To train into a good fruit-bearing form

To train into a good fruit-bearing formPruning fruit trees differs from pruning shade trees. Although all trees benefit from a strong framework of branches, fruit trees in particular need well-attached branches that can carry heavy loads of fruit without breaking under the weight. Fruit trees also need air and sunlight to penetrate the branches for best health and fruit set. High humidity can lead to diseases, which you can prevent by removing branches to admit moving air and light into the crown.

Your fruit tree almost always consists of two parts. The roots usually belong to a type of tree that produces low-quality fruit but grows vigorously and is winter-hardy, whereas the grafted top is a named variety like ‘Delicious’. The two are joined because this is the most efficient way to produce large numbers of quality fruit trees. Fruit trees grown from seed seldom resemble the parent tree even slightly, and growing trees from cuttings or layers is a slow and difficult process.

Q Why do fruit trees need pruning?

A Proper pruning can strengthen the structure of a fruit tree, increase its crops, and extend its life. Here are seven more reasons to prune:

To train into a good fruit-bearing form

To train into a good fruit-bearing form

To expose branches to light

To expose branches to light

To encourage good crops of quality fruit

To encourage good crops of quality fruit

To support the weight of those fruits on the limbs

To support the weight of those fruits on the limbs

To manage a tree’s size

To manage a tree’s size

To keep a tree healthy

To keep a tree healthy

To repair a tree that hasn’t been pruned properly or at all

To repair a tree that hasn’t been pruned properly or at all

Q What are the basics I need to know to prune fruit trees?

A Follow these general principles. Also see specific recommendations for different types later in this chapter.

Keep in mind an image of the mature tree as you clip or snip off the buds or tiny twigs. Aim to develop a strong tree with a branch structure sturdy enough to hold up the crop.

Keep in mind an image of the mature tree as you clip or snip off the buds or tiny twigs. Aim to develop a strong tree with a branch structure sturdy enough to hold up the crop.

Prune in accordance with the tree’s natural growth habit.

Prune in accordance with the tree’s natural growth habit.

Thin! Keep the branches sparse enough for fruit to get enough sunlight to ripen. Some trees grow twiggy naturally; certain apple varieties, such as ‘Jonathan’, and many varieties of cherries, plums, peaches, and apricots need additional thinning of their bearing wood to let in sunshine.

Thin! Keep the branches sparse enough for fruit to get enough sunlight to ripen. Some trees grow twiggy naturally; certain apple varieties, such as ‘Jonathan’, and many varieties of cherries, plums, peaches, and apricots need additional thinning of their bearing wood to let in sunshine.

Q Won’t cutting off branches hurt my fruit tree?

A Correct pruning will benefit your fruit tree. To produce good fruit, a tree needs plenty of sunshine, and a fruit tree has a potentially large area to produce fruit: a full-sized, standard apple tree can be well over 30 feet wide and 35 feet high. However, because of its tight branch structure, only 30 percent of an unpruned tree gets enough light and another 40 percent gets only a fair amount of light. As these statistics indicate, when only the top exterior of the tree produces good fruit, you’re getting the use of but one-third of your tree, and all that fruit is grown where it’s most difficult to pick! Even the most careful pruning won’t bring the light efficiency to a full 100 percent, but you can greatly increase it.

Q Can I grow fruit trees as ornamentals in my garden?

A Fruit trees are not usually recommended strictly as ornamentals. Many other flowering trees need less care and have fewer disease and insect problems.

If you want to enhance your yard with a small flowering tree and also want to grow your own fruit, visit an orchard to see whether you like the look of trees pruned for fruit production. Many people like the look of fruit-bearing trees; a commercial orchard in full bloom is a wonderful sight. And fruit-bearing species are a frequent subject for artistic pruning techniques such as espalier.

Many people think a fruit tree doesn’t need much special attention when grown for looks rather than food. This isn’t totally true: all fruit trees need occasional pruning to remain healthy, even if you never eat their produce. If at any time your tree, regardless of its size or age, appears to be setting too many fruits, thin each cluster of small fruits to a single fruit.

SEE ALSO: Espalier, page 179.

Q When is the best time to prune cherry trees?

A The simple answer: If you prune your trees regularly each year, late winter is a good time to prune. But this is a subject of ongoing debate among pomologists — those involved in the science of fruit cultivation. Seasonal conditions vary greatly throughout the country, so your location is an important factor in determining when you should prune. Also, what happens when you prune at different seasons affects the decision of when to prune. For stone fruits such as cherry, apricot, almond, peach, and plum, the best time to prune is very late winter to early spring, or from March to bloom. Pruning earlier makes them vulnerable to infection from a canker disease.

Q Should I prune my pluots and other fruit trees in spring?

A Most people agree that pruning a fruit tree right after it leafs out in spring is one of the worst times. Infections such as fire blight are most active and likely to spread in the spring. The tree will probably bleed heavily, which many people consider unsightly.

If a source suggests pruning in early spring, the author often means late winter — that is, before any sign of growth appears. The only pruning you should do after trees leaf out is to remove branches broken by storms or injured by the cold.

Q Which pruning tasks can I do in early summer?

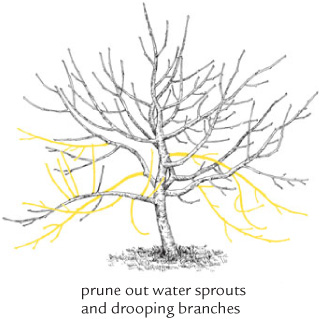

A Avoid major pruning in early summer. Remove suckers, water sprouts, and branches too low on the stem as soon as you notice them.

Fruit trees grown in planters or tubs, espaliers, and other artistically shaped trees need more attention than do other fruit trees. They should be pruned regularly to keep them looking their best. Clip or pinch back new growth on tight hedges, cordons, and fences as soon as they begin to grow, and continue throughout the summer to maintain them in the intended size and shape.

Q Is midsummer pruning good for my pear tree?

A By pruning when new growth is several inches long, you will limit tree growth (unlike dormant pruning, which increases vegetative growth such as water sprouts). Restrict summer pruning to cutting or rubbing off suckers, unless you are following an alternative style of pruning (see the box on the facing page). Finish summer pruning by July 31 to reduce the possibility of winter injury, though exact dates vary by location.

An alternative method for pruning fruit trees replaces the usual late-winter or early-spring work with pruning during the active growth season. For that reason it is sometimes called summer pruning. The Lorette method, developed in Europe by Louis Lorette, is an excellent but complicated system for intensive fruit growing. It is especially useful on dwarf fruit trees and on trees grown as espaliers, cordons, hedges, and fences.

To prevent useless limb growth, begin pruning in early summer and continue until early fall. No dormant pruning is done at all. By frequent clipping and pinching, you direct a tree’s energy into producing fruit buds near the trunk or on a few short limbs, rather than out at the ends of long branches.

This technique is somewhat like shearing a hedge, and results in small, easy-to-care-for trees that bear fruit at an early age. Each part of the tree is in full sunlight because leaf area is limited. Therefore, the fruit is of superior quality.

