Peers, Politics, and the Future of Democracy

Civic Talk

In the series The Social Logic of Politics

edited by Alan Zuckerman

Also in this series:

Alan S. Zuckerman, ed., The Social Logic of Politics:

Personal Networks as Contexts for Political Behavior

James H. Fowler and Oleg Smirnov, Mandates, Parties, and Voters: How Elections Shape the Future

Simon Bornschier, Cleavage Politics and the Populist Right:

The New Cultural Conflict in Western Europe

TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia

Casey A. Klofstad

Peers, Politics, and the Future of Democracy

TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122 www.temple.edu/tempress

Copyright © 2011 Temple University All rights reserved Published 2011

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Klofstad, Casey A. (Casey Andrew), 1976-

Civic talk : peers, politics, and the future of democracy / Casey A. Klofstad. p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4399-0272-1 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4399-0274-5 (electronic)

1. Communication in politics—United States. 2 Communication—Political aspects—United States. 3. Political participation—United States. I. Title.

JA85.2.U6K56 2010

320.97301 '4—dc22 2010018213

The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992

Printed in the United States of America

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1

For Rindy

|

Preface |

ix | |

|

Acknowledgments |

xi | |

|

1 |

Introduction |

1 |

|

2 |

Civic Talk and Civic Participation |

11 |

|

3 |

Does Civic Talk Cause Civic Participation? |

29 |

|

4 |

Why Does Civic Talk Cause Civic Participation? |

51 |

|

5 |

Do You Matter? |

71 |

|

6 |

Do Your Peers Matter? |

91 |

|

7 |

The Significant and Lasting Effect of Civic Talk |

109 |

|

8 |

Peers, Politics, and the Future of Democracy |

127 |

|

APPENDIX A: The Collegiate Social Network Interaction Project (C-SNIP) |

143 | |

|

APPENDIX B: C-SNIP Panel Survey Questions and Variables |

151 | |

|

APPENDIX C: Matching Data Pre-processing |

161 | |

|

References |

165 | |

|

Index |

175 |

During my first two years of graduate school, I became interested in the sociological antecedents of public opinion and political behavior. At that time, the tools I had at my disposal to address this topic were publicly available survey data and a variety of methods of statistical analysis. Using these tools, I convinced myself that engaging in political discussion with friends, family, and other peers—what I call "civic talk”—led people to become more active in civil society. As soon as I had written my first paper on this subject, however, I was challenged in a research workshop with a number of indictments, such as "endogeneity,” "reciprocal causation,” and "selection bias.” In plain English, with survey data from one period in time, I was unable to show whether our peers influence our behavior or our patterns of behavior influence how we select and interact with our peers.

This experience left me wondering how I could possibly study a phenomenon that is shrouded in such deep analytical complexity. It was at that point that I took a step back from my research question and appealed to the simplest tenets of the scientific method. I had a hypothesis that civic talk causes civic participation. All I needed now was a way to test the hypothesis with an experiment. Ideally, to do this I would randomly assign people to new peer groups, some of whom engaged in civic talk and others of whom did not. Random assignment would ensure that any observed effects would be attributable to civic talk and not any other factor.

Unfortunately, unless you are the producer of a reality television show, this ideal research design is not feasible. As much as we may want to, we cannot simply pick a representative sample of individuals and randomly assign them to new social circles. So, instead, I found a situation in nature that approximated my ideal: I conducted a panel study of first-year college students who had been randomly assigned their dormitory roommates. I also conducted a series of focus groups to gain a richer qualitative understanding of civic talk and its effect on civic participation.

As the following pages show, these data give us an unprecedented level of confidence in the notion that civic talk has a meaningful and lasting effect on an individual’s patterns of civic participation. Given that citizens’ involvement in civil society is essential to the survival of democracy, this book shows that our peers have a critical role to play in maintaining this form of governance. Moreover, these results illustrate that extant theories of civic participation are incomplete because they focus on individual-level antecedents to the exclusion of sociological ones. Humans may not be Aristotelian political animals, but we certainly are social animals. This simple fact needs to be incorporated into our understanding and study of democracy.

A number of people provided invaluable feedback and advice as I completed this project. First, I thank David Campbell. His comments at the Harvard University Political Psychology and Behavior Workshop led me to design the study presented in this book. I am also indebted to the members of my dissertation committee for their guidance and training: Barry Burden, Theda Skocpol, and Sidney Verba. My sincere thanks go to the many friends, colleagues, anonymous referees, and conference participants who have commented on this project. I specifically thank Ben Bishin (who put me in contact with Temple University Press), Merike Blofield, Louise Davidson-Schmich, Jeff Drope, Bob Huckfeldt, Kosuke Imai, Gary King, Lisa Klein, Scott McClurg, David Nickerson, Meredith Rolfe, Tony Smith, Hillel Soifer, Anand Sokhey, John Stevenson, Laura Stoker, Elizabeth Stuart, and Kathy Walsh. I also am very grateful to Mary Rouse, former dean of students and former head of the Morgridge Center for Public Service at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, for her insight and encouragement. Finally, I will always be indebted to Mike Fischer, Jack Dennis, and the University of Wisconsin Survey Center for giving me my start in this field.

A number of agencies supplied monetary and research support for this project. I am deeply indebted to the University of Wisconsin Survey Center for administering the studies presented in this book. Grants from the American National Election Studies, the Harvard University Center for

American Political Studies, and the University of Miami helped to defray the cost of this research. I am also indebted to the National Science Foundation, the Harvard University Center for American Political Studies, the Harvard University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and the University of Miami for financial support through various fellowships and awards.

My thanks go to Louis Menand for permission to reprint a portion of his article "The Unpolitical Animal,” which appeared in the August 30, 2004, edition of the New Yorker (published by Conde Nast). I am also grateful to the following journals for permission to reprint previously published material: Social Forces (with permission from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill) for Casey A. Klofstad, "The Lasting Effect of Civic Talk on Civic Participation: Evidence from a Panel Study,” vol. 88 (2010): 2353-2375; Public Opinion Quarterly (with permission from Oxford University Press) for Casey A. Klofstad, Scott McClurg, and Meredith Rolfe, "Measurement of Political Discussion Networks: A Comparison of Two ‘Name Generator’ Procedures,” vol. 73 (2009): 462-483; American Politics Research (with permission from Sage Publications) for Casey A. Klofstad, "Civic Talk and Civic Participation: The Moderating Effect of Individual Predispositions,” vol. 37 (2009): 856-878; and Political Research Quarterly (with permission from Sage Publications) for Casey A. Klofstad, "Talk Leads to Recruitment: How Discussions about Politics and Current Events Increase Civic Participation,” vol. 60 (2007): 180-191.

Finally, my sincere thanks go to the 2003-2004 and 2007-2008 first-year undergraduate classes of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, as well as to my editor, Alex Holzman, and the rest of the staff at Temple University Press. Without their help, this book would not have been possible.

Civic Talk

The process of selecting the forty-fourth president of the United States began in the State of Iowa. On January 3, 2008, tens of thousands of Iowans braved the below-zero cold of winter, and took time away from their jobs and families, to gather in town halls and school gymnasiums to express their preference for the nominees of the Democratic and Republican parties. At the end of the caucuses, Senator Barack Obama of Illinois emerged as the Democratic Party’s winner, with 38 percent of the vote. In doing so, Senator Obama beat out two better-known candidates: John Edwards, former senator from North Carolina and vice presidential candidate in 2004, and Hillary Clinton, senator from New York and former first lady of the United States.

