Skeletons of a huge, meat-eating dinosaur that overshadows Tyrannosaurus rex have been discovered in Argentina. The newly revealed species is one of the biggest carnivores ever to have walked the Earth, dinosaur experts say. At least seven of the animals were uncovered together in a mass fossil graveyard in western Patagonia, a region famous for giant-dinosaur remains. Living some 100 million years ago, the largest specimen was more than 40 feet (12.5 meters) long.

—JAMES OWEN, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC NEWS, 2006

WHO’S ON FIRST?

Thanks to a century of publicity and fame, most people think Tyrannosaurus is the largest land predator ever known. That was certainly true for most of the twentieth century when it was one of the few large theropod dinosaurs known. In the past 30 years, more remote and less explored parts of the world have yielded spectacular dinosaurs that routinely exceed the early North American finds everyone knows for their weirdness and great size.

Patagotitan, Argentinosaurus, and the other enormous titanosaurs of South America are discussed in chapter 10. Indeed, South America has been one of the most productive areas for finding new dinosaurs in the past 40 years (along with China, which was shut off from the Western world until 30 years ago when the Cultural Revolution ended). But thanks to the hard work of José Bonaparte (see chapter 5) and many of his students and colleagues, more and more of the huge and bizarre dinosaurs of Argentina have been discovered.

One of the richest areas is the Neuquén Province in northern Patagonia, which covers much of the dry foothills of the Andes Mountains. Amateur fossil collector Ruben Carolini was riding his dune buggy through these Middle Cretaceous badlands near Villa Chocon in 1993 when he spotted a large bone. He called specialists from the Natural History Museum of Comahue to come and look at it, and they quickly excavated a large nearly complete skeleton of a theropod. The partial skull was scattered over a wide area of 10 square meters (110 square feet) when it was originally found. Like most dinosaur finds, the rest of the skeleton was scattered around with no two bones attached to each other (disarticulated). However, it was still about 70 percent complete, with the skull and jaws, most of the backbone, pectoral and pelvic girdles, and most of the hind limb bones. The arms and hands were missing, but this is a lot more complete than many other dinosaurs (including most of the huge sauropods discussed in chapter 10).

By 1994, my friend and colleague, theropod specialist Rodolfo Coria of the Muséo Carmen Funes, was working on the fossil with Leonardo Salgado. I vividly remember hearing him speak about the find at the 1994 meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, and the enormous size of this predator took my breath away; the entire room filled with the world’s best dinosaur paleontologists was equally impressed. Science writer Don Lessem saw pictures of the enormous leg bones and helped the Argentinians fund further excavation and preparation of the fossil.

By 1995, Coria and Salgado published their description of all the bones that had been found. They named it Giganotosaurus carolinii. The genus name is Greek gigas for “huge,” noto for “southern,” and sauros for “lizard,” and the species name honors its discoverer. The correct pronunciation, as I’ve heard it from all the dinosaur experts at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meetings, is “GIG-a-NOTE-o-saurus” (just as we say “GIG-a-byte” not “JIG-a-byte”). Unfortunately, most people read the name as “Gigantosaurus” and mispronounce it as well. The name “Gigantosaurus” was originally used for a few tail bones of a huge titanosaur sauropod from England (see chapter 10), and it is no longer considered diagnostic enough to be a valid genus. So not only is the name not “Gigantosaurus,” as many misread it, but no dinosaur could be given that name because the name was used previously.