In cold regions, the Lorette method is risky; trees pruned in summer tend to keep growing later in the season, and this growth may be injured during the winter. For the same reason, even in places where the growing season is long, vigorous-growing trees such as peach and apricot are often difficult to grow by the Lorette system.

Q Is it okay to prune my apricot tree in late summer?

A Yes, depending upon where you live. The best time to prune these trees is July or August, because that’s when disease-causing bacteria are least likely to enter the pruning wounds. In warm areas, prune these trees in July and August. In cold locations, July pruning is better because it gives new growth time to harden off before frost and reduces the chance of winterkill.

In general, some people prefer to prune fruit trees in late summer. By pruning after the tree has completed its yearly growth and hardened its wood, yet before it has lost its leaves, you’ll stimulate less regrowth and fewer water sprouts. You still have to remove dead or diseased branches in late winter, but late-summer pruning works well if extensive winter damage is not likely.

Q Can I prune apple trees in late winter along with my shade trees?

A Wherever growing seasons are short and you expect extreme cold or heavy snow and ice loads to injure your trees, late winter pruning is best. The trees are dormant, and since the leaves are off, it is easy to see where to make the cuts. You can also avoid cutting deeply frozen wood and causing winter damage.

However, if you have neglected your trees for a few years and they are badly in need of a cut-back, avoid doing it all at once. Excessive pruning in late winter stimulates a great deal of upright growth the following spring and summer because a tree tries to replace its lost wood. Branches, suckers, and water sprouts are likely to grow in abundance. If major pruning is necessary, you’re better off spreading out the pruning over a few years. Cut off suckers and water sprouts by midsummer to eliminate that vegetative growth.

Q I’d like to try my hand at growing some fruit trees such as peach, apple, and pear in the backyard. Do I prune them all the same way?

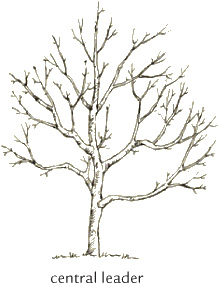

A different pruning styles evolved from the different growth habits and crops of various fruit trees. The canopy of a well-developed cherry or peach tree is naturally vase shaped, whereas pears are pyramidal and apples are pyramidal, rounded, or spreading, depending upon the variety. (Citrus is a special case; see page 222.) The pruning styles build on these shapes, improving branch strength and light penetration for better fruit set. The three main pruning styles are central leader, modified central leader, and open center. Here’s which one to use for which tree:

CENTRAL LEADER. A pyramidal shape; best for dwarf and semi dwarf trees, not standard-sized trees

Apples

Apples

Cherries

Cherries

Pears

Pears

Persimmons

Persimmons

Plums

Plums

MODIFIED CENTRAL LEADER. Best for standard trees; easier alternative to central leader style for dwarf and semidwarf trees

Apples

Apples

Apricots

Apricots

Cherries

Cherries

Pears

Pears

Persimmons

Persimmons

Plums

Plums

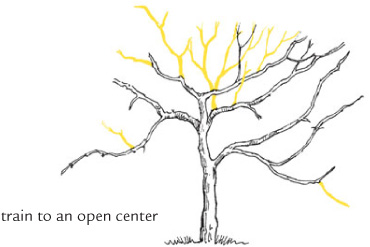

OPEN CENTER (also known as vase or open-top).

Almonds

Almonds

Apricots

Apricots

Cherries

Cherries

Crab apples

Crab apples

Figs

Figs

Nectarines

Nectarines

Peaches

Peaches

Plums

Plums

Quince trees

Quince trees

Q Should I prune my new citrus tree into the same shape that I prune my apple tree?

A No. Citrus trees have strong wood and they bear heavy loads of large fruits without breaking under the weight. They need little or no pruning to let in light; they make fruit in all but the darkest part of the interior. Nor does pruning affect fruit quality. Remove water sprouts and suckers from both young and mature trees, along with dead, diseased, rubbing, and broken wood. You may have to remove the occasional weak branch from little trees. Sometimes the interior of a tangerine tree gets so dark that it stops bearing fruit; it needs a little thinning. That task can be tricky because of the potential for sunscald (bark) and sunburned fruit.

SEE ALSO: Pages 243–244 for sunscald.

Q I want to buy some fruit trees. Should I buy standard trees or dwarf varieties?

A Standard-sized fruit trees can grow 30 to 40 feet or more. A tree that large is difficult to manage and dangerous to work in. Moreover, because so much of it is shaded, it often produces poor fruit. In suburban and urban settings, trees may be deprived of light as buildings, high fences, and other trees crowd them. They respond by growing too tall — and require a lot of drastic pruning later on.

Many fruit trees sold today are dwarf or semidwarf, rather than full-sized trees. Although the tops of these small trees are the same variety and produce the same size fruit as ordinary trees, their special rootstock keeps them from getting large. Dwarf and semidwarf trees vary from about 5 to 12 feet high when fully grown, depending on the kind of rootstock. Dwarf and semidwarf varieties not only save space (most fruits require two trees for pollination) but also reduce the amount of time and effort needed for pruning.

Q I just bought a peach tree at my local nursery. Does it need special pruning at planting time?

A If your new tree comes enclosed in a ball of soil or growing in a pot, no cutback should be necessary except to remove dead or damaged branches and any encircling roots.

Central leader

WHY: With one strong trunk in the center of the tree, well-spaced branches can grow at fairly wide angles and safely bear abundant loads of large fruit.

HOW: Thin branches growing from the central leader as necessary to provide open space between limbs. Thin also some branches coming from these limbs, and so on, to the outermost branches. Remove all small downward branches growing out of bigger limbs. Eventually you’ll need to cut out the top of the tall central leader — that is, once it starts to sag under a load of heavy fruit, forming a canopy over part of the tree and shutting out needed light.

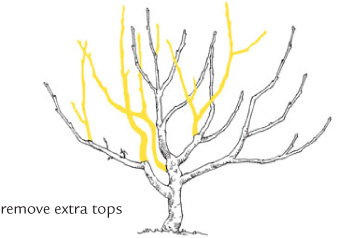

Modified central leader

WHY: This method is easier than central leader because most fruit trees grow this way naturally. It ensures that fruit loads at the treetop are never as heavy as those at the bottom, where limbs are larger. central leader

HOW: The modified-leader method is initially the same as the central-leader method, but over time you let the central trunk branch to form several tops. Reduce the tops of tall-growing trees from time to time to shorten the trees and to let in more light.

Open center

WHY: This method lets more light into the shady interior of a tree. It produces trees with weaker branch structures than the previous methods create.

HOW: Prune so that the limbs forming the vase do not come out of the main trunk close to each other, or they will form a cluster of weak crotches. Even with the whole center of the tree open, you’ll need to thin the branches and remove the older limbs eventually, just as you would with a tree pruned by the central-leader method. modified leader open center

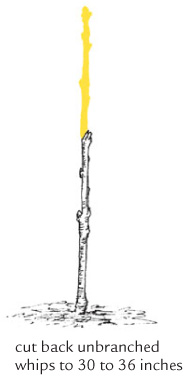

Q I ordered a dwarf apple tree online. Will it need special pruning at planting time?

