THE TWIN INHERITANCES OF THE MOVIES

In the fall of 1913 The Moving Picture News, a prominent exhibitors trade journal recently purchased by competitor Exhibitors’ Times, promised among other innovations that it would soon “announce the new name of the merged publications.”1 A couple of weeks later the new name appeared: The Motion Picture News! This hardly seems like much of a change now, but the editors clearly regarded it as sufficiently different to help signal the “highest aspiration of The Motion Picture News…to represent the art and industry of the motion picture in a dignified, honorable and progressive spirit.”2 How could the change from “moving picture” to “motion picture” possibly seem significant?

Subsequently, The Motion Picture News explained the difference by reprinting on its editorial page an article from a Boston magazine entitled “Motion Pictures Versus ‘Moving’ Pictures”:

The error, into which many good people had fallen, of referring to motion pictures as “moving pictures” has led to a number of humorous interpretations of this source of entertainment. Although the masses are not disposed to analyze the origin of any name or designation, there are persons who, realizing that properly projected motion pictures are virtually a quick succession of stereopticon-views, appreciate the correctness of the term “motion pictures.”

In a motion-picture house the spectators are concerned only with what is displayed on the screen, and each of the numberless pictures is shown within a limited and stationary space, all of them combining to simulate motion, but the pictures themselves do not move. However, as the term “moving pictures” has come to stay, it is applied by discriminating people to inferior houses, whereas the correct and dignified term “motion pictures” refers rather to the respectable and refined character of the display and its environment.3

While the dignity of motion pictures, as we saw in the last chapter, could be a function of the performance venue, here Motion Picture News makes technology itself key to dignity, “the correct and dignified term ‘motion pictures.’ ” How “motion pictures” advances a “respectable and refined character” more than “moving pictures” is still a matter of exhibition venue since the latter term “is applied by discriminating people to inferior houses.” But Motion Picture News goes further by effectively conflating class with technological knowledge. We become “discriminating people” by acknowledging our knowledge of how “motion pictures” actually work: in the process we can reject the spectacles optiques aspect of films, no longer regarding this as a wonder in itself, as it was in the early vaudeville performances. In centering our concern “only with what is displayed on the screen,” we correctly understand motion pictures simply as a means to give us access to the best of theater.

Implied in these claims is an opposition between knowledge and enthrallment that suggests a twin inheritance for the cinema and reflects, in turn, the class opposition suggested by the Motion Picture News’s reference to “discriminating people.” To some degree this twin inheritance also found expression in the opposition between the legitimate theater and the vaudeville theater that I explored in the last chapter. If the twin inheritances of the movies are the legitimate theater and the centuries-old tradition of the magic lantern show along with other trompe l’oeil entertainments, then the latter ultimately belonged to the vaudeville theater, where it could be made part of an evening’s entertainment, as I discuss in chapter 2 with the Glyptorama, which had preceded the Vitascope at Koster and Bial’s Music Hall. In this chapter, I want to explore this twin inheritance as a way of understanding a fascinating exhibition practice that was a standard for film presentation in the teens and twenties, a practice that now must seem very foreign to us.

By defining “properly projected motion pictures” as “a quick succession of stereopticon-views,” the Motion Picture News article rightly placed movies—yes, I’ll opt for the more vulgar and incorrect term—in the context of magic lantern shows of earlier decades. But what would that tradition invoke for a contemporary audience in 1913? In recent decades, there has been valuable writing about the “magic” in magic lantern shows of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the predilection for phantasmagoria and shock.4 Placed in this context as a development out of the magic lantern, early cinema may rightly be called, as Tom Gunning has argued, a “cinema of astonishment.”5 Even before the movies, movement as a source of astonishment was a common element in magic lantern shows since they could create a simulation of movement in the image by bodily moving the lantern or manipulating two slides in relation to each other. But the movement presented was of a very limited nature, so that while cinema could seem an extension of the magic lantern show, it also differed in that it apparently—and magically—presented the real thing, an uncanny re-creation of lifelike movement.

But if there was magic in the creation of movement, a seeming sleight-of-hand that fit in with the phantasmagoric tradition of magic lantern shows, it was also magic of a different nature. The magic of the magic lantern shows involved a deliberate manipulation of the environment to fool the senses. For example, total darkness that concealed the exact location of a transparent screen would make it possible for the illusion of specters hovering in an indeterminate space. Change the environment—bring up the house lights a bit—and the illusion vanishes. As a descendent of the magic lantern, movies could also produce such illusions, as was the case in the mid-teens with a cinematic imitation of “Pepper’s Ghost,” one of the most famous of the nineteenth-century phantasmagoria.6 Alternatively known as “Kineplastikon” or “Photoplast,” this technique, billed as “Pepper’s Ghost on the Motion Picture Screen,” utilized a partially reflecting sheet of glass to conceal the actual location of the movie screen and give the impression of projected actors moving about the real space of the stage.7

F. H. Richardson, the most astute contemporary writer on film technology, observed, “The thing is not, in our opinion, applicable to the motion picture theater. It is a vaudeville stunt.”8 By the time Richardson wrote this, he could assume that most of his readers would agree with him that cinema had cast its artistic lot with the higher form of theater, not with the lower form of stunts, and, significantly, he saw stunts as more appropriate for the vaudeville theater. Since the vaudeville theater was also the model for the movie palace, it is worth noting that similar kinds of stunts have existed throughout the history of movies, of course, most particularly in lower entertainment forms like schlocky movies and the specialized thrill films produced for amusement and theme parks, not the kinds of movies that would aspire to be taken as competing with live drama. On the other hand, it might be possible to claim all movies are stunts since they are based in illusion, but one that does not require the sleight-of-hand in presentation of the magic lantern show. Rather, the illusion of movies works differently: “the pictures themselves do not move,” as the Motion Picture News article noted emphatically, yet so long as the images were projected at the required minimum speed, nothing in the circumstances of presentation would allow us to see the still photographs basic to the illusion. The movement, the illusion, took place entirely in the mind of the viewer.

While “persistence of vision” has often been cited, from the beginning of cinema, as the essential explanation for the illusion of movement, it is in fact merely a precondition necessitated by the particular mechanical apparatus used to project movies.9 The stop-and-start mechanism of conventional projectors necessitates a shutter to block light as the film advances from one image to the next so that the screen remains dark for a certain percentage of the time. The persistence of vision only guarantees continuity of image. Even if the illumination were continuous—as it is, for example, with shutterless projectors or flatbed editors—we would still see movement, although there would be no persistence of vision.10 To this day it is not entirely clear what exactly is responsible for our perception of movement in movies. As a consequence, any possible explanation must seem more mysterious than the more visibly apparent persistence of vision theory.

At least as early as 1912, the year before the Motion Picture News articles previously cited, Max Wertheimer in “Experimental Studies on the Seeing of Motion” offered an explanation that broke decisively with the persistence of vision by identifying the “phi phenomenon.”11 Subsequently, experimental psychologist Hugo Münsterberg explained this phenomenon by summarizing the experimental research of “the last thirty years” in his 1916 The Photoplay: A Psychological Study, one of the earliest works of film theory:

the perception of movement is an independent experience which cannot be reduced to a simple seeing of a series of different positions. A characteristic content of consciousness must be added to such a series of visual impressions…. [A]bove all it is clear from such tests that the seeing of the movements is a unique experience which can be entirely independent from the actual seeing of successive positions…. The experience of movement is here evidently produced by the spectator’s mind and not excited from without.12

There is something magical about movement in movies because we cannot fully explain it, but it is a peculiar kind of magic, not at all the result of a sleight-of-hand. Rather, it is magic mysteriously created by and within our minds. It is a kind of natural magic.13

This mental magic was a central point for Münsterberg’s theory since he sought to argue that the uniqueness of film as an art form lay in its ability to imitate the actual processes of the mind. The image was flat, yet perceptual cues in the image prompted the mind to create a sense of depth. The image contained no movement, yet the perceptual cues of rapidly projected still images led the mind to create a sense of movement.

