The Americanization of Zen Buddhism, the most prominent of the Japanese Mahayana traditions in this country, has been fostered by a broad movement to revitalize and modernize Zen institutions and practices that began in nineteenth-century Japan. At that time, Zen monastic institutions came under attack from Shinto nationalists. Income-producing estates that supported Zen monasteries were confiscated and an extensive Zen parish system that served laypeople was dismantled. Zen clergy increasingly abandoned celibacy for marriage and family, with the direct encouragement of the state. Many Zen leaders also were caught up in the rising tide of Japanese nationalism, only to face Japan’s defeat in World War II and the challenges of the return to normalcy.

For many Zen clerics, postwar reconstruction meant a return to providing pastoral care to laity, which largely consisted of performing memorial services for the deceased. Most did not pursue meditative practices beyond what was required of them in the course of their ministerial education and training. Others, however, sought to renew the spirit and practice of Zen, often by promoting meditation among Japanese laypeople. Some Zen leaders also began to see the United States as a land of opportunity for Zen, where its ancient genius could be revitalized, unencumbered by its Japanese institutional history.

The work of D. T. Suzuki at the center of the Zen boom in the 1950s was one expression of this interest in America’s potential to contribute to the revitalization of Zen. Another was the work a decade later of a number of Japanese teachers, who arrived here steeped in the Zen traditions of Japan but were often critical of its institutions. Once in the United States, they typically encountered Americans seeking authentic spiritual experience but wary of—often in flight from—institutionalized religion. The shared interest of these Japanese teachers and their American students in experiential religion unconstrained by institutions was, in many respects, a perfect marriage. This was particularly the case during the 1960s, when an anti-institutional spirit, epitomized by the counterculture but broadly diffused throughout American society, was in ascendance. This fit between the interests of teachers and students gave American Zen an innovative, sometimes antinomian, spirit that found a home in organizations formed three or more decades ago, often located in rented rooms and meeting halls and then in more substantial settings.

Other factors have contributed to Zen’s preeminence and its unique spirit. Zen has the longest American history of any form of convert Buddhism, going back to Shaku Soyen’s appearance at the World’s Parliament of Religions in 1893. Groups established before World War II laid the groundwork for the Zen boom of the 1950s and positioned Zen to reap many of the benefits of the much broader interest in Buddhism in the 1960s. Zen has also benefited from its substantial literary history in this country. Addresses of Shaku Soyen appeared in print in 1906. D. T. Suzuki and Alan Watts interpreted Zen for a broad American audience at mid-century. Beat poetry, with its marked passion for Zen, is now a part of the American literary canon. The Three Pillars of Zen: Teaching, Practice and Enlightenment, published by Philip Kapleau in 1965, and Shunryu Suzuki’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, published in 1970, are now among America’s Buddhist classics. More recently, a publishing boom has given Zen, or at least Zenlike ideas, a high public profile and a great deal of name recognition.

Zen is part of a tradition that was practiced for many centuries within monastic institutions across east Asia. In China it was known as Ch’an, in Korea as Son, and in Vietnam as Thien Buddhism, forms of a shared tradition that are now intermingling with Zen in creative ways in the ferment of American Buddhism. In Japan, Zen was divided into Rinzai, the school that emphasized the use of koans, and Soto, which emphasized sitting meditation. A number of influential Japanese teachers in the 1960s, however, taught both Rinzai and Soto to their American students, which helped to give an eclectic cast to the American practice of Zen, even though the two traditions retain distinct institutions in this country. As a whole, American Zen is primarily a movement of laity who practice monastic disciplines, a trend that has also fostered innovation as practitioners seek to balance rigorous practice with the demands of the workplace and family. The laicization of monastic practice is sometimes hailed as an example of democratization of Buddhism in this country, although it has many Japanese precedents.

Zen is the most popular form of Buddhism among converts who meditate, but their number is very difficult to estimate. Unlike Jodo Shinshu, Zen is not identified with a particular ethnic community, although Zen temples serving Japanese Americans played an important role in its transmission to the United States and remain a part of the American Zen mix. Unlike Soka Gakkai, Zen has no central administration to make estimates of its membership. Many of its most prominent institutions, however, were founded by Japanese teachers and their American students during the 1960s. Collectively, these flagship institutions can be said to represent mainstream American Zen. They help to set the pace for meditation centers across the country and often provide them with teachers. Their leaders are often well-known, well-respected figures in the broader Buddhist community. With few exceptions, the leadership of these institutions passed to a generation of native-born, American teachers in the last decades of the twentieth century, a development hailed by many as the coming of age of American Buddhism. By the turn of the century, these teachers’ students had begun to come of age as teachers in their own right, creating a third, in a few cases a fourth, generation of American Zen teachers and leaders.

Mainstream Zen and Its Flagship Institutions

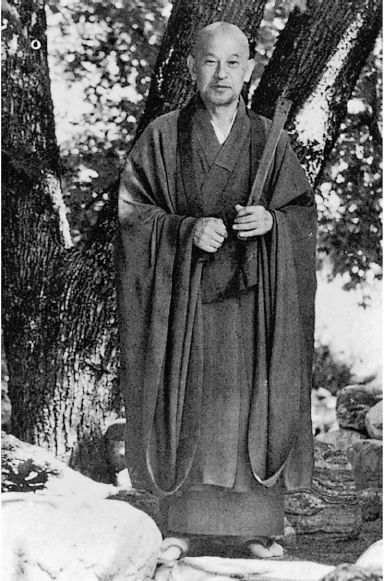

Many of the innovative qualities of American Zen have been attributed to Hakuun Yasutani, who was influential in trans-Pacific Zen circles until his death in 1973. He is seen to have epitomized the modern Japanese Zen reformer—deeply steeped in the traditions of Zen, eclectic in his approach to practicing it, and critical of its institutions. Born in 1885, Yasutani was sent to a Rinzai Zen temple at age five, where he was educated by its abbot. At eleven, he moved to a Soto monastery and became a monk. At sixteen, he moved yet again to study with a well-known Soto leader and commentator on Dogen’s masterpiece, the Shobogenzo. Throughout his twenties and thirties, Yasutani continued his training with a succession of Buddhist teachers. He also completed his secular education and began a career as an educator. At thirty, he married and began to raise the first of five children.

