Chapter 1

BALANCING THE THREE RINGS

Plummeting tail-first into cloud cover (where I shouldn’t have been) at the controls of a Bulldog T1 trainer aircraft, a few thousand feet above Royal Air Force Mildenhall’s military air traffic zone (where I definitely shouldn’t have been), I realized three things:

1. I’d failed miserably to execute a relatively straightforward maneuver called a stall turn.

2. I had to learn to prioritize the task at hand rather than allow my inner monologue to distract me.

3. I probably wasn’t cut out to be a pilot in the RAF.

While I’d love to proclaim, “And that’s when I knew I was born to be a product manager,” my route into the profession was more circuitous, as it is for almost all product managers. I had been planning to join the RAF when I finished my undergraduate studies, but that flawed stall turn told me I would have to switch to plan B. (Not a bad lesson for a future product manager, about which more later.) I’d never even heard of the role of product manager when I graduated, though.

Even today relatively few people outside the world of technology have heard of the job. When I’m at a party and someone inevitably asks, “So, what do you do for a living?” I always have to explain that product management is different from project management. (At which point my companion often hurries away to the bar. Now I sometimes just tell people I train dolphins.)

There’s a good reason the job isn’t better understood. Although it originated in the world of consumer products, product management is now mainly associated with the high-tech sphere and is rapidly evolving to keep up with the pace of innovation. It’s this breed of product management the book focuses on, though many of the fundamentals are the same and apply to the job as practiced in any sector.

WHAT IS PRODUCT MANAGEMENT?

One of the best descriptions of what a product manager does was crafted by Martin Eriksson, a product manager I’ve known and respected for a number of years who started the hugely successful ProductTank monthly meetup series in London.1 Eriksson describes the product manager’s role as it changes through the life cycle of a product. First, the job is not only to define the vision for the product, but to understand the product’s market and target customers and then to work with the product team to add a dose of creativity to make the product more alluring. It’s then about evangelizing the product vision and inspiring those making the product with that passion.

Switching from the creative to the analytical part of the brain, a product manager proceeds to plan how to actually execute that vision through product iterations, design, and roadmaps. Then, zooming in from the broad plan to the fine detail, there’s the day-to-day problem-solving, working with the development, design, and other teams to remove the obstacles in the path of the product while keeping the overall plan on track, and working with the marketing and sales teams to plan and execute the launch. After launch, the job becomes gathering and poring over information about how people are eating, sleeping, and breathing the product in order to assess its success. Then you do it all over again.

As you can imagine, the job is somewhat like spinning plates;* it’s a tricky balancing act to switch focus continually between the long and short term, the big picture and the fine detail. That’s a large part of what makes the work so stimulating and why a successful product manager requires a diverse set of social, commercial, and technical skills, and above all else the ability to empathize and communicate with many different groups of people on their own terms.

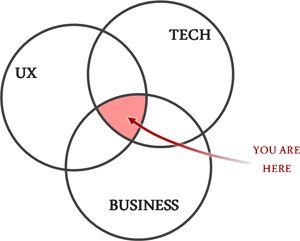

THE THREE RINGS

Product management Venn diagram courtesy of Martin Eriksson (http://www.martineriksson.com) and Mind the Product (http://www.mindtheproduct.com)

The product manager is right there at the center of it all, negotiating the inevitable push and pull between the needs of the users (user experience, or UX), the demands of the business, and what happens to be possible (or not) with the available technology. The three-rings diagram that illustrates this concept was created by Martin Eriksson. He jokes that only a product manager would think of the job in terms of a Venn diagram, but I think the image is very helpful as a shorthand overview of the dynamics within a company as it creates, launches, and evolves a product—and as a reminder of the challenges that arise in the eye of the storm. Let’s take a closer look at each ring of the diagram.

