ORIGINS OF ROME (c. 753 B.C.-450 B.C.)

THE ROMAN REPUBLIC EXPANDS (c. 509 B.C.-A.D. 1)

CIVIL WARS AND THE TRANSITION TO EMPIRE (First Century B.C.)

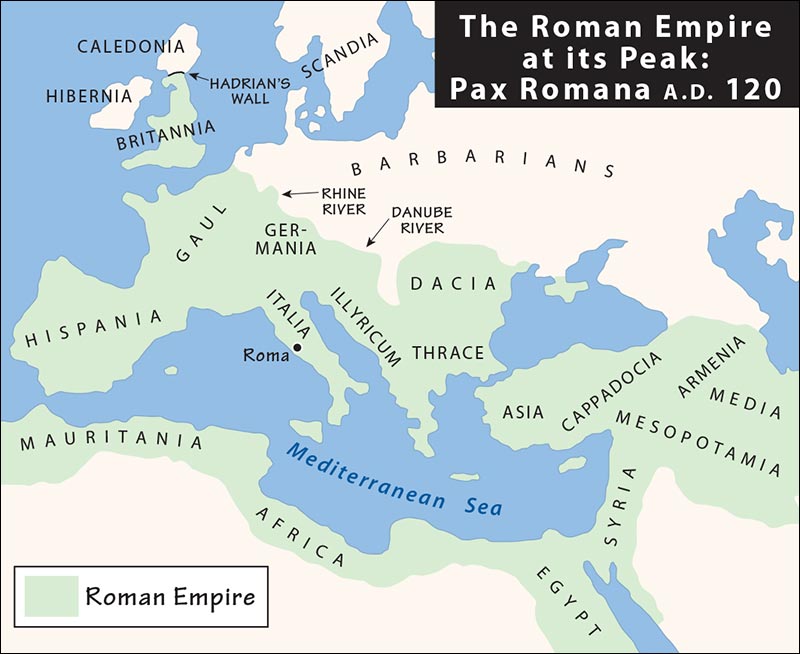

Map: The Roman Empire at Its Peak: Pax Romana A.D. 120

THE ROMAN EMPIRE (c. A.D. 1-500)

DECLINE AND FALL (A.D. 200-500)

PROSPERITY AND POLITICS (A.D. 1000-1300)

Map: Italian History & Art Timeline

ITALY UNITES—THE RISORGIMENTO (1800s)

Italy has a lot of history, so let’s get started.

A she-wolf breastfed two human babies, Romulus and Remus, who grew to build the city of Rome in 753 B.C.—you buy that? Closer to fact, farmers and shepherds of the Latin tribe settled near the mouth of the Tiber River, a convenient trading location. The crude settlement was sandwiched between two sophisticated civilizations—Greek colonists to the south (Magna Grecia, or greater Greece), and the Etruscans of Tuscany, whose origins and language are largely still a mystery to historians (for more on the Etruscans, see here).Baby Rome was both dominated and nourished by these societies.

When an Etruscan king raped a Roman woman (509 B.C.), her husband led a revolt, driving out the Etruscan kings and replacing them with elected Roman senators and (eventually) a code of law (Laws of the Twelve Tables, 450 B.C.). The Roman Republic was born.

Located in the center of the peninsula, Rome was perfectly situated for trading salt and wine. Roman businessmen, backed by a disciplined army, expanded through the Italian peninsula, establishing a Roman infrastructure as they went. Rome soon swallowed up its northern Etruscan neighbors, conquering them by force and absorbing their culture.

Next came Magna Grecia, with Rome’s legions defeating the Greek general Pyrrhus after several costly “Pyrrhic” victories (c. 275 B.C.). Rome now ruled a united federation stretching from Tuscany to the tip of the Italian peninsula, with a standard currency, a system of roads (including the Via Appia), and a standing army of a half-million soldiers ready for the next challenge: Carthage.

Carthage (modern-day Tunisia) and Rome fought the three bitter Punic Wars for control of the Mediterranean (264-201 B.C. and 146 B.C.). The balance of power hung precariously in the Second Punic War (218-201 B.C.), when Hannibal of Carthage crossed the sea to Spain with a huge army of men and elephants. He marched 1,200 miles overland, crossed the Alps, and forcefully penetrated Italy from the rear. Almost at the gates of the city of Rome, he was finally turned back. The Romans prevailed, and, in the mismatched Third Punic War, they burned the city of Carthage to the ground (146 B.C.).

