Chapter 1. Users Create Value

WEB 2.0 TAKES A FUNDAMENTALLY DIFFERENT VIEW of how businesses, customers, and partners interact, and in doing so, it opens up a range of new business models. Back in 1980, Alvin Toffler’s bestseller The Third Wave (Bantam) predicted a new type of “pro-sumer,” someone who is a mix of a DIY (do-it-yourself) producer and consumer in offline marketplaces. It was a great vision, but without the recent advances in web and digital technologies, most online broadband and mobile users could not make the quantum leap from being passive viewers and readers to becoming actively participating, socially engaged, and collaborative uploaders—personal contributors and creators of the Web.

Web 2.0 turbocharges network effects because online users are no longer limited by how many things they can find, see, or download off the Web, but rather by how many things they can do, interact, combine, remix, upload, change, and customize for themselves. This online DIY self-expression benefits businesses and other users, not just individual uploaders.

Flickr, a Web 2.0 photo-sharing site, illustrates the business and financial impact of uploaders and their remarkable collective user value. We’ll analyze Flickr’s multiple revenue streams and cost structures, making you familiar with how to evaluate the customer profitability and financial valuation pros and cons of moving to a Web 2.0 business model.

We’ll also contrast it with Netflix, an online video rental company founded during the dot-com era, which uses many of the same technologies but has a fundamentally different—and more difficult—business model.

Tip

Most chapters in this book will lead with theory and then go into detail. To get started, though, it makes sense to see what a Web 2.0 company looks like.

Flickr and Collective User Value

Flickr, shown in Figure 1-1, is a poster child for Web 2.0. It offers users a way to share photos easily, starting with the simple stream of photos shown in Figure 1-2.

Flickr users who accept the default mode of public photos don’t have to do anything more to share their pictures. They can upload them and add captions and comments (metadata) for their own convenience, and other people can see them immediately. If users want to see the latest photos their friends have posted, they can simply visit their Flickr pages. Those photos can also be better organized (Figure 1-3), and presented as slideshows (Figure 1-4).

This is just the beginning, of course. Flickr offers users a variety of ways to upload and manipulate their photos, several ways to organize them, a fun set of tools for connecting photos to maps, and options for printing photos in a variety of different formats. For a more detailed explanation of what Flickr offers, visit http://flickr.com/tour/.

Flickr’s friendly and easy-to-use web interface and its free photo-management and storage service are great examples of a Web 2.0 “freemium” business model—fine-tuned to leverage collective user value, positive network effects, and community sharing.

The term “freemium”[7] was first introduced on venture capitalist Fred Wilson’s blog, A VC (http://avc.blogs.com/). He described it this way:

Give your service away for free, possibly ad supported but maybe not, acquire a lot of customers very efficiently through word of mouth, referral networks, organic search marketing, etc., then offer premium priced value added services or an enhanced version of your service to your customer base.

Taking a typically Web 2.0 “collective user value” approach, Wilson asked for online suggestions about what to call this business model. Jarid Lukin, director of E-Commerce at Alacra, came up with the clear winner: Free + Premium = Freemium.

The November 2006 issue of Business 2.0 titled its first article on the “freemium” strategy “Why It Pays to Give Away the Store.”[8] Business 2.0 later posted it online with the headline “A Business Model VCs Love,” as this strategy had already been used profitably by companies as diverse as Adobe with its PDF Reader and Macromedia with its Shockwave Player, as well as Skype, Flickr, and MySpace.

In Flickr’s case, practically zero marketing costs and low-cost online distribution and capital investment allow revenue from multiple streams, including value-added premium services, to very quickly cover the cost of free basic services and customer acquisition. Additionally, in Chapter 2, we will see that ad-based revenues and n-sided markets capitalize on the positive network effects of Flickr’s collective user and community-generated value.

Collective User Value and Positive Network Effects

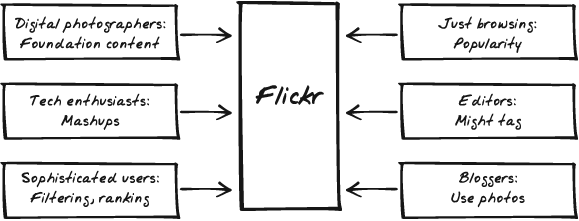

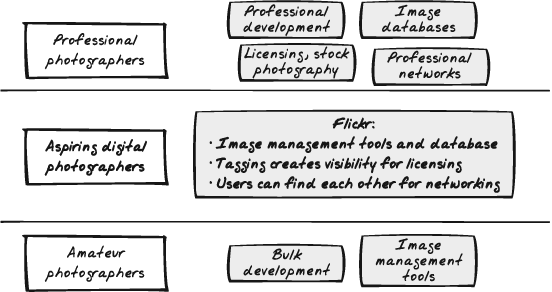

The more users, traffic, and aggregated feedback that Flickr has, the better the system performs for everyone, thanks to direct positive network effects. Flickr’s system improves continuously, multiplying positive feedback, on the basis of active and passive clicks of multiple users navigating the site, sharing photos, creating user-defined tags and clusters of tags, collaboratively filtering and ranking, holding group events, syndicating photos to other sites, and blogging. Different kinds of users tend to engage different parts of the system, as shown in Figure 1-5.

Users can actively upload photos and contribute and collaborate on content. Even if they aren’t that involved, they still passively provide clickstream feedback that can be indexed and quantified for advertisers, marketers, and complementary service and product providers. Every time someone tags a photo with keywords or metadata—e.g., Turkey, bubbles, cute—Flickr’s knowledge pool increases. As the community provides keywords and conducts searches and writes captions and comments, the data becomes easier for users to find, and the database of searchable photos becomes more valuable.

