What roles in organizations do leaders and managers play? What organizational functions do they serve? How does the hierarchical level of the organizational leader and manager affect these activities? Are their roles changing? What makes their activities more or less effective?

From the top to the bottom echelons of the formal organization, except for the lowest level, all members report directly to a higher authority and lead followers at the levels below them. They are leaders inside organizations as well as leaders of organizations. The operating employee reports to a supervisor, the supervisor to a manager, the manager to an executive, the executive to the chief executive, and the chief executive to a board of directors, which is responsible to a constituency of shareholders or a public body.

As was noted in Chapter 2, for classical management theorists like R. C. Davis (1942), Urwick (1952), and Fayol (1916), orderly planning, organizing, and controlling were the functions of supervisors, managers, and executives in formal organizations of hierarchically arranged groups and individuals. Planning, organizing, and controlling were regarded as completely rational processes. For some, such as K. Davis (1951), the prescription for business leaders was the same as for managers—to plan, organize, and control an organization’s activities. Little attention was paid to the human nature of the members constituting the organization. Although organizations strive for rationality, observation suggests that such rationality is limited (March & Simon, 1958). Nevertheless, understanding the purpose of the manager requires consideration of the planning, organizing, and controlling functions of the manager, for whom supervision and leadership may often be the most important but not the only aspect of his or her responsibilities. Thus an empirical factored survey, completed by Wofford (1967) (one among many), could reveal factors to describe managers’ functions as setting objectives, planning, organizing, leading, and controlling. Managers in organizations do perform the functions of planning, organizing, and controlling. But limiting the analysis to such general functions inhibits a more searching type of inquiry into the nature of managerial performance—about what administrators, managers, and executives actually do. Leadership remains an important component to the degree that management means getting work done with and through others. The overlapping needs of the organization, task, team, and individual must be addressed. Thus Coffin (1944) modified the classical functions of management as follows: formulation (planning), execution (organizing), and supervision (persuading). Adair (1973) conceived the functions as planning, initiating, controlling, supporting, informing, and evaluating.

Cognitive, Behavioral, and Socioemotional Components. Organizational leadership has both interpersonal and strategic components (Lohmann, 1992). Barnard (1938) was most influential in introducing the need to include more behavioral, intuitive, social, and emotional components in the functional analyses of organizational leadership. Numerous other scholars incorporated behavioral, social, and political elements in their analyses of the functions of organizational leadership. Barnard (1946b) identified the functions of organizational leadership as: (1) the determination of objectives; (2) the manipulation of means; (3) the instrumentation of action; (4) the stimulation of coordinated effort. In this light, E. Gross (1961) elaborated on the functions of organizational leadership to define goals, clarify and administer them, choose appropriate means, assign and coordinate tasks, motivate, create loyalty, represent the group, and spark the membership to action. Similarly, Selznick (1957) suggested the following functions of organizational leadership: (1) definition of the institution’s mission and goals; (2) creation of a structure for accomplishing the purpose; (3) defense of institutional integrity; (4) reevaluation of internal conflict. In a study of leadership in Samoa, Kessing and Kessing (1956) identified as leadership functions consultation, deliberation, negotiation, formation of public opinion, and decision making. Katz and Kahn (1966) proposed three functions of leadership in terms of the organization’s actual formal structure: (1) the introduction of structural change (policy formation); (2) the interpretation of structure (piercing out the incompleteness of the existing formal structure); (3) the use of structure that is formally provided to keep the organization in effective motion, operation, and administration. Organizational leaders and leaders within organizations need to deal with both intellectual and social complexity. Intellectually, they must be able to assimilate complex information, work with cognitive complexities and conflicting points of view, and integrate diverse organizational stimuli. Social complexity arises, as leaders must deal with diverse individuals and units with conflicting demands, agendas, and goals. The complexity of roles increases with increasing organizational levels in both military and civilian hierarchies (Jacobs & Jaques, 1987). Self-monitoring, social intelligence, social perceptiveness, and behavioral flexibility become important with an increasing hierarchical level (Zaccaro, Gilbert, Janelle, et al., 1991). Zaccaro, Marks, O’Connor-Boes, et al. (1995) found that skills in solving complex problems increased with rank when 101 lieutenants, majors, and colonels were compared. Dean and Sharfman (1996) analyzed 52 decisions made by the top executives of 24 firms. The decisions were more effective when the executives collected relevant information and used analytical techniques. On the other hand, decisions were less effective when the executives made use of power or hidden agendas. Drucker (2000) suggested that organizational leaders need to self-assess their ethics, engage in constant self-development, be flexible in mentality, and know when to lead and when to follow. A 1992 manual of functions for operations manager, team leader, and supervisor (Anonymous, 1992) included planning, controlling, problem solving, continuous improvement, providing performance feedback, coaching, counseling, and training, creating and maintaining a motivated work environment, and representing the organization.

Overlap between Managing and Leading. This overlap is seen most clearly when one considers the human factor and the interpersonal activities involved in managing and leading. Skill as a leader and in relating to others is a most important requirement at all levels of management. It is clearly recognized at the first level of supervision; it is not as well recognized at the top of the organization. Nonetheless, interviews with 71 corporate executives by Glickman, Hahn, Fleishman, and Baxter (1969) revealed that at the top of a corporation, the group of consequence is relatively small. The group’s members have highly personal relationships. They interact with one another as in a small group. A high proportion of group involvement is usual. Informal procedures supplant formal ones. Consistent with these findings, when Richards and Inskeep (1974) questioned 87 business school deans, 58 business executives, and 40 executives in trade associations about what kind of continuing education middle managers need most, these executives gave top priority to improving human relations skills. They considered improving quantitative and technical skills to be of secondary importance. Similarly, Mahoney, Jerdee, and Carroll (1965) found that the single most important function of first-level managers is to supervise others. The authors recognized eight important managerial functions: planning, investigating, coordinating, evaluating, supervising, staffing, negotiating, and representing. Their questionnaire survey of 452 managers from 13 companies in a variety of industries varying in size from 100 to over 400 employees revealed that more time was spent on supervision than on any other function (28.4%). Supervising, along with the four other functions of planning, investigating, coordinating, and evaluating, accounted for almost 90% of the time that the 452 managers spent at work.

Solem, Onachilla, and Heller (1961) lent further weight to the importance of the human factor by asking 211 supervisors in 26 discussion groups to post and select problems for discussion. In all, 58.8% of the first-level supervisors and 35.3% of the middle managers wanted to talk about subordinates’ motivation to follow instructions, meet deadlines, or maintain the quality of production. Over 40% of the staff supervisors were concerned about dealing with resistance to change, as were 36.4% of the middle managers and 22.7% of the first-line supervisors. The first-line supervisors were most concerned about disciplinary problems and problems of promoting, rating, and classifying employees, while the middle managers were most interested in talking about problems of selecting, orienting, and training employees.

Gilmore (1982) saw leadership as being centrally concerned with the management of boundaries. Managing at the top organizational levels, the leader protects the organization from the risk of subversion by outsiders’ values and practices. At the same time, the leader manages the importation into the organization of opportunities for learning. At the interpersonal level, the leader manages the boundary between maintaining the role requirements of self and others and making decisions based on personal considerations.

Rensis Likert (1961a, 1967) emphasized the linchpin function of managers. As linchpin, the manager connects a group that is composed of the manager’s superior and his or her peers with a group that is composed of the manager and his or her subordinates. For Dagirmanjian (1981), leaders serve as managers by linking the whole organization with their subordinates. The leadership function in nursing was seen by Bernhard and Walsh (1981) to involve coordinating similar activities in two groups: those who seek care and those who give it.

