Study Notes for Daniel

DANIEL—NOTE ON 1:1–6:28 Daniel and the Three Friends at the Babylonian Court. The Hebrew exiles live faithfully to the Lord while serving in the court of Nebuchadnezzar and his successors, from 605 B.C. down to the fall of the Babylonian Empire (539) and into the early years of Persian rule; their service brings blessing to the Gentiles.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 1:1–21 Prologue. Daniel describes how he and his three friends were taken into exile (vv. 1–7), remained undefiled (vv. 8–16), and were promoted and preserved (vv. 17–21).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 1:1–7 Daniel and His Friends Taken into Exile. Here it is explained how the Hebrew youths came to be trainees for service in the Babylonian court.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 1:1–2 In the third year of the reign of Jehoiakim (605 B.C.), Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon came to Jerusalem and took Daniel and other promising young people to Babylon to be trained in Babylonian culture and literature. This deportation was the beginning of what came to be known as the Babylonian exile, which was the result of the Lord’s judgment on his people. In Lev. 26:33, 39 the Lord threatened his people with exile if they were unfaithful to the terms of the covenant established at Mount Sinai (see also Deut. 4:27; 28:64). After a lengthy history of disobedience, this threat was carried out in several stages, culminating in the destruction of Jerusalem and the burning of the temple in 586 B.C. The final destruction and exile were foreshadowed by this earlier exile in which vessels of the house of God were taken into captivity along with some of his people. Daniel calls it the “third year of the reign of Jehoiakim,” apparently using the Babylonian system for counting the length of a reign, while Jer. 25:1 calls it “the fourth year,” using the Jewish system. (Reigns could be counted from the beginning of the new year preceding a king’s ascension, or from the actual date of ascension, or from the beginning of the new year following his ascension; the third system was used in Babylon.)

DANIEL—NOTE ON 1:3–4 Some of the royal family and nobility were also exiled. Like the temple vessels and sacrifices, they had to be without blemish. Their exile was a fulfillment of Isaiah’s prophecy to King Hezekiah in 2 Kings 20 and Isaiah 39, a century earlier. Hezekiah had shown the representatives of Babylon around his treasuries, hoping to win a political partner against the Assyrians. This failure to trust in the Lord was met with a prophecy that the treasures he had shown the Babylonians and some of his own descendants would be carried off to Babylon.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 1:5–7 Nebuchadnezzar sought to assimilate the exiles into Babylonian culture by obliterating their religious and cultural identity and creating dependence upon the royal court. For this reason, the exiles were given names linked with Babylonian deities in place of Israelite names linked with their God. Daniel (“God is my Judge”), Hananiah (“Yahweh is gracious”), Mishael (“Who is what God is?”), and Azariah (“Yahweh is a helper”) became names that invoked the help of the Babylonian gods Marduk, Bel, and Nebo: Belteshazzar (“O Lady [wife of the god Bel], protect the king!”), Shadrach (“I am very fearful [of God]” or “command of Aku [the moon god]”), Meshach (“I am of little account” or “Who is like Aku?”), and Abednego (“servant of the shining one [Nebo]”). They were schooled in the language and mythological literature of the Babylonians, and their food was assigned from the king’s table, reminding them constantly of the source of their daily bread.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 1:8–16 Daniel and His Friends Remain Undefiled. Daniel and his three friends resisted the attempted assimilation. They retained their original names (see v. 11) and resolved not to defile themselves with the king’s food and drink (v. 8). Many have thought that the four men’s resolve came from their intent to eat only ceremonially clean food, not any “unclean” food as specified in Lev. 11:1–47 and Deut. 14:3–20—much as a group of Jewish priests later did in Rome, eating only figs and nuts (see Josephus, Life of Josephus 14; cf. Rom. 14:2). That may be part of the explanation, for the Babylonians would have eaten such things as pork, which was unclean for Jews. But wine (Dan. 1:8) would not have been prohibited by any law in Jewish Scripture, so that cannot be the entire explanation (unless the young men feared that somehow the wine had been polluted through failure to grow the grapes according to the rule of Lev. 19:23–25; cf. Deut. 20:6). Another view is that they feared the meat and wine would have been first offered to Babylonian idols. Again, this may have provided part of the reason for their reluctance to partake of the Babylonian food, but the vegetables and grains would probably also have been offered to idols, so that does not seem to be the most persuasive explanation. A third view, that they were following a vegetarian diet for health reasons, is unhelpful, because no OT laws would have taught them that (modern) idea. A fourth view combines elements of the first two, and seems the best explanation: Daniel and his friends avoided the luxurious diet of the king’s table as a way of protecting themselves from being ensnared by the temptations of the Babylonian culture. They used their distinctive diet as a way of retaining their distinctive identity as Jewish exiles and avoiding complete assimilation into Babylonian culture (which was the king’s goal with these conquered subjects). With this restricted diet they continually reminded themselves, in this time of testing, that they were the people of God in a foreign land and that they were dependent for their food, indeed for their very lives, upon God, their Creator, not King Nebuchadnezzar. (It is possible that Daniel later came to accept some of the Babylonian food; see Dan. 10:3.) The Lord gave Daniel favor (1:9) with his captors, an answer to Solomon’s prayer for the exiles (1 Kings 8:50), and the steward honored their request for a special diet. At the end of a trial period, Daniel and his friends looked fitter (fatter in flesh; Dan. 1:15) than those who had consumed a high-calorie diet. This confirmed that God’s favor was upon them.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 1:17–21 Daniel and His Friends Promoted and Preserved. God also gave to all four of them exceptional knowledge and understanding of the Babylonian literature and wisdom, and to Daniel the ability to discern all visions and dreams (v. 17). God’s favor enabled them to answer all of Nebuchadnezzar’s questions, so that he found them ten times better than all of his pagan advisers (v. 20). God placed them in a unique position where they could be a blessing to their captors and build up the society in which they found themselves (see Jer. 29:5–7), while at the same time enabling them to remain true to him amid extraordinary pressures.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 1:21 until the first year of King Cyrus. That is, 539 B.C., when Cyrus conquered Babylon. God’s faithfulness proved sufficient for Daniel throughout the 70 years of his exile. Babylonian kings came and went, and the Babylonians were replaced as the ruling world power by the Medo-Persian King Cyrus, yet God sustained his faithful servant (cf. 10:1).

Rulers During the Time of Daniel

View this chart online at http://kindle.esvsb.org/c113

| Babylon |

Nebuchadnezzar |

605–562 B.C. |

| Nabonidus |

556–539 |

| Co-regent Belshazzar |

550–539 |

| Persia |

Cyrus |

539–530 |

| Darius I |

522–486 |

DANIEL—NOTE ON 2:1–49 Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream of a Great Statue. Daniel’s God shows himself superior by revealing to Daniel both the content and the interpretation of Nebuchadnezzar’s dream.

Explicit References to Dates in Daniel

View this chart online at http://kindle.esvsb.org/c112

| Babylon |

Nebuchadnezzar’s 1st year |

605 B.C. |

ch. 1

|

| Nebuchadnezzar’s 2nd year |

604 |

ch. 2

|

| Nebuchadnezzar’s reign |

605–562 |

chs. 3–4

|

| Belshazzar’s 1st year |

550 |

ch. 7

|

| Belshazzar’s 3rd year |

548 |

ch. 8

|

| Belshazzar’s last year |

539 |

ch. 5

|

| Persia |

Cyrus’s 3rd year |

536 |

chs. 10–12

|

| Darius’s 1st year |

522 |

ch. 9

|

| Darius’s reign |

522–486 |

ch. 6

|

DANIEL—NOTE ON 2:1–13 The Dream and Nebuchadnezzar’s Threat. Nebuchadnezzar expects his interpreters to also tell him the very content of his dream (perhaps to prove that they are genuinely qualified to interpret it).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 2:1 In the ancient world, dreams were thought to be shadows of future events. A king’s dreams had significance for the nation as a whole, and the interpretation was important so that the king might take steps to be ready for the events the dream anticipated, or even to counteract them. From the timing in the second year of the reign of Nebuchadnezzar, it is possible that the author implies that Daniel and his friends had not yet finished their three-year program (1:5). However, it may be better to use Babylonian conventions to count the years of a reign, such that the young men were taken and began their training in Nebuchadnezzar’s accession year, and had their second and third years of training during what the Babylonians called the first and second years of Nebuchadnezzar’s reign (see note on 1:1–2). In that case, “the second year of the reign of Nebuchadnezzar” would be 603–602 B.C.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 2:2 Nebuchadnezzar had a staff of specialists in dream interpretation: the magicians, the enchanters, the sorcerers, and the Chaldeans. The name “Chaldeans” initially referred to a part of the Babylonian Empire, but it developed into a descriptive term for a special group, known for their expertise in magic lore and interpreting dreams.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 2:4 From this point until the end of ch. 7, the text switches from Hebrew into Aramaic, the court language of its Babylonian setting. Perhaps the change indicates that these chapters address matters of universal significance rather than those of more specifically Israelite concern.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 2:5–6 Contrary to normal procedure, the king made the extraordinary demand that his interpreters recount the dream itself as well as its interpretation. If the interpreters succeeded, they would be given great rewards. If they failed, they would be executed and their houses would be destroyed.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 2:11 These men consider the king’s demand unreasonable because no human being could know another person’s dream unless it was revealed by the gods, whose dwelling is not with flesh. Their own words reveal the power of Israel’s God, who does exactly what they say is impossible. Israel’s God is not only the high and holy God whose glory fills the heavens, but also the God who dwells with those of a humble and contrite spirit (Isa. 57:15).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 2:12 Nebuchadnezzar’s decree of death affected all the wise men, a wider group that would have also included Daniel and his friends.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 2:14–24 Daniel’s Response and Prayer. Daniel shows the right response: he leads his friends in praying to the true God for insight.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 2:15–16 With remarkable faith, Daniel requested from Arioch an appointment with the king to reveal the dream and its interpretation even before God had revealed the dream to Daniel.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 2:19 Unlike the gods of the Babylonian diviners, Daniel’s God was able and willing to reveal such a mystery to his servants (see Isa. 44:7–8; Amos 3:7).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 2:23 Daniel gathered his companions to pray for the revelation of the mystery (vv. 17–18). When God answered his prayer, Daniel praised and thanked God for his wisdom and might before he went to see King Nebuchadnezzar.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 2:25–45 Daniel Interprets the Dream. In successfully meeting the king’s demands, Daniel makes sure that the God of heaven gets the credit.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 2:25–28 Arioch was eager to claim the credit for finding an interpreter for the king’s dream. Daniel, however, was careful to ascribe to God all of the credit for revealing the mystery. Daniel was able to interpret it not because of his own wisdom but only because there is a God in heaven who reveals mysteries. Daniel’s statement contrasts God’s ability with the inability of any pagan wise men, enchanters, magicians, or astrologers to know the “mysteries” of what the king dreamed and what it predicted.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 2:30 God made known the interpretation of the dream so that Nebuchadnezzar would know this great God controlled future events, and so that he would be aware of what was coming.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 2:37–38 According to Daniel’s interpretation, the head of gold was Nebuchadnezzar. God gave him great dominion, power, and glory—reminiscent of that granted to Adam, with dominion over not only human beings but also the birds of the air and the beasts of the field. The nation had become a vast empire, and Nebuchadnezzar ruled ruthlessly. Babylon itself was an amazing achievement, with its hanging gardens (one of the famed Seven Wonders of the ancient world), many temples, and a bridge crossing the Euphrates River (see plan). Thus the head of gold is a fitting description.

