CHAPTER 7

The chancel

The chancel

Altars, Chapels and Memorials

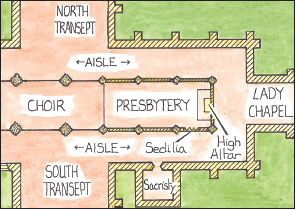

FIG 7.1: Drawing showing the inside of a chancel with labels of some of the features you will find there

As the nave was the responsibility of the congregation, so the chancel was that of the clergy. It was the area in a medieval church where the service took place with the altar as its centrepiece and a rood screen at its west end enclosing it from view. This perpetuated the great mystery of the mass to the public back in the nave, enhanced further by it being chanted in Latin. As it was maintained by a priest who was often little better off than the congregation it usually relied upon the finances of the mother church or monastery for any building work. It is often the case that after its initial build the chancel would receive just enough for basic repairs and have a modest appearance compared with some of the splendours lavished by the public upon the nave, until the Victorians restored the balance.

Most Norman and occasionally Saxon churches originally had an apse (see Fig 1.22), typically a short semicircular extension to the east end of the chancel, in which senior members of the clergy could sit during a service. In the same period there may have also been a crypt below the altar in which relics were housed, with a passage called an ambulatory around the outside for pilgrims to access or view them.

FIG 7.2: The Saxon crypt at Repton, Derbys, dating from the 8th century (rebuilt in the 9th), under the chancel in which the remains of nobles and relics would have been housed. Such was the demand to see these venerated remnants or artifacts that many of the latter were manufactured until the authorities curbed the practice in the 13th century. Pilgrimages to visit these holy sites were huge undertakings and reached a fever pitch from the 12th to 14th centuries, such that relics were placed in side chapels to avoid disruption to services.

By the 13th century the altar had moved closer to the east wall and the clergy and officials now sat to the side of it while the priest had his back to the nave during services. The chancel now became square ended (although those founded by the Celtic church had long been so) with a decorative altarpiece on the east wall. Additional altars were provided for relics, private individuals or guilds either at the east end of aisles or in purpose-built chapels to the side of the chancel. In the 14th and 15th centuries these were frequently built by wealthy locals who would pay for the building and for a priest to chant mass to his memory and are hence known as chantry chapels. Those dedicated to the Virgin Mary are referred to as Lady Chapels (see Fig 3.14).

FIG 7.3: In many churches a section at the east end of an aisle or an additional building to the side (as here at St Mary’s, Warwick) was provided to form a chantry chapel in which mass was chanted to the memory of the deceased who had paid for it. Sometimes the endowment left was not sufficient to cover a full permanent chantry due to inflation especially after the Black Death, so either they got a reduced amount of chanting or it stopped altogether.

FIG 7.4: In some of the largest churches (and cathedrals and abbeys) the layout of the chancel was more elaborate with a choir extending west under a crossing tower (where there was one) and a sanctuary containing the altar and a reredos (wooden or stone decorative screen). The aisles (often referred to as an ambulatory) ran around the outer edge of this area with side chapels leading off it and often an altar dedicated to the Virgin Mary at the east end (this area is then referred to as the Lady Chapel).

With the Reformation this all changed. The new Church created under Henry VIII had an English Bible with the priest conducting services from a pulpit. Over the following century the rood screens were removed, new wooden communion tables were provided in place of stone altars, walls were whitewashed and windows filled with clear glass. It was the Victorians who concentrated much of their restorative energies upon returning the chancel to their interpretation of its former glory, rebuilding the structure and decorating it with the rich colours we so often see today (see Fig 5.20).

FIG 7.5: A rectangular opening at an angle through a wall is called a squint, which allowed someone from the side of the chancel arch or transept to watch the service behind the screen. It was often used by the person who had to ring the Sanctus bell at various points during the service, and these can sometimes be seen on the roof above the east end of the nave (see Fig 3.17). Squints will line up with the altar (as in this example from Burford, Oxon) and can be interesting where they don’t, as this implies the chancel has been later extended and the altar re-sited further east.

Chancel Arch and Rood Screens

The division between the nave and chancel is marked by the chancel arch and where they still survive (or replicas were installed) by the rood screen. The arch carries the load of the wall between the two parts and the size of the opening grew over time as technology permitted. Saxon ones tend to be narrow (see Fig 1.23), the Normans were more adventurous with the semi-circular arch, enhancing it with bands of decoration (see Fig 1.24), while later the pointed arch permitted it to become larger with the attention focusing more upon the screen below (see Fig 3.21).

