In Ayn Rand’s (1957) novel Atlas Shrugged, E. Locke found the prescription for heroic business leaders like Jack, who formulated rule for business leaders: face reality as it is, not as it was or as you wish it to be (Tichy & Sherman, 1993). Although the many current business scandals would suggest otherwise, honesty and candor are needed to avoid self-deception and unethical behavior. Failing executives refuse to face reality. Characteristics of business heroes, according to Rand and Locke, are independence, self-confidence, an active mind, vision, and competence. They also need sufficient intelligence to understand their markets and causal connections of consequence and the ability to accurately generalize from what they have observed. They need to have passion in their work. As was already noted in Chapter 17 about autocratic leaders, these tough-minded, directive, task-oriented CEOs are best known for their success and effectiveness in turning around large, previously successful businesses that were encrusted with strong bureaucracies which failed to adapt to changes in their markets. Examples of business leaders illustrate that some whose style is directive and task-oriented may be successful and effective in reaching their goals and satisfying their constituencies. Other examples can be found of business leaders who were successful and effective by being more consultative, participative, and relations-oriented. Generally, they need to be both directive and participative as well as concerned about tasks and relationships.

The more directive leaders, such as Lou Gerstner at IBM and Jack Welch at General Electric, were likely to ask a lot of direct questions; they made some subordinates feel that a meeting was an inquisition rather than a consultation. They made shareholders happier but some employees unhappier. Lou Gerstner was described as tough, ferocious, and driven, yet respected by associates. At the same time, he contributed a great deal to philanthropies and worked hard to invigorate educational systems in many locations. He was a demanding boss, was highly disciplined, stayed focused, set very high standards, and could go beyond less important matters to get at key issues. He had earned a degree in engineering magna cum laude and had previously been a successful top executive at American Express and RJR Nabisco. He envisioned that giant IBM, as a smaller firm with fewer hierarchical levels, would be better able to adapt and compete in the world marketplace. He consolidated operations, closed plants, sold subsidiaries, and laid off many managers and a large number of employees. He wanted to take advantage of IBM’s potential to offer consulting and a full range of services to provide an integrated information system for its business customers. He brought in 60 new executives and took the firm from bleeding losses back to profitability again (Waga, 1997). His legacy continued after he retired: IBM continued to divest itself of much of its computer manufacturing business and reduced its barriers to integrating its efforts with non-IBM programs and products.

Jack Welch of General Electric projected himself in his 1997 annual letter in which he said that grade A leaders have

a vision and the ability to articulate that vision so vividly and powerfully to the team that it also becomes their vision. … [These leaders have] enormous personal energy … and the ability to energize others … [The leaders] have the … courage to make the tough calls. … [In engineering], they relish the rapid change in technology and continually re-educate themselves. In manufacturing, they consider inventory an embarrassment. … In sales … they emphasize the enormous customer value of the Six Sigma quality program that differentiates GE from the competition. In finance, “A” talents transcend traditional controllership. The bigger role is full-fledged participation in driving the business to win. (Henry, 1998, p. 7a)

Welch made sure his frank and honest opinions on management and operations were known and were a guide to GE’s future. Welch demonstrated his ability to change a large firm with strong historical institutions. He remained personally involved in everyday matters. He charted clear, specific directions for GE, emphasizing its core businesses and venturing into new businesses. He made GE fast and flexible. He invested heavily in R & D to ensure GE’s future, reduced its top-heavy hierarchy, and reduced the number of its employees. In his first three years in office, he reduced GE’s employees by 18%. Welch insisted on consolidating GE’s 150 businesses into 15 lines, and these lines reduced to three circles: services, industrial automation and high tech, and manufacturing. Executives were under orders to make every business they ran either first or second in market share. Businesses without the potential to grow were divested and plants closed. They were replaced with others judged as having more potential. Many of the acquisitions were made in Europe and Asia. Under Welch, decisions were made more rapidly. He made it possible in 20 years for GE to become one of the largest and most successful multinational conglomerates (Lueck, 1985; Wall Street Transcript, 1985; Forbes, 1985).

Other examples of directive leaders are Jeffrey Immelt and Michael Armstrong. Jeffrey Immelt was appointed CEO of Welch’s successfully restructured GE. Immelt took charge following the many financial scandals exposed among top corporate managers at WorldCom, Enron, Tyco, and elsewhere. With concern for ethical standards of top management, he reformed the board of directors by increasing the number of independent outsiders, strengthening its auditing committee, and removing directors with conflicts of interest. Directors were asked to visit two GE businesses each year, without HQ management, to have frank discussions with operating managers. Immelt emphasized consensual management and teamwork in his directiveness (Hymowitz, 2003). Michael Armstrong accepted the CEO position at Hughes Aircraft, informing the current top management team that he admired them but they should either accept his vision for restructuring Hughes or resign. Hughes then had a strong culture focused on product development. A need for restructuring had been recognized but not implemented. Armstrong successfully directed reorganization toward market needs and increased revenue growth (Cole, 1993).

Who decides? The leader? The led? Both? On what does the answer depend? What are the consequences? Should leaders give directions and tell followers how to do the work, or should they share with followers the need for solving problems or handling situations and involve them in working out what is to be done and how? Is there one best way? Eleanor Roosevelt (April 16, 1945) noted that international peace required both: “a leader may … point out the road to lasting peace, but … many peoples must do the building.” Numerous humanistic researchers and writers support the need for participative leadership—in which the leader and the led jointly make the decision. The conventional wisdom is that participative leadership is preferred to directive leadership, and that participative leadership is more satisfying and effective than directive leadership. A survey of 485 upperlevel managers from 59 industrial firms agreed, but did not install participative systems (Collins, Ross, & Ross, 1989). As Wagner (1994) noted, in 11 meta-analytic reviews of studies, participation does have positive effects on performance and satisfaction, but the average size of these effects is small enough to raise questions about their practical significance. In many contexts, leader direction may still be of consequence. Depending on circumstances, leader direction may be effective (Hogan, Curphy, & Hogan, 1994). Furthermore, the same leader who is participative at times may also be directive at other times, with equal effectiveness. Their frequency is positively correlated rather than independent of each other.

