TWO

Spain

138–422/756–1031

The Iberian peninsula, excepting the Christian kingdoms of the north

| ⊘ 138/756 | ‘Abd al-Raḥmān I b. Mu‘āwiya, Abu ‘1-Mutarrif al-Dākhil |

| ⊘ 172/788 | Hishām I b. ‘Abd al-Rahmān I, Abu 1-Walīd |

| ⊘ 180/796 | al-Ḥakam I b. Hishām I, Abu ’l-‘Āṣ |

| ⊘ 206/822 | ‘Abd al-Raḥmān II b. al-Ḥakam I, Abu ’l-Muṭarrif al-Mutawassiṭ |

| ⊘ 238/852 | Muḥammad I b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān II, Abū ‘Abdallāh |

| ⊘ 273/886 | al-Mundhir b. Muḥammad I, Abu ’1-Ḥakam |

| ⊘ 275/888 | ‘Abdallāh b. Muḥammad I, Abū Muḥammad |

| ⊘ 300/912 | ‘Abd al-Raḥmān III b. Muḥammad, Abu ’1-Muṭarrif al-Nāṣir |

| ⊘ 350/961 | ‘ al-Ḥakam II b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān III, Abu ’1-Muṭarrif al-Mustanṣir |

| ⊘ 366/976 | Hishām II b. al-Ḥakam II, Abu ’1-Walīd al-Mu’ayyad, first reign |

| ⊘ 399/1009 | Muḥammad II b. Hishām II, al-Mahdī, first reign |

| ⊘ 400/1009 | Sulaymān b. al-Ḥakam, al-Musta‘īn, first reign |

| ⊘ 400/1010 | Hishām II, second reign |

| ⊘ 403/1013 | Sulaymān, second reign |

| 407/1016 | ‘Alī Ibn Ḥammūd, al-Nāṣir, Ḥammūdid |

| ⊘ 408/1018 | ‘Abd al-Raḥmān IV b. Muḥammad, al-Murtaḍā |

| 408/1018 | al-Qāsim Ibn Ḥammūd, al-Ma’mūn, Ḥammūdid, first time |

| 412/1021 | Yaḥyā b. ‘Alī, al-Mu‘talī, Ḥammūdid, first time |

| 413/1023 | al-Qāsim, Ḥammūdid, second time |

| ⊘ 414/1023 | ‘Abd al-Raḥhmān V b. Hishām, al-Mustaẓhir |

| ⊘ 414/1024 | Muḥammad III b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān, al-Mustakfī, k. 416/1025 |

| 416/1025 | Yaḥyā, Ḥammūdid, second time |

| ⊘ 418–22/1027–31 | Hishām III b. Muḥammad, al-Mu‘tadd, d. 428/1036 Mulūk al-Ṭawā’if |

Arab and Berber troops crossed over the Straits of Gibraltar from Morocco to Spain in 92/711 and speedily overthrew the Visigoths, the Germanic military aristocracy who had ruled Spain until then. Over the next decades, the Muslim forces drove the remnants of the Visigoths into the Cantabrian Mountains of the extreme north of the Iberian peninsula, and even penetrated across the Pyrenees into Frankish Gaul, until Charles Martel defeated them just to the north of Poitiers, in the battle called by the Arabs that of Balāṭ al-Shuhadā’, in 114/732. During these early years, Spain was ruled by a succession of Arab governors sent out from the east, as the most westerly province of the Islamic empire, called in the Arabic sources al-Andalus (almost certainly notfrom *Vandalicia, the land of the Vandals, whose passage through Spain over two centuries before had left virtually no traces, but more probably from a Germanic expression meaning ’share, parcel of land‘). But in 138/756,‘Abd al-Raḥmān I, later called al-Dākhil‘the Incomer‘, and one of the few Umayyads to have escaped slaughter in the ‘Abbāsid Revolution, appeared in Spain and founded the Umayyad amirate there.

In a peninsula where the facts of geography militated against central control and firm rule, the establishment of the Umayyad state was an achievement indeed. The amirate was based on Seville (Ishbīliya) and Cordova (Qurṭuba), but the Amīrs‘ hold on the outlying provinces was less secure. Although a good proportion of the Hispano-Roman population became Muslim (theMuwalladūn), a substantial number remained Christian (the Musta‘rabūn, Mozarabs), and looked to the independent Christian north for moral and religious support. In particular, Toledo (Ṭulayṭila), the ancient capital of the Visigoths and the ecclesiastical centre of Spain, was a centre of rebelliousness. Among the Muslims, there were many local princes whose military strength as marcher lords enabled them to live virtually independently of the capital Cordova; these flourished above all in the Ebro valley of the north-east, the later Aragon and Catalonia (e.g. the Tujībids of Saragossa and the Banū Qasī of Tudela). In the later ninth century, there were two centres of prolonged rebellion against the central government by its own Muslim subjects, one around Badajoz under Ibn Marwān the Galician, and the other in the mountains of Granada under Ibn Ḥafṣūn.