UX

People often interpret the UX ring purely as representing the user experience team, that is, the people within your organization responsible for the design of your products’ interactions with users. Instead, I’d like you to think of this in the much broader sense of the experience of your users. More importantly, this ring encompasses not only your UX team but also your target market—specifically, the needs and problems faced by the intended users and buyers of your product, the context in which they operate, and the way they experience your company and product, not just the specifics of how features are designed to solve their problems. The UX ring represents the outside world and its needs.

Business

Whether your company is for-profit or not-for-profit, at a bare minimum it needs to sustain itself, and its ability to do so is dependent on the success of the products and services it offers. From the perspective of the business, a successful product is one that is used and valued by customers, and one that is profitable. A business also has other needs, such as maintaining its reputation with customers and its relationship with investors, as well as all the practicalities of operating on a day-to-day basis. The business ring represents the needs and aspirations of your organization.

Tech

The pace of technological change is rapid, so a product manager needs to keep on top of the advances being made and understand the strengths and weaknesses of the technologies that will play a part in the creation of the product. Opportunities can arise simply because a recent innovation renders a problem more easily or cheaply solved than before. Your development team (which some companies call engineering) plays a crucial part as your interface to these technologies and in realizing the product vision. The tech ring represents both the technologies and technologists that shape your product.

ACHIEVING BALANCE

I’d love to continue by telling you how wonderfully easy it is to sit at the center of the three rings in complete and masterful control, but I’d be lying through my teeth. Some days it can feel like you’ve roped yourself into the hub of a bizarre tug-of-war between the various groups of people you deal with—and they’re all pulling you in different directions. But in the challenge lies the reward. We don’t do this because it’s easy—we do it because we can.

The good news is that there are only so many tensions that can crop up among the three rings; thereafter they’re just variations on a theme. From time to time, senior management will throw wrenches into the works, development teams will head off track on science projects, marketing teams will ignore inconvenient facts that spoil their message, design teams will create beautiful but impractical mockups, sales teams will be concerned with their commission over all else, finance teams will keep you as far away as possible from their numbers, and legal teams will veto anything that has even a whiff of risk. We’ll delve into the issues regarding managing and communicating with the team in chapter 3. Finding the right balance between the three rings is tricky. It’s surprising how many companies delude themselves into thinking that they’ve achieved a balance between the needs of their market, their own business aspirations, and the available technology. Companies often go off course by almost completely ignoring their market, perhaps because they’ve become too enamored with their own technology or because their own corporate objectives have distracted them, or sometimes both. (We’ll take a look at a few cautionary tales in the next chapter.) That’s why more and more companies are beginning to realize that they need to restore balance to be successful. They have a significant, urgent, and valuable problem that’s solved by hiring good product managers. (How supremely handy for those getting into the profession!)

Most people who know a little about product management think it’s a new discipline, a technology role for the technology age. Actually, its roots go way back to the first half of the twentieth century, to a maverick at Procter & Gamble, purveyor of such global brand giants as Gillette, Duracell, and Pampers. P&G has always been an innovator. The company started out in 1837 as a humble soap and candle maker.2 By the 1930s, it had diversified into cooking and household cleaning products, and when it pioneered product sponsorship of shows on network radio by sponsoring the Ma Perkins radio serial, what we know as the soap opera was born.

In 1931 a young and ambitious promotion manager named Neil McElroy, who had been put in charge of promoting the Camay soap brand, was frustrated that Camay always played second fiddle to P&G’s leading brand, Ivory. In a famous memo to management, he argued for the creation of the role of “brand manager.”3 This person would take overall responsibility for the commercial success of a product, managing it holistically like a business in its own right, conducting field studies and collaborating with other departments within the company.

The role as it’s now performed in the tech sector is in many ways fundamentally the same, but it has been tailored to tech needs and capabilities.

