THREE

North Africa

172–375/789–985

Morocco

| ⊘ 172/789 | Idrīs I (al-Akbar) b. ‘Abdallāh |

| (175/791 | Regency for his posthumous son Idrīs) |

| ⊘ 187/803 | Idrīs II (al-Aṣghar or al-Azhar) b. Idrīs I |

| ⊘ 213/828 | Muḥammad b. Idrīs II, al-Muntaṣir |

| ⊘ 221/836 | ‘Alī I Ḥaydara b. Muḥammad |

| ⊘ 234/849 | Yaḥyā I b. Muḥammad |

| ⊘ 249/863 | Yaḥyā II b. Yaḥyā I |

| ⊘ 252/866 | ‘Alī II b. ‘Umar |

| ? | Yaḥyā III b. al-Qāsim, al-Miqdām al-Jūṭī |

| 292/905 | Yaḥyā IV b. Idrīs, deposed in 307/919 |

| 305/917 onwards | Tributary to the Fāṭimids, with the Fāṭimid governor Mūsā b. Abi ’1-‘Āfiya installed |

| 313–15/925–7 | al-Ḥasan b. Muḥammad, al-Ḥajjām |

| 326/938 | al-Qāsim Gannūn b. Muḥammad (at Ḥajar al-Naṣr, in the Rīf and north-western Morocco) |

| 337/948 | Aḥmad b. al-Qāsim, Abu ’l-‘Aysh (at Aṣīlā) |

| 343–63/954–74 | al-Ḥasan b. al-Qāsim (at Ḥajar al-Nasr), first reign |

| 375/985 | al-Ḥasan, second reign, k. 375/985 |

| 375/985 | Incorporation of the Western Maghrib into the Fāṭimid empire |

The Idrīsids were the first dynasty who attempted to introduce the doctrines of Shī‘ism, albeit in a very attenuated form, into the Maghrib, where the most vigorous form of Islam, – in a region where there was still much paganism and Christianity surviving – was that of the radical and egalitarian Khārijism. Idrīs I was a great-grandson of al-Ḥasan b. ‘Alī b. Abī Ṭālib, hence connected with the line of Shī‘ī Imāms. He took part in the ‘Alid rising in the Ḥijāz of his nephew al-Ḥusayn, the ṣāḥib Fakhkh, against the ‘Abbāsids in 169/786, and was compelled to flee to Egypt and then to North Africa, where the prestige of his ‘Alid descent led several Zanāta Berber chiefs of northern Morocco to recognise him as their leader. There he settled at Walīla, the Roman Volubilis, but it seems that he also began the laying-out of a military camp, Madīnat Fās, nucleus of the later city of Fez. This last soon grew populous, attracting emigrants from Muslim Spain and Ifrīqiya, the eastern Maghrib, and became the Idrīsids’ capital. Its role as a holy city, home of the Shorfā (<shurafā’ ‘noble ones’), privileged descendants of the Prophet’s grandsons al-Hasan and al-Ḥusayn, also begins now, and henceforth these Shorfā play an important role in Moroccan history (see below, nos 20, 21). The Idrīsid period is also important for the diffusion of Islamic culture over the recently-converted Berber tribesmen of the interior.

However, during the reign of Muḥammad al-Muntaṣir, the Idrīsid dominions became politically fragmented as a result of his decision to divide out the family’s various towns – the Idrīsids’ hold on Morocco was essentially urban-based rather than on the countryside – as appanages for several of his numerous brothers. The Idrīsids thus fell prey to attacks from their Berber enemies, but in the early tenth century a more determined and dangerous foe appeared in the shape of the radical Shī‘ī Fāṭimids of Ifrīqiya. Yaḥyā IV had to recognise the suzerainty of the Mahdī ‘Ubaydallāh, and much of his territory was detached and given to the Miknāsa Berber chief Mūsā b. Abi ’l-‘Afiya. The Idrīsids were subsequently driven to the peripheries of Morocco, so that there were minor branches at places like Tamdult in the south, but the main line was established among the Ghumāra Berbers in the Rīf of northern Morocco. These last gave their allegiance variously to the Spanish Umayyads, who were now, under their caliph ‘Abd al-Rahmān III, attempting to extend their influence in North Africa, and to the Fāṭimids. In 353/974, the Idrīsid al-Ḥasan had to surrender to the Umayyads and was carried off to Cordova. Some years later, he managed to reappear, with Fāṭimid support, but was killed by Umayyad forces and the Idrīsid dynasty in North Africa ended.

However, during the period of Umayyad decadence in the early eleventh century, a distant branch of the Idrīsids, the Ḥammūdids, succeeded in establishing Taifa principalities in Málaga and Algeciras (see above, no. 5, Taifas nos 1, 2).

Lane-Poole, 35; Zambaur, 65 and Table 4; Album, 15.

EI2 ‘Idrīs I,’ ‘Idrīs II,’ ‘Idrīsids’ (D. Eustache).

H. Terrasse, Histoire du Maroc des origines à 1’établissement du Protectorat français, Casablanca 1949–50, I, 107–34.

D. Eustache, Corpus de dirhams idrīsides et contemporains. Collection de la Banque du Maroc et autres collections mondiales, publiques etprivées, Rabat 1970–1, with a list of rulers and genealogical tables at pp. 3ff. and with notes at pp. 17–24.

161–296/778–909

Tahert (Tāhart), in western Algeria

| 161/778 | ‘Abd al-Raḥmān b. Rustam |

| 171/788 | ‘Abd al-Wahhāb b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān |

| 208/824 | Aflaḥ b. ‘Abd al-Wahhāb, Abū Sa‘īd |

| 258/872 | Abū Bakr b. Aflah |

| 260/874 | Muḥammad b. Aflah, Abu ’l-Yaqẓān |

| 281/894 | Yūsuf b. Muḥammad, Abū Ḥātim, first reign |

| 282/895 | Ya‘qūb b. Aflaḥ, first reign |

| 286/899 | Yūsuf b. Muḥammad, second reign |

| ? | Ya‘qūb b. Aflaḥ, second reign |

| 294–6/907–9 | Yaqẓān b. Muḥammad |

| 296/909 | Destruction of Tahert by the Fāṭimids |

The Rustamids have an importance for the history of Islam in North Africa disproportionate to the duration and limited extent of their political power. In the eighth century, the majority of the Berbers of North Africa adopted the radical, egalitarian religio-political sect of Khārijism, perhaps as an expression of their own ethnic solidarity against domination by their orthodox Sunnī Arab masters. Whereas in the east, except for certain areas of concentration, Khārijism tended to be an extremist, savagely violent minority faith, in North Africa, though equally violent, it was more of a mass movement. The Khārijī sub-sect of the Ibāḍiyya, the followers of one ‘Abdallāh b. Ibāḍ of Baṣra, had their original North African centre among the Zanāta Berbers of the Jabal Nafūsa in modern Tripolitania; and, after a temporary capture of Kairouan (Qayrawān) in central Ifrīqiya or Tunisia, the bastion of Arab religious orthodoxy and military power, these Ibāḍīs controlled a vast region from Barca to the fringes of Morocco. When Arab dominion was largely re-established, a group of the Ibāḍīs under the leadership of ‘Abd al-Raḥmān b. Rustam (whose name would indicate Persian descent; he was later provided with a doubtless fictitious genealogy back to Sāsānid royalty) fled to what is now western Algeria.

Here, ‘Abd al-Raḥmān in 144/761 founded a Khārijī principality based on the newly-founded town of Tahert (Tāhart) (near modern Tiaret), and some fifteen years later he was offered the imamate of all the Ibāḍiyya of North Africa. This nucleus in Tahert was linked with Ibāḍī communities in the Aurès, southern Tunisia and the Jabal Nafūsa, and groups as far south as the Fezzān oasis acknowledged the spiritual headship of the Ibāḍī Imāms. Surrounded as they were by enemies, including the Shī‘ī Idrīsids (see above, no. 8) to the west and the Sunnī ‘Abbāsid governors and then the Aghlabids to the east, the Rustamids sought the alliance of the Spanish Umayyads, and received subsidies from them. But the rise of the messianic Shī‘ī Fāṭimids in Morocco was fatal for them, as for other local dynasties of the Maghrib like the Ṣufrī Khārijī Midrārids (see below, no. 10) and the Aghlabids. The later Rustamids were cut off in the course of the ninth century through schisms within Khārijism from their co-religionists in Tripolitania, and in 296/909 Tahert fell to the Kutāma Berber followers of the Fāṭimid dā‘ī or propagandist Abū ‘Abdallāh; many of the Rustamids were massacred, and the rest fled southwards to the oasis of Ouargla (Wargla).

Tahert under the Rustamids enjoyed a great material prosperity, being one of the northern termini, like Sijilmāsa, of the trans-Saharan caravan routes, and it acquired the name of ‘the Iraq of the Maghrib’. It attracted a cosmopolitan population, among whom were appreciable Persian and Christian elements, and was a centre of scholarship. Its great historical role was as a rallying-point and nerve-centre for Khārijism throughout North Africa; although Tahert succumbed to the Fāṭimids, Ibāḍī doctrines long remained potent in the Maghrib, and have indeed survived to this day in a few places like the Mzāb oasis in Algeria, the Tunisian island of Djerba (Jarba) and in the Jabal Nafūsa.

It is somewhat remarkable that no coins of the Rustamids have yet been found.

Sachau, 24–5 no. 55; Zambaur, 64.

EI1 ‘Tāhert’ (G. Marçāis), EI2 ‘Ibāḍiyya’ (T. Lewicki), ‘Rustamids’ (M. Talbi).

Chikh Békri, ‘Le Kharijisme berbère: quelques aspects du royaume rustumide’, AIEO Alger, 15(1957), 55–108.

208–366/823–977

Sijilmāsa in south-eastern Morocco

| 208/823 | al-Muntaṣir b. Ilyasa‘, Abū Mālik, called Midrār |

| 253/867 | Maymūn b. al-Muntaṣir, Ibn Thaqiyya, al-Amīr |

| 263/877 | Muḥammad b. Maymūn |

| 270/884 | Ilyasa‘ b. al-Muntaṣir, Abu ’1-Manṣūr |

| 296/909 | Wāsūl al-Fatḥ b. Maymūn al-Amīr |

| 300/913 | Aḥmad b. Maymūn al-Amīr |

| 309/921 | Muḥammad b. (?) Sārū, Abu ’l-Muntaṣir al-Mu‘tazz |

| 321/933 | Samgū b. Abi ’l-Muntaṣir, al-Muntaṣir, first reign |

| ⊘ 331/943 | Muḥammad b. Wāsūl al-Fatḥ, al-Shākir |

| 347/958 | Samgū al-Muntaṣir, second reign |

| 352 to 366 | |

| or 369/963 | |

| to 977 or 980 | (?) ‘Abdallāh b. Muḥammad, Abū Muḥammad |

| c. 366/c. 977 | Deposition of the Midrārids |

The Banū Midrār were a Berber family from the Miknāsa tribe who arose in the town of Sijilmāsa on the Sahara fringes of Morocco, either at roughly the same time as the town was founded (or refounded) or shortly afterwards, in the second half of the eighth century. The town, which seems originally to have been a settlement of Ṣufrī Khārijīs, now flourished as the northern terminus of trans-Saharan caravan trade coming from West Africa; the Midrārids came to levy transit dues and taxes on the products of the mines of southern Morocco and Mauritania (we know virtually nothing, however, of any corresponding cultural activity in the town under their rule). The chiefs of the Midrārid family had become prominent there, but it is difficult to pin down the date of the actual dynasty’s beginning. A convenient date, however, is 208/823, when Abū Mālik al-Muntaṣir, called Midrār (‘copiously flowing’ [with milk, largesse, etc.]), achieved power.

