Most executives who make it to the top of their organizations are highly task-oriented. But many are also inclined to be concerned with their relationships. Ten CEOs and managing directors of divisions in a large, multinational firm were identified by a group of senior executives at the firm’s headquarters. Vansina (1982) carried out a qualitative description of the 10 leaders using semistructured taped interviews that were subsequently content-analyzed. The 10 leaders were selected for their consistently “excellent performance in different business situations in different parts of the world” (p. 2). Vansina inferred that the leaders worked through people for whom they cared. They wanted to create an operating climate in which employees at every level in their organization knew what they were working for and what tasks needed to be done. Concerns about tasks and relationships were to be met by providing members with the appropriate means, authority, knowledge, and resources. The leaders had a keen interest in spotting and developing young talent and a low tolerance for poor performers. To establish organizational commitment, they saw their need to develop personal and professional relationships and collaboration through personal example, consultation, and removal of obstructions and incompetent people. They kept actions simple and followed them up to monitor progress. They carefully managed the linkages between headquarters and key persons, and between business objectives and social responsibilities. They were self-confident, responsible, and open-minded. They learned the local language and had direct contact with employees.

Concern for task and relations was illustrated by Andrew Grove, CEO of Intel, known for his innovation in the design and manufacture of computer chips. His egalitarianism came from his escape from Hungary during the Nazi occupation. For him, America was symbolized by respect for intellect and for others as human beings. The culture of Intel he initiated combined informality in relationships, high standards, and hard work (Tolkoff, 1998). Also equally concerned about tasks and relationships, Robert E. Wood changed Sears from solely a mail-order business into a chain of retail stores with a strategy of meeting customer needs, buying to specification, building good relations with suppliers, and creating an image of each store as local rather than as part of a chain. He instituted a radically different hierarchy for a large organization. There were only five echelons between the salesclerk and the CEO. His belief in decentralization was buttressed by the need for employees and managers to grow and learn from their mistakes (Worthy, 1984).

Leaders differ from each other in their focus of attention. Some focus more on the task to be accomplished, others more on the quality of their relations with others (Blank, Weitzel, & Green, 1990), and still others more on change. Bergan (1986) observed leaders concentrating on their group’s working methods or on mutual trust building. Ekvall and Arvonen (1991) added that leaders may also concentrate on making changes. Effective leaders do any of these things, or all three. For instance, when Berkowitz (1953a) asked members of air crews to describe their commander with a behavioral description inventory, a factor analysis of the results revealed factors concerned with both task and relationships, including maintaining standards of performance, acting on an awareness of situational needs, maintaining coordination and teamwork, and behaving in a nurturant manner. The conceptualizations may be universal. Thus Shenkar, Ronen, Shefy, et al. (1998) reported that the Chinese manager’s role could be partly accounted for by attention to task-related and relations-oriented activities.

Task-oriented leaders differ in their concern for their groups’ goals and the means to achieve the goals. They engage more in task roles (Bass, 1967b; Fiedler, 1967a). They are more concerned with production (Blake & Mouton, 1964) and need for achievement (McClelland, 1961; Wofford, 1970). They are identified as achievement oriented (Indvik, 1986b), production oriented (Katz, Maccoby, & Morse, 1950), production-emphasizing (Fleishman, 1957a), goal achieving (Cartwright & Zander, 1960), work facilitative, goal emphasizing (Bowers & Seashore, 1966), performance planning and performance pressuring (Misumi, 1985; Peterson, Smith, & Tayeb, 1993). The leaders’ assumptions about their roles, purposes, and behavior reflect their interest in completing assignments and getting the work done. A high task orientation underlies selected types of leaders, such as Birnbrauer and Tyson’s (1984) hard driver and persuader or Reddin’s (1977) autocrat. Purely task-oriented leaders are likely to keep their distance psychologically from their followers and to be more cold and aloof (Blau & Scott, 1962). When coupled with an inability to trust subordinates, their concern for production is likely to manifest itself in close, controlling supervision (McGregor, 1960). Successful task-oriented leaders are instrumental in contributing to their groups’ effectiveness by setting goals, allocating labor, and enforcing sanctions (Bales, 1958a). They initiate structure for their followers (Hemp-hill, 1950a), define the roles of others, explain what to do and why, establish well-defined patterns of organization and channels of communication, and determine how to accomplish assignments (Hersey & Blanchard, 1981). Chapter 18 provided illustrations of executives—Jack Welch and Lou Gerstner—who were highly task-oriented and less concerned about interpersonal relationships.

Conceptions. Task-oriented leadership can be a source of expert advice and challenging motivation for subordinates. Misumi (1985) conceived of task-oriented leadership behavior as performance leadership—behavior that prompts and motivates the group’s achievement of goals. For example, when deadlines are necessary, the leader clearly specifies them and has a good grasp of how work is progressing. According to Cleveland (1980), such a focus on the task is seen in strategic thinking, in projecting patterns of collective behavior, and in considering the whole situation. It is also seen in the leader’s manifest curiosity about issues and methods and the system that can connect people and things to achieve objectives. Akin and Hopelain (1986) described a “culture of productivity” in three highly productive organizations. Immediate supervision, combined with management as a whole, can foster a shared image of a highly productive work setting in which supervisors, managers, and workers alike focus on the work being done and how to maintain successful operations.

Purposes. Yukl (1994) proposed five purposes of task-oriented leader behavior: (1) to propose an objective, introduce a procedure, present an agenda, and redirect attention to the task; (2) to stimulate communication, seek specific information, or encourage the introduction of new ideas; (3) to clarify communication, reduce confusion, ask for interpretations, and show how different ideas are related; (4) to summarize accomplishments, to review or ask for reviews; and (5) to test for consensus about objectives, interpretations, evaluations, and readiness for decisions.

Caveat. Although the various conceptualizations of task orientation have similar-sounding labels, their inter-correlations are not necessarily high. In fact, they may point to different attributes of an individual. Thus the direct assessment of the task orientation of 81 Polish industrial personnel—using the Orientation Inventory (ORI), which directly asks examinees for their preferred activities—correlated only 32 with the need for achievement as measured by the Thematic Apperception Test, an assessment of the projected fantasies of the same examinees (Dobruszek, 1967). Similarly, Fiedler’s (1967a) determination of task orientation, based on the leaders’ rejection of the coworker with whom they found it most difficult to work, did not correlate as highly with other approaches to measuring task orientation. (In fact, the least preferred coworker, or LPC, measure seems so unlike any other that it will be treated separately in this chapter.) Thus it is necessary to review results in the light of variations that are due to how task orientation and relations orientation are measured.

Concept. Relations-oriented leadership is expressing concern for others, attempting to reduce emotional conflicts, harmonizing relations among others, and regulating participation (Yukl, 1994). Relations-oriented leadership is likely to contribute to the development of followers and to more mature relationships.

Leaders differ in the extent to which they pursue a human relations approach and try to maintain friendly, supportive relations with their followers. They are identified as relations-oriented (Katz, Maccoby, & Morse, 1950), concerned for maintenance (Misumi, 1985) or group maintenance (Cartwright & Zander, 1960; Wof-ford, 1970), concerned for people (Blake & Mouton, 1964), people centered (D. R. Anderson, 1974), interaction facilitative and supportive (Bowers & Seashore, 1966), interaction oriented (Bass, 1967b), employee emphasizing (Fleishman, 1957a), and in need for affiliation (McClelland, 1961). Such leaders are expressive and tend to establish social and emotional ties (Bales, 1958a). Dansereau and Yammarino (2002) have used the term individualized leadership to describe relations among leaders and subordinates that reflect an exchange of leader support for subordinates’ feelings of self-worth and the subordinates’ satisfactory performance. The relationship is revealed in the extent the leaders relate similarly or differently to each of their subordinates in the component of individual differences in WABA analysis. Dasborough and Ashkanasy (2003) suggest that leaders can shape affective events by positive uplifts or negative hassles. The negative hassles are more likely to be recalled by subordinates. Usually associated with a positive relations orientation are the leader’s sense of trust in subordinates, less felt need to control them, and more general rather than close supervision of them (McGregor, 1960).

