the arcade below and clerestory above, called a triforium (see Fig 2.27).

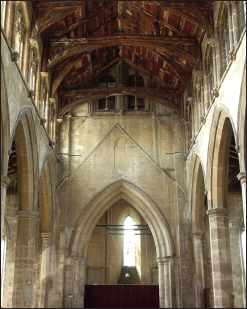

FIG 6.3: The nave progressively became lighter and more spacious from the heavy oppressive Saxon interiors (Fig 1.23) to the airy Perpendicular (Fig 3.21). This example illustrates one of the important changes, the addition of a clerestory. The arcades to each side are Early English with narrow pointed arches and characteristic double chamfers, but later the roof was raised and a set of windows inserted on either side to brighten the interior. Note the two sets of triangular marks on the wall of the tower in the back showing the line of earlier roofs and the original belfry openings now within the nave.

Transepts

Larger churches could also benefit from the addition of transepts to the north and south of the tower which created a crucifix church plan. These were and still are used as chapels, with additional altars provided for the clergy or private individuals, and often contain family memorials and tombs (see Chapter 7). They were usually built in conjunction with a central tower (especially in the 12th and 13th centuries), their bulk in effect buttressing the structure, although sometimes this has either collapsed, been replaced by a west tower or one was planned but never built. The space under a central tower where the nave, transepts and chancel all met is called the crossing.

FIG 6.4: A close up of the tower and the end of the nave where a clerestory and flatter roof have replaced an earlier steep pitched roof, the line of which is still visible above the battlements. Clerestories were very popular in eastern counties, less so in the far South-West.

Roofs

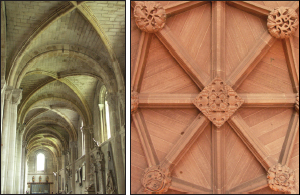

The roof of the nave, as with the other parts of the building, was a crucial design feature and spanning such a large space in medieval times pushed masons’ and carpenters’ skills to the limit. In a few large churches the ceiling can be stone vaulted with the outer tiled or lead-covered roof above and a separate inner skin (the vault), which you see from inside with a hidden gap between the two. This vaulting was formed over temporary wooden centering erected within the church and its earliest form was simply a semicircular covering known as a barrel or tunnel vault. Where two lengths met at right angles there was formed a diagonal cross shape. It was soon realized that if ribs were run along these joints, transferring the load down to the walls, then the vaulting between could be much thinner, making construction cheaper and easier (Fig 6.5.). This simplest form of rib vaulting which appeared in the Late Norman period was further elaborated upon over the centuries with additional, mainly decorative pieces in between to create complex patterns. The final most ambitious form was fan vaulting (Fig 3.12), with numerous ribs flowering from high in the wall and intricate stonework between forming its distinctive fan shape. Vaulting is rare in the nave of a church, except in old abbey churches which were adopted by the parish after the Dissolution; however, it can be found in smaller spaces like an aisle, chapel or in a porch.

Most parish churches have a wooden roof so you see the underside of the supporting timbers from inside the nave or an inserted ceiling hiding it from view. Steep pitched roofs were held in place by a series of trusses, triangular arrangements formed from two diagonal rafters with a horizontal beam either at the bottom (tie beam) or higher up (collar beam). Early examples often used a central vertical king post running up to the ridge piece or a shorter crown post as part of the structure.

FIG 6.5: A simple groin vault with ribs along a side aisle of an old priory church (left) and a close up of a later rib vault with diagonals linked by thinner liernes (right). The decorative bosses added at intersections were a weight designed to hold the ribs down and stop them from rising. In fan vaulting the ribs are not structural but carved out of slabs.