There is a line of reasoning that draws a sharp distinction between leadership and management. It considers leadership to be the discretionary activities and processes that are beyond the manager’s role requirements as mandated by rules, regulations, and procedures. Leadership is whatever discretionary actions are needed to solve the problems a group faces that are embedded in the large system (Osborn, Hunt, & Jauch, 1980). Leadership fits with an organismic view of organizations; management, with a mechanistic view (Terry, 1995). The environment of leaders is more hectic; the environment of managers is more static and stable (Bhatia, 1995). Leaders are more transformational; managers are more transactional. Leaders do the more correct things; managers do things correctly (Parry, 1996). However, Grove (1986) roundly rejected the distinction, stating that the effective manager must have the clarity of purpose and motivation of the effective leader. J. W. Gardner (1986b, p. 7) agreed: “Every time I encounter an utterly first-class manager, he turns out to have quite a lot of leader in him … even the most visionary leader will be faced on occasion with decisions that every manager faces: when to take a short-term loss to achieve a long-term gain, how to allocate scarce resources among important goals, whom to trust with a delicate assignment.” For Gardner (1993), the required distinction is between the leader-manager and the routine manager. Gardner’s leader-manager, in contrast to the routine manager, thinks long-term, can look beyond the unit he or she heads to see its relation to the larger system, and can reach and influence others outside his or her unit. The leader-manager emphasizes vision, values, motivation, and renewal and can cope with conflict. Gardner summed up leader-managers’ tasks as: envisioning the group’s goals; affirming the group’s values, motivating its members; managing; achieving workable unity among the members; explaining what needs to be done; serving as a symbol; representing the group; and renewing the group. Leaders must be able to resolve conflicts, mediate, compromise, and build coalitions and trust. For this they need political skills as well as task and socioemotional competencies (J. W. Gardner, 1988).

Gardner (1990) also noted that senior leader-managers took advantage of the informal network to get information and used their centrality to set agendas, make strategic moves, and mobilize support from allies and from lower-level leaders. According to Zaccaro (2002), senior leader-managers also engage in goal setting, boundary spanning, planning, strategizing, and envisioning. At lower levels, they are responsible for operations and maintenance within their unit. At higher levels, they face more informational and social complexity. They need to search their environment for opportunities and threats. Nonetheless, Krantz and Gilmore (1990) suggested that management and leadership are completely different. Management is idealized as the technique for achieving an organization’s objectives. Leadership is idealized as heroic, visionary, and mission-oriented. The modern leader-manager is more like a team coach who expects a 100% team effort, scouts for talent, and motivates individual initiative and imagination (Conway, 1993). Parry (1996) also listed additional differences between leaders and managers. He cited Australian Prime Minister Bob Hawke as an example of a person who was a transactional manager when meeting with his cabinet and a transformational leader when addressing the Australian public on television.

Leaders manage and managers lead, but the two activities are not synonymous. Leaders facilitate interpersonal interaction and positive working relations; they promote structuring of the task and the work to be accomplished. (E. C. Mann, 1965). All the management functions of planning, coordinating, staffing, and so on can potentially provide leadership; all the leadership activities can contribute to managing. But if trust is a key to leadership, and competence in making decisions is essential to building trust, trust and competence are important in managing resource allocations (Ulmer, 1996). Nevertheless, some managers do not lead, and some leaders do not manage (Zaleznik, 1977). Some leaders are authentic, others are not. In the past century, there has been a decided change in both leadership and management. The autocratic “bridge to engine room management” no longer works (Conway, 1993).

For the military, the leader-manager controversy continues about the importance of leading soldiers rather than managing bureaucratic technological systems. Advancement to senior levels may be due to technological proficiency instead of leadership potential, when the reverse may be needed. As Sarkesian (1985) noted, low-intensity warfare against terrorism and insurgencies calls for leadership and management of fewer large divisions and more smaller brigades and special operations units. Meyer (1983) saw the solution as the development and maintenance of unit-based organizations that make strong, continuing leader-follower relationships possible.

Leadership is path-finding; management is path-following. Leaders do the right things; managers do things right (Bennis & Nanus, 1985). Leaders develop; managers maintain. Leaders ask what and why; managers ask how and when. Leaders originate; managers imitate. Leaders challenge the status quo; managers accept it (Bennis, 1985, 1989). Leaders function in a higher domain of cognitive analysis, synthesis, and evaluation; managers function in a lower cognitive domain of knowledge, comprehension, and application (Capozzoli, 1995). Leadership is concerned with constructive or adaptive change, establishing and changing direction, aligning people, and inspiring and motivating people (Kotter, 1990). Leaders’ behaviors arouse followers’ motives. They are relations-oriented. They set the direction for organizations. They articulate a collective vision. They infuse values and set examples. They sacrifice and take risks to further the vision. They appeal to the self-concepts of their followers. They inspire followers by exhibiting self-confidence, persistence, and determination. They influence their followers through the esteem attributed to them by their followers. They show how much they value their group. They speak for their group. Followers internalize the leader’s expressed values, identify with the group, and can continue without the leader (House, 1995).

Managers plan, organize, and arrange systems of administration and control. They hold positions of formal authority. Their position provides them with reward, disciplinary, or coercive power to influence and obtain compliance from subordinates. The subordinates follow directions from the manager and accept the manager’s authority as long as the manager has the legitimate power to maintain compliance—or the subordinates follow out of habit or deference to other powers of the leader (House, 1995). Management is concerned with consistency and order, details, timetables, and the marshaling of resources to achieve results. It plans, budgets, and allocates staffs to fulfill plans (Kotter, 1990).

The psychoanalyst Zaleznik (1977) stated that leaders and managers differ in how they relate to their roles and their subordinates. Leaders but not managers tend to be more charismalike. Leaders attract strong feelings of wanting to be identified with them. They maintain intense interpersonal relations. Leaders send out clear signals of their purpose and mission; managers tend to be more ambiguous or silent about their purpose. Leaders, but not managers, generate excitement at work. Managers are more likely to see themselves as playing a role; leaders behave as themselves. Leaders are more concerned about ideas to be articulated and projected into images; managers are more concerned about process. Leaders, for Zaleznik, are more likely to be transformational than are managers. On the other hand, managers more readily practice contingent-reward and management by exception; they want to maintain a controlled, rational, equitable system. While managers tolerate the mundane, leaders react to it “as to an affliction.” Managers who combine intuition with rationality as well as the personal characteristics of a leader make the most successful general managers (Kotter, 1982a), middle managers (Kotter, 1985), and senior and lowest-level managers (Kotter, 1988). Based on 900 questionnaires and interviews with executives from 150 organizations, Kotter (1988) concluded that successful managerial leadership requires sophisticated recruiting, early identification of development needs and planning for them, an attractive working environment, challenging opportunities, and support of line management without short-term pressure.