Senator Obama’s victory in the 2008 Iowa caucuses was an extraordinary achievement. Despite the legacy of slavery and a history of contentious race relations in the United States, a state with a white population of more than 90 percent chose to give a plurality of its votes to an African American candidate. Moreover, Obama entered the 2008 race for the presidency as a relatively outsider candidate. A poll taken in Iowa in March 2007 by the University of Iowa showed Obama to be running a distant third behind Clinton and Edwards. Even on the eve of the caucuses, a poll taken in the State of Iowa by the American Research Group showed Obama losing to Clinton—at that time the presumptive Democratic Party nominee—by 9 percentage points. Nonetheless, Obama came out on top in Iowa.

On their own, the Iowa caucuses did not secure Barack Obama’s place in history as the first-ever African American president of the United States. They were, however, a significant critical juncture in the 2008 elections. Winning in Iowa gave Obama the electoral credibility, media exposure, and campaign funds that he desperately needed to continue to compete throughout the rest of the country against his more favored opponents. While we will never know what would have happened if Obama had lost the Iowa caucuses, suffice it to say that the victory propelled him toward the White House.

How did this extraordinary moment in history occur? The story of Rex Boyd gives us insight into how Senator Obama overcame such steep odds in Iowa on his road to the presidency.1 Rex went with his wife, Nell, to his local caucus expecting to cast his vote for Senator Clinton. However, after chatting with people from his community about the candidates, he switched his support to Senator Obama. Had Rex lived in a state with a primary election system instead of a caucus, he probably would have cast his vote for Senator Clinton, as he had originally intended. Instead, by participating in the caucus, he was exposed to the views of the people in his community. These interactions with his fellow citizens caused Rex to switch his support to Senator Obama and, as a consequence, helped shift the course of the 2008 presidential election.

Rex Boyd’s experience at the 2008 Iowa caucuses is what this book is about: the influence that citizens have on each other and on the political system when they discuss politics and current events. I call these types of discussions "civic talk.” In the chapters that follow, I use a number of unique sources of data to show how and why civic talk affects how we participate in civil society and, as such, how civic talk plays a central role in maintaining the strength of participatory democracy. In this chapter, I lay down the foundation of this argument by showing how our understanding of the relationship between civic talk and civic participation can be made clearer with new sources of evidence. I then preview the results that will be presented in subsequent chapters.

A Research Agenda Focused on the Individual

Without civic participation there is no democracy. Popular sovereignty is based on the ability of citizens to freely express their wishes to the government and, if necessary, prevent that government from committing acts of tyranny. Along with protecting popular sovereignty, civic participation facilitates democratic governance. Citizens who are active in the public sphere demand, and subsequently tend to receive, better governance from elected officials and political institutions.

Because the active involvement of citizens in the processes of governance is so essential to the survival of democracy, civic participation has been heavily studied. Most of what political scientists know about whether an individual chooses to enter the public sphere is based on studies of individual-level characteristics. Arguably, one of the best examples of this brand of scholarship is Verba and colleagues’ (1995) seminal volume Voice and Equality. Of the myriad factors that might influence an individual to participate in civic activities, Verba and his colleagues focus their attention on resources (i.e., one’s available free time, income, and civic skills) and civic engagement (i.e., one’s interest in politics and current events).2 Using survey data collected in the United States, they show that individuals with more resources and higher levels of engagement with politics and current events are more likely to participate in civic activities. Resources and engagement function in this manner because they make civic participation less costly and more beneficial. For example, the more money one has, the less costly it is to make a donation to an interest group or political candidate. Or the more interested one is in politics, the more enjoyable it is to participate in that process.

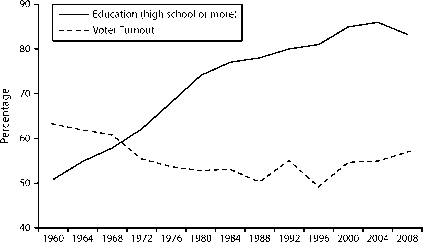

While political scientists’ focus on individual-level characteristics has significantly increased our understanding of how and why citizens choose to engage in civic activity, we are nonetheless left with many questions about this form of human behavior. One of the best examples of why civic participation continues to be a mysterious phenomenon is the relationship between educational attainment and civic participation. On an individual level, there is an extremely tight correlation between education and civic participation; the better educated you are, the more likely you are to participate in civil society. Like income, education is a resource that makes participation in civic activities easier for the individual. For example, the better educated you are, the more you know about the political system and the easier it is for you to become involved in that system.

FIGURE 1.1 Education and voter turnout over time in the United States

Sources: Education was measured with data from the American National Election Studies Time Series Study. Voter turnout is calculated as the number of voters divided by the voting age population. Turnout figures were compiled from the U.S. Election Assistance Commission and the U.S. Election Project.

Shifting the Agenda to Include Social-Level Variables: The Need for New Evidence

Despite the fact that focusing on individual-level variables has left political scientists with an incomplete understanding of why people choose (or do not choose) to participate in civic activities, social-level variables such as civic talk have been overlooked by most political scientists. Sociological studies of participatory democracy have been relegated to the background of the field because it is difficult to determine whether the people in our social environment influence us, or whether our own patterns of behavior influence how we choose and act with the people around us (see, e.g., Klofstad 2007; Laver 2005; Nickerson 2008).

For example, a number of scholars have shown that the amount of civic talk occurring in an individual’s social network correlates with his or her level of civic participation, even after controlling for a host of alternative explanations (Campbell and Wolbrecht 2006; Huckfeldt and Sprague 1991, 1995; Huckfeldt et al. 1995; Kenny 1992, 1994; Lake and Huck-feldt 1998; McClurg 2003, 2004; Mutz 2002). However, we cannot conclude that civic talk is causing civic participation with this type of evidence. One problem associated with this form of analysis is reciprocal causation; an equally plausible explanation for the relationship between civic talk and civic participation is that being civically active causes an individual to talk about politics and current events with his or her peers. Another problem is selection bias. Individuals who are more active in civic activities might consciously choose to associate with people who are more interested in talking about politics and current events. Finally, some factor that has not been accounted for could be causing people to both talk about politics and participate in civic activities (i.e., endogeneity or omitted variable bias).

How can we overcome these problems and subsequently increase our understanding of participatory democracy? One way would be to randomly assign individuals to new peer groups and then track how their patterns of behavior change over time in response to interacting with this new set of peers. This ideal research design would allow us to determine causation because it follows the logic of a controlled experiment. First, an individual enters a new randomly assigned social setting. Second, some of these peer groups are randomly selected to engage in civic talk (i.e., to be "treated” with civic talk), while the remainder of the peer groups being studied are not allowed to engage in such discussions. Finally, the effect of being exposed to civic talk on subsequent patterns of behavior is measured by comparing the behaviors of individuals who were exposed with the behaviors of those who were not. Random assignment to treatment allows us to be confident that the outcomes of the study are actually being caused by civic talk and not any other observed or unobserved factors.