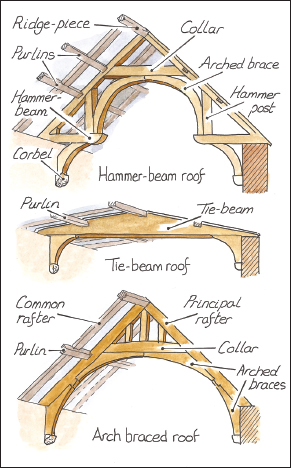

FIG 6.6: Later medieval types of roof which you are likely still to see today (some may be more modern replicas). Hammer beams were popular in the east of the country, arch braces and tie beams are generally more widespread. There is much regional variation and period detailing in roofing, of which these are but the crudest simplification.

As most churches have been re-roofed since construction, they are more likely to have a later type which had prominent longitudinal purlins and common and principal rafters to form types known as double framed. These could either have a large tie beam with just its top edge or its whole length cambered to match the flat pitch of the covering, or an arched brace which curves to match a steeper one, both types being supported by stone brackets (corbels) below where they meet the wall. A hammer-beam roof is an ingenious arrangement in which a short horizontal timber projects out from the wall a short way and upon its end an arched brace springs up to a collar, permitting a larger width to be spanned without blocking the view to the east window.

FIG 6.7: Tie-beam roofs with decorative stone corbels and wooden angels (left) and carved bosses (right).

These later roofs could be embellished with carved angels and decorative bosses, while the gaps between rafters could be boarded or plastered, sometimes just a short section over where the rood screen stood at the front of the chancel. A distinctive type popular in the West Country is the waggon roof, in which the gap between the underside of arched braces is panelled in to form the appearance from inside the church of the canvas covering of an old waggon.

Porch and Door

The porch which sheltered the main entrance into the nave (hence usually on the south side) was more than just somewhere to keep out of the rain. It was used as part of the baptism and marriage services. It was where local business deals could be sealed and notices pinned relating to manorial courts which could be held within the church. The door acted as a sanctuary for those evading the law by holding the ring upon it, a right which was not completely revoked until 1621.

The earliest types of porch tend to project only a short way off the wall and many churches either did not have one or just erected a simple timber structure which has since been replaced. By the 14th and 15th century they became a popular new addition, bequeathed to the church by a wealthy local and displaying lavish decoration, with sometimes a room above which was used by the clergy and also served as a school, armoury or a library in some cases.

The structure itself reflected contemporary style with the arched entrance and decoration datable from the details illustrated in previous chapters. Timber ones which were popular in the South-East are trickier to date and many were built or restored in the past few hundred years.

The doorway which it covers will often be older than the porch, and many have an elaborate Norman tympanum above from when the entrance was open to the elements (see Fig 1.9). The reassuringly heavy creaking door may itself be of antiquity with some decorative ironwork surviving from the 12th and 13th centuries (although the wood may have been renewed) and many more may be from the 14th and 15th centuries when it was fashionable to have it divided into long thin panels with tracery at the top.

FIG 6.8: A Perpendicular two-storey porch with a small room above, which could have been used as accommodation for a priest, a school room or library, or for holding arms.

FIG 6.9: A late medieval door from Ashwell, Herts, which still has its fittings including a sanctuary ring on its outer face (left) and the grid of timber strengthening it on its inner face (right). In some there may still be a stoup on the right-hand side of the entrance which originally held holy water for worshippers to bless themselves with before entering.

THE NAVE IN DETAIL

Decoration

One of the most surprising aspects of churches is that they were originally a riot of colour. It was only in the hundred years after the Reformation that whitewashing, neglect and destruction removed most traces of medieval decoration. The outside of the building could have been rendered and painted or whitewashed with window tracery picked out in bolder colours. Within the nave most of the wall surface would have been covered with images of saints and stories from the Bible, warning the illiterate congregation of what would happen to them if they blasphemed. Columns and capitals would have been painted, the ceiling and roof trusses too, often with decorative detail picked out in gilt. It was restoration mainly in the 20th century which has uncovered what remains of this and it is not unusual to find fragments left exposed in many churches.

