WHAT IS BRISKET?

Picture a steer. We’ll call him Sam. Born of Angus stock and weighing 1,400 pounds, Sam just celebrated his 16-month birthday. True, he’s less the man he was at 6 months, when a cowhand relieved him of what we politely call Rocky Mountain oysters, but he’s still a barnyard bad boy. Sam leads a good life, spending his first year grazing on grass under a big Texas sky, rollicking with his buddies. More recently, his diet switched to grain, and Sam feels bigger and stronger than ever. Hey, you know the saying: When a boy fattens up, he gains muscle. When a man bulks up, he gains fat.

Unlike a human being, Sam walks on all fours and, unlike us, he lacks shoulder blades. But he definitely has chest muscles. In a human, they’re known as pecs (short for pectoralis major). In Sam, we call them brisket.

Brisket Anatomy

Actually, two muscles comprise Sam’s brisket. The first is a flat rectangular muscle nestled against Sam’s breastbone under the first five ribs and known as the pectoralis profundus. Butchers and brisket lovers call this the flat.

On top of the flat (but lower and more forward on the steer’s undercarriage) is a second muscle, this one thicker at the shoulder end, thinner at the other, and generously marbled with rich veins of fat. This second muscle, the pectoralis superficialis, goes by the name of the point. (In delicatessen circles, it’s called the deckle; we’ll use the term point throughout this book.) Connecting the two is a thick seam of pearl-white intermuscular fat called the seam fat.

Each of Sam’s untrimmed briskets (he has two—a right and a left) weighs 12 to 18 pounds. This represents just 3 percent of his edible meat, but that 3 percent serves an outsize role in Sam’s well-being. They help Sam move—striding toward food, running away from danger. They enable him to stand up—and get up after he lies down to rest. Most important, they support his not inconsiderable weight—roughly 350 pounds per brisket.

As a result, Sam’s well-exercised briskets have a very different composition, texture, and taste than one of his lazy muscles, such as the psoas major (beef tenderloin) or longissimus dorsi (prime rib). No, the brisket is as bad-boy as its owner. It’s a lot denser and tougher than steak, but when properly cooked, it has a rich, beefy flavor that just won’t quit.

Being such a load-bearing, hardworking muscle, Sam’s brisket is laced with a connective tissue called collagen. Collagen consists of amino acids wound together in triple helixes to form elongated fibers called fibrils. Collagen (named for the Greek word for “glue,” of which it was an early ingredient) gives the brisket muscles their strength but also their toughness when cooked.

On account of this collagen, if you tried to cook Sam’s brisket like a steak—quickly over a hot fire—you’d wind up with a mouthful of shoe leather. That makes brisket a poor candidate for grilling (with one exception—the paper-thin-sliced Korean grilled brisket). But the same collagen makes it an excellent candidate for slow, low, moist-heat cooking methods, like barbecuing, boiling, and braising. (More on that here.)

As you cook a brisket, this tough collagen gradually turns into tender gelatin—a process that begins at around 160°F. At the same time (at around 140°F), the fat starts to render (melt). For both transformations to take place, you have to raise the temperature sloooooooowly; otherwise the meat fibers will contract and toughen. That’s why barbecue pit masters insist that you have to cook brisket “low and slow.”

Brisket History

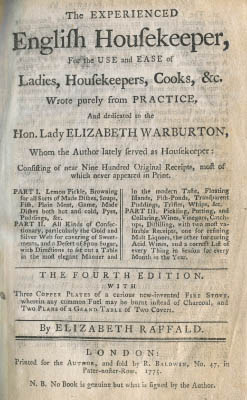

Brisket’s big flavor and historically affordable price have made it a popular meat throughout history. The word bru-kette first appears in an English-Latin dictionary published in 1450. Over the centuries, you could read about brusket, briscat, and brysket. In the seventeenth century, brysket referred to the chest of a horse as well as a steer. (Sam would not be amused.) In 1709, we learn from a period tabloid called The Tattler that the Black Prince (one Edward of Woodstock) was “a professed Lover of the Brisket.” The first printed brisket recipe appears in The Experienced English Housekeeper by a Mrs. Raffald in 1769. (That’s seven years before the founding of the United States! You’ll find the original recipe on the facing page.) In colloquial British English, if you’re angry at someone, you might punch him in the brisket.

The first brisket recipe appeared in this book in 1769.

Beef in the nineteenth century. Talk about smoky!

Pork appears extensively in the culinary literature of Colonial America. Brisket does not. Nor does it surface in the nineteenth century, but here’s how writer Charles Frazier imagines it in his Civil War novel Cold Mountain:

When Ruby finally returned, she carried only a small bloody brisket wrapped in paper and one jug of cider. . . .

Not hardly four pounds, she said. She set it and the jug on the ground and went to the house and came back carrying four small glasses and a cup of salt, sugar, black pepper, and red pepper all mixed together. She opened the paper and rubbed the mixture on the meat to case it, and then she buried it in the ashes of the fire and sat on the ground beside Ada. . . .

After Mars had risen red from behind Jonas Ridge and the fire had burned down to a bed of coals, Ruby pronounced the meat done and dug it from the ashes with the pitchfork. The spices had formed a crust around the brisket, and Ruby put it on a stump butt and sliced it thin across the grain with her knife. The inside was pink and running with juice. They ate it with their fingers without benefit of plates and there was nothing else to the dinner. When they finished they pulled dry sedge grass from the field edge and scrubbed their hands clean.

Brisket’s golden age in America wouldn’t arrive until the twentieth century. First with Jewish immigrants from Romania who pioneered the brine-cured, spice-rubbed, smoked, then steamed brisket we enjoy today as pastrami (see here). (They introduced it at an equally revolutionary new type of restaurant where you could eat it—the delicatessen.) Their Canada-bound cousins branded the preparation “smoked meat” and made it a Montreal sandwich icon (see here). Around the same time, Irish immigrants brought brine-cured, boiled brisket to Boston and New York, where corned beef became an indispensable symbol of St. Patrick’s Day.

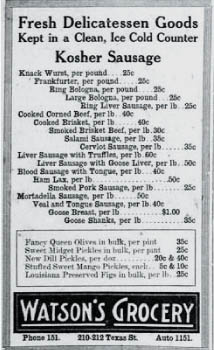

Brisket debuts on a Texas menu. No, it wasn’t barbecue.

THE OLDEST BRISKET RECIPE

Based on linguistic evidence, the English have enjoyed brisket for more than six hundred years. The earliest brisket recipe appeared in a cookbook called The Experienced English Housekeeper: For Use and Ease of Ladies by one Elizabeth Raffald, published by an R. Baldwin in 1769.

It’s a splendid, surprisingly modern preparation that uses bacon to moisten a brisket flat’s inherent leanness. Oysters may seem like an odd touch—until you consider the popularity of Worcestershire sauce (which contains anchovies) and fish sauce, which remain popular brisket flavorings and condiments to this day. Red wine becomes the base for the “gravy” (read: barbecue sauce). They even serve it with pickles, as do twenty-first-century pit masters, to counterpoint the fat.

The only note that would be jarring to modern taste buds is nutmeg—an enormously popular seasoning in eighteenth-century Europe (perhaps because earlier papal authority had proclaimed it a cure for the plague). But nutmeg does turn up in some modern barbecue rubs—used in moderation, it adds a pleasing musky sweetness.

You’ll recognize the method as braising (in red wine), so cook it in a Dutch oven. The instructions are easy to follow; the result is out of this world.

To make Brisket of Beef a-la-royal

Bone a brisket of beef, and make holes in it with a knife, about an inch one from another, fill one hole with fat bacon, a second with chopped parsley, and a third with chopped oysters, seasoned with nutmeg, pepper, and salt, till you have done the brisket over, then pour a pint of red wine boiling hot upon the beef, dredge it well with flour, send it to the oven, and bake it 3 hours or better; when it comes out of the oven take off the fat, and strain the gravy over your beef; garnish with pickles and serve it up.

You may be surprised to learn that Texas-style barbecued brisket is a relatively new phenomenon. Undoubtedly, Texans have been eating brisket ever since Lone Star State pit masters first put meat to fire—but it was part of a barbecued whole animal or forequarter. According to Texas Monthly barbecue critic Daniel Vaughn, the first written mention of smoked brisket occurred in 1910—it was served not at a barbecue joint but at the deli counter of two Jewish-owned grocery stores: Naud Burnett in Greenville, Texas, and the Watson Grocery in El Paso. Watson’s clients, for example, could choose among “cooked brisket,” “smoked brisket,” and “corned beef.”

How Brisket Makes People Happy Around the World

It wasn’t until the late 1950s that Black’s BBQ in Lockhart became the first Texas barbecue joint to offer brisket as a barbecue specialty in its own right. Prior to that, pit masters would smoke the entire beef forequarter. If you wanted “lean” beef, they’d serve you shoulder clod; if you wanted “fat,” you’d get brisket.

