Chapter 3. People Build Connections

IN OCTOBER 2007, SILICON VALLEY WAS BUZZING. Microsoft’s $240 million advertising deal and investment in Facebook, for a 1.6% equity share, valued the 3-year-old company at a total enterprise valuation of $15 billion (compared to Google’s public stock valuation of $181 billion at a stock price of $600 a share). Some observers immediately dismissed the number as a throwback to the dot-com bubble, the “irrational exuberance” of naïve and enthusiastic stock purchasers in the late 1990s. But the “smart money” venture capitalists and private-equity firms took notice.

After all, Microsoft and its investment bankers were sophisticated mergers-and-acquisitions dealmakers. There were whispers of a closed round of bidding where Google’s outright offer of $11 billion had been the “floor” for anteing up, with all of the large multinationals and media firms expressing interest. From the point of view of Facebook and Microsoft, the final deal was a win-win. Facebook’s privately held stock was ratcheted up as if it were already publicly valued by the $240 million transaction, and Microsoft’s stock gained as well upon the announcement.

Financial deal making aside, what kind of financial analysis might tell us whether Facebook was worth $15 billion? Let’s turn to the generalized framework of the customer-based financial valuation model we explained in Chapter 1, in valuing Netflix as the sum total of the lifetime value in subscription fees of its installed customer base (a methodology originally developed for cable and cell phone subscription companies).

A Web 2.0 online social network like Facebook has three immediate and powerful advantages over those previous customer-based enterprises:

Facebook has proven itself to be a much more powerful customer-acquisition engine, using its viral social marketing and distribution online to attract 47 million customers in less than 3 years.

These 47 million free users are highly interactive and engaged with Facebook.

Facebook is a social network advertising platform. The value of this installed base of 47 million free users is immediately monetized through target advertising revenues—cash flows in much faster and more predictably than it would from monthly subscription fees. More importantly, the cross-network value to the advertiser is already multiplied by these users’ uploaded collective user value—the huge database/inventory storehouse of digitized personal and social information, photos, bios, interests, music, content, applications, preferences, and lists of friends they have volunteered to upload openly to Facebook.

Just as in the Flickr case, Facebook users had a mostly individual or social motivation for developing and sharing a digitized personal and contact database. However, their openness benefits and contributes to the positive network effects and value of the system both as a one-stop social communication/directory site and also as a treasure trove for algorithmic, targeted advertising and social-influence marketing. If Google’s average revenue per user is $15 in pay-per-click ad-revenue monetization, Facebook hopes to do even better by leveraging Microsoft’s technology resources and the advertising/IM platforms developed with MSN.

Google may know my keyword search queries, Amazon may have my wish list, and Flickr may know which photos I tag as interesting or cute—but Facebook knows my face, the photos of my friends, my personally created profile, the evolution of my digital persona, and my interactive social milieu.

Facebook could skyrocket because the emergence and rapid growth of online social networks have made it possible for people to communicate and work together in ways that simply weren’t possible before. People with common goals and interests—even highly specialized and unusual pursuits—can find each other more easily and build groups. One person can help vast numbers of people without ever knowing who she has helped. These recent developments build on the possibilities that online social networks have opened and lead to new business opportunities.

Social Roles: Online and Offline

In The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference (Back Bay Books), Malcolm Gladwell tells the story of Paul Revere and William Dawes. Every American schoolkid knows the basics of the story. In April 1775, in Boston, a young stable boy overheard a British army officer tell another that there would be “hell to pay tomorrow.” The stable boy’s news tip was passed to the local silversmith Paul Revere, who mounted his horse and began his famous midnight ride from Boston to Lexington, crying, “The British are coming! The British are coming!” He spread the news like a virus and mobilized a critical mass of neighbors, farmers, and merchants who jumped out of bed and armed themselves.

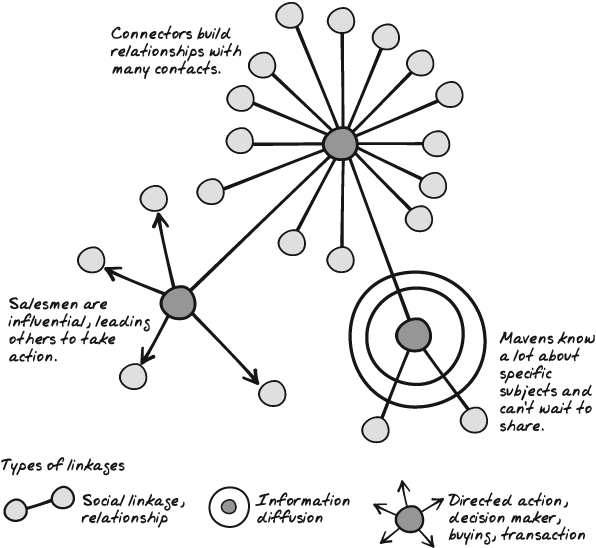

But not many people remember William Dawes. Dawes rode just as far, on a different route, knocking on just as many doors. Why is Paul Revere remembered while William Dawes is not? As Gladwell tells it, because Revere had a gregarious and social personality that could bring people together. Dawes had only ordinary social abilities. Gladwell suggests that certain kinds of people matter to “tipping” word-of-mouth epidemics; we’re all familiar with them in our everyday offline social world (see Figure 3-1):

- Connectors

The “social glue” who know and want to introduce you to everyone “you should know” whether for matchmaking or career mentoring

- Mavens

“Information brokers” who can’t wait to tell you about the best deals and give you advice on where to stay and what to buy

- Salesmen

“Evangelists” who get you to act and convince you to buy

Paul Revere was a potent combination of connector, maven, and salesman, with late-breaking news to broadcast, thanks to the news tip from the stable boy—who was a natural maven.

You probably know some connectors, mavens, and salesmen, especially if you participate in business networking groups or community organizations. The combinations of people playing these different roles in social networks are critically important for convincing a broad audience to use a company’s services.

Some of the most popular services on the Web today are online social networks built to help people find each other, share their stories, and connect. Their business lessons apply to a broad group of situations, whether or not you plan to run a social network site yourself. Flickr, for example, is most commonly thought of as a photo-sharing site, not a social networking site, but the social aspect is critical to its success. Even more simply, Amazon relies on rankings from readers to give its reviewers a sense of enhanced status and recognition.

How Online Changes Social Networking

In some ways, online networking is much like offline networking—the social skills you know from the offline world are still helpful. However, connecting by web sites and email makes it more like a network of people who are all in the same room, ready to make introductions without the small talk. It’s not a replacement for face-to-face conversation, but it’s certainly a supplement that changes the rules.

Two things change the “tipping” of word-of-mouth epidemics in the online world:

The availability of personal content uploaded online

The speed of connecting online to someone who you don’t know but want to be linked to or get a message to

Online is a small world. With just a few clicks, users can reach people they want to know. Increasingly, people get their first impressions from online rather than offline encounters.

