A health care system is only as good as the people working in it. The most valuable resource in health care is not the latest technology or the most state-of-the-art facility, but the health care professionals and other workers who are the human resources of the health care system.

In this chapter, we discuss the nation’s three largest health professions—nurses, physicians, and pharmacists, as well as a closely linked profession, physician assistants (Table 7–1). What are the educational pathways and licensing processes that produce the nation’s practicing physicians, nurses (including nurse practitioners), pharmacists, and physician assistants? How many of these health care professionals are working in the United States, and where do they practice? Do we have the right number? Too many? Too few? How would we know if we had too many or too few? Are more women becoming physicians? Are more men becoming nurses? Is the growing racial and ethnic diversity of the nation’s population mirrored in the racial and ethnic composition of the health professions? To answer these questions, we begin by providing an overview of each of these professions, describing the overall supply and educational pathways. We then discuss several cross-cutting issues pertinent to all these professions.

Table 7–1. Number of active practitioners in selected health professions in the United States, by profession and year

Susan Gasser entered medical school in 1997. During college, she had worked in the laboratory of an anesthesiologist, which made her seriously consider a career in that specialty. During her first year of medical school, the buzz among the fourth-year students was that practice opportunities were drying up fast in anesthesiology. Health maintenance organizations (HMOs) wanted more primary care physicians, not more specialists. Almost none of the fourth-year students applied to anesthesiology residency programs that year. Susan started to think more about becoming a primary care physician. In her third year of school, she had a gratifying experience during her family practice rotation working in a community health center and started to plan to apply for family practice residencies.

At the beginning of her fourth year of school, Susan spent a month in the office of a suburban family physician, Dr. Woe. Dr. Woe frequently remarked to Susan about the pressures he felt to see more patients and about how his income had fallen because of low reimbursement and higher practice expenses. He mentioned that the local anesthesiology group was having difficulty finding a new anesthesiologist to join the group to help keep up with all the surgery being performed in the area. The group was guaranteeing a first-year salary that was twice what Dr. Woe earned as an experienced family physician. Susan quickly began to reconsider applying to anesthesiology residency programs.

Approximately 873,000 physicians are professionally active in the United States. One-third are in primary care fields, and two-thirds in non–primary care fields. Of physicians who have completed residency training, more than 90% have patient care as their principal activity, with the remainder primarily active in teaching, research, or administration (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2008a). Licensing of all types of health care professionals, including physicians, is a state jurisdiction. State medical boards require that physicians applying for licen-sure document a passing grade on national licensing examinations, certification of graduation from medical school, and (in most states) completion of at least one year of residency training after medical school.

The University of Pennsylvania opened the first medical school in the colonies in 1765, promoting a curriculum that emphasized the therapeutic powers of blood letting and intestinal purging. Many other medical sects coexisted in this era, including the botanics, “natural bonesetters,” midwives, and homeopaths, without any one group winning dominance. Few regulations impeded entry into a medical career; physicians were as likely to have completed informal apprenticeships as to have graduated from medical schools. Most medical schools operated as small, proprietary establishments profiting their physician owner rather than as university-centered academic institutions (Starr, 1982).

The modern era of the US medical profession dates to the 1890–1910 period. In 1893, the opening of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine ushered in a new tradition of medical education. Johns Hopkins University implemented many features that remain the standard of medical education in the United States: a 4-year course of study at the graduate school level, competitive selection of students, emphasis on the scientific paradigms of clinical and laboratory science, close linkage between a medical school and a medical center hospital, and cultivation of academically renowned faculty.

The second key event in the creation of a reformed twentieth-century medical profession was the publication of the Flexner Report in 1910. At the behest of the American Medical Association, the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement in Teaching commissioned Abraham Flexner to perform an evaluation of medical education in the United States. Flexner’s report indicted conventional medical education as conducted by most proprietary, nonuniversity medical schools. Flexner held up the example of Johns Hopkins as the standard by which the nation’s institutions of medical education should be judged. Flexner’s report was extremely influential. More than 30 medical schools closed in the decades following the Flexner Report, and academic standards at the surviving schools became much more stringent (Starr, 1982). More vigorous regulatory activities in respect to credentialing of medical schools and licensure for medical practice soon enforced the standards promoted in the Flexner Report, and only schools meeting the standards of the Licensing Council on Medical Education (LCME) were allowed to award MD degrees. Unlike the state boards licensing practice entry, which are government agencies, the LCME was a private agency operating under the authority of medical professional organizations. LCME-accredited schools became known as “allopathic” medical schools to distinguish themselves from homeopathic schools and practitioners. Although homeopaths still practice in the United States (there is now a resurgence of homeopathic practitioners), homeopaths are not officially sanctioned as “physicians” by licensing agencies in the United States. However, one alternative medical tradition has survived in the United States that carries the official imprimatur of the physician rank—osteopathy. Osteopathy originated as a medical practice developed by a Missouri physician, Andrew Still, in the 1890s, emphasizing mechanical manipulation of the body as a therapeutic maneuver (Starr, 1982). Schools of osteopathy award DO degrees and have their own accrediting organization. Much of the educational content of modern-day osteopathic medical schools has converged with that of allopathic schools. Most state licensing boards grant physicians with MD and DO degrees equivalent scopes of practice, such as prescriptive authority. By the middle of the twentieth century, regulatory restrictions on practice entry, institutionalization of a rigorous standard of academic training, and the rapid growth of medical science and technology solidified the prestige and authority of licensed physicians in the United States.

In 2010, allopathic schools had 16,838 graduates, and osteopathic schools 3631. The annual number of allopathic school graduates changed little between 1980 and 2008, and only started to increase in 2009 in response to a new surge of medical school expansion starting in the first decade of the twenty-first century. In contrast, the annual number of osteopathic graduates has grown steadily over past decades, increasing threefold between 1980 and 2010.

At least one year of formal education after medical school is required for licensure in most states, and most physicians complete additional training to become certified in a particular specialty. Traditionally, the first year of postdoctoral training was referred to as an “internship,” with subsequent years referred to as “residency.” Before the advent of specialization, many physicians completed only a single year of a general “rotating” internship. Physicians aspiring to full specialty training became residents (with trainees often literally “residing” in the hospital because of endless hours of on-call duty). Now, almost all physicians in the United States complete a full residency training experience.

