TWELVE

The Turks in Anatolia

473–707/1081–1307

Originally in west-central Anatolia, with their capital at Konya; later, in most of Anatolia except the western fringes

| 473/1081 | Sulaymān b. Qutalmïsh (Qutlumush) b. Arslan Yabghu |

| (478/1086 | Alp Arslan b. Sulaymān, in Nicaea) |

| 485/1092 | Qïlïch Arslan I b. Sulaymān, in Nicaea, k. 500/1107 |

| 502/1109 | Malik Shāh or Shāhānshāh b. Qïlïch Arslan I, in Malatya |

| ⊘ 510/1116 | Mas‘ūd I b. Qïlïch Arslan I, Rukn al-Dīn, in Konya |

| ⊘ 551/1156 | Qïlïch Arslan II b. Mas‘ūd I, ‘Izz al-Dīn, c. 581/c. 1185 divided his kingdom among his ten sons |

| ⊘ 588/1192 | Kay Khusraw I b. Qïlïch Arslan II, Ghiyāth al-Dīn, first reign |

| ⊘ 593/1197 | Sulaymān II b. Qïlïch Arslan II, Rukn al-Dīn |

| 600/1204 | Qïlïch Arslan III b. Sulaymān II, ‘Izz al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 601/1205 | Kay Khusraw I, second reign |

| ⊘ 608/1211 | Kay Kāwūs I b. Kay Khusraw I, ‘Izz al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 616/1220 | Kay Qubādh I b. Kay Khusraw I, ‘Alā’ al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 634/1237 | Kay Khusraw II b. Kay Qubādh I, Ghiyāth al-Dīn |

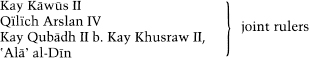

| ⊘ 644/1246 | Kay Kāwūs II b, Kay Khusraw II, ‘Izz al-Dīn |

| 646/1248 |

|

| ⊘ 647/1249 |

|

| 655/1257 |

|

| ⊘ 657/1259 | Qïlïch Arslan IV |

| ⊘ 663/1265 | Kay Khusraw III b. Qïlïch Arslan IV, Ghiyāth al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 681/1282 | Mas‘ūd II b. Kay Kāwūs II, Ghiyāth al-Dīn, first reign |

| ⊘ 683/1284 | Kay Qubādh III b. Farāmurz b. Kay Kāwūs II, ‘Alā’ al-Dīn, first reign |

| ⊘ 683/1284 | Mas‘ūd II, second reign |

| 692/1293 | Kay Qubādh III, second reign |

| 693/1294 | Mas‘ūd II, third reign |

| ⊘ 700/1301 | Kay Qubādh III, third reign, k. 702/1303 |

| ⊘ 702/1303 | Mas‘ūd II, fourth reign |

| 707/1307 | Mas‘ūd III b. Kay Qubādh III, Ghiyāth al-Dīn |

| 707/1307 | Mongol domination |

Soon after the Great Seljuq sultan Alp Arslan’s victory over the Byzantine emperor at Mantzikert, we hear of the activities in Anatolia of the four sons of another member of the Seljuq family, Qutalmïsh or Qutlumush, and it was the descendants of one of these sons, Sulaymān, who were to establish a local Seljuq sultanate in Anatolia based on Iconium or Konya. Sulaymān reached Nicaea or Iznik in the far north-west of Asia Minor, but the emergent Byzantine dynasty of the Comneni, aided by the First Crusaders, began to re-establish the Greek position in the west, and the seat of the Seljuq sultanate was eventually fixed at Konya in west-central Anatolia as the capital of what was for long to remain a landlocked principality. Sulaymān’s son Qïlïch Arslan I had ambitions in Diyār Bakr and Jazīra, but after his death his successors were left alone in Anatolia by the Great Seljuqs further to the east. The Little Armenian kingdom of Cilicia and the Franks in the county of Edessa were now attacked, and, from their base at Konya, Mas‘ūd I and Qïlïch Arslan II gained the preponderance over the rival amirate of the Dānishmendids (see below, no. 108). A Byzantine attack on Konya was avenged by Qïlïch Arslan II’s victory over the Greeks in 572/1176 at Myriocephalon near Lake Eğridir, after which the latter’s hopes of reconquering Anatolia faded; but in his old age, the sultan lost control over his sons, his territories became fragmented and in 586/1190 the emperor Frederick Barbarossa and the Third Crusaders temporarily occupied Konya.

The Latin conquest of Constantinople in 1204 afforded the Seljuqs an opportunity to re-establish their power. From being essentially a power of the Anatolian interior, they extended to the Mediterranean, and the port of Alanya or ‘Alā’iyya (thus named after ‘Alā’ al-Dīn Kay Qubādh I) was constructed. With this and the northern coastlands in Turkish hands, a flourishing transit trade between Egypt and the eastern Mediterranean, across Anatolia to the Black Sea, the Crimea and the lands of the Mongol Golden Horde (see below, no. 129), grew up after c. 1225, and commercial relations were begun with the Italian trading cities. The internal prosperity of the Rūm sultanate in these decades is shown by the architectural and cultural glories of Konya and other parts of Anatolia at this time. Thereafter, decline set in, with internal discontent marked by the rebellion of a charismatic dervish leader, Baba Isḥāq, in 638/1240; and, when the Mongols invaded eastern Anatolia, the Seljuqs were defeated at Köse Dagh to the east of Sivas in 641/1243. Thereafter, the Rūm sultanate became a client, tribute-paying state of the Mongol Il Khāns (see below, no. 128). After 676/1277, Mongol governors took direct control. The names of the Seljuqs continued to appear on coins up to 702/1303, but they had no real authority; the last ones may have reigned in Alanya, where Ottoman chronicles mention a Seljuq descendant in the fifteenth century. A new period in the history of Anatolia begins after 707/1307, one of fragmentation into a series of petty principalities or beyliks (see below, nos 106–24).

Lane-Poole, 155; Sachau, 16 no. 30; Khalīl Ed’hem, 216–17, 219; Zambaur, 143–4; Album, 29.

EI2‘Saldjūḳids. III. 5, IV. 2, V. 2, VII. 2’ (C. E. Bosworth).

Cl. Cahen, Pre-Ottoman Turkey. A General Survey of the Material and Spiritual Culture and History c. 1071–1330, London 1968, 73–138, 269–301.

O. Turan, Selçuklular zamanında Türkiye. Siyasi tarih Alp Arslan’dan Osman Gazi’ye (1071–1318), Istanbul 1971, 45ff., with a genealogical table at the end.

Before 490–573/before 1097–1178

Originally in north-central Anatolia, later also in eastern Anatolia

1. The line in Sivas ?–570/?–l175

Dānishmend Ghāzī, first mentioned in 490/1097, d. 497/1104 |

|

| ⊘ 497/1104 | Amīr Ghāzī Gümüshtigin b. Dānishmend |

| ⊘ 529/1134 | Muḥammad b. Amīr Ghāzī |

| ⊘ 536/1142 | Dhu ’1-Nūn b. Muḥammad, ‘Imād al-Dīn, first reign |

| ⊘ 537/1142 | Malik Yaghïbasan b. Amīr Ghāzī Gümüshtigin |

| 559/1164 | Malik Mujāhid Ghāzī b. Yaghïbasan, Abu ’1-Maḥāmid Jamāl al-Dīn |

| 562/1166 | Malik Ibrahīm b. Muḥammad, Shams al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 562/1166 | Malik Ismā‘īl b. Ibrāhīm, Shams al-Dīn |

| 567–70/1172–4 | Malik Dhu ’1-Nūn b. Muḥammad, now with the title Nāṣir al-Dīn, second reign |

| 570/1174 | Conquest by the Seljuqs of Rūm |

2. The line in Malatya and Elbistan

| ⊘ c. 537/c. 1142 | Ismā‘īl b. Amīr Ghāzī Gümüshtigin, ‘Ayn al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 547/1152 | Dhu ’1-Qarnayn b. Ismā‘īl |

