I propose to make this animal the type of the new genus, Tyrannosaurus, in reference to its size, which far exceeds that of any carnivorous land animal hitherto described…. This animal is in fact the ne plus ultra of the evolution of the large carnivorous dinosaurs: in brief it is entitled to the royal and high sounding group name which I have applied to it.

—HENRY FAIRFIELD OSBORN, 1905

OSBORN’S TRIUMPH

Henry Fairfield Osborn was an interesting and pivotal figure in the history of paleontology (figure 14.1). He did more to bring the image of dinosaurs to the public eye than any other person, especially in commissioning huge skeletal mounts and paintings and models of dinosaurs that created the first real wave of public awareness and “dinomania” in the early twentieth century. Modern paleontologists, however, are not so impressed with much of his scientific work, which was tinged with racism and eugenics and odd notions about evolution. They are particularly distressed by his habit of creating too many new species based on meaningless tiny differences between specimens, or his habit of taking credit for other people’s work. He was a study in contrasts, but paleontology would not be nearly so popular without him, nor would there be nearly as many wonderful dinosaurs in museums.

Figure 14.1

Henry Fairfield Osborn in his later years, showing his confident attitude as an American aristocrat and the director of the American Museum of Natural History. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Osborn was born in 1857 to prominent railroad tycoon William Henry Osborn, and for his entire life he lived and behaved and thought like an American aristocrat. The late 1800s, also known as the Gilded Age, was a time when the explosion of industrial might in the United States created a number of tycoons and “robber barons” who acted and believed they were royalty. Osborn carried this haughty, aristocratic attitude throughout his life, which often chafed the people who worked under him.

Stories about Osborn’s condescending, pompous, egotistical behavior are legendary. His biographer, Ronald Rainger, describes him as a powerful, well-connected, American aristocrat, running the department and the museum in a strict hierarchy in which he provided the administration and financial means. His subordinates (many of whom were more competent paleontologists than Osborn) did all the grunt jobs (fieldwork, preparation, curation, illustration, writing, and description), for which Osborn took complete or at least partial credit. A retinue of secretaries and assistants attended to his every beck and call, and they even had separate quarters outside his mansion in Garrison, New York, where they did his bidding when he was at home. At social events, only his top scientific assistants and fellow curators could dine with Osborn and his family; the “lesser staff” were consigned to a different room. George Gaylord Simpson, the legendary mammalian paleontologist who overlapped at the American Museum with Osborn’s later career, describes an incident when he once tried to apply an ink blotter to Osborn’s autograph from a flowing fountain pen. Osborn stopped him and said, “Never blot the signature of a great man.” His arrogance and aristocratic ideas may have made his coworkers angry, but it served him well as he mingled effortlessly with the rich tycoons of New York and got them to donate money to the cause of science.

Like the children of many rich eastern families, Osborn grew up in a mansion with servants in Fairfield, Connecticut, and then was sent to Princeton from 1873–1877 to get his college education alongside other sons of rich men. However, at Princeton he heard of the amazing finds of Marsh and Cope during the Bone Wars (see chapters 7–8) and was hooked on the lure of finding amazing fossils on his own. In an act that only a rich, overconfident child of wealth could imagine, he organized his own field trip out west in 1877 with his classmates Francis Speier Jr. and William Berryman Scott (figure 14.2). (Scott later went on to become a famous paleontologist in his own right, founding the Princeton Geology Department where he spent his career.) Osborn and his friends didn’t want Yale to have a monopoly on the rich bone beds out west, so they set up their own expedition. The three rich young greenhorns managed to survive the harsh conditions out west, avoid being killed by Indians on the warpath, and did it again with a larger party in 1878. They came back more determined than ever to become important paleontologists. Osborn met with both Leidy and Cope during his college years, and Cope became his mentor—thus making Marsh his enemy. Osborn supported Cope during his battles with Marsh, and as the sickly Cope reached desperate financial straits before he died, Osborn generously bought his entire collection for his American Museum.