Residency training is much more decentralized than medical school education. Although some residency training programs are integrated into the same large academic medical centers that are home to the nation’s allopathic medical schools, many smaller community hospitals sponsor residency-training programs, often in only one or two specialties. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), a private agency, accredits allopathic residency training programs. Residency training ranges from 3 years for generalist fields, such as family medicine and pediatrics, through 4 to 5 years for specialty training in fields such as surgery and obstetrics–gynecology, to 6 years or longer for physicians pursuing highly subspecialized training. Some osteopathic schools sponsor osteopathic residency programs.

Once physicians have completed residency training, another private consortium, the American Board of Medical Specialties, certifies physicians for board certification in their particular specialty field. Criteria for board certification usually consist of completion of training in an ACGME-accredited program and passing of an examination administered by the specific specialty board (eg, the American Board of Pediatrics). Board certification is not required for state licensure. Physicians may advertise to patients their status as specialty board-certified to promote their expertise and qualifications, and board certification may be a factor considered by hospitals when deciding whether to allow a physician to have “privileges” to care for patients in the hospital or for managed care organizations deciding whether to include a physician in the organization’s physician network. Many specialty boards now require periodic reexamination to maintain certification.

Each year, approximately 25% more physicians enter ACGME residency programs than the number of students graduating from US allopathic medical schools. Who fills these extra residency positions? Approximately 7% are filled by graduates of schools of osteopathy; half of DO graduates enter allopathic residencies rather than residency programs sponsored by schools of osteopathy. The remainder of the ACGME residency positions are filled by physicians who graduated from medical schools outside the United States. A complex regulatory structure exists to govern which international medical graduates are eligible to enter residency training in the United States, involving state licensing board sanctioning of the graduate’s foreign medical school and graduates completing US medical licensing examinations. There is almost no opportunity for international graduates to become licensed to practice in the United States without first undergoing residency training in the United States, even if the physician has been fully trained abroad and has years of practice experience. Some international medical graduates are US citizens who decided to train abroad, often because they were not admitted to a US medical school. However, the majority are not US residents, and most of these physicians come from India, the Philippines, sub-Saharan Africa, and other developing nations (Mullan, 2005). International medical graduates who are not US citizens receive only a temporary educational visa while in residency training, and in principle there is an expectation that these individuals will return to their nations of origin once they have completed training. However, various visa-waiver programs exist to allow these physicians to remain in the United States after completing training, usually linked to a period of service in a US community with a physician shortage. Controversy exists about this reliance on international medical graduates to meet US physician workforce needs, with critics arguing that the United States fosters a “brain drain,” depleting developing nations of vital human resources (Mullan, 2005).

Who pays the cost of medical education in the United States? Unlike the case in most developed nations, where medical schools levy no or only nominal tuition, students pay high amounts of tuition and fees to attend US medical schools. Approximately half of US medical schools are public state institutions, with state tax revenues helping to subsidize medical school education. The Federal Government plays a minor role in financing medical student education, but is a major source of funds to support residency training. Medicare allocates “graduate medical education” funding to hospitals that sponsor residency programs. These funds are considerable, amounting to $9.5 billion annually, and include “direct” education payments for resident stipends and faculty salaries plus indirect education payments to defray other costs associated with being a teaching hospital. The joint federal–state Medicaid programs contribute an additional $3 billion annually to residency education (Iglehart, 2010). Although in 1997, Medicare capped the number of residency program slots it would pay for, Medicare gives hospitals considerable latitude in how to spend their Medicare medical education dollars. Hospitals can decide which specialties, and how many slots in each specialty, they wish to sponsor for residency training, and can qualify for Medicare education payments as long as the positions are ACGME accredited. Hospitals may also invest non-Medicare revenues in their residency education programs and are not beholden to a prescriptive national workforce planning policy. Hospitals have tended to preferentially add new residency positions in non–primary care fields, guided more by the value of residents as low-cost labor to staff hospital-based specialty services than by an assessment of regional physician workforce needs and priorities. Between 2002 and 2007, hospitals added nearly 8000 new residency positions despite the cap on Medicare-funded positions, with virtually all the gains occurring in specialist positions and family medicine residency positions losing ground during the same period (Salsberg et al, 2008).

Jillian Boca was a speech therapist at a community hospital. She liked her work but wanted to advance in her career. She was talking to some of her colleagues who were physical therapists and x-ray technicians; they were thinking of going back to school to become physician assistants. One of the registered nurses at the hospital was also planning to go back to school to become a nurse practitioner. A local medical school sponsored a program with physician assistant and nurse practitioner students receiving their training together. Jillian and two of her colleagues were admitted to the program.

As the name suggests, physician assistants (PAs) are closely linked with physicians. The profession of PA originated in the United States in 1965 with the establishment of the first PA training program at Duke University School of Medicine. The PA profession developed to fill the niche of a broadly skilled clinician who could be trained without the many years of medical school and residency education required to produce a physician, and who would work in close collaboration with physicians to augment the effective medical workforce, especially in primary care fields and under-served communities. The first wave of PAs trained in the United States included many veterans who had acquired considerable clinical skills working as medical corpsmen in the Vietnam War. PA training programs served as an efficient means to allow these veterans to “retool” their skills for civilian practice.

The American Academy of Physician Assistants defines PAs as “health professionals licensed to practice medicine with physician supervision” (Jones, 2007). PAs are usually licensed by the same state boards that license physicians, with the requirement that PAs work under the delegated authority of a physician. In practical terms, “delegated authority” means that PAs are permitted to perform many of the tasks performed by physicians as long as the tasks are performed under physician supervision. Studies of PAs in primary care settings have found that their scope overlaps with approximately 80% of the scope of work of primary care physicians. To be eligible for licensure in most states, PAs must have graduated from an accredited training program and pass the Physician Assistant National Certifying Examination, administered by the National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. Approximately 60,000 PAs are professionally active in the United States. Traditionally, the majority of PAs worked in primary care fields. However, currently only one-third of PAs now practice in primary care, with many finding employment opportunities in surgical and medical specialty fields (Jones, 2007). PAs work in diverse settings, including private physician offices, community clinics, HMOs, and hospitals.

