THIRTEEN

The Mongols and their Central Asia and Eastern European Successors

The recorded history of the Mongols begins only at the end of the twelfth and the beginning of the thirteenth centuries, for it is only with the thirteenth-century Secret History of the Mongols and some Persian and Chinese sources of that time that any historical records become available. It seems, however, that the Mongols were originally a forest people, inhabiting the Siberian and Outer Mongolian forest fringes around Lake Baikal and the river basins to the south-east of it, rather than steppe nomads, even though it is as steppe conquerors, moving swiftly on horseback across vast distances, that they first appear in history. It also seems that the Mongols were, from the outset, intermingled and intermarried with the Turkish tribes of what is now Mongolia, so that the whole of the movements and conquests of the Mongols ought more properly to be described as those of the Turco-Mongols.

The father of Chingiz (in Mongolian, Chinggis), Yesügey, was the minor chieftain of a Mongol clan. Chingiz was perhaps born around 1167, and originally had the name Temüjin (= ‘blacksmith’). He rose to prominence in Mongolia through the patronage of a chief of the Turkish Kereyt tribe, Toghrïl, Wang or Ong Khān (Qa’an) (the Prester John of Marco Polo). Later, Temüjin quarrelled with Toghrïl, and defeated in battle first Toghrïl and then a Mongol rival Jamuqa. He had already acquired the title of Chinggis (? < Turkish tengiz ‘sea’ = ‘Oceanic, Universal [Qa’an or Khān]’), and at a Quriltay or assembly of Turco-Mongol chiefs in 1206 was acclaimed as Supreme Chief of all the Turco-Mongol peoples. He now expanded beyond the confines of Mongolia, and undertook campaigns against the Tibetan Tanguts of the Kansu and Ordos regions of north-western China, and in 1213 invaded China proper, sacking the northern capital of the Chin Emperors in 1215 and undermining their position. Turning westwards now, an invasion of Semirechye in 1218 gave Chingiz a common frontier with the territories of the Islamic Khwārazm Shāhs (see above, no. 89, 4). There had already been peaceful diplomatic contacts, but the incident at Utrār on the Syr Darya in 615/1218, when the Khwārazmian governor there massacred Chingiz’s envoys and a whole caravan of Muslim merchants accompanying them, precipitated the Mongol invasion of the Islamic lands. In 616–17/1219–20, Transoxania was conquered; Chingiz’s son Toluy was sent into Khurasan, and, after a momentary reverse at Parwān in Afghanistan, the last Khwārazm Shāh, Jalāl al-Dīn, was pursued into India (618/1221). Meanwhile, two other sons, Jochi and Chaghatay, were operating in the region of the lower Syr Darya and Khwārazm, destroying the homeland of the Shāhs; for the last years of his life, Jalāl al-Dīn was a fugitive, fleeing ever westwards before the Mongols.

It was the custom of Mongol chiefs to distribute sections of their territories to other members of their families, and this Chingiz had done before his death in 624/1227, allotting each of them a stretch of pasture ground (a yurt or nuntuq) for their followers and herds. The territories which the Mongols had already overrun were too vast to be ruled as a centralised state, and the Mongols themselves were politically and administratively quite unsophisticated; the Mongol language was not yet at this time a written one. Hence a bureaucracy had to be hastily improvised for the conquered lands, if only to divide up booty and to collect taxation for the khāns. The official classes of these lands, Khitan, Uyghur, Chinese and Persian, were drawn upon, and the Buddhist Uyghur Turkish secretaries, the bitikchis, were especially noteworthy. It is from two Persian Muslims in the Mongol service, ‘Aṭā’ Malik Juwaynī and Rashīd al-Dīn Fadl Allāh, that much of our knowledge of the early Mongols and their history comes.

Chingiz’s lands were accordingly divided among his four sons or their heirs in the following way.

(1) The eldest, Jochi, in fact died just before his father; it was the traditional steppe nomad practice to grant the pasture grounds farthest away from the home camp to the eldest son. Jochi’s inheritance now passed to his own son Batu. Jochi’s allocation had been of western Siberia and the Qipchaq steppe, extending into southern Russia and including also Khwārazm, which had always been linked culturally and commercially with the lower Volga lands. His son Batu founded the Blue Horde in South Russia, nucleus of the later Golden Horde, while Jochi’s eldest son, Orda, founded the White Horde in western Siberia, these two groups being united in the fourteenth century. At a later date, various khanates in Russia and Siberia evolved from the Hordes (see below, nos 136–8), while in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the descendants of another of Jochi’s sons, Shïban, namely the Shïbānids or Özbegs, made themselves masters of Khwārazm and Transoxania (see below, no. 153).

(2) The second son, Chaghatay, was given the Central Asian lands to the north of Transoxania, roughly those which had been held by the Qara Khitay and which came to be known now as Mogholistan, and extending into Eastern or the later Chinese Turkestan; to these were added Transoxania itself during Ögedey’s reign. The western branch of Chaghatay’s descendants in Transoxania soon came within the Islamic religious and cultural sphere of influence, but was brought under the control of Tīmūr Lang; the eastern branch in Semirechye, the Ili basin and across the T’ien Shan mountains in the Tarim basin, was more resistant to Islam. However, the eastern descendants of Chaghatay eventually helped to spread Islam in Eastern Turkestan, and they ruled there until the later seventeenth century (see below, no. 132).