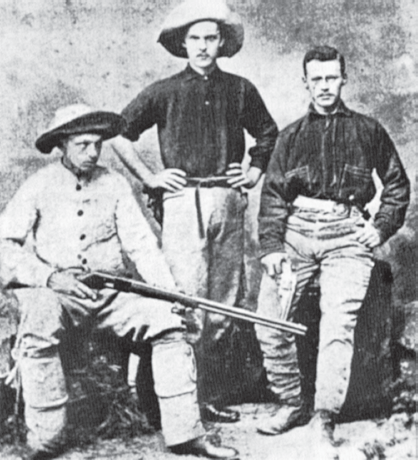

Figure 14.2

Young undergraduates Henry Fairfield Osborn (center), William Berryman Scott (right), and Francis Speier (holding gun) posing before a photographer as they led their own Princeton expedition out to the Wild West collecting fossils in 1877. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Neither Osborn nor Scott could earn a Ph.D. in the United States (such programs did not yet exist here), so they traveled to Europe to experience the cutting edge of scientific research in 1879–1880, taking courses from biologist Thomas Henry Huxley and embryologist Francis Balfour in England (and meeting Charles Darwin) and learning from the leading German paleontologists as well. In 1883, Princeton awarded Osborn its own doctorate and offered him a post teaching biology and comparative anatomy.

By 1891, Osborn’s research in both paleontology and embryology—and his connections—landed him a job at the young American Museum of Natural History in New York as curator and head of the newly formed Department of Vertebrate Paleontology (DVP). He was also appointed to a professorship at Columbia University in New York. This established the Columbia/American Museum paleontology doctoral program, which continued for more than a century. I was trained there, as were many important paleontologists across the United States, including Bruce MacFadden (Florida Museum of Natural History), Bob Emry (Smithsonian), Bob Hunt (University of Nebraska State Museum), Rich Cifelli (Stovall Museum of the University of Oklahoma), and John Flynn (first the Field Museum, now at the American Museum). This program was recently transformed into the Richard Van Gelder graduate program, a recent addition to the American Museum, which offered its doctorates independent of Columbia.

Osborn quickly worked to make the American Museum DVP the best in the world. In addition to purchasing all of Cope’s fossils as the core of their collections, he used his connections among tycoons to procure funding to send field crews out to the Rockies to find many more dinosaurs (see figure 8.2). Several major expeditions to Wyoming yielded spectacular dinosaurs from Bone Cabin Quarry and other places not far from Como Bluff, and other collectors retraced the steps of Cope and Marsh or found new collecting grounds. By the time Osborn died in 1935, the DVP collections were the largest and most important in the world, especially for dinosaurs and fossil mammals.

All this activity drew many talented people to the DVP. These included not only important collectors Jacob Wortman, Olof Peterson, and Barnum Brown, but also outstanding anatomists and paleontologists William King Gregory and William Diller Matthew. Osborn kept a preparators’ lab staffed with numerous talented men who cleaned and prepared the many crates of bones sent from the field, and he invented new techniques for creating large mounts in lifelike poses while hiding most of the supporting structures. Marsh had done this to some extent, but Osborn had a larger vision for paleontology: make these huge skeletons of extinct creatures famous in popular culture and draw big crowds to his American Museum (which he was director of from 1908 to 1933). For this purpose, he hired the first great paleoartist, Charles R. Knight, to create dynamic reconstructions of extinct animals in paintings, murals, and sculptures. Osborn also knew how to create publicity using spectacular accounts of extinct monsters, which were ready-made for reporters to wow the public. The final stroke of luck was promoting a young daredevil, Roy Chapman Andrews, who spearheaded Osborn’s legendary Central Asiatic expeditions in the 1920s to find dinosaurs and mammals (and early humans, which they never found). Many people think Andrews was one of the models for the hero/explorer/archeologist characters such as Indiana Jones and Allan Quartermain.

“NE PLUS ULTRA” IN THE EVOLUTION OF LARGE CARNIVORES

In 1900, Barnum Brown (see chapter 21) was collecting in what is now called the Lance Formation of eastern Wyoming, and he found a partial skeleton of a huge theropod dinosaur. By 1905, the skeleton was prepared, and Osborn named it Dynamosaurus imperiosus (“powerful imperial lizard” in Greek). In 1902, Brown had begun to collect in the Hell Creek beds of central Montana, which were from the latest Cretaceous as was the Lance Formation of Wyoming, and he found another even more complete skeleton of this huge theropod. In the 1905 paper in which Osborn named Dynamosaurus, he called this second specimen Tyrannosaurus rex. He soon began to realize that Dynamosaurus and Tyrannosaurus were the same creature and required only one name. Fortunately for science and dino-enthusiasts everywhere, Osborn published a paper in 1906 in which he used his status as first reviser to suppress the rather confusing name Dynamosaurus in favor of the much more vivid Tyrannosaurus.