The Traditional View of Daniel’s Visions

View this chart online at http://kindle.esvsb.org/c114

| |

Babylonian Empire (625–539 B.C.) |

Medo–Persian Empire (539–331 B.C.) |

Greek Empire (331–63 B.C.) |

Roman Empire (63 B.C.–A.D. 476) |

Future Events |

| Vision of Statue (ch. 2) |

head of gold (vv. 36–38) |

chest and arms of silver (vv. 32, 39) |

middle and thighs of bronze (vv. 32, 39) |

legs of iron; feet of iron and clay (vv. 33, 40–43) |

messianic kingdom stone (vv. 44–45) |

| Vision of Tree (ch. 4) |

Nebuchadnezzar humbled (vv. 19–37) |

|

|

|

|

| Vision of Four Beasts (ch. 7) |

lion with wings of eagle (v. 4) |

bear raised up on one side (v. 5) |

leopard with four wings and four heads (v. 6) |

terrifying beast with iron teeth (v. 7) |

Antichrist little horn uttering great boasts (vv. 8–11) |

| Vision of Ram and Goat (ch. 8) |

|

ram with two horns: one longer than the other (vv. 2–4) |

male goat with one horn: it was broken and four horns came up (vv. 5–8); Antiochus IV (vv. 23–26) |

|

|

DANIEL—NOTE ON 2:39 After Nebuchadnezzar’s time there would be two more kingdoms, each inferior to the previous one in glory and unity, though still strong and powerful (Medo-Persia [539–331 B.C.] and Greece [331–63]).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 2:40 The fourth kingdom (i.e., the Roman Empire) would be strong as iron, yet also an unstable composite of different peoples who would not hold together (see v. 43).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 2:43–44 The Aramaic description of intermarriage as mixing “by the seed of men” (see esv footnote) recalls the prohibition on sowing mixed seed in a field (Lev. 19:19). At that time, God will establish a kingdom that shall never be destroyed, his final kingdom, which will ultimately destroy all other kingdoms. Though it starts small, it will grow to fill the earth and, unlike the earthly kingdoms, it will endure forever (cf. “stone,” “great mountain,” Dan. 2:34–35). It is striking that God gave this dream to Nebuchadnezzar in the seventh century B.C. (about 602; see note on v. 1), for in this dream and in the subsequent visions linked to it in chs. 7 and 8, God predicts in accurate detail the future kingdoms that would arise to dominate world history in the sixth, fourth, and first centuries B.C. Traditional commentators through the history of the church have almost universally identified the four kingdoms as Babylon, Medo-Persia (established by Cyrus in 539 B.C.; specifically named in 8:20), Greece (under Alexander the Great, about 331; specifically named in 8:21), and Rome (the Roman Empire began its rule over Palestine in 63). Those scholars, however, who assume that Daniel’s detailed visions cannot be predictive prophecies, but had to have been written after the events they claim to “predict,” hold that Daniel was written not in the sixth century B.C. but in the second century, in the Maccabean period. Under this scheme the fourth kingdom cannot be the Roman Empire, which did not yet exist at that time. So they propose various other identifications for the kingdoms, such as (1) Babylon, (2) Media, (3) Persia, and (4) Greece; however, Media was never an independent world power after Babylon fell to Cyrus in 539 B.C. (it was also ruled by Cyrus). Another point being made in the dream is that each earthly kingdom has its own glory but also its own end: both have been assigned to it by God. The progression of world history is typically not upward to glory and unity but rather downward to dishonor and disunity. Thus the statue progresses from gold, to silver, to bronze, to iron, and from one head, to a chest and arms, to a belly and thighs, to feet and toes of composite iron and clay. (This list of metals shows a progressive decrease in the value and splendor of the materials but an increase in toughness and endurance. Some commentators understand this to indicate a general decline in the moral quality of the governments and an increase in the amount of time they lasted. See chart below. In contrast, God’s kingdom grows from humble beginnings to ultimate, united glory as a single kingdom that fills the whole earth forever. The stone that will break in pieces all these other four kingdoms is most likely Christ (see Luke 20:18). He is the mystery of the ages, the one in whom God plans to unite all things in his glorious kingdom (Eph. 1:9–10).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 2:46–49 Nebuchadnezzar Promotes Daniel. Nebuchadnezzar recognized and honored Daniel’s God and promoted Daniel and his friends within the Babylonian court, giving them further opportunity to promote the peace and welfare of the city where the Lord had exiled them, as Jeremiah had counseled (cf. Jer. 29:5–7).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 3:1–30 Nebuchadnezzar Builds a Great Statue. Nebuchadnezzar commands all peoples under his rule to worship his golden image, and, though his officials from other nations obey, Daniel’s friends refuse out of loyalty to their God. When God delivers them from the fiery furnace, Nebuchadnezzar’s respect for their God increases. A Babylonian document from the time of Nebuchadnezzar (605–562 B.C.) warns not to harm the statue that had been set up: “Beside my statue as king … I wrote an inscription mentioning my name, … I erected for posterity. May future kings respect the monument, remember the praise of the gods. … He who respects … my royal name, who does not abrogate my statutes and not change my decrees, his throne shall be secure, his life last long, his dynasty shall continue.”

DANIEL—NOTE ON 3:1–7 The Nations Worship Nebuchadnezzar’s Statue. When Nebuchadnezzar has the statue built, representatives of the nations under his rule obey his command to worship it.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 3:1 The image of gold reflects the enormous statue in Nebuchadnezzar’s dream, except it is made entirely of gold, as if Nebuchadnezzar were asserting that there would be no other kingdoms after his. It was sixty cubits (90 feet/27 m) high and six cubits (9 feet/2.7 m) wide. Its location on a plain in Babylon recalls the location of the Tower of Babel (also on a plain, Gen. 11:2), as does its purpose to provide a unifying center for all the peoples of the earth.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 3:2 satraps. A “satrap” was a governor of a “satrapy” (province); cf. Ezra 8:36.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 3:3 This chapter repeatedly states that this was the image that King Nebuchadnezzar had set up. It is unclear whether the image represented Nebuchadnezzar or one of his gods. All of the leading officials from throughout his empire were gathered before the statue for its dedication, as a public statement that the unity of Nebuchadnezzar’s empire was rooted in the common worship of the golden image.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 3:5 The Aramaic names for the lyre, harp, and bagpipe may well be words loaned from Greek. Some conclude that the story must therefore have come from the time of Greek cultural dominance, namely, after Alexander the Great (d. 323 B.C.). But since there was Greek cultural influence in the Near East long before Alexander, this is not evidence of a late date for the book.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 3:8–29 Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego Preserved in the Fiery Furnace. Daniel’s three friends, who serve Nebuchadnezzar as officials, refuse to obey the command to worship the statue, even under threat of a horrible death in a furnace. Sentenced to die, they are rescued, which amazes Nebuchadnezzar.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 3:12 Certain “Chaldeans” (v. 8—that is, the magicians, enchanters, etc.; cf. 2:2, 4) observed the fact that Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego had not joined in bowing to the statue. They charged the young men with ingratitude for the positions they held and impiety toward Nebuchadnezzar’s gods. Daniel himself is curiously absent; perhaps he is away on a mission, or perhaps above the administrative rulers mentioned in 3:3 and thus immune from such displays of Nebuchadnezzar’s pride, or perhaps the Chaldeans did not feel safe accusing Daniel.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 3:18 But if not. There was no doubt in the three men’s minds as to God’s power to save them (see 2:20–23). Yet the way in which God would work out his plan for them in this situation was less clear. God’s power is sometimes extended in dramatic ways to deliver his people, as when he parted the Red Sea for Israel on the way out of Egypt (Exodus 14); at other times, that same power is withheld, and his people are allowed to suffer. Either way, they would not bow down to Nebuchadnezzar’s image.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 3:19 In anger, Nebuchadnezzar ordered the furnace superheated: seven times more than it was usually heated is probably a figurative expression meaning “as hot as possible” (seven is a number signifying completion or perfection, cf. Prov. 24:16; 26:16).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 3:22 Ironically, Nebuchadnezzar’s order resulted in the death of his own soldiers, demonstrating the fact that the Lord is able to protect his servants better than Nebuchadnezzar can protect his.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 3:23 After this verse the various Greek OT versions add The Song of the Three Young Men, which is an effort to elaborate the men’s experience of deliverance in the furnace. (This addition to Daniel is also included in the Apocrypha: see article on The Apocrypha.)

DANIEL—NOTE ON 3:24–25 Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego were joined in the fire by a fourth individual, who had the appearance of a divine being like a son of the gods, who was either a Christophany (a physical appearance of Christ before his incarnation) or an angel (see v. 28). In either case, this is a physical demonstration of God’s presence with believers in their distress, a graphic fulfillment of the Lord’s promise in Isa. 43:2. The Lord promised his presence with his people, ensuring that their trials and difficulties would not utterly overwhelm them.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 3:27 Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego were completely untouched by the fire: their clothes were not harmed nor their hair singed, and they did not even smell of fire—a testimony to the comprehensiveness of the Lord’s protection.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 3:28 Nebuchadnezzar’s question in v. 15 had been decisively answered, as he himself was forced to testify. Yet his heart was not yet changed: the God of whom he spoke was still the God of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, or their … God, not his own.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 3:30 Nebuchadnezzar Promotes Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego. Nebuchadnezzar shows that he appreciates the integrity of these men.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 4:1–37 Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream of a Toppled Tree. Nebuchadnezzar has another dream, and Daniel again is the only one of his officials able to interpret it. This dream concerns Nebuchadnezzar’s own need to acknowledge that the God of Israel is the one who rules the affairs of mankind, and through humiliation Nebuchadnezzar learns the lesson.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 4:1–27 Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream and Its Interpretation. Nebuchadnezzar tells his dream to his wise men, but they cannot interpret it. Finally he asks Daniel, who shows respect and kindness to the king by explaining that the dream threatens him with humiliation if he does not acknowledge that God is supreme.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 4:1–3 The narrative begins at the end of the story, with the letter of praise to God that Nebuchadnezzar wrote after his recovery. The letter is addressed to peoples, nations, and languages, the same group summoned to bow down to the golden image (see 3:7). The “signs” and “wonders” the Lord has performed certainly include the fiery furnace, yet the key difference is that now Nebuchadnezzar speaks of signs and wonders that the Most High God has done for me (cf. note on 3:28). From being a persecutor of the faithful, Nebuchadnezzar has himself become a witness to the faith.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 4:7 This time Nebuchadnezzar tells the wise men of Babylon the dream—perhaps Nebuchadnezzar was not worried about their honesty since he expected that Daniel could correct them if they tried to deceive him.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 4:10–16 In this dream, Nebuchadnezzar saw an enormous tree whose top touched the heavens. While Nebuchadnezzar was looking on, however, a watcher, a holy one (an angel commissioned to carry out God’s judgment on earth) came down and ordered that the tree be cut down. The tree was not utterly destroyed, however: its stump was to remain in the ground for seven periods of time (the text does not explain the length of time, but “seven” signifies completion and most ancient and modern scholars have argued it was “seven years”), bound in iron and bronze.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 4:22 In his interpretation, Daniel identified the enormous tree as Nebuchadnezzar: it is you, O king. The image of a cosmic tree, the center and pivotal point of the universe, acknowledged Nebuchadnezzar’s power and might.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 4:23 The image of the cosmic tree reaching to the heavens (v. 11) is reminiscent of the Tower of Babel (see Gen. 11:4). Such hubris inevitably ends in disaster, and the divine lumberjack would bring the mighty tree crashing to the ground, removing it from its place of influence and glory. Nebuchadnezzar would not only lose his power and glory but also his rationality (which distinguishes him as human), so that he would behave like the wild animals. The one who thought of himself in godlike terms would become beastlike so he could learn that he is merely human after all. When the tree was cut down, the stump and the roots were allowed to remain, bound in iron and bronze, possibly suggesting that Nebuchadnezzar’s kingdom would be protected and then established after he learned to honor the true God.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 4:25 There was hope of restoration after Nebuchadnezzar had experienced a full period of judgment, seven periods of time, in this animal-like state. When Nebuchadnezzar acknowledged that God controls the universe and human kingdoms and that he (Nebuchadnezzar) does not, his kingdom would be restored to him. Daniel proclaimed God’s sovereignty over the affairs of nations, even over Babylon—the greatest nation in the world at that time—by affirming what Nebuchadnezzar had already heard in his dream (v. 17; cf. vv. 32, 35), that the Most High rules the kingdom of men and gives it to whom he will.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 4:27 Therefore, O king … break off your sins by practicing righteousness, and … showing mercy to the oppressed. Daniel (a Jew who believed in the one true God) was willing to tell Nebuchadnezzar (a pagan king) that he should conform to moral standards that Daniel had learned from God. This appeal to repentance implied that the fate depicted for Nebuchadnezzar in the dream was not inevitable, and it provided Nebuchadnezzar with an opportunity to repent of his pride. If Nebuchadnezzar humbled himself, God would not need to humble him further. Even pagan rulers are accountable to the God of the Bible (cf. notes on Ps. 82:1–4; Prov. 31:1–9; Mark 6:18; Acts 24:25).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 4:28–33 Nebuchadnezzar’s Humbling. A year went by, but Nebuchadnezzar was unchanged. The view from the roof of the royal palace of Babylon (v. 29) included numerous ornate temples, the hanging gardens (one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world), which he had built for his wife, and the outer wall of the city, wide enough for chariots driven by four horses to pass each other on the top. As he looked at these notable accomplishments, Nebuchadnezzar boasted to himself of his mighty power and glory (v. 30). Immediately, the sentence of judgment was announced from heaven. His royal authority was taken from him and he was driven away from Babylon. He ate grass and lived wild in the open air like the beasts of the field, growing his hair and nails unchecked like the birds of the air (v. 33).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 4:34–37 Nebuchadnezzar’s Exaltation. At the end of God’s appointed time of judgment, Nebuchadnezzar raised his eyes to heaven and his reason was restored. Once brought low by God, he was brought back to the heights and restored to control of his kingdom, demonstrating that the Lord is able both to humble the proud and to exalt the humble. The great and mighty persecutor of Israel, the destroyer of Jerusalem, was humbled by God’s grace and brought to confess God’s mercy. He blessed the Most High, and praised and honored him who lives forever. God used Daniel’s faithfulness to bring light to this Gentile.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 5:1–31 Belshazzar’s Feast. Daniel explains to the last king of Babylon that the writing on the wall is a message that the true God rules over all, and that in his own time he will vindicate his own name against those who defile it, no matter how powerful they are.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 5:1–4 An Idolatrous Feast. Greek historians recorded many lavish feasts in Babylon. At the center of Belshazzar’s great feast (v. 1) in 539 B.C. were the vessels of gold and of silver (v. 2) that had been taken from the Jerusalem temple by Nebuchadnezzar (cf. 1:2). Nebuchadnezzar was not literally the father of Belshazzar (5:2); Belshazzar was the son of Nabonidus, with whom he shared co-regency during the closing years of the Babylonian monarchy. The word “father” in Aramaic, like Hebrew, can mean “ancestor” or “predecessor” (v. 2, esv footnote), but Belshazzar wanted to emphasize his direct connection to this important ruler who had taken Babylon to its peak.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 5:5–9 An Unreadable Message. The fingers of a mysterious hand wrote on the plaster of the palace wall opposite the lampstand, where its message could be clearly seen, though not easily understood (v. 5). The king’s response was abject terror: literally, the “joints of his loins were loosened,” indicating that he lost strength in his hips and legs (v. 6). None of the Babylonian diviners were able to interpret the writing, in spite of the generous reward offered by Belshazzar. Anyone who interpreted the writing would be clothed with purple, a fabulously expensive color in the ancient world, and would wear a chain of gold, a mark of high rank (v. 7). He would also be the third ruler in the kingdom (v. 7), which may refer to being next highest to King Nabonidus and the co-regent Belshazzar, or may be a more general term for a high official.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 5:10–12 A Forgotten Interpreter. The queen most likely refers to the queen mother (v. 10, esv footnote), since the wives of the king were already present (v. 2). She reminded Belshazzar of the existence of Daniel, whose ability to interpret knotty problems had been repeatedly demonstrated during the time of his illustrious predecessor, Nebuchadnezzar. Nebuchadnezzar had appointed him chief of his wise men, because the spirit of the holy gods (or “God”; the Aramaic is ambiguous) indwelt him (v. 11), enabling him to answer difficult questions.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 5:12 Daniel’s Babylonian name, Belteshazzar, probably means “O Lady [wife of the god Bel], protect the king!” It is similar to Belshazzar, which means, “O Bel, protect the king!”

