A simple model of leadership may be a list of different types of leaders grouped according to one or more characteristics about them. Taxonomy classifies them according to their mutual relationships, similarities, and differences. The model or taxonomy describes but does not explain the relationships, as would a theory. U.S. presidents, state governors, and city mayors form a threefold taxonomy If the three categories are divided into Republican and Democratic, we obtain a more complex sixfold classification or taxonomy of Republican and Democratic presidents, governors, and mayors. This classification can be used to show how the different types of political leaders react, say, to pressures from their respective constituencies. A taxonomy is formed. Taxonomies are classifications in an ordered arrangement of types.

After defining leadership, earlier scholars usually developed a handy classification. This was either a simple typing of leaders or a multilayered taxonomy with formal rules for classifying the leaders by their roles, perceptions, cognitions, behaviors, traits, characteristics, qualities, and abilities. In The Republic, Plato offered three types of leaders of the polity: (1) the philosopher-statesman, to rule the republic with reason and justice; (2) the military commander, to defend the state and enforce its will; and (3) the businessman, to provide for citizens’ material needs and to satisfy their lower appetites. This early taxonomy has been followed by a long line of taxonomies of leadership, some of which are probably being formulated at this moment by popularizers of the subject for sale in airport bookstores or for presentation in the popular press. A respite from new leadership typologies is unlikely in the foreseeable future, for although typologies lack rigor, they are appealing, convenient, and easy to discuss, comprehend, and remember.

One typology that continues to survive is formal versus informal leaders. Formal leaders are in positions that provide them with legitimacy and the power to lead. Informal leaders influence others as a consequence of their personal attributes and the esteem they are accorded. Compared with formal leaders, informal leaders are seen to be somewhat more communicative, relations-oriented, authentic, and self-confident (Pielstick, 2000). Informal leaders may emerge in newly formed small groups without structure—in street gangs, in small groups of friends, and in organizations independently of their positions (Bryman, 1992).

Different types of leaders have been studied. Many attempts have been made to extrapolate conclusions from one special type of leader and organization studied to leadership in general. The types of leaders studied have included task and team leaders as well as emergent, elected, or appointed small-group leaders. Early on, leaders of informal crowds and demonstrations were described. Some of the leaders studied in larger organizations have included college presidents, chief executive officers, military officers, school principals, student leaders, technical leaders, hospital and nursing administrators, and religious leaders—and have included leaders of revolutionaries, juvenile delinquents, criminals, and terrorists. Managers at all levels of business and industry, consumer-opinion leaders, work teams, minority leaders, women leaders, public officials, athletic leaders, child and adolescent leaders, leaders of social movements, political leaders, and administrators at all levels of various public agencies and private institutions have also been considered. Taxonomies have been created within and among these types.

Leaders of small groups have been classified in many ways, according to their different functions, roles, and behaviors. Pigors (1936) observed that leaders in group work tend to act either as masters or as educators. Cattell and Stice (1954) identified four types of leaders in experimental groups: (1) persistent, momentary problem solvers, who have a high rate of interaction; (2) salient leaders, who observers think exert the most powerful influence on the group; (3) sociometric leaders, who are nominated by their peers; and (4) elected leaders. Bales and Slater (1955) observed that the leader performs two essential functions; the first is associated with productivity, and the second is concerned with the socioemotional support of the group members.

Benne and Sheats (1948) proposed that group members who exert leadership play three types of functional roles: (1) group-task roles, such as initiator, gatekeeper, and summarizer; (2) group-building and group-maintenance roles, such as harmonizer, supporter, and tension reducer; and (3) individual roles, such as blocker, pleader, and monopolizer. Bales (1958a) noted that the first two roles are the major functions of leadership in small experimental groups. For Hemphill (1949a), the leader’s behavior could be typed according to how much he or she set group goals with the members, helped them to reach the goals, coordinated their efforts, helped them fit into the group, expressed interest in the group, and showed humanness.

From another point of view, Roby (1961) developed a mathematical model of the functions of leadership that was based on response units and information load and developed the following classification of leadership functions: (1) to bring about congruence of goals among the members; (2) to balance the group’s resources and capabilities with environmental demands; (3) to provide group structure that would focus information effectively on solving the problem; and (4) to make certain that all needed information is available at a decision center when required.

According to Schutz (1961b), the functions of leadership could be classified as follows: (1) to establish and recognize a hierarchy of group goals and values; (2) to recognize and integrate the various cognitive styles that exist in the group; (3) to maximize the utilization of group members’ abilities; and (4) to help members resolve problems that involve adapting to external realities as well as the fulfillment of interpersonal needs.

S. Levine (1949) identified four types of leaders: (1) the charismatic leader, who helps the group rally around a common aim but tends to be dogmatically rigid; (2) the organizational leader, who emphasizes effective action and tends to drive people; (3) the intellectual leader, who usually lacks skill in attracting people; and (4) the informal leader, who tends to adapt his or her style of performance to the group’s needs.

Clarke (1951) proposed three types of leaders applicable to small groups: (1) popular leaders, who wield influence because of their unique combination of personality traits or ability; (2) group leaders, who, through their understanding of personality, enable group members to achieve satisfying experiences; and (3) indigenous leaders, who arise in a specific situation when group members seek support and guidance.

Getzels and Guba (1957) offered three types of leadership, two of which are associated with separate dimensions of group activity: (1) nomothetic leadership, which is involved with the roles and expectations that define the normative dimensions of activity in groups; (2) ideo-graphic leadership, which is associated with the individual needs and dispositions of members that define the personal dimensions of group activity; and (3) synthetic leadership, which reconciles the conflicting demands that arise from the two contrasting subgroups within a group. Bowers and Seashore (1967) maintained that the functions of leadership are support of members, facilitation of interaction and of work, and emphasis on goals. Cattell (1957) observed that the leader performs the following functions: maintaining the group, upholding roles and status satisfaction, maintaining task satisfaction, keeping ethical (norm) satisfaction, selecting and clarifying goals, and finding and clarifying means of attaining goals.

Using a factor analysis of behavioral ratings, Oliverson (1976) identified four types of leaders in 24 encounter groups: (1) technical, (2) charismatic, (3) caring-interpersonal, and (4) peer-oriented. The technical leader emphasizes a cognitive approach; the charismatic leader stresses his or her own impressive attributes; and types 3 and 4 accentuate the facilitation of interpersonal relations with caring and friendship.

After observing 16 group-therapy leaders of various theoretical persuasions, Lieberman, Yalom, and Miles (1973) formulated three types of group leaders: (1) charismatic energizers, who emphasize stimulation; (2) providers, who exhibit high levels of cognitive behavior and caring; and (3) social engineers, who stress management of the group as a social system for finding intellectual meaning. Three other styles—impersonal, manager, and laissez-faire—were variants of the initial three. Therapeutic change in participants was highest with providers and lowest with managers. Casualties were highest with energizers and impersonals and lowest with providers. Again from observations of therapy groups, Redl (1948) suggested that the leader may play the role of patriarch, tyrant, ideal, scapegoat, organizer, seducer, hero, and bad or good influence.

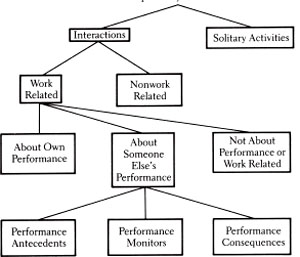

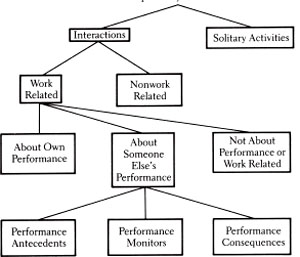

Komaki, Zlotnick, and Jensen (1986) provided a sophisticated and rigorous approach to classifying the behavior of leaders on the basis of a minute-by-minute time sampling of coded observations in a small-group setting. Their taxonomy, which was constructed to provide observers a way to categorize specific supervisory behaviors, includes seven categories. The first three categories are derived from operant-conditioning theory; they are related to effective supervision: (1) consequences of supervisees’ performance, indicating knowledge of performance; (2) monitors of performance, involving collecting information; (3) performance antecedents, providing instructions for performance; (4) “own performance,” referring to the supervisor’s performance; (5) “work-related,” referring to work but not performance; (6) “non-work-related,” not pertaining to work; and (7) solitary, not interacting with others. The categories are linked, as shown in Figure 2.1.