The well-tuned Roman legions easily subdued sophisticated Greece in three Macedonian Wars (215-146 B.C.). Though Rome conquered Greece, Greek culture dominated the Romans. From hairstyles to statues to temples to the evening’s entertainment, Rome was forever “Hellenized,” becoming the curators of Greek culture, passing it down to future generations.

By the first century B.C., Rome was master of the Mediterranean. Booty, cheap grain, and thousands of captured slaves poured in, transforming the economic model from small farmers to unemployed city dwellers living off tribute from conquered lands. The Republic had changed.

With easy money streaming in and traditional roles obsolete, Romans bickered among themselves over their slice of the pie. Wealthy landowners (patricians, the ruling Senate) wrangled with the middle and working classes (plebeians) and with the growing population of slaves, who demanded greater say-so in government. In 73 B.C., Spartacus—a Greek-born soldier-turned-Roman slave who’d been forced to fight as a gladiator—escaped to the slopes of Mount Vesuvius, where he amassed an army of 70,000 angry slaves. After two years of fierce fighting across Italy, the Roman legions crushed the revolt and crucified 6,000 rebels along the Via Appia as a warning.

Amid the chaos of class war and civil war, charismatic generals who could provide wealth and security became dictators—men such as Sulla, Crassus, Pompey...and Caesar. Julius Caesar (100-44 B.C.) was a cunning politician, riveting speaker, conqueror of Gaul, author of The Gallic Wars, and lover of Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt. In his four-year reign, he reformed and centralized the government around himself. Disgruntled Republicans feared that he would make himself king. At his peak of power, they surrounded Caesar in the Senate on the “Ides of March” (March 15, 44 B.C.) and stabbed him to death.

Julius Caesar died, but the concept of one-man rule lived on in his adopted son. Named Octavian at birth, he defeated rival Mark Antony (another lover of Cleopatra, 31 B.C.) and was proclaimed Emperor Augustus (27 B.C.). Augustus outwardly followed the traditions of the Republic, while in practice he acted as a dictator with the backing of Rome’s legions and the rubber-stamp approval of the Senate. He established his family to succeed him (making the family name “Caesar” a title) and set the pattern of rule by emperors for the next 500 years.

In his 40-year reign, Augustus ended Rome’s civil wars and ushered in the Pax Romana: 200 years of prosperity and relative peace. Rome ruled an empire of 54 million people, stretching from Scotland to northern Africa, from Spain to the Euphrates River. Conquered peoples were welcomed into the fold of prosperity, linked by roads, common laws, common gods, education, and the Latin language. The city of Rome, with more than a million inhabitants, was decorated with Greek-style statues and monumental structures faced with marble. It was the marvel of the known world.

The empire prospered on a (false) economy of booty, slaves, and cheap imports. On the Italian peninsula, traditional small farms were swallowed up by large farming and herding estates. In this “global economy,” the Italian peninsula became just one province among many in a worldwide Latin-speaking empire, ruled by an emperor who was likely born elsewhere. The empire even survived the often turbulent and naughty behavior of emperors such as Caligula (r. 37-41) and Nero (r. 54-68).

Rome peaked in the second century A.D. under the capable emperors Trajan (r. 98-117), Hadrian (r. 117-138), and Marcus Aurelius (r. 161-180). For the next three centuries, the Roman Empire declined, shrinking in size and wealth, a victim of corruption, disease, an overextended army, a false economy, and the constant pressure of “barbarian” tribes pecking away at its borders. By the third century, the army had become the real power, handpicking figurehead emperors to do its bidding—in a 40-year span, 15 emperors were first saluted and then assassinated by fickle generals.

Trying to stall the disintegration, Emperor Diocletian (r. 284-305) split the empire into two administrative halves under two equal emperors. Constantine (r. 306-337) solidified the divide by moving the capital of the empire from decaying Rome to the new city of Constantinople (330, present-day Istanbul). Almost instantly, the once-great city of Rome became a minor player in imperial affairs. (The eastern “Byzantine” half of the empire would thrive and live on for another thousand years.) Constantine also legalized Christianity (313), and the once-persecuted cult soon became virtually the state religion, the backbone of Rome’s fading hierarchy.

By 410, “Rome” had shrunk to just the city itself, surrounded by a protective wall. Barbarian tribes from the north and east poured in to loot and plunder. The city was sacked by Visigoths (410) and vandalized by Vandals (455), and the pope had to plead with Attila the Hun for mercy (451). The peninsula’s population fell to six million, trade and agriculture were disrupted, schools closed, and the infrastructure collapsed. Peasants huddled near powerful lords for protection from bandits, planting the seeds of medieval feudalism.

