Colonialism, racism and African resistance

It is surprising for many students that most of the African continent was under European control for less than a seventy-year period and that the Congress of Berlin which initiated this took place just over 120 years ago. Yet in this relatively short period, massive changes took place on the continent that not only established the immediate context of African politics, but also continue to constrain and shape its future to this day. The purpose of this chapter is not to detail Africa’s colonial history or indeed its many legacies, but to outline some of the debates around each, which have relevance for our understanding of Africa today. We need to consider the explanations of the ‘scramble’ and of the colonization that followed the Congress of Berlin in 1884 within the context of ideology, commerce, resistance and liberation. In so doing, the chapter will highlight two things: impact and continuity. It draws obvious attention to the impact of the years of imperial rule, but the chapter also assumes an element of continuity, a degree of initiative and autonomy, on the part of those subject to foreign rule. Importantly, both forces – impact and continuity – established the environment for politics of the new state at the time of independence – the subject of the next chapter.

The scramble for Africa

Colonialism is a general term signifying domination and hegemony, classically in the form of political rule and economic control on the part of a European state over territories and peoples outside Europe. The earliest forms of colonialism in this sense (not all empires were colonial empires) were exhibited in the New World by Spain and Portugal, although classical colonialism flowered later only in conjunction with the rise of global capitalism, manifested in the rule by European states over various polities in Asia and Africa. Imperialism as a term is sometimes seen as interchangeable with colonialism, even as it has often been used to focus on the economic, and specifically capitalist, character of colonial rule. Colonialism itself has sometimes been reserved for cases of settler colonialism, where segments of the dominant population not only rule over, but settle in, colonial territories. However, most scholars agree that colonialism was in fact a form of rule that was most often not accompanied by European settlement, and that the term ‘colonialism’ entails sustained control over a local population by states that were interested in neither settlement nor assimilation.

Allied to both colonialism and imperialism was the notion of enlightenment; more precisely, discovery and reason. Reason gave discovery a justification and a new meaning, but it also took its expanding global laboratory for granted. Science flourished in the eighteenth century not merely because of the intense curiosity of individuals working in Europe, but because colonial expansion both necessitated and facilitated the active exercise of the scientific imagination. It was through discovery – the seeking, surveying, mapping, naming and ultimately possessing – of new regions that science itself could open new territories of conquest, among them cartography, geography, botany, philology and anthropology. As the world was literally shaped for Europe through cartography – which, writ large, encompassed the narration of ship logs and route maps, the drawing of boundaries, the extermination of ‘natives’, the settling of peoples, the appropriation of property, the assessment of revenue, the raising of flags, and the writing of new histories – it was also parcelled into clusters of colonized territories to be controlled by increasingly powerful European nations, the Dutch, French and British in particular.

With the benefit of hindsight it is possible to see how European intellectuals became colonialism’s greatest champions. Hegel (1956), for example, in his introduction to The Philosophy of History, offers the following: ‘The Negro represents natural man in all his wild and untamed nature. If you want to treat and understand him right, you must abstract all elements of respect and morality and sensitivity – there is nothing remotely humanised in the Negro’s character […] nothing confirms this judgement more than the reports of missionaries.’

In other words, if Europeans were enslaving and treating Africans as they did, Africans had to be thought of as animals or at best subhuman; the God-fearing Caucasian was incapable of treating ‘brothers in Christ’ in such inhuman ways (Eze 1997). Arguably, it was this inversion of reason and morality which set the scene for the advent of nineteenth- and twentieth-century scientific racism with surprising effect on the European intellectual class. Liberals like Hobson cast their vote against empire, while Marx, ambiguously, regarded imperialism as morally repugnant, but historically progressive. Similarly, Mill had no difficulties in accepting that the civilized had special rights over, but also obligations towards, barbarians and savages, while also advocating a world order based on the right of national self-determination.

Africans resisted colonialism. They resisted it by force and they resisted it culturally and intellectually. There were many examples of this type of resistance. They ranged from the rising by the Mahdists in the Sudan (General Gordon and all that, 1884) through religious oppositional cults such as Mumboism in Kenya (1913–58) to refusal to pay hut and head tax in many places, refusal to work on plantations and to adopt agricultural and other types of innovation, and, perhaps of greatest lasting importance, the development of ‘voluntary associations’ in most parts of Africa, urban organizations which quickly took on a quasi or explicitly political complexion. However, by the mid-nineteenth century, African-ness and ‘the negro’ were well established as low points in the consciousness of Europe. W. E. B. Du Bois (1964: 39) was later to conclude that ‘never in modern times has [so] large a section of [any society] so used its combined intellectual energies to the degradation of [black humanity]’.