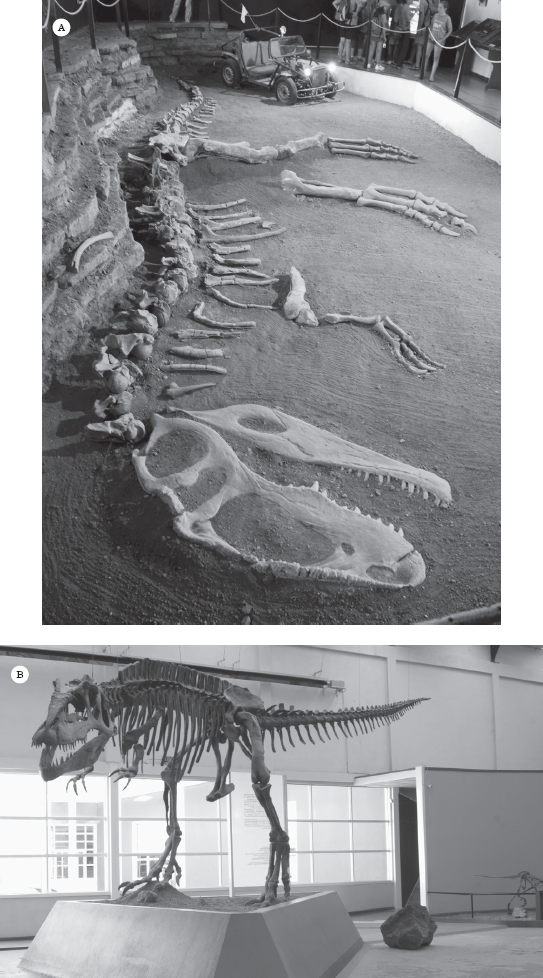

The specimen is currently displayed at the Muséo Municipal Ernesto Bachman in Villa Chocon, near where it was found (figure 15.1A). The original fossils are not placed in life position in a mount but lie flat on a bed of sand in articulated position, looking as if they had just been exposed. (Remember, it was not discovered in this state.) In the next room is a mounted replica of those same bones, posed in a lifelike position (figure 15.1B). Giganotosaurus has become so famous in recent years that casts of it are on display elsewhere in Argentina, including at the Muséo Municipal Carmen Funes in Plaza Huincul, as well as at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, the Fernbank Museum of Natural History in Atlanta, the Naturmuseum Senckenberg and the Frankfurt Hauptbahnhof in Frankfurt am Mein, Germany, the Hungarian Natural History Museum, and the Australian Museum in Sydney.

Figure 15.1

(A) Original skeleton of Giganotosaurus on display at Muséo Municipal Ernesto Bachman in Villa Chocon, Argentina; (B) mounted replica of the original skeleton in the Museo Municipal Carmen Funes in Plaza Huincul, Argentina. ([A] Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; [B] courtesy of R. Coria)

What kind of dinosaur was Giganotosaurus? Like its close relative Carcharodontosaurus (figure 15.2), the skull was lightly built with arches and struts of bone and lots of openings; the skull was not quite as high and arched as Carcharodontosaurus but lower and flatter on top. There were roughened areas above the eyes and the top of the snout. The rear of the skull had a forward slant, so the jaw joint hangs behind and beneath the attachment point between the neck and the back of the skull. It was definitely not the robust, heavy crushing skull seen in Tyrannosaurus. It also lacked the sagittal crest along the top midline of the skull, where the jaw muscles attached, suggesting its bite was not as powerful as that of some other huge theropods. Some estimates suggest its bite was only a third as powerful as the bite of a T. rex. The teeth were like knife blades, compressed side to side and with the point curved backward, and they had serrations on both the front and back cutting edges. Nonetheless, it had a robust neck, so it could cope with struggling prey after it had a bite on them. This suggests it did not try to crush its prey with a bulldog bite, as did a tyrannosaur, but may have slashed it and then allowed it to bleed to death. It also suggests that it may have taken smaller prey than that of the largest dinosaurs.

Figure 15.2

The skull of Carcharadontosaurus from the Kem Kem beds of Morocco. (Courtesy of P. Sereno)

How big was Giganotosaurus? It is very difficult to get a reliable estimate of size for dinosaur skeletons, even when they are complete, like Tyrannosaurus, or nearly complete, like Giganotosaurus. Most of the back and tail vertebrae of Giganotosaurus are known, so we can estimate its length at around 12.5 meters (41 feet), whereas Sue, the largest complete tyrannosaur skeleton, is about 12.3 meters (40 feet) in length. A more direct comparison is the length of complete bones that scale with size, so the thighbone of Giganotosaurus is 1.3 meters (4.7 feet) long and more robust than that of a tyrannosaur, and that of Sue is 5 centimeters (2 inches) shorter. Coria has also described a fragmentary jaw for a Giganotosaurus that is even larger than the original type specimen. Although the size differences are not dramatic, it seems that the largest Giganotosaurus is longer than the largest tyrannosaur.

