Common sense tells us that we all exist in the same universe with the same reality, yet we also know that everyone has their own different version of what’s really going on in the world. For example, when it’s snowing for some (e.g. skiers, kids, etc.) it’s the best kind of weather while for others (e.g. drivers, sunbathers, etc.) the worst. The big problem with reality is that we all think we know what it is; we generally think that our reality is the only one that’s correct and possibly it is the only one that actually exists. In this chapter we’re going to explore how wrong those assumptions are, and how much trouble they cause us.

The best way to understand how we filter ‘reality’ is by using the simple exercise below – read the first step and follow it before going onto the next one.

Take a moment to go into a room that has something red in it. A good place would be the kitchen if you’re near one; go in there in preparation for this exercise, throw the cupboard doors wide open, as that’s normally where red things live. If you aren’t near a kitchen then choose another room that has some red in it.

Now follow these instructions.

Take three seconds to gaze around the room, taking in everything you can see that is red, because in just a moment you are going to leave that room and recall accurately everything that was red. Then leave the room and when you’re far enough away that you can’t peek inside, write down a list of everything you saw that was red.

Don’t worry if you didn’t recall many, just one or two is absolutely fine, and shows your brain is working very well.

The next step is even more interesting, as I’d like you now to recall all the things you saw that were blue or green, without going back to the room.

Funnily enough, this is much more difficult to do. Many people will have a near-perfect recall of all the red objects and yet fail to recall much of what was green or blue. Take a quick trip back into the room with red things in; the chances are you will find many blue and green objects. Although it appears that you missed out observing some of the objects in that room, it is again an excellent sign that your brain is working very well.

The exercise’s instructions asked your brain to look for, or ‘filter’, red objects, which it did very precisely. It noticed all the things that were red and recalled most of them. In many cases, it will also have spotted things that were near red in the colour spectrum, such as orange and purple objects.

What’s intriguing, however, is what your brain does with things that are not red. The blue and green objects, for example, are not seen, not recalled and, even more significantly, disappeared from reality. It’s almost as if they are just not there.

In my office I have a blue table, and sitting underneath it, carefully positioned behind one of the thick blue legs, is a large red box. When people do this exercise, they always see the large red box but never recall the blue table or the blue leg, which partially blocks their view of the box. When they recall the red box, even though there was a portion they couldn’t see due to it being obscured by the table leg, in their mind they see the entire box. They have somehow managed to delete the blue table leg, and replaced it entirely with red.

This is actually normal brain function as the brain does exactly what we ask it to do – focus on one particular thing and pay attention to it. It hasn’t got time to pay attention to everything else, as it would be a waste of energy and brain-processing power. However, naturally this approach means that we completely miss things we’re not looking for and yet remain convinced that we’ve seen the whole story. We’ll cover this in much more detail later in the ELF (Excellence of Limited Function) recipes chapters but to sum it up briefly:

If it seems that you’ve got too much of anything negative in your life then spend a few minutes working out the answer to this question. Write down your answer.

The ‘filter for red’ exercise above shows how we can mis-see reality, but it gets even worse, as these next simple but significant exercises demonstrate.

Look at the text in the ‘square surrounded by four circles’ section.

The words within the four black circles appear larger, clearer and as if there is a bigger space between the lines. But the text and line spacing is exactly the same as in the rest of the paragraph.

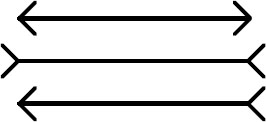

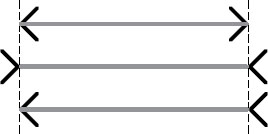

Consider the lines below. Which is the longest?

Well, it turns out, they’re all the same length, as you can see from the illustration below.

Interestingly, this illusion seems to work better in the Western world, which has created much debate. One set of data suggests this phenomena is related to familiarity with straight lines and angles due to most Westerners living in more ‘regular-shaped’ environments (e.g. most houses, cities, manufactured goods, etc. are based on straight lines and angles), so they are more used to the significance of lines and corners on dimensions.

