The financing and organization of medical care throughout the developed world spans a broad spectrum. In most countries, the preponderance of medical care is financed or delivered (or both) in the public sector; in others, like the United States, most people both pay for and receive their care through private institutions.

In this chapter, we describe the health care systems of four nations: Germany, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Japan. Each of these nations resides at a different point on the international health care continuum. Examining their diverse systems may aid us in our search for a suitable health care system for the United States.

Recall from Chapter 2 the four varieties of health care financing: out-of-pocket payments, individual private insurance, employment-based private insurance, and government financing. Germany, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Japan emphasize the last two modes of payment. Germany finances medical care through government-mandated, employment-based private insurance, though German private insurance is a world apart from that found in the United States. Canada and the United Kingdom feature government-financed systems. Japan’s financing falls between the German method of financing and the government model of Canada and the United Kingdom. Regarding the delivery of medical care, the German, Japanese, and Canadian systems are predominantly private, while the United Kingdom’s is largely public.

Although these four nations demonstrate great differences in their manner of financing and organizing medical care, in one respect they are identical: They all provide universal health care coverage, thereby guaranteeing to their populations financial access to medical services.

Hans Deutsch is a bank teller living in Germany. He and his family receive health insurance through a sickness fund that insures other employees and their families at his bank and at other workplaces in his city. When Hans went to work at the bank, he was required by law to join the sickness fund selected by his employer. The bank contributes 7.3% of Hans’s salary to the sickness fund, and 8.2% is withheld from Hans’s paycheck and sent to the fund. Hans’s sickness fund collects the same 15.5% employer-employee contribution for all its members.

Germany was the first nation to enact compulsory health insurance legislation. Its pioneering law of 1883 required certain employers and employees to make payments to existing voluntary sickness funds, which would pay for the covered employees’ medical care. Initially, only industrial wage earners with incomes less than $500 per year were included; the eligible population was extended in later years.

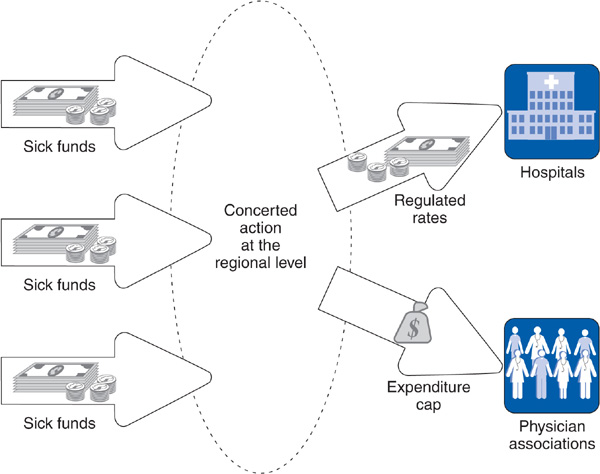

Almost 90% of Germans now receive their health insurance through the mandatory sickness funds, with 10% covered by voluntary insurance plans (Figure 14–1). Several categories of sickness funds exist. Thirty-seven percent of people (mostly blue-collar workers and their families) belong to funds organized by geographic area; 33% (for the most part the families of white-collar workers) are in nationally based “substitute” funds; 21% are employees or dependents of employees who work in 700 companies that have their own sickness funds; and 6% are in funds covering all workers in a particular craft (Busse and Riesberg, 2004; Busse, 2008).

Figure 14–1. The German national health insurance system.

In 2010, the proportion of earnings going to a sickness fund was set at 15.5%, with employers paying 47% and employees 53% of that amount. These contributions formerly went directly to the sickness funds, which are nonprofit, closely regulated entities that lie somewhere between the private and public sectors. Since 2009, employee and employer contributions are collected by a government-run health fund, which then distributes the money to health funds based on a risk-adjusted (more for older and sicker people) amount per insured person (Ornyanova and Busse, 2009). The number of sickness funds is shrinking, down from 1000 to less than 200 in 2011. The funds are not allowed to exclude people because of illness, or to raise contribution rates according to age or medical condition; that is, they may not use experience rating. The funds are required to cover a broad range of benefits, including hospital and physician services, prescription drugs, and dental, preventive, and maternity care. Because wages supporting health care financing are declining relative to health care costs, employers are proposing that their contribution be capped at 7% of earnings so that further increases are borne by employees (Zander et al, 2009).

Hans’s father, Peter Deutsch, is retired from his job as a machinist in a steel plant. When he worked, his family received health insurance through a sickness fund set up for employees of the steel company. The fund was run by a board, half of whose members represented employees and the other half the employer. On retirement, Peter’s family continued its coverage through the same sickness fund with no change in benefits. The sickness fund continues to pay approximately 60% of his family’s health care costs (subsidized by the contributions of active workers and the employer), with 40% paid from Peter’s retirement pension fund.

Hans has a cousin, Georg, who formerly worked for a gas station in Hans’s city, but is now unemployed. Georg remained in his sickness fund after losing his job. His contribution to the fund is paid by the government. Hans’s best friend at the bank was diagnosed with lymphoma and became permanently disabled and unable to work. He remained in the sickness fund, with his contribution paid by the government.

Upon retiring from or losing a job, people and their families retain membership in their sickness funds. Health insurance in Germany, as in the United States, is employment based, but German health insurance, unlike in the United States, must continue to cover its members whether or not they change jobs or stop working for any reason.

Hans’s Uncle Karl is an assistant vice-president at the bank. Because he earns more than 49,500 Euros per year, he is not required to join a sickness fund, but can opt to purchase private health insurance. Many higher-paid employees choose a sickness fund; they are not required to join the fund selected by the employer for lower-paid workers but can join one of 15 national “substitute” funds.

Ten percent of Germans, with incomes more than 49,500 Euros per year (2011), choose voluntary private insurance. Private insurers pay higher fees to physicians than do sickness funds, often allowing their policyholders to receive preferential treatment. In summary, in Germany 88% of the populace belong to the mandatory sickness fund system, 10% opt for private insurance, 2% receive medical services as members of the armed forces or police, and less than 0.2% (all of whom are wealthy) have no coverage.

Germany finances health care through a merged social insurance and public assistance structure (see Chapters 2, 12, and 15 for discussion of these concepts), such that no distinctions are made between employed people who contribute to their health insurance, and unemployed people, whose contribution is made by the government.

Hans Deutsch develops chest pain while walking, and it worries him. He does not have a physician, and a friend recommends a general practitioner (GP), Dr. Helmut Arzt. Because Hans is free to see any ambulatory care physician he chooses, he indeed visits Dr. Arzt, who diagnoses angina pectoris—coronary artery disease. Dr. Arzt prescribes some medications and a low-fat diet, but the pain persists. One morning, Hans awakens with severe, suffocating chest pain. He calls Dr. Arzt, who orders an ambulance to take Hans to a nearby hospital. Hans is admitted for a heart attack and is cared for by Dr. Edgar Hertz, a cardiologist. Dr. Arzt does not visit Hans in the hospital. Upon discharge, Dr. Hertz sends a report to Dr. Arzt, who then resumes Hans’s medical care. Hans never receives a bill.