A Probably not. Mail-order plants are usually sold bare-root for dormant planting, and these are typically top-pruned before shipping. Because bare-root fruit trees may be dug mechanically, they can sustain some root damage in the process. Pruning roots back to healthy tissue helps them heal smoothly.

If you’ve purchased a whip — a young fruit tree with no or weak side branches — plant it, cut it back to 30 to 36 inches high, and cut off any weak branches. Always prune to ¼ inch above a healthy bud.

Most fruit tree failures are due to improper planting rather than not pruning properly at planting time. Don’t neglect the other steps in proper planting:

Soak roots for several hours after arrival

Soak roots for several hours after arrival

Soak ground well after planting

Soak ground well after planting

Plant at the right depth, keeping the bud union 2 to 3 inches above ground

Plant at the right depth, keeping the bud union 2 to 3 inches above ground

Water regularly throughout the first year

Water regularly throughout the first year

Q Do I need to stake a newly planted fruit tree?

A Most trees won’t need staking, but if your tree will grow on an open, windy site, set a 5- to 10-foot stake 2 feet in the ground roughly 4 inches from the trunk on the south side of the tree. Loosely tie the tree above the first set of branches to the stake with twine or flexible plastic tape.

Q I just planted two bare-root dwarf pears and two bare-root semidwarf apples. How do I start to train them?

A Pruning a new, bare-root fruit tree to have sturdy branches that can bear the weight of fruit begins in its first year. Apple and pear trees are initially pruned to a central leader (although that may change with age). After the tree starts growing, choose the strongest shoot to train as the leader or trunk. Pinch off competing shoots right below it, and choose four equally placed scaffolds about 6 to 8 inches apart. Because wide branch angles are important to tree strength and productivity, start training narrow branch angles by spreading with clothespins attached to the trunk above the shoot. Keep low limbs until tree is more established.

Q Do I have to keep training a semidwarf apple tree after the first year?

A Yes. In your tree’s second year, keep widening narrow crotches. Snip off branches 18 inches or less from the ground. In early spring, encourage a strong leader by pruning out or cutting back vertical shoots competing with the leader. Cut back the leader by about one-third to force a second, higher layer of scaffold branches to emerge. Thin out some of the side branches (laterals) and shorten scaffolds, creating a sturdy structure for the tree. Lower scaffolds should be longer than upper ones. Keep limbs evenly spaced around the tree and at regular vertical intervals on the trunk, making sure that no two limbs emerge at the same height or place. If you were a bird flying over the tree, it would look like a wheel with the leader at the hub and eight spokelike, crooked branches around it.

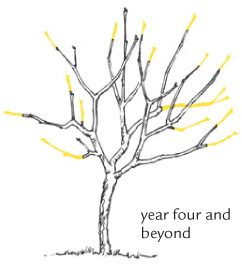

Q I’ve been training my pears to a central leader for the past two years. Is there much training left to do?

A In the third year, prune off competing leaders. Pruning branches before bearing spurs are established delays fruiting. Remove water sprouts — vertical shoots from limbs — and suckers, especially those growing below the bud union, to keep up the tree’s energy. For a third level of scaffold branches, head back the leader another time. Also take off all fruit on the leader.

In year four and beyond, continue removing side shoots that compete with the leader. Train a young, healthy central-leader fruit tree to have branches smaller on the tree top and wider on the bottom so maximum sunlight reaches them. Take off scaffold branches that grow too big and start to shade out the limbs below.

Q What are spur-type fruit trees? How do I prune them?

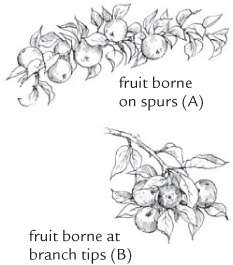

A Trees bear their fruit either on the main limbs or on short, stubby branches called spurs, which grow off the limbs. Pears, plums, and cherries grow mostly on spurs (A). Peaches are borne on one-year-old limb growth and pomegranates at the tips of new growth (B). Most varieties of apples are produced on both spurs and on limbs.

Because spur-type fruit trees grow more slowly, they need less pruning. Because this means considerably less labor for the orchardist, scientists have bred trees that produce mostly on spurs, and many varieties are now available.

When too many fruit spurs develop along a branch, cut out some of them to encourage bigger and better fruits on the rest. This helps to reduce the amount of thinning you need to do each year. After a few years of experience, you’ll be able to judge about how many spurs are right for your tree. Each spur usually produces for several years, after which time you should remove it so a replacement can grow. You’ll be able to spot the older spurs because they get long and look spindly.

Q My new plum tree is not supposed to grow very big. Why do I have to prune it?

A Since plums and cherries are apt to grow into a bushy form no matter what you do, early shaping is important mainly to keep them from getting too wide — and to prevent the branches from growing too close to the ground.

Q Our ‘Red Delicious’ apple tree has upright branches. Last year it looked weighed down by the fruit crop. Is it too late to shape the tree?

A Apples, pears, and peaches produce much heavier fruit loads than do plums and cherries. When growing apples and pears, you’ll find that some need more shaping than others. Many apples, such as ‘Wealthy’ and ‘McIntosh’, seem to grow into a good shape quite naturally. Others, like ‘Red Delicious’ and ‘Yellow Transparent’, tend to grow very upright, forcing lots of tops with bad crotches. Prune upright-growing trees to get rid of weak crotches that are likely to break under a heavy load of fruit.

Q How do I prune a dwarf Asian pear tree?

A Dwarf trees require some pruning just as full-sized trees do, but their height needs no control. Moreover, since they grow more slowly, they need pruning less often. You may want to thin some fruit to encourage trees to produce larger ones. Miniature fruit trees grown in tubs or planters for ornamental purposes also need some snipping back during the summer to keep them attractive.

Q I live in northern New England, where there’s a ton of snow. Does that affect how I prune fruit trees?

A If you live in an area where snows are heavy and the average accumulation is around 3 feet, or if the snow drifts that high around the trees, eliminate branches near the ground. Heavy ice crusts sometimes settle as the snow underneath melts, breaking lower limbs in the process. This causes ugly wounds in a tree’s trunk. Dwarf fruit trees may not be the best choice for you, because their branches are mostly low-growing.

Q I recently planted a five-in-one apple tree. What’s the best way to prune it?

A As a novelty, some nurseries sell three-in-one or five-in-one apple trees, and a few even feature specimens with plums, cherries, peaches, nectarines, and apricots all growing on the same tree. Though they may be useful for a small growing area, these multiple-variety fruit trees are difficult to prune. If you have one, follow these tips:

Mark the varieties. You will have to remember each year where the different varieties are located, or else you may cut off the only limb bearing a certain kind of fruit. If you don’t have a good memory, tie ribbons of various colors to identify each one.

Mark the varieties. You will have to remember each year where the different varieties are located, or else you may cut off the only limb bearing a certain kind of fruit. If you don’t have a good memory, tie ribbons of various colors to identify each one.

Grow your multiple-fruit tree with an open center (see page 225), since there will be at least three strong limbs. Each kind of limb will grow at its own rate and in a different manner, so you’ll need to do corrective pruning to produce a well-balanced tree. It’s a big job. Keep at it to avoid bad crotches, water sprouts, and lopsided growth.