Analyses of the behavior of leaders have also produced many other categorizations of such behavior in small groups (e.g., Reaser, Vaughan, & Kriner, 1974). Much of the leadership in small groups has relevance for groups within larger organizations and institutions.

Presentations of types of leaders in organizations and institutions coincided with the appearance of essays on effective management. J. H. Burns (1934) proposed the following types: the intellectual, the business type, the adroit diplomat, the leader of small groups, the mass leader, and the administrator.

Bogardus (1918) distinguished four types of organizational and institutional leaders: (1) the autocratic type, who rises to office in a powerful organization; (2) the democratic type, who represents the interests of a group; (3) the executive type, who is granted leadership because he or she is able to get things done; and (4) the reflective-intellectual type, who may find it difficult to recruit a large following.

Figure 2.1 Operant Taxonomy of Supervisory Behavior

SOURCE: J. L. Komaki, S. Zlotnick, and M. Jensen, “Development of an Operant Based Taxonomy and Observational Index of Supervisory Behavior,” Journal of Applied Psychology, 1986. Copyright 1986 by the American Psychological Association. Reprinted by permission of the publisher and author.

Sanderson and Nafe (1929) proposed four types of leaders: (1) the static leader is a professional or scientific person of distinction whose work influences the thoughts of others; (2) the executive leader exercises control through the authority and power of position; (3) the professional leader stimulates followers to develop and use their own abilities; (4) the group leader represents the interests of group members.

Chapin (1924a) differentiated political-military from socialized leaders. Political-military leaders imbue the masses with their personality; socialized leaders influence their followers to identify themselves with the common program or movement.

In Bartlett’s (1926) threefold classification: (1) institutional leaders are established by virtue of the prestige of their position; (2) dominative types gain and maintain their position through the use of power and influence; and (3) persuasive types exercise influence through their ability to sway the sentiments of followers and to induce them to action.

In seminal German publications in 1921 and 1922, Weber (1947) delineated three types of legitimate authority in organizations and institutions, each associated with a specific type of leadership: (1) bureaucratic leaders operate with a staff of deputized officials and are supported by legal authority based on rational grounds. Their authority rests on belief in the legality of normative rules and in the right of those who are elevated to authority under such rules to issue commands; (2) patrimonial leaders operate with a staff of family relatives rather than officials. They are supported by traditional authority that rests on the sanctity of immemorial traditions and the legitimacy of status of those who exercise authority under them; (3) charismatic leaders operate with a staff of disciples, enthusiasts, and perhaps bodyguards. Such leaders tend to sponsor causes and revolutions and are supported by charismatic authority that rests on devotion to the sanctity, heroism, or inspirational character of the leaders and on the normative patterns revealed or ordained by them. House and Adidas (1995) equated charismatic with transformational leaders; but Bass (1985a) suggested that charismatic and inspirational leaders formed a single factor differentiated from the transformational factors of intellectual stimulation and individualized consideration. Jennings (1960) typed these charismatic and patrimonial leaders differently. The great men who break rules and value creativity are supermen; those who are dedicated to great and noble causes are heroes; and those who are motivated principally to dominate others are princes. Princes may maximize the use of their raw power, or they may be great manipulators. Heroes come in many varieties, including heroes of labor, consumption, and production; risk-taking heroes; and war heroes. Supermen may or may not seek power to dominate others.

Several commentators have noted that types of leadership are classifiable according to the model of organization in which the leadership occurs. Golembiewski (1967) proposed that the collegial model of organization permits leadership to pass from individual to individual at the same level in the organization. The traditional model implies that leadership is retained within the positions established by a hierarchy of authoritative relationships.

Influenced by Burns and Stalker (1961), Sedring (1969) suggested that political leaders in the adaptive, organismic model of organization are characterized by inter dependence, evolutionary change, and domination by factors that involve the whole organization of which their unit is a part.1 In the rule-based mechanistic model of organization, leaders are classified by a lack of integration, by conflict in relationships, and by dominance by factors in their own units. Morrow and Stern (1988) typed managers according to their performance in assessment programs.2 The stars were smart, sensitive, social, self-assured, sustained self-starters. The next best in assessments were the adversaries, who were able, analytic, argumentative, adamant, abrupt, and abrasive. The least adequate, according to their assessment, were the persevering, pain staking producers and the phantoms (polite, passive, and perturbed).

On the basis of John Dewey’s philosophy and a search of the literature, Lippitt (1999) proposed six types of leaders of organizations, according to their priorities: (1) inventor (developing new ideas, products, and services); (2) catalyst (gaining market share and customers); (3) developer (creating systems for high performance); (4) performer (improving processes for effective use of resources; (5) protector (building a committed workforce and supporting values, identity, and culture); (6) challenger (identifying strategic options and positioning the organization for the future).

Maccoby (1979) posited three ideal types of leaders of business and industry in a longer view of production in the United States in the past 200 years: (1) craftsman, (2) jungle fighter, and (3) gamesman. These types matched the ideals of the prevailing social character of the time, which was linked to the mode of production then dominant and the leaders’ functions in production and service. The independent craftsman was the prototypical social character in Jefferson’s idealized democracy of farmers, craftsmen, and small businessmen. Leaders were independent lawyers, physicians, small businessmen, and farmers. They espoused egalitarian, autonomous, disciplined, and self-reliant virtues. After the Civil War, the paternalistic empire builder came to the fore, reflecting the rags-to-riches entrepreneurial spirit of Horatio Alger’s stories. In this post-1865 social and economic environment, “ambitious boys had to find new fathers who had mastered the new challenges. The paternalistic leader … appealed to the immigrant … in need of a patron. … The still independent craftsmen … were forced into increasingly routinized factory jobs [and] struggled [by unionizing] against the paternalistic jungle fighter” (Maccoby, 1979, p. 308). The second ideal leader, the empire builder, the lionlike jungle fighter with patriarchal power, gave way to the third ideal, the gamesman. The gamesman emerged in the twentieth century when social character became more self-affirmative and the spirit more meritocratic. Adventurous and ambitious but fair and flexible leadership became the dominant ideal. “With a boyish, informal style, … [the gamesman] controls subordinates by persuasion, enthusiasm, and seduction rather than heavy and humiliating commands. Fair but detached, the gamesman has welcomed the era of rights and equal opportunity as both a fair and an efficient climate for moving the ‘best’ to the ‘top’ ” (Maccoby, 1979, p. 309). The gamesman enjoys challenges and is daring, willing to innovate and to take risks (Maccoby, 1976). But the games-man can become a liability to a firm when one person’s gain can be another person’s loss. Leadership is needed that values caring and the assurance that no one will be penalized for cooperation. Both sacrifice and reward need to be shared equitably (Maccoby, 1981).

In U.S. industry, task-oriented leaders dominated production in the 1940s, when everything that was produced could be easily sold. In the 1950s, these leaders gave way to relations-oriented leaders, who had to find markets for what was produced in an “other-oriented” nation of conformists. For a nation that next turned inward, self-oriented leaders emerged in the late 1960s and 1970s during the “me too” generation of drugs and flower children. Between 1980 and 2005, increased task-orientation was reflected in the start-ups in electronics and biotech firms coupled with increased relations-orientation to family and increased scandalous self-oriented, self-serving behavior in business and government, and then a turning inward toward spirituality and religiosity.