DANIEL—NOTE ON 5:13–31 A Message of Judgment. Daniel alone is able to decipher the writing on the wall, and he shows that it is a message from the true God, telling of the end of the Babylonian Empire.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 5:13–16 Belshazzar addresses him not as the Daniel whom his father made chief of his wise men, but as the Daniel whom his father brought as one of the exiles from Judah. But he does pay Daniel a significant compliment, recognizing that he has heard that Daniel has special insight and can reveal difficult problems.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 5:17 Daniel’s blunt response omitted the usual deferential politeness of the Babylonian court.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 5:18 Daniel contrasted Belshazzar with Nebuchadnezzar, to whom the Most High God gave … kingship and greatness and glory and majesty. Nebuchadnezzar was given godlike powers to kill and keep alive, to raise up and to humble. Yet when he became proud, God humbled him comprehensively until he confessed the power of God (see ch. 4).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 5:23 Belshazzar knew of Nebuchadnezzar’s humbling, yet far from humbling himself, he lifted himself up … against the Lord of heaven by using the sacred vessels from the Jerusalem temple for an idolatrous feast.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 5:25 Daniel read and interpreted the writing … MENE, MENE, TEKEL, and PARSIN. The words are clearly Aramaic and form a sequence of weights, decreasing from a mina, to a shekel (1/60th of a mina), to a half-shekel. It was not that the king and wise men could not read them, but they failed to understand their significance for Belshazzar. Read as verbs (with different vowels attached to the Aramaic consonants), the sequence becomes: “Numbered, numbered, weighed, and divided.” The Lord had numbered the days of Belshazzar’s kingdom and brought it to an end because he had been weighed in the balance and found wanting (v. 27). The repetition of “numbered” may suggest that it will occur quickly.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 5:28 As a result, Belshazzar’s kingdom would be divided and given to the Medes and the Persians (“Peres,” the singular of “PARSIN,” sounds like the Aramaic for “Persia”).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 5:30–31 Belshazzar gave Daniel the promised reward (v. 29), but it was an empty gift because that very night Belshazzar’s rule ended, when the Medes and the Persians entered Babylon. Belshazzar was killed and replaced as king by Darius the Mede. Belshazzar’s feast is exposed as the ultimate act of folly: he was feasting on the brink of the grave and either did not know the danger or refused to acknowledge it. The identity of Darius the Mede and the exact nature of his relationship to Cyrus is not certain. It is clear that Cyrus was already king of Persia at the time when Babylon fell to the Persians (539 B.C.), and thus far no reference to “Darius the Mede” has been found in the contemporary documents that have survived. That absence, however, does not prove that the references to Darius in the book of Daniel are a historical anachronism. The book of Daniel recognizes that Cyrus reigned shortly after the fall of Babylon (1:1; 6:28), and knowledge of the history of this period, while substantial, may be incomplete. Until fairly recently there was no cuneiform evidence to prove the existence of Belshazzar either. Some commentators argue that Darius was a Babylonian throne name adopted by Cyrus himself. On this view, 6:28 should be understood as, “during the reign of Darius the Mede, that is, the reign of Cyrus the Persian.” Others suggest that Darius was actually Cyrus’s general, elsewhere named Gubaru or Ugbaru, and credited in the Nabonidus Chronicle with the capture of Babylon.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 6:1–28 The Lions’ Den. In an episode that reminds us of ch. 3, but this time in the Medo-Persian court, Daniel refuses to treat the Persian king as the gods’ chief representative. When God delivers him from the lions, Darius learns to respect the God of Daniel.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 6:1–3 Daniel Promoted. Daniel had served the empire faithfully for almost 70 years, and he continued to serve the new Medo-Persian administration. The satraps were provincial rulers, responsible for security and collection of tribute. The three high officials oversaw their work, making sure the tribute reached the king’s treasury. As one of these three, Daniel received the reward promised by Belshazzar (see 5:29), in spite of Belshazzar’s demise. Daniel did such an excellent job in this role that Darius planned to set him in an even higher position, over the whole kingdom (6:3).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 6:4–15 The Administrators Plot to Remove Daniel. The other officials in the Medo-Persian court, jealous of Daniel’s successful service, conspire to bring about a royal edict that they know Daniel cannot obey.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 6:5 Daniel’s faithfulness earned him some powerful enemies, either through jealousy or because his incorruptibility restricted their opportunities to enhance their income. Yet his character was such that they knew that the only way to bring a charge against him was in the area of the law of his God.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 6:6–7 The high officials and the satraps came together by agreement (Aramaic regash); the equivalent Hebrew (Hb. ragash) depicts the nations “noisily assembling” against the Lord and his anointed (Ps. 2:1). They went to King Darius with a proposal for a new law: for the next thirty days no one was to petition any god or man … except the king himself; all offenders would be cast into the den of lions. Darius likely viewed this law as a political rather than a religious edict, seeing it as a means of uniting the realm by identifying himself as the sole mediator between the people and the gods, the source of their every blessing.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 6:8 the law of the Medes and the Persians, which cannot be revoked (cf. Est. 1:19; 8:8). This motif does not mean that the Medo-Persian Empire never changed its mind. Yet the concept of the king’s word as inflexible and unchanging law underlined the fixed nature of the king’s decisions. While it was always possible for the king to issue a contrary counter-edict, to do so would result in an enormous loss of face.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 6:10 Daniel continued his practice of prostrating himself three times daily toward Jerusalem, consciously fulfilling the scenario described in Solomon’s prayer at the dedication of the temple in Jerusalem (1 Kings 8:46–50). This practice must have made it easy for the satraps and high officials to gather the evidence necessary to convict Daniel.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 6:12 When his officials approached King Darius, they first asked the king to reaffirm the unchangeability of the decree, to make it hard for him to circumvent it. In spite of the king’s efforts to deliver Daniel, he was forced to acknowledge the fact that his decree condemned Daniel to the den of lions (v. 16).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 6:16–24 Daniel Preserved in the Lions’ Den. An angel protects Daniel from the lions overnight; but the accusers have no such protection.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 6:16–18 To make sure that no outside help was given to Daniel, the mouth of the den was covered with a stone, which was then sealed with the signet rings of the king and his lords. Humanly speaking, Daniel was left all alone to face his fate. Yet Darius’s last words to Daniel pointed to a higher source of help: “May your God, whom you serve continually, deliver you!”

DANIEL—NOTE ON 6:19–23 At break of day, Darius arose and hurried to the lions’ den, where he discovered that Daniel had spent a far more comfortable night surrounded by wild animals than Darius did in his royal luxury. Because Daniel trusted in his God and was found blameless before him, God sent his angel and shut the mouths of the lions so that they were unable to hurt him. The meaning of Daniel’s name, “God is my Judge,” was thus affirmed.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 6:24 After Daniel’s release, those who had schemed against him were thrown to the same lions. This was in accord with the common principle in the ancient Near East that anyone who made a false charge against someone else should be punished by receiving the same fate they had sought for their victim (cf. Deut. 19:16–21). In line with the ruthless practice of the Persians, the sentence was also carried out on the families of the guilty men: their children, and their wives. The experience of the conspirators in the den was the exact opposite of Daniel’s: they were seized and killed by the lions before they even hit the bottom of the den.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 6:25–27 Darius Acknowledges the Power of Daniel’s God. Darius, like Nebuchadnezzar, confesses the awesome power and protection of Daniel’s God: he is the living God … his kingdom shall never be destroyed (v. 26).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 6:28 Daniel Preserved Until the End of the Exile. For the relationship of Darius and Cyrus, see note on 5:30–31. This closing comment rounds off the story of Daniel’s life and puts his experience in the lions’ den into a broader context. It reminds the reader that Daniel’s entire life was spent in exile, in a metaphorical lions’ den. Yet God preserved him alive and unharmed throughout the whole of that time, enabling him to prosper under successive kings until the time of King Cyrus, when his prayers for Jerusalem finally began to be answered. Cyrus was God’s chosen instrument to bring about the return from the exile, when he issued a decree that the Jews could return to their homeland and rebuild Jerusalem (see 2 Chron. 36:22–23; Ezra 1:1–3).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 7:1–12:13 The Visions of Daniel. These chapters describe Daniel’s apocalyptic visions, which reassure God’s people that, in spite of exile and persecution, God is still in control of history and will see his purposes through.