Grow your multiple-fruit tree with an open center (see page 225), since there will be at least three strong limbs. Each kind of limb will grow at its own rate and in a different manner, so you’ll need to do corrective pruning to produce a well-balanced tree. It’s a big job. Keep at it to avoid bad crotches, water sprouts, and lopsided growth.

Be careful not to inadvertently remove branches you want to keep. Take your time when pruning and examine the whole branch before making a cut. Unless you pay close attention to the task at hand, it’s easy to prune off a grafted variety.

Be careful not to inadvertently remove branches you want to keep. Take your time when pruning and examine the whole branch before making a cut. Unless you pay close attention to the task at hand, it’s easy to prune off a grafted variety.

Q How should I prune my Damson plum tree to keep it healthy?

A Even a young tree occasionally needs to be pruned because of some mishap. Limbs break, tent caterpillars build nests, and branches die. As the tree gets older, rot and winter injury may take their toll on its branches.

Annual pruning makes fruit trees produce healthy new wood. This ongoing rejuvenation is vital to a tree’s health, especially when your goal is to produce good crops of high-quality fruit over a number of years. Without this pruning, many trees that produce handsome specimens while they are young or middle-aged often bear only small, poor fruits as they grow older. By removing excess branches and letting sunlight penetrate the crown, you encourage the tree to bring forth large red apples or big crops of juicy plums or peaches.

Q The apricot trees I planted a few years ago are now bearing fruit. How do I prune them to keep them producing well?

A As with cars, regular tune-ups keep fruit trees going strong. You’ll get the best results when you prune on an annual basis rather than as an occasional event.

Remove dead and damaged wood. Clip or saw off the injured part back to a live limb or the trunk. Sick limbs will speed the decline of the tree.

Remove dead and damaged wood. Clip or saw off the injured part back to a live limb or the trunk. Sick limbs will speed the decline of the tree.

Remove branches to thin out and open up the tree to enable sunshine to reach and ripen the fruit. Thinning allows air to circulate, which discourages disease, and makes it easier for birds to pick up preying insects.

Remove branches to thin out and open up the tree to enable sunshine to reach and ripen the fruit. Thinning allows air to circulate, which discourages disease, and makes it easier for birds to pick up preying insects.

Remove a couple of the oldest limbs. If you do this annually, the whole bearing surface can be renewed every six or eight years, which is like getting a whole new tree. In addition, this will minimize the need to do any drastic pruning of large, heavy limbs, and the tree will suffer less.

Remove a couple of the oldest limbs. If you do this annually, the whole bearing surface can be renewed every six or eight years, which is like getting a whole new tree. In addition, this will minimize the need to do any drastic pruning of large, heavy limbs, and the tree will suffer less.

Cut off crossed branches and any that might rub and cause wounds in the bark.

Cut off crossed branches and any that might rub and cause wounds in the bark.

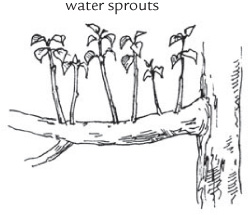

Remove water sprouts promptly. These are upright, vigorous-growing branches that appear in clumps, often from a large pruning wound. They cause unwanted shade and are usually unproductive. (The more a branch tilts toward horizontal, the more fruit it bears.)

Remove water sprouts promptly. These are upright, vigorous-growing branches that appear in clumps, often from a large pruning wound. They cause unwanted shade and are usually unproductive. (The more a branch tilts toward horizontal, the more fruit it bears.)

Remove surplus fruits when your tree sets too many (see Thinning Fruit, below).

Remove surplus fruits when your tree sets too many (see Thinning Fruit, below).

Q My fruit trees produce mostly puny fruits. What’s wrong?

A You need to thin the fruits before they mature. Thinning does for fruit what disbudding does for flowers. Because the remaining fruits grow bigger and better, you’ll end up with more bushels of usable fruit than if you hadn’t thinned at all. Most commercial growers thin their fruit in order to get the large specimens you see in stores.

Together with proper pruning, thinning helps your tree not only to produce larger fruit, but also to produce annually. Many fruit trees have a tendency to set a large crop every other year, and some produce well only every third year. The production of too many fruits (and therefore seeds) taxes a tree’s strength. When a tree bears too many fruits in any one year, it often bears few, if any, the following year.

Q When should I thin the fruits on my trees?

A The best time to thin is after the natural fruit drop in early summer. Keep an eye on your trees, and whenever you see a lot of little fruits on the ground, give nature a helping hand by thinning the fruit still on the tree. Don’t wait too long! Go out and remove excess fruits early in the season, while they’re still tiny, so the tree doesn’t invest its energy in them.

Thinning is good for a plant and good for you because it improves the size and quality of the remaining fruit. Remember that each variety of fruit has a built-in size limit, however, and no amount of disbudding or thinning will produce a fruit larger than that limit.

Thinning is usually less practical on trees with lots of small fruits, such as cherries, and most bush fruits, such as blueberries. On those, you can get some of the same benefit from pruning.

These fruits will benefit the most from thinning:

Apples

Apples

Apricots

Apricots

Nectarines

Nectarines

Peaches

Peaches

Pears

Pears

Plums

Plums

Q How much fruit should I remove when thinning a fruit tree?

A If there are more than two fruits in a cluster, leave the biggest and best one and pick off all the rest. Ideally leave about 6 inches between each fruit. Since this involves picking off 80 to 90 percent of the fruits, it’s a big job.

Even a light thinning will improve your crop. (Try leaving one branch alone to see what a difference thinning makes.) Regular pruning cuts down on the number of fruits produced, and therefore the time you need to spend thinning.

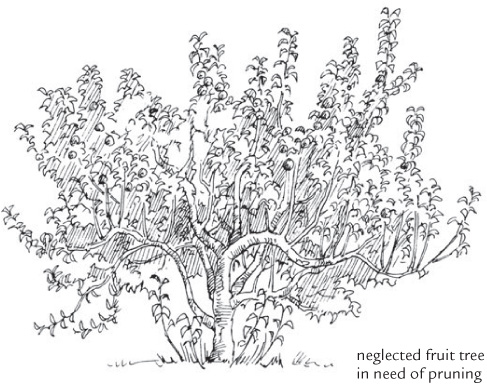

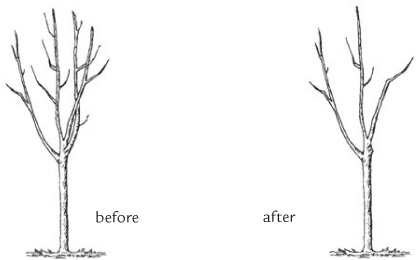

Q We inherited some fruit trees that don’t look very good. Is it too late to fix them?