Executive Characteristics. Zaccaro (1996) used job analyses and psychological assessments to categorize required characteristics and skills for the executive position: cognitive capacities and skills (intelligence, analytical reasoning, ability to integrate complexities flexibly, verbal skills, writing skills, and creativity); social capacities and skills (social reasoning, behavioral flexibilty, and skills in negotiation, persuasion, and conflict management); personality traits (openness, curiosity, self-discipline, flexibility, willingness to take risks, and inner locus of control); motivation (self-efficacy, need for achievement, need for socialized power); expertise and knowledge, and metacognitive skills (the ability to construct problems, encode information, specify categories, combine and reorganize best-fitting categories, evaluate ideas, implement, and monitor) were required. Also required was the need to know when to apply these skills (Mumford, Zaccaro, Harding, et al., 1993).

Leaders of Crowds. Leaders of mobs and crowds were the first to be given social psychological classification. LeBon (1897) described the crowd leader as a persuasive person of action whose intense faith and earnestness resist all reasoning and impel the mob to follow. Influenced by LeBon (1897), Conway (1915) observed three types of crowd leaders: (1) the “crowd-compeller” inflames followers with his or her point of view; (2) the “crowd-exponent” senses what the crowd desires and gives expression to it; and (3) the “crowd-representative” merely voices the already formed opinions of the crowd.

Since these early views about leadership of a crowd, spontaneous crowds have frequently been replaced by organized demonstrations complete with television reporters. In such demonstrations, the leader must add considerable administrative effort to this overall performance; usually, the leader here is Conway’s third type—the crowd-representative—speaking to the already converted. Advanced planning as to time and place are important for the mobilization to be effective.

Student Leaders. As a result of observations and interviews, Spaulding (1934) classified elected student leaders into the following five types: (1) the social climber, (2) the intellectual success, (3) the good fellow, (4) the big athlete, and (5) the leader in student activities. From then on, the typing of student leaders as social, political, athletic, or intellectual became a common practice.

Educational Leaders. Typologies of educational leaders have included teachers, principals, and staff members in elementary, middle, and high schools. Likewise, studies have been completed of students, faculty members, department chairs, deans, presidents, and administrative leaders in colleges, universities, and technical schools. Harding (1949) distinguished 21 types of adult educational leaders: (1) autocrat, (2) cooperator, (3) elder statesman, (4) eager beaver, (5) pontifical type, (6) muddled person, (7) loyal staff person, (8) prophet, (9) scientist, (10) mystic, (11) dogmatist, (12) open-minded person, (13) philosopher, (14) business expert, (15) benevolent despot, (16) child protector, (17) laissez-faire type, (18) community-minded person, (19) cynic, (20) optimist, and (21) democrat.

Benezet, Katz, and Magnusson (1981) classified college presidents as founding presidents, explorers, take-charge presidents, standard-bearers, organization presidents, and moderators. A founding president fulfills many assignments until a regular staff has been assembled. The explorer brings on new programs and risky new plans; the take-charge president holds together an institution that is facing great difficulties; the standard-bearer leads an institution that has “arrived”; the organization president is a pragmatic administrator; and the moderator is an egalitarian administrator who consults with and delegates a great deal to faculty members and student leaders.3

Birnbaum (1988) typed college presidents as bureaucratic, collegial, political, or symbolic. They differed in their orientation toward their college’s faculty, administrators, students, alumni, and finances. Looking to the future, Weber (1995) saw a need to replace the traditional bosses of command-structured organizations with leaders who were mentors, guides and cheerleaders.

Public Leaders: Statesmen, Politicians, and Influential People. Credit is due to Plato for the first taxonomy of political leaders. Plato classified such leaders as timocratic, ruling by pride and honor; plutocratic, ruling by wealth; democratic, ruling by popular consent on the basis of equality; and tyrannical, ruling by coercion (Shorey, 1933). This classification fits well with much of what will be analyzed in later chapters about the bases of influence and power. Plutocratic, democratic, and tyrannical leaders remain in the popular lexicon of political leadership.

Beckhard (1995) put public leaders into six commonly used categories: (1) political leaders, (2) leaders of social change, (3) leaders in social science, (4) leaders in applied social thought, (5) leaders of business organizations, and (6) leaders of nongovernmental agencies. What they all have in common is ego strength, strong convictions, and political astuteness. They need to use their power for efficiency and for the largest good.

Wills (1994) covered a much broader array of 16 representative archtypes of leaders, as well as their antitypes. The taxonomy mixed leadership roles, personality traits, cognition, styles, and behaviors. Many of the types overlapped considerably. These are common defects in many taxonomies, particularly those in popular books for the layperson. To illustrate, Wills’s taxonomy comprised the democratically elected leader as the archtype versus the also-ran as the antitype, the radical leader versus the reactionary, the reform versus the conservative leader, the diplomatic versus the undiplomatic leader, the successful versus the unsuccessful military leader, the charismatic versus the bureaucratic leader, the effective versus the ineffective business leader, the revisionist of tradition versus the traditional leader, the constitutional versus the unconstitutional leader, the intellectual leader with consideration for others versus the intellectual without consideration, the church organizer versus the nonorganizer, the sports organizer with and without consideration for others, the artistic leader versus the exploiter, the rhetorical leader versus the nonuser of speeches, the opportunistic versus the inflexible leader, and the saintly versus the self-centered leader.

With respect to public leadership, Bell, Hill, and Wright (1961) identified formal leaders (who hold official positions, either appointed or elected), reputational leaders (who are believed to be influential in community or national affairs), social leaders (who are active participants in voluntary organizations), and influential leaders (who influence others in their daily contacts).

Haiman (1951) suggested that five types of leaders are needed in a democracy: (1) the executive, (2) the judge, (3) the advocate, (4) the expert, and (5) the discussion leader.

Hermann (1980) categorized political leaders, such as members of the politburo in the Soviet Union, according to whether they were generally sensitive to the political context and whether they wanted to control what happened or be an agent for the viewpoints of others.

Kaarbo and Hermann (1998) presented a taxonomy concerning political leaders’ style of involvement in foreign policies according to their degree of interest and experience (high, moderate, low) and focus (developing policy or building support). Managing information was classified into those who interpret or filter sources of information (or do both). Additionally, managing conflict was categorized with the leader as advocate, consensus-builder, or arbitrator and as locus of decision (exclusive or inclusive, and balancer or bridge).

Prophets. For Kincheloe (1928), prophets were leaders without offices. Although prophets may arise in times of crisis, they create their own situation. Their real ability is to arouse their followers’ interest so that the followers will accept prophetic goals and support these goals enthusiastically. Prophets become a symbol of the movement they have initiated, and their authoritative words tend to release inhibited impulses within their supporters. Kiernan (1975) clustered leadership patterns in African independent churches into two types: (1) preachers and prophets; and (2) chiefs, prophets, and messiahs.

Local Government Leaders. Parry (1999) coded respondents in interviews to study processes of social influence in local government authorities during times of turbulent change. Leadership strategies were seen as deliberate plans or emergent perspectives. Other categories of response included resolving uncertainty, clarifying roles, and enhancing adaptability.

Kotter and Lawrence (1974) subdivided city mayors into categories on the basis of the agendas set by the mayors, the networks they built, and the tasks they accomplished. Ceremonial mayors set short-run agendas of small scope; they were individualistic and had a personal appeal but no staffs. Personality-individualistic mayors also had no staff, but the scope of their agendas was greater and the time involved in them was longer. Caretakers set short-run agendas of large scope, had loyal staffs, and were moderately bureaucratic. Executive mayors set agendas of large scope and of longer range, had staffs, were bureaucratic, and had a mixed appeal. Program entrepreneurs set the agendas of the largest scope, had staff resources, and built extensive networks with mixed appeals.