I designed the Collegiate Social Network Interaction Project (C-SNIP) in line with this ideal research design. The cornerstone of the study is a panel survey I conducted on the 2003-2004 first-year class of students at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Random assignment is incorporated into the study design because the participants were assigned to their college dormitories based on a lottery. Participants in the C-SNIP Panel Survey initially completed two survey questionnaires over the course of the 2003-2004 school year—one at the beginning of the school year before they engaged in civic talk with their randomly assigned roommate, and a second at the end of the school year after they engaged in civic talk. During the first wave of the study, each student was asked about his or her patterns of civic participation during high school. During the second wave of the study, students were asked about their civic activities in college, as well as about their randomly assigned roommate. These students also completed a follow-up survey during their fourth (and likely final) year of college in 2007.

While most of the evidence I present in this book comes from the C-SNIP Panel Survey, those results are verified with data that I gathered through a series of focus groups conducted on the 2007-2008 first-year class at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. These students, like the 20032004 cohort of students who participated in the C-SNIP Panel Survey, were also randomly assigned to their first-year dormitory roommates.

Overview of the Book

The remainder of this book proceeds as follows. Chapter 2 begins my argument for the need to include civic talk in the civic participation research agenda through an examination of the extant literature. The conclusion reached from this discussion is that new evidence is needed to substantiate and explain the causal relationship between civic talk and civic participation. The C-SNIP Panel Survey and Focus Group Study are presented as a next-best alternative to a fully controlled laboratory experiment because they leverage random assignment to peer groups and document change in behavior over time.

Chapter 3 begins with a descriptive assessment of civic talk. My data show that civic talk is less frequent than other forms of discussion, but it is still pervasive. The data also show that civic talk typically occurs in response to, and with regard to, an election, what issues are being covered in the news, and other such current events. Most important, the C-SNIP data also show that discussing politics and current events has a positive effect on participation in a variety of civic activities. For example, C-SNIP Panel Survey respondents who engaged in civic talk were 38 percent more active in voluntary civic organizations and were 7 percentage points more likely to have voted in the 2004 presidential primary.

Chapter 4 is dedicated to answering why civic talk influences our patterns of civic participation. Talk, in and of itself, cannot be what is causing individuals to take action. So what is it about these conversations that leads us to participate? The answer is recruitment and engagement. When we converse about politics and current events with our peers, they explicitly ask us to get involved. In addition, engaging in civic talk correlates with enhanced interest in politics and current events.

Chapters 5 and 6 dig more deeply into the C-SNIP data sets by examining the factors that might enhance or mitigate the positive relationship between civic talk and civic participation. Chapter 5 focuses on the characteristics of the individual who is engaging in civic talk. Evidence from the C-SNIP studies shows that not all individuals get the same participatory boost from discussing politics and current events. Instead, those of us who are already predisposed to participate in civil society—for example, those with prior participatory experience—get the most out of engaging in civic talk. Consequently, when asking who among us gains from engaging in civic talk, the answer is that only the politically savvy among us do.

Chapter 6 shifts focus from the individual’s characteristics to the characteristics of his or her peers. One hypothesis tested is whether peer groups with greater levels of political knowledge and interest (“civic expertise”) are better equipped to motivate individuals to participate in civic activities. The C-SNIP data show that this is the case; individuals are more likely to participate in civic activities when they engage in civic talk with people who have civic expertise. This chapter also engages the unresolved debate on whether political disagreement among peers depresses civic participation (see, e.g., Huckfeldt et al. 2004; Mutz 2006). The C-SNIP data show that individuals who agree with their peers get more of a participatory boost out of engaging in civic talk compared with those who disagree with their peers. However, the data also show that exposure to disagreement does not depress civic participation. In conclusion, Chapter 6 shows that social intimacy increases the effect of civic talk. For example, the more you trust your peers, the more influence they have over you when engaging in civic talk.

Chapter 7 answers three additional questions about the effect of civic talk on participatory democracy. First, given the extant literature’s focus on individual-level antecedents of civic participation, how does the effect of civic talk compare with the effect of one’s individual characteristics? The C-SNIP Panel Survey data show that the effect of civic talk is typically equal to or greater than the effect of individual-level antecedents of civic participation. Second, while civic talk has a significant effect on civic participation, does it have an effect on other attitudes and behaviors? The C-SNIP Panel Survey data show that civic talk has a significant effect on other civically relevant attitudes and behaviors, such as knowledge about and psychological engagement with politics. Finally, does the effect of civic talk last beyond the initial point of exposure? The third and final wave of the C-SNIP Panel Survey is used to answer this question. These data show that the effect of civic talk lasts beyond the initial point of exposure—in this case, three years into the future. Further analysis shows that the boost in civic participation initially after engaging in civic talk is the mechanism by which the effect of civic talk lasts into the future. In whole, this final set of results further illustrates the significant and lasting effect that conversations about politics and current events have on participatory democracy.

Chapter 8 concludes this examination of civic talk with an assessment of the normative implications of the relationship between civic talk and civic participation, as well as a discussion of the future agenda of researchers of and practitioners in civil society. The main conclusion reached from this discussion is that, while civic talk cannot answer all of the questions researchers and practitioners face, this form of social influence has a powerful effect on participatory democracy and is thus worthy of our continued attention.

Because civic participation is so integral to the performance of democracy, the question of what causes a person to step out of his or her private life and enter the public sphere has been a subject of constant study in the social sciences. Of the numerous explanations that have been generated for why and how individuals choose to participate in the processes of democratic governance, no one theory has a monopoly on the truth. One thing we do know, however, is that the people around us have a place on this list of explanations. Just like Rex Boyd at the 2008 Iowa caucuses, we experience politics with and through the individuals in our social environment.

Against this seemingly logical presumption, research on civic participation has been dominated by theories and research that negate sociological factors and instead focus on individual-level characteristics to explain civic behavior. This said, a growing number of studies assert that social context can have a meaningful impact on how we participate in civil society. More specifically, many have suggested that civic talk can cause people to participate in civic activities. However, political scientists have heavily criticized this line of argument because we have been unable to accurately measure the causal relationship between civic talk and civic participation. Consequently, the question of how civic talk and participatory democracy are related to each other has remained unresolved. In the pages that follow I provide an answer to this question.

2

Civic Talk and Civic Participation

It seems at least plausible that those explicitly named by respondents as people with whom they discuss politics may be a biased selection of those with whom politics is actually discussed.

—Michael Laver (2005, 934)

In this chapter I lay down the foundation of my argument by examining the existing scholarship on civic talk and civic participation. I then show how our understanding of the relationship between these two phenomena can be made clearer with new evidence. In the chapters that follow, I use a number of different sources of data to show how and why civic talk affects how we participate in civil society.

Civic talk is the informal discussion of politics and current events that occurs within a social network of peers: the friends, colleagues, family members, and other individuals who are present in our social environment. A variety of examples of this type of behavior exist, including talking about the news of the day over a family dinner, discussing the economy during a coffee break at work, chatting among patrons at a bar about the current election, and other such informal discussions. Typically, these types of interactions are not purposively sought. Instead, civic talk is usually an unintended byproduct of people going about their normal daily routine (Downs 1957; Klofstad et al. 2009; Walsh 2004). For example, a husband and wife might sit down to dinner together and end up discussing the issues that were covered in the news that day, or a group of friends socializing at a party might end up talking about the current election, or co-workers might end up discussing the state of the local school system during a lunch break.

