Ankylosaurs lived at a time when the largest land predators in Earth’s history including T. rex roamed the landscape, dismembering other dinosaurs with powerful jaws and serrated teeth. In an arms race, some plant-eaters developed defensive weaponry. “A tail club was definitely an effective weapon and could have broken the ankle of a predator,” said paleontologist Victoria Arbour of North Carolina State University and the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, who led the study published this week in the Journal of Anatomy. “But in living animals today, weapons are also often used for battling members of your own species—consider the horns of bighorn sheep or the antlers of deer—so perhaps ankylosaurs did something similar.”

—WILL DUNHAM, KING OF CLUBS: INTRIGUING TALE OF THE “TANK” DINOSAUR’S TAIL

THE ARMORED DINOSAURS

In the summer of 1906, American Museum paleontologists Barnum Brown and Peter Kaisen were in the badlands of the Upper Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation, near Gilbert Creek, in central Montana. The temperatures were in the scorching range, over 40°C (104°F) most of the day, and the heat reflected off the light-colored rock, making it even more unbearable. There is no water anywhere, so each of the scientists had to carry water or die of dehydration, and they carried food and water for their horses as well. They had been working the Hell Creek for several years, and previous field seasons had produced the specimens of Tyrannosaurus rex that had generated great publicity for the American Museum (see chapter 14). Day after day they continued their search. They saw plenty of fossils of broken turtle shells and armor of crocodilians (not worth collecting), and the distinctive parallelogram-shaped scales of garfish. Particularly common were the small, finger-shaped cylinders of rock that represented ossified tendons from the tails of duckbills. Dinosaur bone fragments were also common, but if loose on the ground and not very diagnostic, they were not worth picking up. However, if a few of them were together and not too broken, experienced collectors such as Brown and Kaisen knew to follow the trail of bone fragments like Hansel’s breadcrumbs to see if the rest of the bone was eroding out of the slopes above. Sometimes they found nothing, but occasionally they got lucky.

On one particular summer day in 1906, Kaisen followed a trail of bone scraps and found a partial skeleton eroding out of the cliff (figure 21.1). He poked around to determine how much was there, then hiked back and brought Brown to see it. Soon they were both digging carefully around it, exposing the top and sides but leaving the specimen embedded in the soft siltstones to support it as they dug. The specimen just kept getting bigger and bigger, and going farther and farther into the cliff face. As they dug, they left each large bone on a pedestal of soft siltstone, giving it minimal support. Brown probably used a bit of dynamite to blow away the overburden, a risky practice that is rarely used today. After days of hard work, they had the fossil exposed and surrounded in a hard plaster jacket, ready to move. They pried the blocks off their pedestals, added a plaster jacket to the newly exposed bottom surface, and then brought the horse and buckboard wagon to the site to load each block and transport it to the nearest rail line. Eventually, all of the huge blocks were on their way to New York.

Figure 21.1

The Hell Creek badlands of central Montana, where Brown and Kaisen found the first Ankylosaurus specimen (just above the pick). (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Once back at the American Museum, Kaisen began to prepare the specimen, cutting away the plaster jacket and then carefully cleaning off the rock and siltstone that still encased the fossil bone. After two years, the specimen was clean enough for Brown to publish a description. The specimen consisted of the skull, a few teeth, the shoulder girdle, a few vertebrae from the shoulders, back and tail, ribs, and the dense bony pieces of armor called osteoderms. The rest of the creature was unknown, so Brown reconstructed the limb proportions to match those of stegosaurs, with long hind limbs and an arched back. (Ankylosaurs were considered stegosaurs for a long time.) Brown’s reconstruction (figure 21.2) made the creature look more like a stegosaur with the arched back and was criticized by Samuel Wendell Williston as being based on too little material for a reliable reconstruction. Instead, Williston thought Ankylosaurus should be reconstructed with a straight back and equal length forelimbs and hind limbs, as Baron Franz Nopcsa had done with Polacanthus a few years earlier. Williston also thought that Brown’s dinosaur might be the same as Stegopelta, which Williston had named years earlier.

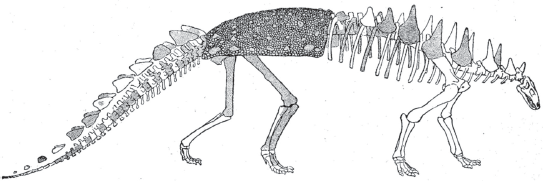

Figure 21.2

Barnum Brown’s 1908 reconstruction of the first Ankylosaurus specimen, with the hind legs too long so it has high hips and a back like a stegosaur. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Brown gave it the name Ankylosaurus magniventris. Ankylos literally means “bent” or “crooked” in Greek, and it is the root word for the medical condition called “ankylosis” in which joints are fused and stiff. Brown probably was thinking not of the original meaning but of the idea of “fused” armor plates. Today the meaning of the genus is usually translated as “fused lizard” or “stiff lizard” rather than “bent” or “crooked” lizard. The species name magniventris means “broad belly,” which refers to the large flat shell on the back and the flat belly below.