The Shift from Snailmail to Hotmail

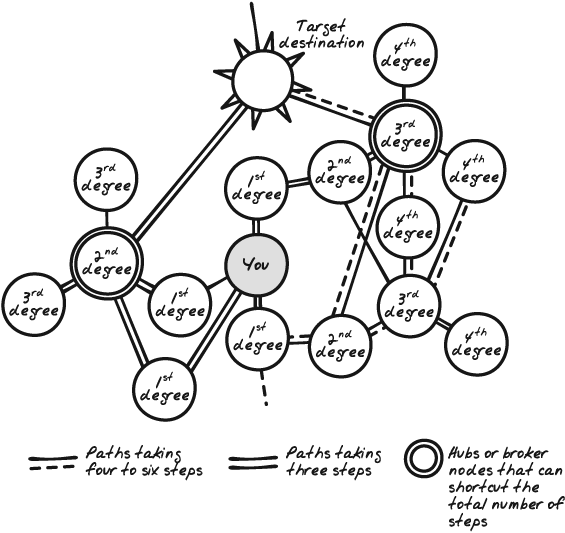

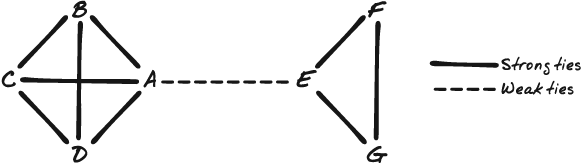

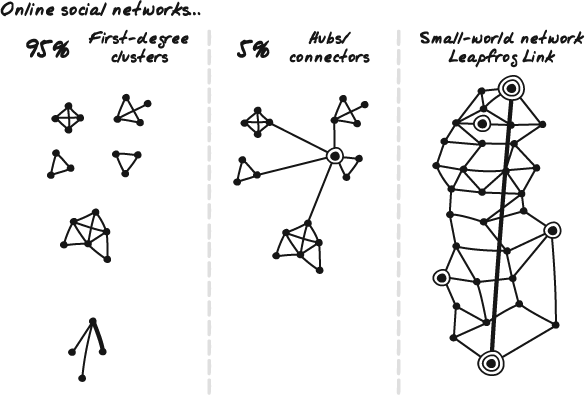

In the late 1960s, the sociologist Stanley Milgram investigated what came to be known as the “small-world phenomenon.” He conducted an experiment to find connections linking people in the United States who did not know each other. He gave a letter to someone in Nebraska, with instructions that the letter had to reach a particular person in Massachusetts. The first person was told only basic information about the “target,” such as his address and occupation, and was told to give or send the letter to someone she knew on a first-name basis, and that person was given the same direction, to deliver the letter to the target as efficiently as possible. Anyone who received the letter would follow the same instructions until the target was reached. Through repeated trials, Milgram found that it took five or six “steps,” on average, to get a letter from Nebraska to Massachusetts. This formed the basis for the well-known concept of “six degrees of separation” (shown in Figure 3-2).

In his book Six Degrees (W. W. Norton & Company), Duncan Watts points out that certain paths were considerably shorter because the Milgram package reached a “hub” or “broker” node that shortcut the average six steps. Figure 3-2 illustrates this by putting an additional circle on the hubs or broker nodes and showing the different paths on the right and left side.

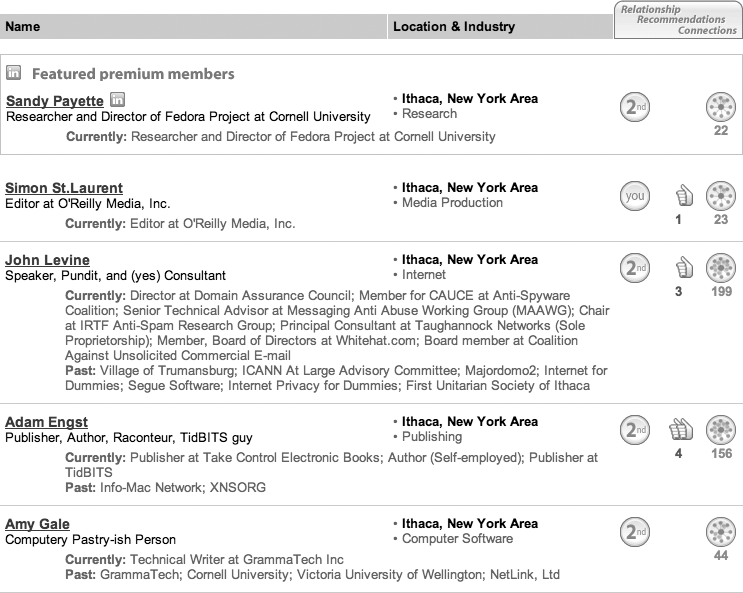

In the online world, using LinkedIn or a similar network, members can easily browse lists and profiles of past business contacts who now live in Boston or who are stockbrokers in Massachusetts, and see on a map how many steps it would take to get an email introduction forwarded to the stockbroker online through first-degree contacts (see Figure 3-2).For example, LinkedIn will tell you how many steps there are between you and your destination mailbox (as shown in Figure 3-2).

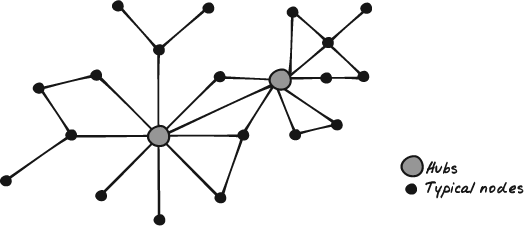

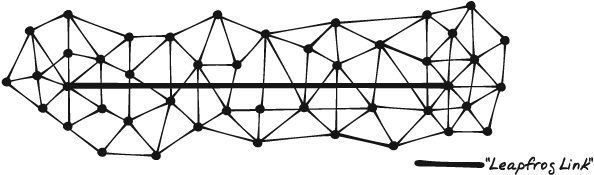

Online social and professional networks use the connections found in the offline world and magnify them proportionally. In the LinkedIn system, the intermediary roles of the connectors, mavens, and salesmen remain basically the same but are enhanced by orders of magnitude. Easy and speedy digital connectivity shifts the focus in online social networking from creating, mapping, and expanding your network toward finding new ways to exploit, capture value in, and monetize your own network (see social network mappings in Figure 3-3, Figure 3-4, and Figure 3-5).

According to an MIT Tech Review article,[20] Marcus Colombano, a media and technology marketing consultant in San Francisco, read about a company he thought should be his client. He popped its name into LinkedIn and found he was connected to four people with contacts at that company. He wrote up a proposal and sent it to a friend who had a contact who knew the CEO. Four hours later, he got an email from the CEO requesting a meeting (see Figure 3-6).

Do these speedy introductions lead to revenue for the startups that create and run these online networking platforms? The surprising answer is yes. Perhaps even more surprising, the case of LinkedIn, examined more closely later in this chapter, gives us a pretty good idea of what online connectors, mavens, and salesmen are willing to pay for access to these visibly more efficient search and linkage networks, as well as an idea of when the network’s best move is to offer some services for free. Of course, this presents new choices for the online social and professional networking companies that provide these services and platforms. Should advertisers or sponsors pay the freight or “freemium” users who are willing to pay for a “leapfrog link”?

Connectors, Mavens, and Salesmen at Broadband Speed

The Web and related technologies help online connectors, salesmen, and mavens reach an exponentially larger audience, more frequently, more easily, and almost instantaneously. In comparison:

Offline connectors develop relationships over time in face-to-face meetings with many other individuals. Online connectors benefit from using the Web, IM, email, audio, and video to connect directly to more people, more frequently, and more interactively.

Offline mavens have in-depth knowledge about a particular subject and are eager to share it. Online mavens have an instantaneous means of broadcasting and publishing the knowledge they want to share and become information providers and brokers through referrals, reviews, forums, and communities that supplement emails, syndication (RSS) feeds, blogs, and wikis.

Offline salesmen influence people to take action; online salesmen do the same thing but are supported by many different interactive formats and media.

Social networks moved online steadily, but businesses took different approaches and found themselves with different groups of people doing different kinds of things. Business networkers needed one set of features, whereas social networkers needed another. Varying preferences led people to cluster on different sites, to move from site to site, and even use multiple sites at the same time.

How Many Customers and How Quickly?

Facebook, YouTube, Skype, MySpace, and Flickr show that a Web 2.0 company’s business and financial valuation depends on the number of users and how quickly those users accept, adopt, and bring their positive network effects to a new online service. In the social networks and advertising platforms, these users can be monetized immediately, through advertising and n-sided market sponsorship. Clickstreams, average revenue per user (ARPU), individual customer profitability, and advertising ROI can be tracked with web analytics daily and even hourly.

Rogers Adoption Curve

In the study of high-tech marketing and management of innovation, the Rogers Adoption Curve is often used to explain the rate of adoption of a new technology or product.