Dynamosaurus was not the only name given to the creature before it acquired the name Tyrannosaurus. Numerous fragments of what now appear to be Tyrannosaurus were found many times before 1900. In 1874, Arthur Lakes found some giant teeth near Golden, Colorado, that were probably from Tyrannosaurus. In the early 1890s, John Bell Hatcher collected parts of a skeleton from the Lance Formation in eastern Wyoming that were thought to be from a large Ornithomimus, named Ornithomimus grandis. Cope found some broken vertebrae from the Cretaceous of western South Dakota that he named Manospondylus gigas. The type locality of this find has been relocated and yields Tyrannosaurus fossils, so it’s possible to argue that the two names represent the same dinosaur. If so, scholars will almost certainly petition the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature to suppress Manospondylus as a “forgotten name.” Luckily for posterity, no one is seriously thinking of replacing Tyrannosaurus with Manospondylus or Dynamosaurus! (Ornithomimus is not a problem because it originally was given to a different dinosaur.)

Brown kept finding more of these specimens in the Hell Creek beds, and five partial skeletons were eventually collected. The fourth of these skeletons was by far the most complete, and this became the famous mounted skeleton still on display in the American Museum in New York (figure 14.3). The original Dynamosaurus skeleton was eventually sold to the National History Museum in London, and the first T. rex skeleton (the type specimen) was sold to the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh.

Figure 14.3

Different exhibits of the same Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton in the American Museum: (A) the original mount from 1915 in the tripodal “kangaroo” stance, leaning on its tail; (B) the current mount, redone in 1992, with the animal balanced on its hind limbs and the tail out straight behind it. ([A] Image #327524, courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History Library; [B] courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

In his original 1905 paper, Osborn realized that this discovery was impressive, and he lost no chance to hype it with purple prose. He called it “the ne plus ultra of the evolution of the large carnivorous dinosaurs: in brief it is entitled to the royal and high-sounding group name which I have applied to it.”Wasting no time in making sure the press publicized his prize dinosaur, Osborn sent them lots of information to write about. On December 3, 1906, an article in the New York Times described the creature as “the most formidable fighting animal of which there is any record whatever,” the “king of all kings in the domain of animal life,” “the absolute warlord of the earth,” and a “royal man-eater of the jungle.” In another New York Times article, Tyrannosaurus rex was called a “prize fighter of antiquity” and the “Last of the Great Reptiles and the King of Them All.”

But newspaper publicity about the find was not enough for Osborn. He quickly got his preparators working on cleaning the fossil and creating an impressive mount, and he commissioned Charles R. Knight to create both sculptures and paintings of it, which were soon copied in the media around the world. Tyrannosaurus became one of the most popular of the dinosaurs and was a cultural icon. It first appeared in the 1918 silent film Ghost of Slumber Mountain and later in the 1925 stop-motion version of The Lost World (based on the 1912 novel by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle). Tyrannosaurs made an appearance in the original 1933 version of King Kong and in the 2005 Peter Jackson remake. They have appeared in everything from movies to TV shows (for example, the “Sharptooths” of the Land Before Time series and Barney the Dinosaur on PBS Kids TV). Tyrannosaurus rex was the star and the major villain of the first four Jurassic Park/Jurassic World movies. It has been featured in parade floats and turned into thousands of items of merchandise. There was even a rock band called “T. rex.” It is hard not to be impressed by a huge predator, towering over visitors to the museum. The late paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould said that his first sight of this skeleton at age five both terrified him and inspired him to become a paleontologist.

A REX NAMED “SUE”

In the 114 years since it was first discovered and described, a lot has been learned about Tyrannosaurus rex. The most obvious change is the posture of the dinosaur, as can be seen in the changing position of the mounted skeletons. The original American Museum mount that Osborn supervised depicted it as very reptilian, dragging its tail and walking in a tripodal posture (figure 14.3A).