It turned out that Brown had collected parts of this animal before. In 1900, while collecting a Tyrannosaurus rex in the Upper Cretaceous Lance Creek beds of eastern Wyoming, Brown had found about 77 of the bony osteoderms, but both Brown and Osborn thought they might belong to Tyrannosaurus. In fact, the dense, bony osteoderms were durable fossils that looked and weathered like small cannonballs, and they had been found many times by Native Americans in the past.

In 1910 Brown was on another American Museum expedition, working in the Late Cretaceous of the Red Deer River badlands in Alberta (see chapter 22). Collecting in the Scollard Formation, he found a much more complete specimen of Ankylosaurus, with a skull, jaws, ribs, vertebrae, limbs, armor, and the first and only specimen with the tail club preserved. This is the amazing specimen now on display in the American Museum. Together these specimens gave the most complete image of the kind of dinosaurs ankylosaurs were. In addition, the discovery of Euoplocephalus further improved our understanding of ankylosaurs (figure 21.3).

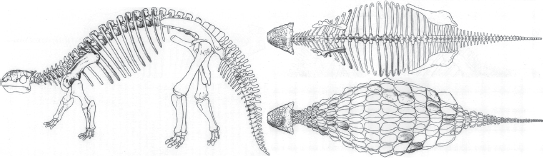

Figure 21.3

Skeleton of the ankylosaur Euoplocephalus. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Their image became iconic when the American Museum mount led to life-sized sculptures, such as that created for the 1964 World’s Fair in New York (figure 21.4). The turtle-like reconstruction of Ankylosaurus painted by artist Rudolph Zallinger for the famous 1947 mural The Age of Reptiles (still on the walls of the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale) has been the template for nearly every book and reconstruction since then. We know the groups as the ankylosaurs, and all the mystery fossils found earlier but poorly preserved and understood began to fit into an image.

Figure 21.4

Life-sized sculpture of Ankylosaurus displayed at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Ankylosaurus turns out to be a relatively rare dinosaur, with only a handful of specimens found in more than a century, and most of them are fragmentary. Only three skulls are known (figure 21.5), but it was widespread in Upper Cretaceous rocks all over the Rocky Mountains, including the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, Lance and Ferris formations of Wyoming, and Scolland and Frenchman formations of Alberta (but not in New Mexico Upper Cretaceous rocks). The largest known specimens were about 10 meters (33 feet) long, 1.5 meters (5 feet) wide, although several were only 6 meters (20 feet) long; they weighed from 4.8 metric tonnes (5.2 tons) up to 8 metric tonnes (9 tons). The head was covered with thick plates of armor on top, along with a pair of pyramid-shaped horn-like plates in the back corners of the skull pointing up and back, and their nostrils faced sideways (figure 21.5). The lower jaw was small and the bite force was also weak, with tiny leaf-shaped teeth similar to those of stegosaurs, so it could only eat low vegetation such as shrubs and small bushes. Ankylosaurus had large sinuses and nasal chambers, possibly for water and heat balance or for sound amplification. Rings of bone covered the neck and protected it between the armored head and back. It is most famous for its semisolid shell of fused osteoderms on the back, composed of a “pavement” of small polygonal osteoderms, alternating with longitudinal and transverse rows of big osteoderms. Ankylosaur legs were relatively short and equal in length, so it did not have the high hips of stegosaurs and was built very low to the ground. The vertebrae of the back and hips were strongly fused together and partially fused to the shell above them. The tail vertebrae were highly flexible, so it could swing its tail club easily. All in all, Ankylosaurus had formidable defenses. It was capable of rapid maneuvering to keep predators like T. rex at bay, and it could bring its body around to break the shins of the predator with the bone-crushing club on its tail.

Figure 21.5

The best of the three known skulls of Ankylosaurus, showing the distinctive head armor, small eyes, weak lower jaws with small teeth, and pyramid-shaped horns on the back corners of the skull roof. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

More than two dozen genera of the family Ankylosauridae are now known, and most were described in the past 30 years. They were restricted to the Cretaceous of North America and Asia, and they never appeared in Gondwana continents. They first appeared in the Early Cretaceous with fossils like Gastonia and Cedarpelta from the Lower Cretaceous Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah and Liaoningosaurus and Chuanqilong from the Early Cretaceous of China. Most of the ankylosaurids come from the Late Cretaceous, when they apparently pushed out the nodosaurids that had dominated the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous. One of the most interesting is Crichtonpelta, a middle Cretaceous ankylosaurid from China that was named in honor of Michael Crichton, the author of the Jurassic Park novels. Another nearly complete skeleton from the Hell Creek Formation was described by Victoria Arbour and David Evans in 2017 and given the name Zuul after the evil demi-god and Gatekeeper in the 1984 movie Ghostbusters (in the movie the character Zuul had a head shaped like this dinosaur).