In 1962, Everett M. Rogers, in his book Diffusion of Innovations, gauged how populations adopt new products and technologies. He later suggested that five factors explain why some new products succeed with high growth rates and rapid customer adoption and others fail:

- Relative advantage

How much better the new product is compared with the old one. Angioplasty is 10 times more effective than open-heart surgical bypasses, it is less invasive, and it allows faster recovery.

- Compatibility

If a new product fits with current values and usage, it broadens the initial audience. Major changes are more risky and appeal to a relatively smaller group of early adaptors, independent thinkers, and innovators.

- Complexity

Ease of use and understanding of features make adoption faster and easier.

- Trialability

Products can sell themselves if customers experiment with them and get hooked by the personal experience. Free trials, demos, and test drives reduce the risk.

- Observability

How visible product usage and impact are to others. Social influence plays a role in adoption of the very visible iPod and the hybrid Prius automobile. Preventative medicine and tax-preparation software usage is less visible and requires a more targeted effort to market virally.

The power of Web 2.0 technologies coupled with a freemium n-sided business model shows up in all five of these factors for Facebook, compounding its advantages and triggering its hypergrowth rate of adoption.

- Relative advantage

Facebook offers the perception of increased or new benefits—especially in greater reach. If a large number of campuses are connected to the Facebook directory and applications, users can keep up with high-school friends who went elsewhere for college and renew acquaintances with long lost connections.

- Compatibility

Facebook’s web application was easier and more instantaneous than the printed college facebook. This was very comfortable for a digital youth generation that is used to being always online, instant messaging constantly, being connected wirelessly with their friends through various devices and media.

- Complexity

Facebook was easy to use, with information pushed to users through RSS feeds.

- Trialability

Users could try Facebook for free, paid for by n-sided cross-network effects.

- Observability

Observability is built into the company name—users could easily identify who was on and using the Facebook “wall” by name, frequent messages, and uploaded photos. Facebook viral applications raised this observability to a whole new level of referral, subtle peer/friend pressure, and social influence. Not only were friends inviting friends to “join the party” and play an application with them—they got constant numerical updates and reminders of how many of their circle of friends were participating. Why not click and try it out for yourself? How bad could it be if 80% of your close friends were doing it? Talk about a bandwagon effect.

The Rogers Adoption Curve provides a useful framework to evaluate where on the adoption curve your product or service is getting roadblocked. For example, Geoff Moore’s book Crossing the Chasm (HarperBusiness) identifies a marketing “chasm” between the early innovators and adopters and the mainstream. As mentioned in Chapter 1, Web 2.0 companies like Flickr have attempted to close that chasm by using a freemium strategy and social network effects.

However, there are no variables or factors in Rogers framework that directly take “social influence” and the peer-to-peer pressure of online social networks into account. It’s difficult to quantify the impact of viral marketing, costless distribution, or viral distribution on adoption or growth rate. Nor are there quantifiable and standardized growth and diffusion patterns so that different kinds of products, services, channels, and marketing strategies can be measured and compared. The Rogers Adoption Curve and model rely on some fundamental assumptions about new technology adopters and markets:

The available population and market of adopters for all new technologies, products, and services follow a normal distribution or bell curve characterized by 2.5% innovators.

The key attributes for market projection are individual-user-centered. Factors to consider are the behavior and risk profile of the individual user toward new technology, interest in new things, risk aversion, etc.

Even in the more detailed product-related model, user behavior is independent.

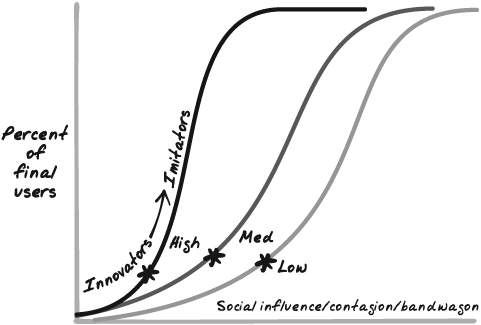

The Bass Diffusion Curve

The Bass Diffusion Curve is an important update to the Rogers model because it provides a radically different framework of customer/user adoption rates based on social influence. Social influence is arguably the key factor completely missing from the Rogers Adoption Curve. It also uses an exponential form, mathematically speaking, which makes the modeling assumption that the process of diffusion is viral, as in an epidemic. The general shape of the Bass Curve reflects a type of propagation through a population with a modified power law distribution. (And again, for quantitative projections of how many customers will adopt a new product and how quickly, the Bass Curve has been regularly empirically tested and validated.)

Frank Bass introduced this model in 1969 in a famous paper titled “A New Product Growth Model for Consumer Durables,” published in the Management Science journal. The key concepts are intuitive and simple: some users start the process by adopting a new product independently of the actions of others; others are influenced to adopt the innovation when they see others using it, being socially influenced by those who have already adopted the product.

The simple version of the Bass model has only three major parameters—m, p, and q:

m is the estimated total number of eventual adopters.

p is the variable describing the rate of growth of first-time adopters who act independently.

q is the variable describing the rate of growth of first-time adopters who are influenced by social effects and interpersonal influence.

The level of social influence can be expressed as the ratio of q/p. If the ratio is low, fewer social “followers” or “imitators” are influenced by the early independent adopters. If the ratio is medium or high, a substantially larger proportion of the potential first-time adopters in the market are strongly influenced by the initial group of independent adopters.

A few consumer durable goods examples make the curve intuitively easy to understand. The Bass Curve has been used to gauge the adoption of washing machines, TVs, leaf blowers, and cell phones.

The p in washing machines and TVs is relatively high, but the q is relatively low, because although these consumer items may be highly useful, they are not easily observable or conspicuous status items, the way cars might be.

Leaf blowers have a surprisingly high q/p ratio, and adoption grew much faster than expected—potentially because they are highly observable in their weekend usage and in their effect on neighborhood sidewalks and walkways, while not being very costly to purchase or try.

Cell phones had a higher q and p than wired phones.

These kinds of examples provide analogies in making marketing predictions for newer technologies. So, for example, an analyst might estimate the diffusion pattern of satellite radio to be similar in shape to that for satellite TV but faster because of ease of replacement and lower cost.

But what about online viral marketing and distribution?

The size of the Oakland Hills, California, firestorm in 1991 that burned more than 2,000 homes had more to do with the hot dry season and the gusty Santa Ana winds that spread the fire than with the actual spark that started it. Structural and coincidental factors were at work. In a similar way, fads and social influence “cascades” are triggered by influencers or sparks, but they require the right conditions to spread with explosive speed.

Highly influential people—celebrities like Oprah Winfrey—can make a book an overnight bestseller. But thousands of computer simulations reveal that global cascades are more likely to be triggered by accidental and unintentional influencers within a receptive social network structure. A cascade needs just enough of a critical mass of easily influenced people to propagate a chain reaction, one degree of separation at a time.

Sometimes, personal characteristics make a difference. Rogers’ risk profiling and psycho-graphic profiling of early adopters, mainstream users, and laggards—combined with Moore’s explanation of “crossing the chasm”—does a good job of explaining many high-tech marketing successes and failures. However, online web social networks make it easy for a relatively small number of users—like you and me—to trigger network effects.

Do we know how to “seed” and shape these new product adoption cascades or epidemics?

Not yet, but current research findings seem to indicate that the raw number of early users and their first-degree “friend” or online “buddy” linkages, along with their social interactivity or frequency of contact, someday may be more critical in this “online cascade” viral distribution model than highly paid influentials such as celebrities or brokers.

LinkedIn and Facebook are great Web 2.0 examples of the newer models of applied online social networks. LinkedIn offers a fascinating online business application of small-world networks and social network analysis mapping brought online. In contrast, Facebook provides a natural example of large-scale diffusion and node-to-node cascading behavior in social networks.

