Theravada Buddhists in this country can trace their origins to the World’s Parliament of Religions of 1893, when Anagarika Dharmapala presented a stirring vision of the Buddha as a religious reformer whose teachings could heal the modern schism between science and religion. But America’s first Theravada temple, the Buddhist Vihara Society in Washington, was established only in 1966, and it functioned primarily as a center for diplomats and foreign visitors to the capital city. Since then, the tradition has assumed a very prominent role in American Buddhism and, due to its size and complexity, it is likely to have an immense impact over the long term. There are, however, at least three distinct tiers to American Theravada Buddhism, so it is less a single community than a spectrum of positions along which different kinds of Buddhists practice the dharma under institutional and cultural conditions that vary considerably.

South and southeast Asian Theravada immigrant communities are at the traditional end of the spectrum, where the dharma is being Americanized by perennial forces in immigration history such as Anglicization and generational change. Asian Theravada is conservative in many respects, but has undergone significant alterations in the modern period. One trend has been the growth of institutions of higher education for bhikkhus, which has led some monks to adopt roles as progressive social and political leaders. Another is the emergence of the retreat center, where monastics and laity set aside their traditional social and religious roles and devote themselves to meditation. A forest ascetic movement has also been important in the past century and a half, introducing rigorous forms of Buddhist practice into the south and southeast Asian hinterlands; some immigrant and native-born American Theravadans follow this practice in the United States. New religious roles have also begun to emerge among Theravada women. There are numerous female renunciates in south and southeast Asia even though the bhikkhuni lineage died out in the tenth century. Questions about whether to reestablish this lineage are a source of lively contemporary debate among Buddhist women both in Asia and in the United States.

Convert Buddhists in the Insight or vipassana meditation movement are at the other end of the spectrum. Many of these Buddhists studied in retreat centers in Burma and other countries in southeast Asia in and around the 1960s, then returned to the United States to become teachers. In most important ways, these Buddhists identify themselves with Zen practitioners and other European American converts who engage in sitting meditation. They share a strong interest in adapting the dharma to the needs of western laity. Ritualism and the traditional ceremonial cycle of Buddhist holidays tend to be kept to a minimum, and there is little interest in or sympathy for the concept of merit-making. As with other forms of American Buddhism emerging among converts, this kind of Theravada Buddhism is often highly influenced by western secular humanism and psychotherapy; the movement as a whole is both applauded and criticized for its many innovations.

Theravada immigrants and converts live in very different social and cultural worlds and have different religious priorities, which militates against the creation of a unified American Theravada community. However, a number of significant developments led by monastics tend to blur the boundaries between these two large camps. Some university-educated Asian monks have taken up work in this country that bridges the two communities. Other connections are being made by westerners who, having undergone lengthy monastic training in south or southeast Asia, are able to move between the two worlds as teachers and leaders. Relative to the immigrants and converts, they do not comprise a particularly large group but represent a creative synthesis between the two, and one model for the integration of tradition and innovation.

Additional variables give a great deal of texture and variation to Theravada Buddhism in this country. The first is country of origin. Among immigrants are Sri Lankans, Thais, Cambodians, and other national groups whose communities in this country are often distinct, although their Buddhist traditions share a strong family resemblance. Another variable is mode of entry. Most Theravada Buddhists are immigrants, but others are refugees, which often has a significant influence on the shape and mood of a particular community.

A third, more complex variable is related to the distinction between monastics and laity. In traditional communities, Theravada bhikkhus follow the vinaya, the regulations that order life and practice in the monastic sangha, and they usually retain the high status accorded them in Asia. There are lay-based immigrant groups in this country, but most Asian American laity continue to practice their religion through rituals and devotional expressions that are understood to be occasions for merit-making. In convert communities where the majority of Buddhists are laypeople who meditate, the monastic model has been by and large abandoned, although monks sometimes play prominent roles as exemplars and teachers.

Theravada in the Immigrant Community

Immigrant Theravada monastics and laity have been working for about thirty years to build a network of Buddhist institutions that is now among the most extensive in the country. Paul Numrich, one of the few scholars to direct sustained attention to recent immigrant Buddhism, estimates that there were between a half and three quarters of a million Theravada immigrants at the time of the 1990 census. In 1996, he confirmed the existence of about 150 organizations functioning as Theravada temples, called wats (Thai) or viharas (Sri Lankan), in more than thirty states, but mostly in California, Texas, New York, and Illinois, which have absorbed the bulk of the Asian immigrants. Many of these have been formally recognized by one or another Asian Theravada sect as consecrated temples. Others are monastic residences that also serve as communal religious facilities. Many more informal temples probably exist in apartments and houses in immigrant and refugee communities.

Upon arriving in the United States, Theravada immigrants were first preoccupied with social adjustment, economic survival, and the emotionally complex processes involved in Americanization. Religious life in the temple was often rudimentary. Many viharas and wats were first formed as Buddhist societies by laity, often from different ethnic and national traditions, who then worked with religious authorities in Asia to arrange for monks to immigrate. Much of their energy was channeled into attempting to reconstitute the religious life of their homelands. In the early years, tensions often arose around ethnic and sectarian issues. Different parts of the community reacted in different ways to legal, social, and religious questions raised in the course of adapting their traditions to a radically new setting. Some tensions became long-standing as differences emerged among ethnic and national groups and as monks and laypeople disputed who should hold authority in religious communities. Questions also emerged about the degree to which temples were to be strictly religious or to serve a range of social, cultural, and religious functions. All these conflicts tended to foster the differentiation of Theravada religious life, as new temples were formed to meet the needs and aspirations of particular constituencies.