A Leader-Management Model. MacKenzie (1969) illustrated the great variety of activities that a typical manager may perform. Some of them, such as forecasting and budgeting, have relatively less to do with leadership as such (unless the latter is defined most broadly); and some have relatively less to do with management. People, ideas, and things are at the core of the different elements, tasks, functions, and activities that may be part of the manager’s job. These are the basic components of every organization with which the manager must work. According to MacKenzie, ideas create the need for conceptual thinking; things, for administration; people, for leadership. Three functions—the analysis of problems, decision making, and communication—are important at all times and in all aspects of the jobs held by managers. These three functions permeate the entire work process. Also, at all times, managers must sense the pulse of their organization. Other functions occur ideally (but not necessarily in actual practice) in a predictable sequence of planning, organizing, staffing, directing, and controlling. How much managers are involved in these sequential functions depends on their position and the stage of completion of the projects with which they are most concerned. We may quarrel with the idea of limiting leadership to the people element; but, as will be noted later, the administrative and conceptual thinking required are so interlocked with the influence processes that the distinction is of academic rather than practical consequence. However, the sheer diversity of activities and their linkages to the functions and tasks of management are important. This diversity shows the inadequacy of any simple approach to capture what is involved in the managerial and leadership processes. The diversity in how managers and organizational leaders spend their time, with whom they spend it, and what they do has been corroborated by numerous investigators. For example, Stewart (1967) confirmed the diversity of managerial activities when she asked 160 managers to record all job behavior incidents longer than five minutes in duration that occurred for them.

Alignment. Leaders and managers align the objectives of their subordinates and themselves with the goals of the organization to manage innovations, manage resources, lead change, lead learning, and manage the diverse interests of stakeholders. Both leaders and managers make mistakes, but the good ones learn from their mistakes, accept responsibility for them, and try not to make the same mistake twice. They ask the right questions, anticipate crises, and do not allow short-term objectives to interfere with longer-term goals (J. Reynolds, 1994). Gustafson (1999) suggests that an individual-organizational “balanced scorecard” needs to be used by leaders and managers in evaluations. Individual performance appraisals need to reflect what the organization wants to accomplish. Outcome measures can help align operations with strategic goals. Three to five cycles of application are needed for adequate testing and revision of the appraisal framework.

Innovation. Innovations are stimulated by unexpected occurrences, incongruities, process needs, and changes in industries and markets (Drucker, 1991) Leaders need to be alert to these occurrences (Kotter, 1991). Bennis (1991) listed six ways for leaders and managers to foster and support innovation: (1) create a compelling vision; (2) create a climate of trust; (3) create an environment that reminds people about what is important; (4) encourage learning from mistakes; (5) create an empowering environment; (6) create a flat, flexible, adaptive, decentralized organization. Organizational leaders need constancy. They need to practice empowerment and to encourage flatter, adaptive, flexible, decentralized organizations.

Resources. The benefits and costs of resources need to be weighed. Equitable distribution of resources needs to be maintained. Knowledge is an essential resource for leaders and managers. Where technology is important, engineering and science may be necessary. Likewise, in health care administration, medicine or nursing is of consequence. In financial services, accounting, finance, and business law are of equal consequence. Knowledge of marketing, salesmanship, and consumer behavior is needed in the mass retailing and consumer service industries.

Change. Leadership is central to the organizational change process. Sometimes it is managed from the top with little feedback from followers. Other times it may begin with suggestions from supervisors or middle management and their subordinates and work its way up. Envisioning, energizing, and enabling characterize leaders of the change process (Dodge, 1998). An action learning procedure, Organizational Fitness Profiling, can be introduced to provide a guided process for organizational change (Beer, 1997). Changing corporate culture and members’ behavior takes three to ten years. Changes in the culture’s values may enhance the behavior. Change usually begins with corporate strategy set by top management. To implement change, the vision, strategies, and values to be changed are communicated downward. Upward initiatives, feedback modifications, and other inputs are sought from below, from the board of directors, and from relevant outsiders. Needs, required learning, and learning opportunities are assessed, modeled, and rewarded to fit the strategies. The changes are constantly reinforced (Wilhelm, 1992). Beer, Eisenstat, and Spector (1990) proposed a six-step change process: (1) Mobilize commitment to change through joint diagnosis of problems; (2) Develop a shared vision of how to organize and manage; (3) Foster consensus for the new vision and competence in how to begin and continue the change; (4) Begin with the units most ready for change; (5) Spread the change to the other units; (6) Monitor and adjust the process to handle problems that arise in the change effort. Top management must practice what it preaches. Attention to needed change can both create economic value for shareholders in the short term as well as develop an open, trusting culture in the long term (Beer & Nohria, 2000).

To illustrate Weick’s (1988, 1995) theory of how leaders make change meaningful to others and bring about change, Kurke and Brindle (1999) used what Alexander the Great did to enact change in his brief but highly successful conquest of much of the known world. Alexander reframed the problems he faced. For instance, at the time, Tyre was on an island with a strong fleet. Alexander took nine months to build a causeway from the mainland to the island so his soldiers could walk to the island. He used symbolism. It was predicted that whoever untied the Gordian Knot would conquer the world. Alexander cut the knot with his sword. Wherever possible, he made strategic alliances. When he crossed into India and defeated Porus, instead of killing him he made him an ally. He strengthened his identity as ruler of the former Persian Empire rather than the conquering Greek general by adopting Persian garb and ritual and marrying his Macedonian soldiers (and himself) to Persian women. Kirke and Stein (1986) made the case that Alexander’s successful strategies made him great.

Learning. Leading and managing learning include mentoring, modeling, and monitoring the learning of followers. Leaders take a personal interest in the learning of others. They reflect on their experiences, and, where applicable, they define problems using solutions they have already learned. They find time for self-renewal and for serving as catalysts. In learning organizations, leaders continually attend to the learning agenda and institutionalize the commitment to the learning process. They establish routines to receive undistorted feedback. They learn from mistakes and encourage others to do the same (McGill & Slocum, 1994).

Stakeholders. Stakeholders include all those who have an interest in the actions of the organization and the ability to influence it. Stakeholders benefit from leaders and managers who can balance the relative satisfaction of stakeholders’ interests in the corporation: owners, shareholders, management, employees, suppliers, customers, families, community, state, and nation. Leaders and managers need to achieve a consensus from their stakeholders about what and how to do so (Savage, Nix, Whitehead, et al., 1991). Charismatic-transformational leaders and managers can induce change among immediate followers and those at a distance. But transactional leaders can use contingent reward to do the same.

Law Enforcement and Police Officers. These leaders are faced with problems equivalent to those of other public service and not-for-profit managers of the same hierarchical rank. According to Ceballos (1999), they have to deal, in order, with five issues: budgets and funding, developing leaders and managers, advances in technology, community policing, and ethics. Finances depend on how much federal, state, and local governments are involved and how much support can be obtained for developing police managers and executives. New technology, such as DNA testing, is helping investigative police work. Changes in community policies on policing can have dramatic effects on local crime rates. The use of force, accountability, and responsibility are affected by ethical conduct. These same characteristics are relevant to the role of prison warden. The warden is likened to a military commander with lieutenants and sergeants. Wardens learn their roles for this “most arduous occupation” (Bryans & Wilson, p. 191) by word of mouth and by copying role models. They receive little training for the role. There has been little research on their behavior and the relation of their behavior to success and effectiveness in prisons in the United States, and even less in Britain. The Federal Bureau of Prisons’ Institutional Character Profiling, available since 1990, provides a way of assessing institutional stability, the staff’s quality of work life, inmates’ working and living conditions, and relations among the correctional officers. Written tests and simulations are also available for candidate selection (Bryans & Wilson, 2000). In his review of A View from the Trenches: A Manual for Wardens and by Wardens (NAAWS, 1999), Morganbesser (1999) quotes a former warden (Bronson, 1997), who called the warden’s job impossible. The warden’s discretionary authority was likely to be challenged and the warden suffer from burnout. Nevertheless, Cullen et al. (1993) found that wardens had a high level of job satisfaction. According to Morganbesser, considerable efforts are beginning to occur in training for wardens and correctional officers at the National Academy of Corrections and the Federal Bureau of Prisons. These include peer-oriented training, mentoring, and other management development programs. As would be expected of free workers, Gillis, Getkate, Robinson, et al. (1995) found that inmates of a correctional institution who rated their supervisors as transformational had more motivation to work; supervisors rated as laissez-faire leaders correlated with less motivation by inmates to work.