In 476, the last emperor sold his title for a comfy pension, and Rome fell like a huge column, kicking up dust that would plunge Europe into a thousand years of darkness. For the next 13 centuries, there would be no “Italy,” just a patchwork of rural dukedoms and towns, victimized by foreign powers. Italy lay in shambles, helpless.

In 500 years, Italy suffered through a full paragraph of invasions: Lombards (568) and Byzantines (under Justinian, 536) occupied the north. In the south, Muslim Saracens (827) and Christian Normans (1061) established thriving kingdoms. Charlemagne, king of the Germanic Franks, defeated the Lombards, and on Christmas Day, A.D. 800, he knelt before the pope in St. Peter’s in Rome to be crowned Holy Roman Emperor, an empty title meant to resurrect the glory of ancient Rome united with medieval Christianity. For the next thousand years, Italians would pledge nominal allegiance to weak, distant German kings as their Holy Roman Emperor.

Through all the invasions and chaos, the glory of ancient Rome was preserved in the pomp, knowledge, hierarchy, and wealth of the Christian Church. Strong popes (Leo I, 440-461, and Gregory the Great, 590-604) ruled like small-time emperors, governing territories in central Italy called the Papal States.

Italy survived Y1K, and the economy picked up. Sea-trading cities like Venice, Genoa, Pisa, Naples, and Amalfi grew wealthy as middlemen between Europe and the Orient. During the Crusades (e.g., First Crusade 1097-1130), Italian ships ferried Europe’s Christian soldiers eastward, then returned laden with spices and highly marked-up luxury goods from the Orient. Trade spawned banking, and Italians became capitalists, loaning money at interest to Europe’s royalty. Italy pioneered a new phenomenon in Europe—cities (comuni) that were self-governing commercial centers. The medieval prosperity of the cities laid the foundation of the future Renaissance.

Politically, the Italian peninsula was dominated by two rulers—the pope in Rome and the German Holy Roman Emperor (with holdings in the north). Italy split into two warring political parties: supporters of the popes (called Guelphs, centered in urban areas) and supporters of the emperors (Ghibellines, popular with the rural nobility).

In 1309, the pope—enticed by France, Europe’s fast-rising power—moved from Rome to Avignon, France. At one point, two rival popes reigned, one in Avignon and the other in Rome, and they excommunicated each other. The papacy eventually returned to Rome (1377), but the schism created a breakdown in central authority that was exacerbated by an outbreak of bubonic plague (Black Death, 1347-1348), which killed a third of the Italian population.

In the power vacuum, new players emerged in the independent cities. Venice, Florence, Milan, and Naples were under the protection and leadership of local noble families (signoria) such as the Medici in Florence. Florence thrived in the wool and dyeing trade, which led to dominance in international banking, with branches in all of Europe’s capitals. A positive side effect of the terrible Black Death was that the now-smaller population got a bigger share of the land, jobs, and infrastructure. By century’s end, Italy was poised to enter its most glorious era since antiquity.

The Renaissance (Rinascimento)—the “rebirth” of ancient Greek and Roman art styles, knowledge, and humanism—began in Italy (c. 1400) and spread through Europe over the next two centuries. Many of Europe’s most famous painters, sculptors, and thinkers—Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael, etc.—were Italian.

It was a cultural boom that changed people’s thinking about every aspect of life. In politics, it meant an eventual rebirth of Greek ideas of democracy. In religion, it meant a move away from Church dominance and toward the assertion of man (humanism) and a more personal faith. Science and secular learning were revived after centuries of superstition and ignorance. In architecture, it was a return to the balanced columns and domes of Greece and Rome. In painting, the Renaissance meant 3-D realism.

Italians dotted their cities with publicly financed art—Greek gods, Roman-style domed buildings. They preached Greek-style democracy and explored the natural world. The cultural boom was financed by thriving trade and lucrative banking. During the Renaissance, the peninsula once again became the trendsetting cultural center of Europe.

In May 1498, Vasco da Gama of Portugal landed in India, having found a sea route around Africa. Italy’s monopoly on trade with the East was broken. Portugal, France, Spain, England, and Holland—nation-states under strong central rule—began to overtake decentralized Italy. Italy’s once-great maritime cities now traded in an economic backwater, just as Italy’s bankers (such as the Medici in Florence) were going bankrupt. While the Italian Renaissance was all the rage throughout Europe, it declined in its birthplace. Italy—culturally sophisticated but weak and decentralized—was ripe for the picking by Europe’s rising powers.

