Chapter 2

Chapter 2

Facing the rising sun as they practiced, the ancient yogis called forward bending “stretching the west.” Forward bends stretch and strengthen the back portion of the spine, shoulder and pelvic girdles, and legs. They stretch and strengthen the entire length of the erector spinae muscles, which extend all the way from the sacrum to the cervical spine; the deep spinal extensor muscles and intervertebral ligaments, which interconnect and stabilize each vertebrae; the posterior muscles, which bind the shoulder girdle to the spine; and the posterior muscles of the pelvis and legs. In addition they strengthen the abdominal muscles, which contract as we bend forward; gently compress the abdominal organs (particularly the intestines), providing a visceral massage; and stretch the kidney/adrenal area, stimulating the function of these organs.

From a biomechanical perspective, according to the Viniyoga tradition, the primary intention of forward bending is to stretch the structures of the lumbo-sacral spine.

Above the lumbar spine, the secondary intention of forward bending is to stretch the posterior structures of the upper back, shoulder girdle, and neck.

Below the lumbar spine, the secondary intention of forward bending is to stretch the posterior musculature of the pelvic girdle and legs, particularly the hamstrings.

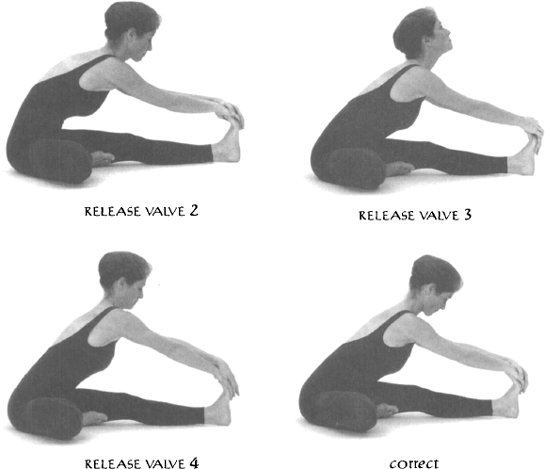

The key to forward bends is the ability to control the proportional relation between the progressive flattening and potential reversal of our lumbar curvature and the forward rotation of our pelvis at the hip joints.

The proportional relation between these two actions is known as lumbar-pelvic rhythm. In normal activity, we are usually unaware of this rhythm and, therefore, one aspect is often overemphasized.

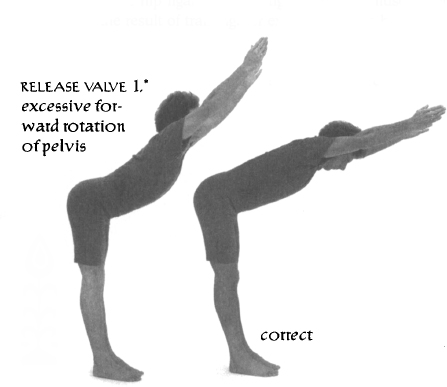

Forward rotation of the pelvis may be excessive because of actual structural conditions, such as loose hip ligaments and tight low back muscles, or the result of training: for example, due to habitually bending from the hips with a “straight” back in standing forward bends.

Bending in this way, in fact, increases the contraction of the low back muscles, inhibiting effective stretching, and places tremendous stress on the musculature, ligaments, and tendons of the hip joints. The possible long-term result of this practice is instability in the hip joints, chronic contraction of the lumbar muscles, and posterior intervertebral disc compression.

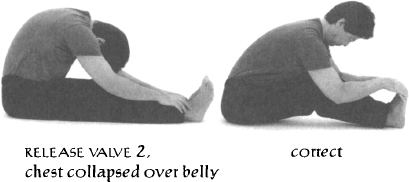

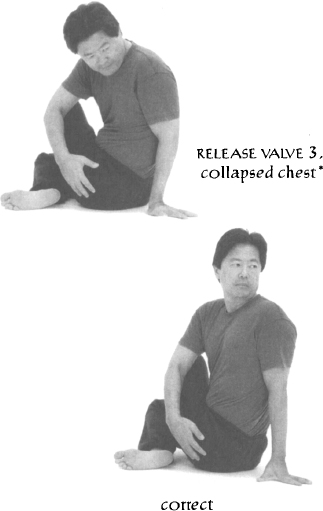

Reversal of the lumbar curve may be excessive because of actual structural conditions, such as tight hip ligaments and leg muscles (hamstrings), which restrict pelvic rotation, or the result of training: for example habitually insisting on straight legs in seated forward bends.

Bending in this way may, in fact, lead to a backward rotation of the pelvis and to a collapsing of the chest over the belly at the thoracic-lumbar junction. The possible long-term result of this practice is anterior intervertebral disc compression.

Low back pain is often the direct result of a poor mechanical relationship between the lumbar spine and pelvis. In fact, many chronic low back conditions originate in forward bended positions. And yet, it is also through the forward bend that we can improve our lumbar-pelvic rhythm and thereby strengthen and stabilize our body.

The key to the lumbar-pelvic rhythm, and therefore all forward bends, is the technique of abdominal contraction on exhale. At the initiation of exhalation, contract the abdominal muscles at their insertion into the pubic bone, thereby checking excessive forward rotation of the pelvis, promoting progressive reversal of the lumbar spine, and maximizing the stretching of the low back.

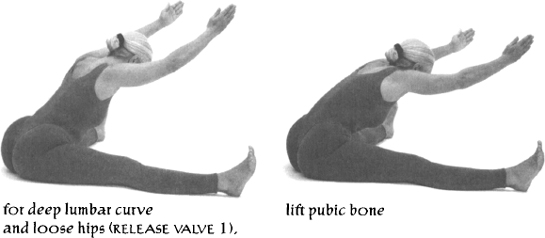

If you have either a deep lumbar curve and/or very loose hips, lift the pubic bone slightly upward at the beginning of the forward bend and focus on the stretching of the low back.

If you have tight hips, encourage the pelvis to rotate forward and focus on the stretching of the low back. In either case, be careful to avoid anterior compression of your lumbar spine.

As the forward bend proceeds, contract your abdominal muscles from the pubic bone to the navel. Bend your knees progressively throughout the movement, as much as necessary to feel the maximum stretching of your low back without strain.

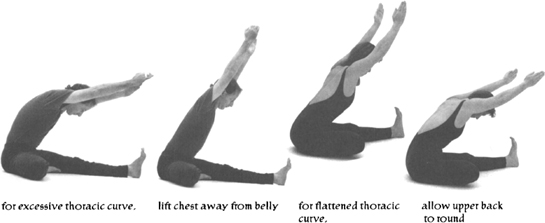

The natural curve of the thoracic spine may create a tendency to collapse the rib cage over the belly as you bend forward. This can be avoided by lengthening between the chest and belly on inhale and maintaining that length throughout the forward bend. This is especially important if your thoracic curve is naturally excessive. If, on the other hand, your thoracic curve is slightly flattened, then you can allow it to round slightly as you bend.

In coming up from a forward bend, lead with your chest from the initiation of inhale, pulling the entire thoracic cavity away from the abdomen and stretching in the solar plexus area. Maintain a partial abdominal contraction on the way up, preventing your pelvis from rotating excessively forward, in order to protect your low back from strain (particularly in standing postures).

This will also facilitate elevating the rib cage and reversing any exaggeration of the thoracic curve.

Though the cervical spine can flex easily, many people tend to arch their necks in the process of bending forward, either because of actual structural conditions, such as tightness in the muscles of the upper back and neck, or because of training: for example, habitually lifting the chin while bending forward.

This practice, over time, creates tension in the neck and shoulders, may lead to headaches, and also limits the effectiveness of the forward bend itself. Instead, we suggest that you tuck the chin in gently toward the throat while displacing the head slightly backward, until the ears are aligned above the shoulders. This technique straightens the cervical curve, helps straighten the thoracic curve, and increases the stretching of the muscles of the upper back and neck.

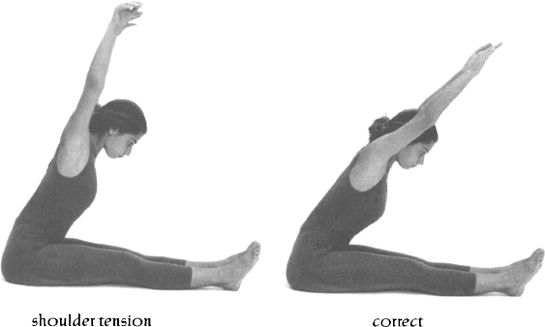

Raising the arms overhead, in coordination with the movement of the thoracic cavity on inhale, aids the extension of the spinal curves. Classically, the arms, chest, and head are held in alignment while moving into and out of forward bends. However, as this technique may create tension in the neck and shoulders, the arm position can be adapted to minimize stress and/or emphasize a particular effect.

Further examples of arm variations can be seen in the therapy section later in the book. In general, to avoid tension, it is important to allow the arms and/or head to follow the lead of the spine, rather than to themselves lead.

Forward bends can be done supine (on the back), kneeling, standing, and seated. Supine and kneeling postures are generally simple, stable, and safe. Standing postures allow the greatest range of unrestricted motion and, therefore, are usually safe and effective for warming up and working the large musculature of the spine, pelvis, and legs. Seated postures are the most restricted, and while they provide the deepest stretching, they also incur the greatest risk to the musculature and ligaments of the spine, shoulders, pelvis, and legs.

GROUP 1

GROUP 1

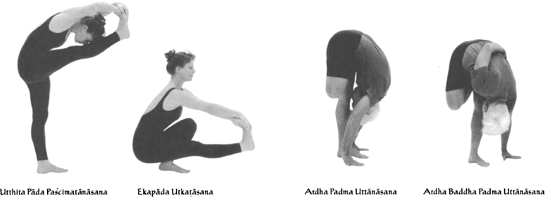

The first group of postures includes open- and fixed-frame symmetric standing and seated forward bends, with the legs extended and feet close together. Although classically the feet are together, we suggest that they remain slightly apart, vertically below the thigh bone’s (femur) junction (acetabulum) with the pelvis.

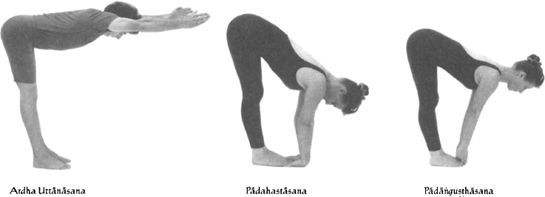

Ardha Uttānāsana builds strength in the posterior spinal musculature.

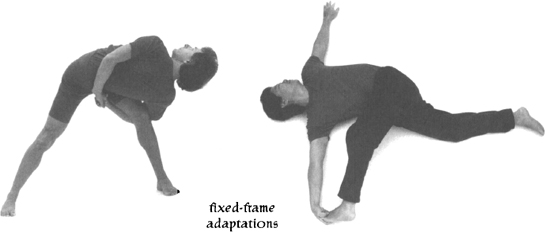

Pādahastāsana, Pādāngusthāsana, and Ubhaya Pādāngusthāsana are fixed-frame postures. The leverage created when the hands hold the feet deepens the forward bend. Paścimatānāsana can also be adapted as a fixed-frame posture.

This group of postures includes open- and fixed-frame asymmetric standing and seated forward bends. In the seated forward bends, one leg is extended and the other folded and rotated either externally or internally. The position of the leg significantly influences the effect of the forward bends. Generally, asymmetric positions isolate and intensify the stretching effects on one side of the back and in one leg. Ardha Pārśvottānāsana builds strength in the muscles of the back.

Marīcyāsana, Krauñcāsana, Ardha Padma Paścimatānāsana, and Ardha Baddha Padma Paścimatānāsana are fixed-frame postures, using the arms and legs as levers in different ways to modify and deepen the effects of the postures. Marīcyāsana stretches the deep and superficial posterior muscles that bind the shoulder and arm to the spine. Krauñcāsana strongly stretches the back of the extended leg. Ardha Baddha Padma Paścimatānāsana strongly stretches the hip rotators of the folded leg.

