Between 1960 and the turn of the century, immigrants and converts wrestled with questions from how to incorporate temples in accord with American law to the economics of sustaining dharma centers and the education and training of subsequent generations. But the most extensive public discussion about how to adapt the dharma to America and its ideals took place among converts, who saw the emergence of the first generation of native-born teachers in the 1980s as signaling the coming of age of their community. An examination of three issues—concerns about gender equity, the means of orienting Buddhism to social issues, and religious dialogue between Buddhists and non-Buddhists—gives a sense of some of the forces at work in the creation of New World Buddhism in the last decades of the twentieth century.

A drive for gender equity among Buddhists over the course of the 1980s and ’90s reflected the egalitarian idealism associated with the 1960s as it continued to play out within the convert community. Women have played significant and diverse roles in the transmission of Buddhism to the United States from the start. One of the earliest, Helena Blavatsky, put her own idiosyncratic stamp on the dharma before transforming it into a popular and important alternative religious movement. Others played supporting roles, such as Mrs. Alexander Russell, an American housewife who hosted Shaku Soyen on one of his American tours. Ruth Fuller, a central figure in the Sokei-an circle in New York in the 1930s, was among the first Americans to travel to Japan and practice in Zen monasteries. A few decades later, women like Ruth Denison and Jiyu Kennett, founder of California’s Shasta Abbey, studied in Asia and were authorized to teach well before Buddhism turned into anything resembling an American mass movement. But between the ’60s and the ’90s, American women became a major force as practitioners and as teachers, intellectuals, and leaders in ways quite different from women in Asia. Virtually all commentators within the Buddhist community now note that one hallmark of American Buddhism is the way in which the dharma is being transformed in terms of gender equity.

Concern about equity became particularly acute in the wake of a series of scandals, beginning around 1980, that rocked those convert communities most closely associated with the counterculture. The nature and extent of those scandals remains in question. Some people maintain that sexual improprieties, the excessive consumption of alcohol and drugs, and abuse of power were widespread, while others see these episodes as isolated incidents. A few events, however, are universally recognized as amounting to gross negligence. For instance, a bisexual American teacher in a Tibetan Buddhist community engaged in unprotected sex for three years, while knowingly infected with the virus that causes AIDS.

These scandals had a number of important consequences for the development of convert Buddhism. To some extent, they were leadership crises that occurred as the free-wheeling, no-holds-barred spirit of the 1960s and ’70s ran aground on the conservative mood of the Reagan years. Some commentators within the community saw them as a healthy dose of cold water for Americans whose pursuit of transcendence through psychedelics, sex, and meditation had obscured more fundamental concerns like mental health and a sense of responsibility. The scandals helped bring to an end the countercultural era in American Buddhist history and the ill-conceived attempt, inherited in part from the Beats, to wed the dharma to experiential excess.

As important, these events dashed overly romantic assumptions about Asian religions held by a generation of western students. Many began to criticize what Kathy Butler, a long-time practitioner at the San Francisco Zen Center, called “an unhealthy marriage of Asian hierarchy and American license that distorts the student-teacher relation.”1 They saw how dharma centers had often operated like dysfunctional families, with power and control issues swept under the rug in the name of collective spiritual discipline, a situation Butler called “a lineage of denial.” “When our teacher kept us waiting, failed to meditate, or was extravagant with money, we ignored it or explained it away as a teaching,” she wrote in 1990, comparing this behavior to what alcoholism counselors call enabling.

A cadre of well-organized subordinates picked up the pieces behind him, just as a wife of an alcoholic might cover her husband’s bounced check or bail him out of jail.… It insulated our teacher from the consequences of his actions and deprived him of the chance to learn from his mistakes. The process damaged us as well: We habitually denied what was in front of our faces, felt powerless and lost touch with our inner experience.2