College Presidents. These executives have to engage in many of the same activities as leader-administrators and CEOs. Nonetheless, few are like Father Theodore Hesburgh of Notre Dame in performance and strategy. Over a 35-year period in office, Father Hesburgh’s actions raised Notre Dame’s endowment fund from less than $10 million to more than $300 million. At the same time, he greatly increased Notre Dame’s scholarly mission at the expense of moving football (ordinarily a prime reason for alumni giving) from its preeminent niche to a more appropriate place in the university (Anonymous, 1987).

Finances are seen to be the main issue confronting college presidents (The New York Times, 2005). For Cohen and March (1974), college presidents face a great deal of ambiguity. Their organizations have problematic goals and operate with inconsistent and ill-defined preferences. Their technology is unclear. They use trial and error to operate. The participation of its members varies. The organizational boundaries are uncertain. The presidents must exert leadership on issues of high inertia and low salience for most members in an “organized anarchy.” Bensimon (1988, pp. 3–7) obtained suggestions from interviews with 35 new and experienced presidents about what new presidents should do. They need to: (1) make several visits to their new campus before taking office; (2) get to know and become known to the significant players; (3) read as much as possible about the institution’s operations, procedures, and history and pay attention to them; (4) listen to constituents and observe processes before launching a search for problems; (5) get involved in the budgetary process; (6) accumulate credit for consulting others and being willing to listen before launching change efforts. In a study of 32 institutions of higher education, Birnbaum (1990) found that 75% of newly appointed presidents had faculty support that fell to 25% for presidents who had been in office for a longer time. Those who were able to maintain faculty support throughout their tenure were more likely to seek faculty input. They supported governance structures and an action orientation. They remained totally involved but did not micromanage. Long-term presidents who lost faculty support as well as support from other constituencies, such as the students, the board, and the community, were authoritarian and saw leadership as top down. They outraged the faculty when they took precipitous action without consultation. In evaluating a president, board members and administrators are more favorable in their evaluation compared to other campus leaders; faculty leaders are least favorable (Fujita, 1990).

Nine effective state university presidents and their institutions of higher learning were nominated by experts and compared to 16 representative state university presidents and institutions. The 25 universities had undergone the stress of five successive annual budget cuts. The presidents displayed more transformational leadership based on the Fisher-Tack Effective Leadership Inventory and were more likely to survive (Fisher, Tack, & Wheeler, 1988). Cowen (1990) failed to find that the style of leadership displayed by 153 presidents of four-year public colleges and universities improved student enrollments over a five-year period. However, enrollments did show improvement when the presidents were rated more favorably by their constituents and had been on campus longer.

School Principals. Repeatedly, studies of school effectiveness have shown that the principal’s leadership and management are the keys to a school’s effectiveness (Austin & Reynolds, 1990) and the initiation of improvement and change (Fullan, 1991). Effective school principals must contend with multiple demands placed on them daily. They must be instructional leaders, administrators, head teachers, moral leaders, role models, community workers, social service providers, and even fund-raisers. Time for reflection on needed systematic changes in the school is hard to find (Tewel, 1986). As instructional leader, the principal must be knowledgeable about effective instruction and able to evaluate it (Schlechty, 1990). Allen (1981) formulated a model for the school principal’s performance that showed how successful outcomes for a school depend on the principal’s selection of appropriate roles to enact for a given situation. Support for the model was obtained from panels of experts. The roles played by principals are similar to those of middle managers. They encompass managing resources, ensuring a safe school environment, and maintaining good relations with parents and community (Austin & Reynolds, 1990). Like most managers, they are subject to constant interruptions, lack of time to plan, fragmentation of activities, and the need to comply with rules and regulations that are often statutory (Richardson, Short, Prickett, et al., 1991). In Ontario, principals at all levels of effectiveness cited difficulties with their boards and students. But only the ineffective principals added difficulties with their role and with their community (Leithwood & Montgomery, 1984).

By 1990, principals’ roles were changing, according to 76% to 91% of a survey of 840 mostly principals or assistant principals in Washington State. Increasing were decentralization, diversity requirements, interaction with parents, special education, school community relations, and efforts to monitor truancy (Austin & Reynolds, 1990). According to Lake and Martinko (1982) and Martinko and Gardner (1984a, 1984b), who observed and coded the activities of highly effective and moderately effective school principals, the moderately effective principals spent more time with students and parents but less time with other outsiders than did the highly effective principals. The highly effective principals initiated 64% of the contacts; the moderates, 54%. While 47% of the moderates’ contacts were judged to be human relations–oriented, only 30% of the highly effective principals’ contacts were so judged. Conversely, 66% of the highly effective principals’ contacts were task-oriented; 51% of the moderately effective principals’ contacts were so designated.

Assistant principals serve schools in several ways. According to a study of the work of eight assistant principals in three large comprehensive public secondary schools in Southern California, they: (1) implement state requirements for the curriculum, its master schedule, and the schools’ organizational regularity; (2) prepare the annual extracurricular activity calendar, which involves the values of the local community and the school. In completing this work, their supervisory duties require monitoring, supporting, and remediating (Reed & Himmler, 1985).

“Grassroots” Community Leaders. “Grassroots” leaders are ordinarily involved in a community issue but are less often in the mainstream of institutional leadership. They tend to use unconventional techniques and are motivated more by passion than money, by personal commitment to service, social change, and social justice. Their leadership efforts are often initiated by a struggle. They may be involved because of religious or spiritual beliefs. They are more enthusiastic about shared leadership than about hierarchical leadership (Anonymous, 1999). “Grass roots” leaders can now be mobilized very quickly through the Internet and have become a political force as lobbyists in local, state, and national affairs.

Chapters 4 and 5 described many of the methods that are available for studying leaders as persons. Most of these methods are paralleled by procedures for studying the positions of managers and executives. They include checklists, logs, diaries, and retrospective accounts from interviews, panel discussions, observations, and questionnaire surveys of focal managers and their colleagues. Positions are analyzed, as well as functions, activities, and completed work. The characteristics of the process in which the manager works are another way of analyzing what the manager does. Stewart (1967, 1982b) analyzed the duration of specific activities, the mode of communications used, and the particular persons contacted to detail the characteristics that distinguish among managers’ positions.

Managers’ behaviors may be recorded by observers in a log or by the managers themselves in a diary or rated in response by interviewers. Based on diaries, observations, and interviews, Stewart (1982) proposed that three dimensions could describe any manager’s job: (1) demands—the role expectations set by superiors, rules, policies, deadlines, and situational conditions requiring conformity for survival in the role; (2) constraints—organizational, technological, or environmental conditions limiting the manager’s role and choices; (3) opportunities and activities the manager can freely choose and prioritize. Managers need to reduce the demands and constraints in order to be freer to determine strategies. This may call for interpersonal skills and cognitive competencies. Economic downturns, increased competition, government regulations, and labor unions are some of the sources of external constraints on top management. Their discretion may also be restricted by internal sources such as the legacy of the organization’s founder, the influence of the dominant owner, lack of membership in a family-owned corporation, and the strength of the board of directors (Hambrick & Finkelstein, 1987).