Despite these weaknesses, and despite the continued existence of the petty Christian kingdoms of the north, the Spanish Umayyads made Cordova a remarkable centre of craft industries and trade, and as a home for Arabic culture, learning and artistic production it was inferior only to Baghdad and Cairo. The tenth century was dominated by ‘Abd al-Raḥmān III, called al-Nāṣir ‘the Victorious‘, who reigned for fifty years (300–50/912–61). He raised the power of the monarchy to a new pitch; court ceremonial was made more elaborate, possibly with Byzantine practice in mind, and ‘Abd al-Raḥmān countered the pretensions of his enemies the Fāṭimids by himself adopting the titles of Caliph and Commander of the Faithful in place of the simple previous designation of Amīr. In this way, the rather vague ideological basis of the state, which had prevailed for over 150 years – in which the Umayyads had never been able to decide whether they were still a part, albeit peripheral, of the Islamic oecumene, or whether they were ruling over a localised, Iberian principality, Muslim in faith but turned inwards politically – was relinquished. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān now clearly set aside the doctrine of orthodox religious theory that the caliphate was one and indivisible. No longer relying primarily on the Andalusian Arab jundsor territorially-based military contingents, the Caliph built up the army‘s strength with fresh Berber tribesmen from North Africa and with slave troops brought from various parts of Christian Europe (the Ṣaqāliba). The Christians of the north were humbled and an anti-Fāṭimid policy pursued in North Africa. But after the death of al-Hakam II in 366/976, the succession devolved on minors and weaker candidates, so that real power in the state passed to the Ḥājibor chief minister Ibn Abī ‘Amir, called al-Manṣūr ‘the Victorious‘ (the Almanzor of Christian sources); it was he who captured Barcelona and who on one occasion sacked the shrine of St James of Compostella in Galicia.

Yet early in the eleventh century, the ‘Āmirid Ḥājibslost control and the Umayyad caliphate fell apart. Possible reasons for this have been much discussed by historians. It has been argued, for instance, that the numbers of Muslims in al-Andalus had increased by conversion from Christianity in ‘Abd al-Raḥmān III’s reign so that the Muslims were perhaps for the first time a majority there and felt a new confidence from this strength and a greater feeling of control over the land; hence they no longer saw the necessity of a strong, central government as vital for the preservation of Islam in the Iberian peninsula. If this was the case, such confidence was misplaced. The last, ephemeral Umayyads could not maintain the primacy in the state of the old Andalusian Muslims, essentially Arabs and Muwalladūn, in face of the military strength of the Berbers and ṣaqāliba. Their short reigns alternated with periods of rule by the Berberised Arab Ḥammūdids, local rulers in Malaga, Ceuta, Tangier and Algeciras (see below, no. 5, Taifas nos 1, 2). The Umayyads finally disappeared in 422/1031, and Muslim Spain fell into a period of political fragmentation, in the course of which various local chiefs and ethnic groups held power (the age of the Mulūk al-Ṭawā’ifor Reyes de Taifas: see below, no. 5); not until the coming of the Almoravids (see below, no. 14) at the end of the century did al-Andalus experience unity again.

Lane-Poole, 19–22; Zambaur, 3–4 and Table F; Album, 13–14.

EI1‘Umaiyads. II’ (E. Lévi-Provençal).

G. C. Miles, The Coinage of the Umayyads of Spain, ANS Hispanic Numismatic Series, Monographs, no. 1, New York 1950.

E. Lévi-Provençal, Histoire de l’spagne musulmane, Paris 1950–67, I–II, with Table at II, 346.

5

THE MULŪK AL-ṬAWĀ’lF OR REYES DE TAIFAS IN SPAIN

Fifth to early seventh century/eleventh to early thirteenth century

Central and southern Spain, Ceuta and the Balearic Islands

The seventy or eighty years or so between the end of the line of ‘Āmirid Ḥājibsand the coming of the Almoravids saw the final collapse of the Umayyad dynasty and the formation of local principalities across Muslim Spain; yet, as has not infrequently happened in world history, political fragmentation was accompanied by great cultural brilliance.