At first, the Midrārids were nominal vassals of the ‘Abbāsid caliphs, but had some connections with the Rustamids of Tahert (see above, no. 9), who were also Khārijī in faith. But in the early tenth century, following a prediction according to which the expected Mahdī or Divinely-Guided One of the Shī‘a was to appear at Sijilmāsa, the partisans of the future founder of the Fāṭimid dynasty (see below, no. 27), ‘Ubaydallāh al-Mahdī, took over Sijilmāsa in 296/909. The Midrārids were henceforth generally vassals of the Fāṭimids. But Muḥammad b. Wāsūl’s repudiation of Ṣufrī Khārijism and adoption of Mālikī Sunnism involved adherence to the cause of the Spanish Umayyads, and this change of loyalties, plus his assumption, like the Umayyads, of the exalted title of caliph, provoked a Fāṭimid reconquest of Sijilmāsa. The Midrārids returned to control the town briefly, but their dominion was ended around 366/977 or shortly thereafter, when Khazrūn, the chief of the Berber Maghrāwa tribe, which was allied with the Spanish Umayyads, killed the last Midrārid and put an end to the dynasty (the descendants of Khazrūn were in the early eleventh century to establish a Taifa principality at Arcos in Spain: see above, no. 5, Taifa no. 5).

Sachau, 25 no. 56; Zambaur, 64–5, 66; Album, 16.

EIl ‘Sidjilmāsa’ (G. S. Colin); EI2 ‘Midrār, Banū’ (Ch. Pellat).

184–296/800–909

Ifrīqiya, Algeria, Sicily

| ⊘ 184/800 | Ibrāhīm I b. al-Aghlab |

| ⊘ 197/812 | ‘Abdallāh I b. Ibrāhīm I, Abu ’l-‘Abbās |

| ⊘ 201/817 | Ziyādat Allāh I b. Ibrāhīm I, Abū Muḥammad |

| ⊘ 223/838 | al-Aghlab b. Ibrāhīm I, Abū ‘Iqāl |

| ⊘ 226/841 | Muḥammad I b. al-Aghlab, Abu ’l-‘Abbās |

| ⊘ 242/856 | Aḥmad b. Muḥammad I, Abū Ibrāhīm |

| ⊘ 249/863 | Ziyādat Allāh II b. Muḥammad I |

| ⊘ 250/863 | Muḥammad II b. Aḥmad, Abū ‘Abdallāh Abu ’1-Gharānīq |

| ⊘ 261/875 | Ibrāhīm II b. Aḥmad, Abū Ishāq |

| ⊘ 289/902 | ‘Abdallāh II b. Ibrāhīm II, Abu ’l-‘Abbās |

| ⊘ 290–6/903–9 | Ziyādat Allāh III b. ‘Abdallāh II, Abū Mudar, died in exile |

| 290/909 | Fāṭimid conquest |

Ibrāhīm b. al-Aghlab’s father was a Khurāsānian Arab commander in the ‘Abbāsid army, and in 184/800 the son was granted the province of Ifrīqiya by Hārūn al-Rashīd in return for an annual tribute of 40,000 dīnārs. The grant involved considerable rights of autonomy, and the great distance of North Africa from Baghdad ensured that none of the Aghlabids was much disturbed by the caliphal government, itself increasingly racked by succession disputes and internal strife after the mid-ninth century. Nevertheless, the Aghlabids always remained theoretical vassals of the caliphs, retaining the caliphs’ names in the khutba or Friday sermon though never on Aghlabid coins after the time of Ibrāhīm I. The first Aghlabids suppressed outbreaks of Berber Khārijism in their territories; and then, under Ziyādat Allāh I, one of the most capable and energetic members of the family, the great project of the conquest of Sicily from the Byzantines was begun in 217/827. An extensive corsair fleet was launched, making the Aghlabids masters of the central Mediterranean and enabling them to harry the coasts of southern Italy, Sardinia, Corsica and even that of the Maritime Alps. Malta was captured before 256/870 and occupied by the Muslims for over two centuries until the Norman reconquest. It is probable that the conquest of Sicily was begun in order to divert religious bellicosity into jihād against the infidels, for the early Aghlabid amīrs had to cope with strong internal opposition in Ifrīqiya from the Mālikī fuqahā’ or religious lawyers in Kairouan. By the opening of the tenth century the conquest of Sicily was virtually complete, and the island remained under Muslim rule, at first under governors appointed by the Aghlabids and then under those of the Fāṭimids, including the Kalbids (see below, no. 12), until the Norman reconquest of the later eleventh century, forming an important centre for the diffusion of Islamic culture to Christian Europe.

However, the Aghlabids’ hold on Ifrīqiya became loosened towards the end of the ninth century. The Shī‘ī propaganda of the dā‘ī Abū ‘Abdallāh had a powerful effect among the Kutāma Berbers of the mountainous region of what is now north-eastern Algeria. Kutāma forces inflicted several defeats on the Aghlabid army, and the last of the line, Ziyādat Allāh III, was compelled in 296/909 to abandon the capital al-Raqqāda, founded by his grandfather Ibrāhīm II, and fled to Egypt after fruitless attempts to secure help from the ‘Abbāsids, subsequently dying in the East. Ifrīqiya now became the nucleus of the Fāṭimids’ North African possessions, where they constructed their capital al-Mahdiyya, which then replaced al-Raqqāda.

Lane-Poole, 36–8; Zambaur, 67–8; Album, 15–16.

EI2 ‘Aghlabids’ (G. Marçais).

M. Vonderheyden, La Berbérie orientale sous la dynastie des Benoû Aṛlab 800–909, Paris 1927, with genealogical table at p. 332.

O. Grabar, The Coinage of the Ṭūlūnids,ANS Numismatic Notes and Monographs, no. 139, New York 1957, 51–4.

M. Talbi, L’émirat aghlabide, Paris 1966.

337–445/948–1053

Governors in Sicily

| 337/948 | al-Hasan b. ‘Abdallāh b. Abi ’l-Ḥusayn al-Kalbī |

| 342/953 | Aḥmad b. al-Ḥasan, Abu ’l-Ḥusayn |

| 359/970 | ‘Alī b. al-Ḥasan, Abu ’1-Qāsim |

| 372/982 | Jāhir b. ‘Alī |

| 373/983 | Ja‘far b. Muḥammad b. ‘Alī |

375/985 ‘Abdallāh b. Muḥammad b. ‘Alī |

|

| 379/989 | Yūsuf b. ‘Abdallāh, Abu ’l-Futūḥ Thiqat al-Dawla |

| 388/998 | Ja‘far b. Yūsuf, Tāj al-Dawla |

| 410/1019 | Aḥmad al-Akḥal b. Yūsuf, Abū Ja‘far Ta’yīd al-Dawla, d. 429/1038 |

| 431–c. 445/1040–c. 1053 | al-Ḥasan al-Ṣamṣām b. Yūsuf, Ṣamṣām al-Dawla |

| 436–/1044– | Disintegration of Arab Sicily into various principalities, with the Norman conquest beginning from 452/1060 onwards |

The Byzantine province of Sicily was conquered by Arab forces sent by the Aghlabids of Ifrīqiya (see above, no. 11) over a period of more than seventy years from 212/827 onwards, culminating in the capture of Taormina in 289/902. The Aghlabids appointed their own governors to the island, as did their successors in North Africa after 296/909, the Fāṭimids (see below, no. 27). The lengthy period of rule by the Kalbid governors began with the caliph al-Mansūr’s nomination of al-Ḥasan b. ‘Alī al-Kalbī, although their succession was not recognised as implicitly hereditary until al-Mu‘izz’s caliphate in 359/970. The Fāṭimids’ transfer of their centre of power to Egypt meant, in practice, more freedom of action for the Kalbids, who nevertheless remained firmly loyal to their masters, receiving from them honorific titles and, latterly, resisting pressure from the Zīrids (see below, no. 13) in North Africa. In the early decades of their rule, the Kalbids combated the Byzantines and led frequent raids on Calabria and other parts of the Italian mainland, reaching as far as Naples. After c. 421/c. 1040, however, the power of the Kalbids was in decline, with attacks from the Byzantines and from Italian city-states like Pisa. All these led to a period of disintegration of Arab rule in Sicily into a series of tawā’ if resembling those in Spain (see above, no. 5), paving the way for the first appearance of the Normans in 1060 and the subsequent reincorporation of Sicily into Christendom.

It does not seem that the Kalbid governors ever minted coins in Sicily on behalf of their suzerains, but a puzzling point is the large number of glass weights of their period which have been found in Sicily, these being far more numerous than would have been needed for weighing out small quantities of precious metals. It has accordingly been suggested that these glass weights may have served as a purely local currency for minor transactions.

Sachau, 26 no. 64; Zambaur, 67–9.

EI2 ‘Kalbids’ (U. Rizzitano); ‘Sikilliya’ (R. Traini, G. Oman and V. Grassi).

M. Amari, Storia del Musulmani di Sicilia, 2nd edn, C. A. Nallino, Catania 1933–9, II, 241–490.

Aziz Ahmad, A History of Muslim Sicily, Edinburgh 1975, 30–40.