S. Carlson (1951) analyzed self-and assistants’ recordings of the activities of 10 mainly Swedish executives for four weeks. For each action, the recordings noted the site, the person who was contacted, how the communications were conducted (face-to-face or otherwise), the issues involved, and the actions taken. Employing similar records, T. Burns (1957) collected three to five weeks of the diary entries of 76 British top managers. Dubin and Spray (1964) depended on the self-descriptions by eight executives of all “job behavior episodes” over a two-week period, For each episode, they indicated its behavioral content, when it began and ended, who initiated it, with whom the interaction occurred, and how it was conducted. Home and Lupton (1965) made use of checklist records of the activities of 66 managers for a one-week period.

Carlson and James (1971) asked 88 insurance agency managers and 252 supervisors to record their work activities over five weeks and again six months later. Correlations between the first and second measures ranged from .78 to .96, indicating a rather high degree of stability in reported work performance over time. Kelly (1964) used activity sampling in a study of manufacturing executives. His results showed that managers who performed identical functions exhibited similar activity profiles. Likewise, Stogdill and Shartle (1955) asked U.S. Navy officers to keep a minute-by-minute log of their activities for a period of three days. After the logs were collected, the officers were asked to estimate the percentage of time they had spent in different activities during the period. The correlations between logged time and estimated time were computed. The results indicated a fairly high correspondence between logged time and estimated time for objectively observable performances such as talking with other persons, reading and answering mail, reading and writing reports, and operating machines. Less objective, less readily observable forms of behavior, such as planning and reflection, failed to yield estimates that corresponded highly with logged time. Nor was there a high correlation between logged and estimated behavior for infrequent activities such as teaching and research. Carroll and Taylor (1968, 1969) collected brief self-reports from 21 managers on what they were doing at a randomly selected minute during each half hour of a period of investigation. The same information for the 21 managers was provided as the time estimates and other observational methods used by an outside observer. Komaki, Zlotnick, and Jensen (1986) introduced further sophistication into observational procedures by using micro analytical coding procedures that were again based on careful time sampling.

Content Analysis of Biographies of Organizational Leaders. Van Fleet and Peterson (1995) created the Career Description Analysis, a procedure for content analysis of biographies and autobiographies of organizational leaders. For instance, of 10 military leaders, Generals Omar Bradley (14%) and Dwight Eisenhower (11%) were considerably higher in their percentages of frequency of clarifying work roles and objectives than were Marine General Alexander Vandergrift (5%) and General George Patton (4%). Most frequently inspiring of 14 business leaders were Mary Kay Ash (12%) and Thomas Watson, Sr. (11%), compared to John DeLorean (3%) and Alfred P. Sloan (2%).

Case Studies. Qualitative studies of individual or multiple cases that might include quantitative data were popularized as the method of choice for professional education by the Harvard Business School. It was influenced by the use of legal cases for setting precedents and educating lawyers and judges. Hunt and Ropo (1995) demonstrated that with a suitable conceptual framework, a case could generate testable propositions. For example, in the case of Roger Smith’s tenure as CEO from 1981 to 1990 at General Motors, they proposed that the availability of vast amounts of resources tends to encourage bold but not necessarily wise decisions. Other propositions concerned Smith’s limited behavioral complexity, critical tasks, and organizational culture.

Critique. Despite the face validity of observational approaches, Martinko and Gardner (1985) found a number of shortcomings in them. First, because sample sizes are usually small, the result is the questionable generalizability of conclusions. Second, such approaches often lack adequate reliability checks. Observers need to take account of the multiple purposes of a single action, whose coding is often unreliable. Third, observational reporting is usually simplistic, mechanistic, and narrow in perspective and tends to ignore variations among positions and their situational circumstances. Fourth, such approaches fail to remain consistent in using an ideographic, longitudinal, or case-by-case orientation or a nomothetic approach that aggregates and averages observations across individual positions and situations.

Self-reporters and observers are likely to miss many fleeting, transient actions. Usually, observers can only infer the manager’s purposes and the intentions of a manager’s observable action. Moreover, much of a manager’s behavior is cognitive and unobservable (Stewart, 1965). Observational studies need to be buttressed by interviews and questionnaires using larger samples.

Extensive interviews precede the development of custom-made questionnaires if suitable questionnaires are not already available. A sample of senior managers might be interviewed for developing questionnaires about work done. A cross-sectional sample of the hierarchical levels and functional areas would be needed for developing a questionnaire about the work done by supervisors, managers, and executives. The questions may be structured, with alternative possible answers provided, or with an open-ended section, with respondents free to answer in their own words. Then managers or their associates can be asked to complete the structured questionnaires organized by clusters, factors, or dimensions of activities in which ratings are made of how much time the managers spend on the different functions, tasks, and activities; with whom they spend their time; and in what ways. Illustrative are investigations by Allen (1981), Korotkin and Yarkin-Levin (1985), and Sperry (1985). Allen collected self-rated questionnaire descriptions from 1,476 New York City government managers about their tasks. Korotkin and Yarkin-Levin used both interviews and questionnaires to generate lists of tasks describing the required activities of U.S. Army commissioned and non-commissioned officers. Sperry held a series of discussions with senior federal career managers to obtain information about their role orientation and job problems.

Questionnaires for describing positions have been used extensively. Hemphill (1960) used the Executive Position Description Questionnaire (EPDQ) to examine the positions of 93 business executives located in five companies. The positions represented three levels of organization and five specialties (research and development, sales, manufacturing, general administration, and industrial relations). Data were obtained on 575 items that were classified as: (1) position activities, (2) position responsibilities, (3) position demands and restrictions, (4) position characteristics. Correlations were computed between positions: (1) within each organization, (2) within each level of the organization, and (3) within each specialty. Again, systematic differences were associated with differences in the hierarchical levels in which the positions were located. The results indicated a greater degree of similarity between positions in the same specialty but were different at different levels. Hemphill also factor-analyzed the correlations among the 575 items. Ten factors emerged: (1) providing a staff service for a nonoperational area; (2) supervising work; (3) business control; (4) technical (markets and product); (5) human, community, and social affairs; (6) long-range planning; (7) exercise of broad power and authority; (8) business reputation; (9) personal demands; and (10) preservation of assets.

With a heavier emphasis on the functional responsibilities of different managerial positions, Tornow and Pinto (1976) developed the Management Position Description Questionnaire (MPDQ) to provide a similar analysis for higher-level managers. Thirteen functions and associated work done for executives could be differentiated and evaluated. These were (1) product, marketing, and financial strategy planning—long-range thinking and planning; (2) coordination of other organization units and personnel—coordinating the efforts of others over whom one exercises no direct control; (3) internal business control—reviewing and controlling the allocation of personnel and other resources, cost reduction, performance goals, budgets, and employee relations practices; (4) products and services responsibility—planning, scheduling, and monitoring products and the delivery of services; (5) public and customer relations—promoting the company’s products and services, the goodwill of the company, and general public relations; (6) advanced consulting—application of technical expertise to special problems, issues, questions, or policies; (7) autonomy of action—discretion in the handling of the job, making decisions that are most often not subject to review; (8) approval of financial commitments—authority to obligate the company; (9) staff service fact gathering—the acquisition and compilation of data and record keeping for a higher authority; (10) supervision—getting work done efficiently through the effective use of people; (11) complexity and stress—handling information under time pressure to meet deadlines, frequently taking risks, interfering with personal or family life; (12) advanced financial responsibility—preservation of assets, making investment decisions and large-scale financial decisions that affect the company’s performance; (13) broad personnel responsibility—management of human resources and the policies affecting it. Tornow and his colleagues continued this line of investigation for 11 years in different industries, for different organizational levels, and in upward of 20 countries involving more than 10,000 managers. The instrument they validated, the MPDQ, contains about 250 items of required activities, contacts, skills, knowledge, and abilities. In rating each item to describe the management position, the job analyst weighed the importance, the criticality, and the frequency of occurrence of the item. Managers indicated that 85% of their jobs were adequately described by the items of the MPDQ, according to managers in both the United States and foreign countries (Page, 1985, 1987).

