ELEVEN

The Seljuqs, their Dependants

and the Atabegs

431–590/1040–1194

Persia, Iraq and Syria

1. The Great Seljuqs in Persia and Iraq 431–590/1040–1194

2. The Seljuqs of Syria 471–511/1078–1117

| ⊘ 471/1078 | Tutush I b. Alp Arslan, Abū Sa‘īd Tāj al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 488–507/ 1095–1113 |

Riḍwān b. Tutush, Fakhr al-Mulk, in Aleppo, d. 507/1113 |

| 488–97/1095–1104 | Duqaq b. Tutush I, Abū Naṣr Shams al-Mulūk, in Damascus, d. 497/1104 |

| 497/1104 | Tutush II b. Duqaq, in Damascus, died shortly after his accession |

| |

|

| 517/1123 | Succession of the Bönd Atabeg Ṭughtigin in Damascus; succession of the Artuqid Nūr al-Dawla Balak and then Aq Sunqur al-Bursuqī in Aleppo |

3. The Seljuqs of Kirman 440–c. 584/1048–c. 1188

| ⊘ 440/1048 | Aḥmad Qāwurd b. Chaghrï Beg Dāwūd, Qara Arslan Beg, ‘Imād al-Dīn wa ’l-Dawla |

| ⊘ 465/1073 | Kirmān Shāh b. Qāwurd |

| ⊘ 467/1074 | Ḥusayn b. Qāwurd |

| ⊘ 467/1074 | Sulṭān Shāh Isḥāq b. Qāwurd, Rukn al-Dīn wa ’l-Dawla |

| ⊘ 477/1085 | Tūrān Shāh I b. Qāwurd, Muḥyī ’1-Dīn ‘Imād al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 490/1097 | Īrān Shāh b. Tūrān Shāh I, Bahā’ al-Dīn wa ’l-Dawla |

| ⊘ 494 or 495/1101 | Arslan Shāh I b. Kirmān Shāh, Muḥyī ’1-Islām wa ’1-Muslimīn, d. ? 540/1145 |

| ⊘ 537/1142 | Muḥammad I b. Arslan Shāh I, Mughīth al-Dunyā wa ’1-Dīn |

| ⊘ 551/1156 | Ṭoghrïl Shāh b. Muḥammad I, Muḥyī ’1-Dunyā wa ’1-Dīn |

| ⊘ 565/1170 | Bahrām Shāh b. Ṭoghrïl Shāh, Abū Manṣūr, first reign |

| ⊘ 565/1170 | Arslan Shāh II b. Ṭoghrïl Shāh, first reign |

| c. 566/c. 1171 | Bahrām Shāh b. Ṭoghrïl Shāh, second reign |

| c. 568/c. 1172 | Arslan Shāh II, second reign |

| c. 571/c. 1175 | Bahrām Shāh b. Ṭoghrïl Shāh, third reign |

| c. 571/c. 1175 | Muḥammad Shāh b. Bahrām Shāh, first reign |

| c. 571/c. 1175 | Arslan Shāh II, third reign, d. 572/1177 |

| ⊘ 572/1177 | Tūrān Shāh II b. Ṭoghrïl Shāh, d. 579/1183 |

| c. 579/c. 1183 | Muḥammad Shāh, second reign |

| c. 584/c. 1188 | Ghuzz occupation |

The Seljuqs were originally a family of chiefs of the Qïnïq clan of the Oghuz or Ghuzz Turkish people, whose home was in the steppes north of the Caspian and Arab Seas. Becoming Muslims towards the end of the tenth century, they entered the Islamic world in Khwārazm and Transoxania in the same fashion as so many barbarian peoples all over the Old World, namely as auxiliary troops in the service of warring powers, in this case, as participants in the struggles of the last Sāmānids, the Qarakhānids and the Ghaznawids. Deflected into Khurasan, the Seljuqs, their bands of nomadic followers and their herds, gradually took over that province from the Ghaznawids, seizing the capital Nishapur temporarily in 429/1038, where their leader Ṭoghrïl Beg proclaimed himself sultan. Leaving his brother Chaghrï Beg as ruler of Khurasan, Ṭoghrïl began deliberately to associate his authority with the cause of Sunnī orthodoxy and the freeing of the ‘Abbāsid caliphs from the Shī‘ī Būyids’ tutelage, a policy which enabled him to enlist orthodox sympathy as the Seljuqs advanced through Persia and swept aside the local Daylamī and Kurdish princes. In 447/1055, Ṭoghrïl entered Baghdad and had his title of sultan confirmed by the caliph; a few years later, the line of Būyids was finally extinguished in Fars (see above, no. 75).

The sultanate of the Great Seljuqs now evolved towards a hierarchically-organised state on the Perso-Islamic monarchic pattern, with the supreme sultan supported by a Persian and Arab bureaucracy and a multi-national army directed by Turkish slave commanders, this nucleus of professional soldiers being supplemented by the tribal contingents of the Türkmen begs or chiefs; but the continued importance within the sultanate of the Turkish elements was to mean that the Seljuq sultanate never developed into such a despotic, monolithic state as that of the Ghaznawids, much more completely cut off from the rulers’ original steppe background. During the reign of Alp Arslan and his son Malik Shāh, who both depended to a great extent on their supremely able Persian minister, Niẓām al-Mulk, the empire of the great Seljuqs reached its apogee. In the east, Khwārazm and what is now western Afghanistan had been wrested from the Ghaznawids, and towards the end of his reign Malik Shāh invaded Transoxania and humbled the Qarakhānids, receiving at Uzgend the homage of the Khān of the eastern branch in Kāshghar and Khotan. In the west, the offensive was taken against the Christian Armenian princes and Georgian kings in Transcaucasia. Fāṭimid influence was excluded from Syria and Jazīra, while minor, Shī‘ī-tinged dynasties like the ‘Uqaylids of northern Iraq and Jazīra (see above, no. 38) were overthrown and reliable Turkish governors installed in Syria. Alp Arslan’s victory over the Byzantine emperor Romanus Diogenes at Mantzikert (Malāzgird) in 463/1071 further opened up Anatolia to Turkmen incursions, and these intensified raids laid the foundations for various Turkish principalities in Asia Minor, including that of a branch of the Seljuqs in Konya (Qūnya) (see further below, Chapter Twelve). Malik Shāh’s brother Tutush and the latter’s sons and grandsons founded a short-lived, minor Seljuq line in Aleppo and Damascus. Seljuq arms even penetrated into the Arabian peninsula as far as Yemen and Baḥrayn. In Kirman in south-eastern Persia, Chaghrï Beg’s son Qāwurd established a local Seljuq dynasty which endured for nearly a century and a half until Oghuz tribesmen from Khurasan took over the province in c. 584/c. 1188. On the cultural and intellectual plane, notable was an acceleration in the programme of the foundation of orthodox Sunnī madrasas or colleges in Iraq and the Persian lands, and the encouragement of the sultans and their servants of a synthesis of traditional theological and legal studies with the more free-ranging spirit of Ṣūfism, exemplified in the life and work of scholars like ‘Abd al-Karīm al-Qushayrī (d. 465/1072) and Muḥammad al-Ghazālī (d. 505/1111).