The process began in the post-‘Āmirid period of fitnaor chaos, well before the disappearance of the Umayyads in 422/1031, with the main Taifa principalities firmly established by then. The former capital Cordova was never able to establish more than a local authority during these decades of the Taifas. Instead, there arose a mosaic of local powers, whose geographical centres David Wasserstein has listed as amounting to in effect thirty-nine, as follows (in alphabetical order):

| 1. | Algeciras/al-Jazīra al-Khaḍrā‘ (the Ḥammūdids) |

| 2. | Almería/al-Mariya (the Banū Ṣumādiḥ) |

| 3. | Alpuente/al-Bunt (the Banu ’1-Qāsim) |

| 4. | Arcos/Arkush (the Banū Khazrūn) |

| 5. | Badajoz/Baṭalyaws (the Afṭasids) |

| 6. | Baza/Basṭa |

| 7. | Calatayud/Qal‘at Ayyūb (the Hūdids) |

| 8. | Calatrava/Qal‘at Rabāḥ |

| 9. | Carmona/Qarmūna (the Banū Birzāl) |

| 10. | Ceuta/Sabta (the Ḥammūdids) |

| 11. | Cordova/(Qurṭuba (the Jahwarids) |

| 12. | Denia/Dāniya (the Banū Mujāhid) |

| 13. | Majorca/Mayūrqa and the Balearic Islands/al-Jazā’ir al-Sharqiyya (the Banū Mujāhid and then governors for the North African dynasties and independent rulers of the Banū Ghāniya: see below, no. 6) |

| 14. | Granada/Gharnāṭa (the Zīrids) |

| 15. | Huelva/Walba or Awnaba and Saltes/Shaltīsh |

| 16. | Huesca/Washqa (the Hūdids) |

| 17. | Jaén/Jayyān |

| 18. | Lérida/Lārida (the Hūdids) |

| 19. | Majorca/Mayūrqa (the Banū Mujāhid) |

| 20. | Málaga/Mālaqa (the Ḥammūdids) |

| 21. | Medinaceli/Madīnat Sālim |

| 22. | Mértola/Martula |

| 23. | Morón/Mawrūr (the Banū Nūḥ) |

| 24. | Murcia/Mursiya (various rulers, including the Ṭāhirids) |

| 25. | Murviedro/Murbayṭar |

| 26. | Niebla/Labia and Gibraleón/Jabal al-‘Uyūn (the Yaḥṣubids) |

| 27. | Ronda/Runda |

| 28. | La Sahla or Albarracin/al-Sahla (the Banū Razín) |

| 29. | Santa Maria de Algarve/Shantamariya al-Gharb or Ocsonoba/Ukshūnuba (the Banū Hārūn) |

| 30. | Saragossa/Saraqusṭa (the Tujībids and then Hūdids) |

| 31. | Segura/Shaqūra |

| 32. | Seville/Ishbīliya (the ‘Abbādids) |

| 33. | Silves/Shilb (the Banū Muzayn) |

| 34. | Toledo/Ṭulayṭūa (the Dhu ’l-Nūnids) |

| 35. | Tortosa/Ṭurṭūsha |

| 36. | Tudela/Tuṭīla (the Hūdids) |

| 37. | Valencia/Balansiya (the ‘Āmirids) |

| 38. | Vilches/Bilj |

| 39. | Ḥiṣn al-Ashrāf |

Some of these, especially in the more prosperous and settled south, south-east and east, were little more than city states, but others, like the Afṭasids of Badajoz in the south-west of the peninsula, the Dhu ’1-Nūnids of Toledo, on the far northern edge of Muslim territory, and the Hūdids in the Ebro valley, ruled large tracts of territory. The dynasties were of varying official background and race, reflecting the trends of later Umayyad times and of the ethnic rivalries of the various groups. Several sprang out of the old ‘Āmirid military élite and their clients. Some were from long-established Arab families, like the ‘Abbādids of Seville, the Banū Qāsim of Alpuente and the Hūdids of Saragossa. Others were Berber, like the Miknāsa Afṭasids and the Ḥawwāra Dhu ’1-Nūnids (whose original name was the Berber one of Zennun), or were Berberised Arabs like the Ḥammūdids (ultimately of Idrīsid origin) of Algeciras, Ceuta and Málaga; in several cases, these Berber Taifas sprang from the great influx of troops from North Africa brought about by Ibn Abī ‘Āmir towards the end of the tenth century, such as the Sanhāja Zīrids in Granada. In certain towns of the south-east and east, Ṣaqlabī commanders seized power, such as the initial rulers in Almeria, Badajoz, Murcia, Valencia and Tortosa, although the role of the Ṣaqāliba in Spain tended to fade out after the mid-eleventh century.