This is a great time to get into the profession because it’s become a more dynamic role in recent years. When product management was first adopted by the tech sector, products were created using the Waterfall serial project development process. All the product requirements were defined up front, and then the product was built, tested (maybe), and launched (thrown haphazardly out the door). Midproject changes were almost impossible to make, and particularly nimble companies managed two or—gasp!—three releases a year. Over the last decade or so, innovations in technology have opened up new ways of working. With the strong influence of Silicon Valley leaders like Google, eBay, and Facebook, product management evolved into a more central role, and it’s now undergoing another wave of change.

This new wave is driven by many factors: the explosion of web-based development tools; standardization of the use of particular programming languages, software frameworks, and platforms; and, most of all, data. Arguably product management always has been driven by data—McElroy advocated the use of field studies to gather data “to determine whether the plan has produced the expected results”4—but the key difference now is that data is so much more readily accessible, more easily analyzed in greater quantities, and often available in real time.

Organizations have begun using their new capabilities to apply rapid iteration methodologies derived from Lean Manufacturing5 to product development. It has become easy to test whether a hypothetical change would improve a product by actually building multiple versions and running a randomized controlled experiment (also known as a split or A/B test) to see which one performs better with actual users. Imagine you’re trying to improve the click-through rate for a particular button on a web page and you believe that making the button more prominent will achieve this. To test this hypothesis, you would show different pages with variations of the button, including the original version (or control), to visitors at random, comparing the results to see which version has the best click-through rate. Such real-time data analytics allow companies to rapidly improve products, sometimes creating many iterations in a single day.

Part of a class I teach on product management involves the students practicing their quick-draw wireframing skills by sketching a well-known website on the whiteboard for the rest of the class to guess, like a geekier version of Pictionary. One of the websites I ask students to draw is Facebook. The reaction is invariably the same: first the student smiles with recognition, thinking it easy to draw. He thinks about it a little more. A look of mild confusion replaces the smile as the student realizes he can only remember what it looked like a few years ago, usually before the introduction of the timeline. Facebook’s founder, Mark Zuckerberg, described one aspect of his company’s philosophy as: “Move fast and break things.”6 Instead of running extensive focus groups on every new feature to gauge its users’ reaction, Facebook just sends the features live,7 making changes only when the users’ howls of annoyance become loud enough, as was the case with Beacon, an ill-advised privacy land-grab.8 But analyzing data is just one of a blend of techniques Facebook uses, as Nate Bolt, head of design research at the company, describes:

It’s common for studies to have three or four redundant data gathering methods. Some of those data gathering methods will be qualitative and some will be quantitative. We have a pretty badass analytics team that’s gonna give us trends and insights and show us things happening on the mobile builds that we wouldn’t get out of qualitative testing. And then a lot of times, we’ll go investigate with the qualitative stuff.9

This is one way in which the role of the product manager is so important: in balancing the hard and soft sides—or left-brain versus right-brain factors—in developing and launching products. Data analytics can be a siren call luring a company away from listening in a more qualitative way to its market, neglecting human measures such as satisfaction and enjoyment. As Aaron Levenstein, professor emeritus of Baruch College, delightfully put it, “Statistics are like bikinis. What they reveal is suggestive, but what they conceal is vital.”

Which is why the right-brain interpretive and creative skills are still so important to the job. Replacing all direct market contact with pure data analytics just doesn’t present the full picture. Despite having around one billion users worldwide10 on whom to run multivariate tests,11 even Facebook cannot rely on data analytics alone—it still needs to engage with and listen to its market.

OWNERSHIP AND VISION

A product manager’s role is to own and be ultimately responsible for one or more product lines. And that means really own. To say that the buck stops with the product manager is an understatement. A true product manager will go and find the buck that’s buried on someone’s desk. But to be effectual, this ownership must come with the authority to make the decisions needed to steer the product to success. With their combination of extensive market understanding, intuition, and creativity, product managers are the people who can see a new opportunity emerging; visualize the product needed to take advantage of that opportunity; then enthuse, corral, and provide the necessary detail to the various specialists they work with in order to bring the product to life. Sometimes that new opportunity arises unexpectedly from the development of another product, as the scientists at Pfizer found with their new drug, sildenafil citrate. Although it was originally designed to lower blood pressure and treat angina, early clinical trials showed that the intended improvement in blood flow caused by sildenafil also happened to cause male erections. The drug is now better known as Viagra. But more often the product manager must recognize that the market has moved on,12 so the product in turn must change or be killed off.

