Study Notes for Ezra

EZRA—NOTE ON 1:1–2:70 Cyrus’s Decree and the Return of Exiles from Babylon. With the eye of faith, Ezra describes monumental political changes in the world as God’s special favor for his people.

EZRA—NOTE ON 1:1–11 King Cyrus of Persia decrees that Jewish exiles may return to Jerusalem and rebuild the ruined temple.

EZRA—NOTE ON 1:1–4 The Decree. In the famous Cyrus Cylinder, the king boasts that those “of the holy cities beyond the Tigris whose sanctuaries had been in ruins over a long period … I returned to their places.” Ezra 1 reflects that proclamation as it affected the Jews.

EZRA—NOTE ON 1:1 the first year of Cyrus. The narrative of Ezra continues from Chronicles (see 2 Chron. 36:22–23). The year of the decree is 538 B.C. (for more on the date and occasion, see Introduction: Date). that the word of the LORD by the mouth of Jeremiah might be fulfilled. See Jer. 25:11–14; 32:36–38. The whole book of Ezra is the story of God’s work to fulfill his promises by bringing his people back from exile and establishing them once again in their land. The prophet Jeremiah had foretold an exile lasting 70 years, after which time Babylon would be punished and Judah restored. the LORD stirred up the spirit of Cyrus king of Persia. This acknowledgment of God’s hand behind the events of the book is the perspective through which all those events are to be viewed (cf. Ezra 1:5; 3:11; 5:5; 6:22; 7:6, 9; 8:18, 22; 10:14). On Cyrus’s role, see also Isa. 44:28; 45:1. Cyrus’s proclamation is only the beginning of a series of events that will fulfill the prophecy. It is first made orally, and carried through the vast Persian Empire (see map; also Est. 1:22), and then set down in writing, giving it the status of a solemn decree.

EZRA—NOTE ON 1:2 The name God of heaven is used elsewhere for the Lord when Jews relate to non-Jews (see 5:12). Cyrus uses diplomatic language typical of the time, yet what he says corresponds to the message of the book of Ezra.

EZRA—NOTE ON 1:3–4 he is the God who is in Jerusalem. No doubt this is Cyrus’s real view, although he is not necessarily claiming that there is only one God; he may be allowing for other gods (cf. the statement of Darius the king in 6:12). go up to Jerusalem. The phrase implies worship (cf. Ps. 122:1). The focus of the decree is the rebuilding of the temple more than the returning of the exiles in itself. Cyrus both urges Jews to return and obliges the people of his kingdom to supply them with what they need for the temple and its worship. See also Ex. 12:35–36.

EZRA—NOTE ON 1:5–11 The Exiles Respond to the Decree. The exiles’ leaders gather money and materials for the temple. Cyrus brings the items taken from the temple in 586 B.C. for the people to take back to Jerusalem.

EZRA—NOTE ON 1:5 Those exiles whose spirit God had stirred (as he had stirred up Cyrus, v. 1) respond to the decree. The response is spearheaded by the leadership of the people, namely, the heads of the fathers’ houses (extended families) and priests. It is not haphazard, but an action of the exiled community as a whole. The three tribes—Judah, Benjamin, and the Levites (Levi)—are those that had constituted the former kingdom of Judah, and had thus been taken off to Babylon in 586 B.C. No mention is made here or elsewhere of any large-scale return of the other tribes, though a few people from other tribes are sometimes mentioned or implied (see 1 Chron. 9:3; 2 Chron. 11:16; cf. Luke 2:36). The OT gives no further information on the fate of the other “lost tribes.”

EZRA—NOTE ON 1:6–11 People help the exiles as commanded by their king, and Cyrus gives back the vessels of the house of the LORD (v. 7), once stolen from the temple (2 Kings 25:13–17). These are handed over to Sheshbazzar (Ezra 1:8), one of the early leaders of the returning exiles. The title prince of Judah (v. 8) simply means that he was a leading member of the exiled community. In 5:14–16 the initiation of the temple’s reconstruction is attributed to Sheshbazzar, and there he is called “governor.”

EZRA—NOTE ON 1:9 And this was the number of them: 30 basins of gold, 1,000 basins of silver, 29 censers. This detailed catalog of vessels used in the temple in Jerusalem is a testimony to God’s faithfulness in preserving not only a remnant of the people but also the materials they would need to reinstate temple worship in Jerusalem. God had not forgotten his promises.

EZRA—NOTE ON 2:1–70 The Exiles Live Again in Their Ancestral Homes. This long chapter documents the exiles’ return from Babylon to resettle in their former homes in Jerusalem and Judah. (The information from ch. 2 is given again in Neh. 7:6–73 in connection with a covenant renewal under Nehemiah.) It shows that the exiled Judeans responded to Cyrus’s decree and took it as a fulfillment of prophecy. The return is not just the end of the exile but also a reoccupation of the ancient homeland.

Judea under Persian Rule

538–332 B.C.

Under Persian rule, the lands of Israel (now called Samaria) and Judah (now called Judea) were minor provinces within the satrapy called Beyond the River. It appears that Edomites encroached upon Judea’s southern border after the fall of Jerusalem to the Babylonians, and this territory was now called Idumea. These regional boundaries remained more or less the same throughout the Persian period. Returning Judeans settled mostly in the province of Judea, but a few settled in the plain of Ono and Idumea as well.

EZRA—NOTE ON 2:2a The leaders of the community are named, with Zerubbabel, the main figure, and Jeshua, the priest, given pride of place (see also Hag. 1:12–14; Zech. 3:1–10; 4:7–10). Zerubbabel descended from King Jehoiachin (cf. 1 Chron. 3:16–19, where he is called Jeconiah), who was exiled in 597 B.C. and later given a place of honor in the Babylonian court (2 Kings 24:15; 25:27–30). Haggai recalls his royal lineage (Hag. 2:23; cf. Jer. 22:24). The other names in Ezra 2:2 are mostly unknown. (The Nehemiah who later rebuilt the walls of Jerusalem came almost a century after these first returnees; the Mordecai of the book of Esther was also much later, and did not return to Jerusalem. Rehum may be the same as in 4:8.) Some exiles may have taken Babylonian names, as occurs in the book of Daniel (e.g., Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego; see Dan. 1:7).

EZRA—NOTE ON 2:2b–70 Those who returned are divided into ordinary Israelites (vv. 2b–35) and servants of the temple, including priests and Levites (vv. 36–58). (The same division recurs in vv. 59–63, regarding legitimacy.) The balance shows a clear interest in the temple and its staffing. This return is about reestablishing the worship of Yahweh there.

EZRA—NOTE ON 2:2b–35 The laity is described partly according to kinship divisions (vv. 2b–19) and partly according to place (vv. 20–35), without a real distinction in the form (the men of and the sons of seem interchangeable). The numbers may come from a census. The list shows an interest in the legitimate membership of the covenant people, as well as the legitimate reclaiming of ancestral land. The places that are named are in the territories of Judah and Benjamin (cf. 1:5), north and south of Jerusalem; a large proportion of the territories are actually in Benjamin (cf. Josh. 18:21–27). Some of them recall the first conquest of Canaan by Joshua (e.g., Bethel and Ai).

EZRA—NOTE ON 2:36–58 The temple officials are divided according to function, headed by the priests and Levites. The priests (vv. 36–39) are the most important group, for they are set apart for worship at the altar; the Levites are attendants, some of them singers and gatekeepers (vv. 40–42; see also 1 Chron. 6:33–43; 9:17–18). Three of the priestly names given here (Jedaiah, Immer, Pashhur) also appear in 1 Chron. 9:10–13 in that list of those who returned from exile (cf. also Jer. 20:1–6). The number of Levites is surprisingly low compared to the priests.

EZRA—NOTE ON 2:43–54 The temple servants (Hb. netinim, a term appearing only in Ezra, Nehemiah, and 1 Chron. 9:2) were a further, lower class of officials appointed by King David to help the Levites (cf. Ezra 8:20). There may be a connection between them and the Gibeonites, whom Joshua made servants of the sanctuary (Josh. 9:23, 27). Here, however, they are apparently not slaves, and in Neh. 10:28 they are named among those who take the covenant oath.