361–547/972–1152

Tunisia and eastern Algeria

1. Zīrid governors of the Maghrib for the Fāṭimids

| after 336/947 | Zīrī b. Manād |

| 361/972 | Yūsuf Buluggīn I b. Zīrī |

| 373/984 | al-Manṣūr b. Buluggīn I |

| 386/996 | Bādīs b. al-Manṣūr, Nāṣir al-Dawla |

Division of authority |

|

2. Zīrids of Kairouan |

|

| 405/1015 | Bādīs |

| ⊘ 406/1016 | al-Mu‘izz b. Bādīs |

| 454/1062 | Tamīm b. al-Mu‘izz |

| 501/1108 | Yaḥyā b.Tamīm |

| 509/1116 | ‘Alī b. Yaḥyā |

| 515–43/1121–48 | al-Ḥasan b. ‘Alī |

Norman and then Almohad conquest, with al-Ḥasan as Almohad governor until 558/1163, d. 563/1168 |

3. Ḥammādids of Qal‘at Banī Ḥammād

| 405/1015 | Ḥammād b. Buluggīn I |

| 419/1028 | al-Qā’id b. Ḥammād, Sharaf al-Dawla |

| 446/1054 | Muḥsin b. al-Qā’id |

| 447/1055 | Buluggīn II b. Muḥammad |

| 454/1062 | al-Nāṣir b. ‘Alannās |

| 481/1088 | al-Manṣūr b. al-Nāṣir |

| 498/1105 | Bādīs b. al-Manṣūr |

| 498/1105 | al-‘Azīz b. al-Manṣūr |

| ⊘ 515 or 518–47/1121 or 1124–52 | Yaḥyā b. al-‘Azīz, d. 557/1162 |

| 547/1152 | Almohad conquest |

The Zīrids were Ṣanhāja Berbers inhabiting the central part of the Maghrib, who early identified themselves with the Fāṭimid cause in North Africa, bringing military relief to the Fāṭimid capital of al-Mahdiyya when in 334/945 it was besieged by the Khārijī rebel Abū Yazīd al-Nukkarī ‘the Man on the Donkey’. Accordingly, when the Fāṭimid caliph al-Mu‘izz left for Egypt, he appointed Buluggīn I b. Zīrī, whose family had already served the dynasty as governors, to be viceroy of Ifrīqiya. Buluggīn kept up the traditional enmity of his people with the nomadic Zanāta Berbers, and overran all the Maghrib as far west as Ceuta. A branch of the family under another son of Zīrī, Zāwī, took service in Spain under the Ḥājib al-Muẓaffar b. al-Manṣūr Ibn Abī ‘Amir, and after 403/1013 was able to found a Taifa in Granada (see above, no. 5, Taifa no. 6).

Buluggīn’s grandson Bādīs entrusted the more westerly part of his governorship to his uncle Ḥammād b. Buluggīn I, and the latter built a capital for himself and his family at Qal‘at Banī Ḥammād, in the upland plain of the Hodna near Msila in the central Maghrib. After discord broke out in 405/1015 between Ḥammād and Bādīs, in which the former temporarily transferred his allegiance to the ‘Abbāsids, there was a divisio imperii: the Zīrid main branch of North Africa remained in Ifrīqiya, with its capital at Kairouan, while Ḥammād’s line took over the lands further west.

The rich resources and wealth of Ifrīqiya tempted the Zīrid al-Mu‘izz b. Bādīs to rebel against his Fāṭimid overlords, and in 433/1041 he gave his allegiance to the ‘Abbāsids (the Ḥammādid al-Qā’id, after temporarily recognising the Baghdad caliphs, returned to Fāṭimid allegiance). Hence shortly afterwards, the Fāṭimids in Egypt released against the Zīrids bands of unassimilated, barbarian Bedouins of the Hilāl and Sulaym tribes, who migrated from Lower Egypt to the Maghrib. These Arabs gradually worked their way across the countryside, terrorising the towns and forcing the Zīrids to evacuate Kairouan for al-Mahdiyya on the coast and the Ḥammādids to withdraw to the less accessible port of Bougie (Bijāya), renamed al-Nāṣiriyya after its founder al-Nāṣir b. ‘Alannās. Having lost control of the land, the two sister lines turned to the sea and built up a fleet; it is, indeed, this period which inaugurates the age of the Barbary corsairs. But they were unable to prevent Muslim Sicily from falling to the Normans, even though peaceful commercial relations were later established with the Norman kings. By the twelfth century, the Zīrids were hard pressed; Roger II of Sicily captured al-Mahdiyya and the Tunisian coast, forcing the Zīrid al-Ḥasan b. ‘Alī to pay tribute. Also, within the Maghrib, the Almohads (see below, no. 15) were now advancing relentlessly eastwards. The Ḥammādids were overrun, and the last ruler, Yaḥyā, surrendered at Constantine and ended his days in exile in Morocco. The last Zīrid, al-Ḥasan, was at one point reinstated as Almohad governor of al-Mahdiyya, functioning there until the Almohad sultan ‘Abd al-Mu’min’s death in 558/1163, but died also in Morocco eight years later.

Lane-Poole, 39–40; Zambaur, 70–1; Album, 16.

EIl ‘Zīrids’ (G. Marçais); EI2 ‘Ḥammādids’ (H. R. Idris).

H. W. Hazard, The Numismatic History of Late Medieval North Africa, ANS Numismatic Studies, no. 8, New York 1952, 53–7, 89–96, 233.

H. R. Idris, La Berbérie orientale sous les Zīrīdes Xe–XIIe siècles, 2 vols, Paris 1962, with detailed genealogical and chronological tables at II, 830ff., making many corrections to Zambaur.

Amin T. Tibi, The Tibyān. Memoirs of ‘Abd Allāh b. Buluggīn, last Zīrid Amīr of Granada, Leiden 1986, with table of the Zīrids of Muslim Spain, showing connections with the North African lines, at p. 30.

14

THE ALMORAVIDS OR AL-MURĀBIṬŪN

454–541/1062–1147

North-west Africa and Spain

| ⊘ 453/1061 | Yūsuf b. Tāshufīn |

| ⊘ (462–7/1070–5 | Ibrāhīm b. Abī Bakr, ruler in Sijilmāsa) |

| ⊘ 500/1107 | ‘Alī b. Yūsuf |

| ⊘ 537/1142 | Tāshufīn b. ‘Alī |

| ⊘ 540/1146 | Ibrāhīm b. Tāshufīn |

| ⊘ 540–1/1146–7 | Ishāq b. ‘Alī |

| 541/1147 | Almohad conquest |

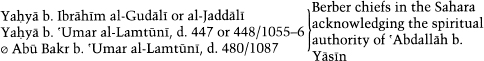

The Almoravids arose from one of the waves of spiritual exaltation which have from time to time in the history of the Maghrib come over the Berber peoples there. In the early part of the eleventh century, the Ṣanhāja chief Yaḥyā b. Ibrāhīm of the Gudāla tribe, whose territories extended over parts of what became in modern times the Spanish Sahara and Mauritania, made the Pilgrimage to Mecca. Fired with enthusiasm, he came back to his own people with a Moroccan scholar, ‘Abdallāh b. Yāsīn, with the intention of propagating a strict form of Mālikī Sunnism. The militant and expansionist ideology which ‘Abdallāh b. Yāsīn now brought into being was, according to later local historians, given impetus by the community of murābiṭūn, dwellers in a ribāṭ or hermitage situated near the mouth of the Senegal River or along the Mauritanian coast; but if this dār al-murābiṭīn did in fact exist, its importance may well have been exaggerated. At all events, the term for these warriors, murābiṭūn ‘those dwelling in a hermitage or frontier fortress’, was to yield the Spanish form Almorávides by which the subsequent dynasty was to be called, and also the French word marabout ‘holy man, saint’, a figure especially characteristic of North African Muslim piety. These Berber warriors of the Sahara wore veils over their faces against the sand and wind (as do their modern descendants the Tuaregs), hence were also known as al-mutalaththimūn ‘the veiled ones’.

Led by the Lamtunā chiefs Yaḥyā and Abū Bakr and then by the latter’s lieutenant Yūsuf b. Tāshufīn, the Almoravids moved northwards against Morocco and conquered North Africa as far as the central part of what is now Algeria. With Abū Bakr now deflected southwards into the western Sahara, Yūsuf founded Marrakech (Marrākush) as his capital in 454/1062; from this event may be dated the formal beginning of the Almoravid dynasty in Morocco, explicitly designated on some coins, after Yūsuf’s death, as the Banū Tāshufīn. The Almoravids recognised the ‘Abbāsid caliphs as spiritual heads of Islam and followed the conservative Mālikī law school, dominant in Spain and North Africa after the virtual demise of Khārijism.

Muslim Spain was at this time in the fragmented condition of the age of the Mulūk al-Tawā’if (see above, no. 5), and, now that the Christian Reconquista was gathering momentum, it became clear that only the rising power and enthusiasm of the Almoravids could save the divided and squabbling princelings there. Yūsuf b. Tāshufīn crossed over from Africa in 479/1086 and won a great victory over Alfonso VI of Léon and Castile at Zallāqa near Badajoz. Much Muslim territory was recovered or made secure in the western marches, although the recently-lost city of Toledo remained in Christian hands. Over the next few years, Yūsuf suppressed almost all the Taifas, only the Hūdids being allowed to remain in Saragossa (see above, no. 5, Taifa no. 17), and a fierce form of puritanical Islam, in which the works of the great theologian of eastern Islam, al-Ghazālī, were publicly burned, was introduced into Spain.

But in the early years of the twelfth century, the Almoravid position in the Maghrib was threatened by the rise there of a fresh religio-political movement, that of the Almohads and their Masmūda supporters in southern Morocco (see below, no. 15). It was because of this pressure in their rear that the Almoravids were unable to save Saragossa from the Christians in 512/1118. In 541/1147, the last Almoravid ruler in Marrakech, Isḥāq b. ‘Alī, was killed by ‘Abd al-Mu’min’s troops, and the Almohads now began crossing into Spain. When the last Almoravid governor there, Yaḥyā b. Ghāniya al-Massūfī, whose family was related by marriage to the Almoravid ruling house, died in 543/1148, Almoravid power was ended. However, the post-Almoravid line of this Berber family, the Banū Ghāniya, continued, and held power in the Balearic Islands until the beginning of the thirteenth century (see above, no. 6).

The Almoravids of Morocco, and the Maghrib in general, rapidly assimilated Andalusian culture at this time. Abu Bakr b. ‘Umar and Yūsuf b. Tāshufīn came to disclaim their Berber origins and instead pretended to a Qaḥṭānī, South Arabian, royal pedigree. The dominance of Mālikism in North Africa was given a great fillip by their patronage, and the study of Mālikn legal manuals was exalted above that of the Qur’ān and Hadīth, while kalām, scholastic theology, was regarded as positively inimical to the faith. Perhaps the most lasting legacy, however, of the Almoravid movement was the impetus which it gave to the spread of Islam, and of Almoravid religious doctrines in particular, southwards across the Sahara to the Sāḥil and Savannah zones of West Africa, namely to modern Senegal, Niger, Mali and northern Nigeria.

Lane-Poole, 41–4; Zambaur, 73–4; Album, 16.

EI2 ‘al-Murābiṭūn’ (H. T. Norris and P. Chalmeta).

H. Terrasse, Histoire du Maroc, I, 211–60.

J. Bosch Vilá, Los Almorávides, Instituto General Franco de Estudios y investigación hispano-árabe, Historia de Marruecos, Tetouan 1950.