German medicine maintains a strict separation of ambulatory care physicians and hospital-based physicians. Most ambulatory care physicians are prohibited from treating patients in hospitals, and most hospital-based physicians do not have private offices for treating outpatients. People often have their own primary care physician (PCP) but are allowed to make appointments to see ambulatory care specialists without referral from the primary care physician. Fifty-one percent of Germany’s physicians are generalists, compared with only 35% in the United States. The German system tends to use a dispersed model of medical care organization (see Chapter 5), with little coordination between ambulatory care physicians and hospitals (Busse and Riesberg, 2004).

Dr. Arzt was used to billing his regional association of physicians and receiving a fee for each patient visit and for each procedure done during the visit. In 1986, he was shocked to find that spending caps had been placed on the total ambulatory physician budget. If in the first quarter of the year, the physicians in his regional association billed for more patient services than expected, each fee would be proportionately reduced during the next quarter. If the volume of services continued to increase, fees would drop again in the third and fourth quarters of the year. Dr. Arzt discussed the situation with his friend Dr. Hertz, but Dr. Hertz, as a hospital physician, received a salary and was not affected by the spending cap.

Ambulatory care physicians are required to join their regional physicians’ association. Rather than paying physicians directly, sickness funds pay a global sum each year to the physicians’ association in their region, which in turn pays physicians on the basis of a detailed fee schedule. These sums have been based on the number of patients cared for by the physicians in each regional association, but in 2007, a risk-adjustment factor is being introduced that increases payments for populations with greater health problems. Since 1986, physicians’ associations, in an attempt to stay within their global budgets, have reduced fees on a quarterly basis if the volume of services delivered by their physicians was too high. Sickness funds pay hospitals on a basis similar to the diagnosis-related groups used in the US Medicare program. Included within this payment is the salary of hospital-based physicians (Busse and Riesberg, 2004).

The 1977 German Cost Containment Act created a body called Concerted Action, made up of representatives of the nation’s health providers, sickness funds, employers, unions, and different levels of government. Concerted Action is convened twice each year, and every spring, it sets guidelines for physician fees, hospital rates, and the prices of pharmaceuticals and other supplies. Based on these guidelines, negotiations are conducted at state, regional, and local levels between the sickness funds in a region, the regional physicians’ association, and the hospitals to set physician fees and hospital rates that reflect Concerted Action guidelines. Since 1986, not only have physician fees been controlled, but as described in the above vignette about Dr. Arzt, the total amount of money flowing to physicians has been capped. As a result of these efforts, Germany’s health expenditures as a percentage of the gross domestic product actually fell between 1985 and 1991 from 8.7% to 8.5%.

In 1991, however, German health care costs resumed an upward surge, paving the way for a 1993 cost control law restricting the growth of sickness fund budgets. In 2004, Germany raised copayments, ceased coverage of over-the-counter drugs, and enacted new controls on pharmaceutical prices (Stock et al, 2006). While Germany’s 2008 health care expenditures as a percent of GDP was the fifth highest among developed nations, this figure has remained stable since 2000, indicating that cost control measures limiting the size of sickness fund budgets are having success.

The Maple family owns a small grocery store in Outer Snowshoe, a tiny Canadian town. Grandfather Maple has a heart condition for which he sees Dr. Rebecca North, his family physician, regularly. The rest of the family is healthy and goes to Dr. North for minor problems and preventive care, including children’s immunizations. Neither as employers nor as health consumers do the Maples worry about health insurance. They receive a plastic card from their provincial government and show the card when they visit Dr. North.

The Maples do worry about taxes. The federal personal income tax, the goods and services tax, and the various provincial taxes take almost 40% of the family’s income. But the Maples would never let anyone take away their health insurance system.

In 1947, the province of Saskatchewan initiated the first publicly financed universal hospital insurance program in North America. Other provinces followed suit, and in 1957, the Canadian government passed the Hospital Insurance Act, which was fully implemented by 1961. Hospital, but not physician, services were covered. In 1963, Saskatchewan again took the lead and enacted a medical insurance plan for physician services. The Canadian federal government passed universal medical insurance in 1966; the program was fully operational by 1971 (Taylor, 1990).

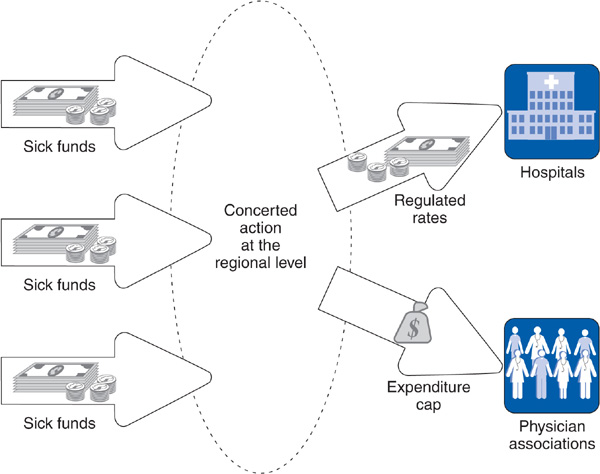

Canada has a tax-financed, public, single-payer health care system. In each Canadian province, the single payer is the provincial government (Figure 14–2). During the 1970s, federal taxes financed 50% of health services, but the federal share declined to 22% by 1996, generating acrimony between the federal and provincial governments. In response to this political debate, the federal contributions began to increase in 2001. Currently, the federal government funds approximately one-third of provincial health expenditures (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2010). Provincial taxes vary in type from province to province and include income taxes, payroll taxes, and sales taxes. Some provinces, for example British Columbia and Alberta, charge a compulsory health care premium—essentially an earmarked tax—to finance a portion of their health budgets.

Figure 14–2. The Canadian national health insurance system.

Unlike Germany, Canada has severed the link between employment and health insurance. Wealthy or poor, employed or jobless, retired or younger than 18, every Canadian receives the same health insurance, financed in the same way. No Canadian would even imagine that leaving, changing, retiring from, or losing a job has anything to do with health insurance. In Canada, no distinction is made between the two public financing mechanisms of social insurance (in which only those who contribute receive benefits) and public assistance (in which people receive benefits based on need rather than on having contributed). Everyone contributes through the tax structure and everyone receives benefits.

The benefits provided by Canadian provinces are broad, including hospital, physician, and ancillary services. Provincial plans also pay for outpatient drugs, although the scope of drug coverage—and also long-term care benefits—varies across provinces.