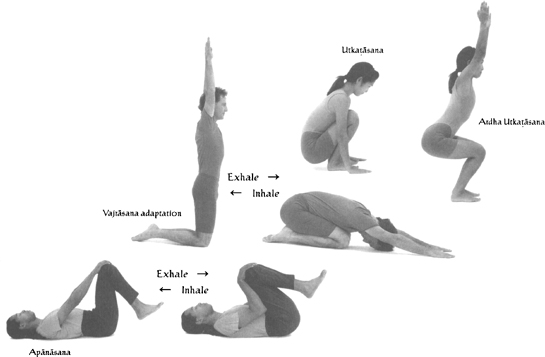

This group of postures includes open- and fixed-frame symmetric forward bends, in which the knees are near the chest and the buttocks near the heels. This position offers a safe and effective stretching of the lower back. Apānāsana is the simplest of all forward bends. Utkatāsana strongly develops the big muscles of the thighs.

GROUP 4

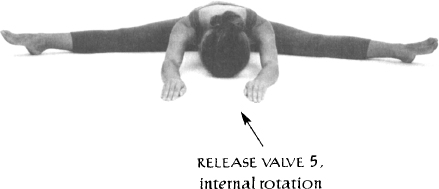

GROUP 4This group of postures includes open- and fixed-frame symmetric standing and seated forward bends with spread legs. This position of the legs facilitates the forward rotation of the pelvis and increases the stretching of the inner thighs.

In Kūrmāsana, the arms wrap under the legs and the hands are grasped behind the back. The leverage generated by the arms and legs makes this one of the deepest forward bends. If you can master this posture, you will experience the truly calming and internalizing potential of forward bends.

GROUP 5

GROUP 5Nāvāsana is the sole member of this group. This open-frame posture is unique in its function as a forward bend. Unlike other forward bends, the primary intention is strengthening and stabilizing the lumbar-pelvic relationship rather than stretching the lumbosacral spine.

The greatest risk in forward bends is to the lumbosacral spine. If, in standing-forward bends, the lumbar curve is maintained too long when going down, or regained too soon when coming up, there can be low back strain and excessive posterior disc compression. If, in seated-forward bends, the hips cannot rotate forward, there can be excessive anterior disc compression. In either case, if the sacroiliac joint is weak, there can be strain to the ligaments.

There is also risk in forward bends to the musculature and ligaments of the hip joints. Excessive forward rotation of the pelvis, over time, may create instability in the hip joints and a susceptibility to injury. Developing the proper pelvic-lumbar rhythm will minimize risks to both the low back, sacrum, and hips.

There is some risk of strain in the area of the upper back, shoulder girdle, and neck in coming up from a forward bend. Adapting the position of the arms and avoiding pulling the spine with the head will usually alleviate this stress.

1.

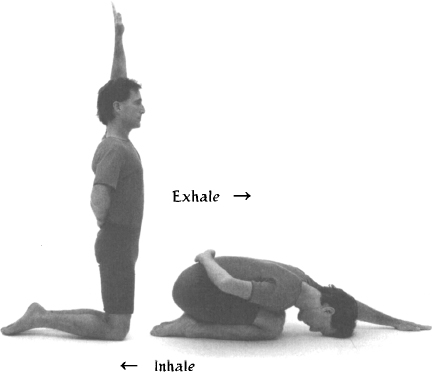

POSTURE: Vajrāsana.

EMPHASIS: To warm up body. To stretch low back.

TECHNIQUE: Stand on knees with arms over head.

On exhale: Bend forward, sweeping arms behind back, and bringing hands to sacrum, keeping palms up.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Bring chest to thighs before bringing buttocks to heels. Rotate arms so palms are up and hands are resting on sacrum. On inhale: Expand chest and lift it up off of knees as arms sweep wide.

2.

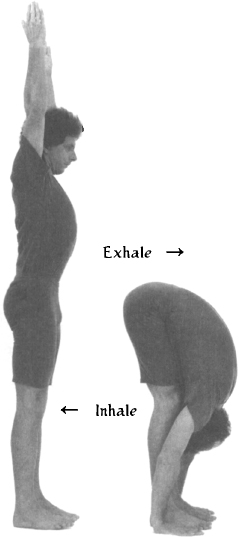

POSTURE: Uttānāsana.

EMPHASIS: To warm up back and legs.

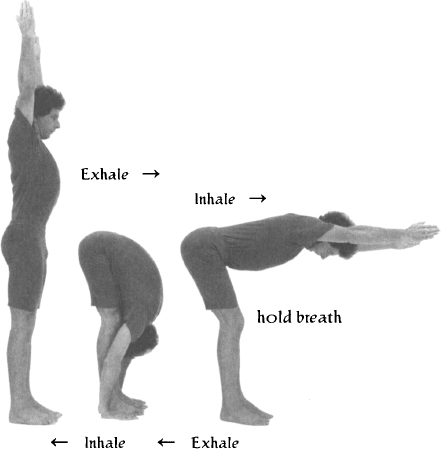

TECHNIQUE: Stand with arms over head.

On exhale: Forward bend, bringing belly and chest toward thighs and bringing hands to feet.

On inhale: return to starting position.

NUMBER: 6 times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Bend knees to facilitate stretching of low back. Move chin down toward throat. On inhale: Lift chest up and away from thighs, flattening upper back. Keep knees bent until end of movement.

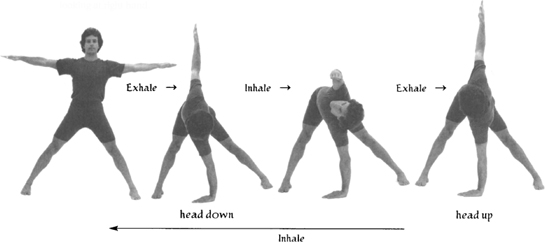

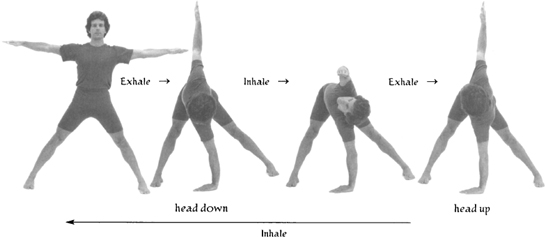

POSTURE: Parivrtti Trikonāsana.

EMPHASIS: To stretch legs, back, and shoulders.

TECHNIQUE: Stand with feet spread wider than shoulders, with arms out to sides and parallel to floor.

On exhale: Bend forward and twist, bringing left hand to floor, pointing right arm upward, and twisting shoulders right. Turn head down toward left hand.

On inhale: Maintaining rotation, and with right shoulder vertically above left, bring right arm up over shoulder and forward, turning head to center and looking at right hand.

On exhale: Return to previous position with right arm pointing upward. Turn head up, looking toward right hand.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

Repeat on other side.

NUMBER: 6 times each side, alternately.

DETAILS: Keep down arm vertically below its respective shoulder, and keep weight of torso off arm. Knees can bend while moving into twist.

4.

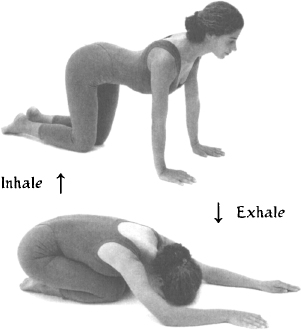

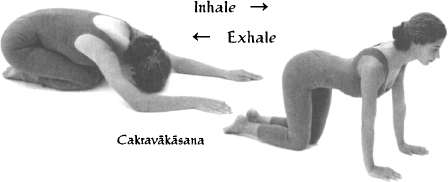

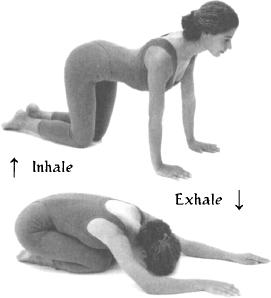

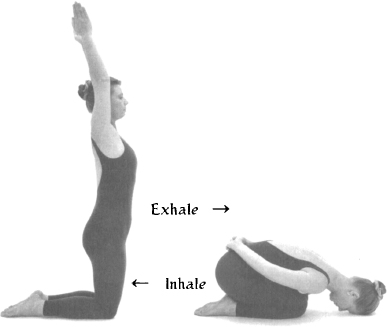

POSTURE: Cakravākāsana.

EMPHASIS: To make transition from standing to supine position. To stretch rib cage on inhale and low back on exhale.

TECHNIQUE: Get down on hands and knees, with shoulders vertically above wrists and with hips above knees.

On inhale: Lift chest up and away from belly.

On exhale: Gently contract belly, round low back, and bring chest toward thighs.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Lead with chest, keeping chin slightly down. Avoid compressing low back; rather, feel chest expanding. On exhale: Round low back without collapsing chest over belly. Avoid increasing curvature of upper back. Let chest lower toward thighs sooner than hips toward heels.

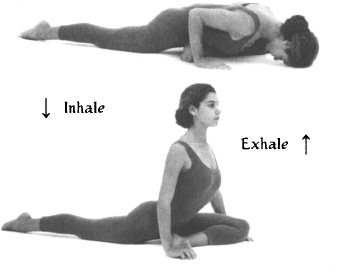

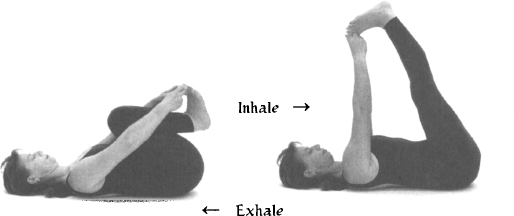

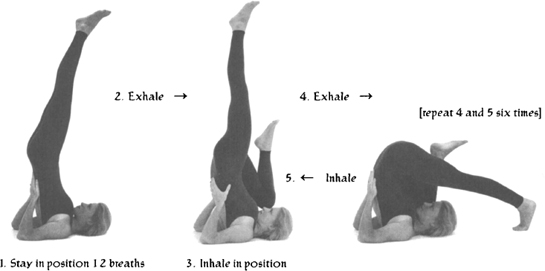

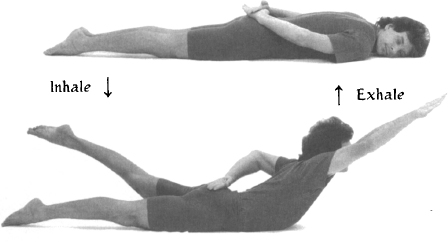

POSTURE: Supta Prasārita Pādāngusthāsana.

EMPHASIS: To stretch musculature of lower back, backs of legs, and inner thighs in preparation for seated forward bends.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with knees lifted toward chest and with hands holding respective toes.

On inhale: With hands holding toes, lift heels upward, straightening legs.

On exhale: Stay in position.

On inhale: Open legs wide, pulling legs apart gently with arms.

On exhale: close legs.

Repeat 6 times; then stay open 6 breaths.

DETAILS: Keep sacrum, chin, and shoulders down throughout movement. If legs are loose, hold balls of feet while staying in final position.

6.