PA training has been described as a “condensed version of medical school” (Jones, 2007). The duration of training ranges from 20 to 36 months, with an average of 27 months (Hooker, 2006). Many of the initial training programs did not award degrees and accepted applicants with varying levels of prior formal education. Currently, of the 136 accredited PA training programs in the United States, 79% award a master’s degree and require applicants to have attained a baccalaureate degree (Jones, 2007). Approximately half of PA training programs are based at academic health centers and are directly affiliated with medical schools. Several PA programs have established postgraduate training programs, typically one year in duration and focused on subspecialty training.

PA programs produce about 5,600 graduates annually, compared with the 20,500 graduates of allopathic and osteopathic medical schools. Enrollment in PA programs has grown steadily over the past decades, with the number of PA graduates more than doubling between 1990 and 2010.

Felicia Comfort has worked for 20 years as a registered nurse on hospital medical–surgical wards. Although the work has always been hard, Felicia has found it gratifying to care for patients when they are acutely ill and need the clinical skills and compassion of a good nurse. But lately the work seems even more difficult. The pressure to get patients in and out of the hospital as soon as possible has meant that the only patients occupying hospital beds are those who are severely ill and require a tremendous amount of nursing care. At age 45, Felicia finds that her back has problems tolerating the physical labor of moving patients around in bed. Making matters worse, the hospital recently decided to “re-engineer” its staffing as a cost containment strategy and has hired more nursing aides and fewer registered nurses, adding to Felicia’s work responsibilities. Felicia decides that it is time for a change. She takes a job as a visiting nurse with a home health care agency, providing services to patients after their discharge from a hospital. She likes the pace of her new job and finds the greater clinical independence refreshing after her years of dealing with rigid hospital regimentation of nurses and physicians.

Registered nurses represent the single largest health profession in the United States. In 2008, approximately 3,000,000 registered nurses were licensed in the United States (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2010). Approximately 80% of licensed registered nurses are actively employed in nursing jobs, with most of these nurses working full-time. In 2008, hospitals were the primary employment setting for 62% of nurses. Approximately 25% work in ambulatory care or other community-based settings, and 5% in long-term care facilities. The national licensing examination for registered nurses is administered by the National Council of State Boards of Nursing, a nonprofit organization comprising representatives of each of the state boards of nursing.

Historically, many nurses received their education in vocational programs administered by hospitals not integrated into colleges and universities. These programs awarded diplomas of nursing rather than college degrees and tended to have the least demanding curricula. Over time, nursing education shifted into academic institutions. Most nurses are now educated either in 2- to 3-year associate degree programs administered by community colleges, or in baccalaureate programs administered by 4-year colleges. Of nurses active in 2008, 20% received their basic nursing training in diploma programs, 45% in associate degree programs, and 34% in baccalaureate degree programs (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2010). Many nursing leaders have called for nursing education to move almost completely to baccalaureate-level programs. At least one study has found that patient outcomes are better when hospitals are staffed with baccalaureate, trained nurses (Aiken et al, 2003). Of the nurses sitting for the national licensing examination in 2005, only 4% attended diploma programs. However, associate degree programs have remained a more affordable and accessible option than baccalaureate programs for many students, with nearly twice as many new registered nurses coming from community college programs as from baccalaureate programs.

Enrollment in registered nurse training programs has had a cyclical pattern over recent decades, corresponding to perceptions of surpluses and shortages in the labor market for nurses. The number of US-educated nurses taking the national licensing examination for the first time (a proxy for new nurse graduates) increased by approximately 50% between 1990 and 1995, reaching 96,610 in 1995, and then fell back to 1990 levels by 2000 (National Council of State Boards of Nursing, 2006). Graduation numbers have recently rebounded in response to aggressive advertising campaigns promoting nursing as a career, such as the Campaign for Nursing’s Future led by the Johnson & Johnson Company, and large increases in starting salaries for nurses. In 2006, nearly 110,000 nurses graduated from US programs (National Council of State Boards of Nursing, 2006).

Historically, most registered nurses in the United States were educated at US schools. However, as the numbers of US nursing graduates decreased in the late 1990s and hospital demand for nurse labor increased, growing numbers of foreign-educated nurses began entering the US health workforce. Unlike the situation for physicians, international nursing school graduates do not have to undergo training in the United States to become eligible for licensure. They may sit for the US registered nurse licensing examination, and upon passing the examination may apply for an occupational visa to work as a nurse. According to Dr. Linda Aiken, the United States has now become the “world’s largest importer of nurses,” with approximately 15,000 internationally trained nurses passing the US licensing examination in 2005 (Aiken, 2007). Approximately one-third of internationally educated nurses in the United States immigrated from a single nation, the Philippines. This recent upswing in nurse immigration has raised the same concerns about a brain drain from developing nations that has been voiced about physician immigration.

Felicia Comfort has now been working as a home care nurse for 2 years. She has taken on growing responsibility as a case manager for many home care patients with chronic, debilitating illnesses, coordinating services among the physicians, physical therapists, social workers, and other personnel involved in caring for each patient. She decides that she would like to become the primary caregiver for these types of patients, and applies to a nurse practitioner training program in her area. After completing her 2 years of nurse practitioner education, she finds a job as a primary care clinician at a geriatric clinic.

Eight percent of registered nurses in the United States have obtained advanced practice education in addition to their basic nursing training (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2010). Advanced practice nurses include clinical nurse specialists, nurse anesthetists, clinical nurse midwives, and nurse practitioners. The approximately 140,000 professionally active nurse practitioners represent the largest single group of advanced practice nurses.

Nurse practitioner education typically involves a 2-year master’s degree program for individuals who previously attained a baccalaureate degree in nursing. Education emphasizes primary care, prevention, and health promotion, preparing nurse practitioners for a broad scope of clinical practice, although some training programs also prepare nurse practitioners for work in non–primary care fields. Approximately 50% to 60% of nurse practitioners work in primary care settings.

Many nurse practitioner programs were established in the 1970s with federal funding as part of the same national effort to boost the number of primary care clinicians that gave rise to PA training programs. Enrollment in nurse practitioner programs grew slowly in the 1980s and exploded in the 1990s, with the number of nurse practitioner training programs more than doubling between 1992 and 1997. Whereas 1500 nurse practitioners graduated in 1992, more than 8000 graduated in 1997 (Hooker and Berlin, 2002). Unlike the trend for PAs, the number of annual nurse practitioner graduates has decreased in recent years, falling to approximately 6500 graduates in 2005 (Hooker, 2006); the number of graduates is projected to decrease further to 4000 annually by 2015 (Robert Graham Center, 2005). The causes of this decrease are multifactorial, including an initial pent-up demand for advanced practice training among the existing pool of registered nurses that was met by the expansion of programs in the 1990s, leaving a lower “steady state” demand once the initial demand was met, and increases in salaries for registered nurses that has lessened the additional earnings that may be gained by advanced practice training.