“MR. BONES”

Barnum Brown was one of the greatest fossil collectors who ever lived, and he probably found more famous dinosaurs than anyone in his time or before (figure 21.6). A short list of these includes theropods Albertosaurus, Struthiomimus, Dromaeosaurus, and Tyrannosaurus rex; ankylosaurs Ankylosaurus, Euoplocephalus, and Edmontonia; duckbills Corythosaurus, Kritosaurus, Hypacrosaurus, Saurolophus, Prosaurolophus, and Parasaurolophus; many ceratopsians including Chasmosaurus, Leptoceratops, Centrosaurus; and, of course, Triceratops; and many Morrison sauropods. Even though most people haven’t heard of him today, he is considered a giant in the field. As Dingus and Norell wrote:

Among paleontologists, Barnum Brown is almost universally recognized as the greatest fossil collector of all time, and although his name is no longer widely recognized among the general public, the name of the most famous dinosaur he ever discovered—Tyrannosaurus rex—most certainly is. The fossils he unearthed across continents from the Americas to Asia vastly expanded our knowledge not only of the evolution of dinosaurs but also of most major groups of reptiles and mammals. Crucial to his success was a penchant for eccentricity and risk, both professionally and personally. His expeditions, many of which he undertook with little or no backup, even from his trusted companions, led him to several of our planet’s most remote and dangerous regions. As if that weren’t risky enough, Brown often used his guise as a bone digger to cover a second, clandestine role as an American intelligence agent, gathering strategic geologic and geographic data that would aid both the country’s exploration for oil and the government’s war efforts.

Figure 21.6

Barnum Brown: (A) class picture in the 1897 University of Kansas yearbook, showing the young college grad about to embark on a great career finding fossils; (B) a young apprentice Barnum Brown (left) and Henry Fairfield Osborn (right) at Como Bluff in 1897, excavating the first Diplodocus for the American Museum; (C) Brown in his later years, coating a fossil with a protective plaster and burlap jacket; (D) Brown (right) in 1941, with Erich M. Schlaikjer, and Roland T. Bird with the reconstructed skull of the gigantic Cretaceous crocodilian Deinosuchus from the Big Bend of Texas. Bird holds the skull of a modern Nile crocodile for scale. ([A, C] Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; [B] image #17808, [D] image #318634, courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History Library)

Brown’s career started modestly. Born in Carbondale, Kansas, on the anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s and Charles Darwin’s birthday (February 12, 1873), he was named after the famous showman and circus founder, P. T. Barnum. However, no one could foresee the amazing show that Brown’s fossil discoveries would eventually become. As Gil Troy wrote:

The parental impasse over what to name the young lad ended after a few days when P. T. Barnum’s dazzling circus visited. “There must be something in a name,” Brown, who had his own genius for self-promotion would say “for I have always been in the business of running a fossil menagerie.”

His family lived on top the Carboniferous coal beds of eastern Kansas. His father not only maintained a ranch but spent much of the Civil War running supplies in a wagon from the railheads in Kansas to remote outposts all over the Plains. He also had a small-scale strip mining operation for coal on his land, which was much cheaper to collect locally than to ship via rail and wagons from remote coal mines. As the workers stripped away the rock over the coal seams, they found incredibly fossiliferous limestones, as well as beautiful fossil ferns and other plants in the coal itself. Brown wrote in his notebook: “They unearthed vast numbers and—varieties of seashells, crinoid stems and parts, corals…and other sea organisms…. I followed the plows and scrapers, and obtained such a large collection that it filled all of the bureau drawers and boxes until one could scarcely move. Finally Mother compelled me to move the collection into the laundry house.”

His love of fossils then led him to enroll at the University of Kansas where he studied paleontology under Samuel Wendell Williston, as well as learning the geology of his state and of coal and other fossil fuels such as oil (figure 21.6A). Williston wrote that Brown was “the best man in the field that I ever had. He is very energetic, has great powers of endurance, walking thirty miles a day without fatigue, is very methodical in all his habits, and thoroughly honest.” During summer breaks in the mid-1890s, he went on university trips to the badlands of South Dakota and the plains of Wyoming, where he discovered his aptitude for strenuous fieldwork and fossil collecting. In 1896, he was hired as part of a field crew for the American Museum working in the San Juan Basin of New Mexico and the Bighorn Basin of Wyoming. He was such a talented collector that he was hired right away, even though he had not yet graduated from the University of Kansas. (He finally got his degree 10 years later.) In 1897, he was an apprentice collector in the American Museum crew in Medicine Bow, Wyoming, where they found Morrison dinosaurs in abundance (figure 21.6B). As the 24-year-old Brown wrote in his notes, “I was…fortunate in discovering a partial skeleton of…Diplodocus. This was the first dinosaur excavated by any American Museum expedition, and here I introduced the use of plaster of Paris in excavating fossils.” Soon he was sent anywhere the American Museum needed a hardy, sharp-eyed, self-sufficient field collector. As Dingus and Norell wrote:

