If any building embodies Louis Sullivan’s principle that form follows function, it is the theater…. No American architect, not even Louis Sullivan, was predisposed to experiment with the interior arrangement of the playhouse.

One of the best-kept secrets in the theatre is the frequency with which architectural design totally frustrates the intentions of artists for whom such work is ostensibly undertaken. It is one of the theatre’s greatest ironies that those who design its stages and auditoria, no matter how distinguished they may be as architects, are very often baboons when it comes to creating a space in which actors and audiences can happily cohabit.

Performance spaces, once built, tend to outlast their creators. Miscalculations made in one generation may haunt the users of the facilities through many subsequent generations.

For fifty years our theatre has been steadily and slowly working over from the bizarre operatic structure set upon the drama of Europe by the bursting luxuriance of seventeenth century Italian courts towards a reticent auditorium which should display, upon an illusively lighted stage within a frame, a realistic representation of life. At last…we have reached a form appropriate to the purposes of the nineteenth century drama.

THE THEATER BUILDING LITERALLY HAS AN ANCIENT HISTORY, one that goes back far before anyone could even imagine the technological developments that would lead to movies for the theater. But the theater building as an architectural form also has a varied history. On the face of it, the function of live theater would seem to dictate a specific use of space as much as film theater does: the very nature of the event requires a performing area and a viewing area. But in live theater this requirement is even more indefinite than with film since performing and viewing areas may, in fact, occupy the same space. I have begun this chapter with a colloquy of four voices to suggest the following: the function of live theater might always be clear, as theater historian Mary Henderson has it, but only if we define theatrical function in the most generalizing way of spectators encountering performers. If the function were so simple, how could so many “distinguished” architects become baboons as dramatist-director Charles Marowitz claimed in 1997? Clearly, Henderson’s understanding of function, based on a fairly restricted notion of theater, is too vague to imply, let alone dictate architectural form.

But if the nature of the theatrical entertainment were more specifically defined—with possibilities ranging from, say, the circus to naturalistic drama—then function would become more varied and potentially call for a variety of forms. Further, what constitutes theatrical entertainment can change with time, as is very much the case with the appearance of motion pictures within late-nineteenth-century theaters. Such changes can give rise to the “miscalculations” of past theater architecture surviving long after the original designers, as architect Martin Bloom has it. Although Bloom has in mind flaws inherent in the original design, miscalculation can also mean a past function for theatrical space that no longer conforms to current practice, a change in performance style that earlier architects could not have anticipated. This problem of a mismatch between architecture and staging is evident in stage and film producer Kenneth Macgowan’s ironic praise for contemporary theater architecture finally arriving in 1921 at a form appropriate to dramatic styles of the previous century, an irony lost on us if we are not aware of the changes taking place in the most advanced theater productions when Macgowan wrote this, an irony that should be apparent from the book’s title, The Theatre of Tomorrow.

In the United States, motion pictures first appeared in theatrical spaces designed for other purposes. My concern in this chapter is with how well motion pictures actually fit within those spaces and, complementarily, the extent to which those spaces helped condition an understanding of motion pictures. Crucial to this consideration is an understanding of the function of theatrical space, an understanding that does in fact change with history, even if we limit theater to mean a dramatic form usually centered on a preexisting text. The function of the spaces in which movies first appeared in 1896 has a precise historical determination. To complicate matters, the understanding of the function of theatrical space was itself undergoing a change in precisely this period, with changes in staging practices and the audience-performer relationship. Following up on his ironic praise for the new theater architecture, Macgowan notes isolated exceptions of the previous century that were becoming more of a trend at the time of his writing: “For a hundred years scattered artists, architects and directors have been fighting both the court opera house and the modern peep-show theatre in an endeavor to create still another form of playhouse—a structure neither as absurd as the opera house nor as limiting as the picture frame stage…a theatre for the future as well as the past; a theatre for the drama that grows tired of the limitations of realism” (186–87). In Macgowan’s formulation, theater architecture effectively expresses a preference for kinds of staging as well as kinds of drama, so, for example, the “picture frame stage” evinces a preference for realistic staging. Taking a cue from Macgowan, then, I would like to reverse Sullivan’s familiar dictum and use form as a means to arrive at function.

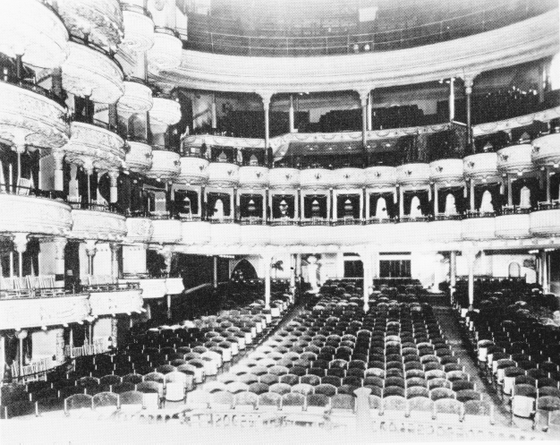

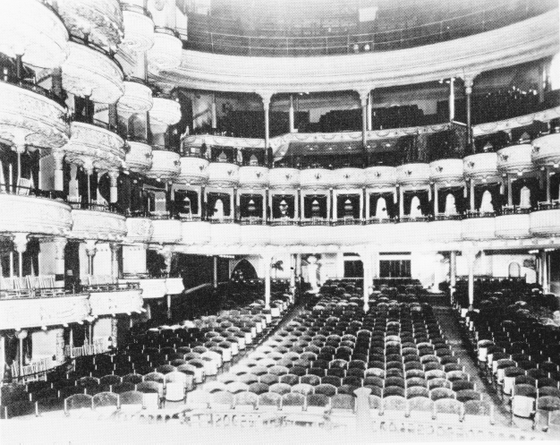

Let me begin with Sullivan himself by considering the Dankmar Adler–Louis Sullivan Auditorium Theatre in Chicago (1889), “the most important and influential theater building of the nineteenth century after Bayreuth Festspielhaus,” a building roughly contemporaneous with the invention of cinema and possibly an influence on subsequent movie palace architecture.5 There are a number of striking features in the design of this building that we are no longer likely to see in a new theater: side boxes, which were perpendicular to the hall, not facing the stage; an arrangement that allowed covering the orchestra seats with wood planking; and, finally, one of its most innovative architectural features, “hinged ceiling plates, which could be lowered to close off two upper balconies.”6 What precisely was the theatrical function of these architectural forms?

The first two items actually had little to do with theatrical entertainment. Of the man who commissioned the building, Sullivan wrote, “he wished to give birth to a great hall within which the multitude might gather for all sorts of purposes, including grand opera.”7 “All sorts of purposes” might well be an understatement since the first use to which the hall was put, a year before its formal opening, was the 1888 Republican National Convention. After the space officially opened as a theater, it also functioned as a concert hall for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, which made the Auditorium its home until it moved to a dedicated concert hall in 1904. In both these cases the side boxes that did not directly face the stage could make sense: facing the orchestra is not necessary for a concert, while facing the interior could make sense for a convention. Covering the orchestra seats with wood planking was necessary for the convention as well, but it also allowed for the possibility of gala balls, which were indeed held in this theater. The one item here that actually has to do with theater was the hinged ceiling since it allowed for “reducing capacity to about twenty-five hundred for dramatic presentations.” At the time of its construction, the theater “was designed to seat over forty-two hundred for operatic, choral, or orchestra performances.”8 As an architectural matter, then, “dramatic presentations” clearly stood in opposition to these other entertainments and called for a different kind of architectural space. The different configuration of space should provide insight into contemporary understanding of, say, the function of grand opera as different from that of dramatic presentations.