A product manager’s role is essentially about providing three things: context, perspective, and vision. The context is a portrait of the real people in the market who have a particular problem or need, and describes the environment in which they experience it. That might be when they’re out walking their dog, working at their office, or driving in their car. Perspective provides an honest appraisal of how effectively the organization and its product are going about solving those problems. Possibly most important, vision is used to motivate and align everyone involved in creating a product by describing the product’s potential.

Without strong product management, the vision can often be corrupted by organizations for a few common reasons.

They’ve Stopped Empathizing

People at a company that’s focused on maximizing its revenues, profits, and share price to the exclusion of all else have probably ceased to care about their customers. They’ve become inwardly focused, forgotten about the outside world, and are more concerned with solving their own internal, corporate problems rather than those of their target market.

They’ve Forgotten the Real-World Benefits of Their Products

If a company’s forgotten how to empathize with its customers, it’s probably also in the dark about the real-world benefits its product brings to people’s lives. Like how Jeff doesn’t tear his hair out every time he uses the accounting system. Or how Clarissa, who’s lost all her wedding photos because of a broken hard drive, discovers they’ve been automatically backed up to the cloud without her realizing it.

They’ve Stopped Dreaming

People don’t dream of being given coupons in the supermarket, or finding a convenient parking space, or washing the dishes; they dream of going into space, or getting a job as chief taster in a chocolate factory, or discovering a new exotic particle. A product vision should be dreamlike in the sense that it has to be worthy of chasing so that people can anticipate their future sense of achievement and use that feeling as motivation to fight for it. It has to matter.13 Dharmesh Raithatha, once a senior product manager at Mind Candy, the company responsible for Moshi Monsters, described how Mind Candy repeatedly evolved its product vision to ensure it was always just out of reach.14 Your product vision must be a shining goal, a guiding star that everyone in the organization can visualize, so they become passionate about it and align themselves with it.

Organizations that create a mundane vision—“We want to be the dominant player in the blah blah blah market”—fail to motivate their workforces. With an uninspiring vision, dysfunction will seep in as self-motivated departments, teams, and individuals reject the vision and create their own guiding star to follow instead. In organizations without strong product management it is much harder to achieve alignment to a common goal because there is no single and consistent voice evangelizing the product vision, reminding everyone that they come to work each day to make the lives of people like Jeff and Clarissa just a little bit better.

A PROFESSION IN FLUX

Though the fundamental purpose of product management is widely agreed upon, you will inevitably encounter several competing but intersecting schools of thought on the role and its responsibilities. One view is that a product manager should be involved only in the identification of market opportunities (the “problem space”) and in no way with addressing that opportunity (the “solution space”); another view holds that the product manager must be responsible for defining both the problem and solution spaces. Google and other technology-led Silicon Valley giants will only accept candidates for the role of product manager if they have a computer science degree; other companies value and seek breadth of experience, irrespective of what the candidate happened to major in. These competing views and methodologies are frequent topics of heated debate within the product management community.15 To a newcomer, however, they must be positively perplexing and perhaps a little off-putting—how on earth are you meant to understand your role if the practitioners themselves don’t agree on what’s involved? So to keep things simple, the true crux of the job, no matter how it’s defined and what responsibilities you’re given, is to focus on the users. They’re the ones with the problem you’re trying to solve. Everything else is secondary.