At the age of forty, Yasutani entered a new phase in his Buddhist vocation. He was soon actively engaged in propagating Soto Zen in Japan, when he met the Zen master Daiun Harada, a teacher of both Soto and Rinzai, and began to practice with him. In 1927, at the age of forty-two, Yasutani attained kensho, a breakthrough insight into the nature of Buddha mind. In 1943, he finished koan study with Harada and received dharma transmission, which is essentially a seal of approval given to a student by his or her teacher. Their teacher-student relationship was of sufficient importance that Philip Kapleau, Robert Aitken, and Yasutani’s other students are often said to be in the Harada-Yasutani teaching lineage. Yasutani soon turned his attention to training laity, both men and women, an activity that consumed much of his time for the next thirty years. He eventually broke his connections to both Soto and Rinzai Zen institutions and founded his own school, the Sanbo Kyodan, or Three Treasures Association, in 1954, which he viewed as more true to the spirit and form of Dogen’s original teaching.

Many of Yasutani’s reforms, while controversial in Japan, became taken for granted in a broad swath of the American Zen community. He incorporated both the Soto emphasis on zazen and the Rinzai use of koans into the teachings of the Sanbo Kyodan. He gave lay practitioners the attention and care that had been formerly reserved for monastics and modified the traditional course of training for resident monastics by condensing practice into intensive retreats to fit laypeople’s schedules. He particularly emphasized the attainment of kensho as way to start lay practitioners on a path that could be deepened through further sitting and koan study. Yasutani also minimized the ceremonial life of the Japanese temple and adapted what he retained to the practice needs of the laity. For non-Japanese practitioners, both male and female, he greatly eased the linguistic and social barriers that were inherent in traditional, monastery-based training.

Yasutani’s impact on American Zen came most directly through two of his American students, Philip Kapleau and Robert Aitken, both of whom played important roles in early, 1960s-era Zen Buddhism. Philip Kapleau was Yasutani’s first American student. He had studied with a number of teachers in Japan, but began his formative work with Yasutani in the mid-1950s, practicing in a series of twenty intense, protracted periods of Zen training. After spending eleven years in Japan, Kapleau returned to the United States. In 1965, he published The Three Pillars of Zen, a book leagues ahead of Suzuki and Watts in how it addressed the actual practice of Buddhism, which introduced Yasutani and his style to many Americans. In 1966, Kapleau founded the Rochester Zen Center in Rochester, New York, one of American Zen’s earliest training institutions. Through his publishing and teaching, he was instrumental in the formation of American Zen. Kapleau made further innovations in the name of Americanization. He encouraged his students to retain American dress, gave them Anglicized dharma names, and used English translations of sutras in the course of training, a particular innovation that drew Yasutani’s criticism.

Of Kapleau’s students, some went on to form Zen centers in Vermont, Denver, and overseas in Poland. But his best-known student, Toni Packer, eventually broke with Kapleau and the Rochester center, taking with her a number of his students to found Springwater Center, also in central New York. By the 1990s, Packer was among a number of American teachers who had begun to cut Zen loose from its moorings in the doctrine, tradition, and ethos of Japan, seeing them as stifling its capacity to awaken Americans. She established herself as an independent teacher, separate from both the Harada-Yasutani lineage and, more significantly because she represents one trend in the Americanization of Buddhism, the entire concept of lineage. “Truth itself needs no lineage, it is here, without past or future,” she told an audience at a Buddhist conference in Boston in 1997. Referring to a koan that emphasized “preserving the house and the gate,” that is, the entire tradition of Zen, she said: “That’s not what I’m interested in. I wish for Springwater to flourish in its own spontaneous and unpredictable ways, and not become a place for the transmission of traditional teachings.”1 Packer’s post-traditional approach is suggested by the general and inclusive name of her organization, the Springwater Center for Meditative Inquiry and Retreats.

Like Kapleau, Robert Aitken had a significant impact on the early stages of American Zen. He first became interested in Buddhism while in an internment camp in Japan during World War II. After the war, he briefly studied with Nyogen Senzaki in Los Angeles and was later introduced to practice in Japanese monasteries. He began serious study and practice with Yasutani in the mid-1950s. In 1974, the year after Yasutani’s death, he received dharma transmission from Koun Yamada, Yasutani’s successor as head of the Three Treasures Association.

From early on, Aitken and his wife Anne were at the forefront of the Americanization of Zen. They co-founded a Zen sitting group in Hawaii in 1959, later called the Diamond Sangha. They began to lead Zen groups at a time of transition from an earlier, mystical fascination with Buddhism to the more practice-oriented interests that emerged during the 1960s. Aitken recalls that the first retreat he held in Hawaii “saw the tag end of interest in theosophy and general occult things. There were folks who had studied Blavatsky and her successors and who had gone through all kinds of spirit-writing episodes and astrology. The young people didn’t start to come until the dope revolution.”2 Since its founding, the Diamond Sangha has grown into a network of affiliated Zen centers in Hawaii, Australia, and California.

Aitken has been described as the dean of American Zen. His translations of sutras and gathas, Buddhist hymns, have been used in many Zen centers in daily services. He has long been an astute observer of grassroots developments in American Zen, and has contributed to its ongoing formation by participating in many conferences and consultations. As a consistent supporter of Native Hawaiian, gay and lesbian, and women’s rights issues, he also represents the liberal/left political and social tilt that is conspicuous in many American Zen quarters. With Gary Snyder, one of the most renowned Beat Buddhist poets, and Joanna Macy, a leading American Buddhist teacher and intellectual, Aitken co-founded the Buddhist Peace Fellowship (BPF), a pioneering organization linking American Buddhist practice and social activism. By the 1990s, BPF was emerging as another important American Buddhist organization in its own right.