Profiles of Managerial Positions. Managerial positions can be usefully profiled on factors and compared with norms for the different levels of management. Seven large-scale studies that searched for factor analytic solutions were carried out in a variety of industries, including banking, manufacturing, and retailing. Seven types of these factors consistently emerged across these studies: (1) planning, (2) controlling, (3) monitoring business indicators, (4) supervising, (5) coordinating, (6) sales/marketing, and (7) public relations and consulting (Page & Tornow, 1987). In the profiles of the factor scores for the positions of 108 executives, 125 managers, and 196 supervisors, executive positions stood out in their planning, controlling, and monitoring business indicators and in their public relations activities. Supervisors’ positions differed the most from those of the managers and executives in supervisory activities and their relatively low scores in comparison to the others on most of the other factors. The managers’ position tended to come closer to those of the executives in planning, controlling, coordinating, and consulting and closer to the supervisors in public relations.

Consistent with these findings, a factor analysis reported by Dunnette (1986) of 65 managerial tasks yielded factors, including: (1) monitoring the business environment; (2) planning and allocating resources; (3) managing individuals’ performance; (4) instructing subordinates; (5) managing the performance of groups; (6) representing the groups. Comparisons among 574 first-level, 466 middle-level, and 165 executive-level managers indicated that as the hierarchical level increased, so did the managers’ functions of monitoring the business environment and coordinating groups. At the same time, the instruction of subordinates and the management of individual performance decreased.

Yukl, Wall, and Lepsinger (1988) reported on the development and validation of the Managerial Practices Survey (MPS). The survey focused on managerial behavior, i.e., “answers requests, invites participation, determines how to reach objectives, assigns tasks, praises, facilitates the resolution of conflicts, and develops contacts.” Colleagues and job incumbents rated the importance and relevance of each behavior to carrying out the manager’s responsibilities effectively. The 1988 version (Yukl, 1988, 1989, 2002) was grouped into 11 scales. The scales were developed using factor analysis and judges’ categorizations of the items. The 11 scales assessed the following behavioral dimensions: informing, clarifying, monitoring, problem solving, planning and organizing, consulting/ delegating, motivating, recognizing/rewarding, supporting, networking/interfacing, and conflict management/ team building.

Managerial Role Activities. Empirically obtained managerial roles by Hales (1986) and Page and Tornow (1987) included disturbance handling, innovating, sales/ marketing, public relations, and labor relations. Morse and Wagner (1978) used a modified list of nine of Mintzberg’s (1973)1 managerial roles (see below) to classify managerial activities in a descriptive questionnaire. After several refinements by means of factor analysis, they constructed a list of 51 activities that could be used by managers to evaluate the effectiveness of another manager with whom they worked closely. By rating a manager on each activity, a colleague could evaluate the manager’s behavior. Six extracted factors covered the original nine role activities: (1) managing the organization’s environment and its resources (effective managers are proactive and stay ahead of changes in their environment; basing plans and actions pertaining to the organization’s resources on clear, up-to-date, accurate knowledge of the objectives of the company), (2) organizing and coordinating (effective managers fit the amount of formal rules and regulations in their organizations to the tasks to be done and to the abilities and personalities of the people doing them; these managers are not difficult to get along with or to coordinate with), (3) information handling (effective managers make sure that information entering the organization is processed by formal reports, memos, and word of mouth on a timely basis so it is usable and current and provides rapid feedback; they make sure that the person who has to use the information clearly understands it), (4) providing for growth and development (effective managers ensure, through career counseling and careful observation and recording, that their subordinates grow and develop in their ability to perform their work; they guide subordinates by commending the subordinates’ good performance); (5) motivating and conflict handling (effective managers transmit their own enthusiasm for attaining organizational goals to others; they are not plagued by recurring conflicts of a similar nature that get in the way of associates’ efforts to perform their jobs), (6) strategic problem solving (effective managers periodically schedule strategy and review sessions involving the design of projects to improve organizational performance and to solve organizational problems; they spend considerable amounts of time looking at their organization for problem situations and for opportunities to improve their subordinates’ performance).

Managers are often required to allocate or recover resources. They need to understand the rules involved. Allocators generally favor giving and taking back resources based on needs. Equality is favored particularly when resources are to be recovered. Generally, recovery decisions are harder to make than allocations. Monetary and facilitative resources tend to be most difficult to allocate (Parks, Conlon, Ang, et al., 1999). Evaluations of 231 managers by colleagues were higher for better-performing managers on all six dimensions in three of six offices, according to objective criteria such as net profit, data budgeting, and the volume of customer billing. The evaluations were correlated between .41 and .65 with superiors’ rankings of how well the managers were performing. Multiple regression analyses indicated that the managerial activities that were of most consequence to the end results were, first, managing the organization’s environment and resources; and, second, motivation and conflict handling. But the consequences depended on the organization’s objectives. Thus, according to multiple regressions, in contrast to other kinds of firms, in a data processing firm, accounting and handling financial records for clients, information handling, and strategic problem solving by the managers contributed the most to the appraised performance of the managers by their superiors. A similar line of investigation was completed using the Management Practices Survey (MPS). Yukl and Kanuk (1979) showed that for 151 employees of beauty salons who described their salon managers, the average monthly profit margins of the salons correlated .47 and .49, respectively, with the extent to which managers were seen to engage in clarifying and motivating activities.

Numerous other examples can be provided. Thus cadet sergeants’ clarifying and motivating correlated .26 and .30, respectively, with the performance of the ROTC units for which they were responsible (Yukl & Van Fleet, 1982). Problem solving and recognizing/rewarding correlated .39 and .42, respectively, with the behavior of managers when the managers were responsible for the performance of insurance salespersons in retail department store outlets (Yukl & Carrier, 1986). For 24 school principals studied by Martinko and Gardner (1984b), whose managerial behavior was described by their school-teachers, again problem solving, clarifying, monitoring, and motivating correlated with effectiveness (between .36 and .49), as did networking/interfacing (.47). Miles (1985) found that these and the other 13 scales of activities of the MPS by 48 directors of home economics programs correlated between .21 and .42 with the quality of the county programs they administered. Similar results were found for department heads.

A Behavioral Checklist Analysis. Tsui (1984) pointed out that a manager’s reputation for effectiveness depends on satisfying at least three constituencies: superiors, peers, and subordinates. The performance appraisals earned by a manager, merit pay increases, rate of promotion, and career advancement were highest when the manager’s reputation for effectiveness was high among all three constituencies. Such threefold reputational effectiveness correlated with behavioral checklists of roles taken by a sample of managers. Mean correlations for the threefold reputational effectiveness of managers and the extent to which the managers engaged in each of six Mintzberg roles were as follows: leader (.45), liaison (.23), entrepreneur (.37), environmental monitor (.34), resource allocator (.37), and spokesperson (.35). Multiple regression analyses indicated that almost 30% of the reputational effectiveness could be accounted for alone by the extent to which managers engaged in the roles of leader and entrepreneur. Expected differences emerged, however, among the constituencies in what role activities were important for reputational effectiveness. In a subsequent study, Tsui and Ohlott (1986) found that the various constituencies had similar models of the elements of managerial effectiveness but differred on the relative importance to attach to each. The roles of leader and entrepreneur (planner, controller, implementer of change) were most salient for managerial effectiveness in their models of what was important in the role repertoire of the focal manager they described.