A strong relations orientation is the basis of Reddin’s (1977) “missionary” and “developer” types of leader. Relations-oriented leadership is associated with consideration for the welfare of subordinates (Hemphill, 1950a). For Hersey and Blanchard (1982a, b), it is linked to relationship behavior: maintaining personal relationships, opening channels of communication, and delegating to give subordinates opportunities to use their potential. It is characterized by involved support, friendship, and mutual trust. It is leadership that is likely to be more democratic and employee-oriented rather than autocratic and production-oriented. Misumi (1985, p. 11) saw it as maintenance-oriented leadership behavior “directed toward dispelling excessive tensions that arise in interpersonal relations within a group or organization, promoting the resolution of conflict and strife, giving encouragement and support, providing an opportunity for minority opinions to be expressed, inspiring personal need fulfillment and promoting an acceptance of interdependence among group members.”

Relations-oriented supervision is seen in the communication patterns of supervisors and subordinates. Kirmeyer and Lin (1987) arranged for observers to record an average of 107 face-to-face interactions with the supervisors of 60 randomly chosen police radio dispatchers. Communications with the dispatchers’ supervisors were facilitated if the dispatchers felt they were receiving social support from their superiors. Felt support correlated 33 with the dispatchers’ communications about work to their superior and .48 with communications to their superiors about other matters. It correlated .55 and .26 with observed face-to-face communications from the superiors to the dispatchers about work and nonwork matters.

Quality of Relations. Kottke and Sharafinski (1988) and Hutchison (1997) defined the quality of the relations of employees with their immediate supervisor according to how much the employees felt that their supervisors supported and cared about them. It was correlated with the quality of leader-member exchange (LMX) but could be distinguished from LMX, and from perceived organizational support. However, a Belgian-French study of 293 university alumni respondents found a correlation of .55 between perceived supervisory and perceived organizational support (Stinglhamber & Vandenberghe, 2001). A similar positive correlation was found between enacted supervisory and environmental support by Slack, Etchegary, Jones, et al. (2002). A high quality of relations might be found in self-sacrificing leadership (Choi & Mai-Dalton, 1999).

Organizational Systems. The concern for relations is manifest in different ways with different organizational systems. Such concern and effort are involved in shifting organizations from autocratic systems 1 and 2 to democratic systems 3 and 4 (Likert, 1977b) and in contributing to industrial democracy and participative management.1 The concern for relations is central to humanistic management (Daley, 1986), which is dedicated to promoting the personal significance of work, the autonomy of employees, and fairness in appraisals. In Taiwan, it is seen as a matter of doing favors. It is seen in Britain with Theory P, a deemphasis of traditional management-employee relationships in favor of management’s increased awareness of employees’ needs, increased involvement in the community, and increased use of consultation (Jaap, 1982). It is seen in Japanese management and Theory Z, with its emphasis on long-term employment, unhurried evaluation and promotion processes, wide-ranging career opportunities, and consensual decision making. Theory Z leadership beliefs represent a mix of task direction and relations orientation; generating commitment, loyalty, and involvement in the organization; and treating followers as members of a family (Ouchi, 1981).

Examples: Relations-Oriented Executives. Herb Kelleher was credited by Wall Street analysts as the major reason for Southwest’s continuing profitability after the first two years of business. Southwest often generated larger earnings than any of its competitors, which as of 2005 had registered increasing losses or gone bankrupt. Kelleher was a cofounder of the airline in 1971 and introduced low-priced, frequent point-to-point service instead of the hub-and-spoke service of the major airlines. He used a fleet of one type of aircraft, the Boeing 737, instead of the many types found among his competitors. His cost per available seat mile, employees per aircraft, and employees per passenger were as low as 50% to 75% of his competitors’. But he also ensured employees’ and customers’ satisfaction. In addition to providing employees with 15% of the net profits and matching up to 100% of individual employee contributions to their 401(k) retirement plans, his unusually good labor-management relations and his unusually friendly personality resulted in strong loyalty to the company. Employees were willing to do whatever was needed. (I was surprised, at a stop on my first trip on Southwest, to see the flight attendants cleaning up the aircraft cabin.) Pilots might help out as ticket agents, and ticket agents as baggage carriers. Individualized consideration, kindness, and spirit were nurtured. Recruits were selected for their sense of humor. “Employees are our most important resource” may be a cliché, but it is a major principle at Southwest. Kelleher is like the very funny father of a family and the center of formal and informal festivities (Labich, 1994).

Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield, founders of successful Ben and Jerry’s, were extremely egalitarian and focused on the human side of the enterprise, with a strong sense of social responsibility. Before selling their homemade ice cream company, they ran it like a human service agency. They practiced walk-around management and had fun with their employees and at their annual meetings. They formed a committee to put more joy into employees’ work and decrease stress. They created an organizational culture of charity, goodwill, and respect for the community and kept their top salaries to five times the lowest employee base pay (Levine, 1988; Severance, 1988).

Other CEOs have showed that they cared about their employees in a variety of ways. Jack Stack of Springfield ReManufacturing emphasized teaching employees the financial aspects of the business. Patricia Gallup of PC Connection nurtured her more than 800 employees and interacted directly with them by e-mail. Mary Kay Ash of Mary Kay, Inc. felt she had compassion for her people and viewed them as more important than the bottom line.

Blake and Mouton (1964), Cleveland (1980), and many others have strongly advocated leadership that integrates both task orientation and relations orientation. Leaders have to be strong and decisive, yet sensitive to people (Calloway, 1985). Blake and Mouton (1964) argued that maximum leadership effectiveness occurs only when the leader is highly concerned for both production and for people and integrates the human and task requirements of the job. The exclusively task-oriented manager is seen to treat employees as machines, to the detriment of their commitment, growth, and morale. The exclusively people-oriented manager is viewed as running a “country club,” to the detriment of productivity.2

Leaders exhibit both task and relations orientation. Kaiser and Kaplan (2001) reported that although 46% of managers they sampled in their consulting work were highly task oriented and 19% were highly relations oriented, 6% were versatile in that they displayed just the right amount of both task and relations orientation. The remaining 30% were disengaged (laissez-faire). Further complicating matters are the “switch-hitters.” The autocratic leader is likely to be directive and caught up with getting the work done and the democratic leader is likely to be participative and concerned about maintaining relationships; nevertheless, some benevolent autocrats, who pursue a patronizing leadership style, are still likely to be concerned about their relationships and the needs of their followers. Likewise, highly task-oriented democratic leaders may encourage participation in decision making for the sake of reaching high-quality decisions. Presumably, they would be characterized as R. Likert’s (1977b) System 4 leaders.

Given the increased efforts required to keep up with rapid technological, societal, and market changes, Mintzberg and James (1985) suggested that leaders needed to have an “umbrella” strategy, concerned with getting new ideas accepted and implemented. Morgan (1986) proposed that it was important to focus on challenging constraints. Ekvall (1988) in Sweden and Lindell (1989) in Finland revealed an orientation toward change that they found factorially independent of task and relations orientation (Ekvall & Arvonen, 1989). The change-oriented leader was interested in innovation, creativity, new ways to accomplish old tasks, and new ways to relate to others. The change-oriented leader engaged in Argyris’s (1982) double-loop learning and attention to feedback. In a Swedish factor study of 502 respondents in four manufacturing and five service firms, Lindell and Rosenqvist (un-dated) were able to confirm a three-factor model for 502 respondents to a 36-item questionnaire about their superiors’ behavior and orientation to task, relations, and change. In a sample of 711 mainly middle managers attending management training centers in Sweden, Finland, and the United States who each described their boss, Ekvall and Arvonen (1991) extracted three ortho-gonal factors: change-centered, employee-centered, and production-centered. (Nationality was inconsequential.) The change-centered boss was rated as a promoter of change and growth (pushes for growth; initiates new projects), had a creative attitude (saw possibilities rather than problems, offered ideas, encouraged thinking about new and creative ways and tried them), was a risk taker and was particularly willing to take risks in decisions, made quick decisions when necessary, and was visionary—engendering thoughts and plans about the future.

