Each year in the United States, millions of people visit hospitals, physicians, and other caregivers and receive medical care of superb quality. But that’s not the whole story. Some patients’ interactions with the health care system fall short (Institute of Medicine, 1999, 2001).

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, an estimated 32,000 people died in US hospitals each year as a result of preventable medical errors (Zahn and Miller, 2003). In addition, an estimated 57,000 people in the United States died because they were not receiving appropriate health care—in most cases, because common medical conditions such as high blood pressure or elevated cholesterol are not adequately controlled (National Committee for Quality Assurance, 2010). Hospitals vary greatly in their risk-adjusted mortality rates for Medicare patients; for 2000 to 2002, if hospitals with mortality rates higher than expected reduced deaths to the levels that were expected given their patient mix, 17,000 to 21,000 fewer deaths per year would have occurred (Schoen et al, 2006).

Fatal medication errors among outpatients doubled between 1983 and 1993 (Phillips et al, 1998). Prescribing errors occur in 7.6% of outpatient prescriptions (Gandhi et al, 2005), which amounts to 228 million errors in 2004. In 2007, about 25% of elderly patient received high-risk medications (Zhang et al, 2010). Diagnostic error rates are around 10% for a variety of medical conditions (Wachter, 2010). In some primary care practices, patients are not informed about abnormal laboratory results over 20% of the time (Casalino et al, 2009).

Forty-five percent of adults do not receive recommended chronic and preventive care, and 30% seeking care for acute problems receive treatment that is contra-indicated (Schuster et al, 1998; McGlynn et al, 2003). Only 50% of people with hypertension are adequately treated (Egan, 2010). Sixty-three percent of people with diabetes are inadequately controlled (Saydah et al, 2004). In many studies, racial and ethnic minority patients experience an inferior quality of care compared with white patients (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2010). The likelihood of patients being harmed by medical negligence is almost three times as great in hospitals serving largely low-income and minority patients than in hospitals with more affluent populations (Burstin et al, 1993a; Ayanian, 1994; Fiscella et al, 2000). A recent study of multiple quality measures found that the US continues to have serious quality problems and lags behind other developed nations (Schoen et al, 2006).

A prominent Institute of Medicine report (2001) concluded that between what we know and what we do lies not just a gap, but a chasm. Quality problems have been categorized as overuse, underuse, and misuse (Chassin et al, 1998). We will first examine the factors contributing to poor quality and then explore what can be done to elevate all health care to the highest possible level.

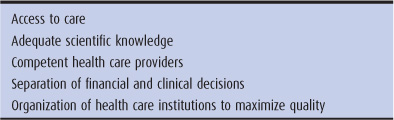

What is high-quality health care? It is care that assists healthy people to stay healthy, cures acute illnesses, and allows chronically ill people to live as long and fulfilling a life as possible. What are the components of high-quality health care? (Table 10–1)

Table 10–1. Components of high-quality care

Lydia and Laura were friends at a rural high school; both became pregnant. Lydia’s middle-class parents took her to a nearby obstetrician, while Laura, from a family on welfare, could not find a physician who would take Medicaid. Lydia became the mother of a healthy infant, but Laura, going without prenatal care, delivered a low-birth-weight baby with severe lung problems.

To receive quality care, people must have access to care. People with reduced access to care suffer worse health outcomes in comparison to those enjoying full access—the quality problem of underuse (see Chapter 3). Quality requires equality (Schiff et al, 1994).

Brigitte Levy, a professor of family law, was started on estrogen replacement in 1960 when she reached menopause. Her physician prescribed the hormone pills for 10 years. In 1979, she was diagnosed with invasive cancer of the uterus, which spread to her entire abdominal cavity in spite of surgical treatment and radiation. She died in 1980 at age 68, at the height of her career.

A body of knowledge must exist that informs physicians what to do for the patient’s problem. If clear scientific knowledge fails to distinguish between effective and ineffective or harmful care, quality may be compromised. During the 1960s, medical science taught that estrogen replacement, without the administration of progestins, was safe. Sadly, cases of uterine cancer caused by estrogen replacement did not show up until many years later. Brigitte Levy’s physician followed the standard of care for his day, but the medical profession as a whole was relying on inadequate scientific knowledge. A great deal of what physicians do has never been evaluated by rigorous scientific experiment (Eddy, 1993), and many therapies have not been adequately tested for side effects. Treatments of uncertain safety and efficacy may cause harm and cost billions of dollars each year.

Ceci Yu, age 77, was waking up at night with shortness of breath and wheezing. Her physician told her she had asthma and prescribed albuterol, a bronchodilator. Two days later, Ms. Yu was admitted to the coronary care unit with a heart attack. Writing to the chief of medicine, the cardiologist charged that Ms. Yu’s physician had misdiagnosed the wheezing of congestive heart failure and had treated Ms. Yu incorrectly for asthma. The cardiologist charged that the treatment might have precipitated the heart attack.

The provider must have the skills to diagnose problems and choose appropriate treatments. An inadequate level of competence resulted in poor quality care for Ms. Yu.

The Harvard Medical Practice study reviewed 30,000 medical records in 51 hospitals in New York State in 1984 (Studdert et al, 2004). The study found that in approximately 4% of hospital admissions, the patient experienced a medical injury (ie, a medical problem caused by the management of a disease rather than by the disease itself); this is the quality problem of misuse. A more recent study placed the percent of hospital patients experiencing a medical injury at 13.8% (Meurer et al, 2006). Medical injuries can be classified as negligent or not negligent.

Jack was given a prescription for a sulfa drug. When he took the first pill, he turned beet red, began to wheeze, and fell to the floor. His friend called 911, and Jack was treated in the emergency department for anaphylactic shock, a potentially fatal allergic reaction. The emergency medicine physician learned that Jack had developed a rash the last time he took sulfa. Jack’s physician had never asked him if he was allergic to sulfa, and Jack did not realize that the prescription contained sulfa.

Mack was prescribed a sulfa drug, following which he developed anaphylactic shock. Before writing the prescription, Mack’s physician asked whether he had a sulfa allergy. Mack had said “No.”

Medical negligence is defined as failure to meet the standard of practice of an average qualified physician practicing in the same specialty. Jack’s drug reaction must be considered negligence, while Mack’s was not. Of the medical injuries discovered in the Harvard study, 28% were because of negligence. In those injuries that led to death, 51% involved negligence. The most common injuries were drug reactions (19%) and wound infections (14%). Eight percent of injuries involved failure to diagnose a condition, of which 75% were negligent. Seventy percent of patients suffering all forms of medical injury recovered completely in 6 months or less, but 47% of patients in whom a diagnosis was missed suffered serious disabilities (Brennan et al, 1991; Leape et al, 1991).

Negligence cannot be equated with incompetence. Any good health care professional may have a mental lapse, may be overtired after a long night in the intensive care unit, or may have failed to learn an important new research finding.

Nina Brown, a 56-year-old woman with diabetes, arrived at her primary care physician’s office complaining of several bouts of chest pain over the past month. Her physician examined Ms. Brown, performed an electrocardiogram (ECG), which showed no abnormalities, diagnosed musculoskeletal pain, and recommended she take some ibuprofen. Five minutes later in the parking lot, Ms. Brown collapsed of a heart attack. The health plan insuring Ms. Brown had an incentive arrangement with primary care physicians whereby the physicians receive a bonus payment if the physicians reduce use of emergency department and referral services below the community average.

Completely healthy at age 45, Henry Fung reluctantly submitted to a treadmill exercise test at the local YMCA. The study was possibly abnormal, and Mr. Fung, who had fee-for-service insurance, sought the advice of a cardiologist. The cardiologist knew that treadmill tests are sometimes positive in healthy people. He ordered a coronary angiogram, which was perfectly normal. Three hours after the study, a clot formed in the femoral artery at the site of the catheter insertion, and emergency surgery was required to save Mr. Fung’s leg.