Vaughn credits brisket’s ascension to barbecue Valhalla with two different technological revolutions in the meatpacking industry. The first was the publication of the Institutional Meat Purchase Specifications (IMPS) in 1958. For the first time, butchers and meat purveyors had a precise universal definition of the various beef cuts, including brisket. (In case you’re curious: the IMPS number for a packer brisket is 120; the flat is 120A, the point is 120B.) Prior to this time, butchering was done at community meat markets, with scant concern for uniformity. But large customers, like the military—and eventually grocery and restaurant chains—required a consistently recognizable product, and here the IMPS provided invaluable guidance.

The second advance was the advent of boxed beef in the 1960s. “In the old days, we bought our meat as hanging beef [half carcasses],” recalls octogenarian pit mistress Tootsie Tomanetz of Snow’s BBQ in Lexington, Texas (more on Tootsie here). “We’d butcher it in-house and grind the brisket into hamburger.” Boxed meat (cut into consumer cuts and packaged at the processing plant) brought uniform, neatly butchered briskets in vacuum-sealed plastic bags to meat markets and restaurants. Gradually (and surprisingly recently), brisket became the most revered barbecue in Texas. When Snow’s opened in 2003, for example, they typically sold a half-dozen briskets on the one day of the week they’re open to the public: Saturday. Today, they cook ninety briskets and can barely keep up with demand.

If there’s one person responsible for the modern brisket craze, it’s Aaron Franklin of Franklin Barbecue in Austin. (Read all about him here.) Franklin transformed brisket from a regional Texas specialty to a cult meat prepared in places where you wouldn’t necessarily expect it, including Brooklyn, Los Angeles, and even Paris. This once Texas-poor-man’s beef earned Franklin highbrow acclaim in the New York Times and the New Yorker magazine, culminating in an unprecedented James Beard Award for best regional restaurant in 2015.

A Brief History of Brisket

1400s

The first written appearance of brisket (bru-kette) in the English language.

1500s and 1600s

Brusket, briscat, and brysket enter the lexicon.

1700s

Mrs. Raffald publishes the first printed brisket recipe in The Experienced English Housekeeper.

1800s

American food writing of the period is strangely silent on the subject of brisket, although Texans, Kansas Citians, and other Americans surely ate this versatile, flavorful cut of meat.

1900s

The first wave of brisket mania in North America, as European immigrants introduce pastrami, corned beef, and Montreal smoked meat.

1910

The first written mention of smoked brisket in Texas—it is served at the deli counter of two Jewish-owned groceries.

1950–1960s

Texas barbecued brisket makes its debut at Black’s BBQ in Lockhart and begins its ascension to cult status.

2000s and beyond

Destination barbecue joints such as Snow’s, Fette Sau, and Franklin Barbecue elevate barbecued brisket to the culinary stratosphere.

BRISKET SPEAK: At a Barbecue Restaurant or Competition

Bark: The exterior of a barbecued brisket. When a brisket is properly cooked, the bark will be dark, salty, smoky, and crusty.

Burnt ends: Traditionally, the crisp, tough, fatty brisket trimmings pared off before the meat is sliced and served. Pit masters, like the late Arthur Bryant in Kansas City, would give them away for free to the customers waiting patiently in line for the restaurant to open. In modern parlance, “burnt ends” have come to denote cubes of smoked brisket (typically brisket point) that are slathered with sweet barbecue sauce and smoked again. These are burnt ends you pay for. (See the recipe here.)

Deckle: What butchers call the fatty tissue between the brisket flat and the rib cage. It’s normally removed at the packing house. Note: In Jewish deli parlance, deckle is another name for the point (see below).

Fat cap: The thick layer of waxy white fat atop a brisket. Some of this will be removed during trimming, but always leave at least ¼ inch. The seam fat is the thick layer of fat between the point and the flat.

Flat: The lean, flat, trapezoid-shaped muscle that comprises the “bottom” of a brisket (although in fact, it’s anatomically located higher up on the steer, next to the rib cage—see Brisket Anatomy. This is the cut used to make lean corned beef.

Packer brisket: A whole brisket with both point and flat intact. After trimming and cooking, 40 to 50 percent remains edible meat.

Point: The fatty muscle that sits atop the brisket flat. On a steer, the point is located on top of and forward of the flat. The brisket point tends to be more tender, luscious, and fatty than the flat.

Smoke ring: A subcutaneous band of reddish pink found at the periphery of a slice of barbecued brisket. It results from a chemical reaction between the nitrogen dioxide found in wood smoke and the myoglobin found in the meat. Historically, this was the telltale mark of a properly smoked brisket, but it can be replicated by rubbing the outside of a brisket with a curing salt, like Prague Powder #1 (sodium nitrite). See the box on the smoke ring here.

Brisket Speak: At a Delicatessen

Corned beef: Brisket that has been cured in a brine with sodium nitrite and pickling spices. It is boiled, then sometimes steamed, but not smoked—at least not usually. (Here you’ll find a Brisket Chronicles first: smoked corned beef brisket.)

Montreal smoked meat: Canadian pastrami. Unlike American pastrami, it’s cured with dry seasonings, not in a brine.

Pastrami: Brisket that has been cured in a garlicky brine with sodium nitrite, onions, and aromatics. Next, it’s crusted with coriander, black pepper, and other spices, then smoked. The final step is steaming.

“Cold”: Chilled pastrami, corned beef, or brisket. Chilling allows you to slice the meat paper-thin, which is the way I like it. (So did the character Leo McGarry on the political drama West Wing.)

“Lean”: Lean pastrami or corned beef sliced from the flat section of the brisket.

“Fat”: Super-well-marbled pastrami or corned beef sliced from the point section of the brisket. Some people think of this as Jewish foie gras.

“Hot”: Pastrami, corned beef, or brisket served hot from the steamer. Must be sliced thick or it will fall apart.

Brisket Around the World

Back to our steer, Sam. His brisket will probably wind up as barbecue in Texas or Kansas City, or at a delicatessen in the form of pastrami, corned beef, or smoked meat.

• If you’re Jewish, you likely grew up with brisket braised with aromatic root vegetables and/or dried fruits as the centerpiece for Rosh Hashanah and other holiday dinners. Or perhaps you ate it chilled and sliced paper-thin on rye bread slathered with mustard (or if you were a Raichlen, mayonnaise—heresy for everyone else), a deli platter classic.

• In Ireland, brisket is “pickled”—cured in a brine flavored with salt, cloves, allspice berries, mustard seeds, and bay leaves, then boiled to make an electric pink meat enjoyed the world over. Traditionally, the salt came in grains the size of barley corns, so the meat became known as corned beef.

• The French braise brisket (poitrine de boeuf) with onions, carrots, bacon, and red wine to make a bistro classic: boeuf à la mode.

• In Germany and Austria, brisket braised with caramelized onions and beer becomes a comfort dish called Bierfleische (“beer-meat”). The Belgians and the French have a similar dish called carbonnade.

• Italians also braise brisket (both beef and veal) with red or white wine to make a soulful stew called stracotto. In Venice and Rome, they chop it and pile it on crusty rolls to be eaten as panini. In the Piedmont region in northern Italy, bollito misto reigns supreme. Picture brisket (again, both beef and veal) simmered for hours with chicken, beef tongue, and sausage and served sliced with tangy salsa verde (caper herb sauce). Traditionally dished up from a special silver trolley with great ceremony, it’s the world’s most elegant boiled dinner.

• Brisket is also beloved in the Spanish Caribbean and Central America, where it’s boiled, shredded, then simmered with cumin-scented Creole sauce to make the colorfully named dish ropa vieja, “old clothes.” Cubans deep-fry shredded boiled brisket with onions and garlic to make the equally poetic vaca frita, “fried cow.”

• Farther afield, brisket turns up in Kashmir, where it’s stewed in a thick paste of ginger, coriander, cardamom, and other spices to make a dish equally beloved by Pakistanis and Indians, nihari gosht.

• Koreans simmer it with glass noodles to make a rib-sticking soup called sulungtang. They also defy brisket physics by slicing it paper-thin and direct-grilling it like minute steaks (see here).

• Singaporeans simmer it in stews; the Chinese “red cook” it with soy sauce and fragrant star anise (see here).

• And more than 8,000 miles away from Sam’s pasture, brisket becomes another national dish and cultural treasure, pho chin nac (colloquially referred to as pho in the West)—the beef noodle soup eaten just about any time of day or night in Vietnam.

In other words, brisket has achieved culinary cult status around the world, and the multiplicity of dishes—soups, stews, sandwiches, and smoky slabs of meat—attests to its universal appeal.