The ensuing controversies had important institutional consequences. The San Francisco Zen Center established democratic mechanisms for leadership and guidelines for teacher/student relations, and other organizations soon followed suit. Disaffected journalists from a variety of traditions founded independent outlets for the expression of their opinions, most significantly Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. In its premiere issue in 1991, a lead article cut to the chase on a central issue—authority and exploitation—by featuring a conversation among Robert Aitken; David Steindl-Rast, a Catholic monk; and Diane Shainberg, a psychotherapist who used Buddhist teaching in her practice. The three discussed “the tension inherent between egalitarian imperatives and the authority required in order to pass on spiritual teaching.”3 Their conversation focused on how many students brought to practice hopes for a mystical transformation, the ease with which these hopes could be exploited, and the need for centers to operate like healthy families. In the often emotion-charged atmosphere of the practice center, Aitken noted the need “to establish a ground of trust in the milieu between teachers and students.… Good teachers have, by and large, recognized that the sangha is a family and that the teacher has an archetypal place in that family as father or mother, and that sexual betrayal, seduction of a student by a teacher, is incest.”4

The scandals and controversies also hastened the Americanization of Buddhism, even as they raised questions about what Americanization was to mean. The pain many felt in the wake of events made clear that meditation might not address intimate issues such as childhood wounding, guilt, and low self-esteem, a realization that encouraged some to increasingly identify the dharma with psychotherapy. Some began to call into question the goal of Buddhist practice. To achieve total liberation? To become self-realized? Healthy-minded? Or simply stress-free? As a result, the emphasis in much of convert Buddhism shifted from a 1960s-era preoccupation with transcendence to the safer ground of ethics. “Enlightenment—oddly enough—has become all but a dirty word among American Zennists,” wrote Helen Tworkov, editor of Tricycle, in 1994.

The quest for enlightenment has been derided of late as the romantic and mythic aspiration of antiquated patriarchal monasticism, while ethics has become the rallying vision of householder Zen. To pursue the unknowable state of enlightenment is now often regarded as an obstacle to practice that emphasizes “everyday Zen,” a state of mindful attention in the midst of ordinary life.5

More to the point here, the scandals served as a wake-up call for women by setting their quests for transcendence through meditation in a gender-political setting. Throughout the 1970s, women had been active in the community as leaders, teachers, and students. But they now had a context in which to make sense of negative experiences. Affairs with teachers, whether devastating or merely problematic, could be examined in terms of the power implicit in teacher-student, male-female, and often Asian-European American relationships. The discomfort they experienced in some practice centers, where the atmosphere was militant if not militaristic, could be understood as coming from male-centered practice regimes created by teachers trained in hierarchical monastic traditions who had little or no experience teaching women. Many women also saw clearly the secondary roles they often played in running dharma centers and the deference expected of them by male teachers as evidence of a more or less consistent secondary status.

The liberation ethos inherited from the ’60s, the reaction to the scandals, and the power of feminism in the broader culture coalesced in the 1980s to place gender equity at the top of the agenda in the convert community. This development was most conspicuous in Zen centers and in the Insight Meditation movement, where overt Americanizing tendencies had been strongest from the outset. But the ideal of gender equity infused most of the convert community over the course of the 1980s and 1990s, a good deal later than in the more progressive quarters of American Judaism and Christianity.

Soon Buddhist gender commentary, written with an eye to the emotional and spiritual needs of Americans, emerged as practitioners experienced in dealing with issues of sexuality and women’s spirituality turned their critical attention to Buddhism. One ground-breaking study was Turning the Wheel: American Women Creating the New Buddhism, published by Sandy Boucher in 1988. Boucher, a long-time feminist activist, lesbian, and author familiar with many forms of women’s spirituality, was introduced to Buddhist practice in 1980 by Ruth Denison at Dhamma Dena. In Turning the Wheel, she looked at ways in which women, both heterosexual and lesbian, were practicing Buddhism in a wide variety of traditions and communities, helping to uncover the diversity of women’s involvement with American forms of the dharma. She also began to catalogue the kind of issues that became important to women in the wake of the scandals—the problems they encountered with male teachers; the distinct modes and styles of practice and teaching they pursued; and the unique character of women-led practice centers.