EZRA—NOTE ON 2:55–58 The sons of Solomon’s servants may be connected with foreigners whom Solomon originally drafted for building the temple (1 Kings 9:20–21). They are numbered here along with the temple servants (Ezra 2:43), and like them are not regarded as slaves. Presumably they all returned voluntarily from Babylon.

EZRA—NOTE ON 2:59–63 This section considers the legitimacy of claims to citizenship and membership in the priesthood. whether they belonged to Israel. It was important in this returning community to establish credentials. People were coming back after a long exile to claim inheritance and property. In the case of priests, it was paramount that only those with the correct pedigree should officiate at the altar. Such claims needed evidence, and the record inevitably contained gaps. The claims entered here are not permanently refused, but held over, pending further inquiry.

EZRA—NOTE ON 2:64–70 The conclusion of the chapter gives numbers of the whole assembly (vv. 64–66), then gives the number of their livestock, and closes with a picture of full resettlement (v. 70). The crucial importance of the temple project to the whole returning enterprise is signaled in vv. 68–69, where some heads of families, i.e., key people in the community, give of their own substance to initiate the rebuilding (cf. Ex. 36:2–7). The location of the former temple is regarded as a holy place, such that it can already be called the house of the LORD that is in Jerusalem.

EZRA—NOTE ON 2:69 darics. A daric was a gold coin used throughout the Persian Empire. Introduced by Darius I at the end of the sixth century B.C., it weighed about 0.3 ounces (8.5 grams). Beginning in the second half of the fifth century B.C., these coins with Hebrew letters on them appear in Judah. Several of them bear the name of the Persian province Yehud (i.e., Judah), which probably indicates that the province had some freedom to mint its own coins.

EZRA—NOTE ON 3:1–6:22 The Returned Exiles Rebuild the Temple on Its Original Site. The book of Ezra spans several generations, as the returnees rebuild and encounter resistance, and finally receive renewed imperial authorization for their efforts.

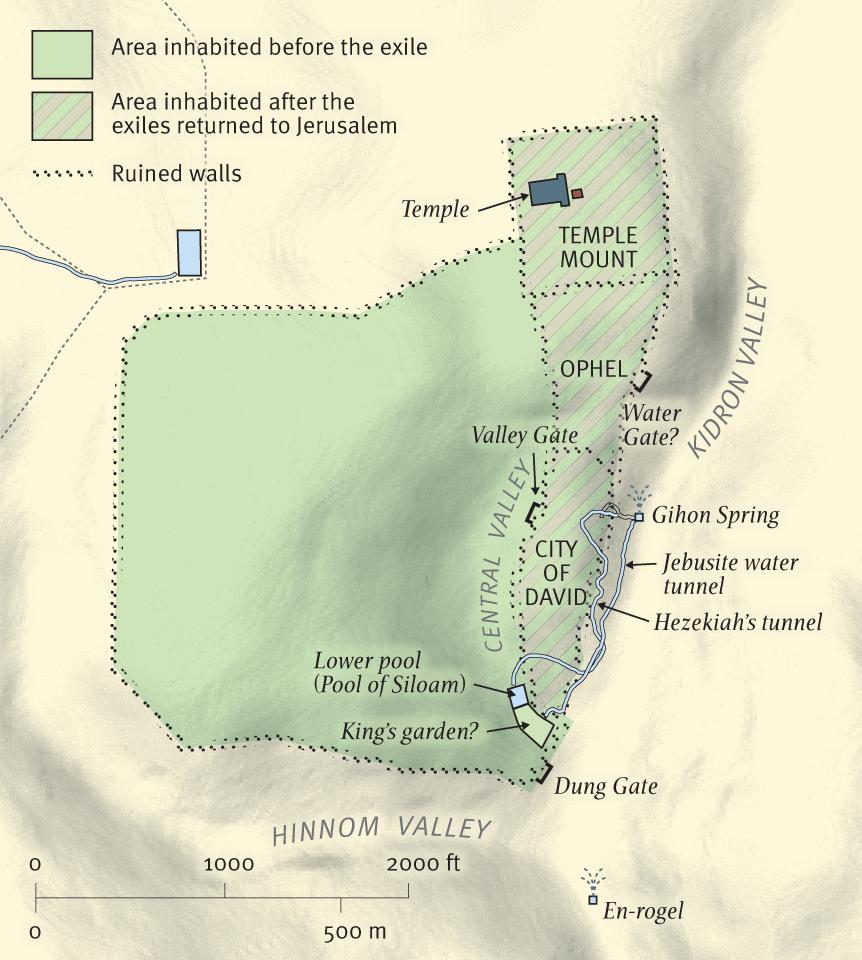

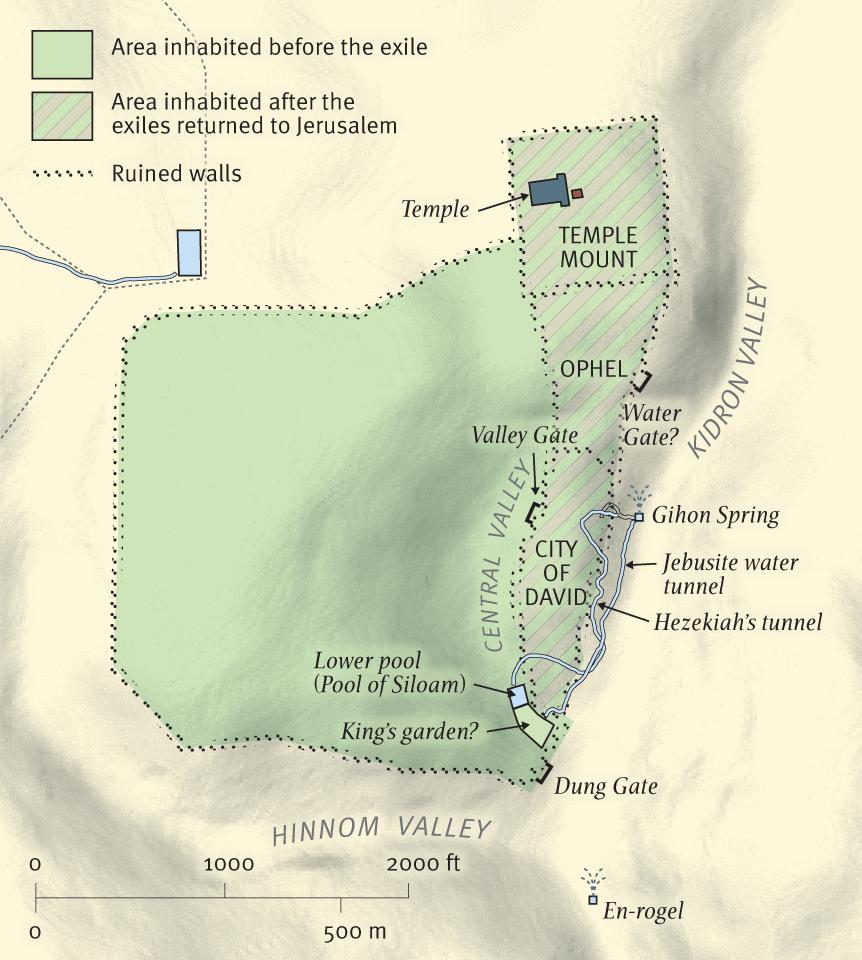

Jerusalem at the Time of Zerubbabel

538–515 B.C.

Among the first tasks undertaken upon the exiles’ return was the rebuilding of the altar and the temple. Almost immediately the altar was set up, and regular burnt offerings were resumed. About a year later the foundations of the temple were laid, but opposition from other local governors halted the completion of the temple for over 20 years. Finally, in 515 B.C. (during the reign of Darius) the temple was completed. The city walls, however, would not be rebuilt until about 70 years later under the leadership of Nehemiah.

EZRA—NOTE ON 3:1–13 The Foundations of the Temple Are Laid. In this section the altar is rebuilt on its former site, and foundations are laid for the new temple.

EZRA—NOTE ON 3:1 According to Israel’s calendar of pilgrimage feasts, the seventh month, Tishri (roughly September), was the month of the great Day of Atonement (Lev. 23:26–32), followed by the Feast of Booths (or Tabernacles; Lev. 23:33–43), which celebrated the exodus from Egypt. Thus in the first year of the return, the people make their first pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

EZRA—NOTE ON 3:2 built the altar. On this occasion, the broken altar had first to be repaired so that sacrifices could once again be made. The leading roles of Jeshua and Zerubbabel are again emphasized, with some stress on the role of the priests.

