In 1945, C. L. Shartle (1950b) launched the Ohio State Leadership Studies. He was influenced by his work on gathering occupational information to describe tasks, jobs, and occupational requirements in all echelons of industry, government, and the military. He focused on defining and classifying work done in each of the 30,000 occupations that had appeared originally in the 1939 Dictionary of Occupational Titles and in the U.S. Military Occupational Specialties. He and his colleagues now applied this background to the study of leaders. This was different from the emphasis in previous leadership research, which had sought to identify the traits of leaders. Reviews by Bird (1940), W. O. Jenkins (1947), and Stog-dill (1948) had concluded that the personality-traits approach had reached a dead-end, for several reasons: (1) attempts to select leaders in terms of traits had had little success; (2) numerous traits differentiated leaders from followers; (3) the traits demanded of a leader varied from one situation to another; and (4) the traits approach ignored the interaction between the leader and his or her group. Attention was shifted to what leaders did.

Needed were descriptions of individuals’ actions when they acted as leaders of groups or organizations. Hemp-hill (1949a) had already initiated such work at the University of Maryland. After joining the Ohio State Leadership Studies, Hemphill and his associates developed a list of approximately 1,800 statements that described different aspects of the behavior of leaders, such as “He insists on meeting deadlines.” Most statements were assigned to several subscales. However, staff members agreed on 150 statements that could each be assigned to only one subscale. These statements were used to develop the first form of the Leader Behavior Description Questionnaire, or LBDQ (Hemphill, 1950a; Hemp-hill & Coons, 1957). On the LBDQ, respondents rated a leader by using one of five alternatives to indicate the fre-quency or amount of a particular behavior that was descriptive of the leader being rated. Responses to items were simply scored and added in combinations to form subscales on the basis of the similarity of their content. These subscale totals were then intercorrelated and factor-analyzed (Fleishman, 1951, 1953c; Halpin & Winer, 1957). “Consideration” and “initiation of structure” were primary factors identified by Halpin and Winer (1957) with regard to Air Force officers, and by Fleishman (1951, 1953c, 1957) with regard to industrial supervisors. They emerged in successive factor studies (Fleishman, 1973) as the two most prominent factors that described leaders according to questionnaires completed by themselves and others.

This first factor describes the extent to which a leader exhibits concern for the welfare of the other members of the group. The considerate leader expresses appreciation for good work, stresses the importance of job satisfaction, maintains and strengthens the self-esteem of subordinates by treating them as equals, makes special efforts to help subordinates feel at ease, is easy to approach, puts subordinates’ suggestions into operation, and obtains subordinates’ approval on important matters before going ahead. Considerate leaders provide support that is oriented toward relationships, friendship, mutual trust, and interpersonal warmth. Participation and the maintenance of the group accompany such support (Atwater, 1988). In contrast, the inconsiderate leader criticizes subordinates in public, treats them without considering their feelings, threatens their security, and refuses to accept their suggestions or to explain his or her actions.

This second factor shows the extent to which a leader initiates activity in the group, organizes it, and defines the way work is to be done. Initiation of structure includes such leadership behavior as insisting on maintaining standards and meeting deadlines and deciding in detail what will be done and how it should be done. Clear channels of communication and clear patterns of work organization are established. Orientation is toward the task. The leader acts directively without consulting the group. Particularly relevant are defining and structuring the leader’s own role and the roles of subordinates in attaining goals. The leader whose factor score in initiating structure is low is described as hesitant about taking initiatives in the group. He or she fails to take necessary actions, makes suggestions only when members ask for it, and lets members do the work the way they think best.

The LBDQ, consisting of 40 statements, was designed to measure the two factors of consideration and initiation (Hemphill & Coons, 1957). An industrial version, the Supervisory Behavior Description Questionnaire (SBDQ), followed (Fleishman, 1972), as did LBDQ—Form XII, hereafter referred to as LBDQ-XII (Stogdill, 1963a). Each of the LBDQs had instructions such as these:

The following … are items that may be used to describe the behavior of your leader or supervisor. Each item describes a specific kind of behavior, but does not ask you to judge whether the behavior is desirable or undesirable. This is not a test of ability. It simply asks you to describe, as accurately as you can, the behavior of your supervisor or leader. Group refers to an organization or to a department, division, or other unit of organization that is supervised by the person being described. … Members refer to all the people in the unit of organization that is supervised by the person being described.

THINK about how frequently the leader engages in the behavior described by the item.

DECIDE whether he (A) always, (B) often, (C) occasionally, (D) seldom, or (E) never acts as described by the item.

Typical items were: “He lets group members know what is expected of them.” “He is friendly and approachable.”

The intentions of the developers of the LBDQs and the SBDQ, particularly with regard to initiating structure, differed somewhat in the construction of the different versions. The LBDQ contained a subset of 15 items that asked subordinates to describe the actual structuring behavior of their leader. This structuring behavior was the leader’s behavior in delineating relationships with subordinates, in establishing well-defined patterns of communication, and in detailing ways to get a job done (Halpin, 1957b). The Supervisory Behavior Description Questionnaire (SBDQ) consisted of 20 items that included asking subordinates about their leader’s actual structuring behavior. Initiating structure, as measured by the SBDQ, was intended to reflect the extent to which the leader organizes and defines interactions among group members, establishes ways to get the job done, schedules, criticizes, and so on (Fleishman, 1972). The SBDQ items for the factor of initiation of structure included a wider variety of structuring behaviors drawn from the loadings on this factor. Several were close to Misumi’s (1985) Production Pressure. Items on the LBDQ came mostly from original conceptualizations about communication and organization (Schriesheim, House, & Kerr, 1976). The revised LBDQ-XII had 10 items that measured initiation of structure in terms of the actions of leaders who clearly define their own role and let followers know what is expected of them (Stogdill, 1963a).

As noted, ratings of the consideration and initiation of structure by leaders are highly stable and consistent from one situation to another (Taylor, Crook, & Dropkin, 1961; and Philipsen, 1965a). According to Schriesheim and Kerr’s (1974) review of the psychometric properties of the LBDQ and SBDQ, the descriptions maintain the high internal consistency that was the basis for their construction. That is, items on the “consideration behavior” in each instrument correlate highly with all the other consideration items and do not correlate with items on the “initiation behavior” factor. Conversely, items on the “initiating structure” factor are independent of the “consideration” items and are highly intercorrelated with all the other structuring items. Using a sample of 308 public utilities employees, Schriesheim (1979a) found that consideration and initiation were so psychometrically robust that it did not make much difference in a supervisor’s scores whether one asked a subordinate to describe how the supervisor behaved toward him or her personally (the dyadic approach) or how the supervisor behaved toward the whole work group (the standard approach).

Nonetheless, the factor scores left a lot to be desired. They suffered from halo effects and were plagued by a variety of other response errors, such as leniency and social desirability, as well as a response set to agree rather than to disagree (Schriesheim, Kinicki, & Schriesheim, 1979). It was not known whether they were valid measures of true consideration and initiation of structure. Most important, as research with the original LBDQ and SBDQ instruments continued, it became apparent that some of what leaders do had been missed. A great deal of the behavior of leaders was being lost in the emphasis on just two factors to account for all the common variance among items describing this behavior. Therefore, for LBDQ-XII, various additional factored scales were constructed, possibly lacking complete independence from structuring and consideration, yet likely to include much of the missing information of consequence.