As Edward Said suggests in his book Orientalism (1979), if ‘the Orient’ was created as an object to be studied as exotic and ‘other’, and thus alienated from the mainstream of the world (meaning European) history, then this is also true of Africa. What we see is cultural dehumanization and alienation in the European perception of Africa. It is this dehumanization which explains why the cultural battle was so important and shows us how brave were people who raised dissenting voices to the imperial orthodoxies (as were those European intellectuals who allied themselves with this view). In his important survey of ‘African and Third World theories of imperialism’, Thomas Hodgkin suggests the following periodization of such resistance: the late nineteenth century (writers such as Blyden) in the period of imperial expansion; 1900–45, the period of partially effective colonial domination, notably the francophone African writers associated with the cultural/political movement known as négritude, including Lamine (Leopold) Senghor, Emile Faure, Garan Kouyaté and Aimé Césaire; and the post-1945 phase, concerned with the more active political leaders, Kwame Nkrumah (Towards Colonial Freedom, emphasizing pan-African ideals), Julius Nyerere (Ujamaa: Essays on Socialism, emphasizing African socialism) and Frantz Fanon (The Wretched of the Earth), who concerns himself with the impact of colonialism on the personalities of the colonized and the colonizers (Owen and Sutcliffe 1972). Most of this thought in the twentieth century was to a greater or lesser degree influenced by Marxism, which is unsurprising as this was the main oppositional ideology, with its own power bloc.

An important intellectual/cultural/political strand, most of all among francophone Africans, is identified with the name of Senghor. Senghor (b. 1906), a colonized French soldier, member of the French National Assembly, poet, member of the Académie Française, later president of Senegal, was representative of much in the whole culture of négritude. He was very intellectual, scholarly, literary and French. The titles of his essays indicate the seriousness of his thought and also the debt it owes to French culture: ‘African metaphysic’, ‘The relevance of Marx to Africa’, ‘No political liberation without cultural liberation’. However, the point about négritude is that it arose in response to French assimilationist policies (turning Africans into Frenchmen) and said there is much in African culture which is important and valuable. Arguably it was a step in a dialectical movement, which sought to bring white and black together in a classless society.

As such, the notion that négritude was racist is profoundly inaccurate. In truth, the movement was not a negation of others; rather it was an affirmation of Africa’s contribution to the universal culture. As Senghor says, ‘Africa’s misfortune has been that our secret enemies, in defending their values, have made us despise our own.’ Whereas in fact: ‘Négritude is a part of Africanity. It is made of human warmth. It is democracy quickened by the sense of communion and brotherhood between men. More deeply, in works of art, which are a people’s most authentic expression of themselves, it is sense of image and rhythm, sense of symbol and beauty’ (Senghor 1950).

It was ultimately this curious identity of interest between the diasporic character of the disciples of négritude and the fact that French was the only medium available to them to communicate which created the impression of racism. By adopting the French language, these writers found themselves in the paradoxical situation of espousing the very culture that they appeared to be bent on rejecting. As Sartre points out, ‘they speak in order to destroy the language in which the oppressor is present: their main project is to “de-gallicize” its signifiers’ (Sartre 1979).

A more recent development from this tradition in an unexpected form appears in the work of Bernal. In his book Black Athena (1991), Bernal suggests that before the late eighteenth century in Europe, it was well known that classical Greece was deeply rooted culturally and linguistically to the south and the east, in Ancient Egypt (Africa) and in Palestine (Phoenicians, Jews), rather than in some northern invasion. The response to this knowledge in the nineteenth century and after was to suppress it because it did not fit in with European racial prejudices. Bernal does not make this argument lightly; he supports it with a wealth of scholarship. The impact of the book among black American intellectuals has been enormous. Bernal has become a cause célèbre. In some American departments of black studies, people are now taught that all knowledge comes from Africa and that all European knowledge is to be dismissed as racist (although some of it certainly is). This, in our view, is as racist a response as any other and a response that threatens to throw out the rational baby with the white racist bathwater.

The facts are that Bernal’s book redresses the balance. Used wrongly, it leads to irrationalism. Now this is perhaps an obscure example, but the unbalancing effect of recognizing racism in scholarship and then dismissing all scholarship is more profound in another area, the research on AIDS. In their book AIDS, Africa and Racism (1989), R. and R. Chirimuuta argue that most of the research on AIDS in Africa has tended to blame Africa and Africans for the disease, and that this is a racist conspiracy, when in fact AIDS may well be the result of escapes from germ warfare laboratories – see Chapter 5. There seems little evidence for this latter point. What does seem to be the case is that HIV may have originated in Africa, that around 38 million people are infected, and that the Western press has often made, and continues to make, the link between sexuality, race and disease. However, all this should not lead us to dismiss the results of research that produces information of use in fighting an epidemic disease. The point is that just because the balance has gone one way (suppressing African history and culture, racism) we should always be careful not to let the balance swing the other way in order to assuage our liberal consciences. We must remain critical of the way that all knowledge is constructed.