(3) The third son Ögedey had been favoured by Chingiz during his lifetime as his future successor as Great Khān, and this was confirmed in 627/1229 by a Quriltay of Mongol chiefs. But within a generation the Supreme Khanate fell into the hands of the descendants of Toluy, although Ögedey’s grandson Qaydu retained his territories in the Pamirs and T’ien Shan, was recognised by the Chaghatayids and remained hostile to the Tolu‘id Great Khan Qubilay until Qaydu’s death in 703/1304.

(4) The youngest son Toluy had received, following traditional steppe practice as otchigin ‘guardian of the hearth’, the heartland of the empire, Mongolia itself. His sons Möngke and Qubilay followed Ögedey’s line as Great Khāns, but only Möngke retained the newly-built centre of Qaraqorum in Mongolia as his capital. The Great Khāns’ possessions included the Chinese conquests, where the Mongols became known as the Yuan dynasty and reigned until the second half of the fourteenth century. The cultural and religious attractions of Chinese civilisation proved strong for the Great Khāns in their northern Chinese capital of Peking; they became Buddhists, and their adherence to this faith, which was to become the dominant one in Mongolia itself, gradually opened up a breach with the subordinate Mongol khāns in western Asia and Russia, who adopted Islam in varying stages. It was one of Qubilay’s brothers, Hülegü, who launched a fresh wave of conquest upon the Islamic world and who founded the Il Khānid line in Persia; thus the khanates of western Asia ceased, for all practical purposes, to acknowledge the authority of the Great Khāns back in Mongolia and in Peking.

EI2 ‘Mongols’ (D. O. Morgan).

R. Grousset, L’empire des steppes, Paris 1939, Eng. tr. The Empire of the Steppes. A History of Central Asia, New Brunswick NJ 1970.

J. J. Saunders, The History of the Mongol Conquests, London 1971.

B. Spuler, The Mongols in History, London 1971.

D. O. Morgan, The Mongols, Oxford 1986.

131

THE MONGOL GREAT KHĀNS, DESCENDANTS OF ÖGEDEY AND TOLUY, LATER THE YŪAN DYNASTY OF CHINA

602–1043/1206–1634

Mongolia and the conquests made from there, then in Mongolia and China, then in Mongolia alone

⊘ 602/1206 |

Chinggis (Chingiz), son of Yesügey, d. 624/1227 |

⊘ 626/1229 |

Ögedey Khān, son of Chingiz |

⊘ 639/1241 |

Töregene Khātūn, widow of Ögedey, as regent 644/1246 Güyük, son of Ögedey |

646/1246 |

Güyük, son of Ögedey |

646/1248 |

Oghul Ghaymish, widow of Güyük, as regent |

⊘ 649/1251 |

Möngke (Mengü), son of Toluy, d. 657/1259 |

⊘ 658/1260 |

Qubilay, son of Toluy |

⊘ (658–62/1260–4 |

Ariq Böke, son of Toluy, rival Khān in Mongolia) |

693/1294 |

Temür Öljeytü, son of Chen-chin (Jim Gim) and grandson of Qubilay |

706/1307 |

Qayshan Gülük (Hai-shan), son of Darmabala, son of Chen-chin, and great-grandson of Qubilay |

711/1311 |

Ayurparibhadra (Ayurbarwada) or Buyantu, son of Darmabala |

720/1320 |

Suddhipala Gege’en or Gegen (Shidebala), son of Buyantu |

723/1323 |

Yesün Temür, son of Kammala, son of Chen-chin |

728/1328 |

Arigaba (Aragibag), son of Yesün Temür |

728/1328 |

Jijaghatu Toq Temür, son of Qayshan Gülük, first reign |

729/1329 |

Qoshila Qutuqtu, son of Qayshan Gülük |

729/1329 |

Jijaghatu Toq Temür, second reign |

733/1332 |

Rinchenpal (Irinchinbal), son of Qoshila |

733–71/1333–70 |

Toghan Temür, son of Qoshila |

|

The Great Khāns in China replaced by the Ming dynasty in 770/1368, but the line of Toluy’s descendants continuing in Mongolia until the seventeenth century |

Ögedey’s reign was one of resumed, triumphal conquest. That of northern China and what is now Manchuria, with the overthrow of the Chin dynasty and the annexation of Korea, was achieved, though it was not until 1279 that the Sung rulers of southern China were finally extinguished. At the other end of the Old World, Batu was raiding the South Russian steppes and central Europe, terrorising mediaeval Christendom (see below, no. 134, 1). Although Ögedey’s son Güyük had numerous offspring, the supreme khanate passed on Güyük’s death in April 1248 eventually to another line, that of Möngke and the descendants of Toluy. When Möngke’s brother Qubilay was hailed as Great Khān by a Quriltay in Mongolia which rival branches of the family did not attend, the descendants of Ögedey broke out in revolt, and under Qaydu and his son Chapar were for long an embarassment to the Great Khāns. They submitted in the end to the family of Toluy, but in later times various members of the house of Ögedey were raised to power in periods of revolution and unrest, and the great Tīmūr (see below, no. 144) set up two of these in Transoxania, Soyurghatmïsh and his son Maḥmūd, to replace the Chaghatayids there.

The Great Khāns in Qaraqorum and, after Möngke’s time, in Peking or Khān baliq (= ‘City of the Khāns’) led a life of a certain barbarian splendour, as the accounts of travellers and vistors from Western Europe like Marco Polo and from the Near East like the Armenian king Hayton show. Material wealth and plunder gained from the Mongol conquests flowed into the capital; artisans and craftsmen were gathered there; scholars, writers and religious leaders made their way to the khāns’ encampment. The Mongols displayed the traditional steppe tolerance of religions, or indifference to them, and were willing to give a hearing to the arguments of Latin and Nestorian Christians, Muslims, Buddhists and Confucianists. Inevitably, in Mongolia and northern China, the original animistic shamanism of the Mongols gave way to one of the higher religions, in fact to Buddhism in the Tibetan Lamaist form. This became and has remained the dominant religion of the Mongols of Eastern Asia, and was even carried westwards to the Volga and Kuban river regions by the Oyrot Mongols or Kalmucks in their great migration of the early seventeenth century.