Brisket Today and Tomorrow

Like any cult meat, brisket and how it’s cooked continue to evolve. Consider that epicenter of Texas barbecue, Austin: On a recent trip there, I enjoyed brisket ramen and brisket “hot pockets” at the Asian-Texas fusion restaurant Kemuri Tatsu-ya. Aaron Franklin and Tyson Cole (who is the owner of Austin’s renowned Uchi restaurant) serve kettle corn with brisket bits at their sizzling Asian smokehouse, Loro. In Austin, you could start your day with brisket breakfast tacos at Valentina’s and snack on brisket tots at EastSide Tavern. What’s next—a brisket dessert? It’s already here in the form of the brisket chocolate chip cookies served by Evan LeRoy at his LeRoy and Lewis food truck.

Why Brisket, Why Now?

So what is it about brisket that inspires such reverence and mystique, that makes it such a culinary icon and—dare I say—fetish?

Well, first there’s the flavor and texture. Like all well-exercised muscles, brisket possesses an extraordinarily rich, soulful, beefy flavor. When properly prepared, it becomes tender, but even when smoked or braised for the better part of a day, it retains a satisfying chew.

Then there’s its versatility. You can braise it, boil it, bake it, and, yes, even grill it. Served by itself, it dominates the meal, but it also makes a welcome addition to sandwiches, soups, stews, and stir-fries.

Price is a factor, too, and while brisket costs a lot more than it used to, it’s still a relative bargain compared with, say, prime rib or beef tenderloin.

And there’s no discounting good looks, for few food sights have the majesty of a whole, crusty, dark brisket hot out of the smoker. Or a steaming, kaleidoscopically colorful bowl of Vietnamese pho.

Finally, there’s the sheer challenge of barbecuing a brisket and the unabashed sense of triumph you feel when you nail it. Aaron Franklin puts it this way: “Ribs cook in a few hours. Pork shoulder is virtually impossible to screw up. But brisket requires fifteen hours of constant attention and supervision, and, believe me, there are no shortcuts. People know what you had to go through to get it right.”

This book is about brisket in all its multifarious glory. Brisket cooked outdoors in the best American barbecue tradition. Brisket cooked indoors in Dutch ovens and stockpots. Brisket cured to make corned beef, pastrami, and smoked meat. Brisket used to enhance everything from baked beans and baked potatoes to scones. Brisket may seem simple (many recipes require only the meat, plus salt, and pepper), but it isn’t always easy. In the following section, you’ll find everything you need to know about preparing brisket, from buying and seasoning it to cooking and serving it.

HOW TO BUY BRISKET—GRADES AND CUTS

Choice versus Prime? Grass-fed or Wagyu? Point versus flat? Brisket comes in a wide range of grades and cuts. The first step in brisket mastery is understanding them and buying the right cut for you.

Cattle Breeds

There are more than 250 recognized breeds of cattle in the world. Popular breeds here in the US include Angus, Hereford, Texas Longhorn, and Brahman. Farther afield, you find Jersey and Aberdeen Angus in the UK, Charolais in France, Chianina in Italy, Charbray and Brangus in Australia, and Japanese Black and Red (Akaushi) in Japan. Most North American brisket masters use Certified Angus Beef, colloquially known as CAB.

Making the Grade

Once processed, the beef is graded according to the amount of intramuscular fat (marbling) in the rib eye between the twelfth and thirteenth ribs. The quality of the final brisket varies with the cattle breed, how it’s raised, what it eats, and how it’s graded. In descending order of richness you find the following:

Prime has the most marbling (and correspondingly, the highest price), with fat ranging from “abundant” to “moderately abundant” to “slightly abundant.” (Quotes indicate USDA language.) Only 3.8 percent of the beef sold in the US merits the grade Prime. Look for Prime brisket at high-end butcher shops and meat markets. A small but growing number of barbecue restaurants, like Franklin Barbecue in Austin, serve only Prime brisket.

Choice beef has a “modest” to “small amount of marbling.” This is the grade sold at most supermarkets and served at many barbecue restaurants. It may lack some of the fat of Prime, but it still has plenty of flavor.

Select beef has a “slight” amount of marbling, but costs less than Prime or Choice. Most of it goes to food service, but you sometimes find it at the supermarket. Before you dismiss it outright, know that Select is the grade served at Snow’s BBQ in Lexington, Texas.

Choice Plus/Top Choice/Upper Choice, etc.: Many packing houses reserve their best Choice briskets for restaurants and institutional customers. They sell them under proprietary brand names, like Ranger’s Reserve, Boulder Valley, Seminole Pride, and so on. You may see these referenced on restaurant menus—or occasionally sold at meat markets. Expect a brisket with a little more marbling than Choice but less than Prime.

Wagyu: Native to Japan and now raised worldwide (including in the US), Wagyu beef is prized for its exceptionally generous marbling. A great Wagyu brisket will all but ooze with fatty goodness when you bite into it, with a buttery richness that lingers on your tongue long after you’ve swallowed it. But much Wagyu brisket sold in the US isn’t much richer than conventional Prime beef.

American Wagyu beef is rated by its BMS (beef marble score), with 3 being the lowest and 12 being the highest. Sometimes you’ll hear Wagyu referred to as A5, which designates a BMS of 8 or higher. This is extraordinary beef—some of the best on the planet. Picture white lace over a red tablecloth and you get a good idea of what A5 Wagyu looks like. Lower-ranked Wagyu is more on par with USDA Prime beef (which rates 4 to 5 BMS). This fatty goodness does not come cheap: Wagyu brisket typically costs two to four times as much as Choice brisket. Two good sources are Mister Brisket (misterbrisket.com) in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, and Idaho-based Snake River Farms (snakeriverfarms.com).

Wagyu brisket. Now that’s what you call marbling!

Kobe: Refers to Kuroge Washu and Tajima breed steers raised according to strict guidelines in Japan’s Hyogo Prefecture. Only a handful of restaurants are allowed to import and serve it in the US. Be very wary of brisket labeled “Kobe” in this country. I can almost guarantee you it’s not the real McCoy.

Grass-fed: Bos taurus (the domesticated cow) evolved as a grass eater. Grass-fed brisket has a distinctive flavor that ranges from herbaceous to minerally. Here in America, most grass-fed beef tends to be pasture-raised on small family farms. So if you’re concerned about eating humanely raised beef that’s free of antibiotics and growth hormones, grass-fed brisket is your ticket. (Food activist Michael Pollan would approve.) On the downside, grass-fed brisket tends to be leaner and tougher than grain-fed, making it more challenging to cook. One good source for superlative grass-fed brisket is Strauss Meats (straussdirect.com). Note: If you happen to live near or visit Charlotte, North Carolina, Vance Lin and Lindsay Williamson of the Farmhouse BBQ catering company (goodforyou.com) serve excellent grass-fed barbecued brisket at local fairs and farmers’ markets.

Grass-fed brisket: lean meat, great flavor

Craft beef: A new term coined by the online beef marketing company Crowd Cow to refer to “beef produced by small-scale, independent farms with an emphasis on unique flavors and high ethical standards.” In other words, it’s the opposite of the feedlot commodity beef found in most American supermarkets. I can tell you firsthand, it’s great meat. For more information and ordering, visit crowdcow.com.

Grain-fed: Corn-fed cattle grow faster and bigger than grass-fed, and their meat has a rich, appealing mouthfeel. Virtually all industrially raised beef is corn-fed—a diet that often requires treating the steers with antibiotics to keep them healthy in the feedlot. From a strictly taste-centered point of view, most Americans prefer grain-fed beef. One compromise is to buy grass-fed, grain-finished beef—ideally from a local or family farm that raises its cattle humanely. Remember: How your meat is raised matters as much as how you cook it.

Wet-aged beef/dry-aged beef: Freshness matters for seafood, but if you were to try to cook meat from a freshly slaughtered steer, you’d be surprised by how tough and dry it tastes. Aging improves the texture and flavor of all beef, and that aging can last anywhere from a few days in a vacuum-sealed plastic bag (wet aging) for typical supermarket beef to four to six weeks or even more unwrapped in a meat locker (dry aging). Aging produces the most dramatic results in the tender muscles that give us steak. According to Dr. Jeffrey Savell, Distinguished Professor of Meat Science at Texas A&M University, aging does not significantly improve a tough muscle like brisket. I can’t recall experiencing a single dry-aged brisket on my travels around Planet Barbecue.

Veal brisket: Nearly all of the brisket cooked in North America comes from steers, but in Italy, people love veal brisket. Here you’ll find a recipe for Venetian braised veal brisket. The bollito misto contains both veal and beef brisket. You’ll probably need to special-order veal brisket from a butcher. One good mail order source is straussdirect.com.

Veal brisket: Note the lighter color of the meat.