Depth and movement alike come to us in the moving picture world, not as hard facts but as a mixture of fact and symbol. They are present and yet they are not there. We invest the impressions with them. (30, emphasis in the original)

André Bazin might have argued that “Photography affects us like a phenomenon in nature,” but it also clearly affects us—and most especially in the movement of movies—as a phenomenon in supernature.14 There is simply something uncanny in cinema’s ability to draw out the magic of our mental apparatus.15

Still, my invocation of Bazin at this point and the Bazinian realistic aesthetic suggests another way of looking at the photographic image. I began this chapter by invoking a twin inheritance for cinema. So far I have been concerned with the way in which movies operated as the culminating moment within what Charles Musser has called “a history of screen practice,” specifically as the inheritor of a roughly 250-year tradition of magic lantern shows.16 But as is evident in the preceding chapters, there is another history to which movies belong, and one particularly relevant to a journal like Motion Picture News in 1913: the history of the theater. If Motion Picture News, like many other contemporary observers, hoped for a change in the dignity of movies by an alliance with the “legitimate” theater, the theater in this period had itself undergone a striking transformation in the previous thirty years or so (as discussed in chapter 1). This was most evident in the stage work of preeminent playwright-director David Belasco:

The beginnings of Belasco’s Broadway career in 1882 marked more than simply a significant personal milestone. Changes were taking place at this time which affected world theatre profoundly; stage naturalism was waging a decisive struggle against the older, established theatrical conventions and practices.17

I cannot concern myself here with the programmatic purposes of theatrical naturalism, but “the meticulous attention to material, outward details—in setting, props, lighting, and so on,”18 the shift away from painted flats to lifelike three-dimensional sets, the new dramatic emphasis granted environment that I noted previously, these innovations are of some consequence to the reception of the feature film. If theater gravitated more and more toward a material realism, then film could seem as much a culminating development in the history of the theater as it was in the history of the magic lantern show.

These twin histories might find a culminating convergence on one object, but they also produce a kind of tension in the object inasmuch as they stake out different aesthetic aims: a kind of supernaturalism set against naturalism, astonishment set against persuasion. This is not to say that audiences weren’t astonished by Belasco’s meticulous re-creation of Child’s Restaurant, complete with the wafting odor of pancakes, on a theater stage with his production of The Governor’s Lady in 1912, but this is a different kind of astonishment from that of the movies, based more on our expectations of how elaborate a theatrical set may be. Having the restaurant “exactly reproduced in every detail,” as Belasco’s prompt book has it, is not really a magical matter any more than naturalistic French director André Antoine’s purportedly purchasing “the interior of a student’s room in Heidelberg and transfer[ing] it intact to the stage” for a production of Old Heidelberg is magical, although certainly astonishing.19 In some ways, we would be less astonished to have a movie show us the actual Child’s Restaurant or the actual student’s room in situ, and yet the movie is purely illusionistic in a way the theatrical set is not.

A further distinction needs to be made here since the examples I have cited are reconstructions of constructed environments, which means they can, with sufficient time and financial resources, be built on a stage much as the originals were built in reality. But what about natural environments? For Tiger Rose (1917), set in the Canadian Northwest, Belasco created a forest onstage as well as an exceptionally realistic rainstorm, while in The Girl of the Golden West (1905) he opened the play with a view of Cloudy Mountain in the Sierra Nevadas.20 For settings like these, various kinds of trompe l’oeil effects had to be used, and these did move the sets more into the realm of magical illusionism.21 For example, the opening of The Girl of the Golden West actually created an illusion of movement by means of a vertical rolling panorama that took the audience from mountainside to the town, anticipating, as an observer noted in 1940 “a characteristic ‘pan down’ of cinema technique.”22 Much as the realism of naturalistic theater seemed to look ahead to film, we still need to make a distinction between realism and reality. Naturalistic theater presented a three-dimensional space sufficiently contrived to invoke an actual setting so that audiences could deem what they saw “realistic.” Film, on the other hand, presented a two-dimensional surface on which a preexisting “reality” was reproduced.

In this context, it is understandable that Motion Picture News could claim in 1913, “The setting of the photo-play is incomparably more real than anything even a Belasco can give us.”23 As film became more and more a theatrical medium, much contemporary writing on the cinema thought its chief advantage over theater lay in its ability to bring the real world of nature into the artificial precincts of the stage.24 Tom Gunning has astutely observed, “Restored to its proper historical context, the projection of the first moving images stands at the climax of a period of intense development of visual entertainments, a tradition in which realism was valued largely for its uncanny effects.”25 Gunning does not include theater in the “visual entertainments” he considers, and it is questionable if European naturalism, in its aim to define the impact of environment on human existence, was consciously searching after uncanny effects. American naturalism and Belasco in particular seem different in this regard since Belasco’s realism was often on such a grand scale that it clearly sought to astonish.26

Still, if nature in the film image seemed so much more real than any re-creation of the natural environment the stage could offer, the image was also more of an illusion than most trompe l’oeil stage techniques since it showed something that, as Münsterberg accurately observed, was not really there.27 In theater, every object on the stage was present and existed in a space it shared with the audience. In film, the image presented a seeming physical reality contrived from a mere play of light-and-shadow. The paradoxical nature of film in its play of presence and absence prompted a striking response from French drama critic Louis Delluc to his early experience of cinema that is itself playfully paradoxical:

A chance evening at a cinema on the Boulevards gave me such an extraordinary artistic pleasure that it seemed to have nothing at all to do with art. For a long time, I have realized that the cinema was destined to provide us with impressions of evanescent eternal beauty, since it alone offers us the spectacle of nature, and sometimes even the spectacle of real human activity.28

Artistic pleasure from something that isn’t art, beauty that is both forever and fleeting—all this suggests the uncanniness of cinema in that it provides an experience that moves us beyond any conventional rational categories that may contain it. But if the cinema has such power to unsettle our confidence in our own perceptual mechanisms, how could it also improve itself by becoming the transparent purveyor of theater?

CONTAINING THE UNCANNY IMAGE

As the illusions of theater and film are different, a striking difference in the way each exhibited its respective illusions to the audience had become established by the emergence of the early feature film. That difference and the implications of a distinctive exhibition practice in the teens and twenties will be the concern of the rest of this chapter. Even within the context of fourth-wall staging, which seems to efface its devices and simply present us with a slice-of-life reality, an elaborately decorated gilt proscenium as a frame for the stage setting and actions effectively lays bare the illusion. No matter how elaborate, detailed, and realistic the setting, no matter how naturalistic the performances, they nevertheless exist within the same space as the proscenium, so that the proscenium, framing the otherwise invisible fourth wall, effectively calls on the audience to participate actively in the construction of the illusion. In a sense, the uncanniness of the stage illusion is tamed by the fact that it requires our complicity: we are co-creators of the illusion. In film, on the contrary, the illusion remains disturbingly uncanny because it happens both within us as a consequence of our neurological makeup, yet seemingly independent of us since we cannot deconstruct the illusion.

If the fourth-wall aesthetics of naturalistic theater found a way of marking off the space of the setting from that of the theater, there was less certainty of how the space of the film image, seemingly so different from our space, should set itself off from the rest of the theater. As noted in chapter 1, the earliest showings in vaudeville theaters invoked a kind of magic pictorialism in their presentation with the Vitascope as a successor to the Glyptorama even in its “staging” of the film screen encased within a gilt frame. This practice continued into the nickelodeon era as described in chapter 3 and seems to have been a common exhibition practice until the introduction of the feature film. At the dawn of the feature film, however, another practice was proposed in 1909 that would move film exhibition in a strikingly new direction:

To our mind, something in the nature of a compromise between the ordinary and a moving picture stage is desirable. Let us imagine the ordinary stage opening. It may be forty or fifty feet across and proportionately deep. But you do not want a picture that size. It seems to us that the best plan in such a case is to set the moving picture screen well back on the stage and to connect the sides of the house by suitably painted cloths or side pieces so that when the house is darkened and the picture is shown the audience have the impression that they are looking at the enactment of a scene set a little way back on the stage. They look at it, as it were, through an aperture or tunnel, at the side of which there is nothing to distract their attention, but rather something in the nature of a design complementary to the picture which shall concentrate their attention on the latter…. The average audience likes illusion, and the greater the illusion, the better it likes it. An ordinary stage play, after all, is only an illusion.29

As we saw in the previous chapter, beginning with the earliest feature-length films, movies were being shown more and more frequently in legitimate theaters. But in the architectural space of the legitimate theater, the motion picture image encountered an exhibition problem.30 While screens at the time ranged from 12 to 20 feet, an “ordinary stage opening” is described here as “forty or fifty feet across.” On such a stage, black masking or even a gilded frame situated on a dark stage would only emphasize the smallness of the image and decisively set it apart from the dramatic space of the stage. The solution proposed above of the set surrounding the picture would make the space of the image continuous with that of the stage: there would be a setting across the entire stage as in any live performance, but in effect all the action would take place upstage. In the process, a new illusion could be created that complemented and extended the illusion of realistic stagecraft: where a setting extending to the downstage area could aspire to realistic re-creation, the upstage image could present a photographic copy of the real world. As this writer’s praise for illusion suggests, this manner of presentation would effectively ally the magic illusion of the film image with the more concrete illusion of the stage.