On a December morning in 1898, a 25-year-old paleontologist named Barnum Brown trudged through the snow-choked streets of New York City for what he thought would be a routine day at the American Museum of Natural History. But before he could remove his hat, his supervisor, Henry Fairfield Osborn, anxiously summoned him. “Brown,” he said, “I want you to go to Patagonia today with the Princeton expedition…to represent the American Museum. The boat leaves at 11; will you go?” “This is short notice,” Brown replied. “But I’ll be on that boat if…I [can] go home to pack my personal belongings and arrange for my absence.” Although he had never been out of the country before, Brown did not return for almost a year and a half. In Patagonia he prospected for fossils largely on his own. On one excursion, he was shipwrecked off the Patagonian coast when a large wave slammed his small cutter; despite not knowing how to swim, Brown floated safely to shore grasping a barrel. By befriending the locals, he got his project back on track and eventually shipped 4.5 tons of fossil mammal bones back to the museum. Brown’s gamble—to strike out by himself to search for fossils in a foreign land—established a precedent for his expeditions and launched his legendary career.

After his Patagonia trip, Brown spent nearly every field season for the next decade in the Hell Creek beds of Montana, where he found T. rex, Ankylosaurus, and many other dinosaurs already discussed. Between 1910 and 1915, he worked in the Red Deer River badlands of Alberta (see chapter 22), where he discovered Late Cretaceous dinosaur fossils from 70 to 75 million years ago, older than the latest Cretaceous Hell Creek fossils. In Canada, he competed with the Sternberg family, who were hired by the Royal Ontario Museum to collect their native fossils—but Brown brought back amazing specimens that are now on display or in storage at the American Museum. He finished working in Canada in 1916, then went to Cuba in 1918, and back to the Rockies in 1918 and 1919.

When travel restrictions ended after World War I, he went abroad and added to the American Museum’s collections from many regions, including fossils from Ethiopia and Egypt in 1920–1921, Miocene mammals from India (and part of what became Pakistan) and Burma from 1922–1923, and Miocene mammals from the Greek island of Samos in 1923 and 1924. Although he did a lot of collecting on Samos by himself, he took advantage of the low costs of labor (thanks to the refugees of the Turkish war with Greece) to hire a team of 18 men and 6 women to haul dirt in baskets for “the attractive sum of 35 drachmas (70 cents) per day for men and 20 drachmas per day for the girls.” When the work was done, he had 56 cases of beautiful bones, “representing three species of three-toed horses, rhinoceroses…many species of antelope and gazelle…birds, and a variety of carnivorous mammals,” including the short-necked giraffe named Samotherium.

From 1931 to 1935, he took part in excavating a huge Morrison bone bed at Howe Ranch in Wyoming. In the late 1930s, Brown and American Museum assistant Roland T. Bird (with a crew of CCC workers) excavated some huge trackways from the legendary track site at Glen Rose, Texas. Later he collected the skull of the enormous crocodilian Deinosuchus in the Big Bend region of Texas (figure 21.6D). He also spent much of the Depression years of the 1930s driving to, exploring, and collecting from important American fossil beds, such as the Early Permian of Texas, the Petrified Forest of Arizona, and elsewhere. The American Museum was bursting at the seams with too many crates of dinosaurs, and they needed other kinds of fossils to round out their collections. Also, funds for expensive foreign travel were scarce during the Depression when even the rich people who once funded their expeditions had lost money in the Stock Market Crash of 1929.

Brown was legendary for his fieldwork and collecting prowess, but his personal life was a bit more complicated. He was a real ladies’ man, famous for his affairs with ranchers’ daughters while he was in the field and seducing foreign ladies during his travels abroad. I vividly remember my first summer in the field with my graduate advisor Malcolm McKenna of the American Museum in 1977, who had met Brown in his old age. Malcolm had also visited many of Brown’s old localities, and more than once heard the stories of Brown’s romantic exploits from the local ranch ladies, who would tell him how they still remembered Barnum Brown—and not for his paleontology. As Dingus and Norell document in their biography of Brown, he often stayed abroad for many months during periods when his New York lawyer was settling lawsuits of jilted lovers, and he had to hastily exit some foreign countries for the same reason.

As Gil Troy wrote:

Someone that obsessed, who charmed New York’s elite, effete Upper West Siders when he returned from his remote, sun-baked dry beds yielding ancient mysteries under layers of rock and dirt, was bound to be complicated. His first wife died of scarlet fever shortly after childbirth. The distraught Brown left their daughter to be raised by her grandparents. Brown remarried but, even in those more discrete times, was known as a cad. His second wife Lilian Brown got the last laugh, with a passive-aggressive, neglected-wife-of-a-workaholic memoir: I Married a Dinosaur.