Comparison of the Three Forms. All three versions—LBDQ, SBDQ, and LBDQ-Form XII—have been used extensively, and each has been subjected to additional factor analyses (Bish & Schriesheim, 1974; Szilagyi & Sims, 1974a; Tscheulin, 1973). A direct comparison of all three became possible after a survey and factor-analytic study of 242 hourly employees by Schriesheim and Stogdill (1975). This comparison study was necessary, since, as Korman (1966) and others had noted, the content of the scales varied, which caused differences in outcomes. The original LBDQ and particularly the SBDQ contained several items such as “Needles subordinates for greater effort” and “Prods subordinates for production” that measured punitive, arbitrary, coercive, and dominating behaviors and that affected the scores for initiation of structure. The LBDQ-XII was considered to be most nearly free of such autocratic items (Schriesheim & Kerr, 1974). As has usually been found, internal consistency reliabilities were high for scores on both factors that were derived from the items drawn according to their use in the LBDQ, SBDQ, or LBDQ-XII. For consideration and initiation, reliabilities were .93 and .81 for the LBDQ, .81 and .68 for the SBDQ, and .90 and .78 for the LBDQ-XII. (The reliability of .68 for initiation of structure on the SBDQ was raised to .78 when three SBDQ punitive items were removed from the scoring of the scale.) The primary factors that were extracted indicated that all three versions contained some degree of arbitrary punitive performance (“The leader demands more than we can do”). But, as expected, the pattern was most marked in the SBDQ. A hierarchical factor analysis disclosed the existence of a higher-order factor of rater bias, which appeared in all three questionnaires.

According to Schriesheim and Kerr, the items loading highest on the SBDQ in initiating structure were: “He insists that he be informed on decisions made by people under him” (.60), “He insists that people under him follow standard ways of doing things in every detail” (.65), and “He stresses being ahead of competing work groups” (.64). In fact, Atwater (1988) found that two items—“Demands a great deal from his workers” and “Pushes his workers to work harder”—correlated highest with the SBDQ factor she obtained and labeled demanding behavior. But on the LBDQ, the two items loading highest on initiating structure were: “He maintains definite standards of performance” (.59) and “He lets members know what is expected of them” (.54).

Matters further were complicated because many researchers deleted items or modified the wording of items for use in a particular study, as Podsakoff and Schriesheim (1985) found in their review of studies that used the LBDQ. Also, many researchers failed to specify which version of the LBDQ they had used or how they had modified the scales (Hunt, Osborn, & Schriesheim, 1978).

The items ask how the leader acts toward the work group rather than toward specific individuals. Critics, such as Graen and Schiemann (1978), assume that there are large variations in the leader’s behavior toward different individual members of a work group, and therefore that the wording of items should allow for this. Individual differences among raters also underlie the ratings. Although WABA analysis could handle this, it was not introduced until 1984 (see Chapter 16). The previously cited findings of Schriesheim (1979a) suggested, however, that the matter may be overblown. D. M. Lee (1976) asked 80 students to judge the initiation and consideration of their En glish professors over an eight-week period. The results indicated that the individual students differed widely in the cues they used as the basis of their ratings of the same professors. The questionnaires fail to weight the timing, appropriateness, importance, and specificity or generality of responses. They may assess the circumstantial requirements of the job, rather than the leader as a person with discretionary opportunities to behave in the manner indicated.

Leniency Effects. Seeman (1957) reported that the LBDQ scales suffered from halo effects. Even making items more detailed was of no help in reducing the halo. Schriesheim, Kinicki, and Schriesheim (1979) completed five studies of the extent to which consideration and initiation of structure were biased by leniency effects. They inferred from the results that leniency response bias—the tendency to describe others in favorable but probably untrue terms—did not particularly affect descriptions of initiation of structure. But even though consideration and leniency are conceptually distinct, they concluded that (1) consideration items were not socially neutral and were susceptible to leniency, (2) consideration reflected an underlying leniency factor when applied in a field setting, and (3) leniency explained much or most of the variance in consideration. Leniency may explain why consideration tends to correlate higher with other evaluative variables than does initiation of structure (Fleishman, 1973).

Implicit Theories. D. J. Schneider (1973), among others, suggested that respondents express their own implicit theories about and stereotypes of leaders and leaders’ behavior, rather than the behavior of the specific leader they are supposed to be describing with the LBDQ. That is, respondents describe their idealized prototype of a leader, rather than the actual leader they should be describing (Rush, Thomas, & Lord, 1977). Eden and Leviatan (1975) noted that leader-behavior descriptions of a fictitious manager using the Survey of Organizations resulted in a factor structure highly similar to that obtained from descriptions of real managers reported by Taylor and Bowers (1972).1 Rush, Thomas, and Lord (1977) found a high degree of congruence between factor structures obtained from descriptions of a fictitious supervisor using LBDQ-XII and descriptions of real leaders from a field study by Schriesheim and Stogdill (1975). In both studies, the authors concluded that since practically identical factor structures emerged for fictitious and specific real leaders, the actual behavior of a leader is relatively unimportant for behavioral descriptions, because descriptions are based mainly on implicit theories or stereotypes.

One might suggest that this tendency to project or to use implicit theories tells more about the subordinate than about the leader. But the tendency is a consequence of ambiguity and of a lack of specific information about the leader to be rated. Schriesheim and DeNisi (1978) studied 110 bank employees and 205 workers in a manufacturing plant who used the LBDQ-XII to describe supervisors in general after first describing their own supervisors. The investigators, as expected, found comparable factors emerging from the general and specific descriptions when each was analyzed separately. However, separate real and imaginary factors emerged when the combined data were subjected to an analysis that provided an opportunity for statistical differentiation. As before, in both real and imaginary descriptions, initiation of structure and consideration was correlated above .50, with reliabilities ranging from .84 to .87.

Schriesheim and DeNisi discovered that although satisfaction with one’s real supervisor correlated between .51 and .75 with descriptions of the actual consideration and initiation of the real supervisors, it correlated only .23 and –.03 with scores for initiating structure and consideration for the stereotypes of supervisors. This was a particularly important finding.

Subsequent experimentation by Schriesheim and DeNisi (1978) with 360 undergraduates strongly supported the contention that as more specific information became available to them, the respondents’ LBDQ responses became more accurate and were less likely to depend on implicit theories. These results are consistent with those of Bass, Valenzi, Farrow, and Solomon (1975), who found that subordinates describing the same real leader were in much more significant agreement with each other than with subordinates who described other leaders.

Self-Ratings Unrelated to Subordinates’ Ratings. As many researchers reported for self-rated directive versus participative leadership, for autocratic versus democratic leadership, and for task-versus relations-oriented leadership,2 little relation was obtained between leaders’ self-descriptions of their own initiation and consideration and their subordinates’ descriptions on the LBDQ. Similarly, there was only a weak relation between what leaders say they should do, according to scores on the Leadership Opinion Questionnaire, and what they actually do, according to their subordinates’ descriptions of them on the LBDQ (Schriesheim & Kerr, 1974).

Theoretically, given the original orthogonal factor structure, consideration and initiation of structure should be independent, but this is not the case. Schriesheim, House, and Kerr (1976) reexamined Weissenberg and Kavanagh’s (1972) review of the data, along with work published subsequently. In 11 of 13 studies using the LBDQ, a positive correlation was reported. The median correlation for the 13 analyses was .45. Likewise, for the LBDQ-XII for 10 studies, the median correlation was .52 between consideration and initiation of structure. The correlation was even higher in situations where job pressure was strong. In addition, the correlations between consideration and initiation were positive both when group-by-group values were correlated and when the scores for individuals within the groups were correlated (Katerberg & Hom, 1981). Of the 16 studies that used the SBDQ, which includes some “autocratic” items, 11 studies yielded some significant negative correlations between consideration and initiation. However, the median correlation was –.05. Without the punitive items, consideration and initiation on the LBDQ tend to correlate more positively. A comprehensive review (Fleishman, 1989a), which included 32 studies with the SBDQ, found a median correlation of –.02 between the score for consideration and the score for structure.