Trusted Context for Interaction and Community

By default, Flickr users share their uploaded photos publicly. Many Web 2.0 companies make public sharing the “no-click” or default option, the understood norm. Those who want to keep their files private can still choose to do so.

When users find it easy to connect and open up to others, they become increasingly comfortable uploading and sharing self-generated content; frequent interaction builds community, trust, and self-policing norms. By 2006, Flickr’s platform allowed more than 2 million registered users to become active uploaders of more than 100 million photos, 80% of which were publicly shared through the Flickr photo database. Flickr’s online platform was quite timely in compounding the positive network effects of broadband penetration: an explosion of digital camera and cameraphone usage, blogging, social networking, and RSS (Really Simple Syndication). (Online syndication is explained further in Chapter 4.)

Why are publicly shared “open content” photos an important aspect of Flickr? Making all knowledge and images explicitly public helps the community learn to photograph, select images, build, design, or code more efficiently, thus creating better output. Not only is new knowledge produced every time users collaborate, but individual productivity increases whenever anyone joins the community and adds her knowledge and skills.

Reaching, Tagging, and Monetizing the Long Tail

Users self-select along multiple personal dimensions, categories of preference, utility, social interest, and experience. Pay-per-click (PPC), click-to-call, web analytics, and clickstreams make it easy to reach these individualized online clusters of users directly with targeted or complementary offers, or to subsidize services to these groups by interested sponsors or advertisers. As shown in Figure 1-6, Flickr’s founders came up with innovative ways to reach the long tail of the online photography world: new online photo users not accustomed to photo sharing beyond their friends and family.

Millions of users became actively engaged in contributing and defining interesting categories, activities, events, and groups loosely tied to the photo-sharing community and database.

Why take the time to upload photos to Flickr and tag them? Because it serves your self-interest in three ways. First, you can store and sort your own photos, solving an immediate problem. Second, you tap into an amazingly creative photo database and knowledge pool, so you can learn about digital photography. Third, it’s a great way for talented photographers to get discovered.

To Steve Rubel, author of the Micro Persuasion blog (http://www.micropersuasion.com/), these heavily tagged databases guided by human interests are a boon for marketers, who can get real-time views of what users are really passionate about. “Where the eyeballs go, there’s an opportunity to experiment with marketing.”

Six Ways Flickr Created User Value Through Interaction

The core business message of Flickr is neatly summarized in a slide from its 2004 launch at the O’Reilly Emerging Technology Conference:

Don’t build applications. Build contexts for interaction.

In March 2005, Flickr was a Fast Company 50 winner for “Reinventing a category whose flashbulb burnt out.” In the magazine interview, [9] founders Catarina Fake and Stewart Butterfield summed up the basis of their success—their users:

We have quickly created the largest and best-organized online photo library in existence with 1.8 million images, of which 81% are public, and 85% have some human-added metadata. What this means is you can find photographs of anything that strikes your fancy. Flickr is infinitely shareable and easily searchable.

Open Up Digital Content to Global User Interaction

Flickr photo sharing introduces individually uploaded digital content—photos and images—to a global online community. When users upload photos to Flickr, they are usually sharing them not only with friends and family but with communities of Flickr users and the whole Internet as well. Because Flickr’s default photo visibility setting is public rather than private, after its first year, more than 80% of all photos were public.

Opening up user-generated and uploaded digital content is the next stage of the open-systems movement started by Linux and followed by Google’s open application programming interfaces, or APIs. Open systems and open APIs have a significant impact on hardware and software developers, products, and services. Unrestricted uploaded digital content has a much broader impact on the mass-media market, the millions of broadband and mobile users, and consumers of all media.

This type of shared digital content sets off a positive direct network effect on the breadth and variety of the image database and sparks viral marketing. Each new member adds his uploaded digital photos to the completely user-generated collective Flickr photo database rather than maintaining (or hoarding) a proprietary cache of private photos. Of course, Flickr has given users the choice of sharing their photos openly while maintaining control over licensing and ownership. Almost 130 million photos have been posted by some 3 million registered users. Open photo sharing enables Flickr to be a completely user-generated image database. Clearly, this is the same route that YouTube took a few years later but with a slightly different target: a user-generated video database and open community for online public sharing.

Create Better Search Through User-Generated Information

Ever borrowed a copy of a friend’s dog-eared, underlined book and found the notes to be as interesting as the original content itself? Tags, footnotes, and annotations are forms of metadata—an interpretation, highlighting, or framing of the original data.

In Flickr, all users and observers are encouraged to become actively engaged by annotating photos—both their own and others'—with tags and notes. These actions contribute to the categorization of photo images into tag clusters and provide aggregated feedback, making it possible for better human-guided “fuzzy” searches of images. For example, Flickr creates tag clusters using dynamic analysis of the groups of tag words used together, such as “Turkey” with Istanbul compared to “turkey” with Thanksgiving. Figure 1-7 shows the highest-level view of these tags, called a tag cloud. The most popular tags are listed alphabetically; their sizes are used to differentiate popularity.

Flickr has been so successful at involving users that more than 85% of the photos on its service have human-added metadata. As with the Google PageRank and AdWords algorithms, the quality of search and image categorization results improve as more people view, comment on, mark as a favorite, or tag photos. The system as a whole becomes more effective and valuable as a result of this direct network impact from the increased number of users. Additionally, individually generated annotations and tags provide a richer, more complex window into the metadata—a view that can be surprisingly multidimensional. For example, photos of kittens playing are more often tagged with an emotional descriptor like “cute” or “cuddly” than a more objective classification like “cats” or “felines.”

As Stewart Butterfield said:[10]

The job of tags isn’t to organize all the world’s information into tidy categories. It’s to add value to the giant piles of data that are already out there.