However, the more pointedly political expressions of African thought in the period before independence and in the 1960s and 1970s emphasized the socialistic and pan-African nature of African thought and tradition. The two most influential writers here are probably Kwame Nkrumah and Julius Nyerere, although Senghor’s On African Socialism was also important. The former, educated in Britain, leader of the Ghanaian independence movement and first president of Ghana, emphasized the need for African unity and a common position vis-à-vis the imperialists; Nyerere (1968) argued that African culture had always been socialist, thus:

In our traditional African society we were individuals within a community. We took care of the community and the community took care of us. We neither needed nor wished to exploit our fellow men and in rejecting the capitalist attitudes of mind which colonialism brought into Africa, we must reject also the capitalist methods which go with it. To us in Africa land was always recognised as belonging to the community […] the foundation and the objective of African socialism is the extended family.

These important philosophical positions, pan-Africanism and socialism, were the organizing principles of the independence struggles and the early years after independence. In Tanzania, the idea received its fullest expression in the official policy of ujamaa, and it is here that we learn a depressing lesson. Ujamaa turned into statist direction of the peasantry; in Ghana, the Convention People’s Party became a site of corruption and oppression. Pan-Africanism received much formal support, but the institutions were not developed. Indeed, the Organization of African Unity (OAU) and its successor the African Union (AU) have remained ineffective and conservative, while African states have had diverse interests and have been the plaything of individual rulers and the victims of dabbling by foreign powers. With the changes in South Africa, even that unifying issue has become a less certain reference point.

The colonial impress

By the midpoint of the nineteenth century, the European political elite had accepted the civilizing logic of imperialism as propagated by the intellectual class. Empires were, therefore, justified on the basis of good government and the transmission, through education, of civilizing values. As a result, Africa would exist in the European psyche as the barbaric Other, and the point is not whether it had foundation in either logic or reason; it simply offered the legitimacy for the politics of dominance to be pursued against people of difference. At no point was this more evident than in the lead up to the Congress of Berlin of 1884. In the decade leading up to the conference, the chief instigator, King Leopold II of Belgium, summoned a conference in Brussels to which he invited representatives from Europe and America to launch what came to be known as the International African Association. There, in 1876, King Leopold II spoke as a humanitarian, and as one interested in geographic exploration for the sake of science: ‘To open to civilization the only part of the globe where it has not yet penetrated, to pierce the darkness shrouding entire populations, that is, if I may venture to say, a crusade worthy of this century of progress.’

However, from beneath King Leopold II’s affable altruism there peeped the true intent of European interest in Africa:

Among those who have most closely studied Africa, a good many have been led to think that there is advantage to the common object they pursued if they could be brought together for the purpose of conference with the object of regulating the march, combining the effort, deriving some profit from all circumstances, and from all resources, and finally, in order to avoid doing the same work twice over. (Legum 1961)

Leopold’s persuasive approach dovetailed with that of Prince Otto von Bismarck, the then Chancellor of Germany, intent on preventing any of the large European competitors from gaining advantage in Africa. Under King Leopold of Belgium’s pretext of settling the narrow issue of Congo, the Congress of Berlin became the Magna Carta of the colonial powers in Africa. Because the Congress made effective control of territory the test of ownership, the continent was rapidly occupied and divided. As a result, any European power which, by treaty or conquest, picked out a choice bit of Africa would be recognized as its lawful ruler, provided no other power had already laid claim to it. ‘We have been giving mountains and rivers and lakes to each other,’ British prime minister Lord Salisbury admitted after the Congress, ‘unhindered by the small impediment that we never knew exactly where they were’ (cited in Midwinter 2006). They were unhindered as well by the fact that all these lands belonged to others. Over the next fifteen or so years, the European powers consolidated their coastal enclaves and expanded them into the interior. Basically, this involved pushing the borders along the coast until they collided with another European power’s borders and then drawing points of contact inland.