The rood screen was a wooden or occasionally stone wall with a central opening or door over which was suspended a large crucifix (the rood). The finest were brightly painted with tracery or cusps in the pointed arched openings and decorated panels below, some with a loft along the top from which musicians could play (the steps up to this in the wall often survive when the screen does not). Others were simpler in design, especially away from the rich wool areas, either running just across the end of the nave or in the South-West over the end of the aisles as well.

FIG 7.6: A 15th-century painted screen from Felmersham, Beds showing some of the bright colours in which it, along with most of the interior, would have been painted before the Reformation.

Above this, resting on the loft or a separate beam, was the great rood, a large crucifix with carvings of St Mary and St John either side. Some were of such size that they covered part of the doom painting above the chancel arch and the gaps where they once stood can still be found on the wall. A canopy of honour or rood celure was a section of the nave ceiling above this, which was decorated to highlight its importance. The rood was one of the first parts to go after the Reformation and as the interior was opened out for the new services the screen often followed suit. The doom was then whitewashed and a Royal Coat of Arms, Ten Commandments or Lord’s Prayer was painted or hung over it.

FIG 7.7: In Devon and other parts of the South-West the rood screen continued as one whole piece across the nave and aisles as here at Stoke in Hartland. In some churches, especially those off the beaten track, many of the medieval features survived, either missed by commissioners or saved by more sympathetic clergy.

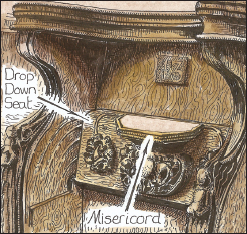

Stalls and Misericords

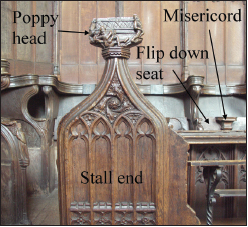

Directly behind the screen in many larger or collegiate churches would have been wooden stalls, a single or double row either side. Medieval ones were built for members of the clergy and patrons and had flip-down seats with a projection on their underside called a misericord. This allowed the person standing in front to rest during long services and most were decorated with symbolic or satirical carvings. The modern use of these stalls for choirs was introduced by the Victorians and they either reused existing ones or built new, copying original work to such a degree that the difference is hard to tell apart from general wear and tear.

FIG 7.8: A detail of stalls from the collegiate church at Tong, Shropshire.

Music was an important element in the medieval church and by the end of the period most had some form of simple organ, often positioned on the rood loft. A Sanctus bell was a small hand-held type which was rung at set points during mass; the person doing so might have been sitting in the nave or transept so a squint may have been cut so he could see what was going on at the altar (see Fig 7.5). Some were also hung on the roof above the east end of the nave (see Fig 3.17). Puritanical dislike for joy in services meant most instruments were removed and the organ only began to reappear in the chancel after the Restoration, notably in Wren’s churches, with those in use today mainly dating from the Victorian or modern period.

FIG 7.9: Misericords are wonderful details to study as they are one of the rare places where the medieval craftsman was free to express himself. Figures carved include birds, beasts and fishes, and themes like mythology, medieval romances (Reynard the fox was popular), domestic life and sports are frequently found. Fictional characters, monks, doctors and musicians, were also satirised. Considering the importance of those who rested upon them, it is surprising that sacred subjects are rare.

Piscina and Sedilia

Adjacent to the altar in a medieval church was a small stone basin, usually set in the south wall, called a piscina (Latin for basin or fishpond). This was used for washing the sacred vessels after the service and drained into the consecrated ground outside. Those fitted in Edward I’s reign, 1272–1307, tend to have two bowls, the additional one for pouring down the ablutions from the chalice. Piscina found outside of the chancel can indicate where an additional altar was in medieval times.

Usually found next to this is a sedilia (from sedile, the Latin for seat), a set of three seats built into the south wall often with a decorated canopy above in the contemporary style. The priest would have sat on the eastern seat (often signified by being higher) while his deacon and sub deacon would sit on the others during the parts of the service which were sung.

FIG 7.10: A piscina with an aumbry (recessed cupboard) used for storing cruets, i.e. jugs containing water and wine used in the services, and a small bowl for washing the priest’s fingers. Some of the early piscina were supported upon a stone bracket or rested on a column as in this example, while others were built as part of the sedilia (see Fig 7.11).