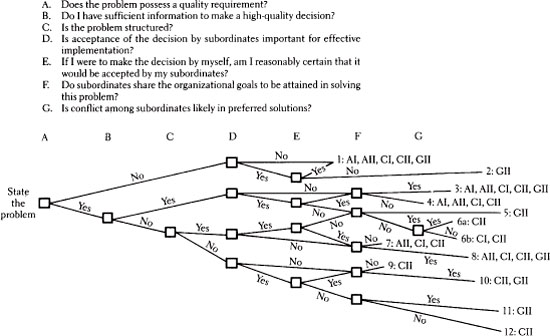

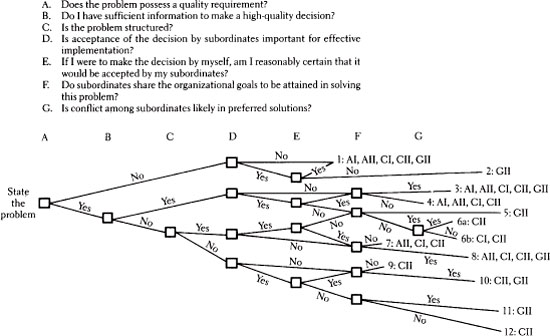

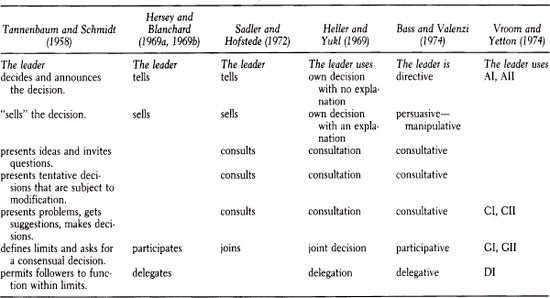

Most leaders, managers, and supervisors are both directive and participative, depending on the circumstances, but in different amounts. Tannenbaum and Schmidt (1958) suggested that direction and participation are two parts of a continuum, with many gradations possible in between. At one extreme of the continuum, directive leaders decide and announce the decision to their followers. They give directions and orders to followers without explaining why. These leaders expect unquestioning compliance; participation in the decision by followers is minimized. At the next gradation, leaders sell the decision. They accompany their orders with detailed explanations to persuade followers and manipulate or bargain with them. At the third gradation, (in between directive and participative leadership), leaders consult with followers before deciding what is to be done. They present ideas and problems and invite questions. At the fourth gradation, participation by both leaders and followers occurs. Leaders define limits and ask for a consensual decision. Followers join in deciding what is to be done. At the fifth gradation, leaders delegate to the followers what is to be done, and the leader’s participation is minimized. At this gradation, within the established limits and constraints, the followers decide what to do; the leaders need to review what was delegated. At this extreme of the continuum, some leaders may completely abdicate their responsibilities.1 Similar continua were advanced by many others (Hersey & Blanchard, 1969a, 1969b; Heller & Yukl, 1969: Sadler & Hofstede, 1972; Bass & Valenzi, 1974; Vroom & Yetton, 1974; Drenth & Koopman, 1984; and Scandura, Graen, & Novak, 1986). Scores could be generated to describe points on the continuum.

Directive leadership implies that leaders play the active role in problem solving and decision making, and expect followers to be guided by their decisions. There are two types of directive leadership. In one type, the leader makes the decisions for the followers often without an explanation and without consulting or informing them until he directs them to carry out his decisions. This type will be italicized (directive) when referred to. Other directive leaders play a more active role and try to persuade their followers to accept them. They gain acceptance of their proposals by using reason and logic (Berlew & Heller, 1983). They may assert an expectation or need and offer rewards, or they may coerce, threaten, and exert pressure to gain acceptance. They may generate charismatic identification to motivate and build commitment. They may try partial disengagement by backing away from time-consuming issues with a lower priority and by concentrating colleagues’ attention on more important issues. Unlike participative leaders, directive leaders do not ask their followers to get involved in making decisions. They direct followers’ activities and give permission to their followers to carry out duties as the leaders see fit to do (Muszyk & Reimann, 1987). If in a position of authority, the directive leader may make decisions for him-or herself and others. Directive leaders may be persuasive as they attempt to raise their followers’ efficacy beliefs. Such persuasion will depend on the leader’s rationale, the followers’ confidence in the leader, and the leader’s emotional, verbal and nonverbal expression (El Haddad, 2001). Directive leaders may decide, announce their decisions, and give orders without consulting followers and colleagues beforehand or after consulting with them.

Participation, when italicized (participation), refers only to sharing in the decision process. There are different types of participative leaders who may draw followers out, listen actively and carefully, and gain acceptance through engaging colleagues in the planning or decision-making process (Berlew & Heller, 1983). Participation may refer to a particular way of leader-subordinate decision making in which the leader equalizes power and shares the final decision making with the subordinates. Consensus is sought. Participative leadership aims to involve followers in decision processes—in generating alternatives, planning, and evaluation. Such involvement is expected to enhance satisfaction and performance (Stewart & Greger sen, 1997), but such expectations do not always materialize. Wilson-Evered, Hartel, & Neale (2001) found participative decision making highly correlated with supportive leadership of 277 Australian hospital employees for their ideas and objectives.

Roberts and Thorsheim (1987) note that participative leaders express their doubts, concerns, and uncertainties; verbalize their problem-solving processes; ask questions of followers and listen to the answers; reflect feelings; and paraphrase, summarize, acknowledge, and use followers’ ideas. Participative leaders use group processes to promote follower inclusion, ownership, involvement, consensus, mutual help, cooperative orientation, and free and informed choice. These leaders try to avoid unilateral control, hidden agendas, and inhibition of expression of feelings and relevant information. Additionally, according to West (1990), the leaders provide safety for followers by creating a nonthreatening environment in which the participants can be involved in decisions that affect them.

“Participative leadership” suggests that the leader makes group members feel free to participate actively in discussions, problem solving, and decision making. It implies increased autonomy for followers, power sharing, information sharing, and due process (Lawler, 1986). Participation implies that followers have a “voice” and influence in deliberations (Wright, Philo, & Pritchard, 2003). But freedom and safety to participate do not mean license. In participative decision making, the leader remains an active member among equals. The belief that it is safe to speak up depends not only on one’s immediate supervisor but also on senior leaders higher in the hierarchy (Detert, 2003). In Europe, employee participation is seen as depending on the acceptance of varying rules of industrial democracy developed for middle management (Jaeger & Pekruhl, 1998).

Specific differences can be seen in the way directive and participative leaders communicate with their subordinates (Sargent & Miller, 1971). For instance, different uses would be made of palliatives and sedatives. The brisk directive leader is likely to say, “I want you to …” The more sophisticated directive leader is likely to ask, “Would you be kind enough to … ?” The participative leader would ask, “Would it be a good idea if we … ?”

Example: An Effective Leader Who Was Directive and Participative. Horatio Nelson was both directive and participative. Clearly, Nelson made the decision how his fleet was to be positioned for the battle of the Nile, but prior to making the decision, he called all his captains aboard his flagship to obtain their opinions about the best way to station the ships of the line. He did not take a vote nor ask for consensus. The decision was his alone. Paramount was his vision of the overwhelming need to find and destroy the French fleet, even at the cost of many British lives, in order to cut off Napoléon and his troops, just landed in Egypt. As usual, Nelson’s disposition of his ships was innovative. His fleet had been brought to a high state of readiness by his attention to continuous training and his own practice (unusual for the era) of “walking the talk”—conversing one-on-one with officers, seamen, and marines, and cultivating his own image of courage and bravery. Part of Nelson’s orders delegated to each ship’s captain the responsibility for making decisions when his ship had to engage in a general melée (Walder, 1978).

When participation takes the form of delegation, it does not mean that the leader abdicates his or her responsibilities. The leader may follow up delegation by reclarifying what needs to be done, giving support and encouragement, and making periodic requests for progress reports, as well as by giving praise and rewards for subordinates’ successful efforts (Bass, 1985a). Delegation should not be confused with laissez-faire leadership. A leader who delegates still remains responsible for follow-up to see whether the delegation has been accepted and whether the requisite activities have been carried out.

Schriesheim and Neider (1988) distinguished among three types of delegation: advisory, informational, and extreme. In advisory delegation, subordinates share problems with their supervisor, asking their supervisor for his or her opinions regarding solutions; however, the subordinates make the final decisions by themselves. In informational delegation, the subordinates ask the supervisor for information, then make the decisions by themselves. Extreme delegation occurs when subordinates make decisions by themselves without any input from their supervisor. A factor analysis of a survey of 196 nurses and 281 executive MBA students disclosed the independence of these three kinds of delegation. That is, leaders who used one kind of delegation did not necessarily use the other kinds.

Delegation implies that a subordinate has been empowered by a superior to take responsibility for certain activities. The degree of delegation is associated with the trust the superior has for the subordinate. When a group is the repository of authority and power, it likewise may delegate responsibilities to individual members.