Peoples such as the San who live in the Kalahari Desert, where straight lines aren’t much of an environmental feature, are the least fooled by the illusion. Another set of data, however, suggests it might be due to the differing pigmentation of the light-receptive retina, which is dependent on ethnic origin.

Whichever theory turns out to be correct, both sets of data show that there is a variance of the extent to which people are fooled by the illusion, and this further supports the theme of this chapter – that there are so many versions of the same reality!

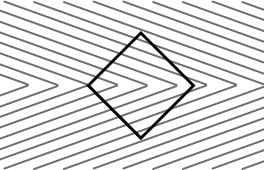

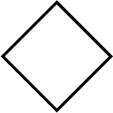

Keen students of optical illusions will recognize the following illustration as a variant of the Hering illusion, discovered by the German physiologist Ewald Hering in 1861. The psychologist William Orbison first described this version, which I think is the best, in 1939.

As you look at the diamond shape in the middle of Figure 1, you’ll notice it looks distorted; however, as you’ve probably guessed by now after a few of these illusions, it’s not (Figure 2).

Figure 1

Figure 2

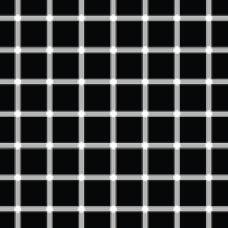

Below is another of my favourites by Herr Hering. Count the black dots you can see at the intersections of the grey lines.

Most people find they can’t count the black dots because as soon as you look at them they turn white. Some people find they can’t even see black dots as they change to white so quickly. Again, both are normal brain functions. But when you can see black changing to white in front of your eyes (and remember our experience of looking for red and only finding red), you might want to stop for a minute and consider:

And if it is natural that we distort our perception of reality all the time and completely buy into that distortion as being how the world actually is, then it raises an interesting question. Maybe we should be more careful, more proactive and more selective about how we distort that reality, so that it actually serves us better?

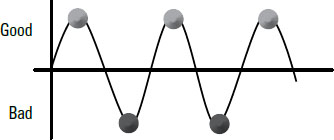

When you look at most people’s lives over a long enough period of time, you’ll see ups and downs – everybody has a wide range of experiences. I think it’s fair to say that there is a mixture of some great, good or mediocre things and some slightly negative, bad and quite dreadful things that occur in everyone’s lives. And overall there is probably a fair balance of both positive and negative occurrences. Yet different people seem to have very different experiences of how great or appalling their lives are, but when you sift through their life’s events it’s difficult, objectively, to see that one life was better or worse than the other in terms of what actually happened. How can we explain this discrepancy between what actually happened and the genuine experience?

The following graph shows the relationship between events and time, and so helps to explain this very important fundamental of life:

Figure 1

In the above figure, the line follows a course through extremes of both good and bad. But an interesting thing can be observed of people who appear to be unhappy, or more correctly, people dûing unhappiness. They notice there are good times and bad times. But they especially notice that the good times are followed by bad times, which destroys and blocks out any of the good feelings created by those good times. This tells them that if a good time is occurring, then, sure as night follows day, a bad time is on its way to them.

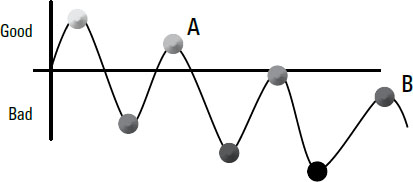

As a result, they start to follow the graph shown below.

Figure 2: point A indicates that things are better for this person, but they are sure it won’t be long before things turn bad again; point B indicates their experience that there’s more bad than good.

Each time something good happens they destroy it by anticipating the inevitable descending gloom. Unfortunately, this has the effect of making each downward turn even darker and more depressing, and so making it much more difficult for any of the positive events that do occur to have any life-changing impact. As result, this encourages an increasing feeling that the world is full of bad experiences. When they look at their life it seems very clear to them that life is difficult and not much fun, and that’s just the way it is. An external observer will notice that actual events in their life follow very much along the lines of the first graph (Figure 1) – an equal amount of good and bad – but to the person with (dûing) unhappiness their genuine experience is that life is fairly dreadful.