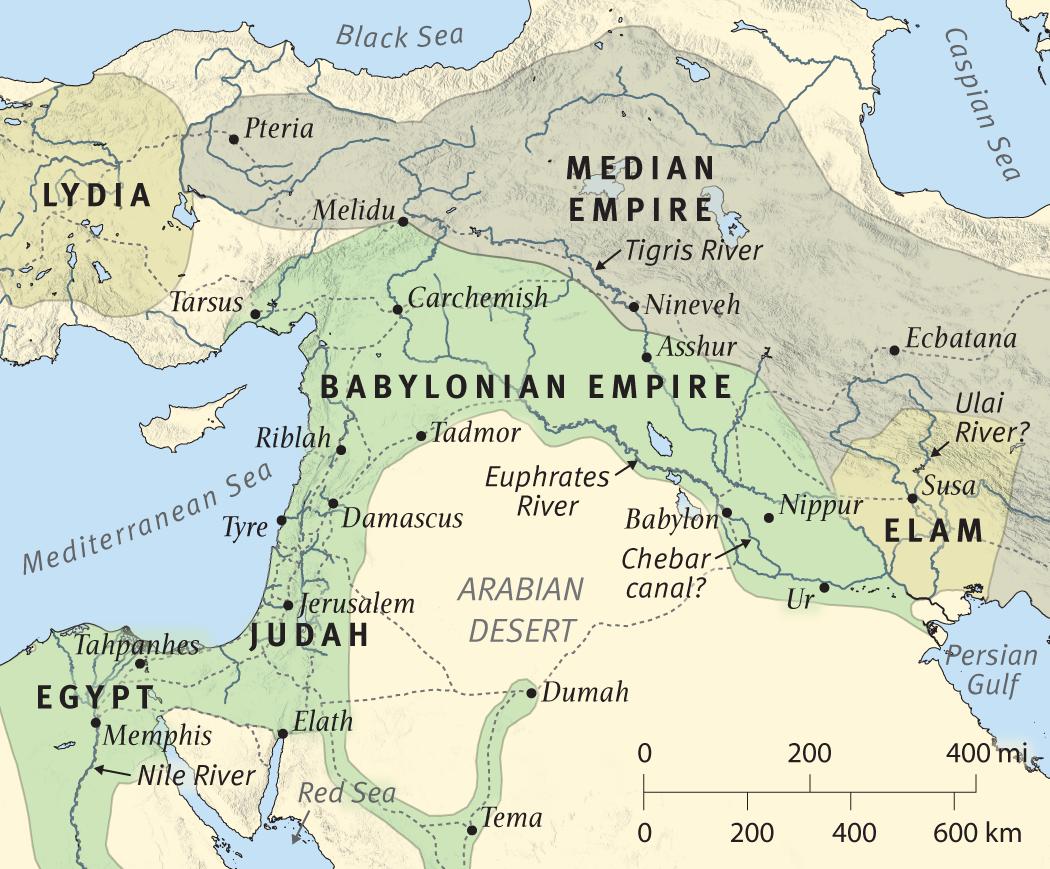

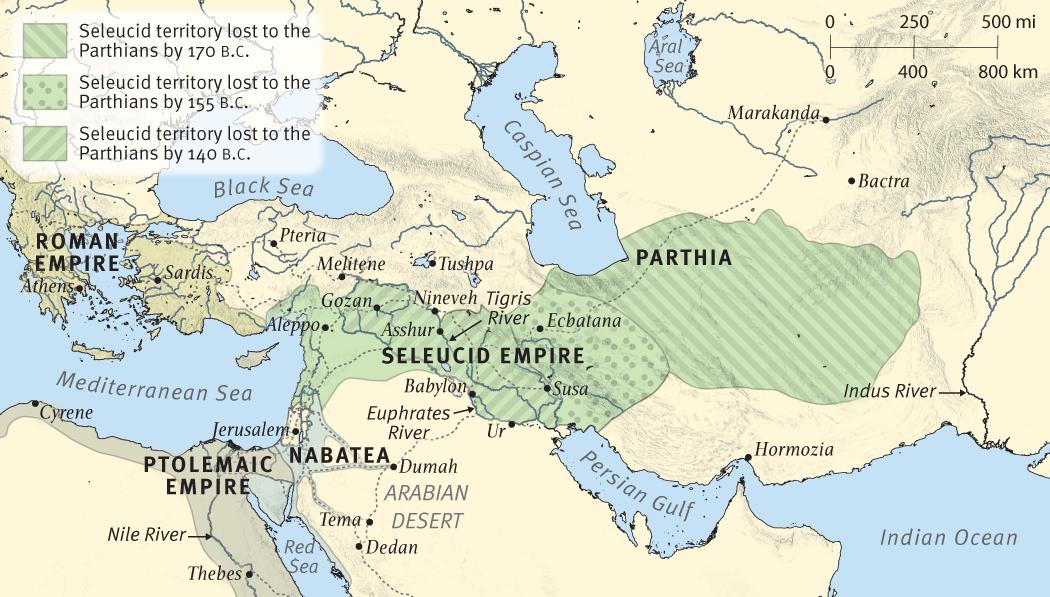

The Empires of Daniel’s Visions: The Babylonians

c. 605–538 B.C.

Though their empire was short-lived by comparison with the Assyrians before them and the Persians after them, the Babylonians dominated the Near East during the early days of Daniel, and they were responsible for his initial exile to Babylon. Daniel himself, however, outlived the Babylonian Empire, which fell to the Persians in 538 B.C.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 7:1–28 The Vision of Four Great Beasts and the Heavenly Court. In this vision, four beasts represent four mighty kings (or kingdoms); nevertheless, God’s plan to exalt his faithful will be victorious.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 7:1–8 The Four Great Beasts. The vision, of four wild winds and of four great beasts, is of seemingly uncontrollable forces.

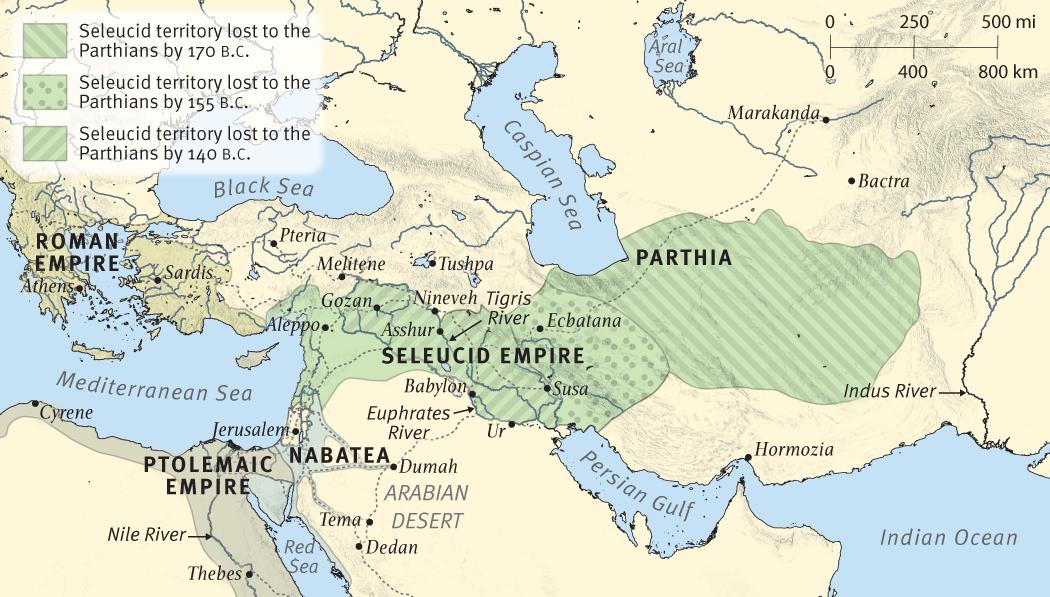

DANIEL—NOTE ON 7:1–2 Daniel received the vision during the first year of Belshazzar (c. 552 B.C.), when the Babylonians still ruled the world (and thus before the events of ch. 5; see map). He saw the four winds of heaven (i.e., each of the four compass points, suggesting winds from all parts of the earth) stirring up the great sea, a symbol for chaos and potential rebellion against God (cf. Ps. 89:9; 93:3–4, which show that these are elements of nature still under God’s rule), and the home of evil monsters such as the multiheaded monster Leviathan (Ps. 74:13–14).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 7:3 This stirred-up sea produced four startling creatures, one after the other, each more frightening than the preceding one. In v. 17 Daniel is told that the “four great beasts are four kings who shall arise out of the earth.” The number four may indicate the literal number of kingdoms or kings, or it may simply describe a complete series (cf. “the four winds of heaven”). Most interpreters see these as representing the same kings (or kingdoms) as the image in Nebuchadnezzar’s dream in 2:31–45. On this understanding, the lion (7:4) represents Babylon, and the wings being “plucked off” (v. 4) represent the humbling of Nebuchadnezzar. The bear (v. 5) represents Medo-Persia, with the stronger Persian component being the side that was “raised up” (v. 5). The leopard (v. 6) represents Alexander the Great and his speedy conquest of the civilized world, and the “four heads” represent the division of his kingdom into four parts after his death. The final, terrifying beast (vv. 7–8) then represents the Roman Empire.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 7:4 The first beast was like a lion with eagles’ wings, a mixture of animal and bird. This beast signifies the strength and majesty of a lion combined with the speed and power of an eagle. Both images were used by Jeremiah to depict Nebuchadnezzar (e.g., Jer. 49:19–22). This beast had his wings plucked off and was transformed into a man, recalling the humbling and restoration of Nebuchadnezzar (cf. Daniel 4).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 7:5 The second beast was like a bear, raised up on one side—either poised and ready to spring or grotesquely deformed. Many scholars think the raised up side suggests the unequal power of the two countries combined in the Medo-Persian Empire (cf. 8:3, 20). It had a mouth full of the ribs of its previous victim(s)—maybe more specifically the people Cyrus conquered to unify his nation (e.g., Astyages [550 B.C.], Anatolia [547], and Croesus of Lydia [c. 547]). However, he was told to arise and devour even more (i.e., the Babylonians). The three ribs could also represent the three countries that Medo-Persia conquered (Babylon, 539 B.C.; Lydia, 546; and Egypt, 525). This empire controlled the land from Egypt and the Aegean Sea on the west to the Indus River on the east.