Delegation of decision making implies that the decision making is lowered to a hierarchical level closer to where the decision will be implemented. Such delegation is consistent with self-planning (see Chapter 12). Delegation is a simple way for a leader who is faced with a heavy workload to reduce time-consuming chores, and it provides subordinates with learning opportunities and multiplies the executive’s accomplishments (Anonymous, 1978). It also increases latitude and freedom for subordinates (Strasser, 1983). The act of delegation is often directive, but it can be based on a prior participative decision. Nevertheless, Leana (1984) called attention to a need to avoid confusing the “power relinquishment” of delegation with the power sharing of participation. In agreement with Strauss (1963), Heller (1976), and Locke and Schweiger (1979), Leana (1987) also noted that delegation, compared with participation, is more concerned about subordinates’ autonomy and individual development. According to 118 managers who were asked how to handle eight situations involving the assignment of a task to a subordinate engineer, some managers are willing to delegate regardless of the circumstances. But other managers are unwilling to delegate because of any one of three considerations: (1) Some do not delegate because they do not feel confident in the capabilities of their subordinates. (2) Some avoid delegating because they think the task is too important to be left to the subordinates. (3) Some are unwilling to delegate because of the technical difficulty of the task (Dewhirst, Metts, & Ladd, 1987).

When executives call meetings ostensibly to reach shared decisions but actually to announce their own decision to subordinates (Guetzkow, 1951), they are practicing token participation. They are also practicing this when they invite the wrong people to participate, knowing in advance that these people lack genuine interest or have conforming tendencies. Halpern and Osofsky (1990) criticize management by objectives (Drucker, 1954)—which purports to be participative—as unrealistic; they say that it fails to protect employees against managers’ manipulation, arbitrariness, and retaliation for speaking out about problems. Furthermore, employees may lack incentives and the necessary expertise to evaluate issues.

Holding frequent group meetings does not necessarily imply participative leadership. Guetzkow and Kriesberg (1950) found that leaders may use meetings to sell and gain acceptance of their own solutions, as well as to explain their own preferences. These executives see meetings as a way to transmit information and to make announcements, rather than as an opportunity to share information and opinions or to reach decisions. According to Rosenfeld and Smith (1967), subordinates recognize this phony participation and respond negatively to it.

If one can assume that followers in formal organizations appreciate autonomy, one should expect that leaders who say they delegate freely will be described as considerate. Employee satisfaction should also be highly related to delegation. But the effects obtained by Stogdill and Shartle (1955) were marginal. Subordinates often feel that their superiors do not really delegate to them the authority to accompany the responsibilities they are given. Subordinates feel that superiors delegate work they don’t want to do themselves. Superiors may believe they are delegating, but their subordinates may see this as abdication—a most unsatisfying state of affairs for subordinates.

Some leaders risk participative decision making (consultation, participation, or delegation) only when a high-quality solution is not needed. Other leaders push for participation regardless of the need for it and despite the extra time it takes (Wright, 1984–1985). Participation has become an ethical imperative for some of its advocates, but Locke, Schweiger, and Latham (1986) argued that it should be seen as a managerial procedure which is appropriate in only some situations, because its effects—although possibly satisfying to followers—may fail to contribute to productivity. In some circumstances, directive leadership may result in both higher productivity and greater satisfaction. Participation is usually thought to enhance subordinates’ compliance with decisions to change (Carson, 1985; Kanter, 1983); however, direction may be better for envisioning what needs to be changed. Some studies have reported that neither directive nor participative leadership made much difference in outcomes. McCurdy and Eber (1953) observed that groups in which free communication and decision making were practiced did not perform more effectively than groups in which the leader made all the decisions. Similarly, neither Spector and Suttell (1956) nor Tomekovic (1962) found differences in productivity between participative and nonparticipative groups.

In a study of 20 small shoe-manufacturing firms, Willits (1967) found that neither the degree of delegation by the president nor the extent of participation by executives in decision making was related to measures of the companies’ success. Heyns (1948) and W. M. Fox (1957) also found no differences of consequence.

Lawler (1986) argued that participation is a way for U.S. business to offset foreign competition and to deal with increasingly specialized work and the higher labor costs associated with some of it. But clearer goals and directions could also help. The pressure for more participation in the workplace and involvement in decisions about work has been fostered in the United States by workers’ greater expectations for upward mobility and their desire for more interesting work, but Lawler (1985) pointed out that education has not equipped many to participate effectively at work. Participative management requires an appropriate organizational design, as well as a design that is relevant to the employees’ backgrounds, motivation, and abilities. Employees with more education are more concerned about participating in decisions that affect their work (Wright & Hamilton, 1979). In the shift of the management of libraries from direction to participation, Sager (1982) noted that the roles of management and staff at all levels needed to be shifted, along with essential changes in regulations and policies.

Tannenbaum and Schmidt (1958) thought that participation and direction were based on how much authority the superior used, relative to how much freedom the subordinates were permitted. Bass (1960) noted that participative leadership required leaders with power who were willing to share it. With their power, such leaders set the boundaries within which the subordinates’ participation or consultation was welcomed. In contrast, with the powerless leader, as in the leaderless group, a struggle for status occurred among group members.

Graves (1983) noted that two of the three categories of concepts used by students to cluster 23 supervisory behaviors indicated their implicit theories of leadership. They dealt first with task direction (“Sets goals for employee performance”) and second with participation (“Asks employees for opinions and suggestions”). The third category of concepts dealt with reward (“Praises those who perform well”). Although conceptually independent, the dimensions of task direction and participation correlated .53 for the students’ implicit theories of leadership.

Similarly, Bass, Valenzi, Farrow, and Solomon (1975) found that according to subordinates’ descriptions of their superiors, direction and persuasive negotiation were positively correlated. Even more highly intercorrelated were democratic consultation, participation, and delegation. However, 46 judges, using response-allocation procedures, could readily and reliably discriminate among the specific behaviors involved in (1) direction and (2) negotiation, as well as among the behaviors involved in (3) consultation, (4) participation, and (5) delegation. The five styles were found to be conceptually independent, although they were correlated empirically. For instance, the judges clearly saw consultation as a different pattern of behavior from, say, delegation; nevertheless, the same managers who were most likely to consult were also more likely to delegate, according to their subordinates’ descriptions (Bass, Valenzi, Farrow, & Solomon, 1975). Similar results were reported by Filella (1971) for 77 Spanish managers, as well as in Saville and Holds-worth’s OPQ manual (Anonymous, 1985) for 527 British professionals and managers.

Nevertheless, three styles—consultation, participation, and delegation—are distinct and may, to some degree, have different antecedents and consequences. Factorial independence of each of the styles would make research with them easier; however, maintaining conceptually distinct but correlated styles remains viable and useful. (In the same way, analyses of body height and body weight continue to be separated, although height and weight are also empirically correlated. In general, tall people are heavier than short people, but it remains useful to talk about how people differ in height and how they differ in weight, as well as how they differ in stature or body mass, the combination of height and weight.)

With growing use of teamwork and empowerment of team members has come leadership behavior by the formal head of the team and shared leadership by team members. The team leaders do considerably more than members to empower the members and are more directive than the members themselves. Leaders and members appear otherwise to display similar participation in aversive, transactional, and transformational leadership behavior (Pearce & Sims, 2002).

Additional evidence that the same managers empirically exhibit many of the conceptually different styles of decision making is obtained from examining the intercorrelations in style found in survey studies. Consultation, participation, and delegation are highly intercorrelated. That is, consultative managers also tend to be highly participative and delegative. The intercorrelations were above .60 for a sample of 343 to 396 respondents who described their organizational superiors. Even the extent to which managers are directive tends to correlate positively with the extent to which they are manipulative or negotiative, .25; consultative, .31; participative, .28; and delegative, .13. Consultation, the most popular style observed among 142 assistant school superintendents in Missouri, correlated highly with participation (.64) and delegation (.47). Actually, all five styles have active leadership in common, and all are the opposite of inactivity and laissez-faire leadership.