Let’s take a break from that unhappy version of the world and instead imagine it’s the day of the biggest event in the world of football (soccer), which only happens every four years – the World Cup Final, and you’re playing for your country.

The game is about to end, there are only three seconds left, when your team is awarded a penalty. (For those who don’t know the game, a penalty is when the ball is placed on a spot in front of the goal, and one player has the unenviable task of kicking it past the highly trained goalkeeper.)

Imagine that in this particular game you have personally scored 10 goals, while the opposition have scored none. Although there are many millions of people around the world watching you about to take this penalty kick, it’s fairly irrelevant whether you get it in or not: your team is going to win either way and, if you win the World Cup and have scored 10 goals in the final, you will be considered a living legend. People will name their children after you; buy you drinks in any bar for rest of your life and your name will be added to the roll-call of heroes. Getting it in would be nice, of course, but it’s not really that important if you do or if you don’t.

So, as you step up to take that penalty, how do you imagine you would feel?

Probably quite calmly confident, excited by the fact that this is a chance to score the 11th goal and knowing that within a few short seconds you and your teammates are going to be raising the World Cup and celebrating. What would you imagine are the chances of successfully getting your shot past the goalkeeper?

The answer is it’s probably fairly high, around about 70–80 per cent?

However, let’s imagine a slightly different situation. It’s still the World Cup Final, again there are only three seconds left on the clock and your team is awarded a penalty. However, this time, you and your team haven’t scored any goals so far and, even worse, the opposition is currently winning with one goal. Now this penalty kick becomes very significant. If you get it in you will have levelled the scores – a heroic feat. As the final cannot end in a draw and someone has to win, the game will go on to a period of extra time. It will be tiring but at least you have created the possibility of scoring a goal in extra time and winning the World Cup.

If, however, you fail to get your shot past the goalkeeper, the final whistle will be blown, the game will end, and you and your teammates and your country will lose. Now in every bar you go into, every TV appearance you ever make, some mention will be made of the moment you personally lost the World Cup.

As you step up to take this penalty, how does this version of the same event feel?

Probably you’ll be fairly stressed and quite concerned about the outcome. What would you imagine the chances of getting your shot past the keeper are this time? It’s probably quite a lot less than before, maybe 30–40 per cent?

Interestingly, in the highest levels of football and many other sports, there is a group of performers who are able to score with a 70–80 per cent hit rate in the first scenario. What makes them so special is that they are also able to score with exactly the same 70–80 per cent hit rate in the second scenario – the one where they are losing and all the pressure is on them.

They somehow put themselves in a position where, in spite of whether they’re winning or losing at this point in time or whether this particular kick is a game/life-changer or not, they’re able to perform brilliantly. They define genius, they are being their best; replicating the same results on demand, unconsciously, independent of what’s going on around them (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Some of the key elements of how they do that include telling themselves, quite reasonably, that:

They remind themselves that in both scenarios the ball is the same shape and the goalkeeper is just as prone to human error. They are also able completely to blank out the rest of the universe and keep their focus entirely on the ball and where it is going to end up. Nothing else exists for them in that moment; they are geniuses at filtering in a really useful way.

Naturally, if you were choosing players for your international team, you would much prefer to have people like this who were able to score when they’re winning and when they’re losing rather than just those people who were able to perform at their best only when they’re winning and everything’s going in their favour. I would like you to pause for a minute, knowing what you now know about geniuses and filtering, and answer the following question.

What if you were able to take that same perspective as those football players? Deciding that you’re the same ‘you’, independent of what’s going on around you. Deciding to be your absolute best when it’s easy to do that, as the world seems to be smiling on you, but also when everything seems to be against you. If you could do that in your life, in the same way as they do on the pitch, then what kind of extraordinary life would you start to attain? Make sure you record your responses in your workbook.

This outcome is exactly what you’ll be learning to achieve throughout this book.