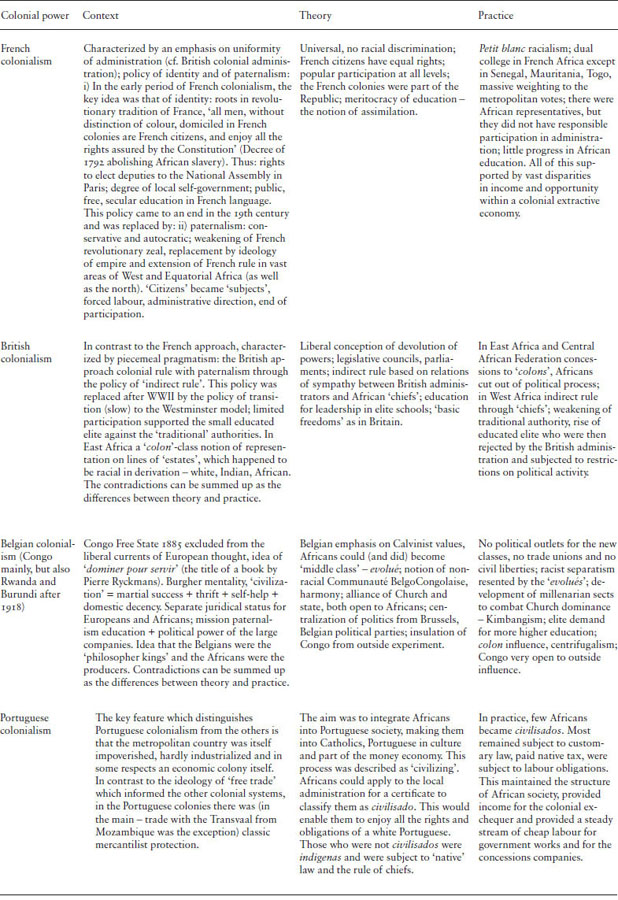

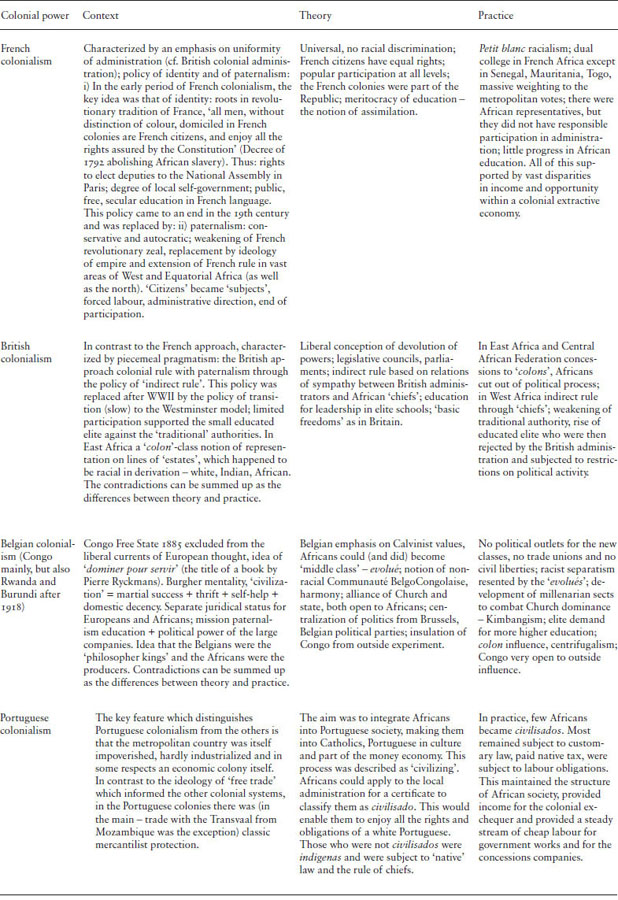

Within their colonial boundaries, the colonizers constructed African economies to serve European rather than African interests and integrated African markets into the global division of labour. As large-scale plantations developed and expanded on the continent in order to service European demands, there was also an influx of a significant number of European settlers. These settlers were concentrated heavily in the eastern and southern parts of the continent, as well as in Algeria. Although their numbers were relatively small, paradoxically this was a major source of strength. It provided a very effective way of preserving the assumption of white superiority on which the whole edifice of colonial administration depended. The patents for the administrative grids fashioned in London or Paris, in Brussels or Lisbon, varied in style and design, but colonialism in its different variations (see Table 1.1) was either direct or indirect rule with the norm being a mix of the two.

Direct rule usually involved the breakdown of traditional structures of power and authority, which were replaced with rule by white European administrations whose officers were sent out from the metropole. Direct rule did not spread widely to the countryside except if there existed valuable mineral resources, such as in the Copperbelts of Zambia and Katanga, or concentrations of white European settler-farmers, such as in the highlands of Kenya, Natal, the central highlands of Namibia and southern Rhodesia. However, it was in urban areas, particularly the colonial capital cities, such as Dakar, Lusaka and Nairobi, that direct rule was mostly exercised.

TABLE 1.1 Variations in colonial systems

Indirect rule was most often found in the rural areas that Europeans did not consider suitable for farming and settlement, where no substantial resources, such as minerals, were located, and where the colonial administrative machine found it hardest to permeate owing to the paucity of resources. It was also where there were traditional or customary rulers and authorities who could be authorized and relied upon to maintain order and allegiance to the metropole in return for leaving these indigenous and localized structures of power undisturbed. As Mamdani (1996) makes clear in his Citizen and Subject, in non-settler colonies colonialism reinforced and promoted a form of ‘customary’ power – that is, traditional authority – although this was always subordinated to colonial state rule in order to effect ‘indirect rule’. Indirect rule had definite advantages for a colonial regime: it was cheaper to administer and had the effect of boxing African people into discrete ethnic or ‘tribal’ units maintained by African leaders whose interests were also served by emphasizing and maintaining tribal mentalities among their peoples. Ranger (1996) describes ethnicity as a great colonial ‘invention’ that involved ascribing monolithic identities. According to Vail (1993), these were key in preventing the appearance of detribalized natives of whom white colonialists were deeply suspicious.