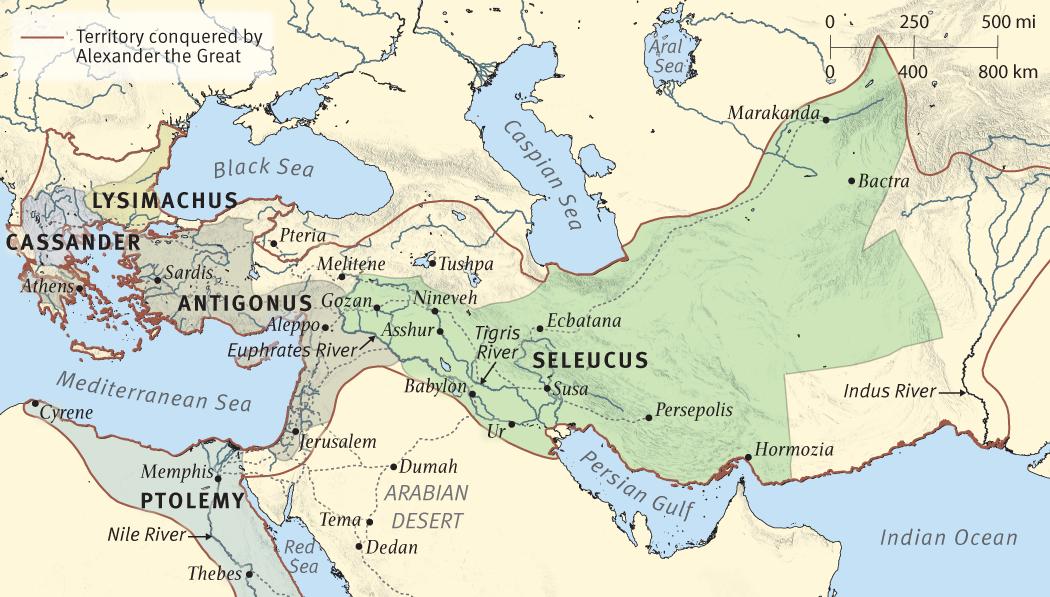

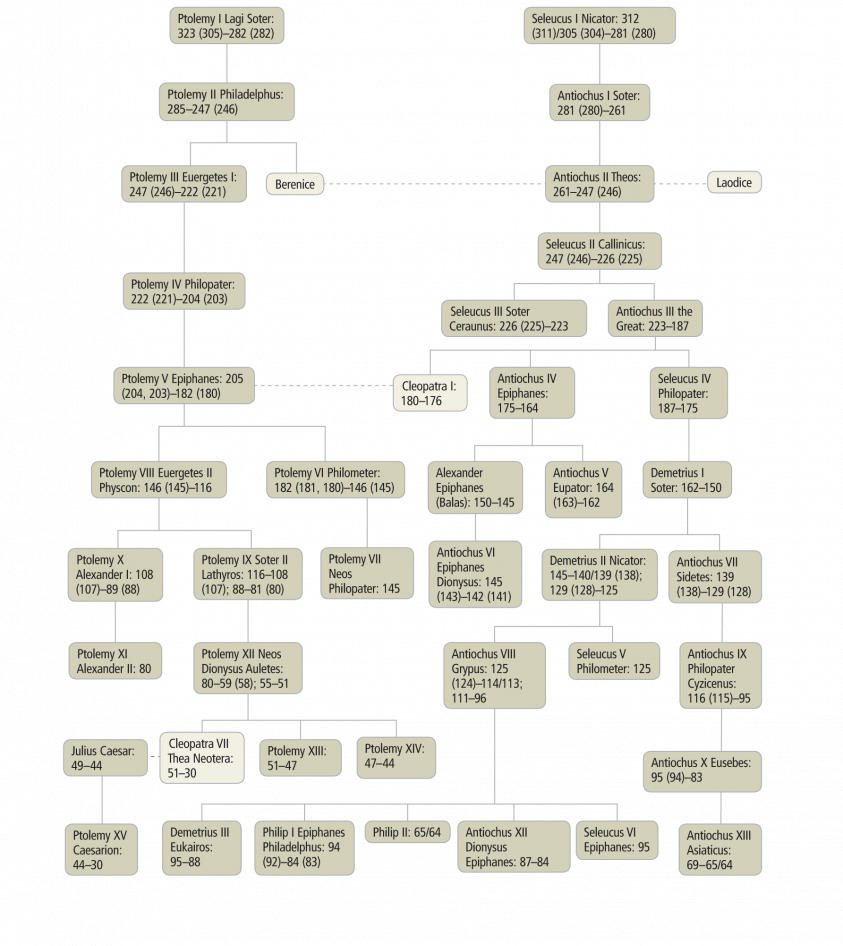

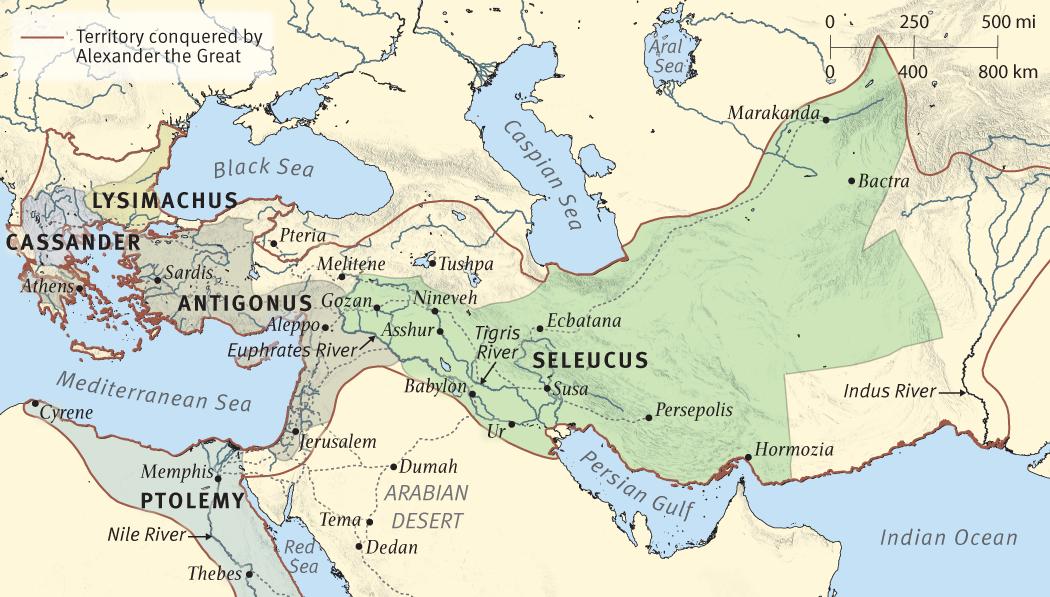

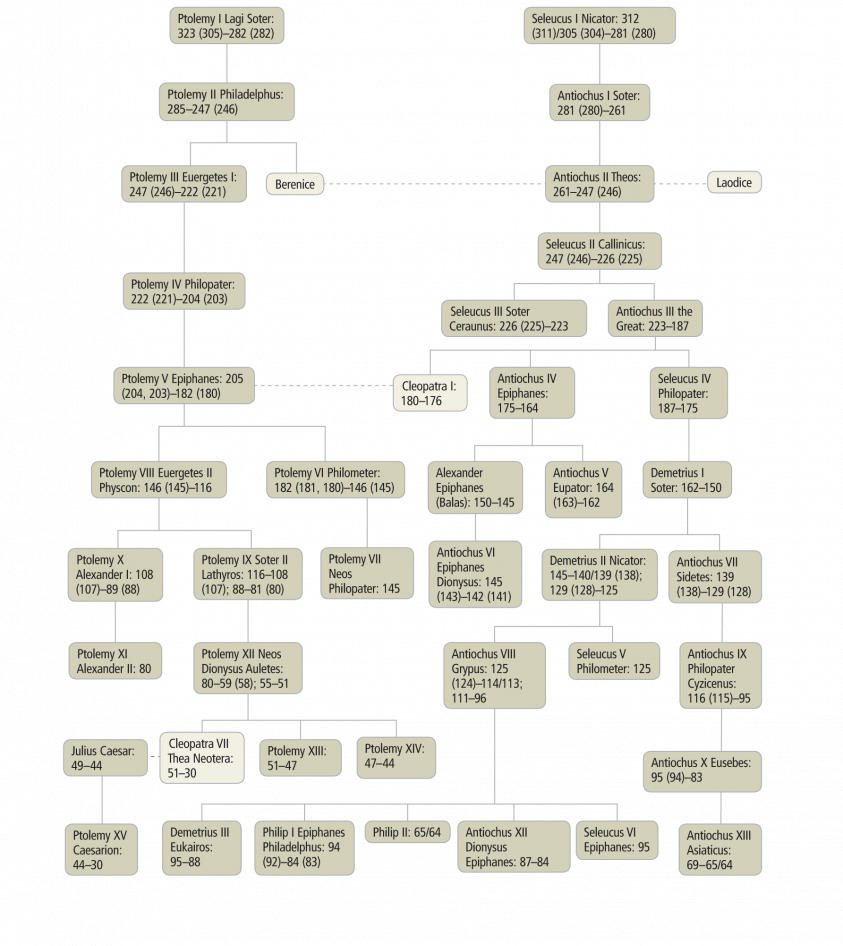

DANIEL—NOTE ON 7:6 The third beast was like another composite animal, part leopard, part bird, with four wings and four heads. It combined ferocity and speed with the ability to see in all four directions at once. Leopards are known for speed (cf. Hab. 1:8), keen eyesight, and keen hearing, allowing them to stalk their prey and pounce unsuspectingly. But the four wings emphasize even more the element of speed, which corresponds well to Alexander the Great’s conquest of the known world by age 32. Alexander invaded Asia Minor in 334 B.C., and within 10 years had conquered the whole Persian Empire. After his death in 323 B.C., his empire was divided among four of his generals: Antipater and later Cassander ruled in Greece and Macedon; Lysimachus in Thrace and much of Asia Minor; Seleucus I Nicator in Mesopotamia and Persia; and Ptolemy I Soter in Egypt and Palestine. These four rulers are symbolized by the four heads (cf. the four horns depicting leaders of Greece in Dan. 8:8, 21–22). Notice that dominion was given to it, suggesting a higher power controlling these actions.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 7:7 The fourth beast cannot be described in terms of earthly animals. It was terrifying and dreadful, exceedingly strong, with great iron teeth that devoured and crushed, and it trampled down whatever it did not eat. Its head had ten horns (cf. ten toes, 2:42), symbolizing at least multiplied strength.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 7:8 Even more surprisingly, another small horn came up among the horns, uprooting three of the 10 others. This horn had eyes and a mouth that spoke arrogantly. If this vision corresponds to the statue in ch. 2, then it would represent the Roman Empire (cf. iron teeth with iron legs, 2:33; see also Midrash on Psalms 80.6) and emphasize its ruthlessness. The Roman Empire was significantly different than the earlier empires, for it far surpassed them in power, longevity, and influence. The world had never before seen anything like it. The 10 horns could emphasize the extreme power of this empire (five times the normal number of two horns), or more likely it signifies 10 rulers or kingdoms (cf. Dan. 7:24; from Julius Caesar to Domitian there are actually 12 Caesars; but two reigned for only a few months). The little horn was significantly different than the others, for it had teeth of iron, claws of bronze, and eyes like the eyes of a man. It started “little” but grew up to overpower three of the other horns. Some scholars understand this horn to refer to Antiochus IV Epiphanes (see note on 8:23), but many have understood it to refer to the Antichrist (see note on 7:15–27).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 7:9–12 The Ancient of Days Judges the Beasts. At the center of Daniel’s vision was the heavenly courtroom, with thrones (perhaps for the saints, cf. Rev. 4:2–4; 20:4) set up for judgment. The Ancient of Days (Dan. 7:9), God himself, sat on the central throne. His clothing was white as snow, representing uncompromising and radiant purity (cf. Ps. 51:7; Isa. 1:18; Rev. 19:14); his hair was as white as pure wool, symbolizing the wisdom that comes with great age. His chariot-throne was flaming with fire and its wheels were ablaze (cf. Ezekiel 1), images of the divine warrior’s fearsome power to destroy his enemies. A stream of fire flowed out from before him (Dan. 7:10), and he was surrounded by myriads upon myriads of angelic attendants. The scene depicts in powerful imagery a judge who has the wisdom to sort out right from wrong, the purity to persistently choose the right, and the power to enforce his judgments. Even though the beast with the boastful horn continued to mouth defiance at the heavenly court, it was swiftly slain and its body thrown into the fire.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 7:10 Ten thousand times ten thousand is meant as a picture of an innumerable multitude, representing not one kingdom but all the kingdoms of the earth standing before God (cf. Rev. 5:11). The books that were opened represent God’s records of the deeds of those on the earth (cf. Dan. 12:1; Luke 10:20; Rev. 20:12, which echo this passage).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 7:11–12 As Daniel kept watching, the boastful little horn was finally silenced: the beast was killed, and its body destroyed and given over to be burned with fire (cf. Rev. 19:20). Daniel looked back at the other beasts and their dominion was taken away, but they were not destroyed like this last beast. Their kingdoms remained for a time set by God and then were incorporated into the following kingdom.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 7:13–14 The Coming of the Son of Man. The one like a son of man combines in one person both human and divine traits. Elsewhere, this phrase “son of man” often distinguishes mere human beings from God (e.g., Ps. 8:4; Ezek. 2:1). However, this son of man seems also greater than any mere human, for to “come on the clouds” is a clear symbol of divine authority (cf. Ps. 104:3; Isa. 19:1). This “son of man” is given dominion and glory and a kingdom (Dan. 7:14; cf. esv footnote at v. 27; this is parallel to God’s dominion, 4:34), which at present resides in the hands of human kings such as Nebuchadnezzar (cf. 5:18). But he is far greater than Nebuchadnezzar, because he will rule over the entire world forever: all peoples, nations, and languages will serve (or worship) him, and his dominion … shall not pass away (7:14). Thus, he must be much more than a personified representative of Israel (cf. vv. 18, 27), and certainly more than a mere angel, for no created being would have the right to rule the entire world forever. Jesus claims he will fulfill this role (cf. Mark 14:61–62), and it is ultimately fulfilled in Rev. 19:11–16 when Jesus comes at the end of the age to judge and rule the nations. Jesus refers to himself as “son of man” more than any other title (see notes on Matt. 8:20; John 1:51). This title was used in the OT in two different ways, first, to refer to a mere human being (see esp. Ezekiel, where it is used over 90 times referring to Ezekiel), and second, to refer to the son of man in Dan. 7:13, who is a divine being dwelling in heaven with the Ancient of Days. When people heard Jesus use the term “son of man” for himself, they had to decide which type of “son of man” he was. Technically he was both, but it took faith to believe he was like the “son of man” in Daniel. At the end of Jesus’ ministry, when he claimed to be this heavenly “son of man” predicted in Daniel’s vision, his opponents said he had committed blasphemy (see notes on Matt. 8:20; 24:30; 26:64).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 7:15–27 The Interpretation of the Vision. As in ch. 2, many interpreters have identified the four beasts of ch. 7 as Babylon, Medo-Persia, Greece, and Rome (see note on 2:43–44). The beasts in general show the present world order as an ongoing state of violence and lust for power that will continue until the final coming of God’s kingdom. The fourth beast will be different from those before it in power and duration, and its 10 horns are 10 kings or kingdoms (7:24). A little horn will grow up afterward and overpower three (if 10 signifies “completeness,” then three represents “some”) of the kings, which may refer to specific kings. As for the “little” horn (v. 8) who made war with the saints and prevailed over them (v. 21) and who shall wear out the saints (v. 25), many take this to represent the Antichrist, whom they expect in the end times (see notes on Matt. 24:15; Mark 13:19; 2 Thess. 2:3; 2:4; 2:9–10; 1 John 2:18; Rev. 11:1–2; 12:6; 13:1–10; 13:5). Other interpreters think there is not enough precise data to identify the little horn. It is clear, however, that this king will blaspheme against God (Dan. 7:25), oppress the saints (vv. 21, 25), and try to abolish the calendar and the law (v. 25), which govern how God’s people worship. The saints will be handed over into his power for a time, times, and half a time (v. 25)—totaling three and a half times, or half of a total period of seven times of judgment (see 4:16; 9:27). To some extent, the description fits several historical tyrants, particularly Antiochus IV Epiphanes (reigned 175–164 B.C.; see note on 8:23), who oppressed God’s people in the second century B.C., yet at the same time it is non-specific enough to leave the identity of this horn somewhat uncertain. The angel seems more concerned to drive home his earlier words about the judgment to come and the triumph of the saints than to identify the little horn. The central point of the vision is that the time when the beastly kingdoms of the earth will oppress the saints is limited by God, and beyond it lies the scene of the heavenly court, where the beasts will finally be tamed and destroyed (cf. Rev. 20:1–4, 10).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 7:28 Daniel’s Response. Daniel, stunned, has strength only to ponder the vision related in this chapter.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 8:1–27 The Vision of the Ram, the Goat, and the Little Horn. In this vision, Daniel sees what is to come of the Medo-Persian Empire, Alexander the Great’s empire, and the Hellenistic empires that succeed it. The upheavals to come will mean terrible times for the people of God, but they must endure, knowing that God rules over it all.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 8:1–14 The Vision of the Ram and the Goat. Daniel sees a vision of a swift goat defeating a mighty ram, only to be succeeded by four horns. This vision, given in the third year of the reign of King Belshazzar (c. 550 B.C.), occurred about the same time that Cyrus conquered the Medes and united the two kingdoms.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 8:3 In this vision, Daniel saw an all-powerful ram with two horns, one of which was longer than the other. The ram represents the Medo-Persian Empire (see map), with the higher horn representing the stronger, Persian part (see v. 20). (The horns of an animal, which it uses both for defensive and offensive fighting, are frequently found in Scripture as a symbol of the military power of a nation.)