Now, you may not have noticed it before but that footballer and your route to happiness are very closely linked to a surprising creature, the rubber duck.

This unlikely hero explains a concept, which is core to osteopathy and many other alternative and complementary health approaches, and is vital to understand and embrace if you want to get the life you love – the rubber duck’s ability to float.

When 29,000 rubber ducks broke free from a cargo ship in 1990 and slipped overboard they became the unwitting participants in a survey of world weather patterns by oceanographer Dr Curtis Ebbesmeyer. He realized he was able to track the movements of this brightly coloured flotilla throughout the world by encouraging beachcombers to collect the ducks when they landed and send in their reports of sightings to him. By studying the ducks’ adventures he was able to collect data about the oceans currents and changing weather patterns and so build a better model of how the complex system of worldwide ocean currents work. After 10 years at sea they had covered 17,000 miles, and now, 20+ years on, they are still exploring the world.

So imagine your surprise if you were to visit a swimming pool and as you gazed down into the depths of the clear water you noticed that there, submerged deep underwater, was one of our intrepid – and fundamentally buoyant – rubber duck adventurers. What is going on – we know that the rubber duck is unsinkable so why is it stuck deep under the water?

If you were to swim down you would find out that either something was getting in its way, blocking its passage back up to the surface, or that something was tying it down to the bottom of the pool. Once you’d worked out what the obstacle was and removed it, then the duck would naturally bob back up to the surface of the water. And, since its buoyancy is unchanged by time, it wouldn’t really matter how long it had been submerged since it will rush to the surface as soon as it is set free.

Apart from not having beaks or being yellow we have a great deal in common with the intrinsically buoyant duck. My experience is that we have similar buoyancy, but ours isn’t about an ability to float on water, ours is the inbuilt predisposition to soar on life’s currents, to naturally bob back up to the surface of life and bask in the sunshine as soon as the storm has passed. We have a buoyancy of happiness, fulfilment and contentment – that’s where we should be in life.

We also have within our genetic make-up the mechanisms designed to ensure we are vital, energetic, self-repairing organisms. It’s a natural function of being one of evolution’s winners; it’s part of our blueprint to be radiantly healthy and to mount effective responses to illness and injury.

So while the duck has the inbuilt ability to float, we have the inbuilt ability to float right back up to being happy, fulfilled and healthy, and to feel great and intrigued about life. This is our normal – our birthright; anything else that we put up with as being the ‘best we can get’ denies the amazingness of what it is to be human. Not a robotic human defined by our past, our experiences, our childhood or parenting, but a vibrant being that is present to the possibility that we can write our future on a completely clean slate, that we can be the architects of what happens to us next and design a life we love, right now.

If you’ve learned to believe anything else other than this about yourself, then remember the duck: it is only held down temporarily. As soon as it’s released it goes right back to where it should be, on the surface, basking in the sunshine.

And there’s so much more to you than the limited one-trick rubber duck! You come equipped with the most highly developed processing system on the planet, the human brain; you are a member of arguably the most successful species the world has ever seen, so if you’ve forgotten how amazing and resilient you are, then it’s time to take a moment to remember your true nature…

Most people learn to walk at about 11 months. But it’s not a simple, or initially successful, process. It was a long, protracted series of failures, of falling over and being beaten by gravity. But you didn’t give up, in spite of the bruises and disasters, you just continued until you mastered it.

This is who you are – a succeeder, someone who expects to overcome obstacles, who demands amazing experiences and keeps going until they get them. With that history alone you owe it to yourself to make sure you don’t sell yourself short for anything less.

Clearly, there is a link between our ways of thinking and what we perceive as reality, so we need to explore the nature of those thoughts by answering this interesting question:

What happens to your thoughts when you’re not thinking them?

So if you have an anxious thought and then you think about something else, what happens to that anxious thought when you’re not thinking of it?

There tends to be two schools of thought about how to answer this question.

The first, and most common, is that when we are not thinking them, our thoughts hang around in our unconscious or they are still there quietly operating, waiting for their chance to jump back into the foreground of our mental focus.