World-Class Political Leaders. As an example of an empirical approach, Bass and Farrow (1977a) identified six types of world-class political leaders according to their leadership styles as revealed in an inverse factor analysis. Pairs of judges independently completed a 135-item questionnaire to describe the leaders on 31 scales after they had read considerable amounts of biographical literature written mainly by the immediate subordinates of the leaders. The 15 leaders were intercorrelated according to their scores on the 31 scales through use of the Bass and Valenzi systems model (Bass, 1976). An inverse factor analysis generated six clusters in relation to the behavior of leaders and subordinates, with the highest loadings for clustered figures as follows:

Autocratic-submissive: Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin, Nicholas II, Louis XIV.

Trustworthy subordinates: Hirohito, Alexander the Great, Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Clear, orderly, relationships: Winston Churchill. Structured, sensitivity to outside pressures: Fiorello La Guardia, John F. Kennedy, Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Satisfying differential power: Lenin.

Egalitarian, analytic: Thomas Jefferson.

Revolutionary versus Loyalist Leaders. Rejai and Phillips (1988) discriminated between 50 well-known revolutionary leaders such as Fidel Castro, Thomas Jefferson, and Ho Chi Minh; and 50 who remained loyal to the existing government such as Fulgencio Batista, Thomas Hutchinson, and Nguyen Van Thieu. Revolutionaries were statistically more likely to abandon their religion and become atheists; they had fathers who had not been officials in government, the military, banking, or industry, or members of the landed gentry. They had an optimistic view of human nature but fluctuated in their attitudes toward their own country. By contrast, loyalists remained steadfast in their religious beliefs and had fathers who were more likely to be government officials or in the military, banking, and industry. They themselves were more likely to be in government service, and pessimistic about human nature but optimistic about their own country.

Legislative Leaders. J. M. Burns (1978) classified legislative leaders as ideologues, tribunes, careerists, parliamentarians, or brokers. Ideologues speak for doctrines (economic, religious, or political) that may be supported widely throughout their constituency but more typically are held by a small though highly articulate minority. Tribunes are discoverers or connoisseurs of popular needs; defenders of popular interests; or advocates for popular demands, aspirations, and governmental actions. Careerists see their legislative careers as a stepping-stone to higher office, provided they do a job that impresses their constituents and other observers. Parliamentarians, as political technicians, either expedite or obstruct legislation. They bolster the legislature as an institution of tradition, courtesy, mutual forbearance, and protection of fellow members. Brokers mediate among antagonistic legislators, balancing interests to create legislative unity and action.

Military Leaders. The military hierarchy is classified from general officer to private soldier. An example of a statistically sophisticated taxonomy of army leaders was created by Mumford, Zaccaro, Johnson et al. (2000). Their taxonomy of seven types of U.S. Army officers was based on matching profiles of abilities, personalities, and motivational characteristics with the requirements of their positions. A d2 indexed the similarity of each profile to each officer’s positional requirements. The officers were then clustered according to how well their profiles matched or failed to match the requirements for junior officer, either lieutenant or captain. Seven types of the 786 junior officers emerged; these types could also be applied to classifying 275 senior officers (captains to colonels) in the same way. The percentage of junior and senior officers of each type is shown below.

|

Junior Officers |

Senior Officers |

Concrete Achievers |

20% |

11% |

Motivated Communicators |

17 |

40 |

Limited Defensive |

15 |

12 |

Disengaged Introverts |

10 |

16 |

Social Adapters |

12 |

30 |

Struggling Misfits |

13 |

3 |

Thoughtful Innovators |

11 |

26 |

Stereotypes of Woman Leaders. Influential women have been classified in a number of ways, some fitting stereotypes about women in the workplace.4 Women in a community have been classified as fashion leaders and trendsetters, in contrast to those who are content to accept, ignore, or resist change. For example, in determining opinion leadership among women in a community, Saunders, Davis, and Monsees (1974) found it useful to classify 587 women who attended a family planning clinic in Lima, Peru, as early or late adopters and as pre- or postaccepters of family planning.

Hammer (1978) described four stereotypes of women leaders in the workplace. The earth mother brings home-baked cookies to meetings and keeps the communal bottle of aspirin in her desk. The manipulator relies on feminine wiles to get her way. The workaholic cannot delegate responsibility. The egalitarian leader denies the power of her leadership and claims to relate to subordinates as a colleague. Similarly, Kanter (1976, 1977a, 1977b) discerned four stereotypes of women leaders who work primarily in a man’s world: The mother provides solace, comfort, and aspirin. The pet is the little sister or mascot of the group. The sex object fails to establish herself as a professional. The iron maiden tries too hard to establish herself as a professional and is seen as more tyrannical than she actually is.

Nafe (1930) pioneered the classification of leaders according to social or psychological dynamics of leaders and subordinates. Nafe presented a perceptive analysis of the dynamic-infusive leader who directs and redirects followers’ attention to the perceptual and ideational aspects of an issue until thought has been transferred into emotion and emotion into action. According to Nafe “the attitude of the leader toward the led and toward the project is found to be a problem in name only. The leader needs only to have the appearance of possessing the attitude desired by the followers.” The real problem is the attitude of the led toward the leader. The attributes of leadership exist only in the minds of the led: “The leader may be this to one and that to another, but it is only by virtue of having a following that he or she is a leader.” The adhesive leader (who seems to share the followers’ attitudes) is opposite in every respect to the infusive (inspiring and influential) type, according to Nafe, who added the following additional categories to his taxonomy: static versus dynamic, impressors versus expressors, volunteer versus drafted, general versus specialized, temporary versus permanent, conscious versus unconscious, professional versus amateur, and personal versus impersonal.

Using analogies with genetics, Krout (1942) identified the social variant leader, who arises out of the group’s need to agree about its goals and what to do about its lagging forms of behavior. Krout also described hybrid leaders, who seek to change the social structure through discontinuous methods to achieve the group’s goals; and mutants—innovators who redefine the cultural patterns of their group and may set new goals to achieve their objectives for the group.

Jones (1983) described the ranges of leadership in terms of the kinds of control leaders exert that affect a follower’s reactions. The leader can control (1) the process or the output, and can be (2) obtrusive or unobtrusive, (3) situational or personal, and (4) paternalistic or professional. This taxonomy can be used to explain how groups can be both satisfied with their situation and yet unproductive.

Psychoanalytic Taxonomies. From a psychoanalytic perspective, Redl (1942) suggested that instinctual and emotional group processes take place around a member whose role may be patriarch, leader, tyrant, love object, object of aggression, organizer, seducer, hero, bad example, or good example. Continuing in the same vein, Zaleznik (1974) contrasted charismatic leaders with consensus leaders. Charismatic leaders are inner-directed and identify with objects, symbols, and ideals that are connected with introjection. They are father figures. Consensus leaders “appear” to be brothers or peers, rather than father figures.

Kets de Vries and Miller (1984b, 1986) presented a sixfold psychopathological classification of executives to account for their dysfunctional performance: (1) persecutory, (2) preoccupied, (3) helpless, (4) narcissisistic, (5) compulsive, and (6) schizoid-detached.5

Narcissists, “resentfuls,” and “highly likable low achievers” were the three types of flawed managers described by Hogan, Raskin, and Fazzini (undated). The transference pattern of leaders’ and followers’ emotional relations were seen by Pauchant (1991) as depending on the self-development of the leader and follower.