Relationship of Change Orientation to Concern for Task and Relation. As noted earlier, leaders may emphasize both task and relationships or neither. Observers can accurately discriminate among the ratings for emerging task and socioemotional leadership earned by interacting members of experimental task groups (Stein, Geis, & Damarin, 1973). Hermigar and Taylor (1980) found that the assessed receptivity to change of 80 middle-management administrators of public schools was high if the administrators were either highly concerned for people or highly concerned for productivity. But a lack of concern for either was connected with a lack of openness to change. Experience in leading change affected orientation. Tullett (1995) noted that 133 managers in charge of change projects in Britain were more likely to be innovative in their score on the Kirton Adaptation-Innovation Inventory than managers in general.

As with the tendencies toward and preferences for direction or participation, task, relations, and change orientation tend to depend on the leader’s personal characteristics as well as situational contingencies. These contingencies include the characteristics of the follower, the organization, the task, the goals, and the constraints.

Along with Bales (1958a) and Etzioni (1965), Downton (1973) surmised that instrumental (task-oriented) and expressive (relations-oriented) modes of leadership are assumed by individuals with different temperaments. Instrumental leaders are seen to be more aggressive, more able to tolerate hostility, and more anxious to be respected. Expressive leaders are more accommodating, less able to tolerate hostility, and more anxious to be loved. A variety of surveys and experiments demonstrated this linkage of personality to leadership orientation. For instance, Klebanoff (1976) used observers’ and peers’ rankings of the task-or relations-oriented behavior displayed by 160 participants in 40 small groups working on various tasks. Task-oriented leaders were more likely to have been firstborn children; they felt more personal autonomy and tended to be more actively involved. Menon (2003) found that among 370 managers, those who were more task-focused, goal-oriented, and persistent despite difficulties or distractions were more satisfied with their jobs. Task-focused students were more conscientious and emotionally stable and less hesitant and preoccupied. Konovsky (1986) analyzed the extent to which supervisors of 484 hospital subordinates were seen by their subordinates as providing emotional support and as helping to solve the subordinates’ problems. Supervisors offering such support and assistance also scored higher in personal competence, sociability, emotionality, and altruism.

Helmich and Erzen (1975) surveyed 108 corporation presidents and found that task-oriented leaders lacked fulfillment as presidents. The needs of relations-oriented presidents were better met by their assignment. According to a study of 194 employees in a human service organization, persistence at tasks was greater if the employees perceived themselves to be self-efficacious (Seltzer & Miller, 1990). Bolino, Turnley, and Bloodgood (2002) argued that employees’ favorable attitudes toward organizational citizenship provided organizations with social capital that contributed to better relationships and better performance.

The Orientation Inventory (ORI). Preferences of highly task-oriented examinees on the ORI (Bass, 1962c) included to be wise; to have the feeling of a job well done; to have bright, interesting friends; and to be a leader who gets things done. For interaction-oriented (relations-oriented) examinees, preferences included to have fun with friends, to have helpful friends, to work cooperatively, to make more friends, and to be a leader who was easy to talk to. According to scores on various personality inventories, personal factors significantly correlated with task orientation, as assessed by the ORI, included being more highly self-sufficient, resourceful, controlled in willpower, aloof, not sociable, sober-serious, tough-realistic, and aggressive-competitive (Bass & Dunteman, 1963). Task-oriented leaders were more likely to show more restraint, ascendance, masculinity, objectivity, thoughtfulness, endurance, need for achievement, and heterosexuality (Bass, 1967b).

Task orientation as assessed by the ORI was higher among men than among women and among those with greater maturity, education, status, and technical training. Task-oriented students were more likely to volunteer and to persist at tasks voluntarily until the tasks were completed (Frye & Spruill, 1965). They were self-reinforcers (Marston, 1964) and more likely to be seen as helpful to others in sensitivity training groups (Bass & Dunteman, 1963). In a Polish study, task orientation on the ORI was found to correlate positively as high as .41 with intelligence, as measured by a Polish version of the Army General Classification Test. Interaction (relations) orientation correlated negatively as low as –.32 with tested intelligence (Dobruszek, 1967). Relations orientation was higher among examinees who, according to various personality inventories, were warm, sociable, in need of affiliation, and dependent on the group (Bass & Dunteman, 1963). Relations orientation was also correlated with wanting to be controlled by others, to be close to others, to receive affection from others, to include others, and to be included with others (Bass, 1967b).

Immutable Conditions? These personal factors, seldom mentioned in the prescriptive literature of the past two decades, call attention to Fiedler’s (1967a) argument that one often needs to find or change the situations to fit the leader’s personality. These personal factors make managers and administrators skeptical about the possibilities of training and developing leaders to be both relations and task oriented and about those who say they already are. Nevertheless, the correlations of task and relations orientation with personality and intelligence are modest. Much can be changed in leadership orientation and behavior through learning, role modeling, and experience, reinforced by socialization processes and organizational culture.3

Leaders will be more concerned about the task when their superiors want them to remain focused on it. Managers who are under the gun to produce immediate results are more likely to be task oriented and less likely to devote time and energy to their relationships. Brady and Helmich (1982) found, in a survey of chief executive officers (CEOs) and their boards of directors, that the CEOs were more task oriented than relations oriented if their boards were made up of outsiders. The reverse was true if the boards were composed of insiders. Relations-oriented leaders are likely to emerge when leaders are more attentive to pleasing their followers than their superiors and, by definition, when they are more concerned about the needs of their followers.

In utilitarian hierarchies, organizational level makes a difference in orientation. For 6,434 subordinates in 13 countries describing their superiors, change orientation was most prevalent at the top and production orienta-tion was most common at the bottom; relations orientation was about the same at both echelons (Arvonen, 1992). Nevertheless, senior managers seriously underestimate how much they are distrusted by lower-level employees (Howard & Wellins, 1994). Relations orientation is to be expected in communal organizations, such as the Israeli kibbutzim, whose espoused beliefs emphasize providing for members according to their needs. Socioeconomic differences between communities of workers are also likely to be of consequence. Thus Blood and Hulin (1967) reported that workers in communities in which one would expect adherence to middle-class norms (for example, small suburban communities) tended to favor a human relations style of supervision. Strong organizational policies supporting either a relations or a task orientation (or both) particularly coincide with a top management that provides role models for lower management and engenders task, relations, or change orientations among the individual managers and supervisors. Also, the leaders’ orientation is likely to be affected by those below them.

Subordinates and Their Performance. Earlier chapters noted that poor performance by subordinates appears to cause much of the observed punitiveness of leaders. But good performance by subordinates appears to increase leaders’ tendency to be relations oriented. In a study of routine clerical workers and their supervisors at a life insurance company, Katz, Maccoby, and Morse (1950) found that supervisors of high-producing sections were significantly more likely to be employee oriented than production-oriented. Barrow (1975) showed that increasing the performance of subordinates in a laboratory setting resulted in the leader becoming significantly more supportive. Decreasing the subordinates’ performance caused the leader to become more task-oriented. This finding is consistent with Bass, Binder, and Breed’s (1967) findings about the performance of a simulated organization (discussed below).