A 4-pound section of brisket comprising both the flat and the point

The brisket flat

The brisket point

As we have seen (here), brisket is comprised of two muscles: the pectoralis profundus (the lean flat) and the pectoralis superficialis (the fatty point). Together they comprise a packer brisket. This is a full brisket—12 to 18 pounds—and it’s what the pros smoke at the great barbecue restaurants in Texas, Brooklyn, and beyond. Supermarkets rarely display full packer briskets in the meat case (unless you live in Texas), so you’ll likely need to order one ahead of time from the meat manager or your local butcher. Note: Sometimes meat markets sell partially trimmed packer briskets typically weighing more in the neighborhood of 10 pounds.

A whole packer brisket

More often, what you will find at the supermarket are brisket flats, often cut into 3- or 4-pound sections, or on rarer occasions, fatty brisket points. The markets where I shop typically sell 4- to 8-pound sections of packer briskets that include both flat and point. Use these sectioned packer briskets or whole points for barbecuing. Four to 6 pounds is ideal—unless you’re up to smoking a whole packer brisket, which is even better. (It’s difficult to barbecue a brisket section weighing less than 3 pounds—it dries out before you get it fully cooked.)

Use brisket flats or smaller sections for boiling, braising, and stewing—or barbecuing draped with bacon (as described here) or in the style of Kansas City.

Curiously, brisket changes shape slightly from season to season, depending on market conditions. When brisket flats are at a premium, a packer brisket may come with more point and less flat. Brisket points are in high demand in Korea, so often this part gets exported, with the lean flat remaining in the US. Brisket prices tend to spike just before St. Patrick’s Day, Rosh Hashanah, and other holidays at which brisket is traditionally served.

Bottom line: Buy Prime brisket when you can; Choice or Choice Plus when you’re on a budget; and Wagyu when you’re feeling really extravagant. Look for NHTC (non-hormone-treated cattle) and avoid beef treated with antibiotics or HGPs (slow-release hormone growth promotants). Ask questions—you’ll get better brisket and your butcher will respect you more.

You can imagine that there are many opinions on the proper way to trim a brisket. Some restaurants, like Snow’s BBQ, trim quite radically (a 14-pound packer gets trimmed down to 6 to 8 pounds). Other restaurants hardly trim at all. In Kansas City, they routinely separate the point from the flat and smoke them separately, serving the point as burnt ends and the flat thinly sliced for sandwiches.

Aaron Franklin of Franklin Barbecue in Austin has turned trimming into high art. He starts by squaring off the long sides, then trimming the fat on the top and bottom. He cuts off the thin edges, which would burn in the smoker. (Some restaurants turn these flap pieces into chicken fried steak.) His briskets have rounded edges—the beef equivalent of an Airstream trailer. “Smoke and air don’t move in a linear fashion,” explains Franklin. “An aerodynamic brisket just cooks better.”

My own trim style loosely follows the Aaron Franklin method, but with a little more fat removed from the seam between the point and the flat. See step-by-step photos for details.

But however you trim, always leave at least a ¼-inch-thick layer of fat on the meat to keep it from drying out. When in doubt, err on the side of more fat.

1. Trim one slender edge off the flat section of the brisket.

2. Trim the slender edge off the other side of the brisket flat.

3. Trim the excess fat off the top of the brisket, but leave at least ¼ inch of the fat.

4. Cut out some of the seam fat between the point and the flat.

5. Cut out most of the hard lump of fat at the top and end of the point, again leaving a ¼-inch layer of fat.

6. Trim off the hard pocket of fat on the underside of the brisket under the point.

7. You can see how lean the underside is, and you can see the tight grain of the brisket flat.

8. Hang on to the fat trimmings—you can use them to grease the grill grate or to make Brisket Butter.

Brisket Hack: Brisket is easier to trim when it’s cold. Place it in the freezer for 30 minutes before trimming.

Brisket is a tough, flavorful cut loaded with a chewy connective tissue called collagen. Over the centuries and around the world, brisket lovers have relied on moist, low-heat cooking methods to make it tender. If you live in Texas or Kansas City (or elsewhere in America’s barbecue belt), for example, you likely cook your brisket outdoors in a smoker or barbecue pit. If you live in Latin America, Europe, or Asia, you probably use a Dutch oven, stockpot, or wok. Here are the traditional ways to cook brisket, plus one that proves the exception to the rule.

Barbecuing/smoking: For many Americans (and Raichlen readers and viewers, of course), this is the only way to cook brisket. You fire up your smoker (offset, water, drum, pellet, electric, what have you—see here). You burn wood or charcoal (or a combination of both), working at a temperature between 225° and 275°F for a cooking time that typically runs 12 to 14 hours for a whole packer brisket (somewhat less for flats). You wrap the brisket in butcher paper two-thirds of the way through the cook. Once it’s cooked, you rest the brisket in an insulated cooler for 1 to 2 hours before carving. The result? Crusty bark and luscious meat, with smoke, salt, and spice in perfect equipoise.

Texas-style brisket—barbecued

Braising: If you grew up in a Jewish family like I did, this was probably the first way you experienced brisket: braised in a covered pot with aromatic vegetables or dried fruit (or both) in a generous amount of liquid (ranging from water to wine to Coca-Cola). Braising takes its name from the French word for embers (braises). In the old days, you’d braise in a Dutch oven in your fireplace, the pot nestled in the embers, with more embers on the lid. Today, most of us braise in the oven, but the fiber-penetrating steam and low, moist heat still render the toughest brisket fork-tender. Added advantage: You make a sauce right in the pot.

Holiday brisket—braised

Stewing: Cut the brisket into smaller pieces and simmer it in considerably more liquid and you have another popular method for cooking brisket: stewing. Spanish Caribbean and Central American cooks stew shredded brisket in a cumin-scented tomato sauce to make the colorfully named ropa vieja. Stewing is generally done in a deep pot on the stove.

Ropa vieja—stewed

Boiling: This is the simplest method of all for cooking brisket: You place it in a pot of water (usually flavored with aromatic vegetables, fragrant herbs, and pungent spices) and boil it into submission. It sounds simple-minded—even boring—until you pause to remember that boiling produces three of the world’s most revered brisket dishes: Italian bollito misto (mixed boiled meats), Vietnamese pho (beef and rice noodle soup), and Korean sulungtang (brisket glass noodle soup). Nor should we forget New Zealand’s “boil up” (brisket or pork boiled with aromatic vegetables). Boiling is often done in two stages, starting with an initial boil called blanching, which removes the surface impurities. (Blanching typically takes 3 minutes of boiling, after which you rinse the meat, discard the boiling liquid, and wipe the pot clean.) A second boil (or more accurately, simmer) in fresh water does the cooking. Boiling actually serves two purposes. It cooks and tenderizes the meat, of course. But it also transfers the rich beefy flavor of the brisket to the broth. Note: In Cuba, boiling is combined with deep-frying to make a crispy shredded brisket dish called vaca frita (“fried cow”).

Pho—boiled

Grilling: Normally, direct grilling a tough cut like brisket would be a recipe for disaster. Well, here’s a shocker: At Korean grill parlors, they routinely direct grill brisket on tabletop braziers. The secret is to freeze the brisket, then slice it paper-thin on a meat slicer (or in a food processor). Grilled brisket has a completely different texture and flavor than smoked brisket. I love its crisp, fatty, beefy richness. (Try the recipe here.)

Korean brisket—grilled

Here in North America, the most popular way to cook brisket, of course, is barbecuing. You do it outdoors in a barbecue pit, smoker, or grill (set up for indirect grilling—or direct grilling in the case of the Brisket “Steaks” and Korean Grilled Brisket in chapter 2). But while barbecued brisket is king in the US, much of the world’s brisket is cooked indoors on the stove or in the oven. Indoor brisket includes Irish corned beef, Spanish Caribbean ropa vieja, Jewish braised brisket, Italian bollito misto, and Vietnamese pho.

Here’s what you need to cook brisket indoors and out.

Indoor Cookers

Dutch oven: Thick-walled and heavy-lidded, and twice as wide as it is tall, this is the quintessential pot for braising a brisket. A tight-fitting lid is essential for holding in the steam, which in turn is essential to cooking and tenderizing the meat. Three good brands are Staub, Lodge, and Le Creuset.

Stockpot: A waist-high stockpot dominates the kitchen at Pho Hoa Pasteur in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, where brisket, oxtails, and aromatic vegetables simmer for the better part of a day to make pho. You won’t need a stockpot quite that big, but choose one that holds at least 3 to 4 gallons, with thick walls to distribute the heat. It’s also useful for making Italian bollito misto and boiling the brisket for ropa vieja.