What I would not recommend, as you learn about product management, is to adhere slavishly to the precepts and principles of any one particular framework or methodology. Use the Japanese principle of kaizen—continual improvement—and apply it to both your products and yourself.16 Try techniques out, keep what works, discard what doesn’t. Product management frameworks are a dime a dozen, and every company wants you to buy into its mindset and ecosystem of blogs, training, and books. The constant pressure on product managers to align themselves into factions citing the Silicon Valley, Lean, Google, or another approach as the One True Path is divisive nonsense. I’ve yet to encounter an organization that does product management in precisely the same way as another. In fact, I expect (and encourage) companies to tailor product management to suit their market, products, maturity, and culture. What won’t vary from place to place is that you should always be focused on the needs of your users and that you’ll need to collaborate with the specialists across all the departments in your company to bring your product vision to life.

If you’re working in a startup as a product manager, the job will be even more variable. You’ll be expected to roll up your sleeves and do a much broader variety of jobs. When I worked at a startup called Zeus Technology, I fulfilled roles ranging from trainer to IT manager to product marketer, all at the same time.

With the burgeoning demand, you’d think there would be more university courses, and even degrees, in the field. A handful of universities and business schools are in fact now offering degrees specifically in product management,17 and a good MBA course will teach you many of the skills needed to become a product manager, though in my view these programs can be too biased toward business theory rather than a more practical approach balanced across the three rings. A plethora of professional organizations worldwide offer product management training and certification. However, not all courses are equal, and without a standard benchmark for qualification, you have to be extra diligent when assessing the merits of the course you’re considering. Also, the fact is that product management is really a learning-by-doing job. So two tips: first, try to be taught by active product managers rather than those who gave up client work years ago; and second, choose instructors who have experience in the kinds of companies in which you would like to work.

I don’t think the dearth of undergraduate or postgraduate courses in the theory of product management is necessarily a hindrance to those on their journey into the field. Having a range of educational, social, and work experience, whether in or outside of technology, will give you the benefit of a broader perspective as well as diverse creative and technical skills such as communication, design, organization, and structured and lateral thinking. All these will better equip you to swap hats with ease between the different roles required of product managers.

The product people I’ve had the pleasure of meeting over the years have made their way into product management from wildly diverse backgrounds. Alison started out in UX but was frustrated by “crappy product decisions” by “the business” and set out to see if she could do better as a product manager, while simultaneously mounting a personal crusade against people who use terms like “the business.” A senior software engineer called Pritesh told me he felt there was too great a divide between him and the users. He wanted to spend more time understanding how people were actually using his product and start building products that solved problems for real people. It was at this point that he discovered the role of product manager. Tom, with whom I worked for many years, started a company straight out of college, sold it, then discovered that being a product manager was closest to what he’d enjoyed doing as an entrepreneur, albeit with a more predictable salary. Then there are others who turned up to work one day to find that their job title had changed without warning to product manager and were just expected to figure it out themselves. So don’t be dissuaded from starting your journey into the profession because you feel you don’t have the right background; we all have experience that can be highly valuable. Your product experience is, after all, the product of your experiences. There’s no such thing as a conventional route into product management—take my own story as a case in point.

FROM PLANES TO PRODUCTS

Ever since reading Roald Dahl’s Going Solo when I was young, I had dreamed of becoming a Royal Air Force pilot, so that flawed stall turn over the English countryside was a real moment of truth for me.

The mighty Scottish Aviation Bulldog (Courtesy of Geoff Collins)

Failing to execute the turn correctly before running out of forward momentum is a Bad Thing™. Going backward at speed in an airplane tends to cause bits to tear off. The danger didn’t seem to bother my flying instructor, a former frontline RAF station commander, in the slightest. He had his hands away from the stick because I was “in control.” With the wind whistling past in the wrong direction and our reverse speed mounting, he gave an almost imperceptible sigh of resignation and calmly advised me to simply brace the controls firmly and let the nose-heavy aircraft sort itself out.