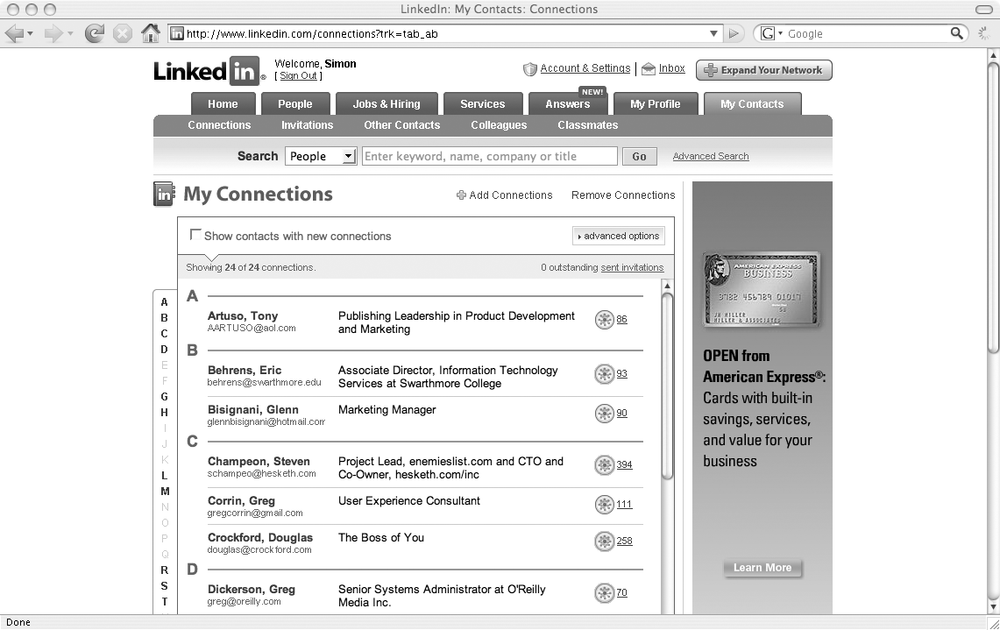

LinkedIn: The Rolodex Moves Online

For a lot of people, LinkedIn defines business networking. Its contact management enables people to connect to each other easily, offering a self-updating contact list that helps them find the connections they need. It even looks a bit like a classic address book, as shown in Figure 3-7.

Even this simple address book, however, leads into the possibilities that electronic contact management offers. Note the icons in the right column, just to the left of the ad. The address book tells users how many contacts their contacts have, letting them see at a glance how well-connected their contacts are. Clicking on that icon displays the other person’s contacts, making it easy for users to dive into a network of people they might be interested in knowing.

Searches also let users find more people they might want to contact and tells them how many degrees of separation stand between their personal contacts and them, as shown in Figure 3-8.

The relationship column shows how many degrees of separation stand between the searcher and the contact. Clicking on a name brings up a profile, with a “Get introduced through a connection” option. Mutual friends can then help establish a more direct LinkedIn connection.

LinkedIn put members’ existing networks of business relationships and business contact information onto the Web. By putting members’ rolodexes (the rotating file devices used to store business contact information such as business cards) online, these networks became more easily searchable, and the networks of people who knew each other could be easily connected and linked. The signup or joining process had a strong viral online word-of-mouth effect—anyone could become a member, but 90% of members joined in response to an email invitation from an existing member.

Most businesspeople have received scores of email invitations to join LinkedIn or Plaxo, and now Facebook. The email invitation allowed you to click through to a membership page. Then you could upload a simple profile with name, region, and industry, or a longer bio with photo, education, career, and other professional affiliations. As soon as the profile was loaded, new members were linked to the member who invited them and could then extend their networks by inviting others to join, asking existing members to connect to them, or accepting invitations to connect from existing members. Connections had to be agreed to by both parties, and members were free to disconnect from any unwanted contact.

LinkedIn illustrates some challenges that first- and second-generation online social networking sites faced:

Growing quickly

Creating trust and maintaining privacy within an open or professional network

Monetizing social networks—deciding how to price services and who should receive free services

According to a Harvard Business School case study on LinkedIn (Mikolaj Jan Piskorski), Stanford grads Reid Hoffman and Konstantin Guericke started discussing online professional communities in 1997. The founders invited their contacts, who invited others and yet others onto the beta site. By April 2004, the network had 550,000 members. LinkedIn was funded by Sequoia Capital ($4.7 million), Greylock ($10 million), and well-known angel investors such as Marc Andreessen (cofounder of Netscape) and Peter Thiel (cofounder of PayPal).

Rapid Growth

In 2004, there were 12,000 requests for introductions per month; 85% of requests approved by all the intermediaries were accepted by the target recipient. By mid-2005, requests for introductions had reached 25,000, and acceptance rates had increased slightly to 87%. As the membership base grew, so did search activity. Members executed 2 million searches in April 2004. By mid-2005, that number had more than doubled to 5 million.

LinkedIn’s ability to track the electronic activities and linkages of its membership gives us new insights into online social networks. The Harvard Business School case study revealed an unexpected usage pattern:

- Online relationship managers

Ninety percent of LinkedIn users are first-degree contact managers and treat LinkedIn like an improved rolodex or Microsoft Oulook inbox. They maintain their own lists of close contacts, adding new contacts as they find them in the offline world through input, conferences, new jobs, and meetings. The main features that LinkedIn provides are automatic updates and easy organization.

- Online connectors

Online networkers, like their real-world counterparts, are actively seeking new contacts. Five percent of LinkedIn users are online connectors or brokers.

Networkers, unlike relationship managers, often send invitations to people they never actually meet in the offline world. The strength of the bond is less important for networkers than the general quality of the network—they typically aim for large groups of contacts that they can navigate to find just the right person.

Privacy is also less of an issue for networkers—many of them display their email addresses to allow other people to contact them easily. There’s also something of a competitive streak among this group—TopLinked.com lists the top 50 networkers on LinkedIn, with the most-networked user having 36,480 contacts in October 2007.

- Online salesmen, connectors

The last 5% of users are focused searchers, people seeking contacts that address specific needs. Contactors are often recruiters, analysts, business-development consultants, or salespeople. Like networkers, they find that the value of LinkedIn grows as the number of users climbs, giving them a broad range of people to search for and reach out to.

Contactors typically combine searches with referrals, finding people who fit the profile they need and then tracking them down through their own contact list. Their focus on finding key people makes them especially appreciate—and sometimes find—the “leapfrog link” shown earlier in Figure 3-6.

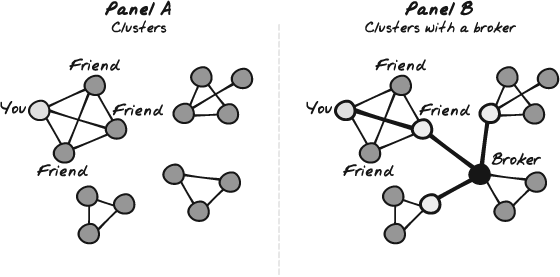

Trust and Degrees of Separation

“A friend of yours is a friend of mine.” The common saying echoes the feeling that most of us have: two degrees of separation can be trusted. After all, you know your friend directly, and he wouldn’t introduce you to someone he didn’t trust or think highly of online or offline. “A friend of a friend of a friend,” however, is three degrees of separation, and already we feel a little less comfortable because we are further from a direct link. On the other hand, LinkedIn realized that allowing the possibility of four degrees of separation between a requestor and a recipient exponentially increased the reach of the system. For example, mathematically, if each contact had 20 ties, a requestor could access 137,180 unique contacts with 4 degrees of separation:

20 contacts × (20 contacts − 0 friends in common − 1)3 [4 degrees of separation−1]

So, although it might be awkward for the “friend of a friend of a friend” to pass along an introduction when he does not know the originator of the message or the recipient, anyone along the path could decline the request anonymously. In mid-2005, LinkedIn announced that monthly requests were 25,000 and acceptance rates were at 87%. Part of the reason for the higher acceptance rate was the added endorsement feature. Members could collect endorsements or testimonials from their contacts, describing their qualifications and performance specific to a particular position or project. In the Harvard Business School case, LinkedIn noted that members were 3 times more likely to select an endorsed member from a search list, and requests initiated by endorsed members were 25% more likely to be accepted by both intermediate connectors in the path and the final target destination.