Several kings of France invaded (1494, 1495, and 1515)—initially invited by Italian lords to attack their rivals—and began divvying up territory for their noble families. Italy also became a battleground in religious conflicts between Catholics and the new Protestant movement. In the chaos, the city of Rome was brutally sacked by foreign mercenaries (1527).

For the next two centuries, most of Italy’s states were ruled by foreign nobles, serving as prizes for the winners of Europe’s dynastic wars. Italy ceased to be a major player in Europe, politically or economically. Italian intellectual life was often cropped short by a conservative Catholic Church trying to fight Protestantism. Galileo, for example, was forced by the Inquisition to renounce his belief that the earth orbited the sun (1633). But Italy did export Baroque art (Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini) and the budding new medium of opera.

The War of the Spanish Succession (1713)—a war in which Italy did not participate—gave much of northern Italy to Austria’s ruling family, the Habsburgs (who now wore the crown of Holy Roman Emperor). In the south, Spain’s Bourbon family ruled the Kingdom of Naples (known after 1816 as the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies), making it a culturally sophisticated but economically backward area, preserving a medieval, feudal caste system.

In 1720, a minor war (the War of Austrian Succession) created a new state at the foot of the Alps, called the Kingdom of Sardinia (a.k.a. the Kingdom of Piedmont, or Savoy). Ruled by the Savoy family, this was the only major state on the peninsula that was actually ruled by Italians. It proved to be a toehold to the future.

In 1796, Napoleon Bonaparte swept through Italy and changed everything. He ousted Austrian and Spanish dukes, confiscated Church lands, united scattered states, and crowned himself “King of Italy” (1805). After his defeat (1815), Italy’s old ruling order (namely, Austria and Spain) was restored. But Napoleon had planted a seed: What if Italians could unite and rule themselves like Europe’s other modern nations?

For the next 50 years, a movement to unite Italy slowly grew. Called the Risorgimento—a word that means “rising again”—the movement promised a revival of Italy’s glory. It started as a revolutionary, liberal movement—taking part in it was punishable by death. Members of a secret society called the Carbonari (led by a professional revolutionary named Giuseppe Mazzini) exchanged secret handshakes, printed fliers, planted bombs, and assassinated conservative rulers. Their small revolutions (1820-1821, 1831, 1848) were easily and brutally slapped down, but the cause wouldn’t die.

Gradually, Italians of all stripes warmed to the idea of unification. Whether it was a united dictatorship, a united papal state, a united kingdom, or a united democracy, most Italians could agree that it was time for Spain, Austria, and France to leave.

The movement coalesced around the Italian-ruled Kingdom of Sardinia and its king, Victor Emmanuel II. In 1859, Sardinia’s prime minister, Camillo Cavour, cleverly persuaded France to drive Austria out of northern Italy, leaving the region in Italian hands. A plebiscite (vote) was held, and several central Italian states (including some of the pope’s) rejected their feudal lords and chose to join the growing Kingdom of Sardinia.

After victory in the north, Italy’s most renowned Carbonari general, Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807-1882), steamed south with a thousand of his best soldiers (I Mille) and marched on the Spanish-ruled city of Naples (1860). The old order simply collapsed. In two short months, Garibaldi had achieved a seemingly impossible victory against a far superior army. Garibaldi sent a one-word telegram to the king of Sardinia: “Obbedisco” (I obey). The following year, an assembly of deputies from throughout Italy met in Turin and crowned Victor Emmanuel II “King of Italy.” Only the pope in Rome held out, protected by French troops. When the city finally fell—easily—to the unification forces on September 20, 1870, the Risorgimento was complete. Italy went ape.

The Risorgimento was largely the work of four men: Garibaldi (the sword), Mazzini (the spark), Cavour (the diplomat), and Victor Emmanuel II (the rallying point). Today, street signs throughout Italy honor them and the dates of their great victories.

Italy—now an actual nation-state, not just a linguistic region—entered the 20th century with a progressive government (a constitutional monarchy), a collection of colonies, and a flourishing northern half of the country. In the economically backward south (the Mezzogiorno), millions of poor peasants emigrated to the Americas. World War I (1915-1918) left 650,000 Italians dead, but being on the winning Allied side, survivors were granted possession of the alpine regions. In the postwar cynicism and anarchy, many radical political parties rose up—Communist, Socialist, Popular, and Fascist.

Benito Mussolini (1883-1945), a popular writer for socialist and labor-union newspapers, led the Fascists. (“Fascism” comes from Latin fasci, the bundles of rods that symbolized unity in ancient Rome.) Though only a minority (6 percent of the parliament in 1921), they intimidated the disorganized majority with organized violence by black-shirted Fascist gangs. In 1922, Mussolini seized the government (see “The March on Rome” sidebar) and began his rule as dictator for the next two decades.