No one can know what motivated the physician to send Ms. Brown home instead of to an emergency department when unstable coronary heart disease was one possible diagnosis (underuse); nor can one guess what led the fee-for-service cardiologist to perform an invasive coronary angiogram of questionable appropriateness on Mr. Fung (overuse). One factor that bears close attention is the impact of financial considerations on the quantity (and thus the quality) of medical care (Relman, 2007). As noted in Chapter 4, fee-for-service reimbursement encourages physicians to perform more services, whereas capitation payment rewards those who perform fewer services.

More than 40 years ago, Bunker (1970) found that the United States performed twice the number of surgical procedures per capita than Great Britain. He postulated that this difference could be accounted for by the greater number of surgeons per capita in the United States and concluded that “the method of payment appears to play an important, if unmeasured, part.” Most surgeons in the United States are compensated by fee-for-service, whereas most in Great Britain are paid a salary. From 8% to 86% of surgeries—depending on the type—have been found to be unnecessary and have caused substantial avoidable death and disability (Leape, 1992). As an example, spinal fusion surgery increased by 77% from 1996 to 2001, though little evidence supports this procedure in many cases. Complications are frequent and rates of reoperation (because of failure to relieve pain or worsening pain) are high. Reimbursement for this procedure is greater than that provided for most other procedures performed by orthopedists and neurosurgeons (Deyo et al, 2004).

It was a nice dinner, hosted by the hospital radiologist and paid for by the company manufacturing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanners. After the meal came the pitch: “If you physicians invest money, we can get an MRI scanner near our hospital; if the MRI makes money, you all share in the profits.” One internist explained later, “After I put in my $10,000, it was hard to resist ordering MRI scans. With headaches, back pain, and knee problems, the indications for MRIs are kind of fuzzy. You might order one or you might not. Now, I do.”

Relman (2007) writes about the commercialization of medicine: “The introduction of new technology in the hands of specialists, expanded insurance coverage, and unregulated fee-for-service payments all combined to rapidly increase the flow of money into the health care system, and thus sowed the seeds of a new, profit-driven industry.”

During the 1980s, many physicians formed partnerships and joint ventures, giving them part ownership in laboratories, MRI scanners, and outpatient surgicenters. Forty percent of practicing physicians in Florida owned services to which they referred patients. Ninety-three percent of diagnostic imaging facilities, 76% of ambulatory surgery centers, and 60% of clinical laboratories in the state were owned wholly or in part by physicians. The rates of use for MRI and CT scans were higher for physician-owned compared with non-physician-owned facilities (Mitchell and Scott, 1992). In a national study, physicians who received payment for performing x-rays and sonograms within their own offices obtained these examinations four times as often as physicians who referred the examinations to radiologists and received no reimbursement for the studies. The patients in the two groups were similar (Hillman et al, 1990).

After 2000, profitable diagnostic, imaging, and surgical procedures have rapidly migrated from the hospital to free-standing physician-owned ambulatory surgery centers, endoscopy centers, and imaging centers (Berenson et al, 2006). For example, the number of CT scans performed for Medicare patients increased by 65% from 2000 to 2005; during those years, the number of MRI scans jumped by 94% (Bodenheimer et al, 2007). The number of CT scans is growing by more than 10% per year, increasing patients’ risk of radiation-related cancer (Smith-Bindman, 2010). A significant association exists between surgeon ownership of ambulatory surgery centers and a higher volume of surgeries; surgery volume increases immediately following surgeons’ acquisition of the surgicenter (Hollingsworth et al, 2010).

Moving to the other side of the overuse–underuse spectrum, payment by capitation, or salaried employment by a for-profit business, may create a climate hostile to the provision of adequate services. In the 1970s, a series of HMOs called prepaid health plans (PHPs) sprang up to provide care to California Medicaid patients. The quality of care in several PHPs became a major scandal in California. At one PHP, administrators wrote a message to health care providers: “Do as little as you possibly can for the PHP patient,” and charts audited by the California Health Department revealed many instances of undertreatment. The PHPs received a lump sum for each patient enrolled, meaning that the lower the cost of the services actually provided, the greater the PHP’s profits (US Senate, 1975).

The quantity and quality of medical care are inextricably interrelated. Too much or too little can be injurious. The research of Fisher et al (2003) has shown that similar populations in different geographic areas have widely varying rates of surgeries and days in the hospital, with no consistent difference in clinical outcomes between those in high-use and low-use areas.

The personnel cutbacks were terrible; staffing had diminished from four RNs per shift to two, with only two aides to provide assistance. Shelley Rush, RN, was 2 hours behind in administering medications and had five insulin injections to give, with complicated dosing schedules. A family member rushed to the nursing station saying, “The lady in my mother’s room looks bad.” Shelley ran in and found the patient unconscious. She quickly checked the blood sugar, which was disastrously low at 20 mg/dL. Shelley gave 50% glucose, and the patient woke up. Then it hit her—she had injected the insulin into the wrong patient.

Health care institutions must be well organized, with an adequate, competent staff. Shelley Rush was a superb nurse, but understaffing caused her to make a serious error. The book Curing Health Care by Berwick et al (1990) opens with a heartbreaking case:

She died, but she didn’t have to. The senior resident was sitting, near tears, in the drab office behind the nurses’ station in the intensive care unit. It was 2:00 AM, and he had been battling for thirty-two hours to save the life of the 23-year-old graduate student who had just suffered her final cardiac arrest.

The resident slid a large manila envelope across the desk top. “Take a look at this,” he said. “Routine screening chest x-ray, taken 10 months ago. The tumor is right there, and it was curable—then. By the time the second film was taken 8 months later, because she was complaining of pain, it was too late. The tumor had spread everywhere, and the odds were hopelessly against her. Everything we’ve done since then has really just been wishful thinking. We missed our chance. She missed her chance.” Exhausted, the resident put his head in his hands and cried.

Two months later, the Quality Assurance Committee completed its investigation.… “We find the inpatient care commendable in this tragic case,” concluded the brief report, “although the failure to recognize the tumor in a potentially curable stage 10 months earlier was unfortunate….” Nowhere in this report was it written explicitly why the results of the first chest x-ray had not been translated into action. No one knew.

One year later.… it was 2:00 AM, and the night custodian was cleaning the radiologist’s office. As he moved a filing cabinet aside to sweep behind it, he glimpsed a dusty tan envelope that had been stuck between the cabinet and the wall. The envelope contained a yellow radiology report slip, and the date on the report—nearly two years earlier—convinced the custodian that this was, indeed, garbage … He tossed it in with the other trash, and 4 hours later it was incinerated along with other useless things. (Berwick et al, 1990)

This patient may have had perfect access to care for an illness whose treatment is scientifically proved; she may have seen a physician who knew how to make the diagnosis and deliver the appropriate treatment; and yet the quality of her care was disastrously deficient. Dozens of people and hundreds of processes influence the care of one person with one illness. In her case, one person—perhaps a file clerk with a near-perfect record in handling thousands of radiology reports—lost control of one report, and the physician’s office had no system to monitor whether or not x-ray reports had been received. The result was the most tragic of quality failures—the unnecessary death of a young person.

How health care systems and institutions are organized has a major impact on health care outcomes. For example, large multispecialty group practices in 22 metropolitan areas have better-quality measures at lower cost than dispersed physician practices in those areas (Weeks et al, 2009). Studies have shown that hospitals with more RN staffing have lower surgical complication rates (Kovner and Gergen, 1998) and lower mortality rates (Aiken et al, 2002).

Oliver Hart lived in a city with a population of 80,000. He was admitted to Neighborhood Hospital with congestive heart failure caused by a defective mitral valve. He was told he needed semiurgent heart surgery to replace the valve. The cardiologist said “You can go to University Hospital 30 miles away or have the surgery done here.” The cardiologist did not say that Neighborhood Hospital performed only seven cardiac surgeries last year. Mr. Hart elected to remain for the procedure. During the surgery, a key piece of equipment failed, and he died on the operating table.