Monetizing Social Networks

By carefully mapping and separating LinkedIn users into three distinct groups—relationship managers, connectors, and focused searchers—we see that Guericke and Hoffman were able to create a virtual two-sided network system. LinkedIn offers free services to the 90% installed base of relationship managers, while networkers and contactors are willing to pay a per-contact fee, as well as a monthly subscription fees for highly desired premium contact and networking services.

We see a pricing strategy similar to the other freemium cases where one side of the market sponsors or pays for the other, for example, Visa credit cards, eBay, and Google.

Note the importance of the relationship managers. In a classic business model, they might be seen as troubling parasites—90% of customers are using valuable services for free? (They see ads, but nothing makes them click on them, of course.) In LinkedIn’s model, relationship managers may be getting something for free, but they’re also giving LinkedIn the key information it can sell to other people. The cost of supporting those free users, even when it’s 90% of the base, is still less than the income potential from the 10% of paying customers.

LinkedIn makes much of its money by selling members the ability to contact anyone in the network for a fee, through three programs of highly focused feature changes:

LinkedIn kept its free referrals through intermediaries but reduced the degrees of separation from four to three. (Four-degree introductions were often uncomfortable anyway.) This reduced the free services and increased the value of LinkedIn’s paid services.

The new InMail system gave members a way to contact other members directly for a subscription fee. LinkedIn also provided a reputation system so that contactors could demonstrate that their messages were actually appreciated and focused to the right people and not merely paid-for spam.

The new OpenLinkNetwork helped networkers find each other without having to use the formal introduction process. The subscription-based service simplified the kinds of tasks that networkers like to do without changing the rules for relationship managers.

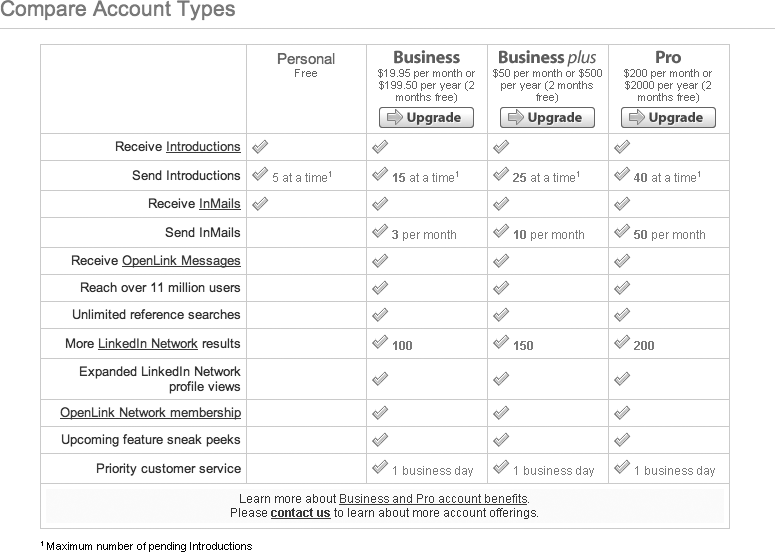

Figure 3-9 shows the features LinkedIn offered in July 2007, along with their price points.

LinkedIn epitomizes the Web 2.0 model of free access to users who help build critical mass, while charging those who seek to use that mass for their own larger purposes. LinkedIn has stayed slim, focusing tightly on a core mission of business connectivity and leaving richer but much more resource-intensive forms of social networking to other companies.