Where indirect rule was most prominent, a local oligarchy was often subsumed and made reliant upon the metropole. It was through these autocratic, but mostly respected, organs of power that the will of the colonial administration was imposed. In some cases, such as with the Lozi of Barotseland and the Baganda of Uganda, the internal political structure of the nation was left virtually untouched except that traditional rulers were now answerable to a narrow, white, elite layer of authority. This authority was invariably located in a remote European-style new urban place such as Lusaka, or an adapted African urban place created for colonialist economic expediency. So long as value, usually in the form of taxes combined with migrant labour, was seen to be exacted from these rural regions, the colonial administration exempted itself from the need, impetus and expense of extending formal colonialism to peoples and regions not deemed economically viable.

Thus, through the cooperation of traditional leaderships, colonial regimes were able to withhold modernizing influences applied in the colony area from other parts of the country, sowing the seeds for future mistrust and intergroup rivalry. This is at the root of much of the inter-ethnic rivalry in Nigeria, where first Yorubaland in the south-west and then Iboland in the south-east benefited from educational, professional and commercial opportunities, while in the north, which received none of these, Britain found willing allies for their system of indirect rule in the Fulani emirs (Bartkus 1999). That traditional rulers and colonial overlords seemed able to coexist and cooperate so well can be ascribed to the fact that both existed as the most powerful echelons of their societies, which were highly stratified by class. Both were used to occupying and articulating power and status.

The same dichotomous power relations between urban and rural populations continued when colonial rule gave way in the second half of the twentieth century to rule by African nationalists from the urban centres; they also inherited from the departing colonial regimes whatever institutional capacity was left behind. The towns, cities and whatever industrial development existed were much easier to imbue with republican and African nationalist sentiment. Urban populations could more easily be deracialized and democratized. Here we can equate ‘democratize’ with the taking on of citizenship along the lines of the Greek city-states, where those in the countryside were considered as backward and less developed. Urban bias quickly set in, encouraged by the modernization thinkers and strategists of the day and as the new governments also realized that their constituencies lay in the towns and cities. Meanwhile, in the rural areas, most of which the colonialists had not bothered to penetrate (with the obvious exception of settler agricultural areas) or had kept under control using the sway of traditional leaderships, contestation over political allegiances soon began to emerge.

As in the case of the Lozi, sharp differences soon emerged between the all-encompassing ideals of nationalism and the threat that this posed to traditional leaderships and authority. Nationalist politicians encountered difficulties in mobilizing rural people and their leaders through dynamics such as deracialization, which was rarely an issue in the countryside, and democratization, which was perceived as threatening the status quo of traditional authorities. This sometimes resulted in outright conflict or it simmered beneath the surface amid an atmosphere of suspicion and innuendo. Traditional leaders were portrayed by the nationalists as backward and reactionary, holding up the spread of modernity to the rural masses. The former colonial powers mostly supported the new nationalist governments; they left former polities that they had used to their advantage in indirect colonial rule at the mercy of nationalist regimes that felt little empathy towards traditional rulers.

The colonial economies

Looking back at the 1920s and the 1930s, it is difficult to escape a certain surprise at the general ease with which the imperial powers retained control over the colonial possessions in Africa. Indeed, and despite what we will say below about centralization, the colonial system was in some respects very tenuous, dependent upon quite limited numbers of European personnel. For example, the whole of Nigeria, with a population of around twenty million, was administered by 386 colonial civil servants (1:54,000 of the population); there were 4,000 soldiers and 4,000 police, of whom only around 150 were British. In French West Africa, the ratio was 1:34,800; in the Belgian Congo, 1:27,500 (Post 1964). In Mozambique, the colonial administration was even more remote, with parts of the country being administered by concession companies (Newitt 1981).

By the 1930s, the pre-colonial economic structures had been remodelled into a series of colonial economies with distinct characteristics. The common element was that they were all concentrated on production of foodstuffs and raw materials for metropolitan processing and consumption. In turn, they reimported processed commodities. The development of infrastructure reflected the extractive nature of these economies. There were three main patterns:

The West African (found also in Uganda) – involving the incorporation of peasant farmers (Nigeria: groundnuts, Ghana: cocoa, Uganda: coffee and cotton).

The Equatorial/central/southern pattern – company-owned plantations using forced/waged labour – oil palm, rubber in Congo, Angola, Mozambique, and to some extent in Tanganyika, sisal. Also associated with mining in some places (Katanga, copper).

The settler pattern – white settlers using wage labour (Southern Rhodesia). However, there were variations in this pattern depending upon whether or not the white settler interests were considered paramount. Thus in Congo, Mozambique and Angola, European settlers combined with concession companies and their interests were paramount; in contrast, in Kenya, Côte d’Ivoire and Northern Rhodesia, African interests were not unprotected.