The Mongol Great Khāns gradually settled down to being yet another Chinese dynasty of barbarian origin, the Yüan, considered in traditional Chinese historiography as the Twentieth Official Dynasty and as ruling from 1280 onwards. They ruled in China until in 1368 they were replaced by the native Ming, but well before that they had ceased to have much influence over the Mongol khanates of central and western Asia. Only in Mongolia did the descendants of the Great Khāns survive with some independence, though under the general suzerainty of the Ming emperors.

Lane-Poole, 201–16; Zambaur, 241–3; Album, 43.

EI2 ‘Čingiz-Khān’JJ. A. Boyle), ‘Kubilay’ (W. Barthold and J. A. Boyle), ‘Öldjeytü’ (D. O. Morgan); Eir ‘Čengīz’(D. O. Morgan).

L. Hambis, Le chapitre CVII du Yuan Che, les généalogies impériales mongoles dans I’histoire chinoise officielle de la dynastie mongole (= Supplement to TP, 38, Leiden 1945), 51–2, 71–3, 85–9, 106–9, 114–17, 128–32, 136–44. 153–5, 157–8 (tables based on both Chinese and Persian sources).

F. W. Cleaves, ‘The Mongol names and terms in the History of the Nation of Archers by Grigor of Akanc‘’, HJAS, 12 (1949), 400–43.

J. A. Boyle, ‘On the titles given in ![]() uvainī to certain Mongol princes’, HJAS, 19 (1956), 14654.

uvainī to certain Mongol princes’, HJAS, 19 (1956), 14654.

idem, The Successors of Genghis Khan, translated from the Persian of Rashīd al-Dīn, New York and London 1971, with a genealogical table at p. 342.

D. O. Morgan, The Mongols, with genealogical tables at pp. 222–3.

132

THE CHAGHATAYIDS, DESCENDANTS OF CHAGHATAY

624–764/1227–1363

Transoxania, Mogholistan including Semirechye, and eastern Turkestan

⊘ 624/1227 |

Chaghatay, son of Chingiz |

⊘ 642/1244 |

Qara Hülegü, son of Mö’etüken, son of Chingiz, first reign |

⊘ 644/1246 |

Yesü Möngke, son of Chaghatay |

649/1251 |

Qara Hülegü, second reign 0 650/1252 Orqina Khātün, widow of Qara Hülegü |

⊘650/1252 |

Orqina Khātün, widow of Qara Hülegü |

⊘ 658/1260 |

Alughu, son of Baydar, son of Chaghatay |

664/1266 |

Mubarak Shāh, son of Qara Hülegü |

664/1266 |

Mubārak Shah, son of Qara Hülegü |

⊘ c.664/c. 1266 |

Baraq, Ghiyāth al-Dīn, son of Yesūn Du’a, son of Mö’etüken |

670/1271 |

Negübey (Nīkpāy), son of Sarban, son of Chaghatay |

⊘ 670/1272 |

Buqa or Toqa Temür, son of Qadaqchi Sechen and great-grandson of Mö’etüken |

⊘ c. 681/c. 1282 |

Du’a (Duwa), son of Baraq |

706/1306 |

Könchek, son of Du’a |

708/1308 |

Taliqu, son of Qadaqchi Sechem and great-grandson of Mö’etüken |

709/1309 |

Kebek (Kopek), son of Du‘a, first reign |

⊘ 709/1309 |

Esen Buqa, son of Du‘a |

⊘ c. 720/c. 1320 |

Kebek, second reign |

⊘ 726/1326 |

Eljigedey, son of Du’a |

726/1326 |

Du’a Temür, son of Du’a |

⊘ 726/1326 |

Tarmashirīn, ‘Alā’ al-Dīn, son of Du’a |

734/1334 |

Buzan, son of Du’a Temür |

⊘ 734/1334 |

Changshi, son of Ebügen, son of Du’a |

⊘ c. 739/c. 1338 |

Yesün Temür, son of Ebügen |

⊘ (742–4/1341–3 |

‘Alī Khalīl (Allāh), descendant of Ögedey) |

⊘ c. 743/c. 1342 |

Muhammad, son of Pūlād, son of Könchek |

⊘ 744/1343 |

Qazan, son of Yasa’ur, son of Du’a, k. 747/1347 |

⊘ 747/1346 |

Dānishmendji, son of ‘Ali Sulṭān, descendant of Ögedey |

⊘ 749/1358 |

Buyan Quli, son of Surughu Oghul, son of Du’a, k. 759/1358 |

760/1359 |

Shāh Temür b. ‘Abdallāh b. Qazghan |

⊘ 760–4/1359–63 |

Tughluq Temür, ? son of Esen Buqa |

764/1363 |

Domination of Tīmūr Lang over the Western Chaghatay Khanate, with the Eastern Khanate remaining in power until the later seventeenth century |