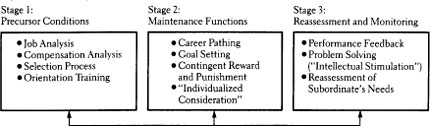

A Three-Stage Model of Effective Leader-Managers. Neider and Schriesheim (1988) developed a three-stage model that is presented in Figure 23.1. The three stages deal with precursor conditions, maintenance functions, and reassessment and monitoring. Precursor conditions are the organizational functions and tasks that take place to set the stage for effective leadership and management. They include a thorough job analysis, detailed compensation analysis, good selection strategies, and sound orientation training of the subordinates. In the first stage, effective leaders pay attention to the data necessary to clarify fully for subordinates how their efforts will result in the attainment of the objectives of the job. Equity and desired rewards that are contingent on performance are key considerations. Effective leaders ensure that the subordinate’s knowledge, skills, and abilities match the requirements of the job. The second stage involves career pathing for the subordinate, goal setting, and performance-contingent and individualized consideration focused on the development of the subordinate through suitable delegation. Both the subordinate’s self-esteem and the organization’s attractiveness to the subordinate are thus enhanced. In the third stage, the effective leader provides feedback and meetings at which the alignment of the subordinate’s needs and performance with the organization are reassessed and misperceptions are corrected. Here, intellectually stimulating leadership helps solve the subordinate’s problems.

Figure 23.1 A Diagnostic Model of Effective Leadership

SOURCE: Neider and Schriesheim (1988).

Critical Incidents. Flanagan (1951) originated the critical incidents technique. Respondents describe incidents of effective and ineffective job performance they have observed or in which they have been involved. The technique was applied to a study of the jobs of U.S. Air Force officers and research executives. It was possible to classify the incidents under the following major headings: supervision, planning and direction, handling of administrative details, exercise of responsibility, exercise of personal responsibility, and proficiency in a given specialty. In the same way, Wallace and Gallagher (1952) analyzed the job activities and behaviors of 171 production supervisors in five plants. They collected and classified 3,765 behavioral incidents by the topic involved, location of the incident, person contacted, and nature of the foreman’s behavior during the incident. Along similar lines, Williams (1956) and Kay (1959), among others, were able to describe managerial jobs in terms of critical requirements. Williams collected more than 3,500 incidents from a representative sample of 742 executives who were distributed proportionally by industry, company size, and geographic location. Kay collected 691 critical incidents of foremen’s behavior from managers and rank-and-file employees.

According to a review by Carlson and James (1971) of the various methods employed to study what managers do, how they spend their time, and what functions they perform, adequate reliabilities and validities have been obtained.2 Nonetheless, systematic biases can be seen.

Substantive Problems. An obvious error occurs if the description is more about a particular job incumbent than about the position as it is and should be performed by the average or typical incumbent. Another bias is due to the fact that managers in a hierarchy think they have a bigger job than their immediate superiors think they have. At the same time, managers think their subordinates have smaller jobs than the subordinates think they have (Haas, Porat, & Vaughan, 1969). The importance of the position and its duties depends on who is describing them. Several investigations corroborated this fact.

Brooks (1955) asked 96 executives, their superiors, and their subordinates to rate the work performed by the executives as indicated by 150 functional items. The executives rated themselves higher than they were rated by their subordinates in such activities as defining authority, delegating, planning, and showing how jobs related to the whole picture. Again, supervisors and subordinates differed in the requirements they saw for other aspects of the supervisor’s job. According to Sequeira (1964), supervisors perceived that they were required to perform duties that did not legitimately belong to their jobs. Among these duties were: training new workers on the job, arranging wage agreements, and checking supplies. Workers expected their supervisors to do more than the supervisors required of themselves in settling personnel problems and grievances, clarifying work difficulties, and improving work methods and conditions. A study by Yoga (1964) of 11 plants in India in three industries (textiles, processing, and engineering) yielded similar results.

Methodological Problems. According to McCall, Morrison, and Hanman (1978), managers’ behavior is usually described in global dimensions, such as planning and controlling, instead of actual observable behaviors because so many studies depend on interviews or questionnaires of the managers themselves. The results are then summarized with factor analyses. The responses of the managers provide only indirect information about what the managers do. This is in contrast to observations of what they actually do. The self-reports deviate considerably from observations and records of their behav-ior (Horne & Lupton, 1965; Kelly, 1964)—although as noted before, Navy officers could accurately estimate the logged time they spent on observable activities. Diaries, as self-reports, are also likely to deviate from summary estimates as well as from independent observers’ descriptions (T. Burns, 1954). “Managers are poor estimators of their own activities” (Mintzberg, 1973, p. 222). Thus, as Lewis and Dahl (1976) point out, although 12 university administrators estimated in a summary judgment that they had spent 47% of their time in meetings, their diaries for five weeks indicated that they had spent 69% of their time in such meetings (Lewis & Dahl, 1976).

The discrepancy between what managers say they do in response to questionnaires and what they actually do is to be expected. Managers do not consciously plan ahead to summarize all their activities in a retrospective survey. “Managerial work activities are fragmented, brief, diverse, fast-paced and primarily oral, [and] the sheer volume and nature of activities seriously hinder a manager’s efforts to conscientiously observe and purposively memorize activities for accurate reporting on a future survey” (McCall, Morrison, & Hanman, 1978, p. 27). Furthermore, regardless of the self-reporting method used, social desirability is likely to inflate results (Weiss, Davis, England, & Lofquist, 1961). As with many other methodological problems, for confidence in the conclusions reached, the solution usually lies in using multiple methods that combine self-colleagues’, and observers’ reports with a mix of logs or diaries and interviews or questionnaires.

Personal Preferences. Different managers can occupy a position with the same requirements yet display considerable differences in how they fulfill their responsibilities. Stewart (1976b) observed that the activities of incumbents in management positions with the same function and at the same level varied considerably because managerial jobs have a certain amount of choice beyond the basic demands of the job. To a considerable degree, managers can work on tasks of their choosing and when they want to. Stogdill and Shartle (1955) pointed out that regardless of the different requirements of the new position to which they were transferred, naval officers spent the same amount of time on some activities in both po sitions. In the same way, Castaldi (1982) found that seven of ten CEOs who headed companies of the same size in the same industry (small furniture manufacturing) agreed about the importance they attached to operational activities. The seven attached more importance to strategic activities only. The majority’s emphasis on strategic activities was seen to be a consequence of the static technology of the furniture industry, the strong competitiveness among firms, and the long tenure of the CEOs.

Most studies have focused on how managers spend their time, what work they do, and what roles they play. The frequency, importance, and criticality of these factors have been the usual gauges of consequence. Clearly, according to diaries and observational studies, managers work long hours, ranging from 50 to 90 hours per week, some of which may be carried on outside the office. Senior managers work longer than do lower-level managers but on fewer activities. Those with well-defined functions, such as accounting managers, can work fewer hours (McCall, Morrison, & Hanman, 1978). Shipping supervisors differ systematically from production supervisors in the time they spend in planning and scheduling work and in maintaining equipment and machinery (Dowell & Wexley, 1978).