What about weight? Estimating weight is even less precise than direct comparisons of complete bones or spinal columns. Coria and colleagues originally estimated the weight of Giganotosaurus around 6–8 metric tonnes (6.7–8.7 tons), although in 1997 Coria upped the estimate to 8–10 metric tonnes (8.8–11 tons) based on the incomplete lower jaw that was about 8 percent larger than the original specimen. Other methods of calculating the weight of dinosaurs have given results for 6.6 metric tonnes (7.3 tons) to 6.5 metric tonnes (7.2 tons) to 8 metric tonnes (8.2 tons) to 8.21 metric tonnes (9.0 tons) to as much as 13.8 metric tonnes (14 tons). In short, the size ranges of tyrannosaurs and Giganotosaurus overlap, with the largest specimens of Giganotosaurus just slightly larger than the largest T. rex.

Giganotosaurus was not the only huge predator in Argentina at that time. From 1997 to 2001, the Argentinian-Canadian Dinosaur Project was digging in the Huincul Formation at Cañadón del Gato, the same beds that produced Argentinosaurus. These beds are only slightly younger than those that produced Giganotosaurus, dating between 93.5–97 million years old, whereas the Giganotosaurus fossils come from beds 97–100 million years in age. They began to find another huge theropod, with fragments of bones representing most parts of several skeletons, and in 2006 Rodolfo Coria and Canadian paleontologist Phil Currie from the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta described these fossils. They gave it the name Mapusaurus, from the Mapuche word mapu meaning “of the earth” and saurus, “lizard.” Although it is less complete and far more fragmentary than the extraordinary Giganotosaurus skeleton, the similar parts of Mapusaurus are almost all the same size as those in Giganotosaurus.

The bone bed contained the fossils of at least seven different individuals of Mapusaurus, mostly in different growth stages. The accumulation of so many theropods has stimulated a lot of speculation and discussion. Some think that this represents a death assemblage of a family or a pack of theropods, and that Mapusaurus was a social pack hunter. Others argue that the death assemblage is the accidental accumulation of a number of skeletons washed into a backwater sandbar. This kind of all-predator assemblage is not unique to Mapusaurus. The famous Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry in northern Utah is composed almost entirely of Allosaurus and other predators, and there is no consensus on whether this is a natural biological assemblage or something that the water currents arranged and collected.

If those two huge predators were not enough, yet another one was found in 2005 and described by Argentinian paleontologists Fernando Novas, Silvina de Valais, and Australian paleontologists Pat and Tom Rich. They come from the Chubut Province in the southern part of Patagonia and are older than the previous dinosaurs, dating from 112–120 million years in age. Named Tyrannotitan chubutensis by Novas and colleagues, it consists mostly of a partial skull, a few backbone elements, and part of the hips and hind limbs. It is too fragmentary to reliably estimate its size, but the original estimates of length were 11.4–13.0 meters (37–44 feet), only slightly shorter than Mapusaurus and Giganotosaurus, and between 4.9 and 7 metric tonnes (5.4–7.7 tons). As with Mapusaurus, Giganotosaurus, and Tyrannosaurus, the measurements of the largest individuals overlap, so it’s difficult to know which of these four dinosaurs was truly the largest.