Due to the early influence of Shaku Soyen, his colleagues, and their students, the Rinzai tradition was most prominent in American Buddhism at the opening of the 1960s. Joshu Sasaki, Eido Tai Shimano, and other Rinzai teachers further contributed to the development of American Rinzai in the following decades. By the late 1990s, Sasaki and Shimano were among the few pioneering teachers from Japan still alive and continuing to teach.

Sasaki arrived in Los Angeles in 1962, and he and his students soon incorporated as the Rinzai Zen Dojo. Over the next two decades, they founded the Cimarron Zen Center in Idyllwild, California, the Mt. Baldy Zen Center in the mountains east of Los Angeles, and the Bodhi Manda Zen Center in Jemez Springs near Santa Fe, New Mexico. His many students subsequently established a network of meditation centers that ranged from Puerto Rico to Vancouver and from Miami, Florida to Princeton, New Jersey.

Shimano began his work in New York City in 1964, where he revitalized the Zen Studies Society, which was originally founded to support the work of D. T. Suzuki. It is now the leading Rinzai Zen institution on the East Coast. He later established International Dai Bosatsu Monastery in the Catskill Mountains on Beecher Lake, a secluded site once the retreat of the Beecher family of Connecticut, which was influential in nineteenth-century Protestant evangelicalism. The monastery serves as a “country zendo” for New Yorkers who sit at its city center in Manhattan; soon after it opened on July 4, 1976, it became one of the important, and certainly one of the most elegant, training institutions in this country.

Both Sasaki and Shimano have been fairly traditional in their approaches to the traditions of Zen. On matters of doctrine and practice, Shimano has been described as a “go slow” Americanizer, and International Dai Bosatsu Monastery appears to be a traditional Zen center transplanted to this country. Japanese visitors, however, readily identify it as American—men and women live and practice together; lay students, who form the bulk of those in training, practice alongside monastics. But a powerful Japanese aura lingers in the design of the monastery, the Buddha images in its meditation rooms, and its landscaping. This mixing of Japanese and American sensibilities remains important in American Zen; its aesthetic appeal can be sensed in Shimano’s remarks in 1972, when he consecrated the Beecher Lake property to monastic use in perpetuity.

I, the Reverend Eido Tai Shimano, the president of The Zen Studies Society, Inc., hereby, with a reverential heart, ask the Deity of Dai Bosatsu Mountain, Lake and Field to hear my declaration.

On behalf of all the Sangha I ask forgiveness for our destruction and pollution of all rocks, trees, grasses, and mosses, and the nature of the Catskill Mountains, particularly by the Beecher Lake.

We ask your permission to establish a Zen monastery on this very site and ask your protection from earth, water, fire, and wind, and any other possible damage.

May this place be peaceful, calm, creative, and harmonious for all the years to come and for all people who may come here, generation after generation.3

The Soto lineage moved into prominence in America toward the end of the twentieth century, largely due to the success of Shunryu Suzuki, who founded the San Francisco Zen Center (SFZC), and Hakuyu Taizan Maezumi, who established the Zen Center of Los Angeles (ZCLA). Both teachers were sons of Soto priests. They arrived in this country to serve the Japanese American Zen community, but soon gained a following of other American students. Both made immense contributions to an American tradition of Zen Buddhism. Unlike Yasutani, who had a programmatic approach to the reform of Zen, Suzuki retailored the tradition for America on a trial-and-error basis. Maezumi’s approach was from the outset more eclectic, as he had received dharma transmission from Soto and Rinzai teachers as well as from Hakuun Yasutani. Both teachers also established strong teaching lineages. Their students emerged in the 1980s and ’90s as among the most prominent native-born teachers of American Zen.

Much of the early history of the San Francisco Zen Center was shaped by the fact that it was at the tumultuous heart of the San Francisco counterculture of the 1960s. Many countercultural social and political ideals subsequently infused this sangha, giving it a deserved reputation for innovation and creativity. The early death of its founder, Shunryu Suzuki, in 1971 also forced SFZC to confront a range of succession and leadership issues well in advance of most other American Zen communities.

Like many other Zen priests in Japan, Suzuki followed his father into the clergy, expecting to take over the family temple. After being educated in a Buddhist high school and university, he trained at Eiheji and Sojiji, the two leading Soto training centers in Japan. He later married and began to raise a family. Still in his thirties, Suzuki took a position as head of a network of Soto-affiliated temples.

Among the most influential Japanese Zen teachers, Shunryu Suzuki taught many American men and women in the San Francisco Bay area during the 1960s, a pivotal era in American Buddhist history. His legacy includes three monastic institutions that now comprise the San Francisco Zen Center, a large network of affiliated practice institutions, and Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, a book of his teachings that is now an American Buddhist classic.

SAN FRANCISCO ZEN CENTER

Suzuki came to the United States in the late 1950s on a three-year, temporary appointment at Sokoji, the Soto Zen temple in San Francisco, where his primary responsibility was to provide pastoral care for the Japanese American community. But from the outset, he also maintained his passion for zazen (sitting meditation), an element of the Soto tradition that held little appeal for most of his parishioners. By the early 1960s, Suzuki was leading between twelve and thirty people, most of them non-Japanese, in zazen each morning. In 1962, this fledgling group of American Buddhists incorporated as the San Francisco Zen Center.

Within a few years, as the Zen boom of the 1950s turned into the Buddhist explosion of the 1960s, the number of people showing up at Sokoji to learn to meditate under Suzuki’s leadership dramatically increased. Some rented apartments near the temple, creating the nucleus of a full-blown community. Richard Baker, who later became an influential leader in that community, recalls that prior to this time Suzuki displayed little interest in the rituals and practices found in traditional Zen monasteries. “He thought that real Mahayana practice should be done in the streets and with people in ordinary circumstances.” A few years later, however, Suzuki began to require more disciplined monastic-style practice from his students, which he refashioned to suit their unique needs as laypeople, often with families and living in communal settings within the broader Bay area countercultural community. “You have to understand,” Baker recalls, about the gradual emergence of a new form of Buddhist institution in San Francisco, “the whole question of residency came up when ‘flower power’ was in full bloom.”