User-generated tagging systems are often known as folksonomies,[11] a term coined by information architect Thomas Vander Wal. As he described it:

One of the things that’s nice to see is that people are actually spending time tagging and doing it in a social environment, and following the power curve and the net effect. The more people getting involved with it, the greater the value....

Discover and Explore Through Online Groups

Flickr was a leader in creating photo image metadata to make it easier to filter and search through its open photo database and also in encouraging millions of photographers to explore, and discover, through groups. Some of the collective value comes from Flickr leveraging the aggregated number of photos and tags and then dynamically analyzing usage and user behavior in its system to provide improved services, such as “search” or clusters, for users who contribute their photos to the Flickr database. Also, Flickr users gather around particular interests, many of them related to travel, and participate in groups and group events.

Catalyze and Amplify Group Social Network Effects

Flickr also has its own dynamic algorithmic means for rating, sorting, and finding photographs, which it calls interestingness. Rather than just running a popularity contest, using PageRanking (considering the number of links), basing traffic on Google “juice” (recent traffic or interaction), or requiring users to vote, Flickr has an undisclosed formula. Its “secret sauce” contains factors as diverse as how many times a photo has been viewed, commented on, marked as a favorite, and tagged. The system also gives weight to who does each action and when.

The simple aggregation of how many times a photo has been “favorited” would be a simple popularity metric. Giving more weight to certain users than to others moves the algorithm into a whole new domain of social influence and capitalizes on key trendsetters, trendspotters, or community catalysts.

DIY Self-Service Syndication

Flickr was a first-mover in providing an integrated set of self-service tools, Web 2.0 platform services, and APIs for the exploding use of digital cameras and camera phones, high-speed broadband, and low-cost infrastructure (for digital photo storage and bandwidth). Flickr took advantage of these services to make it easy to integrate photos and visual images with blogs, social networking, and syndication via RSS. In 2006, more than 1 billion photos were taken from the more than 300 million camera phones in use. An estimated 10% of the photos on Flickr were directly uploaded from mobile devices.

Syndication was an important element of Flickr’s success. It was a completely new idea to allow users to subscribe to photos as RSS feeds. By offering a basic free account and comprehensive support for the major blogging platforms, Flickr quickly became the preferred choice for a growing army of active bloggers, who became the primary subscribers to the paid Pro Account services.

Encourage Others to Become Part of Your Digital Ecosystem

Thanks to Flickr’s open API, third-party individual developers, as well as companies, built image uploaders for a range of operating systems, making it easy to connect to Flickr from many different devices and applications. For example, ShoZu built tools for cameraphone users, and zipPhoto did the same for Microsoft’s Smartphone.

Flickr became the center of a digital photo ecosystem of partners, third-party applications, mashup developers, and bloggers. This not only saved development costs and fostered innovation, it also built trust and long-term relationships with sophisticated and more tech-savvy users and developers.

Why Sharing Can Be Profitable

How does Flickr capture value, and how can it be measured?

Business managers inside a company can analyze their internal business model to characterize and visually diagram a company’s profit engine.

Industry analysts or strategists evaluating a company from the outside can compare it with competitors and industry players to assess its stock market capitalization value, acquisition value, or total enterprise value. They can use industry structural analysis and consumer-focused financial valuation.

We’ll use the first of these two perspectives—the business model as a profit engine—which is appropriate for managers and entrepreneurs who are making key business decisions and trade-offs to turn their ideas into profits and a sustainable business. We start by asking whether the business has single, multiple, or interdependent revenue streams. Then, we look at each of the sources of revenue, the revenue streams, their growth potential, and the cash flow timing for new customers.

To kick-start or fine-tune a business profit engine, let’s start with identifying the inner workings of revenue sources, key cost drivers, investment size, and key success factors. Typically, companies have four choices of how to use revenue streams:

- Single stream

The company relies on one predominant revenue stream stemming from one product or service.

- Multiple streams

The company collects multiple revenue streams from different products or services.

- Interdependent streams

The company sells one set of products to stimulate revenue and growth from another set, for example, razors and blades.

- Loss leader

Not every revenue stream of multiple streams are independently profitable, but those that lose money drive traffic to spur other purchases and together they achieve profitability.

Rather than relying on a single stream, Flickr chose a multiple revenue stream model, where the company:

Collects subscription fees from monthly premium account subscribers who receive unlimited storage, full-resolution images, and no advertising

Charges advertising transaction fees to advertisers for contextual advertising

Receives sponsorship and revenue-sharing fees from partnerships with large retail chains and complementary photo service companies

Flickr’s revenue model uses the first three of the six kinds of revenue models. These models include:

- Subscription/membership revenue model

Provides a fixed amount of revenue at regular intervals based on the number of subscribers and is usually paid in advance of receiving the product or service, e.g., health club memberships or magazine subscriptions. Flickr Pro Accounts charge $24.95 per year for unlimited storage, full-resolution images, and no advertising.

- Advertising-based revenue model

Allows users to benefit from free products or services. The advertiser pays for clicks, e.g., the Google search engine, or for eyeballs, such as with network television advertising. Flickr uses contextual advertising, a revenue model that efficiently monetizes clicks into dollars for its large and fast-growing installed base of users and online usage. An additional advantage is the ability to increase advertising spending per customer depending on the return on investment (ROI) of an advertising and marketing campaign.

- Transaction fee revenue model

Has the customer pay the company that facilitates the transaction a fixed fee or a percentage of the total value of the transaction. eBay, for example, charges the seller an 8% transaction fee. Target, the department store, shares a sliver of its Flickr clickstream photo development revenue with Flickr.