| ⊘ 557/1162 | Muḥammad b. Ismā‘īl, Nāṣir al-Dīn, first reign |

| ⊘ 565/1170 | Qāsim b. Ismā‘īl, Fakhr al-Dīn |

| 567/1172 | Afrīdūn b. Ismā‘īl |

| 570–3/ll75–8 | Muḥammad, second reign |

| 573/1178 | Conquest by the Seljuqs of Rūm |

The centre of power of the Dānishmendids was originally in north-central Anatolia and Cappadocia, as far west as Ankara and around such centres as Tokat, Amasya and Sivas; they thus controlled the northerly route of Türkmen penetration across Asia Minor, while the Seljuqs of Rūm controlled the more southerly one. The Turkmen founder Dānishmend (Persian, ‘wise, learned man, scholar’) is an obscure figure who appears as a ghāzī or fighter for the faith in Anatolia, clashing in Cappadocia with the First Crusaders but also, in some degree, as a rival to the Seljuq Qïlïch Arslan I. He is the central figure of an epic romance, the Dānishmend-nāme, a. mixture of genuine traditions and legendary elements written down over two centuries after the events described in it, in which he is identified with the earlier Arab frontier warrior of Malatya, Sīdī Baṭṭāl. It is accordingly difficult to disentangle fact from fiction in the elucidation of Dānishmendid origins. The Dānishmendids were at least as powerful as the Seljuqs in the early twelfth century, and Amīr Ghāzī Gümüshtigin fought the Armenians in Cilicia and the Franks in the County of Edessa, and in 521/1127 captured Kayseri and Ankara; because of his warfare against the Christians, the ‘Abbāsid caliph al-Mustarshid bestowed on him the title of Malik ‘king’, making the Amīr a legitimate Muslim sovereign prince.

However, internal disputes among the sons and brothers of the dead Malik Muḥammad brought disunity, and after 536/1142 the Dānishmendid dominions were in effect partitioned between Yaghïbasan in Sivas, his brother ‘Ayn al-Dawla Ismā‘īl in Malatya and Elbistan and Dhu ’1-Nūn in Kayseri. After Yaghïbasan’s death, the Seljuq Qïlïch Arslan II intervened several times in the affairs of the Sivas branch, finally killing Dhu ’1-Nūn in 570/1174 and seizing his lands. At Malatya, the last Dānishmendid Muḥammad had to reign as a Seljuq vassal until Qïlïch Arslan II took over there himelf in 573/1178; according to the historian Ibn Bībī, the surviving Dānishmendids entered the service of the Seljuqs.

Justi, 455; Lane-Poole, 156 (both very fragmentary); Sachau, 15 no. 27; Khalīl Ed’hem, 220–3; Zambaur, 146–7; Album, 29.

EI2 ‘Dānishmendids’ (Irène Mélikoff); İA ‘Dânişmendliler’ (M. H. Yınanç), with a genealogical table.

CI. Cahen, Pre-Ottoman Turkey, 82–103.

O. Turan, Selçuklular zamanında Türkiye, 112–90.

Before 512 to mid-seventh century/before 1118 to mid-thirteenth century

Northern Anatolia, with centres at Erzincan, Divriği and Kemakh

| ? | Mengüjek Aḥmad, in Kemakh |

| before 512/before 1118 | Isḥāq b. Mengüjek |

| c. 536/c. 1142 | Division of the Mengüjekid territories |

1. The line in Erzincan and Kemakh

| c. 536/c. 1142 | Dāwūd I b. Isḥāq |

| ⊘ 560/1165 | Bahrām Shāh b. Dāwūd, al-Malik al-Sa‘īd Fakhr al-Dīn |

| 622–5/1225–8 | Dāwūd II b. Bahrām Shāh, ‘Alā’ al-Dīn |

| 625/1228 | Assumption of control by the Seljuqs of Rūm |

| c. 536/c. 1142 | Sulaymān I b. Isḥāq |

| ⊘ by 570/by 1175 | Shāhānshāh b. Sulaymān, Abu ’l-Muẓaffar Sayf al-Dīn |

| c. 593/c.l197 | Sulaymān II b. Shāhānshāh |

| c. 626/c. 1229 | Aḥmad b. Sulaymān II, Abu ’l-Muẓaffar Ḥusām al-Dīn |

| after 640/after 1242 | Malik Shāh b. Aḥmad, ruling in 650/1252 |

Conquest by the Seljuqs of Rūm |

This obscure ghāzī dynasty is not heard of until 512/1118, when Isḥāq b. Mengüjek, a relative by marriage of the Dānishmendids (see above, no. 108), menaced Malatya from his fortress at Kemakh near Erzincan. The Mengüjekid principality came to lie between those of the Dānishmendids on the west and of the Saltuqids (see below, no. 110) on the east, and included besides Kemakh and Erzincan the towns of Divriği and Kughūniya or Seben Karahisar. After Isḥāq’s death in 536/1142 his possessions were divided, in accordance with the old Turkish patrimonial concepts, between his sons, so that there were thenceforth two branches of the family. Bahrām Shāh of the Erzincan branch made his court there something of a cultural centre, and he was the mamdūḥ or dedicatee of works by the great Persian poets Niẓāmī and Khāqānī, while the rulers in Divriği have left behind there a remarkable mosque. The Mengüjekids clashed with the Rūm Seljuqs, and sought allies in such powers as the Byzantine rulers of Trebizond, but the power of the Konya sultans prevailed, and the last ruler in Erzincan, Dāwūd II, yielded up Erzincan and Kemakh to Kay Qubādh I in 625/128, exchanging them for lands at Akşehir and İlgin. The Divriği branch lasted rather longer and apparently persisted until the middle of the thirteenth century, their end being probably linked with the appearance in eastern Anatolia of the Mongols.

Sachau, 14 no. 25; Khalīl Ed’hem, 224–6; Zambaur, 145–6; Bosworth–Merçil–İpşirli, 279–82.

EI2 ‘Mengüček’ (Cl. Cahen); İA ‘Mengücükler’ (F. Sümer), with a genealogical table.

O. Turan, Doğu Anadolu Türk devletleri tarihi, 55–79, 242 (list), 278 (genealogical table).

Late fifth century to 598/late eleventh century to 1202

Eastern Anatolia, with their capital at Erzurum

| late fifth century/ | |

| late eleventh century | Saltuq I, Abu ’1-Qāsim |

| 496/1102 | ‘Alī b. Saltuq I |

| c. 518/c. 1124 | Abu ’1-Muẓaffar Ghāzī, Ḍiyā’ al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 526/1132 | Saltuq II b. ‘Alī, ‘Izz al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 563/1168 | Muḥammad b. Saltuq II, Nāṣir al-Dīn |

| between 587/1191 | |

| and 597/1201 | Māmā Khātūn bt. Saltuq II |

| c. 597–8/c. 1201–2 | Abū Manṣūr b. Muḥammad, ‘Alā’ al-Dīn, or Malik Shāh b. Muḥammad |

| 598/1202 | Conquest by the Seljuqs of Rūm |

The origins of this family are obscure, but Saltuq was apparently one of the Turkmen commanders operating in Anatolia in the last decades of the eleventh century. His son ‘Alī appears in history controlling a principality based on Erzurum and other towns in the district, including at times Kars (Qarṣ); the Saltuqids were to embellish Erzurum, a flourishing centre of the transit trade across northern Anatolia, with fine buildings. From ‘Alī onwards, these begs enjoyed the title of Malik. The Saltuqids’ main role in the political and military affairs of the time was in warfare with the Georgians, expanding southwards from the time of their king David the Restorer (1089–1125), often as allies of the Shāh-i Armanids (see above, no. 97); but in a curious episode, Muḥammad b. Saltuq II’s son offered to convert to Christianity in order to marry the celebrated Queen T‘amar of Georgia. The last years of the family are unclear, but in 598/1102 the Rūm Seljuq Sulaymān II, while en route for a campaign against the Georgians, put an end to the Saltuqids; and for some thirty years after this, Erzurum was to be ruled by two Seljuq princes as an appanage before Kay Qubādh I in 627/1230 incorporated it into his sultanate.

Khalīl Ed’hem, 227–8; Zambaur, 145; Bosworth–Merçil–İpşirli, 283–4.