With his background as a former director of research on job and occupational information, Shartle (1934, 1949b) suggested that executive work could most meaningfully be quantified in terms of the amount of time devoted to various activities. Stogdill and Shartle (1955) compared the time use profiles of 470 U.S. Navy officers and 66 business executives. They found that both groups spent more time (about 34%) with subordinates than with superiors or peers. Furthermore, both groups devoted about 15% to 20% of their time to inspections, examining reports, and writing reports, and spent somewhat more time in planning than in other major administrative functions. The profiles suggested a high degree of similarity in administrative work between military and business organizations. Similarly, Jaynes (1956) analyzed variations in the performance of 24 officers in four submarines and 24 officers who occupied identical positions in four landing ships. He reported that variance in performance was more closely related to the type of position than to the type of organization in which the position was located.

In the previously cited study of executives in Sweden, S. Carlson (1951) found that they spent about 20% of their time in internal and external inspections and almost 40% of their time acquiring information. The remainder of their time was divided about equally among advising and explaining, making decisions, and giving orders. Most of the executives felt overworked, complaining that they had little time for family or friends. According to Horne and Lupton’s (1965) study of 66 managers, a large percentage of a manager’s time is spent in discussions with others—44% informally, 10% in formal meetings, and 9% on the telephone. In contrast, only 2% is spent in reflecting, 10% in reading, and 14% on paperwork. At least half these activities occur in the manager’s own office. The most frequent purposes are to transmit information (42%), discuss explanations (15%), review plans (11%), discuss instructions (9%), review decisions (8%), or give and receive advice (6%). Mowll (1989) found in a study of more than 1,200 health care patient account managers that they spent more than 30% of their typical day supervising their departmental staff. Their effectiveness depended on how well they allocated their time and motivated their staff. As will be discussed in Chapter 29, by the 1990s, these percentages had to be adjusted due to the fact that managers were spending an increasing amount of their time on e-mail, the Internet, and their organizations’ intranet.

Time Spent on Activity by Position. Stogdill, Shartle, Wherry, and Jaynes (1955) studied 470 U.S. Navy officers in 45 different positions or job categories. The officers were located in 47 different organizations. Data were obtained from all officers on the percentage of their working time that was devoted to the performance of 35 tasks, including personal contacts, individual efforts, and handling other major responsibilities. The results were related to the officers’ level in the organization, military rank, scope or responsibility, scope of authority, and leadership behavior. Stogdill, Wherry, and Jaynes (1953) factor-analyzed these naval officers’ profiles to cluster the positions of officers doing similar work, such as public relations directors, coordinators, and consultants. Then, they correlated the scores for the specialties with how occupants spent their time. Eight factors emerged from the analysis: (1) high-level policy making, (2) administrative coordination, (3) methods planning, (4) representation of members’ interests, (5) personnel service, (6) professional consultation, (7) maintenance services, and (8) inspection. The officers clustered in terms of how their assignments and activities made use of their time. The clusters were (1) technical supervisors (teaching, supervising, using machines, and computing); (2) planners such as operations officers (scheduling, preparing, procedures, reading technical publications, interviewing personnel, and consulting peers); (3) maintenance administrators (interpreting, consulting, attending meetings, and engaging in technical performances); (4) commanders and directors (representing, inspecting, and preparing reports); (5) coordinators, such as executive or staff officers (consulting juniors, supervising, scheduling, examining reports, and interviewing personnel); (6) public relations officers (writing for publication, consulting outsiders, reflecting, and representing); (7) legal or accounting officers (consulting juniors, professional consulting, interpreting); and (8) personnel administration officers (attending meetings, planning, and interviewing personnel).

T. A. Mahoney (1955) plotted the time usage profiles of 50 company presidents against those of 66 business executives reported by Stogdill and Shartle (1956). The two profiles were almost identical. T. A. Mahoney (1961) next analyzed the performance of 348 business executives in terms of eight functions. The performances with the percentage of time devoted to them were as follows: supervision (39%), planning (18%), generalist (14%), investigation (8%), coordination (6%), negotiation (5%), evaluation (4%), and miscellaneous (7%). Similar patterns of time usage were reported by Mahoney, Jerdee, and Carroll (1965) for a sample of 452 managers drawn from all organizational levels. A minimum amount of time was spent on each of these functions, although the percentage varied as a function of hierarchical level. For example, at lower hierarchical levels, more time was spent in supervision. At higher levels, more time was spent in planning. Replicated by Penfield (1975), these results were consistent with Stogdill, Shartle, Wherry, and Jaynes’s (1955) findings for naval officers, and Haas, Porat, and Vaughan’s (1969) findings for bank officials. Fleishman (1956) used the same kinds of data to analyze the differences between administrators in military and industrial organizations. He observed that differences between the patterns of administrative performance in industrial and naval organizations were generally no greater than differences within the two types of organizations. Taken together, all these studies indicated that time profiles of managerial positions tend to shift systematically with the hierarchical level of positions and the functional role of the positions in the organization. The patterns of time spent tend to be similar for positions that are comparable in level and function in different types of organizations.

Yukl (1998) concluded that managers need to understand the demands and constraints on their time. They need to know what others expect of their time. They need to appreciate what priorities in the use of their time are expected of them by subordinates, colleagues, and their superior. But they also need to be proactive in taking a broader perspective on how to spend their time aligned with organizational strategies. They need to make time for reflection, planning, daily and weekly activities, and avoiding procrastination.

Contrary to both popular and classical images of management, much more managerial work involves handling information than making decisions. McCall, Morrison, and Hanman (1978) reached this conclusion from diaries and observational studies by Brewer and Tomlinson (1964) and Horne and Lupton (1965). As Carroll and Gillen (1987) noted, the simple classical view of the manager as one who gets work done through prescribed and orderly planning, organizing, and controlling has given way to a more complex romantic view, stimulated by the work of Mintzberg (1973), which is detailed below. Instead of the prescribed best ways to fulfill the managerial role, what we now have is a picture of harried executives putting out fires on demand, rather than systematically carrying out their prescribed functions in an orderly fashion. Both Guest (1956) and Ponder (1958) reached similar conclusions earlier from observational studies of production supervisors who had to handle a variety of problems quickly. One problem followed another with less than a minute for each on the average. More than 50% of the supervisor’s time was spent in face-to-face interactions, more often with subordinates than with outsiders, although the supervisors had more total contacts with the latter. Landsberger (1961) also noted at the middle-management level the same pattern of brief, varied, and fragmented activities with much lateral interpersonal interaction.

Numerous other empirical investigations revealed a great variety in the functions describing what managers actually did. Managers do not behave according to textbook requirements for orderliness, planning, optimum decisions, and maximum efficiency. Rather, managerial processes, according to Mintzberg’s (1973) in-depth study of five executives, are characterized by brevity, variety, and discontinuity. Managers rely on judgment and intuition, rather than on formal analysis, which makes it difficult to observe clearly their decision making processes. Kurke and Aldrich (1983) supported Mintzberg’s conclusions in a complete replication with four CEOs for one week. Yet Snyder and Glueck (1977), in a replication of Mintzberg’s (1973) study, found managers to be more careful planners. But brevity in any one activity, interruptions of that activity, and discontinuity from one activity to the next were characteristic of what was gleaned from managers’ diaries, recordings, and observations (Mintzberg, 1973). Although planning was regarded as a key element in the classical view of management, managers at all levels, according to diaries and observation, actually spent less time at it because of interruptions and demands on their time for other activities (McCall, Morrison, & Hanman, 1978). Mintzberg concluded that managers were oriented toward action, not reflection.