Everybody was taking acid. Things were a little out of hand. And I felt that we should take more responsibility. The turning point for Suzuki Roshi came when he began to feel that the apartments had become like buildings on the temple grounds; they were part of the temple. At some point his feeling was that Zen Center should accept the responsibility because, in effect, it already had the responsibility. But he always saw common residences as an extension of the temple, not the organization of the community.4

In a memoir of these early years, Erik Storlie recounts the circuitous route he followed through the counterculture to Buddhism. Storlie recalls finding himself at Sokoji for the first time in 1964, after an LSD trip on Mount Tamalpais, a favorite haunt of Bay area hippies. He describes the small inner room of the temple, where fifteen men and women sat in a semicircle on folding chairs facing Suzuki, a small man in his late fifties with a shaved head, wearing a simple brown robe and carrying a worn book. Storlie also conveys a sense of the mystique that surrounded both Zen and Suzuki. “He opens the book, and I see that it’s filled with rows of oriental characters. The Buddha statue, the flowers, the strange little man, this curious book—I feel transported to some distant time and place, far from the city that begins outside the door on the foggy streets.” The inchoate emotions Suzuki evoked in Storlie eventually led him to spend a lifetime as a practicing Buddhist. “Something I can’t name is welling up in me. It’s the devotion of this small, simple man for an ancient poetry he loves. It is in the images from nature that touch the everyday and the eternal—fish and water, birds and sky—an endless sunlight shedding beauty, sweeping forever through an infinite universe.… ‘Yes, I’ll be here,’ I say to myself. ‘I’ll hear him talk again.’”5

At about this time, San Francisco Zen Center also began to take shape as one of America’s leading Buddhist institutions. In 1966, the Center acquired Tassajara Hot Springs, an old resort in the coastal mountains several hours south of San Francisco. This was on the eve of the “summer of love,” when the counterculture was about to peak and then go into a devastating tailspin. For a time, Tassajara took on the guise of a countercultural institution. Beat poetry readings, Buddhist workshops, and an Avalon Ballroom “Zenefit” featuring the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane were held to pay off a portion of its $300,000 mortgage, although the bulk of the money eventually came from East Coast philanthropists. Tassajara was, however, intended to be a place where Americans could begin to practice Buddhism seriously. Center leaders saw that if Buddhism was to survive the 1960s and the counterculture movement, it would need strong American roots. They envisioned Tassajara as a Zen training institute or monastery.

In 1969, the Center also purchased a building on Page Street in San Francisco, formerly a residential hotel for Jewish women, which enabled the growing community to establish a headquarters independent of Sokoji. Suzuki resigned his post at the temple in order to devote himself full time to his students. Several apartment buildings for Center members were eventually purchased in the neighborhood. During this time, Suzuki began to ordain American students as Zen priests in order to invest them with the kind of status and authority held by Japanese clergy. He also instituted a form of “lay ordination,” an innovation meant to address the ambiguous status of most American practitioners, who were neither traditional monastics nor typical laypeople. In 1972, Green Gulch Farm in Marin County, a location within an hour’s commute from Page Street, was added to the growing list of properties owned by the Center. For a time, it was a Bay area showcase for Aquarian spiritual sensibilities, in equal parts an experimental farm, a home for Center families, a public lecture hall, and a back-to-the-land retreat.

Shunryu Suzuki died in 1971, but in 1966 he had ordained Richard Baker as both a monk and a priest. Baker was also Suzuki’s dharma heir, or spiritual successor, which authorized him to teach. Baker was named the new abbot of SFZC, and he subsequently provided much of the leadership that enabled it to grow into one of America’s leading Buddhist institutions. Under his leadership, however, the Center also faced difficulties in making the transition from the Aquarian-age ’60s to the Ronald Reagan era. Extraordinary pressures came to bear on Center members as their original idealism was called into question in the 1980s. Resentment about Baker’s high-profile leadership and questions about his lifestyle eventually flared into what he later called the “ZCM”—the Zen Center Mess.6 Amid charges of an abuse of power and sexual misconduct, Baker resigned in 1983, but soon took up the leadership of new Zen communities, first in Santa Fe, New Mexico and then in Crestone, Colorado. Leadership of SFZC shifted to Tenshin Reb Anderson, another dharma heir of Suzuki, who served as its abbot until 1995.

As a result of this traumatic experience, the Center pioneered elective leadership, a cutting-edge development seen as an important turning point in the Americanization of Zen. In the early 1990s, SFZC’s Board of Directors adopted a set of “Ethical Principles and Procedures for Grievance and Reconciliation,” which reflected the integration of the Buddhist precepts with interpersonal problem-solving and conflict resolution. In the mid-1990s, SFZC undertook an experiment unthinkable in Japan: the establishment of joint leadership of the community by two of Suzuki’s students. Zoketsu Norman Fischer was first installed as abbot in 1995, but he was joined a year later by Zenkai Blanche Hartman, who was also named abbot. Hartman was certainly the first Zen abbot to be a mother and grandmother, and she is among a large number of women who have become American Zen leaders and teachers.

At the end of the century, the Page Street Center (now the Beginner’s Mind Temple or Hosshin-ji), Tassajara (now the Zen Mind Temple or Zen-shin-ji), and Green Gulch Farm (the Green Dragon Temple or Soryu-ji) remained at the institutional core of the San Francisco Zen Center. It also had a large number of affiliates since many of its students had become teachers at centers throughout the United States. In 1998, Center leaders sponsored a high-profile, public-spirited series of lectures and workshops they called “Buddhism at Millennium’s Edge,” which featured many of the leading Buddhist scholars and practitioners in the convert community—Gary Snyder, Joanna Macy, and Reb Anderson, to name only a few. “As we approach the end of this human millennium, so full of confusion and violence, we’re presented with a great challenge: how to repair ourselves and our world,” wrote co-abbots Hartman and Fischer. “Buddhism can help. Each of the extraordinary speakers who address us in this series of talks and workshops has created a unique translation of ancient wisdom into contemporary terms. Their insights will inspire us and shine some light on the road ahead.”7