Quality of care must be viewed in the context of regional systems of care (see Chapter 6), not simply within each health care institution. In one study, 27% of deaths related to coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery at low-volume hospitals might have been prevented by referral of those patients to hospitals performing a higher volume of those surgeries (Dudley et al, 2000). Quality improves with the experience of those providing the care (Kizer, 2003; Peterson et al, 2004). Had Mr. Hart been told the relative surgical mortality rates at University Hospital, which performed 500 cardiac surgeries each year, and at Neighborhood Hospital, he would have chosen to be transferred 30 miles down the road. Not only does the volume of surgeries in a hospital matter; equally important is the volume of surgeries performed by the specific surgeon (Birkmeyer et al, 2003).

In the late 1980s, Dr. Donald Berwick (1989) and others realized that quality of care is not simply a question of whether or not a physician or other caregiver is competent. If poorly organized, the complex systems within and among medical institutions can thwart the best efforts of professionals to deliver high-quality care.

There are two approaches to the problem of improving quality … [One is] the Theory of Bad Apples, because those who subscribe to it believe that quality is best achieved by discovering bad apples and removing them from the lot.… The Theory of Bad Apples gives rise readily to what can be called the my-apple-is-just-fine-thank-you response … and seeks not understanding, but escape. [The other is] the Theory of Continuous Improvement . . . . Even when people were at the root of defects,… the problem was generally not one of motivation or effort, but rather of poor job design, failure of leadership, or unclear purpose. Quality can be improved much more when people are assumed to be trying hard already, and are not accused of sloth. Fear of the kind engendered by the disciplinary approach poisons improvement in quality, since it inevitably leads to the loss of the chance to learn.

Real improvement in quality depends … on continuous improvement throughout the organization through constant effort to reduce waste, rework, and complexity. When one is clear and constant in one’s purpose, when fear does not control the atmosphere (and thus the data), when learning is guided by accurate information … and when the hearts and talents of all workers are enlisted in the pursuit of better ways, the potential for improvement in quality is nearly boundless . . . . A test result lost, a specialist who cannot be reached, a missing requisition, a misinterpreted order, duplicate paperwork, a vanished record, a long wait for the CT scan, an unreliable on-call system—these are all-too-familiar examples of waste, rework, complexity, and error in the physician’s daily life . . . . For the average physician, quality fails when systems fail. (Berwick et al, 1989)

Good-quality care can be compromised at a number of steps along the way.

Angie Roth has coronary heart disease and may need CABG surgery. (1) If she is uninsured and cannot get to a physician, high-quality care is impossible to obtain. (2) If clear evidence-based guidelines do not exist regarding who benefits from CABG and who does not, Ms. Roth’s physician may make the wrong choice. (3) Even if clear guidelines exist, if Angie Roth’s physician fails to evaluate her illness correctly or sends her to a surgeon with poor operative skills, quality may suffer. (4) If indications for surgery are not clear in Ms. Roth’s case but the surgeon will benefit economically from the procedure, the surgery may be inappropriately performed. (5) Even if the surgery is appropriate and performed by an excellent surgeon, faulty equipment in the operating room or poor teamwork among the operating room surgeons, anesthesiologists, and nurses may lead to a poor outcome.

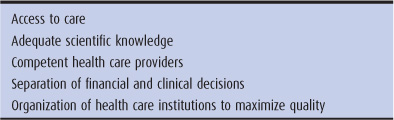

The Institute of Medicine, in its influential 2001 report Crossing the Quality Chasm, conceptualized six core dimensions of quality: safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable. These dimensions, defined in greater detail in Table 10–2, are consistent with the components of quality discussed earlier.

Table 10–2. Quality aims as defined by the Institute of Medicine

Several infants at a hospital received epinephrine in error and suffered serious medical consequences. An analysis revealed that several pharmacists had made the same mistake; the problem was caused by the identical appearance of vitamin E and epinephrine bottles in the pharmacy. This was a system error.

An epidemic of unexpected deaths on the cardiac ward was investigated. The times of the deaths were correlated with personnel schedules, leading to the conclusion that one nurse was responsible. It turned out that she was administering lethal doses of digoxin to patients. This was not a system error.

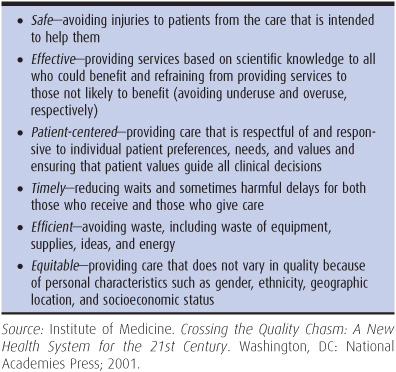

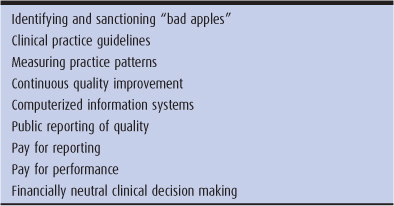

Quality issues must be investigated to determine if they are system errors or problems with a particular caregiver. Traditionally, quality assurance has focused on individual caregivers and institutions in a “bad apple” approach that relies heavily on sanctions. More recently, quality has been viewed through the lens of the continuous quality improvement (CQI) model that seeks to enhance the clinical performance of all systems of care, not just the outliers with flagrantly poor quality of care. The move to a CQI model has required development of more formalized standards of care that can be used as benchmarks for measuring quality, and more systematic collection of data to measure overall performance and not just performance in isolated cases (Tables 10–2).

Traditionally, the health care system has placed great reliance on educational institutions and licensing and accrediting agencies to ensure the competence of individuals and institutions in health care. Health care professionals undergo rigorous training and pass special licensing examinations intended to ensure that caregivers have at least a basic level of knowledge and competence. However, not all individuals who have successfully completed their education and passed licensing examinations are competent clinicians. In some cases, this reflects a failure of the educational and licensing systems. In other cases, clinicians may have been competent practitioners at the time they took their examinations, but their skills lapsed or they developed impairment from alcohol or drug use, depression, or other conditions (Leape and Fromson, 2006).

Licensing agencies in the United States do not require periodic reexaminations. In most cases, licensing boards only respond to patient or health care professional complaints about negligent or unprofessional behavior. Many organizations that confer specialty board certification require physicians to pass examinations on a periodic basis to maintain active specialty certification. Some specialties also require physicians to perform and document systematic quality reviews of their own clinical practices for maintenance of certification. However, while some hospitals may require active specialty certification for a physician to be granted privileges to practice in the hospital, certification is not required for medical licensure, diluting some of the consequences of not participating in specialty recertification.

The traditional approach to quality assurance has also relied heavily on peer pressure within hospitals, HMOs, and the medical community at large. Peer review is the evaluation by health care practitioners of the appropriateness and quality of services performed by other practitioners, usually in the same specialty. Peer review has been a part of medicine for decades (eg, tissue committees study surgical specimens to determine whether appendectomies and hysterectomies have actually removed diseased organs; credentials committees review the qualifications of physicians for hospital staff privileges). But peer review moved to center stage with the passage of the law enacting Medicare in 1965.

Medicare anointed the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals (now named simply the Joint Commission) with the authority to terminate hospitals from the Medicare program if quality of care was found to be deficient. The Joint Commission requires hospital medical staff to set up peer review committees for the purpose of maintaining quality of care.

The Joint Commission uses criteria of structure, process, and outcome to assess quality of care. Structural criteria include such factors as whether the emergency department defibrillator works properly. Criteria of process include whether medical records are dictated and signed in a timely manner, or if the credentials committee keeps minutes of its meetings. Outcomes include such measures as mortality rates for surgical procedures, proportions of deaths that are preventable, and rates of adverse drug reactions and wound infections. Medicare also contracts with quality improvement organizations (QIOs) in each state to promote better quality of care among physicians caring for Medicare beneficiaries.