EZRA—NOTE ON 3:3 in its place. There may have been visible remains of the original altar (as perhaps implied by Jer. 41:4–5); in any case, its exact location was evidently known. The altar has absolute priority, as it had at the first entry into the land, many years before (Deut. 27:1–8). The haste to erect it is perhaps heightened by the fear of the peoples of the lands. This phrase refers to residents of Judah, and perhaps neighboring areas, who were not part of the group returning from exile. Some may have had Jewish origins, but they present themselves as a distinct group, and they would soon oppose the work. The exiles’ fear is another echo of their first occupation of the land, when fear had at first overwhelmed the Israelites (Num. 14:1–3). On this occasion, despite their fear, they are resolute. Burnt offerings were to be offered daily on the altar, morning and evening, as Moses commanded in Ex. 29:38–42.

EZRA—NOTE ON 3:4–7 The people keep the Feast of Booths, with its proper sacrifices (see Num. 29:12–38).

EZRA—NOTE ON 3:6 they began to offer. The perspective shifts to the regular sacrificial worship (see 2 Chron. 2:4), since the particular acts of worship in the seventh month are essentially portrayed as a renewal and a beginning. The next task is to rebuild the temple, and the preparations recall those made by King Solomon half a millennium earlier (Ezra 3:7; cf. 1 Kings 5:13–18; 1 Chron. 22:4, 15; 2 Chronicles 2).

EZRA—NOTE ON 3:8 Work begins on the temple itself, with the laying of its foundation in the second year of the return (c. 537 B.C.). The second month, Ziv (1 Kings 6:1)—the same time of year when Solomon had begun his temple (2 Chron. 3:2)—is in the spring. The time of the return from exile is dated with the formula after their coming to the house of God at Jerusalem. Even though the temple still lies in ruins, the place could be called “the house of God” because of its consecration for worship (see Jer. 41:5). The narrator stresses that it is those who have come from the captivity who do this. The priests and Levites are emphasized, and the qualifying age for Levitical service is mentioned (cf. 1 Chron. 23:24).

EZRA—NOTE ON 3:9 The names are those of “Levites,” as specified in v. 8. Thus Jeshua is not the high priest of that name, nor are these Levite sons of Judah members of the tribe of Judah; this “Judah” is probably another form of “Hodaviah,” named along with Kadmiel in 2:40.

EZRA—NOTE ON 3:10–11 all the people shouted with a great shout. The laying of the foundations occasions praise, which echoes the celebrations of King David when he prepared for the building of Solomon’s temple (cf. 1 Chronicles 16, esp. vv. 7, 34, 37).

EZRA—NOTE ON 3:12–13 But many … wept with a loud voice. Sadness is mixed with this rejoicing, for some of the very old remembered the former temple and believed that this new one would not match the former temple’s glory. The picture of mitigated celebration is a small symbol of the whole event of the return, which was in itself a triumph yet fell far short of the great hopes the people might have had (cf. Hag. 2:2–9).

EZRA—NOTE ON 4:1–24 Enemies Stall the Project by Conspiring against It. The rebuilding project encounters opposition from other groups in the region, and the work ceases.

EZRA—NOTE ON 4:1–2 the adversaries of Judah and Benjamin. The returned exiles found themselves in a Persian province, called Beyond the River (v. 11; i.e., beyond the Euphrates from the perspective of the Persian power centers). Its administrative center was in Samaria, the capital of the former northern kingdom of Israel. Its population was composed largely of the descendants of peoples settled there by Esarhaddon king of Assyria (reigned c. 681–669 B.C.) in c. 671–670 (see 2 Kings 17:24–33; Isa. 7:8), long after Assyria conquered the northern kingdom in 722 and began to resettle the land with exiles from other lands. Apparently Samaria was a hotbed of unrest for decades. Let us build with you, for we worship your God as you do. Indeed, these peoples’ ancestors had been taught the religion of Yahweh by a priest sent for that purpose (2 Kings 17:24–28), though the same account tells that they worshiped other gods as well (2 Kings 17:29–41), and they are identified as “adversaries” (Ezra 4:1).

EZRA—NOTE ON 4:3 Zerubbabel, Jeshua, and the rest of the heads of fathers’ houses present a united answer declining the offer of help (vv. 1–2): we alone will build to the LORD. Their stated ground for declining the help is that the decree of Cyrus applied only to the returning exiles. No doubt they understood that the actual intent behind the request was to frustrate the project.

EZRA—NOTE ON 4:4–5 The real attitude of these residents, now called the people of the land, emerges. They showed their determined opposition all the days of Cyrus (from the time the opposition began in 538 or 537 B.C.; Cyrus died in 530) even until the reign of Darius (reigned 522–486). Therefore, the opposition continued over a period of about 20 years, up to the completion of the temple in 516 B.C. The discouragement apparently involved turning local officials against the project. Even though the project actually had the full authority of King Cyrus behind it, local enemies would exploit the distance of Jerusalem from the imperial center to their own advantage.

EZRA—NOTE ON 4:6–23 This section interrupts the historical narrative (1:1–4:5) and mentions two later examples of hostility from the people of the land (4:6 and 4:7–23), showing that persistent and recurring hostility to the returning Jews occurred for a century or more after Cyrus’s decree. The narrative resumes at v. 24. The technique employed was familiar practice in ancient history writing. Its purpose here is to show that the problems faced by the new community were not isolated but were deeply rooted in its situation.

EZRA—NOTE ON 4:6 This verse jumps forward to later events during the reign of Ahasuerus (reigned 486–464 B.C.), otherwise known as Xerxes, who appears in the book of Esther (cf. Est. 1:1).

EZRA—NOTE ON 4:7–23 While the author is on the topic of the opposition by the people of the land, he jumps forward yet further to another hostile episode, when a formal letter of complaint was sent by leaders in the province to King Artaxerxes I (reigned 464–423 B.C.).

Adversaries Hinder Work

View this chart online at http://kindle.esvsb.org/c87

|

Ezra 4:5

|

The people of the land hired counselors to work against the Israelites from the reigns of Cyrus (539–530 B.C.) to Darius (522–486) |

|

Ezra 4:6

|

Accusations arose during the reign of Xerxes (Ahasuerus) (486–464) |

|

Ezra 4:7–23

|

Accusations arose during the reign of Artaxerxes (464–423):

- First threat: they will withhold money (v. 13)

- Second threat: the king is dishonored (v. 14)

- Third threat: they have rebelled before (v. 15)

- Fourth threat: they will take over the whole area (v. 16)

|

|

Ezra 4:24–6:12

|

Work on the temple stopped from 536–520; Darius finally gives order to rebuild it |

EZRA—NOTE ON 4:7–8 The letter form follows known practice in the Persian period: formal address, greetings, information, and request. The precise occasion of this action against the community is not known, but it presupposed that the people had made an attempt to rebuild the city walls sometime before the mission of Nehemiah, who arrived in 445 B.C. (still in the reign of Artaxerxes) and completed the rebuilding of the walls despite strenuous attempts to stop the work at that time too (Nehemiah 4; 6). The present letter was written in Aramaic, which had been the official imperial language under the Babylonians and was still used in diplomacy. The letter might have been translated into Persian (for the benefit of the king), or into Hebrew (therefore implying that the author knew of a Hebrew copy). But when the letter is introduced in the book of Ezra (Ezra 4:7b), the language changes from Hebrew to Aramaic, and continues in Aramaic until 6:18, returning to Hebrew from 6:19 to the end. Citing the letters in Aramaic gives authenticity to Ezra’s account (cf. also 7:12–26); it is not entirely clear, however, why Ezra’s own narrative in this section also uses Aramaic (e.g., 4:23–5:5; 6:13–18). Perhaps it was natural, given that the letters were in Aramaic. In any case, the reader comes away confident that the author was fluent enough in Aramaic to understand the royal letters.

EZRA—NOTE ON 4:9 The officials give their credentials as leaders and also stress that their rights in the land have imperial warrant because of the older Assyrian resettlements.