Farris and Lim (1969) showed that if the performance of groups was good in the past, the groups’ leaders subsequently tended to be more relations-oriented. The leaders were more sensitive to the needs and feelings of the members and had more trust and confidence in the members. These leaders allowed members more freedom and autonomy in their work. Members were encouraged to speak out and were listened to with respect. The leaders gave recognition for good work, communicated clearly, stressed pride in the group, and emphasized teamwork. The leaders of high-performing groups were also more task oriented than were the leaders of low-performing groups, in that they maintained high performance standards without being punitive. They were less likely than the leaders of low-performing groups to be critical of their groups’ performance and less likely to exert unreasonable pressure for better performance.

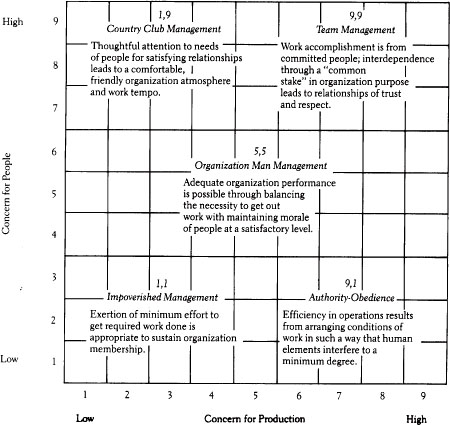

Jones, James, and Bruni (1975) could not separate cause and effect in a study of 112 engineering employees. But the results suggest the followers’ influence on their leader’s orientation and behavior, although the reverse possibility is also tenable.4 Jones, James, and Bruni obtained correlations of from .41 to .55 between employees’ confidence and trust in their supervisors and the extent to which their supervisors were seen as high in support, emphasis on goals, facilitation of work, and facilitation of interaction. As was noted in Chapter 7, Sanford (1951) found, in a survey of Philadelphia residents, that egalitarians wanted leaders who were warm and generally supportive, but authoritarians preferred leaders who would serve their special interests. Indirectly, one may infer that more relations-oriented leadership would be demanded by highly self-oriented followers, by followers with personal problems, by followers in need of nurturance, and by followers seeking affection. As will be detailed later, the “psychological and job maturity” of subordinates dominates the Hersey-Blanchard (1977, 1981) prescriptions for determining whether leaders should be relations or task oriented or both in their behavior toward subordinates.

Prior Effectiveness of the Organization. Commonly observed as well as deplored (see, for instance, R. Likert, 1977b) is the extent to which human relations concerns are abandoned when an enterprise’s profits are seriously eroded. In such situations, akin to a stress response, task orientation is increased at the expense of relations orientation. Bass, Binder, and Breed (1967) demonstrated this phenomenon in a simulated budgeting exercise. The concern of decision makers for the satisfaction and well-being of employees and their willingness to accept more employee-centered solutions to problems in the areas of safety, labor relations, and management development were strongly influenced by whether the company had just finished a profitable year. In this exercise, MBA students were given one of three firms’ year-end profit-and-loss statements. One firm showed a net loss of $86,000; the second firm’s statement showed that moderate profits had been earned; the third firm reported large profits. Three-quarters of the students in the profitable circumstances recommended buying safety equipment. Only half of the students in the moderately profitable enterprise and only 25% of those in the firm that lost money were willing to spend the required funds to settle a strike quickly. The goals emphasized in the most profitable situation were the welfare, goodwill, and satisfactory operations of employees. The goals stressed in the firm that had experienced a loss were meeting competition and raising profits.

Three kinds of evidence are available: (1) the extent to which relations-oriented and task-oriented leaders are seen to be more or less meritorious by others; (2) the differential impact of these orientations on the satisfaction of subordinates; and (3) the differential effects of these orientations on the performance of groups. Care must be maintained about the validity of the evidence. Consistently, one sees managers who describe themselves as both more task oriented and more relations oriented than their subordinates perceive them to be (see, for example, Rees & O’Karma, 1980).

Reports on correlations of evaluations as a leader and relations or task orientation have generally found both orientations to be of positive importance. Followers’ values affected the extent to which they favored leaders of one kind or another. Ehrhart and Klein (2001) reported that employees who were more interested in extrinsic rewards for performance favored more relations-oriented supervisors whereas employees who preferred more structure and security in their work favored more task-oriented supervisors. Mathieu (1990) found that among 298 ROTC cadets, those high in need for achievement preferred instrumental (task-oriented) leadership; those low in need for achievement preferred relations-oriented leadership.

Relations Orientation. Shartle (1934) used interviews and questionnaires in a comparative study of supervisors who were rated as either effective or ineffective. Effective supervisors did not differ from their ineffective peers in technical skills, but they were found to excel in their ability to interact effectively and in their interest in people. Similarly, Katzell, Barrett, Vann, and Hogan (1968) found that executives whose roles emphasized administrative, rather than technical, performance received higher performance ratings from their superiors.

Mann and Dent (1954b) studied supervisors who were rated for promotability by higher-level managers. Highly promotable supervisors were described by their employees as being good at handling people; approachable; willing to go to bat for employees; letting the employees know where they stand; pulling for both the company and the workers, rather than just for one or the other; and using general, rather than close, supervision. In turn, the highly promotable supervisors saw their own superiors as being good at handling people, letting the supervisors know where they stood, and permitting the supervisors the freedom to make decisions.

H. H. Meyer (1951) observed that effective supervisors regarded others as individuals with motives, feelings, and goals of their own and did not avoid interactional stress. Similarly, Kay and Meyer (1962), using both questionnaire and observational methods, found that higher-rated foremen were less production oriented and gave general, rather than close, supervision. Likewise, Walker, Guest, and Turner (1956) observed that effective supervisors established personal relationships with employees, stuck up for them, and absorbed pressure from higher levels of authority. A. N. Turner (1954) reported that workers regarded supervisors as good if the supervisors did not pressure their subordinates unnecessarily; were fair, friendly, and understanding; and did not tell subordinates to quit if they did not like the conditions.

Among the 17 Americans on the 1963 Mount Everest expedition, all of whom were highly task oriented, those who were most interaction oriented and highest on FIRO-B (Fundamental Interpersonal Relations Orientation-Behavior) expressed inclusion were rated highest in leadership. Lester (1965, p. 45) noted,

The results pointed to the importance … of being emotionally responsive, affectionate and warm, inviting in manner, or placing primary value on the emotional give-and-take in face-to-face relations. The men reacted negatively to emotional constriction, to too much emphasis on method, efficiency, productivity, and the imposition of high impersonal standards.

However, when interaction-orientation scores are high at the expense of task-orientation scores—as when ipsative scoring5 is used—task orientation, rather than interaction or relations orientation, is likely to correlate with merit as a leader.

Task Orientation. Rubenowitz (1962) reported that job-oriented supervisors were regarded by higher management as more effective than person-oriented supervisors. Shortly afterward, Kelly (1964) found that the technical features of executives’ behavior outweighed the effects of personal style.

According to Dunteman (1966), task orientation, as measured by the ORI, correlated with promotability ratings based on three days of assessment of 96 supervisors (but correlations were negative among the younger, temporary supervisors and the journeymen who were so assessed). For both 66 first-level and 27 second-level supervisors, task orientation significantly contributed to their high on-the-job performance ratings by their supervisors (Dunteman & Bass, 1963). Rutherford (1984) reviewed studies of the success of elementary school principals. In attempts to implement new programs or to improve the schools, the successful principals appeared highly task-oriented. They made strong instructional efforts; set clear, high expectations for teachers and students; and monitored performance. They actively intervened when intervention was needed. The successful principals also paid attention to relationships, remaining in close contact with the teachers.

Many other studies, enumerated in Chapter 27, have found that leaders who are concerned about the task in situations in which such a concern is relevant are likely to be evaluated highly by others. Furthermore, the plethora of studies of the need for achievement6 provide additional evidence of the positive association of task orientation and success as a leader.