The larger Taifas pursued aggressive policies at the expense of their neighbours. The ‘Abbādids expanded almost to Toledo, and to further their designs at one stage resuscitated a man who claimed to be the last Umayyad caliph, Hishām III, thought to have died in obscurity after his deposition. Several of the Taifas were quite content to intrigue with or even to call in the Christians against their fellow-Muslims; the last Afṭasid, ‘Umar al-Mutawakkil, was ready, after the arrival in Spain of the Almoravids, to cede his possessions in central Portugal to Alfonso VI of Léon and Castile in return for help against the threatening Berber power.

Towards the end of the eleventh century, the tide was clearly flowing against the Muslims in Spain, a complete reversal of the situation a century or so before when the weak, petty kingdoms of northern Spain had paid tribute to the mighty Cordovan caliphate; now many of the Taifas were paying tribute, parias, to the Christian states and were in varying relations of vassalage to them. Toledo fell to Alfonso in 478/1085 as much through internal dissensions as through external attack. Appeals to the greatest Muslim power in the West, the Almoravids of Mauritania and Morocco, both from Taifa rulers and from the religious classes in Spain, seemed to be the only way out, but the victory of the Almoravids at Sagrajas or al-Zallāqa in 479/1086 proved to be the prelude to the sweeping-away of almost all the Taifas within a few years, the Hūdids in Saragossa alone preserving a tenuous independence until 503/1110.

In the interval between the collapse of Almoravid power in Spain and the assertion of Almohad control there after 540/1145 (see below, nos. 14, 15), shortlived Taifas were constituted in some places, e.g. at Valencia, Cordova, Murcia and Mértola; and after the decline of Almohad authority in Spain, local commanders were able to seize power in certain places, for example at Valencia, Niebla and, somewhat more enduringly, Murcia, until these towns were recovered by the Christians.

| ⊘ 404/1014 | or |

| 405/1015 | ‘Alī b. Ḥammūd, al-Nāṣir |

| ⊘ 408/1017 | al-Qāsim b. Ḥammūd, al-Ma’mūn, first reign |

| ⊘ 412/1021 | Yaḥyā I b. ‘Alī, al-Mu‘talī, first reign |

| 413/1022 | al-Qāsim I, second reign |

| 417/1026 | Yaḥyā I al-Mu‘talī, second reign |

| ⊘ 427/1036 | Idrīs I b. ‘Alī, al-Muta’ayyad |

| 431/1039 | Yaḥyā II b. Idrīs, al-Qā’im |

| ⊘ 431/1040 | al-Ḥasan b. Yāhyā I, al-Mustanṣir |

| ⊘ 434/1043 | Idrīs II b. Yahyā I, al-‘Alī, first reign |

| ⊘ 438/1046 | Muḥammad I b. Idrīs, al-Mahdī |

| 444/1052 | Idrīs III b. Yaḥyā II, al-Sāmī al-Muwaffaq |

| ⊘ 445/1053 | Idrīs II al-‘Alī al-Ẓāfir, second reign |

| ? to 448/1056 | Muḥammad II b. Idrīs, al-Musta‘lī |

The main Ḥammūdid line in Málaga extinguished by the Zīrids of Granada, the branch in Alcegiras being extinguished also in 446/1054 or 451/1059 by the ‘Abbādids of Seville. |

| 400/1010 | ‘Alī b. Ḥammūd, al-Nāṣir |

| 408/1017 | al-Qāsim b Ḥammūd, al-Ma’mūn |

| 412/1021 |

|

| or 414/1023 |

|

| to 427/1036 | Yaḥyā I b. ‘Alī, al-Mu‘talī |

| 426/1035 | Idrīs I b. ‘Alī, al-Muta’ayyad |

| 431/1039 | Yaḥyā II b. Idrīs, al-Qā’im |

| 431/1040 | Ḥasan b. Yaḥyā I, al-Mustanṣir |

| c. 442/c. 1050 | Idrīs II b. Yaḥyā I, al-‘Alī |

| by 453/1061 | Governors for the Ḥammūdids and then independent rulers from the Barghawāṭa Berbers |

| 414/1023 | Muḥammad I b. Ismā‘īl Ibn ‘Abbād, Abu ’1-Qāsim, initially as member of a triumvirate |

| ⊘ 433/1042 | ‘Abbād b. Muḥammad I, Abu ‘Amr Fakhr al-Dawla al-Mu‘tadiḍ |

| ⊘ 461–84/1069–91 | Muḥammad II b. ‘Abbād, Abu ’1-Qāsim al-Mu‘tamid, d. 487/1095 |