Facebook: Introduce Yourself Online

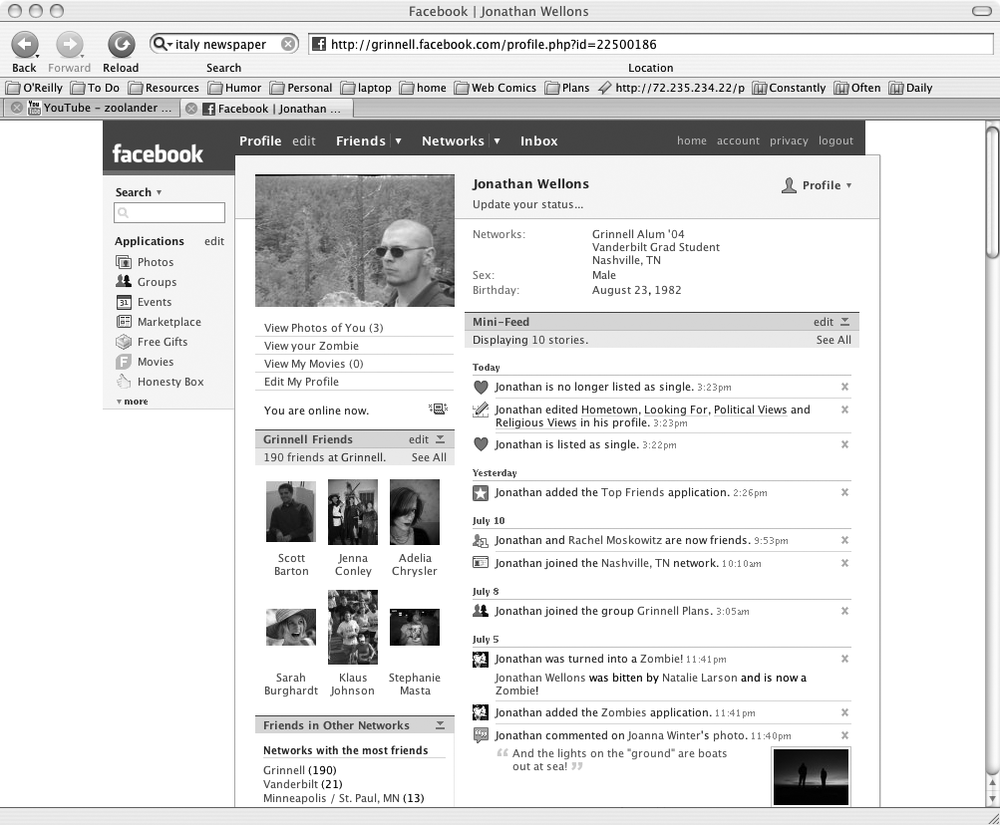

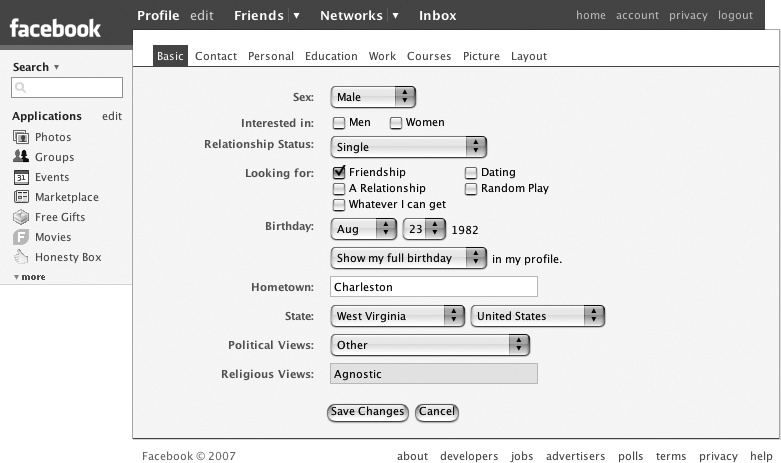

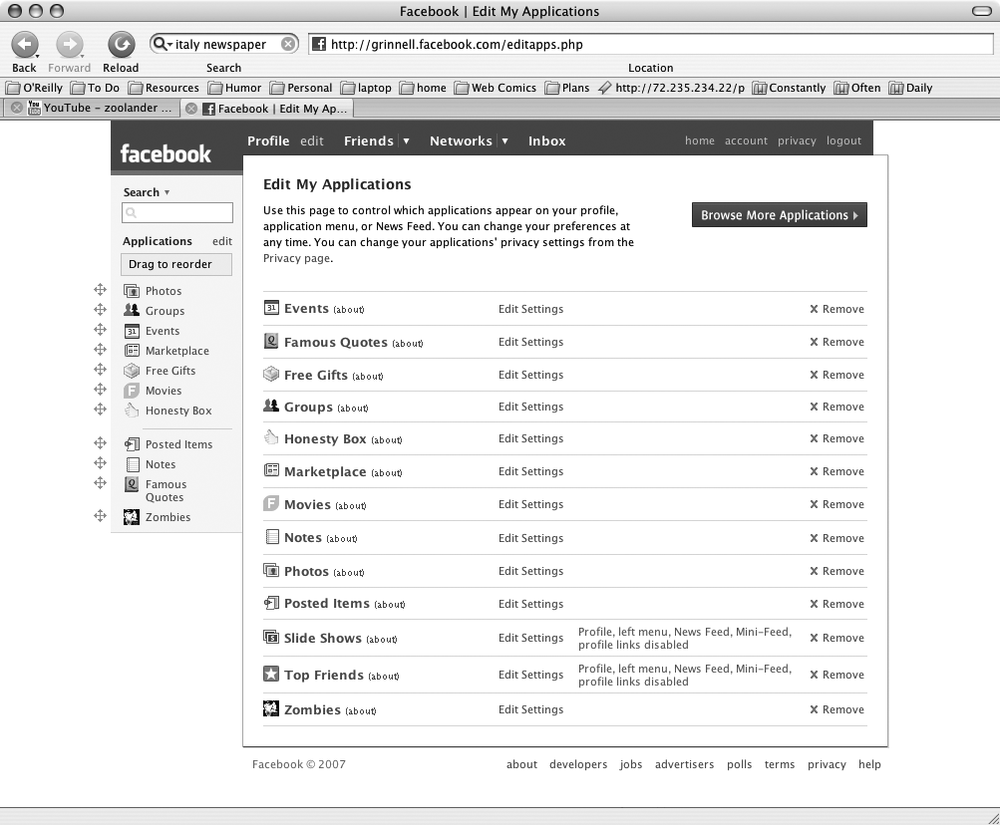

It started out as a pretty simple application—an upgraded version of the classic print photobooks some universities hand out to new students—and has grown into a much richer set of tools. Figure 3-10 shows a typical profile, and Figure 3-11 shows the interface for editing that profile. Users can present a lot of information without having to master a complex interface.

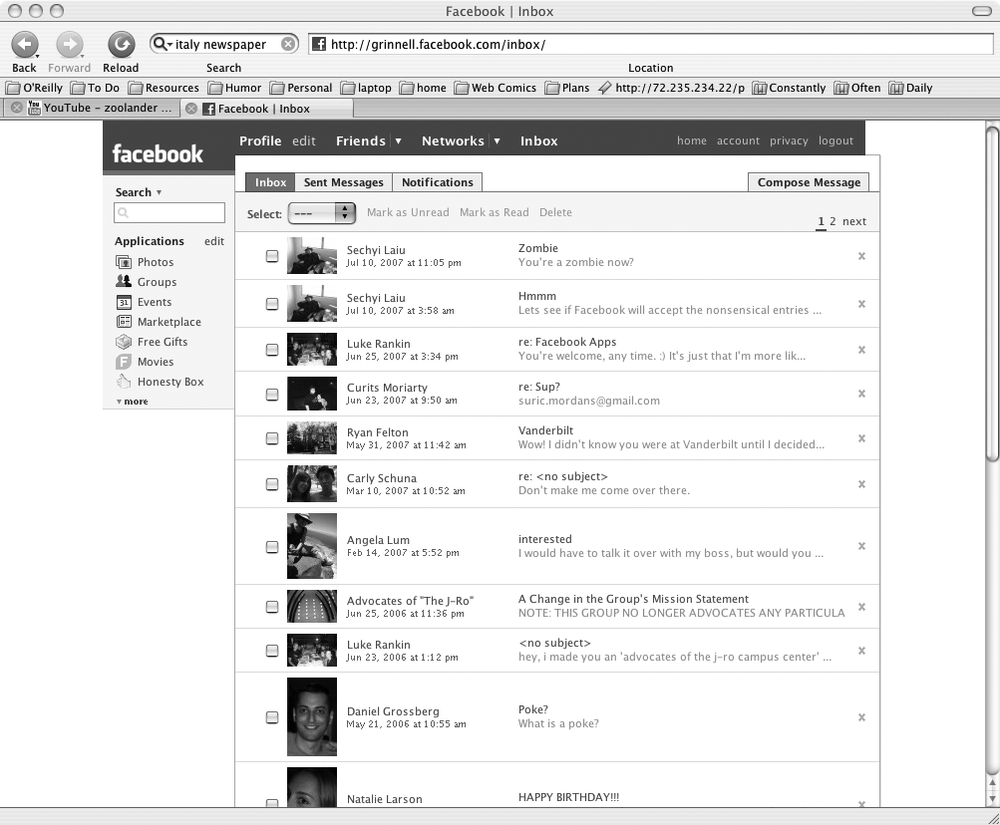

Facebook (like most social networks) also lets users communicate within their network, as shown in Figure 3-12.

Facebook’s Initial Growth

The hypergrowth of the Facebook user base continued as it developed, from 5 million online users in late October 2005 to more than 7.5 million in mid-April 2006.

Facebook enjoyed an exponential growth pattern much like the S-curve discussed in Chapter 1. It benefited from direct network usage effects: the more a user’s friends use Facebook, the more valuable it is to the user. Additionally, peer pressure and social influence fuel the “contagion” and word-of-mouth effect. If your friends are not using Facebook, why should you?

College students didn’t want to have to wait to see their friends show up and start using Facebook. So, speed of adoption is important to get to critical mass quickly.

Speed is also important in the race to reach a high enough market share to tip the market and lock out competitors. Facebook reached critical mass and tipped the market before other competitors entered the same space. The Korean social network site Cyworld seized a similar early-mover advantage in its national market. When first-movers in strong network-effects markets reach a dominant market share, they become hard to displace.

The usage patterns were impressive for the frequency as well as retention. Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg explained:[21]

On a normal day, about two-thirds of our total user base comes back to the site. A lot of sites measure monthly retention, and if you have 25%, you are doing really well. I don’t know any other site that measures their retention in daily retention. Facebook is a clearly different type of application.

Facebook had competition. MySpace had become the fifth most popular web site by number of page views. It had already grown as a music destination to include more than 350,000 bands and artists. Its growth rate was phenomenal as well; in October 2004, it had 3.4 million users, and one year later it had 24.3 million unique visitors—an increase of 600%. On July 18, 2005, the multinational media conglomerate News Corporation announced that it would acquire MySpace’s parent company Intermix Media for about $580 million in cash. As of August 2006, MySpace had broken through the 100 million account mark.

Although MySpace and Facebook are targeted toward social rather than professional networks, Facebook focuses on relational clusters and existing groups and circles of friends; MySpace is targeted at helping users find new friends—discovering social affinity groups related to music, bands, and artists. Facebook helps college students keep up with high-school buddies in other colleges, as well as peers from sports, music, extracurricular, and volunteer activities. MySpace supports much more customization of profiles than Facebook, which has stuck with a simpler look.

This is consistent with Zuckerberg’s creation of Facebook as a directory utility for people to keep tabs on the people in their lives and as a way to express themselves. One-third of Facebook users list their cell phone numbers, and a large number check their Facebook pages a couple of times a day. Of course, college students are concerned about how their online Facebook profile and photos appear to others. They’re also interested in identifying others on campus who have similar interests and in looking for potential dates.