Brown’s later career was documented by Lowell Dingus and Mark Norell in their excellent biography of him, and by his second wife Lilian McLaughlin Brown (nicknamed “Pixie” by Barnum Brown), who wrote amusing books documenting their travails and triumphs. Her first was I Married a Dinosaur in 1950, about their fieldwork in the Siwalik Hills of India (now part of Pakistan) and side trips to Burma. Her other books included Cleopatra Slept Here in 1951, about Barnum’s collecting in Ethiopia and Egypt, and Bring ’Em Back Petrified in 1956, about their fieldwork in Guatemala excavating Ice Age mammals from the bottoms of rivers.

As Dingus and Norell wrote:

The peripatetic Brown collected so many specimens on his travels that even today dozens of large boxes of his fossils have yet to be opened. Crates labeled “mammals from Samos” and “ornithomimid from Hell Creek” rest on sanitized racks in the storerooms of the American Museum of Natural History simply because there are not enough staff workers to unpack them, remove the plaster, and prepare them all. As Brown neared his 90th birthday in 1963, his successor at the museum, Edwin Colbert, marveled at how much of the museum was Brown’s single-handed work: “There are, in our Tyrannosaur Hall, 36 North American dinosaurs on display…. You collected 27, an unsurpassed achievement.” For all of Brown’s success as a collector, his direct impact as a scientist was strangely modest, compromised by his time abroad and by his laxity in publishing his discoveries. The CV that he compiled for his memoirs—which he never finished—shows that there were only five years between 1897 and his retirement in 1942 in which he did not participate in a major expedition. Yet he penned few scientific papers, and those that he did publish are mostly short notes. On the other hand, his longer publications, like his monograph on Protoceratops, a Mongolian relative of the great horned dinosaurs, are classics, both for the freshness of the presentation and the quality of the analysis.

Brown was such a prolific collector and spent so little time writing up his discoveries that many finds were left to others. For example, in the 1930s he was working on the Crow Reservation in Canada and found a partial skeleton of a small, agile carnivorous dinosaur. He began to write up a scientific paper describing its bird-like characteristics and even gave it a tentative name (the drawer is labeled “Daptosaurus”), but he never finished or published that project. Brown would eventually show the specimens and discuss the project with one of Colbert’s students at the American Museum, John Ostrom. This got Ostrom thinking about making his own discovery of the same bird-like dinosaur that he named Deinonychus (see chapter 16). Eventually, Ostrom combined his own finds on his Yale expeditions with the Brown American Museum specimens. Brown never got credit for being the first to find Deinonychus because he never finished or published his work.

Brown was a hard-working collector for the American Museum, but he had many commitments on the side, which Dingus and Norell described:

Brown’s succession of exotic discoveries made him one of the greatest scientific celebrities of his day. The public nicknamed him “Mr. Bones,” and one writer noted that “wherever Brown went on his expeditions in the American West…he was feted by the local populace. Droves of people would meet his train and vie for the honor of driving him from the station to town.” Museum archives reveal that Brown’s zest for geologic exploration inspired a second, clandestine life. From early on Brown’s expeditions for fossils had served as a smoke screen for occasional sojourns as an intelligence agent and corporate spy. During both world wars he funneled geologic knowledge gleaned from his fossil-hunting expeditions to the United States government. He occasionally confided in museum colleagues, as in a 1921 letter to paleontologist W. D. Matthew stating that he had “an exciting time in Turkey, and secured much desired data for the State Department.”

In 1941 the American government contacted museums to find out where their curators had done fieldwork in order to harvest information about remote and strategically vital areas. Although Brown was about to retire, he happily obliged, citing his travels to Canada, Cuba, Mexico, Patagonia, France, England, Turkey, Greece, Ethiopia, Egypt, Somalia, Arabia, India, and Burma…. Because of his passion for both geology and paleontology, Brown also forged close ties with oil and mining companies. Part of the industry’s appeal was financial; he charged a consulting fee of $50 per day, almost $800 in today’s currency. These contacts could also be lucrative sources of fossil-hunting cash. In 1934, with museum funds for fieldwork in short supply, Brown approached officials of the Sinclair Oil Corporation in search of financial support. The company’s president became so enamored of Brown and his work that he personally backed Brown’s expedition to northern Wyoming, where he discovered the famous Jurassic dinosaur graveyard named Howe Quarry. To this day the Sinclair logo features an image of Diplodocus in deference to this partnership.

Brown’s oil company contacts were extensive. In 1920 he quite likely fled a jilted lover’s lawsuit by skedaddling for Abyssinia (now Ethiopia) under the banner of the Anglo American Oil Company, an offshoot of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil. His mentor, Henry Osborn, was supportive of such ventures because Brown kept his keen eyes peeled for fossils while prospecting for oil. In this way Osborn reaped the fruits of Brown’s labors while the oil company paid for them. Brown’s letters—in which he invariably addresses his supervisor as “my dear Professor Osborn”—maintain the careful guise of an eccentric fossil hunter, but they also contain carefully worded notes about both oil prospects and the activities of European diplomats, military personnel, and businessmen. Those notes also contain telling details about his targets’ wives and daughters.