A Corrective pruning can often come to the rescue of badly pruned trees. Below are some typical situations:

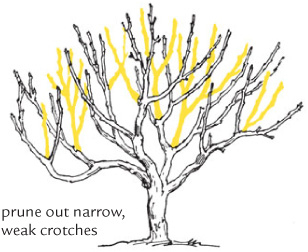

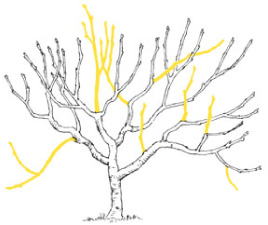

PROBLEM. The tree has a weak (narrow) crotch. It will collect water, begin to rot, and eventually split or break off at this point.

SOLUTION. Cut out one of the forks. The result will be a crooked leader, but that is a big improvement nevertheless, and later the crook will straighten out considerably.

PROBLEM. The tree has several tops.

SOLUTION. Prune back to a single top. You may remove any remaining side branches later as the top grows taller.

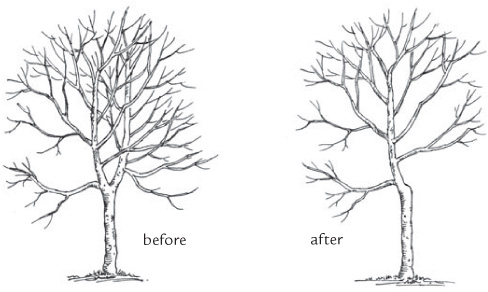

PROBLEM. The tree is tangled with growth.

SOLUTION. Simply removing all unnecessary growth may make a world of difference. Cut out dead, rubbing, and downward branches, branches that compete with each other, and those that have strayed too far from the rest of the tree.

Q Our tree bore fruit soon after planting. Then it stopped. What happened?

A The time required by a young fruit tree to begin bearing is generally from 2 to 12 years, depending on the kind of fruit, the variety, the rootstock, and your growing conditions. When you buy a fruit tree, ask the nursery when you should safely expect the tree to bear. Don’t let a tree bear fruit when it is too slight and immature. That weakens it, and it won’t bear again for many years. It’s difficult to say exactly when a tree is strong enough to bear its first crop; evaluate the strength of the limbs, the height, and its general health.

If you fear your tree is too small to mature fruits without weakening it, pick off the first blooms or small fruits. For example, if a semidwarf fruit tree blooms its second year, remove flowers before they can develop.

Q I have a fruit tree that has never produced fruit. What’s wrong?

A Sometimes instead of bearing early in life, a tree does just the opposite. Some varieties, such as the ‘Baldwin’ apple and certain pears, take a long time to produce; others, in spite of careful pruning, are growing so luxuriously that they forget to settle down and bear fruit. Delayed bearing can result from root crowding or from weeds, lawn, and suckers growing around the base and sapping a tree’s energy. Nonfruiting can also result from overly rich soil or not enough sunlight reaching the branches.

Try root pruning (see page 68) to slow down tree growth, which may get the tree to produce.

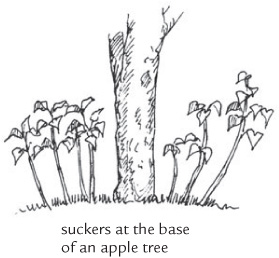

Q What are all the spindly branches growing from the base of my apple tree? What should I do about them?

A These are suckers, fast-growing shoots that are usually vertical and erect. They tend to appear as a cluster of branches close to the base of a tree trunk, but sometimes (especially on plums and cherries) they pop up from the roots anywhere under a tree, even a distance away from the trunk. Mow or clip them off at ground level as soon as they appear, while they’re still on the small side and succulent.

Q What causes suckers?

A A lot of sucker growth occurs on fruit trees when a slower-growing variety is grafted onto a vigorous- growing rootstock.

Q What’s the difference between water sprouts and root suckers?

A Water sprouts emerge from branches; root suckers emerge from the ground.

Q What if I don’t remove suckers and water sprouts?

A If they appear from below the graft, they’ll grow into a wild tree or bush that will crowd out the good part of the tree within a few years. They will also sap valuable energy from the tree.

Q Can I transplant suckers?

A Because suckers look like new, young trees, it’s tempting to think you can transplant them to form a new fruit tree of the same variety. But such trees usually produce fruit of inferior quality because they have come from the root-stock rather than the named variety.

Q Can I incorporate into my orchard seedlings that appear on the ground?

A In some unmowed orchards, trees sprout and grow from seeds of unused fruits that fall on the ground. Treat them like suckers and remove them as soon as they begin to grow. Like any weed, they sap energy from the orchard by depleting the water and fertility of the soil — and eventually they crowd out the good trees.

Although seedlings can often resemble the named varieties, their appearance is deceptive, and almost always the fruit is of inferior quality. Don’t allow them, or any other weed, to compete with the vast root system your trees need to support the large crops of fruit you’re anticipating.

Q What is sunscald?

A Sunscald is the most common type of winter injury to fruit trees. You’ll recognize it if you see bark that looks sunken, discolored, or blistered and has small cracks or even large slits that run up and down the tree on the south or southwest side of the trunk.

A Sunscald is traditionally considered a winter problem caused by a fast rise and fall in temperature. Affected cells on the trunk’s southwest side break dormancy as direct sun heats the trunk. Frigid night temperatures kill the awakened cells. Sunscald can take place in any climate when bright, warm sun shines directly on a young tree’s bark. It is especially hard on trees with little foliage to shade them. Particularly vulnerable are dark, thin-barked, moisture-stressed young trees that are either badly pruned or improperly planted, or suffered from root damage during transplanting. Freezing and thawing can also cause the trunk to expand and contract, cracking bark in the process.

Q What can I do to treat sunscald?

A With a clean, sharp knife, cut away dead bark to healthy tissue as soon as you see it. Let the opening heal without painting or treating it.

Q Can I prevent sunscald?

A Orchardists sometimes spray a thinned white latex paint on tree trunks every two or three years to reflect winter sun. This helps keep the tree sap cool. Whitewashing the tree stems is also useful in the South, where excessive sun often blisters the bark during hot summers. In areas where winter sunscald is predominant, you can also cover the trunk from the base to just above the bottom limbs with crepe-paper tree wrap. Do this in mid-fall and remove it right after the last frost in spring. Repeat this process each fall until the bark thickens, usually two or more years, depending upon the tree.

Q I pruned my fruit tree late last summer. Some new growth didn’t survive winter. What happened?

A Sometimes a tree doesn’t stop growing soon enough in late summer to harden up its new growth, which can’t withstand the first cold spell or the extreme cold of winter. Or untimely late-winter thaws may stimulate bud activity, and the trees lose moisture that the frozen roots can’t replace. The result is winterkill.

Q How can I keep winterkill from happening?

A Cut out damaged wood early in the spring. If the winter damage is severe, a heavy pruning of damaged wood will probably be all that the tree can stand, so don’t do any additional pruning that year. (When this happens, don’t fertilize for a year to prevent overstimulation of growth in an already weak tree.)

Sometimes it is difficult to tell which limbs are really dead and which are merely slow about leafing out. If in doubt, postpone the pruning for a few weeks, just to be sure.

In addition, follow these tips to reduce winterkill:

Choose varieties that are suitable for growing in your region (that is, hardy in your USDA hardiness zone).

Choose varieties that are suitable for growing in your region (that is, hardy in your USDA hardiness zone).