Turning the Wheel helped to set in motion a broad and highly varied exploration of women’s unique contributions to American Buddhism, in books from Lenore Friedman’s Meetings With Remarkable Women: Buddhist Teachers in America to Karma Lekshe Tsomo’s Buddhism Through American Women’s Eyes and Marianne Dresser’s Buddhist Women on the Edge: Contemporary Perspectives from the Western Frontier. In 1997, Boucher published Opening the Lotus: A Women’s Guide to Buddhism, in which she gave voice to a form of liberal, feminist Buddhism practiced by many Americans, both men and women, in the ’90s, and provided a resource guide for women’s practice centers and teachers.

A different kind of gender-related commentary also began to emerge, from the academic side of the American Buddhist community. This work by Buddhologists helped to deepen the commitment to gender equity by acquainting Americans with relevant developments in the great sweep of Asian Buddhist history. It resembled the kind of scholarship on gender that had begun to play an important political and religious role in Judaism and Christianity several decades earlier, one that eventually made an impact on religious communities at the grassroots. In a similar fashion, the effects of academic gender studies of the Buddhist tradition were first felt in college and university religion departments and in liberal divinity schools, but soon stimulated a lively discussion about gender, tradition, and innovation in many Buddhist practicing communities.

José Ignacio Cabezón, gay activist, former monk, and professor of Buddhist philosophy at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver, published a pioneering collection of edited essays, Buddhism, Sexuality, and Gender, in 1992. These were representative of the kind of historical and textual work done by scholars of religion to elucidate a wide range of gender-related issues. More important, the authors in the volume implicitly related historical questions about the bhikkhuni sangha in tenth-century Sri Lanka, homosexuality in Japanese monasticism, the complex gender symbolism of the bodhisattva Kuan Yin, and other topics to contemporary issues related to gender in the American Buddhist community. On one hand, this kind of writing encouraged innovation by giving American Buddhists a deep sense that Asian Buddhism was not only a timeless set of truths and practices but also a richly varied, politically constructed creation of human history. On the other hand, it also helped, in a way quite different from that of Japanese roshis or Tibetan lamas, to orient Americans to Asian traditions by suggesting that Old World flaws and shortcomings might be rectified in a New World setting.

Other academic studies more specifically designed to advocate innovation began to appear at about the same time. Buddhism After Patriarchy by Rita Gross, a student of Chogyam Trungpa, was published in 1993. It closely resembles early feminist work in Judaism and Christianity insofar as it is a sweeping interpretation of the history of a tradition in search of a usable past for contemporary women. On the down side, Gross found that Buddhism reflects the patriarchal values found in most Asian societies, a tendency expressed in the Buddha’s reluctance to allow women to enter the original monastic sangha. Later monastic precepts and practices, particularly those concerned with the control of passions, created erotic stereotypes about women. The power of men in the sangha meant enduring social and institutional inequities for Asian women. On the positive side, Gross found many advantages for women in Buddhism. Its nontheistic character means that there is no creator, father, and judge as in Judaism and Christianity, a form of anthropomorphism often identified as a source of oppressive attitudes and practices toward western women. Gautama, the model for Buddhist practice, was not a divine son like Jesus, but a human teacher. There are, moreover, many powerful historical women and female bodhisattvas and dharma protectors in Buddhism whom Gross identified as models for the cultivation of women’s spirituality, even though they were embedded in patriarchal social orders. Many Buddhists considered Buddhism Beyond Patriarchy highly controversial, but it helped to do for American Buddhism what Mary Daly’s Beyond God the Father had done for American Christianity two decades before, which was to throw open the door to the critical and creative appropriation of religious history by American women.

The early work of Cabezón and Gross helped to set a precedent for a wide range of later studies by academics or those writing in an academic vein. Some of these address the historical and political situation of women in Buddhism, such as Susan Murcott’s The First Buddhist Women: Translations and Commentaries on the Therigatha, Miranda Shaw’s Passionate Enlightenment: Women in Tantric Buddhism, and Tessa J. Bartholomeusz’s Women Under the Bo Tree: Buddhist Nuns in Sri Lanka. Others more directly explore the interpretive possibilities of Buddhism for contemporary American women, including Ann Klein’s Meeting the Great Bliss Queen: Buddhists, Feminists and the Art of the Self.