After Chingiz’s death, Chaghatay had great prestige as the oldest surviving son and as an acknowledged expert on the Mongol tribal law, the Yasa; he was, indeed, strongly anti-Muslim and insisted on enforcing those prescriptions of the Yasa which ran counter to the Muslim Sharī‘, for example over the slaughtering of animals for meat and over ablutions in running water. Chaghatay’s appanage straddled the T’ien Shan mountains from the Uyghur lands in the east to Soghdia in the west, but the Chaghatay khanate was not really founded until after Chaghatay’s own death. His sons and grandsons quarrelled among themselves and conspired against the Great Khān Möngke, and according to William of Rubruck, the Flemish friar who travelled to the Mongol court at Qaraqorum, the whole Mongol empire was divided c. 1250 between Möngke and Batu, son of Jochi. The real founder of the Chaghatay khanate was Chaghatay’s grandson Alughu, who took advantage of the civil war between Möngke’s sons Qubilay and Arïgh Böke to seize Khwārazm, western Turkestan and Afghanistan, nominally for Arïgh Böke but in fact for himself. These territories became the nucleus of the khanate, which continued now in a slightly reduced form, nominally subject to the Great Khāns but in fact until the end of the thirteenth century sharing influence in Central Asia with Qaydu, the grandson of Ögedey, until the latter’s death in 702/1303.

From their geographical position, the Chaghatayids were less directly under the influence of Islam than their relatives in Persia, the 1l Khānids (see below, no. 133), and preserved their tribal and nomadic ways much longer. These facts may have contributed to the general decline of urban life and agriculture in Central Asia outside the oases of Transoxania and Eastern Turkestan. The short-reigned Mubārak Shāh (664/1266) was the first Chaghatay id definitely to adopt Islam, but from c. 681/c. 1282 Du’a and his descendants were fiercely pagan and resided in the eastern territories of the khanate. Kebek was the first to return to Transoxania, where he built a palace at Nakhshab or Qarshi (< Mongol ‘palace’). Tarmashīrīn (whose name in this Persianised form enshrines a Buddhist Sanskrit one like Dharmasila ‘Having the habit of the Dharma or Buddhist law’) became a Muslim, but the strongly anti-Islamic nomadic Mongols of the eastern part of the khanate rose against him and killed him in 734/1334.

The unity of the Chaghatayids began to disintegrate soon after this, as Tīmūr Lang rose to power in Transoxania. Various Chaghatayids were placed on the throne in Transoxania by the Turkish amīrs, and then after 764/1363 some descendants of Ögedey were set up by Tīmūr. The Chaghatayids nevertheless survived, and after Tīmūr’s death their fortunes revived in Mogholistan and endured there until the mid-fifteenth century under Esen Buqa II b. Uways Khān (r. 833–67/1429–62), a dangerous enemy of the later Tīmūrids; but the Chaghatayids’ Transoxanian territories fell to the Shïbānids (see below, no. 153) by the beginning of the sixteenth century. Only the eastern branch persisted in Semirechye, with its capital at first at Almalïgh in the upper Ili region, and in the Tarim basin, where it expanded towards Turfan and shared power in Kāshghar with the Dughlat tribe of Turks until the final extinction of the Chaghatayids in 1089/1678 and their replacement in Eastern Turkestan by a line of local Naqshbandī religious leaders, the Khōjas.

Lane-Poole, 241–2; Sachau, 30 no. 77; Zambaur, 248–50; Album, 43–4.

EI2 ‘Čaghatay Khān’, ‘Čaghatay Khānate’ (W. Barthold and J. A. Boyle); Eir ‘Chaghatayid dynasty’ (P. Jackson).

L. Hambis, Le chapitre CVII du Yuan Che, 56–64.

J. A. Boyle, The Successors of Genghis Khan, with a genealogical table at p. 345.

133

THE IL KHĀNIDS, DESCENDANTS OF QUBILAY’S BROTHER HŪLEGŪ

654–754/1256–1353

Persia, Iraq, eastern and central Anatolia

⊘ 654/1256 |

Hülegü (Hūlākū), son of Toluy |

⊘ 663/1265 |

Abaqa, son of Hülegü, d. 680/1282 |

⊘ 681/1282 |

Ahmad Tegüder (Takūdār), son of Hülegü |

⊘ 683/1284 |

Arghun, son of Abaqa |

⊘ 690/1291 |

Gaykhatu, son of Abaqa |

⊘ 694/1295 |

Baydu, son of Taraqay, son of Hülegü |

⊘ 694/1295 |

Maḥmūd Ghazan (Ghāzān) I, son of Arghun |

⊘ 703/1304 |

Muḥammad Khudābanda Öljeytü (Ūljāytū), Ghiyāth al-Dīn, son of Arghun |

⊘ 716/1316 |

Abū Sa‘id, ‘Alā’ al-Dunyā wa ’l-Dīn, Bahādur, son of Öljeytü |

⊘ 736/1335 |

Arpa Ke’ün (Gawon), descendant of Arïgh Böke, son of Toluy |

⊘ 736/1336 |

Mūsā, son of ‘Alī, son of Baydu |

⊘ 737–8/1337–8 |

Muḥammad, descendant of Hülegü’s son Möngke Temür |

⊘(739–54/1338–53 |

Togha(y) Temür, descendant of one of Chingiz Khān’s brothers, either Ötken or Jochi, in control of western Khurasan and Gurgān |

754–90/1353–88 |

Luqmān b. Togha(y) Temür, sporadic claimant in Khurasan) |

738–54/1338–53 |

Period of several rival khāns in various parts of Persia nominated by the Jalāyirid Amīr Hasan Buzurg (⊘ Toghay Temür, see above; ⊘ Jahān Temur) and the Chobanid Amīr Hasan Küchük (⊘ Sati Beg Khātūn; ⊘ Sulaymān; ⊘ Anūshirwān; ⊘ Ghazan II); thereafter, Persia divided among local dynasties such as the Jalāyirids, the Muzaffarids and the Sarbadārids |