Angela Lopez, age 57, suffered from metastatic ovarian cancer but was feeling well and prayed she would live 9 months more. Her son was the first family member ever to attend college, and she hoped to see him graduate. It was decided to infuse chemotherapy directly into her peritoneal cavity. As the solution poured into her abdomen, she felt increasing pressure. She asked the nurse to stop the fluid. The nurse called the physician, who said not to worry. Two hours later, Ms. Lopez became short of breath and demanded that the fluid be stopped. The nurse again called the physician, but an hour later Ms. Lopez died. Her abdomen was tense with fluid, which pushed on her lungs and stopped circulation through her inferior vena cava. The quality assurance committee reviewed the case as a preventable death and criticized the physician for giving too much fluid and failing to respond adequately to the nurse’s call. The physician replied that he was not at fault; the nurse had not told him how sick the patient was. The case was closed.

The traditional quality assurance strategies of licensing and peer review have not been particularly effective tools for improving quality. Peer review often adheres to the theory of bad apples, attempting to discipline physicians (to remove them from the apple barrel) for mistakes rather than to improve their practice through education. The physician who caused Ms. Lopez’s preventable death responded to peer criticism by blaming the nurse rather than learning from the mistake. With the hundreds of decisions physicians make each day, often in time-constrained situations, serious errors are relatively common in medical practice. Yet 42% of physicians recently surveyed had never disclosed a serious error to a patient (Gallagher et al, 2006). Hiding mistakes rather than correcting them is the legacy of a punitive quality assurance apparatus (Leape, 1994).

Even if sanctions against the truly bad apples had more teeth, these measures would not solve the quality problem. Removing the incontrovertibly bad apples from the barrel does not address all the quality problems that emanate from competent caregivers who are not performing optimally. Health care systems do need to ensure basic clinical competence and to forcefully sanction caregivers who, despite efforts at remediation, cannot operate at a basic standard of acceptable practice. But measures are also needed to “shift the curve” of overall clinical practice to a higher level of quality, not just to trim off the poor-quality outliers.

Peer reviewers frequently disagree as to whether the quality of care in particular cases is adequate or not (Laffel and Berwick, 1993). Because of these limitations, efforts are underway to formalize standards of care using clinical practice guidelines and to move from individual case review to more systematic monitoring of overall practice patterns (Table 10–3).

Table 10–3. Proposals for improving quality

Dr. Benjamin Waters was frustrated by patients who came in with urinary incontinence. He never learned about the problem in medical school, so he simply referred these patients to a urologist. In his managed care plan, Dr. Waters was known to over-refer, so he felt stuck. He could not handle the problem, yet he did not want to refer patients elsewhere. He solved his dilemma by prescribing incontinence pads and diapers, but did not feel good about it.

Dr. Denise Drier learned about urinary incontinence in family medicine residency but did not feel secure about caring for the problem. On the web, she found “Urinary Incontinence in Adults: Clinical Practice Guideline Update.” She studied the material and applied it to her incontinence patients. After a few successes, she and the patients were feeling better about themselves.

For many conditions, there is a better and a worse way to make a diagnosis and prescribe treatment. Physicians may not be aware of the better way because of gaps in training, limited experience, or insufficient time or motivation to learn new techniques. For these problems, clinical practice guidelines can be helpful in improving quality of care. In 1989, Congress established the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, now called the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), to develop practice guidelines, among other tasks. Produced by panels of experts, practice guidelines make specific recommendations to physicians on how to treat clinical conditions such as diabetes, osteoporosis, urinary incontinence, or cataracts. However, some powerful physician interests, displeased by AHRQ practice guidelines that recommended against surgical treatment for most cases of back pain, pressured Congress to reduce AHRQ’s budget and bar AHRQ from issuing its own guidelines.

More than 2000 guidelines exist; written by dozens of organizations, they vary in scientific reliability. Most are developed by societies of medical specialists (Steinbrook, 2007). Ideally, practice guidelines are based on a rigorous and objective review of scientific evidence, with explicit ratings of the quality of the evidence. However, 87% of clinical practice guideline authors in one survey had ties to the pharmaceutical industry, a bias often not disclosed to readers of the guidelines (Shaneyfelt and Centor, 2009). For example, eight of nine authors of widely used guidelines recommending broad use of cholesterol-lowering statin drugs had financial ties to companies making or selling statins (Abramson and Starfield, 2005). Moreover, clinical practice guidelines developed based on research on a narrowly defined population, such as nonelderly patients with a single chronic condition, may not be applicable to different patient populations, such as elderly patients with multiple diseases (Boyd et al, 2005).

Practice guidelines are not appropriate for many clinical situations. Uncertainty pervades clinical medicine, and practice guidelines are applicable only for those cases in which we enjoy “islands of knowledge in our seas of ignorance.” Practice guidelines can assist but not replace clinical judgment in the quest for high-quality care.

Pedro Urrutia, age 59, noticed mild nocturia and urinary frequency. His friend had prostate cancer, and he became concerned. The urologist said that his prostate was only slightly enlarged, his prostate-specific antigen (blood test) was normal, and surgery was not needed. Mr. Urrutia wanted surgery and found another urologist to do it.

At age 82, James Chin noted nocturia and urinary hesitancy. He had two glasses of wine on his wife’s birthday and later that night was unable to urinate. He went to the emergency department, was found to have a large prostate without nodules, and was catheterized. The urologist strongly recommended a transurethral resection of the prostate. Mr. Chin refused, thinking that the urinary retention was caused by the alcohol. Five years later, he was in good health with his prostate intact.

The difficulty with creating a set of indications for surgery, for example surgery for benign enlargement of the prostate gland, is that patient preferences vary markedly. Some, like Mr. Urrutia, want prostate surgery, even though it is not clearly needed; others, like Mr. Chin, have strong reasons for surgery but do not want it. Practice guidelines must take into account not only scientific data, but also patient preferences (O’Connor et al, 2007).

Do practice guidelines in themselves improve quality of care? Studies reveal that by themselves they are unsuccessful in influencing physicians’ practices (Cabana et al, 1999). However, guidelines can be an important foundation for more comprehensive quality improvement strategies, such as computer systems to remind physicians when patients are in need of certain services according to a guideline (eg, a reminder system about women due for a mammogram) or having trusted colleagues (“opinion leaders”) or visiting experts (“academic detailing”) conduct small group sessions with clinicians to review and reinforce practice guidelines (Bodenheimer and Grumbach, 2007).

One of the central tenets of the CQI approach is the need to systematically monitor how well individual caregivers, institutions, and organizations are performing. There are two basic types of indicators that are used to evaluate clinical performance: process measures and outcome measures. Process of care refers to the types of services delivered by caregivers. Examples are prescribing aspirin to patients with coronary heart disease, or turning immobile patients in hospital beds on a regular schedule to prevent bed sores. Outcomes are death, symptoms, mental health, physical functioning, and related aspects of health status, and are the gold standard for measuring quality. However, outcomes (particularly those dealing with quality of life) may be difficult to measure. More easily counted outcomes such as mortality may be rare events, and therefore uninformative for evaluating quality of care for many conditions that are not immediately life-threatening. Also, outcomes may be heavily influenced by the underlying severity of illness and related patient characteristics, and not just by the quality of health care that patients received (King and Wheeler, 2007) When measuring patient outcomes, it is necessary to “risk adjust” these outcome measurements for differences in the underlying characteristics of different groups of patients. Because of these challenges in using outcomes as measures to monitor quality of care, process measures tend to be more commonly used. For process measures to be valid indicators of quality, there must first be solid research demonstrating that the processes do in fact influence patient outcomes.

Dr. Susan Cutter felt horrible. It was supposed to have been a routine hysterectomy. Somehow she had inadvertently lacerated the large intestine of the patient, a 45-year-old woman with symptomatic fibroids of the uterus but otherwise in good health prior to surgery. Bacteria from the intestine had leaked into the abdomen, and after a protracted battle in the ICU the patient died of septic shock.