Despite these intercorrelations, Wilcox (1982), using the Bass-Valenzi Management Styles Survey, reported systematic differences for the independent contributions of direction, consultation, and delegation to satisfaction with and the effectiveness of leadership, even after the effects of many other organizational and personal variables of the leader and the led were removed. Chitayat and Venezia (1984) conducted a smallest-space analysis for 224 Israeli managers and executives from business and nonbusiness organizations and attained patterns for the Bass-Valenzi survey measures showing that direction and negotiation (persuasion and manipulation) were closer together but distant from delegation, participation, and consultation—which, in turn, were closer to each other in usage by the respondents. Consistent with the reports of Bass, Valenzi, Farrow, and Solomon (1975) and Wilcox (1982) about subordinates’ descriptions of their superiors’ styles, intercorrelations of .41, .33, and .51 were found among delegation, participation, and consultation, and .23 was found between direction and negotiation for the Israeli managers. The correlations between decision styles within the two clusters were close to zero.

Some leaders and managers may lean toward inactivity. Whereas any of the preceding styles require activity, laissez-faire leadership—or abdication of responsibility and avoidance of leadership—does not. Laissez-faire leadership calls for doing little or nothing with subordinates, remaining passive, or withdrawing, as was discussed in Chapter 6. Such passivity correlates with passive managing by exception, in which the leader waits for problems to arise before taking any corrective action. This is in contrast to active managing by exception, in which the leader monitors follower performance and makes corrections as needed (Bass & Avolio, 1991).

Negotiative Leadership. The leader bargains with the follower who has a different interest or point of view. Differences are settled with persuasive arguments and agreements.

Manipulative Leadership. The leaders act shrewdly or deviously to enhance their own advantage and gain, and to exploit the followers. Manipulation can shade into falsification (see Chapter 7).

Close Supervision. Directive leadership is more likely to be exhibited by the same leaders who are also close supervisors, who do a lot of structuring, and who are manipulative and persuasive. This persuasive, manipulative emphasis has been seen in political tactics: withholding information, bluffing, making alliances, publicly supporting but privately opposing particular views, compromising, and using delaying and diversionary tactics.2 Participation is likely to be seen with general, rather than close, supervision; with the equalization of power; and with nondirective leadership.

Considerate Leadership. Participative decision-making leadership includes many elements. One of these, consideration, calls on the leader to ask subordinates for their suggestions before going ahead, get the approval of subordinates on important matters, treat subordinates as equals, make subordinates feel at ease when talking with them, put subordinates’ suggestions into operation, and remain easily approachable. Graves (undated) found that implicit task direction correlated .61 with the factor of initiating structure, and implicit participation correlated .81 with consideration, one of the two important dimensions of the Leader Behavior Description Questionnaire (LBDQ). Many elements of direction are to be found on the LBDQ scale of the initiation of structure, such as making attitudes clear, assigning subordinates to particular tasks, and deciding in detail what shall be done and how.3

Social Factors. Bass (1968c) contrasted MBA students’ and managers’ beliefs about how to succeed in business. Two social factors emerged: sharing decision making and emphasizing candor, openness, and trust. The factors involved making open and complete commitments, establishing mutual goals, and organizing group discussions. The factors coincided with ideal participative decision making as proposed by Argyris (1962) and Bennis (1964).

Transformational and Transactional Leadership. As noted in Chapter 22, contrary to many misconceptions about transformational and transactional leadership, such leadership can be directive and participative. The intellectually stimulating leader can issue instructions and participatively arouse curiosity. The inspiring directive leader can state that conditions are improving greatly. The inspiring participative leader can ask for all to merge their aspirations and work together for the good of the group (Bass, 1998).

Warrior Leadership. Related to directive leadership, the warrior style—as already discussed in Chapter 17—is most likely to emerge when conflict and opposition are present, the world is seen as dangerous and hostile, people cannot be trusted, and direction is needed. Flows of information are controlled. Results are more important than the methods used to achieve them. There is an emphasis on knowing the people that the leader is seeking to defeat or lead. Battles are selected carefully, and unnecessary fighting is avoided. There is planning and preparation for future militant contingencies (Nice, undated).

Persuasive Rhetoric. Directive leadership through persuasive rhetoric was a theme of Aristotle and much of classical instruction in general. Orators from Martin Luther to Martin Luther King Jr. have followed Aristotle’s prescription for persuasion: identify the discontent among audiences, name the enemy, and provide the needed response. Give the restless a voice, a motive, and legitimacy (Monty, 2004).

Forcing, Coercing, and Controlling. These forms of directive influence involve pressure or persuasion by a leader to induce follower compliance and avoid undesired outcomes. Ordinarily, continued use of force by a leader is likely to generate ill feelings and resistance. However, Emans, Munduate, Klaver, et al. (2003) showed that 145 police officers complied effectively with supervisory orders if forcing influence was interspersed over time with non-forcing influence. Hard tactics of persuasive direction are employed, such as giving orders without explanation, threatening unsatisfactory performance evaluations, and getting the backup of higher authority, when the persuader has the power to do so, when resistance is expected, or when the subordinate is violating norms. Soft tactics of persuasion are employed, such as acknowledgment of the subordinate’s goodwill and ability, when the influencer is at a disadvantage. Rational tactics of persuasion are employed if power is balanced, if no resistance is anticipated, and benefits for compliance will be mutual (Kipnis & Schmidt, 1985). Tight or loose controls are likely to coincide with the leadership styles of direction and participation. As Avolio (1999) noted, leaders will maintain tight controls if they don’t trust their subordinates. There are reciprocal effects. When employees are allowed to participate more fully in decisions, they are likely to feel that they are more trusted by their leaders. They may confirm this by showing better organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). Van Yperen, van den Berg, and Willering (1999) demonstrated in a study of employees from 10 departments in a Dutch company that employee participation in decision making fostered better employee OCB.

A popular stereotype of the ideal leader is the decisive, directive, heroic order giver. The prototypical supervisor in the workplace of MBA students with full-time jobs had these directive transformational characteristics (Bass & Avolio, 1989). Yet in the behavioral science literature, participative decision making is most commonly advocated. And managers themselves are most likely to favor a consultative style. Actually, Heller and Yukl (1969) and Bass and Valenzi (1974) have shown that neither extreme direction nor extreme participation is reported most frequently by subordinates in describing their superior. Rather, subordinates most often see their superior as consulting with them. Thus on a scale of frequency ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always), according to over 400 subordinates from a variety of organizations, the average frequency with which superiors were observed to exhibit each of the styles on many items of supervisory decision-making behavior was as follows: consultation, 3.10; participation, 2.65; delegation, 2.46; direction with reasons, 1.97; direction without reasons, 1.90; and manipulation, 1.88 (Bass & Valenzi, 1974). In agreement, H. R. Gillespie (1980) concluded, from self-reports of 48 manufacturing executives, that participation, particularly consultation, was more frequent, especially among executives at the top level. Kraitem (1981) likewise found that consultative leadership was favored in the self-reports of top executives in financial institutions and that there had been a shift away from more directive approaches.