By the mid-1980s, many communities had passed into another phase, in which the most pressing concerns were related to second-generation issues. As children and grandchildren became thoroughly Anglicized and Americanized, the process of translating Theravada traditions into American forms began in earnest, with the establishment of after-school programs, Buddhist summer camps, and Sunday dharma schools. At about that time, many Theravada communities also entered into a “brick and mortar” stage of Americanization. With financial resources more readily available, new temples could be purchased or built, often in suburban locations, to more satisfactorily meet the needs and aesthetic tastes of their congregations. Other communities, however, did not have this luxury. Roughly 40 percent of Theravada Buddhists arrived in the United States as refugees, including hundreds of thousands of Laotians and Cambodians fleeing war and revolution in southeast Asia. They encountered many emotional obstacles on the road to Americanization, and have tended to remain clustered in low-rent, inner-city neighborhoods in cities like Chicago and Long Beach, California.

During this entire period, Americanization had a unique impact on immigrant bhikkhus struggling to live in accord with vinaya regulations regarding dress, food, and money. “Los Angeles certainly wasn’t made for Theravada village monks,” notes Walpola Piyananda, abbot at a vihara in southern California. “When I first arrived, food was quite a problem. Of course I had no money and no notion of cooking for myself.” The challenges monks faced on a personal level also had repercussions for the entire community. Sri Lankan immigrants in Los Angeles, he recalls, “expected me to be an ideal, perfect village monk. They didn’t want to see a monk wearing shoes, socks, or sweaters. They couldn’t bear to see a monk even shaking hands with women. This was difficult, as in dealing with Americans, if I refused to shake hands, people took offense.” He further reflected on the difficulties presented by the urban environment. “I constantly faced the challenge of meeting the social customs of the U.S. head on, dealing with things that did not seem to coincide with the letter of the Vinaya.… I needed to drive, as Los Angeles is virtually uninhabitable if you can’t get around, and certainly it makes a monk useless if he cannot reach his community.”1

While many Theravada temples are located in houses, old school buildings, or storefronts, Wat Thai in Los Angeles is one of many new temples constructed across the country since the 1980s. Here the community is celebrating Vesak, the Buddha’s birthday, one of the most important holidays in the Buddhist calendar. DON FARBER

Even weather reshaped the life of the monastic community. In 1990, Robert W. Fodde, the American security officer at a wat near St. Louis, wrote to the head of the Mahanikayas, a Thai monastic order in this country, pleading for an alternative to monastic dress. While cotton robes were suited to south Asia, he argued that their continued use during midwestern winters put monks at serious risk. “It is easy to picture a car-load of monks being driven to a meeting during the cold winter months, having their car break down and freezing to death before help could arrive. Easy to see the possibility of a furnace breaking down, and monks hospitalized with hypothermia,” he wrote. “It is clear that a modified uniform is not a luxury, but a necessity.”2 Fodde suggested that the monks abandon their monastic robes and adopt the kind of uniform worn by Christian clergy, an idea Mahanikaya leaders rejected. But the order soon permitted adjustments in dress, and bhikkhus now wear thermal underwear beneath their robes, knit caps, heavy sweaters, and socks with their sandals in winter, usually dyed the traditional ochre of the Theravada sangha.

Some of the stark challenges that often faced refugees are recounted in Blue Collar and Buddha, a documentary about Laotians in the mid-1970s arriving in Rockford, Illinois, a rust belt city with high unemployment. The film focuses on the anger and resentment directed at Laotians by vocal groups in Rockford, who viewed them as competitors both for welfare and for low-paying jobs in a troubled economy. Others frankly expressed their hatred for people they associated with the defeat of the United States in southeast Asia. The film’s second focus is on the religious life in the temple, a small wood-frame farmhouse set amid cornfields at the edge of the city, which became the target of bombings and shootings in the 1980s. With its fenced-in compound, some locals viewed the temple as a symbol of the Laotians’ unwillingness to assimilate. Others feared that nefarious activities went on there, mistaking the temple, with its monks in robes and sandals, for an Asian kung-fu training center.

For the Laotians, however, the temple provided social and religious continuity. The film’s narrator, a Laotian artist who worked as an upholsterer for Goodwill Industries, describes how a festival drawing several hundred people to the temple expressed a variety of religious meanings. “The New Year’s festival is important for people of my country,” he notes, as men, women, and children are shown offering trays of rice, fruit, and vegetables, as well as toilet paper and Twinkies, to monks ranging in age from the late teens to the fifties. Some offerings had personal intentions. “They celebrate by bringing food to the monks and money for the temple.… People don’t have money. People don’t have jobs. But they want to give food and money because it brings them merit. This will help them to be reborn in a better state.” Others had a more communal emphasis: “Or they may give this merit to people who have died,” he continues.