H. W. Hazard, The Numismatic History of Late Medieval North Africa, 59–64, 95–143, 236–63, 282–3.

15

THE ALMOHADS OR AL-MUWAḤḤIDŪN

524–668/1130–1269

North Africa and Spain

Muḥammad b. Tūmart, d. 524/1130 |

|

| ⊘ 524/1130 | ‘Abd al-Mu’min b. ‘Alī al-Kūmī |

| ⊘ 558/1163 | Yūsuf I b. ‘Abd al-Mu’min, Abū Ya‘qūb |

| ⊘ 580/1184 | Ya‘qūb b. Yūsuf I, Abū Yūsuf al-Manṣūr |

| ⊘ 595/1199 | Muḥammad b. Ya‘qūb, Abū ‘Abdallāh al-Nāṣir |

| ⊘ 610/1213 | Yūsuf II b. Muḥammad, Abū Ya‘qūb al-Mustanṣir |

| 621/1224 | ‘Abd al-Wāḥid b. Yūsuf I, Abū Muḥammad al-Makhlū‘ |

| ⊘ 621/1224 | ‘Abdallāh b. Ya‘qūb, Abū Muḥammad al-‘Ādil |

| ⊘ 624–33/1227–35 | Yaḥyā b. Muḥammad, Abū Zakariyyā’ al-Mu‘taṣim. |

Authority in Morocco disputed by ⊘ Idrīs I b. Ya‘qūb, Abu ’1-‘Ulā al-Ma’mūn, 624–30/1227–32, and ⊘ ‘Abd al-Wāḥid b. Idrīs I, Abū Muḥammad al-Rashīd, 630/1232 onwards |

|

| ⊘ 633/1235 | ‘Abd al-Wāḥid b. Idrīs I, al-Rashīd |

| ⊘ 640/1242 | ‘Alī b. Idrīs I, Abu ’1-Ḥasan al-Sa‘īd |

| ⊘ 646/1248 | ‘Umar b. Isḥāq, Abū Ḥafṣ al-Murtaḍā |

| ⊘ 665–8/1266–9 | Idrīs II b. Muḥammad, Abu ’l-‘Ulā Abū Dabbūs al-Wāthiq |

Christian conquest of all mainland Spain, except Granada, by the mid-seventh/thirteenth century; the Almohad North African territories divided among the Ḥafṣids, ‘Abd al-Wādids and Marīnids |

The Almohads (an originally Spanish form from al-Muwaḥḥidūn ‘those who proclaim God’s unity’) represented, intellectually and theologically, a protest against the rigidly conservative and legalistic Mālikism prevalent in North Africa and against the social laxity of life under the later Almoravids (see above, no. 14). Their founder, the Maṣmūda Berber Ibn Tūmart, had studied in the East and had acquired ascetic, reformist views. On returning to Morocco, he was in 515/1121 hailed by his followers as the Mahdī or promised charismatic leader who would restore and cause to triumph the true and universal Islam. For his fellow-Berbers of southern Morocco, he made available in their own language Muslim creeds and other theological and legal works, so that one aspect of his mission may have been to express the religious feelings of the mountain Berbers against the essentially urban attitudes of the Mālikī lawyers who were the mainstay of Almoravid religious authority. His lieutenant ‘Abd al-Mu’min assumed leadership of the movement on Ibn Tūmart’s death; he carried on the war against the Almoravids, gradually taking over Morocco from them, and after 542/1147 he made the Almoravid capital of Marrakech his own.

In Spain, there was a vacuum of power after the decline of the Almoravids there, in which some local groups like the Taifas of the previous century reappeared, for example at Valencia, Cordova, Murcia and Mértola (see above, no. 5, Taifas nos 11, 15, 18). Then, in 540/1145, ‘Abd al-Mu’min despatched an army to Spain and soon occupied the greater part of the Muslim-held territory there. A powerful Almohad kingdom, with its capital at Seville, was now constituted on both sides of the Straits of Gibraltar. The countryside of the central and eastern Maghrib had become economically disrupted, and socially and politically disturbed, by influxes of nomadic Arabs from the East, and the coastlands were being harried by Norman Christian raiders. With his highly effective military and naval forces, ‘Abd al-Mu’min conquered as far as Tunis and Tripoli, thus uniting the whole of North Africa under Almohad rule; the Ayyūbid sultan Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn or Saladin (see below, no. 30) sought – in vain, as it proved – Almohad ships for his war against the Frankish Crusaders. The Almohad rulers now assumed the lofty titles of caliph and ‘Commander of the Faithful’.

The structure of the Almohad state reflected the messianic, authoritarian nature of Ibn Tūmart’s original teaching, and was built around a closely-knit hierarchy of the caliphs’ advisers and intimates. Their court was a splendid centre of art and learning, above all, for the last flowering of Islamic philosophy associated with such scholars as Ibn Ṭufayl (Abubacer) and Ibn Rushd (Averroes), both of whom acted as court physicians to the Almohad rulers; and the Almohad period saw a remarkable florescence of a simple but monumental style of architecture in North Africa and at Seville. Intellectual speculation was nevertheless confined to the narrow court circles, and elsewhere in the Almohad empire a rigid and repressive orthodoxy prevailed. The Dhimmīs or ‘Protected Peoples’, Jews and Christians, suffered extreme hostility and persecution, seen in the massacres of Jews in Spain and Morocco, which triggered an exodus of Jews to Christian Europe and to the Near East; those to the latter destination included the physician and philosopher Maimonides, who fled from Cordova and settled in Cairo.

Abū Yūsuf Ya‘qūb won a victory over the Christians of Spain at Alarcos (al-Arak) in 591/1195, and his successor freed the eastern Maghrib as far as Libya and the Balearic Islands from the control of the Banū Ghāniya (see above, no. 6). But Muḥammad al-Nāṣir’s catastrophic defeat in 609/1212 at Las Navas de Tolosa (al-‘Iqāb), at the hands of most of the Christian kings of the peninsula, led to a decline of Almohad authority in Spain and Morocco, with internal revolts and dynastic quarrels, and with Idrīs al-Ma’mūn repudiating the Almohad doctrine. Spain was abandoned, to face alone the impetus of the Reconquista, and the Almohad grip on North Africa began also to loosen. In 627/1230, the Ḥafṣid governor of Ifrīqiya proclaimed his independence (see below, no. 18), and a decade later the rising of Yaghmurāsan b. Zayyān or Ziyān in the central Maghrib led to the formation of the ‘Abd al-Wādid kingdom based on Tlemcen (Tilimsān) (see below, no. 17). Within Morocco, the Marīnids (see below, no. 16) began to wear down what remained of Almohad authority, culminating in their capture of Marrākush in 668/1269 and of Tinmallal, cradle of the Almohad movement, eight years later; the capital of Morocco now moved to Fez.

Lane-Poole, 45–7; Zambaur, 73–4; Album, 16–17.

EI2 ‘al-Muwahhidūn’ (M. Shatzmiller).

H. Terrasse, Histoire du Maroc, I, 261–367.

H. W. Hazard, The Numismatic History of Late Medieval North Africa, 64–8, 143–58, 262–73, 283.

A. Huici Miranda, Historia politica del imperio Almohade, 2 vols, Instituto General Franco de Estudios y investigación hispano-árabe, Tetouan 1956–7.

614–869/1217–1465

North Africa

‘Abd al-Ḥaqq I al-Marīnī, Abū Muḥammad |

|

| 614/1217 | ‘Uthmān I b. ‘Abd al-Ḥaqq I, Abū Sa‘īd |

| 638/1240 | Muḥammad I b. ‘Abd al-Ḥaqq I, Abū Ma‘rūf |

| ⊘ 642/1244 | Abū Bakr b. ‘Abd al-Ḥaqq I, Abū Yaḥyā |

| ⊘ 656/1258 | Ya‘qūb b. ‘Abd al-Ḥaqq I, Abū Yūsuf |

| ⊘ 685/1286 | Yūsuf b. Ya‘qūb, Abū Ya‘qūb al-Nāṣir |

| 706/1307 | ‘Amr b. Yūsuf, Abū Thābit |

| 708/1308 | Sulaymān b. Yūsuf, Abu ’l-Rabī‘ |

| ⊘ 710/1310 | ‘Uthmān II b. Ya‘qūb, Abū Sa‘īd |

| ⊘ 731/1331 | ‘Alī b. ‘Uthmān II, Abu ’l-Ḥasan |

| ⊘ 749/1348 | Fāris b. ‘Alī, Abū ‘Inān al-Mutawakkil |

| 759/1358 | Muḥammad II b. Fāris, Abū Zayyān or Ziyān al-Sa‘īd, first reign |

| 759/1358 | Abū Bakr b. Fāris, Abū Yaḥyā |

| ⊘ 760/1359 | Ibrāhīm b. ‘Alī, Abū Sālim |

| 762/1361 | Tāshufīn b. ‘Alī, Abū ‘Amr |

| ⊘ 763/1362 | Muḥammad II b. Fāris, al-Muntaṣir, second reign |

| (763/1362 | ‘Abd al-Ḥalīm b. ‘Umar, Abū Muḥammad, in Sijilmāsa only) |

| ⊘ (764–5/1363–4 | ‘Abd al-Mu’min b. ‘Umar, Abū Mālik in Sijilmāsa only) |

| ⊘ 767/1366 | ‘Abd al-‘Azīz I b. ‘Alī, Abū Fāris al-Mustanṣir |

| ⊘ 774/1372 | Muḥammad III b. ‘Abd al-‘Azīz, Abū Zayyān or Ziyān al-Sa‘īd |

| ⊘ 775/1373 | Aḥmad I b. Ibrāhīm, Abu ’l-‘Abbās al-Mustanṣir |

| ⊘ (776–84/1374–82 | ‘Abd al-Raḥmān b. Abī Ifallūsin, Abū Zayd, ruler in Marrakech) |

| ⊘ 786/1384 | Mūsā b. Fāris, Abū Fāris |

| ⊘ 788/1386 | Muḥammad IV b. Aḥmad I, Abū Zayyān or Ziyān al-Muntaṣir |

| 788/1386 | Muḥammad V b. ‘Alī, Abū Zayyān or Ziyān al-Wāthiq |

| 789/1387 | Aḥmad II b. Aḥmad I, Abu ’l-‘Abbās |

| ⊘ 796/1393 | ‘Abd al-‘Azīz II b. Aḥmad II, Abū Fāris |

| ⊘ 799/1397 | ‘Abdallāh b. Aḥmad II, Abū ‘Amir |

| ⊘ 800/1398 | ‘Uthmān III b. Aḥmad II, Abū Sa‘īd |

| 823–69/1420–65 | ‘Abd al-Ḥaqq II b. ‘Uthmān III, Abū Muḥammad, under the regency of the Waṭṭāsids and then as nominal ruler under their control |

The Marīnids succeeded to the heritage of the Almohads (see above, no. 15) in Morocco and much of the lands of the Maghrib lying to the east. The Banū Marīn were a tribe of Zanāta Berbers who nomadised on the north-western fringes of the Sahara, where there now runs in a north-east to south-west direction the modern border between Algeria and Morocco. It seems that they were sheep herders and that they gave their name to the fine-quality merino wool exported from an early date via mediaeval Italy to Europe. The cultural level of the Banū Marīn was probably low; they were uninspired in their bid for power by any of the religious enthusiasms which had given impetus to the movements of the Almoravids and Almohads, and may not have been long converted to Islam. These facts, combined with what seem to have been comparatively restricted numbers, doubtless account for the protracted nature of their struggles in the mid-thirteenth century with the later Almohads. They first invaded Morocco from the Sahara in 613/1216, but were halted by the Almohad rulers, and did not capture the latter’s capital Marrakech until 668/1269 and Sijilmāsa until four years later.