Manipulation and negotiation were reported to occur least frequently, perhaps because of the greater subtlety of manipulative behavior, which is more difficult to discern when it happens. The most artful manipulative behavior is that which is misperceived as participative. There is less reliability in judgment about manipulation than in judgment about other decision-making styles. Subordinates feel they are being manipulated when they think managers know in advance what they will decide and what they want the subordinates to do. These managers strike bargains and play favorites. Such manipulative behavior tends to be exhibited by directive managers but not by managers who generally tend to be participative (Bass, Valenzi, Farrow, & Solomon, 1975).

For followers, a leader who is a consistently autocratic or consistently laissez-faire leader in all situations is likely to be least satisfactory and least effective. Generally, followers will favor participative leadership over directive leadership. Nonetheless, subordinates may agree with their superior that supervisory direction is called for in a crisis and that consultation is indicated when subordinates are knowledgeable, experienced, and expert. Followers are likely to applaud their superior’s flexibility in being directive in the first situation and consultative in the second. In fact, few leaders use only a single style; most use a variety of styles, ranging from extreme direction to extreme participation. Among 124 middle-and first-level supervisors, W. A. Hill (1973) found that only 14% of the supervisors were seen as likely to use the same one of four styles in four different hypothetical situations.

Bass and Valenzi (1974) obtained sharper results with 124 subordinates who described how frequently their superiors actually used six styles, ranging from deciding without explanation to delegating decisions to subordinates. A manager was classified as exhibiting a single style if the subordinate indicated that only one of these styles was displayed by the manager “very often” or “always,” and the remaining styles “never” or “seldom.” Managers were classified as exhibiting a dual approach if they were described by their subordinates as displaying two styles “very often” or “always,” and the other styles “never” or “seldom.” Managers were classified as exhibiting a multi-style approach if they were described as displaying three or more of the six styles “sometimes,” “fairly often,” “very often,” or “always.” Of 124 subordinates, less than 4% indicated that their superior exhibited a single style or a dual approach; 117, or almost 95%, indicated that their boss exhibited a multistyle approach.4 Consistent with Bass and Valenzi’s findings, Hollander (1978) noted that although political leaders, in particular, often try to project a consistent image to a wide audience, based on a particular style that is uniform across situations, most change their style after they are elected; they also change their style from one constituency to another.5 History is replete with examples illustrating that the most powerful dictators may also be strong advocates of consultation.

Lenin, according to his biographers, frequently consulted his immediate subordinates (Bass & Farrow, 1977a). Mao Zedong urged party leaders to be consultative and instructed them carefully on how to carry out a doctrine stressing consultation: “We should never pretend to know what we don’t know, we should not feel ashamed to ask and learn from people below, and we should listen carefully to the views of the cadres at the lower levels. Be a pupil before you become a teacher; learn from the cadres at the lower levels before you issue orders” (Burns, 1978, p. 238). But in his later years, Mao could also be ruthless as a leader, unleashing his Cultural Revolution on the Chinese population.

Differences in Problems. The overwhelming tendency for managers to use multiple decision-making styles is seen most clearly in studies of how the same managers use different styles depending on the nature of the problem. Thus McDonnell (1974) found that when 226 respondents were asked whether they would be autocratic, consultative, participative, or laissez-faire, each chose a different style depending on which of 12 problem situations was presented for consideration. Heller and Yukl (1969) and Heller (1972a) demonstrated that a senior manager varies his or her style according to the nature of the required decisions. For example, prior consultation was the modal style for decisions that were critical to individual staff members but not to the organization. Participation in all three forms was most frequent for decisions of importance to subordinates and least frequent for decisions of importance to the company. Supervisory delegation and supervisory decision making without explanation were most frequent for decisions that were unimportant to both the leader and the subordinates. Using a different method (to be detailed later in this chapter), Vroom and Yetton (1973) came up with similar results. Several thousand managers indicated the decision-making style they would employ if confronted with different kinds of cases requiring or not requiring high-quality solutions and subordinates’ acceptance. Only about 10% of the variance in response could be attributed to the personal tendencies of the managers to be more directive or more participative; 30% of their responses depended on whether high-quality solutions and subordinate acceptance were required. Hill and Schmitt (1977) tested a shortened version of Vroom and Yetton’s method and found that 37% of the variance in the leaders’ decision-making style was due to ease-requirement effects and only 8% was due to the effects of the respondents’ individual dispositional differences. These results tended to be relatively insensitive to the hierarchical levels dealt with in the cases presented to the managers (Jago, 1978a). This was so despite the fact that, as was noted in Chapter 14, both the authority to be directive and the authority to be delegative increase as one rises in the organizational hierarchy (Stogdill & Shartle, 1955). Such increased authority makes it possible for superiors to delegate more responsibilities to subordinates. But it also allows the superiors to be more participative.

In Wilcox’s (1982) dissertation, agreement was quite close between the school superintendent’s self-descriptions of their directiveness, participation, and delegation and the descriptions provided by their subordinates. But the superintendents believed they were more consultative and less negotiative than their subordinates thought they were. Generally, when managers’ self-rated styles are contrasted with descriptions provided by their subordinates, one is likely to find many more managers who see themselves as favoring their subordinates’ participation than subordinates who see such participation occurring. Also, many authoritarian leaders would be surprised to learn that their subordinates say they are far more directive than they believe themselves to be. Harrison (1985) studied 30 supervisors and their 234 college-educated subordinates in a large social service organization. There was little correspondence between the subordinates’ feelings of participation in decision making and the supervisors’ tendency to see themselves as participative. For the superiors, participation meant interacting with subordinates; but for the subordinates, it also meant that the subordinates could both send and receive information related to their own desires. Moreover, the subordinates’ judgments of the extent to which their superior was participative correlated .61 with the interpersonal support they received from the superior, .59 with the team-building activities led by the superior, and .30 with the accuracy of the information they felt they received from the superior. The superior generally failed to recognize that any of these actions was connected to being participative.

A Harris (1987) poll revealed still another aspect of the discrepancy between managers and white-collar workers. Although 77% of the workers considered it very important to be allowed to participate in decisions that controlled their working conditions, only 41% of their superiors agreed with them. Some samples of leaders subscribed to direction rather than participation. None of 450 interviewed Australian managers rated their executive superiors as collaborative in organizational development. They regarded the high and medium performers as more tough and directive in style when it came to making organizational changes. The lower performers were viewed as careful, timid fine-tuners (Heller, 1994).

As was already noted, different studies using a variety of methods showed that leaders in organized settings said they preferred to be consultative and were most often seen by their subordinates as consultative. Such consultation involved their subordinates to some extent in the decision process, but the supervisors reserved the final decision for themselves. At the same time, a given leader was seen to use the whole range, from direction to delegation, in varying amounts. However, different patterns of usage were revealed—some leaders were more directive on the whole, whereas others were more participative. Both deductive and inductive research point to a variety of factors that predispose leaders to pursue one style rather than another. These antecedent conditions include the attributes of the leader and of the subordinates; their preferences, goals, tasks, and assignments; and the organizational and external environment.

Some argue that direction or participation will depend on the nature of the situation; others state that it depends on the leader’s judgment of the situation (Hersey & Blanchard, 1977; Vroom & Yetton, 1973). Still others find that the predispositions of the leader are most significant (Fiedler, 1967a).