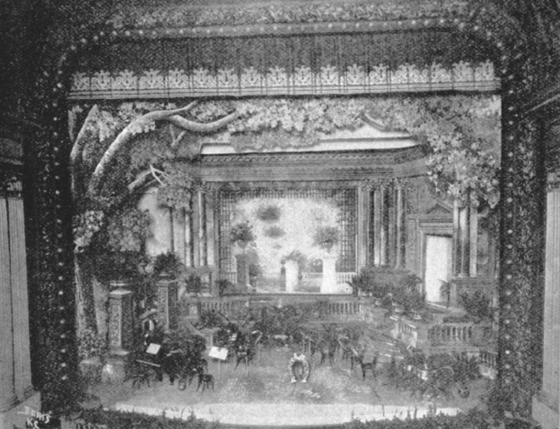

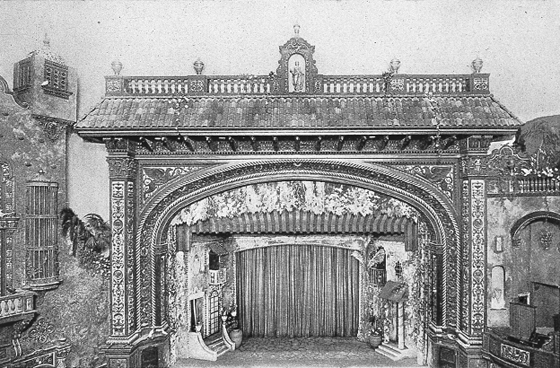

Although the “picture set” or “picture setting,” as it was subsequently called, would soon become common in first-run theaters, I do not know if the stage setting described in this article is merely a recommendation or the invocation of an actual practice. Nor have I been able to determine precisely when the first picture setting was used. But it is clear that the arrival of the feature-length film, modeled on stage plays, did lead to a manner of presentation that would become standard practice until the introduction of sound: the motion picture screen placed upstage within a theatrical set of some design. As we have seen with the touring companies for George Kleine’s imported Italian features, these were like combination companies in live theater precisely because they were sent around with settings. By 1913, the movie screen encased in a stage set had become enough of a convention that Motion Picture News could praise a theater for going a different route: “Instead of having the wings of the stage fitted up with regular scenery, as is too often the case, Mr. Lynch draped the whole stage in heavy dark curtains.”31 By 1914 there is evidence of theaters in the Midwest both large and small using picture settings (figs. 5.1 and 5.2).32

How commonplace the screen in the stage setting quickly became can best be demonstrated by a more prominent counterexample—the New York showing of D. W. Griffith’s Birth of Nation in 1915. When The Birth of a Nation opened on March 3, 1915, it followed the practice of other big features at the time by renting a theater normally used for live drama, the Liberty Theatre in Times Square. Nevertheless, Griffith wanted to make this showing distinctive, and he did so by using the theater’s standing scale of $2.00 top for tickets. Up to this point, legitimate theaters used for special-event feature films generally utilized a lower price scale. The obvious ambition expressed by venue and price was very much in keeping with what Griffith claimed in a curtain speech: “he said that his aim was to place pictures on a par with the spoken word as a medium for artistic expression appealing to thinking people.”33 The use of a legitimate theater and its $2.00 top have been noted before, but there was a third unusual aspect to this showing that has gone unremarked, although it is something that actually departed from Griffith’s invocation of the “theatrical” as a way to achieve prestige for his film: “In showing the film, the stage at the Liberty Theatre appeared merely as a black background on which the screen was placed. Mr. Griffith, it is said, refused all suggestions for scenic decorations, holding that attention should not be distracted from the picture.” This is to say that a manner of presenting the image that would now strike us as conventional was then regarded as a departure from convention. Why?

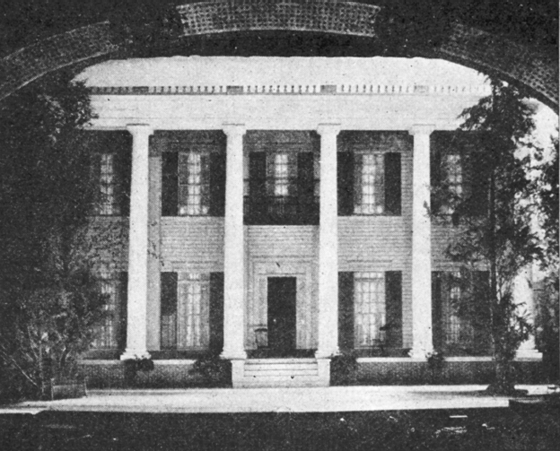

I can get at the distinction here most clearly by comparing the New York performance to the Los Angeles opening a month earlier at Clune’s Auditorium. In New York, the curtain rose on the titles of the film, but at the earlier Los Angeles premiere of The Clansman (D. W. Griffith’s first title for Birth of a Nation), on February 5, 1915, the curtain rose to a grander spectacle (fig. 5.3):

In the opening the curtain rises on a Southern home, of two stories, the front adorned with six pillars. The stage of the Auditorium is 100 feet wide and 55 feet deep. The opening is 50 feet. The mansion, which is 68 feet wide or long, if you prefer, sits back 20 feet from the stage opening. As the house appears to view the orchestra softly plays “The Mocking Bird.” A woman garbed as Mrs. Cameron emerges from the front door and sits down to the side. A man dressed as Mr. Cameron comes out, caresses the hand of the woman, and slips into a chair by the entrance. The orchestra shifts to “Suwanee River.” The stage lamps are lowered. A light appears in an upper window. The music changes to “Old Kentucky Home.” The screen is lowered. The house is in the atmosphere of the story before the title is shown.34

This description doesn’t specify how the screen was situated once it was “lowered,” but Griffith’s remarks at the New York premiere as well as my subsequent examples strongly suggest that the screen was made an element of the setting, that in Los Angeles at least “attention [could] be distracted from the picture.” Griffith was clearly aware he was doing something radical at the New York showing: in trying to make claims for film art as the equal of stage art, he made the image the stage itself. But the image as stage was hardly the common understanding of the period. As the manager of Clune’s Auditorium remarked of the Clansman showing, “the proper presentation of a big subject should increase by at least 50 per cent the entertainment quality of the producer’s finished work.”