Strengths and Signature Themes. These self-ratings fall into three domains of leadership: (1) relating, (2) striving, and (3) thinking. The eight themes of relating include the most effective ways to work with others individually and in groups: (1) arranging; (2) developing; (3) empathizing; (4) individualizing perception; (5) caring for people and building rapport with them; (6) accepting responsibility and ownership of projects with accountability, dependability, and ethics; (7) radiating enthusiasm and creating fun; and (8) enjoying working together with associates as a team. Types of striving are achieving, activating, competing by measuring oneself against others, increasing determination in the face of resistance and obstacles, maintaining discipline and establishing structure in one’s own life and environment, and being focused and goal-oriented. The domain of thinking encompasses concepts, strategic thinking, constant measurement to improve perfomance, and a perception of how systems can improve performance (Clifton, 2000). At Gallup management seminars, participants are encouraged to focus on further improving their strengths and not to be as concerned about their weaknesses (Clifton & Nelson, 1992).

Character Types. According to Pitcher (1997), there is a continuing crisis in management and organizational leadership; this is due to managers’ and leaders’ technocratic mentality and character, in contrast to those managers and leaders who are artists or craftsmen. Technocrats lack emotion, imagination, good judgment, and vision. They are analytical, intense, methodological, and detail-oriented. They are put into power to try to ensure rationality in decision making. They drive out of the organization those whom they perceive as emotional. Artists are people-oriented, entrepreneurial, bold, intuitive, and imaginative. They are visionary leaders who talk in metaphors rather than specifics. Craftsmen are dedicated, reliable, realistic, and knowledgeable. They appreciate the past and near future in their thinking, They have a realistic strategic vision. They have “people skills” and generate loyalty from subordinates. Technocrats downgrade artists and craftsmen, whereas artists and craftsmen admire and cooperate with each other.

Lewis, Kuhnert, and Maginnis (1987) sorted military officers into three character types. Operators have a personal agenda that they pursue without concern for others; they lack empathy and cannot be trusted. Team players are highly sensitive to how others feel about them and value decisions according to what others will think or say, rather than according to the merits of the case. In contrast, self-defining leaders are personally committed to ideals and values and pursue what they regard as the right and most worthy solutions.

Myers-Briggs Types. Jung’s (1971) psychoanalytic conceptualization was the basis of the popular Myers-Briggs fourfold classification of the thought processes of leaders and managers faced with decisions and problems. The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (Myers & McCaulley, 1985) sorts leaders into four types and 16 subtypes based on their responses to the indicator. Leaders are: (1) extroverted or introverted, (2) sensing or intuitive, (3) thinking or feeling, and (4) judging or perceiving. The extrovert prefers the outer world of people, things, and activities, whereas the introvert prefers the inner world of ideas and concepts. The extrovert is gregarious and people-oriented; the introvert seeks accomplishment working with just a few key colleagues. The sensing type of leader is oriented toward facts, details, and reality; the intuitive leader is focused more on inferences, concepts, and possibilities. The thinking types prefer analysis, logical order, and rationality and are seen as “cold” by feeling types. The feeling types, who value feelings and harmony, are described as too “soft” by the thinking types. The judging types prefer to make decisions rapidly and move on to the next issue, but the perceiving types seek to delay decisions.

A sample of 875 U.S. managers who were tested by the Center for Creative Leadership (Osborn & Osborn, 1986) between 1979 and 1983 were distributed as follows: extroverts (50%), introverts (50%), sensors (52%), intuitives (48%), thinkers (82%), feelers (18%), judges (70%), and perceivers (30%).

The four Myers-Briggs types, as noted above, generate 16 subtypes of managers. The 875 managers were concentrated in four of the subtypes: ISTJ (introverted-sensing-thinking judges), ESTJ (extroverted-sensing-thinking judges), ENTJ (extroverted-intuitive-thinking judges), and INTJ (introverted-intuitive-thinking judges). Delunas (1983) showed that for 76 federal executives and managers from private industry, the Myers-Briggs types (sensors-perceivers, sensors-judges, intuitives-thinkers, and intuitives-feelers) were significantly linked with their most or least preferred administrative styles.

Data from almost 7,500 managers and administrators showed that the majority were types like judges who reached closure, rather than perceivers who missed nothing. They were more likely to be impersonal, logical, and analytical thinkers than to be more concerned with personal feeling and human priorities. The subtypes that were most likely to be concerned with enhancing human performance, the intuitive-feelers, were underrepresented except in human resources departments. Those who were involved in the production of tangible products or in following established procedures tended to be practical sensing types. Those who provided long-range vision tended to be imaginative, theoretical, intuitive types (McCaulley, 1989).

Other Examples of Personality Types. Other taxonomies of leadership based on personality have developed around scores that subjects obtain on various assessments of their personalities. For instance, using scales developed for the California Personality Inventory (CPI), Gough (1988) described four types of individuals who are found in diverse samples of students and adults: (1) leaders, (2) innovators, (3) saints, and (4) artists. Leaders and innovators are extroverts, but leaders are also ambitious, enterprising, and resolute, while innovators are adventurous, progressive, and versatile. Saints and artists are introverted, but the saints are steadfast, trustworthy, and unselfish whereas the artists are complex, imaginative, and sensitive. Leaders and saints accept norms; innovators and artists question norms. Although only 25% to 30% of the general population of students and adults were classified by the CPI as leaders, 66% of cadets at West Point were so typed. Leaders and innovators at West Point had a higher aptitude for military service than the saints or artists.

Many attempts have been made to categorize organizational leaders and managers specifically according to the kinds of functions they perform, the roles they play, of the behaviors they display, and their cognitions and perceptions. Numerous classification schemes have appeared. Many of them prescribe functions for the ideal organizational leader. Others are derived from empirical job analyses or factored behavioral descriptions of the actual work performed by managers and administrators. For example, both approaches have concluded that the organizational leader may play the role of final arbitrator, the superordi-nate whose judgment settles disputes among followers. This function was often considered critical for the avoidance of anarchy in political units and societies. The maintenance and security of the state, it was believed, depended on the existence of a legitimate position at the top, to which all followers would acquiesce to avoid the continuation of conflict among them.

Classical theories of ideal management indicated that the primary functions of managers and executives could be neatly characterized as planning, organizing, and controlling. Although coordinating, supervising, motivating, and the like were added to the list, they were seen merely as variations managers’ and executives’ function of organizational control. On the other hand, behavioral descriptions of the functions of actual managers and executives included defining objectives, maintaining goal direction, providing means for attaining goals, providing and maintaining the group structure, facilitating action and interaction in the group, maintaining the cohesiveness of the group and the satisfaction of members, and facilitating the group’s performance of tasks.

The functions identified by the behavioral descriptions grew out of research on basic group processes and on the emergence of the leadership role and its contribution to the performance, interaction, and satisfaction of members who are engaged in a group task. The classical functions of planning, organizing, and controlling were concerned with the rationalized processes of formal organizations. Although these functions are generalized and abstract, they are by no means unreal; however, they tend to ignore the human nature of members of the organization and the limited rationality with which the manager must operate. Yet organizations strive for rationality. Understanding the purposes of a leader in an organization requires a consideration of his or her planning, directing, and controlling. However, many more behaviors emerge in large-scale descriptive surveys and interviews with leaders.

Mooney and Reiley (1931) identified the three functional processes in any organization as being the same as in any governmental entity: legislative, executive, and judicial. Coffin (1944) suggested that the three functions of organizational leadership were formulation (planning), execution (organizing), and supervision (persuading). Barnard (1946b) identified the functions of organizational leadership as (1) determination of objectives, (2) manipulation of means, (3) instrumentation of action, and (4) stimulation of coordinated effort. Davis (1951) was in agreement with many others in declaring that the functions of the business leader are to plan, organize, and control an organization’s activities. In a study of leadership in Samoa, Kessing and Kessing (1956) identified the following leadership functions: consultation, deliberation, negotiation, the formation of public opinion, and decision making. Gross (1961) proposed these functions: to define goals, clarify, and administer them; to choose appropriate means; assign and coordinate tasks; to motivate; create loyalty; represent the group; and spark the membership to action.