Writing of the move toward “the large, pictorial, and essentially Romantic style of stage production” in the nineteenth century, theater historian Donald C. Mullin has observed, “Whether the design change dictated by fashion influenced playwrights or whether the changes in dramatic entertainments ran parallel to those in architectural practice is not clear.”9 Architectural space will inevitably place constraints on what may be exhibited within it, but to what extent may performance determine architectural space? At the beginnings of Western theater there seems to have been a fairly direct connection between theater design and performance. In the enormous outdoor theaters of ancient Greece, performance space was contiguous with audience space, with both performers and audience utilizing the same paradoi, the walkways to enter seating and performing areas.10 The consequent emphasis on theater as communal experience, with playing and seating areas constituting a continuous space, finds its literary reflection of community in the onstage chorus. Further, the very size of the theaters necessitated the use of masks with built-in miniature megaphones and something like platform shoes for all performers to make them more visible and audible to the widely scattered audience. This, in turn, had to have an impact on the way the plays were written.11 Still, these were structures that were being erected at the same time as the plays being written for them. In later centuries, however, economics could be as important a factor in determining architectural form as theatrical function, most especially in theaters built on speculation in a commercial market.

For example, the advent of the unroofed theaters in Elizabethan England staged dramas within structures “undoubtedly derived from the bull and bear baiting yards.”12 The reason for the architecture was both economic and political, “so that the buildings could readily be adapted to gaming houses should their use for plays be restricted at any time by the authorities, thus insuring the owners against loss by the multi-purpose nature of their building design” (ibid.). Would the design have been different had the sole function been presentation of plays? The design of contemporaneous interior court theaters, based on a rectangle, was certainly different, so it seems likely the rectangular shape could have provided a model for unroofed theaters as well, one that might look more familiar to us. But the court theater did not face the economic constraints of the commercial theaters. The resulting dual-purpose architecture of the unroofed theater consequently acted as a limiting factor on how plays were presented, its circular form requiring a platform that extended from one end of the circle toward its center. At the least, there could be no question of extensive scenery, which is why Shakespeare’s plays often call upon our imaginations to provide settings for the staged action. Further, the extremely varied views of the performing area created by the circular shape were certainly a factor in determining a style of playwriting that favored the expressivity of language over spectacle.13

Architecture, then, could affect the composition of a play, and I will argue in later chapters that it would eventually have an impact on film production as well. But in its earliest appearance in a theater, film might seem more of an immutable object that merely had to be fit within an existing space willy-nilly, not able to change in any fundamental way as staging practices in live theater could change in response to architecture. Nevertheless, how the film image was presented to an audience within a given architectural space turns out to have required a good deal of forethought and could be surprisingly varied, even in its earliest exhibition. This is to say that the theaters themselves did affect how the first motion pictures were perceived by the American public, literally in terms of how the screen was spatially located in relation to the spectators. But there was also a metaphorical meaning fostered by the connotations of the theatrical space as well as the manner of presentation, both in theatrical format and in issues of staging, which inevitably invoked other theatrical presentations.

Once a theater is built, the very expense of its construction makes tearing it down the last option to allow for any novelty in theatrical presentation. For this reason, architecture is generally the most conservative element of theater. As economic necessity determined the form of the Elizabethan theater, it also determined the venue for motion picture exhibition: the sense that cinema might be little more than a novelty as well as the very brevity of the films themselves could not warrant new structures. Further, as much as motion pictures were a novelty, they also operated within a context of visual novelties that were a striking feature of nineteenth-century entertainments, not least of which was the development of photography itself.14 I want to look at two that had strong associations with theater and may be seen as precursors of the motion picture: panoramic paintings and tableaux vivants. Both appeared in a period that seemed to increasingly value illusionism, both paralleled each other in periods of popularity, and both were effectively supplanted by motion pictures as a popular entertainment. Finally, each allows us to consider how an illusionist object would depend upon a specific architectural space to create its illusion. Panoramic paintings with their trompe l’oeil ambitions aimed at fooling the eye into accepting pictorial representation as reality are of interest because they required special buildings that looked nothing like conventional theaters, and yet they were seen as theatrical entertainments and ultimately did have a direct impact on theater practice.15

First popular in the late eighteenth century, panorama painting saw a major revival in the few decades preceding the first exhibition of motion pictures. In both periods, the panorama painting brought with it the dedicated buildings of the earlier period. These buildings could seem at an extreme remove from theater buildings: spectators were led up a stairway to a central viewing platform where they found themselves surrounded by a wraparound painting. But even if the buildings themselves did not provide an architectural connection to conventional theater, the paintings were viewed as a form of theatrical entertainment: for example, a 1903 historical survey of the “New York Stage” lists “The Colosseum,” a building which opened in 1874 specifically to display a panorama painting, “London by Day.”16 This painting was enormously successful for three months, after which time, much as a new play might open, a new painting, “Paris by Night,” was installed. When business fell off (reportedly because of competition from P. T. Barnum’s circus at the Hippodrome, the cavernous space that would become the first Madison Square Garden), the show closed and the building was taken down.17 Similarly, the panoramic painting “The Battle of Gettysburg” was exhibited in a special building, “The Cyclorama.” As plays in this period would travel to different cities, the painting was moved to Washington, D.C., after a two year run; subsequent paintings of “The Falls of Niagara” and “The Destruction of Babylon” carried through to the 1893–94 season.18

Finally, if not actual theater itself, panorama painting had a direct impact on theatrical practice in two ways.19 After the first period of popularity, moving panoramas (paintings of great width that moved by being wound along two rollers) began to be used in stage productions in the 1820s.20 Subsequently, the moving panorama effectively bridged the connection between the panorama painting and the stage theater and had a direct influence on late-nineteenth-century scenography: “The moving-panorama backdrop became an indispensable part of nineteenth-century theatrical productions, whereby it should be noted that it was panorama painting that influenced stage design and not the other way around.”21 Along with the moving panorama, the 360-degree panorama painting had an impact on late-nineteenth-century scenography because the painting had to be staged for its illusion to work: the building guaranteed that the viewer stood in the center of the painting so that it became the entire environment and at a sufficient distance from the painting to ensure its illusion. The distance also provided the possibility for creating an environment in front of the painting with three-dimensional objects that would enhance the painting’s realism.22 The first use of the manufactured environment dates to a Frenchman, Jean Charles Langlois, for a rotunda he built in Paris in 1831: “between the viewing-platform and the canvas he introduced a faux terrain—three dimensional scenery which blended with the picture on the canvas. When organized skillfully it would be impossible for spectators to tell where three-dimensional elements ended and two-dimensional canvas commenced. For Langlois’ first panorama, ‘The Battle of Navarino,’ he purchased a ship that had distinguished itself in the engagement—the Scorpio—and incorporated a section of it into the rotunda” (Hyde, 59). The use of a portion of an actual ship anticipates the kind of large-scale illusionism that characterized nineteenth-century spectacle theaters.

With the panorama revival in the 1870s, “The faux terrains became as important as the paintings themselves” (Hyde, 169), a shift in emphasis that was significant for live theater, reflecting a change in the pictorial theater itself. Their direct impact on theatrical staging is evidenced by an 1881 observation cited by theater historian Martin Meisel: “A new system of scenery has lately been introduced in pieces like ‘Michael Strogoff’ (1871) which consists of grouping living persons and bits of still life with pictorial background into a picture. This is borrowed from the panora-mas.”23 Meisel considers this development a “late achievement of a fully pictorial theater, in which actor and crowds were fused with the setting in a sustained and atmospheric unity” (44). As such, this “innovation” not only anticipates the move toward more fully three-dimensional scenography in the theater but also presages the combination of film image with built sets that I will discuss in chapter 5. These changes in set design would eventually lead to changes in theater architecture. Still, they were possible to employ within existing theaters. On the other hand, panorama paintings required a very precisely determined space to achieve their effect, and single-purpose buildings were economically limiting: when the panorama’s popularity declined, the buildings were demolished.