If their parents have died this merit can help them wherever they have been reborn. When monks eat the food, people feel that the spirit of the dead mother or father enjoys that food too. They give food to make these spirits happy. After the monks and spirits have eaten, everyone else eats that food too.3

Temples are often points at which the traditional Theravada worldview and American culture intersect, as at Wat Promkunaram near Phoenix, where in 1991 a tragedy disrupted the community’s quiet march toward Americanization. The wat was founded as a home temple by Thais, Laotians, and Cambodians in 1985. In 1985, the prospering community purchased five acres of land to build a new, $300,000 suburban wat with an office, a monastic residence, and a large shrine room. The new temple opened in May 1989 and shortly thereafter hosted the thirteenth annual conference of the Council of Thai Bhikkhus, one of a number of Theravada monastic organizations in this country. In 1991, nine people lived in the wat—six monks, one novice, one nun, and a young man described as “a temple boy to chant and recite Buddha’s teaching and sit in meditation in the morning and evening.”4 But in August of that year, two Thai women arrived at the wat to cook meals for the residents, a form of meritorious religious activity, and found all nine murdered in the shrine room.

The tragedy built bridges between Wat Promkunaram and the broader community, even as it underscored the differences between them. Temple leaders educated reporters as they answered questions about theft as a motive for the killings: monks do not wear jewelry; they are not even allowed to touch money; the Buddha image in the shrine room was not solid gold, but gilded concrete. The Thai ambassador met with the governor of Arizona and the local investigative team. Monks and relatives flew in from Asia and children returned home to help parents cope with the tragedy.

But at the same time, the Theravada community was confronted with alien American mores. The shrine room was cordoned off for a week as a crime scene. The nine bodies were taken to the morgue for autopsies, and it cost the community $30,000 to secure their release. When they were returned to the temple from the funeral parlor, their faces were heavily made up. “In my village when a monk died we put poison herbs in the body’s mouth,” said one woman, a waitress at a Thai restaurant, “and the spirit returned and told the monk who killed him. Here they won’t let us touch the bodies.”5 Some recalled omens foreshadowing the crime and others had dreams that offered clues to its solution. One man attempted to contact the deceased monks in meditation. Two highly Americanized young men related to the victims made plans to go to Thailand for ordination in order to dedicate the merit to their deceased relatives.

Few immigrant communities experienced such devastating developments, but most faced probing questions raised by local zoning boards, which often served as immigrants’ first encounters with American bureaucracy. Can a monk’s home in a residential neighborhood be considered a public temple? Is it an appropriate place for communal religious festivals? Who is to be held responsible for parking problems and traffic congestion? Are gilded spires on wats and viharas in keeping with community aesthetic standards? Is sutra chanting through the night a public nuisance or an exercise of the constitutionally guaranteed freedom of religion? These were the fundamental issues of the Americanization process for many Theravada immigrants during the 1980s and ’90s, as they built a network of temples in a range of national traditions, all with common elements of ritual and religious etiquette. A grasp of some of these elements is essential to understanding the distinct form of Buddhism found within the Theravada immigrant community.

Theravada Practice and Worldview

Prostrations

Making prostrations is a basic ritual of respect in Theravada temples. Before entering a shrine room, both laity and monks remove their sandals or shoes. Upon entering, they make a prostration before the Buddha image, kneeling with palms together at the level of the chest or head, then bowing forward to the floor three times. Laypeople also make ceremonial prostrations before monks, because they are thought to embody the triratna or Triple Gem. In the course of teachings and rituals, monks normally teach from a raised platform, while laity sit lower, on the shrine room floor, as a sign of respect.

Chanting

Chanting is central to the religious life of the temple. Virtually every rite begins with three chants: the first is the Namo Tassa, which means “homage to the blessed one”; the second is the Tisarana or the Three Refuges. The third, the panca sila, is the recitation of the five precepts. These provide an introductory framework for a range of additional rituals performed on specific occasions. Most of the chanting is done by the monks in Pali, but some responsive chanting between monks and laity is done in the vernacular—Thai, Sinhalese, another southeast Asian language, or, increasingly, English. Monks conduct morning and evening sessions of chanting in Pali, which may or may not be attended by laypeople. Laity may also conduct their own chanting sessions, sometimes in English. These sessions often include a period of meditation, perhaps twenty minutes to a half hour long, often the only occasion laity meditate.

Buddha puja, which is roughly translated as “Buddha homage,” is an integral part of the religious life of the Theravada temple. Like prostrations, it is done more as a sign of respect and veneration than worship as understood in Christianity. Buddha puja can be done as an individual act: a devotee will place a small gift of water, incense, or flowers on the altar before the Buddha image. In the context of a collective ritual meal, small portions of each dish are arranged on a tray and passed among the congregation so that each can touch it. The tray is then placed on the altar as a collective offering.

Other forms of puja common in south and southeast Asia are found in American Theravada communities. Deva puja (roughly, “god homage”) is a form of veneration given to a wide range of animistic deities. Although not entirely orthodox, these rituals and deities were long ago incorporated into popular Theravada practice. There is some indication that the veneration of these deities, who are intimately associated with particular Asian locales and regions, will not be successfully transplanted to the United States. Bodhi puja, another popular practice with a long history that dates back to ancient India, is the ritual veneration of bodhi trees, in honor of the pipal tree under which the Buddha gained enlightenment.