| 484/1091 | Almoravid conquest |

| 414/1023 | Muḥammad b. ‘Abdallāh al-Birzālī, Abū ‘Abdallāh |

| 434/1043 | Isḥāq b. Muḥammad |

| 444–59/1052–67 | al-‘Azīz or al-‘Izz b. Isḥāq, al-Mustaẓhir |

| 459/1067 | ‘Abbādid annexation |

| 402/1012 | Muḥammad Ibn Khazrūn, Abū ‘Abdallāh ‘Imād al-Dawla |

| ? | ‘Abdūn Ibn Khazrūn |

| 448–58/1056–66 | Muḥammad b.‘Abdūn |

| 459/1067 | ‘Abbādid annexation |

| 403/1013 | Zāwl b. Zīrī al-Ṣanhājī |

| 410/1019 | Ḥabbūs b. Māksan |

| ⊘ 429/1038 | Bādīs b. Ḥabbūs, al-Muẓaffar al-Nāṣir |

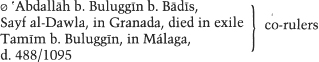

| 465–83/1073–90 |

|

| 483/1090 | Almoravid conquest |

7. The Banū Ṣumādiḥ of Almería

| c. 403/c. 1013 | Khayrān al-Ṣaqlabī |

| 419/1028 | Zuhayr al-Ṣaqlabī |

| 429–33/1038–42 | ‘Abd al-‘Azīz b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān Ibn Abī ‘Āmir, al-Manṣūr of Valencia |

| 429/1038 | Governors from the Banū Ṣumādiḥ for the ‘Āmirids of Valencia |

| 433/1042 | Ma‘n b. Muḥammad Ibn Ṣumādiḥ |

| ⊘ 443/1051 | Muḥammad b. Ma‘n, Abū Yaḥyā al-Mu‘taṣim |

| 484/1091 | Aḥmad b. Muḥammad, Mu‘izz al-Dawla, died in exile |

| 484/1091 | Almoravid conquest |

8. The Banū Mujāhid of Denia and Majorca

| ⊘ c. 403/c. 1012 | Mujāhid b. ‘Abdallāh al-‘Āmirī, al-Muwaffaq |

| ⊘ 436–68/1045–76 | ‘Alī b. Mujāhid, Iqbāl al-Dawla |

| 468/1076 | Annexation by the Hūdids |

9. The rulers in Majorca during the eleventh and early twelfth centuries

| 405–68/1015–76 | Governors of the Banū Mujāhid of Denia |

| ⊘ 468/1076 | ‘Abdallāh al-Murtaḍā |

| ⊘ 486–508/ |

|

| 1093–1114 | Mubashshir b. Sulaymān, Nāṣir al-Dawla |

| 508/1114 | Almoravid annexation |

| 422/1031 | Jahwar b. Muḥammad Ibn Jahwar, Abu ’1-Ḥazm, formally as member of a triumvirate |

| ⊘ 435/1043 | Muḥammad b. Jahwar, Abu ’1-Walīd al-Rashīd |

| 450–61/1058–69 | ‘Abd al-Malik b. Muḥammad, Dhu ’1-Siyādatayn al-Manṣur al-ẓāfir, died in exile |

| 461/1069 | ‘Abbādid conquest |

11. The rulers in Cordova of the Almoravid-Almohad interregnum

| ⊘ 538/1144 | Ḥamdīn b. Muḥammad, al-Manṣūr, first reign |

| ⊘ 539/1145 | Aḥmad III b. ‘Abd al-Malik, Sayf al-Dawla, Hūdid, d. 540/1146 |

| 540/1146 | Ḥamdīn b. Muḥammad, second reign |

| 541/1146 | Yaḥyā b. ‘Alī, Ibn Ghāniya |

| 543/1148 | Almohad conquest |

| 403/1012–13 | Sābūr al-Ṣaqlabī |

| 413/1022 | ‘Abdallāh b. Muḥammad Ibn al-Afṭas, Abū Muḥammad al-Manṣūr |

| 437/1045 | Muḥammad b. ‘Abdallāh, Abū Bakr al-Muẓaffar |

| ⊘ 460/1068 | Yaḥyā b. Muḥammad |

| ⊘ 460–87/1068–94 | ‘Umar b. Muḥammad, Abū Ḥafṣ al-Mutawakkil, k. 487/1094 or 488/1095 |