BACK TO AFRICA

No claim of “largest this” or “longest that” goes unchallenged in dinosaur paleontology for very long. Soon after Giganotosaurus was becoming familiar and established as the “largest predator,” another discovery in Africa pulled the spotlight away from South America. In 1995, my classmate, coauthor, and good friend Paul Sereno (see chapter 5) was in northwestern Africa on the fringe of the Sahara Desert in the Kem Kem beds of Morocco. The crew found enormous bones of sauropods in many places, but one of the most striking discoveries was the skull of an enormous predator. When Sereno and his colleagues put the skull together, they realized it was a complete skull of a dinosaur that had been previously named (figure 15.2). In 1924, French paleontologists Deperet and Savornin obtained two enormous shark-like dinosaur teeth from the Middle Cretaceous of Algeria. With only teeth to go on, they referred the specimens to the wastebasket taxon Megalosaurus, which was used for nearly every fragmentary theropod for a long time (see chapter 1), but they called it Megalosaurus saharicus. Then German paleontologist Ernst Stromer (see chapter 13) obtained a partial skull, teeth, vertebrae, partial hip bones, leg bones, and claws during his excavations at Bahariya Oasis in western Egypt. The original fossils were found in 1914, but they did not reach him until the early 1920s due to World War I and other delays. When he finally studied and published the fossils in 1931, he realized the teeth resembled the ones found in Algeria, but it was a completely different dinosaur than Megalosaurus. Based on those fragments and the similarity of the teeth to those of the great white shark Carcharodon, he renamed the dinosaur Carcharodontosaurus saharicus.

Unfortunately, the original fossils of Carcharodontosaurus in the Munich Natural History Museum were destroyed during the same 1944 bombing that wiped out the original material of Spinosaurus and nearly all of Stromer’s Egyptian fossils. Sereno and his colleagues realized that they had found an even more complete fossil of Stromer’s Carcharodontosaurus, sufficient to replace the lost specimens destroyed during the air raid. It’s not often that we find even better specimens when the originals are lost due to unfortunate circumstances!

Similar to Giganotosaurus but unlike Tyrannosaurus, the skull of Carcharodontosaurus is built of struts and arches of bones with lots of open spaces for reducing weight (figure 15.2). However, the skull of Carcharodontosaurus has a much higher arch than the relatively flat-topped, low skull of Giganotosaurus. As previously mentioned, its distinctive feature is the narrow, knife-like teeth suitable for slashing, which are not very different from the teeth of the great white shark. Like all of these dinosaurs (Giganotosaurus, Mapusaurus, and Tyrannotitan), these features of the skull and teeth define a group that is now called the carcharodontosaurs. This group of dinosaurs is, in turn, closely related to Concavenator from the Cretaceous of Spain; Acrocanthosaurus from Oklahoma, Texas, and Wyoming; and Shaochilong from China. Similar to most of the dinosaur groups we have seen, carcharodontosaurs were distributed across most of the Pangea continents (South America, North America, Africa, Europe, and Asia), with only the poor Cretaceous record in Australia and Antarctica preventing them from being completely cosmopolitan—although Australia has now produced a distant relative of the carcharodontosaurs, known as Australovenator.

How big was Carcharodontosaurus? We have only a skull and fragments of the skeleton to go on. The most common method of establishing body size in this case is the length of the skull, which measured 1.6 meters (5.2 feet), one of the longest predatory dinosaur skulls known. Using typical scaling relationships, this gives a length for Carcharodontosaurus of about 12–13 meters (39–43 feet), and a weight between 6 and 15 metric tonnes (6.6–16 tons).

The original skull of Giganotosaurus was fragmentary, and there is some question of the reliability of the skull length estimates for a skull reconstructed from pieces. Coria and coauthors believe that it reached 1.8 meters (5.9 feet), with a body length of about 13 meters (42 feet). This is only slightly larger than Carcharodontosaurus, but the measurements of the two dinosaurs largely overlap. However, the largest specimen of Giganotosaurus is a lower jaw, which suggests a skull 1.95 meters (6.4 feet) long, and a length of 13.2 meters (43 feet). Once again, we are faced with the dilemma of who is biggest. At least four large carcharodontosaurs seem to have an overlapping range of sizes. The largest specimens of Giganotosaurus are just marginally larger than the rest, but there is no dramatic difference that makes any one dinosaur stand out as the clear Numero Uno.

Regardless of the outcome of the debate, it’s clear that the largest predators that ever lived were the carcharodontosaurs, and the largest ones lived in the Early-Middle Cretaceous of South America and Africa.