FIG 6.10: It is common to find scratched marks around the entrance to a church. A small hole on the outer face with radiating lines is a scratch dial and originally a wooden stick would be set in the middle to act as a sundial, often with a deeper mark indicating the time for mass. Other markings include crosses carved by someone as proof of making a vow, mason’s marks or even medieval graffiti.

FIG 6.11: The nave was a riot of colour, covered with wall paintings conveying messages to an illiterate congregation before the Reformation (top). By the late 17th century the same nave is whitewashed with a pulpit, pews and a Royal Coat of Arms in place of the doom (bottom).

FIG 6.12: The interior of St Mary’s, a small Norman church at Kempley, Glos, has one of the finest displays of medieval wall paintings including the wheel of life (left) and a doom (above the chancel arch). The latter was the most significant painting in a church and it formed a background to the great rood which originally hung or stood in front of it. Most had Christ showing his wounds with Hell on one side and Heaven on the other.

FIG 6.13: St Agatha’s church next to the remains of Easby Abbey, North Yorks, has wall paintings dating from the 13th century as in this example showing the Expulsion from the Garden. Other popular images in medieval churches were St George, St Margaret and St Catherine, and the seven deadly sins. St Christopher carrying Christ over the river was probably the most frequent and was often found opposite the main entrance.

The floor in most churches would have originally been no more than beaten earth, usually hardened with a substance like animal’s blood and then sprinkled over with rushes or grass (which would be regularly swept out and replaced). The finest may have had stone flags although these were usually fitted in more recent centuries. Medieval tiles were a luxury product reserved for the area around the altar and they would usually have a patterned surface finished in red and yellow. The Victorians copied these and when renovating or fitting heating pipes under the floor they covered the old surface with plain red tiles and patterned ones in the chancel. It is these later machine made tiles or stone flags that you will find in most churches today.

Fonts

The first feature you are likely to come across upon entering the nave is the font, the receptacle for holding holy water. This was considered of such value in the medieval period that most had a lockable cover to prevent theft, which sometimes could be tall, elaborately carved conical pieces raised and lowered by chains. Because of this importance and the fact it can be moved, the font is one item which was retained when the church was rebuilt and hence they are often of great antiquity.

There is great regional variation in the design of fonts but there are some general features which help date them in addition to the style of decoration (see Chapters 1–5). Just a few survive from the Saxon period but more than a thousand can be found from Norman times. These have large bowls (as baptism involved immersion of the whole baby at this date), are usually square or circular and are often decorated with mystical beasts and figures. In the late 12th century some were produced with a chalice-shaped bowl raised on four columns in each corner (Fig 6.14, left). By the 14th century octagonal ones with niches and sometimes tracery patterns had become popular (FIG 6.14, centre). In the following century they were often set upon steps (though many have been raised up like this in more recent centuries).

FIG 6.14: A late Norman font with its characteristic large bowl (left), one from the early 14th century with cusped tracery and crockets as in Decorated churches at the time (centre) and a 15th-century example with coats of arms and square flowers distinctive of the Perpendicular style (right). Originally fonts would have been painted in bright colours like the interior of the church, and occasionally fragments can be found. Some medieval fonts were made from lead, but these have later been destroyed, some even used to make musket balls in the Civil War.

FIG 6.15: Another feature often found around the west end of the church is the parish chest, a lockable wooden type in which originally would have been kept valuables. Most had three locks with the vicar having one key and churchwardens the others. The earliest could simply be a roughly squared log with the top cut off to form a lid. The late medieval ones, which are still quite numerous, are made from slabs of wood bound together by ironwork; some from the 15th century have the short end extended down to raise it off the damp floor. This example from Whitby was stolen in the 18th century and thrown over the nearby cliffs and although it survived it was found empty.