Dr. Cutter met with the Chief of Surgery at her hospital. The Chief reviewed the case with Dr. Cutter, but also pulled out a report showing the statistics on all of Dr. Cutter’s surgical cases over the previous 5 years. The report showed that Dr. Cutter’s mortality and complication rates were among the lowest of surgeons on the hospital’s staff. However, the Chief did note that another surgeon, Dr. Dehisce, had a complication rate that was much higher than that of all the other staff surgeons. The Chief of Surgery asked Dr. Cutter to serve on a departmental committee to review Dr. Dehisce’s cases and to meet with Dr. Dehisce to consider ways to address his poor performance.

The contemporary approach to quality monitoring moves beyond examining a few isolated cases toward measuring processes or outcomes for a large population of patients. For example, a traditional peer review approach is to review every case of a patient who dies during surgery. Reviewing an individual case may help a surgeon and the operating team understand where errors may have occurred—a process known as “root cause” analysis. However, it does not indicate whether the case represented an aberrant bad outcome for a surgeon or team that usually has good surgical outcomes, or whether the case is indicative of more widespread problems. To answer these questions requires examining data on all the patients operated on by the surgeon and the operating team to measure the overall rate of surgical complications, and having some benchmark data that indicate whether this rate is higher than expected for similar types of patients.

Mel Litus was the nurse in charge of diabetes education for a large medical group. After seeing yet another patient return to clinic after having had a foot amputation or suffering a heart attack, Mel wondered how the clinic team could do a better job in preventing diabetic complications. The medical group had recently implemented a new computerized clinical information system. Mel met with the administrator in charge of the computer system and arranged to have a printout made of all the laboratory findings, referrals, and medications for the diabetic patients in the medical group. When Mel reviewed the printout, he noticed that many of the patients didn’t attend appointments very regularly and were not receiving important services like regular ophthalmology visits and medications that protect the kidneys from diabetic damage. Mel met with the medical director for quality improvement to discuss a plan for sharing this information with the clinical staff and creating a system for more closely monitoring the care of diabetic patients.

Many practice organizations, from small groups of office-based physicians to huge, vertically integrated HMOs are starting to monitor patterns of care and provide feedback on this care to physicians and other staff in these organizations. The goal of this feedback is to alert caregivers and health care organizations about patterns of care that are not achieving optimal standards, in order to stimulate efforts to improve processes of care. The response may range from individual clinicians systematically reviewing their care of certain types of patients and clinical conditions, to entire organizations redesigning the system of care. A typical example of this practice profiling is measuring the rate at which diabetic patients receive recommended services, such as annual eye examinations, periodic testing of HbA1c levels, and evaluation of kidney function. Process of care profiles alert individual caregivers to specific diabetic patients who need to be called in for certain tests, and point out patterns of care that suggest that the organization should implement systematic reforms, such as developing case management programs for diabetic patients in poor control (Bodenheimer and Grumbach, 2007).

Maximizing excellence for individual health care professionals is only one ingredient in the recipe for high-quality health care. Improving institutions is the other, through CQI techniques. CQI involves the identification of concrete problems and the formation of interdisciplinary teams to gather data and propose and implement solutions to the problems.

In LDS Hospital in Salt Lake City, variation in wound infection rates by different physicians was related to the timing of the administration of prophylactic antibiotics. Patients who received antibiotics 2 hours before surgery had the lowest infection rates. The surgery department adopted a policy that all patients receive antibiotics precisely 2 hours before surgery; the rate of postoperative wound infections dropped from 1.8% to 0.9%. (Burke, 2001)

Such successes only dot, but do not yet dominate, the health care quality landscape (Solberg, 2007). The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) has led efforts to spread CQI efforts by sponsoring “collaboratives” to assist institutions and groups of institutions to improve health care outcomes and access while ideally reducing costs. Hundreds of health care organizations have participated in collaboratives concerned with such topics as improving the care of chronic illness, reducing waiting times, improving care at the end of life, and reducing adverse drug events. Collaboratives involve learning sessions during which teams from various institutions meet and discuss the application of a rapid change methodology within institutions. Some of IHI’s successes have taken place in the area of chronic disease, with a variety of institutions—from large integrated delivery systems to tiny rural community health centers—implementing the chronic care model to improve outcomes for conditions such as diabetes, asthma, and congestive heart failure (Bodenheimer et al, 2002). Collaboratives that assist institutions to implement the chronic care model have shown modest improvement in patient outcomes compared with controls (Vargas et al, 2007). In the area of patient safety, in 2004, IHI launched the 100,000 Lives Campaign (www.ihi.org) to reduce mortality rates in hospitals, followed by a 5 Million Lives Campaign between 2006 and 2008; more than 4000 hospitals in the United States participated in these campaigns. There is evidence that these campaigns have contributed to reductions in hospital mortality, although there is debate about the magnitude of the impact (Berwick et al, 2006; Wachter and Pronovost, 2006).

The advent of computerized information systems has created opportunities to improve care and to monitor the process and outcomes of care for entire populations. Electronic medical records can create lists of patients who are overdue for services needed for preventive care or the management of chronic illness and can generate reminder prompts for physicians and patients (Baron, 2007). In-hospital medical errors related to drug prescribing are reduced with computerized physician order entry (CPOE), systems requiring physicians to enter hospital orders directly into a computer rather than handwriting them. The computer can alert the physician about inappropriate medication doses or medications to which the patient is known to be allergic (Kaushal et al, 2003). However, hospital-based electronic health records have not yet been proven to significantly improve quality (Eslami et al, 2007; DesRoches et al, 2010). By themselves, computerized information systems are unlikely to improve quality; computerization must be accompanied by changes in the organization of informational processes (Bodenheimer and Grumbach, 2007).

The CQI approach emphasizes systematic monitoring of care to provide internal feedback to clinicians and health organizations to spur improved processes of care. A different approach to monitoring quality of care is to direct this information to the public. This approach views public release of systematic measurements of quality of care—commonly referred to as health care “report cards”—as a tool to empower health care consumers to select higher-quality caregivers and institutions. Advocates of this approach argue that armed with this information, patients and health care purchasers will make more informed decisions and preferentially seek out health care organizations with better report card grades.

An important experiment in individual physician report cards was initiated by the New York State Department of Health in 1990. The department released data on risk-adjusted mortality rates for coronary bypass surgery performed at each hospital in the state, and in 1992, mortality rates were also published for each cardiac surgeon. Each year’s list was big news and highly controversial. However, difficulties in measurement were highlighted by the fact that within 1 year, 46% of the surgeons had moved from one-half of the ranked list to the other half.

Several fascinating results came of this project: (1) Patients did not switch from hospitals with high mortality rates to those with lower mortality rates. (2) With the release of each report, one in five bottom quartile surgeons relocated or ceased practicing within two years. (3) In 4 years, overall risk-adjusted coronary artery bypass mortality dropped by 41% in New York State. Mortality for this operation also dropped in states without report cards, but not as much. (4) Some surgeons, worried about the report cards, may have elected not to operate on the most risky patients in order to improve their report card ranking. It is possible that the reduction in surgical mortality in part resulted from withholding surgery for the sickest patients. The New York State experiment had less effect on changing the market decisions of patients and purchasers than on motivating quality improvements in hospitals that had poor surgical outcomes (Marshall et al, 2000; Jha and Epstein, 2006).

In 2011, the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) launched its Physician Compare website, which will report on quality-of-care measures for specific physicians by 2015 (www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor/provider-search.aspx).

The most important report card program is the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS). Developed by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), a private organization controlled by large HMOs and large employers, HEDIS for 2010 is a list of 71 performance indicators including the percentage of children immunized; the percentage of enrollees of certain ages who have received Pap smears, colorectal screening, mammograms, and glaucoma screening; the percentage of pregnant women who received prenatal care in the first trimester; the percentage of diabetic patients who received retinal examinations; and the percentage of smokers for whom physicians made efforts at smoking cessation; the appropriateness of treatment for asthma, bronchitis, osteoporosis, depression, and others. NCQA chiefly reports on the performance of health plans; some critics believe that reporting on physicians and hospitals would be more helpful. Another problem is that few employers use quality data when selecting health plans for their employees; cost is the driving factor in most employer decisions (Galvin and Delbanco, 2005).