By January 2006, Facebook had become so vital to the university lifestyle that eMarketer reported that incoming students were creating their Facebook profiles long before they even set foot on campus. By contrast, MySpace has a lower frequency of usage, and its users are doing different things on it—uploading music and playlists, and exploring new music and artists. College students might categorize MySpace with sites such as Last.fm, a popular site for finding new music.

Because the utilities and motivations for college students who join Facebook are different than for those who join MySpace, it’s not yet clear whether the two can coexist in equilibrium or will spark a competitive race—in the college market and overseas.

Viral Growth at Facebook

Mark Zuckerberg recalled that:

At Harvard, a few of my friends saw me developing Facebook and they sent it out to a couple of their friends and within two weeks, two-thirds of Harvard was using it. Then, we started getting emails from people at other schools asking, “How do we get Facebook? Could you license us the code so we could run a version of Facebook for our school?” But when I started it, there was no concept of having Facebook across schools.

In early March 2004, Facebook launched at Yale, Columbia, and Stanford:

We started with the schools which we thought the people at Harvard were most likely to have a lot of friends. We decided that those were Yale, Columbia, and Stanford. It was not really scientific; it was just intuition and probably wrong.

At Stanford, half or two-thirds of the school joined Facebook in the first week or two. At Yale, there was a similar story. Columbia’s community, on the other hand, was a little more penetrated by an existing application and Facebook didn’t pick up right away. A little later, when we launched at Dartmouth, half the school signed up in one night.

By June 2004, Facebook was serving 30 colleges and had about 150,000 registered users. Zuckerberg and his two roommates, Dustin Moskovitz and Chris Hughes, spent the rest of the 2004 school year trying to respond to the demand from colleges across the nation:

Early on, we weren’t intending this to be a company. We had no cash to run it. We actually operated it for the first three months for $85 a month—the cost of renting one server.

They were able to build their system with minimal customer acquisition costs. The popularity of Facebook made it something users signed into automatically:

We have natural growth built into our system in that over 3 million people leave high school and enroll in college every year. Last year, we had between 700,000 to 800,000 seniors graduate and are now alums on the site. About 45% of that group still returns to Facebook each day.

In September 2005, when Facebook opened its platform to high-school students, college students were asked to send invites to their high-school friends, who could then invite others:

The high school network reached a million users way faster than the college network did. The college network took almost 11 months to reach a million, and the high school took only six or seven months.

In 2004, Facebook was a free service and accessible to anyone with an “.edu” email account, limiting its use mostly to college students. Members of the network were encouraged to create a personal profile, including contact information, interests, and current course schedule.

It’s essentially an online directory for students where they can go and look up other people and find relevant information about them...I guess it’s mostly a utility for people to figure out just what’s going on in their friends’ lives, people they care about... Friendster, MySpace, and Facebook are all different things, but you can apply the [term] social networking to them because they have this model of having friends sending invitations [to friends].

Unlike MySpace or Friendster, Facebook made its members’ schools their primary networks and offered only limited access beyond that, making it a network of peers, rather than a random assortment of people. In the past few years, Facebook has opened itself to anyone who wants to join.

Facebook was fairly open by default: everyone at a member’s school could see his profile, but members could control their settings so that only their friends could view their profiles on the web site.

Viral Applications

In May 2007, Facebook launched a set of application programming interfaces and services that allow outside developers to add their own ideas to the Facebook user experience. Marc Andreessen, a founder of Netscape, posted a detailed and enthusiastic analysis of the Facebook applications platform:[22]

The Facebook Platform is a dramatic leap forward for the Internet industry.... Facebook is providing a highly viral distribution engine for applications that plug into its platform.

As a user, you get notified when your friends start using an application: you can then start using that same application with one click. At which point, all of your friends become aware that you have started using that application, and the cycle continues. The result is that a successful application on Facebook can grow to a million users or more within a couple of weeks of creation.

Finally, Facebook is promising economic freedom—third-party applications can run ads and sell goods and services to their hearts’ content....

Facebook is providing the ease and user attraction of MySpace-style embedding, coupled with the kind of integration you see with Firefox extensions, plus the added rocket fuel of automated viral distribution to a huge number of potential users, and the prospect of keeping 100% of any revenue your application can generate.

Facebook’s API offers its users a wide choice of new services, as shown in Figure 3-13. Users don’t have to wait for Facebook to provide new functionality for them—anyone can develop applications, and good applications will get shared across user networks quickly.

Perhaps more startlingly, the Facebook API also gives developers a place to see their ideas zoom across a huge number of people. The amazing effectiveness of this viral distribution is best told in the words of the iLike blog, shortly after its launch as one of Facebook’s first third-party applications:[23]

In our first 20 hours of opening doors we had 50,000 users sign up, and it is only accelerating. (10,000 users joined in the first 12 hours. 10,000 more users in the next 3 hours. 30,000 more users in the next 5 hours)....

Facebook’s rapid user-base chewed up our 2 servers almost instantly...we doubled...we doubled it again. And again. And again. O crap—we ran out of servers....

Tomorrow we are picking up over 100 servers from different companies to have them installed just to handle the weekend’s traffic....

Today was a critical day in iLike’s history. The Facebook Platform enabled us to build a service that in a single day matched and beat the impressive traffic we built on iLike. com in over 6 months. iLike is now growing at more than twice the pace it was yesterday, and accelerating. Fasten your seatbelts everybody, here we come! :-)

Facebook’s API approach is somewhat different from that of, for example, Google Maps. Rather than support new functionality outside of Facebook, it adds new functionality inside users’ familiar Facebook environment. Working this way, Facebook can share its success with a much broader ecosystem of potential partners who can leverage the huge social network inside of Facebook. Facebook itself, rather than the broader Web, acts as the platform here.

Tip

During the writing of this book, Facebook changed its application-sharing tools to make the viral marketing feel less to users like a massive influx of spam. Developers still have many ways to promote their products among Facebook’s tightly networked users. For one perspective on how this changes the adoption rate and business model, visit http://500hats.typepad.com/500blogs/2007/07/marketing-faceb.html.

The Limits of Viral: Facebook Beacon

Beacon is Facebook’s targeted social advertising system. From the press announcement and launch on November 6, 2007, 44 high-traffic web sites—from eBay to Fandango to Travelocity—were enthusiastic supporters of a new way to socially distribute information and connect businesses with relevant users and their trusted network of friends on Facebook.

For example, the chief marketing officer at Travelocity used the following example:

Travel is naturally a social activity that travelers enjoy discussing with the people they know...Using Beacon, Travelocity users can now easily choose to spread the news of their latest vacation plans on Facebook as a complement to their activities on the Travelocity web site.

The Beacon announcement was taken as a major step toward justifying the $15 billion valuation by Microsoft’s investment and proof of a business model for “monetizing” the reported 50 million Facebook users.

It didn’t work out, though, because users objected, and loudly. How did a platform hyped as the “most important marketing breakthrough in the past 100 years” become a major controversy about privacy and, in the eyes of several observers, “a disaster” that could bring Facebook down? After all, Facebook’s News Feed feature, introduced in 2006, was arguably even a bigger “privacy trainwreck,” and yet it’s a feature that many users now enjoy and consider positive and useful.

The most succinct explanation I heard online came from Andy Carvin, National Public Radio’s senior product manager for online communities and former coordinator of the Digital Divide Network, an online community:

One of the reasons Facebook is popular is that it makes it so easy for users to follow their friends’ activities.... For people who want their lives to be an open book, it’s a great tool. It seems that Facebook took that idea one step too far by making users’ purchasing decisions equally transparent, then not making it an opt-in service.