EI2 ‘Saltuḳ Oghullari’ (G. Leiser).

Cl. Cahen, Pre-Ottoman Turkey, 106–8.

Faruk Sümer, ‘Saltuklular’, SAD, 3 (1971), 391–433, with a genealogical table at p. 394.

O. Turan, Selçuklular zamanında Türkiye, 251–4.

idem, Doğu Anadolu Türk devletleri tarihi, Istanbul 1973, 3–52, 241 (list), 277 (genealogical table).

111

THE QARASÏ (KARASÏ) OGHULLARÏ

c. 696–c. 761/c. 1297–c. 1360

South-western Anatolia

| ? | Qarasï Beg b. Qalem Beg |

| ? | ‘Ajlān Beg b. Qarasï, d. c. 735/c. 1335 |

| c. 730/c. 1330 | Demir Khān, in Balıkesir |

Yakhshï Khān, Shujā‘ al-Dīn (? Dursun), in Bergama |

|

| c. 747/c. 1346 | Ottoman annexation |

Sulaymān b. Demir Khān, in Trova and Çanakkale in 758/1357 |

This line of Begs established itself in the classical Mysia, namely the coasts and hinterland along the Asian coast of the Dardanelles and along the territory to the south, with centres at Balıkesir and Bergama. A connection of the Qarasï Begs with the Dānishmendids (see above, no. 108) is almost certainly legendary. The family probably constituted their principality in the early fourteenth century, becoming a naval power in the Aegean and the Sea of Marmora, putting pressure on Byzantium across the Dardanelles and thus paving the way for the Ottomans’ crossing into Europe. After annexation by the Ottomans – the first stage in the territorial aggrandisement of that family – at least one Qarasï Beg seems to have retained some power, perhaps as a vassal, since several of the Qarasï commanders rallied to the Ottoman side; but in the absence of any inscriptions, and with few coins, much about this short-lived dynasty remains obscure.

Khalīl Ed’hem, 274–5; Zambaur, 150; Bosworth–Merçil–İpşirli, 309–11.

EI2 ‘Karasi’ (Cl. Cahen); İA ‘Karası-Oğulları’ (İ. H. Uzunçarşılı).

İ. H. Uzunçarşılı, Anadolu beylikleri ve Akkoyunlu, Karakoyunlu devletleri, Ankara 1969, 96–103.

c. 713–813/c. 1313–1410

Western Anatolia

| ⊘ c. 713/c. 1313 | Ṣarukhān Beg b. Alpagï, d. after 749/1348 |

| ⊘ c. 749/c. 1348 | Ilyās b. Ṣarukhān, Fakhr al-Dīn |

| ⊘ by 758/by 1357 | Isḥāq Chelebi b. Ilyās, Muẓaffar al-Dīn, d. c. 790/c. 1388 |

| ⊘ c. 790–2/c. 1388–90 | Khiḍr Shāh b. Isḥāq, first reign |

| 792/1390 | Ottoman annexation |

| ⊘ 805/1402 | Orkhan b. Isḥāq |

| ⊘ after 807–13/ | |

| after 1404–10 | Khiḍr Shāh, second reign |

| 813/1410 | Definitive Ottoman annexation |

The Ṣarukhān family of begs ruled over the agriculturally rich coastal province of classical Lydia, Ṣarukhān Beg having conquered Magnesia or Manisa in c. 713/ c. 1313. From there his family became, together with the neighbouring begs of Aydïn (see below, no. 113), a naval power in the Aegean, involved with the Genoese and Byzantines, and also, after the middle years of the century, acquiring a common frontier with the Ottomans after the latter’s annexation of the principality of Qarasï (see above, no. 111). The Ottoman Bāyazīd I annexed the Ṣarukhān principality, but it was restored by Tīmūr immediately after his victory at Ankara in 804/1402 over the sultan, only to be definitively re-annexed by the Ottomans eight years later, after which Manisa became the residence of one of the Ottoman princes.

Khalīl Ed’hem, 276–8; Zambaur, 150; Bosworth–Merçil–İpşirli, 323–5.

EI2 ‘Ṣarūkhān’ (Elizabeth A. Zachariadou); İA ‘Saruhan-Oğulları’ (M. Çağatay Uluçay).

İ. H. Uzunçarşılı, Anadolu beylikleri, 84–91.

708–829/1308–1426

Western Anatolia

| ⊘ 708/1308 | Muḥammad Beg, Mubāriz al-Dīn Ghāzī |

| ⊘ 734/1334 | Umur I Beg b. Muḥammad, Bahā’ al-Dīn Ghāzī |

| 749/1348 | Khiḍr b. Muḥammad |

| ⊘ c. 761–92/c. 1360–90 | ‘Īsā b. Muḥammad |

| 792/1390 | Ottoman annexation |

| 805/1402 |

|

| ⊘ 805/1403 | Umur II b. ‘Īsā |

| ⊘ 808–29/1405–26 | Junayd b. Ibrāhīm Bahādur b. Muḥammad |

| 829/1426 | Definitive Ottoman annexation |

The family of Aydïn Oghlu Muḥammad Beg, who had been a commander in the army of the Germiyān Oghullarï (see below, no. 116), had their principality on the coasts and in the hinterland of western Anatolia, the classical Maeonia, with their centre at Aydïn or Tralleia, the later Güzel Hisar, a region through which ran the lower course of the Büyük Menderes river. Thus it lay between the amirates of Ṣarukhān to the north and Menteshe to the south. Umur I Beg captured Izmir or Smyrna and made the Aydïn Begs an important naval power against the Latin Christians in the Aegean, so that he became the hero of a destān or epic. The principality was annexed by Bāyazīd I but restored by Tīmūr. The last amīr, Junayd, supported the Ottoman counter-sultan Düzme Muṣṭafā (see below, no. 130), but was defeated by Murād II, and Aydïn was incorporated into the Ottoman empire.

Khalīl Ed’hem, 279–80; Zambaur, 151; Bosworth–Merçil–İpşirli, 287–9.

EI2 ‘Aydin-Oghlu’ (Irène Mélikoff); İA ‘Aydın’ (Besim Darkot and Mükrimin Halil Yınanç).

İ. H. Uzunçarşılı, Anadolu beylikleri, 104–20.

E. A. Zachariadou, Trade and Crusade: Venetian Crete and the Emirates of Menteshe and Aydin (1300–1415), Venice 1983.

Late seventh century to 847/late thirteenth century to 1424

South-western Anatolia

| c. 679/c. 280 | Menteshe Beg |

| by 695/by 1296 | Mas‘ūd b. Menteshe Beg |

Qaramān b. Menteshe Beg, in Föke or Finike in Lycia |

|

| c. 719/c. 1319 | Orkhan b. Mas‘ūd, Shujā‘ al-Dīn |

| ⊘ c. 745/c. 1344 | Ibrāhīm b. Orkhan |

| c. 761/c. 1360 | Division of territories among Ibrāhīm’s sons Mūsā (d. by 777/1375), Muḥammad and Tāj al-Dīn Aḥmad (d. 793/1391) |

| 793/1391 | Ottoman annexation |

| ⊘ 805/1402 | Ilyās b. Muḥammad b. Ibrāhīm, Muẓaffar al-Dīn or Shujā‘ al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 824–7/1421–4 |

|

| 827/1424 | Definitive Ottoman annexation |

This family occupied the coasts and hinterland of south-western Anatolia, the classical Caria, with their centres at Milas or Mylasa, Pechin, Balāṭ or Miletus, etc. Menteshe Beg’s father may have been amīr-i sawāḥil or ruler of the coastlands for the later Seljuqs of Rūm, but the family emerges into history only towards the end of the thirteenth century. During the next century, the Menteshe amīrs were involved in maritime and land operations against the Venetians and the Knights Hospitaller in Rhodes, including a struggle over possession of Smyrna. Their principality was taken over by the Ottoman sultan Bāyazīd I after its eastern neighbours, the principalities of the Germiyān and Ḥamīd Oghullarï, had already passed into Ottoman hands, but was restored by Tīmūr. However, Ilyās Beg was forced to recognise the suzerainty of the Ottoman Muḥammad I, and in 827/1424 Murād II finally annexed Menteshe to his empire.