Pressure cooker, programmable electric cooker, slow cooker: These devices use pressure and/or electricity to cook your brisket. A pressure cooker shaves hours off the process of boiling or braising a brisket. (Choose one large enough to hold the size brisket you plan to cook.) A programmable electric cooker lets you sauté, simmer, boil, steam, and pressure-cook in a single device. It works well for any of the braises or soups in this book. Instant Pot is the industry standard. A slow cooker uses low moist heat and an extended cooking time—the time-honored method for cooking brisket. Crock-Pot is the industry standard. Follow the manufacturer’s instructions on how to use these appliances.

Outdoor Cookers

And now to the subject that generates, er, heated debate: the best smoker, grill, or barbecue pit in which to barbecue your brisket. Smokers vary widely in terms of function, capacity, and price. Each has its advantages and disadvantages. Here’s an overview. For a more in-depth discussion of how to use the various smokers, see my book Project Smoke and, of course, the manufacturer’s instructions.

Water smoker: This is a great all-purpose smoker—affordably priced and easy to use. Thanks to its simple design, it turns out excellent barbecued brisket every time. The fuel (charcoal, with wood chunks or chips added to generate wood smoke) goes in the bottom. A wide bowl of water sits in the center, shielding the brisket from direct heat. The brisket goes on a circular grate toward the top. You control the heat by opening or closing the vents at the top and bottom. Good brands include the Weber Smokey Mountain and Napoleon.

Advantages: Inexpensive (usually under $300) and easy to operate. The water in the pan creates a humid environment, which keeps the brisket moist and helps it absorb the wood smoke. Easy to maintain a consistent smoking temperature. Good for neophyte smokers, and its small footprint makes it ideal for people with limited space.

Drawbacks: Like all charcoal smokers, it requires some attention every hour.

Brisket Hack: Use the top-down burn technique to run your smoker for 4 to 6 hours or even longer without refueling. Pile unlit charcoal in the firebox (the bottom section with the perforated metal ring). Intersperse the charcoal with wood chunks or chips. Just before smoking, pour a third- to a half-chimney of hot embers on and in the center of the unlit coals. The fire will burn down gradually, giving you a long, slow, steady burn.

Kevin Kolman (of Weber) recommends placing two logs at the bottom of your smoker, with a chimney of unlit coals on top, then a chimney of lit coals on top of that. Run the smoker for at least 30 minutes to equalize the temperature before you add the brisket.

KEY TEMPERATURES FOR COOKING AND SERVING BRISKET

Brisket’s high collagen content and unique muscular structure (two separate muscles whose fibers run almost perpendicular to one another) require a series of precise storing, cooking, and serving temperatures to maximize tenderness. Here are the key temperatures.

Storing uncooked brisket

Below 40°F: The temperature at which brisket should be stored until you’re ready to cook it.

Smoker, oven, and stove temperatures

212°F: The temperature at which you boil brisket at sea level.

225° to 275°F (with 250°F being your target temperature): The proper temperature for your smoker or cooker.

300°F: The proper temperature for braising a brisket in the oven.

Internal Temperature

150° to 170°F: The temperature at which the stall (see here) takes place when barbecuing brisket. This typically occurs 6 to 8 hours into the cooking.

140° to 160°F: Brisket fat starts to render and its collagen starts to convert to gelatin.

165°F: The temperature at which you should wrap a barbecued brisket. Typically, you do this between 8 and 10 hours into the cook. (See The Wrap.)

175°F: The temperature to which you cook pastrami or smoked meat before steaming it.

185°F: If you live in Kansas City and you like your meat thinly sliced, cook your barbecued brisket to this temperature. This is also the temperature to aim for when boiling brisket to slice for pho.

203° to 208°F (with 205°F being your target temperature): If you live in Texas, Brooklyn, and elsewhere on Planet Barbecue, smoke a packer brisket to this temperature. Typically, the brisket reaches this temperature in 10 to 15 hours.

Resting and serving brisket

140° to 160°F: Once your brisket has rested, this is the temperature at which to slice and serve it.

Drum smoker: Picture an upright metal drum with vents at the top and bottom. The brisket rests on a wire rack toward the top. You fill the coal basket with unlit charcoal, then pour lit coals on top for a classic top-down burn. Intersperse the coals with wood chunks or chips to generate wood smoke. The gold standard is the Pit Barrel Cooker.

Advantages: Another affordable smoker ($300) that’s easy to use and space efficient. Its compact size and light weight make it quite portable (tailgaters take note).

Drawbacks: Relatively limited capacity (two flats or points or one full packer brisket).

Brisket Hack: On a Pit Barrel Cooker and other models, the vents come preset. At high altitudes, you’ll want to open the bottom vent a little wider to let in more air to boost the heat.

Kamado-style cooker: Epitomized by the Big Green Egg, these ovoid cookers have thick ceramic walls to hold in and maintain the heat, with a highly efficient vent system to help you regulate the temperature. (Newer models, like the Weber Summit charcoal grill and Char-Griller Akorn, use double-walled stainless steel.) When indirect grilling and smoking, a ceramic or metal plate (aka heat diffuser) goes between the fire and the grate to shield the brisket from the fire. As in the previous smokers, use a top-down burn to obtain a slow steady heat, interspersing wood chips or chunks throughout the charcoal to generate smoke. This huge and growing category includes the Big Green Egg, Komodo Kamado, Primo, Char-Griller Akorn, Monolith, Kamado Joe, Char-Broil, and others.

Advantages: The thick walls ensure a consistent temperature—even in winter. The tight felt or silicone gasket holds in moisture. Thanks to the efficient venting, a single load of charcoal burns many hours.

Disadvantages: Kamado cookers can be quite expensive. Depending on the model, your cook space is limited to one or two briskets. You don’t need to refuel often, but when you do, you have to remove the brisket, grates, and hot heat diffuser to add more charcoal.

Brisket Hack: Use an airflow controller, like a CyberQ to achieve a steady cooking temperature for long or overnight smoke sessions. When opening the lid of a kamado, “burp” it—that is, open the lid just a little a few times to let air in gradually. Opening the lid too wide too fast can result in a fiery flashback.

Offset smoker: This brings us into professional territory, for these massive steel cookers are what the pros use at barbecue competitions and restaurants. Picture a large horizontal metal cylinder with a hinged lid (the cook chamber), with a smaller cylinder with a hinged lid (the firebox) mounted slightly lower at one end, and a chimney pipe at the other. (Some models feature metal boxes instead of cylinders. On other models—called reverse flow smokers—the chimney is next to the firebox.) “Stick burners,” as these smokers are often called, burn logs or a combination of logs and charcoal. Respected brands include Horizon, Yoder, Pitts and Spitts, David Klose, Oklahoma Joe’s, and so on.

Advantages: If you love the process of splitting wood, building and maintaining a fire, and cooking like a barbecue pro, the stick burner is for you. It burns logs—the traditional way to barbecue brisket. Even small models can hold two or three packer briskets—professional scale models might hold thirty to fifty.

Disadvantages: Stick burners—especially those with thick metal walls (and you want thick metal walls, especially if you live in a cold climate)—can be quite expensive. They take up more real estate than water smokers or kettle grills and aren’t very portable—unless you attach one to a trailer. They also require hourly attention.

Brisket Hack: For wood, Russ Falk of Kalamazoo Outdoor Gourmet uses what he calls “brisket blocks”—4-by-6-inch slabs cut from 3-inch-thick oak boards. Thanks to its broad surface area and mass, a block is less likely to burst into flames than wood chips or chunks, delivering a longer, steadier stream of smoke.

Gravity smoker: A relative newcomer to the world of barbecue, but its simplicity and efficiency make up for lost time. In most smokers the wood goes on top of a bed of burning charcoal. In a gravity smoker, the hot coals drop from an overhead chute onto the wood, from whence the resulting smoke passes into the smoke chamber. State-of-the-art brands include Kalamazoo Outdoor Gourmet, T&K Smokers, and Deep South Smokers.

Advantages: Extremely fuel efficient and easy to refuel. They deliver smoke slowly and steadily for long cooks.

Disadvantages: They can be expensive.

Brisket Hack: The cook chamber is hotter at the firebox end (as much as 75 degrees hotter) than at the chimney (far) end. So position your brisket so the thick (point) end faces the firebox. Rotate the brisket several times during the cook.

Kettle grill: Yes, you can use a kettle grill or other charcoal grill as a smoker (provided it has a high lid for clearance). Set it up for indirect grilling, adding wood chunks or soaked wood chips to the coals to produce wood smoke. The same holds true for a frontloading charcoal grill, like the Char-Broil 940X.

Advantages: Affordable and easy to use. You may well own one already. The small footprint makes it ideal for people with limited space.

Disadvantages: Capacity is limited to a single brisket. Requires frequent refueling.

Brisket Hack: Use only half as much charcoal as you normally would to keep the temperature low.