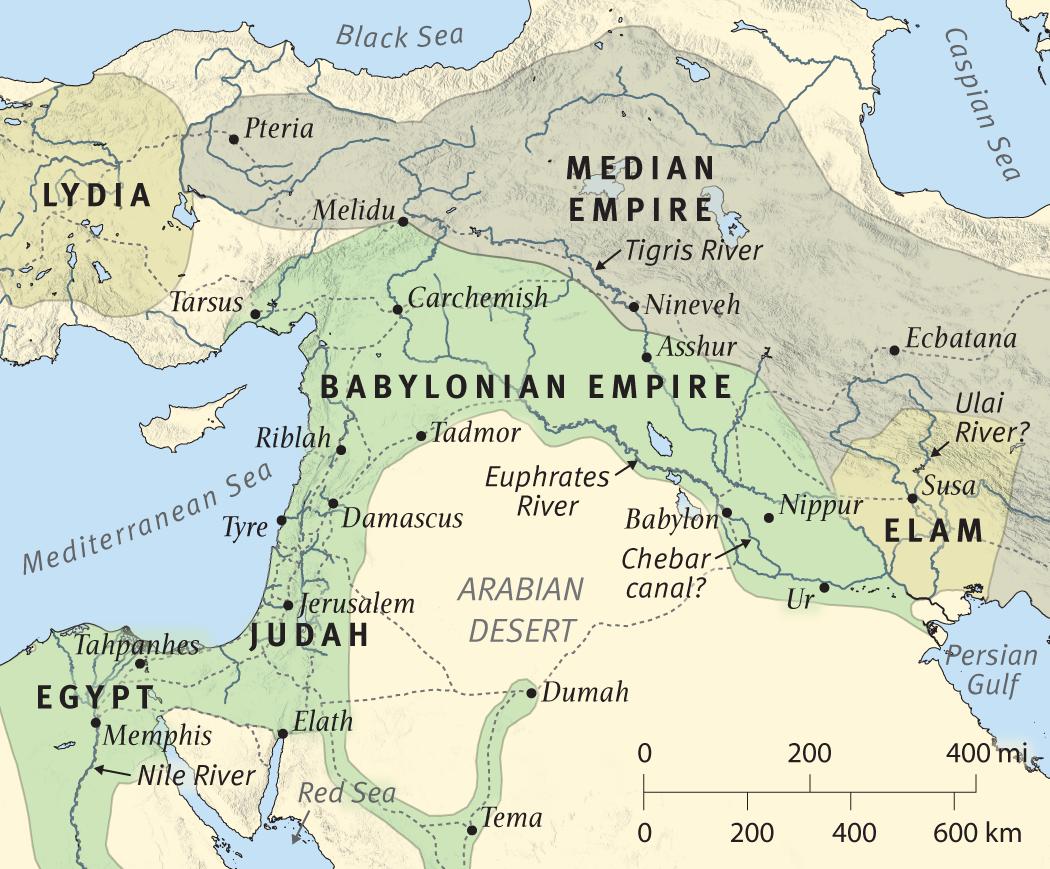

The Empires of Daniel’s Visions: The Persians

c. 538–331 B.C.

After Cyrus the Great united the Median and Persian empires, he overthrew the Babylonians and established the greatest power the world had ever known. Under later rulers the Persian Empire eventually extended from Egypt and Thrace to the borders of India, and Cyrus himself declared, “the LORD, the God of heaven, has given me all the kingdoms of the earth” (2 Chron. 36:23; Ezra 1:2). Consistent with his regular policies to promote loyalty among his subjugated peoples, Cyrus immediately released the exiled Jews from their captivity in Babylon and even sponsored the rebuilding of the temple.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 8:5–8 A male goat with a single conspicuous horn appeared and destroyed the ram, yet at the pinnacle of his power, the single horn was shattered and four conspicuous horns replaced it (v. 8). This vision is a striking prediction of the Medo-Persian and Greek empires (see note on vv. 20–22). It is so accurate that some interpreters, who do not think the Bible can contain truly predictive prophecy (and others who think that such specific predictions are not suited to the normal pattern of biblical prophecy), claim that this material was not written in the sixth century by Daniel but had to be written after these events occurred (see Introduction: Date).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 8:5 a male goat came from the west. Alexander the Great came from Greece, which was to the “west” of both Babylon and Persia. without touching the ground. Alexander conquered the mighty Persian Empire with amazing speed, from 334–331 B.C. (He is also represented as a leopard with four wings in 7:6.)

DANIEL—NOTE ON 8:7 he was enraged. Alexander’s father was king of Macedonia (a land north of Greece) and brought all of Greece under his control by 336 B.C. Alexander was only 20 when his father was murdered, but managed to consolidate his hold on Greece and to unify the Greeks with “rage” over the way the Persians had been attacking them and meddling in their affairs for the previous two centuries.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 8:8 the goat became exceedingly great. Alexander the Great’s kingdom extended all the way to India, exceeding any kingdom before it in size (approx. 1.5 million square miles/3,885,000 square km). there came up four conspicuous horns. After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C., his two sons initially took over the empire, but ultimately, after serious internal struggles, four of his generals divided his kingdom into four parts (cf. v. 22 and 7:6).