Licensing and related regulations for nurse practitioners are less uniform across states than those for physicians, physician assistants, and registered nurses. Slightly more than half of state nursing boards require nurse practitioners to have attained a master’s degree, but other states accept less extensive training (Christian et al, 2007). Rather than a single national licensing examination for all nurse practitioners, certification examinations are administered by different organizations and are specialty-specific, akin to medical specialty board certification. State boards of nursing also vary in the scope of practice they allow nurse practitioners. Most states require that nurse practitioners work in collaboration with a physician, usually with written practice protocols in place. Eleven states have more liberal regulations permitting nurse practitioners to practice with complete independence from physicians, while at the other extreme, 10 states require physicians to directly supervise nurse practitioners (Christian et al, 2007).

Similar to physician assistants, nurse practitioners working in primary care settings typically perform approximately 80% of the types of tasks performed by physicians. Two meta-analyses provide evidence that nurse practitioners can deliver care of equivalent quality to that delivered by primary care physicians (Brown and Grimes, 1995; Horrocks et al, 2002), with the caveat that most studies reviewed included small numbers of clinicians and few examined long-term outcomes for patients with chronic illness or complex conditions.

Much of the initial impetus for developing training programs for both nurse practitioners and PAs in the 1960s was to create substitutes for physicians in an era when there was a perceived shortage of physicians, especially in primary care fields. As concerns about a physician shortage waned in subsequent decades and the era of cost containment arrived, substitution came to mean less a matter of filling shortages than of finding a less expensive type of clinician to substitute for physician labor. A different view of nurse practitioners and PAs sees them less as physician substitutes than as complements in a health care team that includes a variety of personnel. In this view, each profession brings its own unique training and skills to create a health care team in which the whole is more than the sum of its parts (Wagner, 2000). For example, care of patients with chronic diseases such as diabetes is enhanced by multidisciplinary teams (Grumbach and Bodenheimer, 2004). In these types of teams, nurse practitioners often play a leading role by providing care management, health promotion, and instruction in patient self-care, while physicians focus more on medication management and treatment of acute complications.

The boldest effort to promote advance practice nurses as substitutes for physicians comes from proponents of doctoral-level professional degrees for nurses, known as doctor of nursing practice (DrNP) degrees. A few DrNP training programs have been established in the United States, involving a 4-year graduate education experience following the initial baccalaureate nursing training. Leaders of these programs have articulated the vision of producing nursing graduates carrying the title of “doctor” who will be able to practice autonomously with a scope equivalent to that of physicians, including independent practice in acute care hospital settings. Whether there will be ample numbers of registered nurses interested in pursuing this level of training, along with sufficient liberalization of state scope of practice regulations, to actualize this vision for DrNPs in the health workforce in the United States remains to be determined.

Rex Hall has worked for 5 years as a pharmacist at a chain drug store. He is not sure that his extensive professional education and skills as a pharmacist are being fully utilized in his current job. Some of his time is spent discussing possible drug interactions with physicians and suggesting alternative drug regimens, as well as counseling patients about side effects and proper use of their medications. But too much of his time is taken up answering calls from physicians and patients who are ordering prescription refills, counting out pills, filling pill bottles, and figuring out which medications are covered by which health plan. He sees a job posting for a new pharmacist position at a local hospital. The job description states that the pharmacist will review drug use in the hospital and develop strategies to work with physicians, nurses, and other staff to minimize drug errors and inappropriate prescribing practices. Rex decides to apply for the job.

Pharmacists constitute the nation’s third largest health care profession. About 250,000 pharmacists were actively practicing in 2010 (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2008b). Although historically most pharmacists were educated in baccalaureate degree programs, in 2004 all programs were required to extend the training period by 1 to 2 years and award Doctorate of Pharmacy degrees. Pharmacy education is in a period of expansion, with the number of accredited schools increasing from 82 in 2000 to 119 in 2011, and the number of graduates growing from 7300 in 2000 to 11,500 in 2010 (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2008b). Approximately 60% of pharmacists work in retail pharmacies, mostly as employees rather than as owners. Over the past decades, drug store chains such as Walgreens and Longs have largely displaced the independently owned pharmacy. Hospitals are the second largest employer of pharmacists, with HMOs and other managed care organizations, long-term care facilities, and clinics also offering practice settings for pharmacists. The content of pharmacists’ work is changing, as noted in the vignette above and in a further discussion later in this chapter.

Social work is a growing profession, with the number of social workers projected to increase from 642,000 in 2008 to 745,000 in 2018; 43% of social workers are dedicated to health care, with about half of these in the fields of mental health and substance abuse. Social workers are trained in assessment skills, diagnostic impressions, psychosocial support to patients and families; and assistance with navigation of the health and social service systems including transitions between hospital, extended care facilities, and home. Some specific tasks carried out by social workers include assessing patients’ personal, behavioral, and family/home/job situation for the health care team, connecting patients to durable medical equipment and in-home services, finding placements for hospital in-patients unable to go home, helping patients to get health insurance and other community services, investigating possible neglect or abuse, and counseling patients on healthy behavior change (Kitchen and Brook, 2005).

The minimum educational requirement is a bachelor’s degree, but most social work positions in the health care field require a masters in social work plus state licensure. Licensed clinical social workers (LCSWs) must have at least a master’s degree plus 2 years of academic and practical experience in the field, during which they serve as members of care teams in hospital, primary care, and behavioral health settings. LCSWs may be generalists or be specialized in the management of geriatric patients, children, or persons with developmental disabilities, mental health, and substance abuse diagnoses.