The Zen Center of Los Angeles (ZCLA) followed a trajectory somewhat similar to that of SFZC in the 1960s and ’70s. Its founder, Hakuyu Taizan Maezumi, first served as a priest with the Soto mission at Zenshuji temple in Los Angeles, where he tended to the pastoral needs of Japanese American parishioners even as he began to teach zazen to others. By 1967, ZCLA had moved into a rented house; by 1980, it had grown to 235 members, about 90 of them living in a community-owned complex of houses and apartments that took up an entire square block of west central Los Angeles. In 1976, Maezumi established the Kuroda Institute for the Study of Buddhism and Human Values, a nonprofit educational organization dedicated to promoting Buddhist scholarship. It sponsors conferences and workshops and publishes two series devoted to East Asian Buddhism with the University of Hawaii Press—one scholarly studies, the other translations of classic texts. At about the same time, Maezumi also founded the White Plum Sangha, an association of his students who, by the end of the ’70s, had begun to set up Zen centers of their own in various parts of the country. After Maezumi’s unexpected death in 1995, the White Plum Sangha was formally incorporated. It now operates as an extended America dharma family that, in the words of its president, Dennis Genpo Merzel, in 1997, works together “with open communication and respect for one another, in fulfilling Maezumi Roshi’s dream of establishing the dharma in the United States and world-wide.”8

ZCLA and its many affiliates represent the kind of diversification that was taking place within American Zen during the 1980s and 1990s. Some of Maezumi’s students led monastic-style centers inspired by traditional Zen, while others focused more exclusively on the kind of innovation required to support family practice. Some worked to integrate the dharma and the arts, while others were more directly involved in social action. There are both mountain retreats and inner-city centers affiliated with the White Plum Sangha, and its geographical reach currently extends along the West Coast from Portland to San Diego to Mexico City; east to Salt Lake City, Chicago, and New York; across the Atlantic to Britain, France, and Poland; and across the Pacific to New Zealand.

Like SFZC, the White Plum Sangha includes many women. Among Maezumi’s older students, Charlotte Joko Beck, who has taught for many years at the San Diego Zen Center, emerged as an important teacher in the 1980s. Somewhat like Toni Packer, Beck abandoned many of the Japanese elements of Zen, and the spirit of her teaching is conveyed in the titles of her well-received books, Everyday Zen and Nothing Special: Living Zen, and in the name of her teaching lineage, Ordinary Mind School of Zen. By 1998, the Ordinary Mind School had centers in San Diego, Champaign, Illinois, Oakland, California, and New York City. At about that time, Jan Chozen Bays, who leads a family-oriented practice in Portland but is interested in developing a residential monastic center, began to emerge as a prominent national teacher.

Many centers were also established by men in the White Plum Sangha, two of which represent the complex ways traditionalist and innovative impulses coexist in American Zen today. John Daido Loori moved from Los Angeles to establish Zen Mountain Monastery (ZMM) in the Catskills region of New York State in the early 1980s. Located on 200 acres of fields and forest, ZMM provides Zen training for a lay and monastic community on a year-round basis. Loori, the abbot, has described his approach as “radical conservatism,”9 by which he means that Buddhism’s rich Asian heritage, adapted to the needs of Americans, can serve as the basis for a genuinely alternative form of transformative spirituality.

Loori grounds ZMM programs in what he calls the “Eight Gates of Zen,” which include sitting meditation, liturgy, face-to-face learning with the teacher, the study of Buddhism, work practice, the observation of Buddhist precepts, body practice, and the arts. Even though most practitioners at ZMM are laypeople, Loori chose to model his organization on monastic precedents because he and his students wanted the more rigorous monastic lifestyle and practice to set the pace for the entire community. By the 1990s, ZMM had established three distinct tracks for study and practice—secular, for those who sought to cultivate awakened consciousness with no religious overtones; lay Buddhist, for householding practitioners; and rigorously monastic, in the spirit of the Ch’an and Zen traditions of China and Japan. It had also established a number of Buddhist social programs that ranged from prison mission work to wilderness preservation.

Loori and ZMM have also developed innovative forms of Buddhist educational outreach through Dharma Communications, a not-for-profit corporation dedicated to bringing Buddhism to those without easy access to centers and teachers. Dharma Communications publishes The Mountain Record, a quarterly that features articles on Buddhism and art, science, psychology, ecology, and ethics. In 1998, they were about to launch an “Open Monastery,” a range of media services including an interactive CD-ROM and online communications, to foster Zen training. ZMM also has a network of affiliated centers called the Mountains and Rivers Order, inspired by Dogen’s Mountains and Rivers Sutra. It was founded to foster the practice of members in New York City, Albany, New York, Burlington, Vermont, and in three centers in New Zealand.

But Loori keeps this highly articulated organization at the service of the spirit of Zen. “We should really be clear,” he noted during his installation as abbot in 1989—in a traditional ceremony during which a new abbot is said to ascend the mountain—“that zazen is not meditation, is not contemplation.”

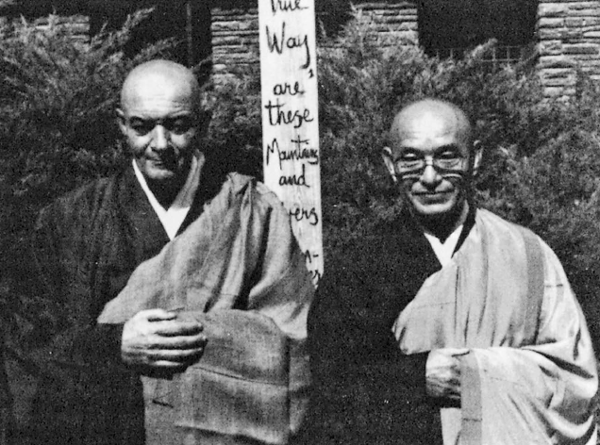

Hakuyu Taizan Maezumi, shown here with John Daido Loori at Zen Mountain Monastery in Mount Tremper, New York, led the Zen Center of Los Angeles until his death in 1995. Maezumi’s students and their own students have formed the White Plum Sangha, a dharma family of Zen teachers who by the 1990s led centers in Mexico, Europe, New Zealand, and across the United States. ZEN MOUNTAIN MONASTERY ARCHIVES