Centrifugal tendencies were always likely to appear within an empire like that of the Great Seljuqs, in which old Turkish patrimonial ideas about rulership and the division of territories among various members of the ruling family were still strong, once firm control from the centre was relaxed. After Malik Shāh’s death, the Seljuq lands of Iraq and western Persia were racked by dissension and civil strife, although an element of continuity and stability continued in Khurasan, where Malik Shāh’s son Sanjar was first governor and then, after the death in 511/1118 of his brother the supreme sultan Muḥammad, was acknowledged as senior member of the dynasty and supreme sultan. In Iraq, Seljuq authority was adversely affected by the reviving political and military power there of the ‘Abbāsid caliphs, and after 547/1152 this authority was permanently excluded from Baghdad. In the Persian lands, Transcaucasia, Jazīra and Syria, the rise of local lines of Atabegs reduced the sultans’ freedom of action and their revenues which they needed for paying their troops. The Atabegs were slave commanders of the Seljuq army, who were in the first place appointed as tutor-guardians (Turkish Atabeg ‘father-commander’) to young Seljuq princes sent out as provincial governors; but in many instances they soon managed to arrogate effective power to themselves and to found hereditary lines in the provinces (see, for example, below: the Börids, Zangids, Eldigüzids, Salghurids, etc., nos 92ff.).

The entry of the Seljuqs and their nomadic followers began a long process of profound social, economic and ethnic changes to the ‘northern tier’ of the Middle East, namely the zone of lands extending from Afghanistan in the east through Persia and Kurdistan to Anatolia in the west; these changes included a certain increase in pastoralisation and a definitely increased degree of Turkicisation. Within the Seljuq lands there remained significant numbers of Turkish nomads, largely unassimilated to settled life and resentful of central control and, especially, of taxation. The problem of integrating such elements into the fabric of state was never solved by the Seljuq sultans; when Sanjar’s reign ended disastrously in an uprising of Oghuz tribesmen whose interests had, they, felt, been neglected by the central administration, the Oghuz captured the Sultan, and, on his death soon afterwards, Khurasan slipped definitively from Seljuq control. The last Seljuq sultan in the west, Ṭoghrïl III, struggled to free himself from control by the Eldigüzid Atabegs, but unwisely provoked a war with the powerful and ambitious Khwārazm Shāh Tekish (see above, no. 89, 3) and was killed in 590/1194. Only in central Anatolia did a Seljuq line, that of the sultans of Rūm with their capital at Konya, survive for a further century or so (see below, no. 107).

Justi, 452–3; Lane-Poole, 149–54; Zambaur, 221–2 and Table R; Album, 22, 37–8.

EI2 ‘Kirmān. History’ (A. K. S. Lambton), ‘Saldjūḳids. I–IV. 1’ (C. E. Bosworth), ‘VIII. 1. Numismatics’ (R. Darley-Doran).

Cl. Cahen, ‘The Turkish invasion: the Selchükids’, in K. M. Setton and M. W. Baldwin (eds), A History of the Crusades. I. The First Hundred Years, Philadelphia 1955, 135–76.

C. E. Bosworth, in The Cambridge History of Iran, V, 11–184.

Ç. Alptekin, ‘Selçuklu paralari’, SAD, 3 (1971), 435–591.

Gary Leiser (ed. and tr.), A History of the Seljuks. İbrahim Kafesoğlu’s Interpretation and the Resulting Controversy, Carbondale and Edwardsville IL 1988.

497–549/1104–54

Damascus and southern Syria

| ⊘ 497/1104 | Ṭughtigīn, Abū Manṣūr Ẓahīr al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 522/1128 | Böri b. Ṭughtigin, Abū Sa‘īd Tāj al-Mulūk |

| 526/1132 | Ismā‘īl b. Böri, Shams al-Mulūk |

| ⊘ 529/1135 | Maḥmūd b. Böri, Abu ’1-Qāsim Shihāb al-Dīn |

| 533/1139 | Muḥammad b. Böri, Abū Manṣūr Jamāl al-Dīn, Shams al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 534–49/1140–54 | Abaq b. Muḥammad, Abū Sa‘īd Mujīr al-Dīn, d. 564/1169 |

| 549/1154 | Succession in Damascus of the Zangid Nūr al-Dīn |

This Atabeg dynasty derived from Ṭughtigin, Atabeg to the Seljuq Amīr of Damascus Duqaq b. Tutush I (see above, no. 91, 2), who after the early death of the child Tutush II b. Duqaq became himself sole ruler in Damascus, founding a line which endured there for half a century. Ṭughtigin and his son Böri managed to maintain their power through skilful diplomacy with the Fāṭimids and timely agreements with the Frankish Crusaders, but these balancing policies were regarded with disfavour by the ‘Abbāsid caliphs and the Great Seljuq sultans in Iraq. Hence the later Börids came under increased pressure from the bellicosely Sunnī orthodox Zangids of Mosul and Aleppo (see below, no. 93), who attacked Damascus in 529/1135, and in 549/1154 the last Börid Abaq had to abandon his capital to Nūr al-Dīn Maḥmūd b. Zangī.

Lane-Poole, 161; Zambaur, 225; Album, 22.

EI2 ‘Būrids’ (R. Le Tourneau); ‘Dimashḳ’ (N. Elisséeff).

M. Canard, ‘Fāṭimides et Būrides à l’époque du calife al-Ḥāfiẓ li-dīn-illāh’, REI, 35 (1967), 103–17.

521–649/1127–1251

Jazīra and Syria

1. The main line in Mosul and Aleppo

| ⊘ 521/1127 | Zangī I b. Qasīm al-Dawla Aq Sunqur, Imād al-Dīn |

| 541/1146 | Ghāzī I b. Zangī I, Sayf al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 544/1149 | Mawdūd b. Zangī I, Quṭb al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 565/1170 | Ghāzī II b. Mawdūd, Sayf al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 576/1180 | Mas‘ūd I b. Mawdūd, ‘Izz al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 589/1193 | Arslan Shāh I b. Mas‘ūd, Abu ’1-Ḥārith Nūr al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 607/1211 | Mas‘ūd II b. Arslan Shāh, al-Malik al-Qāhir ‘Izz al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 615/1218 | Arslan Shāh II b. Mas‘ūd II, Nūr al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 616/1219 | Maḥmūd b. Mas‘ūd II, al-Malik al-Qāhir Nāṣir al-Dīn |

| 631/1234 | Rule in Mosul by the vizier Badr al-Dīn Lu’lu’ |

2. The line in Damascus and then Aleppo

| ⊘ 541/1147 | Maḥmūd b. Zangī, Abu ’1-Qāsim al-Malik al-‘Ādil Nūr al-Dīn, in Aleppo and then Damascus |

| ⊘ 569–77/1174–81 | Ismā‘īl b. Maḥmūd, al-Malik al-Ṣāliḥ Nūr al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 577/1181 | Zangi II b. Mawdūd, Abu ’1-Fatḥ al-Malik al-‘Ādil ‘Imād al-Dīn, of Sinjār |

| 579/1183 | Conquest by the Ayyūbid Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn Yūsuf (Saladin) |