Pellet grill: If you like the convenience of push-button ignition and turn-of-the-knob heat control, a pellet grill may be for you. The fuel (hardwood sawdust pellets) goes into a hopper, whence it’s fed by an auger into the burn chamber. This is another high-growth cooker category; good brands include Green Mountain Grills, Yoder, Memphis Wood Fire Grills, REC TEC, Traeger, and MAK.

Advantages: Pellet grills are exceedingly easy to operate, with a steady temperature control and smoke output. They truly are set-it-and-forget-it smokers.

Disadvantages: Like any machine with moving parts and electronics, they can break, requiring professional repair.

Brisket Hack: The lower the temperature, the greater the smoke output, which works out nicely for brisket.

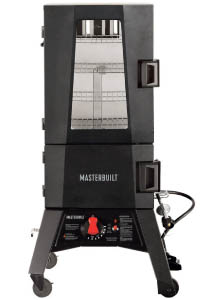

Electric smoker/gas smoker: Like pellet grills, electric smokers fall into the set-it-and-forget-it category, with digital thermostats to control the temperature and wood dispensers to deliver the smoke. One well-known brand, Masterbuilt, burns hardwood chips. Another, Bradley, burns compressed sawdust disks, called bisquettes. Gas smokers run on propane instead of electricity, using wood chips to generate smoke. Other popular brands include Smoke Hollow, Char-Broil, Dyna-Glo, and Smoke Vault.

Advantages: In two words, convenience and consistency. Electric smokers take the guesswork out of barbecue.

Disadvantages: Like any machine with moving parts and electronics, electric smokers can break, requiring professional repair.

Brisket Hack: Some models are too narrow to accommodate a full packer brisket. Cut the meat in half widthwise and smoke it on two separate racks.

SETTING UP YOUR GRILL FOR INDIRECT GRILLING AND SMOKING

To set up a kettle grill or other charcoal grill for indirect grilling, light the coals in a chimney starter, then rake the embers into two piles at opposite sides of the bottom (coal) grate. Or if your grill has side baskets, place the coals in them. Place a foil drip pan in the center, between the mounds of coals. Add wood chunks or chips to generate smoke. (For prolonged smoke sessions, soak the chips in water for 30 minutes, then drain. This slows the rate of combustion.) Place the brisket or other food to be smoked over the drip pan between the mounds of coals.

To smoke low and slow on a charcoal grill, use only half as much charcoal as you normally would.

To indirect grill on a two-burner gas grill, light one side and cook the brisket on the other (unlit) side. On a three-, four-, five-, or six-burner gas grill, light the outside or front and rear burners and leave the center burner(s) off. To generate wood smoke, use a smoking box, smoking puck, or foil smoking pouch (wood chips wrapped in heavy duty foil, which you then perforate with a sharp point), or place hardwood chunks under the grate over the burners. Not that I recommend cooking brisket on a gas grill, but that’s how you would do it.

Gas grill: I list gas grills reluctantly. It’s challenging to run a gas grill at a consistently low temperature (250°F) for the extended time it takes to cook a whole brisket. And even if your gas grill has a built-in smoker box, it’s hard to keep enough smoke under the hood to put significant flavor to the meat. (Most of the smoke escapes through the gap between the firebox and the lid in the back.) It helps to have a gas grill with multiple burners—the more burners, the more likely you’ll be able to maintain a low temperature.

Advantages: Push-button ignition and turn-of-a-knob temperature control. Okay for grilling brisket burgers, brisket steaks, and Korean grilled brisket.

Disadvantages: It’s very difficult to obtain a meaningful smoke flavor with a gas grill.

Brisket Hack: Set up the grill for indirect grilling. Place the brisket fat side up, away from the lit burner(s). Use an under-the-grate smoking pouch or use a grate-top smoker, like a smoking puck. Just don’t expect miracles.

Hibachi: Use this small charcoal-burning brazier to direct grill paper-thin shavings of frozen brisket (see here).

Advantages: Inexpensive, portable, and small enough for tabletop grilling.

Disadvantages: Good only for direct grilling, so this is a one-trick pony. (But, oh, what a trick.)

Brisket Hack: Place the hibachi on an inverted sheet pan or other heatproof surface in the center of your table. Have each guest grill his or her own brisket.

The Gear

You don’t need a lot of fancy equipment to cook brisket, but the following tools definitely make the work easier and more efficient.

Airflow controller: A barbecued brisket can take up to 15 hours of smoking, and this ingenious device keeps your cooker burning at a consistent temperature for the duration of the cook. It does so by controlling the airflow, adding more air when the temperature drops, and cutting the airflow if the temperature rises too much. A motorized fan over the intake air vent at the bottom moderates the airflow, while a thermocouple clipped to the grate monitors the temperature inside the smoke chamber. The CyberQ by BBQ Guru is the industry standard, with controllers that fit Big Green Egg and other kamado-style cookers, the Weber Smokey Mountain and other water smokers, and so on. To control the heat and airflow in an offset barrel smoker, use the Perfect Draft BBQ Blower.

Aluminum foil pans: Sometimes called drip pans, these are indispensable for indirect grilling, smoking burnt ends, and generally holding and moving ingredients. You’ll want several dozen 9-by-13-inch pans. While you’re at it, get some smaller 6-by-8½-inch pans.

Barbecue mop: A miniature cotton mop (some versions come in silicone) for swabbing mop sauces and bastes on the brisket. Look for a removable head so you can clean the mop in the dishwasher.

Cutting boards: Use for trimming and slicing (not the same board unless you wash it thoroughly with soapy water between uses). For serving brisket, you need a large board with a deep well (a groove around the perimeter) for catching the juices.

Gloves: Most pit masters check brisket for doneness by feel, not solely by internal temperature. How it bends when you lift it. Or how the fat jiggles when you poke it. You need to protect your hands with insulated gloves (usually rubber or silicone). They’re also useful for transferring hot cooked briskets from the smoker to the insulated cooler for resting, then to the cutting board for carving. Note: Some old-timers prefer the dexterity of wearing wool gloves with plastic or latex gloves over them to seal out the grease. Latex or rubber gloves are useful for keeping your hands clean while handling raw meat and applying rubs.

Injector: Used on the competition circuit to inject beef broth and other flavorings into the lean brisket flat to make it extra moist and flavorful.

Insulated cooler: One of the secrets to moist, tender barbecued brisket is to rest it for 1 to 2 hours after it comes out of the smoker (see here). The best place to rest it is in an insulated cooler, which keeps the brisket hot.

Jumbo (2.5-gallon capacity) resealable plastic bags: These are handy for brining brisket when making corned beef and pastrami. Use heavy-duty bags and double them up. I like to place them in a bowl or baking dish in the unlikely event that the bag leaks.

Knives: Unlike steak, brisket requires extensive trimming before cooking and careful carving for serving. So a good set of knives is essential. At a minimum, you’ll need:

A chef’s knife for cutting the brisket into pieces.

A boning knife with a curved slender blade for trimming the fat.

A paring knife for fine trimming and cutting the vegetables to add to brisket soups and stews.

A slicing knife for serving the brisket. Many pit masters slice with a serrated knife. Others use hollow-ground slicing knives, like the Shun brisket knife.

Meat slicer: Yes, I know this sounds like a formidable piece of equipment for a home kitchen, but without a meat slicer, it’s hard to cut those even, paper-thin slices of corned beef and pastrami that are the glory of a deli sandwich. It is also used to slice the boiled brisket for Vietnamese pho and the frozen meat for Korean Grilled Brisket. And this is the tool Kansas City pit masters use to make those thin, tender slices of smoked brisket flat that go on a Kansas City barbecue sandwich. Meat slicers are available both motorized and hand-cranked. Two good brands are Chef’sChoice and Kitchener.

Pink paper/butcher paper: Wrapping is an indispensable step in the process of smoking a brisket (see here). The wrap preferred by most pit masters is unlined butcher paper, often called pink paper (the color of leading brands, such as Bryco Goods). It’s important to use unlined butcher paper, which seals in moisture but releases the steam. Note: The butcher paper you get at a supermarket, like Whole Foods or Fresh Market, comes lined with plastic—not what you want for wrapping brisket.

Plastic buckets: Useful for brining briskets (and soaking and rinsing them when the brisket is cured). YETI makes cool plastic buckets.

Sprayer: Useful for spraying cider, vinegar, or other flavorful liquids on the brisket.

Thermometers for checking doneness

Thermometers: Essential for monitoring the internal temperature of a brisket as it cooks. At the very least, you’ll want a stick thermometer with a slender probe you insert in the meat. For long slow cooks, you’ll want a remote digital thermometer that has a probe for the meat and an external monitor that displays the temperature outside the smoker. Higher-end models have multiple probes (one for the meat, for example, and one to measure the temperature of the cook chamber at grate level). Some remote thermometers send the information directly to your smartphone. The industry leaders are Maverick and ThermoWorks.