The second perspective theorizes that when we are not thinking some specific thoughts, then they do not, in that moment in time, exist.

Which one do you buy into?

My experience is that the second perspective is much more accurate and useful. It’s more accurate because, as we should recognize having studied active and passive language earlier (see Lesson 4: Active and Passive), thinking is an active process. Thoughts are therefore a shorthand description of that active process. If we are not thinking in a particular way then we will not be actively creating those thoughts, and so for that moment in time those thoughts don’t exist. And this is even easier to see if you substitute the idea of ‘dance’ for ‘thoughts’.

If I perform a beautiful dance and afterwards you’re so impressed that you ask where I keep my dance when I’m not dancing, and whether you can purchase it or borrow it, then we can clearly see that this makes no real sense as a question. The dance doesn’t have that kind of existence; it’s not an object or thing, it’s an action process, which only exists while we are activating it. Once we stop dancing a particular dance there is no more dance. And so, when we stop thinking a particular thought there is no more of that thought, until we start thinking it again.

So, for example, until I mentioned it, were you thinking about a purple octopus eating strawberry and lemon ice creams? I am pretty certain that you weren’t, but that you are now. (By the way, how many ice creams were there?) Where was that thought before you read that sentence? I think you’d agree that it didn’t exist. When you read the sentence you activated the nerve pathways that created the idea of the octopus eating ice cream, and at that point the thought was generated. When I ask you instead to focus on the big toe of your left foot, then the ‘octopus eating ice cream’ thought is replaced by the new thought about your ‘big toe’.

While it’s true that we may have ‘memories’ of previous or past thoughts, they only really become thoughts when we reactivate those memories. Our brain just can’t focus on all the memories we have of every single moment of our life all the time, it simply doesn’t have the capacity to do that.

So when we are experiencing a ‘thought’ it is a choice that we are making somewhere to trigger and activate certain parts of our brain. This is good news because this means we are in charge of our thoughts…

Although, of course, in reality that is so rarely true. We may indeed be activating our thoughts, but we mainly don’t choose which ones to activate consciously – again we see the power of the dû here. We are actively stimulating neurological pathways and generating thoughts (dûing thoughts), but we’re so often doing it unconsciously, triggering ‘bad’ or un-useful and, very often, extremely familiar thoughts, which produce unpleasant feelings.

That last sentence illustrates why thoughts are so important to explore; our feelings don’t arise for no reason or descend on us ‘out of the blue’, in spite of what many people will tell you. Feelings are a response to how we are seeing/thinking about the world and our current situation. The following story demonstrates this in action.

Imagine you’re stressed and anxious about an interview next week. Suddenly an old friend, whom you haven’t seen for years, calls out of the blue. You’re so excited to hear from them, you get lost in the conversation and, as you talk, what happens to your stress levels?

They go down.

Until?

Well, either until you put the phone down, or maybe until that moment when you notice you’re not stressed any more, which immediately makes you think about what you were stressing about before and reactivates the thoughts about the interview and the stress feelings.

Also imagine you go to work one day and have a really productive, great day. But when you get home you discover the washing machine has leaked and there’s a mess to clean up. You might be irritated about it but notice, even though the leak may have been dripping all day, the earliest point you could get those irritated feelings is when you first find out about the leak – up until then, since you didn’t know about the leak, you’re just not activating ‘there’s a leak’ thoughts, (unless of course you’ve been anticipating such an event – and planning that kind of thinking in advance - and as you are a genius, that’s entirely possible!).

So, we can see how our attention switches in and out of those ‘thoughts’ (dôes thinking on and off), and the feelings flow with it.

To summarize this important realization:

After all, if you learned to walk against the odds and have the resilient quality of a rubber duck, but find yourself in an unhappy, unfulfilled state, then you know this is not natural to you; it’s something you’ve learned and something you can unlearn, and replace with some ways of thinking that move you towards a life you love.

Before reading on, check you understand these vital topics:

Now you’re ready to make sense of my in-depth research into the ELFs.