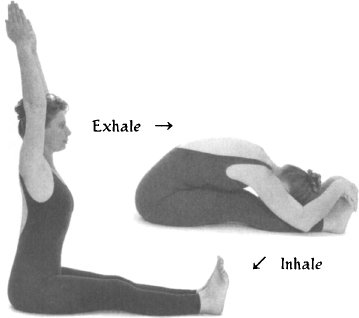

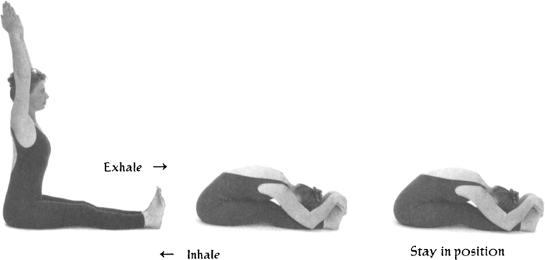

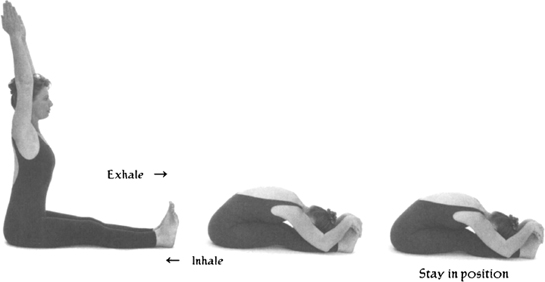

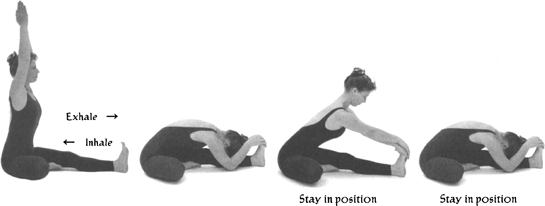

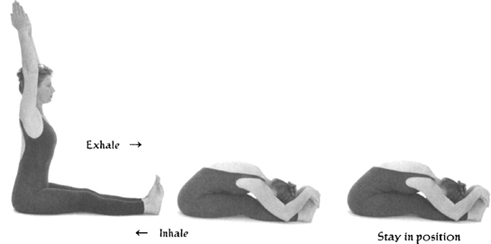

POSTURE: Paścimatānāsana.

EMPHASIS: To stretch back and legs in preparation for Kūrmāsana.

TECHNIQUE: Sit with legs forward, back straight, and arms raised over head.

On exhale: Bending knees slightly, bend forward, bringing chest to thighs and palms to balls of feet.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 6 times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Bend knees to facilitate stretching low back and bring belly and chest to thighs. Move chin down toward throat. On inhale: Lift chest up and away from thighs, flattening upper back.

POSTURE: Kūrmāsana.

EMPHASIS: To stretch musculature of back, shoulders, and legs. To experience one of the deepest forward bends.

TECHNIQUE: Sit with legs straight forward and apart wider than shoulders. Bend forward, with bent knees, and slide arms under knees, wrapping them around torso, clasping hands behind back. Stay in position 8 breaths. Extend legs progressively straighter.

8.

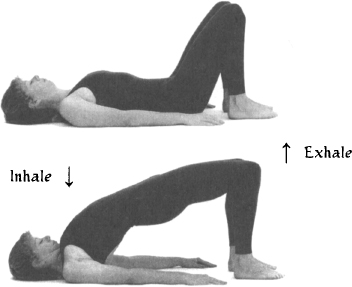

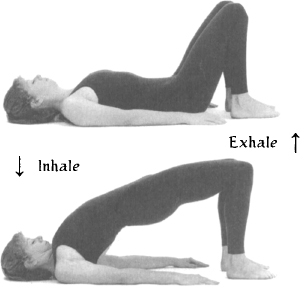

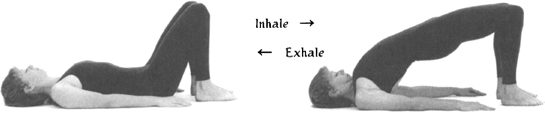

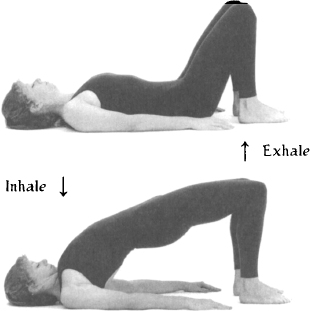

POSTURE: Dvipāda Pītham.

EMPHASIS: To relax back and stretch belly.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with arms down at sides, knees bent, and feet on floor, slightly apart and comfortably close to buttocks.

On inhale: Pressing down on feet and keeping chin down, raise pelvis up toward ceiling, until neck is gently flattened on floor.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 6 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Lift spine, vertebra by vertebra, from bottom up. On exhale: Unwind spine, coming down vertebra by vertebra.

9.

POSTURE: Śavāsana.

EMPHASIS: To rest.

TECHNIQUE: Lie flat on back, with arms at sides, palms up, and legs slightly apart. Close eyes. Relax body fully, keeping mind relaxed and alert to sensations in body.

DURATION: Minimum 3 to 5 minutes.

As part of their sunrise practice, the ancient yogis called backward bending “stretching the east.” Backward bends stretch and strengthen the front portion of the torso, the shoulder and pelvic girdles, and the legs. They stretch and strengthen the iliopsoas muscles, which lay deep under the anterior musculature of the abdomen and pelvis and bind the legs to the spine; the diaphragm and intercostals, which are the primary musculature of respiration; the anterior muscles, which bind the shoulder girdle to the spine; and the anterior muscles of the legs. In addition, they strengthen the superficial and deep muscles of the back, which contract as we bend backward; strengthen the posterior muscles of the shoulder girdle; stretch the abdominal organs, relieving visceral compression; gently compress the kidney/adrenal area, stimulating its function; and stretch the anterior muscles of the neck and throat, including the area of the thyroid and thymus glands.

From a biomechanical perspective, according to the Viniyoga tradition, the primary intention of backward bending is to expand and stretch the anterior structures of the chest and shoulder girdle, and to stretch the anterior musculature of the solar plexus, abdomen, hips, and thighs. The primary focus in different back bends can be the chest and shoulders, the solar plexus and abdomen, the hips and thighs, or equally distributed among them all.

The secondary intention of backward bending is to strengthen the musculature of the back. In certain backward bends, this strengthening is actually more important than the anterior stretching.

The key to backward bends is the ability to control the proportional relation between lengthening and flattening the thoracic curve and deepening the lumbar curve.

The proportional relation between these two actions is known as the thoraco-lumbar rhythm. Though the thoracic spine has a limited capacity for arching backward, due to the structure of the spinous processes and the rib cage, the lumbar spine can arch deeply. The tendency to excessively arch the lumbar spine in backward bending may be increased by individual structural conditions, such as an increased lumbar curve, or as the result of training: for example, habitually rotating the pelvis forward to create the back bend.

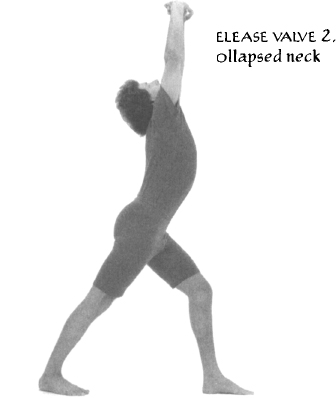

This again may be the result of individual structural conditions, such as weakness in the neck, or the result of training: for example, habitually initiating the backbend by pulling the spine with the head. This practice increases the risk of posterior strain and compression to the neck and, by giving the illusion of an intense backward bend, may also actually limit our efforts to work more deeply.

Bending in this way limits anterior stretching and increases the risk of posterior intervertebral disc compression and strain to the sacroiliac ligaments.

In backward bending, the cervical spine, like the lumbar, can arch deeply backward, creating a tendency to collapse the head backward.

The key to the thoraco-lumbar rhythm, and therefore all backward bends, is the technique of expanding the chest on inhale while maintaining the abdominal contraction initiated on exhale. At the initiation of the inhale expand the chest and lift the ribs, thereby lengthening the thoracic spine and stretching the front of the torso, and, as the chest expands, open the shoulders and pull them down and back. As the volume of air is reduced in the lungs on exhale, if you have a normal to excessive thoracic curve, in order to flatten it, contract the muscles of the upper back, pull the shoulders back, and push the mid-thoracic forward; or, if your thoracic curve is already flattened, focus on the vertical extension of the spine and avoid pushing the mid-thoracic forward. Then, on all successive inhales, maintain a slight abdominal contraction, in order to prevent excessive forward rotation of the pelvis and posterior lumbar intervertebral compression. And on the next and all successive exhales, use the increased abdominal contraction to stabilize the pelvic-lumbar relationship; focus the arching in the upper back; allow the head to rise away from the shoulders, creating as much space as possible between the cervical vertebrae; and keep the chin level, or even slightly tucked in, to enhance the lengthening of the cervical spine, lifting it only toward the end of the inhale in order to stretch the front of the neck and throat.

In the shoulders as well as the hips, the range of backward extension depends on many factors, including, with respect to the shoulders, the condition of the cervical and thoracic spine and their supporting muscles; and, with respect to the hips, the condition of the lumbar-pelvic structures and their supporting muscles.

When the arms and legs are used as levers to create the back arch, there is risk to the shoulder and hip joints. So, in order to avoid injury, we must be careful not to apply excessive muscular force in these cases. As we are able to open the chest and stretch the front of the abdomen and pelvis, we will minimize the risks to the shoulders and hips.

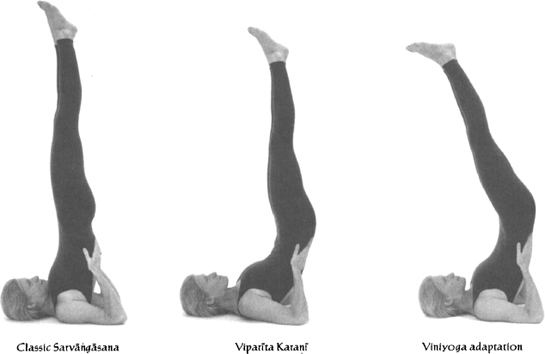

GROUP 1

GROUP 1The first group of postures includes open-frame back bends initiated from the prone position, which utilize primarily the contraction of the posterior muscles of the back (spinal extensor) and hips (hip extensors) to generate the back bend, aided in some cases by the backward extension of the arms. In these postures, the primary intention is the development of strength and resiliency in these muscles. Vimanāsana uniquely isolates and strengthens the muscles that support the sacroiliac joints.

The Viniyoga tradition gives special importance to these postures, which are relatively safe and universally beneficial, because they significantly strengthen the posterior musculature of the spine.

GROUP 2

GROUP 2This group of postures includes fixed-frame back bends, initiated from the knees or a prone position, which utilize the muscles of the back (spinal extensor) as well as the arms and shoulders to generate the back bend. In these postures, in order to deepen the arch initiated by the back muscles, the shoulders drop down and pull back, pushing the chest forward and up.

Cakravākāsana, which can equally be considered a forward bend, is one of the simplest and most universally useful postures in āsana practice. If you master this posture, you will have the key to practicing forward and back bending.

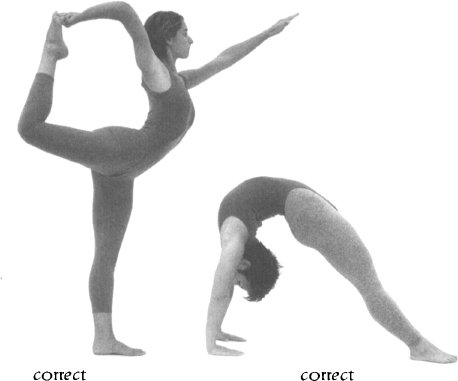

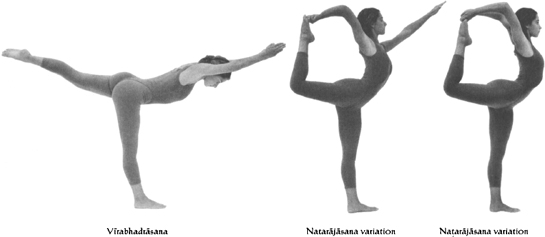

This group of postures includes standing and kneeling back bends that can be practiced as open-or close-frame postures. In addition to providing anterior stretching of the chest and abdominal areas, the asymmetric quality of these postures facilitates a deep stretching of the iliopsoas muscles. These muscles are often chronically contracted and can cause excessive anterior compression of the lumbar discs and low back pain. Asymmetric postures enable us to isolate and intensify the stretching of these important muscles, increasing their strength and flexibility.