These differences had implications for how decolonization was possible. Thus, in the areas where concession companies and settlers were least important (Gold Coast, Nigeria, Upper Volta, Senegal), independence came easiest. Contrast these areas with Southern Rhodesia and Mozambique, where white settlers and companies fought to protect their interests. In all areas, however, few African rural people remained unincorporated into the world economy with forced labour and peasant production of cash crops. The effects were the development of a rural sub-proletariat associated with the plantation, labour migration and the development of an urban proletariat in mining areas. As labour was diverted from food production in these areas, so other areas had to compensate and become surplus-producing. In these areas, often of smallholding production, new forms of rural social differentiation began to develop. We see this continuing to have an impact on current challenges to food security and access to land, as will be explored in detail in Chapter 3.

The whole system functioned on the conviction that the administrator (the white European) was sovereign and that their subjects neither understood nor wanted self-government or independence. Indeed, such were the ambiguities in which rulers and the ruled were involved, they were generally only vaguely, if at all, aware of them. If there was any training and adoption of the native, it was a schooling in the bureaucratic toils of colonial government; a preparation not for independence, but against it. It could not be otherwise. Colonialism was based on authoritarian command and, as such, it was incompatible with any preparation for self-government. In that sense, every success of administration was a failure of government. With good reason, then, both Africans and Europeans usually approached problems of governance circumspectly.

The Second World War had a profound impact on colonizers and colonized alike, setting in train a series of developments that led to the rapid dismantling of the European empires. Once war began, the Western Allies’ claim that the basic issue was freedom versus tyranny had a meaning to Africans that the Allies had not entirely foreseen. In particular the Atlantic Charter (1941) forged by American president Franklin Roosevelt and British prime minister Winston Churchill promised self-determination for all people. The war also revealed and increased European weaknesses. In 1940, Nazi armies crushed France in a lightning campaign, occupying most of the country and reducing the rest to a dependency. Even more stunning, Japan inflicted a devastating series of defeats on British forces in the Far East the next year, shattering for ever the Europeans’ myth of their inherent superiority over the rest of humankind.

The end of the war left the metropolitan powers exhausted and weak. More fundamentally, and as Basil Davidson rightly noted, ‘the war gave a new spur to anti-colonial protest’ (Davidson 1964). It brought a new force to the call for anti-colonial change, and the war experience helped to develop a better resistance to colonial rule. By the end of the war, although African colonies were still economically dependent on their colonial powers, the latter’s political and social control was weakened beyond repair. Indeed, this pattern was evident across the colonial world. The Dutch tried holding on to Indonesia, as the French tried in Indochina and subsequently in Algeria, by massive force and at disastrous cost. The sporadic troubles of the British Empire, previously put down by punitive expenditure, were tending to grow into prolonged guerrilla wars. In the African case, the result was a cascade of constitutional formulae and bargaining processes, which eventually culminated in the emergence of native-rule states on the continent.

Though independence brought an extraordinary opportunity to establish something resembling the Hobbesian social contract in Africa, in truth it was severely flawed (Zartman 2005). Studies of particular colonial records show that it is very difficult to trace any continual preparatory process at work, or any sign of a prepared policy until after the Second World War. Even then the post-war years were too late for preparation, save as a purely political, almost desperate, effort to provide an ideology of delay (in the granting of independence). The notion of preparation was to justify the colonial record, as a tactic of delay in the sense that ‘you would not seem to be delaying, only training and educating’ (Busia 1967). The Theory of Preparation ‘emerged after the event’, Lord Hailey (1961), a British colonial administrator, agreed. A decade after the end of the war, he wrote that there was no training machinery of administration ready to hand.

In this sense, the real political inheritance of the African elites at independence were the authoritarian structures of the colonial state, an accompanying political culture and an environment of politically relevant circumstances tied heavily to the nature of colonial rule. Imperial rule from the beginning expropriated political power. Unconcerned with the needs and wishes of the indigenous population, the colonial powers created governing structures primarily intended to control the territorial population, to implement exploitation of natural resources, and to maintain themselves and the European population for all European colonizers. British, French, Belgian, Portuguese, German, Spanish and Italian power was vested in a colonial state that was, in essence, a centralized hierarchical bureaucracy. In these circumstances, power did not rest in the legitimacy of public confidence and acceptance. There was no doubt where power lay; it lay firmly with the political authorities. Long-term experience with colonial states also shaped the nature of ideas left at independence. Future African leaders, continuously exposed to the environment of authoritarian control, were accustomed to government justified on the basis of force. As a result, notions that authoritarianism was an appropriate mode of rule were part of the colonial political legacy. Ironically, it was ultimately this curious identity of interest between the new elites and the colonial oligarchy which facilitated the peaceful transfer of power to African regimes in most of colonial Africa.