Situations have an obvious impact. On the one hand, crisis conditions may make any leader directive. On the other hand, a leader of a project team that is composed of experts from different fields will most likely benefit the project by being participative. Nevertheless, it may be that personality has more of an effect on a leader’s being directive, but the situation has more of an effect on the leader’s being participative (Farrow & Bass, 1977). Both the contingency and the noncontingency theorists may be right. Frequency of directiveness may be mainly a matter of personality; frequency of participation may hinge mainly on contingent factors. Farrow and Bass (1977) found, for 77 managers who were described by their 407 subordinates, that situational factors, as seen by the managers or by the subordinates, were irrelevant in determining whether a manager would be directive. Path analyses indicated that managers who were most frequently directive, according to their subordinates, were highly assertive and regarded people as fundamentally unfair. Such managers were highly satisfied with their own jobs. If the managers had short-term rather than long-term objectives, their subordinates saw them to be manipulative and negotiative. These results went beyond various organizational, intrapersonal, and personal attributes of the subordinates. However, the amount of participation seen by subordinates depended on the extent to which the manager perceived that the subordinates had discretionary opportunities and highly interdependent tasks.

Self-confidence and a personal sense of security were likely to have a strong effect on a leader’s tendencies to be directive or participative (Bass & Barrett, 1981). Vroom (1960a) found that managers with authoritarian personalities, as measured by the F Scale of Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, and Sanford (1950), were more directive. The lower the managers’ need for independence and the higher their degree of authoritarianism, the higher was their directiveness. Belief in the legitimacy of the manager’s prerogative to plan, direct, and control had similar effects. Managers who characterized themselves on personality inventories as unwilling to believe that people are fair-minded were more likely to be directive, according to their subordinates. This finding was consistent with the proposition that managers will be directive because they believe in Theory X: that employees cannot be trusted (McGregor, 1960). Conversely, those who felt people were fair-minded tended to be participative (Farrow & Bass, 1977). Among 122 undergraduates, dominance correlated with effectiveness as directive leaders. Dominance and supportiveness correlated with effectiveness as participative leaders (Sorenson & Savage, 1989).

Educational background also made a difference. Bass, Valenzi, and Farrow (1977) found a correlation of .37 between the educational level of 76 managers and their tendency to be participative. If leaders were women, more participative leadership was expected of them (Pelletier, 1999).

Myers-Briggs Types. There is a consistent linkage between one’s thought processes and the tendency to be directive or participative. For example, according to a study of 55 managers and executives by O’Roark (1986), who correlated scores on the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator with the Bass-Valenzi preferred management styles, thinking types were most directive and feeling types were least directive; sensing types were least negotiating and intuitive types were more consulting. Schweiger and Jago (1982) reported that among 62 graduate business students, Myers-Briggs intuitive types tended to choose fewer participative solutions to the problem set of Vroom and Yetton (1974), whereas sensing types tended to choose more such participative solutions. Overall, personality seemed less important than situational determinants in the choices that were made.

Risk Preferences and Propensities. Whether managers delegate certain duties to subordinates may depend on whether the managers enjoy doing the tasks themselves, as well as on their willingness to take risks and wait for others to succeed (Matthews, 1980). Managers also need to feel secure and confident in themselves and in their subordinates (Hollingsworth & Al-Jafary, 1983). The riskiness of a decision to a supervisor is decreased if it is to be implemented on a trial basis. In a simulation with 143 bank employees under such conditions, Rosen and Jerdee (1978) found the leaders to be more willing to engage in participation when decisions were to be implemented on a trial basis than when decisions implied permanent solutions. The risk of decisions is increased for top managers who face intense competition from the marketplace. In such situations, the top manager tends to be more directive and highly controlling in some decisions—say, about production, purchasing, and cost control—and more participative in others, such as those dealing with raising capital, research and development, policy changes, and marketing strategies (Khandwalla, 1973).

Power. Leaders with power can be more directive. Leaders who are esteemed and valued by subordinates, who are acknowledged as experts, and who are seen by subordinates to control rewards (that the leaders can allocate among the subordinates) have the power to be directive (Mulder, 1971; Raven, 1965b). In addition to the effects of expert, reward, and referent power on being directive, there are also effects of coercive and legitimate power. If the power of leaders is suddenly increased in an experiment, the amount the leaders can be directive is also increased, and in fact the leaders do tend to increase their directiveness (Shiflett, 1973). But, paradoxically, leadership power is required to create participative circumstances. Whether power results in direction or participation depends on other factors. The results are decidedly mixed. Chitayat and Venezia (1984) noted that in Israeli business organizations, leaders’ self-reported power contributed to their being directive, but the reverse occurred in the Israeli armed forces and governmental agencies. In such bureaucratic organizations, powerful leaders were more participative because the rules and procedures required directiveness, and only executives with more power could be participative if they chose to be. However, Hord, Hall, and Stiegelbauer (1984) found that more powerful school principals were more directive than were their less powerful assistant principals, teachers, or curriculum coordinators.

Experience. Heller and Yukl (1969) reported, in a study of 203 British managers at all hierarchical levels in 16 organizations, that despite their greater power and status, senior managers, particularly those who had been in their positions for a considerable time, were more likely than junior managers to share in decision making with their subordinates. Seversky (1982) found that more delegation was practiced by school superintendents who had more experience in their jobs. Likewise, Pinder, Pinto, and En gland (1973) found that older managers tended to be more participative, whereas younger managers tended to be more directive. Age, however, was unrelated to participativeness in a study of 48 manufacturing executives (H.R. Gillespie, 1980).

Ideological Beliefs. Locke and Schweiger (1979) provided academic and management advocacy for the moral reasons for participative leadership. The humanist movement argued that participative leadership was right and good. Directive leadership was questionable (Maslow, 1965). Likewise, participative leadership was regarded by some leaders as morally correct in a democratic society. Some extremists, such as Rost (1993), suggested that engaging followers (relabeled “collaborators”) as participants in decisions is always the right thing to do. For Rost, the old paradigm to be discarded was doing what the leader wishes. The new paradigm to replace it was doing what both the leader and the collaborators wished to do. Nonetheless, Sagie (1997) pointed out that although a directive, tell-and-sell strategy of assigning goals could be as productive in performance and the quality of decision making (Sagie, 1994), and that assigning goals could be as effective as participation in goal setting (Locke & Latham, 1990), the continuing arguments for participation were based on ideological reasons (Dickson, 1982) rather than empirical evidence.

As was noted in Chapter 14, there is a clear linkage between what a U.S. Navy executive officer of a ship can and does do and the responsibility, authority, and delegation of his immediate superior—the commanding officer. Stogdill and Scott (1957) correlated the responsibility (R), authority (A), and delegation (D) scores (RAD scores; see Chapter 14) of commanding officers and executive officers with the average RAD scores of their junior officers on submarines and landing ships. The executive officers tended to delegate more freely to their subordinates on both types of ships when their commanding officers exercised wider scopes of responsibility and authority and delegated more freely. Commanding officers could increase or decrease their executive officers’ workload and freedom of action. Subordinates tended to tighten their controls as superiors increased their own responsibility and freedom of action. However, responsibility and authority did not flow without interruption down the chain of command. The responsibility, authority, and delegation of subordinates were more highly influenced by the subordinates’ immediate supervisors than by the subordinates’ higher-level officers.

Some degree of agreement between the leader and the led about procedures, interests, and norms is necessary before effective participation can take place (Heller, 1969). In addition, they must concur that participation is relevant. Yukl and Yu (1999) reported that participative leadership with subordinates—like consultation and delegation—depended on the competence of the follower, task objectives shared with the leader, status of the follower as a supervisor, and favorable relations between the leader and the follower.