Khalīl Ed’hem, 283–5; Zambaur, 153–4; Bosworth–Merçil–İpşirli, 313–16.

EI2 ‘Menteshe Oghullari’ (E. Merçil); İA ‘Menteşe-Oğulları’ (İ. H. Uzunçarşılı).

P. Wittek, Das Fürstentum Mentesche, Istanbul 1934.

İ. H. Uzunçarşılı, Anadolu beylikleri, 70–83.

E. A. Zachariadou, Trade and Crusade: Venetian Crete and the Emirates of Menteshe and Aydin.

659–769/1261–1369

Deñizli in south-western Anatolia

| 659/1261 | Muḥammad Beg, k. 660/1262 |

| 660/1262 | ‘Alī Beg, k. 676/1278 |

| 675/1277 | Occupation by the Ṣāḥib Atā and Germiyān Oghullarï |

| ? | Inanj Beg b. ‘Alī, Shujā‘ al-Dīn, ruling in 714/1314, d. after 734/1334 |

| ⊘ c. 735/c. 1335 | Murād Arslan b. Inanj Beg |

| ⊘ by 761–by 770/ | |

| by 1360–by 1369 | Isḥāq Beg b. Murād Arslan |

| ? | Rule of the Germiyān Oghullarï |

The town of the interior of south-western Anatolia, Lādīq or Ladik, classical Laodicea, in the fourteenth century replaced by the nearby foundation of Toñuzlu/Deñizli, was a frontier post between the amirates of Menteshe and Germiyān. It had passed into Seljuq hands from the Byzantines in 657/1259, and in the following century a local Turkmen beg, Muḥammad, made it the centre of a small beylik. Coming under the control of the Germiyān Oghullarï, it was granted to their kinsman Inanj Beg and held by his descendants for two more generations until the Germiyān Oghullarï took it into their own hands again shortly before their own principality was annexed by the Ottomans in 792/1390.

Khalīl Ed’hem, 295; Zambaur, 152; Bosworth–Merçil–İpşirli, 311–13.

EI2 ‘Deñizli’ (Mélikoff).

İ. H. Uzunçarşılı, Anadolu beylikleri, 55–7.

O. Turan, Selçuklular zamanında Türkiye, 514–18.

By 699–832/by 1299–1428

Western Anatolia

| by 699/by 1299 | Ya‘qūb I b. Karīm al-Dīn ‘Alī Shīr |

| ⊘ after 727/after 1327 | Muḥammad Chakhshadān b. Ya‘qūb |

| ⊘ by 764/by 1363 | Sulaymān Shāh b. Muḥammad |

| ⊘ 789–92/1387–90 | Ya‘qūb II Chelebi b. Sulaymān, first reign |

| 792/1390 | Ottoman annexation |

| ⊘ 805/1402 | Ya‘qūb II Chelebi, second reign |

| 814/1411 | Qaramānid occupation |

| 816–32/1413–28 | Ya‘qūb II Chelebi, third reign, as an Ottoman vassal |

| 832/1428 | Definitive Ottoman annexation |

The Germiyān were originally a Turkish tribe first heard of in the service of the Seljuqs of Rūm at Malatya. But in the late thirteenth century they moved into western Anatolia and founded a beylik based on Kütahya as vassals of the Seljuqs and of the latter’s suzerains the Il Khanids. The decay of the Seljuqs allowed the founder of the Germiyān Oghullarï, Ya‘qūb I, to form the most extensive and powerful Turkish principality of its time in western Anatolia, embracing the greater part of classical Phrygia and taking advantage of the trade routes through the Menderes basin. Also, he exercised suzerainty over neighbouring amīrs, such as those of Aydïn (see above, no. 113), and had the Emperor of Byzantium as his tributary. However, in the second half of the fourteenth century Germiyān was cut off from access to the Aegean by the growth of the maritime beyliks along the coast, and became squeezed between the Ottomans to the north and the Qaramānids to the south-east. The last amīr, Ya‘qūb II, lost his principality to Bāyazīd I in 792/1390, but was restored by Tīmūr after the battle of Ankara; eventually, however, he bequeathed his lands to the Ottomans, so that after his death, Murād II took over Germiyān.

Khalīl Ed’hem, 292–4; Zambaur, 152; Bosworth–Merçil–İpşirli, 301–3.

EI2 ‘Germiyān-Oghullari’ (Irène Mélikoff); İA ‘Germiyan-Oğulları’ (İ. H. Uzunçarşılı).

İ. H. Uzunçarşılı, Anadolu beylikleri, 39–54.

c. 670–c. 742/c. 1271–c. 1341

West-central Anatolia

| c. 670/c. 1271 |

|

| after 676/after 1277 | Muḥammad b. Ḥasan Nuṣrat al-Dīn, Shams al-Dīn |

| 686–c. 742/1287–c. 1341 | Aḥmad b. Muḥammad, Nuṣrat al-Dīn |

| c. 742/c. 1341 | Annexation by the Germiyān Oghullarï |

The Ṣāḥib Atā Oghullarï ruled a small principality centred on Afyon Karahisar and lying between the beyliks of the Germiyān Oghullarï and the Ḥamīd Oghullarï. They derived their name from the vizier of the Rūm Seljuqs Fakhr al-Dīn ‘Alī, called Ṣāḥib Atā (d. 687/1288), whose two sons received various march towns, including Kütahya and Akşehir, and then, more permanently, Ladik and Afyon Karahisar. Their descendants were latterly only strong enough to survive under the protection of the Germiyān Oghullarï, who towards the middle of the fourteenth century incorporated their lands into their own beylik.

Khalīl Ed’hem, 273; Zambaur, 148; Bosworth–Merçil–İpşirli, 321–3.

EI2 ‘Ṣāḥib Atā Oghullari’ (C. H. Imber).

İ. H. Uzunçarşılı, Anadolu beylikleri, 150–2.

Cl. Cahen, Pre-Ottoman Turkey.

118

THE ḤAMĪD OGHULLARÏ AND THE TEKKE OGHULLARÏ

c. 700–826/c. 1301–1423

West-central Anatolia and the south-western coastland

1. The Ḥamīd Oghullarï line in Eğridir

| c. 700/c. 1301 | Dündār Beg b. Ilyās b. Ḥamīd, Falak al-Dīn |

| 724–8/1324–7 | Occupation by the Il Khānid governor Temür Tash b. Choban |

| 728/1327 | Khiḍr Beg b. Dündār |

| 728/1328 | Isḥāq b. Dündār, Najm al-Dīn |

| by 745/by 1344 | Muṣṭafā b. Muḥammad b. Dündār, Muẓaffar al-Dīn |

| ? | Ilyās b. Muṣṭafā, Ḥusām al-Dīn |

| c. 776–93/c. 1374–91 | Ḥusayn b. Ilyās, Kamāl al-Dīn |

| 793/1391 | Ottoman annexation |

2. The Tekke Oghullarï line in Antalya

| 721/1321 | Yūnus b. Ilyās b. Ḥamīd |

| ? | Maḥmūd b. Yūnus, d. 724/1324 |

| 727/1327 | Khiḍr b. Yūnus, Sinān al-Dīn |

| by 774/by 1372 | Muḥammad b. Maḥmūd, Mubāriz al-Dīn, d. after 779/after 1378 |

| ? | ‘Uthmān (‘Othmān) Chelebi b. Muḥammad, first reign |

| c. 793/c. 1391 | Ottoman annexation |

| 805–26/1402–23 | ‘Uthmān Chelebi, second reign |

| 826/1423 | Definitive Ottoman annexation |

Ilyās b. Ḥamīd was, like his father, a Turkish frontier commander of the Seljuqs, who carved out for himself a principality based on Eğridir in the classical interior region of Pisidia and also in the southern coastal regions of Lydia and Pamphylia, in the latter regions based on Antalya. The Ḥamīd Oghullarï thus came to control an important north–south trade route across western Anatolia. Two sons of Ilyās established themselves in the northern Ḥamīd principality and the southern Tekke one respectively. The first was definitively annexed by Bāyazīd I in c. 793/ c. 1391, but Tekke, likewise absorbed by the Ottomans, was restored by Tīmūr, only to be finally ended in 826/1423 when the Ottomans defeated and killed the last ruler, ‘Uthmān Chelebi.