Something as novel as motion pictures could well have called for a distinctive building type, as did panoramas. And something like this did in fact happen with some early attempts to combine motion pictures with panoramic exhibition in buildings erected for this purpose.24 Within a decade, after they clearly established themselves as a lasting primary attraction, motion pictures would find their own buildings, but in the interval, the panorama buildings could serve as a warning: movies could prove to be a transient fad like panoramas. Further, the motion picture image could be more easily made to fit within existing spaces because it did not place the same kind of constraints on architecture as panoramic painting. Since the motion picture was an object that could be exhibited to large groups of people at any time and seemingly at any place that could be suitably darkened, the theater might well seem to be the most obvious choice among existing spaces.

Must movies be shown in theaters? Before the age of television, the very technology would seem to require the elaboration of a theatrical space for exhibition. But the earliest showings of motion pictures in the United States were in arcades rather than theaters, and it was something of a solitary experience, with individuals watching the film through a viewer like Thomas Edison’s Kinetoscope. The technology was fairly simple, relying on the viewer for energy, and celluloid could be dispensed with entirely, as with the Mutoscope machine that flipped cards of still photographs. Edison himself had only made “half-hearted efforts to develop a projecting machine,” and so the apparatus his company put out under the Edison name was invented by others, Thomas Armat and C. Frances Jenkins.25 In France, the Lumière brothers from the outset seem to have regarded their development of motion pictures as something to be exhibited in a public space, although not necessarily a theater per se: the first showing of their cinématographe was at a June 1895 scientific conference in Lyons, with the setting clearly influencing the kinds of film shown. This was perhaps most obvious in the case of footage which showed attendees of the conference to themselves shown on the very day the film had been shot, a presentation which stressed the marvelous in this scientific marvel by transforming time and space.26 A subsequent showing in Paris led the Lumières to plan for a New York opening. It was only the promise of the New York cinématographe premiere that led the sales agents for Edison’s Kinetoscope to prompt Edison to move his moving images onto a screen and into a theater.

As the Lumiére exhibition makes clear, a theater need not have been the inevitable choice for first-time exhibition in the United States. Since the Kinetoscope presented an image isolated in a spatial void, the invention of the motion picture not only did not presuppose a specifically theatrical space, it seemed to exist outside of architectural space entirely. Displacing the image from an individual viewing machine filled in that void, providing a specific context for the image that had to impact on a sense of the image itself. What kinds of places were available for exhibiting motion pictures in the United States? At the time motion pictures moved into theaters, the most obvious possibilities were the opera house, the vaudeville theater or music hall, and the straight dramatic theater. To this, I should add the lecture hall as a possible space since it was precisely a lecture hall within a New York wax museum, the Eden Musée, which began showing films in late December 1897 and provided cinema with one of its most important early venues in the United States. But this does not offer an architectural departure since the shape of this lecture hall reflected dominant styles in theater architecture of the period.

As far as theaters go, generally, the opera house and the vaudeville theater were among the largest theaters in a given city, with the great space of the auditorium considered appropriate to spectacle-oriented performances. This is not to say that straight plays were never given in opera houses or music halls, but the general orientation of these theaters was toward spectacle.27 Although this distinction between spectacle theaters and dramatic theaters would prove important for motion picture exhibition with the advent of the feature film in the teens, initially motion pictures found their home in spectacle-oriented vaudeville theaters. The kinds of movies being produced at the time could, in fact, fit easily into a vaudeville theater because they could conform to the aesthetic purpose of the overall program.28 Since early films ran less than a minute, vaudeville, itself presenting a series of discrete performances, offered a theatrical context that could accommodate a modular presentation. This is to say that early motion picture presentations effectively echoed this modular form in miniature, in the process helping to define variety as an important aspect of movie exhibition.

The choice of vaudeville theaters for the first showing of motion pictures in the United States, and especially the specific vaudeville theater Koster and Bial’s Music Hall, seems overdetermined in retrospect, something that grew out of the films themselves. Many of the short films that the Edison company had made for use in the solitary viewing machine, the Kinetoscope, featured vaudeville stars who had been filmed in excerpts from their acts at Edison’s New Jersey studio. The use of vaudeville acts, some of which had appeared at Koster and Bial’s, in fact, would seem to inscribe motion pictures as an extension of vaudeville in contrast to the initial demonstration of the Lumière films in Paris.29 Furthermore, film historian Robert Allen has argued that motion pictures fit very neatly into vaudeville because visual entertainments had a fixed place in the standard vaudeville bill: “the endless procession of visual novelties…were always an important part of vaudeville. Vaudeville absorbed, in slightly altered form, both melodrama and pantomime, and provided a forum for several other pre-cinematic novelties, the popularity of most of which reach a high point on the eve of the introduction of the movies” (Allen, 52).

The Vitascope fell in line with previous music hall pictorial presentations in one very specific way: “Kilanyi’s Glyptorama” premiered at Koster and Bial’s in December 1895 and ran pretty much until the Vitascope premiere in April 1896. The Glyptorama was a mechanized variation on “living pictures,” an entertainment which “rose to a pinnacle of popularity at the close of the nineteenth century, with numerous productions competing for public favor in New York’s major variety theatres” and “a remarkable variety of tableau acts in the United States.”30 Living pictures consisted of “live models [who] represented static scenes from painting, sculpture, and other sources. Through elaborate stagecraft, these scenes were made to appear as much like the original work as possible” (McCullough, 25). As an entertainment they could fit very neatly into a vaudeville show because even when they were presented as part of the entertainment in a legitimate play, they worked like a mini-vaudeville show in themselves: a series of individual “acts,” most recalling a familiar artwork, but otherwise generally unrelated, and seemingly chosen for their variety, ranging from comic to pastoral to spectacular to religious to melodramatic.31 Edward Kilanyi, a German producer who had begun his career as a scene painter, had previously toured with a troupe to present “living tableaux” in Germany, France, Spain, and England; his performances in London set off a fad for tableaux at variety theaters. He subsequently brought them to the United States, first as intermission entertainment for a dramatic stage performance, a “burlesque” entitled 1492; the entr’acte was called “Queen Isabella’s Art Gallery,” with the women outnumbering men since the basis in famous artworks allowed hints of nudity that were a prime attraction of the entertainment. The great success of this entr’acte had an effect comparable to his London showing, leading to a competition at vaudeville theaters, first with a series of “Living Pictures” “devised” by Oscar Hammerstein which premiered at Koster and Bial’s in May 1894, where they “proved a genuine hit,” leading to tableaux vivants shows at Proctor’s in New York and in Boston among other cities; Kilanyi responded with a new series of living pictures for the 1492 entr’acte.32 For contemporary audiences the early uses of motion pictures had to suggest a parallel with living pictures: both functioned as an act in a vaudeville show, where they presented a series of discrete views, and both were used as entr’acte entertainment in stage dramas, with motion pictures eventually usurping tableaux vivants in both instances.33 Perhaps the most obvious connection between the two for contemporary observers was signaled by terminology: early motion pictures were occasionally referred to as “living pictures.”

In the competitive climate that began to emerge around living pictures, the Glyptorama sought to distinguish itself by a novelty that conjoined them to machinery, making use of the moving panorama, which, as noted above, had become a common device in theaters of the time. With this addition of mechanical movement, the Glyptorama effectively carried living pictures in the direction of motion pictures, making the premiere of the Vitascope in retrospect a logical successor, one that would eventually displace the Glyptorama itself. It was the practice in earlier living picture entertainments to draw a curtain between individual tableaux as a way of both concealing the change to a new picture and heightening the illusion of stillness in each tableau. The Glyptorama countered this discreteness with a flow from one “picture” to the next, maintaining a continuous visual field by mechanically moving already staged models into position as the new background unrolled behind them on a moving panorama. This shift from concealment to revelation was no modernist avant la lettre “baring of the device”: the 20-foot-wide stage picture set in a proscenium 42 feet wide was surrounded by a black drop curtain to hide the elaborate mechanism required for the movement. Not being able to see how the change was managed made the transformation itself seem marvelous, as marvelous as the rendering of a flat object in three dimensions by living subjects. The Glyptorama thus heightened a paradox inherent in living pictures, itself a paradoxical term, by simultaneously setting the movement of real-life foreground and painted background against the stillness of the posed figures.34 It also set the three-dimensionality of the performers and props against the flatness of a painted background, although the distance from the audience might have lessened this difference.