Oldham (1976), among others, developed alternative and additional scales to provide a more detailed profile of leader behavior. The scales included behaviors such as these: personally rewarding, personally punishing, setting goals, designing feedback systems, placing personnel, and designing job systems. These scales were higher in relation to effectiveness than were measures of consideration and the initiation of structure. Seltzer and Bass (1987) found that the transformational leadership factors of charisma, individualized consideration, and intellectual stimulation added substantially to the effects of consideration on subordinates’ satisfaction and effectiveness. Seltzer and Bass conceived of consideration and initiation of structure as primarily transactional.

Halpin and Croft (1962) also were not convinced that the behavior of leaders could be adequately described with just two factors. Using items containing additional content about school principals, as well as items from the LBDQ, they extracted four factors to account for the common variance in the obtained descriptions of school principals’ behavior: (1) aloofness, formality, and social distance; (2) Production emphasis—pushing for results; (3) Thrust—personal hard work and task structure; and (4) Consideration—concern for the comfort and welfare of followers. These factored scales for describing the behavior of school principals were supplemented by the following four scales used to describe the behavior of teachers: (1) Disengagement—clique formation, withdrawal, (2) Hindrance—frustration from routine and overwork, (3) Esprit—high morale, enthusiasm, and (4) Intimacy, mutual liking, and teamwork.

When Halpin and Croft classified 71 schools into six categories according to climate, they found that an open school climate was associated with the esprit of teachers under a principal who was high in thrust. An autonomous climate produced intimacy in teachers under an aloof principal. A controlled climate resulted in hindrance in teachers under a principal who pushed for production. A familiar climate was associated with the disengagement of teachers under a considerate principal. A climate with potential but with the disengagement of teachers resulted in a principal who exhibited consideration, along with an emphasis on production. A closed climate, also with the disengagement of teachers, was associated with an aloof principal. These results yielded considerably more insight into the dynamic interplay among the climate of schools, the behavior of leaders, and the response of teachers than could be produced by the use of just two factors to describe the behavior of leaders.

The most direct expansion from consideration and initiation of structure to a broader array of leader-behavior dimensions was the development of LBDQ-XII.

On the basis of a theoretical analysis of the differentiation of roles in groups, Stogdill (1959) proposed 10 additional patterns of behavior involved in leadership, conceptually independent of consideration and initiation of structure, to be included in the LBDQ-XII along with consideration and initiation of structure. These patterns were: (1) Representation—speaks and acts as the representative of the group; (2) Reconciliation—reconciles conflicting organizational demands and reduces disorder in the system; (3) Tolerance of uncertainty—is able to tolerate uncertainty and postponement without anxiety or upset; (4) Persuasiveness—uses persuasion and argument effectively; exhibits strong convictions; (5) Tolerance of freedom—allows followers scope for initiative, decisions, and action; (6) Role retention—actively exercises the leadership role, rather than surrendering leadership to others; (7) “Production emphasis”—applies pressure for productive output; (8) Predictive accuracy—exhibits foresight and the ability to predict outcomes accurately; (9) Integration—maintains a close-knit or-ganization and resolves intermember conflicts; and (10) Influence with supervisors—maintains cordial relations with superiors; has influence with them; strives for higher status. Subsequently, these patterns became the 10 scored factors of LBDQ-XII. The conception of the persuasiveness pattern anticipated the more recent focus on the measurement of charismatic and inspirational leadership.

Interdescriber Agreement. In a study of a governmental organization by Day (1968), high-ranking administrators were each described by two male and two female subordinates. Correlations were computed to determine the extent to which pairs of subordinates agreed with each other in their descriptions of their immediate superiors. The greatest agreement was shown by pairs of female subordinates describing their female superiors. Their correlations ranged from .39 (integration) to .73 (retention of the leadership role). The least agreement was shown by pairs of male subordinates describing their female superiors. Their correlations ranged from –.02 (tolerance of freedom) to .53 (retention of the leadership role). Pairs of female subordinates tended to exhibit higher degrees of agreement than male subordinates in descriptions of male superiors on 8 of the 12 scales. The four exceptions occurred for representation, production emphasis, integration, and influence with superiors. The scales with the highest degrees of interdescriber agreement across groups of raters, male or female, were demand reconciliation, tolerance of uncertainty, persuasiveness, role retention, predictive accuracy, and influence with superiors. The scales with the lowest degrees of agreement across samples were representation, tolerance of freedom, and integration.

Divergent Validities. To test the divergent validities of several scales of the LBDQ-XII, Stogdill (1969), with the assistance of a playwright, wrote a scenario for each of six scales (consideration, structure, representation, tolerance of freedom, production emphasis, and superior orientation). The items in each scale were used as a basis for writing the scenario for that pattern of behavior. Experienced actors played the roles of supervisor and workers. Each role was played by two actors, and each actor played two different roles. Motion pictures were made of the performances. Observers used LBDQ-XII to describe the “supervisor’s” behavior. No significant differences were found between two actors playing the same role. Still, the actors playing a given role were described as behaving significantly more like that role than the other roles. Stogdill concluded that the scales measured what they purported to measure.

Factor Validation of LBDQ-XII.3 Data collected by Stogdill, Goode, and Day (1963a, 1963b, 1964, 1965) used nine of the LBDQ-XII scales to obtain descriptions of the leadership behavior of U.S. senators, corporation presidents, presidents of international labor unions, and presidents of colleges and universities. For leaders in each setting, the scores for the scales were intercorrelated and factor-analyzed. In general, the results suggested that each factor was strongly dominated by a single appropriate scale. For example, in all four analyses the representation factor emerged with only the representation scale correlated highly with it. The representation scale correlated, respectively, with the representation factor, .80, .94, .92, and .92, in the four locales. Similarly, the role retention subscale correlated only with its own role retention factor, .89, .93, .81, and .92. However, production emphasis tended to load highly on initiation of structuring as well as on production emphasis.

“Reconciliation of conflicting demands” failed to emerge as a factor differentiating college presidents, presumably because they all were described similarly highly in this behavior. “Orientation to superiors,” of course, did not fit with the role of senators; nor did union presidents differ from each other in orientation to a higher authority. The differences in predictive accuracy generated the factor “predictive accuracy” for only the corporate and union leaders, not the senators or college presidents.

Slightly different results emerged when all the items of the LBDQ-Form XII were intercorrelated and factor-analyzed for three additional locales. Eight factors emerged: (1) General persuasive leadership; (2) tolerance of uncertainty; (3) tolerance of followers’ freedom of action; (4) representation of the group; (5) influence with superiors; (6) production emphasis; (7) structuring expectations; (8) retention of the leadership role. In addition, two distinct factors of consideration were extracted.

The most numerous and most highly loaded items on general persuasive leadership, aside from measures of persuasiveness, were scales with items about the reconciliation of conflicting demands, structuring expectations, retention of the leadership role, influence with superiors, consideration, and production emphasis. These items represented the followers’ general impression of the leaders. In fulfilling these functions, leaders were seen as considerate of their followers’ welfare. Each of the remaining factors tended to be composed of items from a single scale, but some contained stray items from other scales. Consideration broke down into two separate factors, to be discussed later in connection with J. A. Miller’s (1973b) hierarchical factor analysis.

The first nine factors showed similar loadings for senators, union leaders and college presidents. But “retention of the leadership role” appeared as a separate factor only in the ratings of the state senators. All scales except those dealing with tolerance of uncertainty, tolerance of freedom, and representation contributed some items to the general factor. However, all scales except persuasiveness and the reconciliation of conflicting demands emerged in separate factors differentiated from each other. These findings indicated that the behavior of leaders is indeed complex in structure and that followers are able to differentiate among different aspects of behavior. The general persuasion factor provided valuable additional insight into the nature of leadership, strongly suggesting that this general factor may be particularly useful given what was said in Chapter 6 about its opposite, laissez-faire leadership.