Prune carefully and at the right time.

Prune carefully and at the right time.

Fertilize only in spring and early summer, so you don’t stimulate late growth.

Fertilize only in spring and early summer, so you don’t stimulate late growth.

Before winter arrives, cover tree roots with a heavy mulch of hay, shredded bark, or leaves so the ground doesn’t freeze deep or warm up suddenly. This mulch will help to prevent root injury and also keep the tree from running out of moisture.

Before winter arrives, cover tree roots with a heavy mulch of hay, shredded bark, or leaves so the ground doesn’t freeze deep or warm up suddenly. This mulch will help to prevent root injury and also keep the tree from running out of moisture.

Q I neglected my small orchard for a while, and some of the trees are now excessively tall. What can I do?

A Ideally, you should prune regularly so that trees won’t get too tall in the first place. At this point, however, you’d do well to remove some trees, though cutting down healthy trees just because you or someone else planted too many is a traumatic experience. Still, thinning the number of too-big trees is often the only way to achieve a good orchard.

When it comes to downsizing individual specimens, it’s possible to improve the framework of a too-tall tree but it will take several years to accomplish. During that time you could plant a new dwarf or semidwarf apple tree that would begin to bear fruit in its third year.

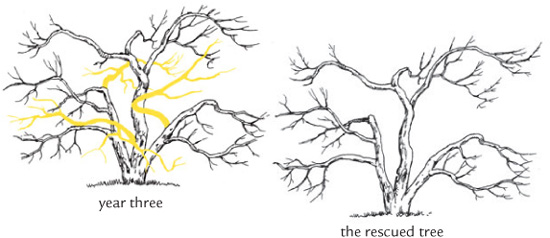

Q How should I prune an ancient fruit tree that I really want to save?

A There is usually no way to get a sprawling, crotchy old tree back to growing with a model central leader without serious shock to the tree, and you can’t top tall ones safely if they are past their prime. Usually, opening up a tree’s center and thinning the wood for light and air are the only pruning you can hope to do on an elderly tree.

Q Can we salvage a decrepit orchard on our farm?

A Many folks ask the same question when faced with an old tree or orchard. Sometimes it is better to clear the land, stack up a big woodpile, and start over — but not always. Before you decide to try to save an old orchard, answer these two questions honestly:

Are the trees too far gone? If their trunks are full of rot and large holes, or if they’re half dead and splitting apart, they’re probably on their last legs, and any pruning might finish them off.

Are the trees too far gone? If their trunks are full of rot and large holes, or if they’re half dead and splitting apart, they’re probably on their last legs, and any pruning might finish them off.

Is the fruit that the trees produce any good? If it is green, hard, sour, and small, the trees are probably of a poor variety. Perhaps they grew as suckers from the roots of other trees now gone, or from seeds that grew out of fallen, unused fruit. Unless the fruit is worth cooking or making into cider, it’s just as well to get rid of such trees.

Is the fruit that the trees produce any good? If it is green, hard, sour, and small, the trees are probably of a poor variety. Perhaps they grew as suckers from the roots of other trees now gone, or from seeds that grew out of fallen, unused fruit. Unless the fruit is worth cooking or making into cider, it’s just as well to get rid of such trees.

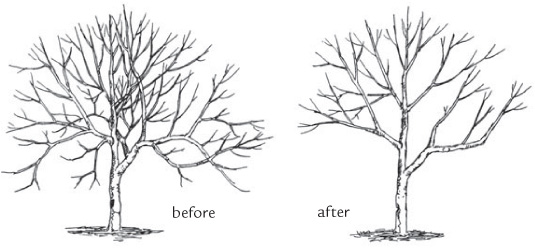

Q How can I get a neglected orchard back in shape?

A If the trees look sound and the fruit looks like it could be improved with thinning, fertilizing, and pruning, then clean up the orchard and prune the trees. You can do this over the course of several years. If the trees are not in desperate condition, or if they respond well to the initial pruning, you may accelerate the process.

Here’s what you do for starters:

With saw and scythe, remove brush and weeds, trees other than fruit trees, and fruit trees that look decrepit or produce worthless fruit.

With saw and scythe, remove brush and weeds, trees other than fruit trees, and fruit trees that look decrepit or produce worthless fruit.

Remove loose bark on remaining good trees, being careful not to open new wounds.

Remove loose bark on remaining good trees, being careful not to open new wounds.

Cut off dead limbs and broken branches, cutting each back to the branch collar without leaving a stub. Follow directions for cutting large branches (see page 63) so that the wood doesn’t split back into the trunk.

Cut off dead limbs and broken branches, cutting each back to the branch collar without leaving a stub. Follow directions for cutting large branches (see page 63) so that the wood doesn’t split back into the trunk.

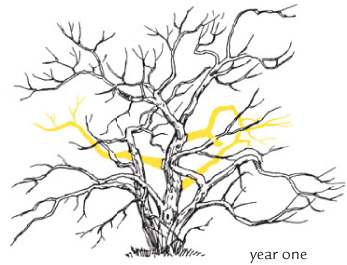

On trees that need severe pruning, cut out limbs with woodpecker holes, weather damage, or signs of insect or disease infestation. That’s enough for the first year. On trees requiring little pruning, begin removal of smaller limbs around the top of the tree to let in light. Don’t cut too many live limbs in any year, unless their weight threatens the tree.

On trees that need severe pruning, cut out limbs with woodpecker holes, weather damage, or signs of insect or disease infestation. That’s enough for the first year. On trees requiring little pruning, begin removal of smaller limbs around the top of the tree to let in light. Don’t cut too many live limbs in any year, unless their weight threatens the tree.

Haul away debris — wood, bark, and brush — so insects and disease won’t reproduce in it.

Haul away debris — wood, bark, and brush — so insects and disease won’t reproduce in it.

Q What do I do after the first year?

A The following year, begin light pruning at the top of each tree so that more sunlight can reach the interior. Remove no more than one-quarter of a tree’s limb area at one time. Less is better. Also cut out a few older, medium-sized, weak, and unproductive branches.

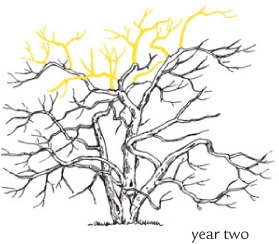

The third year, thin out the branches even more. Start removing some larger branches to renew the tree. From then on, prune normally. If a tree appears to be in good physical condition, with many lower limbs and adequate new growth, begin to shorten the top. Your orchard, thanks to careful pruning, should now look better and begin producing a tasty crop.

Pruning tools can transmit serious diseases unless you keep them clean. For example, fire blight — a bacterium-caused disease that’s lethal to fruit trees, especially pears — is spread around an orchard through tools.

If you suspect disease, think of yourself as a tree doctor when you prune. You wouldn’t expect a surgeon to take out your gallbladder with the same dirty instruments she used to remove her last patient’s appendix. Your tree deserves careful treatment with disinfected tools.