THE “FLESH BULL”

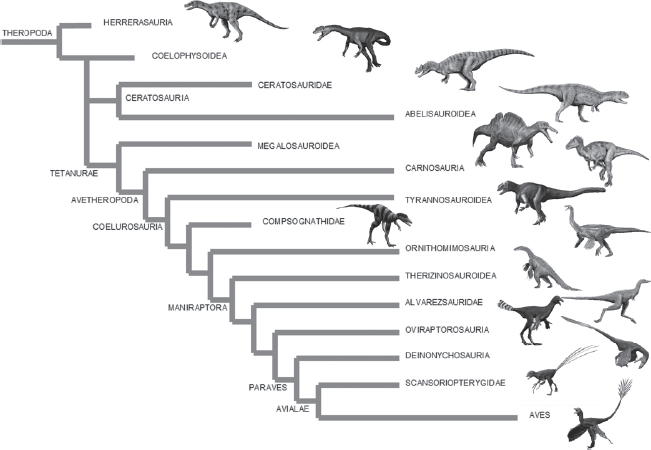

Predatory dinosaurs show a lot of regional differences in the Cretaceous (figure 15.3). Tyrannosaurs and ornithomimids (ostrich dinosaurs) ruled North America, China, and Mongolia, but they were not found much outside of these regions. In contrast, South America and Africa not only had carcharodontosaurs and spinosaurs in the Late Cretaceous but also had several predatory dinosaurs not found in North America. This is comparable to the way that titanosaurs dominated the sauropod faunas of South America and Africa in the Cretaceous but were found only in the southwestern part of North America, and only in the latest Cretaceous.

Figure 15.3

Family tree of the theropods showing the major branches discussed in this book. (Redrawn from several sources)

In addition to the huge carcharodontosaurs and spinosaurs, another characteristic group of theropods found mainly in South America and other southern continents, such as India and Madgascar, were the abelisaurs. Most of these theropods were not as large as the carcharodontosaurs or spinosaurs, although one specimen from Kenya has been reported at professional meetings but not yet published that may be as long as 12 meters. Abelisaurs were distinctive, with relatively short and deep snouts and lots of smaller, simpler conical teeth (rather than the shark-like teeth of carcharodontosaurs or the banana-shaped teeth of tyrannosaurs). Most of them have extremely reduced forearms.

The first known example was Abelisaurus itself, discovered and described by (who else?) José Bonaparte and Fernando Novas in 1985. Another was Aucasaurus, described by Rodolfo Coria, Luis Chiappe, and Lowell Dingus in 2002 from the Auca Mahuevo locality that produced so many dinosaur eggs. Unlike Abelisaurus, which was known only from a skull, Aucasaurus is based on a nearly complete skeleton that measured 6.1 meters (20 feet) in length. This is not as long as the carcharodontosaurs but it was still a big predator. Other large South American abelisaurs include Skorpiovenator, Ekrixinatosaurus, and Ilokelesia.