| ⊘ 566/1171 | Zangī II b. Mawdūd, 577–9/1181–3 lord of Aleppo also |

| ⊘ 594/1197 | Muḥammad b. Zangī II, Quṭb al-Dīn |

| 616/1219 | Shāhānshāh b. Muḥammad, ‘Imād al-Dīn |

| |

|

| 617/1220 | Ayyūbid domination |

| ⊘ 576/1180 | Sanjar Shāh b. Ghāzī II b. Mawdūd, Mu‘izz al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 605/1208 | Maḥmūd b. Sanjar Shāh, al-Malik al-Mu‘aẓẓam Mu‘izz al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 639–48/1241–50 | Mas‘ūd b. Maḥmūd, al-Malik al-Ẓāhir |

| 648/1250 | Ayyūbid domination |

| ?–630/?–1233 | Zangī III b. Arslan Shāh II, ‘Imād al-Dīn |

| 630–49/1233–51 | Il Arslan b. Zangī III, Nūr al-Dīn |

Zangī was the son of Aq Sunqur, who was a Turkish slave commander of the Great Seljuq Sultan Malik Shāh and governor of Aleppo from 479/1086 to 487/1094 (the origin of the name Zangī is unclear; an obvious meaning would be ‘black African’, possibly relating to a swarthy complexion, but this would be unusual for a Turk). In 521/1127, Sultan Maḥmūd b. Muḥammad appointed Zangī governor of Mosul and Atabeg of his two sons. The unsettled conditions within the Seljuq sultanate of the west, and the appearance of other, semi-independent Atabeg and Turkish principalities, such as those of the Börids and the Artuqids (see above, no. 92, and below, no. 96), facilitated the rise of the Zangids. From his base at Mosul, Zangī was well placed for expansion westwards through Jazīra into Syria and northwards into eastern Anatolia and Kurdistan. At various times, he defied the Seljuq sultan and clashed with the local Arab and Türkmen amīrs. He also fought the Byzantines and Franks, and his capture in 539/1144 of Edessa or Urfa from Count Jocelyn II, which spelt the end of the Crusader County of Edessa, made him a hero of the Sunnī world.

When Zangī died, his dominions were divided between his sons Sayf al-Dīn Ghāzī I, the elder, who inherited Mosul and its dependencies Sinjār, Irbil and Jazīra, and Nūr al-Dīn Maḥmūd, who took over Zangī’s Syrian conquests. Later, a third branch of the family ruled in Sinjār for some fifty years, a fourth line continued in Jazīra after Mas‘ūd b. Mawdūd in Mawṣil had become an Ayyūbid vassal (see below), while a fifth line ruled briefly at Shahrazūr in Kurdistan. Nūr al-Dīn’s policy in Syria and Palestine against the Crusaders and the declining Fāṭimids paved the way for Saladin’s career there and for the constituting of the Ayyūbid empire. The Syrian branch of the Zangids was later absorbed by the Mosul one, and the Zangids then inevitably came up against the Ayyūbids, who were pursuing an expansionist policy in Jazīra and Diyārbakr. Saladin twice failed to capture Mosul in 578/1182 and 581/1185, but Mas‘ūd I b. Mawdūd was compelled to make terms and to recognise the Ayyūbid as his suzerain.

The end of the Zangīds came with the ascendancy in Mosul of Badr al-Dīn Lu’lu’, the former slave of Arslan Shāh II b. Mas‘ūd II, who after that ruler’s death became regent for the principality. When the last Zangīd Maḥmūd b. Mas‘ūd II died in 631/1234, probably murdered, Lu’lu’ became Atabeg of Mosul, and he and his sons formed a short-lived line there (see below, no. 95) until the advent of Hülegü’s Mongols.

Justi, 461; Lane-Poole, 162–4; Sachau, 27 no. 71; Zambaur, 226–7; Album, 40–1.

EI2 ‘Nūr al-Dīn Maḥmūd b. Zankī’ (N. Elisséeff).

Elisséeff, Nūr al-Dīn, un grand prince musulman de Syrie au temps des Croisades (511–569 H./1118–1174), Damascus 1967.

Ç. Alptekin, The Reign of Zangi (521–541/1127–1146), Erzurum 1978.

D. Patton, Badr al-Dīn Lu’lu’, Atabeg of Mosul, 1211–1259, Seattle and London 1991.

W. F. Spengler and W. G. Sayles, Turkoman Figural Bronze Coins and their Iconography. II. The Zengids, Lodi WI 1996.

Before 529–630/before 1145–1233

North-eastern Iraq and Kurdistan, with a centre at Irbil, and at Ḥarrān in northern Syria

| Before 539/before 1145 | ‘All Küchük b. Begtigin, Zayn al-Dīn, 539/1145 governor of Mosul |

| 563/1168 | Yūsuf b. ‘Alī Küchük, Nūr al-Dīn, in Irbil, d. 586/1190 |

| ⊘ 563/1168 | Gökböri b. ‘Alī Küchük, Abū Sa‘īd Muẓaffar al-Dīn, in Ḥarrān until 586/1190, thereafter in Irbil, d. 630/1233 |

| 630/1233 | Succession of the ‘Abbāsid caliphs in Irbil |

Like the Lu’lu’ids of Mosul (see below, no. 95), the Begtiginids arose out of the Turkish military entourage of the Zangids, in the case of ‘Alī Küchük, that of Zangī b. Aq Sunqur. ‘Alī already controlled extensive lands on the Kurdish fringes of northern Iraq, with his capital in Irbil, when Zangī in 539/1145 gave him the governorship of Mosul also. ‘Alī remained faithful to the Zangids, and secured from them the right to transmit his territories hereditarily. Hence after his death in 583/1168, his sons succeeded at Irbil and Shahrazūr and also in his northern Syrian territories, Gökböri eventually falling sole heir to all of them. He pursued an astute policy of supporting Saladin and the Ayyūbids against the ambitions of Lu’lu’, and, on his death without sons, bequeathed his lands to the ‘Abbāsid caliph al-Mustanṣir. The Begtiginids thus never functioned as a completely independent principality, but nevertheless enjoyed considerable local authority, within the framework of the surrounding greater powers, for almost a century.

Lane-Poole, 165; Zambaur, 228; Album, 41.

EI2 ‘Begteginids’ (Cl. Cahen).

631–60/1234–62

Mosul and Jazīra

| ⊘ 631/1234 | Lu’lu’ b. ‘Abdallāh, Abu ’1-Faḍā’il al-Malik al-Raḥim Badr al-Dīn, d. 657/1259 |

| ⊘ 657–60/1259–62 | Ismā‘īl b. Lu’lu’, al-Malik al-Ṣāliḥ Rukn al-Dīn, in Mosul and Sinjār, k. 660/1262 |

| 657/1259 | ‘Alī b. Lu’lu’, al-Malik al-Muẓaffar ‘Alā’ al-Dīn, in Sinjār |

| 657–60/1259–62 | Isḥāq b. Lu’lu’, al-Malik al-Mujāhid Sayf al-Dīn, in Jazīrat Ibn ‘Umar |

| 660/1262 | Mongol conquest of Mosul and Jazīra |

Lu’lu’ was a freedman of the Zangids of Mosul (see above, no. 93), apparently of Armenian servile origin. Originally regent for the last Zangid prince there, he became officially recognised, with the approval of the ‘Abbāsid caliph, as ruler of the city in 631/1234. In the ensuing years, he extended his authority into Jazīra as Ayyūbid power there waned, but latterly was forced to flee the growing pressure of Mongol raids on Iraq. Lu’lu’ and the local Ayyūbid princes became tributary to the Mongols, and Lu’lu’’s later rule was increasingly subordinate to them, whose overlordship he explicitly acknowledged on his coins in 652/1254. He tried to pass on his power to his sons, dividing up his dominions between them, but when after his death the Il Khān Hülegü invaded as far as Syria (658/1260), Lu’lu’’s sons fled for asylum with the Mamlūks in Egypt, and Iraq and Jazīra now passed firmly under Mongol control.