Initiation and Consideration as Higher-Order Dimensions. A. F. Brown (1967) used the LBDQ-XII to obtain scores on each of the 12 factors for 170 principals described by 1,551 teachers in Canadian schools. He found that two higher-order factors accounted for 76% of the total factor variance for the 12 primary factors. When the loadings for the two factors were plotted against each other, “production emphasis,” “structuring expectations,” and “representation of the group” clustered about an axis of “initiation of structure” and “tolerance of uncertainty.” “Tolerance of freedom” and “consideration” clustered about an axis of “consideration.” The loadings for the remaining factors fell between the clusters at the extremes of these two orthogonal axes. A plot of factor loadings obtained for descriptions of university presidents on the LBDQ-XII (Stogdill, Goode, & Day, 1965) produced similar results. “Representation,” “structuring expectations,” “emphasis,” and “persuasiveness” clustered around the first axis and “freedom,” “uncertainty,” and “consideration” clustered around the second axis. Marder (1960) obtained a somewhat different pattern of loadings when military rather than educational leaders were studied. The data consisted of 235 descriptions of U.S. Army officers by enlisted men. “Productivity emphasis” and “initiation of structure” centered on one axis and “tolerance for freedom” and “tolerance for uncertainty” clustered around the other. “Consideration” was displaced toward the central cluster of items.

There are different schools of thought regarding the use of factor analysis. One school maintains that as much of the total factor variance as possible should be explained in terms of a general factor. Another school holds that rotational procedures, such as the varimax that reduces the magnitude of the general factor, are legitimate. The former school, while admitting that systems of events in the real world may involve a variety of factors, maintains that human perception contains a large element of bias and halo that should be removed in the general factor before any attempt to determine the structure of measurements representing the real world. The second school argues that the apparent halo in the general factor has its equivalent in the opacity of the real world and that the purpose of research is to reduce this opacity by making full use of all the structure differentiated by human perception. The structure that is perceived should not be permitted to remain hidden in the general factor.

If one prefers a two-factor theory of leadership behavior, initiation of structure, production emphasis, or persuasiveness can define one of the factors; consideration, tolerance of freedom, and tolerance of uncertainty can define the other. A two-factor solution, which leaves a considerable amount of the total variance unexplained, can always be obtained in the analyses of descriptions of leaders’ behavior. However, a multifactor solution should not be rejected until its consequences have been thoroughly explored and it has been proved untenable. Furthermore, the dilemma can be reconciled, as J. A. Miller (1973b) and Schriesheim and Stogdill (1975) showed, by recourse to hierarchical factor analysis. The former used rotation and differentiation; the latter, the general evaluative bias factor. Finally, the positive association routinely found (as noted earlier) between consideration and initiation of structure, as measured by LBDQ-XII, suggests that a single, general factor solution may be warranted. Nevertheless, with reference to the contents of the LBDQs, the two-factor framework for describing leadership behavior—consideration and the initiation of structure—emerges consistently from factor analyses when no additional constraints are placed on the analyses, such as first requiring the isolation of a general factor that, no doubt, has strong connections with the respondents’ prototypes of leaders.

Consideration and initiating structure can be finely factored in a number of ways by adding detailed behaviors, other than those found on the LBDQ-XII, and pursuing reconceptualizations about consideration and initiation. As was just noted, Stogdill (1963a) added new content dealing with different domains of leadership behavior to obtain the 10 additional scales for LBDQ-XII. More detail about initiation and consideration can also intensify the analysis of the basic content of initiation and consideration and related measures. Yukl (1971) demonstrated the feasibility of a three-factor approach (consideration, initiation of structure, and centralization of decisions). Saris (1969) offered “responsibility reference” and Karmel (1978) offered “active engagement” as a third factor. Another three-factor approach—initiating structure, participation, and decision making—was pursued by R. H. Johnson (1973). Wofford (1971) expanded the framework of leadership behavior to five factors: (1) group achievement and order, (2) personal enhancement, (3) personal interaction, (4) dynamic achievement, and (5) security and maintenance.

Using several thousand members of a nationwide business fraternity, who described their leaders on both a new instrument (FFTQ) and the comparable scales of the LBDQ-XII, Yukl and Hunt (1976) demonstrated some degree of communality between factors and scales purporting to deal with similar dimensions; yet overall, unfortunately, the scales were not equivalent.

Hierarchical Factor Analysis. Because of earlier reported findings that the LBDQ and supposedly similar instruments were not equivalent,4 J. A. Miller (1973b) assembled 160 items from nine frequently cited standard instruments used in published research concerning leadership behavior described in this and preceding chapters. The objective was to gain a better understanding of similarities and differences in the measures of consideration and initiation of structure. The original pool included items from the following: the LBDQ (Halpin & Winer, 1957), Survey of Organizations (Taylor & Bowers, 1972), interaction process analysis (Bales, 1950), the Job Descriptive Index (Smith, Kendall, & Hulin, 1969), the Orientation Inventory (Bass, 1963), scale anchors use to describe a “continuum of leadership behavior” (Tannenbaum & Schmidt, 1958), six categorical statements describing a continuum of decision-making styles (Vroom & Yetton, 1974), five bases of social power (French & Raven, 1959), and adjectives used by Fiedler (1967a) for measuring the least preferred coworker (LPC). Miller drew 73 nonduplicative items from the pool of 160 that were most specific and that were descriptive, rather than evaluative, and then collected data from 200 respondents from 10 organizations, including social agencies, industrial firms, and military organizations.

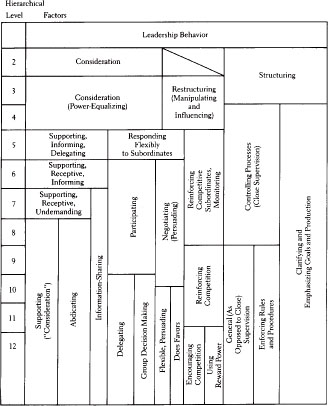

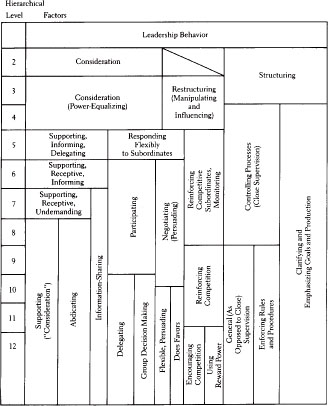

The first step in the hierarchical solution was a factor analysis stipulating a two-factor solution. Then the process was repeated with a stipulated three-factor solution, then a four-factor solution, and so on (Zavala, 1971). Miller then successively rotated all 12 principal components, using the varimax (orthogonal) rotation algorithm. At each level, interpretable solutions reflecting familiar leader-behavior factors emerged. The two-factor solution clearly paralleled consideration and initiation of structure. Other clearly identifiable factors that had been discovered in previous research emerged when an additional factor in each successive level of analysis was called for. Production, goal emphasis, and close supervision split apart as subfactors of initiation of structure in the four-factor solution. Participation emerged at level 6, information sharing at level 7, and supporting (the narrowly interpersonal interpretation of consideration) at level 8. Enforcing rules and procedures emerged as a subfactor of close supervision at level 9, and so forth. The emergence of the factors and the hierarchical linkages are shown in Figure 20.1. Here, the two-factor solution appears at level 2, the three factor solution at level 3, and so on. A subsequent higher-order factor analysis, based on an oblique solution, obtained a higher-order factor of consideration and another of initiation of structure.

It can be seen from Figure 20.1 that consideration includes behavior ordinarily regarded as concern for the welfare of subordinates, such as supportive behavior and sharing information, but it also appears linked to participative group decision making, to abdication, and to delegation.