The Canadian health care system is unique in its prohibition of private health insurance for coverage of services included in the provincial health plans. Hospitals and physicians that receive payments from the provincial health plans are not allowed to bill private insurers for such services, thereby avoiding the preferential treatment of privately insured patients that occurs in many health care systems. Canadians can purchase private health insurance policies for gaps in provincial health plan coverage or for such amenities as private hospital rooms.

Grandfather Maple has had intermittent sensations of palpitations in his chest for a few weeks. He calls Dr. North, who tells him to come right over. An electrocardiogram reveals rapid atrial fibrillation, an abnormal heart rhythm. Because Mr. Maple is tolerating the rapid rhythm, Dr. North starts treatment with metoprolol in the office to gradually slow his heart rate, tells him to return the next day, and writes out a referral slip to see Dr. Jonathan Hartwell, a cardiologist in a nearby small city.

Dr. Hartwell arranges a stress echocardiogram at the local hospital to evaluate Mr. Maple’s arrhythmia, finds severe coronary ischemia, and explains to Mr. Maple that his coronary arteries are narrowed. He recommends a coronary angiogram and possible coronary artery bypass surgery. Because Mr. Maple’s condition is not urgent, Dr. Hartwell arranges for his patient to be placed on the waiting list at the University Hospital in the provincial capital 50 miles away. One month later, Mr. Maple awakens at 2 AM in a cold sweat, gasping for breath. His daughter calls Dr. North, who urgently sends for an ambulance to transport Mr. Maple to the University Hospital. There Mr. Maple is admitted to the coronary care unit, his condition is stabilized, and he undergoes emergency coronary artery bypass surgery the next day. Ten days later, Mr. Maple returns home, complaining of pain in his incision but otherwise feeling well.

Approximately half of Canadian physicians are family physicians (contrasted with the United States, where only 35% of physicians are generalists). Canadians have free choice of physician. As a rule, Canadians see their family physician for routine medical problems and visit specialists only through referral by the family physician. Specialists are allowed to see patients without referrals, but only receive the higher specialist fee if they specify the referring primary care physician in their billing; for that reason, most specialists will not see patients without a referral. Unlike the European model of separation between ambulatory and hospital physicians, Canadian family physicians are allowed to care for their patients in hospitals. Because of the close scientific interchange between Canada and the United States, the practice of Canadian medicine is similar to that in the United States; the differences lie in the financing system and the far greater use of primary care physicians. The treatment of Mr. Maple’s heart condition is not significantly different from what would occur in the United States, with the exception that high-tech procedures such as cardiac surgery and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans are regionalized in a limited number of facilities and performed far less frequently than in the United States. In 2007, Canada had 6.7 MRI scanners per million inhabitants compared with 25.9 in the United States (OECD, 2010).

Canadians on average wait longer for elective operations than do insured people in the United States and also have slightly more difficulty accessing primary care physicians (Schoen et al, 2010). Over the past ten years the federal and provincial governments have implemented successful policies to reduce elective surgery delays (Ross and Detsky, 2009). The median 2005 wait time for nonemergency surgery in Canada was 4 weeks (Willcox et al, 2007). Despite queues for elective procedures, only a tiny number of Canadians cross the border to seek care in the United States (Katz et al, 2002).

Canada’s universal insurance program has created a fairer system for distributing health services. Canadians are much less likely than their counterparts in the United States to report experiencing financial barriers to medical care (Schoen et al, 2010). Low-income Canadians receive almost the same amount of medical services as Canadians from higher-income groups, whereas in the United States higher-income groups receive more health services than lower-income groups (Sanmartin et al, 2006). Nonetheless, inequities in care according to socioeconomic status remain in Canada despite universal insurance coverage (Guilfoyle, 2008).

For Dr. Rebecca North, collecting fees is a simple matter. Each week she electronically bills the provincial government, listing the patients she saw and the services she provided. Within a month, she is paid in full according to a fee schedule. Dr. North wishes the fees were higher, but loves the simplicity of the billing process. Her staff spends 2 hours per week on billing, compared with the 30 hours of staff time her friend Dr. South in Michigan needs for billing purposes.

Dr. North is less happy about the global budget approach used to pay hospitals. She often begs the hospital administrator to hire more physical therapists, to speed up the reporting of laboratory results, and to institute a program of diabetic teaching. The administrator responds that he receives a fixed payment from the provincial government each year, and there is no extra money.

Most physicians in Canada—primary care physicians and specialists—are paid on a fee-for-service basis, with fee levels negotiated between provincial governments and provincial medical associations (Figure 14–2). Physicians participating in the provincial programs must accept the government rate as payment in full and cannot bill patients directly for additional payment. Because fee-for-service payment emphasizes volume over quality of care and makes cost control difficult (see Chapter 9), Canadian provinces are experimenting with alternative forms of payment such as salary or capitation for physicians in group practice and clinic settings. By 2009, many primary care physicians in the province of Ontario were being paid capitation with bonuses for high quality (Collier, 2009).

Canadian hospitals, most of which are private nonprofit institutions, negotiate a global budget with the provincial government each year. Hospitals have no need to prepare the itemized patient bills that are so administratively costly in the United States. Hospitals must receive approval from their provincial health plan for new capital projects such as the purchase of expensive new technology or the construction of new facilities. Canada also regulates pharmaceutical prices and provincial plans maintain formularies of drugs approved for coverage.

The Canadian system has attracted the interest of many people in the United States because in contrast to the United States, the Canadians have found a way to deliver comprehensive care to their entire population at far less cost. In 1970, the year before Canada’s single-payer system was fully in place, Canada and the United States spent approximately the same proportion of their gross domestic products on health care—7.2% and 7.4%, respectively. By 1990, Canada’s health expenditures had risen to 9% of the gross domestic product, compared with 12% for the United States. In 2008, Canada dedicated 10.4% of its gross domestic product to health care while the United States reached 16% (OECD, 2010). The differences in cost between the United States and Canada are primarily accounted for by four items: (1) administrative costs, which are more than 300% greater per capita in the United States; (2) more widespread use of expensive high-tech services in the United States; (3) cost per patient day in hospitals, which reflects a greater intensity of service in the United States; and (4) physician fees and pharmaceutical prices, which are much higher in the United States (Anderson et al, 2003; Woolhandler et al, 2003; Reinhardt, 2008).

While 2008 Canadian per capita health care costs ($4079) were far lower than those in the United States ($7538), Canada was the fifth highest on that measure among developed nations (OECD, 2010). Canadian concern with cost increases began in the 1990s, when Canadian provinces put into effect caps on physician payments similar to those used in Germany (Barer et al, 1996).