This opposition between movement and stillness would be further underscored by the occasional movement of inanimate objects or change of lighting effects within the picture. For example, in response to a picture entitled “The Deluge,” a reviewer remarked, “the light and scenic effects were superb, and the real rain, falling upon the six shapely maidens grouped on the mountain top, in all sorts of picturesque attitudes, was a triumph of stage realism.”35 This was, however, a very odd realism because the only living beings on the stage held the stillness of inanimate objects, while the inanimate objects themselves moved; the realism, then, was actually in the setting and the illusions created by lighting effects and “real rain,” which, of course, was not real at all. As we will see, setting had become a crucial defining feature for stage realism in this period, a notion that in turn had an impact on the early reception of motion pictures. While the stillness of the human figure in living pictures was remarkable because it made a familiar painting or statue (sources for individual pictures were always listed in the program) seem as if it were about to spring to life, the illusion and realism of motion pictures worked in an opposite direction, taking something frozen and magically granting it movement. In this regard, consider the early Lumière showings, which would always begin with a single frame that would then slowly transform into lifelike motion as the projectionist move the hand-cranked machines up to full speed.36 The stillness of living pictures is effectively a freezing of time: the image made up of real people looks as if it should spring to life at any moment, and yet it does not. Time stands still. As such, motion pictures effectively resolved the tension implicit in living pictures by adding a temporal dimension to the realistic pictorial representation.

The fate of the Glyptorama offers perhaps the strongest evidence of a connection between living pictures and motion pictures in contemporary reception: “The tableau vivant reached its zenith as an independent popular entertainment during the time of Kilanyi’s flamboyant presentations. Its days were numbered, however, for within four months the Glyptorama was replaced by a new novelty, one far better equipped to satisfy the nineteenth century thirst for verisimilitude and one which became an even stronger influence upon the destiny of the theatre. This new curiosity was ‘Edison’s Vitascope,’ precursor of the cinema” (McCullough, 39).37 If early motion picture projection could seem to follow directly from the Glyptorama performance, it is likely because both invoked stereopticon shows for contemporary viewers, a visual entertainment that also proceeded through a series of discrete images. Commentary in the New York Times compared the Glyptorama to stereopticon shows—“As in the changes of slides in a stereopticon, one picture will dissolve into another”38—even dubbing the show a “stereopticon–living picture exhibit,” with the “dissolve” anticipating a key filmic device.39 Similarly, a Times review of the Vitascope premiere compared the show to a stereopticon: “a projection of his kinetoscope figures, in stereopticon fashion, upon a white sheet in a darkened hall.”40

As the successor to the Glyptorama at Koster and Bial’s, the Vitascope borrowed from both its format and its physical staging. The Glyptorama featured fourteen separate “pictures”; the actual duration of the picture was likely not much longer than a Vitascope “view” since it was held “as long as the models were able to hold their poses without moving” (McCullough, 28). Subjects ranged from “Roman Bath” to “Football,” from “Slave Market” to “The Bay of Naples.” The Vitascope premiere at Koster and Bial’s also consisted of a series of briefly glimpsed pictures with “twelve views” listed in the program, although in the end only six were shown at the premiere (albeit multiple times as the brief films were set up on the projector in a loop). As with the Glyptorama, variety was an object of the programming, with subjects ranging from dancers to a seaside setting, from a burlesque boxing match to “a comic allegory called ‘The Monroe Doctrine’” to a scene from a familiar farce.41 One of the short films, the burlesque boxing match, was excerpted from the play 1492, which had provided the first American showing for Kilyani’s living pictures and set off the craze.

If variety was a defining feature of both the Glyptorama and Vitascope programs, from these initial showings a concern with variety would attach itself to motion pictures as if it represented an essential quality. But this was not just a variety of subject matter: perhaps the salience of the Glyptorama for movies lay in its making setting a key element of variety. In a sense, the Glyptorama was something of a throwback to the earlier practice in live theater of effecting scene changes in full view of the audience, a practice that was progressively abandoned with the move toward more realistic and three-dimensional scenery, which necessitated the use of a curtain as living tableaux exhibitions did as well. But the Glyptorama made possible the visible change of an entire setting complete with three-dimensional objects, in the context of late-nineteenth-century stagecraft a seemingly magical transformation. If a rapid change of the setting could be a source of astonishment, then motion pictures had to seem even more astonishing in making change instantaneous and almost a defining feature of motion pictures. In the context of the move toward three-dimensional sets which effectively limited setting, with many realistic plays restricting their action to one elaborate set, film’s variety aesthetic would give rise to the notion that realistic plays had to be “opened up” when turned into film.

Most strikingly, the Glyptorama established a visual presentation borrowed for the Vitascope premiere. Living pictures were “usually presented on a stage or in a box-like enclosure, viewed through a large, often elaborately decorated frame, like a picture frame” (McCullough, 28). Contemporary reviews provided specifications for this frame that would be echoed in reviews of the Vitascope: “The most important production of the season so far at Koster and Bial’s took place last evening. It is called Kilanyi’s Glyptorama, and consists of a series of immense living pictures shown in a frame fourteen feet high by twenty feet wide.”42 For the living pictures, the gilt frame made sense since famous works of art were the most common source for the pictures. This was not the case for early Edison “views,” which, as I had noted, most often reproduced moments from vaudeville acts of the kind that appeared at Koster and Bial’s. Nevertheless, the manner of presentation was similar: the New York Times review of the Vitascope premiere noted, “The white screen used on the stage is framed liked a picture” (see fig. 1.1).43 A subsequent article gave the specifics: “Figures appear to be a trifle over life-size on the screen, which is about 20 by 12 feet.”44 Given the strikingly similar size of the framed “pictures” in the Glyptorama and the Vitascope, it is likely the moving pictures would recall the frozen pictures for a contemporary audience. Further, how much this reflects contemporary understanding of early motion pictures may be signaled by the fact that this manner of presentation had a lasting effect: as we will see, the image within a gilt frame became a standard way of situating the motion picture screen in the nickelodeon era.

There was one important difference in the exhibition of living pictures compared to motion pictures that can possibly help us further determine how contemporary audiences received motion pictures. Koster and Bial’s had a proscenium opening 42 feet wide, so the relatively small size of the Glyptorama frame in relation to the proscenium was likely determined by the limited sight lines, but why place it upstage at all?45 Similar to the enforced distance of panorama paintings, this location was desirable to preserve the illusions of living pictures, the uncanny representation of a preexisting object, since the greater distance would make deceptions less perceptible. So, for example, in response to the American premiere of Kilanyi’s living pictures, shown between Acts II and III of 1492, a New York Times reviewer noted that some figures “by a clever arrangement of the stage and lights were made to resemble marble sculpture closely enough to be taken for such by the naked eye from the midway seats of the orchestra and the balcony. The most notable was the ‘Venus of Milo,’ where the arms of the woman personating the armless figure were draped in sleeves of the same color and texture of the background. The illusion was so perfect as well-nigh to defy detection.’”46

The Vitascope, on the other hand, did not need distance to maintain its illusion, and so it was brought downstage to the proscenium area.47 There is nothing natural or automatic about this location for a film image: by the teens, this positioning of the screen would in fact be rejected. But in the context of the Glyptorama, the illusions offered by the Vitascope could only seem more miraculous by being moved closer to the audience; the downstage position effectively announced the superiority of the Vitascope. In the context of a vaudeville show, the downstage position also offered the advantage of having the screen function like a drop curtain behind which the next act might be prepared, and this use likely accounts for “curtain” becoming a synonym for “screen,” a usage that would last into the teens.48 Nevertheless, while downstage position was convenient for the flow of the vaudeville show, and it could serve to announce the superiority of motion pictures to both panoramic paintings and living pictures, this positioning of the screen actually created problems. Up to this point, my focus has been primarily concerned with what was on the stage of the theater, whether living pictures or photographic pictures, and how this might have impacted on the initial reception of motion pictures in a vaudeville format. But if we look more closely at theater architecture in this period, it turns out that the space of the theater was as much an issue for motion pictures as it was becoming for late-nineteenth-century staging practice. Architectural space turns out to be a crucial factor in early motion picture exhibition: how the audience was situated in relationship to the object had a profound effect on that object.