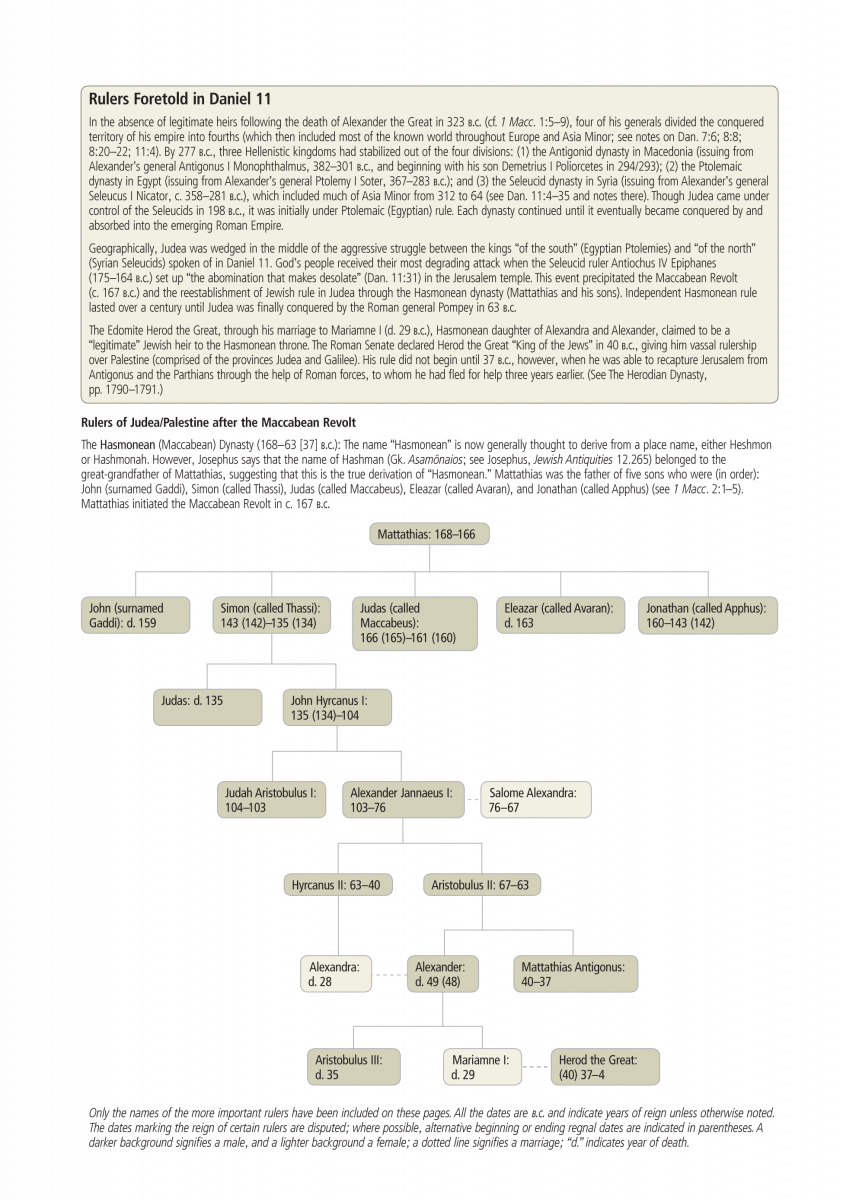

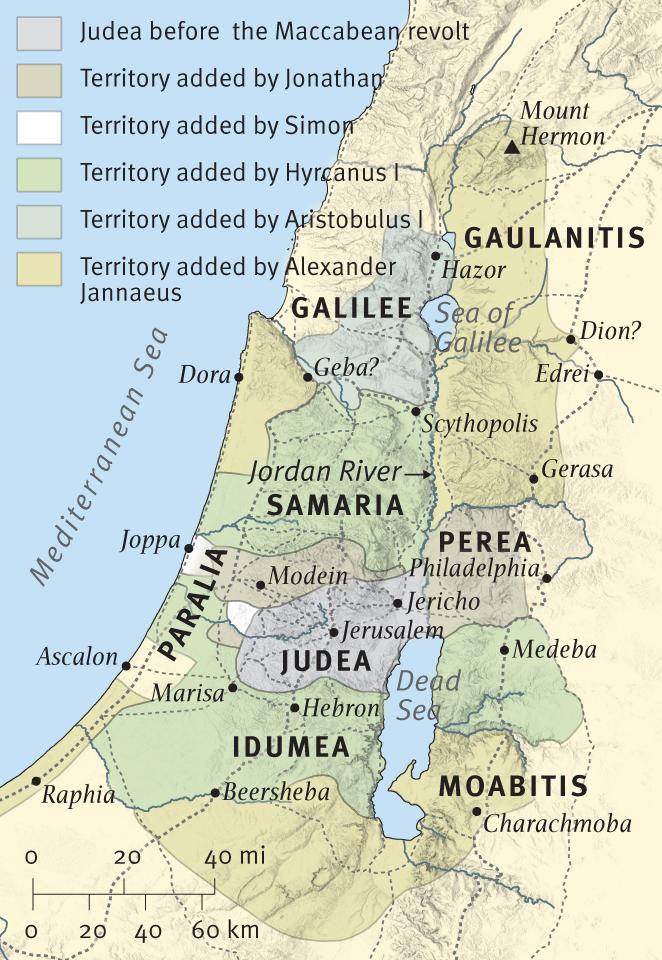

DANIEL—NOTE ON 8:9–10 A little horn grows out of one of the four horns and expands his realm. Scholars are almost unanimous in recognizing this little horn as the eighth ruler of the Seleucid dynasty, Antiochus IV Epiphanes (ruled 175–164 B.C.; see notes on vv. 23 and 25). The glorious land most likely refers to Palestine as God’s primary center of operations and the location of his people. This horn grew great, even to the host of heaven, and some of the stars it threw down to the ground. This almost certainly refers to saints who were killed during Antiochus IV’s reign. It began with the assassination of the high priest Onias III in 170 B.C. and continued to the death of Antiochus IV in 164. Within those few years, he executed thousands of Jews.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 8:11 the place of his sanctuary was overthrown. According to the Jewish history recorded in 1 Maccabees (in the Apocrypha), Antiochus IV tried to unify his realm by forcing the Jews to forsake their law and cultural distinctives, but when they refused he punished them severely (see note on Dan. 8:23). The Prince of the host probably refers to God, because of the similar expression “Prince of princes” in v. 25, though some have argued that it is the high priest Onias III.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 8:12–14 Because of renewed transgression on the part of God’s people, the saints and the temple sacrifices were handed over into the hands of Antiochus IV, but only for a limited period: 2,300 evenings and mornings, or a little over six years (perhaps signifying the period from 170 B.C., the death of Onias III, the high priest, to December 14, 164, when Judas Maccabeus cleansed and rededicated the temple; cf. 1 Macc. 4:52). In the end, the little horn would be judged and the sanctuary restored to its rightful state. Unlike the less precise “time, times, and half a time” of Dan. 7:25, this period is measured in days, suggesting that God has a precise calendar for the times of his people’s suffering, even though it is utterly inscrutable to human wisdom.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 8:15–26 The Interpretation of the Vision. The angel Gabriel explains to Daniel that the vision concerns the future of the region, which God rules over for his purposes. The vision is given to prepare God’s people for the coming events, even the severe persecutions under Antiochus IV Epiphanes.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 8:20–22 Unlike the vision of ch. 7, this vision of 8:3–14 is precisely interpreted by the angel: the two-horned ram represents the kings of Media and Persia, of whom Cyrus, king of Persia, became the dominant partner (c. 550 B.C.). The goat was the king of Greece (v. 21), Alexander the Great, who defeated the Persians and conquered most of the then-known world. When he died in 323 B.C., his empire was divided among his four generals, fulfilling the prophecy in v. 22: four kingdoms shall arise from his nation, but not with his power (cf. v. 8).

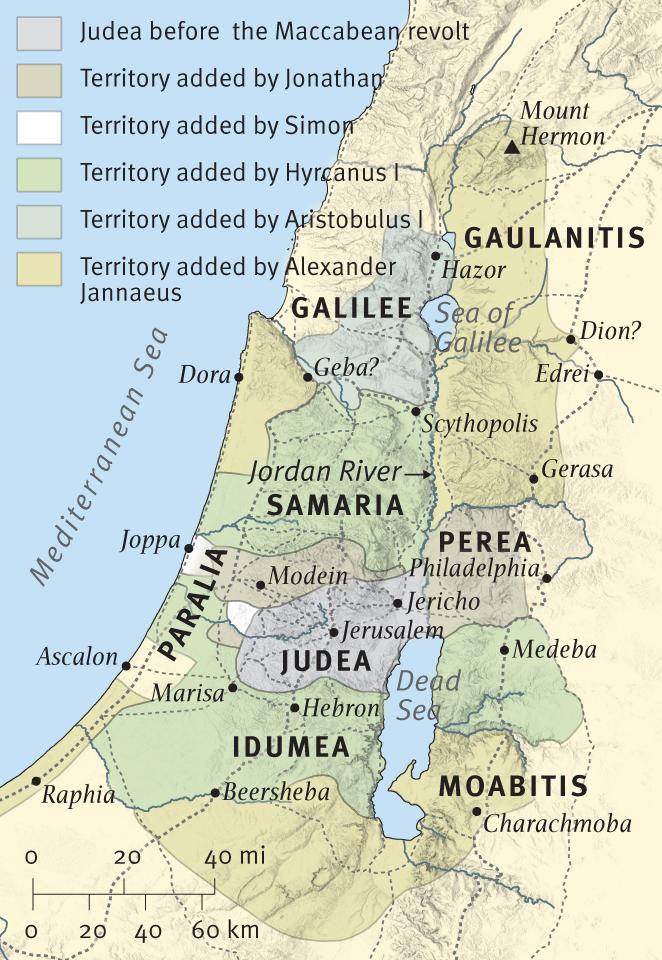

The Empires of Daniel’s Visions: The Greeks

c. 335–303 B.C.

The ascension of Alexander the Great to the throne of the Macedonian kingdom (in northern Greece) spelled the end for the mighty Persian Empire. After gaining the loyalty of the other city-states of Greece, Alexander’s astounding military prowess and success enabled him to systematically overtake virtually all of Persia’s former territory within 12 years. Soon after he died in Babylon at age 33 (323 B.C.), Alexander’s conquered territory was divided among his generals, who constantly vied for power among each other until their territories resembled those shown here (c. 303).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 8:23 The “little horn” of v. 9 then corresponds to a king of bold face, who was completely wicked (see note on vv. 20–22). This describes Antiochus IV Epiphanes (reigned 175–164 B.C.). He was king of the Seleucid Empire, one of the four kingdoms that emerged from Alexander the Great’s former territory (stretching from Asia Minor through Persia). He seized the throne from his nephew and enlarged his kingdom through military power. Antiochus IV was a tyrant who tried to unify his kingdom by forcing all of his subjects to adopt Greek cultural and religious practices. He banned circumcision, ended sacrifice at the temple in Jerusalem (fulfilling v. 11, “the regular burnt offering was taken away”), and deliberately defiled the temple by sacrificing a pig on the altar and placing an object sacred to Zeus in the Holy of Holies (fulfilling v. 13, “the giving over of the sanctuary … to be trampled underfoot”; cf. v. 11, and 1 Macc. 1:37–59; 2 Macc. 6:2–5). He burned copies of the Scriptures and slaughtered those who remained true to their faith in God (cf. Dan. 8:10, 24–25).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 8:25 he shall even rise up against the Prince of princes. This title refers to God and indicates the rebellion of Antiochus IV against even God’s legitimate sovereignty. Antiochus IV’s coins even have the phrase “god manifest” (Gk. theos epiphanēs) on the back of them (see note on 11:37–38), which probably means that he thought he was the gods’ representative on earth.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 8:27 Daniel’s Response. Even though Daniel did not fully understand the vision, he was nonetheless overcome, appalled, and sickened by it, for he recognized and understood the severity of the future suffering coming on his own people. Like the other prophets, he identified with his people when they faced the judgment of God (see Ezek. 3:14–15). Yet in spite of his deep concern for the future, he went about the king’s business: Daniel did not isolate himself from the culture around him but continued faithfully in his service of Babylonian society.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 9:1–27 Daniel’s Prayer and Its Answer. While reading Jeremiah and realizing that the “seventy years” (v. 2) are almost up, Daniel turns to God in prayer, seeking mercy for Jerusalem. The angel Gabriel (v. 21) appears to him and explains that another period of 70 “sevens” is at hand for God’s people. The name Yahweh (represented by LORD, in small capital letters), not used elsewhere in Daniel, is used seven times in this chapter, emphasizing God’s covenantal relationship to his people. This vision occurs in Darius’s first year (539 B.C.), about 11 years after the one in ch. 8. Daniel appears to be over 80 years old. On the identity of Darius the Mede, see note on 5:30–31.

The 70 Weeks of Daniel 9

DANIEL—NOTE ON 9:1–19 Daniel’s Prayer Concerning the 70 Years. Daniel knows why the exile came upon the Jewish people, and he confesses his own and his people’s sins and prays for forgiveness and mercy. This prayer occurred shortly after the Babylonian Empire was overthrown by the Medes and the Persians in 539 B.C., thus fulfilling the prophecy of the handwriting on the wall (cf. ch. 5).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 9:2 Daniel’s prayer was prompted by reading Jeremiah, part of the OT canon that had been collected up to that point, where he found a reference to the desolations of Jerusalem lasting for seventy years (see note on Jer. 25:11). He understood this prophecy to clearly indicate that the desolations were almost over. Some interpreters understand the 70 years to extend from 605 B.C. (cf. note on Dan. 1:1–2) to the first return of the exiles in 538, following Cyrus’s decree allowing the Jews to return. Others suggest that the 70 years extend from 586 B.C., when Nebuchadnezzar destroyed Jerusalem, to 515, when the rebuilding of the temple was completed under Zerubbabel (cf. Ezra 6:15). Jeremiah 29:10–14 suggests that at the end of the 70 years Israel will pray to God and he will hear them. This passage may suggest a time when the temple is complete and is being used to call out to God. Both interpretations are reasonable, but Daniel appears to be suggesting the first interpretation, for at the end of the 70 years Babylon would be punished (cf. Jer. 25:12), which fits well with the events of 539 B.C., and God’s people would return home (cf. Jer. 29:10).

DANIEL—NOTE ON 9:3 Since God was judging the king of Babylon and his nation, as promised (cf. Jer. 25:12), Daniel began to pray for the gracious restoration of God’s people to his land (cf. Jer. 29:10). Along with praying, Daniel fasted and clothed himself in sackcloth and ashes, signs of intense mourning and repentance for his people’s sin.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 9:4 Daniel’s prayer begins with adoration and an acknowledgment of God’s power and his justice, and goes on to plead with him to show his grace to his people. The Lord is a God who keeps covenant and steadfast love, faithfully fulfilling his promises to his people. In contrast to God’s righteousness and faithfulness, Daniel’s own people had been unfaithful, as Daniel confessed.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 9:11 Under the terms of the covenant God established at Mount Sinai, such unfaithfulness as Daniel confesses to in vv. 5–11 of his prayer would result in the destruction and exile of God’s people from the Land of Promise: the curse and oath that are written in the Law of Moses refers to Lev. 26:14–45 and Deut. 28:15–68. Yet Deuteronomy also speaks of the promise of a new and gracious beginning for Israel beyond sin and judgment. When his people repented of their sins, the Lord would gather them again to the land (Deut. 30:2–3), which was Daniel’s hope.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 9:17 Daniel asked God to show favor and make his face to shine upon his desolate sanctuary and bring the exile to an end because of God’s commitment to his own sake—the glory of his own name.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 9:20–27 Gabriel’s Answer: 70 Sevens Before the Promised Redemption. The angel Gabriel, first seen in ch. 8, hastens to Daniel and reveals that there is more to come.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 9:21 In response to his prayer for the restoration of Jerusalem, Daniel received an angelic messenger, Gabriel, with a vision for him. Gabriel’s arrival was clear proof that Daniel’s prayer had been heard and his request for favor had been honored by the Lord (v. 23).