Mussolini solidified his reign among Catholics by striking an agreement with the pope (Concordato, 1929), giving Vatican City to the papacy, while Mussolini ruled Italy with the implied blessing of the Catholic Church. Italy responded to the great worldwide Depression (1930s) with big public works projects (including Rome’s subway), government investment in industry, and an expanded army.

Mussolini allied his country with Hitler’s Nazi regime, drawing an unprepared Italy into World War II (1940). Italy’s lame army was never a factor in the war, and when Allied forces landed in Sicily (1943), Italians welcomed them as liberators. The Italians toppled Mussolini’s government and surrendered to the Allies, but Nazi Germany sent troops to rescue Mussolini. The war raged on as Allied troops inched their way north against German resistance. Italians were reduced to dire poverty. In the last days of the war (April 1945), Mussolini was captured by the Italian resistance. They shot him and his girlfriend and hung their bodies upside down in a public square in Milan.

At war’s end, Italy was physically ruined and extremely poor. The nation rebuilt in the 1950s and 1960s (the “economic miracle”) with Marshall Plan aid from the United States. Many Italian men moved to northern Europe to find work; many others left farms and flocked to the cities. Italy regained its standing among nations, joining the United Nations, NATO, and what would later become the European Union.

However, the government remained weak, changing on average once a year, shifting from right to left to centrist coalitions (it’s had 64 governments since World War II). Afraid of another Mussolini, the authors of the postwar constitution created a feeble executive branch; without majorities in both houses of parliament nothing could get done. All Italians acknowledged that the real power lay in the hands of backroom politicians and organized crime—a phenomenon called Tangentopoli, or “Bribe City.” The country remained strongly divided between the rich, industrial north and the poor, rural south.

Italian society changed greatly in the 1960s and 1970s, spurred by the liberal reforms of the Catholic Church at the Vatican II conference (1962-1965). The once-conservative Catholic country legalized divorce and contraception, and the birth rate plummeted. In the 1970s, the economy slowed thanks to inflation, strikes, and the worldwide energy crisis. Italy suffered a wave of violence from left- and right-wing domestic terrorists and organized crime, punctuated by the assassination of former Prime Minister Aldo Moro (1978). A series of coalition governments in the 1980s brought some stability to the economy.

In the early 1990s, the judiciary launched a campaign to rid politics of corruption and Mafia ties. The investigation sent a message that Italy would no longer tolerate evils that were considered necessary just a generation earlier. As home to the Vatican, Italy keeps a close watch on the Catholic Church, which has had its own set of scandals.

The Great Recession of the late 2000s and early 2010s hit the Italian economy hard and led to the downfall of Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi—the controversial owner of many of Italy’s media outlets and the country’s richest person. Like other European nations, Italy had run up big deficits by providing comfy social benefits without sufficient tax revenue. By the end of 2011, Italy’s debt load was the second worst in the euro zone, behind only Greece. To calm the markets, Berlusconi resigned.

The caretaker government imposed severe austerity measures. Italy wanted change, and got it when 39-year-old Matteo Renzi, who had entered politics as mayor of Florence, took over as prime minister in early 2014—the youngest prime minister in modern Italian history. For a time, the dynamic Renzi was immensely popular. Later, though, he was dogged by a persistently sluggish economy, repeated corruption scandals, and an immigration crisis brought on by the influx of people streaming from across the Mediterranean seeking a better life in Europe. In late 2016 Renzi resigned after Italians rejected his far-reaching constitutional reforms.

The new prime minister—journalist and former Rome mayor Paolo Gentiloni—served as Minister of Foreign Affairs under Renzi and is a member of the same political party. Some observers say the 62-year-old Gentiloni is just a placeholder until Renzi returns to power in the next elections.

Italy’s economy is on the mend, and the nation remains the third-largest economy in the eurozone (and world’s eighth largest exporter). But even as the economy grows, unemployment remains high at about 12 percent—with youth unemployment at about 37 percent, double the European average.

As you travel through Italy today, you’ll encounter a fascinating country with a rich history and a per-capita income that comes close to its neighbors to the north. Despite its ups and downs, Italy remains committed to Europe...yet it’s as wonderfully Italian as ever.

To learn more about Italian history, consider Europe 101: History and Art for the Traveler, written by Rick Steves and Gene Openshaw (available at www.ricksteves.com).