However, the Canadian federal government’s fiscal austerity policies of the 1990s appear to have shaken the public’s traditionally high level of confidence in the Canadian health care system. In 2010, about one-quarter of Canadians were not confident that they would receive the care they needed (Schoen et al, 2010). This unrest in public opinion has prompted vigorous debate in Canada about whether to allow greater private financing of health care, raise taxes to increase public financing, or restructure services to improve efficiency (Steinbrook, 2006). By 2010, Canada had opted for the latter two options: a commitment of substantial increases in federal funds for provincial health plans coupled with reform of the organization of primary care and other services (Hutchison et al, 2011).

Roderick Pound owns a small bicycle repair shop in the north of England; he lives with his wife and two children. His sister Jennifer is a lawyer in Scotland. Roderick’s younger brother is a student at Oxford, and their widowed mother, a retired sales-woman, lives in London. Their cousin Anne is totally and permanently disabled from a tragic automobile accident. A distant relative, who became a US citizen 15 years before, recently arrived to help care for Anne.

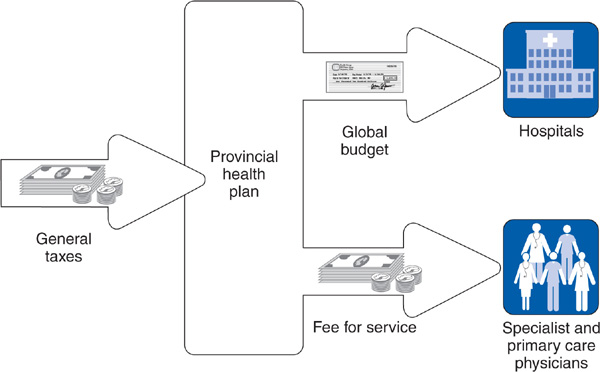

Simply by virtue of existing on the soil of the United Kingdom—whether employed, retired, disabled, or a foreign visitor—each of the Pound family members is entitled to receive tax-supported medical care through the National Health Service (NHS).

In 1911, Great Britain established a system of health insurance similar to that of Germany. Approximately half the population was covered, and the insurance arrangements were highly complex, with contributions flowing to “friendly societies,” trade union and employer funds, commercial insurers, and county insurance committees. In 1942, the world’s most renowned treatise on social insurance was published by Sir William Beveridge. The Beveridge Report proposed that Britain’s diverse and complex social insurance and public assistance programs, including retirement, disability and unemployment benefits, welfare payments, and medical care, be financed and administered in a simple and uniform system. One part of Beveridge’s vision was the creation of a national health service for the entire population. In 1948, the NHS began.

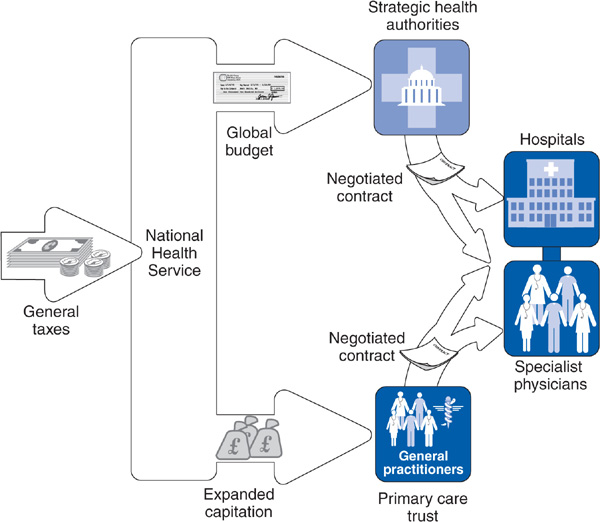

The great majority of NHS funding comes from taxes. As in Canada, the United Kingdom completely separates health insurance from employment, and no distinction exists between social insurance and public assistance financing. Unlike Canada, the United Kingdom allows private insurance companies to sell health insurance for services also covered by the NHS. A number of affluent people—12.5% of the population in 2007—purchase private insurance in order to receive preferential treatment, “hopping over” the queues for services present in parts of the NHS. Some employers offer such supplemental insurance as a perk. People with private insurance are also paying taxes to support the NHS (Figure 14–3).

Figure 14–3. The British National Health Service: traditional model.

Dr. Timothy Broadman is an English GP, whose list of patients numbers 1750. Included on his list is Roderick Pound and his family. One day, Roderick’s son broke his leg playing soccer. He was brought to the NHS district hospital by ambulance and treated by Dr. Pettibone, the hospital orthopedist, without ever seeing Dr. Broadman.

Roderick’s mother has severe degenerative arthritis of the hip, which Dr. Broadman cares for. A year ago, Dr. Broadman sent her to Dr. Pettibone to be evaluated for a hip replacement. Because this was not an emergency, Mrs. Pound required a referral from Dr. Broadman to see Dr. Pettibone. The orthopedist examined and x-rayed her hip and agreed that she needed a hip replacement, but not on an urgent basis. Mrs. Pound has been on the waiting list for her surgery for more than 6 months. Mrs. Pound has a wealthy friend with private health insurance who got her hip replacement within three weeks from Dr. Pettibone, who has a private practice in addition to his employment with the NHS.

Prior to the NHS, most primary medical care was delivered through GPs. The NHS maintained this tradition and formalized a gatekeeper system by which specialty and hospital services (except in emergencies) are available only by referral from a GP. Every person in the United Kingdom who wants to use the NHS must be enrolled on the list of a GP. There is free choice of GP (unless the GP’s list of patients is full), and people can switch from one GP’s list to another.

Whereas the creation of the NHS in 1948 left primary care essentially unchanged, it revolutionized Britain’s hospital sector. As in the United States, hospitals had mainly been private nonprofit institutions or were run by local government; most of these hospitals were nationalized and arranged into administrative regions. Because the NHS unified the United Kingdom’s hospitals under the national government, it was possible to institute a true regionalized plan (see Chapter 5).

Patient flow in a regionalized system tends to go from GP (primary care for common illnesses) to local hospital (secondary care for more serious illnesses) to regional or national teaching hospital (tertiary care for complex illnesses). Traditionally, most specialists have had their offices in hospitals. As in Germany, GPs do not provide care in hospitals. GPs have a tradition of working closely with social service agencies in the community, and home care is highly developed in the United Kingdom.

Dr. Timothy Broadman does not think much about money when he goes to his surgery (office) each morning. He receives a payment from the NHS to cover part of the cost of running his office, and every month he receives a capitation payment for each of the 1750 patients on his list. Ten percent of his income has been coming from extra fees he receives when he gives vaccinations to the kids; does Pap smears, family planning, and other preventive care; and makes home visits after hours. Recently, he also received a substantial bonus from the new pay-for-performance system.