Once established in their capital at Fez, the Marīnids acquired a strong sense of being heirs to the Almohads, and attempted, with considerable success, to rebuild their empire in the Maghrib. They further nurtured the spirit of jihād and utilised popular religious fervour in the Maghrib for a desired reconquest of Spain. Several Marīnid sultans fought personally in the Iberian peninsula. Abū Yūsuf Ya‘qūb crossed over in answer to an appeal from the Naṣrids of Granada (see above, no. 7) and won the battle of Ecija in 674/1275. After the Christian capture of Gibraltar in 709/1309, Marīnid troops again appeared in Spain, but Abu ’1-Ḥasan ‘Alī was routed at the Rio Salado in 741/1340 by the forces of Alfonso XI of Castile and his brother-in-law Alfonso IV of Portugal, and the Marīnids never again tried to intervene directly in Spain. Within North Africa, the Marīnids wore down their neighbours the ‘Abd al-Wādids (see below, no. 17), occupying their capital Tlemcen in 737/1337 and 753/1352 and temporarily dislodging the Ḥafṣids from Tunis in 748/1347, for a while controlling the whole Maghrib. These years of the later thirteenth and the first two-thirds of the fourteenth century also saw a remarkable cultural and artistic efflorescence in Morocco, seen in the extensive building of mosques, madrasas and other public buildings which gave concrete expression to the strength of a restored Mālikism and an increased trend towards popular Sūfism and maraboutism.

Towards the end of the fourteenth century, the decline of the Marīnids began to be apparent. In 803/1401, Henry III of Castile attacked Tetouan (Tiṭṭāwīn) and in 818/1415 the Portuguese took Ceuta (Sabta), and this extension of the Reconquista to North Africa provoked a further wave of religious sentiment and calls for jihād in the Maghrib against the infidels. Within the Marīnid sultanate, there was a prolonged series of succession crises, with Marīnid princes placed on the throne for short reigns by palace coups or by Arab and Berber tribal revolts. After the assassination of sultan Abū Sa‘īd ‘Uthmān III in 823/1420, de facto power in the western Maghrib was assumed by a family related to the Marīnids, the Banū Waṭṭās (see below, no. 19), acting at first as regents for the infant Abū Muḥammad ‘Abd al-Ḥaqq II; but after the latter’s murder in 869/1465, the Waṭṭāsids shortly afterwards succeeded in form as well as name to the heritage of the Marīnids in Morocco.

Lane-Poole, 57–9; Zambaur, 79–80; Album, 18.

EI1 ‘Merīnids’ (G. Marçais); EI2 ‘Marīnids’ (Maya Shatzmiller), with detailed genealogical table, correcting and replacing that of Zambaur.

H. Terrasse, Histoire du Maroc, II, 3–104.

H. W. Hazard, The Numismatic History of Late Medieval North Africa, 79–84, 192–227, 275–8, 284–5.

17

THE ‘ ABD AL-WĀDIDS OR ZAYYĀNIDS OR ZIYĀNIDS

633–962/1236–1555

Western Algeria

| ⊘ 633/1236 | Yaghmurāsan b. Zayyān or Ziyān, Abū Yaḥyā |

| 681/1283 | ‘Uthmān I b. Yaghmurāsan, Abū Sa‘īd |

| 703/1304 | Muḥammad I b. ‘Uthmān, Abū Zayyān or Ziyān |

| ⊘ 707/1308 | Mūsā I b. ‘Uthmān, Abū Hammū |

| ⊘ 718/1318 | ‘Abd al-Raḥmān I b. Mūsa I, Abū Tāshufīn |

| 737/1337 | First Marīnid conquest |

| 749/1348 |

|

| 753/1352 | Second Marīnid conquest |

| ⊘ 760/1359 | Mūsā II b. Yūsuf, Abū Ḥammū |

| ⊘ 791/1389 | ‘Abd al-Raḥmān II b. Mūsā II, Abū Tāshufīn |

| 796/1394 | Yūsuf I b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān II, Abū Thābit |

| 796/1394 | Yūsuf II b. Mūsa II, Abu ’1-Ḥajjāj |

| ⊘ 797/1395 | Muḥammad II b. Mūsā II, Abū Zayyān or Ziyān |

| ⊘ 802/1400 | ‘Abdallāh I b. Mūsā II, Abū Muḥammad |

| ⊘ 804/1402 | Muḥammad III b. Mūsā II, Abū ‘Abd Allāh al-Wāthiq |

| 813/1411 | ‘Abd al-Raḥmān III b. Muḥammad III, Abū Tāshufīn |

| 814/1411 | Sa‘īd b. Mūsā II |

| ⊘ 814/1411 | ‘Abd al-Wāḥid b. Mūsā II, Abū Mālik, first reign |

| ⊘ 827/1424 | Muḥammad IV b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān III, Abū ‘Abdallāh |

| 831/1428 | ‘Abd al-Wāḥid b. Mūsā II, second reign |

| ⊘ 833/1430 | Aḥmad I b. Mūsā II, Abu ’l-‘Abbās |

| ⊘ 866/1462 | Muḥammad V b. Muḥammad, Abū ‘Abdallāh al-Mutawakkil |

| 873/1469 | Abū Tāshufīn b. Muḥammad V |

| 873/1469 | Muḥammad VI b. Muḥammad V, Abū ‘Abdallāh al-Thābitī |

| ⊘ 910/1504 | Muḥammad VII b. Muḥammad VI, Abū ‘Abdallāh al-Thābitī, after 918/1512 as a vassal of Ferdinand II of Aragon |

| 923/1517 | Mūsā III b. Muḥammad V, Abū Ḥammū |

| 934/1528 | ‘Abdallāh II b. Muḥammad V, Abū Muḥammad |

| ⊘ 947/1540 | Muḥammad VIII b. ‘Abdallāh II, Abū ‘Abdallāh |

| 947/1541 | Aḥmad II b. ‘Abdallāh II, Abū Zayyān or Ziyān, first reign |

| 949/1543 | Spanish occupation |

| 951/1544 | Aḥmad II b. ‘Abdallāh II, second reign, as an Ottoman vassal |

| 957/1550 | al-Ḥasan b.‘Abdallāh II |

| 962/1555 | Conquest of Tlemcen by Ṣalāḥ Re’īs Pasha of Algiers |

The ‘Abd al-Wādids or Zayyānids or Ziyānids were originally from the Wāsīn tribe of Zanāta Berbers, hence kin to the Marīnids (see above, no. 16). They rose to prominence in what is now north-western Algeria through their support to the Almohads, so that their chief, Yaghmurāsan (? Yaghamrāsan), was able to found a principality of his own based on Tlemcen (Tilimsān). The decay of his Almohad suzerains left him exposed to attack by the Marīnids of Fez, and after his death the latter were twice to occupy Tlemcen. The ‘Abd al-Wādid princes endeavoured to stem Marīnid ambitions against Tlemcen through alliances with Christian Castile and the Naṣrids of Granada (see above, no. 7), common foes of the Marīnids, although, having inherited lands which had been devastated by the incoming nomadic Arabs of the Banū Hilāl and Banū Sulaym, their economic and military resources were limited. The only direction in which the ‘Abd al-Wādids could themselves contemplate expansion was eastwards, although their raids here were generally checked by the Ḥafṣids (see below, no. 18). The ‘Abd al-Wādid principality never fully recovered from the Marīnid occupations, although the decline of the Marīnid rulers of Fez and their replacement by the less formidably aggressive Waṭṭāsids (see below, no. 19) relieved pressure from the direction of Morocco. It was the Ḥafṣids who were the main threat to Tlemcen in the fifteenth century, at one point successfully attacking the town and imposing vassal ‘Abd al-Wādid princes on the throne there; but this threat was succeeded in the sixteenth century by ones from the Spaniards in Oran and the Turkish pashas in Algiers, and it was from the pressure of these last two powers that the ‘Abd al-Wādids finally succumbed in 962/1555, the son of the last ruler, al-Ḥasan, becoming a Christian convert under the name of Carlos.

Tlemcen owed much of its mediaeval florescence and splendour to the ‘Abd al-Wādids. It lay on the main east-west route through Algeria to Morocco, with a caravan route southwards to the Sahara and with its own port at nearby Hunayn, which traded with the Christian powers of the western Mediterranean. The fine public buildings of Tlemcen attest the encouragement of learning and enlightened patronage of its princes.

Lane-Poole, 51, 54; Sachau, 25 no. 57; Zambaur, 77–8; Album, 17.

EI1 ‘Tlemcen’ (A. Bel); EI2 ‘Abd al-Wādids’ (G. Marçais).

H. W. Hazard, The Numismatic History of Late Medieval North Africa, 75–9, 181–92, 274–5, 284.

627–982/1229–1574

Tunisia and eastern Algeria

The Ḥafṣids, the most important dynasty in the history of later mediaeval Ifrīqiya, derived their name from Shaykh Abū Ḥafṣ ‘Umar al-Hintātī (d. 571/1176), a disciple of the founder of the Almohad movement, Ibn Tūmart (see above, no. 15), and one of ‘Abd al-Mu’min’s commanders. His offspring filled various important offices under the Almohads, including the governorship of Ifīqiya, and, once established as a separate dynasty, the early Ḥafṣids were to continue Almohad traditions in many ways. One of these Ḥafṣid governors, Abū Zakariyyā’ Yaḥyā I, in 627/1229 threw off the authority of the Almohad caliph, alleging that the latter had abandoned the true Mu’minid traditions, and proclaimed himself an independent amīr. He now expanded westwards into the central Maghrib, taking Constantine, Bougie and Algiers, making the ‘Abd al-Wādids of Tlemcen (see above, no. 17) his tributaries, compelling the Marīnids of Morocco to acknowledge him and receiving appeals for help from the beleaguered Muslims of southern Spain. He further began the tradition of close commercial relations in the western Mediterranean with such powers as Angevin Sicily and Aragon. The power of the Ḥafṣids was equally great under his son Abū ‘Abdallāh Muḥammad I, who repelled the attacks of Louis IX of France and Charles of Anjou (the Crusade of 668/1270), and assumed the titles of caliph and ‘Commander of the Faithful’ plus the grandiose honorific of al-Mustanṣir, obtaining these titles from the Sharīf of Mecca and claiming to be the heir of the recently-defunct Baghdad ‘Abbāsids (see above, no. 3, 1).