Report cards are based on a philosophy that says “if you can’t count it, you can’t improve it.” Albert Einstein expressed an alternative philosophy that might illuminate the report card enterprise: “Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.” Increasingly, the focus on quality is switching to a focus on value, with value referring to quality divided by cost. Thus an increase in a quality measure associated with a growth in cost may not improve value, where improved quality with a stable or reduced cost increases value (Owens et al, 2011).

In 2003, the Medicare program initiated public reporting for hospitals, focusing on risk-adjusted quality of care for heart attacks, heart failure, and pneumonia. More recently, surgical care and other measures have been added. Reports on individual hospitals and an explanation of the program are available at www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. The program, the Hospital Quality Initiative, is voluntary but nonparticipating hospitals receive a reduction in their Medicare payments. One might say that the program is in essence no-pay for no-reporting. Hospital quality has improved for some measures that are reported (Chassin et al, 2010), but hospitals focus their quality activities on the specific measures prescribed by the program, at times to the detriment of other quality activities (Pham et al, 2006).

In 2007, Medicare began the Physician Quality Reporting System, under which physicians who report certain quality measures may receive a 2% increase in their Medicare fees. This is not a full-fledged pay for reporting program because the reports for individual physicians or physician practices are not made public (www.cms.hhs.gov/pqri/).

By 2003, a new concept—“pay for performance”—was gaining widespread acceptance in health care (Epstein et al, 2004). Pay for performance (P4P) goes one step beyond pay for reporting; physicians or hospitals receive more money if their quality measures exceed certain benchmarks or if the measures improve from year to year.

One of the largest P4P programs is the Integrated Healthcare Association (IHA) program in California. IHA, representing employers, health plans, health systems and physician groups, launched the program in 2002 with a set of uniform performance measures. In 2010, seven health plans and 221 physician organizations—involving 35,000 physicians and 10 million patients—participated in the IHA program (www.iha.org).

In 2010, the health plans paid physician organizations $49 million in performance-based bonuses. The physician organizations receive funds for demonstrating improved clinical care (eg, cancer screening, immunizations, and management of asthma, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease), patient satisfaction, and development of information technology. In 2009, IHI added cost containment measures including inpatient utilization, hospital readmissions, and generic drug prescribing. Physician organizations distribute a substantial amount of the money to individual physicians but keep a portion of the bonus for organizationwide quality-enhancing initiatives. Quality measures have improved modestly since the program began, between 5% and 12%, but patient satisfaction did not. A limitation of the program is that the bonuses are small (about 2% of physician group revenues) and practices must spend money to organize and report their data (Damberg et al, 2009). Moreover, health plans are becoming less enthusiastic about P4P as they are not seeing the return on investment hoped for (Integrated Healthcare Organization, 2009).

The IHA program is unique for two reasons: All major health plans collaborated in choosing the measures upon which performance bonuses are based, and most physicians in California belong to a large medical group or independent practice association (see Chapter 6). If only one health plan sets up a P4P program with physicians, there may not be enough patients from that health plan to accurately measure the physician’s quality; with all health plans participating, a substantial portion of a physician’s patient panel is included in the measures. If P4P targets individual physicians rather than larger physician organizations, the small numbers of patients may distort the results. The ability of the California experience to aggregate a large number of patients allows for more accurate performance evaluation.

A P4P program initiated by large employers rather than health plans is Bridges to Excellence. This program involves more than 80 employers, large national health plans, and 3000 physicians in about 15 states. Physicians receive bonus payments for implementing computerized office systems and for improving the care of patients with diabetes, asthma, chronic lung disease, heart disease, back pain, and high blood pressure. Physicians practicing high-quality medicine in these areas receive public recognition and may receive bonuses, with the employers financing the program counting on higher-quality translating into lower costs. Performance is measured only for patients who are employees of the employers participating in the program, a small number for many physicians (www.bridgestoexcellence.org).

In 2003, Medicare launched a P4P program for 268 hospitals, measuring certain quality indicators for heart attack, heart failure, pneumonia, coronary artery bypass surgery, and hip and knee replacements. High-performing hospitals receive bonuses and the lowest performers may be subject to penalties. Performance on ten measures for heart attack, heart failure, and pneumonia in the P4P hospitals improved more than in control hospitals (Lindenauer, 2007). Another study looked at more than 100,000 heart attack patients treated at P4P and control hospitals; between 2003 and 2006, quality measures for these patients improved equally at P4P and control hospitals (Glickman et al, 2007). From 2003 to 2008, quality scores for participating hospitals improved by 18% (CMS, 2010), which was a 2% to 4% greater improvement than in control hospitals (Mehrotra et al, 2009).

A P4P program described as “an initiative to improve the quality of primary care that is the boldest such proposal attempted anywhere in the world” was launched in the United Kingdom in 2004 (Roland, 2004). This program is described in Chapter 14.

Some authors urge caution, pointing out that P4P programs could encourage physicians and hospitals to avoid high-risk patients in order to keep their performance scores up (McMahon et al, 2007). Another difficulty is that many patients see a large number of physicians in a given year, making it impossible to determine which physician should receive a performance bonus (Pham et al, 2007). Moreover, P4P programs could increase disparities in quality by preferentially rewarding physicians and hospitals caring for higher-income patients and having greater resources available to invest in quality improvement, and penalizing those institutions and physicians attending to more vulnerable populations in resource-poor environments (Casalino et al, 2007).

The quest for quality care encompasses a search for a financial structure that does not reward over- or under-treatment and that separates physicians’ personal incomes from their clinical decisions. Balanced incentives (see Chapter 4), combining elements of capitation or salary and fee-for-service, may have the best chance of minimizing the payment–treatment nexus (Robinson, 1999), encouraging physicians to do more of what is truly beneficial for patients while not inducing inappropriate and harmful services. Completely financially neutral decision making will always be an ideal and not a reality.

During a coronary angiogram, emboli traveled to the brain of Ivan Romanov, resulting in a serious stroke, with loss of use of his left arm and leg. The angiogram was appropriate and performed without any technical errors. Mr. Romanov had suffered a medical injury (an injury caused by his medical treatment), but the event was not because of negligence.

During a dilation and curettage (D&C), Judy Morrison’s physician unknowingly perforated her uterus and lacerated her colon. Ms. Morrison reported severe pain but was sent home without further evaluation. She returned 1 hour later to the emergency department with persistent pain and internal bleeding. She required a two-stage surgical repair over the following 4 months. This medical injury was found by the legal system to be because of negligence.

A peculiar set of institutions called the malpractice liability system forms an important part of US health care (Sage and Kersh, 2006). The goals of the malpractice system are twofold: To financially compensate people who in the course of seeking medical care have suffered medical injuries and to prevent physicians and other health care personnel from negligently causing harm to their patients.

The existing malpractice system scores miserably on both counts. According to the Harvard Medical Practice Study, only 2% of patients who suffer adverse events caused by medical negligence file malpractice claims that would allow them to receive compensation, meaning that the malpractice system fails in its first goal. Moreover, the system does not deal with 98% of negligent acts performed by physicians, making it difficult to attain its second goal. More recent research has confirmed the findings of the Harvard study (Sage and Kersh, 2006).

On the other hand, as many as 40% of malpractice claims do not involve true medical errors (Studdert et al, 2006), with an even smaller proportion representing actual negligence. Nonetheless, one-quarter of these inappropriate claims result in the patient receiving monetary compensation. Overall, for every dollar in compensation received by patients in malpractice awards, legal costs and fees come to 54 cents (Studdert et al, 2006).