Because dominant conventions can be powerful, even Griffith himself had trouble abiding by his notion of the unencumbered image. When he premiered Broken Blossoms in New York on May 13, 1919, Griffith did remain true to his ambition to claim the status of legitimate theater for his cinematic work: at a point when he could have used a dedicated film theater because far more had been built and many legitimate theaters had been converted to film theaters, he nevertheless booked the film into the George M. Cohan Theatre and did so as part of his “Repertory Season,” thereby enhancing its status as theatrical event. Nevertheless, there were plenty of extra-filmic distractions in the performance: the theater was filled with incense, while colored lights played on the screen throughout the showing to complement the tinting of the image. And the “film,” or perhaps more accurately, the evening’s entertainment, began in the following manner:

at the rise of the curtain there is a tableau depicting the Chinese priest at prayer over the bier of his loved one, and nearby the Buddha, smiling benignly. This scene is a trifle too long-drawn, and it is a question whether “Broken Blossoms” wouldn’t be as effective without it.35

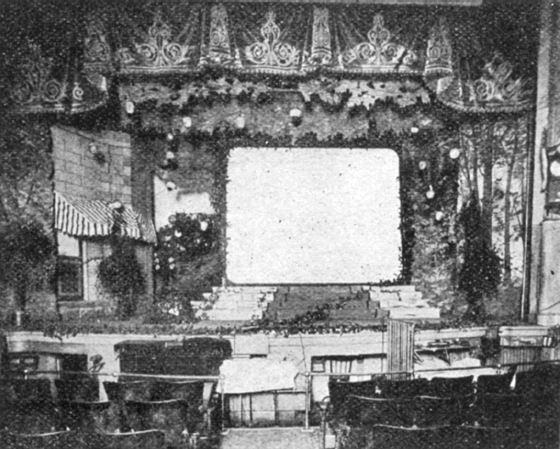

As with The Clansman, contemporary reports do not say anything more about how the screen was placed on the stage, but practices at the time as well as other performances of Broken Blossoms suggest that the screen was situated within the set designed for the prologue. The concern for a special staging of each feature was not limited to reserved-seat theaters in the biggest metropolitan areas. Consider, for example, presentations of Broken Blossoms at two smaller city theaters: at the Majestic Theatre in Portland, Oregon, ushers were dressed in Chinese costume to complement a Chinese motif on the stage (fig. 5.4),36 while the Liberty Theatre in Spokane, Washington, presented “novel stage settings and attractive decorations” (fig. 5.5).37

Although I cannot determine a first instance of these picture settings, they do have a clear antecedent in Hale’s Tours since the train interior that framed the screen was a constructed world like a stage setting. In chapter 2, I had considered Hale’s Tours architecturally, for the way it provided a model for the nickelodeon. But it is also important in anticipating how the film image may be made to relate to its surrounding space. While films were made specifically for Hale’s Tours, at the time of its inception there was already a body of films perfectly suited for it, namely the “phantom ride” films popular in England toward the end of the nineteenth century, “conventionally projected motion pictures of scenic locales which had been photographed from the cowcatcher of a speeding train.”38 Charles Musser quotes a contemporary response to a phantom ride film that is of some significance here:

The spectator was not an outsider watching from safety the rush of cars. He was a passenger on a phantom train ride that whirled him through space at nearly a mile a minute. There was no smoke, no glimpse of shuddering frame or crushing wheels. There was nothing to indicate motion save the shining vista of tracks that was eaten up irresistibly, rapidly, and the disappearing panorama of banks and fences.

The train was invisible, and yet the landscape swept by remorselessly…39

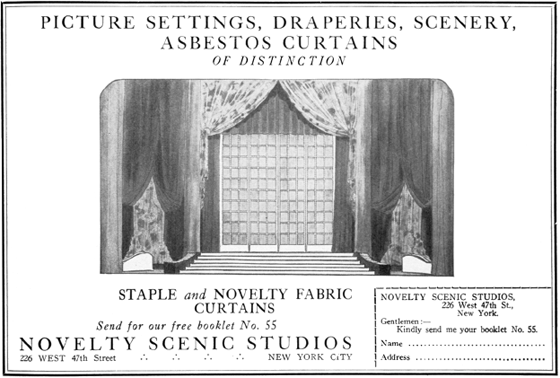

As the description makes clear, the name “phantom ride” was appropriate for these films because there was something uncanny about them in the way they seemed to turn the spectators into phantoms, almost disembodying them. By anchoring the phantom images in its realistically re-created setting, Hale’s Tours in effect kept the phantasmic thrill of the ride but tamed the uncanny aspects of the medium by making the illusion extend off the screen into the reconstructed environment of the train car. The entire train car was not unlike the stage settings described above, complete with the film image located upstage. As a consequence, the train car set provided not only a context for the image but also a containment. If Hale’s Tours possibly represents the earliest attempt to encase the moving image within a theatrical setting, by the 1920s this had become such a standardized part of film presentation that companies specializing in picture settings advertised in trade journals, with Novelty Scenic Studios and Tiffin Scenic Studios the dominant advertisers (figs. 5.6 and 5.7).40 Also, trade journals would regularly feature examples of novel picture settings in their pages (figs. 5.8 and 5.9).41

Initially, except for extended-run theaters, which would use picture settings thematically related to the feature film, a distinctive picture setting could serve as a way of branding the theater, as will be evident from a number of examples below. They became such a common feature of film exhibition in the 1920s that through the late 1920s and even into the early 1930s a section known variously as the “Buyers Index” and the “Equipment Index” in Exhibitors Herald and its successor Motion Picture Herald had a separate entry for “Picture Sets,” listing four suppliers and a recommendation for how the sets could be used in weekly change theaters: “Picture sets in non-presentation houses are usually changed seasonally or prepared for holiday programs and special events. Theaters offering presentation acts make it a point to change weekly the effects surrounding the screen.”42 (For an example of a seasonal setting at the Hippodrome in Buffalo, see figure 5.10.)43 And the set as a theatrical frame for the movies was not limited to the stage. Photographs of atmospheric theaters, which emerged in the early 1920s, generally just show decorations along the walls or the ceiling, but if you look at them in terms of their stage settings, it seems clear that the theater itself had become an extension of the stage, much as Max Reinhardt around the same time had turned an entire theater into a set of a cathedral for his production of The Miracle. (For an example of how the stage set connected to the constructed setting of John Eberson’s atmospheric Olympia Theatre in Miami, see figure 5.11.)44

Before I explore how this taming of the uncanny applied to the picture settings used for film showings in the teens and twenties, I would like to take a brief detour through Sigmund Freud’s “The ‘Uncanny’” (“Das ‘Unheimliche’”) in order to establish more precisely how we might understand the magical effect of the movies as it relates to theatrical form.45 Freud argues that the uncanny lies in a recurrence either of ways of thinking that have been “surmounted” in a civilization—e.g., animism expelled by the triumph of rationalist thought—or emotions that have been “repressed” in an individual.46 Terry Castle has given Freud’s argument a historical dimension that has some interest for the history of film because it suggests a provocative way of thinking about one of cinema’s twin inheritances:

When did this crucial internalization of rationalist protocols [surmounting earlier forms of thought] take place? At least in the West, Freud hints, not that long ago. At numerous points in “The ‘Uncanny’”…it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that it was during the eighteenth century, with its confident rejection of transcendental explanations, compulsive quest for systematic knowledge, and self-conscious valorization of “reason” over “superstition,” that human beings first experienced that encompassing sense of strangeness and unease Freud finds so characteristic of modern life. (Castle, 10)

Enlightenment, then, begot its own forms of darkness and mystification, something Castle finds most evident in the “ghost-shows of late eighteenth century and early nineteenth-century Europe—illusionistic exhibitions and public entertainments in which ‘spectres’ were produced through the use of the magic lantern” (141).

Castle notes a striking paradox in the way these magic lantern shows worked both to demystify and mystify anew, in effect providing a rationalist explanation in order to create a sense of the uncanny:

The early magic lantern shows developed as mock exercises in scientific demystification complete with preliminary lectures on the fallacy of ghost-belief and the various cheats perpetrated by conjurers and necromancers over the centuries. But the pretense of pedagogy quickly gave way when the phantasmagoria itself began, for clever illusionists were careful never to reveal exactly how their own bizarre, sometimes frightening apparitions were produced. Everything was done, quite shamelessly, to intensify the supernatural effect. (143)

Exhibition in a seemingly rationalist context finds a striking parallel in the earliest film showings, which stressed film as a scientific advance. Even the early procedure of making the projector part of the spectacle was to present film as the latest wonder of the scientific age.