Sanghika Dana

Sanghika dana (or sangha dana) means “offering or gift to the sangha.” Laity who prepare and serve meals to monks are performing one form of sanghika dana, as are those who donate goods deemed requisite for monastic practice by the vinaya. The most basic gifts are robes, begging bowls, belts, razors, and a few other items, but they may include money, groceries, toothpaste, and other necessities. Sanghika dana is a central element in Kathin, one of the major festivals shared by all Theravada national traditions. During Kathin, laypeople replenish the stores of the monastic community by making gifts, especially gifts of robes, in the first months after the rains retreat, a time when monks traditionally gather in a communal setting. But sanghika dana is also done on an individual basis when a lay donor seeks counsel from a monk, commemorates the death of a loved one, or comes to have his or her fortune told or palm read. In response to lay gift-giving, monks perform rituals of blessing such as chanting Pali texts or, in the Thai tradition, whisking water over a donor’s head.

On some occasions, special vows are taken by laypeople, both men and women. They take eight precepts (the panca sila plus no eating after midday, no worldly amusements, and no luxurious sleeping arrangements, which includes maintaining celibacy) and spend from a day to a week living a contemplative life in the temple. In some Theravada traditions, young men have the opportunity to be temporarily ordained into the sangha as bhikkhus for varying lengths of time. During this period, they are instructed in the dharma and monastic principles and practices to prepare them for their adult lay lives. A higher ordination is also sometimes taken by adults, who are then considered a part of the monastic sangha for a period of time varying from a few days to several years.

Some temples are experimenting with “lay ordination” for American converts who join the temple. This functions as a rite of passage into the serious practice of Buddhism, but does not require maintaining celibacy or adhering to other monastic regulations found in the vinaya. Few Americans have taken full monastic ordination. Among those who have, there is a tendency for many to later relinquish their vows or to move to Asia, where there are fewer distractions from the pursuit of a monastic vocation. A new generation of Americans who became interested in Buddhism in the 1990s, both women and men, appeared to have fewer qualms about taking full ordination; if this trend continues, it may significantly influence the development of Theravada in this country.

Vesak

Vesak or Visakha is a spring celebration that commemorates Buddha’s birth, enlightenment, death, and passing into nirvana. It is the most important Buddhist holiday in Asia, although its observance varies according to national tradition. In this country, it has become the occasion for a common celebration that unites different Buddhist traditions and schools. It is also the traditional festival most frequently attended by non-Asian Buddhists. At Dharma Vijaya Buddhist Vihara in Los Angeles, for example, Vesak extends over a weekend and draws hundreds of people. The temple and its compound are first thoroughly cleaned and then festooned with lights and streamers, and a Buddha image is installed on the porch of the temple. A pavilion is also constructed where monks will sit and engage in hours of chanting. The opening hours of Vesak are devoted to more or less secular activities, such as performances by the children of the dharma school, award presentations, and orations. The religious core of the festival consists of an all-night program that includes chanting, Buddha puja, ordinations, and a range of other rituals, all of which come to an end the following morning with a communal meal served to the monks by hundreds of laypeople.

Vipassana Meditation

Vipassana is translated as “insight” and denotes the highest form of Buddhist meditation in the Theravada tradition. There are, however, a variety of ways vipassana techniques are taught in different traditions and groups. In some Theravada traditions, primarily the Burmese and Sri Lankan, vipassana is used to promote moment-to-moment awareness of the fleeting phenomena in the mind and body. In others, primarily the Thai forest tradition, vipassana is not seen as a distinct technique but as a quality of awareness that comes from developing insight into the laws of karma while cultivating mental tranquility. Traditionally, vipassana meditation was the province of monastics, but lay meditation movements have become increasingly important in modern Theravada countries in south and southeast Asia.

The Vipassana or Insight Meditation Movement

The vipassana or Insight Meditation movement among convert Buddhists stands at the opposite end of the spectrum from immigrant Theravada Buddhism. It originated in lay-oriented meditation retreat centers in south and southeast Asia and is among the most powerful and popular forms of convert Buddhism in the United States. The dynamics of immigration, distinctions between monks and laity, and ritualism have played only a small part in the creation of the American movement. The most prominent teachers are lay Americans who traveled to Asia in the 1960s, where they trained with a variety of Theravada teachers, some of them monks and others laypeople. These Americans later returned home and began to teach one or another form of vipassana meditation, more or less divorcing it from traditional monastic and lay elements in the religious life of Theravada immigrant communities. These teachers also developed an eclectic style in their efforts to indigenize the dharma, freely drawing upon other schools of Buddhism, other religions, and humanistic psychotherapy to create readily accessible forms of Buddhist practice.

Ruth Denison is among the American pioneers of this movement. She and her husband first became interested in Asian religions in the 1950s. They traveled to Asia in 1960, spending time in Zen monasteries before studying Theravada forms of meditation at a center in Burma. After returning to America, Denison frequented the Zen Center of Los Angeles but continued to return to Burma for training, at a time when Theravada meditation traditions were virtually unknown in this country. Denison began teaching in 1973 and soon gained a reputation for her energetic approach to practice and her use of music, movement, and rhythm, emphases she attributes both to her background in humanistic psychology and to Theravada meditation techniques that focus on sensory awareness. This approach to meditation, she told Insight, a movement journal, means

Never a dull moment,—and a demand for total participation from the students and the teacher. This in turn cultivates a wonderful spirit of genuine communion. Most of all, I encourage people to go into their difficulties and to cope with the change that’s taking place even as they are paying attention to it. Our life is nothing but change and it is to this change that I bow deeply. I bow to this change, I bow deeply to life itself.6

In 1977, Denison bought a desert property near Joshua Tree, California, which eventually grew into Dhamma Dena, an important movement retreat center since the early ’80s.