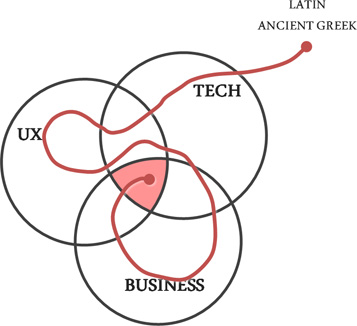

Not all my training flights were quite so inept, but it was clear to me that I wasn’t learning at a pace quick enough for the RAF’s intensive, rapid-fire training. With that career off the table, I focused on my undergraduate studies in my wonderfully practical major, classics. The study of the ancient world is a broad subject, covering everything from the linguistics of Ancient Greek and Latin to anthropology, architecture, poetry, and philosophy. It teaches you how to think and how to learn, but it’s not the most obviously vocational of subjects, and I didn’t think I would cut it as an academic. Thankfully, I’d become progressively more involved with computing, partly by accident. What started out as helping the student union tweak its website turned into managing its book publishing systems and network.

I also helped set up and run a free web hosting and email service that’s still prospering today.18 This had the side effect of introducing me to the community of computer scientists. Now I don’t want to give you the impression that I’d actually learned much real coding, and at the university’s annual job fair, I was laughed off the stands by most of the recruiting software firms as soon as I mentioned I was studying classics. For them it was computer science or nothing. A friend fortunately referred me to a company named (fittingly, for a classics major) Zeus Technology.19 It was a startup based in Cambridge, England, famed at the time for producing the “world’s fastest web server”20 and, for a while, powering eBay’s global search engine.21 The company was willing to take a chance on me, and so in August 2000, I began my first full-time job, on the Zeus technical support desk.

On day one, my manager deposited three hefty tomes on MySQL, Perl, and PHP on my desk and suggested I start reading, as I’d need to understand them to help resolve customers’ support queries by the following week. I now understand why: the product itself (Zeus Web Server) was rock-solid stable. We had customers who had installed it years before and had never had to restart it, let alone experienced any problems. Consequently a large proportion of customer questions had nothing to do with the product itself but rather dealt with the other software apps they ran with it. So partly because we had time to and partly because we on the support desk enjoyed it, we solved pretty much any problem our customers sent us. I distinctly remember spending hours talking a customer through a full system install, from bare metal upward. I found that solving customers’ problems was addictive.

Over the course of several years at Zeus, I cycled through a variety of technical roles, including web development and IT support (I was the guy swearing under the desk with a network cable). The dot-com bubble burst and three-quarters of the company was laid off. The people who were left had to start wearing several hats—at one point I was simultaneously the IT department, technical presales consultant, webmaster,* customer trainer, internal systems developer, product marketer, and, briefly, receptionist. While I’d been working in technical presales, and in the absence of a marketing department, I’d found myself creating product brochures and website material for prospective clients. I enjoyed the writing and publishing, and it wasn’t a massive leap from there to looking after “the message”—how we presented our company and products to our market.

There were two aspects of my job in product marketing that I particularly enjoyed: writing customer case studies and conducting win-loss interviews. Win-loss interviews involve calling up people who have either bought the product or decided not to in order to ask them why.22 Without exception, the conversations with the people who had chosen not to buy were far more enlightening. I started to learn where we’d gone wrong with our sales approach, marketing content, reseller management, pricing strategy, and product features. I began to get a feel for why we were missing out on opportunities and started to think about what we could do better next time. I took my suggestions to the head of development, who, in retrospect, was the de facto product manager, but I was “just” a product marketing manager—didn’t I have enough work to be getting on with already? I wanted to influence product strategy but didn’t know how I could. So I did some research and established that there was in fact a role that blended technical, commercial, and user-facing skills and looked after product strategy.

And that’s when I knew I was born to be a product manager.

My own path to product management was by no means direct.