During the Dinosaur Renaissance in the 1970s and 1980s, paleontologists began to rethink bipedal dinosaur posture. It made more sense that they were active, fast-moving predators, with their bodies balanced on their hind legs in a bird-like stance. This configuration was confirmed by the fact that large theropod trackways never show tail drag marks, and some theropods (such as Deinonychus) have a stiffening network of elongate extensions of their vertebrae preserved in their tails. (This is similar to the ossified trusswork of tendons in duck-billed dinosaurs, and the long extensions of the vertebrae in sauropods.) During the 1970s, paleontologists studying the original, upright Tyrannosaurus rex mounts realized that the pose was impossible. It would cause their limbs to become disjointed, the tail to bend to an impossible degree, and weaken the joint between the skull and neck. When the American Museum revamped their dinosaur halls in 1992, they remounted their Tyrannosaurus rex (Brown’s fourth specimen), which Osborn had put in the kangaroo pose in 1915, with the spine in the horizontal position (only 77 years later). Thanks to the Jurassic Park book by Michael Crichton, and the movie by Steven Spielberg in 1993, most people are now familiar with this horizontally balanced version of Tyrannosaurus rex (figure 14.3B), and the archaic, tail-dragging version seen on many toys and sculptures and images looks odd to us.

The size estimates of Tyrannosaurus rex have also changed over time. Currently, the largest known relatively complete skeleton is in the Field Museum of Natural History (figure 14.4) and is nicknamed “Sue” (after Sue Hendrikson, who discovered it). It measures 3.66 meters (12 feet) at the hips and is 12.3 meters (40 feet) in length, and the number of tail vertebrae is not a guess (as we saw with many incomplete dinosaurs, such as the sauropods, in chapter 10). This is the longest preserved Tyrannosaurus rex fossil we have—there’s a good chance that some individuals were larger. Given that the maximum length of known specimens is not guesswork, it’s surprising that there are a wide range of weight estimates. Over the years the weight numbers have been as low as 8.4 metric tonnes (9.3 tons) to 14 metric tonnes (15.4 tons), but most modern estimates place it between 5.4 metric tonnes (6 tons) and 8 metric tonnes (8.8 tons). A study by Packard and colleagues in 2009 tested the methods used to estimate the dinosaur weights on elephants of known weight and argued that most of the estimates are too high—and this does not accounting for the possibility that Tyrannosaurus rex, like many dinosaurs, may have had air-filled sacs in much of its body. Most recently the estimates given are around 9 metric tonnes and not much higher, so some paleontologists consider a 10-tonne Tyrannosaurus to be very unlikely.

Figure 14.4

The Tyrannosaurus rex specimen known as Sue in the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Recent research has made it possible to better understand the skull and what it could do with its powerful jaws. Unlike most other theropods, which had relatively long slender jaws (chapter 13) or short faces with relatively small teeth such as the abelisaurs of South America (chapter 15), Tyrannosaurus rex had an extremely robust skull and huge teeth and could generate an enormous bite force. The skull of the largest Tyrannosaurus rex was about 1.5 meters (5 feet) long, but it was made lighter due to numerous air pockets and holes in the solid bone, reducing the weight of the head. In cross section, the snout was shaped like an upside-down “U,” making it more rigid and stronger than a typical theropod skull, which has a cross section shaped like an upside-down “V.” The snout was also narrow enough that the eyes could face fully forward, giving Tyrannosaurus rex excellent binocular stereovision and depth perception for hunting. The teeth are enormous, measuring typically about 30 centimeters (12 inches) from tip to root. They curve backward, giving it strength for the teeth to pull back as they rip out hunks of flesh. They were shaped a bit like steak knives, but they were as big as a banana and had serrated ridges on the cutting edges. The front teeth were thicker and deeply rooted, with a D-shaped cross section, giving them strength so they didn’t break when Tyrannosaurus rex bit down and pulled backward.

Instead of being a slashing predator, Tyrannosaurus was a bone-crushing “bulldog dinosaur.” Modern techniques for modeling bite forces suggest that Tyrannosaurus rex could produce 35,000–57,000 newtons (7,900 to 13,000 pounds) of force. This is 3 times more powerful that the bite of the great white shark, 3.5 times as strong as the Australian saltwater crocodile, 7 times more powerful than Allosaurus, and 15 times as powerful as the bite of a lion. Recently that estimate was revised upward to 183,000–235,000 newtons (41,000–53,000 pounds) of force, stronger than the bite of even the giant extinct shark Carcharocles megalodon.