- Volume or unit-based revenue model

Has the customer or buyer pay a fixed price per unit to the seller and receives a product or service in return. This revenue model is common in offline, brick-and-mortar businesses and services.

- Licensing and syndication revenue model

Has the customer pay a one-time licensing or syndication fee to use or resell the product. Often, a buyer will pay a separate licensing or royalty fee in a business-to-business transaction; for example, an enterprise pays a software company for a certain number of site licenses, or a pharmaceutical firm licenses a drug from a biotech startup. iStockphoto, an online stock photo web site acquired by Getty Images (the largest stock photography company) charges a small licensing fee for downloading images from its site. (Several bloggers have pointed out that it would not be difficult for Flickr to implement a licensing or syndication revenue fee that would allow Flickr users who post photos to receive licensing royalties from interested photo buyers with some percentage of that revenue stream going to Flickr.)

- Sponsorship/co-marketing revenue model, also called revenue-sharing model

Has sponsors pay for direct marketing and branding access to customers.

Instead of following the licensing revenue models developed by stock photo and advertising agencies for use in the professional photography industry, or the volume/unit-based revenue models used by the Shutterfly and Ofoto digital photo printing companies, Flickr’s revenue model exploits the much larger but virtually untapped markets of amateur digital photographers and broadband, mobile, and laptop multidevice users.

The advent of low-cost, high-quality, and high-megapixel digital cameras and camera phones dramatically shifted the customer usage patterns of picture taking. Users can now take many more digital photos, delete the ones they don’t like immediately, and still have lots of photos to share, keep, and organize. Unlike 35 mm film processing where customers pay a price for developing each roll they shoot—and then a per picture fee for printing onto glossy 4 × 6 photo paper—most amateur digital photographers need a free or low-cost, easy-to-use way to share, store, organize, manage, and access their rapidly growing personal inventories of digital photos online.

Flickr essentially gives away the services that amateur digital photographers need and want most: photo sharing; online storage; and indexing, tagging, and photo inventory. Flickr’s revenue model is focused on the three revenue models—subscription, advertising, and transaction/revenue sharing—that are most attractive to the noncommercial amateur photography community. This revenue model takes into account the dramatically shifting usage patterns in digital sharing, multidevice, storage, and reuse.

Flickr’s main photo-sharing community could be seen as a loss leader within interdependent streams of revenue because free services are subsidized by other more profitable revenue streams. But loss leaders are typically temporary pricing cuts intended to bring in new customers. In contrast, freemiums and n-sided strategies are actually an innovative new online business model, based on cross-network effects.

Not every revenue stream needs to be independently profitable, as long as traffic is driven to spur other purchases and achieve overall profitability and growth. In Flickr’s case, maintaining a free, noncommercial (but highly trusted), interactive, and open photo database is key to the vibrancy of the user-generated activities. This free database also drives the growth of community and the partnership and third-party developer ecosystem, and it imposes relatively little cost beyond what would be needed to serve its customers’ direct needs.

Flickr’s Cost Drivers

To get at the inner workings of cost structures, the key questions to answer are the following:

From the outset, Flickr found innovative ways to avoid the four major cost drivers of the retail photo printing business and online stock photo companies. Flickr’s collective user value strategies convert its significant cost savings into a competitive advantage and positive network-effects generator.

The first key cost driver is inventory. A typical stock photo company—online or offline—must acquire a high-quality stock photo inventory and develop a cataloging and management capability to make a large and broad inventory accessible and easily distributable to viewers, potential buyers, and image licensors.

The second key cost driver is payroll. A retail photo printing business has direct payroll costs for employees who are involved in the photo development and printing process, as well as indirect or support payroll for employees who are at the checkout counter or involved with the maintenance of the store equipment or supplies.

The third key cost driver is information technology systems and developers. Most web stores spend a large proportion of their costs on IT design, development, maintenance, and payment systems compared with offline retail stores that instead have space/rental costs (driven by real estate in square footage) for office or retail space.

The fourth key cost driver is marketing, advertising, and customer relationship management (CRM). Marketing and advertising costs are higher pre-sales, and customer relationship management costs are often higher post-sales. Because the barriers to entry are low in the retail photo printing business and online stock photo business, marketing, advertising, and customer relationship management are critical for differentiation, as well as for traffic and new customer acquisition.

Table 1-1 lists the seven collective user strategies on the left, and the primary cost centers for different cost structures along the top. The boxes marked “Major” indicate the areas where Flickr enjoys major cost reductions thanks to its use of collective user strategies. The boxes marked “Measurable” indicate the areas where Flickr enjoys measurable cost savings compared to more traditional approaches that do not benefit from user contributions and interactions.

Tip

One key omission in Table 1-1 is the cost of goods sold, or COGS, which isn’t a factor for Flickr and is by definition a major savings.

SAVINGS TO: | DIRECT PAYROLL | SUPPORT PAYROLL | INVENTORY | IT SYSTEM | MARKETING/AD/CRM |

Open photo sharing | Major | Major | Major | ||

Self-service | Major | Major | |||

DIY tools | Measurable | Major | Major | ||

Tagging | Major | Major | Measurable | Major | |

Collaborative filtering | Measurable | Measurable | Major | ||

Group discovery | Measurable | Measurable | Major | ||

Syndication and blogging | Measurable | Major | Major |

Flickr faced one enormous technical problem: the challenge of building a scalable and searchable image database without spending tremendous sums of money. Flickr’s tag-based approach helped it on the search side and gave the database project a different set of priorities from those of many earlier image storage projects. Building the application using that approach gave Flickr the ability to capitalize on user contributions while solving a technical issue. Flickr drastically reduced the cost and risk of developing and implementing a superior (and well-connected) photo management database by creating partnerships with its users and third-party developers, rather than building all the capabilities in-house as proprietary code. Collective user value was a major competitive and strategic advantage in transforming the cost structure of Flickr and similar Web 2.0 technology companies.