The Great Khān Möngke entrusted his brother Hülegü with the task of recovering and consolidating the Mongol conquests in Western Asia, for in the interval since Ögedey’s death direct control of much of the Islamic world south of the Oxus had slipped out of Mongol hands. Hülegü accordingly came westwards. He overcame the resistance of the Ismā‘īlīs or Assassins of northern Persia (see above, no. 101) (654/1256); routed a caliphal army in Iraq and murdered the last ‘Abbāsid caliph al-Musta‘ṣim (656/1258); and advanced into Syria where, however, the Mongols were defeated and halted at ‘Ayn Jālūt in Palestine by the Mamlūks of Egypt and Syria (see above, no. 31) (658/1260). Even so, Hülegü now became ruler on behalf of the Great Khān of all the regions of Persia, Iraq, Transcaucasia and Anatolia, and assumed the title of I1 Khān, namely territorial khān, implying subordination to the Great Khān.

The Il Khānid kingdom was now definitely constituted, but it had many external enemies, including the Mamlūks, who had destroyed the popular belief in Mongol invincibility and were now the standard-bearers of Islam against the scourge of the pagans. The other Mongol houses of the Chaghatayids (see above, no. 132) and the Golden Horde (see below, no. 134) were also hostile over disputed territories in the Caucasus region and on the north-eastern Persian fringes respectively. It was common hostility towards the II Khānids that brought about a political and commercial alliance of the Mamlüks and the Golden Horde, whereas the II Khānids for their part sought to conclude an anti-Muslim coalition with the European Christian powers, with the surviving Crusaders in the Levant coastal towns and with the Little Armenian kingdom in Cilicia. Hülegü’s wife Doquz Khātün was a Nestorian Christian, and the first II Khānids were favourably inclined towards Christianity and Buddhism.

The II Khānids managed to hold their own against external foes, but, after the Great Khan Qubilay’s death in 693/1294, links with the senior members of the Mongol family in Mongolia and China became very loose, especially as the cultural and religious pressures of the Persian environment brought about the conversion to Islam of Ghazan (his short-reigned predecessor Ahmad Tegüder had also been converted) and his successors. Abū Sa‘īd was the last great I1 Khānid. He made peace with the Mamlūks in 723/1323 and thus ended the fighting over possession of Syria, but relations with the Golden Horde and disputes over the Caucasus region continued throughout his reign. It was unfortunate that he died without an heir and, indeed, without any close relations to succeed him. The two decades after his death were filled with a succession of ephemeral khans, raised to the throne by the rival Jalāyirid and Chobanid Amīrs, until finally the Il Khānid empire fell apart and was replaced by local dynasties across Persia. It was left to Tīmūr Lang a generation later to reunite the Persian lands under one sovereign.

Despite much warfare and internal disturbance, the I1 Khānid period was a prosperous one for Persia. After Ghazan became a Muslim, there began tentatively a reconciliatory process between the Mongol-Turkish military and ruling class and their Persian subjects. The I1 Khānid capitals of Tabrīz and Marāgha in Azerbaijan became centres of learning, with the natural sciences, astronomy and historical writing especially flourishing. After 707/1307, Öljeytü planned a new capital at Sulṭāniyya near Qazwīn; artists, architects and craftsmen were encouraged, and distinctive styles of, for example, I1 Khānid architecture and painting emerged. The internationalist attitudes of the Mongols and their connections with such ancient cultures as the Chinese brought fresh intellectual, commercial and artistic influences into the Persian world. Colonies of Italian traders now appeared in the capital Tabrīz, and the I1 Khānid empire played a significant connecting role in trade with the Far East and India.

Lane-Poole, 217–21; Zambaur, 244–5; Album, 45–8.

EI2 ‘Īlkhāns’ (B. Spuler).

L. Hambis, Le chapitre CVII du Yuan Che, 90–4.

J. A. Boyle, The Successors of Genghis Khan, with a genealogical table at p. 343.

B. Spuler, Die Mongolen in Iran. Politik, Verwaltung und Kultur der Ilchanzeit 12201350, 4th edn, Leiden 1985, with a genealogical table at p. 382.

D. O. Morgan, The Mongols, with a genealogical table at p. 225.

134

THE KHĀNS OF THE GOLDEN HORDE, DESCENDANTS OF JOCHI

624–907/1227–1502

Western Siberia, Khwārazm and South Russia

1. The line of Batu’ids, Khāns of the Blue Horde in South Russia, Khwārazm and the western part of the Qïpchaq steppe

624/1227 |

Batu, son of Jochi, d. ?653/?1255 |

654/1256 |

Sartaq, son of Batu |

655/1257 |

Ulaghchi, son or brother of Sartaq |

655/1257 |

Berke (Baraka), son of Jochi |

⊘ 665/1267 |

Möngke (Mengü) Temür, son of Toqoqan, son of Batu |

⊘ 679/1280 |

Töde Möngke (Mengü), son of Toqoqan |

⊘ 687/1287 |

Töle Buqa, son of Tartu, son of Toqoqan |

⊘ 690/1291 |

Toqta, son of Möngke Temür, Ghiyāth al-Dīn |

⊘ 713/1313 |

Muḥhammad Özbeg, son of Toghrïlcha, son of Möngke Temür, Ghiyāth al-Dīn |

742/1341 |

Tīnī Beg, son of Özbeg |

⊘ 743/1342 |

Jānī Beg (Jambek), son of Özbeg |

758–82/1357–80 |

Period of anarchy, with several rival claimants, including ⊘ Muhammad Berdi Beg, ⊘ Qulpa, ⊘ Muhammad Nawrüz Beg, ⊘ Khidr, ⊘ Murad, ⊘ Muhammad Bolaq, etc. |