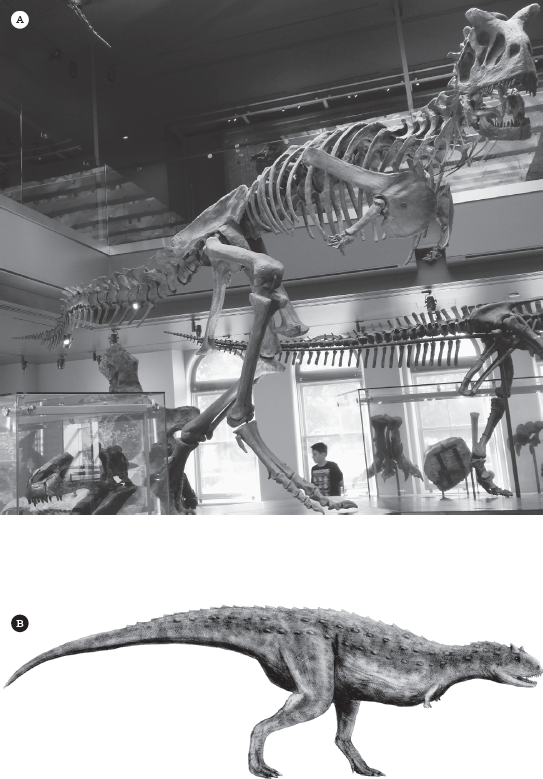

But the weirdest (and most famous) of these strange predators was Carnotaurus (figure 15.4A–B). Discovered and described by José Bonaparte in 1985, its name means “flesh bull” in Latin, in reference to its flesh-eating habits and the strange pair of bull-like horns over its eyes. The horns give it a wicked or even diabolical appearance, so naturally it was the villain in Disney’s 2000 movie Dinosaur, the first film on dinosaurs produced with computer graphics. According to insider accounts, Disney’s animators originally planned to use Tyrannosaurus rex because of its iconic status as a terrifying giant predator, but they switched to Carnotaurus when they saw its horns. Since then, Carnotaurus has appeared in a number of films and TV shows, including the kid’s show Dinosaur Train (where it is friendly and benevolent, not a nasty killer—the show is for preschoolers after all). It also made an appearance in the 2018 movie Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom, where it almost kills dinosaur wrangler Owen Grady (played by Chris Pratt) until a T. rex kills it—all while the volcano is erupting in the background.

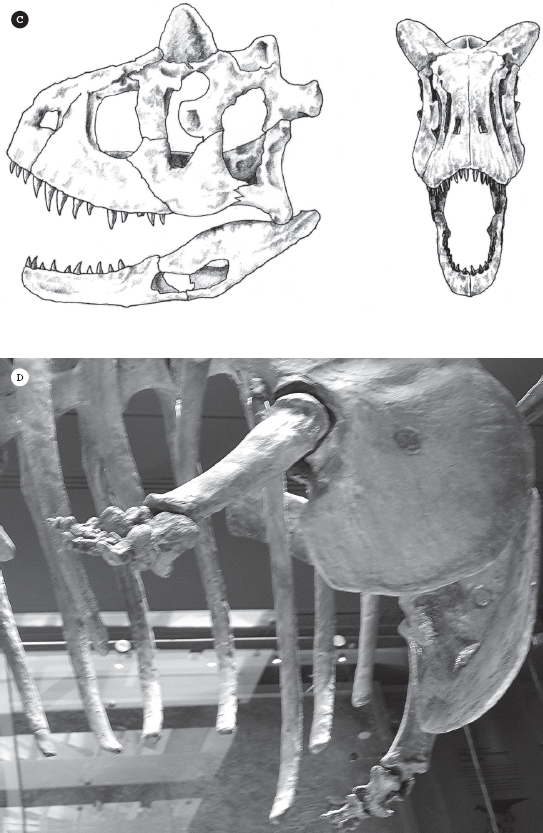

Figure 15.4

Carnotaurus, the “flesh bull”: (A) mounted replica of the original skeleton in the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County; (B) reconstruction of the animal in life; (C) diagram of the skull; (D) close-up of the tiny, nonfunctional arms with almost no fingers. ([A, D] Photographs by the author; [B] courtesy of N. Tamura; [C] courtesy of R. Coria)

Like other abelisaurs, Carnotaurus had a short deep snout (figure 15.4C) with lots of smaller conical teeth, which are suited for a quick slashing or nipping bite on the prey. Carnotaurus also had a strong, bull-like neck for grappling with prey once it had a bite on them, or wrestling with other members of its species. The skull had lots of bony struts and was lightly built, so Carnotaurus could probably stretch the joints and open its mouth very wide around a smaller prey item. In contrast, the skull of a T. rex was solidly built for inflicting a powerful crushing bite, not ripping out chunks of the prey animal until it bled to death. The bite force of Carnotaurus was not that strong, but it still was much stronger than that of a crocodile or an alligator.