Selznick (1957) suggested that the functions of organizational leadership include: (1) definition of the institution’s mission and goals; (2) creation of a structure to achieve the institution’s purpose; (3) defense of institutional integrity; and (4) reevaluation of internal conflict.

Katz and Kahn (1966) advocated three functions for organizational leadership: (1) policy formation (the introduction of structural change); (2) the interpretation of structure (piecing out the incompleteness of the existing formal structure); and (3) administration (the use of a formal structure to keep the organization in motion and operating effectively).

Wofford (1967) proposed the following functions of management be selected: setting objectives, organizing, leading, and controlling. For Krech and Crutchfield (1948), a leader could be an executive, planner, policy maker, expert, representative of the external group, controller of internal relationships, purveyor of rewards and punishments, arbitrator and mediator, exemplar, symbol of the group, surrogate for individual responsibility, ideologist, father figure, and scapegoat.

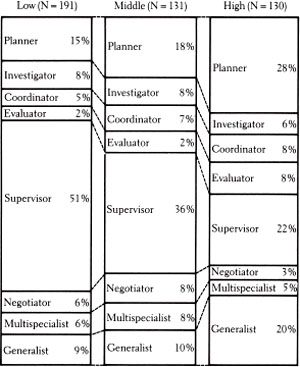

T. A. Mahoney (1955, 1961) and colleagues (Ma-honey, Jerdee, & Carroll, 1965) typed managers according to their main functions. According to a survey of 452 managers in 13 firms, supervising was the main function of 51% of lower-level supervisors, 36% of middle managers, and 22% of top managers. Top managers were more likely than lower-level managers to be generalists and planners. Figure 2.2 shows how managers could be typed according to their main function. As can be seen, the type of manager depended on the organizational level.

Williams (1956) focused on dealing with knowledge, decision making, interaction with others, character, organization over person, policies, and records. Koontz, O’Donnell, and Weihrich (1958) wrote about planning, organizing, motivating, and controlling. McGrath’s (1964) fourfold classification concerned monitoring, forecasting, taking direct action, and creating conditions. For Bennett (1971), the taxonomy included deciding, planning, analyzing, interacting with people, and using equipment. For Hemphill (1950a), who used factor analytical approaches of leaders, the functions of supervisors, managers, and executives were initiation, representation, fraternization organization, domination, recognition, production, integration, and communication down6 and communication up (in the organization).7 For Hemphill (1960), supervisors, managers, and executives dealt with the following: providing staff services; supervising work; controlling business, technical markets, and production; human, conducting community, and social affairs; engaging in long-range planning; exercising broad power and authority; maintaining one’s business reputation; meeting personal demands; and preserving assets. For Fine (1977), who employed job analyses, the functions were analyzing, negotiating, consulting, instructing, and exchanging information. For Dowell and Wexley (1978), they included working with subordinates, organizing their work, planning and scheduling work, maintaining efficient and good-quality production, maintaining equipment, and compiling records and reports.

Figure 2.2. Distribution of Assignments Among Job Types at Each Organizational Level

(NOTE: Totals do not add up to 100 percent because of rounding.)

SOURCE: Mahoney, Jerdee, and Carroll (1965).

An outstanding example of a large-scale long-term analysis of management functions was Tornow and Pinto’s (1976) taxonomy which involved long-range thinking and planning; the coordination of other organizational units and personnel; internal control; responsibility for products, services, finances, and board personnel; dealing with public and customer relations, complexity, and stress; advanced consulting; maintaining the autonomy of financial commitments; service to the staff; and supervision.8

The categorizations were fine-tuned and became more numerous. Winter (1978) generated 19 possible functional leadership competencies, ranging from conceptualizing to disciplining. They were expanded to 66 competencies by D. Campbell (1991). Metcalfe (1984) came up with 20 classes of leaders’ behavior, ranging from proposing procedures to shutting out other persons’ efforts to participate. Van Fleet and Yukl (1986a) emerged with a detailed breakdown of 23 functions, ranging from showing consideration to monitoring reward contingencies. Subsequently these were combined by Yukl (1998) into 14 functions, reworked from a previous list of 15 functions (Yukl, 1989): (1) networking; (2) supporting; (3) managing conflict and team building; (4) motivating; (5) recognizing; (6) rewarding; (7) planning and organizing; (8) problem solving; (9) consulting; (10) delegating; (11) monitoring; (12) informing; (13) clarifying; (14) developing and mentoring.

On the basis of his observations of managers at work, Mintzberg (1973) created a taxonomy in which managers were seen to engage in three sets of roles: interpersonal, informational, and decisional. Within each of these sets, specific roles were conceived. The interpersonal set included the figurehead, leader, and liaison. Within the informational set were the monitor, disseminator, and spokesman. Within the decisional set were the entrepreneur, disturbance handler, resource allocator, and negotiator.

Javidan and Dastmalchian (1993) described five leadership roles: mobilizer, ambassador, driver, auditor, and servant.

Kraut, Pedigo, et al. (1989) delineated seven leadership roles: (1) managing individual performance, (2) instructing subordinates, (3) planning and allocating resources, (4) coordinating independent groups, (5) managing group performance, (6) monitoring the business environment, and (7) representing one’s staff. Baehr (1992) proposed 16 leadership roles ranging from setting organizational objectives to handling outside contacts.

Wells (1997) proposed nine roles for organizational leaders driven by values: (1) Sages develop wisdom through gaining knowledge about the organization’s history and future prospects, and can deal with complexities, ambiguities, and contradictions; (2) Visionaries push to go beyond what has been previously accomplished and stimulate others to share in pursuit of the vision; (3) Magicians coordinate change by balancing the organization’s structures, systems, and processes; (4) Globalists build bridges across cultures and find common ground on productive work can occur; (5) Mentors motivate others to advance their careers by helping people to learn and work to their potential and to find new perspectives and meaning in their jobs; (6) Allies build partnerships by seeking mutually beneficial collaborations that can improve performance; (7) Sovereigns take responsibility for the decisions they make and empower others with significant authority; (8) Guides use clearly stated principles to direct tasks toward goals important to the whole organization, are action-oriented, and are excited by the challenge of moving things forward; (9) Artisans are devoted to the mastery of a craft and the pursuit of excellence, concerned with the aesthetic as well as the practical to provide the customer with maximum value by continuous improvements. The same leader can perform a number of different roles.

Quinn’s (1984) competing values framework is a taxonomy of management roles to indicate conditions under which enacting them would be most conducive to effectiveness. The patterns observed gave rise to seven types of managers. The same managers could play roles conceived to be opposite in value, and the roles could be placed at two ends of a continuum. The four bipolarities were: (1) mentor versus director; (2) facilitator versus producer; (3) coordinator versus innovator; and (4) monitor versus broker (Quinn, Dixit, & Faerman, 1987).

Mentors and facilitators are flexible and internally focused. Coordinators and monitors are internally focused and controlling. Directors and producers are externally focused and controlling. Innovators and brokers are flexible and externally focused. Mentors are particularly caring, empathetic, and concerned about individuals. Facilitators are interpersonally skilled and particularly concerned about group processes, cooperation, and cohesiveness. Producers are task-oriented, action-oriented, energetic, and specifically concerned about getting the work done. Coordinators are dependable, reliable, and concerned with maintaining continuity and equilibrium in the group. Innovators are clever, creative, conceptually skillful, and searching for better ways and opportunities. Monitors are well-prepared, well-informed, competent, and technically expert. Brokers are resource-oriented, politically astute, and especially concerned about influence, legitimacy, and acquiring resources. Effective leaders are typed as masters, conceptual producers, aggressive achievers, peaceful team builders, long-term intensives, and open adaptives. Masters are high in all eight opposing roles. Conceptual producers are almost like masters, except that they are lower in monitoring and coordinating. Aggressive achievers are high in monitoring, coordinating, directing, and producing but are lower in the other roles, particularly facilitating. Peaceful team builders are high in six of the roles but lower in the roles of broker and producer. Long-term intensives are high in the roles of innovator, producer, monitor, and facilitator and fall nearer the mean on the roles of mentor and director. Open adaptives are much less likely to monitor and co-ordinate. Ineffective managers were typed with the same kind of analysis of management roles into chaotic adaptives, abrasive coordinators, drowning workaholics, extreme unproductives, obsessive monitors, permissive externals, and softhearted indecisives (Hooijberg & Quinn, 1992). Hooijberg and Choi (2000) demonstrated that the effectiveness of managerial leadership was greater if the subordinate leaders saw themselves resembling their supervisors and managers in taking the effective roles of innovator, broker, monitor, mentor, producer, and facilitator.