Supervisors’ attention to relationships was seen early in several investigations focused on the impact on subordinates’ satisfaction of psychological and social closeness or distance, a component of relations orientation. Julian (1964) found that job satisfaction was higher when there was psychological closeness between the leader and the led. However, Blau and Scott (1962) and E. R. Shaw (1965) reported that the cohesiveness of the group was strengthened by the social distance between the leader and the followers, and Sample and Wilson (1965) found cohesiveness to be unrelated to social distance. Still, the majority of reports from both field studies and laboratory experiments have indicated that subordinates’ satisfaction with their leaders was linked to the leaders’ relations-oriented attitudes and behavior. Particularly important for follower satisfaction, performance, and willingness to follow the leader is the extent to which the leader evinces support for the followers’ feelings of self-worth (Dansereau, Yammarino, Markham, et al., 1995). A supportive change-oriented supervisory attitude also lies behind subordinates’ efforts to innovate (Delbecq & Mills, 1985) and to be creative (Langley & Jones, 1988).

Field Studies. Hoppock’s (1935) analysis of the early literature on job satisfaction indicated that workers tended to feel more satisfied when supervisors understood their problems and helped them as needed. In a survey of more than 10,000 managerial, supervisory, and hourly personnel, Ronan (1970) obtained similar results, as did Roberts, Blankenship, and Miles (1968). Stagner, Flebbe, and Wood (1952) found that railroad workers were better satisfied when their supervisors were good at handling grievances and communicating with employees. Likewise, Bose (1955) observed that workers under employee-centered supervisors had more pride in their groups than those under work-centered supervisors. Mann and Hoffman (1960) found that in two plants—one automated, the other not—employees were more satisfied with supervisors who were considerate of their feelings, recognized good work, were reasonable in their expectations, and stood up for the subordinates.

Stampolis (1958) showed that the more employees rated their supervisor as fair, able to handle people, giving credit, ready to discuss problems, and keeping employees informed, the less the employees expressed a desire for their company to be unionized. Bass and Mitchell (1976) reported similar results for professional and scientific workers. The United Auto Workers had difficulty organizing the highly relations-oriented Japanese-owned automobile plants in the United States (Gladstone, 1989).

Wager (1965) found that a supportive style of leadership assisted the supervisor in fulfilling and satisfying the employees’ role expectations. In an aircraft factory, where team leaders devoted much of their time to facilitating the work of the teams and attending to the members’ personal problems, indicators of dissatisfaction, such as absenteeism and turnover, were lower (Mayo & Lombard, 1944).

York and Hastings (1985–1986) asked 172 employees working in North Carolina social services to complete the Survey of Organizations (D. G. Bowers, 1976). At all levels of the assessed maturity of workers, facilitative and supportive performance of supervisors was associated with the subordinates’ satisfaction and motivation to work. A review of nursing studies by Maloney (1979) concluded that people-oriented leaders generally were more satisfying to their employees. In addition, employees’ grievances and turnover were lower when the leaders were seen as relations oriented.

When the socioemotional and task-oriented leadership of residence hall leaders were measured separately by MacDonald (1969), both were linked to the satisfaction of students. However, the effects of task orientation on subordinates’ satisfaction have usually been found to be somewhat less consistent. Task-relevant behavioral measures, which contain elements of the leaders’ punitiveness, will generate dissatisfaction, grievances, and turnover (Schriesheim & Kerr, 1974). In a survey of several thousand employees, R. Likert (1955) found that job satisfaction decreased as the supervisors’ pressure for production increased. However, it is not uncommon to find positive correlations for both the task-and relations-oriented behavior of supervisors and the satisfaction of their subordinates. Generally, for nurse supervisors, for example, a strong task orientation that is not coupled with a high relations orientation results in less satisfied subordinates (Maloney, 1979). Gruenfeld and Kassum (1973) showed that nurses were satisfied with highly task-oriented supervisors, but only if the supervisors’ people orientation was high as well. The strong task orientation of supervisors was dissatisfying when coupled with a medium or low orientation to people. But Arvonen (1995) found, in Swedish forest-product manufacturing, that supervisor task orientation—as revealed in their structuring, clarification, and ordering of work—did not produce dissatisfaction among blue-collar employees, as it did among white-collar employees and managers.

In a very large undertaking of over two decades, Misumi (1985) conducted studies of over 150,000 Japanese employees working in banks, post offices, coal mines, shipyards, transportation, utilities, and manufacturing, under supervisors with different performance (P) and maintenance (M) orientations. The supervisors were classified as P-type (above the median in performance alone), M-type (above the median in maintenance alone), neither type (pm), or both types (PM). The subordinates of a PM supervisor had a more favorable attitude toward their supervisor than did the subordinates of an M-type or P-type supervisor. The least satisfying supervisors were those who were pm types. In a bank that had branches in Okinawa, Misumi and Mannari (1982) surveyed an average of 1,325 subordinates who described their 303 superiors’ leadership. The P and M leadership orientations of the supervisors, as well as the subordinates’ morale (interest in work and satisfaction with supervision), were collected five times at 15-month intervals. The supervisors were changed in 287 groups but not in 159 groups. There was less change in morale from interval to interval if the supervisor did not change. However, the morale of the subordinates rose if the P and M leadership orientation of the supervisor’s successor was higher than that of the former supervisor. The previous morale of the subordinates had less of an effect on the incoming supervisor’s leadership than vice versa.

Along with relations and task orientation (r = –.33), change orientation also appears to contribute to satisfaction. Arvonen (1995) collected survey data from 781 employees in two production plants of a Swedish forest-products firm. Dissatisfaction and lack of well-being were less if supervisors were structure-oriented (r = –.27), relations-oriented (r = –.33), and change-oriented (r = –.25).

Laboratory Experiments. Experiments may provide additional convincing evidence of the relationship between a leader’s relations orientation and subordinates’ satisfaction. As with the field studies, most experimental studies have concluded that satisfaction of subordinates was positively associated with the leader’s relations-oriented behavior. Wischmeier (1955) found that group-centered, rather than task-centered, discussions resulted in a warm, friendly group atmosphere. T. Gordon (1955) found that group-centered discussion was associated with members’ sense of belonging, respect for others, ability to listen to and understand others, and loss of self-defensiveness. Similarly, Thelen and Whitehall (1949) and Schwartz and Cekoski (1960) reported that follower-oriented leadership enhanced satisfaction. Maier and Danielson (1956) reported that an employee-oriented solution to a disciplinary problem produced greater satisfaction in groups of problem solvers than a solution bound by legalistic restrictions.

Heyns (1948) coached one set of leaders to play a positive, supportive role that emphasized agreement, mutual liking, and cooperation. Leaders in another set were coached to play a negative role in which they overtly displayed a misunderstanding of the members and made no effort to develop their groups’ cohesiveness. Although the two styles produced no significant difference in the quality of the groups’ decision or the members’ satisfaction, the groups with positive leaders exhibited evidence of greater cohesiveness. W. M. Fox (1954) used scenarios to coach leaders in a positive relations approach or a “biased, diplomatic, persuasive” role. Groups with positively supportive leaders exhibited higher degrees of cohesiveness and members’ satisfaction but were slower in solving problems. With a different group of participants, W. M. Fox (1957) also found that supportive leadership was associated with the members’ satisfaction and the groups’ cohesiveness.

Zaleznik (1997) lamented the extent that attention to the task has suffered from too much concern for relationships. He attributed this to the increased complexity of the organization, in which managers and executives have to play many roles; and to the success of the human relations movement. This movement emphasized the need for cooperation and workplace harmony and had “an unhealthy preoccupation with process at the expense of productivity” (p. 7). The substantive hard work of business was displaced by psychopolitics; by “smoothing over conflict, greasing the wheels of human interaction” (p. 7); and by driving out the necessary “real” work of cutting costs and creating products. However, generally, we shall see that effectiveness is greatest when leaders attend to both task and relationships.