In your own journey toward becoming a product manager, you can think of the three rings again, this time as a map for making your transition into the field. Each ring represents a different continent of experience you need to visit. Your starting point on your route may be within one of the three continents, or in a completely different area of expertise even farther afield. To end up at the intersection in the middle, you need to have journeyed through all three continents at least once. You can do so by working your way through different roles, as I did; by taking classes in each area; or, ideally, by doing both. However, there is no prescribed path, no right or wrong way to become a product manager—and every product person’s story is different.

So celebrate your degree in Chaucerian literature, marine biology, modern languages, or perhaps even computer science! Rejoice that you were the head of your school’s debating society, played football at club level, or organized charity events each year. Brag about the fact that you recorded an album in your bedroom or spent a summer fixing the plumbing in convents—product management welcomes students graduating from the university of life.

WHAT QUALITIES MAKE FOR A GOOD PRODUCT MANAGER?

When you’re looking for your dream product management role, many of the job descriptions you’ll read will state that the recruiting company is looking for domain experience in a particular market or technology. If you happen to have this experience, that’s a bonus, but if you don’t, don’t be discouraged! There are a few highly specialized exceptions, such as semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, and bioinformatics, but in general I don’t believe it’s necessary for a product manager to have previous experience with the markets, technologies, or products she’ll be working with. However, it is vital that you can learn quickly. Each company you work for will use different technologies to build different products for different markets with different dynamics. The faster you’re able to build up a decent working knowledge of each, the sooner you’ll be able to take ownership of your products. As a rule of thumb you should be able to do this within a month of joining a new company. The ability and desire to learn and understand are, in my opinion, among the most fundamental attributes of a product manager.

Achieving a good blend of technical, commercial, and user experience skills is important, but I don’t think there is—or should be—a fixed recipe for the cocktail that is a good product manager. I do, however, think there are certain traits that predispose people to be effective at product management. Before going any farther, don’t feel you should treat this as a definitive list or worry that you don’t exhibit some of these characteristics; I am still working hard to improve several of these myself. With that in mind, quality product managers:

- are sponges for quickly absorbing, understanding, and retaining information;

- are excellent listeners;

- are great communicators, mediators, and educators;

- can keep their heads when all about are losing theirs and blaming it on the product manager (with apologies to Kipling);

- can see both the bigger picture and the fine detail;

- are consummate problem solvers and fixers;

- are not afraid to roll up their sleeves and do something themselves if nobody else is bothering to;

- have a calming effect on others;

- always have a plan B;

- have an eye for spotting an opportunity, whether commercial or technical;

- are natural organizers;

- are capable of running a project successfully, but would not like being thought of as project managers;*

- will be able to pitch their product better than anyone else, but don’t want to have to do sales’ or marketing’s job for them;

- take negative criticism with good grace and continually seek to do better;

- like being recognized for doing a good job, but rarely solicit praise for themselves;

- recognize the efforts of others before their own;

- treat a problem not as a setback, but as an opportunity to make things better;

- have a natural curiosity and interest;

- continually test their (and others’) assumptions;

- tend to excel in something completely unrelated to their job—whether as cooks, musicians, writers, or linguists;

- hate feeling ineffective—take away their responsibilities, authority, or budget or stop listening to them and you’ll soon find yourself with a product-manager-shaped gap in your organization.

If these traits resonate with you, if you feel many of them describe you and the way you like to work, then well done! You’re in good shape for becoming an expert product manager.

LEARN THE BASICS BUT AVOID DOGMA

No matter what stage you are at in your journey to becoming a product manager—whether just thinking about getting into the profession or in the midst of taking classes, or maybe, as I did, having just plunged in from a different role—it’s important to get a good grounding in the full range of what the job requires and how it works. Reading this book is a good start, and there is plenty of other great writing to follow up with. (I make some recommendations at the end of the book.) As I’ve said, taking at least a basic class is also highly recommended for gaining a solid foundation to build on. I certainly benefited a great deal from some brief formal training when I started out.