Lane-Poole, 162–4; Sachau, 27 no. 72; Zambaur, 226; Album, 41.

EI2 ‘Lu’lu’, Badr al-Dīn’ (Cl. Cahen).

D. Patton, Badr al-Dīn Lu’lu’, Atabeg of Mosul, 1211–1259.

c. 494–812/c. 1101–1409

Diyār Bakr

1. The line in Ḥiṣn Kayfā and Āmid 495–629/1102–1232

Artuq b. Ekseb or Eksek, Ẓahīr al-Dawla, Seljuq commander, d. 483/1090 |

|

| 495/1102 | Sökmen I b. Artuq, Mu‘īn al-Dawla, in Ḥiṣn Kayfā and then Mārdīn |

| 498/1104 | Ibrāhīm b. Sökmen I, in Mārdīn |

| 502/1109 | Dāwūd b. Sökmen I, Rukn al-Dawla, in Ḥiṣn Kayfā and then Khartpert |

| ⊘ 539/1144 | Qara Arslan b. Dāwūd, Fakhr al-Dīn, in Ḥiṣn Kayfā and Khartpert |

| ⊘ 562/1167 | Muḥammad b. Qara Arslan, Nūr al-Dīn, also in Āmid |

| ⊘ 581/1185 | Sökmen II b. Muḥammad, al-Malik al-Mas‘ūd Quṭb al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 597/1201 | Maḥmūd b. Muḥammad, al-Malik al-Ṣāliḥ Nāṣir al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 619–29/1222–32 | Mawdūd b. Maḥmūd, al-Malik al-Mas‘ūd Rukn al-Dīn |

| 629–30/1232–3 | Ayyūbid conquest of Ḥiṣn Kayfā and Āmid |

2. The line in Khartpert 581–631/1185–1234

| ⊘ 581/1185 | Abū Bakr b. Qara Arslan, ‘Imād al-Dīn |

| 600/1204 | Ibrāhīm b. Abī Bakr, Niẓām al-Dīn |

| 620/1223 | Aḥmad Khiḍr b. Ibrāhīm, ‘Izz al-Dīn |

| 631/1234 | Artuq Shāh b. Aḥmad, Nūr al-Dīn |

| 631/1234 | Seljuq conquest |

3. The line in Mārdīn and Mayyāfāriqīn c. 494–811/c. 1101–1408

The Turkish Artuqids of Diyār Bakr stemmed from Artuq b. Ekseb, a chief of the Döger tribe of the Oghuz. He is first heard of fighting against the Byzantines in Anatolia, and then the Great Seljuq sultan Malik Shāh (see above, no. 91, 1) sent him, like other Turkmen begs or chiefs, to fight on the peripheries of his empire – in Baḥrayn, Syria and Khurasan. He ended up as governor of Palestine and died in Jerusalem, but his sons were unable to maintain themselves there against the Fāṭimids and Crusaders, and settled instead in Diyār Bakr around Mārdīn and at Ḥiṣn Kayfā. Gradually, 11 Ghāzī I b. Artuq took over Seljuq territories in that region; he was an energetic opponent of the Franks in the County of Edessa, and in 515/1121 (var. 516/1122) he also acquired Mayyāfāriqīn. There were henceforth two main branches of the family, the descendants of Sökmen I in Ḥiṣn Kayfā and later Āmid, and the descendants of his brother Il Ghāzī I in Mārdīn and Mayyāfāriqīn, with a third, subordinate branch at Khartpert which succumbed, however, after half a century of existence to the Seljuqs of Rūm.

As a Turkish dynasty in a region strongly settled by Turkmen begs and their followers, the Artuqid state retained many distinctively Turkish features, seen for example in the personal nomenclature of its princes, with such names as Alp/Alpï ‘warrior, hero’. Yet Diyār Bakr was still strongly Christian also. The Artuqids, however, seem to have been tolerant towards their Christian subjects, with the Patriarch of the Syrian Jacobites periodically resident in Artuqid territory. Much attention has been focused on the distinctive artistic and iconographical features of Artuqid culture, seen for instance in the rulers’ figural coinage, with its apparent classical and Byzantine motifs and representations.

The rise of the Zangids (see above, no. 93) halted the Artuqids’ expansionist plans, and they had to become vassals of Nūr al-Dīn. Then the Ayyūbids whittled their power down further, and they lost Ḥiṣn Kayfā, Āmid and Mayyāfāriqīn to them. In the early thirteenth century, they were for a time vassals of the Rūm Seljuqs and of the Khwārazm Shāh Jalāl al-Dīn Mengübirti. Eventually, only the Mārdīn line survived, with Qara Arslan submitting to the Mongol I1 Khān Hülegü. The end of the dynasty a century and a half later was connected with the fresh wave of Turkmen nomads brought in the wake of the Tīmūrid invasions. The last Artuqids were enveloped by the Qara Qoyunlu confederation, and in 812/1409 Aḥmad b. ‘Īsī was forced to abandon Mārdīn to the Qara Qoyunlu chief Qara Yūsuf (see below, no. 145).

Lane-Poole, 166–9; Zambaur, 228–30; Album, 40.

İA ‘Artuk Oğullari’ (M. F. Köprülü); EI2 ‘Artuḳids’ (CI. Cahen).

O. Turan, Doğa Anadolu Türk devletleri tarihi, Istanbul 1973, 133–240, with list and genealogical table at 244, 281.

L. Ilisch, Geschichte der Artuqidenherrschaft von Mardin zwischen Mamluken und Mongolen 1260–1410 AD, diss. Münster 1984.

G. Väth, Die Geschichte der artuqidischen Fürstentümer in Syrien und der Ğazīra’l-Furātīya (496–812/1002 [sic]-1409), Berlin 1987, with lists and genealogical table at 216–18.