Calculating Company Value

Yahoo! bought Flickr for an estimated $30 to $40 million in March 2005. Although Flickr’s founders reported (http://blog.flickr.com/en/2005/03/20/yahoo-actually-does-acquire-flickr/) that they would “no longer have to draw straws to see who gets paid,” the reality was much brighter. Flickr could bring its hypergrowth strategies to Yahoo!, and Yahoo! could provide additional publicity and infrastructure to the growing photo service.

Flickr’s value, though, is a tough question. Value is clearly not just the infrastructure of the company, or even the brand. For a company growing like this, the value depends on the customers. In the past, this statement was agreed to in principle but difficult to quantify. Financial valuations of companies were calculated on earnings multiples and on forecasts of market and unit production growth. However, new forms of “customer-based” company valuation formulas and models were developed to analyze the many subscriber businesses and services such as cable and cell phone services, in which revenues are directly tied to customer fees, not unit prices.

Tracking individual customer behavior and metrics rather than unit sales volume as the actual “basis” for revenue growth and business models leads to terminology that is relatively unfamiliar to most business managers and M.B.A.s. Analysts use the terms “individual customer profitability,” “average lifetime customer value,” and “loyalty” to emphasize that quantitative metrics in many customer-focused industries—including the gaming and casino industries—can be aggregated to arrive at fine-grained financial enterprise valuations. These metrics can also be analyzed strategically to dramatically improve profitability at the individual customer level. Harrah’s Casino is an exemplary case: quantitative individual customer analysis of its “VIPs and high-rollers” changed the company’s service and business model dramatically.

Using the basic total enterprise value formula with a discounted cash flow model for lifetime values is particularly important when the average lifetime of an average subscriber can range from one month to five years. It is also important when there is a high risk that users in the installed base will “churn” or “switch” between different plans or companies, but fees are received on a regular schedule, such as monthly.

In contrast, for online businesses such as Flickr, Yahoo!, and Google, ad-based revenues make up a large part of the “average lifetime value of a customer.” With web analytics and digital tracking of PPC and page impressions, most online businesses can calculate the “average revenue per search query,” and from that, the “average revenue per customer” per day, month, or year. For example, at the 2006 Web 2.0 Summit, Mary Meeker, top Internet analyst at Morgan Stanley, mentioned that Google’s average revenue expectation was $13 per customer:

If we look at advertising revenue per user [per year] for some of the top sites on the Internet, Google gets about $13; YouTube gets less than $1. We think that helps us to get a sense of what the monetization upside is for some of the other sites with Google as a benchmark at that level (http://www.oreillynet.com/lpt/a/6848).

In Flickr’s case, in which the company was acquired largely for its loyal and active customer base of 2 million users as well as its Web 2.0 platform, a $40 million acquisition could mean that these 2 million users have a combined average ad-revenue, premium, and partner revenue stream of $20 per user over the next 3 to 5 years. Although a “multiple” like $20 per user might seem too simple, several of the analyst commentaries on Facebook’s recent valuation used a similar user-based approach. After all, advertising and market access to 2 million users (in Flickr’s case) or 50 million users (in Facebook’s case) is extremely valuable, and thanks to pay-per-click, it is immediately monetizable as revenue from advertisers and sponsors.

Some informal discussions with Yahoo! executives indicate that they are also weighing the value of the attractive segment of the 1% to 10% most active contributors to the Flickr community. This would make a lot of sense—the lifetime value of an active and influential user should be higher, both in tangible collective user value and in contributions back into the user community. Such highly active users also trigger an increase in the number of customers through the improved value and quality of the overall system, the higher level of community engagement, and viral and referral marketing.

For example, in his blog titled “Creators, Synthesizers, and Consumers,” (http://www.elatable.com/blog/?p=5), Bradley Horowitz, Yahoo! vice president of product strategy, mentions the following:

In Yahoo! Groups, 1% of the user population starts the group, 10% participate actively and may actually author content, 100% of the user population benefits from the activities of the above groups.

Even in Wikipedia, half of all edits are made by just 2.5% of the logged in users... social software sites don’t require 100% active participation to generate great value.

For customer-facing businesses, this approach to valuation emphasizes the importance of customers and growth in the value of the company. (It could also include the ongoing nonfinancial contributions of customers, although that may be a challenge to quantify.)

In Flickr’s case, this may be the only relatively simple way to gauge the company’s value.

Looking Back: Netflix’s Different Challenges

Netflix is a proud survivor of the dot-com boom and bust, and in the years since then, it has added more and more community features to its site. Like Flickr, Netflix:

Appeared at a time when the nature of a communications medium was changing

Distributes a huge quantity of visual information to its users

Depends on an ever-evolving web interface for interacting with its customers

Grew rapidly thanks to users reporting their experiences to their friends (quickly developing market share that couldn’t easily be challenged)

Unlike Flickr, however, Netflix began in an era when it was still difficult for people to create shareable content, and delivering its services meant physically moving a DVD from its warehouse to the customer and back. The physical nature of the DVD and the cost of purchasing DVD content gave Netflix a set of problems whose solutions point the way toward many of the advantages of a pure-web approach.