Relevance of Participation. Subordinates or followers vary in how much they would like to participate in decisions. As was noted earlier, Heller (1972a, 1976) found, in a number of samples in several countries, that managers used participation more frequently when decisions were more important to their subordinates than to the firm. In an overall review of the literature, Hespe and Wall (1976) demonstrated that although workers wanted to participate more than they actually were given the opportunity to do, they expressed the greatest interest in participating in decisions that were related directly to the performance of their jobs, followed by matters concerning their immediate work units. They expressed little interest in participating in general policy decisions. This finding was corroborated by Long (1979), who asked workers in a Canadian trucking company that had become wholly owned by its employees about their participation in company affairs after the employee takeover. According to Maier (1965), subordinates will prefer participation rather than direction if they are seeking personal growth, if they are striving to be more creative, and if they are highly interested in the objectives of the task. On the other hand, they may prefer a great deal of direction, guidance, and attention from their supervisor until they have mastered the job, particularly if the job does not involve much creativity but requires only attention to routine details that must be learned (Bennis, 1966c).

Followers’ Personality. Abdel-Halim (1983a), Abdel-Halim and Rowland (1976), and Vroom (1960a), among others, found that the personality traits of subordinates are of consequence to the participatory process. Just as authoritarian leaders wanted to be directive with their subordinates, so their authoritarian subordinates wanted to be directed by authoritarian leaders. Followers with authoritarian attitudes were likely to reject participative leadership. Highly authoritarian personalities wanted powerful, prestigious leaders who would strongly direct them.6

Followers’ Competence. Raudsepp (1981) suggested that managers need a comprehensive inventory of subordinates’ capabilities before deciding what duties they can delegate to subordinates and in which areas subordinates need further experience. Managers will consider participative approaches too risky when they have reservations about the competence and commitment of their lower-level employees (Rosen & Jerdee, 1977). Lowin (1968) showed that subordinates who perceived that they were not competent in the tasks to be completed were more appreciative of directive supervision than were those who thought of themselves as competent. Similarly, Heller (1969a) found that whenever managers reported a big difference in skills between themselves and their subordinates, they were more likely to use direction. The differentials in skills that were of particular importance were technical ability, decisiveness, and intelligence. Managers were more likely to engage in participation when they esteemed the subordinates for their expertise and personal qualities. Heller (1976) also found that participative leadership was favored at senior organizational levels when the competence of subordinates was high. Similarly, on the basis of a study of members of 144 work groups in 13 local health agencies, Mohr (1977) concluded that supervisors favored participation when their subordinates had more training and were at higher technical and professional levels. Sinha and Chowdhry (1981) found, in a survey of 135 Indian executives, that the executives tended to be participative if they believed their subordinates were better prepared but were more directive with subordinates who they felt were less well prepared. Locke and Schweiger (1979) also concluded that leaders are more likely to be participative when they believe their subordinates have the necessary information to contribute to the quality of decisions. In a mass role-playing experiment, Maier and Hoffman (1965) observed experimentally that the “foreman” who regarded his “subordinates” as men with ideas was more likely to lead his crew toward an integrated solution to their problem on the basis of their participation in making the decision. However, if the “foreman” thought he was dealing with difficult employees, he was more likely to direct them toward a solution he favored than to involve them extensively in the decision-making process.

In their prescriptive model, Vroom and Yetton (1973) deduced that leaders need to consider being more participative if they think they lack information that their subordinates are likely to have. The Hersey and Blanchard (1977) model assumed that the subordinates’ competence is the most important determinant of whether and when a manager should be directive or participative (see Chapter 19). Leana (1987) reported a correlation of .42 between the willingness of insurance supervisors to delegate responsibilities to their 122 subordinate claims adjusters and their judgment of the capabilities of these subordinates. Tendencies to delegate correlated .27 with the subordinates’ appraised trustworthiness. As was mentioned before, Dewhirst, Metts, and Ladd (1987–1988) found strong indications that managers were less willing to delegate if the subordinates were incompetent or the tasks were difficult and highly technical.

The interplay of the superior and the subordinate contributes to the superior’s tendency to be directive or participative. Thus in an Israeli study, Somech and Drach-Zahavy (2003) reported that demographic similarity in age, tenure, education, and sex and the quality of the leader-member exchange (LMX; Chapter 16) were conducive to participative leadership.

Differences in Power and Information. Bass and Valenzi (1974) proposed that the frequency with which a particular leadership style is used could be accounted for by the differences in power between the manager and the subordinates and by the differences in their competence or the information available to them. Shapira (1976) confirmed, through smallest-space analysis, the validity of Bass and Valenzi’s deductions. Given the managers’ power (Pm), the subordinates’ power (Ps), the managers’ information (Im), and the subordinate’s information (Is), then direction is more likely if Pm > Ps and Im > Is. Manipulation or negotiation is more likely if Pm < Ps and Im > Is. Consultation is more likely if Pm > Ps and Im < Is. Delegation is more likely if Pm < Ps and Im < Is.

Effects of the Quality of the Exchange Relationship. An analysis of 58 superior-subordinate paired questionnaires by Scandura, Graen, and Novak (1986) revealed that the quality of LMX further complicates matters. Regardless of their competence, as rated by their superiors, subordinates who perceive they are in a more satisfying exchange relationship with their superiors also believe that their superiors allow them to participate much more in decision making. But subordinates who think they are in a dissatisfying relationship will perceive such participation only if their performance has been rated highly by their superiors. If the relationship with superiors is poor and the subordinates’ performance has been rated low, the superiors will be seen as much more directive. Superiors agree with this description of the exchange relationship and its effects.

Policies, goals, task requirements, and functions constrain how directive or participative a leader can be. They also furnish objectives that the leader will see as being met more satisfactorily by either direction or participation. Both the leader and the subordinates may be constrained by rules, regulations, and schedules, demands on their time, and fixed requirements for methods and solutions over which they have no control. The requirements of a decision may be highly programmed. Greater acceptance and change by the group may be desired or required. The manager may consider the objectives to be long-range rather than a quick payoff—that is, the development of subordinates or the creation of a capable and effective operation for the long run may be more important than immediate profitability. According to Vroom (1976a), it “seems unlikely” that the same leadership style would be appropriate when the objective was to save time than when the objective was the long-term development of subordinates. If the cost of the time required of subordinates is more expensive than the value of the outcomes of their participation, directive approaches are more likely (Tannenbaum & Massarik, 1950).

Muscyk and Steele (1998) reviewed the characteristics of “turnaround” executives. When organizations are faced with crises, such executives are brought in to prevent the organization from failing. Directive leadership is required. Unpopular decisions have to be made. Subordinate autonomy and participation may have to be reined in.

Organizational Function. Chitayat and Venezia (1984) found, in their previously cited investigation of 224 Israeli executives, that differences in the frequency of use of leadership styles were associated with differences in organizational norms, climate, and structure.

Since marketing is usually under shorter time constraints than research, a directive style may be appropriate more often in work units in marketing than in research (Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967a, 1967b). Heller and Yukl (1969) found that production and finance managers tended to use directive decision making, whereas general and personnel managers were more participative.

In a study of 155 managers of police (Kuykendall and Unsinger, 1982), the managers stated that they would avoid delegating, regardless of the problem faced. Like managers in accounting, finance, and production, managers of police supervise more standardized, programmed types of jobs that permit less freedom, less flexibility, and less meaningful participation by subordinates. Nevertheless, when faced with unprogrammed personnel decisions, they could be more participative. Similar findings appeared for accountants. A study of 212 chief accountants (McKenna, undated) found that although they were generally more likely to be directive than participative, they were more likely to use consultation and participation than direction or delegation when they had to make unprogrammed rather than programmed decisions. This was also true when they had to make decisions dealing with personnel rather than with tasks. Similarly, as noted above, the police managers were more likely to be participative than directive when faced with such decisions. Service managers thought that they generally faced more unprogrammed decisions. Child and Ellis (1973) found, in a study of 787 managers in service organizations, that these managers saw their roles as less formal, less well defined, and less routine than did managers in manufacturing organizations, Miner (1973) concluded that participative management was most likely to be found in organizations of professionals. Miller (1986) advocated participativeness with R & D professionals whose work was less programmed.