Towards the end of the thirteenth century, however, the unity of the Ḥafṣid amirate became loosened, with Bougie and Constantine, in particular, tending to fall under the authority of separate rulers from the Ḥafṣid family, and with southern Tunisia and the Djerid region also throwing off the control of Tunis during periods of weak rule. At times, there were several contenders for the throne in Tunis, with claimants ruling in various towns, and during the course of the fourteenth century the Ḥafṣid capital was twice occupied temporarily by the Marīnids (see above, no. 16). The dynasty rallied in the fifteenth century under such strong rulers as Abū Fāris ‘Abd al-‘Azīz al-Mutawakkil and his grandson Abū ‘Umar ‘Uthmān, but in the early sixteenth century the establishment of the Turks in Algiers and other ports and the inability of the Ḥafṣids to curb corsair depredations in the western Mediterranean invited attacks and reprisals by the Christians. A Turkish occupation of Tunis in 941/1535 drove out the Ḥafṣid ruler, who was only restored after the Emperor Charles V had planted a Spanish garrison at La Goletta later in that year. The last Ḥafṣids retained a precarious authority with Spanish help against the Turks; in 981/1573 Don John of Austria took Tunis, but in the following year the Ottoman commander Sinān Pasha recaptured it and carried off the last Ḥafṣid captive to Istanbul.

Tunis under the Ḥafṣids enjoyed a great resurgence of prosperity. Before the disruptive activity of the Barbary pirates caused a deterioration in relations, the Ḥafṣids had fruitful commercial treaties with Anjevin Sicily, with the Italian and southern French cities and with Aragon. Both the economy and the culture of the land also benefited from the influx of Spanish Muslim refugees (among whom were the forebears of the historian Ibn Khaldūn). Tunis became a great artistic and intellectual centre, and it was the Ḥafṣids who in the thirteenth century introduced the madrasa system of education already flourishing in the central and eastern lands of Islam.

Lane-Poole, 49–50, 52–3; Zambaur, 74–6; Album, 17.

EI2 ‘Ḥafṣids’ (H. R. Idris).

R. Brunschvig, La Berbérie orientale sous les Ḥafṣides des origines à la fin du XVe siècle, 2 vols, Paris 1940–7, with genealogical tables at II, 446.

H. W. Hazard, The Numismatic History of Late Medieval North Africa, 69–75, 159–81, 273–4, 284.

831–946/1428–1549

Morocco and the central Maghrib

| 831/1428 | Yaḥyā I b. Zayyān al-Waṭṭāsī, Abū Zakariyyā’, at first regent for the Marīnids and then as de facto ruler for them |

|

|

| 863–9/1459–65 | Direct rule of the Marīnid ‘Abd al-Ḥaqq II |

| 869–75/1465–71 | Rule of the Idrīsid Shorfā in Fez |

| ⊘ 876/1472 | Muḥammad I b. Yaḥyā I, Abū ‘Abdallāh al-Shaykh |

| ⊘ 910/1504 | Muḥammad II b. Muḥammad I, Abū ‘Abdallāh al-Burtuqālī |

| ⊘ 932/1526 | ‘Alī b. Muḥammad II, Abu ’1-Ḥasan or Abū Ḥassūn, as rival ruler, first reign |

| ⊘ 932/1526 | Aḥmad b. Muḥammad II, first reign |

| ⊘ 952/1545 | Muḥammad III b. Aḥmad, al-Qaṣrī, Nāṣir al-Dīn |

| 954–6/1547–9 | Aḥmad b. Muḥammad II, second reign |

| 956/1549 | Sa‘did Sharīfs |

| 961/1554 | ‘Alī b. Muḥammad II, temporary occupation of Fez, second reign |

| 961/1554 | Sa‘did Sharīfs |

The decline of the Marīnids (see above, no. 16) facilitated the rise of the Banū Waṭṭās, a collateral branch of the Berber Banū Marīn from which the family of ‘Abd al-Ḥaqq I, founder of the Marīnid fortunes, had sprung. The Banū Waṭṭās settled in north-eastern Morocco and the Rīf as virtually autonomous governors for their Marīnid kinsmen, with whose rule they were always closely linked, receiving high offices and other favours from the sultans.

When Morocco fell into anarchy in the 1420s, with extensive Christian attacks on its coasts and with the murder of the Marīnid Abū Sa‘īd ‘Uthmān III, the Waṭṭāsid Abū Zakariyyā’ Yaḥyā, governor of Salé (Salā), proclaimed a young son of the dead sultan as the new ruler (as events proved, the last of the Marīnid line), ‘Abd al-Ḥaqq II, with himself acting as regent. This regency of the Waṭṭāsids in fact lasted until well after the Marīnid reached his majority, and only latterly did ‘Abd al-Ḥaqq manage to throw off their tutelage. However, the Waṭṭāsids returned to power at Fez in 876/1472, now as independent rulers; under them, the city’s splendour to some extent continued as under the Marīnids, and it was during their time that Leo Africanus visited Fez.

Pressure from the Christian powers of the Iberian peninsula was meanwhile growing apace, and the fall of Granada in 897/1492 aroused a fresh wave of Islamic fervour in Morocco, spearheaded by the Sa‘did Shorfā from southern Morocco (see below, no. 20), who moved northwards and seized Marrakech in 929/1523 and Fez in 956/1549. The Waṭṭāsids even tried, in vain, to get help from the Emperor Charles V and from the Portuguese, but were unable to check the Sa‘did advance. A revanche with Ottoman Turkish help from Tlemcen achieved only a momentary success, with its ultimate failure sealing the fate of the dynasty permanently; some of the last Waṭṭāsids left for the Iberian peninsula and became converts to Christianity.

Lane-Poole, 58; Sachau, 26 no. 62; Zambaur, 79–80; Album, 18.

EI1 ‘Waṭṭāsids’ (E. Lévi-Provençal).

A. Cour, La dynastie marocaine des Beni Waṭṭās (1420–1534), Constantine 1920.

H. De Castries (ed.), Les sources inédites de l’histoire du Maroc de 1530 à 1845, Série 1, Dynastie saadienne 1530–1660, vol. IV, part I, Paris 1921, with detailed genealogical tables of the Waṭṭāsids at pp. 162–3.

H. Terrasse, Histoire du Maroc, II, 105–57.

H. W. Hazard, The Numismatic History of Late Medieval North Africa, 85–6, 229–30, 279–80, 285.

916–1069/1510–1659

Morocco

| 916/1510 | Muḥammad I b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān, Abū ‘Abdallāh al-Qā’im al-Mahdī, in the Sūs |

| 923/1517 | Aḥmad al-A‘raj b. Muḥammad al-Mahdī, north of the Atlas, then in Marrakech after 930/1524 until 950/1543 |

| ⊘ 923/1517 | Maḥammad al-Shaykh b. Muḥammad al-Mahdi, Abū ‘Abdallāh al-Mahdī al-Imām, in the Sūs, then in Marrakech after 950/1543, and then in Fez after 956/1549 as sole Sa‘dī ruler in Morocco |

| ⊘ 964/1557 | ‘Abdallāh b. Maḥammad al-Shaykh, Abū Muḥammad al-Ghālib |

| ⊘ 981/1574 | Muḥammad II b. ‘Abdallāh, al-Mutawakkil al-Maslūkh |

| ⊘ 983/1576 | ‘Abd al-Malik b. Maḥammad al-Shaykh, Abū Marwān |

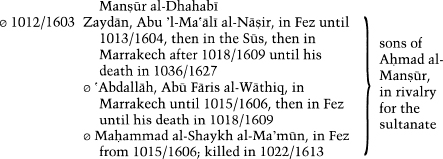

| ⊘ 986/1578 | Aḥmad b. Maḥammad al-Shaykh, Abu ’l-‘Abbās al-Manṣūr al-Dhahabī |

|

|

| ⊘ 1015/1606 | ‘Abdallāh b. Maḥammad al-Shaykh al-Ma’mūn, al-Ghālib, at first in Marrakech, then after 1018/1609 in Fez until his death in 1032/1623 |

| ⊘ 1032/1623 | ‘Abd al-Malik b. Maḥammad al-Shaykh, al-Mu‘taṣim, in Fez until 1036/1627 |

| ⊘ 1036/1627 | ‘Abd al-Malik b. Zaydān al-Nāṣir, Abū Marwān, successor to his father in Marrakech until his death in 1040/1631 |

| ⊘ (1037–8/1628–9 | Aḥmad b. Zaydān al-Nāṣir, Abu ’l-‘Abbās, claimant) |

| ⊘ 1040/1631 | Muḥammad al-Walīd b. Zaydān al-Nāṣir, in Marrakech |

| ⊘ 1045/1636 | Maḥammad al-Shaykh al-Aṣghar or al-Ṣaghīr b. Zaydān al-Nāṣir, in Marrakech |

| 1065/1655 | Aḥmad al-‘Abbās b. Maḥammad al-Shaykh al-Aṣghar |

| 1069–79/1659–68 | Power in Morocco divided between the Filālī or ‘Alawī Sharīfs of Tafilalt and the Dilā’ī marabouts of the Atlas |

From mediaeval times onwards, the Shorfā of Morocco (classical form Shurafā’, sing. Sharīf) have played an outstanding part in the country’s history. The Maghrib has often been receptive to the leadership of messianic or charismatic figures, and some of the most characteristic forms of popular Islam there have been the cult of holy men, saints and marabouts (<murābit: see above, no. 14) and the formation of religious fraternities organised round the religio-military centres of the zāwiyas. The strength of maraboutism and the rise to social preeminence of the Shorfā have been especially characteristic of Moroccan Islam, for Morocco, with its Mediterranean and Atlantic seaboards and its proximity to Spain and Portugal, bore the brunt of crusading Christian naval and military attacks from the thirteenth century onwards, provoking a Muslim reaction of commensurate intensity.

The Sharīfs are the descendants in general of the Prophet Muḥammad, but in Morocco most of the lines of Shorfā have traced their descent from the Prophet’s grandson al-Ḥasan b. ‘Alī, and the Sa‘dids and their successors the ‘Alawīs or Filālīs (see below, no. 21) claimed descent thus, specifically via al-Ḥasan’s grandson Muḥammad b. ‘Abdallāh, called al-Nafs al-Zakiyya ‘the Pure Soul’ (killed at Medina in 145/767). The Idrīsids (see above, no. 8) were the first line of Sharīfs to achieve power in Morocco, but in ensuing centuries various Berber dynasties from the Midrārids and Almoravids onwards (see above, nos 10, 14) dominated the history of the land. However, the chance of the Shorfā came in the sixteenth century when the power of the Berber Waṭṭāsids of Fez (see above, no. 19) was clearly waning. From a base in the Sūs of southern Morocco, the Sa‘did line of Shorfā – who had been quietly consolidating their position in southern Morocco for some two centuries – gradually extended northwards, seizing Marrakech in 930/1524 and Fez from the last Waṭṭāsids in 956/1549.