Barnum Brown officially retired from the American Museum in 1942 at age 69. During the war years of 1942–1945, he used his extensive knowledge of world geology to help the Office of Strategic Services (predecessor of the CIA), giving them strategic information about geology and natural resources and helping plan military strategy. He spent the late 1940s and 1950s, when he was in his 70s and early 80s, in semiretirement. He still came in to the American Museum to finish projects when he felt like it, helped supervise mounting of his specimens, and participated in occasional field expeditions as his energy and funds allowed. He mostly worked on consulting jobs for oil companies, as well as advising the people who were preparing dinosaur exhibits for the 1964 World’s Fair in New York (see figure 21.4).

Barnum Brown died in 1963 at the ripe old age of 89. As Dingus and Norell wrote, “First and foremost he was the greatest dinosaur collector the world has ever known. Through Brown’s efforts, dinosaurs gained a strong foothold in the psyche of both the scientific community and the general public.” As Colbert noted above, Brown collected 24 of the 37 dinosaurs that were once in the Cretaceous Hall in the American Museum (57 of his specimens are currently on display in all the American Museum halls), so his finds were the public face of dinosaur paleontology for almost a century. He was as public a celebrity as any paleontologist was in those days, with weekly radio broadcasts, articles in newspapers, and many public appearances. Brown was also the main consultant on Walt Disney’s pioneering movie Fantasia, in which the dinosaurs and their world are animated to Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. This animation of dinosaurs was inspiring and iconic for many generations of future paleontologists (including me). As Dingus and Norell wrote: “Brown’s real legacy lies with his discoveries themselves, which still serve as a foundation for numerous geologic and biological research projects in paleontology.”

Ankylosaurus itself is one of the more extreme examples of the ankylosaur family, with a relatively solid shell of armor, horns on its head, a tail club, and spikes along the edge of its shell. A number of ankylosaurs had been found prior to its discovery, but these fragmentary specimens gave little or no reliable indication of what they would have looked like in life. These represent the other main group of ankylosaurs, called nodosaurs. They did not have a tail club, and the armor in the skin of their backs and sides were made of numerous smaller unfused osteoderms rather than the solid bony shell of Ankylosaurus, Gastonia, Crichtonpelta, Pinacosaurus, or Euoplocephalus. Given how fragmentary most of the early specimens were, it is not surprising that no one was able to reconstruct them accurately until nearly complete articulated specimens were finally found. Today at least two dozen genera of nodosaurs are known, and they are found on almost every continent, including Antarctica. Yet most amateur dinosaur enthusiasts do not recognize a nodosaur, nor can they guess that it is a kind of ankylosaur.

The very first ankylosaur to be discovered (long before Ankylosaurus in 1906) was Hylaeosaurus, from the Lower Cretaceous Wealden beds of southeastern England. It was only the third dinosaur to be named (after Megalosaurus and Iguanodon) and was included among the genera in Owen’s original definition of Dinosauria. Gideon Mantell obtained the first specimen on July 20, 1832 (figure 21.7A) from one of the Wealden sandstone quarries in the Tilgate Forest near Cuckfield in Sussex (the same one that produced Iguanodon). The workers dynamited a rock face to pry loose more slabs and exposed a boulder with dinosaur bones in it. The bones were shattered into about 50 pieces, but Mantell bought it from the workmen anyway. With much effort, he was able to piece it together into a single incomplete skeleton that was partially articulated. This was a big improvement over Megalosaurus and Iguanodon, which were all based on isolated bones. Mantell thought it might belong to his Iguanodon, but William Clift of the Royal College of Surgeons Museum looked at the plates and spikes that were pieces of body armor and suggested that it was something new. In November 1832, Mantell formally named it Hylaeosaurus, which means “forest lizard” in Greek. The name could refer to the Tilgate Forest where it was found or to the old Anglo-Saxon word “Weald,” meaning “forest,” which had given its name to the formation where the dinosaurs were found.

Figure 21.7

The British nodosaur Hylaeosaurus: (A) the original partial skeleton by Mantell; (B) Mantell’s reconstruction as a giant armored lizard; (C) a modern reconstruction of the animal in a life pose. ([A, B] Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; [C] courtesy of N. Tamura)

The preserved bones (figure 21.7A) include most of the front part of the animal, with the shoulder girdles, dermal armor, and shoulder spikes, but most of the skull, forelimbs, and the entire back half of the animal were missing. Mantell’s specimen remained in the partially prepared block until recently. Modern acid etching techniques have managed to free the bones and allow scientists to see them from all sides for the first time. Additional specimens of Hylaeosaurus have been reported from the Isle of Wight, France, Germany, Spain, and Romania, although they may belong to some other type of nodosaur.