Hemphill, Seigel, and Westie (1951) developed and Halpin (1957c) revised an ideal form of the LBDQ that asks respondents to describe how their leader should behave—not, as on the LBDQ, how they see their leader actually behaving. For example, in a study of 50 principals, J. E. Hunt (1968) found that teachers described principals as lower in actual consideration and structure than the teachers believed to be ideal. Such discrepancies between subordinates’ descriptions of what their leaders should do and what the leaders actually do are more highly related to various measures of group performance than are desired or observed leadership behavior alone. Such discrepancies are measures of dissatisfaction with the leaders’ performance and, as a consequence, are more strongly related to various group outcomes.

Stogdill, Scott, and Jaynes (1956) studied a large military research organization in which executives and their subordinates described themselves—and subordinates described their superiors—on the real and ideal forms of the LBDQ. When superiors were really high in initiation of structure, according to their subordinates, the subordinates described these superiors on the ideal forms as having less responsibility than they should, as delegating more than they should, and as devoting more time than they should to teaching. When superiors were really high in consideration on the LBDQ, according to their subordinates, the subordinates said on the ideal form that they expected the superiors to assume more responsibility than they perceived the superiors to assume, devote more time than necessary to scheduling, and devote less time to teaching and mathematical computation. When superiors were really high in initiating structure, as seen by their subordinates, the superiors perceived themselves to be devoting more time than they should to evaluation, consulting peers, and teaching and not enough time to professional consultation. When superiors were described as actually high in consideration, subordinates perceived themselves as having more responsibility than they should. The subordinates also reported that the superiors ought to devote more time to coordination, professional consultation, and writing reports but less time to preparing charts. The leaders’ initiation of structure was more highly related to subordinates’ actual work performance. The leaders’ consideration, by contrast, was more highly related to subordinates’ idealization of their own work performance.

Figure 20.1 The Hierarchical Structure of Leadership Behaviors

SOURCE: J. A. Miller (1973b).

In a similar type of study, Bledsoe, Brown, and Dalton (1980) showed that the actual behavior of school business managers, as described by 132 school superintendents, principals, and school board members, tended to differ considerably from the ideal for initiation and consideration Board members tended to describe the ideal school business managers as actually more considerate than did the school principals. Ogbuehi (1981) surveyed 270 Nigerian managers’ and administrators’ self-descriptions of their ideal behavior using the LBDQ-XII. The results were consistent with their superiors’ judgments of their effectiveness.

Vecchio and Boatwright (2002) examined the preferences of 1,137 employees in three organizations regarding leaders’ structuring and consideration. More highly educated and tenured employees preferred less structuring in their leaders; women preferred more consideration.

Fleishman’s (1989a) LOQ differs from the ideal forms of Hemphill, Seigel, and Westie (1951). It asks the leaders themselves to choose the alternative that most nearly expresses their opinion on how frequently they should do what is described by each item on the questionnaire, and what they, as a supervisor or manager, sincerely believe to be the desirable way to act. The LOQ also differs from the ideal form in that the LOQ scale for initiation of structure contains several items that Stogdill, Goode, and Day (1962) later found to measure production emphasis. Production emphasis correlates with initiating structure but is not identical with it.

Following a review, Schriesheim and Kerr (1974) concluded that the test-retest reliability of the LOQ had been adequately demonstrated over a one-to three-month period. Internal consistency reliabilities are also high (Fleishman, 1960, 1989b). In 60 studies, the median correlation between consideration and structure on the LOQ was –.06, with 57 of these correlations below .19 and only 9 above .20 found significant (Fleishman, 1989). According to a review of 20 LOQ validation studies (Fleishman, 1989b), a number of studies showed that supervisors higher in both consideration and structure were more likely to be higher on criteria of effectiveness, such as performance ratings, staff satisfaction, low stress, and less burnout of subordinates.

The internal consistency and test-retest reliability of the various scales of leader-behavior descriptions may be satisfactory, but to understand their effects, differences in content make it mandatory to distinguish whether the measures were based on the LBDQ, SBDQ, LOQ, or LBDQ-XII. This is essential in reviewing the antecedent conditions that influence the extent to which a particular behavior is exhibited and concurrent conditions are associated with such behavior.

Interpreting Concurrent Analyses. Most of the available research consists of surveys in which leadership behavior and other variables in the leader or the situation were measured concurrently. However, it seems reasonable to infer that a relatively invariant attribute such as the intelligence of the leader is an antecedent to the leader’s display of consideration or initiation as rated by their colleagues. The national origin of the leader’s organization is antecedent to the leader’s behavior; but the average leader’s behavior in the organization cannot affect its origin. Likewise, the leader’s educational level is obviously antecedent to his or her behavior, but that behavior cannot cause a change in the leader’s educational level. Similar inferences can be made about situational influences on the leader’s behavior with less confidence, because the leader often can influence the situation, just as the situation is influencing the leader. If an association is found between company policy and the behavior of first-line supervisors, it seems reasonable to infer that the policy has influenced the supervisors, but the policy may also reflect the continuing behavior of the supervisors and may be a reaction to it. If an association is found between the leader’s behavior and conflict in the work group, it is likely that the leader is a source of the conflict; but the continuing conflict is likely to be influencing the leader’s behavior as well.

Suppose that a positive association is found between a leader’s consideration and an absence of conflict within a group. The most plausible hypothesis is probably that the leader’s behavior contributes to the absence of conflict; but the harmony within the group makes it possible for the leader to be more considerate. Therefore, in examining concurrent results, the reader will have to decide what meaning to draw from the reported associations. Such criteria of effectiveness as the subordinates’ productivity, satisfaction, cohesion, and role clarity can be seen to be a consequence of the leader’s behavior, yet they may influence the leader’s behavior as well.

In a study of ROTC cadets, Fleishman (1957a) found that their attitudes toward consideration and initiation on the LOQ were not related to their intelligence or to their level of aspiration. But among school principals described by 726 teachers, Rooker (1968) found that principals with a strong need for achievement were described as high in tolerance of freedom and reconciliation of conflicting demands on the LBDQ-XII. However, Tronc and Enns (1969) found that promotion-oriented executives tended to emphasize initiation of structure over consideration to a greater degree than executives who were less highly oriented toward promotion. And Lindemuth (1969) reported that for college deans, consideration was related to their scholarship, propriety, and practicality.

Experience and sex have been correlated with LBDQ scores. For 124 managers of state rehabilitation agencies who were described by their 118 subordinates, Latta and Emener (1983) found that initiation of structure on the LBDQ increased directly with experience. Serafini and Pearson (1984) reported that at a university initiation of structure was higher only among the 208 male nonadministrative supervisors and managers. For the female leaders, consideration was higher. This is consistent with the expectation that females are likely to be more relations-oriented.

Personality, Values, and Interests. Although one might expect authoritarianism to coincide with initiation of structure, this does not appear to occur. For example, Fleishman (1957a) observed that the leader’s endorsement of authoritarian attitudes was negatively related to initiation of structure on the LOQ, but it was unrelated to consideration. Stanton (1960) also found no relation between consideration and authoritarianism. Flocco (1969), who studied 1,200 school administrators, showed that consideration and initiation of structure, as indicated by subordinates’ responses to the LBDQ, were unrelated to the administrators’ scores for dogmatism on a personality test.

Fleishman (1957b) also found that supervisors who favored consideration tended to have high scores on a personality scale of benevolence, whereas those favoring initiation of structure were more meticulous and sociable. Also, Fleishman and Peters (1962) obtained results for supervisors indicating that the trait of independence was correlated negatively with both initiation of structure and consideration, and the trait of benevolence was positively correlated with initiation of structure and consideration. Consideration was more highly related than initiation to ratings of social adjustment and charm (Marks & Jenkins, 1965). Litzinger (1965) reported that managers who favored consideration tended to value support (being treated with understanding and encouragement), whereas those who favored initiation of structure tended to place a low value on independence. Atwater and White (1985) reported that certain personal characteristics significantly correlated with demanding (SBDQ structuring) behavior by first-line supervisors; these included being inflexible, aggressive, uncooperative, harsh, strict, tense, ambitious, and unforgiving.