Disinfect your tools after pruning each tree. For home gardeners, it is safe and effective to soak the tools in a pail containing a household disinfectant such as Lysol or rubbing alcohol as you go between branches or trees. Just dip shears and saws into solution and wipe off the excess before making the next cut. With these germ-free tools, you can approach your trees with a clear conscience and do them no harm.

Q I grow several kinds of apple trees that vary somewhat in shape. Do I prune them all the same?

A To prune apple trees, follow the general directions in How to Shape Fruit Trees, page 224. Keep the tree growing with a central leader, if possible, and correct any bad growth habits common for your variety of tree.

Different apple varieties have somewhat different growth habits, so observe your tree and try to work with its natural tendencies. For example, ‘McIntosh’ is a nearly ideal tree, a strong, spreading grower with a naturally sturdy form. ‘Red Delicious’, on the other hand, will form many weak crotches if left alone; it is a dense grower, so you will need to thin out more branches. ‘Cortland’ has a spreading, somewhat drooping growth habit; don’t allow branching too close to the ground. Prune ‘Jonathan’ heavily to correct its twiggy habit of growth. Some apples such as ‘Empire’ bear mostly on short spurs, so be careful not to damage these when pruning.

Q What’s the best way to prune a cherry tree?

A Cherry trees (Prunus cerasus, P. avium) need less pruning than do other fruit trees.

Start pruning to a central leader when your tree is young to encourage a strong tree, especially if it is one of the larger-growing types. Because of the tree’s natural habit of growth, you will probably have to change to a modified leader or open center as it gets older.

Start pruning to a central leader when your tree is young to encourage a strong tree, especially if it is one of the larger-growing types. Because of the tree’s natural habit of growth, you will probably have to change to a modified leader or open center as it gets older.

You’ll need to do some moderate pruning to let in sun to color the fruit, and to thin out the bearing wood.

You’ll need to do some moderate pruning to let in sun to color the fruit, and to thin out the bearing wood.

Beware of overpruning, which can lead to winter injury and premature aging.

Beware of overpruning, which can lead to winter injury and premature aging.

SEE ALSO: How to Shape Fruit Trees, pages 224–225.

Q Any tips on pruning citrus trees?

A Because oranges, grapefruits, lemons, and limes (Citrus spp.) grow in the hottest parts of the United States, they usually need less pruning than do fruit trees grown in the North, where pruning is needed to let sunlight into the trees. Over time, they develop a domed canopy. The wood is strong, and most trees produce crops inside the shaded crown. Remove water sprouts, suckers, and dead, broken, and diseased branches. If fruits stop forming inside the crown of an older tree, remove some interior branches for better light penetration. You can train citrus trees into fancy shapes, such as espaliers, cordons, and fences, if you do it with care. Dwarf varieties are usually best, and they can also be grown in large pots or planters.

Q The crown of my dwarf kumquat tree looks unbalanced. How and when can I prune it to look better?

A Sometimes citrus trees grow unevenly. If that bothers you, prune back the overlong limbs to a healthy, out-facing bud or branch. You can do this at any time of year, but in areas where frost is likely, wait until all danger of frost is past in the spring. Dwarf citrus need a lot less pruning than standard trees do.

Q How do I prune an old ‘Meyer’ lemon tree?

A Both dwarf and full-sized citrus trees may lose their vigor as they get older, so a rejuvenation pruning may be necessary to help them bear well again. Citrus trees can stand a more rigorous cutback than can peaches or apples, because winter injury is rarely a problem.

If you cut back a tree severely, clip and train new branches so the tree grows back into a good shape. It will probably take at least two years before it begins to bear well again. The hot summer sun can easily blister tender citrus bark, so be sure to whitewash any bark that you suddenly expose to the sun through heavy pruning. Also whitewash any bark exposed because of winter injury.

Q When and how do I prune a fig tree?

A Prune figs (Ficus carica) during their dormant season, cutting off dead and damaged wood. Figs grow from 10 to 30 feet tall and can stand heavy pruning, but once shaped, they really shouldn’t need much pruning. Shrub thinning will cut back the early fruit crop but increase the main (second) crop, which occurs on new wood. Figs make good espaliers.

White and brown figs bloom and bear only on new wood, so the usual practice is to cut these back severely each year for better production.

White and brown figs bloom and bear only on new wood, so the usual practice is to cut these back severely each year for better production.

Prune black figs more like other fruits, by cutting back wood that is over a year old.

Prune black figs more like other fruits, by cutting back wood that is over a year old.

Root pruning is sometimes necessary to promote fruiting if they are growing in overfertile soil — in fact, fig trees do better where the soil isn’t too rich.

Root pruning is sometimes necessary to promote fruiting if they are growing in overfertile soil — in fact, fig trees do better where the soil isn’t too rich.

Q How should I prune my peach and nectarine trees?

A The peach (Prunus persica) has always represented a real challenge to dedicated gardeners. It is fussy about soils and climate, sensitive to spring frosts, and grows so vigorously that heavy pruning is needed. Yet the juicy, tasty peach is so enticing that even Northerners keep trying to grow it. Those fortunate enough to live where the peach grows well naturally want to grow it to perfection. Proper pruning plays an important role in peach culture, and an unpruned tree is a sorry sight, bearing fruit only at the ends of saggy branches.

Grow both the peach and the nectarine with an open center.

Grow both the peach and the nectarine with an open center.

The trees tend to grow fast and late in the season, and pruning makes them grow even faster. In areas where winter damage often kills improperly hardened wood, root pruning may be the only effective way to check excessive limb growth late in the season.

The trees tend to grow fast and late in the season, and pruning makes them grow even faster. In areas where winter damage often kills improperly hardened wood, root pruning may be the only effective way to check excessive limb growth late in the season.

Don’t allow peach and nectarine trees to branch close to the ground, or you won’t be able to keep trunk borers under control.

Don’t allow peach and nectarine trees to branch close to the ground, or you won’t be able to keep trunk borers under control.

Even if you faithfully prune and thin, peach trees tend to set such a heavy crop that broken branches are a danger. Help your tree by propping up weighty limbs with wide planks. y p

Even if you faithfully prune and thin, peach trees tend to set such a heavy crop that broken branches are a danger. Help your tree by propping up weighty limbs with wide planks. y p

Q When’s a good time to prune my peach tree?

A The best time to prune is on a dry day in late winter, so you can cut away wood injured by low temperatures. In years when winter damage is heavy, this pruning may be all the tree can stand. Otherwise, because fruiting occurs on one-year wood only, you can remove older wood. Never feed a tree after you’ve had heavy winter damage or pruned it severely; you don’t want to stimulate rapid regrowth.

Like all fruit trees, peaches often set far too many little fruits — even when pruned well. To get large, luscious peaches, thin after normal fruit drop in early summer, spacing 6 or 7 inches apart. This may be tedious and time-consuming, but the results will be well worth your effort.

Q My nectarine tree is so tall that it’s hard to harvest the fruit. Will I hurt the tree if I cut it back?

A Peach, nectarine, and apricot trees are likely to grow tall. Since the best fruit often grows at the top of the tree, keep the top low and accessible. The best method is to cut back the tall-growing limbs each year. If you haven’t done this regularly, you can remove the top of the tree during the dormant season with no trauma to the tree. However, the fruit crop may be less the following year.