It’s not stilling the mind or focusing the mind, mindfulness or no mind. It has nothing to do with mudras, mantras, mandalas, or koans. Nothing to do with understanding or believing. This zazen I speak of, this sitting Zen, is also walking Zen, working Zen, chanting Zen, laughing Zen, and crying Zen. Zen is a way of using our mind, living our life, and doing it with other people. And yet there’s no rule book. This zazen I speak of is the flower opening within the world. So to be in the mountains manifests the freedom that master Dogen is speaking of, the freedom to follow the wind and ride the clouds.10

Bernard Tetsugen Glassman, Maezumi’s most senior student, has taken the tradition in quite a different direction to become one of American Zen’s most well-known innovators. Glassman was an aerospace engineer at McDonnell-Douglas before beginning to study Zen in the 1960s. He moved from Los Angeles to New York in 1979, where he established the Zen Community in New York (ZCNY) in the Greyston mansion in Riverdale, a wealthy section of the Bronx. In 1982, the community opened Greyston Bakery, a gourmet specialties business located in Yonkers, with the goal of securing financial support for the sangha.

By the mid-1980s, however, Glassman decided to pursue a more socially active role in this economically depressed city in Westchester County. ZCNY soon sold its headquarters and purchased an old Catholic convent in Yonkers, which subsequently became the home of the Greyston Mandala, a network of organizations dedicated to developing Zen as a force for social change. Glassman soon expanded the goals of the bakery to include providing employment for the needy, homeless, and unskilled. He and his wife, Sandra Jishu Holmes, then opened the Greyston Family Inn, a homeless housing facility providing shelter, child care, and job training to the Yonkers community. Their vision of the integration of Zen practice with both business and social activism is outlined in Glassman’s Instructions to the Cook: A Zen Master’s Lessons in Living a Life That Matters.

Since then, Glassman has increasingly directed his energy to social transformation as a vehicle for the practice of Zen. He became well known for leading “street retreats” in run-down neighborhoods of New York City, during which participants share the reality of homelessness as a form of Buddhist meditation. After participating in an Auschwitz retreat sponsored by Nipponzan Myohoji, a Nichiren Buddhist movement best known for its Peace Pagodas and Walks for Peace, Glassman began to lead similar retreats himself, seeing them as a uniquely powerful way to realize the meaning of the Buddha’s teaching on death and impermanence. He discusses his vision of social transformation as a way of realization in Bearing Witness: A Zen Master’s Lessons in Making Peace, published in 1998.

In the same year, Glassman and Holmes left the Greyston Mandala in the hands of senior students and relocated to Santa Fe, New Mexico, where they planned to devote themselves full-time to building a new institution, the Zen Peacemaker Order. In March of that year, Holmes died suddenly in Santa Fe, but Glassman continues to develop the Order and its own unique expression of the American Zen spirit. Its three core tenets are “Not-knowing, thereby giving up fixed ideas about ourselves and the universe; bearing witness to the joy and suffering of the world; and healing ourselves and others.” Its members subscribe to four commitments agreed upon by delegates to the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago in 1993, the centennial celebration of the original event at which Shaku Soyen and other Asian Buddhists first introduced Buddhism to the United States:

I commit myself to a culture of nonviolence and reverence for life;

I commit myself to a culture of solidarity and a just economic order;

I commit myself to a culture of tolerance and a life based on truthfulness; and

I commit myself to a culture of equal rights and partnership between men and women.11

The emphases of Loori and Glassman in their work represent the way Zen is taking on different shapes in this country. Both are men of the same generation, both are students of the same teacher, and both work out of a shared tradition whose leading historical figure is the thirteenth-century Japanese master Dogen. Both have taken it upon themselves to adapt tradition to the needs of Americans. Loori’s Eight Gates of Zen can be profitably read alongside Glassman’s Bearing Witness, or the video Oryoki: Master Dogen’s Instructions for a Miraculous Occasion, produced by Loori’s Dharma Communications, can be viewed in light of Glassman’s Instructions to the Cook to see how Zen is currently following different paths in America, even while maintaining a degree of internal consistency.

American zen Practice and worldview

During the last half of the twentieth century, Zen flourished in America and took on institutional forms unlike either Jodo Shinshu or Nichiren Buddhism. But to focus on its leading organizations (and many others could be noted here, from lay-oriented Cambridge Buddhist Association in Massachusetts to the contemplative order at Shasta Abbey in northern California) is not to suggest that Zen in America can be solely identified with its Japanese founders, their students, and their institutions.

First of all, the Asian tradition of which Zen is a part is being reworked in America to a degree that is very difficult to assess as the Ch’an (Chinese), Son (Korean), and Thien (Vietnamese) traditions interact with one another. No discussion of this stream of Asian Buddhism in the United States is complete without attention to teachers such as Hsuan Hua, Seung Sahn, Thich Nhat Hanh, and others, whose contributions are treated in chapters 10 and 12. As important, the literary heritage of American Zen, which has al ways been closely linked to its spirit, has continued to flourish from Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance in the 1970s to Natalie Goldberg’s Long Quiet Highway: Waking Up in America in the 1990s. Through essays and poems, Zen and Zenlike ideas have begun to reach into the lives of many Americans who have no commitment to practicing the tradition.

There is in America also a lively phenomenon the Japanese call bujizen, a term that in a traditional context refers to self-styled Zen practitioners who disdained the kind of institutional discipline associated with formal traditions and teaching. Seen in a positive light, bujizen is an expression of free-form spirituality and a source of considerable creativity. Much of the artistic expression of Buddhism among the early Beats, as well as the Zen popularized by Alan Watts, might be considered American bujizen. Seen negatively, bujizen is often dismissed as a kind of self-deluded indulgence that mistakes egotism for awakening. However one evaluates self-styled Zen, it suits America’s individualist ethos very well and, as evidenced in the explosion of Zen-inspired popular publishing, there is likely to be a great deal more of it in this country.