Justin Case began his premed studies in college in 1993. He was taken aback one morning to read an article in the newspaper reporting that a prestigious national commission had just issued a report declaring that the United States was training too many physicians and that medical schools should reduce their enrollment by 25%. Nonetheless, he pressed on in his studies, medical schools did not decrease the number of first-year positions, and Justin succeeded in gaining admission to medical school. By the time he finished his residency training in internal medicine in 2004, he was hearing reports that the United States was facing a shortage of physicians and he received many offers to join medical practices as a primary care internist. However, he opted to do a fellowship in cardiology at a prominent cardiac center in Miami, FL. One of his classmates warned him that Miami already had more cardiologists than most cities of comparable size. Justin told his friend, “I’m not worried about finding a good job in Miami when I finish my fellowship. Everyone tells me that there will always be more than enough work for interventional cardiologists in Florida.”

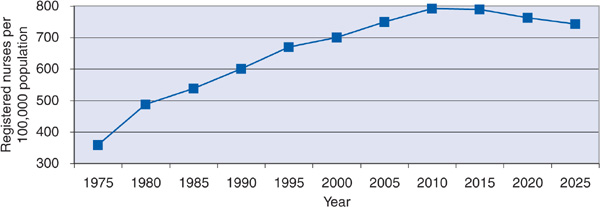

The supply of health workers in all the professions discussed in this chapter has been growing over past decades (Figures 7–1 to 7–3). Between 1975 and 2005, the number of active registered nurses per capita in the United States nearly doubled, the number of physicians per capita grew by approximately 75%, and the number of pharmacists per capita increased by approximately 50%. Increases in the supply of PAs and nurse practitioners have been even more dramatic. For physicians, virtually all the growth in supply is accounted for by increasing numbers of non–primary care specialists. Interestingly, although supply has steadily increased during these years, health workforce analysts have alternated between sounding alarms about shortages and surpluses of physicians and nurses. For example, in the 1980s and 1990s, several commissions warned of a surplus of physicians in the United States (Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee, 1981; Pew Health Professions Commission, 1995; Council on Graduate Medical Education, 1996). By the early years of the twenty-first century, some policy analysts were declaring a physician shortage (Council on Graduate Medical Education, 2005). Similarly, concerns about an oversupply of nurses in the mid-1990s were supplanted in 1998 by declarations of a nursing shortage (Buerhaus et al, 2000).

Figure 7–1. Supply of practicing physicians in the United States. Note: Includes patient care physicians who have completed training, and excludes physicians employed by the federal government (Council on Graduate Medical Education (COGME). Patient Care Physician Supply and Requirements: Testing COGME Recommendations. US Department of Health and Human Services; 1996 [HRSA-P-DM 95–3].)

Figure 7–2. Supply of active registered nurses per 100,000 population in the United States. (Peter I. Buerhaus, PhD, RN, FAAN, Douglas O. Staiger, PhD, and David I. Auerbach, PhD, The Future of the Nursing Workforce in the United States: Data, Trends and Implications, 2009: Jones & Bartlett Publishers, Sudbury, MA. www.jbpub.com. Reprinted with permission.)

Figure 7–3. Supply of active pharmacists per 100,000 population in the United States. (Bureau of Health Professions. The Pharmacist Workforce. A Study of the Supply and Demand for Pharmacists. Rockville, MD: Health Resources and Services Administration; 2000.)

What explains why perceptions turned from surplus to shortage when supply was continuing to increase? One concern was that overall supply trends might present a misleading picture of the actual labor participation of health care professionals. For example, female physicians work on average fewer hours per week than male physicians. Women constitute a growing share of the physician workforce, and therefore head counts of the number of practicing physicians may overstate the full-time equivalent supply of physicians. In nursing, concerns were voiced that overly stressful working conditions on hospital wards were driving licensed nurses out of the workforce. This concern was magnified by the fear that the sudden plummeting of enrollment in nursing schools portended a major downturn in entry of newly trained nurses into the workforce.

However, the supply of health care professionals is only one part of the equation for determining the adequacy of the workforce. The other part of the equation is a judgment about how many physicians, nurses, or pharmacists are actually required. Even when the supply of health care professionals per capita is growing, there may be a perception of a workforce shortage if the requirements for these workers are judged to be increasing more rapidly than supply. There are two general schools of thought about how to define health workforce requirements (Grumbach, 2002). One view considers market demand as the arbiter of workforce requirements. According to this view, if there is unmet market demand for, let us say, nurses, as indicated by many vacant nursing positions at hospitals, then a shortage exists. Or, to the contrary, if many nurses are unemployed or underemployed, a surplus exists. An alternative approach defines workforce requirements on the basis of population need rather than market demand. For example, a need-based approach for nursing would attempt to evaluate whether a certain level of nursing supply optimizes patient outcomes, such as by determining whether higher registered nurse staffing levels for a given volume and acuity of hospital inpatients result in fewer medication errors and hospital-acquired infections and better overall patient outcomes.

In the case of registered nursing, both demand and need perspectives converged to conclude that a shortage existed in the late 1990s (Bureau of Health Professions, 2002). As the intensity of hospital care increased and hospitals sought more highly trained registered nurses to staff their facilities, vacancy rates increased for hospital nurses. In response, hospitals began to increase wages to attract nurses into the workforce. Researchers around this time also began to produce evidence that lower levels of registered nurse staffing in hospitals were associated with worse clinical outcomes for hospitalized patients (Aiken et al, 2002; Needleman et al, 2002), suggesting a true medical need for more registered nurses in hospitals. One state, California, proceeded to codify a need-based approach to nurse supply by enacting legislation requiring a minimum nurse staffing level per occupied hospital bed (Spetz, 2004). In response to concerns about a nurse shortage, comprehensive strategies have been implemented that appear to be succeeding in attracting more applicants to nursing programs, increasing enrollment in these programs, and increasing the proportion of licensed nurses who are working as nurses. These strategies include actions by private entities, such as hospitals increasing wages for nurses and the Johnson & Johnson–sponsored advertising campaign mentioned above, and actions by government agencies, such as appropriating more funds for expansion of community and state college nursing program capacity.