Though Vīrabhadrāsana can be adapted to emphasize the iliopsoas muscles (see page 13), it is particularly useful for expanding the chest, stretching the intercostals and diaphragm, flattening the thoracic curve, and strengthening the hips and legs.

In the classical version of Ekapāda Ustrāsana, it is difficult to avoid excessive posterior lumbar compression. This adaptation reduces the risk to the lumbar while increasing the beneficial stretching of the iliopsoas and thighs.

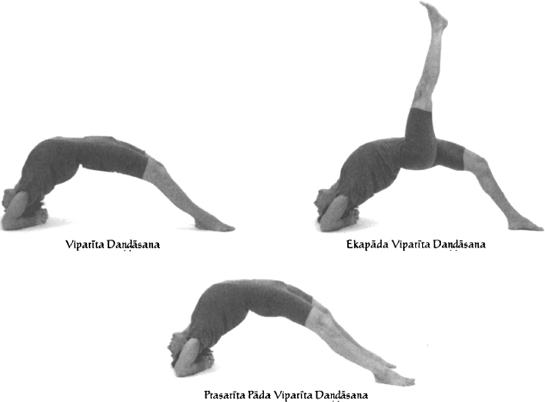

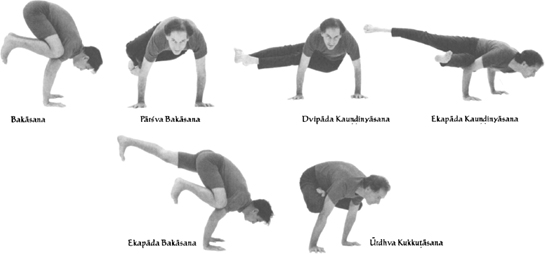

This group of postures includes fixed-frame back bends initiated from the supine (on the back), kneeling, or prone (on the stomach) positions, which utilize primarily the muscles of the arms, shoulders, legs, and hips to generate the arch. In all of these postures, because of the leverage generated by the arms and legs, deeper back bending is possible. This both increases the anterior stretching and the risk to posterior strain and compression.

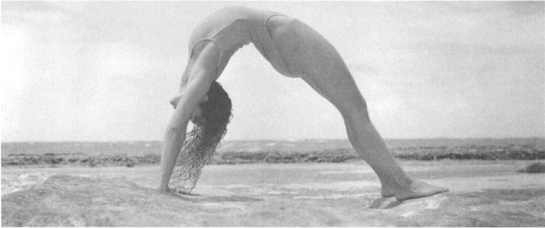

In most of these postures, the shoulders are dropped down, the shoulder blades are pulled back, the arms are at the sides, and the hands push against the floor or either pull the legs or are pulled by them. This action expands the chest, flattens the thoracic spine, and deepens the back arch. In Ūrdhva Dhanurāsana, however, the arms are raised over the head and extended behind the spine. If you can master this posture, you will experience the truly energizing and expanding quality of back bending.

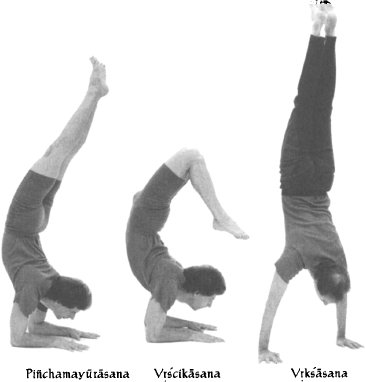

GROUP 5

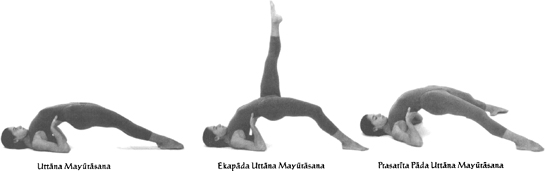

GROUP 5These are fixed-frame back bends in which the weight of the upper torso is supported by the top of the head. They are similar in form and function with respect to the upper torso and neck. Their primary intention is stretching the chest, the front of the neck, and throat, and strengthening the muscles of the upper back and back of the neck. In practicing these postures, press your head firmly down, engaging the muscles in the back of the neck and upper back to help expand the chest, and avoid collapsing your head backward.

Uttāna Pādāsana uniquely strengthens the iliopsoas muscles and stabilizes the pelvic-lumbar relationship.

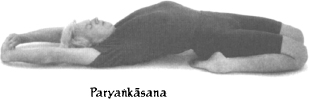

Paryankāsana is the sole member of this group. This fixed-frame posture deeply stretches the front of the thighs. The deep arching of the low back is created by the position of the legs rather than the action of the muscles.

In open- and fixed-frame back bends, there is the risk of lumbo-sacral and cervical strain, and excessive disc compression. Stabilizing the pelvic-lumbar relationship through the abdominal contraction on exhale minimizes this risk. In fixed-frame postures, such as Ustrāsana, Paryankāsana, and Uttānna Pādāsana, where there is a sharper angle between the lumbar spine and the pelvis, the risk is greater. If you have low back pain, your low back is weak, or you are very tight in the front of your thighs and pelvis, these postures should be avoided.

In back bends where the weight of the upper torso is supported on the top of the head, there is increased risk of strain to the cervical muscles and ligaments, as well as excessive disc compression. If your neck is weak, these postures should be avoided.

In Ūrdhva Dhanurāsana, there is risk of strain to the shoulder and wrist joints. Strengthening the shoulders and arms and maximizing the ability to expand the chest and stretch the abdomen will reduce the stress to the joints.

1.

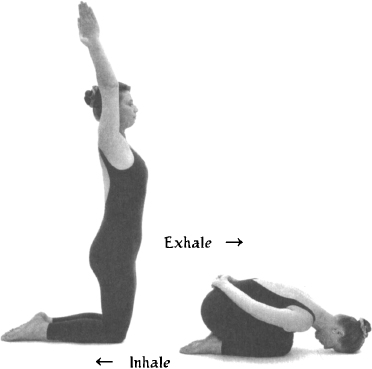

POSTURE: Vajrāsana.

EMPHASIS: To warm up body. To stretch low back.

TECHNIQUE: Stand on knees with arms over head.

On exhale: Bend forward, sweeping arms behind back, and bringing hands to sacrum, keeping palms up.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Bring chest to thighs before bringing buttocks to heels. Rotate arms so palms are up and hands are resting on sacrum. On inhale: Expand chest and lift it up off of knees as arms sweep wide.

2.

POSTURE: Vīrabhadrāsana.

EMPHASIS: To strengthen muscles of back and legs. To expand chest and flatten upper back. To increase hold after inhalation.

TECHNIQUE: Stand with left foot forward, feet as wide as hips and arms at sides.

On inhale: Simultaneously bend left knee, displace chest slightly forward and hips slightly backward, bringing arms out to sides and shoulders back.

After inhale: Hold breath 2, 4, and 6 seconds, 2 times each, progressively.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 6 times each side.

DETAILS: On inhale: Keep hands and elbows in line with shoulders. Feel opening of chest and flattening of upper back, not compression in low back. Keep head forward. Stay firm on back heel.

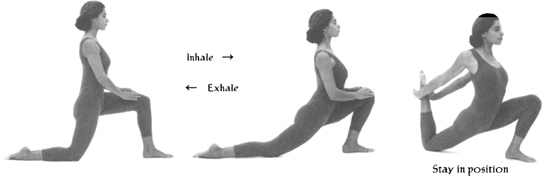

POSTURE: Ekapāda Ustrāsana variation.

EMPHASIS: To stretch musculature of upper thigh and iliopsoas.

TECHNIQUE: Stand on right knee, with knee directly below hip, and on left foot, with foot directly below left knee. Hands on left knee.

On inhale: Lift chest upward as you lunge forward, stretching front of body from right thigh to right side of abdomen.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

Repeat 4 times.

Then bend right knee and grasp ankle with both hands. Stay in position 6 breaths.

Repeat on other side.

DETAILS: While staying in the full posture, keep arms straight and push chest forward.

4.

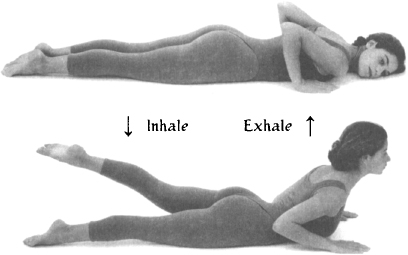

POSTURE: Ardha Śalabhāsana.

EMPHASIS: To strengthen and stabilize lower back.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on stomach, with head to left, and palms on floor by chest.

On inhale: Lift chest and left leg, turning head to center.

On exhale: Lower chest and leg, turning head to right.

Repeat on other side.

NUMBER: 6 times each side, alternately.

DETAILS: On inhale: Lift chest slightly before leg, and emphasize chest height. Keep pelvis level.

POSTURE: Adho Mukha Śvānāsana/Ūrdhva Mukha Śvānāsana.

EMPHASIS: To prepare shoulders, chest, and abdomen for Ūrdhva Dhanurāsana.

TECHNIQUE: Stand on hands and knees.

On exhale: Push buttocks upward, lifting knees off ground, and pushing chest toward feet. Stay 1 breath.

On inhale: Stretch body forward and arch back. Stay 1 breath.

On exhale: Return to previous position.

Repeat 6 times.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

DETAILS: On exhale: Keep knees bent, press chest toward feet, flattening upper back and stretching shoulders. Avoid hyperextension of shoulders. On inhale: Stay on toes. Keep shoulders down and back, pushing chest forward and stretching belly. Avoid collapsing pelvis and compressing low back.

6.

POSTURE: Vajrāsana.

EMPHASIS: To mobilize shoulders, releasing tension after previous posture, and to prepare for the back bend.

TECHNIQUE: Stand on knees with arms over head.

On exhale: Bend forward, sweeping arms behind back, and bringing hands to sacrum, keeping palms up.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Bring chest to thighs before bringing buttocks to heels. Rotate arms so palms are up and hands are resting on sacrum. On inhale: Expand chest and lift it up off of knees as arms sweep wide.

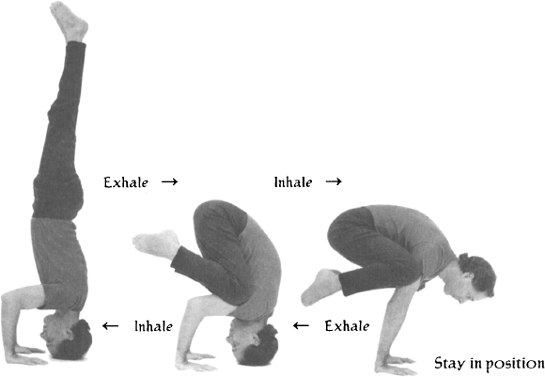

POSTURE: Ūrdhva Dhanurāsana.

EMPHASIS: To deeply stretch the front of torso. To experience a full and deep back bend.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with knees bent, feet on floor by buttocks, palms on floor under shoulders with fingers pointing toward feet.

On inhale: Press firmly on arms and feet, raising torso off ground, and create back bend.

Stay in position 6 breaths.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: Stay in full position 6 breaths, repeat 2 times.

DETAILS: First round: Work to straighten arms. Second round: Work to straighten legs.

8.

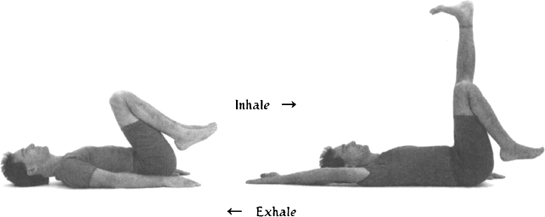

POSTURE: Supta Pādāngusthāsana.

EMPHASIS: To stretch and relax lower back after back bend.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with legs bent, knees lifted toward chest, hands holding thighs behind knee, and arms bent.

On inhale: Extend legs upward, straightening arms.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 6 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Flex feet as legs are raised upward. Slightly bend knees. Push low back and sacrum downward. Keep chin down.

9.