Since early in the twentieth century, the major method of payment for British GPs has been capitation (see Chapter 4). This mode of payment did not change when the NHS took over in 1948. The NHS did add some fee-for-service payments as an encouragement to provide certain preventive services and home visits during nights and weekends. Consultants (specialists) are salaried employees of the NHS, although some consultants are allowed to see privately insured patients on the side, whom they bill fee-for-service.

In 2004, a major new payment mode began for GPs: pay for performance (P4P) (see Chapter 10), known in the United Kingdom as the Quality and Outcomes Framework. NHS management negotiated the program with the British Medical Association (BMA), and the success of the negotiations was in large part because of the government’s policy of increasing payment to GP, whose average income rose by 60% from 2002 to 2007, with GP incomes approaching those of hospital specialists (Doran and Roland, 2010). The NHS and BMA agreed on dozens of clinical indicators measuring quality for preventive services and common chronic illnesses such as coronary heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, and asthma. In addition, physician practices are measured on practice organization—involving such measures as documentation in medical records, ability of patients to access the practice by phone, computerization, and safe management of medications—and on the patient experience as measured by patient surveys. Physician practices were awarded a maximum of 1050 points for GPs who performed well on all these measures. In 2005, each point was worth approximately £120 annually (more than $200). GP practices achieving maximum quality could potentially increase earnings by approximately $77,000 per physician (Roland, 2004).

In preparation for P4P, UK GP practices employed more nurses, established chronic disease clinics, and increased use of electronic medical records. In the first year of the program, practices in England scored a median of 1003 points, suggesting that a high level of quality was achieved. Moreover, performance improved faster among lower-quality practices, which narrowed inequalities in care. As a result, GP income increased markedly and the cost to the NHS was far greater than expected.

The extent to which actual quality was improved is unclear; successes may have been related in part to improved documentation rather than improved quality. Practices were allowed to exclude certain patients in the performance calculations on the basis of repeated no-shows, serious comorbidities, and other factors, introducing the possibility of “gaming” the system. An analysis of performance improvement prior to and following the introduction of P4P suggests that performance had been increasing before P4P, but that quality increased slightly faster after P4P for some chronic conditions. Nurses in GP practices were responsible for much of the quality improvement, as GPs delegated many preventive and chronic care tasks to them.

By 2009, an evaluation of the Quality and Outcomes Framework revealed that the rate of improvement in the quality of care increased for asthma and diabetes from 2003 to 2005, but not for heart disease. By 2007 the rate of improvement had slowed for all three conditions. Many practices had reached the quality benchmarks, which meant that the financial incentive to continue improving was blunted. Moreover, performance for quality measures removed from the Framework fell in some cases, suggesting that practices might neglect quality of care unassociated with financial rewards. No significant changes were found in patient reports of access to care and interpersonal aspect of care, but continuity of care decreased after the introduction of the Framework (Campbell et al, 2009; Doran and Roland, 2010).

Health expenditures in the United Kingdom accounted for 7.0% of the gross domestic product (GDP) in 2000, far below the US figure of 13.4%. Believing that the NHS needed more resources, the government of Prime Minister Tony Blair infused the NHS with a major increase in funds. Between 1999 and 2004, the number of NHS physicians increased by 25%. In addition, the pay-for-performance system channeled the equivalent of several billion new dollars into physician practices (Roland, 2004; Klein, 2006). By 2008, health expenditures as a proportion of the GDP had risen to 8.7% and per capita spending had increased from $1837 (2000) to $3129 (2008), a 37% increase (OECD, 2010). In 2005, as a result of this large growth in health expenditures, the NHS found itself in a serious deficit and scaled back some of the increase in NHS staffing (Klein, 2006).

In spite of these developments, the United Kingdom continues to have a relatively low level of per capita health expenditures. Two major factors allow the United Kingdom to keep its health care costs low: the power of the governmental single payer to limit budgets and the mode of reimbursement of physicians. While Canada also has a single payer of health services, it pays most physicians fee-for-service and had to create physician expenditure caps (like Germany) in an attempt to control the inflationary tendencies of fee-for-service reimbursement. In contrast, the United Kingdom relies chiefly on capitation and salary to pay physicians; payment can more easily be controlled by limiting increases in capitation payments and salaries. Moreover, because consultants (specialists) in the United Kingdom are NHS employees, the NHS can and does tightly restrict the number of consultant slots, including those for surgeons. As a result, queues have developed for nonemergency consultant visits and elective surgeries (Hurst and Siciliani, 2003). From 2005 to 2007, 30% of patients with cerebrovascular events and an indication for carotid artery surgery experienced a delay of over 12 weeks in spite of national guidelines recommending surgery within 2 weeks of the onset of symptoms (Halliday et al, 2009). In 2006, the United Kingdom had 5.6 MRI scanners per million population compared with the US rate of 25.9 (OECD, 2010). Overall, the United Kingdom controls costs by controlling the supply of personnel and facilities and the budget for medical resources, and by investing heavily in a primary care system that has achieved some of the best quality measures in the developed world (Doran and Roland, 2010).

The United Kingdom is often viewed as a nation that rations certain kinds of health care. In fact, primary and preventive care are not rationed, and average waiting times to see a GP in the United Kingdom are significantly shorter than those for people in the US seeking medical appointments (Schoen et al, 2010). Overall, a striking characteristic of British medicine is its economy. British physicians simply do less of nearly everything—perform fewer surgeries, prescribe fewer medications, order fewer x-rays, and are more skeptical of new technologies than US physicians (Payer, 1988).

A series of dramatic structural changes have been introduced into the NHS over the past 2 decades. In 1991, the Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher implemented market-style reforms requiring hospitals to compete for business by reducing delays for specialty and surgical care, and introducing general practitioner fundholding, by which GP practices could choose to receive a global budget to purchase all care for their panel of patients. In 1997, Tony Blair’s Labor government abolished GP fundholding and replaced it with primary care trusts—a network of GPs working in the same district. All GP practices were required to join a primary care trust, which was given the responsibility for planning primary care and community health services in its area, contracting with hospitals and hospital consultants for specialty care, scrutinizing GP practice patterns, and implementing quality improvement activities. The average primary care trust had approximately 50 GP members, as well as additional primary care representatives from other professions, and covered a population of approximately 100,000 enrolled patients (Figure 14–4). Eighty-five percent of NHS funding flowed through the trusts, which were responsible for contracting for specialty and hospital services (Klein, 2004). As a result of the package of reforms (primary care trusts, the Quality and Outcomes Framework, and increased NHS funding), waiting times dropped, primary care access increased, chronic disease outcomes improved, and patient satisfaction grew.

Figure 14–4. The British National Health Service: Recent reforms.