The case of the physician workforce has been less straightforward. While most nurses work as employees of hospitals or other employers, most physicians are self-employed or part-owners of a medical group that acts as their employer, making vacancy rates or other typical labor market metrics less reliable indicators of the demand for physicians. Moreover, physicians’ authority and influence over medical care give them considerable market power and create opportunities for supplier-induced demand (see Chapter 9), particularly when costs are covered by third-party payers. In a health care environment like that in the United States, in which demand for physician labor may be almost limitless, physicians tend to keep busy even as supply continues to rise. Dr. Richard Cooper has been the most vocal advocate of the position that the United States currently faces a physician shortage, based on his view that the public’s demand for physician services is increasing rapidly because of an aging population and the expanding national economy, while growth in physician supply per capita in the United States is beginning to level off (Cooper et al, 2002). Countering this view has been research that raises questions about whether the public really needs and benefits from more physicians, particularly more specialists. Studies comparing patient outcomes across regions in the United States have found that while a very low supply of physicians is associated with higher mortality, once supply is even modestly greater, patients derive little further survival benefit (Goodman and Grumbach, 2008). For example, mortality rates for high-risk newborns are worse in regions with a very low supply of neonatologists than in regions with a somewhat greater supply, but above that level, further increases in the supply of neonatologists are not associated with better clinical outcomes for newborns (Goodman et al, 2002). At the other age extreme, Medicare beneficiaries residing in areas with high physician supply do not report better access to physicians or higher satisfaction with care and do not receive better quality of care (Goodman and Grumbach, 2008). One exception to these patterns is when studies focus on primary care physician supply, rather than on overall physician supply or the supply of specialists. These studies tend to find that patient outcomes and quality of care are better in regions with a more primary care-oriented physician workforce (Baicker and Chandra, 2004; Starfield et al, 2005). Proponents of a need-based approach to physician workforce planning argue that because much of physician training is supported by tax dollars, and because there is little true market restraint on demand for medical care, society should plan physician supply based on considerations of quality, affordability, and prioritization of health care services informed by the type of research evidence cited above (Grumbach, 2002).

In assessing the adequacy of health care professional supply, it is important not just to count the number of workers, but to examine how these workers are deployed. The quest for effective deployment of the workforce has been characterized using the following analogy: “Before adding another spoonful of sugar to your tea, first stir up the sugar already in your tea cup.” In other words, does the health system make the most of its existing supply of highly trained health care professionals? The case of the pharmacist workforce highlights this issue. As has been the case for nurses and physicians, concerns have recently been raised about a shortage of pharmacists. One of the factors cited is the steep rise in the prescribing of medications, which may be considered an indicator of the demand for pharmacists. Approximately 3.6 billion prescriptions were dispensed in 2005, 70% more than in 1994 (US Health and Human Services, 2008b). The estimated number of prescriptions filled per pharmacist in retail pharmacies grew from 17,400 in 1992 to 22,900 in 1999 (Bureau of Health Professions, 2000). In response, pharmacies sought to hire more pharmacists, and between 1998 and 2000, the number of unfilled pharmacist positions in chain store pharmacies more than doubled (Bureau of Health Professions, 2000; Cooksey et al, 2002). Partly in response to increased output from pharmacy schools, the percentage of pharmacist employment positions unfilled dropped from 9% to 5% between 2000 and 2004 (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2008b).

Although these trends would suggest a shortage of pharmacists based on a traditional demand model, some observers have questioned whether the existing supply of pharmacists is optimally deployed. Many pharmacists still spend a great deal of time performing the basic “pill counting” tasks of drug dispensing. Should pharmacists continue to perform most dispensing functions, or would their extensive training be better utilized in more clinically challenging activities—especially now that all newly graduated pharmacists in the United States are required to have doctoral-level training? The occupation of pharmacy technician has been developed in the United States to assist pharmacists with drug dispensing (Cooksey et al, 2002). An estimated 69% of pharmacists’ time is spent on activities that properly trained technicians could perform—counting, packaging, and labeling prescriptions, and resolving third-party insurance issues. Greater use of properly supervised pharmacy technicians might increase the productivity of the existing pharmacists. In addition, innovations in automation of pill dispensing could reduce pharmacist workload. Delegating more tasks to pharmacy assistants and automated systems would allow pharmacists to optimize their clinical training and skills for patient counseling about medications, collaborating on patient safety programs to reduce the epidemic of medication errors, monitoring drug use for chronic disease management programs, and participating in multidisciplinary clinical teams in both hospitals and ambulatory settings. These same types of concerns have been raised about whether other health care professionals are being deployed with maximum efficiency and productivity and working at their highest level of skill. For example, new models of primary care are emphasizing that many preventive and chronic care tasks traditionally performed by physicians could be delegated to medical assistants and assisted by electronic technologies (Bodenheimer and Grumbach, 2007), allowing more productive use of the work effort of primary care clinicians.

Dr. Jenny Wong works as a general internist for the Suburbia Medical Group. She never has to check her schedule in advance, because she knows that every appointment is always booked, not to mention the last minute add-ons. As one of only two women in a group of eleven primary care physicians, she is in demand. In particular, female patients in the practice have sought her out to become their primary care physician. While gratified to be responding to this demand, Dr. Wong also finds it a bit daunting. She senses that her patients expect her to spend more time with them to explain diagnoses and treatments and discuss their overall well-being. But Dr. Wong has the same 15-minute appointment times as every other physician in the practice and continually finds herself falling behind in her schedule. Today Dr. Wong is feeling especially stressed. She is scheduled to meet at lunchtime with the director of Suburbia Medical Group to discuss plans for her impending maternity leave. She knows he will not take kindly to her intention of taking 4 months off after the birth of her child.

Historically, most physicians and pharmacists in the United States have been men, and most nurses women. For physicians and pharmacists, this demographic pattern is in the midst of a dramatic change. In 1970, 13% of pharmacists were women, but by 2010, more than half of pharmacists were women. The proportion of women among physicians increased from 8% in 1970 to more than 30% in 2010 (Figure 7–4). The figures are even more dramatic when examining the makeup of current students in training: women constituted 47% of medical students and 61% of pharmacy students in 2010. In contrast, nursing has long been a profession mainly comprising women, and this is changing very slowly. In 2008, only 10% of registered nurses were men, up slightly from 5% in 1996.

Figure 7–4. Women as a percentage of physicians, nurses, and pharmacists in the United States. (US Department of Health and Human Services. The Physician Workforce: Projections and Research into Current Issues Affecting Supply and Demand. Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions, 2008a. US Department of Health and Human Services. The Adequacy of Pharmacist Supply, 2004–2030. Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions, 2008b. US Department of Health and Human Services. The Registered Nurse Population. Findings from the 2008 National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses. Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions, 2010.)