EZRA—NOTE ON 4:10 The Assyrian king Osnappar is probably Ashurbanipal (668–627 B.C.); he continued the resettlement of Israel, which his predecessors began (see vv. 1–2).

EZRA—NOTE ON 4:11 Beyond the River. The name of the Persian province, which apparently included Jerusalem, until the decree of Cyrus returned the land to the Jews.

EZRA—NOTE ON 4:12 that rebellious and wicked city. Jerusalem had in fact often been more acquiescent to the empire than the biblical writers thought proper (note the highly critical view of the kings Ahaz and Manasseh in 2 Kings 16–21), though there had been some switching of loyalties during the last days of the kingdom (2 Kings 18:7; 24:1, 20). The letter plays on the empire’s ready suspicions of rebellion. They are finishing the walls and repairing the foundations. By the time of this letter, considerable repair work had already been done on the wall around Jerusalem.

EZRA—NOTE ON 4:13–16 The threat of an independence movement in Jerusalem is exaggerated. The imperial records would include those of Assyria and Babylon, empires to which the Persians regarded themselves legitimate successors.

EZRA—NOTE ON 4:20 mighty kings. A possible reference to the relatively powerful united monarchy under David and Solomon. The king’s response (vv. 17–22) gave license to the enemies of the exiles to stop the work by force, an action that might underlie the news later heard by Nehemiah that the walls of Jerusalem lay in ruins (Neh. 1:3).

EZRA—NOTE ON 4:24 The word then picks up the story from v. 5, before the long interlude of vv. 6–23, bringing the narrative back to the period principally in view (soon after the first return). The story now records the outcome of the mission to prevent the building of the temple. It is implied that the work had ceased soon after it began, i.e., within about two years after c. 537 B.C. (see 3:8). It resumed in the second year of the reign of Darius king of Persia, which is 520 B.C. The period of inactivity therefore lasted around 15 years.

EZRA—NOTE ON 5:1–17 The Work Is Resumed, and Local Officials Seek Confirmation of Cyrus’s Decree. After a period of inactivity, the leaders resume work on rebuilding the temple, and provincial officials inquire into its legitimacy.

EZRA—NOTE ON 5:1–2 The prophets, Haggai and Zechariah, are also known from their books, which contain prophecies made in the second year of King Darius, 520 B.C. (Hag. 1:1; 2:1; Zech. 1:1, 7; cf. note on Ezra 4:24; cf. also 6:14). Haggai proclaims that the people were in trouble because they had lost sight of their top priority of rebuilding the temple (Hag. 1:4–6). Verses 1–2 of Ezra 5 bring out the connection between the prophetic work and the renewed action, following the discouragement recorded in 4:4–5, 24. In beginning again, Zerubbabel and Jeshua are simply reimplementing Cyrus’s decree, recognizing it as the will and purpose of God.

EZRA—NOTE ON 5:3–5 The officials Tattenai and Shethar-bozenai are much more neutral than the officials named in 4:8–10. Clearly they have no knowledge of Cyrus’s decree, no doubt because the work had long stopped, and they presumably came to power only after the exiles first arrived. They are interested only in the proper authorization of this important thing that was happening under their jurisdiction, and they do not actually interfere with the work’s progress. The author knows that a higher authority, the eye of … God (5:5), was watching over the builders’ activity and that God was protecting them (cf. Ps. 33:18).

EZRA—NOTE ON 5:6 The copy of the letter has a formal opening similar to the one in 4:7–16.

EZRA—NOTE ON 5:8 The province of Judah lay within the Persian province Beyond the River, of which Tattenai was governor in Samaria. (Texts from the reign of Darius I dating 520–519 B.C. name the local governor of the province “Beyond the River” as Tattanu [cf. Tattenai; vv. 3, 6; 6:6, 13].) The expression the house of the great God is a diplomatic way of referring to the temple and the God of Israel, and does not imply that the writers of the letter believe in him. The use of huge stones and timber recalls the building of the first temple (1 Kings 6:36; 7:12) and was a common practice in the ancient Near East.

EZRA—NOTE ON 5:9–10 The officials’ concern for administrative propriety is reflected in their inquiries about both the original authorization and the names of those who are to be held responsible for the action being undertaken.

EZRA—NOTE ON 5:11–17 The letter now reports the reply of the Jewish leaders. (Quotation was also a feature of known formal Persian letters.)

EZRA—NOTE ON 5:11 The letter writers probably got their information from the returned exiles themselves, since it reflects their understanding of the situation. We are the servants of the God of heaven and earth. They do not hesitate to say that they are serving not a local deity but the one true God of the whole world. They give this answer instead of giving their individual names when asked (v. 10). The great king of Israel is Solomon.

EZRA—NOTE ON 5:12 This verse sums up the message of 1–2 Kings.

EZRA—NOTE ON 5:13–15 These verses essentially repeat information found in 1:2–4. The report stops short of claiming that Cyrus had also commanded that the building be funded by donations from Babylon (1:4). This was perhaps more than Tattenai (or even the exiles) wished to urge at this point.

EZRA—NOTE ON 5:13 Cyrus the king made a decree. See 1:1–4.

EZRA—NOTE ON 5:14 Sheshbazzar was introduced as “the prince of Judah” in 1:8, being the one who had received directly from King Cyrus the charge to rebuild the temple. Here he is called governor, a name applied to Tattenai himself in 5:3; it seems that the term could be used somewhat loosely, since Judah would not have had a “governor” on a par with the governor of the entire province Beyond the River (v. 6, etc.). Darius’s reply also refers to a “governor of the Jews” (6:7), a name given to Zerubbabel in Hag. 1:1.

EZRA—NOTE ON 5:16–17 it has been in building. The period when building had ceased was irrelevant both to the information Tattenai was giving and to the request he was making. The author therefore omits here the specific work of Zerubbabel, Jeshua, Haggai, and Zechariah (though their names were no doubt among those asked for by the governor, and sent with the letter; see v. 10). Tattenai, following the Jews’ own account, wants to make a link between the original authorization and the present building activity, and so portrays Sheshbazzar as having laid the foundations of the temple, since it was done under his authority, though that achievement is attributed to the work initiated by Zerubbabel and Jeshua in 3:8–10.

EZRA—NOTE ON 6:1–22 King Darius Discovers and Reaffirms Cyrus’s Decree, and the Work Is Completed. A record of Cyrus’s decree is discovered, and King Darius confirms that the Jews are to be allowed to continue the work.

EZRA—NOTE ON 6:1–2 The search for Cyrus’s decree is made first in Babylonia, where Cyrus had declared himself king in 539 B.C. and where many exiled Jews lived. But the scroll containing the record of the decree was found in Ecbatana (v. 2), a summer residence of the Persian kings, where Cyrus may have gone soon after his triumph over Babylon. The province of Media (v. 2) was formerly the seat of an empire itself, but Cyrus had made it part of the Persian realm. Leather scrolls are known to have been used in Persia for official documents in Aramaic. The document now discovered is called a record (v. 2) and is apparently a memorandum concerning the decree rather than the decree itself (which would probably have been written on a clay tablet).

EZRA—NOTE ON 6:3–5 This record is not identical with the decree as recorded in 1:2–4. It makes new stipulations about the building, its location, its size, and its materials. This may be because a copy of the original decree had been found (see note on 6:1–2), and additional instructions may have been added to it for a particular recipient or destination. Moreover, different copies of Cyrus’s original decree may have been made, varying in wording according to the purpose for each copy (the one in 1:2–4 included wording for public proclamation, while this version in 6:3–5 was an official version for royal archives). The size of the temple might be specified in order to limit it, since public funds were being used to pay for it. The absence of a length dimension is odd, and the greater breadth than Solomon’s temple is unexpected (1 Kings 6:2), especially in view of Ezra 3:12.