The malpractice system has serious negative side effects on medical practice (Localio et al, 1991).

1. The system assumes that punishment, which usually involves physicians paying large amounts of money to a malpractice insurer plus enduring the overwhelming stress of a malpractice jury trial, is a reasonable method for improving the quality of medical care. Berwick’s analysis of the Theory of Bad Apples suggests that fear of a lawsuit closes physicians’ minds to improvement and generates an “I didn’t do it” response. The entire atmosphere created by malpractice litigation clouds a clear analytic assessment of quality.

2. The system is wasteful, with a huge portion of malpractice insurance premiums spent on lawyers, court costs, and insurance overhead almost as costly as payments to patients (Mello et al, 2010). Many claims have no merit but create enormous waste and wreak an unnecessary stress upon physicians. Patients granted malpractice award payments sometimes experienced no negligent care, and patients subjected to negligent care often receive no malpractice payments (Brennan et al, 1996). Total costs of the malpractice system came to $55.6 billion in 2008, 2.4% of total national health spending (Mello et al, 2010).

3. The system is based on the assumption that trial by jury is the best method of determining whether there has been negligence, a highly questionable assumption.

4. People with lower incomes generally receive smaller awards (because wages lost from a medical injury are lower) and are therefore less attractive to lawyers, who are generally paid as a percentage of the award. Accordingly, low-income patients, who suffer more medical injury, are less likely than wealthier people to file malpractice claims (Burstin et al, 1993b).

In summary, the malpractice system is burdened with expensive, unfounded litigation that harasses physicians who have done nothing wrong, while failing to discipline or educate most physicians committing actual medical negligence and to compensate most true victims of negligence.

Mei Tagaloa underwent neurosurgery for compression of his spinal cord by a cervical disk. On awakening from the surgery, Mr. Tagaloa was unable to move his legs or arms at all. After 3 months of rehabilitation, he ended up as a wheelchair-bound paraplegic. He sued the neurosurgeon and his family physician. The physicians’ malpractice insurer paid for lawyers to defend them. Mr. Tagaloa’s lawyer used the system of contingency fees, whereby he would receive one-third of the settlement if Mr. Tagaloa won the case, but would receive nothing if Mr. Tagaloa lost.

After 18 months, the case went to trial; the physicians left their practices and sat in the courtroom for 3 weeks. Each physician spent many hours going over records and discussing the case with the lawyers. The family physician, who had nothing to do with the surgery, was so upset with the proceedings that he developed an ulcer. The jury found the family physician innocent and the neurosurgeon guilty of negligence. The family physician lost $8000 in income because of absence from his practice. The neurosurgeon’s malpractice insurer paid $900,000 to Mr. Tagaloa, who paid $300,000 to the lawyer.

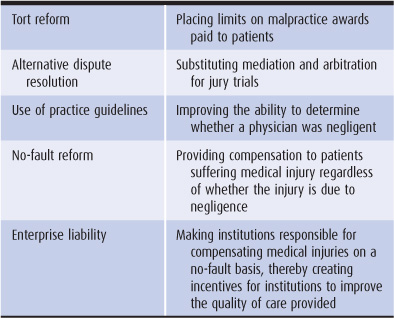

A number of proposals have been made for malpractice reform (Mello and Gallagher, 2010).

Medical malpractice fits into the larger legal field of torts (wrongful acts or injuries done willfully or negligently). The California Medical Injury Compensation Reform Act and the Indiana Medical Malpractice Act are examples of tort reform, placing caps on damages awarded to injured parties and limits on lawyers’ contingency fees. Tort reform can help physicians by slowing the growth of malpractice insurance premiums. However, caps on awards can be unfair to patients, limiting payments to those with the worst injuries (Mello et al, 2003; Localio, 2010) (Table 10–4).

Table 10–4. Malpractice reform options

These programs would substitute mediation, arbitration, or private negotiated settlements for jury trials in the case of medical injury. Alternatives to the jury trial could bring more compensation to injured parties by reducing legal costs and might shift the dispute settlement to a more scientific, less emotional theater.

Proposals have been made to switch compensation for medical injury from the tort system to a no-fault plan (Studdert and Brennan, 2001; Localio, 2010). Under no-fault malpractice, patients suffering medical injury would receive compensation whether or not the injury was caused by negligence. Without costly lawyers’ fees and jury trials, overhead costs would drop from more than 50% to approximately 20%. A no-fault system would compensate far more people and would cost approximately the same as the current tort system (Johnson et al, 1992). In addition, the no-fault approach might allow physicians to be more inclined to identify and openly discuss medical errors for the purpose of correcting them (Studdert et al, 2004).

A relatively new idea for malpractice reform is to make health care institutions—primarily hospitals and HMOs—responsible for compensating medical injuries (Studdert et al, 2004; Sage and Kersh, 2006; Chan, 2010). As with no-fault proposals, patients suffering medical injury would be compensated whether or not the injury is negligent. Enterprise liability improves upon the no-fault concept by making institutions pay higher insurance premiums if they are the site of more medical injuries (whether caused by system failure or physician error). Hospitals and HMOs would have a financial incentive to improve the quality of care.

Each year people in the United States make more than 1 billion visits to physicians’ offices and spend more than 100 million days in acute care hospitals. While quality of care provided during most of these encounters is excellent, the goal of the health care system should be to deliver high-quality care every day to every patient. This goal presents an unending challenge to each health caregiver and health care institution. Physicians make hundreds of decisions each day, including which questions to ask in the patient history, which parts of the body to examine in the physical examination, which laboratory tests and x-rays to order and how urgently, which diagnoses to entertain, which treatments to offer, when to have the patient return for follow-up, and whether other physicians need to be consulted. Nurse practitioners, physician assistants, nurses, and other caregivers face similar numbers of decisions. It is humanly impossible to make all of these decisions correctly every day. For health care to be of high quality, mistakes should be minimized, mistakes with serious consequences should be avoided, and systems should be in place that reduce, detect, and correct errors to the greatest extent possible. Even when all decisions are technically accurate, if caregivers are insensitive or fail to provide the patient with a full range of informed choices, quality is impaired.

For the clinician, each decision that influences quality of care may be simple, but the sum total of all decisions of all caregivers impacting on a patient’s illness makes the achievement of high-quality care elusive. To safeguard quality of care, our nation needs laws and regulations, including standards for health care professional education, rules for licensure, boards with the authority to discipline clear violators, and measurement to inform institutions, practitioners, and patients about the quality of their care. Improvement of health care quality cannot solely rely on regulators in Washington, DC, in state capitals, or across town; it must come from within each institution, whether a huge academic center, a community hospital, or a small medical office.

Abramson J, Starfield B. The effect of conflict of interest on biomedical research and clinical practice guidelines. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:414.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National Healthcare Disparities Report, 2009. www.ahrq.gov. Accessed August 22, 2011.

Ash JS et al. The extent and importance of unintended consequences related to computerized provider order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14:415.

Ayanian JZ. Race, class, and the quality of medical care. JAMA. 1994;271:1207.

Baker AM et al. A web-based diabetes care management support system. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2001;27:179.

Baron RJ. Quality improvement with an electronic health record: Achievable but not automatic. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:549.

Berenson RA et al. Hospital—physician relations: Cooperation, competition, or separation? Health Aff Web Exclusive. December 5, 2006:w31.

Berwick DM. Continuous improvement as an ideal in health care. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:53.

Berwick DM et al. Curing Health Care. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1990.

Berwick DM et al. IHI replies to “The 100,000 Lives Campaign: A scientific and policy review.” Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32:628.

Birkmeyer JD et al. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2117.

Bodenheimer T et al. The primary care—specialty income gap: why it matters. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:301.

Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K. Improving Primary Care: Strategies and Tools for a Better Practice. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2007.

Bodenheimer T et al. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288:1775, 1909.

Boyd CM et al. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases. JAMA. 2005;294:716.

Brennan TA et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:370.

Brennan TA et al. Relation between negligent adverse events and the outcomes of medical-malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1963.