POSTURE: Dvipāda Pītham.

EMPHASIS: To relax neck after back bend.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with arms down at sides, knees bent, and feet on floor, slightly apart and comfortably close to buttocks.

On inhale: Pressing down on feet and keeping chin down, raise pelvis up toward ceiling, until neck is gently flattened on floor.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 6 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Lift spine, vertebra by vertebra, from bottom up. On exhale: Unwind spine, coming down vertebra by vertebra.

POSTURE: Paścimatānāsana.

EMPHASIS: To stretch back to compensate for back bend.

TECHNIQUE: Sit with legs forward, back straight, and arms raised over head.

On exhale: Bending knees slightly, bend forward, bringing chest to thighs and palms to balls of feet.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

Repeat 6 times.

Then stay in forward-bend position 6 breaths.

DETAILS: On exhale: Bend knees to facilitate stretching low back and bring belly and chest to thighs. Move chin down toward throat. On inhale: Lift chest up and away from thighs, flattening upper back.

11.

POSTURE: Śavāsana with support.

EMPHASIS: To rest.

TECHNIQUE: Lie flat on back, with arms at sides, palms up, and legs slightly apart. Close eyes. Relax body fully, keeping mind relaxed and alert to sensations in body.

DURATION: Minimum 3 to 5 minutes.

Twisting postures create rotation between the vertebral bodies of the spine, building strength and flexibility in the deep and superficial spinal and abdominal musculature and maintaining the elasticity of the intervertebral discs and ligaments. Twisting alternately compresses and stretches each hemisphere of the chest, stimulating respiratory function; alternately compresses and stretches the mid-torso, where the kidneys, adrenals, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, spleen, and stomach are located, stimulating their function; and alternately compresses and stretches the intestines, stimulating absorption, digestion, and elimination. In addition, twisting postures adjust the relationship between the shoulder and pelvic girdles and the spine, as well as strengthen and stretch the deep and superficial musculature that bind the head, the shoulders and arms, and the pelvis and legs to the spine. Where there is structural asymmetry in these areas, twisting helps to restore balance.

From a biomechanical perspective, according to the Viniyoga tradition, the primary intention of twisting is to rotate the spine.

The secondary intention of twisting is to adjust the relationship between the pelvic and shoulder girdles and the spine.

The key to twisting is the ability to control spinal rotation from the musculature of the abdomen and spine, rather than through the force of leverage generated by the musculature of the shoulders and arms and/or pelvis and legs. In twisting postures, this leverage can be applied, carefully, to augment the rotation of the spine but not to generate it.

The capacity for intervertebral rotation in the lumbar spine is limited. Twisting of the lower abdomen is therefore generated either by stabilizing the pelvis and rotating the spine, by stabilizing the spine and rotating the pelvis, or by rotating both in opposing directions.

The capacity for intervertebral rotation in the thoracic spine is greater than in the lumbar, particularly in the lower thoracic and in the thoraco-lumbar joint (see page 136). Twisting of the mid-torso is therefore generated either by stabilizing the pelvic-lumbar area and rotating the shoulder-thoracic area, by stabilizing the shoulder-thoracic area and rotating the pelvic-lumbar area, or by rotating both in opposing directions.

The cervical spine has the greatest capacity for intervertebral rotation, particularly at the atlas-axis joint (see page 143). Twisting of the neck is generated either by stabilizing the shoulders and rotating the head or by rotating both in opposing directions.

The key to spinal rotation, and therefore to all twisting postures, is the technique of abdominal contraction on exhalation. At the initiation of exhalation, contract the abdominal muscles at their insertion into the pubic bone, to stabilize the pelvic-lumbar relationship, and simultaneously initiate rotation. If you have a deep lumbar curve, pull the pubic bone slightly upward at the beginning of the twist to maximize the vertical extension of the spine. As the twist proceeds, continue the contraction of the abdominal muscles, from the pubic bone to the rib cage, emphasizing trunk rotation.

As with forward bends, the natural curve of the thoracic spine may create the tendency to collapse the rib cage over the belly as you twist. This can be avoided by lengthening between the chest and belly on inhale. With the lengthening of the spine, you will notice a natural “unwinding” of the twist, creating more space between the vertebrae. This will actually allow you to twist more deeply on the subsequent exhale.

GROUP 1

GROUP 1

The first group of postures includes standing and supine (on the back) open-frame twists, in which the shoulders and arms and the pelvis and legs have relative freedom of movement. These postures stretch and strengthen the large superficial muscles of the spine, shoulders, and pelvis. They also help bring balance to asymmetrical muscular development. If you are tight, muscle-bound, or overweight, you will be able to experience deep twisting in these open-frame postures. Some of these postures can be adapted as fixed-frame twists, where the hands hold the feet or the arms wrap around the legs.

In the standing postures, the pelvis is stabilized to emphasize rotation in the spine and shoulders. In the supine postures, the shoulders are stabilized to emphasize rotation in the spine and pelvis.

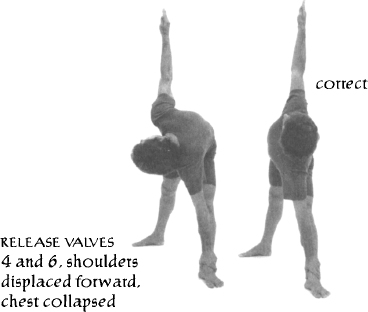

In these open-frame twists, we can control the location and intensity of the rotation, making these very simple postures profound in their effect. In the standing Parivrtti Trikonāsana, for example, by varying the position of the hand on the floor, we can influence where the primary spinal rotation is experienced. For example, when the hand is midway between the feet, the rotation is felt most between the shoulders, ribs, and upper back; and, as the hand moves progressively toward the opposite foot, the rotation is felt most in the hips, abdomen, and lower back.

A) classic postures:

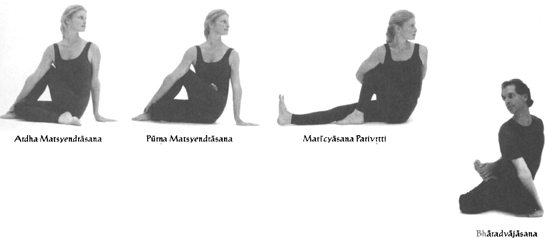

This group of postures includes seated fixed-frame twists in which the arms and legs are used as levers to deepen the spinal torsion. Though the leg positions vary, in all of these postures the pelvis is stabilized and the rotation occurs primarily in the spine and shoulders. Though the arm positions vary, they are used as levers to maximize the rotation of the spine and shoulders. In some postures, in addition to augmenting the rotation of the spine and shoulder girdle, the arms are used to displace one leg in the opposite direction, increasing the stretching of the muscles of that hip. The use of leverage significantly deepens spinal rotation, the activation of the deeper spinal muscles and ligaments, and the stretching of the muscles that bind the shoulders and pelvis to the spine.

In most of these postures, the head rotates in the same direction as the spine and shoulders. In Bhāradvājāsana, the head uniquely rotates in the opposite direction, increasing the stretching of the muscles of the neck. If you can master this special posture, you will discover the truly magical and powerful qualities of balance and integrity that accompany twisting.

B) useful variations:

In standing twists, the displacement of the pelvis or the internal rotation of the opposing thigh, knee, or foot in the direction of the twist reduces hip, spinal, and shoulder rotation. In supine twists, the lifting of the opposing shoulder in the direction of the twist likewise reduces hip, spinal, and shoulder rotation.

On the other hand, some displacement of the opposing structures may be helpful. If all displacement is blocked, rotation may be so restricted that no benefit is achieved. If you have tight hips, spinal muscles, and shoulders, and insist on restricting all internal rotation of the femur, knee, ankle, and foot in standing postures, you may be unable to create any significant twisting at all. If, in the supine postures, you hold the opposing shoulder firmly down on the floor, you may likewise be unable to effect any significant twisting. Where there is limited mobility, allowing some displacement will enable you to experience the twist and, in fact, achieve more of its benefits.

In twisting, the intervertebral discs are compressed. If there are any preexisting conditions of compression in the spine—for example an excessive thoracic and/or lumbar curve or excessive lateral spinal asymmetry—the possibility of injury to the discs increases. Risks can be minimized by adequate preparation, avoiding excessive force when using the arms and legs as levers, and lengthening the spine on inhalation while twisting.

There is also risk, in twisting postures, to the sacroiliac, hip, and knee joints. This is especially true in standing twists, where these joints are bearing weight, and in fixed-frame seated twists, where the arms and legs are used as levers. To reduce these risks in standing twists, keep the hip, knee, and ankle in vertical alignment, avoiding excessive internal or external rotation. In all twists, generate the rotation from the abdomen, rather than forcing the rotation with the leverage of the arms and legs.

1.

POSTURE: Uttānāsana.

EMPHASIS: To warm up back and legs.

TECHNIQUE: Stand with arms over head.

On exhale: Bend forward, bringing belly and chest toward thighs and bringing hands to feet.

On inhale: return to starting position.

NUMBER: 6 times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Bend knees to facilitate stretching of low back. Move chin down toward throat. On inhale: Lift chest up and away from thighs, flattening upper back. Keep knees bent until end of movement.

POSTURE: Parivrtti Trikonāsana.

EMPHASIS: To stretch legs, back, and shoulders.

TECHNIQUE: Stand with feet spread wider than shoulders and with arms out to sides and parallel to floor.

On exhale: Bend forward and twist, bringing left hand to floor, pointing right arm upward, and twisting shoulders right. Turn head down toward left hand.

On inhale: Maintaining rotation, and with right shoulder vertically above left, bring right arm up over shoulder and forward, turning head to center and looking at right hand.

On exhale: Return to previous position with right arm pointing upward. Turn head up, looking toward right hand.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

Repeat on other side.

NUMBER: 6 times each side, alternately.

DETAILS: Keep down arm vertically below its respective shoulder, and keep weight of torso off arm. Knees can bend while moving into twist.

3.

POSTURE: Cakravākāsana.

EMPHASIS: To make transition from standing to supine position. To stretch rib cage on inhale and low back on exhale.

TECHNIQUE: Get down on hands and knees, with shoulders vertically above wrists and with hips above knees.

On inhale: Lift chest up and away from belly.

On exhale: Gently contract belly, round low back, and bring chest toward thighs.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Lead with chest, keeping chin slightly down. Avoid compressing low back; rather, feel chest expanding. On exhale: Round low back without collapsing chest over belly. Avoid increasing curvature of upper back. Let chest lower toward thighs sooner than hips towards heels.

POSTURE: Ekapāda Rājakapotāsana variation.

EMPHASIS: To stretch hip rotator muscles in preparation for Bhāradvājāsana.

TECHNIQUE: Kneel on left knee and extend right leg straight behind you, hands on the floor on either side of right knee. Move right foot forward and toward left hand, displacing left knee further to left.

On inhale: Lift rib cage forward and up, while pulling down and back with hands, pushing chest forward, and flattening upper back.

On exhale: Bend elbows and lower chest toward floor. Stay down 2 breaths.

NUMBER: Repeat 4 times each side.

DETAILS: On inhale: Pull down and back with hands, rather than pushing up. Drop shoulders and pull shoulder blades back. On exhale: While staying in posture, adjust position of left foot to achieve maximum stretching of left hip.

5.