It may be difficult to separate the impact of the leader’s orientation on the members’ satisfaction from its impact on the members’ and the group’s effectiveness. For example, Medalia and Miller (1955) observed that human relations leadership and employees’ satisfaction interact to influence the group’s effectiveness. And although a leader’s relations orientation and task orientation are both generally found to be positively associated with the group’s productivity, the group’s attainment of goals, and followers’ performance, there are exceptions. Some situations may call for more relations-oriented leadership and others for more task-oriented leadership. However, it may be that in a vast majority of circumstances, strong doses of both types of leadership orientation are optimal.

When positive associations are found, it is usually inferred that the relations orientation or task orientation of the leader resulted in the improved performance of subordinates. But the reverse may be equally true. Few of the findings have been causal. That is, the previous performance of subordinates is as likely to affect the orientation of the leader as the leader’s orientation is likely to influence the subsequent performance of the subordinates (Bass, 1965c). Farris and Lim (1969), as was previously mentioned, showed that the past good or poor performance of groups determined, to a considerable degree, the task and relations orientation of their leaders.

Relations-Oriented Leadership and Follower Performance. Pandey (1976) reported that groups with relations-oriented leaders generated more ideas than groups with task-oriented leaders. Katz, Maccoby, and Morse (1950) and Roberts, Miles, and Blankenship (1968) found that the performance of groups was higher under an employee-oriented style than under a more disinterested style of supervision. Philipsen (1965a, 1965b) also found that human relations leadership correlated positively with group effectiveness. But in a study of skilled tradesmen, Wison, Beem, and Comrey (1953) established that supervisors of both high-and low-performing shops were described as more helpful, sympathetic, consistent, and self-reliant than were those in medium-performing shops. Slack, Etchegaray, Jones, et al. (2002) reported that supervisory-espoused support was linked to enacted support. Enacted supervisory support was linked to employee performance because the employees perceived a supportive environment. Bliese, Bienvenu, Castro, et al. (2002) found that a supportive leadership climate played an important role in determining whether the stress of the work overload of soldiers on assignment in Kosovo could be buffered by job control.

Abdel-Halim (1982) showed how much of subordinates’ role conflict and role ambiguity—which affected their intrinsic satisfaction with, involvement in, and anxiety about their jobs—were moderated by the support they received from their supervisor. In the report by Konovsky (1986), supervisors who were judged by their 484 subordinates as helpful and emotionally supportive contributed to the subordinates’ commitment to their hospital organization and to the supervisors’ judged interpersonal effectiveness. Riegel (1955) found that employees’ interest in their company’s success increased when their supervisor was seen to help them with their difficulties, to give necessary training and explanations, and to “take an interest in us and our ideas.”

Indik, Georgopoulos, and Seashore (1961) studied the employees of a transportation company. Their results indicated that high levels of group performance were associated with satisfaction with the supervisors’ supportiveness, open communication, mutual understanding, and workers’ autonomy on the job. As documented in Chapter 17, R. Likert (1967a, 1967, 1977b) concluded, from many surveys, that supportive attitudes toward employees, combined with the group’s loyalty toward management, were associated with increased productivity and a desire for responsibility by the employees. With the introduction of a human relations approach to management, as well as high performance goals, long-term gains in productivity were achieved. Similarly, Daley (1986) surveyed 340 employees of Iowa public agencies and obtained uniformly positive associations between their perceptions of relations-oriented, humanistic management practices and their evaluations of the effectiveness and responsiveness of their organizations to the public. Stinglhamber and Vandenberghe (2001) obtained correlations of .44 and .38 between perceived supervisory supportive relations and employee satisfaction with job conditions.

Supportive leadership increases the likelihood that organizations can police and correct themselves. Near and Miceli (1986) found that the felt support from their leaders was the most important factor in protecting employees from retaliation for calling attention to observed wrongdoing. Conversely, in a random sample of 8,600 federal employees the perceived likelihood of retaliation for whistle-blowing correlated with the lack of support from their supervisors and higher management. This perception was realistic. Honest whistle-blowers were actually more likely to be punished than their corrupt senior managers in the Department of Housing and Urban Development under Samuel Pierce from 1981 to 1988.

Ramus and Steger (2000) surveyed 353 employees in 12 countries in large environmentally-proactive companies with headquarters in Europe. The survey disclosed that employees who perceived management support were willing to promote self-described environmental initiatives. Without such perceived support, they were unlikely to do so.

Deluga (1988) noted that faculty members in a school of higher education, when negotiating a second time, reduced their bargaining and use of authority as influence strategies if the leadership was perceived as relations-centered.

Correlations of Task-Oriented Leadership with Performance. In contrast to the above in Deluga’s study of influence strategies, faculty member bargaining, assertiveness, coalition formation, and reference to higher authority emerged if the leadership was perceived as task centered. R. Likert (1955) reported that a survey of several thousand workers indicated a tendency for productivity to be higher in the presence of higher pressure by supervisors for production. Similarly, Litwin (1968) noted that experimental groups whose leaders had a strong need for achievement were much more productive than groups whose leaders had a great need for affiliation or power. Dunteman and Bass (1963) studied foremen who had an interaction orientation or a task orientation. Groups who worked under task-oriented leaders were more productive than those under interaction-oriented leaders. Mann, Indik, and Vroom (1963) showed that the productivity of workers was associated with the supervisor’s task orientation. R. Cooper (1966) also reported that first-level supervisors whose bosses judged them to be higher in “task relevance” tended to have more productive and more task-motivated subordinates.

For 14 U.S. Navy airplane-maintenance groups, R. Likert (1977a) reported a strong association between the extent to which supervisors facilitated the work by helping with advanced scheduling and offering new ideas to solve problems in the job, and the extent to which airplanes serviced by the groups were not involved in accidents or disasters because of operational failures.

Effects of Change/Development Orientation. Lin-dell and Rosenqvist (undated) reported results for change and development styles for 502 Swedish cases from four manufacturing and five service companies. Management change correlated .67 with managerial competence, .73 with comfort with the manager, and .17 with comfort with the employees’ own tasks. The comparable correlations for managerial development were .67, .53, and .24. For task orientation, the correlations were .59, .52, and .26. LaPolice and Costanza (undated) found that a three-factor model, which included change-related leadership along with task and relations orientation, was the best predictor of the behavior of 16,795 employees from 16 government agencies Analyses were based on the Office of Personnel Management’s Organizational Assessment Survey.

Effects of a Combined Task and Relations Orientation. There is considerable theoretical and empirical support for the idea that regardless of circumstances, the effectiveness of leadership is greatest when the leaders are both task oriented and relations oriented in attitudes and behavior. Thus Patchen (1962) reported that the leader who maintained high performance norms, encouraged efficiency, and attempted to obtain rewards for followers was likely to have a high-performing group. However, the maintenance of high performance standards alone and attempting to obtain rewards for followers alone each had a negative effect on productivity. These two patterns of behavior had to be combined to have a positive impact on productivity.

Numerous other studies and lines of investigation have supported the utility of a combined high task-and relations-oriented approach to leadership. Tjosvold (1984b) demonstrated, in an experiment with 56 college students, that the students were most productive in completing a subsequent task if they had experienced beforehand a leader who nonverbally conveyed warmth and who was directive about what was to be done. The experience of the warm leader, along with the absence of direction, was satisfying but was least conducive to subsequent productivity. Similarly, Klimoski and Hayes (1980) found that the effort, performance, and satisfaction of 241 assistants in the production department of a large information-processing firm were enhanced if the supervising editors were task centered in being explicit in their expectations and consistent in their demands, as well as supportive of their employees. Daniel (1985) found that subordinates perceived that they were working in a more productive organization if their managers were concerned both about tasks and about people. Hall and Donnell (1979) conducted a survey study of 2,024 subordinates who described their managers’ attention to the demands of the task and concern for the quality of manager-subordinate relationships. The managers who were high in both earned high “career achievement quotients.” (The quotient reflected the speed with which they had climbed their organizational ladder.) They were also the most collaborative in their leadership style. These results were consistent with findings by Blake and Mouton (1964) and J. Hall (1976) for large samples. The moderately successful managers had a low relations orientation but a high task orientation, while those whose career success was lowest were low in both task and relations orientation.