The horseshoe type of plan…is not particularly applicable to motion picture theaters, although in many theaters existing to-day this seating arrangement may be encountered. It is difficult with this type to secure proper sight lines; the seats at the extreme sides of the house receive such a distorted view of the pictures on the screen that they are practically useless…. [The “rectangular plan”] is the one most frequently found in the motion picture theater world and is the one best suited to motion pictures as a general rule. The depth, however, may be so excessive as to render vision and audibility difficult; but given a house of this type of reasonable proportions the results secured are almost certain to be satisfactory.

Architectural Forum (1917)49

In an influential study of theater architecture published the same year as the first U.S. exhibition of projected motion pictures, British architect Edwin O. Sachs articulated a relationship between spectacle and spectator that should dictate the space of the auditorium: “the planning of the theatre, especially in regard to the size of the auditorium and the setting out of the stage, depends on the performance to be produced.”50 Although Sachs is displeased to note frequent attempts to turn different kinds of theatrical spaces into multipurpose halls, generally for him opera calls for large spaces in both auditorium and stage dimensions, where room is needed for “elaborate scenery, choruses, and ballets,” while straight drama requires a space that will place the audience in “closest touch with the actors; every gesture should be seen, every whisper heard” (4). Clearly, a similar understanding led Sullivan and Adler to devise the hinged ceiling that would reduce the size of the Auditorium Theatre. Since movies at the time did not have spoken language, they need not be subject to the size restrictions of straight dramatic theaters Sachs proposes here. And the enormous capacity of the movie palaces that began to be built in the teens was likely predicated on the initially silent status of movies. But if the average vaudeville theater was larger than dramatic theaters, how that space was configured was problematic even for silent film exhibition. Movies might have fit comfortably into the context of a vaudeville show, but the architectural space offered by vaudeville theaters of the period was an entirely different matter.

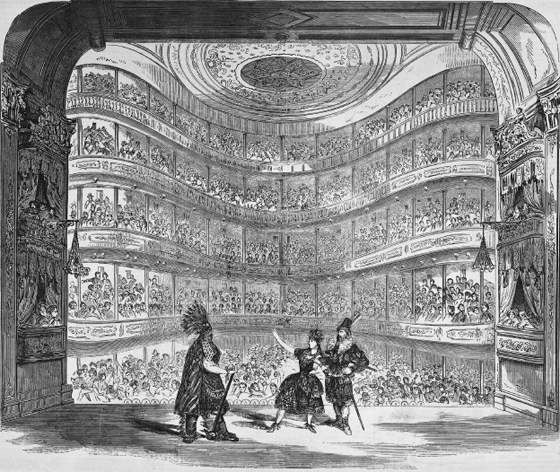

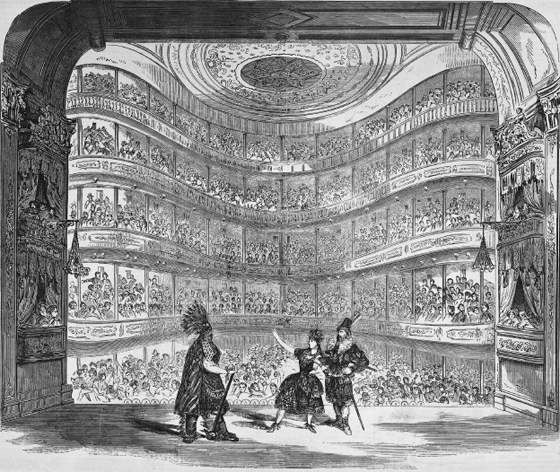

The general shape of the theaters available to motion pictures in the 1890s looked very different from the theaters that would be built for films a little over a decade later. But it was not just a matter of film-specific theaters leading to a change in architecture; by the teens and twenties, theater design for live performance was markedly different from what dominated at the turn of the century. Theater historian Donald Mullin has commented, “By 1914 the new theaters were almost unrecognizably different from those of a century before.”51 As products of nineteenth-century theater architecture, the vaudeville theaters that exhibited early motion pictures were most likely to draw on a form that was established about two centuries earlier: a roughly U-shaped auditorium facing a proscenium stage with a large apron extending in front of the proscenium. “Horseshoe” was the most common name for the seating area, but the general shape could range from a more gently curving semicircle to banks of seats on three sides of a rectangular hall (in the manner of the side boxes I had noted in the Adler-Sullivan auditorium), a form that may still be seen in some concert halls such as Symphony Hall in Boston and even as recently in the Nashville Symphony concert hall built in 2006.52 This form evolved from early indoor theaters of the seventeenth century, where the space in front of the stage could operate as a playing area for moments of spectacle, or even serve, as we saw with the Auditorium Theatre, as the dance floor for a ball.53 As action moved further back and onto a stage, seats could be placed in the orchestra, or this area could continue to be used for such spectacles as processions, masques, or dances, as they would be well into the nineteenth century. For example, a sketch of “an equestrian version of Richard III” from a London theater in 1856 shows a conventional tiered horseshoe theater but with something on the order of a circus ring in the orchestra area and, simultaneously with action on stage, action involving performers and horses in the ring.54

There were a number of advantages to the horseshoe design that kept it viable into the early twentieth century, although not all had to do with the primary function of theatrical performance. Before the advent of massive cantilevered balconies, which made it possible to build back rather than up, the stacked horseshoe rings facilitated enlarging capacity while maintaining a relatively close proximity to the stage for most viewers (fig. 1.2). From the late eighteenth century on, there seems an understanding that distance from the stage should be somewhere between 55 and 70 feet to keep dialogue intelligible. Richard Leacroft cites a Treatise on Theatres from 1790 which puts the distance at less than 75 feet, while American architect Arthur Meloy came up with the same distance in 1916: “The depth of any theatre where speaking parts are to be given should not exceed 75 ft. from the curtain line to the rear seats, as the human voice will not carry more than that distance without straining.”55 With the development of the enormous movie palaces in the teens and the twenties, building back (as well as up!) became a norm, and the palaces far exceeded these distances. They did have live performances, but they were generally connected to music so distance seemed less of an issue than it was in live drama.

There was one additional advantage to the U-shape worth noting here: it could create a greater sense of intimacy in the audience as people were arrayed in a way that made them always aware of other viewers, marking the communal nature of the theatrical experience as central to its social function.56 Conversely, the sense of display coupled with the stacked tiers emphasized separating the audience according to class distinctions; the hierarchical nature of the seating areas had a specifically class function, often reinforced by a separate entrance for the uppermost ring. Subsequent movie palaces would challenge these class divisions explicitly, but the element of display proved an advantage for the first film exhibitions: in early showings the screen itself was not the only object of interest. Because the technological novelty could itself provide spectacle, at the first showing of the Vitascope at Koster and Bial’s, the performance effectively began with the shrouded projectors as evidenced by this contemporary response: “In the center of the balcony of the big music hall is a curious object, which looks from below like the double turret of a big monitor. In front of each of it are two oblong holes. The turret is neatly covered with the blue velvet brocade which is the favorite decorative material in this house.”57 In this instance, the horseshoe shape was ideal since it allowed many viewers the possibility of dividing attention between the apparatus and the image (fig. 1.3). This practice was common enough and continued long enough that a writer in 1914 could recall “the earlier days” when projectors were usually placed in balconies and “the operators, always the center of all eyes, often wore dress suits”; the operator was called, he noted, “the professor” as if he were a character in this drama of technological progress.58 If, by 1914, there was a clear understanding that motion pictures required a different orientation between spectator and spectacle, that was in part because theater architecture itself was undergoing a marked transformation in this period, a transformation that occurred in conjunction with changes in theater lighting practices.