Khalīl Ed’hem, 286, 289–91; Zambaur, 153; Bosworth–Merçil–İpşirli, 304–6.

EI1 ‘Teke-eli’, ‘Teke-oghlu’ (F. Babinger), EI2 ‘Ḥamīd or Ḥamīd Oghullari’ (X. de Planhol); İA ‘Ḥamîd-Oğulları’ (İ. H. Uzunçarşılı), ‘Teke-Oğulları’ (M. C. Şihâbettin Tekindağ).

İ. H. Uzunçarşılı, Anadolu beylikleri, 62–9.

692–876/1293–1471

The southern Anatolian coastland

| 692/1293 | Maḥmūd, Majd al-Dīn or Badr al-Dīn, governor for the Qaramānids |

| 730–7/1330–7 | Yūsuf, governor for the Qaramānids |

| ? | Sawchï b. Muḥammad Shams al-Dīn |

| ⊘ ? | Qaramān b. Sawchï |

| 830/1427 | Mamlūk occupation of Alanya |

| ? | Luṭfī b. Sawchï, ruling in 848/1444 |

| c. 865–76/c. 1461–71 | Qïlïch Arslan b. Luṭfī |

| 876/1471 | Ottoman annexation |

The port of Alanya received its earlier name of ‘Alā’iyya from the Seljuq sultan ‘Alā’ al-Dīn Kay Qubādh I, who conquered it in 617/1220. After 692/1293, it was controlled by the Qaramānids (see below, no. 124), whose representatives there bore at times the title of amīr al-sawāḥil ‘commander of the coastlands’, but on one occasion in the later fourteenth century it was controlled by the Lusignan kings of Cyprus. In the early fifteenth century it was for a while in the hands of the Mamlūks of Egypt, then governed by a descendant of the Rūm Seljuqs until in 876/1471 it was conquered by the Ottomans.

Bosworth–Merçil–İpşirli, 285–6.

EI2 ‘Alanya’ (F. Taeschner).

İ. H. Uzunçarşılı, Anadolu beylikleri, 92–5.

120

THE ASHRAF (ESHREF) OGHULLARÏ

?–726/?–1326

South-central Anatolia

Sulaymān I b. Ashraf (Eshref), Sayf al-Dīn, regent in Konya 684/1285, d. 702/1302 |

|

| ⊘ 702/1302 | Muḥammad b. Sulaymān, Mubāriz al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 720–6/1320–6 | Sulaymān II Shāh b. Muḥammad |

| 26/1326 | Il Khānid annexation |

Sulaymān Ashraf Oghlu was a commander in the service of the Seljuqs who, in the period of decay of the sultans in Konya, built up a a small principality centred on Beyşehir in the classical Pisidia. His successors extended to other towns in the region, such as Akşehir and Bolvadin, but the beylik was brought under Il Khānid obedience by the Mongols’ governor for Anatolia Temür Tash b. Choban, who killed the last ruler in Beyşehir. After Temür Tash’s own death, the lands of the principality were divided between the Ḥamīd Oghullarï and the Qaramānids.

Khalīl Ed’hem, 287–8; Zambaur, 154; Bosworth–Merçil–İpşirli, 299–300.

EI2 ‘Ashraf Oghullari’ (İ. H. Uzunçarşılı).

İ. H. Uzunçarşılı, Anadolu beylikleri, 58–61.

121

THE JĀNDĀR OGHULLARÏ OR ISFANDIYĀR (ISFENDIYĀR) OGHULLARÏ

691–866/1292–1462

The Black Sea coastland

| 691/1292 | (?) Yaman (b.) Jāndār, Shams al-Dīn |

| ⊘ c. 708/c. 1308 | Sulaymān I b. Yaman, Shujā‘ al-Dīn |

| c. 740/c. 1340 | Ibrāhīm b. Sulaymān, Ghiyāth al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 746/1345 | ‘Ādil b. Ya‘qūb b. Yaman |

| ⊘ c. 762/c. 1361 | Bāyazīd Kötörüm b. ‘Ādil, Jalāl al-Dīn, after 786/1384 ruler in Sinop |

| ⊘ 786/1384 | Sulaymān II Shāh b. Bāyazīd, ruler in Kastamonu |

| 787/1385 | Isfandiyār (Isfendiyār) b. Bāyazīd, Mubāriz al-Dīn, ruler in Sinop, first reign |

| 795/1393 | Ottoman annexation |

| ⊘ 805/1402 | Isfandiyār, ruler in Kastamonu, Sinop and Samsun, second reign |

| ⊘ 843/1440 | Ibrāhīm b. Isfandiyār, Tāj al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 847/1443 | Ismā‘il b. Ibrāhīm, Kamāl al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 865–6/1461–2 | Qïzïl Aḥmad b. Ibrāhīm |

| 866/1462 | Ottoman annexation |

The founder of this line of beys, Shams al-Dīn (?) Yaman b. Jāndār, seized power in Kastamonu and held it under the aegis of the Il Khānids, establishing an extensive principality along the Black Sea coastland and in its hinterland, the classical Paphlagonia. After the mid-fourteenth century, the Jāndār Oghullarï threw off Il Khānid suzerainty and extended to Sinop, but lost their territories to the Ottoman sultan Bāyazīd I. The dynasty at this point also takes its additional name of Isfandiyār (Isfendiyār) Oghullarï from one of the beys of the period, Isfandiyār (and in the sixteenth century, the family were to claim the name also of Qïzïl Aḥmadlï). Restored by Tīmūr, the principality had nevertheless gradually to cede territory to the Ottomans, and was finally annexed by Muḥammad II. Under subsequent sultans, the Jāndār family were nevertheless to enjoy much favour and power in the state.

Khalīl Ed’hem, 306–7; Zambaur, 149; Bosworth–Merçil–İpşirli, 290–3.

EI2 ‘Ḳasṭamūnī’ (C. J. Heywood), ‘Isfendiyār Oghlu’ (J. H. Mordtmann*).

İ. H. Uzunçarşılı, Anadolu beylikleri, 121–47.

676–722/1277–1322

Sinop, on the Black Sea coast

| 676/1277 | Muḥammad b. Sulaymān Mu‘īn al-Dīn Parwāna, Mu‘īn al-Dīn |

| 696/1297 | Mas‘ūd b. Muḥammad, Muhadhdhib al-Dīn |

| 700–22/1301–22 | Ghāzī Chelebi b. Mas‘ūd |

| 722/1322 | Annexation by the Jāndār Oghullarï |

This short-lived line was made up of the descendants of Mu‘īn al-Dīn Sulaymān, who had been the virtual ruler in the weakened Seljuq sultanate of Rūm after the Seljuq defeat of Köse Dagh at the hands of the Mongols in 641/1243 (see above, no. 107), his title of Parwāna meaning ‘personal aide to the sultan’. After his execution in 676/1277, his descendants established a small beylik in Sinop and Tokat, in the Black Sea coast and in its hinterland, where the Parwāna had his personal domains, and this existed until after the death in 722/1322, when the last of the line died without male heir and Sinop passed to the Jāndār Oghullarï (see above, no. 121).

Khalīl Ed’hem, 272; Zambaur, 147; Bosworth–Merçil–İpşirli, 316–18.

EI2 ‘Mu‘īn al-Dīn Sulaymān Parwāna’ (Carole Hillenbrand).

Cl. Cahen, Pre-Ottoman Turkey, 312–13.

İ. H. Uzunçarşılı, Anadolu beylikleri, 148–9.