The Costs of Growth

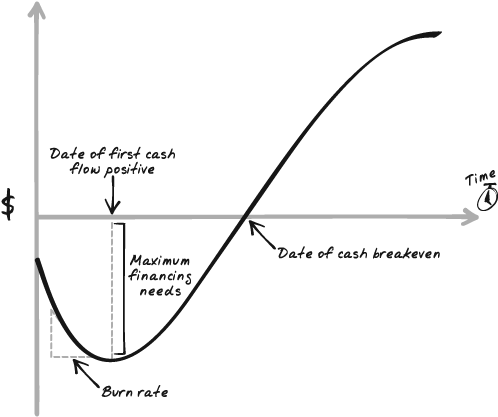

“Burn rate” was a popular term during the dot-com boom. Because economies of scale were a critical advantage of the Web, the general idea was to grow a company’s market share rapidly. The cash flow curve that looks like a J-curve, shown in Figure 1-8, demonstrates what would happen as startup companies tried to buy new customers and market share with their investors’ dollars.

The first part of the slope reflects the period when a company is spending more to build market share than it’s making in revenue. The burn rate is initially steep, as the company spends money on marketing, hiring, and expanding infrastructure, but customers haven’t yet rewarded that investment. As more customers come in, revenue should start to exceed expenditures, and the curve should fall less sharply, flatten, and then start climbing. When the curve climbs, cash flow is positive, and that will (hopefully) lead to eventual profit.

Netflix faced a very basic problem: acquiring new customers was tremendously expensive. Building the web infrastructure was expensive, of course, but the bigger, more difficult problem was the cost of what it was sending to customers: DVDs. DVDs were new technology in 1997 (and even in 2000), and each DVD cost a lot. Netflix was serving an audience of early adopters, successfully creating an initial frenzy by offering expensive movies at low cost—even free—for the initial offer. It’s hard for a lending library to stay afloat when its customers want to be assured that they can always have the latest and greatest, even when there are thousands of customers.

The price of DVDs had a drastic effect on the costs of customer acquisition and the time it took to recoup those costs. By following a single customer (and ignoring marketing costs), we can see how how those costs add up. (For details, see the upcoming sidebar "The Profitability and Expected Value of a Netflix Customer.”)

Because of the very high cost of the four (mostly new-release) DVDs sent out to each new subscriber, it takes four to six months of each subscriber’s monthly fees to recoup the initial cash outflow. Shipping costs are relatively insignificant compared with the cost of acquiring the DVDs.

In theory, Netflix was worth a lot of money—it had a lot of customers happily paying for services. Using the total enterprise value formula described earlier in the "Calculating Company Value" section, Netflix was valued at about $120 million in 1999.

However, the relatively simple analysis of that Netflix business model yielded a cash flow curve that proved Netflix was unlikely to survive long enough to even realize this total enterprise value.

Escaping the Trap

Escaping the high costs of customer acquisition and maintenance required several different steps. The overall cost of DVDs—around $20 each—was a looming problem, and not just during the customer acquisition phase. Netflix was an independent company, not attached to any of the studios, so there wasn’t any direct reason for studios to be helpful. The studios enjoyed the money they made from selling DVDs to Netflix, a major customer, but their business interests didn’t match Netflix’s interests.

According to Rentrak News,[12] a home-media retailing online newsletter, the movie studios were getting $65 for outright purchase of their VHS cassettes in the “heyday of the high-priced rental cassette,” mainly from smaller rental chains, which preferred to be able to sell previously viewed titles within 30 days for new releases. The large chains like Blockbuster had an estimated 70% of their new titles on 60/40 revenue-sharing with the studios but had contractually strict selloff restrictions to avoid cannibalizing new-release direct sales.

Netflix now brings in about 60% of its new releases through revenue-sharing, according to Chief Content Officer Ted Sarandos: “Revenue-sharing is a way to maximize customer satisfaction in a margin-neutral way....”[13]

Surprisingly enough, in December of 2000, Netflix was the first Internet DVD dealer to have a revenue-sharing agreement with the major motion picture distributors Columbia TriStar and Warner Home Video. At that time, Netflix stocked 9,000 DVD titles and had a subscriber base of 250,000 members, who paid $19.95 a month for unlimited movie rentals. Reed Hastings, cofounder and then-CEO of Netflix, said:[14]

We are extremely pleased that these major studios recognize Netflix as an important distribution channel for their content. With these revenue-sharing deals, we can continue to deliver on our promise to provide the best movie experience possible—giving our customers the titles they want, when they want them, and allowing them to enjoy the movies for as long as they like. The agreements also help us keep pace with our extraordinary growth, without compromising our quality of service.

Warner Home Video President Warren Lieberfarb[15] also pointed out the importance of the DVD as the format standard of the future and the realization that DVD rentals could open up a market much larger than the one for new releases:

DVD is the entertainment format of the future, and Netflix is our fastest growing customer for DVD rentals. We look forward to working with Netflix to expose the DVD viewing audience to Warner’s vast library of films.

Steve Lyons,[16] Columbia vice president of sales, also focused on the future of the DVD market and movie lovers:

We entered into a business relationship with Netflix because they have developed outstanding relationships with DVD viewers, many of whom are knowledgeable about film and looking for new ways to enhance their movie viewing experience. We believe that Netflix is the way to introduce movie lovers to our films.

DVD technology was still in its infancy, requiring an investment in a (then) expensive DVD player. It took a while for the benefits of DVD technology over videotapes to become apparent to the public. Netflix had taken major advantage of the DVD’s form to ship them through the mail, creating a business model that appealed to customers who were fed up with the problems related to video rental stores, such as late fees. DVDs were a disruptive force, and Netflix promised to make them much more disruptive, bringing them directly to customers at a lower price with greater convenience and quality.

Netflix would probably have been happier if the manufacturers of DVD players, which benefited tremendously from Netflix’s enhancing the appeal of DVDs, had offered Netflix a subsidy in return for its help with DVD adoption. That, unsurprisingly, didn’t happen. Instead, Netflix turned to its suppliers, looking for a way to lower costs.