2. The line of Orda, Khāns of the White Horde in western Siberia and the eastern part of the Qïpchaq steppe, and, after 780/1378, of the Blue and White Hordes united into the Golden Horde of South Russia

Chingiz’s eldest son Jochi had been allotted as his appanage western Siberia and the Qïpchaq Steppe, and on his death in 624/1227 the eastern part of all this, namely western Siberia, fell to his eldest son Orda, who became titular head of the descendants of Jochi and who founded in his territories the White Horde. Little is known about the early White Horde khāns, but the forceful and energetic Toqtamïsh (d. 809/1406) is a figure of major importance in steppe and eastern European history. He united the Batu’id Blue Horde (by now known as the Golden Horde) with the White Horde, and once more made the Golden Horde a power of importance in Russia, sacking Nizhniy Novgorod and Moscow in 784/1382. However, he had the misfortune to come up against Tīmūr Lang, who drove him out of his capital Saray on the Volga, so that Toqtamïsh was forced to flee into exile with Vitold (Vitautas), Grand Duke of Lithuania.

The western half of Jochi’s appanage, Khwārazm and the Qïpchaq Steppe of South Russia, went to his second son Batu. Batu ravaged Russia almost as far as Novgorod, captured Kiev and attacked Poland and Hungary. Christian Europe was only saved from further molestation after Batu’s Liegnitz victory of 638/1241 and the pursuit of the Hungarian King Béla IV to the shores of the Adriatic by the news of the Great Khan Ögedey’s death. Based on the capital Saray, Batu’s Blue Horde became the nucleus of the Golden Horde (a name apparently given to them by the Russians, Zolotaya Orda, although Russian and Polish-Lithuanian sources most usually refer to it simply as ‘the Great Horde’). From Özbeg onwards (d. 742/1341), the khāns of the Golden Horde were all Muslims, and this meant that there was a religious gulf fixed between the ruling Golden Horde and the mass of their Orthodox Christian Russian subjects, although Latin Christian missionaries continued to work for some time in the Qïpchaq Steppe. The Horde had important commercial links with Anatolia and the Mamlūk empire in Syria and Egypt; slave replenishments were sent to the Mamlūks, while the culture of the Horde received a definite Islamic-Mediterranean impress, in contrast to the Persianised Il Khānids. However, the growth of Ottoman Turkish power and the Ottoman control of the Dardanelles after 755/1354 cut the Horde off from the Mediterranean and contact with the Mamlūks and made them purely a power within Russia.

After Toqtamïsh’s death, real power in the Golden Horde was held by the capable ‘Mayor of the Palace’ Edigü, but after the latter’s death in 822/1419 a process of disintegration, involving much internal discord, set in. Already in the later fourteenth century, the rise of Poland-Lithuania and the Princedom of Muscovy had seriously checked the authority of the khāns, and the Ottomans and their allies the Crimean Tatars were also hostile. It was, indeed, the Crimean khān, Mengli Giray, who in 907/1502 defeated the leader of the Horde and incorporated the major part of its manpower into his own forces. But before that date, other khanates had split off from the Golden Horde, under various descendants of a third son of Jochi, Toqa Temür; these included the khanates of Astrakhan (until the Russian conquest of 961/1554: see below, no. 136), of Kazan (until the Russian conquest of 959/1552: see below, no. 137); of Qāsimov (around Ryazan, untile. 1092/c. 1681: see below, no. 138); and of the Crimea (see below, no. 135).

Lane-Poole, 222–31 and table at p. 240; Zambaur, 244, 246–7 and Table S; Album, 44.

L. Hambis, Le chapitre CVII du Yuan Che, 52–7.

B. Spuler, Die Goldene Horde. DieMongolenin Russland 1223–1502, 2nd edn, Wiesbaden 1965, with genealogical tables and lists at pp. 453–4.

J. A. Boyle, The Successors of Genghis Khan, with a genealogical table at p. 344.

D. O. Morgan, The Mongols, with a genealogical table at p. 224.

135

THE GIRAY KHĀNS OF THE CRIMEA, DESCENDANTS OF JOCHI

853–1208/1449–1792

The Crimea and the southern Ukraine

2. The Khāns of the Tatars of Bujaq or Bessarabia, as Ottoman nominees

1201/1787 |

Shāhbāz Giray b. Arslan |

1203–6/1789–92 |

Bakht Giray |

Among the descendants of Jochi’s son Toqa Temür, one branch established itself in the Crimea during the course of the internecine strife which convulsed the Golden Horde after 760/1359. At first they were vassals of Toqtamïsh, but then in the early fifteenth century they gradually became independent under the progeny of Tash Temür, with Ḥājjī Giray formally declaring himself ruler of Qïrïm in 853/1449. The family name Giray derives possibly from that of the Kerey, a component clan of the Golden Horde which had supported Ḥājjī Giray. The Crimean khanate now became one of the most enduring states to arise under the descendants of Chingiz Khān, and by the end of the fifteenth century it also controlled the lands of the Noghays on the northern Black Sea coast as far west as Bujaq or Bessarabia.