It is a testament to the conservative impulses of theater architecture that the horseshoe shape lasted as long as it did with little challenge because it presented problems even for live theater in creating a wide range of ways to view the stage, although some of this might be mitigated by staging practices.59 This is to say that problems with the shape of the viewing area may be directly related to staging in any given period. So, for example, as painted flats utilizing perspectival drawing came into being together with the proscenium theater, the further in front of the flats the performer appeared, the easier it was to maintain an illusion of three-dimensional space. 60 With the advent of the “picture-frame” stage in seventeenth-century Europe, “logic might seem to demand that the auditorium should adapt itself to the new requirements by making all seats face forward. This did not happen. Long after the action had retreated behind the picture frame, the seats continued to be arranged as if it were still out in front of it” (Tidworth, 72). The wide variety of viewing positions in a horseshoe theater is not a problem if actors perform primarily in the proscenium area or on the forestage in front of the proscenium, the common practice in early proscenium theaters and one that continued well into the nineteenth century, when it was still possible to find theaters with seating areas flanking the apron stage as stage boxes. The nature of the vaudeville show possibly helped keep the horseshoe form alive because much of the action could take place in the downstage area. But changes in straight dramatic performances in the late nineteenth century decisively rendered the horseshoe form old-fashioned for live drama as well in spite of its longevity up to that point. Why this was the case had to do with issues around realism for both live theater and motion pictures, but the perception of realism differed markedly in each instance. Nevertheless, realism on the stage and realism in motion pictures were oddly connected for contemporary viewers, a point I can get at by looking at reaction to the earliest film showings.

Most of all, contemporary reaction to motion pictures was struck by the reality effect, albeit in a very particular way. Charles Musser has observed about the Vitascope premiere, “as rough sea at dover dramatically demonstrated, scenes of everyday life were often greeted with much greater enthusiasm than excerpts of plays and vaudeville acts” (Emergence, 118). This was evident in the Times report on the premiere, which noted, “it was the waves tumbling in on a beach and about a stone pier that caused the spectators to cheer and to marvel most of all. Big rollers broke on the beach foam flew up high, and weakened waters poured far up the beach. Then great combers arose and pushed each other shoreward, one mounting above the other, until they seemed to fall with mighty force and all together on the shifty sand, whose yellow, receding motion could be plainly seen” (“Edison’s Latest Invention”). Although waves striking a beach would seem the most ordinary of occurrences, the writer thought it worth the most thorough and precise description, a way of conveying to his readers the wonder of what he was seeing. Certainly, the vaudeville acts and play excerpts that Edison had reproduced were familiar enough entertainment at Koster and Bial’s, so that the one piece of actual nature represented by “Rough Sea at Dover” could seem all the more novel.

The Lumière films made it to New York about two months after the Edison premiere at Koster and Bial’s and impressed viewers in a number of ways: late in the run, a note in the New York Times described them as “exhibiting moving views as real as nature’s self.”61 Lumière projection further distinguished itself by a steadier image62 and even added sound effects to heighten its reality: for “one scene representing an actual battle between two troops of cavalry,” there was a promise of “the flash of sabres, noise of guns, and all the other realistic theatrical effects.”63 One curious aspect of this description is the claim not simply of realism, but, rather, of “realistic theatrical effects” (emphasis added). This does suggest another response to the reality effect that did not see it as the latest development in a line of visual novelties that aimed to fool the eye. Rather than visual novelty, it is possible to see an evolution that placed the reality effect of the moving image in relation to aesthetic trends of late-nineteenth-century theater. This effectively pointed to a very different direction for motion pictures than the simple representation of reality. Consider the response of the well-known theater producer Charles Frohman, who had attended the Vitascope premiere:

“That settles scenery,” said Mr. Frohman. “Painted trees that do not move, waves that get up a few feet and stay there, everything in scenery we simulate on our stages will have to go. When art can make us believe that we see actual living nature, the dead things on the stage must go.” (“Edison’s Latest Invention,” emphasis added)

The most striking aspect of Frohman’s response is that he does not see movies in terms of the various ninteenth-century visual tricks, but rather immediately ties it to art and the stage: it is art that can make us believe in the reality of the image. Given his own background, it is perhaps not surprising that he immediately saw possibilities for movies in terms of theater, and indeed he himself would eventually become involved with theatrical exhibition of movies. But his connecting it to art seems to me the crucial difference here.

If the Times report is accepted, Frohman’s singling out “Rough Sea at Dover” reflects the general appreciation for this film at the premiere. But this is not necessarily what might have been anticipated prior to the first showing. In an article the Times ran in advance of the premiere, Albert Bial of Koster and Bial stated the following: “I propose to reproduce in this way at Koster and Bial’s scenes from various successful plays and operas of the season and well-known statesman and celebrities will be represented, as, for instance, making a speech or performing some important act or series of acts with which their names are identified.”64 In other words, Bial proposed having on screen what Koster and Bial’s might well be able to present onstage. If these people could in fact be seen onstage “making a speech,” would not the stage appearance be superior because we could hear as well as see? Frohman effectively answered this question in a remark that echoed Bial’s promise; the simple act of recording famous performers, even if reduced to pantomime, would be a means of preserving the performance: “And so we could have on the stage at any time any artist, dead or alive, who ever faced Mr. Edison’s invention” (emphasis added). Much as the film should have implied a someplace elsewhere, strikingly Frohman still located the action on a stage. And as wonderful as he found this possibility, he still returned to theatrical setting as the key attraction of film: “That in itself is great enough, but the possibilities of the vitascope as successor of painted scenery are illimitable” (“Edison’s Latest Invention”).65 When others were looking elsewhere, either considering the possibility of preserving a performance or enjoying the illusion of the reality effect, why did Frohman focus primarily on setting? I believe this was a consequence of both theater architecture and changing practices of staging.

Within a couple of decades of the introduction of projected motion pictures, the architectural form for live theater with frontal seating and a proscenium stage that pushed all action behind the proscenium in a box set as if behind a fourth wall, this form became dominant, replacing the previously dominant horseshoe form. So, for example, as New York’s theater district at the beginning of the twentieth century moved into Longacre Square, subsequently Times Square, virtually all of the theaters built in the teens and twenties abandoned the horseshoe, opting for frontal seating instead.66 And this form seems in large part a response to the rise of realistic drama and realistic staging.67 In general, this was a period that found increasing value in the ability to create the illusion of a three-dimensional reality on the stage, a reaction against the stylization that was inherent in painted flats.