Suppliers were also benefiting from Netflix’s work because they sold Netflix a lot of expensive DVDs. However, Netflix’s inventory, once acquired, wasn’t doing much for them except suppressing sales of DVDs—people knew they could always “Netflix a movie,” instead of buying their own copy. Netflix managed to change this equation, although it meant taking a long-term revenue hit.

The solution? A deal that aligned the interests of Netflix and its suppliers, allowing Netflix to buy DVDs for $1 each, but in return granting the suppliers 40% of the revenue those DVDs generated. The lower upfront costs eased Netflix’s cash burn, and suppliers now had a greater interest in seeing Netflix succeed, but the potential revenue per customer in the long run declined.

That wasn’t the only major step Netflix took in 2000, even as it withdrew its planned IPO. It also took a risk in its customer acquisition strategy, ending the first-month-free plan and reducing the number of DVDs a customer could rent at one time from four to three. This gave new customers less than first adopters got, but at that point, Netflix had a customer base that was happy enough with the services to continue using it and spread the word.

Much to Netflix’s surprise, despite discontinuing the free-trial month, the company continued to experience extremely rapid growth. Revenue grew to $37 million during 2000, almost eight times its 1999 revenue. By March 2001, Netflix had 310,000 subscribers, a full 100% increase over the previous year. Due to fine-tuning its business model, Netflix reported positive cash flows at 500,000 subscribers in October 2001. It had a successful IPO on May 24, 2002 and raised $86 million, despite it being a lackluster period for IPOs.

Lessons Learned

Flickr and Netflix have carefully crafted web sites and substantial paying user bases. Flickr’s path forward yielded different results for a number of reasons.

Customer Acquisition Costs, Inventory, and Growth Rate

The most obvious business difference between Flickr’s digital photo-sharing community and Netflix’s DVD movie-sharing club is Netflix’s customer acquisition costs. These costs were directly tied to how much it cost to build and keep the media-lending library/inventory/database up-to-date. Flickr still has an easier time of it than Netflix, despite Netflix’s major changes, as shown in Table 1-2.

NETFLIX BEFORE REVENUE SHARING | NETFLIX AFTER REVENUE SHARING | FLICKR | |

New customer acquisition cost | $100 (five DVDs at $20/each) DVDs + $5 shipping + platform | $3 DVDs + $3 shipping + platform | 0+ Platform |

Number of customers | 300,000 after three years | 600,000 after five years | 2 million in two years |

Flickr’s digital photo database of 100 million-plus photos—85% of which are tagged—is completely user-generated. Netflix’s DVD inventory comes from suppliers that expect to be compensated. So, collective user value has an immediate and recognizable impact on the cost structure and cash flow requirements in growing a customer-focused business.

Cash Flow Curves and Time to Profitability

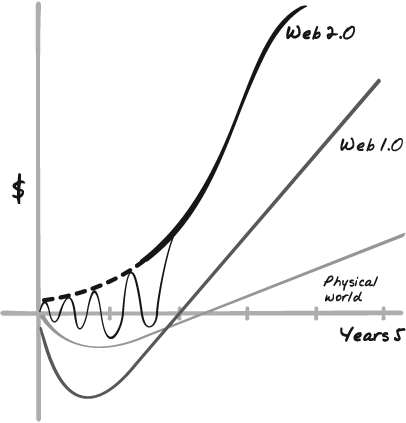

Flickr followed the Web 2.0 curve in Figure 1-9 rather than Netflix’s Web 1.0 curve or a more typical physical-world curve.

The physical-world curve shows a more traditional path to profitability and is spared the Web’s huge investment aimed at locking in users, but it doesn’t make the same kind of return, either. The Web 1.0 curve shows the higher expenses of seeking a huge audience, but also the greater return on possible investment that lured investors in. As Gil Forer, global director of Ernst & Young’s venture capital advisory group, said in a March 2007 press release:

From the investor perspective, the low capital requirements, potential high return, and the faster time from development to revenue are the primary drivers of the increase in venture capital investment in the Web 2.0 segment. In addition, success stories such as YouTube have had a positive impact both on entrepreneurs and investors.

See http://www.ey.com/global/content.nsf/International/Media_-_Press_Release_-_VentureOne_New_Web for more.

The Web 2.0 curve is different (and attractive) for a number of reasons:

- Customer acquisition costs start small

Building a community is not the same as attracting as many users as possible. The initial investment is small (although it may be a lot per user), and then the community itself helps attract users.

- Product costs are reduced

The lack of a physical inventory (or, in some cases, on-demand creation of such inventory) also reduces upfront costs.

- Development costs have shifted

The huge initial investment in hardware and software needed to build a large-scale web site has declined, as free software and low-cost—but easily extended—hardware setups have reduced the initial bite.

- Iterations change the shape of the curve

The smaller-scale, community-based model lends itself to an iterative development approach. Companies can start basic and get a revenue stream going before making major investments.

- Exponential effects play a much greater role

When a community achieves critical mass, value is created that isn’t possible for a site that is in one way or another only a catalog. As Flickr grew, its usefulness increased dramatically, drawing in more people and expanding it further.

As always, J-curves can come to a sudden halt, as there is no magic formula for success. Web 2.0’s community-based approach, however, can help lower costs at the outset when budgets are tight and increase rewards when (and if) success blossoms.

Company Financial Valuation

The total enterprise value calculation offers a customer-centered approach to valuing a company, but it is only one of many different tools analysts and managers use to determine company value.

As noted earlier, Flickr’s final separate valuation was the $40 million that Yahoo! paid for it. It’s not entirely clear how that value was determined, but working backward from the total enterprise calculation suggests that each customer is worth about $20. Because Flickr’s primary assets are its customers and its brand (which ties the company to the customers), it seems likely that the valuation was based on customers.