Most of these developments can be traced more or less directly to the powerful reaction to the scandals in convert communities closely associated with the counterculture. But a similar concern with gender was no less important in another major convert community, Soka Gakkai International-USA, even though it emerged under less dramatic circumstances and drew less publicity.

In the early years of Nichiren Shoshu of America, Japanese women played a critical role in the success of shakubuku campaigns. The national organization was from the outset organized in Men’s and Women’s Divisions, which ensured that many women held important local and national leadership positions. But since the early 1990s and the schism, SGI has increased its efforts to eliminate patterns of deference inherited from Japan, such as Japanese women’s tendency to defer to males as leaders of the chant. In the past decade or so, moreover, five women have joined 16 men as Vice General Directors. Gender parity is, like many other innovations in SGI-USA, a work in progress, cross-cut by issues related to race and ethnicity in unique ways. Given America’s multicultural society, domestic race and ethnicity issues are major considerations in the advancement of women leaders. But the international Soka Gakkai movement has been historically dominated by the Japanese. At present, only one American Caucasian, a male, serves on the Board of Directors of SGI-USA, along with six Japanese men. In other countries, national SGI leaders are also often Japanese, but a number of them are women.

In any case, by the 1990s it was apparent that the ideal of gender equity was becoming one of the most important touchstones in the cross-cultural transmission of the dharma in convert communities. Some observers suggested that most serious convert Buddhists, in whatever school or tradition, were women. More important, the highly varied ways women were practicing and living the dharma—as monastics or lay teachers, intellectuals, institutional leaders, or cultural critics—was a main influence on the adaptation of Buddhism to the unique cultural climate of the United States.

A few examples suggest the widely varied roles played by women in convert communities. Ji Ko Linda Ruth Cutts began practicing zazen at the San Francisco Zen Center in 1971 and eventually became an ordained Zen priest in the Suzuki Roshi lineage. She has served as tanto, or leader of practice, at Green Gulch Farm, where she lives with her husband and two children. Jan Chozen Bays, a successor of Maezumi Roshi and a wife, mother, and pediatrician working with abused children, teaches in Oregon. She continues to study Zen with Shodo Harada Roshi, a Rinzai master and abbot of Sogenji Monastery in Japan, and also leads two Oregon sanghas, a city zendo in Portland, and a country training center in the mountains to the east. Most members of these two sanghas are laity with families, so Bays devotes much of her teaching to practice issues related to work and family. But she is increasingly interested in establishing a center in the northwest for monastic-style, residential Zen training.

Yvonne Rand, a teacher and priest in the Soto Zen tradition for more than thirty years, now incorporates elements of vipassana and Tibetan Buddhism into her teaching. She is particularly known for her focus on reproductive issues and, like many Buddhist women, describes herself as anti-abortion and pro-choice. Inspired by the bodhisattva Jizo, a popular figure in Japan associated with the death of infants, she has developed a simple American Jizo ceremony as a way to cultivate awakening in the midst of the guilt, grief, and pain accompanying abortions, stillbirths, and miscarriages. Despite her own Buddhist convictions regarding taking life, she has written that “My experience as a Buddhist priest continues to teach me that looking into a situation in detail, without glossing over what is unpleasant or difficult, is what helps us to stay present and clear and to break through ignorance. This is certainly true in the potent realms of sexuality, fertility, and gestation.”6

Women are among the leading creative intellectuals in the convert community, and the different ways they understand the dharma epitomize the increasingly diverse range of opinion found there by the end of the twentieth century. Joanna Macy is primarily known as a philosopher and social activist. She is a professor at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley and the California Institute of Integral Studies, and her Mutual Causality in Buddhism and General Systems Theory and World as Lover, World as Self are regarded by many as important works of American Buddhist philosophy. Over the decades, she has also worked with Tibetan refugees, in the Buddhist-inspired Sarvodaya Movement in Sri Lanka, and in “despair work,” writings and workshops for disillusioned social activists. Her career is more fully profiled in the next chapter.