If people mock tyrannosaurs for having small arms, abelisaurs had ridiculously tiny arms (figure 15.4D). Aucasaurus had tiny arm bones with no finger bones in its hands. Carnotaurus was almost as bizarre, with lower arm bones much shorter than the upper arm bones, and only two functional finger bones (index and middle finger), which were short and stubby. Its wrist bones never developed but apparently remained as cartilage, as did any other fingers it might have had. Only the middle finger had a claw. The tip of the ring finger is missing, and instead a long bony spur stuck out of the side of the hand. Paleontologists have made the argument that tyrannosaurs might have had some limited function of their tiny arms (see chapter 14), but clearly the limbs of abelisaurs were virtually useless. They are what are known as vestigial organs, which were in the process of being lost but were not completely gone (even if they had no real function).

In addition to the lightweight skull, the overall build of Carnotaurus was lighter than the tyrannosaurs or allosaurs or other large predators. Unlike most dinosaurs, Carnotaurus is based on a nearly complete articulated skeleton found by José Bonaparte in 1985 in its death pose, so most of the skeleton (except the lower hind leg bones and most of the tail) is present. It measures 9 meters (30 feet) long, with a body weight of 1.35 metric tonnes (1.5 tons). It had relatively long slender hind limbs, suggesting it was one of the fastest runners among the theropods. This is confirmed by the structure of the thighbone, which appears to be able to withstand a lot of bending and twisting. It is hard to reliably estimate speed in the dinosaurs, but studies suggest it was not as fast as the modern ostrich, which can travel at 69 kilometers per hour (43 miles per hour). Contrary to the Jurassic Park movies, all the research shows that tyrannosaurs were much slower still and could not outrun the fastest humans, let alone a speeding car.

Not only was original type specimen of Carnotaurus preserved in a death pose nearly complete, but there were skin impressions as well. Its scales were shaped like polygons that did not overlap, and they are scored with parallel grooves in many places. The scales of the head are not as regular as those of the body, with differences between the scales on the right and left side of the face. There were also long knob-like bumps on the skin running along the side of the neck, back, and tail in irregular rows. These may be condensed dermal armor, perhaps to protect its flanks against attacks. Like Coelophysis, the head of the original specimen of Carnotaurus is drawn backward on a curved neck, probably because the nuchal ligament along the back of the neck contracted when the animal died. There is no evidence of feathers in any of the skin impressions, contrary to the evidence we have that tyrannosaurs had feathers—although the preservation of Carnotaurus may just not be suitable for showing feathers.

Finally, what about the horns that gave Carnotaurus its name? There have been lots of arguments and suggestions about their use. The obvious feature is that they help in species recognition and perhaps in showing dominance in males, as they do in cattle, deer, and antelopes today. Some paleontologists argue that they were used in head butting or wrestling with other members of their own species. Combined with their powerful neck, the head wrestling idea is plausible, but their lightly built skulls were not strong enough to survive high-speed head butting as in rams. The horns have flattened surfaces on top suitable for horn-to-horn wrestling and pushing, and they are also fused to the skull strongly so could withstand the stresses of head wrestling. One suggestion is that the bony horn cores were covered by long outer sheaths made of keratin (like the horns of cattle and antelopes) which would have made good offensive weapons and may have been used to stab or injure prey. However, there are no known instances of animals using horns for predation because nearly all of the horned animals alive today are herbivores.

Carnotaurus comes from the latest Cretaceous of Argentina. As the largest predator of that time, Carnotaurus probably preyed on titanosaur sauropods as well as smaller prey, such as duck-billed dinosaurs and ankylosaurs. Indeed, most of the weird abelisaurs come from the Late Cretaceous, where they are known largely from Argentina.

However, there were several poorly known abelisaurs in India, and one of the oddest of all is from Madagascar. Known as Majungasaurus, it comes from the latest uppermost Cretaceous beds of that Gondwana remnant. Although Majungasaurus was first named and described based on fragments found by French paleontologists in 1896, recent discoveries by Field Museum scientists have produced much better material. Like other abelisaurs, Majungasaurus had a short and deep snout with relatively small teeth. However, instead of the paired horns of Carnotaurus, it had a dome of bone over the top of the skull, which was originally thought to be from a pachycephalosaur. Aucasaurus also had thick ridges of bone on the top if its skull. This suggests that head wrestling was a normal feature of all the abelisaurs, and the horns of Carnotaurus were mostly for head wrestling as well.