Nonetheless, these demonstrations were not purely science; rather, they became entertainment by a conjunction of wonder and science. The mechanics of film technology are sufficiently transparent that it is common knowledge a film strip is made up of still images, as my above citation from Motion Picture News makes clear (MPN, Dec. 13, 1913). By contrast, the technology of a television set is so invisible that it might seem more wonderful than movies in its complexity, and yet it doesn’t have the same uncanny effect because with television we have little sense of stillness magically transformed into motion.47 The popularity of persistence of vision as an explanation for how movies work likely lies in its easily comprehensible science as there seems little mysterious in the ability of intense light to leave a lingering trace on a receptive membrane. It is in fact something we can empirically demonstrate to ourselves. Yet this explanation has also served to repress the actual explanation, which does seem more magical since it is a strange phenomenon of the brain. In this way, our supposed scientific knowledge here leaves space for the return of the repressed and with it a sense of the uncanny. As noted in chapter 1, the early Lumière showings would begin by progressively—and magically—transforming a still image into motion.48 In this way, what begins as science ends as magic, much in the manner of the specter shows described by Terry Castle.

With these speculations on the uncanny aspects of movies in mind, I would like to turn to some of the earliest recorded theatrical exhibitions of film that utilized stage settings. The Motion Picture News article that recommended stage settings for the screen suggested a setting that would complement what was shown in the film image. This does seem to be the case with some of the earliest special film features, generally imported, such as The Last Days of Pompeii (1913), and this continued to be the case for features that played in extended-run theaters. But in the palaces it was more common throughout the teens to use a standing set that helped give the theater a specific identity. Consider, for example, the attempt to show movies in the vast original Madison Square Garden in 1915 as a way of trying to stabilize its shaky economic situation. The resultant film theater was enormous, approximately 8,000 seats. As a way of filling out the space in front of the audience, the management created a striking arrangement around the screen, intending it to operate as something of a trademark for the theater: “By the liberal use of stage ice and snow, the Fourth Avenue end of the arena has been made to look exceedingly arctic and from the projecting machines at the far end of the room come occasional suggestions of the aurora borealis. All this is to lend color to the slogan ‘Meet me at the Iceberg’…” The use of the aurora borealis, a kind of natural magic, as a way of enhancing the screen image reflects an the understanding of cinema as a form of magical nature.

Moving the film image into the realm of legitimate theater via the introduction of the feature film seems to have generally demanded a different kind of setting, one that shifted it away from magic and made it more a transparent medium that could mass-produce the theatrical experience previously available only in one theater at one time. In the previous chapter, I had discussed how the Vitagraph Company took over the “legitimate” Criterion Theatre in 1914 to showcase its move into feature film production. The manner of presentation was crucial to the strategy of the Vitagraph Theater. When the curtain went up on the conventional stage, audiences saw a specially defined set that Vitagraph wanted as part of the theater’s identity:

With the use of the theatre drop-curtain an artistic studio setting, with attractive art objects, draperies, rugs, is revealed. In the center of the studio is a large French window, looking out upon a balustrade.

Through the window is revealed the blue waters of New York Bay, and in the foreground the striking group of skyscrapers that cluster around the Battery.49

The view of New York harbor was accomplished through a panoramic painting on a backdrop, and since each show began with the setting of the “sun,” lights were strategically cut into the painting to represent stars. In all, this set appears to have been in the tradition of trompe l’oeil realism of the stage at this period (fig. 5.12).

The set served as a space of live performance that was interspersed with the film showings, but it was most specifically designed to showcase the film image. At the point when the film showing was to start—“dusk”—something magical happened: “The daylight scene faded slowly and lights began to twinkle here and there, all the way out to the lamp upheld in the outstretched hand of the statue Goddess of Liberty. As night fell over the delightful setting, the curtain dropped across the window and rose upon the picture screen hung across the window.”50 The reality of the film image in effect took over from the artifice of reality presented by the painting. In some ways, the painting had an advantage over the film image: it was in color, and it had a palpable physical presence. But it always remained a representation of the natural world, rather than the seemingly direct presentation the film image could accomplish.

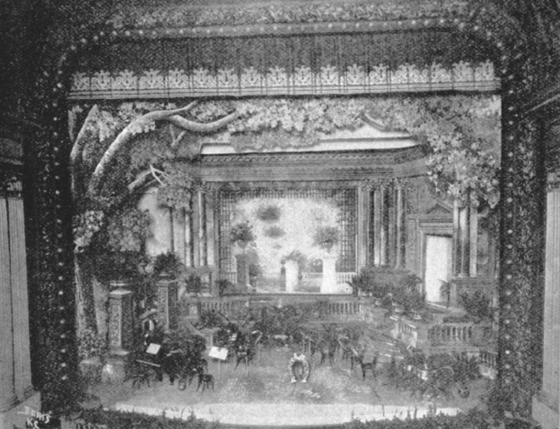

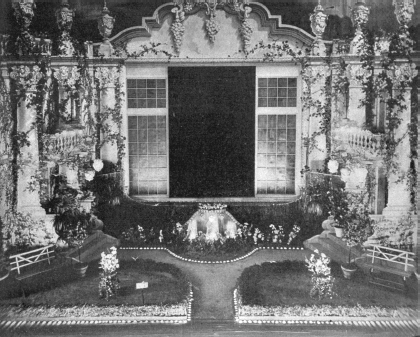

From the evidence I have been able to gather, I would say that a set as specific as an artist’s studio was generally not used in later picture settings. But there is one element here that did have a lasting influence on subsequent settings, what J. Stuart Blackton, the head of Vitagraph, called the “Window on the World.”51 The equation of screen with window seems to bespeak a common understanding of the period. A 1914 Motion Picture News article intended to explain the different kinds of screens available to theater owners begins forthrightly: “A projection screen is a window through which the public wants to see as many and as different interesting things as possible.”52 By about 1916 something of a template for permanent picture settings had emerged in deluxe theaters, what I would like to call the “window in the garden” (fig. 5.13). These settings generally present a formal garden, and, since it is a formal garden, elements of older architectural forms; in the middle of this garden, seemingly attached to a structure, is a large window. It is always in this space of the window that the movie image would appear. While the setting has elements of nature, it represents something that is also a construct in the real world, so that it is the kind of thing Belasco might present effectively on the stage without any trompe l’oeil effects. And although these settings could often be quite fanciful, there was a Belasco-like concern for physical realism in the use of real foliage and grass, treated to preserve them. And there was often, as in the example presented here, a fountain that could run intermittently (as we saw above) or even throughout the performance.

The stage set used for the opening of the Strand in New York (fig. 5.14) featured another element that was a common motif in the early picture settings that were used in the palaces:

The setting suggested the interior of a Greek temple, marble-like pillars supported an airy graceful roof, while to the right and to the left, one looked out from the sides of the temple upon hazy landscapes which made one think of woodland and of meadows. The green garlands wound about the top of the pillars, the profusion of flowers in front of the temple, the harmony of the Greek type of architecture suggests even in its ruins—all combined to make a noble and striking habitation for the screen.53

Although the structure does not look particularly Greek, the use of a clearly archaic architectural form at the Strand and subsequently other palaces could serve to validate the high-class aspirations of the new medium, the direct competitor to the legitimate theater. On the other hand, the elements of nature invoked the natural world, but in a way that could admit of human intervention, such as the flower arrangements at the Strand or, in other instances, a formal garden. The fountain situated in front of the film image became sufficiently de rigueur that supply companies soon began to advertise them in the trade press. But it was a fountain, not a waterfall.54 In this context of artificially constructed nature, then, the film image could assert its own superiority in its ability to present the real world of nature on the stage of artifice.

Still, if the film image was set apart from the artifice of the setting, the surround for the image was paradoxically a frame that doesn’t seem to be a frame.55 Where the gilded frame of the earliest film showings created a decisive boundary between film image and auditorium space, the picture settings of the teens established a continuity between image and stage set. There was still the frame of the proscenium arch to distinguish the space of the audience from that of the stage, but the proscenium also served to establish picture and picture setting as a kind of organic unity. By contrast, in Hale’s Tours the illusionistic space of the flat screen was made continuous with the real three-dimensional space of the train car. In a sense, the entire viewing area in Hale’s Tours was a stage set, with audience members and actors in a drama of tourism. In the conventional proscenium movie theater of the teens, the stage setting and the film image were set off from the audience and connected to each other because they offered differing ways of re-creating the world on stage. The picture setting might have highlighted an opposition between stage and film recreations of the real world, but it also, contrarily, muted the opposition by making the screen an indivisible element of the set.