In 2010, the new coalition government proposed yet another major structural reform, abolishing the primary care trusts but strengthening the policy of giving groups of GPs large budgets from which they will fund primary care and buy specialty care for their patients. These GP commissioning groups will receive up to 70% of the NHS budget. GPs will either organize consortia to receive their budgets or be assigned to a consortium. This reform is touted as a shift in control from managers to physicians even though it is not clear that GPs want to manage budgets. As of early 2011, 170 consortia have been formed and 100 more are emerging. As the third major upheaval in 20 years, with each turnaround requiring several years to implement, it is unclear how health care providers and patients will fare in this constantly changing environment (Roland and Rosen, 2011), with critics complaining about a pattern of repeated “redisorganization” of the NHS from one governing party to the next.

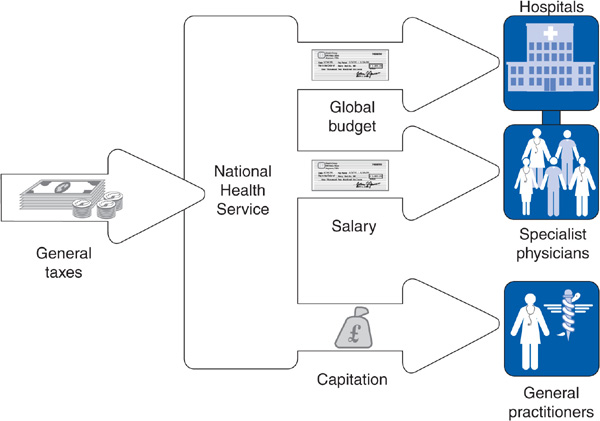

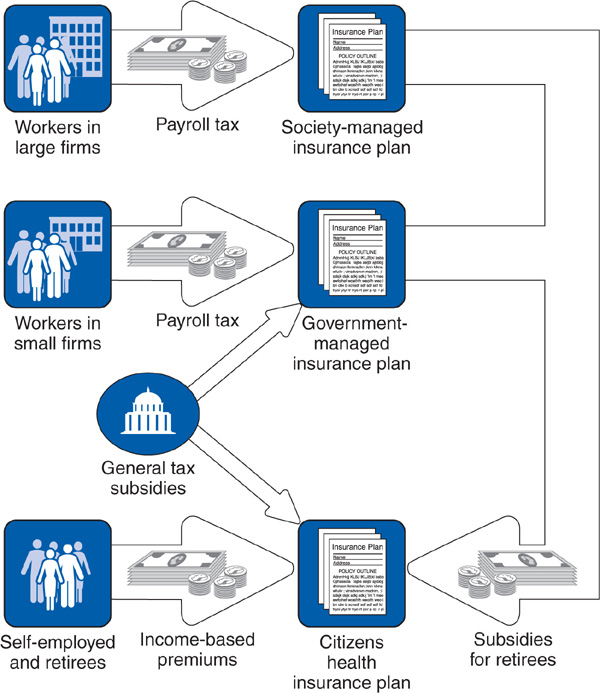

Akiko Tanino works in the accounting department of the Mazda car company in Tokyo. Like all Mazda employees, she is enrolled in the health insurance plan directly operated by Mazda. Each month, 4% of Akiko’s salary is deducted from her paycheck and paid to the Mazda health plan. Mazda makes an additional payment to its health plan equivalent to 4% of Akiko’s salary.

Akiko’s father Takeshi recently retired after working for many years as an engineer at Mazda. When he retired, his health insurance changed from the Mazda company plan to the community-based health insurance plan administered by the municipal government where he lives. Mazda makes payments to this health insurance plan to help pay for the health care costs of the company’s retirees. In addition, the health insurance plan requires that Takeshi pay the plan a premium indexed to his income.

Akiko’s brother Kazuo is a mechanic at a small auto repair shop in Tokyo. He is automatically enrolled in the government-managed health insurance plan operated by the Japanese national government. Kazuo and his employer each contribute payments equal to 4.1% of Kazuo’s salary to the government plan.

Although Japanese society has a cultural history distinct from the other nations discussed in this chapter, its health care system draws heavily from European and North American traditions. Similar to Germany, Japan’s modern health insurance system is rooted in an employment-linked social insurance program. Japan first legislated mandatory employment-based social insurance for many workers in 1922, building on preexisting voluntary mutual aid societies. The system was gradually expanded until universal coverage was achieved in 1961 with passage of the National Health Insurance Act. The Japanese insurance system differs from the German model by having different categories of health plans with even more numerous individual plans and less flexibility in choice of plan (Figure 14–5).

Figure 14–5. The Japanese health system.

Employers with 700 or more employees are required to operate self-insured plans for their employees and dependents, known as “society-managed insurance” plans. Although these plans resemble the German industry-specific sickness funds, each company must operate its own individual health plan. Approximately 1800 different employer-based plans exist. Eighty-five percent of these society plans are operated by individual companies, with the balance operated as joint plans between two or more employers, although none involve as many companies as the typical German sickness fund. The boards of directors of society plans comprise 50% employee and 50% employer representatives. Employees and their dependents are required to enroll in their company’s society plan, and the employee and the employer must contribute a premium to fund the society. Because each plan is self-insured, the premium rate varies (from 3% to 9.5% in 2006) depending on the average income and health risk of the company’s employees, creating considerable inequities (Imai, 2002; Kemporen, 2007). Society-managed insurance plans cover 24% of the Japanese population.

Employees and dependents in companies with fewer than 700 employees are compulsorily enrolled in a single national health insurance plan for small businesses that is operated by the national government. This government-managed insurance plan, primarily financed by a premium (8.2% in 2006) on employers and employees, covers 28% of the population. The federal government also uses general tax revenues to subsidize the government-managed insurance plan.

Yet a third type of health insurance, community-based health insurance (also called citizens’ health insurance), covers self-employed workers and retirees (41% of the population). Each municipal government in Japan administers a local citizen’s insurance plan and levies a compulsory premium on the self-employed workers and retirees in its jurisdiction. In addition, each employer-operated society-managed insurance plan and the single government-managed insurance plan must contribute payments to subsidize the costs for retirees. Approximately 40% of the financing for the citizens health insurance program comes from contributions from the society-managed and government-managed insurance plans, making employers liable for a large portion of the costs of their retirees’ health care. Additional funds for the community-based health insurance plan come from general tax revenues.

A smattering of smaller insurance programs exist for government employees and other special categories of workers, and resemble the society-managed insurance plans. Persons who become unemployed remain enrolled in their health plan with the payroll tax waived. All plans are required to provide standard comprehensive benefits, including payment for hospital and physician services, prescription drugs, maternity care, and dental care. In addition, in 2000 Japan implemented a new long-term insurance plan, financed by general tax revenues and a new earmarked income tax, which provides comprehensive benefits to disabled adults, including payment for home care, case management, and institutional services.