Painted flats, the dominant mode of stage scenery in the late nineteenth century, limited the use of the stage depth, most especially if the flats drew on perspectival lines and ever diminishing objects. Put simply, painted objects could grow smaller, but actors could not as they moved into the depth of the stage. The rise of three dimensional objects and settings might have limited the implied depth of the setting, which perspectival drawing could always elongate, but realistic set design effectively expanded the playing areas onstage: actors were now free to move across the entire width and depth of the stage. An immediate consequence of this is that the setting itself began to take on greater dramatic importance. But the horseshoe theater played against the importance of the setting: in this architectural space, the downstage position, effectively divorced from the setting, would be preferred by actors for the simple reason that this position, moving out in front of the proscenium, ensured being seen by most spectators. By the time the feature film began to establish itself as a theatrical entertainment, realistic staging practices increasingly made the limitations of the horseshoe form outweigh its virtues for live theater. In The Theater of To-day, first published in 1914, Hiram Kelly Moderwell specified the limitations of contemporary theater architecture:

All of us who are obliged to take cheap seats in the theatre have realized many times that most theatres of the old style are built in utter contempt of the man with a small income. One feels that the architect thought he was doing us a favour to let us in at all. Many seats in the ordinary “horseshoe” theatre make the stage partly or wholly invisible. Very frequently the back of the balconies is so ill ventilated that the evening is torture. The acoustics of such caves are often wretched.68

The objection to acoustics here refers to the tendency to build the final balcony very deep, something that was structurally easier to do than with lower rings, creating the kind of “well” that Edwin O. Sachs writing in 1896 repeatedly objects to.69 Except for these balconies, which always contained the least expensive seats in the theater, the virtues of proximity to the stage and the individual theatergoer’s ability to see other audience members facilitated by the horseshoe design were offset by the vice of restricted views beyond the proscenium.

The horseshoe theater could not have become so prevalent and survived as long as it did had it truly produced as many bad seats as Moderwell claims: every theater but one illustrated in the three volumes of Sachs’s Modern Opera Houses and Theatres (1896) draws on the horseshoe form, and that one, the Bayreuth Festspielhaus, looked ahead to twentieth-century theater design (Sachs, 1:29). There is no comparable survey of American theaters, but the evidence is that most also employed tiered horseshoes, with the Adler-Sullivan Auditorium Theatre in Chicago cited as the first significant departure from the form.70 The fact that the horseshoe form would be so thoroughly rejected makes the timing of the shift significant. Not coincidentally Moderwell defines the “theatre of to-day” by Ibsen and other naturalist playwrights, although the first performances of Ibsen’s naturalistic plays date to the 1880s, when they were unsuccessful. By 1914 Moderwell could dismiss horseshoe theaters as “theatres of the old style” precisely because they had too many bad seats for the kind of staging that came to seem appropriate for naturalistic drama, staging that exposed the limits of the horseshoe form. What Moderwell considered the “modern” theater effectively reoriented the viewer’s relation to the stage, requiring a more frontal arrangement of seats. The change in architectural form most evident in New York’s new theater district could nevertheless be contested, but in order to do so dominant staging practices would have to be contested as well. The terms of a 1914 argument in favor of the horseshoe shape, the same year as Moderwell’s argument against old style theaters, are striking:

THE FORM OF THE THEATRE

In an interesting article in a contemporary [sic], the form of theatre design is discussed and the criticism made that the shape of our present houses is an anachronism, as it has grown up through the fact that the stage originally was pushed out into the center of the house so that an effective view could be obtained of the acting from the tiers of the curved seating, whereas at present the stage is confined within the proscenium arch. This has rendered many of the seats in the older theatres useless for purposes of seeing from, and the writer goes on to urge that the ideal form of theatre is a rectangle with the seating arranged in straight lines from side to side. The conservation of the theatrical profession, and, we gather incidentally, of the architectural profession, is, in the author’s view, to blame for this failure to recognize practical facts; but we think it must be borne in mind that the audience of many theatres go in no small measure to see the audience as well as the piece, and the traditional form of the theatre meets this requirement admirably. Then, too, in the newer theatres, modification of levels and slopes are skillfully dealt with so as to meet many of the objections to which we have referred, while the horseshoe form enables us to accommodate many in galleries without overshadowing and making the center of the house gloomy. The horseshoe form also has considerable merits acoustically over the rectangular form suggested, and brings a larger number of the audience nearer the stage, so there is another side to the question which has been overlooked by our contemporary. We very much doubt if the wedge-shaped theatre such as Bayreuth would be an improvement on the whole, with [sic] aesthetically it could not be as well treated. Perhaps the best solution would be in the adaptation of some form of apron stage, as has been tried by Mr. Granville Barker.

This is nearly forty years after Richard Wagner recognized at Bayreuth that differences in staging practice would require architectural differences as well. But rather than reject the nineteenth-century architecture as old-fashioned, like Moderwell writing the same year, the writer of this article responds by asking for new approaches to staging, which would effectively return to earlier methods.

Wagner’s Bayreuth Festspielhaus in 1876, referenced in this article, was the first strong challenge to the horseshoe design, and it was very much a response to contemporary changes in staging: featuring a wide auditorium all on one level and tiered rows of seats arranged along a gentle arc facing the stage, it provided a full view of the stage for all spectators. The importance of this theater for subsequent developments is that it makes clear the connection between staging and architecture. Wagner did not simply move action away from the proscenium area; he provided no forestage of any kind, eliminating even the possibility of performing in front to the proscenium. A double proscenium helped move the action deep into the stage, creating a deliberate distance between spectator and performance where the horseshoe design always sought closeness.72 In designing his theater, Wagner recognized that radical differences in staging practice, making use of an area of the stage previously ignored, would require radical architectural differences as well.73 This movement back into the proscenium might have found its most extreme example in Wagner, and it did not spawn much in the way of imitation initially. But the sense of separation from performance space, a complete world cut off from the world of the theater auditorium, became an ongoing feature of theatrical staging in the late nineteenth century and had to make the dominant architectural form of theater less acceptable.

The Bayreuth Festspielhaus was sufficiently unusual in the extremity of its departures, that it took a while for its influence to be felt with the singular exception of the Adler-Sullivan Auditorium Theatre.74 Otherwise, the transformation was gradual, marked by a number of interconnected developments throughout the nineteenth century, each one signaling a shift in the way stage space was handled:75 the advent of the box set, the framing of the proscenium arch and the elimination of the forestage, new technologies for illumination that allowed for a radical shift in the way the space of the stage related to the auditorium, all of these, as it turns out, important developments for motion pictures as well. “From the 1860s, greater realism in plays was reflected in the scenery, and wing and border setting began to be replaced by box settings representing ‘real’ rooms with side walls and ceilings.”76 With the seemingly self-contained space represented by the box set, the stage setting appeared more cut off from the auditorium. The separation was made definitive when English actor Squire Bancroft and his wife Marie took over management of the Haymarket Theatre in 1879 and had it remodeled, installing one feature that was much imitated: the proscenium was rendered as “a massive and elaborately gilded frame complete on all sides, the lower part forming the front of the Stage and concealing the Orchestra which is placed underneath.”77 Richard Southern notes that it is not clear how the orchestra was concealed, but perhaps the submerged orchestra was intended to suggest Bayreuth. Although it looked different, this gilded frame shared a common attribute with the Bayreuth proscenium and perhaps invoked the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk by its invocation of another art form: it was an absolute boundary forcing action to take place behind it.

If the proscenium as boundary cut off an area of action by eliminating any forestage, the box set effectively expanded it toward the back of the stage which had previously been limited by perspectival set design. In the past, lighting had also created a problem: in earlier indoor theaters, lighting was initially primarily by candlelight, subsequently by oil lamps, with the wing-and-backcloth system allowing for some light from the wings, but with a good amount of light coming from the auditorium itself, along with footlights, making the forestage area the most fully illuminated. Gaslight was introduced in English theaters in 1815, United States theaters in 1816, and Parisian in 1821. In the definitive study of theater lighting, Gösta M. Bergman notes the key advantages that gaslight brought: greater flexibility because “intensity could be varied at will by throttling the gas supply,” the “regeneration of the stage picture” because of the variety of kinds of light available, an overall increase in illumination both in the auditorium and onstage and, commensurately, “new possibilities of locating the action to the rear part of the stage, thus making it more mobile and realistic.”78 Improvements in lighting, then, were a necessary precondition for the box set, and the two together effectively opened up the expressive potential of the upstage area.