Because civic talk is "accidental,” it is important to underscore that it is distinct from another form of political discussion that is examined in the political science literature: deliberation. In contrast to the informal nature of civic talk, deliberation is a more formal process where citizens are brought together for the expressed purpose of formulating government policy (Barabas 2004; Conover et al. 2002; Delli Carpini et al. 2004; Mendelberg 2002; Page and Shapiro 1992). Civic talk is not as purposive or formal as deliberation.

If civic talk is a natural part of daily life, how often do we engage in it? Politics and current events may not be at the top of everyone’s list of favorite discussion topics, but most of us do engage in civic talk at least from time to time. For example, respondents to the 2008-2009 American National Election Studies Panel Study were asked, "During a typical week, how many days do you talk about politics with family or friends?” About 91 percent of respondents said they engaged in such discussions at least once a week. On average, respondents reported that they engaged in civic talk about three days per week.3

TABLE 2.1 Composition of political and core discussion networks

|

Political discussion network |

"Important matters” discussion network |

Subset of "important matters” network that discusses politics | |

|

Spouses (%) |

13 |

16 |

17 |

|

Other family members (%) |

25 |

30 |

30 |

|

Coworkers (%) |

23 |

15 |

15 |

|

"Close” friends (%) |

66 |

73 |

74 |

Sources: 1996 Indianapolis-St. Louis Study (Huckfeldt and Sprague 2000). This table is a partial reproduction of Table 2 in Klofstad et al. (2009).

If most people do engage in civic talk, at least sometimes, then who do they talk to? Because civic talk is a byproduct of going about our normal everyday lives, people do not typically seek out specific individuals with whom to talk about politics and current events. Instead, we tend to talk about these matters with the same set of people with whom we discuss other topics (Huckfeldt and Sprague 1995; Klofstad et al. 2009; McClurg 2006; Mutz 2002; Walsh 2004). Table 2.1 offers an illustration of the overlap between political and non-political discussion networks. These data come from the 1996 Indianapolis-St. Louis Study conducted by Huckfeldt and Sprague (2000). That study is uniquely tailored to answering the question of who we discuss politics and current events with because it used two different methods to collect information on civic talk. Half of the respondents in this study were randomly selected to provide information on the individuals with whom they discussed "important matters” in their life. The other half of the respondents were asked to provide information on the individuals with whom they specifically "discuss politics.”4

The data presented in Table 2.1 show that political discussion networks consist of more or less the same people with whom we discuss other matters. The data in the first two columns of the table suggest that "important matters” discussion networks are, perhaps, a bit more socially intimate. Political discussants are less likely to be spouses (t = -2.45, p = .01) or family members (t = -3.20, p < .01), and more likely to be coworkers (t = 6.63, p < .01) when compared with "important matters” discussants. And while members of the political discussion network are as likely as "important matters” discussion partners to be considered "friends,” they are less likely to be considered "close friends” (t = -4.36, p < .01). However, while statistically significant, most of these differences are not substantively large. Moreover, comparison of the second and third columns of Table 2.1 shows that the individuals we choose to discuss politics with in our core "important matters” social networks look like the rest of the individuals in that network. Otherwise stated, in going about our daily lives we tend to engage in civic talk with the same people with whom we discuss other topics.

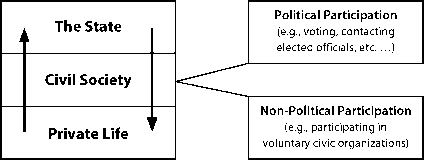

FIGURE 2.1 What is civic participation?

What Is Civic Participation?

The dependent variable of interest in this book is civic participation. "Civic participation” is a term that is used frequently in academic writings and the popular press these days. This is especially the case because many observers feel that we are in an era of civic disengagement in the United States (see, e.g., Putnam 2000). However, while “civic participation” has become a common term in everyday language, it is important to clarify what this phenomenon is and why it is important for our understanding of how democracy works.

Simply stated, civic participation is activity that draws individuals out of their private lives and into civil society. The diagram in Figure 2.1 presents this definition graphically. The left-hand side of the figure represents a simple society, showing government at the top, and each individual’s private life—or the “private sphere”—at the bottom. In between the state and private life we find civil society, or the “public sphere.” Civil society is the space where citizens are able to step out of their private lives and associate with one another. This space is both literal, as in the local town square where citizens congregate, and figurative, as in the rights to assemble and speak freely while you are in the town square.

The upward-facing arrow in Figure 2.1 illustrates the ways in which civil society upholds popular sovereignty. The arrow symbolizes the ability of citizens to articulate their views to the government by voting, engaging in protests, contacting their legislators, and other such activities. The upward-pointing arrow also symbolizes the fact that participation in public life gives citizens the means to push back against the government to prevent tyranny. In other words, civil society serves as both a bridge and a barrier between the state and the private sphere (Foley and Edwards 1996; Gellner 1995; Hall 1995).5

In addition to protecting popular sovereignty, civic participation is important because it facilitates democratic governance, symbolized by the downward-pointing arrow in Figure 2.1 (Mayhew 1974; Putnam 1993, 2000). For example, Putnam (1993) shows that, despite having similar institutional structures, regional governments in the north of Italy provide better services to their citizens than do those in the south. Even after accounting for a host of alternative explanations, Putnam finds that this variation in governmental performance can be explained by the fact that northern Italians are more active in civil society than are their neighbors to the south (what he calls the strength of the "civic community” or "social capital”). In a more recent study, Putnam (2000) also makes the same claim about the United States. Civil society facilitates democratic governance because civically active citizens demand, and thus tend to get, better policies from the state. Moreover, organizations within civil society can aid in the development and implementation of policy solutions—for example, a soup kitchen can help the state fight hunger and homelessness, an after-school program can help the government combat juvenile delinquency, and the like.

Many different types of behavior fit under this broad definition of civic participation as participation in civil society. The right-hand side of Figure 2.1 splits this large set of activities into two categories: political and nonpolitical civic participation. Under this rubric, civic activities are distinguished based on whether the activity in question directly influences the democratic governing process (Putnam 2000; Tocqueville 2000; Verba et al. 1995; Zukin et al. 2006).

Political civic participation is activity that is aimed at directly influencing the government (see, e.g., Brady 1999; Putnam 2000; Verba et al. 1995). Examples of political civic activities include voting, participating in parties and interest groups, contacting elected officials about important issues, marching or protesting, and working on political campaigns. On the other side of the civic participation coin, we find non-political civic activities. These are activities that pull individuals out of their private lives and into the public sphere but that have no intentional influence on the processes of democratic governance. In practice, non-political civic activity is conceived of and measured as participation in voluntary membership organizations (Putnam 2000; Skocpol 2003; Tocqueville 2000; Verba et al. 1995). Examples include professional associations, philanthropic organizations, civic leadership groups such as the Elks and the Knights of Columbus, education organizations such as Parent-Teacher Organizations and Parent-Teacher Associations, religious groups, and the like.

In thinking about the distinction between political and non-political civic activities it is important to note that non-political civic activities could have unintended consequences on the governing process. For example, by volunteering in a soup kitchen an individual could have an effect on how the government addresses issues such as homelessness and unemployment. Or by attending a meeting of a religious organization, an individual could be exposed to requests to support a political candidate or party. These examples highlight the fact that the dividing line between political and non-political civic activities is not perfectly definitive. This is especially the case in the United States, where, compared with other industrialized democracies, government is more limited and civil society is more vibrant (Tocqueville 2000; Verba et al. 1995). This said, some method of classifying and distinguishing between the vast numbers of civic acts is needed, and the political-non-political taxonomy serves this purpose. Moreover, as subsequent chapters will show, civic talk can have different effects on how active individuals choose to be in political and non-political civic activities.