W. F. Spengler and W. G. Sayles, Turkoman Figural Bronze Coins and their Iconography. I. The Artuqids, Lodi WI 1992.

493–604/1100–1207

Akhlāṭ in eastern Anatolia

| 493/1100 | Sökmen I al-Quṭbī |

| 506/1112 | Ibrāhīm b. Sökmen I, Ẓahīr al-Dīn, d. 520/1126 |

| 520 or 521/1126 or 1127 | Aḥmad b. Sökmen I or Ya‘qūb b. Sökmen I |

| 522/1128 | Sökmen II b. Ibrāhīm, Nāṣir al-Dīn, d. 581/1185 |

2. The Sökmenid slave commanders

| ⊘ 581/1185 | Begtimur, Sayf al-Dīn |

| 589/1193 | Aq Sunqur Hazārdīnārī, Badr al-Dīn |

| 593/1197 | Qutlugh, Shujā al-Dīn |

| 593/1197 | Muḥammad b. Begtimur, al-Malik al-Manṣūr |

| 603–4/1207 | Balabān, ‘Izz al-Dīn |

| 604/1207 | Ayyūbid occupation of Akhlāṭ |

In 493/1100, the Turkish slave commander Sökmen took over the town of Akhlāṭ or Khilāṭ on the north-western shore of Lake Van, it having passed from Armenian control to that of the Seljuqs after the battle of Malāzgird or Mantzikert. As heirs to the local Armenian princes, Sökmen and his descendants over three generations assumed the title of Shāh-i Arman. They soon made Akhlāṭ into a base for warfare against the Armenians and Georgians, and the family acquired links with neighbouring dynasties like that of the Artuqids in Mayyāfāriqīn (see above, no. 96, 3), becoming part of a nexus of Turkish principalities in Jazīra and eastern Anatolia which formed a protective screen on the western fringes of the Great Seljuq empire. However, Sökmen II was childless, and on his death in 581/1185 Akhlāṭ was seized by a series of the Sökmenids’ slave commanders. But the Ayyūbids in Diyār Bakr and Jazīra had long coveted the town, and in 604/1207 it was taken over by Najm al-Dīn Ayyūb of Mayyāfāriqīn (see above, no. 30, 6).

Khalīl Ed’hem, 242; Zambaur, 229; Bosworth-Merçil-İpşirli, 85–7.

EI2 ‘Shāh-i Armanids’ (C. Hillenbrand).

O. Turan, Doğu Anadolu Türk devletleri tarihi, 83–106, with list and genealogical table at pp. 243, 279.

c. 516 to after 617/c. 1122 to after 1220

Marāgha and Rū’īn Diz in Azerbaijan

| c. 516/1122 | Aq Sunqur I Aḥmadīlī |

| c. 528/1134 | Aq Sunqur II or Arslan Aba b. Aq Sunqur I, Nuṣrat al-Dīn |

| c. 570/1175 | Falak al-Dīn b. Aq Sunqur II |

| c. 584/1188 | Körp Arslan, ‘Alā’ al-Dīn |

| 604/1208 | ? b. Körp Arslan, d. 605/1209 |

| 605/1209 | Eldigüzid occupation of Marāgha |

| ? | Sulāf a Khātūn, granddaughter of Körp Arslan, ruling in Marāgha and Rū’īn Diz in 617/1220 |

This line of Turkish Atabegs ruled in the restricted area of the town of Marāgha and the nearby fortress of Rū’īn Diz for almost a century, maintaining itself against much more powerful neighbours like the Eldigüzid Atabegs controlling the rest of Azerbaijan (see below, no. 99). Marāgha had been held in the early twelfth century by the Kurdish commander of the Seljuqs, Aḥmadīl b. Ibrāhīm, possibly a descendant of an earlier family in Azerbaijan, the Rawwādids (see above, no. 72), and Aq Sunqur Aḥmadīlī was presumably his freedman. This last became the Atabeg of the Seljuq prince Dāwūd b. Maḥmūd II, and supported him during his brief bid for the sultanate (see above, no. 91, 1). In the later decades of the century, the Aḥmadīlīs were drawn into the complex politics of Azerbaijan, involving the last Seljuqs, the Eldigüzids and other adjoining powers. Notices in the chronicles of this localised line of Atabegs are only sporadic, and numismatic evidence apparently non-existent, so that it is particularly difficult to reconstruct their chronology and genealogy; but they seem to have held Marāgha until 605/1209 and Rū’īn Diz somewhat longer, and a female member of the family, Sulāf a Khātūn, was again ruling in these places when the Mongols sacked Marāgha in 618/1221.

EI2 Aḥmadīlīs’ (V. Minorsky); EIr ‘Atābakān-e Marāgā’ (K. A. Luther).

C. E. Bosworth, in The Cambridge History of Iran, V, 170–1, 176–9.

99

THE ELDIGÜZIDS OR ILDEGIZIDS

c. 540–622/c. 1145–1225

Azerbaijan, Arrān and northern Jibāl

| ⊘ c. 530/c. 1136 | Eldigüz, Shams al-Dīn, effectively independent in Azerbaijan |

| ⊘ 571/1175 | Jahān Pahlawān Muḥammad b. Eldigüz, Abū Ja‘far Nuṣrat al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 582/1186 | Qïzïl Arslan ‘Uthmān b. Eldigüz, Muẓaffar al-Dīn |

| 587/1191 | Qutlugh Inanch, stepson of Jahān Pahlawān Muḥammad, in Arrān and then governor of Jibāl |

| ⊘ 587/1191 | Abū Bakr b. Jahān Pahlawān Muḥammad, Nuṣrat al-Dīn, from 582/1186 ruler in Azerbaijan |

| ⊘ 607–22/1210–25 | Özbeg b. Jahān Pahlawān Muḥammad, Muẓaffar al-Dīn, from 600/1204 ruler in northern Jibāl |

| 622/1225 | Khwārazmian conquest |

The Elgigüzids or Ildegizids were a Turkish Atabeg dynasty who controlled most of Azerbaijan (apart from the region round Marāgha held by another Atabeg line, the Aḥmadīlīs: see above, no. 98), Arrān and northern Jibāl during the second half of the twelfth century when the Great Seljuq sultanate of western Persia and Iraq was in full decay and unable to prevent the growth of virtually independent powers in the provinces.

Eldigüz (the Arabic-Persian sources write ’y.l.d.k.z, but Armenian and Georgian transcriptions of the name seem to indicate a rendering like this) was originally a Qïpchaq military slave of the Seljuq vizier Simirumī, and then passed to Sultan Mas‘ūd b. Muḥammad, who made him governor of Arrān. An adroit marriage to the widow of the Seljuq Sultan Ṭoghrïl II b. Muḥammad enabled him to champion the accession to the throne in 556/1161 of her son Arslan (Shāh), of whom he had been de facto Atabeg, and during Arslan’s reign the Eldigüzids were the power behind the throne and effectively controlled the Great Seljuq sultanate. Their territories now stretched as far south as Iṣfahān, in the west to Akhlāṭ and in the north to the borders of Sharwān and Georgia. Sultan Ṭoghrïl III b. Arslan was for many years held in close tutelage by the Eldigüzids, who at one point claimed the sultanate for themselves, until in 587/1191 he turned the tables on Qutlugh Inanch and was able to pursue an independent policy for the last three years of his life.

In their last phase, the Eldigüzids were once more local rulers in Azerbaijan and eastern Transcaucasia, hard pressed by the aggressive Georgians, and they did not survive the troubled early decades of the thirteenth century. They continued for a while to rule in Azerbaijan, and managed to overthrow their rivals the Aḥmadīlīs, but could not withstand the superior élan of the Khwārazm Shāhs, and in 622/1225 Jalāl al-Dīn Mengübirti finally deposed Özbeg b. Jahān Pahlawān Muḥammad. The historical significance of these Atabegs thus lies in their firm control over most of north-western Persia during the later Seljuq period and also in their role in Transcaucasia as champions of Islam against the resurgent Bagratid Georgian kings.