The final transformation, occurring around the same time the Bancrofts had the proscenium frame created for the Haymarket Theatre, came with the introduction of electricity. Thomas Postlewait has observed, “Electric light would radically change stage lighting and the principles of scenic design” (129). Most important for its impact on staging, “the maximum value of light on the stage increased strongly in the 1880s and -90s at most theatres…. At many theaters, this worship of light led to excesses. They virtually drowned the stage in light from the permanent lighting systems and arc lamps. Not the least was this true of American theatres” (Bergman, 295–96). This meant, of course, that the audience could see more of the set, but that in itself created a new problem: “The illusionary built-up pieces appeared as puerile deceptions” (Bergman, 294–96). So, the lighting called attention to background in a way that it never had before, but then led to an expectation that the background be more convincing in its realism.

This issue of background warrants more consideration, but to do so I first have to look at the lighting of the theater itself. Before the introduction of gaslight, the lighting in the auditorium could be changed only with difficulty, and so generally for indoor theaters illumination levels in the auditorium and onstage stayed constant throughout the performance. Gaslight provided the possibility of altering light levels during the performance, but initially the auditorium light was only lowered when stage light was lowered to depict a nighttime scene. The Bayreuth Festspielhaus once again looked ahead to future conventions when it “introduced the darkening of the auditorium in 1876. At the inauguration the public was greatly shocked when, all of a sudden, the lights went out.”79 Near-total darkness in the auditorium is, of course, a necessary precondition for motion pictures, but, as it turned out, not without contestation in early film theaters. Further, it is likely that the continuous nature of vaudeville performances as well as the need to look at a program in the course of the performance kept the twilight level of the theater somewhat brighter than in straight dramatic theaters, but by the late nineteenth century darkening the theater in some fashion did become a convention marking the beginning of a performance. There are two crucial things I want to take away from this. The brilliantly illuminated stage in a darkened auditorium escalated the sense of the stage as a self-contained world cut off from our world that had begun with the Bayreuth Festspielhaus and entered the commercial theater with the Bancrofts’ proscenium frame. The second change was in the auditorium itself: individuals became shadows, an undifferentiated mass. With this development, the horseshoe form lost its last surviving rationale.

Keeping these factors in mind, I want to return to the Vitascope premiere with one last point about the “new” approaches to lighting and set design. Bergman cites a negative response to the new lighting styles from Percy Fitzgerald, a contemporary (1885) observer, worth quoting here: “Again, the system of intense lighting has operated seriously to the enfeebling or overpowering of dramatic effect…. The abundance of light now shed upon the scene diminishes the relief of the figures, whereas the comparative shade [of the old system], or indistinctness of the background, throws out the figures.”80 For Fitzgerald, then, the dimness of the back of the stage was an advantage for it served to make the performers stand out more from the setting. Although Martin Meisel ultimately makes something very different of it, his analysis of the effect of the Haymarket proscenium frame also notes a shift in how human figures related to background setting: “‘Tableau’ in drama meant primarily an arrangement of figures, not a scene and its staffage…before [English actor-theater manager] Irving and the Bancrofts the actor was not yet so bounded and contained by the picture, so much within it, that his ‘least exaggeration destroys the harmony of the composition.’ It is rather to the point that the conventions of academic portraiture at least through [Sir Thomas] Lawrence encouraged a similar disjunction between figure and ground, the latter, even as landscape, often suggesting theatrical scenery” (Meisel, 44). This then is the change that takes place in the last couple of decades of the nineteenth century: a transformation in the relationship between figure and ground, a transformation that had to affect how early motion pictures were perceived in their theatrical context.

On the face of it, this kind of figure-ground opposition would seem less of an issue for a film image that reproduces a reality in which all elements, transferred to film, have an identical ontological status, something made all the more emphatic by monochromatic film stock. And yet, because of production necessity, the films shown at the Vitascope premiere did have a distinctive way of handling figure and ground. This can be difficult to determine precisely because at most only one of the five Edison films appears extant, the “skirt or serpentine dance,” which is likely “Annabelle Serpentine Dance” (1895).81 But as with most of the early Edison shorts of performers, the performance was shot in the “Black Maria” studio, a structure whose interior had a small stage against a black background with an opening on the roof to use sunlight as the only light source (Musser, Nickelodeon, 35). As a result, the serpentine dancer was brightly illuminated along with some of the dance floor and banisters on the side. The rest of the image is entirely black, providing an almost complete separation between performer and background.82 Whether or not all the other Edison films had the same background-figure relationship, it is very likely that the one that began the show, “Umbrella Dance,” did.83 And this is the film that immediately preceded “Rough Sea at Dover.” In determining how the first film might have conditioned the second, it is worth keeping in mind that each film ran about twenty seconds, but was on a loop that was run multiple times, so that the figure against a black background would really be imprinted on the spectator’s vision with the abrupt shift to a very different kind of image.84 “Rough Sea at Dover” is extant, and it presents a richly detailed image, enough to have inspired the extensive description reprinted above from the original review: a pier on the left cuts across the image on a diagonal up toward the top center, the composition serving to emphasize the depth of the space as great breakers splashed against the pier and move directly toward the camera. The depth did strike one contemporary observer: “One could look far out to sea and pick out a particular wave swelling and modulating and growing bigger and bigger until it struck the end of the pier. Its edge then would be fringed with foam, and finally, in a cloud of spray, the wave would dash upon the beach.”85 While background-foreground movement is crucial to this film, there is no figure-ground aspect here since it is all setting, which makes the opposition to the previous film particularly stark. Finally, the elaborate means necessary to change realistic settings in contemporary theatrical practice had to make this abrupt shift from the black background of “The Umbrella Dance” to the fully detailed natural world of “Rough Sea” seem truly startling.

It is in this context, then, that Frohman could understand the reality effect of motion pictures primarily in terms of setting. Movies effectively operated within a larger theatrical context and were in part defined by it, and for Frohman this meant a period in which the very sense of a theatrical setting was changing. I want to emphasize that this transformation was a process and not a straight-line development. Change rarely happens without resistance, and there were certainly economic forces that would promote continued use of wing-and-backcloth scenery. Indeed, until the teens many theaters and many early narrative films continued to use painted flats even for practicables like a clock on the wall or flats that had lighting effects painted on them, a procedure that had already begun to look archaic on the stage under the hard electric lighting of the 1880s. But in narrative film by the teens, “interiors were beginning to be constructed and painted so that they appeared to be actual rooms in real buildings—not stage sets.”86 With the subsequent rise of the feature film in this period, the alliance between screen and setting that Frohman imagined at the Vitascope premiere would help determine how films were exhibited, as we will see. But in a horseshoe theater, setting was perforce a secondary part of the theatrical performance because a large part of the audience had limited access to it. In live theater an approach to staging that gave more and more expressive value to scenography would finally render the horseshoe theater obsolete. In similar fashion, the film image exposed the limitations of the horseshoe theater much as the development of motion pictures would be limited by the space in which they were exhibited, a space that inevitably made them isolated pieces of entertainment dependent upon novelty.

SPEEDING TRAINS, SCREAMING LADIES, AND THE FOURTH WALL

As a visual novelty like the Glyptorama, motion pictures could fit within the entertainment paradigm offered by vaudeville, and the architectural form of the vaudeville theater need not be the problem that it became for realistic staging in live drama. However, while moving the image closer to the audience could make the realism of moving pictures all the more astonishing by comparison to tableaux vivants, it could also effectively undermine that realism. The screen’s flat surface and its downstage location, a position that movie theater practitioners would reject by the teens, meant that objects on its surface would become easily distorted the further the viewer moved away from a perpendicular view. And quite a few of the audience in a horseshoe theater did in fact depart from the perpendicular. This is to say that the realism of the motion picture image, as powerful as it might have been for contemporary observers, is not automatic: it is in part a function of the architectural space in which it is placed and the concomitant vantage point of each individual spectator.