Buerhaus PI. Is hospital patient care becoming safer? A conversation with Lucian Leape. Health Aff Web Exclusive. October 9, 2007:w687.

Bunker J. Surgical manpower. N Engl J Med. 1970;282:135.

Burke JP. Maximizing appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis for surgical patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(suppl 2):S78.

Burstin HR et al. The effect of hospital financial characteristics on quality of care. JAMA. 1993a;270:845.

Burstin HR et al. Do the poor sue more? JAMA. 1993b;270:1697.

Cabana MD et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? JAMA. 1999;282:1458.

Casalino LP et al. Will pay-for-performance and quality reporting affect health care disparities? Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26:405.

Casalino LP et al. Frequency of failure to inform patients of clinically significant outpatient test results. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1123.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Hospital Premier Quality Incentive Demonstration Fact Sheet, December 2010. (www.cms.gov/HospitalQualityInits/35_ HospitalPremier.asp).

Chan TE. Organisational liability in a health care system. Torts Law Jl. 2010;18(3):228.

Chassin MR et al. The urgent need to improve health care quality. JAMA. 1998;280:1000.

Chassin MR et al. Accountability measures—using measurement to promote quality improvement. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:683.

Choudhry NK et al. Relationships between authors of clinical practice guidelines and the pharmaceutical industry. JAMA. 2002;287:612.

Damberg CL et al. Taking stock of pay-for-performance: A candid assessment from the front lines. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28:517.

DesRoches CM et al. Electronic health records’ limited successes suggest more targeted uses. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:639.

Deyo RA et al. Spinal fusion surgery—the case for restraint. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:722.

Dudley RA et al. Selective referral to high-volume hospitals: Estimating potentially avoidable deaths. JAMA. 2000; 283:1159.

Eddy DM. Three battles to watch in the 1990s. JAMA. 1993;270:520.

Egan BM et al. US trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, 1988–2008. JAMA. 2010; 303:2043.

Epstein AM et al. Paying physicians for high-quality care. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:406.

Eslami S et al. Evaluation of outpatient computerized physician medication order entry systems. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14:400.

Fiscella K et al. Inequality in quality. JAMA. 2000;283:2579.

Fisher ES et al. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1: The content, quality, and accessibility of care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:273.

Gallagher TH et al. US and Canadian physicians’ attitudes and experiences regarding disclosing errors to patients. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1605.

Galvin RS, Delbanco S. Why employers need to rethink how they buy health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24:1549.

Gandhi TK et al. Outpatient prescribing errors and the impact of computerized prescribing. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:837.

Glickman SW et al. Pay for performance, quality of care, and outcomes in acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2007;297:2373.

Hillman BJ et al. Frequency and costs of diagnostic imaging in office patients: A comparison of self-referring and radiologist-referring physicians. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1604.

Hollingsworth JM et al. Physician-ownership of ambulatory surgery centers linked to higher volume of surgeries. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:683.

Institute of Medicine. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1999.

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

Integrated Healthcare Organization. The California Pay For Performance Program, June 2009. www.iha.org.

Jha AK, Epstein AM. The predictive accuracy of the New York State coronary artery bypass surgery report-card system. Health Aff (Millwood). 2006;25:844.

Johnson WG et al. The economic consequences of medical injuries: Implications for a no-fault insurance plan. N Engl J Med. 1992;267:2487.

Kaiser Family Foundation. Annual Employer Health Benefits Survey Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2003.

Kaushal R et al. Effects of computerized physician order entry and clinical decision support systems on medication safety. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1409.

King TE, Wheeler MB. Medical Management of Vulnerable and Underserved Patients. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2007.

Kizer K. The volume-outcome conundrum. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2159.

Laffel GL, Berwick DM. Quality health care. JAMA. 1993;270:254.

Leape LL et al. The nature of adverse events in hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:377.

Leape LL. Unnecessary surgery. Annu Rev Public Health. 1992;13:363.

Leape LL. Error in medicine. JAMA. 1994;272:1851.

Leape LL, Fromson JA. Problem doctors: Is there a system-level solution? Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:107.

Lindenauer PK et al. Public reporting and pay for performance in hospital quality improvement. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:486.

Localio AR et al. Relation between malpractice claims and adverse events due to negligence. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:245.

Localio AR. Patient compensation without litigation: A promising development. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:266.

Marshall MN, et al. The public release of performance data. JAMA. 2000;283:1866.

McGlynn EA et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2635.

McMahon LF et al. Physician-level P4P—DOA? Am J Manag Care. 2007;13:233.

Mehrotra A et al. Pay for performance in the hospital setting: What is the state of the evidence? Am J Med Qual. 2009;24:19.

Mello MM et al. The new medical malpractice crisis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2281.

Mello MM et al. National costs of the medical liability system. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:1569.

Mello MM, Gallagher TH. Malpractive reform—opportunities for leadership by health care institutions and liability insurers. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1353.

Meurer LN et al. Excess mortality caused by medical injury. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4:410.

Mitchell JM, Scott E. New evidence of the prevalence and scope of physician joint ventures. JAMA. 1992;268:80.

Morrison J, Wickersham P. Physicians disciplined by a state medical board. JAMA. 1998;279:1889.

National Committee for Quality Assurance. The State of Health Care Quality, 2009. NCQA, 2010. www.ncqa.org.

O’Connor AM et al. Toward the “tipping point”: Decision aids and informed patient choice. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26:716.

Owens DK et al. High-value, cost-conscious health care. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:174.

Peterson ED et al. Procedural volume as a marker of quality for CABG surgery. JAMA. 2004;291:195.

Pham HH et al. The impact of quality-reporting programs on hospital operations. Health Aff (Millwood). 2006;25:1412.

Pham HH et al. Care patterns in Medicare and their implications for pay for performance. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1130.

Phillips DP et al. Increase in US medication-error deaths between 1983 and 1993. Lancet. 1998;351:643.

Relman AS. A Second Opinion: Rescuing America’s Health Care. New York: Public Affairs; 2007.

Robinson JC. Blended payment methods in physician organizations under managed care. JAMA. 1999;282:1258.

Roland M. Linking physicians’ pay to the quality of care—a major experiment in the United Kingdom. N Engl J Med. 2004;351: 1448.

Rouf E et al. Computers in the exam room. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:43.

Sage WM, Kersh R. Medical Malpractice and the US Health Care System. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

Saydah SH et al. Poor control of risk factors for vascular disease among adults with previously diagnosed diabetes. JAMA. 2004;291:335.

Schoen C et al. US health system performance: A national scorecard. Health Aff Web Exclusive. September 20, 2006:w457.

Schuster MA et al. How good is the quality of health care in the United States? Milbank Q. 1998;76:517.

Shaneyfelt TM, Centor RM. Reassessment of clinical practice guidelines. JAMA. 2009;301:868.

Smith-Bindman R. Is computed tomography safe? N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1.

Solberg LI. Improving medical practice: A conceptual framework. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:251.

Steinbrook R. Guidance for guidelines. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:331.

Studdert DM, Brennan TA. No-fault compensation for medical injuries. JAMA. 2001;286:217.

Studdert DM et al. Medical malpractice. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:283.

Studdert DM et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2024.

US Senate. Hearings Before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Committee on Government Operations, March 13 and 14, 1975. Prepaid Health Plans. US Government Printing Office; 1975.

Vargas RB et al. Can a chronic care model collaborative reduce heart disease risk in patients with diabetes? J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:215.

Wachter RM. Why diagnostic errors don’t get any respect—and what can be done about them. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:1605.

Wachter RM, Pronovost PJ. The 100,000 Lives Campaign: A scientific and policy review. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32:621.

Weeks WB et al. Higher health care quality and bigger savings found at large multispecialty medical groups. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;29:991.

Zahn C, Miller MR. Excess length of stay, charges, and mortality attributable to medical injuries during hospitalization. JAMA. 2003;290:1868.