Special Organizational Leadership Roles. According to Senge (1995), to lead learning organizations, organizations dedicated to continuous improvement and adaptation, three types of leaders are needed: (1) executive leaders, (2) local line leaders, and (3) internal networkers or community leaders.

Schein (1995) called for four kinds of leadership that were required in different stages of the development of an organization’s culture: first, the animator was needed to build the culture; second came the maintainer; third came the sustainer; and fourth came the change agent to help promote necessary revisions.

As a strategic manager for General Electric and as a consultant, Rothschild (1993) developed a taxonomy of the types of strategic leader needed at different stages of an organization’s life. As the organization starts up and grows rapidly, the strategic leader has to be a risk taker. When growth slows, a disciplined caretaker is needed to maintain stable long-term growth. If the organization must cope with significant declines, a surgeon leader is needed to act quickly. When there is no hope of turnaround, an undertaker leader is needed to dispose of the organization’s assets compassionately and decisively.

Compared with leaders’ functions, roles and behaviors, their cognitions and perceptions have received much less research. Lord (1985) advanced the study of the structures underlying the cognitive categorization of leaders, which determined how they were perceived by others. The perceiver is seen as an active selector and organizer of stimulus information to provide cognitive economy. Categorizing information allows similar but nonidentical leaders to be seen as equivalent in a perceptual structure.

Hunt, Boal, et al. (1990) provided a fourfold categorization of leadership prototypes: (1) Heroes are leaders perceived as experts in both content and process. (2) Technocrats are perceived as experts in content but not process. (3) Ringmasters are perceived as experts in process but not content. (4) Illegitimate leaders are perceived as experts in neither content nor process.

Bimbaum (1988) organized a taxonomy of how college and university presidents differed in their frames of reference: bureaucratic, collegial, political, or symbolic. According to Bensimon (1990) bureacratic presidents control by being active in making decisions, resolving conflicts, solving problems, evaluating performance and outputs, and distributing rewards and penalties. They are likely to be authoritarian, decisive, and results-oriented. The collegial president views the members of the establishment as the most important resource. Collegial presidents favor goal achievement and define priorities through teamwork, collective action, building consensus, loyalty, and commitment. Presidents with a political frame of reference see their institution as consisting of formal and informal constituencies competing for power to control the college’s processes and outcomes. Decisions are the result of bargaining and coalition building. The president serves as a mediator who must be persuasive, diplomatic, and able to deal with shifting power blocs. The president with a symbolic frame of reference focuses on his or her institution as a culture of shared meanings and beliefs. Rituals, symbols, and myths are sustained to provide a sense of the college’s purpose and order by interpretation, elaboration, and reinforcement of its culture. The 32 college and university presidents who were interviewed by Bensimon (1990) described themselves as most symbolic in their frames of reference and least political. This was quite different from descriptions by their 80 trustees, deans, directors, and department heads, who described the presidents as most bureaucratic and least symbolic in their frames of reference. For presidents with a strong bureaucratic orientation, campus leaders saw little of the other types in the president.

Leadership and management styles are alternative ways that leaders and managers pattern their interactive behavior with those they influence.

Transactional versus Transformational Leaders. As Buckley (1979) noted, the successful political leader is one who “crystallizes” what people desire, “illuminates” the rightness of that desire, and coordinates its achievement. Such leadership can be transactional or transformational. This distinction has become of considerable importance to the study of leadership since Burns’s (1978) work (Bass, 1985a; Bennis & Nanus, 1985; Tichy & Devanna, 1986; Bryman, 1992; Curphy, 1992). In exchanging promises for votes, the transactional leader works within the framework of the self-interests of his or her constituency, whereas the transformational leader moves to change the framework. Forerunners of this distinction are to be found in Hook’s (1943) differentiation of the eventful man and the event-making man. The eventful political leader is swept along by the tides of history; the event-making political leader initiates the actions that make history. President Lincoln’s predecessor, Buchanan, was content to stand by and allow the Union to disintegrate slowly; Lincoln was determined to hold the Union together and to reverse what seemed at the time to be the inexorable course of southern secession.

Downton (1973) discussed the leadership of rebels in terms of this distinction between the transactional and the transformational leader. And Paige (1977) concluded that it would be useful to classify political leaders according to the changes they sought and achieved, as conservative, reformist, or revolutionary. Conservative leaders tend to maintain the existing political institutions and policies, reformist leaders promote moderate changes in institutions and policies, and revolutionary leaders (as well as radical leaders) strive for fundamental changes in existing institutions and policies. Reactionaries want to revert to institutions of the past.

For Burns (1978, p. 3), who provided a comprehensive theory to explain the differences between transactional and transformational political leaders, transactional leaders “approach followers with an eye to exchanging one thing for another: jobs for votes, or subsidies for campaign contributions. Such transactions comprise the bulk of the relationships among leaders and followers, especially in groups, legislatures, and parties.” Burns noted that the transformational leader also recognizes the need for a potential follower, but he or she goes further, seeking to satisfy higher needs, in terms of Maslow’s (1954) need hierarchy, to engage the full person of the follower. Transforming leadership results in mutual stimulation and elevation “that converts followers into leaders and may convert leaders into moral agents.” If the follower’s higher-level needs are authentic, more leadership occurs. Burns went on to classify transactional political leaders as opinion leaders, bargainers or bureaucrats, party leaders, legislative leaders, and executive leaders. Transformational leaders were categorized as intellectual leaders, leaders of reform or revolution, and heroes or ideologues.

Until the 1980s, most experimental research focused on transactional leadership (see, for example, Hollander, 1978), whereas the movers and shakers of the world are transformational leaders. Although both types of leaders sense the felt needs of their followers, it is the transformational leader who raises consciousness (about higher considerations) through articulation and role modeling. Through transformational leaders levels of aspiration are raised, legitimated, and turned into political demands.9 The transformational/transactional classification has been used to study leaders in many sectors, including health care, the military, business, sports coaching, politics, government service, and nonprofit agencies (Bass & Riggio, 2005). Confirmatory factor analyses by Avolio, Bass, and Dong (1999) of 14 surveys that used the Multi-factor Leadership Questionnaire concluded from the best-fitting model that transformational leaders are inspirational, intellectually stimulating and/or individually considerate; transactional leaders practice contingent reward and active management by exception (contingent negative feedback). On the basis of ratings of CEOs by 253 senior executives, and of middle managers by 208 supervisors, Pearce, Sims, Cox, et al. (2002) found that a four-factor model of leadership fit the data best in comparison with other models: directive leadership (instruction and command, assigned goals, contingent reprimand); transactional leadership (contingent material reward, contingent personal reward); transformational leadership (stimulation and inspiration, vision, idealism, challenge to the status quo); and empowering leadership (encouraging thinking in terms of opportunities, encouraging self-reward and self-leadership, setting goals participatively, and encouraging teamwork).