Gallery

A raised floor of wooden seating supported on columns which first appeared in churches when the rood lofts, part of the screen across the chancel where musicians could play from, were destroyed after the Reformation. To replace them small galleries were inserted at the west end or within the tower from which they could play. Later, as the population grew, wooden galleries were inserted within the medieval nave, some just at the west end, others on all three sides facing the pulpit. These have often been stripped out in more recent times but are still common in Georgian churches and later chapels where they were part of the original structure.

FIG 6.16: Galleries were a popular addition, especially in the 18th century when extra seating was needed for a growing congregation. As in this example from Whitby, they were often clumsily inserted covering windows and drowning out the medieval features. Note the top of the triple-decker pulpit (right) with a sounding board above.

Coat of Arms

A common feature in the nave is a large board hung on the wall (now often found above the south doorway) with a coat of arms painted upon it. One type is a hatchment, a diamond or lozenge-shaped frame usually with the word Resurgam below the coat of arms, meaning ‘I will rise again’. These were boards which were hung for a couple of months in front of the house of the deceased and surviving examples usually date from the late 17th or early 18th centuries. Their layout and colour of background also identified the deceased’s marital status.

FIG 6.17: An example of a Royal Coat of Arms with the initials of Charles I dating it to 1625-49. The countries represented within the quarters also changed over time and can help dating. In the 17th century England was top left, the fleur-de-lys of France bottom right (or they share both quarters as above), with Scotland top right and the harp of Ireland bottom left. With the Union of England and Scotland in 1707 their arms share both the top left and bottom right quarters and then the dropping of the claim to the French throne meant from 1801 that England was in two and Scotland and Ireland the others.

The other type is the Royal Coat of Arms, which was originally hung above the chancel arch after the Reformation. They became common in Elizabeth I’s reign but most surviving examples date from after the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660 and then have usually been moved to a less prominent position in the Victorian period. They will normally have the initials of the monarch on them but they can also be dated from the subtle changes to the Royal Coat of Arms over the centuries. For instance, a gold lion in the centre, introduced by William of Orange, dates one painted between 1689 and 1702, and the white horse of Hanover in a similar position dates from the Georgian period. The Tudors also had the Welsh dragon as one of the supporters but this was changed to the familiar unicorn by James I. It was also common for an older coat of arms to be updated, so in the 18th century the initial of the king could be changed from a ‘C’ to a ‘G’ and the white horse simply added in the middle.

Benches and Pews

It was rare to find seating in the nave during the Middle Ages. Most stood or knelt during the service, which being held out of view behind the screen permitted people to come and go without disturbing the clergy. A stone plinth was often provided around the wall for the elderly or infirm, from which we get the phrase ‘gone to the wall’. In the late medieval period as the idea of a sermon being preached directly to the congregation gained importance so benches became more common, and then after the Reformation with the priest turning round to face them, seating became a standard fitting. At the same time the loss of the chantry chapels meant the wealthy families wanted somewhere private to sit, so family pews were created (sometimes within the old chantry chapel). They could have a canopy above and some their own fireplace, while a convenient exit back to the manor house to avoid the rush to leave was essential!

FIG 6.18: The boards at the end of the benches were often carved, some highly decoratively as in the above example. Poppy heads at the top were popular in East Anglia (derived from the figurehead of a ship, the ‘puppis’, and not the flower); square headed ones were the norm in Somerset, and linenfold patterns were carved in the centre of Tudor examples.

FIG 6.19: Box pews were a common addition in the 17th and 18th centuries, some just reserved for the wealthy, others more generally spread around the nave as in this example from York.

Pulpits

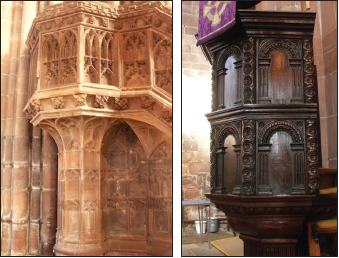

As the sermon gained importance, a pulpit from which it could be preached would be provided and there are a small number of late medieval survivors in wood and stone, usually with a distinctive slender stem beneath. Far more survive from the early 17th century as they became a standard fitting and these have distinctive rich wooden carving with semi-circular arched decoration and sometimes a sounding board above. In the late 17th and early 18th centuries a triple-decker with the pulpit, a lectern and prayer desk all in one was popular (see Fig 6.16).