Based on these definitions of “civic talk” and “civic participation,” a question some will have is whether treating civic talk and civic participation as distinct variables is tautological. More specifically, one might argue that informal discussion among peers about politics and current events is itself an act of civic participation. However, while civic talk and civic participation are closely related—this is the central theme of this book—they are distinct concepts.

With reference to Figure 2.1, civic talk is defined and measured as informal discussions that occur in the private sphere. In contrast, civic participation is activity that occurs in the public sphere. The existing body of political science scholarship supports this distinction. For example, through an extensive survey of existing scholarship, Brady (1999, 737; emphasis in the original) concludes that political participation “requires action by ordinary citizens directed towards influencing some political outcomes.” Thus, since “political discussion is not an activity aimed—directly or indirectly—at influencing the government” (Verba et al. 1995, 362), civic talk is not in itself an act of civic participation.

Social-Level Antecedents of Civic Participation

Now that the independent and dependent variables of interest in this study have been defined, we need to ask what we already know about their relationship to each other. Admittedly, this is not a new research question. Observers as far back as Alexis de Tocqueville, in his seminal study Democracy in America that was conducted in the 1830s, have noted that there is a strong relationship between how individual citizens interact with one another and how well democracy functions.6

In this same spirit, a number of different lines of contemporary social science research have addressed the effect that social-level factors have on various attitudes and behaviors. For example, works in sociology and social psychology show that individuals emulate the attitudinal and behavioral norms of their social network (Festinger et al. 1950; Latane and Wolf 1981; Michener and DeLamater 1999). Economists and sociologists have shown that one’s college roommate can influence a variety of behaviors, such as scholastic achievement (Sacerdote 2001) and binge drinking (Duncan et al. 2005). Research on households shows that people living under the same roof can influence one another to vote (Nickerson 2008). As discussed earlier, the literature on public deliberation shows that individuals become more informed about politics through the process of formulating policy options with other citizens (Barabas 2004; Delli Carpini et al. 2004; Page and Shapiro 1992; Mendelberg 2002). Works on social capital and cooperation illustrate that interacting with fellow citizens causes individuals to have a greater sense of attachment to community, which leads to more frequent participation in civic activities (Dawes et al. 1990; Putnam 2000; Sally 1995). Research on political communication, opinion formation, the mass media, and political socialization shows that the individuals around us influence how we learn about politics because civically engaged individuals provide the rest of us with information about politics (Alwin et al. 1991; Barker 1998; Dawson et al. 1977; Downs 1957; Lazarsfeld et al. 1968; Newcomb 1943; Newcomb et al. 1967; Silbiger 1977; Stimson 1990; Zaller 1992).7

With regard to research specifically on civic talk, a number of works have examined the relationship between political discussion and civic participation (Campbell and Wolbrecht 2006; Huckfeldt and Sprague 1991, 1995; Huckfeldt et al. 1995; Kenny 1992, 1994; Lake and Huckfeldt 1998; McClurg 2003, 2004; Mutz 2002). These studies suggest that civic talk has an influence on how individuals view and participate in politics. For example, using a national survey of the United States, Lake and Huckfeldt (1998) show that the amount of political discussion occurring in an individual’s social network correlates with his or her level of political participation, even after controlling for a host of alternative explanations. Beyond showing a positive relationship between civic talk and civic participation, more recent works on social networks have attempted to identify the mechanisms that allow individuals to translate discussion into action. For example, in an analysis of Huckfeldt and Sprague’s (1995) data set from South Bend, Indiana, McClurg (2003) shows that peers are an important source of information on politics and current events (also see Downs 1957). Information motivates participation because it increases civic competence (the ability to participate) and civic engagement (having an interest in participating in the first place).

Difficulties Producing Evidence of Causation

Based on the large amount of research that has already been conducted on sociological antecedents of civic participation, it is fair to ask why additional study of this phenomenon is needed. While there is a growing body of literature on civic talk and other related sociological phenomena, the vast majority of political scientists have discounted this line of research. Scholars have expressed serious skepticism about the role of civic talk in encouraging civic participation because conclusive evidence of a causal relationship between these two variables has not been found. Causation has not been shown because it is difficult to determine whether the people in our social environment influence us or whether our own patterns of behavior influence how we choose and act with the people around us (Klofstad 2007; Laver 2005; Nickerson 2008).8

An example helps illustrate why it is difficult to show a causal relationship between civic talk and civic participation. Existing works show a strong correlation between how much a person talks with his or her peers about politics and how active that person is in civic activities (Campbell and Wolbrecht 2006; Huckfeldt and Sprague 1991, 1995; Huckfeldt et al. 1995; Kenny 1992, 1994; Lake and Huckfeldt 1998; McClurg 2003, 2004; Mutz 2002). However, we cannot conclude that a person’s social context is causing him or her to be more civically active with this evidence. One reason is reciprocal causation; an equally plausible explanation for the relationship between talk and participation is that being civically active causes an individual to talk about politics with his or her peers. Another problem is selection bias. Individuals who are more active in civic activities might consciously choose to associate with people who are more interested in talking about politics. Finally, we also need to consider the possibility of endogeneity bias (or, alternatively worded, omitted variable bias). Some factor that we have not been able to be account for could be causing people to both talk about politics and participate in civic activities.

Because of these serious analytical biases, the voluminous political science literature on civic participation has been dominated by theories that focus on individual-level explanations of civic participation. For example, of the thirty-one articles published on civic participation in the American Political Science Review between 2000 and 2009, only four studies directly examined the influence of sociological antecedents.9 Individual-level explanations of civic participation carry more weight in the field of political science because individual-level determinants of behavior are easier to study than social-level factors. Individual-level data are readily available from social surveys such as the American National Election Studies, and standard methods of statistical analysis are well suited to this type of data. In contrast, sociological factors such as civic talk have been relegated to the background of the field because definitive evidence of a causal relationship between social interactions and individual behavior has been hard to come by using existing data sources and methods of analysis.10

Consequently, we are left with an incomplete understanding of participatory democracy.

A Solution: A Quasi-experimental Panel Study

Traditionally, "two-stage” regression models are used to overcome the types of analytical biases described above. In such specifications, the independent variable of interest (in this case, engaging in civic talk) is modeled with instrumental variables that do not correlate with the outcome variable being predicted (in this case, civic participation). This form of analysis is inappropriate for assessing the relationship between political discussion and political participation, however, because it is difficult to identify variables that reliably predict how often one engages in civic talk that are not correlated with one’s level of civic participation.11

If traditional methods for overcoming analytical bias are not an appropriate way to study civic talk, then what is? As illustrated in Table 2.2, one way to get past the biases that have handicapped this line of research would be to conduct an experiment by randomly assigning one group of individuals to be exposed to civic talk (the treatment group) and another group of like individuals not to be exposed to civic talk (the control group). Random assignment to treatment allows us to be confident that the outcomes of the study are actually being caused by civic talk instead of any other observed or unobserved factors.12 Ideally, data on the study population would also be collected over multiple points in time. Panel data further reduce analytical biases if the two phenomena are collected at separated points in time (with talk measured before participation).