THE THEATRICAL MOVIE SCREEN

At this point I want to return briefly to Freud because the play between opposition and similarity that I have noted in these picture settings parallels an essential point in his essay on the uncanny: a continuity between opposites. Freud begins the essay with an extensive consideration of the meanings of unheimlich, how it might be translated into other languages and its various connotations in German. As a preliminary, he notes, “The German word ‘unheimlich’ is obviously the opposite of ‘heimlich’ [‘homely’], ‘heimisch’ [‘native’]—the opposite of what is familiar…” (220). But exploration of dictionary meanings leads him to an odd fact: while heimlich in its primary meanings is clearly an antonym for unheimlich, a secondary meaning of heimlich—“Concealed, kept from sight, so that others do not get to know of or about it, withheld from others” (223)—is not. In fact, “among its different shades of meaning the word ‘heimlich’ exhibits one which is identical with its opposite, ‘unheimlich’. What is heimlich thus comes to be unheimlich” (224). The heimlich then effectively contains the unheimlich, and the uncanny is not so much foreign as something that exists within the known world.

This play of opposites that contains/conceals similarities may be found in the ways the screen was related to its picture setting during the silent period. Nowadays we tend to see the screen image as set off from our space by a sea of black cloth that leaves it spectrally suspended in midair. But in the teens and twenties, at least, much as the film image was usually situated within a stage setting, it was a permeable thing, as if the space of the screen were continuous with the space of the stage, at the same time that it always remained impermeable—the ultimate fourth wall, as I noted in chapter 2. From the mid-teens to at least 1920 there were various attempts to blend stage and screen action, with the film interrupted by a live-action performance on stage that was directly connected to the action of the film; the stage performance completed, the film then resumed its own course.

The earliest example of this intermingling used with a feature that I’ve found was the three-hour film version of a well-known novel, Ramona (1915), directed by Donald Crisp, better known as an actor, with a separate director indicated for the stage portions.56 The film was described in advertisements as a “Cinema-Drama,” then, a few days after the opening, perhaps to correct the suggestion of simply a drama on film, it was given a more intriguing designation, “A Cinema-Theatric Entertainment.”57 A description that ran before the New York premiere made clear that live-performance sequences would intermingle with film sequences, providing a bridge for separate sections of the narrative: “To heighten the feeling of atmosphere three massive stage settings will be disclosed at intervals during the exhibition. These scenes will be peopled by the characters of the story, but except in the songs they sing there will be no word spoken on the stage. After each setting the theatre will be slowly darkened and then the picture will appear on the screen.”58 Creating atmosphere frequently comes up in commentary as a goal for these stagings, as if live performers are needed to draw us into the remote world of the film. And while the performance was something of an entr’acte for the film, it did not remain completely discrete: “There is the staging, the three great atmosphere-creating sets shown before the prologue and the first and second acts, peopled by types of the period, Indians, musicians, singers…. The singing of the sunrise song as on the screen we see the members of the Moreno household at their window will linger in memory.”59

In spite of his earlier attempt with Birth of a Nation to make the image the stage, perhaps the most extreme example of intermingling stage and screen came from D. W. Griffith himself. For the New York premiere of The Fall of Babylon in 1919, Griffith had the film “exhibited in a setting of singing and dancing numbers that go to make up an elaborate program.”60 An advertisement the day of the premiere made clear the live entertainment was not simply a prologue to the film, a standard practice of the period I will discuss below, but, rather, something that occurred repeatedly throughout the film’s showing:

The production will be preceded by an acted prologue on the speaking stage, and interspersed with ensemble numbers, including Kyra and a ballet of living dancers—the first entertainment of its kind in America or Europe.61

Although The Fall of Babylon, originally one section of Intolerance (1916), is best remembered for its gargantuan sets and scenes of spectacle, the presentation, repeated in other cities, seemed to acknowledge that film spectacle was not sufficient.62 In the view of the New York Times review, it was in fact the emphasis on spectacle that facilitated the interruptions:

The dancing and singing numbers interspersed throughout the program enhance the effect of the whole, though their interruptions might impair a more compactly knit story than that of the photo-spectacle whose atmosphere they intensify.

This effectively posits an opposition between spectacle and drama that is crucial for the period and allies the exhibition practice at this performance with a spectacle tradition. A spectacle aesthetic could allow for the possibility of other kinds of spectacle, theatrical as well as filmic. There was nothing inherent in the fiction that created the need for live performers, but the demands of spectacle could.

But why should live performance “enhance the effect of the whole”? The kind of spectacle the stage offered as an extension of the screen is key here.

Actors, dancers and pantomimists in person are also used to augment the performers of the screen…. His [Griffith’s] effects are obtained by music, stage settings and lighting arrangements which are co-ordinated to the action of the screen.63

They are mainly interludes during the festive scenes on the screen, and the producer adroitly brings the singers and dancers forward in person at appropriate moments.64

If the primary appeal of the image is spectacle, as was the case with The Fall of Babylon, then the stage, while less convincing as a (re)presentation of reality, nonetheless offers more in terms of visual field because the “stage settings” quite simply expand what we can see. In their breadth, color, play of light in three-dimensional space, and simple physical presence, these interludes offered more excitement for the eyes. Second, if these “interludes” occur primarily as expansions of “the festive scenes on the screen,” the live stage can escalate the sense of festivity by offering song and dance because these are both elements that effectively stop the advance of the narrative and turn the drama into pure spectacle.

In the small number of film exhibitions which cut live performance into the film that I have been able to locate, it is not surprising, given the limitations of the screen at the time, that song and dance are the crucial elements in the interpolated material. Consider the exhibition of this 1920 film at the Los Angeles Theatre as directed by Samuel “Roxy” Rothapfel:

Twelve minutes after Allan Dwan’s magnificent cinema spectacle, “Soldiers of Fortune,” is under way, and after we have met his characters in the desert of Arizona and later in the millionaire’s ballroom in New York, the picture fades out and the stage is flooded with a glow of amber and gold. Out of the shadows comes human beings, singing and dancing, and blending with the flood of color we hear dreamy melodies of South American music.

The illusion lasts a few minutes. The lights are dimmed, melodies join their echoes and then the screen flashes back to us a panorama of a South American city. One seems to have stepped from the warm presence of real living people into their own city as the characters of the play again are assembled and we find the locale transferred from gay old New York to the mining camps of the foothills of the Andes.

The cut into the feature is a daring innovation, to say the least, but Mr. Rothapfel has done it successfully. The continuity of the story has not been interrupted, but rather the action has been accelerated. Certainly, the South American atmosphere introduced at this time prepares us better than any subtitle for our entrance with the character of the play into that land of jealousies and revolutions.65

Of course, this interpolated performance was not just a matter of adding song to the dramatic experience, since songs could be—and were—performed as part of the live musical accompaniment to films at this time. As with The Fall of Babylon, there is an implied concern that the live performance might derail the film drama since this description makes the counterclaim of enhancing the narrative and maintaining a continuity of story and action. Certainly the care that was taken with transitions from screen to stage and back again points to a focusing on continuity. But how the continuity was achieved suggests contemporary understanding of the differences in experience between stage and screen action: having the real people on stage emerge from shadows effectively allies them with the shadow figures on the screen, creating a kind of stage magic that could recall Living Pictures. As with Living Pictures, the presence of real people itself takes on a magical quality. Much as the screen creates a kind of enforced distance from the actors and a resulting coldness, the live performances grant the extra dimension of a “warm presence.” The transition back to the film image comes not with people, but with what film can always do better than the stage, “a panorama of a South American city.”

This opposition between the shadowy world of motion pictures and the fully embodied world of the stage was made explicit in advertising for an engagement of In Old Kentucky at Balaban and Katz’s Riviera theater in Chicago in 1920. The film was based on a very popular late-nineteenth-century play best known for its climactic horse race, as shown on the stage with actual horses on a treadmill. In his study of motion pictures as the successor to nineteenth-century theater, Nicholas Vardac claims it is precisely this kind of spectacular scene that movies effectively eliminated from the stage by being able to provide more realistic action and setting.66 The live performance preceded the famous scene and even brought actual horses onto the stage, but it did not attempt to re-create the race itself, which would seem to support Vardac’s claim.