Newport (1962) studied 48 cadet flight leaders, each described on the LBDQ by seven flight members. Leaders who were rated high in both consideration and initiation of structure differed from those who were rated weak in desire for individual freedom of expression, resistance to social pressure, desire for power, cooperativeness, and aggressive attitudes.

In line with expectations, R. M. Anderson (1964) found, in a study of nursing supervisors, that those who preferred nursing-care activities were described as high in consideration but those who preferred coordinating activities were described as high in initiation. According to analyses by Stromberg (1967), school principals with emergent value systems were perceived by teachers as high in initiating structure, whereas those with traditional value orientations were perceived as high in consideration. Durand and Nord (1976) noted that 45 managers in a midwestern textile and plastics firm were rated by their subordinates as higher in both consideration and initiation of structure if the managers were externally, rather than internally, controlled—that is, if the managers believed that personal outcomes were due to forces outside their control rather than to their own actions.

Fleishman and Salter (1963) measured empathy in terms of supervisors’ ability to guess how their subordinates would fill out a self-description questionnaire. They found that empathy was significantly related to employees’ descriptions of their supervisors’ consideration but not their initiation of structure. L. V. Gordon (1963a) showed that personal ascendancy was positively related to initiating structure but negatively related to consideration. Neither score was related to responsibility or emotional stability, although sociability was correlated with initiating structure (but not with consideration). Rowland and Scott (1968) failed to find any relation between consideration on the LOQ and the social sensitivity of supervisors. Pierson (1984) failed to find any significant relations between the Myers-Briggs Indicator of perceptual and judgmental tendencies and consideration or initiation. Numerous other investigators5 also failed to find LBDQ and LOQ scores related to any of the personality measures they used. Situational factors, to be discussed later, may override or eliminate the effects of personality on initiation and consideration.

Cognitive Complexity. A number of studies of the influence of cognitive complexity on leadership behavior have obtained positive findings, particularly when the additional LBDQ-Form XII factors have been used. W. R. Kelley (1968) reported that school superintendents who were high in cognitive complexity were also described as high in predictive accuracy and in reconciliation of conflicting demands. Streufert, Streufert, and Castore (1968) found significant differences between emergent leaders whose scores on perceptual complexity varied in a negotiations game. Leaders who were lower in cognitive complexity scored higher on initiating structure, production emphasis, and reconciliation. Leaders who were higher in cognitive complexity scored higher on tolerance of uncertainty, retaining the leadership role, consideration, and predictive accuracy. Results obtained by Weissenberg and Gruenfeld (1966) indicated that supervisors who scored high in field independence endorsed less consideration than those who scored high in field dependence. But Erez (1979) found that the self-described consideration of 45 Israeli managers with engineering backgrounds was positively related to field independence and to social intelligence, whereas initiating structure was negatively related to these two factors.

Preferences for Taking Risks. Rim (1965) studied risky decision making by supervisors and reported that male supervisors who scored high on both consideration and initiating structure and head nurses who scored high on initiation of structure tended to make riskier decisions. Men and women who scored high on both tended to be more influential in their groups and to lead the groups toward riskier decisions. However, Trimble (1968) found that for a sample of teachers who described their principals as being higher in consideration than in initiating structure, neither of the principals’ scores was related to the principals’ perceptions of their own decision-making behavior.

Personal Satisfaction. Initiation and consideration are greater among more satisfied leaders, whose tendencies to make decisions and attempts to lead are also related. To some degree, these tendencies may be consequences rather than antecedents of initiation and consideration. Managers who are more satisfied with their circumstances tend to have higher LBDQ scores, according to Siegel (1969). Similarly, A. F. Brown (1966) reported that better-satisfied school principals were described as higher than dissatisfied principals on all subscales except tolerance of uncertainty.

Democratic versus autocratic, participative versus directive, and relations-oriented, task-oriented, transactional, and transformational leadership styles are discussed in Chapters 17, 18 and 19. It should come as no surprise that consideration and initiation are related to these other leadership styles. Miner (1973) noted that concepts used in other studies—such as providing support, an orientation toward employees, human relations skills, providing for the direct satisfaction of needs, and group-maintenance skills—are akin to consideration. Concepts similar to initiating structure include facilitation of work, production orientation, enabling the achievement of goals, differentiation of the supervisory role, and the utilization of technical skills. Miner further pointed out that with its emphasis on organizing, planning, coordinating, and controlling, initiating structure has much in common with the ideas of classical management.

Democratic and Autocratic Styles. Although factorially independent, the various scales of consideration and initiation contain the conceptually mixed bag of authoritarian and democratic leadership behaviors. Each scale contains a variety of authoritarian or democratic elements. Although empirically these elements cluster on one side or the other of authoritarian or democratic leadership, they are conceptually distinct. The industrial version, SBDQ, added strongly directive behaviors (“He rules with an iron hand”) to its factor of initiating structure (House & Filley, 1971).

Yukl and Hunt (1976) correlated Bowers and Seashore’s (1966) four leadership styles of support, the facilitation of interaction, emphasis on goals, and the facilitation of work with the LBDQ for 74 presidents of business fraternities. Support correlated .66 with consideration and .61 with initiation of structure. On the other hand, the emphasis on goals correlated .64 with consideration and .76 with initiation. Facilitation of work correlated .56 with consideration and .64 with initiation of structure. Clearly, a large general factor of leadership permeates all these measures, and leadership generally is or is not actively displayed. Karmel (1978) drew attention to the ubiquity of initiation and consideration in the study of leadership and in efforts to theorize about it. What she primarily added was the importance of the total amount of both kinds of activity by leaders, in contrast to inactivity.

This general factor becomes most apparent when the LBDQ rather than the LOQ is used. Weissenberg and Kavanagh (1972) concluded from a review that although managers think they should behave as if consideration and initiating structure are independent, in 13 of 22 industrial studies and in eight of nine military studies, a significant positive correlation was found between these two factors of leadership behavior on the LBDQ as completed by subordinates. This was especially so when LBDQ-XII was the version used in the survey (Schriesheim & Kerr, 1974). Seeman (1957) noted that a school principal’s overall leadership performance was seen to be a matter of how much consideration and initiation of structure were exhibited. When Capelle (1967) asked 50 student leaders and 50 nonleaders to fill out the LOQ, he found that leaders scored significantly higher than did nonleaders on both consideration and initiation of structure. However, G. W. Bryant (1968) did not find that appointed and sociometrically chosen leaders (college students in ROTC) differed significantly in their conceptions of the ideal leader on the LOQ. These results fit with the general contention that, conceptually, initiation of structure is readily distinguishable from consideration, just as autocratic and democratic or relations-oriented and task-oriented leadership can be conceptually discriminated. But empirically, the same leaders who are high on one factor are often high on the other as well.

Task and Relations Orientation. Initiation of structure emphasized concern with tasks (“Insists on maintaining standards,” “Sees that subordinates work to their full capacity,” “Emphasizes the meeting of deadlines”), as well as directiveness (“Makes attitudes clear,” “Decides in detail what should be done and how it should be done”). Consideration emphasized the leader’s orientation to followers (“Stresses the importance of people and their satisfaction at work,” “Sees that subordinates are rewarded for a job well done,” “Makes subordinates feel at ease when talking with them”), as well as participative decision making (“Puts subordinates’ suggestions into operation,” “Gets approval of subordinates on important matters before going ahead”). Social distance was also minimized for considerate leaders (“Treats subordinates as equals,” “Is easy to approach”). Conceptually opposite to initiation of structure is destructuring behavior (J. A. Miller, 1973a)—that is, reducing the request for consistent patterns of relations within the group. The lack of initiation of structure implies allowing conditions to continue without structure, avoiding giving directions, and avoiding being task-oriented. Conceptually opposite to consideration is leadership behavior that is exploitative, unsupportive, and uncaring (Bernardin, 1976).