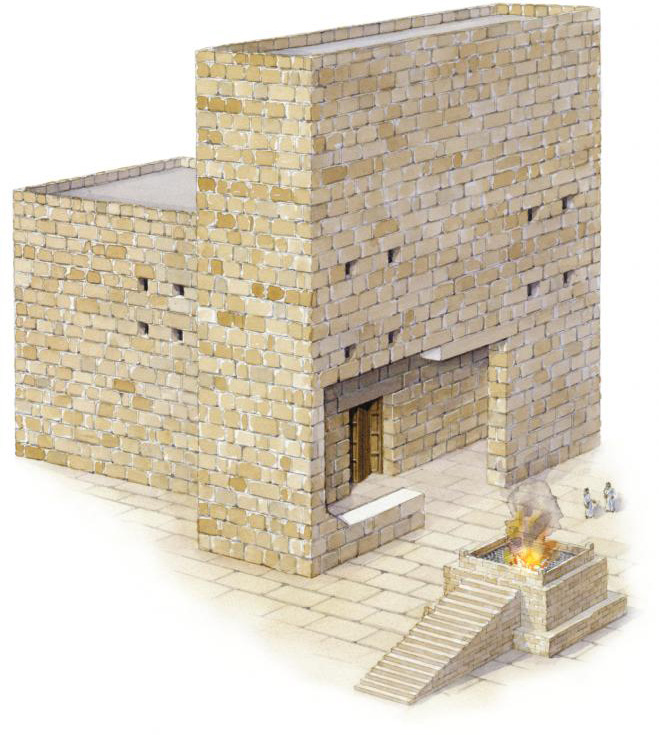

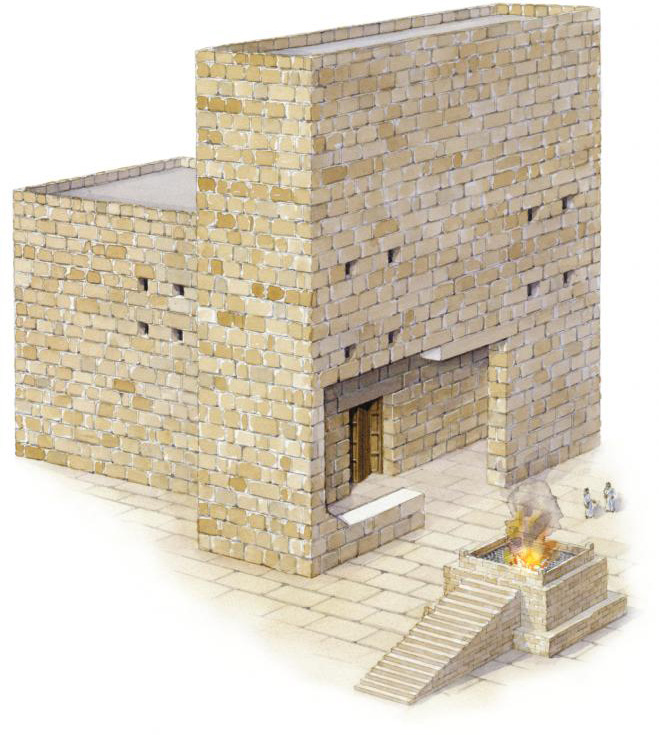

Zerubbabel’s Temple

The rebuilding of Jerusalem’s temple was done in stages (c. 536–516 B.C.). First, the altar was built, so that sacrifices could again be made (Ezra 3:2–3). The second phase was the laying of the foundation of the temple. This elicited mixed reactions from the people. Some rejoiced that the foundation was laid, while others, especially the elder priests, were sad, presumably because the quality of construction was inferior to that of the previous temple. Due to the opposition of the local population and the lack of motivation among the Jews, it took 20 years to complete the construction of the temple building.

The only information given in the biblical record about the architecture of the temple is the dimensions, which were sixty cubits (90 feet/27 m) high and wide (Ezra 6:3). As there is no mention of the length of the building, these dimensions must refer to the facade of the temple, i.e., the Porch.

EZRA—NOTE ON 6:4 The prescription of three layers of great stones and one layer of timber exactly follows the construction of the older temple (1 Kings 6:36; 7:12), which was modeled after temples in other lands (cf. 1 Kings 5:1–12). While the original decree had required people in Babylon to support the cost of the exiles’ project (Ezra 1:4), this record requires that the cost be met from the royal treasury.

EZRA—NOTE ON 6:6–12 Darius now instructs Tattenai and his fellow officials to allow the work to continue.

EZRA—NOTE ON 6:7 Governor of the Jews refers to Zerubbabel (Hag. 1:1). Nothing is known of what became of the first governor, Sheshbazzar.

EZRA—NOTE ON 6:8–10 Darius not only confirms Cyrus’s decree but also provides for costs to be met from taxes raised in Beyond the River itself (v. 8). He also provides for materials for sacrifice in perpetuity (v. 9), with the political stipulation that the Jews pray for the life of the king and his sons (v. 10)—showing that Darius’s generosity was part of his policy to sustain Persian power.

EZRA—NOTE ON 6:11–12 Darius makes in effect a further decree, backed up with a typical threatened sanction (v. 11). The final warning borrows language from the Jews’ own way of speaking about God’s presence in Jerusalem (the God who has caused his name to dwell there, v. 12; cf. Deut. 12:5); Darius strikingly acknowledges the efficacy of the God of Jerusalem in his own place (although, like Cyrus in Ezra 1:3, he might not be claiming that there is only one true God).

EZRA—NOTE ON 6:13–22 Darius’s decree is implemented, the temple is completed and dedicated, and Passover is kept.

EZRA—NOTE ON 6:13 Tattenai and his fellow officials respond quickly to Darius’s decree.

EZRA—NOTE ON 6:14 the elders of the Jews built and prospered. That is, they were successful in their building. Their success came through the prophesying of Haggai the prophet and Zechariah the son of Iddo. This passage emphasizes that God—here represented as speaking through his prophets—is the real influence behind events. The God of Israel has also given a decree that the work should proceed. But the actions of the kings of Persia on the Jews’ behalf, in the decree of Cyrus and Darius and Artaxerxes king of Persia, are also acknowledged. The inclusion here of Artaxerxes, who ruled after the events of this chapter, anticipates his decree in support of Ezra’s mission (7:11–26).

Kings of Persia Mentioned in Ezra–Nehemiah

View this chart online at http://kindle.esvsb.org/c88

| Cyrus |

539–530 B.C. |

| Darius I |

522–486 |

| Xerxes (Ahasuerus) |

485–464 |

| Artaxerxes I |

464–423 |

EZRA—NOTE ON 6:15 The month of Adar (February/March) was the last month of the year, and the dedication of the temple falls fittingly in it, just before the celebrations of the new year that would follow. The sixth year of the reign of Darius was 515 B.C., almost exactly 70 years after the destruction of the first temple (586), thus fulfilling the prophecy of 70 years of exile (one way of reading Jer. 25:11–12; 29:10; see Introduction: Purpose, Occasion, and Background, and note on Jer. 25:11).

EZRA—NOTE ON 6:16–17 the people of Israel. Even though the returned exiles consisted of only three tribes (see note on 1:5), they are taken to represent all 12 tribes, the number of the tribes of Israel (6:17). The other divisions, the priests and the Levites and the laity, are a typical way of describing the whole community in Ezra. with joy. See note on vv. 19–22. The dedication (Hb. hanukkah) of this house (v. 17) follows its completion, and is celebrated with lavish sacrifices, as Solomon’s temple had been (see 1 Kings 8:62–64). (The later Jewish holiday of Hanukkah, however, was based not on this dedication but on the rededication of the temple under the Maccabees in 164 B.C.; see Intertestamental Events Timeline.) The sin offering for all Israel (Ezra 6:17) recalls the sin offering prescribed for the Day of Atonement (Lev. 16:15–16) and is appropriate at this rededication following God’s former judgment on his people. Here again the symbolic unity of Israel is emphasized.

EZRA—NOTE ON 6:18 The priests and Levites are set in their divisions, i.e., according to the roster for duty in the temple, as King David had once done (1 Chronicles 23–27). The phrase as it is written in the Book of Moses applies to the general assignment of the priests and Levites to their respective duties (Numbers 3; 8) rather than to the system of divisions outlined in Chronicles.