As those who have seen the picture know the big “punch” of the play is the race which is won by “Queen Bess” and ridden by “Madge” in the absence of the drunken jockey. Interest in the picture at this point is at fever heat, occurring as it does in the fifth reel.

It was at this point the Riviera management brought in their novelty. The film was stopped, the screen raised and disclosed a corner of a typical Kentucky race course. Stable boys are lolling about, darkeys strumming on musical instruments sit beneath the trees while more energetic picaninnies are dancing in the dust. Off in one corner a crap game is in progress. The atmosphere of a hot summer day is conveyed to the spectator by the bright sunlight streaming down.

The time arrives for the jockeys to “weigh-in.” “Madge,” impersonated by a young lady about the size and build of Anita Stewart [the star of the film], saddle in hand, dressed in the drunken jockey’s riding suit, arrives, accompanied by the Colonel and the caretaker of “Queen Bess.” She is spirited to the stable and rides to the judge’s stand with the rest of the field. The gong rings. All is activity. The dice and banjos are laid away and the race is on. As the excited crowd leans over the paddock fence cheering the riders on, the screen descends, the orchestra crashes into a lively air and the picture continues with one of the most realistic and breath taking races ever filmed.67

But if this presentation seems to concede the thrilling realism of the race itself to the film image, why have live performance at all? A clue to contemporary thinking on this issue may be found in observations about stage setting and live performance from two contemporary witnesses. When Samuel Rothapfel—Roxy—opened the Regent in 1913, he devised a stage setting for the screen in a familiar tripartite form, surrounding it with two windows where singers would stand and occasionally perform during the film, as well as an orchestra onstage in front of the screen. An architect who wrote a column for Motion Picture News singled this out for praise in striking terms: “Mr. Rothapfel has the right idea, as a picture shown on a plain wall, with practically no frame to it, looks too cold and mechanical.”68 A dozen years later, by which time picture settings and live performance had become standard elements in movie palace entertainment, Eric Clarke, “Managing Director of the Eastman Theatre,” a highly regarded presentation house in Rochester, observed, “After an hour and a half of steady concentration on the screen, there is a need for something more—something that will show actual people as a contrast to the shadowy figures that flit across the silver sheet.”69 In the silent era, at least, when the lack of spoken dialogue could make the film image seem all the more a play of light and shadow, more mechanical re-creation than life itself, there was a need to bring real life into play with the simulacrum of life.

As in the other examples of interpolated live performance, not just music but singing figures prominently as a way of moving beyond the cold and mechanical.70 But with In Old Kentucky, this was not intended solely as an interlude that could enhance the atmosphere of the film; rather, there was also some concern with developing the narrative, effectively providing a scene leading up to the race itself that is not present in the film. The expansion of the narrative could possibly increase the suspense of the film by delaying the climactic race, a tactic suggested by the advertising for this performance. But the advertisement (fig. 5.15) also points to a different appeal, one pertinent to my concerns here:

The Super-Sensation of the Hour The Pulmotor of Riviera Presentation Has Actually Instilled Life Into the Shadows They Actually Step From the Screen HERE—On the Riviera Stage the Living Characters Enact Their Thrilling Ante-Climax THE STRUM OF THE BANJOS PLANK OUT THEIR ACCOMPANIMENT TO THE DANCING OF STABLE BOYS THE JOCKEYS LED BY MADGE Weigh In at the Paddock to Be Led to the Track on Their Blooded Mounts THE OLD COLONEL STEALS ACROSS THE TRACK TO HIS VANTAGE POINT ON THE FENCE The Tense Moment of Anticipation BECOMES A SEEMING HOUR AND THEN THEY’RE OFF71

If we often see the initial appeal of movies as the apparent re-creation of life, this advertisement also makes clear we are always aware it is not actual life. The live performance operates as a “pulmotor,” a device to pump oxygen into lungs, because it transforms shadows into actual beings, grants them a life they do not really have on the screen. Although the stage setting of a racetrack does not have the reality of the film set at an actual racetrack, it does have the reality of belonging to our world, where live actors can embody “living characters,” allied with but different from what we see on the screen. While that sense of presence could play against the excitement of the film’s climax by making the filmic action seem all the more remote, the intent seems to be a kind of heightening of our involvement in the action. It does this by making the live performers on the stage surrogates for us as viewers—more prominently, as the advertisement has it, “the old Colonel,” who takes his position on the fence to view the race.72 The “excited crowd lean[ing] over the paddock fence cheering the riders on” authorizes the return to the screen and the climactic race: we can return to the remote world of the film with an increased sense of excitement because we will see what the live performers on the stage, who belong to our world, are reacting to. As the advertisement suggested, live performance may serve to cross that divide, instilling real life into a world of shadows.

In 1921, the Motion Picture Directors Association, a forerunner of the Directors Guild of America, issued a statement to protest current exhibition practices as “a serious menace to any further advances in motion picture production”:

We mean specifically: Atmospheric prologues, vaudeville numbers and expensive orchestras….

…it is subtly impressing a certain class of our public with the thought that the play is not the thing but that the trimmings are…. In the opinion of this association, whose members are dedicating their lives to the betterment of motion pictures, the over-elaborate prologue is a useless adjunct to the feature picture, often destroying dramatic effect and turning the climax to anti-climax…73

I have found no further examples of interpolated scenes after 1921, but this statement does mention another practice, the use of prologues, that did in fact continue throughout the silent period. The prologue had originally begun with the feature films shown in exclusive theaters, much like the staged introduction to the 1915 Los Angeles premiere of The Clansman described above. The Embassy Theatre in New York City, discussed in the previous chapter as an unusual extended-run theater, was distinguished by its lack of a stage. What this meant for contemporary audiences was a feature theater without any live performance other than the orchestral accompaniment, a theater in which the film play really was the only thing, which the Motion Picture Directors Association had argued for. Whether or not the absence of the prologue led to the theater’s failure, this was the only feature-dedicated theater of the period to my knowledge that did attempt to do away with live performance outside of the score. Live performance, either prologues or vaudeville acts, would continue in first-run theaters throughout the silent period, with some presentation theaters replacing their vaudeville with the prologues typical of the prerelease theaters, the Motion Picture Directors Association’s protest notwithstanding. And the prologue in particular was a practice that the releasing companies promoted as well because of the belief it attracted audiences to the feature.

Although the interpolated scene in the Riviera presentation of In Old Kentucky did seem to acknowledge the superiority of film in the spectacle of the horse race, the staged horse race nevertheless figured in other exhibitions of In Old Kentucky, but usually as a prologue. In fact, First National, the releasing company of In Old Kentucky, not only encouraged theaters to stage a horse race, but even provided assistance to help them do so:

In the early history of “In Old Kentucky” the treadmill with the genuine horse race as the culmination of a prologue figured prominently. Certain branch offices of First National Exhibitors’ Circuit, Inc. made arrangements to supply treadmill and supplementary apparatus with the production.74

This is precisely the kind of scene that Vardac claimed film eliminated from the stage. But why then was this considered so successful, so much so that it would be imitated in other prologues? There is in fact some evidence of a genre emerging as it earned the sobriquet “the treadmill prologue,” as this comment on the exhibition of a Maurice Tourneur film, The County Fair (1920), demonstrates:

The treadmill prologue has been repeatedly demonstrated effective. Despite the cost involved in its use it has invariably exercised such stimulating influence upon ticket sales that it has taken its place in the list of practical presentation properties.75

One reason for the continuing value of these staged races is suggested by a comment on the photograph of such a race, which was “snapped while the horses were galloping at such a pace that their legs and feet didn’t register.” Compared to filmic illusion, a staged horse race is lacking as reality because we must be complicit in the illusion: as the treadmill keeps the running horses in the same place, we effectively have to imagine forward movement. But the very physical presence of the actual horses, our ability to see the speed of their hoofs and feel their strenuous effort, makes the race exciting in a different way. The film might be more realistic in showing movement through an actual space, but it also lacks the physical immediacy of live performance. There were reasons, then, for limiting this scene to the prologue where it could not be directly compared to the film.76

Why did the interpolated scenes fall by the wayside, while live prologues became standard practice until the introduction of sound? As we’ve seen from various examples of live theater–film performance, direct comparison was not entirely to the advantage of film as a representation of reality because film’s reality was always that of a shadow world, a magical reality. This sense of continuity between screen and stage setting in these early experiments could actually heighten the uncanny quality of the screen by setting the otherworldly, disembodied film actors against actors who were palpably present on the stage. Keeping this quality in mind, we might say that one possible function for the proscenium—and this was very much the case with Richard Wagner—was to create a sense of distance. By its nature, film was inherently remote, its world definitively cut off from ours as the world of the stage can never be. Yet much as the heimlich contains and perhaps represses the unheimlich, the stage setting sought to transform the image from the eerily strange to the eerily familiar. The early prescription in Moving Picture World for framing the screen to create the illusion of film actors performing in the real upstage space of the set, well before this became common exhibition practice, was intended to enhance the status of film. But as often happens in a movement from low to high, the attempt to move film into the higher precincts of the legitimate theater carried with it a certain repression. The stage settings so common in this period effectively served not as a frame, but rather as a container for the film image.