| 487/1094 | Almoravid conquest |

13. The Dhu ’1-Nūnids of Toledo

| c. 403/c. 1012 | Ya‘īsh b. Muḥammad, Abū Bakr al-Qāḍi |

| ⊘ 409/1018 | Ismā‘īl b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān Ibn Dhi ’1-Nūn, Abū Muḥammad Dhu ’1-Riyāsatayn al-Ẓāfir |

| ⊘ 435/1043 | Yaḥyā I b. Ismā‘īl, Abu ’1-Ḥasan Sharaf al-Dawla al-Ma’mūn Dhu ’1-Majdayn |

| ⊘ 467/1075 | Yaḥyā II b. Ismā‘īl b. Yaḥyā I, al-Qādir, first reign |

| 472/1080 | Occupation by the Afṭasid ‘Umar al-Mutawakkil |

| ⊘ 473–8/1081–5 | Yaḥyā II al-Qādir, second reign, k. 485/1092 |

| 478/1085 | Conquest by Alfonso VI of León and Castile, with Yaḥyā installed in Valencia as a puppet ruler |

| 401/1010–11 | Mubārak al-Ṣaqlabī and Muẓaffar al-Ṣaqlabī |

| 408 or 409/1017–18 | Labīb al-Ṣaqlabī |

| ⊘ 411/1020 |

|

| or 412/1021 | ‘Abd al-‘Azīz b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān (Sanchuelo) Ibn Abī ‘Āmir, al-Manṣūr |

| ⊘ 452/1060 | ‘Abd al-Malik b. ‘Abd al-‘Azīz, Niẓām al-Dawla al-Muẓaffar |

| 457–68/1065–76 | Dhu ’1-Nūnid occupation |

| 468/1076 | Abū Bakr b. ‘Abd al-‘Azīz, al-Manṣūr |

| 478/1085 | ‘Uthmān b. Abī Bakr, al-Qāḍī |

| 478–85/1085–92 | Dhu ’1-Nūnid Yaḥyā b. Ismā‘lī al-Qādir installed as puppet ruler by Alfonso VI |

| 487–92/1094–9 | Valencia occupied by the Cid |

| 495/1102 | Almoravid conquest |

15. The rulers in Valencia of the Almoravid-Almohad interregnum

| 539/1144 | Manṣūr b. ‘Abdallāh, Qāḍī |

| ⊘ 542/1147 | Abū‘Abdallāh Muḥammad b.Sa‘d, Ibn Mardanlsh, Rey Loboor Lope |

| 567/1172 | Hilālb.Muḥammad, Ibn Mardanīsh, submitted to the Almohads |

| 400/1010 | al-Mundhir I b. Yaḥyā al-Tujībī, governor for the Umayyads |

| ⊘ 414/1023 | Yaḥyā b. al-Mundhir I, al-Muẓaffar |

| ⊘ 420/1029 | al-Mundhir II b. Yaḥyā, Mu‘izz al-Dawla al-Manṣūr |

| ⊘ 430–1/1039–40 | ‘Abdallāh b. al-Ḥakam, al-Muẓaffar |

| 431/1040 | Succession of the Hūdids |

17. The Hūdids in Saragossa, Huesca, Tudela and Lérida, and, subsequently, Denia, Tortosa and Calatayud

18. The rulers of Murcia, including the Ṭāhirids and Hūdids

| 403/1012–13 | Khayrān al-Ṣaqlabī of Almería |

| 419/1028 | Zuhayr al-Ṣaqlabī of Almería |

| 429/1038 | ‘Abd al-‘Azīz b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān Ibn Abī ‘Āmir, al-Manṣūr, of Valencia |

| 436/1045 | Mujāhid b. ‘Abdallāh al-‘Āmirī of Denia |

| c. 440/c. 1049 | Aḥmad, Abū Bakr Ibn Ṭāhir |

| 455/1063 | Muḥammad b. Aḥmad Ibn Ṭāhir |

| 471/1078 | Governors on behalf of the Abbādids of Seville |

| 484/1091 | Almoravid conquest |

| 489–90/1096–7 | Aḥmad b. Abī Ja‘far ‘Abd al-Raḥmān Ibn Ṭāhir, Abū Ja‘far Resumption of Almoravid control |

| 540/1145 | ⊘ ‘Abdallāh b. ‘Iyāḍ and ⊘ ‘Abdallāh b. Faraj al-Thaghrī as rivals for power |

| ⊘ 543/1148 | Muḥammad b. Sa‘d, Abū ‘Abdallāh Ibn Mardanīsh, Rey Loboor Lope, of Valencia |