In my first product manager job, I was fortunate to find an employer that packed me off to a product boot camp soon after I joined the firm. Off I went to Boston, Massachusetts, to receive a week of training with Steve Johnson, then at Pragmatic Marketing. Reflecting back, I recall enjoying the focus on the user’s needs and the repeated mantra, “Your opinions, though interesting, are irrelevant”—useful for reminding yourself that you, the product manager, are not the target market. I also remember feeling reassured that a great deal of product management boiled down to common sense and that what I’d been doing up to that point had not been too far off the mark despite working from first principles. After the course, I also appreciated having a framework to follow that corresponded with the way the company wanted us to manage the products and that gave me structured ways of thinking about a particular problem, allowing me to reframe it in a way that made it easier to solve. So I definitely recommend learning and following some kind of framework at the outset of your career as a product manager.

As I’ve mentioned, there are several product management courses and frameworks out there. Naturally, I highly recommend General Assembly’s product management course as an introduction to many of the fundamental concepts (not least because I teach it). I personally happened to start out with Pragmatic Marketing, whose framework breaks down product management into distinct strategic and tactical activities. You could try Silicon Valley Product Group’s recommended practices for the West Coast technology perspective and Sequent Learning Networks’ courses for slightly more of an East Coast business bias. Blackblot in Europe has a very structured approach, which may be more helpful for more heavily regulated, process-driven companies, and Product Focus in the UK specializes in product management for telecoms and IT. There are, of course, many other training providers and frameworks out there, with varying levels of quality and relevance. Your mileage may vary.

Whichever framework you start with, whether it’s one you’ve been taught or the process that’s already in place at the company you join, it’s important to keep in mind that people drive the process, not the other way around. Even if you start with a textbook implementation of a particular framework or set of best practices, it’s inevitable and important that you tailor the process to suit the needs of your market, company, and product and continue to adapt, evolve, and improve it as you go along. It’s unlikely you’ll ever find yourself following one of these frameworks in lockstep, even if you’re totally in charge of your process. This need for ongoing change simply reflects the fact that markets do not stand still. Product management had to evolve to respond to and capitalize on the opportunity presented by social media; online productivity tools are now much more widely available than in the past but can easily lead to a very fragmented, inconsistent, and confusing approach if every person on every project does similar tasks in completely different ways. To retain a modicum of control, you need to keep your process flexible enough to gain the benefits of consistent working practices while still allowing it freedom to evolve. However, if you find yourself in a situation where the people are serving the process instead of vice versa, there’s a good chance that you’re going about product management too dogmatically and missing a trick. Different situations, different products, different companies, and different markets will all call for different approaches. One size most certainly does not fit all.

Whichever path leads you into product management, I have one further piece of advice for you. Before accepting any product manager job offer, ask yourself the following questions:

- Does the product excite me?

- Does the market seem intriguing?

- Do I click with the people I’ll be working with?

One “no” answer by itself is not a dealbreaker, but if you’re able to say yes to only one of them, take this as a warning sign that the job may not be for you. Like any good product manager would, do your homework to reduce your uncertainties: Propose or accept any invitation to sit in with the team you’ll be working with to get an idea of what the organization is like. Speak to former employees if you can find them on LinkedIn, but bear in mind their viewpoints may be embittered if they left on poor terms. Play with the company’s products if you can get access to them, and note your first impressions and anything that surprises you; these observations are immensely valuable even if you’re not the intended target user. It’s also revealing to ask at the end of interviews why the product team does something in a particular way, not just to hear the actual answer but to see how defensively or openly the interviewer responds when someone challenges her approach.

Lastly, consider how the role will assist your professional development. Is it similar to something you’ve done before, perhaps reinforcing your natural bias toward one of the three rings? Or is it taking you a little out of your comfort zone and forcing you to gain more experience in areas where you’re less skilled? It’s perfectly fine to consolidate your existing skill set in a more senior, interesting role, just as it’s fine to make a sideways move to build up your experience if that’s what you need. What’s important is that you’re always striving toward a good balance between the three rings of product management.