Because Japan’s society is aging more rapidly than any other developed nation, inequities and imbalances have developed in the financing of care for the most expensive patients—those at the highest age levels. In 2006, a new law was passed creating a more rational financing plan for retirees older than 75 (Kemporen, 2007).

In summary, Japan—like Germany—builds on an employment-based social insurance model, using additional general tax subsidies to create a universal insurance program. Compared with Germany, the national and local governments in Japan are more involved in directly administering health plans and a majority of Japanese are covered by government-run or government-managed plans rather than by employer-managed private plans (Kemporen, 2007).

Takeshi Tanino’s knee has been aching for several weeks. He makes an appointment at a clinic operated by an orthopedic surgeon. At the clinic Takeshi has a medical examination, an x-ray of the knee, and is scheduled for regular physical therapy. During the examination the orthopedist notes that Takeshi’s blood pressure is high and recommends that Takeshi see an internist at a different clinic about this problem.

Six months later, Takeshi develops a cough and fever. He makes an appointment at the medical clinic of a nearby hospital run by Dr. Suzuki, is diagnosed with pneumonia, and is admitted to the medical ward. He is treated with intravenous antibiotics for 2 weeks and remains in the hospital for an additional 2 weeks after completing antibiotics for further intravenous hydration and nursing care.

Health plans place no restrictions on choice of hospital and physician and do not require preauthorization before using medical services. Most medical care is based on three types of settings: (1) independent clinics, each owned by a physician and staffed by the physician and other employees, with many clinics also having small inpatient wards; (2) small hospitals with inpatient and outpatient departments, owned by a physician with employed physician staff; and (3) larger public and private hospitals with outpatient and inpatient departments and salaried physician staff. Facilities are organized by specialty, with larger hospitals having a wide range of specialties and smaller hospitals and clinics offering a more limited selection of specialty departments. Care is delivered in a specialty-specific manner, with a few organizations using a primary care-oriented gatekeeper model (Reid, 2009).

Physician entrepreneurship is a strong element in the organization of health care in Japan. Most clinics and small hospitals are family-owned businesses founded and operated by independent physicians. Unlike clinics in the United States such as the Mayo Clinic and Palo Alto Medical Foundation that began as family-owned institutions but evolved into nonprofit organizations with ownership shared among a larger group of physician partners, most clinics in Japan have remained under the ownership of a single physician, often passed down within a family from one generation to another. Many physicians expanded their clinics to become small hospitals, but the government builds and operates the larger medical centers. The distinction between clinics and hospitals in Japan is not as great as in most nations. Clinics are permitted to operate inpatient beds and only become classified as hospitals when they have more than 20 beds. Approximately 30% of clinics in Japan have inpatient beds. Virtually all physicians either own clinics and hospitals or work as employees of a clinic or hospital, and practice only within their single institution. Although many physician-owned clinics and hospitals are modest facilities, others are larger institutions offering a wide array of outpatient and inpatient services featuring the latest biomedical technology, electronic medical records, and automated dispensing of medications.

Rates of hospital admission are relatively low in Japan and rates of surgery are approximately one-third the rate in the United States. A cultural norm that makes patients reluctant to undergo invasive procedures in part explains the low surgical rate in Japan. When hospitalized, patients remain unusually long compared with most developed nations; average lengths of stay vary by hospital from 16 to 29 days. Patients are allowed long periods to convalesce while still in the hospital (Ikegami and Campbell, 2004).

One month after returning home from the hospital, Takeshi Tanino develops stomach pain that awakens him several nights. He makes an appointment at a general medical clinic run by Dr. Sansei. Dr. Sansei performs an endoscopy, which reveals gastritis. Dr. Sansei prescribes an H2 blocker and arranges for Takeshi to return to the clinic every 4 weeks for the next 6 months. Takeshi’s stomach ache improves after a few days of using the medication. At each follow-up visit, Dr. Sansei questions Takeshi about his symptoms and dispenses a new 4-week supply of medications.

Until recently, insurance plans paid both physicians and hospitals on a fee-for-service basis. In 2003, a per diem hospital payment based on diagnosis was introduced (Nawata et al, 2009) while physicians continue to be paid fee-for-service. The government strictly regulates physician fees, hospital payments, and medication prices, which are very low by US standards. The fee schedule is in many ways the opposite of US fees: In Japan, primary care services tend to command higher fees than do more specialized services such as surgical procedures and imaging studies. Services such as MRI scans that have shown large increases in volumes have had substantial cuts in fees (Ikegami and Campbell, 2004). Based on fee schedules in place in 2007, a family physician office visit might be reimbursed $5 or $10, one night’s stay in a hospital $11, and a brain MRI $105 (Reid, 2009). Physicians make up for low fees with high volume, at times seeing 60 patients per day. In 2007 the number of physician visits per capita was 13.4, compared with 4.0 for the United States (OECD, 2010). Physicians are permitted to directly dispense medications, not just to prescribe them, and make a profit from the sale of pharmaceuticals. The government recently restricted how much physicians could charge patients for medications (Kemporen, 2007), but many physician visits are solely for the purpose of refilling medications. Quality of care in Japan is not systematically measured and is believed to vary greatly among physicians and hospitals (Henke et al, 2009).

Health care costs in Japan were only 8.1% of GDP in 2007. However this is a considerable rise from 1990’s 6.0%, and concerns are mounting due to Japan’s demographics. The health care system relies heavily on payroll taxes and thus requires a large employed population. But with, a plummeting birth rate and the longest life expectancy in the world, Japan’s population is aging faster than that of other developed nations. The proportion of Japanese older than 65 years is projected to increase from 12% in 1990 to 40% in 2050 (Kemporen, 2007). In comparison, the proportion of the US population older than 65 years will increase much more modestly, from 12% to 21%, during this same period.

Through its fee schedule, the government has kept medical prices low, which is the main cost containment strategy. But physicians are unhappy and see too many patients for short visits, while many hospitals are old and underfunded. The stresses resulting from Japan’s demographic reality and its overstretched health care providers make for an uncertain future (Reid, 2009).

Key issues in evaluating and comparing health care systems are access to care, level of health expenditures, public satisfaction with health care, and the overall quality of care as expressed by the health of the population. Germany, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Japan provide universal financial access to health care through government-run or government-mandated programs. These four nations have controlled health care costs more successfully than has the United States (Tables 14–1 and 14–2), though all four face challenges in containing their spending.