Justi, 461; Lane-Poole, 171; Zambaur, 231; Album, 41–2.

EI2 ‘Ildeñizids or Eldigüzids’ (C. E. Bosworth); EIr ‘Atābakān-e Ādarbayjān’ (K. A. Luther).

Bosworth, in The Cambridge History of Iran, V, 169–71, 176–83.

D. K. Kouymjian, A Numismatic History of Southeastern Caucasia and Adharbayjān, 56–60, 288–368, with a genealogical table at p. 368.

c. 493 to the tenth century/c. 1100 to the sixteenth century

The Caspian coastland districts of Rūyān and Rustamdār

1. The rulers of the united principality

| ⊘ ? | Naṣr b. Sharīwash (? Shahrnūsh), Sharaf al-Dīn, Nāṣir al-Dawla, ruling in 502/1109 |

| ? | Shahrīwash b. Hazārasp, ruling c. 553/1168 |

| ? | Kay Kāwūs b. Hazārasp, d. c. 580/c. 1184 |

| c. 580–1 /c. 1184–5 | Hazārasp b. Shahrīwash |

| ? | Zarrīn Kamar b. Justān b. Kay Kāwūs, d. 610/1213 |

| 610–20/1213–23 | Bīsutūn b. Zarrīn Kamar, d. 620/1223 |

| later 620s/early 1230s | Nāmāwar b. Bīsutūn, Fakhr al-Dawla, d. 640/1242 |

| 640/1242 | Ardashīr b. Nāmāwar, Ḥusām al-Dawla, in Daylam, d. 640/1242 |

| 640/1242 | Iskandar b. Nāmāwar, in Rūyān |

| 640/1242 | Shahrāgīm b. Nāmāwar, in Daylam and Rūyān, d. 671/1273 |

| 671/1273 | Nāmāwar Shāh Ghāzī b. Shahrāgīm, Fakhr al-Dawla |

| 701/1302 | Kay Khusraw b. Shahrāgīm |

| 712/1312 | Muḥammad b. Kay Khusraw, Shams al-Mulūk |

| 717/1317 | Shahriyār b. Kay Khusraw, Nāṣir al-Dīn |

| 725/1325 | Ziyār b. Kay Khusraw, Tāj al-Dawla |

| 734/1334 | Iskandar b. Ziyār, Jalāl al-Dawla |

| 761/1360 | Shāh Ghāzī b. Ziyār, Fakhr al-Dawla |

| 781/1379 | Qubād b. Shāh Ghāzī, ‘Aḍud al-Dawla, d. 783/1381 |

| 783–92/1381–90 | Rule in Rūyān by the Mar‘ashī Sayyids |

| 792/1390 | Ṯūs b. Ziyār, Sa‘d al-Dawla, d. 796/1394 |

Tīmūrid occupation of the Caspian coastlands |

|

| c. 802/c. 1400 | Kayūmarth b. Bīsutūn b. Gustahm b. Ziyār |

| 857/1453 | Division of the kingdom into two branches |

2. The rulers in Kujūr (with the title of Malik)

| c. 858/c. 1454 | Iskandar b. Kayūmarth |

| 881/1476 | Tāj al-Dawla b. Iskandar |

| 897/1492 | Ashraf b. Tāj al-Dawla |

| 915/1509 | Kāwūs b. Ashraf |

| 950/1543 | Kayūmarth b. Kāwūs |

| 963/1556 | Jahāngīr b. Kāwūs |

| 975/1568 | Sulṭān Muḥammad b. Jahāngīr |

| 998-1004 or 1006/ | Jahāngīr b. Muḥammad |

| 1590-1596 or 1598 | Direct rule by the Ṣafawids |

3. The rulers in Nūr (with the title of Malik)

| c. 858/c. 1454 | Kāwūs b. Kayūmarth |

| 871/1467 | Jahāngīr b. Kāwūs |

| 904/1499 | Bīsutūn b. Jahāngīr |

| 913/1507 | Bahman b. Bīsutūn |

| 957/1550 | Kayūmarth b. Bahman, d. after 984/1576 |

| ? | Sulṭān ‘Azīz b. Kayūmarth |

| ?–1002/?–1594 | Jahāngīr b. ‘Azīz |

| 1002/1594 | Power assumed by the Ṣafawids |

The line of the Bādūspānids in the Caspian region claimed a connection, which cannot however be demonstrated with any certainty, with earlier rulers of Rūyān; these last had asserted their descent from the semi-legendary Bādūspān, a contemporary of the Dābūyids of Gīlān (see above, no. 79), hence going back to late Sāsānid times. The Bādūspānids, who are known from the late eleventh century onwards, bore the historic, local title of Ustāndār, and later that of Malik or king, but they seem to have been unconnected with the immediately preceding line of Ustāndārs. They first appear as vassals of the Seljuqs, and within the Caspian region they were neighbours and kinsmen by marriage of the Bāwandids (see above, no. 80) and other petty rulers there, including, latterly, the Mar‘ashī Sayyids of Māzandarān. They survived the Mongols and Tīmūrids, but after the mid-fifteenth century they split into two parallel branches, ruling in Kujūr and Nūr respectively, until their lands were incorporated by Shāh ‘Abbās I into the Ṣafawid empire.

Justi, 433–5; Sachau, 8–9 nos 8–10; Zambaur, 190–1, both these latter being unreliable.

EI2 ‘Bādūsbānids’ (B. Nikitine); EIr ‘Bādūspānids’ (W. Madelung), the most reliable account, on which the above is based.

H. M. Rabino, ‘Les dynasties du Māzandarān de l’an 50 avant l’Hégire à l’an 1006 de l’Hégire (572 à 1597–1598) d’après les chroniques locales’, JA, 228 (1936), 443–74.

101

THE NIZĀRĪ ISMĀ ‘ĪLĪS OR ASSASSINS IN PERSIA

483–654/1090–1256

Various mountainous regions of Persia, with their main centre at Alamūt

| 483/1090 | Ḥasan-i Ṣabbāḥ (al-Ḥasan b. ‘Alī b. al-Ṣabbāḥ), Fāṭimid and then Nizārī dā‘ī in northern and western Persia |

| 518/1124 | Kiyā Buzurg Ummīd b. Ḥasan-i Ṣabbāḥ |

| ⊘ 532/1138 | Muḥammad I b. Kiyā Buzurg Ummīd |

| ⊘ 557/1162 | Ḥasan II b. Muḥammad I, ‘Alā Dhikrihi ’1-Salām |

| 561/1166 | Muḥammad II b. Ḥasan II, Nūr al-Dīn |

| 607/1210 | Ḥasan III b. Muḥammad II, Jalāl al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 618/1221 | Muḥammad III b. Ḥasan III, ‘Alā’ al-Dīn |