FIG 6.20: A stone medieval pulpit with a slim stem (left) and a Jacobean pulpit (early 17th-century) with distinctive round arch decoration (right) both from Nantwich, Cheshire. Some still have a bracket fixed to them from which an hour glass was hung to regulate the time of the sermon.

The lectern was usually a freestanding piece originally sited in the chancel before being moved to the front of the nave after the Reformation. Some are wood, others brass, often with the top in the shape of an eagle with outstretched wings (the symbol of St John the Evangelist) and around 50 or 60 originals survive from the 15th and 16th centuries.

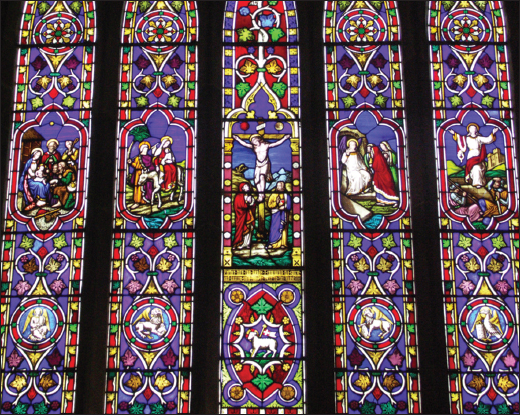

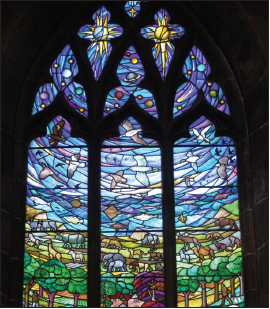

Stained Glass

No feature of the church is so immediately recognizable as stained glass windows and few can fail to be moved by their stunning displays of colour as the sun pours in behind them (it is more correct to call them painted glass). Most today are Victorian as medieval ones were smashed out and replaced by clear glass in the century after the Reformation. A few early examples did survive and many others were refitted when the church was restored, albeit in a jumble of fragments set in a single opening (Fig 6.21).

Glass was a luxury during the medieval period and most early churches would have had shutters or oiled cloth across windows with tracery and leaded panes only becoming common in the late 13th century. The patterns were marked out on a board and pieces of coloured glass cut to fit with lead strips between holding them in place and wires attaching these to bars fixed into the window frame to prevent wind damage (Fig 6.21, bottom). These early types used rich reds and blues with yellow stain being introduced in the 14th century (figures of this date also have a slightly ‘S’-shaped stance). Details like faces could be added by black stain and shading with tones of brown, both being fired to fix them to the glass.

The height of medieval stained glass came in the 15th century, with the rectangular panels created by the Perpendicular tracery giving a more convenient space for elaborate designs. Three-dimensional richly coloured pictures, often with heraldic symbols, were popular with the red, blue, green and yellows being broken up by clear white pieces. Victorian stained glass is distinctive because of this lack of clear glass, it seems darker with much use of blue and red, while the figures on closer inspection match those of contemporary paintings.

FIG 6.21: Examples of medieval stained glass. These windows were destroyed in the years after the Reformation and have been restored but with some fragments which could not make a complete image inserted in an abstract manner, as can be seen in the detail above the figures in each picture. Note the horizontal support bar with rings of wire (bottom) which stop the glass from being blown out.

FIG 6.22: Most stained glass windows are Victorian (top) and tend to contain a lot of blue and red as opposed to medieval ones which used more clear glass (medieval glass tends to look silvery from the outside). Recent examples are usually more daring and like this example (right) use the window as a whole, ignoring the tracery divisions.