Table 14–1. Total health expenditures as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), 1970–2008

Table 14–2. Per capita health spending in US dollars, 2008

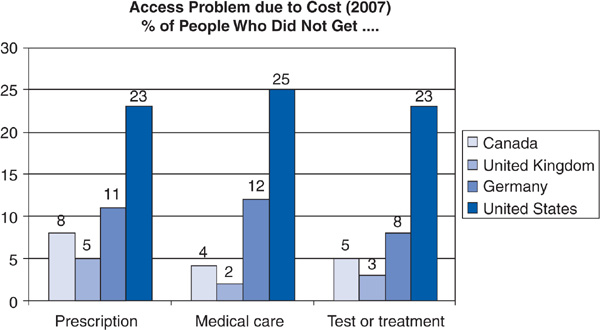

Sixteen percent of US adults surveyed in 2007 felt that the health system works well with only minor changes needed; 48% felt that fundamental change is needed, and 34% wanted the system rebuilt completely. Adults in Germany, Canada, and the United Kingdom had somewhat more favorable views of their health systems, though the majority in those countries also felt that major changes were needed (Schoen et al, 2007). Adults in the United States were much more likely than adults in Germany, the United Kingdom, and Canada to report problems with access to medical services due to costs (Figure 14–6).

Figure 14–6. Problems accessing medical services due to costs.

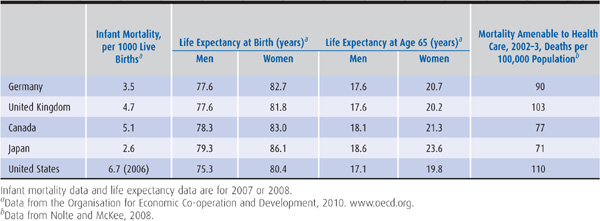

Crossnational comparisons of health care quality are treacherous since it is difficult to disentangle the impacts of socioeconomic factors and medical care on the health status of the population. But such comparisons can convey rough impressions of whether a health care system is functioning at a reasonable level of quality. From Table 14–3, it is clear that the United States has an infant mortality rate higher than Germany, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Japan, with the Japanese rate being the lowest. Japan also has the highest male and female life expectancy rates at birth. The life expectancy rate at age 65 is believed by some observers to measure the impact of medical care, especially its more high-tech component, more than it measures underlying socioeconomic influences. Even by this standard, the United States ranks below the other four nations (OECD, 2010). Researchers have developed another metric intended to assess the functioning of national health care systems, known as “mortality amenable to health care” (Nolte and McKee, 2008); the United States performs poorly on this metric as well relative to other nations (Table 14–3).

Table 14–3. Health outcome measures

Just as epidemiologic studies often derive their most profound insights from comparisons of different populations (see Chapter 11), research into health services can glean insights from the experience of other nations. As the United States confronts the challenge of achieving universal access to high-quality health care at an affordable cost, lessons may be learned from examining how other nations have addressed this challenge.

Anderson GF et al. It’s the prices, stupid: Why the United States is so different from other countries. Health Aff. 2003;22(3):89.

Barer ML, Lomas J, Sanmartin C. Re-minding our Ps and Qs: Medical cost controls in Canada. Health Aff. 1996;15(2):216.

Busse R. The health system in Germany. Eurohealth. 2008;14(1):5.

Busse R, Riesberg A. Health Care Systems in Transition: Germany. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2004.

Campbell SM et al. Effects of pay for performance on the quality of primary care in England. N Engl J Med. 2009;261:368.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Health Care in Canada, 2010, December 2010. www.cihi.ca.

Collier R. Shift toward capitation in Ontario. Canadian Med Assoc J. 2009;181:668.

Doran T, Roland M. Lessons from major initiatives to improve primary care in the United Kingdom. Health Aff. 2010;29:1023. https://www.mckinseyquarterly.com/Improving_Japans_health_care_system_2311. Accessed November 17, 2011.

Guilfoyle J. Prejudice in medicine. Our role in creating health care disparities. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:1511.

Halliday AW et al. Waiting times for carotid endarterectomy in UK. BMJ. 2009;338:b1847.

Henke N et al. Improving Japan’s health care system. McKinsey Q. 2009.

Hurst J, Siciliani L. Tackling Excessive Waiting Times for Elective Surgery: A Comparison of Policies in Twelve OECD Countries. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; 2003.

Hutchison B et al. Primary health care in Canada: Systems in motion. Milbank Q. 2011:89(2):256.

Ikegami N, Campbell JC. Japan’s health care system: Containing costs and attempting reform. Health Aff. 2004;23(3):26.

Imai Y. Health Care Reform in Japan. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, February 2002. www.oecd.org.

Katz SJ et al. Phantoms in the snow: Canadians’ use of health care services in the United States. Health Aff. 2002;21(3):19.

Kemporen (National Federation of Health Insurance Societies). Health Insurance, Long-Term Care Insurance and Health Insurance Societies in Japan, 2007. Kemporen, 2007.

Klein R. Britain’s National Health Service revisited. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:937.

Klein R. The troubled transformation of Britain’s National Health Service. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:409.

Nawata K, et al. Analysis of the new medical payment system in Japan, July 2009. www.mssanz.org.au/modsim09/A2/nawata.pdf.

Nolte E, McKee CM. Measuring the health of nations: Updating an earlier analysis. Health Aff. 2008;27:58. Erratum in: Health Aff. 2008;27:593.

Ornyanova D, Busse R. Health Fund now operational Health Policy Monitor, May 2009. www.hpm.org.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Health Data, 2010. www.oecd.org.

Payer L. Medicine and Culture. New York: Henry Holt; 1988. Reid TR. The Healing of America. New York: The Penguin Press; 2009.

Reinhardt U. Why does US health care cost so much? Economix. November 14, 2008. http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com.

Roland M. Linking physicians’ pay to the quality of care—a major experiment in the United Kingdom. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1448.

Roland M, Rosen R. British NHS embarks on controversial and risky market-style reforms in health care. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1360.

Ross JS, Detsky AS. Choice? Making health care decisions in the United States and Canada. JAMA. 2009;302:1803.

Sanmartin C et al. Comparing health and health care use in Canada and the United States. Health Aff. 2006;25:1133.

Schoen C et al. Toward higher-performance health systems: Adults’ health care experiences in seven countries, 2007. Health Aff. 2007;26:w717.

Schoen C et al. How health insurance design affects access to care and costs: by income, in eleven countries. Health Aff. 2010;29:2323.

Steinbrook R. Private health care in Canada. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1661.

Stock S et al. The influence of the labor market on German health care reforms. Health Aff. 2006;25:1143.

Taylor MG. Insuring National Health Care. The Canadian Experience. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press; 1990.

Willcox S et al. Measuring and reducing waiting times: A cross-national comparison of strategies. Health Aff. 2007;26:1078.

Woolhandler S et al. Costs of health care administration in the United States and Canada. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:768.

Zander B et al. Health policy in Germany after the election. Health Policy Monitor. November 2009. www.hpm.org.