The year 1975 was an important turning point in the movement: Sharon Salzberg, Jack Kornfield, Joseph Goldstein, and others, all having trained with Theravada teachers in Asia, founded the Insight Meditation Society (IMS) in Barre, Massachusetts. Salzberg first went to India at age 18, and eventually studied Buddhism with teachers from India, Nepal, Bhutan, Tibet, and Burma. Kornfield became interested in Asian religions during his undergraduate years at Dartmouth College. After graduating in 1967, he joined the Peace Corps and worked in Thailand, where he met the first of a number of meditation teachers. Several years after returning to the United States in 1972, he began teaching and eventually took a Ph.D. in clinical psychology. Goldstein also became interested in Buddhism as a Peace Corps worker in Thailand and in 1967 took up vipassana meditation, subsequently studying under a number of Asian teachers. He began to teach in 1974, the year before IMS was founded. For over a decade, IMS was the flagship of the movement; then, in 1988, Kornfield helped to found a West Coast counterpart at Spirit Rock in Marin County, California, which has since become an integral part of the San Francisco Buddhist community.

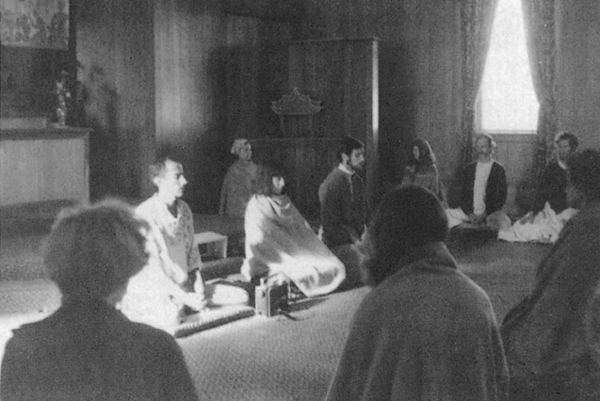

The founding of the Insight Meditation Society in 1975 was an important event in the development of Theravada-based lay practice in this country. Here IMS founders Jack Kornfield, Sharon Salzberg, and Joseph Goldstein are shown teaching together in the Barre, Massachusetts center in 1977. INSIGHT MEDITATION SOCIETY

Unique characteristics of the Insight Meditation movement have helped it grow into one of the most popular forms of American Buddhism. Like Zen, it is a movement of laity engaged in the meditative practices traditionally associated with monasticism. But in contrast, it is less associated with the vocabulary, history, and literature of one particular Asian tradition, a factor that has helped it to assimilate quickly to the style and ethos of the American mainstream. At the same time, many of the books written by its teachers, which are readily available on audio cassettes, have an appealing devotional and inspirational tone reminiscent of the heartfelt piety found in comparable popular movements in Judaism and Christianity. But as a whole, Insight Meditation is not presented as a religion but as an awareness technique fostering awakening and psychological healing through the use of practices taught by the Buddha.

As in the case of Zen, the tenor of the movement has changed over the course of the past three decades. In the 1970s, leaders focused on insight or vipassana meditation, which in Theravada is considered the culmination, not the beginning, of training. It is used to realize the Buddha’s teaching on the insubstantiality of the self, the impermanence of the universe, and the universality of suffering.

In the 1980s, Insight Meditation began to emphasize metta or lovingkindness meditation, the starting point for practice in traditional Theravada training. This shift is reflected in books such as Salzberg’s Lovingkindness: The Revolutionary Art of Happiness and A Heart as Wide as the World, and in Kornfield’s A Path With Heart: A Guide Through the Perils and Promises of Spiritual Life. Some teachers also began to absorb Mahayana ideas about the bodhisattva’s compassion in a way that underscored the movement’s basic orientation to western humanism and American idealism. “We now begin by awakening the heart of compassion and inspiring a courage to live truth as a deep motivation for practice,” Kornfield wrote. “This heart-centered motivation draws together lovingkindness, healing, courage, and clarity in an interdependent way. It brings alive the Buddha’s compassion from the very first step.”7 This blending of West and East, humanism and Buddhism, is also prominent in the teaching of Sylvia Boorstein, a well-known figure long associated with IMS and Spirit Rock. Her books, such as It’s Easier Than You Think and Don’t Just Do Something, Sit There, are among the movement’s most widely known introductory classics.

Over the course of the 1990s, some leaders of the movement, especially Jack Kornfield, advocated the idea that a distinct style of Buddhist practice was already emerging out of the often tumultuous experience of the 1960s. “I do not want to be too idealistic. There are many problems that Buddhist communities must face—unhealthy structures, unwise practices, misguided use of power, and so forth. Still, something new is happening on this continent,” he wrote in 1998.