Committed practitioners, however, continue to hold the traditional disciplines of Zen in high regard, even as they are adapting them to suit the spirit, tenor, and language of American society. The specific forms these disciplines take are often encoded in the practice vocabulary of Zen discussed below, which, while arcane and confusing to the uninitiated, is taken for granted in most monasteries and dharma centers across the country. Some Americans dismiss such vocabulary as an undesirable remnant of Japanese influence, but others see it as an essential part of the tradition to be maintained in the process of cross-cultural translation.

ROSHI In the Japanese tradition, the word roshi literally meant “old or venerable master.” It has long been a title conferred upon an individual who has realized the dharma, is possessed of honorable character, and has been certified as having passed through years of training under a Zen master. It was assumed a roshi had received shiho, or dharma transmission, which is given when a teacher is satisfied that a student has achieved a genuine insight into enlightenment. This is the basis of the “mind-to-mind” transmission of the dharma that is crucial in the formation of Zen lineages. Shiho was also confirmed by a master through inka, which means “seal of approval” and connotes a confirmation of enlightenment. In Rinzai circles, inka is associated with the successful completion of koan study.

In some American Zen communities, roshi retains this formal meaning, as it does in Zen institutions in Japan. Within communities such as the San Francisco Zen Center and the White Plum Sangha, the founding teachers were called Suzuki Roshi and Maezumi Roshi by their students. The title roshi was subsequently conferred on their students who were recognized as having successfully completed a full course of training. For instance, John Daido Loori is now referred to by his dharma name, as Daido Roshi. Bernard Tetsugen Glassman is referred to as Tetsugen Roshi or, alternatively, as Glassman Roshi. But roshi has also passed into more general parlance both in Japan and in the United States. It is often used in a nonspecific way to convey students’ respect and admiration for their teachers. As a result, the use of the term varies from community to community.

SENSEI Sensei also means “teacher” and is used in different ways in different institutional settings. In the White Plum Sangha, for instance, sensei denotes one who has not received inka but has received shiho, or dharma transmission, and thus is called a dharma heir of their teacher. In contrast, a dharma holder has successfully completed part of the course of training with a teacher, but has not received shiho and is thus not yet a full dharma heir. Dharma holder connotes an assistant teacher. Like roshi, sensei is also used in some settings as a generally honorific term.

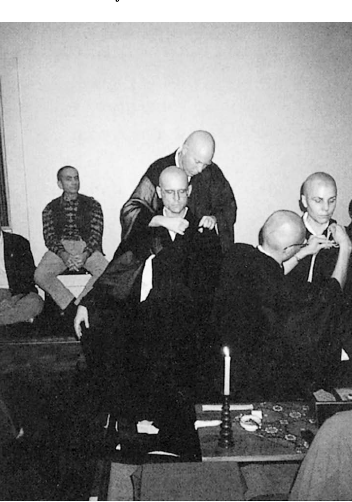

The highly formalized monastic practices of Japanese Zen are changing in this country as American practitioners, most of whom are laypeople, begin to reinterpret the forms and language of the tradition to suit a new cultural context. This man and woman at the Hazy Moon Zen Center in Los Angeles are undergoing tokudo, a form of Zen ordination that generally denotes a high degree of commitment to monastic practice. HAZY MOON ZEN CENTER

TOKUDO As in the history of Jodo Shinshu Buddhism, the translation of Japanese terms into English can result in confusion. For instance, the term tokudo literally means “attainment of going beyond” and is often translated as “monk’s or monastic ordination.” It is generally reserved for full-blown Zen monastic practice, a commitment that only a small number of Americans have chosen to make. The terms monk and nun, however, are used in this country in a variety of ways because, in the absence of institutions with powerful traditions, what it means to make a commitment to Zen is in flux. In any case, the terms monk, nun, and monastic usually do not imply celibacy as they do in the Christian tradition. Nor do they necessarily mean that an individual is expected to reside in a monastic community.

JUKAI A more neutral term that is also translated as “ordination” is jukai, which literally means “receiving or granting the precepts.” In this country, jukai is a formal rite of passage that marks entrance into the Buddhist community. At that time, a student is given a dharma name, such as Chozen in Jan Chozen Bays. He or she also makes a commitment to the precepts, which are interpreted a bit differently in various communities. The White Plum Sangha follows the Soto tradition, which ordinarily accepts sixteen precepts. These include taking refuge in the Three Jewels; the three pure precepts (to do no evil, to do good, and to do good for others); and the ten grave precepts: 1. Do not kill; 2. Do not steal; 3. Do not engage in sexual misconduct; 4. Do not lie; 5. Do not become intoxicated; 6. Do not speak of others’ faults; 7. Do not elevate yourself while demeaning others; 8. Be generous to others; 9. Do not be angry; and 10. Do not slander the Buddha, dharma, or sangha.

ZAZEN In the rich practice vocabulary of Zen, the most important term is zazen. The word is derived from za, which means “sitting,” and zen, which means “absorption.” In its most classical form, zazen is done seated in the full lotus position on a meditation cushion called a zafu, although more relaxed postures and alternative forms of support are commonly used in this country. Zazen is usually done with eyes open, but cast down and lightly focused. In classic Soto centers, it is often done facing a blank wall. Practitioners may follow their breath or work on a koan during zazen. But many do not consider zazen meditation in the general sense of the term because often there is no object on which one meditates. For them, zazen is encountering the mind’s incessant activity and, in Dogen’s famous expression, learning to “think nonthinking” on a moment-to-moment basis.

KINHIN Kinhin is a form of walking meditation practiced in Zen centers and monasteries between periods of zazen. In the Rinzai tradition, it is done quickly and energetically, sometimes at a jog. In the Soto tradition, it is more often done slowly. In the eclectic style of Zen often found in the United States, it is done both ways. Some teachers use it out of doors with the specific intention of developing attentiveness to nature and the interdependence of all living things in the natural environment.