So what did Tyrannosaurus rex do with those powerful jaws? We know that they fought with each other because several skulls show healed wounds on their faces and other bones that could only have been caused by the bite of another Tyrannosaurus rex. Some even have broken teeth embedded in their bones. Clearly they were capable of killing and eating nearly any dinosaur that lived in the Late Cretaceous with them. Unfortunately, the media have given a lot of publicity to the silly argument that Tyrannosaurus rex was primarily a scavenger and not a carnivore. In reality, modern large predators are not so picky. Lions, which mostly hunt their food, will gladly eat carrion when they are hungry; and hyenas, which are famous for breaking down carcasses and crushing bones, are very efficient pack hunters who prefer to kill their own meals when they get the chance. There is no reason to think that Tyrannosaurus rex was a picky eater; rather, it was opportunistic and ate anything it could, especially when it was hungry!

One of the most famous features of Tyrannosaurus rex was its tiny arms. Dozens of cartoons, gags, and even greeting cards have made fun of the fact that its arms seem useless. If you look closely, Tyrannosaurus rex also had only two functioning fingers, whereas most other theropods still had three fingers. Many illustrations of dinosaurs show them with five full fingers, which only occurred in the most primitive dinosaurs (and the ring finger and pinky are always highly reduced). This misconception may have been partially due to the fact that Osborn’s famous 1915 mount of Tyrannosaurus rex in the American Museum was missing its lower arm and fingers, so Osborn made its hands resemble the three-fingered Allosaurus. However, in 1914, Lawrence Lambe showed that the closely related Gorgosaurus only had two fingers. Final proof of this did not come until 1989, when the “Wankel rex” in the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, Montana, was found and had complete forelimbs.

Paleontologists have debated why the forelimbs were so small ever since Tyrannosaurus rex was first found. Osborn suggested that they might have been useful to hold a mate during copulation. Others argued that it would help them rise from a prone position, and recent digital models have shown that to be plausible. More recent research has shown that the actual bones of the arms are quite strong and robust and would have had powerful muscles, capable of lifting 200 kilograms (440 pounds), so they were not weak arms. This suggests they could hold a smaller prey animal more easily than once believed, and they were certainly capable of slashing a prey animal or another Tyrannosaurus rex in close combat. When compared to Carnotaurus, which has even tinier stunted arms with vestigial fingers (chapter 15), the arms of Tyrannosaurus rex are not that small. More important, Tyrannosaurus rex focused on the powerful head and neck and jaws as its primary weapon. Along with its strong hind feet with long sharp claws, it had a different way of feeding than animals that rely on strong arms to catch prey. The arms of tyrannosaurs are most likely vestigial and less important for a predator that primarily used it head and legs.

The intense public interest in Tyrannosaurus rex, plus the ever-increasing number of specimens (over 50 known now), has allowed all sorts of research about them to flourish. For example, several juvenile specimens allow us to look at how they grew up. Unlike many other dinosaurs, which grew rapidly after hatching and then slowed down, tyrannosaur babies grew slowly at first, remaining less than 1.8 metric tonnes (2 tons) until they reached 14 years of age, then growing rapidly to full adult size. During this rapid growth period, they would add about 600 kilograms (1,300 pounds) of weight each year. When they reached an age of 16–18 years, their growth slowed down until they reached full size. The oldest known specimen was about 28 years old, so they had a short life full of slow growth, then fast growth, then a long struggle to survive as a full-sized adult. As Tom Holtz has put it, they “lived fast and died young.” In fact, over half of the specimens of Tyrannosaurus rex seemed to have died within six years of reaching sexual maturity around age 18. This is a common pattern among some birds and mammals that have high infant mortality rates, then rapid growth to adult size, and finally high death rates as adults due to battles over mating and the stresses of reproduction.

Many scientists have tried various methods to see if Tyrannosaurus rex shows sexual dimorphism (differences in males and females), but no study has been convincing so far. Only one specimen has been conclusively demonstrated to be female as it had medullary tissue in a number of bones. This bone tissue is only found in female birds that are laying eggs; they lay down spongy porous medullary tissue in their bones as they divert calcium to their eggs and embryos.