Relations-Oriented and Task-Oriented Leaders. Blake and Mouton (1964) studied the dimensions—from one (low) to nine (high)—of task-and relations-oriented leadership by using a grid. Five styles could be generated from the dimensions. These will be detailed in Chapter 19. Reddin (1977) advanced this popular taxonomy of management in relation to eight types, each of which is a consequence of being low or high in Blake and Mouton’s two dimensions of relationships and task orientation and a third dimension—effectiveness. Managers are characterized as various combinations of this three-dimensional typology, as shown in the table here.

Managers Typed by their Leadership Styles

Type of Leadership |

Relationship Orientation |

Task Orientation |

Effectiveness |

Deserter |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Autocrat |

Low |

High |

Low |

Missionary |

High |

Low |

Low |

Compromiser |

High |

High |

Low |

Bureaucrat |

Low |

Low |

High |

Benevolent autocrat |

Low |

High |

High |

Developer |

High |

Low |

High |

Executive |

High |

High |

High |

An equally compelling typology of managerial styles was developed by Tannenbaum and Schmidt (1958), focusing on the issue of who shall decide—the leader or the follower. Their types were arranged along an authoritarian-democratic continuum: the leader who announces the decision, the leader who sells the decision, the leader who consults before deciding, the leader whose decisions are shared, and the leader who delegates decision making.10 Hersey and Blanchard (1969a) made extensive use of this typology.

Bradford and Cohen (1984) categorized styles of managers: the manager as technician, the manager as conductor, and the manager as developer. The manager as technician relates information to subordinates who are committed to the leader because of the leader’s technical competence and who depend on the leader for the answers to problems. The manager as conductor is a heroic figure “who orchestrates all the individual parts of the organization into one harmonious whole” (p. 45) with administrative systems for staffing and work flow. The manager as developer “works to develop management responsibility in subordinates and … the subordinates’ abilities to share management of the unit’s performance” (pp. 60–61).

Sorting managers in terms of their stylistic emphasis on rationality and quantitative analysis, Leavitt (1986) identified three types of mangers. Pathfinders are creative and visionary; they use instinct, wisdom, and imagination to meet their goals and know how to ask questions and search out problems. Problem solvers are analytic, quantitative, and oriented toward management controls. Implementers are political and stress consensus, teamwork, and good interpersonal relationships.

Cribbin (1981) classified effective managers into the following types: entrepreneur (“We do it my way and take risks”), corporateur (“I call the shots, but we all work together on my team”), developer (“People are our most important asset”), craftsman (“We do important work as perfectly as possible”), integrator (“We build consensus and commitment”), and gamesman (“We run together, but I must win more than you”).

Har-Even (1992), developed four models of leaders: (1) charismatic (“Believe in me”); (2) authoritative (“We will act according to the laws and rules”); (3) role model (“Follow me, I have knowledge and personal experience”); and (4) facilitator (“Let’s get together, and I will help to resolve our differences”).

Fleishman, Mumford, Zaccaro, et al. (1991) reviewed 65 taxonomies of leaders’ behavior published between 1944 and 1986. Three communalities were seen in these 65 taxonomies: (1) facilitating group social interaction and pursuing task accomplishment; (2) the occurrence of management and administrative functions; and (3) emphasis on leader-group interactions. Differences in taxonomies were due to the differences in the purposes of their creators; for instance, the purpose might be to focus on leaders’ behavior or on leaders’ effectiveness. The taxonomies also differed because of differences in methods, theoretical frameworks, and intended applications. Four dimensions emerged from the biographical review: (1) “information search and structuring” (acquiring, organizing, evaluating, feedback, and control of information); (2) “information use in problem solving” (identifying needs and requirements, planning, and coordinating and communicating information); (3) “managing personnel resources” (obtaining, developing, allocating, motivating, utilizing, and monitoring personnel resources); and (4) “managing material resources” (obtaining, allocating, maintaining, utilizing, and monitoring material resources).

Manz and Sims (1993) proposed four types of leaders, based on their different kinds of behavior: strong man, transactor, visionary hero, and super-leader. The strong man assigns goals, intimidates, and reprimands his followers. The transactor uses contingent reinforcement in interactive goal-setting to reward and reprimand followers. The visionary hero communicates his or her vision; emphasizes his or her values; and exhorts, inspires, and persuades followers. The super-leader models self-leadership and develops it in followers, creates positive thought patterns, develops self-leadership in followers through contingent rewards and reprimands, promotes self-leading teams, and facilitates a self-leadership culture. “Leaders become ‘super’—that is, possess the strength of many persons—by helping to unleash the abilities of the ‘followers’ (self-leaders) that surround them.”

Types of Strategic Leadership. Strategic leadership is behavior that depends on combining perceptions of threats, opportunities, cognitions, analyses, and risk preferences. Some strategies of leaders are emergent perspectives that evolve. Other strategies result from deliberate planning (Mintzberg & Jorgenson, 1987). These may be only implicit in the minds of the leaders (Lewis, Morkel, et al., 1993). To classify strategic leaders, Lord and Maher (1993) applied the same taxonomy of four organizational strategies posited by Miles and Snow (1978)—defenders, prospectors, analyzers, and reactors: Defenders stress efficiency and product stability; prospectors focus on product innovation and development; analyzers produce and market products developed by other organizations; reactors fall behind their industry in adopting new products. Organizations are more likely to be successful when their type of strategy matches the leaders’ requisite personality; thus, for example, defender organizations are more successful if led by executives who stress efficiency and product stability.

Gupta and Govindarajan (1984) typed organizations as pursuing a build strategy of increasing market share rather than a harvest strategy of cash flow and short-term profits. For success, the build strategy requires risk-taking executives with a tolerance for ambiguity. The harvest strategy, by contrast, needs executives with little propensity for risk and little tolerance for ambiguity.

Using facet and smallest-space analysis of data from 27 business cases, Shrivastava and Nachman (1989) empirically established four patterns of strategic leadership behavior: entrepreneurial (a confident, charismatic chief executive singularly guides strategy and controls others with direct supervision); bureaucratic (strategy is based on rules and the way the bureaucracy interprets rules, policies, and procedures); political (coalitions of organizational managers with different functions, but in reciprocal interdependence, interact as colleagues to decide on strategies); and professional (small groups, dyads, or individuals control the requisite information in an open system and provide strategic direction with new rules).

On the basis of their experience as consultants, Farkas and De Backer (1996) enumerated five strategies that could be pursued by the chief executive to manage for success: (1) Act as the organization’s top strategist, systematically envisioning the future and planning how to get there; (2) Concentrate on the organization’s human assets—its policies, programs, and principles about people; (3) Champion specific expertise to focus the organization’s human assets; (4) Create a “box” of rules, systems, procedures, and values to control behavior and outcomes within well-defined boundaries; (5) Act as a radical change agent to transform the organization from a bureaucracy into an adaptive organization that embraces what is new and different.

An important executive function is to remain alert to trends in one’s own and other relevant industries, and one’s own and other organizations, regarding the possibilities and expected utilities of insourcing and outsourcing. Parry (1999) conducted a qualitative study of local government administrators in New Zealand. From interviews with and responses of senior, middle, and operational leaders, it was possible to categorize their strategies. Social influence enhanced adaptability and resolved uncertainty. These leaders developed strategies to enhance their own and their followers’ adaptability to the uncertainties of change.

Despite the plethora of diverse types and taxonomies of leadership, five common themes appear: (1) The leader helps set and clarify the missions and goals of the individual member, the group, or the organization; (2) The leader energizes and directs others to pursue the missions and goals; (3) The leader helps provide the structure, methods, tactics, and instruments for achieving the goals; (4) The leader helps resolve conflicting views about means and ends; (5) The leader evaluates the individual, group, or organizational contribution to the effort. Many of the taxonomies include certain styles: authoritative, dominating, directive, autocratic, and persuasive. Common types are democratic, participative, group-developing, supportive, and considerate. Other types include intellectual, expert, executive, bureaucrat, administrator, representative, spokesperson, and advocate.