Among 55 corporation presidents according to ratings by a staff member, a correlation of .55 was found between task-oriented production emphasis and initiating structure. Similarly, these presidents’ consideration correlated .49 with the relations-oriented representation of their subordinates’ interests and .41 with toleration of freedom of action for their subordinates (Stogdill, Goode, & Day, 1963a). W. K. Graham (1968) found, as predicted, that high-LPC (relations-oriented) leaders were described as higher in consideration and initiating structure than low-LPC (task-oriented) leaders. Yukl (1968) also noted that low-LPC leaders tended to be described as high in initiation and low in consideration. However, Meuwese and Fiedler (1965) reported that leaders who were high and low on LPC tended to differ significantly only on specific items of the LBDQ, not in the total scores for consideration and initiating structure. Yukl (1971) and Kavanagh (1975) concluded that task-oriented behavior is implicit in initiating structure, but subordinates can still influence their superior’s decisions. Misumi’s Production and Maintenance (PM) style of leadership uses maintenance items that correlate highly with consideration. Production has two components: pressure and planning. Pressure correlates highly with initiation of structure when measured by the original SBDQ, which contained items such as “Prods for production” but is less correlated with initiation of structure as measured by the LPDQ without such autocratic items (Peterson, Smith, & Tayeb, 1993).

Power, Authority, and Responsibility of the Leader. Martin and Hunt (1980) obtained LBDQ evaluations by 407 professionals and quasi-professionals of their first-line supervisors in the construction and design units of 10 state highway department districts. Related data on morale were also collected. The expert power of the supervisors correlated .44 and .41 with their initiating structure and .48 and .51 with their consideration; but the other sources of power—referent, reward, coercive, and legitimate—correlated close to zero with the leadership measures. Foote (1970) found that members of the managerial staffs of television stations who tended to describe themselves on the RAD scales6 as high in responsibility and authority also tended to be described on the LBDQ-XII as high in tolerance of freedom. Those who delegated most freely were described as high in production emphasis and low in representation orientation toward superiors.

Attempts to lead, manifest in one’s emergence as a leader in a leaderless group discussion, were negatively related to consideration and positively related to initiation of structure (Fleishman, 1957a).

Transactional and Transformational Leadership. Cheng (1994) suggested that transformational school-teachers could be innovative and could demand clear rules in managing the classroom (structuring) as well as provide support to the students (consideration). Seltzer and Bass (1987) found that for 294 MBAs with full-time jobs who described their immediate supervisors’ Initiation of Structure on the LBDQ-XII correlated .53, .55, and .59, respectively, with charisma, individualized consideration, and intellectual stimulation on the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ); and .48 and .06, respectively, with the transactional measures of contingent reward and management by exception on the MLQ. However, consideration on the LBDQ-XII correlated .78, .78, and .65, respectively, with the same MLQ transformational leadership measures and .64 and –.23, respectively, with the same MLQ transactional leadership measures. Evidently, active leadership is common to initiation, consideration, and transformational and transactional leadership behavior, and there are particularly strong associations between transformational leadership and consideration. Miliffe, Piccolo, and Judge (2005) reported correlations of .46 and .27, respectively, of transformational leadership with consideration and initiation. Furthermore, adding the transformational scales to initiation and consideration increased substantially the prediction of outcomes of the rated effectiveness of leaders and satisfaction with leadership. Similar results were reported for 138 subordinates and 55 managers (Seltzer & Bass, 1990).

Peterson, Phillips, and Duran (1989) found that the MLQ scale of charismatic leadership correlated higher with measures of consideration than measures of initiation in a study of 264 retail chain-store employees describing their supervisors. Thus charismatic leadership correlated .48 with maintenance orientation and .74 with support but only .16 with pressure for production and .22 with assigning work.

Greenleaf (1977, 1991), an AT&T executive, conceived the idea of the servant leader from Herman Hesse’s Journey to the East. Leo, the servant to a band of men on a mythical journey, does their menial chores but also sustains them with his spirit and song. Leo disappears. The group falls apart and the journey is abandoned. It turns out later that Leo is the titular head of the order that sponsored the journey. For Greenleaf, as for Hesse, the leader is the servant, first. The leader ensures that the highest priorities of followers are met. He first listens and questions before suggesting initiatives. Instead of coercion and manipulation, the servant leader depends on awareness, empathy, and foresight. To illustrate:

John Woolman visited Quaker communities for 30 years asking Quaker slaveholders about what … slave-owning did to them morally. … What were they passing on to their children? Non-judgmental persuasion followed. The Quakers became the first religious group in America to denounce and forbid slavery among its members. (Greenleaf, 1991, p. 21)

Servant leaders encourage skill and moral development in followers. They are sensitive to the needs of organizational stakeholders and hold themselves accountable for their actions (Graham, 1991). Servant leadership can be a model for higher education. Faculty members need to curtail and redirect their ego and image. Power needs to be shared with students. They become collaborators in an ethic of collective study. “The faculty member who has never learned from his students is a failure” (Buchen, 1998, p. 130). In Block’s (1993) replacement of leadership with stewardship, service is chosen over self-interest. As noted by Heuerman (2002), caring about others, seen in servant leaders, underlies considerate leadership behavior. Followers are regarded as real people, not machines or expense categories. For leaders who care, service is an obligation, not a burden. At the extreme of the leader as servant, leaders sacrifice themselves for the perceived good of the group. In experiments with 357 students and 157 industrial personnel, Choi and Mai-Dalton (1998) found that self-sacrificing leaders were seen as more charismatic and legitimate, and generated intentions to reciprocate. Self-sacrificing leaders were also judged as more competent by the students. Block (1993) argued that self-interest, dependency, and control of others should be replaced by organizational stewards with service, responsibility, and accountability.

The self-sacrificing servant leader has to be a good steward. Abraham Feuerman was praised for continuing to pay full wages to his employees at Malden Mills from reserves and insurance during the period it was out of operation after it burned down. He might have been expected to use the money to rebuild overseas to make use of cheaper labor, as other textile companies had done. Instead, he continued to pay his employees, who were able to return with high morale to a beautiful new plant, for which he became extensively indebted. Unfortunately, his competitors used the time to catch and pass Malden Mills and gain some of its customers. Product leadership was lost. Bankruptcy ensued. In attending to the needs of his people, the servant CEO had not fully taken care of his organization’s financial future.

The organization, the immediate group that is led, and the task requirements affect the extent to which a leader initiates structure, is considerate, or both. For instance, when faced with a complex task and need for planning, a leader is likely to be more structuring in a group of low diversity. Structuring and the leader’s planning skills contribute to the quality and originality of the plans, according to a study of 195 participants working in 55 groups (Daniels, Leritz, & Mumford, 2003).

Organizational Policies. A clear example of the impact of the organizational context on the behavior of individual leaders within it was provided by Stanton (1960), who described two medium-size firms. In one company, which was interested only in profits, authoritarian policies were dominant, and subordinates had to understand what was expected of them. The personal qualities of leadership were emphasized, and all information in the company was restricted to the managers except when the information clearly applied to an employee’s job. The second firm, which had democratic policies, stressed participation as a matter of policy and was concerned about the employees’ well-being as well as about profits. This firm made a maximum effort to inform the employees about company matters. Supervisors in the firm with democratic policies favored more consideration, whereas supervisors in the firm with authoritarian policies favored more initiation.