Despite the incompleteness of the skeleton, many attempts have been made to reconstruct how Hylaeosaurus might have looked. Richard Owen commissioned Waterhouse Hawkins to create a concrete sculpture for the Crystal Palace Exhibition that made it look like a giant iguana with some spikes along its back (figure 21.7B). More recent reconstructions make it look like other nodosaurs (figure 21.7C), although Hylaeosaurus is so incomplete that it is impossible to reconstruct most of the animal with confidence.

The next nodosaur discovered was Polacanthus, found by the Reverend William Fox in the Lower Cretaceous beds on the Isle of Wight in 1865 (some specimens had been discovered as early as 1843 but were never fully reported or described). Fox originally asked Alfred Lord Tennyson to name it, and he chose “Euacanthus vectianus.” However, Fox reported on it during a lecture to the British Association in late 1865, and the text of a description appeared anonymously in the Illustrated London News. The author was probably Richard Owen, although some speculate it might have been Thomas Henry Huxley, or even Fox. Whoever wrote the article called it Polacanthus foxii (poly meaning “many” and acanthus meaning “thorn” in Greek), and the species name honors Fox—something that Fox could not do because the rules of zoological names prevent an author from naming something after himself.

The skeleton itself consists of some of the back vertebrae, the hip bones, parts of both hind limbs, tail vertebrae, ribs, and the armor of osteoderms and spikes—but no head, neck, forelimbs, or the rest of the front of the body. In 1881 the specimen was acquired by the British Museum from Fox. Fox had let the specimen deteriorate over the years, and the armor was falling apart. British Museum preparator Caleb Barlow glued it all together with a natural resin called Canadian balsam, miraculously restoring it to its original condition. The specimen was not fully studied and described until 1887 when John Whitaker Hulke took over the task. It was redescribed by Nopcsa in 1905, who published the first reconstruction of the animal (figure 21.8). As Polacanthus was one of the first relatively complete nodosaurs to be published, many other fragmentary European fossils have been referred to that genus, making it a taxonomic wastebasket for a long time.

Figure 21.8

Franz Nopsca’s 1905 reconstruction of Polacanthus foxii. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Additional fragmentary skeletons of nodosaurs continued to turn up. Struthiosaurus (ostrich lizard) was described by Emmanuel Bunzel in 1871 from fragments found in a coal mine in Austria. It was the first nodosaur with a partial skull (a braincase), plus a forelimb, hind limb, hip and tail vertebrae, and some ribs. The armor consisted of knob-like osteoderms plus a number of spines and plates, although it is impossible to reconstruct where they fit in the skin of the animal. Nodosaurus (knobbed lizard) was found in the Upper Cretaceous Frontier Formation of Wyoming and described by O. C. Marsh in 1889. It was the first ankylosaur found in North America and was represented by a relatively complete skeleton that showed the dermal armor arranged in bands around the body, with narrow bands over the ribs alternating with wider plates between them. This was one of the first nearly complete nodosaurs found, and it established the basic body plan for the group. With so many partial skeletons with broken and missing pieces, Nodosaurus soon became the name for the entire group.

The best preserved of the early nodosaur discoveries was Edmontonia, discovered by Barnum Brown in the Red Deer River badlands of Alberta in 1915 (figure 21.9). When it was finally cleaned and prepared, it turned out to be the nearly complete articulated front end of the dinosaur, and it forms a dramatic display in the American Museum even today. It was first referred by William Diller Matthew in 1922 to Leidy’s invalid genus Palaeoscincus, but another specimen found by Charles M. Sternberg in the same beds was named Edmontonia in 1928 (in reference to the Edmonton beds where it was found). The misnamed specimens were all eventually assigned to Edmontonia, making it among the best known of the nodosaurs. The articulated American Museum specimen (figure 21.9A) has an armored skull, neck armor, and a solid armored back fringed with large spikes on its shoulders and along the edge of the back shield. It was also among the largest nodosaurs, estimated at 6.6 meters (22 feet) long (figure 21.9B).

Figure 21.9

(A) Barnum Brown’s nearly complete fossil of the front end of the nodosaur Edmontonia, on display in the American Museum. (B) Reconstruction of Edmontonia. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

In the past few decades, the pace of nodosaur discoveries has accelerated, and many new genera were recovered from China and North America. The oldest known nodosaurs are Gargoyleosaurus and Mymoorapelta from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. Nodosaurs become more diverse in the Early Cretaceous with Hylaeosaurus from England, Polacanthus from Austria, Gastonia from the Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah, and Hoplitosaurus from the Lakota Formation of South Dakota. By the late Early Cretaceous, nodosaurs began to diversify explosively with many new genera like Nodosaurus, Sauropelta, Stegopelta, Animantarx, Peloroplites, and Tatankacephalus from the Rocky Mountains of the United States; Pawpawsaurus and Texasetes from Texas; Silvisaurus from Kansas; teeth referred to Priconodon and Propanoplosaurus from the Maryland coast; Europelta from Spain; Anoplosaurus from England; Hungarosaurus from Hungary; and Dongyangopelta and Zhejiangosaurus from China. Found in the latest Cretaceous are the Alberta nodosaurs Edmontonia and Panoplosaurus, Glyptodontopelta from the very end of the Cretaceous of New Mexico, Struthiosaurus from eastern Europe, and a handful of teeth from James Ross Island on the Antarctic peninsula named Antarctopelta.