bell hooks, a long-time Zen practitioner and professor of English at the City College of New York, is widely known as a feminist theorist and cultural critic. She is also a commentator on the implicit racism in many convert circles, which tends to relegate both African Americans and ethnic Asian immigrants to the margins of the community. hooks is particularly inspired by Thich Nhat Hanh, whose Buddhism she sees as grounded in the anguish of the Vietnam War, rather than in Americans’ restless quests for personal transformation. “In the United States there are many black people and people of color engaged with Buddhism who do not have visibility or voice,” she noted in a Tricycle interview in 1994. “Surely it is often racism that allows white comrades to feel so comfortable with their ‘control’ and ‘ownership’ of Buddhist thought and practice in the United States. They have much to learn, then, from those people of color who embrace humility in practice and relinquished the ego’s need to be recognized.”7

Joan Halifax is among those working to integrate the dharma with the shamanic traditions of Native Americans and of other tribal peoples. During the 1990s, her primary dharma teaching was related to death and giving care to the dying. But over the course of several decades, she also developed an interpretation of Buddhist ideas about the interdependence of all beings in light of the mythological studies of Joseph Campbell, the traditions of the Huichol Indians of Mexico, and the Buddhist teachings of Seung Sahn and Thich Nhat Hanh. “In Buddhism, the term sangha refers to the community that practices the Way together,” she wrote in The Fruitful Darkness: Reconnecting with the Body of the Earth in 1993. “I ask, Where is the boundary of that community?”

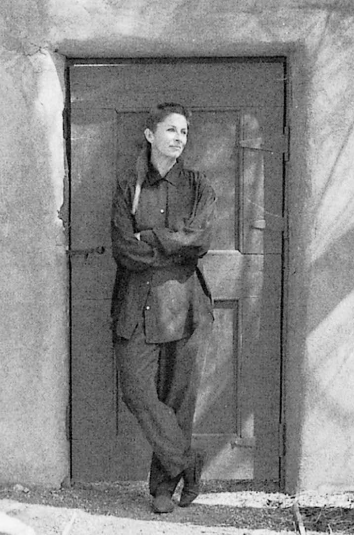

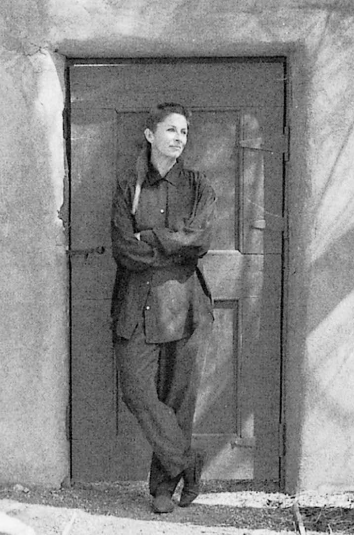

Women have always been a creative force in American Buddhism and, since the early 1980s, have come to hold a wide range of prominent positions as leaders and teachers, whether as fully ordained nuns or as laypeople. Joan Halifax, founder of the Upaya Institute in New Mexico, has been ordained in three different Zen lineages and incorporates many New World themes in her Buddhist teaching and writing.

RON COOPER/COURTESY JOAN HALIFAX

The frontier of the community, extending beyond the human being, includes the sacred mountains that surround our homeland, the rocks and springs that have given birth to civilizing ancestors. The eagle, bear, buffalo, and whale—wisdom beings of Sky and Earth.… And from a Buddhist perspective, this community is alive, all of it, and practices the Way together.8

The drive for gender equity in American Buddhism was also expressed with regard to gay and lesbian issues, the importance of which was magnified in the ’90s as questions about how to relate alternative sexual identities to religious traditionalism became increasingly divisive. Residual homophobia continues to exist in dharma centers, but Buddhist gay men and lesbian women have been integrated into the social fabric of many different Buddhist communities as monks, nuns, and laypeople. The AIDS crisis served as the occasion for many Buddhists, both gay and straight, to become more frank and forthright about gay and lesbian perspectives on gender issues. This resulted in the creation of service organizations such as the White Plum Buddhist AIDS Network under the direction of Pat Enkyo O’Hara, sensei of the Village Zendo in New York City, and the Zen Hospice Project in San Francisco. It also fostered the creation of gay and lesbian practice groups such as New York’s Maitre Dorje, and the Hartford Street Zen Center and the Gay Buddhist Fellowship in San Francisco.