The Ottomans were the natural allies of the Girays, at first against the Golden Horde, whose khans continued to regard the Crimea as one of their own dependencies, and then, from the sixteenth century onwards, against the Russians. The Girays claimed to be heirs of the Golden Horde after they had defeated its leader and incorporated the greater part of its fighting manpower into their own forces (see above, no. 134), and did for part of the sixteenth century rule at Kazan (see below, no. 137). Their increased military strength after 907/1502, and the fact that the pasture grounds of the Girays were nearer to Moscow than the Golden Horde’s more usual centre on the lower Volga, now meant increased military pressure on Muscovy, with attacks and raids continuing until the eighteenth century. From the later sixteenth century, the khans ruled from their capital at Baghche Saray (Simferopol) over much of the southern part of the Ukraine and the lower Don-Kuban region, acting as a buffer-state between the Ottomans and the Christian powers of Eastern Europe; in fact, during the early seventeenth century they were at times allied with Poland-Lithuania against the Russian Tsars. The Ottomans regarded the Crimean Tatars as their dependents, requiring the presence of a hostage Giray prince at their court, although rarely intermarrying with the Girays; there was a vague feeling that, should the Ottoman dynasty die out (as seemed not impossible at one point in the seventeenth century), the Girays would have a claim on the succession in Turkey.

Russian expansionism southwards brought about Peter the Great’s capture of Azov in 1699, which cut the lands of the Crimean Tatars in two. In the eighteenth century, Russian pressure increased, with the enfeebled Ottoman empire unable to help, and by 1197/1783 Catherine the Great’s troops had occupied and annexed the Crimea. Two of the Girays were, however, appointed by the Porte to head the Tatars in Bessarabia for a few years.

Lane-Poole, 235–7 and table at p. 240; Zambaur, 247–8 and Table S; Album, 44–5.

İA ‘Giray’ (Halil İnalcik), with a genealogical table; EI‘Giray’ (idem), ‘Ḳirim’ (B. Spuler), with a list of rulers.

Alan W. Fisher, The Crimean Tatars, Stanford CA 1978, 1–69.

136

THE KHĀNS OF ASTRAKHAN (ASTRAKHĀN, ASHTARKHĀN)

871–964/1466–1557

The lower Volga and the adjacent steppelands

871/1466 |

Qāsim b. Maḥmūd b. Küchük Muḥammad |

895/1490 |

‘Abd al-Karīm b. Maḥmūd b. Küchük Muḥammad |

909/1504 |

Qāsim or Qasay b. Sayyid Ahmad |

938/1532 |

Aq Köbek b. Murtaḍā, first reign |

941/1534 |

‘Abd al-Raḥmān b.‘Abd al-Karīm |

945/1538 |

Shaykh Ḥaydar b. Shaykh Aḥmad |

948/1541 |

Aq Köbek, second reign |

951/1544 |

Yaghmurchi b. Birdi Beg |

961/1554 |

Russian conquest |

961–4/1554–7 |

Darwīsh ‘Alī b. Shaykh Ḥaydar, as a Russian nominee |

964/1557 |

Incorporation of the khanate into Russia |

During the decline of the Golden Horde (see above, no. 134), there arose at Astrakhan near the mouth of the Volga (a town long important from its position on the trade route down the Volga to the Caspian Sea and beyond) a line of Noghay Tatar khāns stemming from Or da’s White Horde through Toqtamïsh. The lands of the first khāns extended as far as the Kazan khanate (see below, no. 137) in the north, to Orenburg or Chkalov in the east and the lands of the Crimean Tatar khāns in the west. By the 1530s, ‘Abd al-Rahmān Khān was being pressed by the khāns of Crimea and the Noghays, and appealed for help to the Russian Tsar; but in 961/1554 Ivan IV (‘The Terrible’) conquered Astrakhan, and three years later deposed the puppet Darwīsh ‘Alī Khān when he began seeking support from his Tatar Muslim neighbours, and Astrakhan was incorporated into the Russian empire.

Lane-Poole, 229 and table at p. 240; Zambaur, 247 (fragmentary) and Table S.

İA ‘Astırhan, Astraḫan’ (R. Rahmeti Arat); EI1 Astrakhān’ (B. Spuler).