| 567/1172 | Almohad occupation |

| ⊘ 625/1228 | Muḥammad b. Yūsuf Ibn Hūd, Abū ‘Abdallāh al-Mutawakkil, also in Valencia till the Christian reconquest of Valencia in 636/1238 |

| ⊘ 635/1238 | Muḥammad b. Muḥammad, Abū Bakr al-Wāthiq, first reign |

| 636/1239 | al-‘Azīz b. ‘Abd al-Malik, Diyā‘ al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 638/1241 | Muḥammad Ibn Hūd, Abū Ja‘far Bahā‘ al-Dawla |

| 660/1262 | Muḥammad b. Abī Ja‘far Muḥammad |

| 662/1264 | Muḥammad b. Muḥammad, Abu Bakr, second reign |

| ? | ‘Abdallāh b. ‘Alī, Ibn Ashqīlūla, of the Naṣrids of Granada |

| (664/1266 | Aragonese conquest) |

Zambaur, 53–8 and Map 1; Lane-Poole, 23–6; Album, 14–15.

A. Prieto y Vives, Los Reyes de Taifas, estudio histórico-numismático de los Musulmanes españoles en el siglo V de la Hégira (XI de J.C.), Madrid 1926.

H. W. Hazard, The Numismatic History of Late Medieval North Africa,ANS Numismatic Studies, no. 8, New York 1952, 57–8, 96, 233–6, 281–2 (for the Ḥammūdids of Málaga, Algeciras and Ceuta), 68–9, 158–9, 272–3 (for the later Hūdids of Murcia and Ceuta).

G. C. Miles, Coins of the Spanish Mulūk al-Ṭawā‘if,ANS Hispanic Numismatic Series, Monographs, no. 3, New York 1954.

D. Wasserstein, The Rise and Fall of the Party Kings. Politics and Society in Islamic Spain 1002–1086, Princeton 1985.

EI1 art. ‘Tudjīb (Banū)’, ‘Zīrids’ (E. Lévi-Provençal)

EI2arts’ ‘Abbādids’, ‘Aftasids’, ‘Balansiya’ (Lévi-Provençal), ‘Dhu ’1-Nūnids’ (D. M. Dunlop), ‘Djahwarids’, ‘Ḥammūdids’ (A. Huici Miranda), ‘Hūdids’ (Dunlop), ‘Ibn Mardanīsh’, ‘Ḳarmūna’, ‘Mayūrḳa’ (J. Bosch-Vilá), ‘Saraḳusṭa’ (M. J. Viguera).

520–99/1126–1203

The Balearic Islands

| 520/1126 | Muḥammad b. ‘Alī b. Yūsuf al-Massūfī, Ibn Ghāniya, governor of the Balearios for the Almoravids |

| 550/1155 | ‘Abdallāh b. Muḥammad |

| 550/1155 | Abū Ibrāhīm Isḥāq b. Muḥammad |

| 579/1183 | Muḥammad b. Isḥāq, under Almohad suzerainty |

| 580/1184 | ‘Alī b. Ishāq |

| 583–600/1187–1203 | ‘Abdallāhb. Isḥāq |

| 600/1203 | Almohad occupation of the Balearics, and Almohad governors |

| 627–8/1230–1 | Aragonese conquest of Majorca |

The founder of this petty Ṣanhāja Berber dynasty, which controlled the Balearic Islands for eighty years and also played a significant role during the period of later Almohad rule in the eastern Maghrib, was an Almoravid descendant on the female side, deriving his name Ibn Ghāniya from the name of an Almoravid princess, the wife of ‘Alī b. Yūsuf. ‘Alī’s son Yaḥyā defended the Almoravid possessions in Spain against the incoming Almohads (see below, no. 15), and then remnants of the Ibn Ghāniya family withdrew to the Balearic Islands. There they founded their own independent line as a post-Almoravid principality which grew rich on, inter alia, piracy against the Christians. One member of the family, ‘Alī b. Isḥāq, decided to leave the Balearics and carry on the struggle against the Almohads in the eastern Maghrib. He and his successor there, Yaḥyā b. Isḥāq, were for several decades destabilising influences in the affairs of Ifrīqiya and what is now eastern Algeria until ‘Alī’s defeat and death in 633/1227 and Yaḥyā’s loss of Ifrīqiya and subsequent death in 635/1236; the activities here of the Banū Ghāniya were a potent factor in the decline of Almohad power in the eastern Maghrib. Meanwhile, the Almohad caliph al-Nāṣir had invaded Majorca and installed his own governor there, ending the rule of the Banū Ghāniya in the Balearics; the Almohads and their epigoni held the islands for nearly thirty years until James I of Aragön conquered Majorca, with Ibiza and Minorca following it into Christian hands by 686/1287.