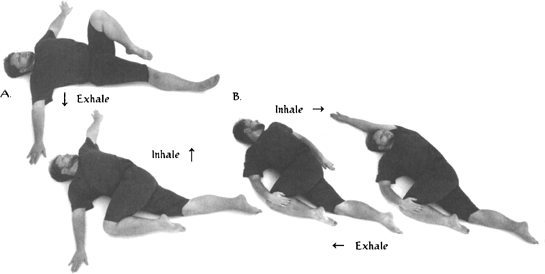

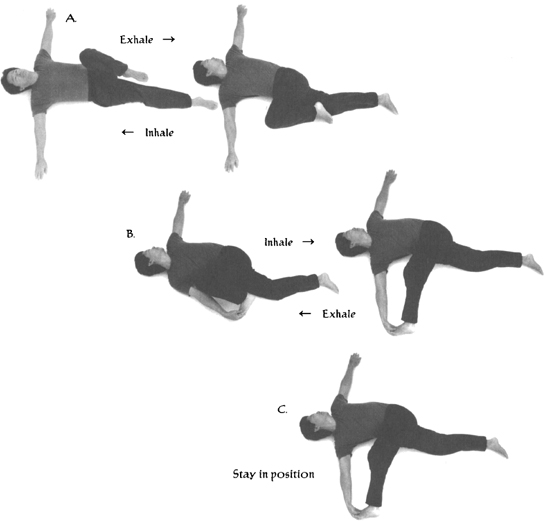

POSTURE: Jathara Parivrtti.

EMPHASIS: To stretch across hips and back, one side at a time.

TECHNIQUE: Lie flat on back, with arms out to sides, and with left knee pulled up toward chest.

A. On exhale: Twist, bringing left knee toward floor on right side of body, while turning head to left.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

Repeat 4 times.

B. Then stay in twist, holding left knee with right hand.

On inhale: With palm up, sweep left arm wide along floor toward ear, turning head to center.

On exhale: Lower arm back to side, turning head to left.

Repeat 6 times.

Repeat on other side.

DETAILS: On exhale: When twisting right, keep angles between left arm and torso and between left knee and torso less than ninety degrees.

B: Keep arm that is moving low to floor; palm up on inhale, palm down on exhale. Hold twisted knee low toward floor.

6.

POSTURE: Ūrdhva Prasārita Pādāsana.

EMPHASIS: To extend spine and flatten it onto floor. To stretch legs.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with arms down at sides, legs bent and knees held toward chest.

On inhale: Raise arms upward all the way to floor behind head, and raise legs upward toward ceiling.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

Repeat 6 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Flex feet as legs are raised upward. Keep knees slightly bent, and keep angle between legs and torso less than ninety degrees. Push low back and sacrum downward. Bring chin down.

7.

POSTURE: Bhāradvājāsana.

EMPHASIS: To experience one of the deepest and most complete spinal twists. To stretch the muscles that bind the head and neck to the spine.

TECHNIQUE: Sit with the right leg folded back, right foot on the floor to the right of right hip, and the left leg folded with left foot on upper right thigh. Wrap left arm behind back and grasp left foot, and place right palm down on floor on outside of left knee with fingers pointing toward right knee.

On inhale: Extend spine upward.

On exhale: Twist shoulders left and turn head right.

NUMBER: Stay 12 breaths each side.

DETAILS: Lean firmly on right palm, allowing right sit bone to lift off floor. On exhale: As you twist shoulders left and turn head right, focus on stretch on left side of neck.

POSTURE: Paścimatānāsana.

EMPHASIS: To stretch back to compensate for twist.

TECHNIQUE: Sit with legs forward, back straight, and arms raised over head.

On exhale: Bending knees slightly, bend forward, bringing chest to thighs, and palms to balls of feet.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

Repeat 4 times.

Then stay in forward bend position 6 breaths.

DETAILS: On exhale: Bend knees to facilitate stretching low back and bring belly and chest to thighs. Move chin down toward throat. On inhale: Lift chest up and away from thighs, flattening upper back.

9.

POSTURE: Śavāsana.

EMPHASIS: To rest.

TECHNIQUE: Lie flat on back, with arms at sides, palms up, and legs slightly apart. Close eyes. Relax body fully, keeping mind relaxed and alert to sensations in body.

DURATION: Minimum 3 to 5 minutes.

Lateral bends can be organized into two distinct classes. In the first class, the torso is bent to the side. These postures alternately stretch and compress the deep spinal muscles, the intervertebral ligaments and discs, the intercostal muscles and connective tissues that bind the ribs together, and the deep and superficial muscles that bind the shoulder and pelvic girdles to the spine. They build strength and stability in the musculature of the spine, rib cage, shoulders, and pelvis; they help maintain the elasticity of the rib cage; and they help restore balance to asymmetries of the spine, shoulders, and pelvis. In addition, these postures alternately stretch and compress the lungs and organs of the torso—such as the kidneys, liver, and intestines—and thus stimulate their function.

In the second class of lateral bends, one leg is abducted and rotated outward. These postures stretch the structures of the pelvis, groin, inner thigh, and perineal area, building strength and flexibility in the muscles in these areas. In addition, they increase circulation to the perineal floor and stimulate the function of the reproductive organs. In these effects, they are related to the forward bends with legs spread wide (see Group 4).

From a biomechanical perspective, according to the Viniyoga tradition, the primary intention of the first class of lateral bends is to laterally stretch the torso from the shoulder to the hip joint, and to laterally flex the spine. The secondary intention is to stretch and strengthen the musculature of the shoulder girdle, hip joints, front of the pelvis, and inner thighs.

In the second class of lateral bends, the emphasis is nearly reversed. The primary intention is to strengthen and stretch the musculature of the front of the pelvis, hip joints, groin, and inner thighs—these actions are collectively referred to as “pelvic opening.” The secondary intention is to stretch the lateral portions of the torso and the structures of the shoulder girdle.

The capacity for pure lateral flexion of the spine is limited and, therefore, is rare in daily activity. Think of pulling over to the curb in your car to talk to a friend on the street. Imagine reaching over to roll down the window on the passenger side with your right hand. The normal tendency is for your hips to displace backward and rotate right as your chest and shoulders displace forward and rotate right. Now imagine keeping your back and shoulders flat against the seat while bending sideways to roll down the window. This is a pure lateral bend.

If you restrict displacement and rotation, you will significantly limit your range of motion, but you will maximize lateral flexion, and herein lies the potential benefit of lateral bends.

Accordingly, the key to these postures is the ability to control the proportional relationship between pure lateral bending and the natural displacement and rotation described above. And the key to this control is the combined techniques of exhale and inhale.

At the initiation of exhale, contract the abdominal muscles to check the forward rotation of the pelvis, and lengthen the lumbar spine, while simultaneously initiating the lateral bend. If you have a deep lumbar curve, pull the pubic bone slightly upward to check backward displacement of the pelvis. On subsequent exhalations, rotate the top shoulder slightly backward, keeping the shoulders in vertical alignment, to help maintain the lateral quality of the movement. On inhale, lengthen the spine, pull the chest up and away from the belly, pull the shoulders down and back, and flatten the thoracic curve, as in a backward bend. Lengthening the spine creates more space between the vertebrae, increasing the potential for lateral flexion without compressing the intervertebral discs. This action also inhibits the tendency to displace the chest and shoulders forward and helps prevent lateral intervertebral compression. Extending the arm, on the side being stretched, up over the head and forward on inhale increases the stretching of the musculature and connective tissues of the rib cage and torso. To maximize this effect, keep your arm in line with your shoulder and torso.

GROUP 1

GROUP 1The first group of postures includes standing and kneeling lateral bends where the primary effect is lateral stretching of the torso and the secondary effect is pelvic opening. In these postures, the pelvis and shoulder girdle are free to rotate and/or displace as the trunk bends laterally. Though this allows for more range of motion, it reduces the lateral stretching. These postures can be practiced either as open-or fixed-frame postures. In fixed-frame variations, the leverage created by the arms blocks the forward rotation and displacement of the shoulders, deepening the lateral stretching of the torso.

In standing postures, the foot and knee on the side of the bend is turned out at a ninety-degree angle, rotating the leg outward at the hip. The opposite hip and leg remain stabilized in a forward direction. This creates a spreading of the hip bones and a stretching across the front of the pelvis that is similar though less than that created by pelvic openers.

The kneeling lateral bend is the deepest of the lateral stretches. If you can master this posture, you will truly experience the powerful and expanding quality of lateral bends.

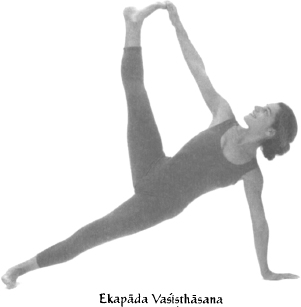

This group includes two postures where the primary effect is lateral stretching of the torso, and where the pelvic opening effect is absent (except in some difficult variations of Vaśisthāsana). They are both open-frame postures.

In the supine posture, the stretching is primarily in the hip and lower lateral muscles of the torso.

In Vaśisthāsana, which is also a balance posture, the stretching is primarily in the intercostal muscles and the large latissimus dorsi muscles, which attach from the spine across the ribs to the arm. Further adapations of Vaśisthāsana can be found ahead in the section on balance.

GROUP 3

GROUP 3This group of postures includes seated lateral bends, where the primary effect is lateral stretching of the torso. As these postures are seated, the backward displacement of the pelvis is restricted, resulting in a significant forward-bend component. Paścimatānāsana Parivrtti is a deep, fixed-frame lateral stretch with strong forward bend and twisting elements.

The different leg positions in the three lateral adaptations of the asymmetric forward bends determine the degree of lateral displacement of the pelvis and thus the depth of the lateral stretching of the torso. These postures can be practiced either as open- or fixed-frame postures.

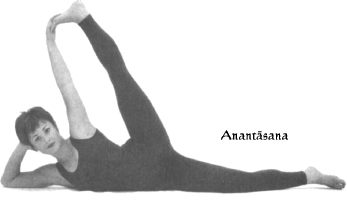

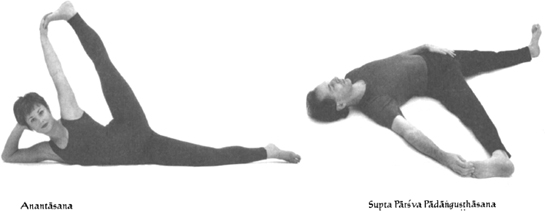

In these two fixed-frame postures, the primary effect is pelvic opening. In these postures, one hand holds the foot on the same side and one arm is used to extend and stretch the same leg. Because excessive stretching may compromise the stability of the hip or sacroiliac joints, we suggest that the primary action be generated by the leg, letting the arm guide rather than pull the leg. In Anantāsana, there is some secondary stretching of the lateral musculature of the lower torso on the opposite side.

GROUP 5

GROUP 5These two challenging seated postures primarily focus on stretching the deep and superficial muscles that bind the legs to the pelvis. They also stretch deeply the posterior and lateral muscles of the low back. They are particularly risky if there is weakness or instability in the hip or sacroiliac joints. With the leg behind the head, Ekapāda Śirsāsana (not shown) is also risky for the knee and the neck.

In all lateral postures, there is a risk of stress to the sacroiliac, hip, and knee joints. This is especially true in standing and kneeling postures that are weight-bearing, and in standing, kneeling, and seated fixed-frame postures that use the arms as levers to deepen the lateral stretch. Keeping the hip, knee, and ankle in vertical alignment and avoiding excessive internal or external rotation will minimize risks to these joints.

There is a risk of stress to the shoulder joint in fixed-frame standing, kneeling, and seated postures if you strain to grasp the opposite foot with the hand of the extended arm. If you are tight, maintaining the vertical alignment of your shoulders, keeping the extended arm in alignment with the torso, will actually give you a more effective stretch.

The risk of excessive lateral intervertebral compression in both open- and fixed-frame lateral bends is minimized by lengthening the spine on inhale before you bend, and with each successive inhale while in the posture.

1.

POSTURE: Vajrāsana.

EMPHASIS: To warm up body, gently stretching back, one side at a time.

TECHNIQUE: Stand on knees with left arm over head and right arm folded behind back.

On exhale: Bend forward, pushing left arm forward and bringing chest to thighs and hand and forehead to floor.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 4 times each side, one side at a time.

DETAILS: On exhale: Bring chest to thighs before bringing buttocks to heels. On inhale: Lift chest and arm, flattening upper back upon return.

2.

POSTURE: Ardha Pārśvottānāsana.

EMPHASIS: To stretch and strengthen low back, one side at a time.