THE 11 STEPS TO BARBECUED BRISKET NIRVANA

I’ve said it before; I’ll say it again: Brisket is simultaneously the easiest and most difficult meat there is to barbecue. Easy, because all you do is season it with salt and pepper and smoke it low and slow until it’s tender enough to cut with the side of a fork. Difficult, because every brisket is different and there are dozens of variables—and if you don’t get them right, your rich, luscious, meltingly tender slab of meat may come out more like beefy shoe leather. But you can break the process into easy, manageable steps, which will help you achieve brisket nirvana every time.

Step 1: The Meat

Brisket comes in a wide range of grades from a variety of cattle breeds—each with its own flavor, texture, and cooking properties. Grass-fed brisket cooks and tastes different than grain-fed; Wagyu has a remarkably different fat structure and content than Angus. I’m not saying one is better than the other—just different. Here you’ll find a complete description of the various types of brisket and the best methods for cooking them.

A whole brisket (also known as a packer brisket) is comprised of two separate muscles: the fatty point and the lean flat. Most professionals cook them together as one. Your supermarket may sell them in sections or as separate cuts—especially the brisket flat. Here you’ll find instructions for smoking a whole packer brisket; here, a brisket point; and here, a brisket flat.

Regardless of cut, brisket comes with a thick cap of fat and a hard waxy stratum of fat between the point and flat, both of which you’ll need to trim. The purpose of trimming is to remove excess fat, which takes time, fuel, and energy to cook (only to be discarded before serving). But you have to leave enough fat to melt and baste the brisket as it cooks, keeping it rich-tasting and moist. Here, you’ll find step-by-step trimming instructions and photos.

Step 2: The Seasoning

Pit masters are divided on how simple or complex to make the seasonings. I like a “newspaper rub”: black (pepper), white (sea salt), and “read” (red—hot pepper flakes) all over. Wayne Mueller of Louie Mueller Barbecue in Taylor, Texas, seasons solely with salt and pepper (often called a “Dalmatian rub” on account of being white with black speckles). Conversely, Joe Carroll of Fette Sau in Brooklyn and Philadelphia uses a complex blend of coffee, brown sugar, cumin, and other spices (see here). John Lewis of Lewis Barbecue in Charleston slathers his brisket with mustard before applying the seasonings.

Other techniques—often practiced on the competition barbecue circuit—add additional layers of flavor. Some pit masters inject their briskets with a mixture of beef broth, melted butter, and spices. (You’ll find the recipe for a great injector saucea>.) Others swab their briskets with a mop sauce (see here) or spray the meat with vinegar, wine, or apple cider.

But remember: The purpose of the seasoning is to flavor the brisket without camouflaging its primal smoky beef taste.

1. To make a Dalmatian rub, combine equal parts coarse salt and pepper in a bowl.

2. Mix the seasonings with your fingers.

3. To make a newspaper rub, mix in hot red pepper flakes.

4. Season the top of the brisket, working several inches above the brisket so the spices go on evenly.

5. Don’t forget to season the sides and underside of the brisket, too.

Step 3: The Cooker

You can barbecue an excellent brisket in a stick burner (offset smoker), water smoker, barrel cooker, ceramic cooker, electric or gas smoker, pellet grill, and, of course, in a charcoal kettle grill. What’s important is to use a cooker that runs at a consistent temperature and provides a steady stream of wood smoke during the cook. Remember: The smoker both smokes and cooks your brisket. Every model operates differently and has its own advantages and disadvantages: See the guide to the various smokers and grills found here.

Step 4: The Fuel

To barbecue your brisket, you’ll need fuel, and that means wood, or a combination of wood and charcoal. (Electric and gas smokers use those heat sources respectively for igniting the wood or wood pellets.) Wood comes in several forms, starting with the most elemental—hardwood logs.

Hardwood logs: The fuel of choice for professional pit masters. Texans burn oak; Kansas Citians burn hickory and apple. Other popular woods for brisket include pecan, cherry, and mesquite. (I suspect that regional preferences have less to do with flavor profile than with what wood traditionally grew abundantly in a particular area.) The variety matters less than using logs that are split and seasoned (dried). Twelve to 16 inches in length is ideal. Avoid green wood: The smoke will be bitter and it takes a ton of BTUs just to evaporate the water.

Brisket Hack: If you have green or damp logs, place them on top of your smoker to dry them out before adding them to the fire.

Wood chunks: Most home cooks use a combination of charcoal and hardwood chunks or chips. The charcoal provides the heat; the wood generates the smoke. Look for wood chunks at hardware stores and supermarkets. See above for common varieties. Soaking is optional (see below). Add fresh wood chunks every hour (or as needed) to generate a continuous stream of smoke.

Wood chips: The most common form of smoking wood is the wood chips available in supermarkets and hardware stores everywhere. I like to soak chips in water to cover for 30 minutes, then drain them before adding them to the coals. Soaking slows the rate of combustion, giving you a longer, steadier smoke. Add soaked wood chips every 30 to 45 minutes (or as needed).

Pellets: Pellet grills use tiny cylinders of compressed hardwood sawdust to generate heat and smoke; the pellets come in a variety of flavors. Look for food-safe pellets made without fillers. Avoid pellets held together with cheap vegetable oil, plus bags with a lot of dust in the bottom, or pellets that have been stored outside. Moisture compromises their integrity.

Bisquettes and other sawdust disks: Made of compressed hardwood sawdust, these disks generate smoke in Bradley electric smokers.

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT WOOD

Smoke is the soul of barbecue—especially barbecued brisket—and it’s also one of the defining flavors of pastrami and Montreal smoked meat. So as you become a brisket master, you need to understand smoke—how to generate it, which woods produce the best smoke, and how to harness its flavor-producing properties to take your brisket over the top.

All burning wood, and many other burning plants, like straw and hay, produce smoke. Softwoods, such as spruce and pine, produce an unpleasantly resinous smoke. The best smoke comes from hardwoods (deciduous trees, which shed their leaves each year). Hardwoods come in two main categories: fruitwoods, such as apple, cherry, and peach, and nut woods, such as hickory, pecan, and oak.

A lot of ink has been spilled about the best wood for smoking, so I’m about to make a controversial statement: While apple, cherry, oak, and hickory smokes differ slightly in their flavor profile, by the time you’ve smoked a brisket for 12 hours, they’re pretty interchangeable. The one exception here is mesquite, whose smoke is noticeably stronger and more bitter. For the record, the wood burned by most American pit masters, from Wayne Mueller at Louie Mueller Barbecue in Taylor, Texas, to Billy Durney in Brooklyn, New York, is oak.

Use the hardwood that grows in your area—that’s what the original pit masters did, and what experienced pit masters still do today. As for mixing woods (cherry for the first 4 hours, apple thereafter), it makes for good storytelling on the competition circuit, but I’m not sure you can really taste the difference. Stick with one wood and focus on burning it right.

Far more important than the species of the wood is its overall condition and moisture content. Green wood (from freshly cut trees) contains up to four times as much moisture as seasoned (aged and dried) wood. It takes longer to light and is slower to burn, delivering less heat and more bitter creosote. Fully seasoned wood contains less than 20 percent moisture, which makes it easier to light and burn. There are two ways to season wood: in a kiln or by leaving it outdoors in a dry place for months or even years. Seasoned wood has a silvery-gray appearance. It burns efficiently and clean: That’s what you want for your brisket.

When you burn wood, it goes through three stages: desiccation (drying out), pyrolysis (decomposition by fire), and combustion. Smoke production takes place during the pyrolysis stage between 340° and 800°F. This is your barbecue sweet spot. Beyond that, the wood catches fire, producing heat but no smoke. This is useful for grilling, which you don’t normally do with a tough meat like brisket, unless you’re cooking the brisket burgers found here or the brisket “steaks”. When it comes to barbecued brisket, low and slow wins the race.

Charcoal: Supplies the heat in water smokers, kamado cookers, drum cookers, kettle grills, and other charcoal-fueled cookers. I prefer lump charcoal, which contains only wood. But charcoal briquettes (a composite of wood, coal dust, borax, and petroleum or starch binders) are the fuel used at the big barbecue competitions, like the Jack Daniel’s and the American Royal. Just make sure the briquettes are lit completely (glowing red with a light dusting of gray ash) before you put the brisket in the smoker.

Step 5: The Smoke

Wood smoke is an incredibly complex substance comprised of solids (such as soot), liquids (in the form of water and tars), and gases (of which there are hundreds, ranging from aldehydes to phenyls). Each contributes to the appearance, aroma, and ultimate flavor of your barbecued brisket.

The soot and tars, for example, help color your brisket, producing the appetizing dark, savory crust we call bark. Gases include acids, such as formic and acetic acids, which give the smoke a pleasant tartness. Carbonyls (produced around 390°F) have antimicrobial and preservative properties. (Remember, throughout most of human history, the main purpose of smoking foods was to keep them from spoiling.)