Buddhism is being deeply affected by the spirit of democracy, by feminization, by shared practice, and by the integration of lay life. A North American vehicle is being created. Already this vehicle draws on the best of the roots, the trunks, the branches, the leaves, the blossoms, and the fruit—all the parts of Buddhism—and it is beginning to draw them together in a wise and supportive whole.8

IMS and Spirit Rock are teaching, retreat, and training centers that have produced a second generation of instructors now at work in a wide range of independent centers. There are no estimates of the number of people who participate in the movement, but Theravada-based meditation centers doubled in number between 1987 and 1997, from 72 to more than 150.9 A few are affiliated with immigrant temples and others with Asian lay teachers working in this country, but the mainstream of the movement is articulated by the teachers of IMS and Spirit Rock, their students who have become teachers, and other lay Americans who have trained in south and southeast Asia. Overall, Insight Meditation maintains a low institutional profile. Many of its centers are “living room sanghas” with fewer than twenty-five members. Spirit Rock has developed a Kalyana Mitta (Spiritual Friends) Network of small dharma support groups that sustain contact among practitioners in informal and intimate settings. The most important institutional form in the movement is the retreat, whether held for one day, a weekend, or three months. Retreats are usually held in silence and involve sitting and walking meditation, periods of work practice, and a sermonlike dharma talk by the retreat leader. The Cambridge Insight Meditation Center has developed a unique form called the “sandwich retreat,” which consists of five weekday nights of practice “sandwiched” between two weekend-long intensive sessions.

Inherent in American Buddhist movements like Insight Meditation and Zen is a creative tension that gives them much of their appeal and dynamism. On one hand, the primary inspiration for their practice is Buddhist monasticism, an intrinsically elite undertaking due to the rigorous, lifelong demands of monastic discipline. On the other hand, laity must necessarily accommodate their commitment to practicing the dharma to the demands of householding. This combination of monastic practice and lay lifestyle is not a strictly western or American phenomenon, but it strongly influences the way converts are shaping distinctly American forms of Buddhism. An important question, however, is whether lay-based practitioners can seriously pursue the extraordinary goal of enlightenment, which throughout most of Asian history was done by monks and nuns living in celibate monastic communities. For some American Buddhists, this is no real problem. Adjustments in the dharma made to accommodate lay practitioners are seen as setting American Buddhism on an egalitarian foundation. For others, however, such a leveling of practice poses a threat, however unintended, to the integrity of the original teachings of the Buddha.

Joseph Goldstein addressed some of these questions as they arose among Insight Meditation teachers in the early 1990s, at a time when mid-course corrections were being made in the movement. Unlike many, he considered this a serious issue facing lay American Buddhists. “As householders we’re busy and we have a lot of responsibilities, and the work of dharma takes time. The view that it [householding] is as perfect a vehicle as monasticism doesn’t accord with what the Buddha taught. He was very clear in the original teachings that the household life is ‘full of dust.’” Goldstein questioned whether Americans were maintaining the excellence of the Buddha’s teachings. “I wonder whether we, as a generation of practitioners, are practicing in a way that will produce the kind of real masters that have been produced in Asia. I don’t quite see that happening.” In a specifically Buddhist context, he was raising an issue that American Protestants have long called declension, the gradual loosening of doctrine and practice over successive generations. “I wonder how much connection there will be to an authentic lineage of awakening in another twenty years. The amount of time that people spend training to be a teacher is getting less and less,” Goldstein observed.

In Asia, people will often practice for as many as ten or twenty years before teaching. Most of us who came from practice in Asia to the West started teaching much sooner than that, but it was still after a substantial period of training. There are people teaching now who have practiced for only a few years.10

The Monastic-Led Middle Range

One end of the Theravada spectrum is grounded in the traditionalism of the immigrant community; the other is the more innovative movement among converts associated with IMS and Spirit Rock. But there is also a range of people and places that blur the lines between these two communities and may in the long run provide creative examples for the development of a full-bodied and fully American Theravada Buddhism. Some of these are what Paul Numrich called “parallel congregations,”11 small groups of American converts who study and practice Buddhism with monks at immigrant temples, while remaining largely aloof from the cultural life of the immigrant community. Other examples are found among some leaders in the Insight Meditation movement, who are continually reexamining the relationship between traditional monastic practice and the spiritual needs and desires of the American lay community. But the most concrete expressions of this middle range are found where a number of Asian and European American monks are working from monastic foundations but extending themselves beyond the boundaries of ethnic communities.

A number of Asian-born, university-educated bhikkhus are important teachers and leaders in the broad reaches of the American Buddhist community. One of these is Henepola Gunaratana, a Sri Lankan monk who leads the Bhavana Society, a practice center located in the Shenandoah Valley of West Virginia, based on Theravada monasticism but incorporating American adaptations. Born in Sri Lanka in 1927, Gunaratana was ordained at the age of twelve, trained as a novice for eight years, and then took full ordination as a bhikkhu. After completing his education, he left Sri Lanka to work as a missionary in India and then as an educator in Malaysia. He first came to the United States in 1968 to serve at the Buddhist Vihara Society in Washington. Once there, he earned an M.A. and Ph.D. in philosophy at American University, where he served as Buddhist chaplain, and taught courses on Buddhism at Georgetown, the University of Maryland, and elsewhere. In 1980, he was appointed the president of the Buddhist Vihara Society. In 1982, he founded the Bhavana Society, for which he served as president. During the 1990s, he was a prominent figure in the Insight Meditation movement overseas.

The Bhavana Society is a residential retreat center for both laypeople and monastics, where Gunaratana leads a small core group of Asian, American, and European monks and nuns. Visitors on retreat can undertake intensive meditation, study the Buddha’s teachings as applied to daily life, or engage in the kind of meritorious work traditionally associated with laity. Vinaya regulations are central to practice, but are modified when necessary. Monks and nuns drive cars and shop when no one else is available to do it and work side by side, which, by southeast Asian standards, is considered innovative. Gunaratana favors reestablishing the bhikkhuni lineage and granting full ordination for women, but thinks that this practice will first take root in the United States and only then gain wide acceptance in south and southeast Asia.