Woodward (1965) studied the impact of technology on decision-making processes in 100 British firms. She concluded that in companies involved in mass or batch production, decision making was more likely to be directive but usually did not set precedents. However, in continuous-processing industries such as petroleum refining, decisions were more likely to be made by committees with considerable participation by subordinates, and these decisions had long-term implications.

Organizational Level. Stogdill and Shartle (1955) reported correlations between the tendency to delegate and the self-rated authority and responsibility of managers on the RAD scales in 10 organizations (Stogdill & Shartle, 1948). On the average, delegation correlated .17 with responsibility and .23 with authority. Since greater authority and responsibility naturally went with higher-level positions, it was not surprising to find that delegation was also higher among managers in those positions. Moreover, delegation must be practiced at higher levels because organizations cannot afford to pay high-level executives to spend their time carrying out activities that could be performed by the lower-paid staff (Major, 1984). Using the RAD scales (Chapter 14) to study large governmental organizations, Kenan (1948) also found, as expected, that executives in higher-level positions described themselves as having a greater tendency to delegate than those in lower-level positions. Browne (1949) noted that executives’ salaries related positively to their estimates of how much they delegated. D. T. Campbell (1956) reported that delegation was positively and significantly related to one’s level in various types of organizations, as well as to one’s military rank, time in one’s position, and regard for being in a position of leadership.

Blankenship and Miles (1968) observed that the level of one’s position was more important than the span of control or size of the organization in determining delegation by managers. Compared with managers at lower levels, upper-level managers not only reported greater freedom from their superiors with regard to decisions but tended to involve their subordinates more in decisions. H. R. Gillespie (1980) agreed, finding that among 48 manufacturing executives, those at the top level were more participative than were those at the next two levels below them.

A higher organizational level brings with it many of the conditions that promote greater participation, and lower organizational levels do the reverse. Senior executives are concerned with longer-range problems and policies, norms, and values. They are dealing directly with more creative, more educated, higher-status subordinates, who expect more opportunities to participate and have a greater interest in long-term commitments and in their own development. Directive practices are more prevalent at lower levels, since managers are dealing with more routine types of work, more clearly defined objectives, and less well-educated subordinates of lower status who have fewer expectations about participating in the decision-making process (Selznick, 1957). Thus in their intensive study of workers on the assembly line, Walker and Guest (1952) emphasized that supervision was likely to be more directive, particularly if the tasks were routine.

Tasks. The nature of the work may determine whether the leader will need to be more directive or participative. If the tasks are simple, direction may be more acceptable than when tasks are complex. Although Ford (1983) argued that there must be some way to measure the outcomes of tasks if tasks are to be delegated, Mohr (1971) found that the degree of “task manageability” did not increase a manager’s participatory style, but the task interdependence of the manager’s subordinates did. Understandably, Leana (1986) reported that supervisors with heavier workloads were more likely than supervisors with lighter loads to delegate work to their insurance claims adjusters.

Phase. The phase in the work or decision process will affect whether leadership should be directive or participative. Wilson-Evered, Dall, and Neale (2001) noted that direction from the top may facilitate the initiation of innovative tasks; participation may generate more support for new ideas, their diffusion, and their implementation. Heifitz (1994) used the example of the physician-patient relationship in the diagnostic-treatment process to illustrate when direction or participation should dominate. In the first phase of diagnosis and treatment, the work is technical and the physician is primarily responsible for the work. When the patient is under stress, the flow of diagnostic and prognostic information to him or her may need to be paced and sequenced. The second phase, implementation, is technical but also requires the patient to learn and adapt. Here responsibility needs to be shared between physician and patient. In the third phase, as the relationship continues, the patient needs to learn to take on more responsibility than the physician. Heller, Drenth, Koopman, et al. (1988) studied the phases in 56 decisions in three Dutch organizations. Management dominated the first (start-up) phase and the third (finalization) stage. Professional staffs and middle management were most influential in the second (developmental) phase. Participation by lower organizational levels was limited to the fourth (implementation) phase. Richard Nixon saw participation as limited to the first phase of decision making and direction as mandatory in its finalization. “I would not think of making a decision by going around the table. Of course, I like to hear everyone, but then I go off alone and then decide. The decisions that are important must be made alone” (Schecter, 1982, pp. 18, 19).

Perceived Importance of Outside Environmental Influences. Managers differ in what aspects of the outside environment they regard as most important to their work, and as a consequence they behave differently inside the organization. Bass, Valenzi, and Farrow (1977) asked 76 managers to describe the importance of economic, political, social, and legal influences on the work of their 277 immediate subordinates. These subordinates, in turn, described the frequency with which their own manager displayed direction, negotiation, consultation, participation, and delegation. Managers who tended to see economic events, such as inflation and taxes, as having strong effects on their work situation were more likely to be directive or negotiative. Managers who tended to see political, social, or legal issues as more important were more likely to be consultative or participative.

Higher Authority. If rules and regulations that are set by a higher authority or the central administration restrict subordinates’ decisions, then supervisors dominate the group and make the decisions (Hemphill, Seigel, & Westie, 1951). A higher authority can indirectly prevent subordinates’ participation in decisions by demanding immediate answers from supervisors and allowing the supervisors no time or opportunity to consult their subordinates. In addition, whether supervisors can be participative with their subordinates depends on the extent to which the higher authority requires the employees to be secretive about products, techniques, and business strategies. If people in the organization are supposed to know only “what they need to know,” employees cannot be consulted about some decisions because much of the information required to discuss and consider such decisions cannot be revealed to them (Tannenbaum & Massarik, 1950).

The number of hierarchical levels at which participation is encouraged by policy will increase the tendency of supervisors to be participative throughout the system. The acceptance and promotion of the participative ideology by the sponsors of the organization and its top management are particularly important (Marrow, Bowers, & Seashore, 1968).7 The efforts of chief executive officers (CEOs) at General Motors, National Intergroup, and W. L. Gore & Associates demonstrated that participative leadership could be increased throughout their systems through the transformational leadership of their CEOs. The CEOs articulated a corporate mission and philosophy to encourage participation. They worked to gain acceptance of the approach by other key top executives, then the acceptance of those at lower levels. Participation at all levels was encouraged by changing the corporate culture, developing trust at all levels, and building the necessary skills for effective participation. These actions of top management resulted in increased employee commitment, job satisfaction, and role clarity (Niehoff, Enz, & Grover, 1989). If top management is transformational, there will be more support for participation at lower levels, according to the survey of 485 upper-level managers by Collins and Ross (1989). Board and top management pressure to promote from within may also increase the need for and importance of delegation at all levels in the organization to develop personnel for higher-level positions. The effectiveness of such delegation depends on setting early expectations about the results that are desired.

L. B. Ward’s (1965) large-scale survey of top management in the United States suggested strongly that (at the time) the religious affiliation of the top managers in a firm affected the firm’s personnel policies. Leadership at lower levels was more likely to be participative when the top management was not restricted to members of one religious group. When the top management was restricted to one religion, participation was most likely in all-Jewish-led firms and least likely in all-Catholic-led firms. These findings need replication in the early twenty-first century.

Organizational Size. Blankenship and Miles (1968), McKenna (undated), and Wofford (1971) reported systematic trends between the size of the organization and the leadership style observed in it. On the whole, managers in larger firms exhibited more participation and less directiveness. However, a third variable may have been responsible, such as more education among managers of larger firms, differences in policies, and so forth.