THE TAR SAND CARCASS

For a group as plagued by incomplete specimens as the nodosaurs, in 2017 it was amazing to hear news that a new nodosaur was known from an almost complete specimen in a death pose, with preservation of skin and scales between and around the bones, and even preservation of some of its color (figure 21.10). The discovery was made on March 21, 2011, when an excavator scooping up tar sands from the Suncor Energy strip mine near Fort McMurray, Alberta, hit a hard object in the midst of the sands. The excavator operator, Shawn Funk, immediately recognized that it was an unusual fossil, and together with his supervisor, Mike Gratton, they notified the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Drumheller, Alberta, which was responsible for paleontological salvage at the oil sand pit. Tyrrell paleontologists Donald Henderson and Darren Tanke rushed up to the mine expecting to find a plesiosaur in these marine sand deposits. Instead they discovered the carcass of a nodosaur that had apparently washed out to sea before being buried. The specimen was found upside down on the seabed, apparently weighted down by its armor. It had floated that way for weeks, and when the soft tissues rotted and the trapped gases escaped it sank to the bottom and was buried in the soft organic-rich sand. The upper part of the specimen was preserved (including the nearly complete head and back shield) because it was buried upside down when it hit the bottom. The belly and legs and tail, however, are mostly missing. They would have been exposed and must have rotted away or been scavenged. The inside of the shell was filled with sand, washed into the body cavity after the soft tissues were lost. Then the chemistry of the rotting tissue precipitated a concretion of siderite (iron carbonate) around it, which protected the specimen and preserved it not only against scavengers but also against deformation when it was buried by later deposits.

Figure 21.10

The tar sand nodosaur mummy, Borealopelta, with nearly all the armor of the head and front of the body preserved intact. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

The specimen was embedded in a sandy cliff about 8 meters (26 feet) above the floor of the mine. Tyrrell and Suncor employees needed 14 days to recover all the pieces and jacket them in plaster for transport. It then took Tyrrell preparator Mark Mitchell five years to put all the pieces together and clean them properly, which is the reason it finally made a big splash on May 12, 2017. It debuted to the public during a big press event the same day that it was published as Borealopelta markmitchelli. Borealopelta means “northern shield” in Greek, and the species name honors the preparator who spent all those years putting it together.

The specimen (figure 21.10) preserves the head shield, neck rings, the pattern of bony armor on its back, and the spines protruding from its shoulders—all articulated as they were in life. There were none of the usual problems of guessing where to put the spines, as so often happens with other nodosaurs. The skin between the bones is well preserved, showing the detailed texture and pattern of the scales. Most remarkable of all, the pigment cells, or melanosomes, can be detected. It apparently was reddish-brown in life, with countershading along the sides and bottom.

Beginning with the puzzling fragments of the earliest ankylosaurs, we now have one of the most complete articulated dinosaurs every found. Ankylosaurs were certainly among the most bizarre and interesting of all the dinosaurs.

FOR FURTHER READING

Brinkman, Paul D. The Second Jurassic Dinosaur Rush: Museums and Paleontology in America at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Brown, Lilian. Bring ‘Em Back Petrified. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1956.

——. Cleopatra Slept Here. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1941.

——. I Married a Dinosaur. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1940.

Carpenter, Kenneth. “Ankylosauria.” In Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs, ed. Philip J. Currie and Kevin Padian, 16–20. San Diego: Academic Press, 1997.

——, ed. Armored Dinosaurs. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001.

Colbert, Edwin. Men and Dinosaurs: The Search in the Field and in the Laboratory. New York: Dutton, 1968.

Dingus, Lowell, and Mark Norell. Barnum Brown: The Man Who Discovered Tyrannosaurus rex. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010.

Farlow, James, and M. K. Brett-Surman. The Complete Dinosaur. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999.

Fastovsky, David, and David Weishampel. Dinosaurs: A Concise Natural History, 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Holtz, Thomas R., Jr. Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages. New York: Random House, 2011.

Naish, Darren. The Great Dinosaur Discoveries. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

Naish, Darren, and Paul M. Barrett. Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 2016.

Spaulding, David A. E. Dinosaur Hunters: Eccentric Amateurs and Obsessed Professionals. Rocklin, Calif.: Prima, 1993.

Vickaryous, Matthew K., Teresa Maryańska, and David B. Weishampel. “Ankylosauria.” In The Dinosauria, 2nd ed., ed. David B. Weishampel, Peter Dodson, and Halszka Osmólska, 363–392. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.