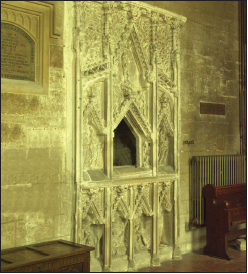

On the north side there is sometimes a wooden sanctuary chair used for visiting bishops. There may also be an Easter sepulchre where the Blessed Sacrament was placed from Good Friday to the Sunday. Most were temporary but a few stone ones survive, usually from the 14th century. Rectangular holes in the wall of the chancel are old aumbries, medieval cupboards which originally had doors across the front and contained the altar plate.

FIG 7.11: A sedilia with its characteristic three openings and a smaller piscina to the left. These examples were built with the seats on the same level, others may have them stepped. The canopy and decoration around sedilia and piscinas can help date them, ogee arches with cusps below and crockets above mean these examples are probably from the 15th century.

In most medieval churches the priest would come into the church via his own door to the side of the chancel, ready dressed and with all the components required for the service present. In the largest churches a separate sacristy may have been built in which vestments and vessels would have been stored with a private altar for the priest. In the Church of England these side rooms are referred to as a vestry and most either were built in the Victorian period or were converted from pre-Reformation chantry chapels. Where these do not exist today, the vicar has to make do with a curtained-off part of the aisle or under the tower!

FIG 7.12: An elaborate Easter sepulchre from Heckington, Lincs.

Altars, Communion Table and Reredos

The high altar (to differentiate it from the others which were sited in side chapels) was the centre point of the church, being the place where holy relics were originally contained. Medieval stone types had a slab on top (the mensa) with four crosses in each corner and a fifth in the middle and this part may survive even when the base below is of a later date. The roof above may have been decorated to emphasise its importance, sometimes with hooks in the ceiling from where Lent veils would have been hung. After the Reformation, communion tables were provided, many from the late 16th and early 17th century with distinctive bulbous legs.

FIG 7.13: The chancel of St Botolph’s church, Boston, Lincs, with its reredos dating from the 1890s running the full width of the wall. Where they are older, the statues are usually Victorian replacements for the originals destroyed after the Reformation. Above is the east window, usually the most impressive in the building. Some have niches either side, with the one on the north side usually for the patron saint of the church.

In most medieval churches, on the wall under the east window would have been an altarpiece, a painting either directly on the wall or on panels. In some a more elaborate reredos, a larger screen in stone (alabaster was popular in the medieval period and white marble in the Victorian) or wood was fitted with carved figures (these are usually modern replacements for those removed after the Reformation). To the front of the altar a railing runs from one side of the chancel to the other. These altar rails began to be fitted after the Reformation when it was found that without the rood screen the altar was too open and even dogs had to be kept out. Many rails date from the Jacobean period when they were fixed to discourage Puritans from moving the altar west into the body of the church.

Internal Memorials

One of the aspects which brings a church to life is the memorials to the dead. Their names, ambitions, standing in society, even humour, can speak to us hundreds of years on through the design and epitaph on their grave slabs, wall plaques and tombs. Although many can be found within the nave it was the chancel, and more precisely the altar, which people would vie with each other to get closest to and it was only the wealthiest and most important members of the community who would be interred here.

Most memorials you find inside a church today will date from the 18th century when the middle classes clamoured to join the ranks of their superiors. This did not end until, due to the obvious health risk and unpleasant odour from having decomposing bodies a few inches from where daily services were held, legislation to ban internal burials was passed in the 1840s. The well off in the parish now had to be buried outside, either in the churchyard or in the new urban cemeteries where they had a free rein to build themselves spectacular tombs to display their standing in society.

Tombs

The Saxons rarely approved internal burials and in the 11th and even 12th centuries it was usually only the clergy who were permitted to be buried in the church. This would have been in a stone coffin set in the floor with a grave slab over it, but would have been a temporary resting place as the body was removed after a short while to a charnel house (a room, underground chamber or small building outside) and the coffin reused for someone else.

FIG 7.14: Medieval grave slabs from Bakewell, Derbys. Earlier types tend to have a simple cross on top while on later ones they become more decorative with a stepped base as in these examples. There are no inscriptions as they were reused for other burials.

FIG 7.15: Medieval stone coffins from Bakewell, Derbys. These are more correctly termed a sarcophagus as they had a hole in the bottom for the fluids from the decomposing body to escape.