In other words, Charlene Li, a prominent Forrester Internet analyst, could purchase a cocktail table at Overstock.com and discover that all her “friends” had received a message via news feeds about her purchase. Or some number of the 55,000 protesters who signed the petition from MoveOn.org to demand that Facebook change the Beacon system had their holiday gift purchases broadcast to all of their friends, including the intended recipients. Coca-Cola, one of the early advertisers, stated that it had chosen to withdraw its participation in Beacon, stating that it had had the impression that Beacon would be an explicit opt-in program.

Facebook’s CEO Mark Zuckerberg apologized publicly on December 5 and made Beacon an “opt-in” system rather than a default. But trust was further eroded by independent tests that seemed to indicate that Facebook was continuing to collect information on click and purchase activities for data mining, whether or not its users opted-in. Legal experts and advocacy groups continue to look closely at the advertising program, and complaints have been filed with the Federal Trade Commission.

But the larger question had been raised in too many minds and blogs: does social advertising and marketing mean the end of privacy?

The more you reveal about yourself online, including your daily habits, your friends, your shopping habits, etc.—the more that data can be used to create value for the social networking company and their partners.... A lack of privacy becomes a fundamental part of their business models.

Lessons Learned

The online social networking experience teaches three critical lessons:

The importance of social networks and network effects for building your business to scale

The value that users can generate by sharing even basic information with a larger group

The incredible acceleration provided by bringing this kind of task to the Web

While all of these clearly apply to the explicit social networking applications examined in this chapter, they also apply to other projects that may not be thought of as explicit social networks.

Climbing Social Networks

Social networks have always been a key part of sales and marketing. When you’re trying to sell a product, you want to find key influencers. The acceleration that social networks provide in a Web 2.0 market has two major effects in this regard:

Social networks (even informal clusters) can make or break a product by spreading positive news of its existence to other potential users or by recommending a competitor.

The potential of online social networks to help people meet others they want to meet can entice ever-growing numbers of people to join an existing network.

LinkedIn provides clear paths for its customers to invite other customers to join its system. Members who invite their friends receive clear and direct benefits, and joining the network costs nothing (except time) for the invitee. This makes it very easy for people to give or get a positive impression of LinkedIn, accelerating its growth tremendously. Facebook’s viral marketing benefited from similar effects, amplified by its appeal to contained groups of people. Figure 3-14 shows how growth curves may vary by the nature of the kinds of people who spearhead the use of the system and their social influence.

Warning

Some people have taken this message to mean that marketing will have the greatest effect if it’s targeted to key influencers. It’s a good idea as a general rule, but always remember that influencers are already used to being targeted and the pool of influencers is constantly changing. Achieving critical mass requires not only reaching influencers but also making it easy for everyone to feel welcome at the party.

Similarly, both LinkedIn and Facebook grew more and more rapidly as the value of their networks climbed. “Are my friends using it?” is a critical question for possible customers, and it’s vastly easier to convince them to join as the number of their friends involved increases.

Value Generation in Social Networks

The value of a social network lies in its members. Social network software and sites are tools for connecting and finding the members, but in a strong sense, the health of the business isn’t the software, it’s the customers (see Figure 3-15).

Social networks don’t have to be like Flickr or Wikipedia, where users spend lots of time creating material to share with others. Basic social network software focuses on capturing what users already have—acquaintances—and creating a forum that can be shared and expanded. Directories are still powerful tools, and enhancing those directories to support new kinds of contact between users draws in more people on the basis of the same relatively small amount of information.

Some social networks give their users considerably more freedom to add information. LinkedIn sticks to the basics; Facebook lets users add more information in a fairly structured environment; MySpace lets users do all kinds of things to present themselves. The kind of information users are likely to add to an explicitly social network application may be different from what they post to Flickr or Wikipedia, but it can still draw new customers, often even more motivated customers.

Acceleration

Social networking is a hallmark of Web 2.0. Users are willing to share a certain amount of themselves, and that sharing creates new opportunities. It’s a situation where users who like the site will probably want to invite their friends to join, creating an army of potential marketers and evangelists. It’s a situation where anyone looking for a targeted group of people may be interested in paying for access to all of those people who just showed up, making it possible to sustain growth.

Warning

As noted back in Chapter 2, looking at the virtuous and vicious cycles in Figure 2-5, the acceleration can also run backward. Keeping a vast number of users requires gaining their trust and providing them with what they’ve come to expect. The same networks that promote growth can destroy market share and build up competitors if they give users reasons to depart.

Social networking creates an optimal arena for positive network effects to appear, and it also offers opportunities that can be integrated into projects that aren’t necessarily “social networking” projects. Any time a site has registered users—or even identifiable users—there may be an opportunity to offer them a place to call their own and share it with others. Building a community of people who use the same product and who can interact with each other, for instance, is a lot more likely to generate user interest than sites where customers interact only with a company. It’s less controllable, of course!

Questions to Ask

Your business probably isn’t Facebook, LinkedIn, or even something that looks much like them. However, social networks are becoming a more and more common aspect of web sites of all kinds, giving participants opportunities to connect and share, and to invite others to do the same. With that in mind, consider your own projects in the light of the questions below.

Strategic Questions

Think about your own business, professional, and social networks. With whom do you keep in touch and how often? What is it about your linkages, know-who, and “social capital” that contributes to the effectiveness and value of your network in situations ranging from mentoring and career planning to summer internships for a friend of a friend of a former boss. What is your online persona?

Consider an upcoming product or service launch for your business. Based on the key elements of online social networks that were explored using Facebook and LinkedIn, what might you pay more attention to in your planning now? What might you do to help identify the 1–3% active uploaders in your current community and support them as customer evangelists? How could you put into place platforms and services that invite viral marketing as well as viral distribution?

How might you have reacted as an key advertiser on Facebook during the MoveOn protest? What are your individual and company principles regarding user privacy?

What are some immediate and practical ways you can imagine to raise the awareness of those in your business, organization, and ecosystem about the power of social networks and communities in triggering social influence and adoption?

As a project team member, are you ready to systematically map and analyze with your group members the social networks of customers and partners critical to your business?

Tactical Questions

How might your users relate to each other? (Or, how do they presently relate to each other?)

If you have an existing place for users to communicate, would you benefit from enriching it with profiles and contacts?

Do you provide mechanisms for your users to communicate among themselves?

Do you provide tools for users to invite others to join your site?

How much information are your users really willing to share about themselves?

What balance of openness and privacy is appropriate in your business’s context? What mechanisms do you have to maintain that balance?

What value might user information create for you in this context? Advertising value? User happiness value? A new business of people who want to contact your users?

Do you know how tightly knit your current users are? Are they tightly clustered, loosely clustered, or purely individuals who haven’t yet formed connections?

Have you identified key individuals in your user base who have developed the trust of others and can make things happen on your site?

Would your site benefit from a full-blown social networking component, with contact lists, degrees of separation, and more, or might simply adding a profile page for users provide more immediate benefits?

How does the current nature of your user base influence your potential for expansion? Are there specific subjects you should explore or projects you should undertake to maximize network effects building on who your current users know?

What are the ratios of different kinds of users on your site? How many are contributors, how many are readers, and how many are active in community-building or networking? How can you monetize some groups without alienating others?

[20] Michael Fitzgerald, “Internetworking: new social networking startups aim to mine digital connections to help people find jobs and close deals,” MIT Technology Review, April 2004, http://www.technologyreview.com/Infotech/13526/page1/?a=f.

[21] The quotes from Mark Zuckerberg are from the Stanford Business School case on Facebook (http://harvardbusinessonline.hbsp.harvard.edu/b01/en/common/item_detail.jhtml?id=E220). Quotations were taken from his interview with venture capitalist Jim Breyer at the Oct. 26, 2005 Stanford Technology Ventures Program or from an interview with Professor Willam Barnett, case author, April 2006.

[22] Marc Andreessen’s blog, June 12, 2007, http://blog.pmarca.com/2007/06/analyzing_the_f.html.