Q How do I prune apricot trees?

A Treat apricots (Prunus armeniaca) like peaches. Train to an open center. Prune heavily for the best crops and so the tree will bear annually. Remove branches to let sunlight reach the spurs, in order to produce good fruit. Spurs bear for about four years and need to be removed thereafter.

Some growers prefer to prune in summer because it results in less-vigorous regrowth. In some climates, it can also save the tree from the ill effects of pruning on wet winter days, when many disease fungi are active. Where the growing season is short, root pruning may help prevent excessive growth without subsequent winter injury.

Q I’d like to plant some pear trees. Are they difficult to grow?

A Pears (Pyrus communis) are not as difficult to grow as are peaches, but in past years fire blight killed off many trees. Fortunately for pear lovers, quite a few blight-resistant varieties have been introduced. An annual light pruning is better than an infrequent heavy one; heavy pruning delays bearing and encourages fire blight.

Like most fruits, pears need a partner for pollination, so always plant at least two varieties. Consider ‘Moonglow’ and ‘Starking Delicious’, which will pollinate each other and flourish in most pear-growing areas.

Q How do I prune my pear tree?

A Follow these tips:

The early training of pears is similar to that of apples. Prune to a central leader for the first few years. After that, grow them with a modified leader, if you’d like.

The early training of pears is similar to that of apples. Prune to a central leader for the first few years. After that, grow them with a modified leader, if you’d like.

The growth of most varieties tends to be upright, so direct early pruning toward thinning excess branches and encouraging a spreading tree.

The growth of most varieties tends to be upright, so direct early pruning toward thinning excess branches and encouraging a spreading tree.

Many pear varieties grow with several tops, so prune out extra tops to keep a strong central leader and to avoid narrow crotches that tend to break easily when loaded with fruit.

Many pear varieties grow with several tops, so prune out extra tops to keep a strong central leader and to avoid narrow crotches that tend to break easily when loaded with fruit.

Pears bloom and bear on the short, sharp spurs that grow between the branches. Spurs need regular thinning; occasionally remove older ones so vigorous young ones can replace them. Thin out the small fruits after the normal fruit drop in early summer.

Pears bloom and bear on the short, sharp spurs that grow between the branches. Spurs need regular thinning; occasionally remove older ones so vigorous young ones can replace them. Thin out the small fruits after the normal fruit drop in early summer.

A Fire blight is a contagious bacterial disease affecting pears, quince, apples, crab apples, and other members of the rose family. You can spot it easily because the limbs, leaves, and twigs look as if they have been held over a flame. Cut diseased limbs completely back into good, healthy wood. Remove them to a safe distance and burn, bury, or otherwise destroy them, so the disease doesn’t spread. Sterilize your gloves and all tools in bleach solution after pruning each tree.

Always be on guard for signs of fire blight. Early detection is important so that you can bring it quickly under control.

Q How do I pick a plum tree for my garden?

A No matter where you live, there’s a plum tree (Prunus spp.) for you. Choose one suited to your climate and desired color — red, blue, yellow, purple, and green plums are available in a wide range of sizes and flavors. Some are self-fruitful; others require two varieties for pollination. European varieties (P. domestica), some hardy up to –50°F, are best for cold climates with late frosts; Japanese plums (P. salicina) thrive in warmer zones. Little wild European plums (P. insititia) such as Mirabelles and damsons are another option, along with American plum (P. americana), a thorny shrub or small tree hardy to USDA Zone 3.

One-year-old whips, from 4 to 7 feet tall, are the best choice if you are planting European or American plums, and two-year-old, slightly branched trees are preferable if you are planting the Japanese varieties. Cut back the whips by about one-third to a fat bud.

Q How do I prune an established plum tree?

A Prune your plum tree carefully to help it produce well and to allow the sun to ripen the fruit before the first frost hits. Due to the scraggly habit of growth, plums are best grown with an open center. Thin out water sprouts and inside branches to allow sun penetration and to keep up fruit production inside the tree.

Q When should I prune my plum?

A It depends on the type of plum you’re growing:

Japanese plums are vigorous and require a lot of pruning, which you should do annually in late winter.

Japanese plums are vigorous and require a lot of pruning, which you should do annually in late winter.

European plums need very little; an occasional thinning of older wood is usually all that is necessary.

European plums need very little; an occasional thinning of older wood is usually all that is necessary.

Most American plums and their hybrids need only moderate pruning to keep them bearing well. Some varieties, including some of the cherry–plum hybrids, grow very long branches that hang on the ground; these should be shortened.

Most American plums and their hybrids need only moderate pruning to keep them bearing well. Some varieties, including some of the cherry–plum hybrids, grow very long branches that hang on the ground; these should be shortened.

Many plum roots sucker badly, so periodically remove suckers unless you mow under the tree regularly.

Many plum roots sucker badly, so periodically remove suckers unless you mow under the tree regularly.

Q Since plum fruits are relatively small, do I still need to thin the crop?

A Trees that produce large plums, such as the Japanese varieties, benefit from thinning. For best results, pick off the extra fruits when they are still tiny, in early summer, so that the remaining plums are 5 inches apart.

Q My plum tree bears huge crops every other year. Why won’t it fruit every year?

A If your plum tree fruits heavily every other year, thin out some fruit to limit the crop, increase fruit size, and encourage annual bearing.

Q Do I need to worry about diseases with plums?

A Some plums, especially European varieties, are quite susceptible to a disease called black knot. Thick outgrowths form along the twigs and are particularly noticeable in winter. No spray is available to control black knot, so prune out all diseased material in winter, cutting 6 to 8 inches below a knot. Disinfect tools as you work. Burn or dispose of diseased parts promptly to prevent spreading the trouble. It’s a good idea to remove infected wild plums or cherries growing nearby.

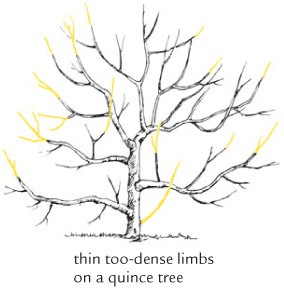

Q I just planted a quince tree for making jelly. Do I have to prune it?

A Quince (Cydonia oblonga, not flowering quince, Chaenomeles) is one of the few fruit trees that need almost no pruning, except to remove any broken, dead, diseased, injured, or crossed branches. Shape to get the tree growing into a good form; remove low branches that could touch the ground if weighed down by heavy fruits. Thin out limbs only if harvesting the fruit is difficult.

Like pears, quince trees are extremely susceptible to fire blight (see page 260).

Q How do I grow tropical and semitropical fruits?

A Only gardeners in completely frost-free regions can safely grow tropical fruits outdoors. Elsewhere, you can grow them in a heated greenhouse or a conservatory.

A Grafting is not a mysterious operation, and almost any good fruit-growing book or website will show you how it’s done. Basically, you take a branch from a tree that bears good fruit and surgically transplant it to the root of a wild or unimproved tree. Bud grafting is similar except that you use a single dormant bud. Grafting is useful to create varieties that nurseries don’t sell, and to propagate choice old varieties that are nearly obsolete.