We have now seen the full spectrum of Gondwana predators (such as abelisaurs and carcharodontosaurs) and prey (especially titanosaurs).Next we look at the weirdest predators of all—so weird that they gave up carnivory altogether and became one of the few theropods to become herbivorous.

FOR FURTHER READING

Bonaparte, José F. “A Horned Cretaceous Carnosaur from Patagonia.” National Geographic Research 1, no. 1 (1985): 149–151.

Bonaparte, José F., Fernando E. Novas, and Rodolfo A. Coria. “Carnotaurus sastrei Bonaparte, the Horned, Lightly Built Carnosaur from the Middle Cretaceous of Patagonia.” Contributions in Science 416 (1990): 1–41.

Calvo, Jorge Orlando, and Rodolfo A. Coria. “New Specimen of Giganotosaurus carolinii (Coria & Salgado, 1995), Supports It as the Largest Theropod Ever Found.” Gaia 15 (1998): 117–122.

Carrano, Matthew T., and Scott D. Sampson. “The Phylogeny of Ceratosauria (Dinosauria: Theropoda).” Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 6, no. 2 (2008): 183–236.

Colbert, Edwin. Men and Dinosaurs: The Search in the Field and in the Laboratory. New York: Dutton, 1968.

Currie, Philip J. “Out of Africa: Meat-Eating Dinosaurs That Challenge Tyrannosaurus rex.” Science 272, no. 5264 (1996): 971–972.

Farlow, James, and M. K. Brett-Surman. The Complete Dinosaur. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999.

Fastovsky, David, and David Weishampel. Dinosaurs: A Concise Natural History, 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Holtz, Thomas R., Jr. Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages. New York: Random House, 2011.

Mazzetta, Gerardo V., Per Christiansen, and Richard A. Fariña. “Giants and Bizarres: Body Size of Some Southern South American Cretaceous Dinosaurs.” Historical Biology 16, no. 2 (2004): 71–83.

Mazzetta, Gerardo V., Richard A. Fariña, and Sergio F. Vizcaíno. “On the Palaeobiology of the South American Horned Theropod Carnotaurus sastrei Bonaparte.” Gaia 15 (1998): 185–192.

Naish, Darren. The Great Dinosaur Discoveries. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

Naish, Darren, and Paul M. Barrett. Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 2016.

Novas, Fernando E. The Age of Dinosaurs in South America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009.

Senter, Phil. “Vestigial Skeletal Structures in Dinosaurs.” Journal of Zoology 280 (2010): 60–71.

Sereno, Paul C., Didier B. Dutheil, M. Iarochene, Hans C. E. Larsson, Gabrielle H. Lyon, Paul M. Magwene, Christian A. Sidor, David J. Varricchio, and Jeffrey A. Wilson. “Predatory Dinosaurs from the Sahara and Late Cretaceous Faunal Differentiation.” Science 272 (1996): 986–991.

Sereno, Paul C., Jeffrey A. Wilson, and Jack L. Conrad. “New Dinosaurs Link Southern Landmasses in the Mid-Cretaceous.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 271, no. 1546 (2004): 1325–1330.

Therrien, François, and Donald M. Henderson. “My Theropod Is Bigger Than Yours…or Not: Estimating Body Size from Skull Length in Theropods.” Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27, no. 1 (2007): 108–115.

Tykoski, Ronald B., and Timothy Rowe. “Ceratosauria.” In The Dinosauria, 2nd ed., ed. David B. Weishampel, Peter Dodson, and Halszka Osmólska, 47–71. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

Weishampel, David B. Paul M. Barrett, Rodolfo A. Coria, Jean Le Loeuff, Xu Xing, Zhao Xijin, Ashok Sahni, Elizabeth M. P. Gomani, and Christopher R. Noto. “Dinosaur Distribution.” In The Dinosauria, 2nd ed., ed. David B. Weishampel, Peter Dodson, and Halszka Osmólska, 517–606. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

Wilford, John Noble. The Riddle of the Dinosaur. New York: Knopf, 1985.