But how can we collect data that look like this? A researcher cannot randomly pull people off of the street, force some to engage in civic talk and others not to, and see what happens as these new social networks evolve over time (at least, not very easily). Thus, to execute this research design we need to find a situation that naturally approximates it. Fortunately, such an environment exists: colleges where students are randomly assigned to dormitories.

TABLE 2.2 Overcoming analytical biases associated with the study of civic talk

|

Analytical problem |

Solution |

Explanation |

C-SNIP execution |

|

Selection bias |

Random assignment to peer group |

The individual is no longer able to select his or her peer group. |

Study participants were randomly assigned to their first-year college roommate. |

|

Endogeneity bias |

Any explanation of civic participation that is not accounted for is still orthogonal. | ||

|

Reciprocal causation |

Measure patterns of behavior before and after exposure to civic talk |

Controlling for past patterns of behavior allows causation to be inferred if there is a relationship between past instances of civic talk and current patterns of behavior. |

Patterns of civic participation were measured before and after study participants encountered their new peers at college. |

An example of such an environment is the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Random assignment is incorporated into the university’s housing-assignment process because students are assigned to first-year college dormitory roommates based on a lottery. Incoming first-year dormitory residents rank the sixteen dormitories in order of where they want to live.13 Students are then "randomly sorted by computer” (University of Wisconsin, Madison, Division of University Housing 2004) to determine the order in which they will be assigned to dormitories. If space is available in the student’s first housing choice at the time his or her name is reached in the randomly sorted list, the student is randomly placed in a room in that dormitory. If space is not available, an attempt is made to place the student in his or her second choice of dormitory, and so on.

To gather information on this population, three surveys were administered between 2003 and 2007: the Collegiate Social Network Interaction Project (C-SNIP) Panel Survey. Survey participants initially completed two survey questionnaires: one at the beginning of the 2003-2004 school year, before they were affected by their college roommates, and a second at the end of the school year. During the first wave of the study, students were asked about their patterns of civic participation during high school. During the second wave of the study, students were asked how civically active they were during their first year of college, as well as about their relationship with their randomly assigned roommates. In the spring of 2007, during their fourth year of college, students who had participated in the 2003-2004 C-SNIP surveys were re-interviewed.

Additional Analytical Precision via Data Pre-processing

While the process of assigning C-SNIP participants to dormitory roommates was random, these students were allowed to discuss politics and current events with their roommates as much or as little as they wished. Because of this deviation from random assignment, factors that are out of my control could affect both the treatment (the amount of civic talk to which each student was exposed) and the outcome of interest (civic participation) (Achen 1986; Dunning 2008). For example, students who had been active in voluntary civic organizations before they came to college were more likely to discuss politics and current events with their new roommates (r = .19, p < .01). Prior experience participating in voluntary civic organizations also increased subjects’ likelihood of choosing to participate in such activities during their first year of college (r = .37, p < .01).

A seemingly logical way to address this feature of the data would be to add offending factors such as past patterns of civic participation to the analysis as control variables. Unfortunately, this approach is not a sufficient solution. Including variables in the analysis that are strongly related to both the independent and dependent variables being examined greatly reduces the precision of the analysis (Achen 1986). However, this feature of the C-SNIP study can be accounted for by pre-processing the data with a “matching” procedure (see, e.g., Dunning 2008; Ho et al. 2007a, 2007b, 2007c). Under this procedure, the effect of engaging in civic talk is measured by comparing the civic participation habits of survey respondents who are similar to one another except that one engaged in civic talk and the other did not. By comparing the participatory habits of similar individuals who did and did not engage in civic talk, we can be confident that any observed difference in civic participation between them is unrelated to the factors on which the respondents were matched and, as such, is a consequence of civic talk.14 More detail on how this procedure was conducted is included in Appendix C.

Additional Qualitative Evidence

While survey data allow for systematic study of political phenomena, this form of inquiry is limited by the fact that numbers alone cannot give us a full picture of what actually occurs when peers discuss politics and current events. Richer qualitative data are needed to construct a more holistic picture of how civic talk might influence participatory democracy. Therefore, the quantitative findings presented throughout this book are verified with data collected through a series of focus groups that were conducted with the 2007-2008 first-year class of students at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. This group of students is different from the students examined in the panel survey, which allows me to test the claims I am making with the survey data with another case. However, like the C-SNIP Panel Survey participants, the focus group participants were randomly assigned to their first-year dormitories under the same lottery procedure. Thus, while the qualitative and quantitative data presented in this book come from two separate cases, they are comparable cases.

In total, four focus groups were conducted with eight students in each.15 Students were assigned to one of the four groups based on how civically active they had been in high school ("high” versus "low”) and how much civic talk they engaged in with their randomly assigned roommates ("high” versus "low”). Structuring the focus groups in this way allows me to examine not just whether civic talk causes civic participation, but also how the effect might vary from person to person and from peer group to peer group. For example, individuals with prior experience participating in civic activities may be better able to translate civic talk into civic participation than their less experienced cohorts. This and other related questions are addressed in Chapters 5 and 6.

Case Selection and External Validity

In any scientific study, researchers need to be concerned with how representative their findings are vis-a-vis the case or cases that they have selected to study. The number of cases and the method in which they are selected determine how confident we can be in the results that are generated and in how applicable those results are to the wider world. Keeping this in mind, it is necessary to note that the main sources of evidence presented in this book come from two student populations at one university. Nonetheless, the insights we can gain from these data are of broader import to students of participatory democracy for two reasons: for their internal validity (i.e., the ability to make causal inferences) and because collegiate social networks are a "crucial” case of peer influence (i.e., if we are unable to show causation in this case, we are unlikely to find it in other cases).

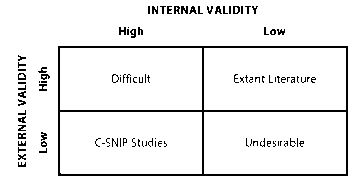

The Tradeoff between Internal and External Validity

Figure 2.2 illustrates a necessary tradeoff that is made in any scientific study. The figure shows a taxonomy of studies classified on two dimensions: external and internal validity. Ideally, we would like our data to be representative of the entire population in which we are interested (externally valid) while simultaneously allowing us to make definitive claims about causation (internally valid). However, this unique mix of strengths is very difficult, if nearly impossible, to create in one study.

Because it is difficult to maximize both internal and external validity, we are left with the choice of maximizing either one or the other. As addressed earlier, by relying on large-scale social surveys the existing literature on civic talk has already maximized external validity. With these data, we can say with certainty that the types of people who engage in civic talk also participate in civic activities. However, with this type of evidence we have been unable to show that civic talk actually causes civic participation. In response to this persistent problem, I used a different approach to gather the evidence presented in this book: increase internal validity to make more definitive causal claims. The quasi-experimental nature of the data presented in this book allows me to make more reliable causal inferences about the relationship between civic talk and civic participation, an undertaking that had not yet been accomplished.

FIGURE 2.2 Comparing analytic strengths and weaknesses

To restate this point using slightly different language: Those who are critical of research on social networks cannot "have it both ways.”14 On one hand, skeptics have observed that while extant data sets on civic talk are representative of the wider public (i.e., high external validity), these data cannot be used to make causal inferences about social influence (i.e., low internal validity). In this we are in agreement; this persistent problem is what is motivated me to write this book. On the other hand, critics cannot dismiss research solely because of lower external validity when a scholar collects data that can be used to assess causation more accurately. As illustrated in Figure 2.2, the tradeoff between internal and external validity is inevitable. Given that the current goal of social network scholars is (or, at least, should be) to show whether a causal relationship exists between civic talk and civic participation, it is necessary to focus our energy on examining internally valid cases. Once causation is (or is not) established in such cases, we can then tackle issues of external validity by examining additional cases to validate, or reject, previous findings.