TECHNIQUE: Stand with left foot forward, right foot turned slightly outward, right arm over head, and left arm folded behind back.

On exhale: Bend forward, flexing left knee, bringing chest toward left thigh, and right hand to left foot.

On inhale: Lift chest and arm until torso is parallel to ground.

On exhale: Return to forward bend position.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 4 times each side.

DETAILS: Stay stable on back heel and keep shoulders level throughout movement.

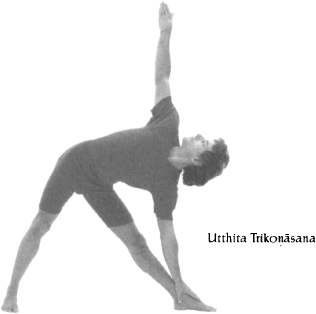

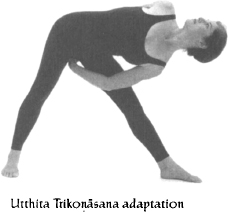

POSTURE: Utthita Trikonāsana.

EMPHASIS: To laterally stretch torso and rib cage.

TECHNIQUE:

A: Stand with feet spread wider than shoulders, left foot turned out at a ninety-degree angle to right foot, left arm over head, and right arm straight down at waist and slightly rotated externally.

On exhale: Keeping shoulders in same plane as hips, bend laterally, lowering left shoulder and bringing left hand below left knee while turning head down toward left hand.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

Repeat.

B: With left hand down along left leg:

On inhale: Bring right arm up and forward while turning head forward toward right hand.

On exhale: Return right hand to starting position while turning head down toward left hand.

Repeat.

C: With left hand down along left leg, wrap right arm behind back and left arm under inside of left leg. Clasp hands behind back and turn head down toward left foot.

NUMBER: Repeat A four times, then B four times, and then stay in C six breaths. Repeat on other side.

POSTURE: Vajrāsana.

EMPHASIS: To stretch back symmetrically. To transition from standing to supine position.

TECHNIQUE: Stand on knees with arms over head.

On exhale: Bend forward, sweeping arms behind back, bringing hands to sacrum, palms up.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Bring chest to thighs before bringing buttocks to heels. Rotate arms so palms are up and hands are resting on sacrum. On inhale: As arms sweep wide, open chest, pull shoulder blades back, and flatten upper back.

5.

POSTURE: Jathara Parivrtti variation.

EMPHASIS: To gently stretch torso laterally.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with legs straight, and arms flat and at a small angle from sides.

Walk both feet in small increments to left until right side of lower torso and hip are gently stretched. Raise right arm up over head.

Stay and breathe deeply, gently protruding belly on inhale.

Return to starting point.

Repeat on other side.

NUMBER: Stay 8 deep breaths each side.

DETAILS: GO only as far with legs as allows low back and hips to stay stable on floor. Avoid increasing arch of low back.

POSTURE: Ūrdhva Prasārita Pādāsana, one side at a time.

EMPHASIS: To gently stretch low back and to stretch legs, emphasizing one side at a time.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with both knees lifted toward chest, feet off floor.

On inhale: Extend left leg upward, raising right arm up and over head to floor behind you.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

Repeat on other side.

NUMBER: 6 times each side, alternately.

DETAILS: On inhale: Flex foot as leg is raised upward. Knee can remain slightly bent. Low back and sacrum push downward. Chin is down.

7.

POSTURE: Paścimatānāsana.

EMPHASIS: To stretch back. To prepare for Jānu Śirsāsana Parivrtti.

TECHNIQUE: Sit with legs forward, back straight, and arms raised over head.

On exhale: Bending knees slightly, bend forward, bringing chest to thighs, and palms to balls of feet.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

Repeat 6 times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Bend knees to facilitate stretching low back and bring belly and chest to thighs. Move chin down toward throat. On inhale: Lift chest up and away from thighs, flattening upper back.

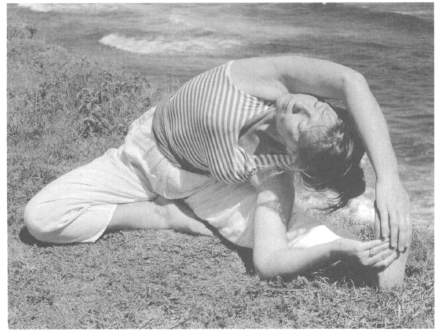

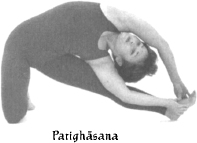

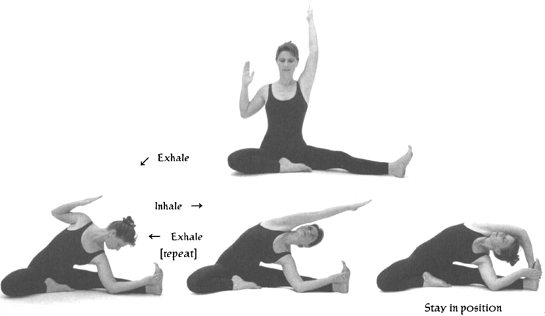

POSTURE: Jānu Śirsāsana Parivrtti.

EMPHASIS: To deeply stretch lateral portion of torso, one side at a time. To prepare for Parighāsana.

TECHNIQUE: Sit with right leg folded in, heel to groin, left leg extended forward at an angle, left arm overhead, and right arm bent as shown.

On exhale: Bending left knee slightly, bend laterally, bringing left hand toward left foot, keeping shoulders twisted so right shoulder is vertically above left, and turning head down toward left knee. Place right palm above right shoulder.

On inhale: Extend right arm forward, stretching right side of torso, and look toward right hand.

On exhale: Bend right arm again, turning head down toward knee.

Repeat 4 times.

Then stay in the full stretch 4 breaths.

Repeat on other side.

DETAILS: Bend left knee enough to comfortably lower left shoulder toward knee. Rotate left hand externally to grasp inside arch of left foot. Keep shoulders in vertical alignment. In full position, if possible, grasp left foot with right hand.

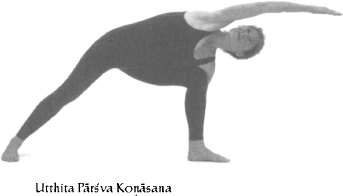

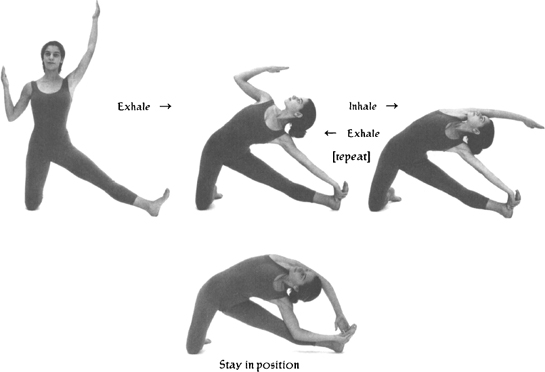

POSTURE: Parighāsana.

EMPHASIS: To deeply stretch lateral portion of torso, one side at a time. To experience one of the deepest lateral bends.

TECHNIQUE: Stand on right knee with left leg straight and extended out to left side and left arm over head.

On exhale: Bend laterally, placing left hand on left foot, keeping shoulders twisted so right shoulder is vertically above left, and turning head up over the right shoulder. Place right palm above right shoulder.

On inhale: Extend right arm forward, stretching right side of torso, and look toward right hand.

On exhale: Bend right arm again, turning head up over the right shoulder.

Repeat 4 times.

Then stay in the full stretch 6 breaths.

Repeat on other side.

DETAILS: Rotate left hand externally to grasp inside arch of left foot. Keep shoulders in vertical alignment. In full position, if possible, grasp left foot with right hand.

POSTURE: Vajrāsana.

EMPHASIS: To stretch back symmetrically after deep lateral bend.

TECHNIQUE: Stand on knees with arms over head.

On exhale: Bend forward, sweeping arms behind back, bringing hands to sacrum, palms up.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Bring chest to thighs before bringing buttocks to heels. Rotate arms so palms are up and hands are resting on sacrum. On inhale: As arms sweep wide, open chest, pull shoulder blades back, and flatten upper back.

11.

POSTURE: Śavāsana.

EMPHASIS: To rest.

TECHNIQUE: Lie flat on back, with arms at sides, palms up, and legs slightly apart. Close eyes. Relax body fully, keeping mind relaxed and alert to sensations in body.

DURATION: Minimum 3 to 5 minutes.

In anatomical parlance, extension refers to moving the spine, arms, or legs backward, or staightening them from a flexed position. In the context of this study, however, extension refers to lengthening and straightening the spine, creating maximum space between the vertebral bodies and integrating the spinal curves. Lengthening the spine enables us to move more deeply in forward bends, back bends, twists, and lateral bends, and their practice results in a more naturally lengthened spine. Thus, from a biomechanical perspective, extension is both the means and the goal of āsana practice. In this sense, all postures can be considered extension postures.

In this category, then, we find postures in which the most significant movement of the spine is extension, and any forward, backward, twisting, or lateral movement is minimized. Though movement in these postures is limited, they build strength and elasticity in the superficial and deep musculature, ligaments, and connective tissues of the spine and rib cage. They also strengthen the diaphragm and abdominal muscles. Through these combined effects, extension postures help us improve our postural alignment and overall structural integration. Improved postural alignment reduces stress to the musculature and organs of the torso and improves digestion, respiration, and circulation.

Some extension postures also stretch the arms and/or legs away from the torso, facilitating the extension of the spine, stretching and strengthening the muscles and ligaments that bind them to the spine, creating more space in the shoulder and hip joints. This action also improves peripheral circulation.

Extension postures are at the same time the simplest and most challenging of all postures. Try sitting still with a focused mind and an extended spine, following the movement of inhale and exhale, for several minutes.

After some time you may begin to feel resistance, tightness, and discomfort in your back, neck, shoulders, hips, and/or knees. The discomforts experienced in this simple extension posture reveal imbalances in your structure. In this sense, simple extension postures can be used as diagnostic tools, giving direction to the use of forward bends, back bends, twists, and lateral bends in āsana practice. A sign of progress is the ability to remain in simple extension postures for longer periods of time with less stress. Then more attention can be given to subtler aspects of the spine, breath, and energy, and to experiencing the centering and stilling qualities of extension postures.

From a biomechanical perspective, the primary intention in extension postures is to bring the spine to maximum vertical alignment, integrating the spinal curves without strain or compression.

The secondary intention is to extend the arms and legs, augmenting the extension of the spine, creating space in the shoulder and hip joints and improving circulation.

The natural curvatures of the spine serve an important biomechanical purpose, and, therefore, a straight spine is neither possible nor desirable. Beyond these natural curves, however, we all have some irregularities in our spine. One or another of the curves may be exaggerated or flattened, in any combination. Besides irregularities of the natural spinal curves, there is also almost always some degree of lateral asymmetry. These spinal conditions are accompanied by asymmetrical conditions in the deep and superficial musculature and ligaments of the torso, shoulder, and pelvic girdles.

The spinal curves move in reciprocal relation to each other. Theoretically, lengthening the cervical spine should lengthen the thoracic spine, which should, in turn, lengthen the lumbar spine. In practice, however, lengthening the thoracic curve often increases the lumbar curve, and flattening the lumbar curve often increases the thoracic curve.