The full titles of the founder of the line’s fortunes, Sīdī Muḥammad al-Mahdī al-Qā’im bi-amr Allāh, show how messianic expectations in Morocco and feelings of religious exaltation and jihād against the Christians were utilised by the early Sa‘dīs. Their authority was now imposed over almost the whole of Morocco, and the Bilād al-Makhzan, or area where the sultan’s writ ran and from which taxation and troops were raised, reached its maximum extent. In the east, the Sa‘dids had a determined enemy in the Turks of Algiers, who aimed at extending Ottoman suzerainty over as much of the Maghrib as possible. Hence the Sa‘dids did not hesitate in the sixteenth century to ally with powers like Spain and Navarre against the Turks, but a long-term aim of theirs was ejection of the Portuguese from their presidios or garrison towns on the Atlantic coast. Under the greatest ruler of the dynasty, Mawlāy Aḥmad al-Manṣūr, trading relations were established with Christian powers as far afield as England, with the Barbary Company receiving commercial privileges within Morocco. But his greatest achievement was a vast expansion southwards in 999/1590 through the Sudan to the Niger valley, defeating the local ruler or Askia of Gao (in modern Mali) and extending Moroccan dominion over the Sāhil and Savannah belt of West Africa from Senegal to Bornu. The gold which now accrued to al-Manṣūr from the Sudan earned him his further honorific of al-Dhahabī ‘the Golden One’, while control of the salt-pans of the Western Sahara brought further economic benefits to Morocco. The social and fiscal privileges of the Shorfā were now further consolidated and confirmed by each new sultan on his accession, and it was the Shorfā also who, at this time, played a leading role in the formation of a Moroccan feeling, strongly xenophobic and imbued with feelings of jihād, and concerned to preserve the land against Christian and Turkish encroachments.

However, in the early seventeenth century the Sa‘dids were rent by succession disputes, with anarchy over much of Morocco and with various local adventurers and marabouts striving for power. The last Sharīfs tended to be confined to the Marrakech region, and, despite help at times from outside powers like the English and Dutch, the Sa‘dids disappeared in 1069/1659 as the authority of the ‘Alawī or Filālī Sharīfs of Tafilalt (see below, no. 21) rose pari passu with their decline and finally displaced them.

It should be noted that the honorific title Mawlāy ‘My Lord’ was frequently borne by and prefixed to the names of the Sharīfī sultans, both Sa‘dī and Filālī, with the exception of those who were called Muḥammad and were therefore called Sayyidī/Sīdī (with the same meaning), although the variant form Maḥammad (colloquial form M’ḥammed, used in the Maghrib with a hope of sharing in the baraka or charisma attached to the Prophet’s name without risk of the original form Muḥammad being profaned in any way) did not exclude the usage of Mawlāy.

Lane-Poole, 60–2; Zambaur, 81 and Table C; Album, 18.

EI1‘Shorfā’’ (E. Lévi-Provençal); El2‘Hasanī’(G. Deverdun), with a genealogical table; ‘al-Maghrib, al-Mamlaka al-Maghribiyya II. History’ (G. Yver*), ‘Sa‘dids’ (Chantal de La Véronne), with a genealogical table.

H. Terrasse, Histoire du Maroc, II, 158–235.

H. de Castries (ed.), Les sources inédites de l’histoire du Maroc de 1530 à 1845, Series I, Dynastie saadienne 1530–1660, vol. I, part 1, Paris 1905, with detailed genealogical table between pp. 382–3.

21

THE ‘ALAWID OR FILĀLĪ SHARĪFS

1041–/1631–

Morocco

| 1041/1631 | Muḥammad I al-Sharīf, in Tafilalt, died 1069/1659 |

| 1045/1635 | Maḥammad or Muḥammad II b. Muḥammad I al-Sharīf, in eastern Morocco, k. 1075/1664 |

| ⊘ 1076/1666 | al-Rashīd b. Muḥammad I al-Sharīf, in Fez, originally in Oujda (Wajda) |

| ⊘ 1082/1672 | Ismā‘īl b. Muḥammad I al-Sharīf, al-Samīn, governor in Meknès (Miknāsa), then sultan in Fez |

| 1139/1727 | Aḥmad b. Ismā‘īl, al-Dhahabī, reigned on two occasions, died, at the end of the second reign, in 1171/1757; his power contested by several of his brothers, immediately in 1139/1727 by ‘Abd al-Malik b. Ismā‘īl, and subsequently by ⊘ ‘Abdallāh (reigned on five occasions, beginning 1141/1729 and ending with his death in 1171/1757); ‘Alī Zayn al-‘Abidīn (reigned on two occasions); Muḥammad b. al-‘Arabiyya, al-Mustaḍī’; etc. |

| ⊘ 1171/1757 | Muḥammad III b. ‘Abdallāh |

| ⊘ 1204/1790 | Yazīd b. Muḥammad III |

| ⊘(1205–9/1790–4 | Ḥusayn, in Marrakech) |

| ⊘ 1206/1792 | Hishām b. Muḥammad III |

| ⊘ 1207/1793 | Sulaymān b. Muḥammad III |

| ⊘ 1238/1822 | ‘Abd al-Raḥmān b. Hishām |

| ⊘ 1276/1859 | Muḥammad IV b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān |

| ⊘ 1290/1873 | al-Ḥasan I b. Muḥammad IV, Abū ‘Alī |

| ⊘ 1311/1894 | ‘Abd al-‘Azīz b. al-Ḥasan I, abdicated 1326/1908 |

| ⊘ 1325/1907 | (‘Abd) al-Ḥafīẓ b. al-Ḥasan I |

| ⊘ 1330/1912 | Yūsuf b. al-Ḥasan I |

| ⊘ 1346/1927 | Muḥammad V b. Yūsuf, first reign |

| ⊘ 1372/1953 | Muḥammad b. ‘Arafa |

| ⊘ 1375/1955 | Muḥammad V b. Yūsuf, second reign |

| ⊘ 1380-/1961– | al-Ḥasan II b. Muḥammad V |

As the two Sa‘did makhzans based on Marrakech and Fez crumbled in the middle years of the seventeenth century (see above, no. 20), Morocco was rent by internal factions, usually with strong religious, maraboutic bases. It was the ‘Alawids or Filālī Shorfā, of the same Hasanī descent as the declining Sa‘dids, who finally succeeded in imposing order from an original centre in Tafilalt, the valley of the Wādī Zīz in south-eastern Morocco (whence the name Filālī). Mawlāy al-Rashīd was the first of the family to assume the title of sultan. He began the work of pacification and attempted a restoration of central authority throughout Morocco, but this proved an extremely lengthy process, so deep-rooted had become provincialism and anarchy. A strong figure like Mawlāy Ismā‘īl tried in vain to solve these problems by recruiting, in addition to the gīsh (<Class. Ar. jaysh) or the sultans’ military guard of Arabs, a standing army which included among other elements black slave troops, the ‘abīd al-Bukhārī (colloquially known as the Bwākher), descendants of black slaves imported by the Sa‘dids; it was also Ismā‘īl who developed Meknès as the capital and the favoured place of residence for himself and his eighteenth-century successors. But he failed to dislodge the Christians from the ports held by them, and, after his death, Morocco was plunged into its nadir of anarchy and brigandage, with a succession of rival, ephemeral rulers.

Some degree of order and prosperity was restored towards the end of the century; the last foothold of the Portuguese on the Atlantic coast at Mazagan (al-Jadīda) was taken over in 1182/1769, but the Spanish could not be dislodged from Ceuta and Melilla. Morocco was opened up to a limited extent for trade with Europe, and the new town of Mogador or Essouaira (al-Suwayra) was founded to accommodate and isolate the infidel merchants and consuls whom the sultans were compelled reluctantly to admit. However, with an essentially mediaeval polity, hardly touched by the influences which during the course of the nineteenth century affected such Islamic lands as those of Egypt, the Ottoman empire and Persia, Morocco was ill-prepared for the two disastrous wars which she fought with France (1260/1844) and Spain (1277/1859–60). By the end of the century, the ‘Alawid dynasty was tottering, with the sultans’ power challenged by various pretenders and the country forming the locale for such international incidents as that of Agadir (1911). The French Protectorate proclaimed in 1330/1912 saved the ‘Alawid dynasty itself from disappearing and Morocco from disintegration and possible dismemberment by outside powers, although the work of pacification and restoration of the sultan’s authority took twenty years; it was 1930 before the makhzan was fully in control and before the modernisation of Morocco’s infrastructure could proceed properly. Sīdī Muḥammad V in 1934 aligned himself with the growing Moroccan nationalism of the Istiqlāl or Independence Party. After the end of the Second World War, friction between Moroccan nationalism, eager for independence, and the more cautious attitude of the French Protectorate authorities, grew. Conservative, traditionalist Moroccan forces lent support to the decision in 1953 to depose Muḥammad V, but it was soon apparent that the overwhelming mass of Moroccan opinion was behind the sultan and the desire for full independence, and he had to be restored two years later. Morocco became independent in 1956, and in 1957 Sīdī Muḥammad assumed the title of king, so that Morocco under his son and successor al-Ḥasan II is one of the few monarchies surviving today in the Arab world.

Lane-Poole, 60–2; Zambaur, 81 and Table C; Album, 18–19.

EI2 ‘Alawīs’ (H. Terrasse), ‘Hasanī’ (G. Deverdun), with a genealogical table; ‘al-Maghrib, al-Mamlaka al-Maghribiyya. II. History’ (G. Yver*), ‘Shurafā’’ (E. Lévi-Provençal and Chant al de La Véronne).

H. de Castries and Pierre de Cenival (eds), Les sources inédites de l’histoire du Maroc …, Series II, Dynastie filalienne. Archives et bibliothèques de France, Paris 1922–31.