What emerged from the post-colonial agreement, therefore, was above all an agreement between nationalist elites and the departing colonizer to receive a successor state and maintain it with as much continuity as possible (Zartman 1964). Herbst (2000) also makes a very valid point about the agreement being explicitly about how nationalist elites allocate the ‘Golden Eggs of independence’, not an agreement involving the body politic, as the idea of a social contract implies. Less explicitly, it was also an agreement among the nationalist elite on the allocation of rules, roles and shares in the benefits of independence, not an agreement involving the body politic, as the idea of a social contract implies. Highly explicit was the notion that the nationalist movement turned single party incarnated the nation in its social, political and economic form; deeply implicit was the promise that the nationalized state would provide the population with the benefits that the colonizer had enjoyed and more, through jobs and services; when the golden eggs ran out, the goose was nationalized and distributed. However, no popular accountability was provided. The only accountability was to the military, and the replacement of nationalist elites by their military only locked the closed door of accountability.

When all that was left of the goose was bones, the nation demanded accountability of the state. Indirect taxation of agriculture, rent-seeking, corruption and poor management, over-indebtedness and falling terms of trade invalidated the old contract (ibid.). The collapse of ideological supports for party–state monopolies at the end of the Cold War and their replacement with notions of political and economic competition set the stage for new terms. However, full political and economic participation and political and fiscal accountability have taken hold, even imperfectly, in only a few places (Zartman 1997: 36–48). Instead, the second wave of democratization of the 1990s petered out on most of the continent, leaving only unsubstantiated forms of accountability and a population repeatedly disenchanted and alienated by rent-seeking elites. Instead of serving as the manager of conflicts and the arbiter of demands among various demand-bearing groups in society, the state has become the source of conflict with such groups and the repressor of their demands.

In the first decade of the new millennium, the appearance of a new social contract is still a development in waiting. Accountability that had appeared in many states in the 1990s then stagnated in either a Tweedledee–Tweedledum alternation or a one-step progression from a single party to a dominant party (un parti quasi-unique, in French-speaking Africa). Often, ethnic or atavistic rebellion made the system a bi-party or ‘quasi-federal’ state. Nations fractured into acephalic segmentary systems where none had existed before. Inefficiencies and structural adjustment limited state functions and state capacities. A third wave of state collapse has not materialized but widespread state failures have occurred. These conditions will be assessed in the following sections. Yet the African state continues to exist, perhaps held together in the end by a lack of alternatives.

State of Africa

There is a growing consensus on what the key elements of governance reforms in Africa should comprise. These include creating or strengthening institutions that foster predictability, accountability and transparency in public affairs; promoting a free and fair electoral process; restoring the capabilities of state institutions, especially those in states emerging from conflicts; anti-corruption measures; and enhancing the capacity of public service delivery systems. Nothing better illustrates Africa’s commitment to a new approach to governance than the establishment of the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM), under the aegis of the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD). Created as an instrument to which African governments voluntarily subscribe, the APRM has developed agreed codes of governance and incorporated a mechanism for review of adherence. About half of African countries have acceded to the APRM and several are nearing completion of their first review. The APRM is not intended to be an instrument for coercive sanctions, but a mechanism for mutual learning, sharing of experiences and identifying remedial measures to address real weaknesses. Thus, the periodic evaluation built into the APRM process will help governments address obstacles that hinder effective governance in their countries.

Critical to improving the quality and efficacy of the public sector is commitment to public service capacity-building. Capacity-building entails several components of which three are critical: namely training, funding of civil service modernization, and adequate pay for public servants. Deterioration in these areas has adversely affected the ability of the public sector to deliver services, and this theme is returned to throughout Chapters 3, 4 and 5. Indeed, inadequate levels of African salaries have been a major cause of weak incentives, high turnover and corruption. In many African countries, this has led donors to support expanded employment of expatriates. Although intended to compensate for weakness of national expertise, the practice uses up a significant proportion of aid resources without developing national capacity. United Nations (UN) studies have shown that it would be both cheaper and more sustainable if part of the aid budget were used, for an interim period of several years, to support national salaries, strengthen incentives and build national capacity on a sustainable basis. This would help African countries develop the expertise to manage their development programmes. Thus, one area in which international support should be aligned with African efforts is providing funding for these three critical dimensions of public service capacity-building.

In reality, four patterns are evident. First is the emergence of dominant party systems, in which opposition parties serve as safety valves or weak and ineffectual symbols of ‘good governance’, unlikely to come to power. This is Botswanan democracy, much touted for its freedom, but far from the test of alternation frequently proposed (Stedman 1993; Bauer and Taylor 2005). The same applies to Tanzania. The second pattern, an evolution from the first, limits the degree of change even when alternation occurs. Either the opposition coming to power ends up acting with the same corruption, cronyism and control as its predecessor, or it is replaced by the predecessor after a single turn, or the reality of change in the nature of the state is over. The first was the evolution of Senegal, Kenya, Zambia; the second in Benin benevolently, and Congo-Brazzaville violently.