During the late 13th century permanent memorials to members of the wealthy local families began to appear in the form of tombs, a grave slab raised on a tall plinth with an effigy laid upon the top. The earliest effigies were roughly carved in wood or stone and covered in gesso (a chalky paste-like plaster of paris) in which was shaped the body’s details. They were not representations of the deceased as accurate portraiture only developed in the 14th century. By this time stone and especially alabaster (a soft marble-like material, often with an orange or red vein) were used for the complete carving, with the whole piece then painted (fragments of this can still be found if you look closely on some tombs). These could either be on a freestanding tomb in the chancel or in a family chapel to one side, while some were recessed into the wall of the church with a canopy above.

FIG 7.16: A tomb with an alabaster effigy dating from the 15th century in Ashbourne church, Derbys. The pose of the effigy changed through time and along with the fashionable clothing and armour can help date these memorials. Knights with their hand upon their sword looking like they are ready to leap into action were popular from the late 13th to mid 14th century, then lying flat on their back with arms crossed until the turn of the 15th century when the hands were placed together in prayer and fashionable clothing as well as armour was common. It was also usual from this date for them to be shown next to an effigy of their wife, as in this example.

Brasses

If you could not afford such a splendid memorial then a large brass plate set into a slab in the floor was the next best thing. Popular with the lesser gentry, merchants and professional classes, especially in the eastern counties, they were an alloy of tin and copper called latten (but known now as brass) and were cut into an impression of the profile of the deceased and an epitaph engraved.

FIG 7.17: A 15th-century canopied tomb. The shape of the arch and the decoration around it as well as the style of the effigy can help date these. By the time this example was carved it was common to have shields with coats of arms along the sides of the tomb.

FIG 7.18: An alarming sight to modern eyes is a type of tomb which developed after the Black Death and through into the 16th century in which the space below the effigy was hollow and through its open sides can be seen the carving of a skeleton (cadaver), a humbling realization by the rich that they shared the same fate as the poor.

The earliest date from the late 13th century when they tend to be large with deeply cut engraving, figures often in chain armour, with hair which curled up at the ends, some knights having crossed legs and the text in French. Examples from the late 14th and 15th centuries wear contemporary clothing or plate armour, their hair usually straight (as in Fig 7.19), and the text in Latin and only later in English (the medieval clergy always used Latin on their memorials). The size gets smaller towards the end of the medieval period and the quality of engraving drops with heavily shadowed stiff figures. Despite this it remained a popular form of memorial into the later Tudor period although many of these may have been reused with an earlier engraving on the rear.

FIG 7.19: Brasses are a useful source of information about the late medieval period as text is lacking or has worn away on other forms of memorial. Only a fraction of the original number survive as they were often ripped up around the time of the Civil War but the stone with the recess where they once were fixed is still clear in the floor of many churches.

Monuments, Wall Plaques and Tombs

In the wake of the Reformation the wealthy directed their money away from the church, with the exception of memorials which could become monumental in size. In the later 16th and early 17th centuries some took the form either of a freestanding chest tomb with weepers (figures carved crying for the deceased) or coats of arms around the edge. Some were set onto a wall with husband and wife kneeling, while facing each other, and their children beneath them in a similar pose (those holding a skull having died before their parents). Others are rather flash figures resting their heads upon an elbow and dressed in the latest fashions.

From the late 17th century figures are increasingly found standing in classical dress, some even going to the extent of posing as Roman emperors. These reached a peak in the 18th century when white and black marble monuments (the painting of memorials in bright colours ends around this time), with huge figures dressed in robes and wigs and classical details on the front, dominated even the most humble country church.

Now farmers and professionals vied with the gentry and merchants to try and get buried within the building, usually with a wall plaque or a ledger, an inscribed stone slab set into the floor. In many churches the walls and floors became overwhelmed by memorials and the Victorians not only brought the practice to an end but also removed them as part of restoration.

FIG 7.20: An early 17th-century tomb from Ashbourne, Derbys. As well as contemporary dress, fashionable architectural details can help date the memorials where dates are illegible. Here the geometric patterns up the sides, formed out of flat bands called strapwork, tend to date from the 1580s to 1620s.

FIG 7.21: A rather ostentatious monument dating from the mid-18th century with the deceased dressed as a Roman emperor on the left of the Norman arch and a more subdued wall plaque of Greek inspiration from the early 19th century.

FIG 7.22: An 18th-century wall memorial which must have been disturbing for the congregation, with such a stern figure staring down at them during services!