EZRA—NOTE ON 6:19–22 (The narrative returns to Hebrew in v. 19; see note on 4:7–8.) The Passover is kept on its appointed date, followed immediately by the Feast of Unleavened Bread (6:22), which lasts for seven days (Lev. 23:5–6). The priests and Levites had purified themselves and were clean (Ezra 6:20); i.e., they had made the necessary ritual preparations. The participants are the people of Israel, the returned exiles again representing the whole, and the people of the land who had joined them (see note on v. 21). the LORD had made them joyful (v. 22). He had fulfilled his prophecies and answered his people’s prayers. There is spontaneous joy when God’s people see evidence that he is working in the world. The reference to the king of Assyria (v. 22) at first seems odd because kings of Persia have supported the Jews in Ezra. The reference here, however, is based on the continuity of the various empires. The king of Persia now ruled over the territorial empire of the Assyrians, and thus he could be called “king of Assyria” (cf. Herodotus, History 1.178, in a discussion of Cyrus’s conquests, where Babylon is called the strongest city “in Assyria”). This wording emphasizes the turn in fortunes, under God, since the Assyrians had been used as God’s agent of punishment centuries before (Neh. 9:32; Isa. 10:5–11).

EZRA—NOTE ON 6:21 Remarkably, the returning Jews are joined by every one who had … separated himself from the uncleanness of the peoples of the land to worship the LORD. This shows that the community was essentially religious, rather than based merely on physical birth and lineage, and that outsiders could convert into it.

EZRA—NOTE ON 7:1–8:36 Ezra the Priest Comes to Jerusalem to Establish the Law of Moses. The narrative now skips to a time 57 years later (see note on 7:1–7), when Ezra the scribe is commissioned by King Artaxerxes to establish the Torah of Moses in the Jerusalem community. This section recounts Ezra’s commission, his journey, and his companions.

EZRA—NOTE ON 7:1–28 King Artaxerxes Gives Ezra Authority to Establish the Mosaic Law. This section describes how Artaxerxes gave Ezra the authority to establish the Mosaic law in the province of Yehud (i.e., Judah), to appoint magistrates to administer that law, and to provide for the further adornment of the temple.

EZRA—NOTE ON 7:1–7 Ezra is introduced first as a priest, his lineage going back to Aaron the chief priest (v. 5), the brother of Moses (cf. Ex. 4:14; 28:1–2). He comes in the reign of Artaxerxes (Ezra 7:1), in the seventh year (v. 7), i.e., 458 B.C.—57 years after the temple dedication.

EZRA—NOTE ON 7:6–7 Ezra is also a scribe skilled in the Law of Moses. No doubt God raised up a scribe with expert knowledge of the law because, after 70 years of exile, the people badly need instruction in how to live according to the Law of Moses. Ezra has apparently asked the king for permission and resources to go to Jerusalem (v. 7). Artaxerxes is supportive, again at the prompting of God, who gives favor to Ezra: and the king granted him all that he asked, for the hand of the LORD his God was on him (see notes on 1:1; 6:14). He comes with a new wave of migrants, priests, laity, and Levites, including singers and gatekeepers (7:7; see note on 2:36–58). The return of exiles did not happen all at once.

The Hand of God in Ezra and Nehemiah

View this chart online at http://kindle.esvsb.org/c89

|

Ezra 7:6

|

The king granted Ezra all that he asked |

for the hand of the Lord his God was on him |

|

Ezra 7:9

|

Ezra began to go up from Babylon and came to Jerusalem |

for the good hand of his God was on him |

|

Ezra 7:28

|

Ezra took courage before the king and his men, and gathered leading men from Israel to go with him |

for the hand of the Lord his God was on him |

|

Ezra 8:18

|

Ezra is sent ministers for the house of God |

by the good hand of their God on them |

|

Ezra 8:22

|

On all who seek God |

the hand of their God is for good |

|

Ezra 8:31

|

God delivered them from the hand of the enemy and from ambushes by the way |

[for] the hand of their God was on them |

|

Neh. 2:8

|

King Artaxerxes granted what Nehemiah asked |

for the good hand of his God was upon him |

EZRA—NOTE ON 7:9 the first month … the fifth month. The journey from Babylon to Jerusalem had taken nearly four months. It was about 900 miles (1,448 km). This was a slow pace, probably because the caravan included children and elderly people. (And 8:31 indicates that there was an 11-day delay before departure.)

EZRA—NOTE ON 7:10 Ezra’s mission was to teach God’s statutes and rules, i.e., the extensive laws of God given to Moses in addition to the Ten Commandments (see Deut. 4:1; 5:1), under the general rubric of the Law (Hb. torah) of the LORD. These are contained throughout Exodus to Deuteronomy, especially in Exodus 20–23, Leviticus, and Deuteronomy 12–26. Readers are told nothing of how this mission came to be in Ezra’s heart. The terms study, do, and teach (indeed, the whole account of Ezra 7–10) present Ezra as the ideal priest in Israel, whose task is to lead God’s people in worship and holiness of life (see Deut. 33:10): his ministry stems from a faithful life (cf. Mal. 2:1–9; 1 Tim. 4:6–16).

EZRA—NOTE ON 7:11–28 This section tells how Artaxerxes supports Ezra by commissioning him and providing further for the temple. The text of the letter (vv. 12–26) is in Aramaic (see note on 4:7–8).

EZRA—NOTE ON 7:11 The king’s decree is in the form of a letter addressed to Ezra, which could be used to enforce the king’s command.

EZRA—NOTE ON 7:12 The title king of kings was used by kings of Persia and expresses their sovereignty over many subject peoples. Ezra is called the scribe of the Law of the God of heaven, which possibly refers to a kind of responsibility for Jewish affairs that he already held in Babylon.

EZRA—NOTE ON 7:13 The decree echoes that of Cyrus in authorizing any Jews who wish to go to Jerusalem (see 1:3).

EZRA—NOTE ON 7:14 The commission to make inquiries about Judah and Jerusalem according to the Law of your God no doubt reflects Ezra’s own priority, and perhaps his belief that the law is not being properly kept.

EZRA—NOTE ON 7:15–20 Artaxerxes turns to the needs of the temple, perhaps showing his own perception of Ezra’s task, in accordance with Cyrus’s original decree in 538 B.C., 80 years earlier (see note on 1:1).

EZRA—NOTE ON 7:15–16 The king and his counselors give money for the temple and permit Ezra to gather further resources in the whole province of Babylonia, perhaps from non-Jews as well as Jews.

EZRA—NOTE ON 7:17–18 The provision specifies the temple worship but also leaves extensive discretion to Ezra in his expenditure.

EZRA—NOTE ON 7:19–20 vessels … for the service of the house of your God. Artaxerxes adds these to the temple treasures originally returned by Cyrus, apparently as his own gift, and, finally, allows Ezra to take whatever he needs from the king’s treasury (v. 20), i.e., from public funds.

EZRA—NOTE ON 7:21 The decree now specifically addresses the royal treasury officials in Beyond the River, compelling them to make provision for Ezra up to specified limits.

EZRA—NOTE ON 7:22 The talent was 75 pounds (34 kg), and the amount of silver specified has been estimated at between a quarter and a third of all the annual taxation raised in “Beyond the River.” The wheat, wine, and oil would have been used for cereal offerings, for drink offerings, and for the lamp kept lit in the temple (Ex. 27:20; 29:2). With a “cor” at 6 bushels (220 liters) and a “bath” at 6 gallons (23 liters), the quantities would have supplied the temple’s needs for perhaps two years. Salt, supplied without limit, was for preservation and seasoning (Ex. 30:35; Lev. 2:13).

EZRA—NOTE ON 7:23 In making these provisions (v. 22), the king may actually intend to ward off the wrath of God against the king and his sons, i.e., his own kingdom, present and future (see also 6:10).

EZRA—NOTE ON 7:27 Blessed be the LORD … who put such a thing as this into the heart of the king. See note on 1:1. to beautify the house of the LORD. The author uses the same terms as Isa. 60:7 (see note), indicating that he sees this event as fulfillment of Isaiah’s prophecy.

EZRA—NOTE ON 8:1–36 Ezra Journeys to Jerusalem with a New Wave of Returnees, Bearing Royal Gifts for the Temple. This section gives a more extended account of Ezra’s return to Jerusalem. Readers learn of those who returned with Ezra (vv. 1–14), of how he recruited additional priests (vv. 15–20), of their prayer for the journey (vv. 21–23), and of Ezra’s provision for the temple (vv. 24–36).