The third pattern, partially overlapping some aspects of the other two, is the category of unreconstructed authoritarian regimes embodying the ethos of the previous civilian and military single-party regimes with only symbolic nods to the rising procedural demands, including, variously, Guinea, Togo, Congo-Brazzaville, Gabon, Chad, Burkina Faso, Rwanda, Eritrea and Angola; a motley assortment. The fourth category includes some arguably promising unknowns, whose seemingly positive multiparty experience is recent enough to warrant suspended judgement, including Sierra Leone, Liberia and Congo. The relation of such a categorization to the nature of the African state is complex. From this summary, it is hard to assert a winning dynamic in any of Africa’s regions that would tip it in the direction of full satisfaction of procedural demands for meaningful participation in the state. The dominant party system, the first pattern and its evolution, and the second pattern are functionally little different from the single-party system, with the exception that the latter has the softening feature of a safety-valve opposition to relieve pressure on the dominant/single party.

The ensuing model of the state is then one of an authoritative institution supported by a vertical column of the population, heavy at the top and charged with its own justification and legitimization rather than being emergent and supported from the base. Those not in the column are excluded from the system of allocating benefits and excluded from the allocation of benefits as well. An excellent study by Kayizzi-Mugerwa (2003) shows that African states privatized ‘only when the [politicians] were sure that the benefits to themselves and their supporters exceeded the costs, including loss of rents, of denationalization’ despite the opposition of ‘the local middle class’ and public opinion in general. When elections are not decisive, open, programmatic contests, private interests take over. ‘[R]egimes have sought to protect the interests of a narrow stratus of state elites and have regularly been willing to inflict austerity on the population’ (Van de Walle 2001: 16), a situation that the evolution from single-to dominant-party regimes, with or without alternation, has not changed. As an institution responsible to its stockholders, the state is above all beholden to its board of directors and only secondarily to its other shareholders, including multinational corporations, bilateral and multilateral donors and the international financial institutions.

Of course, this picture depends on the assumption, or the evidence, that the single/dominant party is a weak mobilizer, involving a limited column of supporters in a passive role, a description that generally obtains across the continent. One result of this situation is the outbreak of two types of endemic conflict, both of them voicing the complaint of the excluded. One is a centralist conflict for power without any programme to distinguish rebels from government. This is the time-at-the-trough phenomenon, whereby one group – often without any inscriptive or other distinguishing characteristic other than simply being excluded – seeks to replace the other in the seat of power without any clear ideological or programmatic difference. The conflict bears no procedural demand; it simply voices a substantive demand for me rather than for you. Thus rebellions such as the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) in Sierra Leone or Renamo in Mozambique were not ethnic revolts, and their programmatic elements were tenuous.

The other is a regional or ethnic revolt for self-determination, voicing deeply procedural demands to take the governing process into its own hands because those in power have shown that they cannot be trusted to allocate benefits fairly. Such are the rebellions of the Democratic Forces Movement in the Casamance in Senegal, the New Forces in the North in Côte d’Ivoire, the Acholi through the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in Uganda and the rebels in Darfur and Beja in Sudan, among others. Still others bridge the two categories; they are not content to seek self-determination for their region, but rather want their turn to govern everyone (as in the first type), but for the defence of their own ethnic group. Such were the Tutsi of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) and now the Hutu of the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR).

The frustrated shift from substantive to procedural demands in the 1990s has meant that that nature of the African state is still uncertain at a crucial junction. At the beginning of the shift it was torn between the pressures for change and the obstinate reality; in the middle of the first decade of the 2000s, pressures remained in violent conflicts, but slumped into alienation and indifference in the general public. The demands for pluralization, accountability and participation have produced results in form, but not much of a change in the nature of the state, from a delegated to a participatory democracy.

Conclusion

At one level, looking back, one may see now that the colonial period was no more than a single episode in the onward movement of African life. In another sense, it was an unexampled means of revolutionary change with its dramatic and lasting effects on the continent, its people and their history. In truth, the extension of European empires had mixed motivations. The people with whom the Europeans came into contact responded in different ways, as their own political necessities and values dictated. The impact of European expansion, therefore, is a complicated equation, being a function both of European motivation and African response. The consequences of those differential impacts are crucial to any understanding of the complexities of contemporary African politics and society.

In the end, none of these positions helps us to understand what is happening in Africa. In the twenty-first century, changes in the world order, the failure of statism as a strategy, the existence not only of an economic but also of a political crisis in Africa, make the careful study of a continent that contains 13 per cent of the world’s population of great importance. However, as a background to this study, we must recognize that there is also an intellectual crisis on the continent today. The old panaceas of African unity and African socialism seem to have failed. The intellectual analysis from within Africa of what is to happen and of what has happened is merely the beginning. For the moment, structural adjustment policies are dominant, and the old dictators (Mengistu, Kaunda, Moi, Banda, Mobutu) have gone, but where this all leads and what African intellectuals are making of it are not at all clear.