| 653–4/1255–6 | Khwurshāh b. Muḥammad III, Rukn al-Dīn, killed 654/1256 |

| 654/1256 | Mongol capture of Alamūt |

As noted above concerning the Syrian Ismā‘īlīs (no. 29), the Nizārī da‘wa arose from a split within the Fāṭimid caliphate. Ḥasan-i Ṣabbāḥ had already been spreading Ismā‘īlī teachings in Persia before the death of the caliph al-Mustanṣir in 487/1094 and the al-Musta‘lī-Nizār split over succession to the imamate of the Ismā‘īlīs. The Persian devotees acknowledged Nizār, and Ḥasan-i Ṣabbāḥ became their leader with the title, in the absence of the Imām, of Ḥujja ‘Proof, demonstration of the truth’. Ḥasan secured the mountain fortress of Alamūt in Daylam, in north-western Persia, where there was a long tradition of heterodoxy and sympathy for Shī‘ism. From here, Ḥasan also organised the Syrian da‘wa (see above, no. 29), and within Persia, from the Caspian region fortresses and those in the Iṣfahān region, a series of attacks on the Great Seljuq state. Given the comparatively small numbers of the Ismā‘īlīs, these were necessarily more like guerilla actions than full-scale campaigns, and the weapon of religious and political assassination was also used, creating an atmosphere of fear and suspicion within orthodox Sunnī circles which almost certainly exaggerated the real power of the Ismā‘īlīs. Hence these last became in the popular mind the so-called Assassins of the Crusader sources (< Ḥashīshiyyūn or Ḥashshāshūn ‘hashish eaters’, reflecting a belief that the Ismā‘īlī agents were inspired to their daring feats of assassination through the use of hallucinatory drugs).

The Fourth Grand Master in Alamūt, Ḥasan II, assumed the more exalted religious function of Imām, but in the thirteenth century Ismā‘īlī extremism began to moderate somewhat, and the ‘Abbāsid caliph al-Nāṣir secured a great propaganda success in the contemporary Sunnī world by achieving the return of Ḥasan III to orthodoxy. However, the last Grand Master, Khwurshāh, was unable to withstand Hülegü’s Mongols; Alamūt was stormed in 654/1256 and Khwurshāh seems to have been killed by the victors. Ismā‘īlism survived in some of the remoter parts of Persia in a modest and diminished fashion, but the history of the continuing imamate in Persia is very obscure until the eighteenth century.

Justi, 457; Sachau, 15 no. 26; Zambaur, 217–18 (inaccurate); Album, 42.

EI2 ‘Ismā‘īliyya’ (W. Madelung).

M. G. S. Hodgson, The Order of Assassins: The Struggle of Early Nizârî Ismâ‘îlîs against the Islamic World, The Hague 1955, 37–270, with a table at p. 42.

G. C. Miles, ‘Coins of the Assassins of Alamūt’, Orientalia Lovaniensia, 3 (1972), 155–62.

Farhad Daftary, The Isma‘īlīs: Their History and Doctrines, 324–434, with a table at p. 553.

543–827/1148–1424

Luristān

| 543–56/1148–61 | Abū Ṭāhir (? b.‘ Alī) b. Muḥammad, d. 556/1161 |

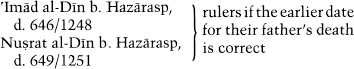

| c. 600/c. 1204 | Malik Hazārasp b. Abī Ṭāhir, Nuṣrat al-Dīn, d. 626/1229 or 650/1252 |

|

|

| before 655/before 1257 | Tekele or Degele b. Hazārasp, killed c. 657/c. 1259 |

| c. 657/c. 1259 | Alp Arghu(n) b. Hazārasp, Shams al-Dīn |

| 673/1274 | Yūsuf Shāh I b. Alp Arghu(n) |

| c. 687/c. 1288 | Afrāsiyāb I b. Yūsuf Shāh I, d. 695/1296 |

| 696/1296 | Aḥmad b. Alp Arghu(n), Nuṣrat al-Dīn |

| 730 or 733/1330 or 1333 | Yūsuf Shāh II b. Aḥmad, Rukn al-Dīn |

| 740/1339 | Afrāsiyāb II Aḥmad b. Yūsuf Shāh II (or b. Aḥmad), Muẓaffar al-Dīn |

| 756/1355 | Nawr al-Ward b. Afrāsiyāb II |

| 756/1355 | Pashang b. ? Yūsuf Shāh II, Shams al-Din |

| 780/1378 | Pīr Aḥmad b. Pashang, challenged early in his reign by his brother Hūshang |

| 811/1408 | Abū Sa‘īd b. Pīr Aḥmad |

| c. 820/c. 1417 | Shāh Ḥusayn b. Abī Sa‘īd |

| 827/1424 | Ghiyāth al-Dīn b. Kāwūs b. Hūshang |

| 827/1424 | Tīmūrid conquest |

This line of the so-called Atabegs of Luristān ruled in Lur-i Buzurg, namely the eastern and southern parts of Luristān in western Persia from a centre at Īdhaj or Mālamīr. They were ultimately of Kurdish stock, and the founder Abū Ṭāhir traced his ancestry back to the Shabānkāra’ī chief Faḍlūya of early Seljuq times. Abū Ṭāhir himself was a commander of the Salghurid Atabegs of Fars (see below, no. 103) who eventually made himself independent in Luristān of his masters, extended his territories almost as far east as Iṣfahān and assumed the by that time prestigious Turkish title of Atabeg. Subsequent Hazāraspids ruled under the aegis of the Il Khānids, to whose army they had at times to send troops, but were later involved in the civil wars of the Muẓaffarids of Fars (see below, no. 140). When Tīmūr overran this region of south-western Persia, he confirmed them in power, but his grandson Ibrāhīm b. Shāh Rukh ended their power in 827/1424.

It should be further noted that another line of Lurī so-called Atabegs ruled in Lur-i Kūchik, that is northern and western Luristān, from the later twelfth century until the time of the Ṣafawid Shāh ‘Abbās I.

Justi, 460–1; Lane-Poole, 174–5; Zambaur, 234–5.

EI2 ‘Hazāraspids’ (B. Spuler), ‘Lur-i Buzurg’, ‘Lur-i Kūčik’ (V. Minorsky); EIr ‘Atābakān-e Lorestān’ (Spuler).

Spuler, Die Mongolen in Iran. Politik, Verwaltung und Kultur der Ilchanzeit 1220–1350, 4th edn, Leiden 1985, 134–5.

543–681/1148–1282

Fars

| ⊘ 543/1148 | Sunqur b. Mawdūd, Muẓaffar al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 556/1161 | Zangī b. Mawdūd, Muẓaffar al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 570/1175 or 574/1178 Tekele or Degele b. Zangī | |

| ⊘ 594/1198 | Sa‘d I b. Zangī, Abū Shujā‘ Muẓaffar al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 623/1126 | Qutlugh Khān b. Sa‘d I, Abū Bakr Muẓaffar al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 658/1260 | Sa‘d II b. Qutlugh Khān, Muẓaffar al-Dīn |

| 658/1260 | Muḥammad b. Sa‘d II, ‘Aḍud al-Dīn |

| 661/1262 | Muḥammad Shāh b. Salghur Shāh b. Sa‘d I, Muẓaffar al-Dīn |

| 661/1263 | Seljuq Shāh b. Salghur Shāh, Muẓaffar al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 662/1263 | Ābish Khātūn b. Sa‘d II, Muẓaffar al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 663–81/1264–82 | Ābish Khātūn and her husband Mengü Temür b. Hülegü, jointly |

| 681/1282 | Direct Il Khānid rule |

The Atabeg dynasty of the Salghurids ruled in Fars for over a century as vassals first of the Seljuqs and then, in the thirteenth century, of the Khwārazm Shāhs and Mongols. They were of Türkmen origin, possibly from the Salur or Salghur tribe which had formed part of the Oghuz and which had come westwards at the time of the Seljuq invasions, playing a significant part in the establishment of the Sultanate of Rūm (see below, no. 107). The founder of the Fars line, Sunqur, took advantage of the warfare and disputes which disturbed the reign of the Great Seljuq sultan Mas‘ūd b. Muḥammad in order to consolidate his position in southern Persia, after Fars had already been under the control of another Turkish Atabeg, Boz Aba. With the decline of the Great Seljuqs, the Salghurids could then enjoy uninterrupted possession of Fars, campaigning against the local Shabānkāra’ī Kurds and intervening in succession disputes among the neighbouring, last Kirman Seljuqs (see above, no. 91, 3).