840–959/1437–1552

The middle Volga region

840/1437 |

Ulugh Muhammad b. Jalāl al-Dīn b. Toqtamïsh |

849/1445 |

Maḥmūd (Mahmūdak) b. Ulugh Muḥammad |

866/1462 |

Khalīl b. Mahmūd |

871/1467 |

Ibrāhīm b. Maḥmūd |

884/1479 |

‘Alī b. Ibrāhīm, first reign |

889/1484 |

Muḥammad Amīn b. Ibrāhīm, first reign |

890/1485 |

‘Alī b. Ibrāhīm, second reign |

892/1487 |

Muḥammad Amīn b. Ibrāhīm, second reign |

(900/1495 |

Mamūq b. Ibaq, Khān of the Tatars of Siberia) |

901/1496 |

‘Abd al-Laṭīf b. Ibrāhīm |

907–24/1502–18 |

Muḥammad Amīn b. Ibrāhīm, third reign |

2. Khāns from various outside lines

925/1519 |

Shāh ‘Alī b. Sayyid Awliyār, from the Khāns of Qāsimov, first reign |

927/1521 |

Ṣāḥib Giray (I) b. Mengli I, from the Khāns of Crimea |

930/1524 |

Ṣafā’ Giray b. Fatḥ, from the Khāns of Crimea, first reign |

937/1531 |

Jān ‘Alī b. Sayyid Awliyār, from the Khāns of Qāsimov |

939/1533 |

Ṣafā’ Giray b. Fatḥ, second reign |

953/1546 |

Shāh ‘Alī b. Sayyid Awliyār, second reign |

953/1546 |

Ṣafā’ Giray b. Fatḥ, third reign |

956/1549 |

Ötemish b. Ṣafā’ Giray, from the Khāns of Crimea, regent for Süyün Bike |

958/1551 |

Shāh ‘Alī b. Sayyid Awliyār, third reign |

959/1552 |

Yādigār Muḥammad b. Qāsim, from the Khāns of Astrakhan |

959/1552 |

Russian conquest |

The Kazan khanate was another of the groupings founded by a Jochid epigone. Toqtamïsh’s grandson Ulugh Muhammad rose to power in what later became eastern Russia as the Golden Horde decayed, and his son Maḥmūd in 849/1445 seized the actual town of Kazan from a local prince, possibly of Bulghār descent, ‘Alī Beg. It was likewise around this time that the sister khanate of Qāsimov (see below, no. 138) emerged. The khanate spanned the middle Volga basin around the confluence of the Volga and Kama rivers and in the south bordered on the khanate of Astrakhan (see above, no. 136). It thus covered a region which had been exposed to Islamic influences since the constituting of the Bulghār kingdom towards the opening of the tenth century. Kazan’s position gave it a considerable commercial importance, not least as a mart for slaves.

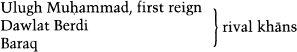

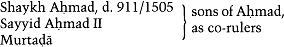

All through the khanate’s life, its history was bound up with that of the Princedom of Muscovy, its western neighbour, now reasserting itself after some two centuries of thraldom to the Golden Horde and its successors. From the outset, the Princes interfered in succession disputes within Kazan. This intervention intensified after the end of the family of Ulugh Muhammad, and the last three decades or so of the khanate saw rulers installed at Kazan from various outside Chingizid lines, with internal tensions between the partisans of an accommodation with Muscovy and those hoping to preserve Kazan’s independence through links with the Crimean Tatars and the Noghay Horde. Finally, the army of Tsar Ivan IV captured Kazan in 959/1552, and a systematic Russian occupation and colonisation of the lands of the former khanate began. A considerable proportion of the Muslim Tatar population has nevertheless survived over the centuries, and a reduced part of the khanate formed under the Soviets the Tatar Autonomous SSR.

Lane-Poole, genealogical table at p. 240; Zambaur, 249 and Table S.

İA ‘Kazan’ (Reşid Rahmati Arat), with a genealogical table; EI2 ‘Ḳāzān’ (W. Barthold and A. Bennigsen).

Azade-Ayşe Rorlich, The Volga Tatars. A Profile in National Resilience, Stanford CA 1986, 3–33.

c. 856–1092/c. 1452–1681

The region of Ryazan, to the south-east of Moscow

1. The Khāns from the line of rulers of Kazan

c. 856/c.l452 |

Qāsirn b. Ulugh Muḥammad |

873–91/1469–86 |

Dāniyār b. Qāsirn |

2. The Khāns from the line of the rulers of the Crimea

891/1486 |

Nūr Dawlat Giray b. Ḥājjī I |

c. 905/c. 1500 |

Satïlghan b. Nūr Dawlat |

912/1506 |

Jānay b. Nür Dawlat |

3. The Khāns from the line of the rulers of Astrakhan

918/1512 |

Sayyid Awliyār b. Bakhtiyār Sulṭān b. Küchük Muhammad |

922/1516 |

Shāh ‘Alī b. Sayyid Awliyār, first reign |

925–38/1519–32 |

Jān ‘Alī b. Sayyid Awliyār |

944–58/1537–51 |

Shāh ‘Alī b. Sayyid Awliyār, second reign |

959/1552 |

Shāh ‘Alī, third reign |

974/1567 |

Sayïn Bulāt b. Bik Bulāt (Simeon Bekbulatovich), d. 1025/1616 |

981–1008/1573–1600 |

Muṣṭafa ‘Alī b. Aq Köbek |

1008–19/1600–10 |

Uraz Muḥammad |

(1019–23/1610–14 |

the throne vacant in Qāsimov) |

5. The Khāns from the line of the rulers of Siberia

1023/1614 |

Arslan or Alp Arslan b. ‘Alī b. Kuchum |

1036/1627 |

Sayyid Burhān b. Arslan (Vassili) |

1090–2/1679–81 |

Fāṭima Sulṭān Bike, widow of Arslan |

1092/1681 |

Annexation to Russia |

The khanate of Qāsimov was another of the distant successors to the ulus of Jochi and Batu. It was founded by a member of the ruling family in Kazan, Qāsirn, who had fled to Moscow for protection. The Grand Prince Vassili I granted to him the town of Gorodets or Gorodok Meshchevskiy, later named after its ruler Qāsimov, on the Oka river to the south-east of Moscow. This became the centre of a principality which has been described as ‘a historical curiosity’ but which survived for over two centuries as a petty state, with ill-defined frontiers. The khāns bore in Russian the titles of Tsar and Tsarevitch, and were, in effect, feudal vassals of the Grand Princes and Emperors. Qāsimov was often a refuge for dissident Chingizids and was ruled at different times by members of the various Jochid lines. Latterly, some of the ruling family in Qāsimov became Christian and entered Russian service, and the khanate was eventually annexed to the Russian crown.

Lane-Poole, 234–5 and genealogical table at p. 240; Zambaur, 249 and Table S.

İA ‘Kasim hanhği’ (Reşid Rahmeti Arat); EI2‘Kasimov’ (A. Bennigsen).