As noted above, women, on average, work fewer hours per week than men and are more likely to work on a part-time basis. However, the practices of male and female health care professionals differ in ways other than simply the number of hours worked. Female physicians attract more female patients, in part because female patients highly value more time spent and clearer explanations from their physicians than do male patients, and female physicians spend more time with their patients than do male physicians. Several studies have shown that female physicians deliver more preventive services than male physicians, especially for their female patients (Lurie et al, 1993). Female physicians appear to communicate differently with their patients, with both adults and children, being more likely to discuss lifestyle and social concerns, and to give more information and explanations during a visit (Elderkin-Thompson and Waitzkin, 1999; Roter et al, 2002). Female physicians are more likely to involve patients in medical decision-making than male physicians (Cooper-Patrick et al, 1999).

Cynthia Cuidado is the first person in her family to go to college, much less the first to become a health professional. A large contingent of her extended family celebrates her graduation from her master’s degree family nurse practitioner training program. Although HMOs in the city where Cynthia trained had several open positions for nurse practitioners, she has decided to take a job at a migrant farm worker clinic in a rural community near where she grew up.

The United States is a nation of growing racial and ethnic diversity. According to the 2010 US census, African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans now account for nearly one-third of the population, yet the health professions fail to reflect the rich racial and ethnic diversity of the US population. Only about 10% of pharmacists, 9% of physicians, 8% of physician assistants, 10% of nurses, and 5% of dentists are from these three underrepresented racial and ethnic groups (Grumbach and Mendoza, 2008).

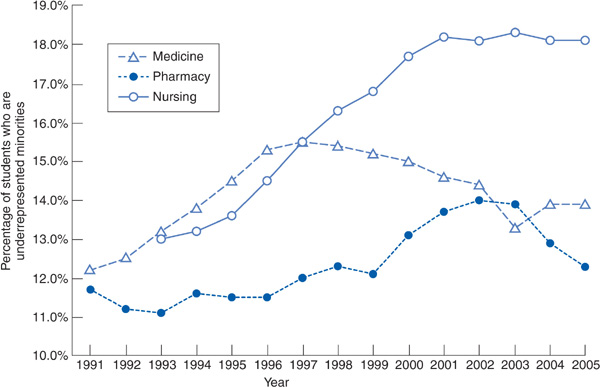

Health professions have made efforts to increase the number of underrepresented minorities enrolling in their training programs. In nursing, these efforts appear to be paying dividends (Figure 7–5). Underrepresented minorities as a proportion of students in baccalaureate nursing programs increased from 12.2% in 1991 to 18.1% in 2005. Medical schools have experienced a different trend. Underrepresented minorities as a percentage of medical students increased in the early 1990s, from 12.2% in 1991 to 15.5% in 1997. However, the percentage of underrepresented minority medical students dropped after 1997, falling to 13.9% in 2005. The decrease in underrepresented minority student enrollment in medical schools beginning in the mid-1990s coincided with the onset of a wave of antiaffirmative action policies, such as Proposition 209 in California and the Hopwood vs. Texas federal court ruling that curtailed the ability of university admissions committees to give special consideration to applicants’ race and ethnicity (Grumbach and Mendoza, 2008). Pharmacy schools also showed little net increase in underrepresented minority enrollment, with 11% of pharmacy students in 1990 and 2010 being from underrepresented minority groups.

The problem of underrepresented minorities in the health professions is an especially compelling policy concern. As discussed in Chapter 3, minority communities experience poorer health and access to health care compared with communities populated primarily by non-Latino whites. Minority health care professionals are more likely to practice in underserved minority communities and serve disadvantaged patients, such as the uninsured and those covered by Medicaid (Moy and Bartman, 1995; Cantor et al, 1996; Komaromy et al, 1996; Mertz and Grumbach, 2001). Research has also found salutary effects of ethnically concordant relationships between minority patients and health care professionals on the use of preventive services, patient satisfaction, and ratings of the physician’s participatory decision-making style (Saha et al, 2000; Cooper et al, 2003; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2006). Some studies focusing specifically on language concordance when patients have limited English proficiency have also found that access to language concordant clinicians is associated with better patient experiences and outcomes such as reductions in patient reports of medication errors (Wilson et al, 2005). Thus, the underrepresentation of minorities is not just a matter of equality of opportunity; it has profound implications for racial and ethnic disparities in access to care and in health status.

Figure 7–5. Underrepresented minorities as a percentage of students in selected health professions in the United States. Note: Medical schools include only allopathic schools. (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, Enrollment and Graduations in Baccalaureate & Graduate Programs in Nursing; Association of American Medical Colleges, Data Warehouse. Applicant Matriculant File. Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, Profile of Pharmacy Students Application Trends; 2007.)

An intricate array of educational pathways, accreditation of teaching institutions, and credentialing of individuals to legally practice a healing profession defines the composition of the health workforce. Access, cost, and quality—the three overriding issues in health care—are all inextricably linked to trends in the health care workforce. An inadequate supply of health care professionals may impede patients’ access to care or compromise the quality of care. But increases in the supply of health care professionals may fuel intolerable escalation of health care costs. It is not surprising, then, to find disagreement about whether a health system has enough, too few, or too many of a particular class of health care professionals. The recent consensus in the United States about a shortage of registered nurses is one of the rare instances in which analyses based on demand models and on need models arrived at similar conclusions. The current debate over the adequacy of the physician workforce in the United States is more typical of the challenges in coming to agreement about the adequacy of supply, revealing how different frames of reference for judging the nation’s requirement for health care professionals lead to different policy conclusions. In addition to the overall supply of health professionals, the demographic composition of the workforce in terms of gender and race–ethnicity also has important policy implications.

Although making definitive determinations about the “right” number of health care professionals often proves elusive, two conclusions may be made with more confidence. First, all health systems should deploy their workers in a manner that makes the best use of their training and skills, creating practice structures that allow each health care professional to operate at his or her highest level of capability and ensuring that those patients most in need benefit from the clinical expertise of the health care professionals working in the system. Most systems fall short of this goal and have not fully “stirred the sugar in the cup of tea,” failing to continually reassess and adapt the roles and responsibilities of the members of the health care team to the changing needs of modern-day health systems. Second, all systems need to ensure that their health professionals are highly qualified and embrace a culture of continuous quality improvement (discussed in Chapter 10). To echo the opening of this chapter, a health care system is only as good as the people working in it.