The AIDS crisis also encouraged some Buddhists to use more traditional devotional expressions to address the religious needs of the gay community. At Kunzang Palyul Choling, a Nyingma Buddhist Temple in Poolesville, Maryland, resident monks and nuns performed phowa services in the late 1990s for those who died of AIDS. The goal of phowa is to merge consciousness at the time of death with the wisdom mind of the Buddha. It is a visualization technique used to attain enlightenment without a lifelong experience of meditation practice.

In June 1997, a meeting between gay and lesbian Buddhists and the Dalai Lama brought some of the institutional challenges of adapting tradition in the name of gender equity into unusually high relief. The meeting was held at the request of Buddhist activists, who asked for a clarification of remarks made by the Dalai Lama about sexual misconduct in two of his books, The Way to Freedom and Beyond Dogma. The activist delegation, which included Cabezón, Lourdes Arguelles of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship, and Steven Peskind, co-founder of the Buddhist AIDS Project, expressed two distinct concerns. The first was related to the Dalai Lama’s stature as a Nobel Laureate and preeminent human rights leader, and how his views regarding gay rights issues might be interpreted by the public. The second was more strictly religious. How are gay and lesbian Buddhists to reconcile their personal identity with their religious identity if same-sex behavior is considered a violation of the Buddha’s teachings?

The different responses of the Dalai Lama, first as a human rights advocate and then as a Buddhist monastic and leader, exemplify the complex challenges involved in balancing progressive American ideals with tradition-based religious orthodoxies. As far as human rights were concerned, the Dalai Lama took an unambiguously pro-gay position. “It is wrong for society to reject people on the basis of their sexual orientation,” he is quoted as saying. “Your movement to gain full human rights is reasonable and logical.”9 According to the San Francisco Chronicle, he added, “From society’s viewpoint, mutually agreeable homosexual relations can be of mutual benefit, enjoyable, and harmless.”10

When he spoke as a leader of a religious tradition, however, the Dalai Lama’s responses were a good deal more complex. He explained that questions about all Buddhist behavioral norms should be considered with reference to the aim of the tradition and practice, which is to eliminate emotional affliction and attachment. In general, sexual desire, one of the greatest sources of attachment, needs to be disciplined by all Buddhists, but especially by those who have taken monastic vows of celibacy, for whom all sexual behavior is considered misconduct. More specifically, Buddhist tradition provides ethical guidelines for all Buddhists in terms of four criteria—place, time, partner, and body organ involved. One place where sexual activity is prohibited is a temple precinct. Proscribed times include during daylight hours and during a woman’s menstrual period. Buddhists should also avoid adultery, having sex with monks or nuns or a same-sex partner, or engaging in sex during late pregnancy. According to tradition, oral sex, anal sex, and masturbation are all sexual misconduct. The Dalai Lama underscored that none of these regulations are directed at gays and lesbians per se, but added that the authority of scripture and tradition were such that even he, head of the Gelugpa school and political and spiritual leader of the Tibetan people, had no power to alter them unilaterally.

By way of conclusion, however, His Holiness also noted that Buddhist traditions had taken shape in ancient India under very distinct cultural circumstances. Throughout Asian Buddhist history, the dharma has been open to interpretation in new settings. He suggested that the delegates begin to build a consensus among American Buddhists in different communities for a new understanding of ancient texts appropriate to a modern, American setting. This effort could be linked to the resolution of other important controversies related to gender, such as the status of nuns and women’s ordination. Whatever the case, the Dalai Lama made it clear that gays and lesbians should rely on general Buddhist principles of tolerance and universalism as a foundation for their struggle for gender equity. Guidelines for conduct are not intended to exclude anyone from the Buddhist tradition and its practice communities.