The key to integrating the spinal curves, and therefore the key to extension postures, is the combined techniques of inhale and exhale. Initiate the inhale in the upper portion of the chest, emphasizing the natural lifting and expansion of the rib cage that takes place as the lungs fill with air. Tuck the chin slightly in and displace the head slightly backward, to lengthen the neck, as the chest expands and upper ribs lift forward and up. At the same time, the upper thoracic spine begins to straighten. Let the upward and outward movement of the ribs move successively from rib to rib, from the top downward, until the entire rib cage is fully expanded. As this happens, the thoracic spine lengthens vertebra by vertebra, from the top down. If your thoracic curve is exaggerated, displace your chest slightly forward to flatten the curve as you lift and lengthen the spine. If, on the other hand, your thoracic spine is flattened, focus on extending the spine without pushing your chest forward. As the air is drawn into the lungs, follow the downward movement of the diaphragm to the abdomen and lengthen the lumbar spine. If your lumbar curve is reversed, rotate your pelvis forward to regain the natural curve and facilitate the lengthening of the spine. If your lumbar curve is exaggerated, use the abdominal contraction, at the initiation of exhale, to pull the pubic bone upward and to flatten the lumbar spine. On exhale, as the diaphragm moves upward, keep the chest lifted, pull the shoulders down and back, and increase the extension of the spine. Maintain a partial contraction of the lower abdomen through successive inhales, stabilizing the lumbar-pelvic relationship, increasing the lift of the rib cage, and furthering the extension of the spine.

GROUP 1

GROUP 1

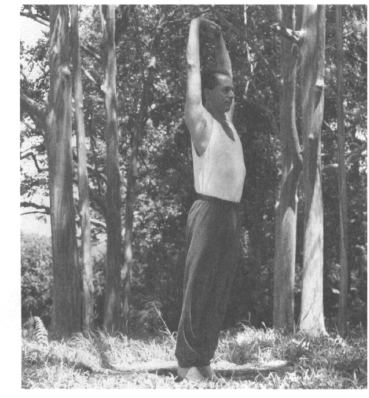

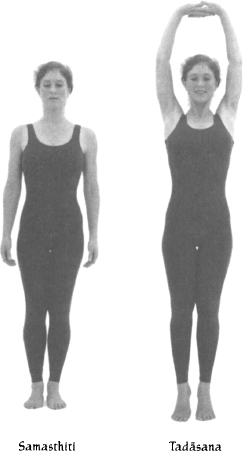

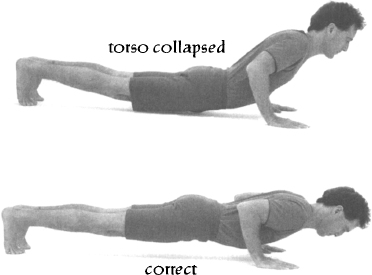

The first group includes postures where the torso and legs are flat and extended. The first two are standing postures. Raising the heels up off the ground gives Tādāsana some of the qualities of a balance posture. The next two are supine postures. The intention of Śavāsana is to deeply rest, and, therefore, the challenge is to simply “let go” of doing, rather than extending the spine. Tadākamudrā incorporates a special technique of pulling the belly in and up, while expanding and lifting the rib cage and holding the breath out after exhale. In Caturanga Dandāsana, the only fixed-frame posture of this group, the legs and torso are held parallel above the ground on the hands and balls of the feet. This requires strength in the belly and low back as well as in the legs and shoulders.

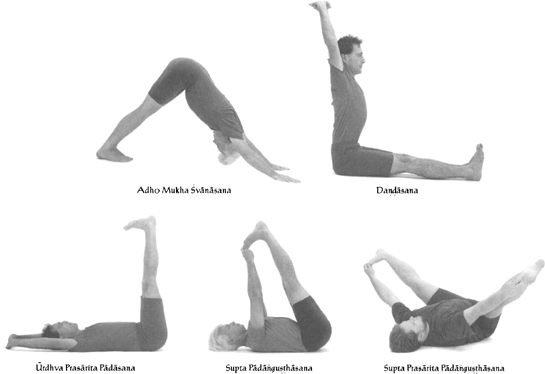

Adho Mukha Śvānāsana, Dandāsana, and Ūrdhva Prasārita Pādāsana have nearly identical forms, with different bases, though only Adho Mukha Śvānāsana is fixed-frame. In all of these postures, the torso is held at ninety degrees to the legs, giving the postures a quality of forward bending. At the same time, the chest is lifted up and away from the belly, stretching in the front of the abdomen, giving them a quality of back bending.

In the supine postures, extending the arms and legs and flattening the cervical and lumbar spine into the floor makes these simple postures surprisingly effective. To get maximum extension in the spine, keep the legs at ninety degrees or less to the torso, even if the knees have to be bent, and push the lumbo-sacral spine down.

These postures include two classical fixed-frame variations in which the hands hold the feet. In the second, Supta Prasārita Pādāngusthāsana, the legs are spread wide, stretching the insides of the thighs and perineal floor.

In Adho Mukha Śvānāsana and Dandāsana either excessive tightness or looseness in the hips and/or shoulders, as well as excessive or flattened curvature in the lumbar and/or cervical spine will complicate and inhibit extension. Adho Mukha Śvānāsana is one of the more complex postures, due to the variety of angles possible at the ankle, knee, hip, and shoulder joints. In this posture, integrating the spinal curves and extending the spine is challenging and requires sensitivity and control. The shoulder joints may be strained in this position. In Dandāsana, extension requires strength in the thighs, abdomen, and low back. The lumbo-sacral spine may be strained in this posture.

GROUP 3

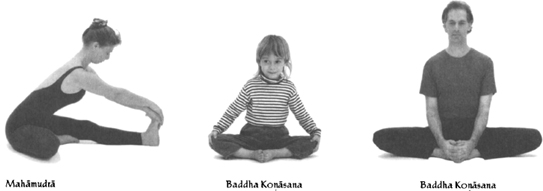

GROUP 3These seated fixed-frame postures are challenging. Mahāmudrā is considered, in the Viniyoga tradition, to be the most extraordinary of postures. In it are contained elements of forward bending, backward bending, twisting, and lateral bending. If you practice Mahāmudrā, you will experience the powerful, integrating, and stilling quality of extension postures. Baddha Konāsana, with the soles of the feet together, blocks the forward rotation of the hips, making full extension of the spine very challenging. It strongly stretches the inner thighs and groin.

The postures in this group are the classic seated meditation postures. Though extension is their primary characteristic, these postures are distinctly different from other āsanas. Their intention is to provide a balanced position in which the spine can be held in an extended position for long periods of time with minimum effort, so that the attention is freed from structural tensions and can focus on subtler aspects of the breath and meditation.

Padmāsana, the classic mediation posture, and Gomukhāsana involve significant external rotation of the legs at the hip joints and some torque of the knees. In Vīrāsana, the legs are inwardly rotated at the hip joints, and there is also some torque in the knees. In Vajrāsana, there is a tendency toward increased forward rotation of the pelvis.

In seated extension postures, there is risk of strain to the musculature of the lumbo-sacral spine, strain to the sacroiliac ligaments, and excessive intervertebral disc compression. Where the hips are rotated externally or internally, there is risk of strain to the hips and knee joints. There is also the possibility of strain to the musculature of the upper back, shoulders, and neck. In Adho Mukha Śvānāsana, there is added risk of strain to the shoulder joints.

Risks can be minimized by initiating movement from the deeper musculature with the breath and by avoiding forcing the spine with other muscles. This is especially true in fixed-frame postures. Extra caution should be taken to avoid excessive force to the shoulders in Adho Mukha Śvānāsana and to the hips and knees in some of the seated meditation postures.

1.

POSTURE: Ardha Pārśvottānāsana.

EMPHASIS: To stretch and strengthen low back, one side at a time.

TECHNIQUE: Stand with left foot forward, right foot turned slightly outward, both arms over head.

On exhale: Bend forward, flexing left knee, bringing chest toward left thigh, and hands to either side of left foot.

On inhale: Lift chest and arms until torso is parallel to ground.

On exhale: Return to forward bend position.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 4 times each side.

DETAILS: Stay stable on back heel and keep shoulders level throughout movement.

2.

POSTURE: Adho Mukha Śvānāsana.

EMPHASIS: To flatten upper back and stretch legs. To transition from standing to prone position.

TECHNIQUE: Get down on hands and knees.

On exhale: Push buttocks upward, lifting knees off ground and pushing chest toward feet. Stay 1 breath.

On inhale: return to starting position.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Keep knees bent as needed, press chest toward feet, flatten upper back, and avoid hyperextension of shoulders.

POSTURE: Ardha Śalabhāsana.

EMPHASIS: To strengthen lower back. To prepare for Mahāmudrā.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on stomach, with head facing left, and palms on floor by chest.

On inhale: Lift chest and left leg, turning head to center.

On exhale: Lower chest and leg, turning head to right side.

Repeat on other side.

NUMBER: 6 times each side, alternately.

DETAILS: On inhale: Lift chest slightly before leg, and emphasize chest height. Keep pelvis level.

4.

POSTURE: Supta Pādāngusthāsana.

EMPHASIS: To stretch legs and back in preparation for Mahāmudrā.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with legs bent, knees lifted toward chest, hands holding toes of feet.

On inhale: Extend legs upward, straightening arms.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 6 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Flex feet as legs are raised upward. Bend knees slightly. Push low back and sacrum downward. Keep chin down.

POSTURE: Jathara Parivrtti.

EMPHASIS: To twist and compress belly. To stretch legs. To facilitate exhalation.

TECHNIQUE:

A: Lie flat on back, with arms out to sides, and with left knee pulled up toward chest.

On exhale: Twist, bringing left knee toward floor on right side of body while turning head to left.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

Repeat 4 times.

B: Then stay in twist, holding left foot with right hand.

On inhale: Extend left leg.

On exhale: Bend left leg.

Repeat 4 times.

C: Then stay in full twist 4 breaths.

Repeat A, B, and C on other side.

DETAILS: B: On inhale, straighten leg from hip, using hand to guide foot.

POSTURE: Jānu Śirsāsana and Mahāmudrā combination.

EMPHASIS: Jānu Śirsāsana: to stretch lower back and legs; to prepare for Mahāmudrā; after Mahāmudrā, to relax back and rest.

Mahāmudrā: to strengthen musculature of torso; to deepen breathing capacity; to experience one of the deepest extension postures.

TECHNIQUE: Sit with right leg folded in, heel to groin, left leg extended forward and arms over head.

On exhale: Bend forward, bringing belly and chest toward left leg and bringing hands to left foot.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

Repeat 4 times.

Then: On inhale: Extend spine upward, expanding chest, flattening upper back, and lengthening front of torso. Hold breath after inhale one half the length of inhale.

On exhale: Maintain posture while pulling upward from perineal floor and pulling belly firmly in. Sustain for one half the length of exhale.

Repeat 8 times.

Then stay down in forward bend position for 4 breaths.

Repeat on other side.

DETAILS: While in Mahāmudrā: On inhale, lift chest slightly, extending spine; on exhale, tighten belly, maintaining extended spine.

7.

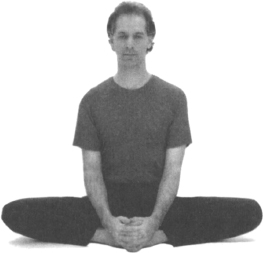

POSTURE: Baddha Konāsana.

EMPHASIS: To stretch area of inner thighs and groin.

To balance hips after Mahāmudrā.

TECHNIQUE: Sit with soles of feet together, heels close to groin.

On inhale: Holding feet with both hands, extend spine upward, flattening upper back.

On exhale: Pull upward from perineal floor, and pull belly firmly in.

Repeat 8 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Expand chest, then gradually release first belly and then perineal floor.

POSTURE: Dvipāda Pītham.

EMPHASIS: To relax upper and lower back, and to stretch between belly and thighs.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with arms down at sides, knees bent, feet on floor, slightly apart and comfortably close to buttocks.

On inhale: Press down on feet, raising pelvis up toward ceiling, keeping chin down, until neck is gently flattened on floor.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 6 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Lift spine, vertebra by vertebra, from bottom up. On exhale: Unwind spine, coming down vertebra by vertebra.

9.

POSTURE: Śavāsana.

EMPHASIS: To rest.

TECHNIQUE: Lie flat on back, arms at sides, palms up, and legs slightly apart. Close eyes. Relax body fully, keeping mind relaxed and alert to sensations in body.

DURATION: Minimum 3 to 5 minutes.