H. Terrasse, Histoire du Maroc, II, 239–406.

1117–1376/1705–1957

Tunisia

| 1117/1705 | al-Ḥusayn I b. ‘Alī al-Turki, k. 1152/1746 |

| 1148/1735 | ‘Alī I b. Muḥammad |

| 1170/1756 | Muḥammad I b. al-Ḥusayn I |

| 1172/1759 | ‘Alī II b. al-Ḥusayn I |

| 1196/1782 | Ḥam(m)ūda Pasha b. ‘Alī II |

| 1229/1814 | ‘Uthmān b. ‘Alī II |

| 1229/1814 | Maḥgmūd b. Muḥammad I |

| 1239/1824 | al-Ḥusayn II b. Maḥmūd |

| 1251/1835 | Muṣṭafā b Maḥmūd |

| 1253/1837 | Aḥmad I b. Muṣṭafā |

| ⊘ 1271/1855 | Muḥammad II b. al-Ḥusayn II |

| ⊘ 1276/1859 | Muḥammad III al-Ṣādiq b. al-Ḥusayn II |

| ⊘ 1299/1882 | ‘Alī III b. al-Ḥusayn II |

| ⊘ 1320/1902 | Muḥammad IV al-Hādī b. ‘Alī III |

| ⊘ 1324/1906 | Muḥammad V al-Nāṣir b. Muḥammad II |

| ⊘ 1341/1922 | Muḥammad VI al-Ḥabīb b. Muḥammad V |

| ⊘ 1347/1929 | Aḥmad II b. ‘Alī III |

| ⊘ 1361/1942 | Muḥammad VII al-Munṣif (Moncef) b. Muḥammad V |

| ⊘ 1362/1943 | Muḥammad VIII al-Amīn (Lamine) b. Muḥammad VI, d. 1382/1962 |

| ⊘ 1376/1957 | Ḥusayn al-Naṣr b. Muḥammad V |

| 1376/1957 | Rashād al-Mahdī b. Ḥusayn, King of the Tunisians |

| 1376/1957 | Republican régime |

The Ḥusaynid Beys arose out of the Turkish garrison for the Ottomans in Algiers. The commander al-Ḥusayn b. ‘Alī was raised to the Beylicate after the military defeat and deposition of the previous Bey of Tunis in 1117/1705. While the suzerainty of the Ottomans was to be acknowledged, with the sultans in their turn regarding the Ḥusaynids as provincial goverors or beylerbeyis, al-Ḥusayn and his descendants were granted by the local Ottoman commanders hereditary succession by male primogeniture. In practice, this form of succession did not always happen, and latterly the succession tended to go to elderly collateral members of the family who were no longer fully competent to deal with affairs. But the Ḥusaynids were nevertheless to rule for two and a half centuries, though latterly under French protection. In an absence of Turkish interference, the Beys were able to make diplomatic agreements with European powers like France, England and the Italian states, and their power within Tunisia became somewhat firmer once Ḥam(m)ūda Pasha had suppressed the local corps of Janissaries in 1226/1811.

During the nineteenth century, there were signs that the Beys aimed at a policy more independent of their suzerains in Istanbul. The relationship, with the possibility of Ottoman diplomatic and military protection, still had advantages for Tunis, as in 1259–60/1843–4 when there was tension with Sardinia. Tunisian contingents joined the Ottoman forces during the Greek Revolt and the Crimean War, but in 1261/1845 Aḥmad I Bey managed, with French diplomatic backing, to throw off the obligation to send tribute to Istanbul. The Porte still regarded the Ḥusaynids as linked with themselves, as local müshīrs, marshals of the army, and wālīs, governors, but the link was largely symbolic and was in any case ended in 1298/1881. Reckless spending by the Beys, abolition of the lucrative slave trade, an increased European commercial penetration of Tunisia plus administrative malpractices, brought Muḥammad Ṣādiq Bey to the verge of bankruptcy in 1286/1869, leading to the imposition of an international financial commission in order to regulate Tunisia’s debt. French pressure led to a military occupation of Tunisia in 1298/1881 followed by a Protectorate in 1300/1883, so that subsequent Beys functioned under a French Resident-General. At times, the Beys were able to give some impression of representing Tunisian national interests, despite their foreign origin; but in the twentieth century the nationalist movements of the Destour or Constitutionalists and then the Néo-Destour Parties became strong. In 1956, France agreed to the full independence of Tunisia, but the last Ḥusaynid, who was hailed as King of the Tunisians at Kairouan, ruled for only two months before he was forced out of his homeland by the Néo-Destour Party led by Habib Bourgiba (Ḥabīb Bū Ruqayba) and a republic was proclaimed.

The Beys displayed their dependence on the Ottoman by minting coins at Tunis only in the names of the Ottoman sultans, until in 1272/1856 Muḥammad II b. Ḥusayn II started the practice of adding his own name to that of the sultan; with the French occupation, the Beys and, later, the kings issued their own coins.

Zambaur, 84–5.

EI1 ‘Tunisia. 2. History’ (R. Brunschvig); EI2 ‘Ḥusaynids’ (R. Mantran).

P. Grandchamp, ‘Arbre généalogique de la famille hassanite (1705–1941)’, Rev. Tunisienne, nos 45–7 (1941), 233.

R. Mantran, ‘La titulature des beys de Tunis au XIXe siècle d’après les documents d’archives tures du Dar-el-Bey (Tunis)’, CT, nos 19–20 (1957), 341–8.

L. Carl Brown, The Tunisia of Ahmad Bey 1837–1855, Princeton 1974, with a chronological table of events at pp. xv–xviii.

Hugh Montgomery-Massingberd (ed.), Burke’s Royal Families of the World. II. Africa and the Middle East, London 1980, 225–9.

1123–1251/1711–1835

Tripolitania

| 1123/1711 | Aḥmad Bey I b. Yūsuf, Qaramānlī |

| 1157/1745 | Muḥammad b. Aḥmad |

| 1167/1754 | ‘Alī I b. Muḥammad |

| 1209/1795 | Aḥmad II b.‘Alī |

| 1210/1796 | Yūsuf b. ‘Alī, d. 1254/1838 |

| 1248–51/1832–5 | ‘Alī II b. Yūsuf |

| 1251/1835 | Re-establishment of Ottoman direct rule |

The Qaramānlīs were a line of Turkish soldiers apparently arising out of the Qulughlīs or products of mixed marriages between the Turkish Janissary units in North Africa and local women. In the prevailing chaos and internal strife characterising early eighteenth-century Ottoman Tripolitania, Aḥmad Qaramānlī (whose name may derive from the fact that he or his forebears came originally from Qaramān in Anatolia) seized power, eventually receiving from the sultan in Istanbul the titles of Beylerbey or governor and Pasha and establishing what was virtually an independent line. From Tripoli (Ṭarābulus al-Gharb), he extended his control over most of what is now Libya. He and his sons managed to control the local factions of the Turks and the Arabs, and, despite the fact that Tripoli was notoriously a base of the Barbary corsairs, concluded trade agreements with countries like Britain and France. In the early nineteenth century, various rivals for the succession within the ruling family were to seek support from one or other of these two powers. But the appearance of the French in Algeria after 1830 alarmed the Sublime Porte and, taking advantage of Qaramānlī dissensions, sultan Maḥmūd II sent an expedition against Tripoli which removed the Qaramānlīs and imposed a rule from Istanbul which lasted until the Italian seizure of Libya in the early twentieth century.

The Qaramānlīs used only coins in the names of the Ottoman sultans issued by the Tripoli mint.

Zambaur, 85.

EI1 ‘Karamānlī’ (R. Mantran).

24

THE SANŪSĪ CHIEFS AND RULERS

1253–1389/1837–1969

Eastern Sudan and Libya

| 1253/1837 | Sayyid Muḥammad b. ‘Alī, al-Idrīsi al-Sanūsī al-Kabīr, founder of the Sanūsiyya dervish order, d. 1275/1859 |

| 1276/1859 | Sayyid Muḥammad al-Mahdī b. Muḥammad b. ‘Alī al-Sanūsī |

| 1320/1902 | Sayyid Aḥmad al-Sharīf b. Muḥammad al-Sharīf (in 1336/1918 gave up military and political leadership, but retained spiritual primacy until his death at Medina in 1351/1933) |

| ⊘ 1336–89/1969 | Sayyid Muḥammad Idrīs b. Muḥammad al-Mahdī (initially as military and political leader; 1371/1951 King of Libya), d. 1401/1982 |

| 1389/1969 | Republican régime |

Muḥammad b.‘Alī, known as the ‘Great Sanūsī’, was born in Algeria towards the end of the eighteenth century. While studying in Fez, he was much influenced by Moroccan Ṣūfism, especially that of the Tijāniyya order; and later, while further studying in Ḥijāz, he joined several dervish orders himself and became an adherent of the Moroccan Ṣūfī and Sharīf Aḥmad b. Idrīs. In addition to this inclination towards mysticism, he developed reformist and innovatory ideas, and, after Aḥmad b. Idrīs’s death in 1253/183 7, organised in Mecca his own tarīqa or order, the Sanusiyya. Finding his homeland Algeria in the process of being taken over by the French, he settled in Cyrenaica, where direct Ottoman Turkish rule had recently been imposed in place of the local line of Qaramānlī Pashas (see above, no. 23). Moving into the desert interior rather than the coastlands, several zāwiyasor religious, educational and social centres for the Sanūsiyya were now founded there, including in 1272/1856 that of Jaghbūb near the Egyptian border. This was to be the headquarters of the order until 1313/1895, when it was moved southwards to the less accessible oasis of Kufra and, soon afterwards, to what is now northern Chad. The Sanūsī message appealed to the desert-dwellers of North Africa and the eastern Sudan. Veneration for the person of the Great Sanūsī accorded with the maraboutism and saint-worship of those regions, but the firm organisation of the order gave these enthusiasms effect and purpose. Expectations of a coming Mahdī, who would restore Islam to its pristine simplicity, were also rife, as events in Dongola were to show in the Mahdiyya movement there of the late nineteenth century. The Sanūsīs hoped for a reunion and regeneration of all Islamic peoples, and the Ottoman sultan ‘Abd al-Hamlī II (see below, no. 130) hoped to recruit their support for his Pan-Islamic policies. The Sanūsiyya did, in fact, have a strong missionary zeal, and zāwiyaswere founded in Ḥijāz, Egypt, Fezzān and as far south as Wadai and Lake Chad, the faith in this case following the trans-Saharan caravan routes.

The Sanūsīs were in the forefront of opposition to the French advance into Chad and the central Sudan, and for some twenty years after 1911 provided the driving power behind local Libyan resistance to the Italian invaders, especially in Cyrenaica. Italy’s entry into the First World War on the Allied side in 1915 inevitably inclined the Sanūsiyya to the Turkish cause, and the head of the order, Sayyid Aḥmad, had to leave for Istanbul in 1918; thereafter, the military struggle in Cyrenaica was left largely to local Sanūsī leaders. During the Second World War, the British government recognised Muḥammad Idrīs, who had been in exile in Egypt for twenty years, not merely as a spiritual head but also as Amīr or political head of the Sanūsīs of Cyrenaica. In 1371/1951 he became ruler of the independent federated kingdom of Libya, comprising Cyrenaica, Tripolitania and Fezzān; in 1382/1963 it became a unitary state. So far, the process of the Sanūsī family’s development from being heads of a religious movement to the headship of a modern Arab state had been somewhat reminiscent of the development of the Su‘ūdī state in Arabia (see below, no. 55) out of the Wahhābiyya, but the Idrīsid monarchy of Libya was destined to have only a short life. The new state failed to develop a political system which could accommodate the aspirations of the new classes and a social one which could cope with the new stresses resulting from the unprecedented Libyan oil boom of 1955 onwards. In 1969, King Idrīs was deposed by an army coup, and Libya became a republic under Colonel Mu‘ammar Gaddafi (Qadhdhāfī).

Zambaur, 89; EI2 ‘al-Sanūsī, Muḥammad b. ‘Alī’, ‘Sanūsiyya’ (J.-C. Triaud).

E. E. Evans-Pritchard, The Sanusi of Cyrenaica, Oxford 1949, with a genealogical table at p. 20.

N. A. Ziadeh, Sanūsīyah: A Study of a Revivalist Movement in Islam, Leiden 1959.

J. Wright, Libya: A Modern History, London 1981.