O. Turan, Selçuklular zamanında Türkiye, 617–31.

Nejat Kaymaz, Pervâne Mu‘înü’d-Dîn Süleyman, Ankara 1970.

c. 624–c. 708/c. 1227–c. 1309

Kastamonu (Qasṭamūnī)

| by c. 624/c. 1227 | Chobān, Husām al-Dīn |

| ? | Alp Yürük b. Chobān, Ḥusām al-Dīn |

| before 679/1280 | Yülük Arslan b. Alp Yürük, Muẓaffar al-Dīn |

| 691–c. 709/1292–c. 1309 | Maḥmūd b. Yülük Arslan, Nāṣir al-Dīn |

| c. 709/c. 1309 | Annexation by the Jāndār Oghullarï |

Chobān, apparently from the Qayï tribe of the Oghuz, was a commander in the service of the Seljuqs who became governor of Kastamonu, probably from 608/1211 onwards, and was entrusted by ‘Alā’ al-Dīn Kay Qubādh I with command of an expedition against the Crimea in 622/1225. His successors seem to have enjoyed a sporadic and limited authority in Kastamonu under Seljuq and then Il Khānid suzerainty, the latter exercised through their representative Mu‘īn al-Dīn Sulaymān Parwāna (see above, no. 122), but the region eventually passed to the Jāndār Oghullarï (see above, no. 121).

Zambaur, 148; Bosworth–Merçil–İpşirli, 272–3.

EI2 ‘Ḳasṭamūnī’ (C. J. Heywood).

Cl. Cahen, Pre-Ottoman Turkey, 243–4, 310–12.

O. Turan, Selçuklular zamanında Türkiye, 608–13.

124

THE QARAMĀN OGHULLARÏ OR QARAMĀNIDS

c. 654–880/c. 1256–1475

South-central Anatolia and the Mediterranean coastland

| c. 654/c. 1256 | Qaramān b. Nūr al-Dīn or Nūra Ṣūfī |

| 660/1261 | Muḥammad I b. Qaramān, Shams al-Dīn |

| 677/1278 | Güneri Beg b. Qaramān, with Maḥmūd b. Qaramān as his subordinate ruler |

| 699/1300 | Maḥmūd b. Qaramān, Badr al-Dīn |

| 707/1307 | Yakhshï b. Maḥmūd |

| c. 717/c. 1317 | Ibrāhīm I b. Maḥmūd, Badr al-Dīn, vassal of the Mamlūks, with other Qaramānid princes governing various towns of the principality |

| between 745/1344 | |

| and 750/1349 | Aḥmad b. Ibrāhīm I, Fakhr al-Dīn, d. by 750/1349 |

| ⊘ by 750/by 1349 | Shams al-Dīn b. Ibrāhīm I |

| 753/1352 | Sulaymān b. Khalīl b. Maḥmūd b. Qaramān |

| ⊘ 762–800/1361–98 | ‘Alā’ al-Dīn b. Khalīl |

| 800/1398 | Ottoman annexation |

| ⊘ 804/1402 | Muḥammad II b. ‘Alā’ al-Dīn, first reign |

| ⊘ 822/1419 | ‘Alī b. ‘Alā’ al-Dīn, first reign |

| ⊘ 824/1421 | Muḥammad II, second reign |

| ⊘ 826/1423 | ‘Alī, second reign |

| ⊘ 827/1424 | Ibrāhīm II b. Muḥammad II, Tāj al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 869/1464 |

|

| ⊘ 870–80/1465–75 | Pīr Aḥmad |

| 880/1475 | Definitive Ottoman annexation |

(Qāsim b. Ibrāhīm, Ottoman vassal until his death in 888/1483) |

The Qaramānids were the most powerful and enduring of the Turkish dynasties of Anatolia which grew up alongside the Ottomans but were eventually absorbed by them. It seems that they arose from the Afshār tribe of Turkmens and that the father of Qaramān, Nūr al-Dīn, was a well-known Ṣufī shaykh; the dynasty would thus resemble certain other Anatolian lines which sprang from dervish origins. Their original centre was in the Ermenek-Mut region in the north-western Taurus Mountains, where they were somewhat rebellious vassals of the Seljuq sultan of Konya, Rukn al-Dīn Qïlïch Arslan IV, and then tenacious opponents of the Mongol Il Khānid attempts to dominate Anatolia. These endeavours continued into the fourteenth century, and by then the Qaramānids, definitely an independent power which, as heir to the Seljuqs, controlled much of southern and central Anatolia, at one point acknowledged the suzerainty of the Mamlūks of Egypt and Syria, who were their neighbours on the east after the Mamlūk reduction of the Little Armenian kingdom of Sis. Larande or Karaman (Qaramān), the original capital of the Qaramānids before their acquisition of Konya, became an important centre of literary and artistic activity, and, in modern Turkish eyes at least, the Qaramānids have achieved some fame for their encouragement of Turkish instead of Persian as the language of administration.

Relations with the Ottomans were inevitably uneasy, and after ‘Alā’ al-Dīn b. Khalīl was defeated and killed by Bāyazid, the Qaramānid territories fell to the Ottomans. However, they were restored by Tīmūr, and after the Ottomans’ absorption of the Germiyān Oghullarï of north-western Anatolia in 832/1428 and the Jāndār or Isfandiyār Oghullarï of the Black Sea coastlands in 866/1462 (see above, nos 116, 121), they formed the Ottomans’ most serious rivals for power in Anatolia. The last great Qaramānid ruler, Tāj al-Dīn Ibrāhīm II, was drawn into the nexus of Mediterranean powers, Christian and Muslim, opposing Ottoman expansionism. The alliance of the ‘Grand Caraman’ was sought by Venice and the Papacy and by their eastern neighbours, the Aq Qoyunlu of Uzun Ḥasan (see below, no. 146), and the Ottoman pretender Prince Jem was later supported. But internal disputes favoured Ottoman intervention, with Sultan Muḥammad II’s goal being the absorption of the Qaramānid lands, and this was achieved by 880/1475, when the dynasty was extinguished.

It should be noted that, from 692/1293 onwards, a branch of the Qaramānids controlled Alanya or ‘Alā’iyya (see above, no. 114).

Lane-Poole, 184; Khalīl Ed’hem, 296–302; Zambaur, 158, 160.

EI2 ‘Karamān-Oghullari’ (F. Sümer); ĪA ‘Karamanhlar’ (M. C. Sihâbeddin Tekindağ).

Cl. Cahen, Pie-Ottoman Turkey.

Ī. H. Uzunçarşih, Anadolu beylikleri, 1–38.

736–82/1336–80

North-eastern Anatolia

| ⊘ 736/1336 | Eretna b. Ja‘far, ‘Alā’ al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 753/1352 | Muḥammad I b. Eretna, Ghiyāth al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 767/1366 | ‘Alī b. Muḥammad, ‘Ala‘ al-Dīn |

| 782/1380 | Muḥammad II Chelebi b. ‘Alī |

| 782/1380 | Rule and eventual succession in Sinop (Sīnūb) of Qāḍī Burhdn al-Dīn |

Eretna (whose name has been explained as possibly stemming ultimately from Sanskrit ratna ‘jewel’) was a commander of Uyghur origin (hence from eastern Turkestan), probably in the service of the Chobanids and their suzerains the last Il Khānids. After the fall of Temür Tash b. Chobān (see above, no. 120), Eretna was able to assemble an extensive principality stretching from Ankara in the west and Samsun (Ṣāmsūn) in the north to Erzincan (Erzinjān) in the east, with its capital first at Sivas (Sīwās) and then at Kayseri (Qayṣariyye), and under the protection of the Mamlūks of Egypt and Syria. After his death, however, the lands of Eretna were nibbled away by the Ottomans in the west and the Aq Qoyunlu in the east, and authority in their lands was effectively exercised by Qāḍī Burhān al-Dīn, who in 782/1380 ended the line of Eretna and instituted his own short-lived beylik based on Sivas (see below, no. 126).

Khalīl Ed’hem, 384–6; Zambaur, 155; Bosworth-Merçil-İpşirli, 297–9.

EI2 ‘Eretna’ (cl.cahen); ‘Erenta’İA (İ. H. Uzunçarşili).