Zambaur, 57.

EI2 ‘Ghāniya, Banū’ (G. Marçais); ‘Mayūrka’ (J. Bosch-Vilá).

A. Bel, Les Benou Ghânya, derniers représentants de 1’empire almoravide et leur lutte contre l’empire almohade, Publications de l’Ecole des Lettres d’Alger, Bull. de Correspondance Africaine, XXVII, Paris 1903, with a genealogical table at p. 26.

629–897/1232–1492

Granada

After the Almohads (see below, no. 15) were defeated in Spain, most of the Muslim towns fell speedily into Christian hands: Cordova fell in 633/1236 and Seville in 646/1248. One Muslim chief, Muḥammad (I) al-Ghālib, who claimed descent from a Medinan Companion of the Prophet, managed to gain control of the mountainous and thus defensible extreme south of the Iberian peninsula covering the present provinces of Granada, Málaga and Almería with parts of Cádiz, Jaén and Murcia. He made Granada his capital and its citadel, known as the Alhambra (al-Ḥamrā’‘the Red [fortress]’), his centre, agreeing to pay pañasor tribute first to Ferdinand III of Castile and León and then to his successor Alfonso X. The Naṣrid sultans were rivals with the Marmids of Morocco (see below, no. 16) for control of the Straits of Gibraltar, and Muḥammad I and Muḥammad V actually controlled Ceuta during 705–9/1305–9 and 786–9/1384–7, minting coins there. But they eventually had to seek help from the Marīnids against pressure from the Christian kingdoms of Castile and Aragön; yet Muslim hopes of successful Marīnid intervention in the Iberian peninsula were dashed when the Marinīd sultan Abu ’1 Hasan ‘Alī and the Naṣrid sultan Yūsuf I were defeated by the Castilians and Portuguese at the battle of Tarifa (known in Christian sources as that of the Rio Salado) in 741/1340.

Despite its precarious position, partly because of instability and disturbances within the kingdom of Castile-Léon, the Naṣrid sultanate remained for two and a half centuries a centre for Islamic civilisation, attracting scholars and literary men from all over the Muslim West. The historian Ibn Khaldūn served as a diplomat for Muḥammad V on a mission to Pedro I of Castile at Seville, and in the vizier Lisān al-Dīn Ibn al-Khaṭīb, whose history of Granada is a source of prime importance, Naṣrid Granada produced a major literary figure. But in the fifteenth century the internal unity of Granada was impaired by internecine rivalries among the ruling family, aided and abetted by powerful families like that of the Banu ’1-Sarrāj (the ‘Abencerrajes’). The marriage of Ferdinand II of Aragön (subsequently Ferdinand V of Castile-Aragon) to Isabella of Castile in 1469 brought about the unification of the greater part of Christian Spain under one crown, and the prospects for the sultanate’s survival darkened. Dynastic strife grew worse under the last Naṣrids, until in 897/1492 Granada was handed over to the Christians by Muḥammad XII (Boabdil), who remained as lord of Mondújar and the Alpujarras for one year and some months before crossing over to Morocco.

The history and the chronology of the last Naṣrid amīrs are extremely confused; where Christian era dates alone are given in the above list of rulers, this indicates that the chronology has to be constructed from Christian sources alone and that regnal dates are not provided by the Arabic ones.

Lane-Poole, 28–9; Zambaur, 58–9; Album, 15.

The lists of Lane-Poole and Zambaur are, in our present state of knowledge, very inaccurate and misleading. See now EI2 ‘Nasrids’ (J. D. Latham), with a much more accurate chronology, utilising the standard histories of Rachel Arié, L’Espagne musulmane au temps des Naṣrides (1232–1492), enlarged 2nd edn, Paris 1990, with table after plate XII; eadem, El reino naṣrí de Granada, Madrid 1992; and L. P. Harvey, Islamic Spain 1250–1500, Chicago and London 1990, with tables at pp. 17–19.

F. Codera y Zaydín, Tratado de numismática arábigo-española, Madrid 1879.

A. Vives y Escudero, Monedas de las dinastías arábigo-españolas, Madrid 1893.

H. W. Hazard, The Numismatic History of Late Medieval North Africa, 84–5, 228, 279, 285 (for coins minted by the Naṣrids at Ceuta).

M. A. Ladero Quesada, Granada, historia de un país islámico (1232–1571), 2nd edn, Madrid 1979.

J. J. Rodriguez Lorente, Numismática nasrí, Madrid 1983.