If the free play between film image and stage performance that happened in the interpolated live scenes effectively increased the uncanny quality of the image, the prologues often seemed to embrace an opposite function. The interpolations, perhaps inadvertently, destroyed the diegetic world of the film, while the prologues were intended to provide an entry into it.77 Prologues usually took an element or a scene from the film and dramatized it before the film as a stage performance. On occasion, the entire plot of the film might even be synoptically presented as a pantomime. Generally, some kind of vocal performance was included in the prologues, with either dialogue or songs to contrast with the eerily mute film actors, who could move their lips without issuing any sounds. Since the prologue dealt with the same narrative material as the film, it implied a contrast in forms of expression. Yet one of the most frequent explanations for the prologues in contemporary commentary was to get the audience in the right mood for the feature film, which is why they were often called “atmospheric.” If so, why couldn’t the film itself get the audience in the mood?78

CURTAINING THE SPECTRAL IMAGE

The prologue served as a bridge from the physical world we shared with the space of the stage to the incorporeal reality of the film, as if something were needed to ease the transition from the familiar to the strange.79 Correspondingly, handling the transition from stage action to the onset of film image loomed as one of the strongest concerns in trade press discussion of prologues. Over and over again, praise would be offered for a novel way of effecting the transition. The ambition was always to make this as seamless as possible. Consider, for example, the first film of prehistoric monsters running wild in an island paradise, The Lost World (1925). This adaptation of “Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Stupendous Story of Adventure and Romance,” as the main title puts it, exudes an uncanny aura in two ways. It is an almost textbook example of the Freudian uncanny in that it brings back the lost past of the prehistoric world and inserts it, contrary to all rational expectation, into a contemporary reality. But it also highlights the cinematic uncanny in a very particular manner: Willis O’Brien’s first work in a feature film with stop-action clay models doesn’t simply reproduce actual movement with still images; it creates movement that was never there to begin with, movement that only begins when our brains process the film image.

The Lost World is, of course, unimaginable on the stage, and yet, true to contemporary exhibition practice, the prologue tried to place it in a stage context. For the Boston showing of the film, a prologue was devised that Motion Picture News especially commended to other exhibitors. It made striking use of magical trompe l’oeil effects unique to the stage:

the presentation was effected by a series of painted scrims—three in number—and an intriguing use of lights…. The scrims are hung in rotation and depict various phases of “The Lost World” story. When lighted from the front, they appear to be opaque and bring the color out vividly…. With a soft orchestral accompaniment, lights were slowly brought up on dimmers, disclosing a jungle scene. As the tempo of the music increased, the first borders were dimmed down while the electrician came up on the second border, thereby erasing the first jungle scene and slowly taking the audience deeper into the jungle vastness. A similar operation with the second and third borders disclosed the plateau in the distance, the musicians building the attendant suspense with their weird and mysterious music. Slowly the first and second scrims are taken away and the lights dimmed down on the third scrim and the opening scenes of the picture projected as the third scrim is hauled up into the flies, disclosing the screen.80

Since the movie screen was always placed upstage in theaters of this period, the movement from stage action to film image generally involved a kind of moving in, as if the audience were being invited to move from a world it recognizes to an unfamiliar, uncanny world. The final image on the third scrim, “the plateau in the distance,” effects a seamless transition to the first filmic image, the main title over a drawing of the jungle setting with a plateau in the distance (figs. 5.16 and 5.17). The deliberate use of stage magic in the Lost World prologue in effect renders the film image an extension of the stage effects, at once familiar and strange.81

For a variety of technical reasons that I will deal with in the next chapter, picture settings disappeared with the introduction of the talking film. As if to compensate, the transition from stage to screen was forged with the elaborate curtain arrangements which would last, with somewhat less elaboration, for the next forty years or so. Consider, for example, this description of the Egyptian, an atmospheric theater which opened in Boston in 1929:

There are five curtains, each seeming to increase in magnificence. The first, or asbestos curtain, depicts an old temple in Egypt, with a view of the Nile and the pyramids. The second curtain bears a likeness of the mouth of a temple, and some ruins of ancient buildings are in the background. On the third curtain, the scene is partly of the desert and of the Nile, and on the river is a sailing vessel. The fourth curtain is of Egyptian lace. The fifth and final curtain is of bright gold satin in folds.82

Although an atmospheric theater, the stage lacks the set design that would have made it continuous with the auditorium. Instead, the curtains have taken over the function of the picture setting, but in a way that marks a progression from concrete representations of Egypt, a kind of travelogue, to the abstraction of the final curtains. As such, they also seem to be taking over some of the function of the live stage presentations, albeit defining the general mood of the theater itself rather than the particularities of the feature film.83 It is likely that not every curtain would be used as a direct lead-in to the feature, but the description makes clear that all the curtains were intended as part of the entire show, with the progression finally yielding to the last curtain and the screen itself. Even if the curtains managed to ease the transition to the screen as a kind abstraction of the prologue, there is nevertheless something peculiar about their use with films, something I can get at by contrasting this with their use on the stage.

Why have a proscenium arch and curtains at all? Their function in the theater, as we’ve seen, created a new relationship between audience and performer/performance, with the curtains functioning as an extension of the proscenium, keeping remote and perhaps magical what a non-proscenium theater would simply make available.84 In the illusionistic theater, the curtain is necessary to maintain the illusion, to create the sense of a world that is clearly distinct from ours and seemingly sufficient unto itself. It does not allow us to see how that world is created, but rather presents it to us as fully formed. This is to say that all construction takes place behind the curtain; the curtain keeps alive a sense of magic in its production of effects by keeping us distant from the moment of production. It is for this reason that a curtain rising on a second or third act spectacle set will inevitably produce applause. But the curtain is necessary solely because the space of the stage is continuous with our space. Like the proscenium itself, the curtain creates a barrier that can make the space of the stage seem special.

Yet the curtain is a strange phenomenon as it stands in relation to the screen: not only is no barrier needed to distinguish the space of the screen from that of the auditorium, but also the curtain serves little practical function in the movie theater. It might offer some protection to the screen, a function that has been claimed for it in the past, but the fact that curtains are no longer used points to how little necessity there is for protection. The strangeness of curtains in movie theaters lies in the fact that the production of the image has its origins on the other side of the curtain, beginning in the space that we inhabit. The movie image does not come into existence solely as it strikes the screen, but, rather, it comes into existence when it strikes any object that might come between it and the screen. That is to say, an image can, and generally did, in past exhibition practices, appear on the curtain itself.

In order to make sense of the image on the curtain, it is worth keeping in mind a point made earlier: through the teens the most common word for what we now call screen was in fact “curtain.” In the store theater period, when there was no actual curtain, calling the screen a curtain was to acknowledge that there was no playing area behind the stage, that everything took place in full view, seemingly in front of the curtain of a conventional theater, with nothing concealed. The movement of the film image onto a proscenium stage with the advent of the feature film changed the way in which the “curtain” was conceived; it could become a “screen” that itself was subject to curtaining.85 The placement of the screen within the proscenium was in part also a matter of necessity since theaters continued to use the stage as a performance space alongside the screen presentation. But placing the screen behind the curtain also signaled a different way of experiencing the film image, since it now began in an almost disembodied state located more in our space, before it settled into its rightful space on the screen.