Press releases and reports described the meetings as relaxed, warm, and cordial, with the Dalai Lama alternately chuckling and roaring with laughter as the delegates attempted to clarify some of the finer points regarding Buddhist ethics and gay and lesbian sexual practices. The delegates were reported to be pleased with both the tone and the outcome of the meetings. Tinku Ali Ishtiaq, co-chair of the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission, noted that “His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s support for our rights is very significant.” Lourdes Arguelles said, “It is always amazing to see how His Holiness rises beyond the culture-bound context of his own tradition and grapples with seemingly absurd proscriptions to focus on the complex needs and desires of human beings in the here and now.” K. T. Shedrup Gyatso, spiritual director of the San Jose Buddhist temple, said, “I am very pleased with what His Holiness had to say. I can now go back to my temple and tell our gay, lesbian, and bisexual members that they are still Buddhists, that they are still welcome, and that they are as well-equipped for the Buddhist path as anyone else.” The discussion, concluded Steve Peskind of the Buddhist AIDS Project, was “twentieth-century Buddhism at its best.”11 By the following spring, however, Peskind was more critical in an interview in the Shambhala Sun: “I was disappointed that he [the Dalai Lama] chose not to speak personally and directly,” he recalled,

beyond Buddhist tradition, to the real harm of some of these misconduct teachings, and their irrelevance for modern Buddhists and others. I wondered, does the Dalai Lama, whom many consider the embodiment of Avalokiteshvara, who “hears the cries of all sentient beings and responds skillfully,” really hear the cries of sexual minority Buddhists?12

The drive for gender equity effected the most conspicuous changes among lay-oriented Buddhist converts, but it also made an impact in formal monastic communities. The vast majority of American Buddhists have not chosen the monastic path. Among those who have, however, are a number of women who are helping to establish the monastic movement in the West and to underscore the importance of women’s contributions to the dharma.

The term nun as descriptive of a woman Buddhist practitioner is, like a great deal of Buddhist terminology, highly ambiguous. To be used with any precision, it must be understood with reference to complex historical developments in Asia. There are three traditional forms of monastic ordination for women. Full ordination (bhikkhunis, or alternatively bhikshunis) became extinct in Theravada countries in the tenth century, was never introduced into Tibet, and has survived only in the Mahayana countries of China, Taiwan, Vietnam, and Korea. Efforts are being made, often in response to prompting by western women, to reestablish the Theravada lineage and to create a Tibetan one by building upon the bhikkhuni lineages that still exist in the Mahayana tradition. A second form, novice ordination, is found wherever bhikkhuni ordination is found, and it is also a part of the Tibetan tradition. Women who have taken it are called sramanerika. Where neither bhikkhuni nor sramanerika ordination exists, women who seek to live a monastic life are referred to by various terms, often as precept-holding nuns in English. Their status varies considerably from country to country, but they are, in a technical sense, neither fully laywomen nor fully monastics.

In the United States, American Buddhist women ordained in one or another lay-oriented lineage may choose to refer to themselves as nuns, on the model of the precept-holding women of Asia. This is more or less standard in American Zen, where, in keeping with the tradition of Japan, women can also be ordained as priests. However, very few American women have taken either bhikkhuni or sramanerika ordination. One of these is Pema Chodron, whose work with Shambhala International was briefly discussed in chapter 7. A mother of two children who recently became a grandmother, she received novice ordination in Scotland in the mid-1970s from the Sixteenth Gyalwa Karmapa and, at his request, received full ordination in a Chinese Mahayana lineage in Hong Kong in 1981.

Thubten Chodron is another woman who has received both ordinations. She is a senior teacher with the Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition (FPMT), an organization in the Gelugpa tradition of Tibet. She began practicing in 1975 with Zopa Rinpoche, one of FPMT’s founders, and received novice ordination in 1977 and full ordination in 1986. She teaches a range of Tibetan practices from the ngondros to Tara sadhanas, Tara being a female bodhisattva of Tibet favored by many American women in the Tibetan tradition. In the late 1990s, Thubten Chodron taught at Dharma Friendship Foundation in Seattle, Washington. She writes: “Ordained life is not clear sailing. Disturbing attitudes follow us wherever we go. They do not disappear simply because someone takes precepts, shaves their head, and wears robes. Monastic life is a commitment to work with our garbage as well as our beauty. It puts us right in front of the contradictory parts of ourselves.” On the power of belonging to a monastic lineage, she writes,