EZRA—NOTE ON 8:1–14 The party that returned with Ezra was a considerable addition to the community in Judah. It is numbered here according to the heads of their fathers’ houses, i.e., heads of families (v. 1). Their genealogy refers to their formal registration in the list of those returning (as in v. 3, registered, which translates the same Hb. word). There are two priestly divisions, namely, Phinehas (v. 2; son of Eleazar, Num. 25:7) and Ithamar (Ezra 8:2; see Ex. 28:1). These were the remaining sons of Aaron following the judgment on Nadab and Abihu (Lev. 10:1–7). Ezra himself was of the line of Phinehas (Ezra 7:5). Daniel (8:2) is otherwise unknown, and is not the Daniel who was carried off to Babylon in 605 B.C. (see Dan. 1:1, 6; also note on Dan. 1:1–2), for this is now 458 (see note on Ezra 7:1–7). A third division is a line of David (8:2; for Hattush, see 1 Chron. 3:22). Ezra’s party therefore aims to replenish the priesthood, and perhaps also to renew the claims of the Davidic house to rule in Judah.

EZRA—NOTE ON 8:15 The party camps outside Babylon at the river that runs to Ahava, no doubt one of the network of canals extending from the Euphrates. Ezra discovers that, though he had priests with him, there were none of the sons of Levi, i.e., the lower order of clergy, the Levites (see 2:40).

EZRA—NOTE ON 8:17 Nothing is known of Iddo or of Casiphia, to which Ezra’s delegation (v. 16) is sent. But it was apparently a place where Levites and temple servants (see 2:43–54; 1 Chron. 9:2) might be expected to be found, and perhaps where they continued to be trained for the day when there would be a temple again in Jerusalem.

EZRA—NOTE ON 8:18–19 Mahli and Merari belong to the same Levitical family, Merari being a son of Levi (Num. 3:33).

EZRA—NOTE ON 8:20 The number of those who respond to Ezra’s call is small, but symbolically important for the nation’s future.

EZRA—NOTE ON 8:21 a fast. The custom of fasting grew in importance in the exile as part of a spirit of penitence (see Neh. 9:1; Est. 4:3). humble ourselves. This implied a deliberate penitential attitude, as in the Day of Atonement (Lev. 16:31). Yet the prayer (Ezra 8:22–23) chiefly expresses the people’s trust in God as they sought to demonstrate his reality to the Persian king. The king’s ongoing support, they know, may depend on his belief in the reality and power of the God of Israel.

EZRA—NOTE ON 8:22 On the power of his wrath, see 6:10 and 7:23. Contrast Ezra’s policy in 8:22 with Nehemiah’s (Neh. 2:9).

EZRA—NOTE ON 8:23 and he listened to our entreaty. God’s oversight of the events of history is the background against which this entire book is written (cf. v. 31; also note on 1:1).

EZRA—NOTE ON 8:24–36 Ezra entrusts the offerings that he has gathered for the temple to the priests who are with him (see 7:15–16, 22).

EZRA—NOTE ON 8:26 The amounts of silver and gold are extraordinarily large, the silver weighing around 25 tons (22 metric tons) and the gold 3.75 tons (3.4 metric tons).

EZRA—NOTE ON 8:28 The priests themselves are holy to the LORD (Ex. 29:1), namely, set aside for his service, and the precious metals and vessels have been donated into the holy sphere, and so they are also holy (see Ex. 30:26–29 for consecrated utensils).

EZRA—NOTE ON 8:29–30 The holy vessels are rightly entrusted to the priests; they remain in priestly possession until handed over to their counterparts in the temple itself.

EZRA—NOTE ON 8:31 The group sets out on the twelfth day of the first month (Nisan, March/April); the plan to leave on the first day (7:9) had been delayed by the need to send for more Levites. he delivered us from the hand of the enemy. Whether there were actual attacks on the group is not said, but God’s protection on the journey makes this departure from Babylon resemble the ancient exodus of Israel from Egypt (e.g., Ex. 17:8–13; cf. notes on Ezra 1:1; 8:21; 8:22; 8:23).

EZRA—NOTE ON 8:32 We came to Jerusalem. This was on the first day of the fifth month (Ab, July/August; cf. 7:9), so the journey of roughly 900 miles (1,448 km) lasted nearly four months (see note on 7:9).

EZRA—NOTE ON 8:33–34 After a three-day rest, the treasures for the temple are handed over to the priests as planned (vv. 28–30).

EZRA—NOTE ON 8:35 For these exiles it is a first chance to see and worship at the rebuilt temple, and their sacrifices resemble those made at its first dedication (see 6:16–17). twelve bulls. See note on 6:16–17.

EZRA—NOTE ON 8:36 to the king’s satraps and to the governors. A “satrap” was a governor of a “satrapy” (province), such as Beyond the River. The double expression here (satraps, governors) is a loose way of referring to the governing officials in general, who continue to have good relations with the community in Judah.

EZRA—NOTE ON 9:1–10:44 Ezra Discovers and Confronts the Problem of Intermarriage. Ezra discovers that the Jewish community has mixed with idolatrous non-Jewish groups in religion and in marriage, and he leads the community in an act of repentance and in a systematic separation from the foreign women and their children.

EZRA—NOTE ON 9:1–15 Ezra Discovers the Problem of Marriage to Idolaters, and Prays. Ezra hears the news of the marriages to adherents of other religions, and he prays for the people.

EZRA—NOTE ON 9:1–2 For the peoples of the lands, see note on 3:3. They are further identified as idolatrous nations, for the Canaanites, the Hittites, the Perizzites, the Jebusites, … and the Amorites are among the seven nations that Israel was commanded by Moses to drive out of the land (see Deut. 7:1–5). The Ammonites and Moabites were nations east of the river Jordan, outside the Promised Land, who were regarded as especially hostile to Israel (Deut. 23:3–4). And in Lev. 18:3, Egypt is regarded as morally equal to Canaan. The peoples of the land who keep themselves distinct from the returned temple-community are thus portrayed as the same in principle and in character as these ancient enemies. These are specifically wives (Ezra 9:2) of foreign nations who had not abandoned their worship of other gods, for 6:21 makes it clear that such people could join the people of Israel if they were willing to follow the Lord God alone (see note on 6:21). Their abominations (9:1) refers to these peoples’ worship of other gods and the associated practices that Yahweh, God of Israel, regarded as particularly wicked (Deut. 12:31). It is implied that the foreigners’ religions in Ezra’s day were just as idolatrous as in ancient times, and thus it is clear that the issue is not ethnic purity (cf. Ezra 6:21). Intermarriage with the indigenous population carried the danger of religious apostasy, and therefore was expressly forbidden by the law (Deut. 7:3). The holy race (Ezra 9:2) is literally “holy seed/offspring” and alludes to the “offspring” of Abraham, who bore the ancient promise of covenant and land (Gen. 12:1–3; 15:5; 17:7–8). The “holy seed” was also seen in prophecy as the surviving remnant that would be brought to life again after the terrible judgment of the exile (Isa. 6:13). The involvement of all classes of the community—the priests, the Levites, and the people of Israel (Ezra 9:1), as well as the officials and chief men (v. 2)—shows that the problem included all the people. The term faithlessness (Hb. ma‘al, v. 2) is an extremely strong expression for abandonment of the faith, especially by leaders (see 1 Chron. 10:13, where it is translated “breach of faith”).

EZRA—NOTE ON 9:3 Ezra expresses his deep dismay by performing ritual acts of mourning. His severe reaction results from the fact that the “holy race” has compromised its newly won salvation by returning to the sins that had brought judgment in the first place.

EZRA—NOTE ON 9:4 trembled at the words of the God of Israel. An expression for pious eagerness to obey God, and respect for his holiness (cf. Isa. 66:2).

EZRA—NOTE ON 9:6–7 Ezra confesses sin on behalf of the covenant community, beginning with the historic sins of Israel that had led to the Babylonian exile.

EZRA—NOTE ON 9:6 our iniquities … our guilt. These two strong terms (Hb. ‘awon, “iniquity,” and ’ashmah, “guilt”) are each repeated twice here. Ezra recognizes the justice of the punishment of exile.