One of the most significant changes in how we think about Tyrannosaurus concerns its body covering. For almost a century, it was rendered as a big scaly reptile, a lizard on steroids. The only known skin impressions of Tyrannosaurus preserve a mosaic of small scales. In the 1990s, discoveries in China produced many fossils of dinosaurs, birds, and mammals with soft tissues preserved, especially in lake shales, which are low in oxygen and formed in stagnant water (see chapter 18). These produced a small tyrannosaur called Dilong paradoxus, which clearly showed filamentous feathers or fluff on its body. When a larger tyrannosaur, Yutyrannus halli, was found in China, it too was covered with a coat of feathers. Given that these animals are very closely related to Tyrannosaurus rex and all other tyrannosaurs, it is extremely likely that the iconic dinosaur of the five Jurassic Park movies was not the scaly lizard that the movie makers created but a bird-like creature with a coating of down or at least feather tufts over much of its body. Of course, by the second movie (Jurassic Park: The Lost World), the filmmakers stopped listening to paleontologists and continued to show all the dinosaurs as scaly lizard-like creatures, without adding feathers to any of them. This was truly sad for many of us in paleontology. The original novel and movie was up to date with the current state of dinosaur research in the early 1990s, but they abdicated their efforts to keep the movies current and just gave the audience the scaly monsters they had come to expect.

TYRANNOSAURS BECOME TSOTCHKES

One of the most spectacular and popular dinosaurs of all, Tyrannosaurus rex always makes the front page of major newspapers when a new specimen is found (possibly the only fossil that can make that claim other than human fossils). The pressure is on for collectors (both professional paleontologists and poachers) to find more specimens. The situation reached a crisis level when the famous skeleton of Sue was found on a ranch in western South Dakota. It was collected by a commercial fossil-hunting firm called the Black Hills Institute for Geologic Research. They are a group of people who collect fossils for profit, although they also maintain a well-curated museum. Many scientifically important specimens have been lost forever to science because they were sold to the highest bidder.

The discovery of Sue (figure 14.4) in 1990 completely changed the way tyrannosaurs are viewed in the public eye. They were no longer important scientific discoveries that needed to be accessible to any qualified researcher but were objects to score a big cash payout. The situation became messy when the legal rights to the land where Sue was found were challenged. The police confiscating the fossil from the Black Hills Institute, and its director, Peter Larson, went to jail on charges of tax evasion. Eventually, the ownership issue was resolved, and Sue was on the auction block. Everyone in the paleontological community feared that this scientifically irreplaceable specimen would end up in some millionaire’s mansion or in a corporate lobby as an expensive showpiece. The bidding reached $8 million, far above the budget of any public museum. The Field Museum persuaded McDonald’s, Disney, the California State Universities, and several other donors to pitch in, and they won the bid at over $8 million. Sue was then prepared and mounted at the Field Museum, where it is still on display (although it was recently moved from its original place on the floor of the Stanley Field Hall).

The $8 million price tag to keep Sue from becoming some millionaire’s expensive showpiece caught the attention of poachers, and trade in illegal specimens unfortunately flooded the auction houses. Fossils were suddenly very valuable, and important collecting areas were heavily poached. Not only did the poachers steal the fossils illegally and remove them from further study by science, but in many cases they damaged the fossils by hacking them out carelessly due to their hurry to get the bones out before they were caught in the criminal act. Sometimes poachers “enhanced” the specimens with reconstructed plaster fakery to jack up its price. Worse still, poachers usually don’t care about any of the information that comes from the beds that surround the fossil, which can tell geologists the age of the beds, the environment in which they were formed, and provide many other important pieces of information. For years after the Sue auction, hundreds of critical specimens were lost or destroyed in the mad rush by poachers to rape the land and make a buck.