Buddhist teachers often talk about the importance of lineage. There is a certain energy or inspiration that is passed down from spiritual mentor to aspirant. Although previously I was not one to believe this, it has become evident through my experience in the years since my ordination. When my energy wanes, I remember the lineage of strong, resourceful monastics who have practiced and actualized the Buddha’s teaching for 2,500 years. When I took ordination, I entered into their lineage, and the example of their lives renews my inspiration. No longer afloat in a sea of spiritual ambiguity or discouragement, I feel rooted in a practice that works and a goal that is attainable—even though one has to give up all grasping to attain it.13

Karma Lekshe Tsomo has combined an academic career in Asian studies with a life as a fully ordained bhikkhuni and a commitment to Buddhist women’s issues. She received novice ordination from the Sixteenth Gyalwa Karmapa in France in 1977, and five years later received full ordination. During those years she also began to study Asian languages and Buddhist philosophy both in American universities and in Dharamsala, India, the headquarters of the Tibetan government in exile and the monastic residence in exile of the Dalai Lama. In 1987, she helped to found Sakyadhita: International Association of Buddhist Women (Sakyadhita means “daughters of the Buddha”) in Bodhgaya, India, where the Buddha attained enlightenment, at the conclusion of the First International Conference on Buddhist Women. Among its goals are to create a global network of practicing women, educate them to become dharma teachers, provide improved facilities for their study and practice, and help establish communities of fully ordained women where they do not currently exist.

Buddhism provides the opportunity for women from many different traditions and countries to discover each other as they work together for the dharma in organizations such as Sakyadhita. Here Buddhist nuns from a variety of traditions are assembling at Hsi Lai temple in Los Angeles, a major center of the Fo Kuang Buddhist movement in Taiwan.

DON FARBER

Subsequent conferences were held in Bangkok, Thailand; Colombo, Sri Lanka; Leh, Ladakh in India; and Phnom Penh, Cambodia. In 1998, Sakyadhita held its first North American conference at Pitser College in southern California. Its theme was “Unity and Diversity,” and its goals were to encourage dialogue between scholars and practicing Buddhists, provide a forum for discussion of gender and women’s spirituality, create a meeting place for women from different Buddhist traditions, and allow Asian and Asian American women to speak to a broad audience about their experiences in and out of North America.

Through Sakyadhita and other international connections, understanding of women’s issues in America is being informed by the activities of Buddhist women overseas, where the women’s movement has also become powerful. For example, Yifa, a nun in the monastic order of Fo Kuang Buddhism and Dean of Academic Affairs at Hsi Lai University in Rosemead, California, remarked upon the pivotal role played by women in the postwar Mahayana revival in Taiwan. “Why is Buddhism flowering so fragrantly in Taiwan?” she asked before an assembly of Christian and Buddhist monastics in 1996. “One reason is the significant contributions of Buddhist nuns who have also greatly benefited Taiwanese society.” In Taiwan,

Mahayana Buddhist nuns receive higher education, establish temples, give Buddhist lectures, conduct research, transmit Buddhist disciplinary precepts, manage temple economies, as well as manage and participate in various charitable programs.… These nuns have not only reformed the old traditional monastic system, but have also proved to be equal with the male Buddhist practitioner.… They have helped to propel Buddhism into people’s daily lives and thereby to purify Taiwanese society.14

The contemporary gender revolution will continue to influence the creation of uniquely American forms of the dharma. As the liberation ethos that originated in the ’60s developed through the ’70s and ’80s, convert Buddhists began to forge new paths across ancient terrain, not all of which followed the traditional contours of the Asian Buddhist landscape. And there is no reason to think they ought to have, because they are part of an effort to found a New World dharma. Thus, to focus on the drive for gender equity is also to acknowledge the diversity of American Buddhism, in which women and men, straight and gay, monastics and laity are all part of a community where innovation and tradition mingle in complex and often unexpected ways.