The importance of the higher authority represented by the organization and its policies also can be inferred indirectly from results obtained in a progressive petrochemical refinery and in a national food-processing firm, where the extent to which supervisors felt they should be considerate was positively correlated with how highly they were rated by their superiors (Bass, 1956, 1958). Yet in other companies no such correlation was found (Rambo, 1958). Supervisors’ perceptions of their superiors’ and subordinates’ expectations affect their leadership behavior. That is, supervisors will be more supportive or more demanding, depending on what they perceive their superiors and subordinates expect of them (Atwater, 1988).

Organizational Size. Vienneau (1982) examined the LBDQ scores of 33 presidents of amateur sports organizations, obtained from the responses of 85 members of their executive committees. Although the presidents’ sex or language was of no consequence, both consideration and initiation were higher in the larger of the amateur organizations. The presidents agreed on what was required of their ideal leader on the Ideal Leader Behavior Questionnaire regardless of other organizational differences.

Functional Differences. D. R. Day (1961) found that upper-level marketing executives were described on the LBDQ-XII as high in tolerance of freedom and low in structuring, but upper-level engineering executives were described as low in tolerance of freedom and high in initiation. In the same firm, manufacturing executives were rated high and personnel executives were rated low in tolerance of uncertainty.

Military versus Civilian Supervisors. Holloman (1967) studied military and civilian personnel in a large U.S. Air Force organization and found that superiors did not perceive military and civilian supervisors to be different in observed consideration or initiation of structure, although they expected military supervisors to rank higher than civilian supervisors in initiation of structure and lower in showing consideration. Unexpectedly, Holloman found that subordinates—both military and civilian—perceived the military supervisors to be higher in consideration as well as in initiating structure than they did the civilian supervisors. Thus in comparison with civilian supervisors, military supervisors were seen to display more leadership by both their civilian and their military subordinates.

Halpin (1955b) administered the ideal form of the LBDQ to educational administrators and aircraft commanders. Subordinates described their leaders on the real form of the LBDQ. The educators exhibited more consideration and less initiation of structure than did the aircraft commanders, both in observed behavior and in ideal behavior. But in both samples, the leaders’ ideals of how they should behave were not highly related to their actual behavior as described by their subordinates.

Attributes of Subordinates. Atwater and White (1985) and Atwater (1988) found that supportive (considerate) behavior by supervisors correlated highly with the subordinates’ loyalty and trust. Kerr, Schriesheim, Murphy, and Stogdill (1974) concluded, from a review of LBDQ studies, that if the subordinates’ interest in the task and need for information are high, less consideration by the leader is necessary and more initiation of structure is acceptable to them. Consistent with this conclusion, Hsu and Newton (1974) showed that supervisors of unskilled employees were able to initiate more structure than were supervisors of skilled employees in the same manufacturing plant. In a large sample survey of employees, Vecchio (2000) found that less mature employees were more inclined to favor structuring by leaders.

Chacko (1990) noted in data from 144 department heads in institutions of higher education that subordinates were more likely to be assertive and appeal to higher authority when their supervisors were low in structuring and in consideration. Gemmill and Heisler (1972) and Lester and Genz (1978) analyzed the impact of subordinates’ locus of control—internal or external—on their perceptions of their supervisors’ leadership and their satisfaction with it. Internally controlled subordinates tended to see significantly more consideration and initiation in their supervisors’ behavior (Evans, 1974). Although internally controlled subordinates in a textile and plastics firm tended to see their supervisors as initiating more structure, they also felt that their supervisors were less considerate (Duran & Nord, 1976). But Blank, Weitzel, and Green (1987) found correlations close to zero between the psychological and job maturity of 353 advisers of residence halls and the initiation and consideration, respectively, of their 27 residence-hall directors.

Except for a few cross-lagged analyses and experiments, most of the results reported here come from concurrent surveys of leadership behavior and criteria such as subordinates’ satisfaction and productivity. For instance, Brooks (1955) found that all the items measuring consideration and initiation of structure differentiated managers rated as excellent from those rated as average or below average in effectiveness. Although one tends to infer that productivity and satisfaction are a consequence of leadership behavior, the effective outcomes modify the leader’s behavior to some extent as well. Greene and Schriesheim’s (1977) longitudinal study suggested that more consideration early on by a leader can contribute to good group relations, which in turn may later result in higher group productivity. In any event, Fisher and Edwards (1988), in a series of meta-analyses, established that subordinates were more satisfied with work and supervision if their supervisors were high in consideration.

Using an early version of the LBDQ scales, Hemphill, Seigel, and Westie (1951) found that leaders’ organizing behavior (initiating structure) and membership behavior (consideration) were both significantly related to the cohesiveness of the group. Likewise, Christner and Hemp-hill (1955) noted that subordinates’ ratings of the leaders’ consideration and initiation were positively related to ratings of the effectiveness of their units, but leaders’ self-descriptions of consideration and initiation were not.

A sample of 256 MBA students who were working full-time in many different organizations described the initiation and consideration of their immediate supervisors at work. They also completed a “burnout” questionnaire. Although their leaders’ initiation correlated only –.15 with the respondents’ feeling of being burned out, the leaders’ consideration correlated –.55 with this feeling. Thus considerate supervision appears to reduce substantially the sense of burnout in subordinates (Seltzer & Numerof, 1988). Considerate supervision also promotes creativity, according to Oldham and Cummings (1996). They found that supportive and noncontrolling supervision of 171 employees in two manufacturing plants correlated with subordinates’ pattern disclosures, contributions to suggestion programs, and rated creativity. But Williams (2001) reported that the amount of structure supervisors initiated reduced the divergent thinking of their subordinates.

In an extensive analysis of 27 organizations involving more than 1,300 supervisors and 3,700 employees, Stog-dill (1965a) ascertained that supervisors’ consideration was related to the employees’ satisfaction with the companies and to measures of the cohesiveness of the groups and the organizations. But as with authoritarian and democratic leadership, neither the supervisors’ consideration nor their initiation of structure was consistently related to group productivity. Organizational differences had to be considered. The contribution to effectiveness of initiation and consideration appears quite variable and hence requires further examination of the context in which the data are collected.

Leader Behavior. Fleishman (1989a) reviewed more than 20 validity studies of the SBDQ. Fleishman, Harris, and Burt (1955) found that production foremen rated higher in performance by their managers were higher in initiation of structure and lower in consideration. But absenteeism and turnover were greater in work groups that had foremen with this pattern. Many other studies with the SBDQ have confirmed this strong relation between leader consideration and worker job satisfaction in industry (Badin, 1974; Fleishman & Simmons, 1970; Skinner, 1969), hospitals (Szabo, 1981; Oaklander & Fleishman, 1964), educational settings (Petty & Lee, 1975), and government organizations (Miles & Petty, 1977).

The relationship between initiation of structure, as measured by the SBDQ, and performance criteria tended to vary with situations. Thus both initiation of structure and consideration were positively related to proficiency ratings in nonproduction departments (Fleishman & Harris, 1955). Using the SBDQ, Hammer and Dachler (1973) showed that the leader’s consideration was positively related to the subordinates’ perceptions that their job performance was instrumental in obtaining the desired outcomes. However, the leader’s initiation of structure was negatively related to such perceptions. Likewise, Gekoski (1952) found that supervisors’ initiation of structure, but not their consideration, was related positively to group-productivity measures in a clerical situation.

Lawshe and Nagle (1953) obtained a high positive correlation, for a small sample of work groups, between group productivity and employees’ perceptions of how considerate their supervisor was. In a study of the leadership of foremen, Besco and Lawshe (1959) found that superiors’ descriptions of a foreman’s consideration and initiation of structure were both related positively to ratings of the effectiveness of the foreman’s unit. However, subordinates’ descriptions of foremen’s consideration, but not initiation of structure, were positively related to such effectiveness.