İ. H. Uzunçarşih, Anadolu beylikleh, 155–61.

d126

THE QĀDĪ BURHĀN AL-DĪN OGHULLARÏ

783–800/1381–98

North-eastern Anatolia

| ⊘ 783/1391 | Aḥmad b. Muḥammad Shams al-Dīn, Qāḍī Burhān al-Dīn |

| 800/1398 | ‘Alī Zayn al-‘Ābidīn b. Aḥmad, ‘Alā’ al-Dīn |

| 800/1398 | Ottoman annexation |

Qāḍī Burhān al-Dīn stemmed from an originally Oghuz family settled in Kayseri, and became vizier and atabeg to the weak, later rulers of the Eretna Oghullarï (see above, no. 125) until, shortly after the demise of the last of that line, he personally assumed power in their dominions. In the midst of a life spent in ceaseless military activity, defending his beylik against the Ottomans, Qaramānids and other local rivals, and also against the Mamlūks and Aq Qoyunlu, he found time to function actively as a scholar and poet. However, after his death at the hands of the Aq Qoyunlu, the notables of Sivas eventually handed over the city to the Ottoman Bāyazīd I.

Khalīl Ed’hem, 387–8; Zambaur, 155; Bosworth-Merçil-İpşirli, 307–9.

EI2 ‘Sīwās’ (S. Faroqhi); İA ‘Kadi Bürhaneddin’ (Mirza Bala).

İ. H. Uzunçarşih, Anadolu beylikleri, 162–8.

Yaşar Yücel, Kadi Burhaneddin ve devleti (1344–1398), Ankara 1970.

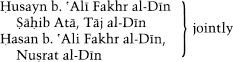

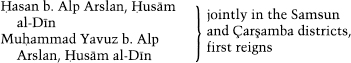

c. 749–831/c. 1348–1428

The region of Canik (Jānīk), in the hinterland of the Black Sea coast

| c. 749/c. 1348 | Tāj al-Dīn b. Doghan Shāh |

| 789–800/1387–98 | Maḥmūd b. Tāj al-Dīn, in Niksar, d. 826/1423 |

| 796/1394 | Alp Arslan b. Tāj al-Dīn, in part of the Niksar district |

| 796/1396 |

|

| 800/1398 | Ottoman annexation |

| 805–31/1402–28 |

|

| 831/1428 | Definitive Ottoman annexation |

The region of Canik lay to the south of Samsun, and it was at Niksar, on the southern slopes of the Pontic range, that the Türkmen beg Tāj al-Dīn, whose father Doghan Shāh had been influential under the Il Khānids in eastern Anatolia, established a small principality on his father’s death. He contracted a protective marriage alliance with the Byzantine kingdom of Trebizond on his eastern borders, but was unable to fend off the attacks of Qāḍī Burhān al-Dīn of Sivas (see above, no. 126), and his son submitted to the Ottomans. Tāj al-Dīn’s grandsons were restored by Tīmūr, but eventually handed over their principality to Sultan Murād II.

Bosworth-Merçil-İpşirli, 326–8.

İ. H. Uzunçarşih, Anadolu beylikleri, 153–4.

c. 780–1017/c. 1378–1608

Cilicia and Little Armenia

Ramaḍān Beg, mentioned in 754/1353 |

|

| by 780/by 1378 | Ibrāhīm I b. Ramaḍān Beg, Ṣārim al-Dīn |

| 785/1383 | Aḥmad b. Ramaḍān Beg, Shihāb al-Dīn |

| 819/1416 | Ibrāhīm II b. Aḥmad, Ṣārim al-Dīn |

| 821/1418 | Ḥamza b. Aḥmad, ‘Izz al-Dīn |

| 832/1429 | Muḥammad I b. Aḥmad |

| ? | Eylük, d. 843/1439 |

| in 861/1457 | Dündār |

| ? | ‘Umar |

| 885/1480 | Khalīl b. Dāwūd b. Ibrāhīm II, Ghars al-Dīn |

| 916/1510 | Maḥmūd b. Dāwūd |

| 922/1516 | Ottoman suzerainty imposed |

| 922/1516 | Selīm b. ‘Umar |

| 922/1516 | Qubādh b. Khalīl |

| c. 923/c. 1517 | Pīrī Muḥammad b. Khalīl |

| 976/1568 | Darwīsh b. Pīrī Muḥammad |

| 977/1569 | Ibrāhīm III b. Pīrī Muḥammad |

| 994/1586 | Muḥammad II b. Ibrāhīm III |

| 1014–17/1605–8 | Pīrī Manṣūr b. Muḥammad II |

| 1017/1608 | Ottoman annexation |

The eponym Ramaḍān Beg is said to have been from the Oghuz, but this line of rulers in Cilicia, with its capital at Adana, only comes into historical focus with Ramaḍān Beg’s son Ṣārim al-Dīn Ibrāhīm I, who helped the Dulghadïr Oghullarï and Qaramānids (see below, no. 129, and above, 124) against the Mamlūks. Subsequently, the Ramaḍān Oghullarï oscillated between support for the Mamlūks and the Qaramānids but with generally a pro-Mamlūk policy, and they formed a buffer-state between the Mamlūks and the Ottomans. But the Ottoman sultan Selīm I, en route for his campaign against Mamlūk Syria in 922/1516, brought the Ramaḍān Oghullarï into submission, and the later rulers of the family functioned as governors for the Ottomans in Adana, until at the opening of the seventeenth century Adana was fully incorporated into the Ottoman empire as an eyālet or province, with a governor appointed from Istanbul.

Sachau, 16 no. 29; Khalīl Ed’hem, 313–17; Zambaur, 157; Bosworth–Merçil–İpşirli, 318– 20.

EI2 Adana’ (F. Taeschner), ‘Ramaḍān Oghullari’ (F. Babinger*); İA ‘Ramazan-Oğullari’ (F. Sümer).

İ. H. Uzunçarşih, Anadolu beylikleri, 176–9.

129

THE DULGHADÏR OGHULLARÏ OR DHU ‘L-QADRIDS

738–928/1337–1521

South-eastern Anatolia

| 738/1337 | Qaraja b. Dulghadïr, al-Malik al-Ẓāhir Zayn al-Dīn |

| 754/1353 | Khalīl b. Qaraja, Ghars al-Dīn |

| 788/1386 | Sha‘bān Sūlī b. Qaraja |

| 800/1398 | Muḥammad b. Khalīl, Nāṣir al-Dīn |

| 846/1442 | Sulaymān b. Muḥammad |

| 858/1454 | Malik Arslan b. Sulaymān |

| 870/1465 | Shāh Budaq, first reign |

| 871/1466 | Shāh Suwār b. Sulaymān |

| 877/1472 | Shāh Budaq, second reign |

| 884/1479 | Bozqurdb. Sulaymān, ‘Alā’ al-Dawla |

| 921–8/1515–21 | ‘Alī b. Shāh Suwār |

| 928/1521 | Ottoman annexation |

The founder of this line of rulers in the Taurus Mountains and upper Euphrates region, with its centres at Maraş (Mar’ash) and Elbistan (Albistān), was an Oghuz chief, Qaraj b. Dulghadïr (the latter Turkish name, of uncertain meaning, being later Arabised or rendered by folk etymology as Dhu ’l-Qadr ‘Powerful, mighty’), who led Turkmen bands into the region of Little Armenia. His successors maintained their position, at times as vassals of the Mamlūks, and survived the attacks of Tīmūr. In the fifteenth century they maintained good relations with both the Ottomans, as enemies of the Qaramānids, and the Mamlūks, and resisted pressure from the Aq Qoyunlu ruler Uzun Ḥasan (see below, no. 146). The potentates of Istanbul and Cairo struggled for influence in this region of south-eastern Anatolia and supported rival candidates for power in Elbistan and Maraş. But Selīm I’s victories over the Mamlūks in 922–3/1516–17 tipped the scales decisively in favour of the Ottomans, who ended the Dulghadïr line shortly afterwards and transformed their beylik into the Dhu ’l-Qadriyya governorate.

Sachau, 15–16 no. 28; Khalīl Ed’hem, 308–12; Zambaur, 158; Bosworth–Merçil-İpşrli, 294–6.

EI2 ‘Dhul-Kadr’ (J. H. Mordtmann and V. L. Ménage); İA ‘Dulkadirhlar’ (J. H. Mordtmann and Mükrimin Halil Ymanç).