Erez and Kanfer (1983) argued that the relations orientation implied in allowing subjects to participate in goal setting enhanced the task-oriented impetus for more goal setting than did assigning goals to subjects without permitting them to participate in setting the goals. Erez, Earley, and Hulin (1985) obtained experimental evidence to show that such participation increased acceptance of the goals and hence increased productivity. However, Erez (1986) found that the organizational culture from which the participants were drawn affected the need for such participation: subjects from the Israeli private sector did better with assigned goals; subjects from the kibbutz sector did better with group participation in setting goals.

As described earlier in discussing the utility of participation, Locke, Latham, and Erez’s (1987) critical experiment tried to understand why, in their respective investigative efforts and using the same standardized experimental conditions, assigning goals to subjects generated more productivity in the United States (Latham & Steele, 1983), while allowing the subjects to participate in goal setting generated more productivity in Israel (Erez & Arad, 1986). The one difference that turned out to account for the highly significant difference in productivity was that the Israeli experimenter was curt and unsupportive in giving instructions, but the U.S. experimenter was friendly and supportive. The friendly, supportive experimenter’s instructions facilitated the subjects’ acceptance of the assigned goal without their having participated in setting it.

Misumi (1985), and Misumi and Peterson (1985), consistently found, in the previously mentioned studies of 150,000 Japanese employees in business and industry, greater productivity by employees under PM supervision than under pm supervision—that is, under managers who were above rather than below the median in both performance orientation and maintenance orientation. In one of these studies, P and M were systematically manipulated for coordinated first-level and second-level supervision in an experiment with 15 postal trainees working in trios. The PM-type first-level supervision generated more productivity than did either P or M alone. Second-level supervision, present only in the form of written instructions to the subjects from the second level, had the same effects, although with less statistical significance. For 215 of 500 groups of coal miners, when the second-level supervisor was actually present, the PM pattern at both the first and second level of supervision was most typical for the high-producing groups. For 186 working groups of about 10 employees each, involving a total of 2,257 workers in a Mitsubishi shipyard, evaluations of group meetings were most positive under PM-type leaders (evaluation mean = 17.5), followed by M-type (mean = 16.4), P-type (mean = 15.3), and pm-type (mean = 14.5) leaders.

The rated performance of 92 squads in a bearing manufacturing firm was most often high under PM leadership and least often high under pm leadership. The results for ratings above the median for P alone or above the median for M alone were in between. The same pattern emerged in a tire-manufacturing firm, where the success or failure rate of 889 project managers was strongly associated with their style of leadership: PM, P, M, or pm. The success rate was highest (52%) and the failure rate was lowest (5%) with the combined PM style.

Peterson (1988) concluded that introducing PM theory and practice in China and the West may need modification. For instance, more attention may need to be paid to merging self-interests with working hard. Peterson, Smith, and Tayeb (1993), in a British and in a U.S. plant, found results consistent for M but unlike those in Japan. “Pressuring” leadership was negatively related to interpersonal cooperation. This was confirmed when Royal Australian Air Force service personnel and blue-and white-collar employees were questioned about how much they liked or disliked supervisory pressure statements such as, “Hurry up, you have to work harder” and “There are a number of tasks I want you to complete today” (p. 263). As will be noted in Chapter 20, such pressuring for production had to be eliminated from the “initiation of structure” factor assessment in the Leadership Behavior Questionnaire to improve its prediction of subordinates’ satisfaction and performance (Fleishman, 1973). In order to be palatable to Australian subordinates, such statements had to be preceded by socioemotional supportive statements such as, “You have been doing a good job” and “I appreciate the extra effort you have been making” (p. 263).

Negative Evidence. A number of additional exceptions to the positive effects of task or relations orientation on productivity have been reported, particularly in short-range analyses. Andrews and Farris (1967) found no evidence that innovation was higher when supervisors of scientific personnel were high in both task and human relations functions. Human relations skills had little moderating effect on the generally positive relationships between the leader’s carrying out task functions and innovation. The most innovation occurred under supervisors who were neither high nor low in their attention to human relations, regardless of the task functions that were completed.

Lundquist’s (1957) results indicated that regardless of whether supervisors were worker-oriented, the sheer frequency of their interaction with workers increased their effectiveness. Weitz and Nuckols (1953) found that supervisors’ scores on a test measuring human relations orientation were not related to the productivity of the group or to the turnover of personnel. MacKinney, Kavanagh, Wolins, and Rapparlie (1970) found that both production-oriented and employee-oriented management were unrelated to the satisfaction of employees. Carp, Vitola, and McLanathan (1963) showed that supervisors of effective postal teams maintained their social distance from subordinates, an attitude that reduced the surfacing of emotional problems. Fernandez and Vecchio (1997) found little descriptive utility in the Hersey-Blanchard predictions of the performance of university employees. However, they did find that supervisory monitoring had a positive impact on lower-level employee performance, and supervisory consideration had a positive impact on higher-level employee performance.

In a study of simulated management groups, Kaczka and Kirk (1967) established that the profitability of teams was associated with relations-oriented leadership. But this type of leadership also resulted in less pressure to accomplish tasks and less cohesiveness in the groups. C. A. Dawson (1969), studying the achievement of schoolchildren, observed that the children performed equally well under “cold” or “warm” leadership.

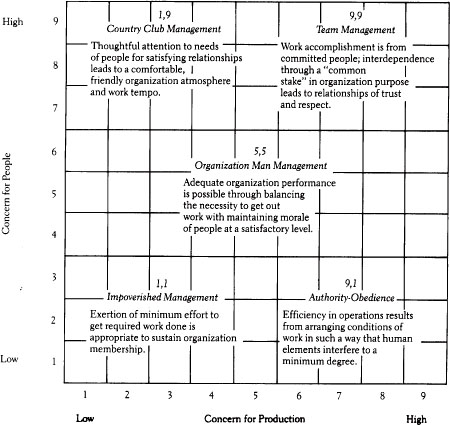

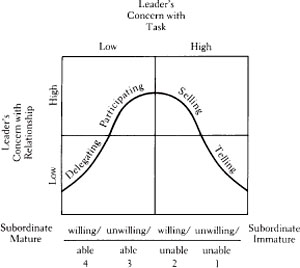

Among the models of task and relations orientation of the past 40 years with the power to survive into the twenty-first century are Blake and Mouton’s (1964) Grid, Hersey and Blanchard’s (1969 a, b) Situational Leadership, and Fiedler’s (1964a, 1967) Contingency Model. Fiedler and Hersey and Blanchard emphasized that what the leader should do to be effective depended on diverse circumstances. But Blake and Mouton (1964) prescribed the integration of task and relations orientations as the one best way to achieve effective leadership. Their managerial grid (see Figure 19.1) is based on the concept that managers and leaders vary from 1 to 9 in their concern for people (the vertical axis of the grid) and from 1 to 9 in their concern for production (the horizontal axis). The measurement of these concerns is based on a manager’s endorsement of statements about management assumptions and beliefs. But these concerns are interactive rather than independent. They are manifested in the five styles shown on the grid as published in 1985 (Blake & Mouton, 1985) and “softened” in a later version by Blake and McCanse (1991), with concern for production replaced with concern for results.