College Students as a "Crucial" Case of Peer Influence

In addition to increasing internal validity, the case of first-year college students is also an ideal setting in which to study civic talk because it

14 I thank Scott McClurg for this language.

represents a “crucial” case of peer influence.16 College is such a case for two reasons. First, college is a “most likely” case of peer influence (Ger-ring 2001). When a young person leaves his or her family to begin life as an independent adult, peers become highly influential in his or her life (Beck 1977; Campbell et al. 1960). Consequently, we should expect to find evidence of peer effects in this environment. In other words, college is a crucial case to study because if we do not find evidence of a causal relationship between civic talk and civic participation in this environment, we are not likely to find it in other contexts, where peers may be less influential. But if the data presented in this book do show that civic talk has an effect on this collegiate population, we have reason to invest resources in investigating whether this phenomenon occurs in other cases. Possible methods for conducting such further research are discussed in Chapter 8.

In a related vein, a person’s first year of college is also a crucial case because it is a “paradigmatic” case of peer influence (Gerring 2001). A paradigmatic case is one that illustrates the theoretical or conceptual importance of the phenomena being studied. For example, one would not want to study communism without examining the case of the former Soviet Union (Gerring 2001, 219). This case has come to define what communism is and thus is necessary to study when examining that form of governance. In the same vein, collegiate peers define what peer influence is because they are a central facet of the individual’s life as he or she begins adulthood. Moreover, collegiate peers illustrate the importance of peer influence because they are likely to influence the patterns of civic participation that young people carry with them through the rest of their lives. Otherwise stated, and to place this discussion of case selection in a more normative context, steady declines in civic participation over the past half-century have left many wondering whether this dangerous disengagement from public life will continue. If it does, the fate of democracy is in serious peril (Putnam 2000; but see also McDonald and Popkin 2001). Thus, it is incumbent on us to understand how the current generation of young citizens is learning (or not learning) to participate in civic activities. This knowledge will be critically important as scholars and practitioners continue to study and attempt to maintain the strength of civil society.

The questions addressed in this book are not new. Because of the critical need for citizens to be involved in the processes of democratic governance, social scientists have always been interested in studying civic participation. Moreover, there is a growing literature on the influence that civic talk within social networks has on civil society. However, the extant literature has not shown a causal relationship between civic talk and civic participation. For this reason, this line of research has been heavily discounted, and our understanding of civic participation is incomplete because it centers on individual-level antecedents of human behavior. Moreover, the inability to establish causation means that second-order questions, such as which causal mechanisms drive the civic talk effect and whether the effect varies under different circumstances, have been understudied.

In response, what is new and innovative in this study is the way I have chosen to gather my data. By leveraging a situation in nature that approximates an experiment, collecting data over time, making use of data preprocessing, and verifying results from survey data with rich qualitative focus group data, I present results in the following chapters that add to our understanding of how participatory democracy works. In the next chapter, I begin this task with a descriptive examination of civic talk and civic participation. I then show that a causal link exists between these two variables.

Does Civic Talk Cause Civic Participation?

Political discussions with roommates and floormates have allowed

me to see my own political ignorance and have made me want to read [and] learn more about current events.

—C-SNIP Panel Survey respondent

he experience this student had during her first year in college is a

textbook example of what we would see if civic talk has a meaning-

ful effect on how individuals choose to participate in civil society. The student came to college with a given set of characteristics and patterns of behavior. She was then placed into a new social setting in her dormitory, where the interactions she had with her randomly assigned roommate had an influence on how she looked at and participated in civil society. In other words, engaging in civic talk led the student to have what we could call a civic "awakening,” a moment that led her to become more engaged with the processes of democratic governance.

Chapter 2 introduced the concept of civic talk and showed how quasi-experimental panel survey data and rich qualitative focus group data can be used to overcome analytical biases that have remained unresolved in the literature on civic participation. In this chapter, I use these two data sets to test whether the experience described above is the exception or the rule. I begin by describing how civic participation and civic talk are measured. I then test whether these two phenomena are causally related to each other. The results of the analysis show that civic talk leads individuals to participate in civic activities. These data also show that the magnitude and certainty of the civic talk effect varies based on the civic act in question. In short, the evidence shows that civic talk encourages individuals to participate in civic activities, but only in those activities in which they are interested in engaging.

The primary measure of civic talk used in this study is based on the C-SNIP Panel Survey question, "When you talk with your roommate, how often do you discuss politics and current events: often, sometimes, rarely, or never?” Use of self-reports is standard practice in this area of research (see, e.g., Campbell and Wolbrecht 2006; Huckfeldt and Sprague 1991, 1995; Huckfeldt et al. 1995; Kenny 1992, 1994; Lake and Huckfeldt 1998; McClurg 2003, 2004; Mutz 2002). An alternative to relying on students’ self-reports about how much civic talk occurred between roommates, however, would be to use a more exogenous measure: the report supplied by each subject’s roommate. This strategy depends on correctly identifying roommate pairs. Based on the small number of subjects who were willing to report their dormitory addresses, only eight-four roommate pairs could be identified. Unfortunately, this sample is not large enough to conduct a thorough investigation of the relationship between civic talk and civic participation. That said, this small amount of data suggests that the use of self-reports is a valid approach. An analysis of the amount of civic talk reported by these roommate pairs shows that roommates agree on how much civic talk they engaged in during their first year of college (t = -1.14, p = .16). Thus, in this population self-reports of civic talk behavior are likely to be observationally equivalent to an exogenous measure of civic talk.

In line with measurements taken in adult populations (see the "What Is Civic Talk?” section in Chapter 2), civic talk is pervasive but not at the top of everyone’s list of discussion topics in the two C-SNIP study populations. On average, C-SNIP Panel Survey respondents reported that they conversed with their randomly assigned roommates somewhere between "sometimes” and "often” (an average of 2.4 on the 0-3 scale ranging from "never” to "often”). In comparison, when specifically asked how often they engaged in civic talk, C-SNIP respondents reported that they participated in these types of conversations somewhere between "rarely” and "sometimes” (an average of 1.4 on the 0-3 scale ranging from "never” to "often”).

Participants in the C-SNIP Focus Group Study painted a similar picture of how frequently civic talk occurred. When asked to list the topics that they discussed with their roommate, politics and current events were always on the list, although never at the top of the list. Instead, classes and course work, music, television shows, celebrity gossip, sports, plans for the future, and dating were among the various discussion topics that were mentioned sooner and more frequently throughout the course of each of the focus group sessions. In addition, when asked to directly compare how often civic talk occurred relative to the discussion of other topics, the vast majority of the focus group participants reported that they discussed politics and current events with their roommate less frequently than other subjects.

Through further discussion, the focus group participants expressed two reasons for why civic talk is less frequent than other types of conversations. One reason is conflict avoidance: In each of the focus groups, the desire to avoid disagreements or arguments with one’s roommate was a common explanation for why civic talk was infrequent, and sometimes actively avoided. This type of exchange was typical in all four of the focus groups:

PARTICIPANT: I think my roommate has the opposite view that I do. I don’t know, because I don’t really talk to her, but I get that impression. So I figure I will just avoid it just to save time so we don’t fight about it or, like, I don’t know, get in a disagreement.