By contrast, Netflix went to the public market, and its IPO brought in $86 million. The total enterprise value calculation suggests that 600,000 customers with a lifetime value of $20 should have been worth about $12 million. The expected value of a Netflix subscriber according to the simplified calculation on page 27 is noted to be about $60/year/per subscriber if 28% of long-termers end up becoming a loyal subscriber for five years. So the market likely took into account for Netflix’s IPO value, the continuing market shift towards DVDs away from DIVX and VHS, the solid subscription-based revenue stream of loyal customers over 5 years time plus the growing inventory value of millions of new release DVDs distributed efficiently without retail & retail costs.

Entrepreneur/Founders’ Net Worth at Exit

Company valuations also influence a financial calculation—net worth at exit—that is very important to the entrepreneur/founders of a startup company like Netflix or Flickr.

Netflix, like many companies founded during the dot-com era, was funded by venture capitalists. But Flickr, like many of the companies founded with Web 2.0 technologies, had such low capital, inventory, marketing, and development costs that the two cofounders never needed to take venture capital funds to grow their startup into a profitable and sustainable company. This allowed them to retain a large proportion of their equity ownership, which ended up being worth around $40 million to Yahoo!.

When Netflix received its $86 million from the IPO, the venture capitalists that had waited five years for Netflix to break even and become profitable needed to receive an internal rate of return (IRR) of about 50% for their patience with a continued risky investment. That leaves the likely net worth of the original founders at IPO, five years after launch, with a lowered percentage ownership due to multiple funding rounds and cash flow issues.

Questions to Ask

Flickr and Netflix may seem far from your own plans, whether they include an existing business or a startup. The following questions will help you evaluate the lessons of this chapter and possibly apply them to your own projects.

Strategic Questions

- Consider how your business and industry currently work...

To what degree have you opened up to collective user value—multiplying the ways that users inside and outside of your project, team, or organizational unit can easily leverage, aggregate, and spark collective work, knowledge, and systems?

- If you took the perspective of a CEO and strategic leader...

How and when do you see Web 2.0-enabled collective user value disrupting the current practices, business model, competitive advantages, and economics of your business and industry? What’s the risk of being a leader or laggard? When should this become a boardroom agenda item?

- If you took the perspective of a CIO and program manager...

How could you better benchmark, analyze, compare, and quantify the impact of shifts in collective user value and community in key functional areas, such as marketing and sales, product and services development, customer support, inventory management, logistics and operations, recruitment and training, partner and supplier relations and procurement? How can quantifying new customer acquisition costs, cash flow curves, per-user analytics, and per-click metrics provide a new basis for enterprise and financial valuation?

- If you are a project team member...

Are you ready to brainstorm together with your group members on how the collective user value practices described for Flickr could be applied effectively in your business—whether consumer-focused or industrial, product or service-oriented, offline or online, local or global, small or large? What event could become a pilot project?

Tactical Questions

Are your web site, storefront, web presence, development ecosystem, and user experience aligned with and open to collective user value best practices?

Are you (or is your management) comfortable with letting users have their own independent voices on your site?

Do you allow users to participate on your site? Can they share their own questions and ideas there?

How do you attract users to participate on your site? What brings them there initially, and what encourages them to come back?

What features of your site help users make connections with each other? Can users form groups with other users?

How sense-rich is the participation you support? Can users present sound, video, or even just formatted text?

Do you provide mechanisms (tagging, for example) to help users create their own navigation through your site?

Do you support user annotation of your site?

How could your site learn from user behavior and adapt itself to users? Which categories of user behavior have the most potential in your situation?

How do you encourage users to bring other people to your site?

How do you encourage users to share information in public, where it can generate positive network effects? In other words, is your site “public by default”?

Can you create—or tighten—feedback loops between user requests and your company’s ability to fulfill them?

Can users keep up with your site through syndication—RSS or similar approaches?

Do you provide programming interface (API) access to developers who want to combine, or mash up, the contents of your site with complementary materials from elsewhere?

What licensing do you use for your site contents? And what licensing can users specify for their own contributions? (For example, All Rights Reserved versus Creative Commons with some rights reserved.)

Do users feel they can control their information once they’ve entrusted your site with it? Can they extract it later?

How do you support your active community members?

Is there an opportunity to charge for the services your site provides? If so, can you structure those charges so that the people benefiting most directly from your site are the ones paying, while those contributing pay less or nothing?

[7] Fred Wilson, “A VC: The Freemium Business Model,” Fred Wilson’s blog, comment posted on March 23, 2006, http://avc.blogs.com/a_vc/2006/03/the_freemium_bu.html.

[8] Katherine Heires, “Why It Pays to Give Away the Store,” Business 2.0, http://money.cnn.com/magazines/business2/business2_archive/2006/10/01/8387115/index.htm.

[9] Fast Company 50 interview with Stewart Butterfield, “Reinventing a category whose flashbulb burnt out,” http://www.fastcompany.com/magazine/archives/2005.

[10] Daniel Terdiman, “Folksonomies Tap People Power,” Wired.com, Feb. 1, 2005, http://www.wired.com/science/discoveries/news/2005/02/66456.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Kurt Indvik, “Rev-Share Still Lives,” Rentrak News online, Sept. 16, 2005,http://www.rentrakonline.ca/content/news/news_09-16-05.html.

[13] “NetFlix Signs Revenue-sharing Pacts with Warner, Columbia,” Ultimate AV magazine online, Dec. 17, 2000, http://ultimateavmag.com/news/10893/.

[14] Ibid.

[15] “Netflix announces agreements with major motion picture distributors,” Netflix press release, Dec. 6, 2000, http://www.netflix.com/MediaCenter?id=1024.

[16] Ibid.