This story highlights a much bigger problem, which most people never hear about: the huge international black market in stolen fossils and antiquities. Bit by bit some governments are becoming better at protecting their national treasures, but the poachers and smugglers are always much better funded and quicker even than Interpol. Not only is there a large black-market trade in stolen artwork and artifacts, but the market in natural objects is equally brazen and profitable. The stories I’ve heard just make us cry! Famous fossil localities in protected national parks all over the world have been brazenly poached by thieves, not only destroying most of the fossils but ruining the scientific value of the locality as well. Museum research collections, and even specimens on public display with security guards and video cameras protecting them, are stolen or damaged by thieves. One-of-a-kind fossils that are certainly new species and genera and have the potential to revolutionize our understanding of life’s history are seen briefly and then end up in some rich person’s foyer. Major auction houses and the more reputable fossil dealers have to be careful and identify poached specimens with fraudulent locality data hiding the illegality of their collection. I’ve heard the horror stories from my colleagues who had the proper permits and found an important bone bed on public land, only to come back a few days later and find that someone had plundered the best material and left the rest in broken piles, hacked out of the ground with no attempt to protect the fossil in a jacket—or record the location and stratigraphic horizon of the specimen, which is a big part of its scientific value. It’s common practice now for scientists to bury their excavation and hide it once they leave to prevent this from happen. Museums have ask me not to publish GPS coordinates of my sites, which also might give away fossil localities. My fellow paleontologists in the fossil-rich national parks spend more and more time planning how to prevent poaching and less time doing the science they are better qualified to do. The situation on private land is even messier. It is usually legal to collect on most privately held ranches with the consent of the landowner, but the story of the tyrannosaur named Sue illustrate that handshake agreements, disputes over where the specimen was found, and unclear property rights can make those specimens a legal nightmare.

The Sue story puts museums in a catch-22 situation. They do not have the money to bid on these scientifically important specimens unless they receive funding from rich sponsors (as did Sue), and they don’t want to bid on specimens with questionable provenience because these specimens are probably poached and their sale would encourage lawbreakers. However, museums want to make their best effort to keep scientifically important specimens in the public domain where they can be studied and researched and yield their secrets, and eventually be put on display for the public to see.

The issue reached a crisis point in 2012 when some specimens came up for auction at a prominent New York auction house. The buzz was going back and forth among my paleontologist colleagues for weeks: an important tyrannosaur skeleton (Tarbosaurus bataar) that had been poached in Mongolia was scheduled to be auctioned on May 20 in New York City. We paleontologists were all outraged and spent days signing online petitions, blogging, and sending letters and emails to the appropriate parties, but the tiny scientific community of vertebrate paleontologists in the United States (no more than 2,000 people) doesn’t hold any real power beyond a handful of museum curator positions and top professorships. Our activity did get the attention of the Mongolian government, however, and they sent formal letters of protest to the auction house and to the U.S. government. All the emails and blog posts were full of anger and despair that such a blatant theft could be rewarded with a million-dollar sale.

Just hours before the auction was to start, a Texas judge issued a Temporary Restraining Order, putting the sale of the Mongolian tyrannosaur on hold, but the auction house went ahead with the sale, receiving a final bid over $1 million, and arguing that the Texas judge had no jurisdiction over a New York auction house. This occurred even as the attorney for the Mongolian government was in the auction room with the Texas judge on his cell phone, trying to make himself heard and to get anyone to listen to the judge. Shortly after the bid of $1 million, the sale was stopped pending further investigation. The wheels of justice began to grind slowly as investigators dug into the data about the fossil, tracked down the anonymous “paleontologist” who had procured it, and supplied the information to our legal system. Just before New Year’s Eve 2013, the story broke that the culprit, poacher Eric Prokopi of Gainesville, Florida, had been arrested and pleaded guilty.

The evidence against him was overwhelming. Not only was he caught with multiple dinosaur specimens from Mongolia in his possession in his Florida home, but another dinosaur from Mongolia arrived at his address while he was being investigated! In his possession were illegal specimens from Mongolia and illegal fossils from China, such the “four-winged” dinosaur Microraptor gui, which comes from a very specific area of the Liaoning Province of China and cannot be sold or even removed from China under any legal means. Investigators found abundant emails from Prokopi’s computer, and from those of his associates, that established he knew the specimen was illegal and was doing his best to cover up its illegality (despite his assurances to the auction house and forged documents proving that the specimen was not from Mongolia). There were even pictures of him in Mongolia collecting the specimens from a well-known locality easily identified in the photo, proving that he not only smuggled specimens in and out but apparently snuck in and out of the country illegally as well. No wonder he pleaded guilty—no competent lawyer could make the case that he was not aware of what he was doing in the face of such damning evidence.

The judge had the option of sentencing this criminal to as much as 17 years in prison. Most paleontologists were in favor of a stiff sentence because this guy was so blatant in his lying and deception and stood to make millions on his poached specimens. In addition, it would send a message to other poachers and smugglers that their long-unsupervised activities just got a lot riskier. Sadly, the judge gave him only a three-month sentence, a mere slap on the wrist, because he agreed to turn informant and cooperate in the arrest of the entire smuggling pipeline. His only other punishment was the loss of all his illegally gained fossils. The entire story is told in detail in Paige Williams’ new book, The Dinosaur Artist.