EZRA—NOTE ON 9:7 the days of our fathers. That is, the time before the exile (see Zech. 1:4). The terms sword, captivity, plundering, and shame sum up the disasters experienced by the people because they failed to keep the covenant, and bring to mind the covenantal consequences for disobedience noted in Lev. 26:14–39 and Deut. 28:15–68 (cf. 2 Kings 17:20; Jer. 24:9–10).

EZRA—NOTE ON 9:8 for a brief moment favor. Ezra refers to the time since Cyrus’s edict. This was nearly a century, but was short in the sweep of Israel’s history. The idea of a remnant could be attached to notions of God’s judgment, for it can refer to a small remnant left afterward, or to the subject of renewed punishment (see Isa. 6:13a; 10:22; Jer. 24:8). But prophets also spoke positively of a remnant of Israel who would repent and be restored after the purifying judgment of exile, and who would continue to bear the identity and destiny of Israel (see Isa. 10:20–21; Jer. 24:4–7 also has the idea, though not the term). Ezra applies the term to the returned exiles (as does Nehemiah [Neh. 1:2]). his holy place. This refers narrowly to the temple and more broadly to the land of Judah.

EZRA—NOTE ON 9:9 we are slaves … in our slavery. The idea that the exiles remain slaves is unexpected after their restoration to the land, but acknowledges that they are still under the foreign authority of Persia (see Neh. 9:36–37). Therefore, the favorable view of Persia thus far does not prevent the exiles’ aspiration to complete freedom. Even so, though they are under this foreign authority, God has shown steadfast love, the special quality of faithful love that characterizes his attachment to Israel in the covenant, and that he expects in return (Hos. 6:6).

EZRA—NOTE ON 9:10–12 Ezra alludes to Deut. 7:1–5 and the present community’s breach of its prohibition of intermarriage.

EZRA—NOTE ON 9:11 impure … impurity … uncleanness. Ezra uses language from the “holiness” vocabulary to stress the incompatibility of the indigenous people’s way of life and worship with that mandated by the holy God of Israel.

EZRA—NOTE ON 9:15 Ezra knows that God is both just and merciful. (For God as “just,” or “righteous,” see also Deut. 32:4; Ps. 119:137.) The very existence of the postexilic remnant proves his mercy; yet equally God would be justified in bringing renewed judgment on the sinful people. The prayer serves as a petition for mercy, and it prompts Ezra and his close associates to turn the people from their sin.

EZRA—NOTE ON 10:1–17 The People Agree to Dissolve the Marriages. Ezra prays, and the people confess their sin (vv. 1–2). They agree to do God’s will (vv. 3–5). Ezra seeks an answer (vv. 6–8), which is for them to separate from their wives (vv. 9–12), and the people obey (vv. 13–17).

EZRA—NOTE ON 10:1 Ezra’s own report of the events (7:27–9:15) now gives way to a different narrative voice, though the account continues without a break. a very great assembly. Under God, Ezra’s public prayer and demonstration of grief bring a large number of people to repentance, as shown by the statement that they wept bitterly. The term “assembly” is used for a formal gathering of Israel as a religious community.

EZRA—NOTE ON 10:2 Shecaniah speaks for the whole gathering, perhaps by prearrangement. Jehiel. See also v. 26; Shecaniah’s own father may have had a mixed marriage. broken faith. See note on 9:1–2 concerning “faithlessness.” The word translated married is not the usual one, but means literally “we have given a home”; Shecaniah’s words may imply that these illicit relationships were not marriages in the full sense.

EZRA—NOTE ON 10:3 Shecaniah’s belief that “there is hope for Israel” (v. 2) is dependent on making a covenant with God, meaning in this instance a solemn and binding promise to put away the foreign wives and their children. As with the term for “marriage,” this is not the usual expression for “divorce,” and may also imply that these were not proper marriages. The word means simply “bring out.” In effect, this meant excommunicating them from the community of returned exiles. The text does not make clear any other details concerning matters of ongoing support and protection for these wives and their children (cf. v. 44), or concerning what happened to them (but see note on vv. 18–44). Because this represents a different situation in a different context as compared to 1 Cor. 7:12–14 (where Paul tells Christians not to divorce their unbelieving spouses), and because this example was recorded here in Ezra for descriptive rather than normative reasons, there would be no justification for anyone to take similar actions today. In Ezra’s context, members of God’s people had defied God’s law in taking these wives, while Paul gives his instructions to people who probably converted after their marriage. the counsel of my lord (i.e., Ezra). Ezra may have already outlined a plan for taking care of the foreign wives and their children, even though it is not recorded here. according to the Law. That is, Deut. 7:1–5 (see note on Ezra 9:1–2). those who tremble. See note on 9:4.

EZRA—NOTE ON 10:4 be strong and do it. This is like the charge to Joshua at the first entry of Israel into the land (Josh. 1:6–7), and relates both to overcoming enemies and to keeping the law.

EZRA—NOTE ON 10:5 The oath is in effect the same as the covenant (v. 3). All three main sections of the community take this oath.

EZRA—NOTE ON 10:6 Jehohanan the son of Eliashib. Both names are common and appear in several lists in Ezra and Nehemiah (see Ezra 10:24, 27, 36; Neh. 12:10, 13). It is not always possible to know whether the same name refers to the same person. This family evidently had a caretaking role in the temple (see Neh. 13:4).

EZRA—NOTE ON 10:7 assemble at Jerusalem. Such assemblies normally occurred during the three regular pilgrimage feasts (Passover, Pentecost, Tabernacles); this was a special gathering, since the survival of the community was at stake.

EZRA—NOTE ON 10:8 banned from the congregation. Anyone who refused to participate in the plan to renounce the foreign wives and children would share their excommunication.

EZRA—NOTE ON 10:9 The ninth month, Chislev, is roughly December, the time of the so-called early rains. The people are trembling partly for fear of God (as in 9:4), and partly because they are cold and wet in the heavy rain.

EZRA—NOTE ON 10:10 The terms of Ezra’s accusation have appeared already in 9:1–2, 4, 6–7; 10:2. increased the guilt of Israel. The return from exile had signified that all of Israel’s past sins had been forgiven (Isa. 40:1–2). Ezra now points to renewed sin, beyond that which had previously been forgiven, and thus the possibility of the renewed wrath of God.

EZRA—NOTE ON 10:11 Make confession is based on Hebrew words that could also be translated in other contexts as “give thanks or praise” (Hb. natan + todah; cf. Josh. 7:19 and esv footnote). Some overlap of these meanings is not surprising because rightful confession is itself a kind of worship of God.

EZRA—NOTE ON 10:12–15 The people as a whole respond with a solemn admission of their guilt and with resolution to act to address the problem, as in the making of a covenant (see also Ex. 19:8; 24:3, 7). They then propose a practical means of conducting the procedure.

EZRA—NOTE ON 10:14 wrath of our God. See note on v. 10.

EZRA—NOTE ON 10:15 opposed this. This probably means that these men opposed the entire resolution to put away the foreign wives. But the verse contains some ambiguity in Hebrew, and some interpreters think these men opposed the proposed means of proceeding because they wished to act more swiftly.

EZRA—NOTE ON 10:16–17 This summary account of the proceedings shows that it was undertaken by duly appointed authorities in the community, and thus it was not merely Ezra’s doing. examine the matter (v. 16). The need for rigorous inquiry was an established part of the duties of judges (see Deut. 17:4). The whole inquiry took three months.

EZRA—NOTE ON 10:18–44 List of Those Who Were Implicated. The list of around a hundred names is surprisingly short, and may suggest a more limited problem than one might have expected. Either the list has been abbreviated or in fact those involved were few. In the latter case, the severe reaction of Ezra and the community recognizes the extreme danger that the whole community could face by the actions of only a few in this fundamental area of its covenantal life (compare the notion of purging “the evil from your midst,” Deut. 17:7). The list is divided, typically for Ezra, into priests (Ezra 10:18), Levites (v. 23), and Israel (vv. 25–43). The guilt offering (v. 19) was presumably to be brought by each person in the list. The extensive inquiry must have considered each case separately. In some cases, a wife and her children might actually have adopted the religion of Israel, as anticipated and permitted in 6:21. The inquiry might have come down to an examination of such people’s beliefs. Those who were turned away probably returned to their non-Jewish families.