Gunaratana sees the United States as providing an opportunity for making adjustments in practice because Buddhism is still so new here, but he is by no means an avid Americanizer. Unlike some in American Theravada circles, he does not support monks and nuns abandoning their robes as a means of adapting the vinaya to this country. He sees monastic dress as protecting monks from worldliness and reminding them of their religious duties. He is also critical of how some Americans attempt to cultivate serious practice while ignoring the Buddha’s teachings about craving and the passions by continuing to engage in casual sexual activity. “Every rule prescribed by the Buddha is for our own benefit. Every precept we observe is in order to cleanse the mind. Without mental purification, we can never gain concentration, insight, wisdom, and will never be able to remove psychic irritants.” He also considers highly problematic the way America and its free-wheeling, materialistic lifestyles are transforming values overseas. “America is still like a teenager, a juvenile, just trying to grow, and that spiritually immature state has been taken as a standard for the whole world to follow. I don’t think that is a healthy way of thinking.”12

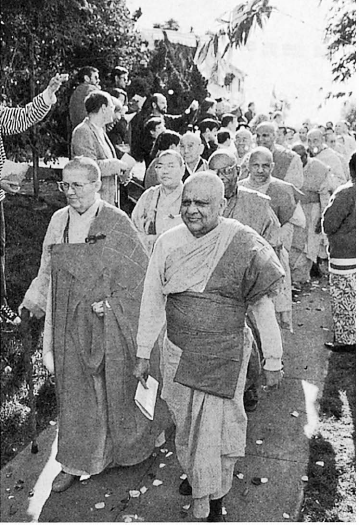

Havanapola Ratanasara, a Sri Lankan American monk, is a Theravada leader who works among the various Buddhist communities in the United States. He is shown here with Karuna Dharma, said to be the first American woman to receive full bhikkhuni ordination, during an ecumenical ordination ceremony at the International Buddhist Meditation Center in Los Angeles. DON FARBER

Havanpola Ratanasara is also a university-educated bhikkhu working in the broader American Buddhist community. A Sri Lankan monk who resides in Los Angeles, he is largely associated with a series of local, regional, and national institutions that have pioneered Theravada educational and ecumenical initiatives in this country. Ratanasara entered the monastic order in Sri Lanka at the age of eleven. Much later he received a B.A. degree in Pali and Buddhist philosophy at the University of Ceylon, then attended Columbia University and the University of London, where he earned a Ph.D. in education. After teaching education and Buddhist Studies in Sri Lanka, he was appointed delegate to the twelfth General Assembly of the United Nations in 1957, the first Buddhist monk to hold such a position. Ratanasara emigrated to the United States in 1980, and he was among the founders of Dharma Vijaya Buddhist Vihara, one of the earliest Theravada temples in Los Angeles.

Ratanasara’s many different administrative hats give an indication of his work both within and among American Buddhist communities. He helped to found the Interreligious Council of Southern California, a path-breaking ecumenical organization, and served as its vice president. He has been president of the Buddhist Sangha Council of Southern California, an organization founded in 1980 in an effort to mediate disputes between monks and laity in a local temple. Since that time, the Sangha Council has sponsored inter-Buddhist celebrations of Vesak and participated in a wide range of interreligious initiatives in southern California. Ratanasara later played a key role in the formation of the American Buddhist Congress (ABC), an organization devoted to many of the same goals as the Sangha Council, but on a national scale.

Ratanasara is also the president of the College of Buddhist Studies in Los Angeles, which was founded by the Sangha Council in 1983. The College provides opportunities to study Buddhism from a nonsectarian point of view and at a depth that cannot be provided by individual temples. Its curriculum is designed to promote understanding among different schools and traditions that find themselves in close proximity in this country, many for the first time in Buddhist history. As part of an overall effort to Americanize the dharma, Ratanasara is working to steer Buddhism in progressive directions, but from a position grounded in traditional monasticism. Together with other monks in Los Angeles, he has been reviving full ordination for women. Only fully ordained nuns can ordain other women, so the reestablishment of a Theravada lineage requires cooperation with those Mahayana Buddhist traditions whose women’s lineages have not become extinct. To this end, Ratanasara played a prominent role in initiating ecumenical ordination ceremonies in this country involving monks and nuns from a wide range of national traditions.

Ajahn Amaro and Thanissaro Bhikkhu are two European American monks who represent a tradition of forest ascetics that has been a powerful religious reform movement in southeast Asia. Both are fully ordained and observe the regulations of the Theravada monastic vinaya, although they have different institutional affiliations and attempt to adapt traditional practices to the American Buddhist community in somewhat different ways. Both began to develop significant public profiles in the broader convert Buddhist community in the 1990s. Amaro was among the few Theravada monastics to teach regularly on the Insight Meditation circuit, an effort motivated in part by his interest in exposing Americans to the monastic lifestyle. Thanissaro taught at the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies, associated with IMS, and became well known as the author of a number of scholarly books, including The Mind Like Fire Unbound and The Buddhist Monastic Code, and as the translator of meditation guides written by Asian teachers in the forest tradition.