Sources tell me that nearly all other Mongolian fossils are off the block for a while because other auction houses are leery of bad publicity or getting in trouble with the law. Maybe it will put a chill in the smuggler’s pipeline back to Mongolia and China as well. What hasn’t been revealed yet is how such a large specimen was so easily smuggled out of Mongolia and, even more amazing, through U.S. Customs. So far all we’ve heard is that Prokopi mixed the tarbosaur bones with a crate of “miscellaneous reptile fossils” shipped from a middleman in England. It turned out that the “75 percent complete” skeleton was actually a composite of several different skeletons, not one individual. Such fakery is common among commercial fossil dealers and smugglers. Clearly further investigation of this criminal enterprise is needed, and Prokopi is just the tip of the iceberg.

Some people attempted to excuse Prokopi by comparing him to “Indiana Jones,” but they apparently misremember the movies. Indy was dedicated to bringing archeological relics to museums and keeping them in the public trust, not selling them to the highest bidder. (Today most archeologists wouldn’t even consider removing artifacts from their country of origin due to the increased sensitivity of most countries to the pillaging of their cultural heritage.) No, Prokopi is like the character Belloq in the first Indiana Jones movie (or the thieves in the beginning of the third Indiana Jones movie) who gleefully sells any object (and their services) to whoever would pay for them. As paleontologist Peter Harries of the University of South Florida pointed out at the end of an article that defended Prokopi: “I don’t think Indiana Jones wanted to sell the Ark of the Covenant for $1 million.”

FOR FURTHER READING

Carpenter, Kenneth, and Peter Larson. Tyrannosaurus Rex, the Tyrant King. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008.

Colbert, Edwin. Men and Dinosaurs: The Search in the Field and in the Laboratory. New York: Dutton, 1968.

Erickson, Gregory M., Peter J. Makovicky, Philip J. Currie, Mark A. Norell, Scott A. Yerby, and Christopher A. Brochu. “Gigantism and Life History Parameters of Tyrannosaurid Dinosaurs.” Nature 430, no. 7001 (2004): 772–775.

Farlow, James, and M. K. Brett-Surman. The Complete Dinosaur. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999.

Fastovsky, David, and David Weishampel. Dinosaurs: A Concise Natural History, 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Henderson, M. The Origin, Systematics, and Paleobiology of Tyrannosauridae. Dekalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2005.

Holtz, Thomas R., Jr. Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages. New York: Random House, 2011.

——. “The Phylogenetic Position of the Tyrannosauridae: Implications for Theropod Systematics.” Journal of Palaeontology 68, no. 5 (1994): 1100–1110.

——. “Tyrannosauroidea.” In The Dinosauria, 2nd ed., ed. David B. Weishampel, Peter Dodson, and Halszka Osmólska, 111–136. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

Hone, David. The Tyrannosaur Chronicles: The Biology of Tyrant Dinosaurs. London: Bloomsbury, 2016.

Horner, John R., and Kevin Padian. “Age and Growth Dynamics of Tyrannosaurus Rex.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 271, no. 1551 (2004): 1875–1880.

Molnar, Ralph. Tyrannosaurid Paleobiology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013.

Naish, Darren. The Great Dinosaur Discoveries. Berkeley: University of California Press: 2009.

Naish, Darren, and Paul M. Barrett. Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 2016.

Osborn, Henry Fairfield. “Tyrannosaurus and Other Cretaceous Carnivorous Dinosaurs.” Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 21, no. 14 (1905): 259–265.

Wilford, John Noble. The Riddle of the Dinosaur. New York: Knopf, 1985.

Williams, Paige. The Dinosaur Artist: Obsession, Betrayal, and the Quest for the Earth’s Ultimate Trophy. New York: Hachette Books, 2018.

Xing Xu, Mark A. Norell, Xuewen Kuang, Xiaolin Wang, Qi Zhao, and Chengkai Jia. “Basal Tyrannosauroids from China and Evidence for Protofeathers in Tyrannosauroids.” Nature 431, no. 7009 (2004): 680–684.