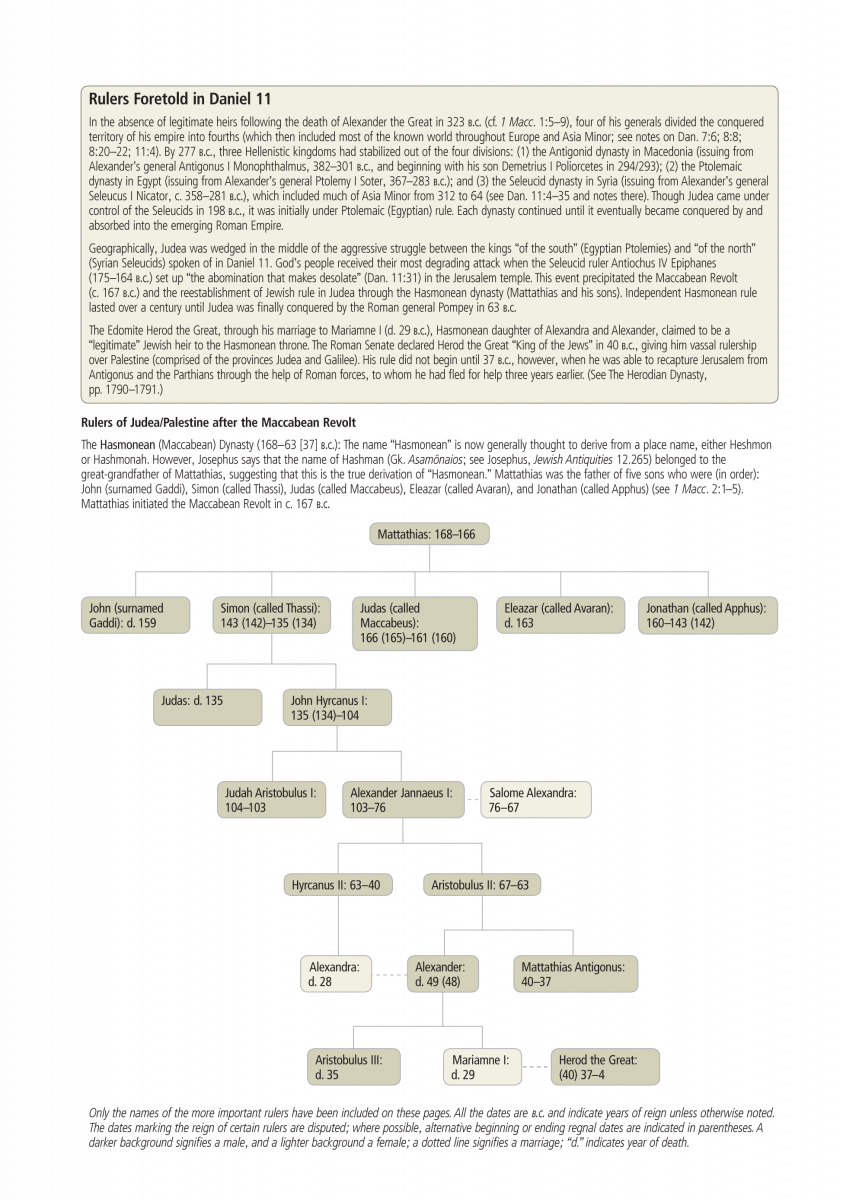

DANIEL—NOTE ON 9:24–27 There are many suggested interpretations of the seventy weeks (or “seventy sevens,” see esv footnote), but there are three main views: (1) the passage refers to events surrounding Antiochus IV Epiphanes (175–164 B.C.); (2) the 70 sevens are to be understood figuratively; and (3) the passage refers to events around the time of Christ. Most scholars understand the 70 “sevens” to be made up of 70 times seven years, or 490 years, but they apply these years to different periods of time. (See chart.) In any case, the important point is that God has appointed the amount of time, and thus his people should not lose heart.

(1) Those who hold the first view often understand the word to restore and build Jerusalem (v. 25) to allude to Jeremiah’s prophecy of the “seventy years of captivity” (Jer. 25:1, 11), which began in 605 B.C. (or some start at 586, when the Babylonians destroyed the temple) and extended to the cleansing of the temple by Judas Maccabeus (164) or the death of Antiochus IV Epiphanes (164). These solutions give only an approximate fulfillment for the “seventy weeks” (since 490 years after 605 is 115 B.C., and 490 years after 586 is 96 B.C.). An objection to this view is that it is hard to see how the events around Antiochus IV could fulfill the purpose for the “seventy weeks” (such as, “to finish the transgression,” to make “an end to sin,” “to bring in everlasting righteousness”).

(2) Scholars who hold the second view believe the 490 years (7 + 62 + 1, each multiplied by seven years) to be symbolic periods of time ending in the first century A.D. Support for finding symbolism here comes from the mention of “seventy” in Dan. 9:2, and the connection of “seven” to the weekly Sabbath (Lev. 23:3), to the Feast of Weeks (Lev. 23:11–16, “seven weeks”), to the sabbatical year (Lev. 25:3–4, connected to discipline of the people in Lev. 26:34–35; 2 Chron. 36:21), and to the Jubilee year (Lev. 25:8, “seven weeks/Sabbaths of years”). These numbers can therefore imply God’s perfect appointment of time. One approach for this second view is simply to say that 70 x 7 symbolizes the ultimate in completeness, and no further specificity is implied. Another approach is to see three broad periods, with the first period of seven sevens extending from Cyrus’s decree allowing the Jews to return and build the temple (538 B.C.) to about the time of Ezra and Nehemiah in the fifth century (c. 458–433). Then the 62 weeks extends from about 400 B.C. to the advent of Christ. The last “seven” goes from the first advent of Christ to sometime after his death, but before the destruction of Jerusalem in A.D. 70. An argument against this view is that the enumeration of 7 + 62 + 1 weeks seems to be intended to give a much more precise chronology rather than just a sequence of three periods of history. In addition, the purposes for the 70 weeks do not appear to be fulfilled in A.D. 70 (“to finish transgression,” “to put an end to sin,” and “to bring in everlasting righteousness”). Some interpreters who hold a symbolic view have suggested it refers to periods of time ending with Christ’s second coming, which would answer this last objection.

(3) The third view sees the “seventy sevens” as a literal period of 490 years, culminating around the time of Christ. But what starting date can be used for this? (a) The starting date for this period of time is not likely to be 538 B.C., when Cyrus gave permission for the Jews to return to Jerusalem and rebuild the temple (2 Chron. 36:23; Ezra 1:2–4), for that was not a decree to build the city, and 490 years from 538 yields 48 B.C., a date of no great significance. (b) One reasonable possibility is the decree of Artaxerxes in Ezra 7:12–26, which occurred in 458 B.C. (see note on Ezra 7:6–7). Though this decree still has much to do with provisions for the temple, it makes provision for “magistrates and judges” (Ezra 7:25) and thus assumes rebuilding of a city would take place. And 490 years after 458 B.C. is exactly A.D. 33, the most likely date of the crucifixion of Christ. (See article on The Date of Jesus’ Crucifixion.) (458 + 33 = 491, but one year must be subtracted since there was no year 0, so from 458 B.C. to A.D. 33 is exactly 490 years, or “seventy sevens.”) This calculation also fits Dan. 9:24, for Christ’s death accomplished the things mentioned there as what would be done in the 70 weeks: “to finish the transgression, to put an end to sin, and to atone for iniquity, to bring in everlasting righteousness.” Possibly a better understanding of this interpretation is that the 7 + 62 = 69 weeks in v. 25 brings us to A.D. 26, and some NT scholars think that Jesus began his ministry in A.D. 26 and died in 30. But v. 26 simply says, “After the sixty-two weeks, an anointed one shall be cut off and shall have nothing,” and in this interpretation Jesus’ death did occur shortly after the 62 weeks. (This understanding of the verse allows for Jesus’ death in either A.D. 30 or 33.) (c) A third possibility for the start of the 490 years is 445 B.C., when Artaxerxes gave letters to Nehemiah authorizing him to rebuild the wall and to build a home in Jerusalem (Neh. 2:5–8; cf. Neh. 2:1 for the date, 13 years after Ezra 7:7). But 490 years after 445 B.C. gives A.D. 46, a date well beyond the crucifixion of Christ. An alternative to this view is to see Christ’s death occurring in the sixty-ninth week, which would be A.D. 39, but that is still too late. However, some interpreters argue that a “year” in this prophecy should be calculated at 12 months x 30 days = 360 days (cf. Dan. 12:7, 11; Rev. 11:2; 12:6). On that basis, 69 “weeks” of such years equals 483 years of 360 days, and that comes out to A.D. 32 or 33, depending on whether Artaxerxes’ letter in Neh. 2:5–8 is dated 445 or 444 B.C. It is difficult to decide among these alternatives.

An additional question is whether Daniel’s prophecy allows for a gap between the sixty-ninth and seventieth weeks. Dispensational interpreters understand Dan. 9:26 to allow for the entire church age, and v. 27 to describe the seventieth week, which includes the seven-year great tribulation and the appearance of the Antichrist. Dispensationalists argue that Daniel’s vision appears to be dealing primarily with the events regarding the nation of Israel, not the Gentiles. Other interpreters have thought that no such gap is implied by Daniel’s words.

There are many difficulties in deciding between these interpretations, which also involve questions of the proper approach to interpreting biblical prophecy. In all of this it is crucial not to miss Daniel’s message for his audience, namely, that God has allotted the amount of time for these events, and therefore his people should trust and endure.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 9:24 Gabriel’s message was that Daniel’s requests for a transformation in the state of his people and city would be answered. The very year of Daniel’s request (cf. v. 1 with 2 Chron. 36:23; Ezra 1:2–4) would be the initial end of the desolations of Jerusalem, for Cyrus fulfilled this when he allowed God’s people to return home. But Gabriel surpasses that event and explains when the ultimate desolations of Jerusalem would be over. The transgression, sin, and iniquity of Israel that had led to their abandonment by God (Dan. 9:7) would ultimately be atoned for. God would bring everlasting righteousness, making his people into a holy nation. Because of the past neglect of the words of the prophets by his people (v. 6), the Lord would seal their words as an ancient document writer might seal a letter. God would stamp the words of the prophets as authentic expressions of his mind through their fulfillment. To anoint a most holy place might refer to the sanctuary in Jerusalem and its reconsecration by Judas Maccabeus in 164 B.C., or to the “anointing” of the heavenly “most holy place” by Christ when he died (cf. Heb. 9:11–14, 23–24); some even take it as the anointing of a future temple, according to their reading of Ezekiel 40–48. The Lord was committed to bring in the promised new covenant of Jer. 31:31–33. However, this promised new covenant would not arrive at the end of the 70 years of the exile. That period of judgment was a small part of a larger plan of God, which would take seventy weeks (or “sevens,” esv footnote) rather than 70 years to work itself out.

DANIEL—NOTE ON 9:25–26 The promised restoration of God’s people and sanctuary would come in three stages. (See note on vv. 24–27 for various views of the actual dates.) The first seven sevens would run from the issuing of the decree to restore and rebuild Jerusalem to the time when that rebuilding was complete (perhaps 458–409 B.C., or 445–396). This period of restoration, along with the subsequent sixty-two sevens after the city had been rebuilt, would be a time of trouble. The messianic ruler would make his appearance at the end of these 69 sevens. Even the appearing of this anointed one, a prince, would not immediately usher in the peace and righteousness that Jeremiah anticipated. Instead, the anointed one (Hb. mashiakh, from which “Messiah” is derived) would himself be cut off (v. 26), leaving him with nothing, surely a reference to the crucifixion of Christ. After the cutting off of the anointed one, the people of the prince (Hb. nagid) who is to come would destroy Jerusalem and its sanctuary. Many commentators understand this “coming prince” as a reference to the Roman general Titus, whose army destroyed Jerusalem in A.D. 70, or as a reference to a future antichrist. Other interpreters understand this prince to be the same “anointed prince” (Hb. mashiakh nagid) anticipated in v. 25. This person is addressed as “anointed one,” where the focus is on his priestly work of offering himself as a sacrifice, and as a “ruler” whose people fail to submit to his rule. The principal cause of the destruction of the city and temple of Jerusalem in A.D. 70 was the transgression of God’s people in rejecting the Messiah that God had sent to them (Luke 19:41–44).