KOAN Most basically, a koan is a story about or remarks made by earlier roshis, used to instruct Zen students in the dharma. Some practitioners understand koans as paradoxes whose solution requires a cognitive leap that transcends one’s normal way of thinking. Others treat them as depictions of situations that must be fully experienced and embraced as having no solution. Systematic koan study is most closely associated with Rinzai Zen, but in the United States koans are used, both formally and informally, in a variety of settings. Here, the term koan may also refer to conflicted situations in life that, given proper attention, can aid one on the path of realization. For instance, a lay Zen practitioner might say that his or her attempt to reconcile practice and family is a koan he or she is working on. In this sense, all matters of life and death can be regarded as koans and thus important steps in the process of realization.

DOKUSAN Dokusan literally means “going alone to a high place.” It refers to a private meeting or interview between teacher and student, the content of which is usually kept secret. Dokusan plays an important role in Zen training. During dokusan, a master will assist a student with problems he or she faces in practice. If the student is working on a koan, it provides an occasion for him or her to display progress in understanding it, which a teacher may confirm or refute. Sometimes an interview is simply an encounter between teacher and student in silence. There are many stories about the enigmatic behavior of teachers in the dokusan room, so the experience can be anxiety-provoking for students. Traditionally, dokusan has been highly ritualized, but in many American Zen centers it has taken on a more informal character.

ORYOKI Oryoki literally means “that which contains just enough.” The term refers to a set of nested eating bowls that a Zen monk or nun traditionally received at ordination. These bowls, in particular the largest of them, which is called “the Buddha bowl,” are considered symbolic of the single one that Shakyamuni allowed his disciples to use in their begging rounds. Oryoki also refers to the use of these bowls in meals eaten in silence in Zen monasteries. Eating oryoki-style is a form of Zen practice. Food is first offered to the buddhas and bodhisattvas, and is only then consumed by the community. This kind of practice underscores the conviction that every aspect of life can be the occasion for the realization of enlightenment. Oryoki is a familiar feature in monastically inclined American Zen centers. Some communities eat oryoki-style on a daily basis, others only occasionally. Sometimes oryoki is performed slowly and elegantly and at other times energetically, quickly, even somewhat sloppily.

SAMU Samu means “work service” or “work practice.” Like oryoki, samu underscores the everyday character of the realization of enlightenment. Most specifically, it refers to the performance of tasks necessary to maintain a Zen center or monastery, which are undertaken in the spirit of service to the community. It is an occasion to perform mundane chores in a meditative state of mind, and it plays an important role in most phases of Zen training. In a more expanded sense, samu is related to right livelihood, one step on Shakyamuni’s Eightfold Path. Lay practitioners in this country who need to integrate their work lives with practice often approach their professional activities as a form of samu in a wholly secular setting.

SESSHIN, ANGO Sesshin and ango are particularly intense and protracted periods of practice. Sesshin means “collecting the heart-mind.” It is usually a period of three or seven days, held at regular intervals in the calendar of a Zen community, during which students are able to focus on their practice and develop a sustained relationship to their teacher. Sesshins are usually conducted in complete silence. Some take on a ceremonial dimension as well. For instance, a Rohatsu sesshin is held to coincide with the date Shakyamuni is said to have attained enlightenment. In interreligious groups that practice Zen, an Advent sesshin might be held to coincide with the birth of Jesus Christ. Ango, which means “dwelling in peace,” is a three-month-long period of intensive practice. It is a counterpart to the rainy-season retreats of bhikkhus and bhikkhunis in ancient India.

This kind of vocabulary—and there is a good deal more of it—remains important to American Zen today. It also reflects the complex, ongoing processes at work in the adaptation of Buddhism to this country. At the height of the ’60s, very few Americans who were drawn to Buddhism had any knowledge of samu, oryoki, dharma transmission, and the like. From the writings of D. T. Suzuki and Alan Watts, they may have associated Zen with an intuitive approach to the world, as well as paradoxical and enigmatic forms of wisdom. Or their initial exposure to Buddhism may have been the Beat poets, Madame Blavatsky, or Timothy Leary and LSD. At any rate, few grasped what Buddhism in general and Zen in particular entailed as a disciplined way of life and a form of religious commitment.

The Americanization of Zen is often presented as a one-way street, a process of only reshaping a Japanese tradition to suit the tone and tenor of American society. Zen in the United States becomes more informal. It is Anglicized. It is democratized. It is tailored to the middle-class American lifestyle, with its focus on the workplace and nuclear family. As many advocates for Americanization have correctly remarked, Buddhism, and Zen in particular, has throughout its long history displayed a capacity to adapt to a wide range of cultural and national settings. But as a description of the Americanization of Zen, this is curiously incomplete. Many Americans have also been adapting themselves—in fact they have been self-consciously disciplining themselves—to the Japanese traditions of Zen for well over three decades. Zen philosophies, meditation practices, rituals, and vocabularies were taken up by many Americans as they built the flagship organizations of American Zen, a task that required a great deal of labor, money, and commitment and, no doubt, many, many hours of zazen.

There are numerous issues yet to be thrashed out in American Zen. The relationship between American practitioners and the source of their tradition in Japan is much discussed insofar as it bears on practice styles, institutional authority, the legitimacy of the teachings, and a wide range of other questions. It is probably safe to say that there are currently as many positions on how to pursue this relationship—enthusiastic embracing of Japanese models, keeping a respectful distance, maintaining cautious skepticism, and exhibiting outright disdain—as there are Americans seriously engaged in Zen practice.

Some Buddhists are also concerned that Americanization will lead to a decline in the dharma if the aspiration to realize Buddha mind becomes overidentified with psychotherapy, or if practice becomes too accommodating to the economic and emotional needs of the American, middle-class family. Others, however, see precisely those kinds of adjustments as the unique contributions Americans can make to an ancient tradition of philosophy and practice. There are also fascinating questions about how Zen, the leading form of Buddhist meditation in the country, will evolve as it is influenced by the Tibetan and Theravada traditions, which have their own communities of meditating convert Buddhists. It is not possible to forecast these developments, but the fact that they are on the horizon is a reminder that the Americanization of Zen, however much it has progressed in the course of several generations, is far from complete.