But it’s the phenyls (which start forming around 570°F) that give us the complex micro-flavors we associate with the best barbecued brisket. One such phenyl, syringol, produces the textbook smoke flavor. Creosol delivers a peat-like taste that may remind you of Scotch whisky. Guaiacol is responsible for clove-like spice flavors, while vanillin adds a musky sweetness we associate with dessert.

Just as important as what’s in smoke is how you produce and deliver it. Add too much smoke too fast and your brisket will taste bitter. Add too little smoke (a chronic problem with gas grills) and your brisket will taste like cooked beef—but not barbecue. Dose the smoke slowly and steadily for half a day and you’ll experience that quasi-religious state I like to call brisket nirvana.

Slow and steady means a clean-burning fire to which you add a couple of logs every hour. Or if you’re cooking on a charcoal smoker, add the wood chunks or chips gradually. Two handfuls of wood chips every hour is good. Too much wood at the start of the smoke will make your brisket taste like an ashtray.

The color of your smoke tells you whether you’re doing it right. Black smoke indicates a dirty fire full of the bitter creosote. White smoke indicates a fire that’s starved for oxygen. You’re looking for what pit masters call “blue smoke”—a pale wispy smoke with a faint bluish tinge. Or in the words of one Texas pit master, “You want the smoke to kiss the brisket, not overpower it.”

A steady stream of blue smoke is essential for great brisket.

Step 6: the First Cook

The first cook takes your brisket to an internal temperature of 165° to 170°F. It browns the exterior, forming a salty, smoky crust known as the bark. It perfumes the meat with wood smoke, renders out some of the fat, and starts to convert the tough collagen into tender gelatin. (See here.) The first cook of a packer brisket normally takes 8 to 10 hours. Protect the end of the flat with an aluminum foil cap and the bottom with a cardboard platform (see above) to keep them from drying out.

A foil cap protects the narrow end of the brisket.

At some point during the cooking process, the internal temperature rise will slow down, stop, or even drop. This is called the stall and although it causes anxiety, it’s a normal part of cooking a brisket. The stall typically takes place around 6 to 8 hours into the cooking process, when the internal temperature of the brisket is in the range of 150° to 170°F. You watch your remote thermometer with growing disbelief. You add more fuel to the fire in an attempt to reverse the stall. But the temperature stays steady or even drops.

What’s actually happening is simple: As the brisket cooks, moisture pools on its surface. As that moisture evaporates, it cools off the brisket, much as perspiration cools you off—even on a hot day.

The stall normally lasts for 2 to 3 hours. Once all the moisture has evaporated, the internal temperature will start to rise again.

So what should you do when your brisket stalls? Don’t panic. Don’t add more fuel to the fire. Be patient and power through it. Sure as night turns into day, the temperature will rise and finish cooking your brisket.

HOW TO MAKE A CARDBOARD SMOKING PLATFORM

Ever notice how the bottom of the brisket flat tends to dry out and sometimes burn during long smoke sessions?

Billy Durney of Hometown Bar-B-Que in Brooklyn has an ingenious hack for preventing this, and it also makes your cooked brisket easier to handle.

Place the raw brisket on a piece of cardboard (clean, obviously) and trace its outline on top. Cut the cardboard into this shape, then wrap it tightly with heavy-duty aluminum foil.

Using an ice-pick, Phillips-head screwdriver, or other sharp implement, poke holes in the foil-wrapped cardboard every inch or so. This allows the smoke to penetrate the smoking platform and flavor the meat.

1. Trace around the brisket, then cut the cardboard to shape.

2. Poke holes in the foil-wrapped cardboard.

3. The platform prevents the bottom of the brisket from drying out.

You’ve stoked your smoker and powered through the stall. The meat’s exterior has darkened to a handsome, espresso-hued crust, and the internal temperature has reached 165°F.

It’s time for one of the most essential, if paradoxical, steps in barbecuing a perfect brisket: the wrap.

Paradoxical, because in effect, you’re segregating the brisket from the one ingredient that defines it as barbecue: wood smoke.

Essential, because it seals in moistness and keeps your brisket from drying out.

And every serious pit master does it, although debate rages as to whether you should wrap in butcher paper, aluminum foil, plastic wrap, a bath towel, or some combination of the four.

Aaron Franklin of Austin’s Franklin Barbecue wraps in butcher paper. Tootsie Tomanetz of Snow’s BBQ in Lexington, Texas, wraps in foil. Quinn Hatfield of Mighty Quinn’s Barbeque (with locations around New York, New Jersey, and abroad) wraps in plastic. Wayne Mueller of Louie Mueller Barbecue in Taylor, Texas, takes a one-two approach, wrapping first in plastic, then in butcher paper, and rewrapping each piece after slicing off a serving.

Wrapping serves several purposes. It seals in moisture during the final stage of the cook. It makes it easier to handle the cooked brisket. And it swaddles the brisket during the all-important resting period, allowing the juices to redistribute and the meat to relax.

I used to wrap brisket in aluminum foil—a practice that led me into a Twitter war with the late Anthony Bourdain. It’s true that foil delivers a fork-tender brisket every time. It does so by converting the moisture to steam, which tenderizes the brisket (much the way you steam pastrami to finish cooking it). The problem is that with supernatural tenderness comes a pot roast–like consistency. So eventually, I switched to wrapping in butcher paper, and I’ve never looked back. The advantage of butcher paper is that it “breathes,” releasing the steam while keeping the moisture in the meat.

So here, step-by-step, is how to wrap your brisket. Dimensions are for a full packer brisket; use smaller sheets to wrap brisket flats or points.

1. Lay two sheets of butcher paper, each about 3 feet long, on your work surface so they overlap in the center to form a 3-foot square. Wearing heatproof gloves, transfer the brisket to the center of the paper square so the long side of the meat runs parallel to your shoulders.

2. Lift the back of the paper square (the side closest to you) and fold it over the brisket.

3. Tuck and fold in the sides of the paper as though you’re making a blintz or an eggroll.

4. Roll the brisket over to enclose it completely in the pink paper. Note the orientation: You want the point (the fatty part) of the brisket to remain on top.

5. Tuck any overlapping paper into the seam, which, ideally, will be at the bottom. Return the wrapped brisket to the cooker.

During the second cook, you’ll take the brisket to an internal temperature of around 205°F. The purpose of the second cook is to finish rendering the fat and converting the tough collagen into tender gelatin. This will require an additional 2 to 5 hours, bringing your total cooking time to 10 to 14 hours, depending on the size of your brisket.

Step 9: The DONENESS Test

You’ve spent $50 to $100 buying your brisket, plus up to 14 hours cooking it to smoky perfection. The last thing you want to do is over- or undercook it. So how do you know it’s done? Internal temperature is a useful indicator. So are visual tests, such as the jiggle, bend, and chopstick tests. Good pit masters use several tests at once. Here are the ones I use:

Check the internal temperature using an instant-read meat thermometer. You’re looking for around 205°F.

Internal temperature test: 185°F: The temperature to which Kansas City pit masters cook their brisket flats. At this stage the brisket is still firm enough to slice on an electric meat slicer.

203° to 208°F: The temperature to which Texas pit masters cook packer briskets. At this stage the collagen is fully gelatinized and the fat fully rendered. The brisket will be so tender that you need to hand-carve it with a knife. All the following tests apply to a well-done brisket cooked to this stage.

Jiggle test: Grab the brisket from the fat end and poke/shake it. The meat will seem to jiggle a bit like Jell-O.

Bend test: Grab the brisket at both ends and lift. It should bend easily in the middle. Alternatively, slide your hand under the brisket in the center. The ends will droop like a forlorn mustache.

Note the use of insulated food gloves during the jiggle test—the brisket will be hot!

The chopstick test: Insert the slender end of a chopstick through the brisket from top to bottom. It will pierce the brisket easily.

Chopstick test: Insert the slender end of a chopstick or the handle of a wooden spoon through the top. It should pierce the meat easily.

Bottom line: Your brisket is done when the meat is crusty and darkly browned on the outside, and smoky and tender (but not mushy) on the inside. Each bite should be meaty, fatty, and rich, and each slice should pull apart, not fall apart.

You can certainly eat the brisket following the second cook, and after 10 to 14 hours of cooking, I won’t blame you if you want to do so. But there’s one more step that will take your barbecued brisket from excellent to sublime: the rest. In a nutshell, you rest the wrapped brisket in an insulated cooler for 1 to 2 hours. This allows the meat to “relax” and the juices to redistribute. This makes your brisket juicier and more tender. It also allows you to control the precise moment when you serve it.

1. Place the wrapped brisket, flat side down, in an insulated cooler to rest it.

2. Let the wrapped brisket rest for 1 to 2 hours in the cooler.