I. H. Uzunçarşılı, Anadolu beylikleri, 169–75.

Late seventh century to 1342/late thirteenth century to 1924

Original nucleus in north-western Anatolia, subsequently rulers of an empire embracing all Anatolia, the Balkans and the Arab lands from Iraq to Algeria and southwards to Eritrea

The beginnings of the Ottomans are shrouded in legend, and few firm historical facts are known before 1300. Numismatic evidence now seems to show that Ertoghrul actually existed, but the name ‘Uthmān or ‘Othmān, which gave its designation to the dynasty, may well be an adaptation to the prestigious name of the third Rightly-Guided Caliph (see above, no. 1) from an originally Turkish name like Atman. According to one tradition, the family stemmed from the Qayi clan of the Oghuz and led a nomadic group in Asia Minor. Whatever their exact origins, they were clearly part of the prolonged wave of Turkmens who came in from the east and gradually pushed the Byzantines back. The Ottomans had been loosely attached to the Seljuq sultans of Konya, but the appearance in Anatolia of the Mongol Il Khānids and the consequent decline of the Seljuqs during the later thirteenth century probably impelled various Turkmen groups to move westwards into the remaining lands in north-western Asia Minor of the Byzantines, who had been desperately weakened by the Latin occupation of Constantinople. An older view, embodying the views of the Austrian scholar Paul Wittek, was that the Ottomans, whose lands were in the classical Bithynia (the later Ottoman province of Hüdavendigâr (Khudāwendigār)), acquired a particular dynamism from their role there as frontier ghāzīs, so that this superior élan and zeal for the spreading of the Islamic faith enabled them eventually to triumph over all the other beyliks of Anatolia and to put an end to the Byzantine empire. But the Ottomans seem rather to have been just the most successful of several beyliks of Turkmen origin established in western Anatolia and involved in the intricate politics of the region, inspired more by secular love of plunder than by Islamic fervour.

At all events, they were able to expand against the Greeks and Italians of the Aegean and Marmara seas region, and from a base at Gelibolu or Gallipoli, captured in 755/1354, the Ottomans began the conquest of south-eastern Europe, taking advantage of the disunity of the Balkan Slavs and the religious emnities there of Orthodox and Catholics. Soon they had overrun a large part of the Balkans, and these conquests were eventually formed into the province of Rūmeli or Rumelia. Indicative of the Ottomans’ new concentration on Europe rather than on Asia was the removal of their capital from Bursa to Edirne or Adrianople in 767/1366. Militarily, they came to depend less and less on their Türkmen followers, whose religious sympathies were often heterodox. There arose a feudal cavalry element which was allotted estates off which to live, but most important in creating an image for Christian Europe of Ottoman ferocity and invincibility were the Janissaries (Yeñi Cheri ‘New Troops’), who were recruited from the children of the subject Christian population of the Balkans, converted to Islam and trained as an élite military force. In 796/1394, Bāyazīd I secured from the fainéant‘ Abbāsid caliph in Cairo, al-Mutawakkil I (see above, no. 3, 3), the title of Sultan of RüBm, thereby formally making himself heir to the Seljuqs in Anatolia; but his Asiatic empire was suddenly shattered by the onslaught of Tīmūr and his Turco-Mongol forces, who defeated the sultan at Ankara in 805/1402. Tīmūr restored many of the beyliks recently swallowed up by Bāyazīd, and it was some decades before the Ottoman empire in Anatolia was reconstituted, the Qaramānids (see above, no. 124) being the last major rival to be absorbed; meanwhile, Muḥammad II the Conqueror had finally captured Constantinople in 857/1453.

The sixteenth century was the golden age of the empire. In 922–3/1516–17, Salīm I the Grim conquered Syria and Egypt from the decadent rule of the Mamlūks; after the victory of Mohács in 932/1526, Sulaymān the Magnificent brought most of Hungary under Turkish rule for over a century and a half; footholds were secured in southern Italy, and corsair principalities established in Tunis and Algiers. On the eastern borders, the Shī‘ī ṣafawids, bitter rivals of the Ottomans (see below, no. 148), were defeated at Chāldirān in north-western Azerbaijan in 920/1514 and Azerbaijan itself invaded; in the Indian Ocean, Turkish naval forces operated from South Arabian bases against the incoming Portuguese.

The Ottomans ruled over a multi-ethnic empire, and at the peak of their strength they maintained an attitude of detached tolerance towards the millets or religious and ethnic minorities within their lands, so that Jews, for instance, resorted thither from persecution in Christian Central Europe and the Iberian peninsula. It was only towards the end of the seventeenth century that the tide began to turn definitely against the Turks in eastern Europe. They had failed to take much advantage of the European powers’ preoccupation with the Thirty Years’ War, and their only major success at this time was the capture of Crete from Venice. Yet the Ottomans were only just repulsed from Vienna in 1094/1683, and the losses of Hungary and Transylvania still left them in control of the Slav, Greek, Albanian and Rumanian parts of the Balkans. European political and diplomatic divisions and jealousies masked the Ottomans’ decline and preserved their empire for two more centuries, at a time when European technical skills had by then given them a clear military and naval superiority. The sultans endeavoured tentatively to modernise their forces, but it was not until 1241 /1826 that Maḥmūd II was able to break the power of the Janissaries, by now an undisciplined force hostile to all military reform. Economically, the Turkish and Arab lands began to suffer from the competition of western manufactured goods and superior commercial techniques; indigenous production declined, internal sources of revenue decreased and, in the nineteenth century, as the sultans contracted expensive European-type tastes, the empire at times tottered on the edge of bankruptcy.

Russian expansionism was an especial threat, for by the end of the eighteenth century the Russians had subdued the Ottomans’ allies, the Crimean Tatars (see below, no. 135, 1), so that the Black Sea was no longer a Turkish lake, and the Tsars were anxious to gain control of Istanbul and the Straits, thus acquiring access to the Mediterranean. In the opening years of the nineteenth century, the commander Muḥammad ‘ Alī became governor and virtually autonomous ruler in Egypt (see above, no. 34); the Greeks revolted and by 1829 had their independence recognised; and Algeria was lost to the French. The growth of nationalist and ethnic sentiment engendered by the French Revolution and its aftermath led the Balkan peoples to rebel against Turkish rule, and, by the end of the Second Balkan War of 1912–13, Turkey in Europe was reduced to its present region of eastern Thrace. Turkey’s ill-advised participation in the First World War on the side of the Central Powers caused the loss of the Arab provinces, so that the terms of the Treaty of Sévres (1920) brought about a major redrawing of boundaries in the Near East. Also, European powers were tempted to make claims on what was genuinely ethnic Turkish territory, and a Greco-Turkish War was provoked. All these events brought about a reaction of Turkish national feeling, one aspect of which was a weariness with the Ottoman ruling house, by now largely dominated by the European powers’ control in Istanbul; the dynasty was increasingly felt by those Turkish Nationalists who rallied in Ankara, away from the cosmopolitan atmosphere of the capital, as a bar to progress and as inextricably bound up with the reverses and humiliations of the previous two centuries. Under the stimulus of the Nationalist leader Muṣṭafā Kemāl (the later Atatürk ‘Father of the Turkish nation’), first the Ottoman sultanate was abolished in 1922 and then, in 1924, the caliphate was ended and the last Ottoman,‘ Abd al-Majīd II, deposed and exiled.

Lane-Poole, 186–97; Khalīl Ed’hem, 320–30; Zambaur, 160–1 and Table O.

EI2 ‘‘ Othmānli. 1. Political and dynastic history’ (C. E. Bosworth, E. A. Zachariadou and J. H. Kramers*).

A. D. Alderson, The Structure of the Ottoman Dynasty, Oxford 1956.

Halil Inalcik, The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age 1300–1600, London 1973.

M. A. Cook (ed.), A History of the Ottoman Empire, Cambridge 1976.

S. J. and Ezel Kural Shaw, History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey, Cambridge 1976–7.

R. Mantran (ed.), Histoire de l‘empire Ottoman, Paris 1989.