Ajahn Amaro was instrumental in creating a forest monastery in northern California, which is the center of a largely lay, convert Buddhist community based in the San Francisco area. Born in England in 1956, he traveled to Thailand after graduating from the University of London and began to study and practice at Wat Pah Nanachat, a forest monastery established for western students by Ajahn Chah, a monk in the Mahanikaya order and a teacher in the forest lineage. Amaro was ordained in 1979 and later returned to England, where he became associated with Chithurst and Amravati monasteries, two forest tradition centers. During the early 1990s, he began to make teaching trips to northern California, where he developed a circle of friends and students interested in building a community around the monastic practices of the forest tradition.

At about this time, Hsuan Hua, a Chinese Mahayana teacher and founder of the California City of Ten Thousand Buddhas (see chapter 10), donated 120 acres of undeveloped land in Mendocino County to Amravati Monastery for use as a forest retreat, with the aim of fostering ties between the Mahayana and Theravada monastic communities. In turn, Amravati assigned stewardship of the land to the Sanghapala Foundation, a California lay organization, with a mission to develop it into a forest retreat center eventually named Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery. In the mid- to late ’90s, Abhayagiri became the center of a Buddhist community in a lineage that ran from Ajahn Chah through Chithurst and Amravati in England to northern California. Amaro was named its abbot, an office he has shared since 1997 with Ajahn Pasanno, a Canadian with a long record as a teacher and leader in the movement. For a number of years, Abhayagiri has run annual, long-term winter retreats for monastics that, in keeping with tradition, have been supported by the efforts of American laity.

Thanissaro Bhikkhu went to Thailand in the early 1970s after graduating from Oberlin College. He began to practice meditation with Ajaan Fuang Jotiko, a teacher in one of a number of Thai forest lineages; took monastic ordination in 1976; then continued to study and practice in Thailand after his teacher’s death in 1986. In 1991, he relocated in California, where he helped to establish Metta Forest Monastery (Wat Mettavanaram or more simply Wat Metta) in the mountains north of San Diego, where he is known as Ajaan Geoff. Under the spiritual direction of a senior Thai monk in the Dhammayut order, Thanissaro has served as the abbot of Wat Metta since 1993. Unlike Abhayagiri, Wat Metta is a part of the larger Thai Buddhist institutional network in this country.

In some respects, Wat Metta functions like other American Buddhist retreat centers by offering short-term, residential practice sessions on major holiday weekends and short- and long-term retreats on an individual basis. But Thanissaro has emphasized forming a stable monastic community, so Wat Metta also serves as a devotional and practice center for Thai and Laotian Americans living in the surrounding area and for convert Buddhists, many of whom are affiliated with regional meditation groups such as the John Wayne Dhamma Center and the San Diego vipassana community. In keeping with the orthodox tenor of the forest tradition, Ajaan Geoff and the other monks live strictly in accord with the vinaya. As a consequence, Wat Metta is run by the principles of a gift economy. Laity contribute what they can to its maintenance, while monks give freely of their teachings. Ajaan Geoff regards this as an important alternative to the retreat model, which is often based on the payment of fees. “There is no way that the dharma can survive as a living principle unless it can be offered and received as a gift,” he wrote in Tricycle. A gift economy creates an “atmosphere where mutual compassion and concern are the medium of exchange, and purity of heart the bottom line.”13

Thanissaro made a conscious decision not to join the circuit of teachers in the Insight Meditation movement. This was due partly to his commitment to a monastic way of life at Wat Metta, and to his own conviction that Theravada practice requires a sustained rigor not readily available in the retreat center mode. Moreover, he sees the critical importance of establishing a wilderness tradition in the United States. “Buddhism has always straddled the line between civilization and the wilderness,” he wrote in 1998. “The Buddha himself was raised as a prince, but was born in the forest, gained Awakening in the forest, and passed away in the forest.”

Over the centuries, many courageous men and women have rediscovered the dharma by going to the forest. The dharma has survived not simply by adapting to a host culture but also by standing apart from it—and the wilderness has been a place to stand apart. It teaches many of the personal qualities—heedfulness, ingenuity, resilience, and harmlessness—that are needed for finding the dharma in the heart and mind.14

Given its wide range of expressions, the Theravada tradition is in an excellent position to make long-term contributions to the formation of American Buddhism. Its unique strength rests in the many different avenues through which it is approaching Americanization—the extensive network of immigrant temples, the strong practice movement associated with IMS and Spirit Rock, and the monastic-led institutions in between. All these approaches, however, do not amount to a concerted effort; a wide range of questions face people in the different strata of the community.

Monastic-led communities and groups must address issues such as the nature of the monks’ role in American society, to what degree the vinaya should be altered to suit the American context, and the desirability of forging ecumenical ties with other forms of Buddhism. Lay immigrants must continue to wrestle with the myriad complexities of communicating their tradition to their children and grandchildren. It is doubtful that Asian Americans or European Americans will soon choose to seek full ordination in significant enough numbers to create a native-born monastic sangha. Therefore, Asian monks are certain to remain prominent for a number of generations, providing living links to tradition and slowing any tendencies toward wholesale Americanization.

Lay leaders of the Insight Meditation movement will have to continue to weigh questions about how to make Buddhism accessible to a middle-class constituency while maintaining the depth of their teaching. They also need to develop sufficiently strong institutions and a lineage-like mechanism between teachers and students to attract and sustain another generation, comprised of either their own children or a new wave of American seekers.