Aiken LH. U.S. nurse labor market dynamics are key to global nurse sufficiency. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:1299.

Aiken LH et al. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA. 2002;288:1987.

Aiken LH et al. Educational levels of hospital nurses and surgical patient mortality. JAMA. 2003;290:1617.

Baicker K, Chandra A. Medicare spending, the physician work-force, and beneficiaries’ quality of care. Health Affairs Web Exclusive. 2004;(suppl):W184–W197.

Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K. Improving Primary Care: Strategies and Tools for a Better Practice. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2007.

Brown SA, Grimes DE. A meta-analysis of nurse practitioners and nurse midwives in primary care. Nurs Res. 1995;44:332.

Buerhaus PI et al. Implications of an aging registered nurse workforce. JAMA. 2000;283:2948.

Buerhaus PI et al. The Future of the Nursing Workforce in the United States: Data, Trends and Implications, 2009. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 2008.

Bureau of Health Professions. The Pharmacist Workforce. A Study of the Supply and Demand for Pharmacists. Rockville, MD: Health Resources and Services Administration; 2000.

Bureau of Health Professions. Projected Supply, Demand, and Shortages of Registered Nurses, 2000–2020. Rockville, MD: Health Resources and Services Administration; 2002.

Cantor JC et al. Physician service to the underserved: Implications for affirmative action in medical education. Inquiry. 1996;33:167.

Christian S et al. Overview of Nurse Practitioner Scopes of Practice in the United States. University of California, San Francisco, Center for the Health Professions; 2007. http://www.acnpweb.org/files/public/UCSF_Discussion_2007.pdf. Accessed November 14, 2011.

Cooksey JA et al. Challenges to the pharmacist profession from escalating pharmaceutical demand. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(5):182.

Cooper RA et al. Economic and demographic trends signal an impending physician shortage. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21:140.

Cooper LA et al. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003:139:907.

Cooper-Patrick L et al. Race, gender and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA. 1999;282:583.

Council on Graduate Medical Education (COGME). Eighth Report: Patient Care Physician Supply and Requirements: Testing COGME Recommendations. Rockville, MD: Council on Graduate Medical Education; 1996.

Council on Graduate Medical Education (COGME). Sixteenth Report: Physician Workforce Policy Guidelines for the United States, 2000–2020. Rockville, MD: Council on Graduate Medical Education; 2005.

Elderkin-Thompson B, Waitzkin H. Differences in clinical communication by gender. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:112.

Goodman D et al. The relation between the availability of neonatal intensive care and neonatal mortality. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1538–1544.

Goodman D, Grumbach K. Does having more physicians lead to better health system performance? JAMA. 2008;299:335.

Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee. Summary Report. DHHS Pub. No. (HRA) 81–651. Washington, DC; 1981.

Grumbach K. Fighting hand to hand over physician workforce policy. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(5):13.

Grumbach K, Bodenheimer T. Can health care teams improve primary care practice? JAMA. 2004;291:1246.

Grumbach K, Mendoza R. Disparities in human resources: Addressing the lack of diversity in the health professions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(2):413.

Hooker RS. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners: the United States experience. Med J Aust. 2006;185:4.

Hooker RS, Berlin LE. Trends in the supply of physician assistants and nurse practitioners in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(5):174.

Horrocks S et al. Systematic review of whether nurse practitioners working in primary care can provide equivalent care to doctors. BMJ. 2002;324:819.

Iglehart J. Health reform, primary care, and graduate medical education. N Engl J Med 2010;363:584.

Jones PE. Physician assistant education in the United States. Acad Med. 2007;82:882.

Kitchen A, Brook J. Social work at the heart of the medical team. Soc Work Health Care. 2005;40:1

Komaromy M et al. The role of black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care for underserved populations. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1305.

Lurie N et al. Preventive care for women: Does the sex of the physician matter? N Engl J Med. 1993;329:478.

Mertz EA, Grumbach K. Identifying communities with low dentist supply in California. J Public Health Dent. 2001;61:172.

Moy E, Bartman BA. Physician race and care of minority and medically indigent patients. JAMA. 1995;273:1515.

Mullan F. The metrics of the physician brain drain. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1850.

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. Nurse Licensure and NLCEX Examination Statistics. 2006. https://www.ncsbn.org/1236.htm.

Needleman J et al. Nurse-staffing levels and the quality of care in hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1715.

Pew Health Professions Commission. Critical Challenges. Revitalizing the Health Professions for the Twenty-First Century. San Francisco: UCSF Center for the Health Professions; December 1995.

Robert Graham Center Policy Studies in Family Medicine and Primary Care. Physician Assistant and Nurse Practitioner Workforce Trends. One-pagers, 37, 2005. http://www.aafp.org/afp/2005/1001/p1176.html. Accessed November 14, 2011.

Roter D et al. Physician gender effects in medical communication: a meta-analytic review. JAMA. 2002;288:756.

Salsberg E et al. US residency training before and after the 1997 Balanced Budget Act. JAMA. 2008;300:1174.

Saha S et al. Do patients choose physicians of their own race? Health Aff (Millwood). 2000;19(4):76.

Spetz J. California’s minimum nurse-to-patient ratios: The first few months. J Nurs Adm. 2004;34:571.

Starfield B et al. The effects of specialist supply on populations’ health: assessing the evidence. Health Aff Web Exclusives. 2005;(suppl):W5-97–W5-107.

Starr P. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. New York: Basic Books; 1982.

US Department of Health and Human Services. The Rationale for Diversity in the Health Professions: A Review of the Evidence. Health Resources and Services Administration; 2006. http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/reports/diversityreviewevidence.pdf.

US Department of Health and Human Services. The Physician Workforce: Projections and Research into Current Issues Affecting Supply and Demand. Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions, 2008a. http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/reports/physwfissues.pdf

US Department of Health and Human Services. The Adequacy of Pharmacist Supply, 2004–2030. Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions, 2008b. http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/reports/pharmsupply20042030.pdf

US Department of Health and Human Services. The Registered Nurse Population. Findings From the 2008 National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses. Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions, 2010. http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/rnsurveys/rnsurveyfinal.pdf

Wagner EH. The role of patient care teams in chronic disease management. Br Med J. 2000;320:569.

Wilson E et al. Effects of limited English proficiency and physician language on health care comprehension. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(9):800-806.