MODERATOR: That’s interesting. So it’s a way to avoid conflict?

PARTICIPANT: Yeah.

Moreover, the focus group sessions revealed that some students would avoid engaging in civic talk even when they had similar political preferences to their roommates’. As one participant stated:

We’re both pretty liberal. But I still disagree with him a lot, and so, like, every once in a while we’ll talk about it. But it’s different between me and, like, a friend where we can talk about it and, like, not get along and then leave and see each other again, and it wouldn’t be that big of a deal. But if you kind of get in, like, a fight with your roommate, it kind of sucks.

Statements of conflict avoidance like these are not, perhaps, very surprising given that these students had an incentive to maintain positive

Subject Matters and Sources of Civic Talk

Perhaps not surprisingly, the focus groups revealed that civic talk conversations typically occurred in response to current events. A variety of topics were discussed by roommates, including the Iraq war, a student who had recently been murdered near the university campus, the recent election of a student to the City Council, genocide in Darfur, global climate change, and the 2008 presidential primaries. Given that the focus group sessions were conducted in the early spring of 2008, the presidential primaries were the most common topic of conversation. The election was especially in the forefront of conversations between roommates because the State of Wisconsin had just held a presidential primary election on February 19, and each of the major candidates from both parties had held campaign rallies on or near the University of Wisconsin campus. Arguably, the most salient of these events was the large rally held by Barack Obama on February 13, the night of his victories in the "Potomac Primaries” in Virginia, Maryland, and the District of Columbia. The vast majority of the focus group participants reported that they had talked about this rally with their roommates, and many reported having attended (or having attempted to attend) the event.17

relationships with the person they shared small dormitory rooms with for an entire academic year.18

The second most commonly stated reason for why civic talk is not as prevalent as other types of discussions is a lack of interest in politics, either on the part of the individual or on the part of his or her roommate. When directly asked why politics and current events were not frequently discussed, a number of participants in each of the focus groups made statements such as, "My roommate doesn’t like politics,” "It’s almost like a boring topic,” and "Politics usually gets old pretty quickly.” One participant went as far as to say, "My roommate’s more or less mystified by anyone interested in politics.” Another participant summarized his experience by saying, "I asked my roommate once if he was interested in politics or the election or anything, and he said no, so that was the extent of our political conversation.”

Along with highlighting the specific topics discussed when engaging in civic talk, the focus groups revealed two conduits through which politics and current events were brought up during conversations between roommates. One was news media consumption. A majority of the students mentioned that civic talk would occur during normal everyday conversation in relation to what was in the news that day. Statements such as these were common in all of the focus groups:

I would tend to just like read the news on CNN, and so, like, if something pops up usually that I’m opinionated about, then that’s when we starting talking. So it just kind of depends on that.

Well, like, we read the paper, so usually we, like, discuss what’s in the paper.

It usually doesn’t come up unless, like, there’s something [on] TV on it, and then we’re, like, "Oh, that’s kind of interesting,” and then we’ll start talking about it.

The second most often mentioned sources of civic talk were the personal interests and extracurricular activities of individuals and their roommates. Statements such as these were common in each of the focus groups:

We talk a lot more about social issues, too, and like I said before,

[my roommate is], like, a really big environmentalist, so she always has something to say about a candidate and what they think about recycling and stuff like that. So we talk a lot about that.

I always talk about Barack Obama, because I’m a huge fan.

We talk a lot about [health maintenance organizations] and doctors and things because she’s going into med[ical] school now as a doctor, so I think we just relate on it. And we talk because I am really passionate about Darfur in Africa, and so we can talk about that.

TABLE 3.1 Patterns of civic participation during high school and college

|

Mean activity level |

Percentage inactive | |||

|

Civic activities |

High school |

1st year of college |

High school |

1st year of college |

|

Participation in voluntary civic organizations (0-21 point activity scale) |

6.60 |

2.43 |

5 |

35 |

|

Participation in political activities (0-6 point activity scale) |

1.16 |

.56 |

44 |

68 |

|

Voter turnout (2004 presidential primary) (%) |

51 |

49 | ||

Source: C-SNIP Panel Survey.

Note: As is common in studies of voter turnout, the figures are likely inflated. For example, data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey show that in the 2004 presidential election, only 47 percent of citizens between eighteen and twenty-four turned out to vote (Faler 2005).

Measuring Civic Participation

As discussed in Chapter 2, civic participation is a form of activity that pulls an individual out of his or her private life and into civil society. This large set of activities can be broken down into two categories: political civic activity and non-political civic activity. The analyses in this chapter examine three such forms of behavior: voter turnout, participation in other types of political activities, and membership in voluntary civic organizations. A summary of how active students in the C-SNIP Panel Survey were in these activities during high school and their first year of college is presented in Table 3.1.

For the full version of this story, see Zeleny 2008.

However, while the "positive relationship between education and political participation is one of the most reliable results in empirical social science” (Lake and Huckfeldt 1998, 567), the data in Figure 1.1 show that this relationship is not nearly as clear-cut on the aggregate level. As documented by many scholars, citizens’ involvement in civil society has been in decline over the past half-century (see, e.g., Putnam 2000). As an example, Figure 1.1 shows that voter turnout in the United States has been in a steady decline since 1960 (albeit with a recent rebound in the 2000s). However, Figure 1.1 also shows that the American public’s mean level of educational attainment has increased over the same time period. If an individual’s level of education is one of the best predictors of whether he or she will participate in civil society, then why has civic participation declined over time as the level of education in the general public has increased?

In this book I show that, to solve puzzles like this, we need to include social-level variables such as civic talk in our study of participatory democracy. The data I present show how, why, and under what circumstances civic talk causes individuals to participate more actively in civil society. However, to make these findings, a number of analytical pitfalls needed to be overcome.

These figures are taken from wave 9 of the study, collected in September 2009. Responses to this question collected in waves 10 (October 2009) and 11 (November 2009) yield comparable results.

For a detailed discussion of these two methods of soliciting data on civic talk, see Klofstad

et al. 2009.

Or, as Tocqueville (2000, 492) stated it, "Among the laws that rule human societies there is one that seems more precise and clearer than all the others. In order that men remain civilized or become so, the art of associating must be fully developed and perfected among them.”

Of special relevance in this set of citations is Theodore Newcomb’s "Bennington Studies” (Alwin et al. 1991; Newcomb 1943; Newcomb et al. 1967). Like Newcomb, I assess the socializing effect that college life has on young adults.

In reviewing an edited volume dedicated to the study of social networks, one critic even went as far as to say that "few of us really know what to do about implementing rigorous models of complex political interactions with endogenous preferences” (Laver 2005, 934).

This figure was determined by examining articles whose abstracts contained the following keywords: “civic participation,” “political participation,” or “voter.” The search was conducted with the Cambridge Journals online database, available at http://journals.cambridge .org.

A quintessential example of this focus on individual-level characteristics is the Michigan School of political behavior (see, e.g., Campbell et al. 1960). Research in this tradition focuses on partisan identification and other individual-level antecedents and negates the influence of sociological factors (Zuckerman 2004). In fact, the founders of the Michigan School went as far as to say, “By and large we shall consider external conditions as exogenous to our theoretical system” (Campbell et al. 1960, 27).