The revised grid and its expected effects are shown in Figure 19.1. Further elaboration was provided by Blake and McKee (1993).

9,1: Authority-Compliance Management. Efficiency in operations results from arranging conditions of work so that human elements interfere to a minimum degree. Expected effects: Productive, but quality suffers. Strong conflict, resentment, antiorganizational creativity, and efforts to “beat the system” are high.

1,9: “Country Club” Management. Thoughtful attention to the needs of people for satisfying relationships leads to a comfortable, friendly organizational atmosphere and work tempo. Expected effects: Low productivity, indifferent quality, low conflict, easygoing and pleasant atmosphere.

Figure 19.1 Managerial Grid

SOURCE: Blake and Mouton, Managerial Grid III: The Key to Leadership Excellence. Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing, 1985.

1,1 Impoverished Management. Exertion of minimum effort to get required work done as appropriate to sustain organization membership. Expected effects: Low productivity and quality, poor creativity, low conflict, low involvement.

5,5: Middle-of-the-Road Management. Adequate organizational performance is possible through balancing the necessity to get out work with maintaining morale at a satisfactory level. Expected effects: Acceptable performance based on the status quo, moderate quality, good team players who go along to get along, low creativity.

9,9: Team Management. Work accomplishment from committed people; interdependence through a “common stake” in organization, purpose leads to relationships of trust and respect. Expected effects: High productivity, quality, and creativity stimulated by internalized goals and objectives; commitment to goals, resulting in a high degree of interdependent cooperation; conflict is productive confrontation. 9,9 can take the form of paternalism if the leader fails to integrate the concerns for people and results—that is, if the two are kept in logic-tight compartments. The leader cares as father or mother for dependent subordinates, from whom unconditional loyalty is expected.

Opportunistic leaders use several styles interchangeably, depending on the persons with whom they are dealing Sometimes leaders masquerade as 9,9s when they really are paternalists or opportunists hiding behind facades.

The leader’s dominant style is likely to be backed up by other styles. Thus, for instance, the 1,9 leader may begin a meeting in a casual, friendly way but quickly become a tough, no-nonsense 9,1, which is his or her dominant style (Blake & Mouton, 1985c).

Team leadership (9,9) is prescribed. It is attained by behavioral science principles that involve participation, openness, trust, respect, involvement, commitment, open confrontation to resolve conflicts, consensus, synergistic utilization of the human resources represented by the leader and followers, mutually determined management by objectives, mutual support, and change and development through feedback (Blake & Mouton, 1981a).

According to a study reported by Blake and Mouton (1985c), prior to a seminar on the subject, 68% of the managers saw themselves as 9,9; 10% as 9,1; 19% as 5,5; and 2 to 3% as 1,9 or 1,1. After the seminar, a modal 41% admitted to being 5,5 and another 36% saw themselves as 9,1. Only 16% now believed they were 9,9. Blake and Mouton thought that these changes in results indicated the self-deception that occurs if understanding is impaired and feedback is not provided.

According to Blake and Mouton (1978), a 9,9 orientation has consistently proved to contribute positively to a variety of performance criteria in organizational development studies. In one of these studies, two matched subsidiaries of the same company were involved in a pre-post comparison over 10 years. One subsidiary engaged in an extensive organizational development program that stressed 9,9 management; the other was not involved in any comparable program. The experimental subsidiary increased its profitability by 400% over the matched control.

In a study of 716 managers from a single firm, Blake and Mouton (1964) found (after correcting for age differences) that 9,9-oriented managers were more likely than those with other dominant styles to advance further in their careers. J. Hall (1976) replicated these findings with an independent sample for 731 managers from a variety of companies.

Blake and Mouton (1985b) determined that the 9,9 style of team-management orientation characterized the leadership of the twentieth-century U.S. presidents who had performed with greatness, in contrast to those who had not. This style was inferred from contemporary writings about the presidents’ different ways of decision making, exercising initiatives, analyzing problems, taking advocacy roles, dealing with conflicts between themselves and their subordinates, and using critiques to increase their effectiveness in achieving results with and through subordinates.

Blake and Mouton did not leave much room for exceptions. Nevertheless, in a substantial number of investigations of the impact of task and relations orientation the findings have been mixed or negative. Explanations have been sought in situational contingencies. These situational contingencies need to be examined for their moderating effects on the impact of relations-and task-oriented leadership on the satisfaction and productivity of followers. For instance, Miner (1982a, 1982b) suggested that high-task, high-relations leadership orientation is most likely to be effective when organizations are a mix of systems of hierarchies and groups. The task orientation fits the hierarchies; the relations orientation fits the groups.

One example of a moderated result was the upward influence tactics used by subordinates who were subjected to task-or people-centered leadership in Deluga’s (1987b) study of 48 faculty members at a school of higher education. Deluga found that in the faculty members’ first attempt to influence their superiors, only the superiors’ relations orientation was of consequence. The faculty members said they were less likely to bargain or appeal to a higher authority if their superiors were more people centered. But if their first attempt failed to influence their superiors, the task orientation of the leaders became important in the second attempt. Here, the faculty members said that the more they thought their superior was task-centered, the more likely they would be to try friendliness, bargaining, assertiveness, appeals to a higher authority, and forming coalitions.

Although relations-oriented leadership was expected to generate more satisfaction among subordinates, moderating effects were seen in a number of investigations. In a study of community hospitals, F. C. Mann (1965) observed that the satisfaction of the nurses was related to the human relations skills of their supervisors, but the satisfaction of the nursing supervisors was related to the administrative skills of their superiors. The satisfaction of the hospital technicians was related to their supervisors’ technical and human relations skills. Tannenbaum and Allport (1956) studied two departments of women workers. One department was given more responsibility and authority for work and for decisions about the work, and the second department emphasized top-down line authority. A personality test was administered initially and scored as to the suitability of the workers’ personality to the situation in which they worked. One year later, an attitude test was administered. The results of the test revealed that significantly more suited than unsuited workers in the situation with more authority and responsibility wanted the situation to continue. However, suited and unsuited workers did not differ in their attitudes toward the program if they had not been given authority and responsibility. In another large-scale field study, Seashore (1954) found that supportive leadership with cohesive work groups paid off in higher productivity. However, the same group cohesiveness also resulted in lower productivity when the groups’ supervisors were unsupportive.

A number of investigators saw the followers’ need for achievement as making a difference in the way the followers reacted to particular styles of leadership. W. W. Burke (1965) discovered that followers with a high need to achieve who had socially close leaders rated their situation as more tense than did those with a high need to achieve who were under socially distant leaders. Followers with a low need to achieve who had socially close leaders rated their situation as more tense than did followers with a high need to achieve who had socially distant leaders. Followers with a high need to achieve rated socially close leaders high in authoritarianism; those with a low need to achieve did the same for socially distant leaders. Misumi and Seki (1971) also studied the effects of leadership style on the performance of students with a high or low need to achieve. Those who were achievement oriented performed best under a PM leader. In groups whose members had a low need to achieve, performance was best under a P-type leader.

Several studies obtained results suggesting that the style of supervision interacted with situational variables to influence productivity and satisfaction with the job. For example, Lundquist (1957) reported that foremen who are worker oriented produce better results in small groups than in large groups. In an Indian study of officers in central government departments, Srivastava and Kumar (1984) demonstrated that high task and high relationship styles of leadership both contributed to the effectiveness and adaptability of the middle-level officers; however, they did not do so for the junior-level officers. Nealey and Blood (1968) showed that among nurses in a Veterans Administration hospital, task-oriented first-level supervisors received higher performance appraisals, but it was the people-oriented second-level supervisors who received such higher performance appraisals. Although the subordinates’ job satisfaction was correlated significantly at both levels with the supervisors’ people orientation, task orientation contributed to the nurses’ job satisfaction at the first but not at the second level of supervision.