Fars enjoyed considerable prosperity under Sa‘d I b. Zangī, although he had latterly to acknowledge the suzerainty of the Khwārazm Shāhs and to link his family with them by means of marriage alliances. The Persian writer Sa‘dī dedicated his Bustān and Gulistān to Sa‘d I and his short-reigning son Sa‘d II respectively, and it was from the latter that he derived his pen-name. In the reign of Sa‘d I’s son and successor Abū Bakr, Fars came under the suzerainty of the Mongol Great Khān Ögedey and then under that of the I1 Khānid Hülegü (see below, no. 133), and it was from the Mongols that Abū Bakr acquired his title of Qutlugh Khān. After a series of ephemeral Salghurids, Sa‘d II’s daughter Ābish Khātūn was made Atabeg of Fars by Hülegü, with her husband, the II Khān’s son Mengü Temür, taking over de facto power shortly afterwards, until Salghurid power was ended completely at Mengü Temür’s death and Fars was incorporated directly into the I1 Khānid realm.

Justi, 460; Lane-Poole, 172–3; Zambaur, 232; Album, 42.

EI2 ‘Salghurids’ (C. E. Bosworth); EIr ‘Atābakān-e Fārs’ (B. Spuler).

B. Spuler, Die Mongolen in Iran, 4th edn, 117–21.

Bosworth, in The Cambridge History of Iran, V, 172–3.

Erdoğan Merçil, Fars Atabegleri Salgurlular, Ankara 1975, with a genealogical table at p. 146.

c. 536–696/c. 1141–1297

| c. 536/1141 | Sām b. Wardānrūz, Rukn al-Dīn, d. 590/1194 |

| c. 584/1188 | Langar b. Wardānrūz, ‘Izz al-Dīn, succeeded during his father’s lifetime and reigned for nearly twenty years, d. 604/1207 |

| 604/1207 | Wardānrūz b. Langar, Muḥyī ’l-Din |

| 616/1219 | Isfahsālār b. Langar, Abū Manṣūr Quṭb al-Dīn |

| 626/1229 | Maḥmūd Shāh b. Abī Manṣūr Isfahsālār |

| 639/1241 | Salghur Shāh b. Maḥmūd Shāh |

| 650/1252 | Ṭogha(n) Shāh b. Salghur Shāh |

| ⊘ 670/1272 | ‘Alā’ al-Dawla b. Ṭogha(n) Shāh |

| ⊘ 673/1275 | Yūsuf Shāh b. Ṭogha(n) Shāh |

| 696/1297 | Mongol conquest |

| c. 715–18/c. 1315–18 | Ḥājjī Shāh b. Yūsuf Shāh, overthrown by local rivals |

| 719/1319 | Muẓaffarid governor |

This line of local rulers in the central Persian town of Yazd succeeded the branch of the Kākūyids there (see above, no. 78). From the names of their earlier members at least, it seems that they were ethnically Persian, but, like the Hazāraspids (see above, no. 102), they adopted the Turkish title of Atabeg. This came about because the Great Seljuq sultan Sanjar appointed the founder of the line, Sām b. Wardānrūz, Atabeg to the daughters of the deceased last Kākūyid, Abū Kalījār Garshāsp II, in c. 536/c. 1141. Sām’s successors were at first vassals of the Seljuqs and then, in the the next century, tributary to the Mongols; the Atabeg Ṭogha(n) Shāh b. Salghur Shāh had to send troops to the Mongol army attacking Alamūt and other Ismā‘īlī fortresses of northern Persia in 654/1256. The penultimate Atabeg, Yūsuf Shāh, fell into arrears of tribute, and had to flee to Sistan before an army sent out by the I1 Khānid Ghazan, after which a Mongol darugha or police commander was appointed over Yazd. A son of his was reappointed over Yazd in c. 715/c. l315, but was overthrown three years later by local rivals and the town soon afterwards passed under the control of the Muẓaffarids (see below, no. 140) as vassals of the I1 Khānids.

Sachau, 27 no. 66; Zambaur, 231.

EIr ‘Atābakān-e Yazd’ (S. C. Fairbanks).

Ja‘far b. Muḥammad b. Ḥasan Ja‘farī, Ta ’rīkh-i Yazd, ed. Īraj Afshār, Tehran 1338/1960, 23–9.

Aḥmad b. Ḥusayn b. ‘Alī Kātib, Ta ’rīkh -i jadīd-i Yazd, ed. Afshār, Tehran 1345/1966, 66–79.

619–706/1222–1307

Kirman

| 619/1222 | Baraq Ḥājib b. K.l.d.z, Abu ’1-Fawāris Qutlugh Sulṭān, Nāṣir al-Dunya wa ’1-Dīn |

| 632/1235 | Muḥammad b. ? Khamītūn, Abu ’1-Fatḥ Quṭb al-Dīn, first reign |

| 633/1236 | Mubārak b. Baraq, Rukn al-Dīn |

| 650/1252 | Muḥammad b. ? Khamītūn, second reign |

| 655/1257 | Qutlugh Terken, Quṭb al-Dīn II ‘Iṣmat al-Dunyā wa ’1-Dīn, regent for Muḥammad b. ? Khamītūn’s son Ḥajjāj Sulṭān |

| 681/1282 | Soyurghatmïsh b. Muḥammad, Abu ’l-Muẓaffar Jalāl al-Dīn, killed 693/1294 |

| 691/1292 | Pādishāh Khātūn bt. Muḥammad, Safwat al-Dīn, killed 694/1295 |

| ⊘ 695/1296 | Muḥammad Shāh Sulṭān b. Ḥajjāj Sulṭān, Abu ’1-Ḥārith Muẓaffar al-Dīn |

| 703/1304 | Shāh Jahān b. Soyurghatmïsh, Quṭb al-Dīn, deposed 704/1305 |

| 706/1306 | Mongol governor appointed |

These local rulers in Kirman sprang from a commander in the service of the Buddhist Qara Khitay, who had migrated from the northern fringes of the Chinese empire and had overrun Transoxania in the mid-twelfth century (see above, no. 90). This founder of the Qutlughkhānid line, Baraq, whose title of Qutlugh Sulṭān was bestowed on him by the ‘Abbāsid caliph, had in fact only recently been converted to Islam. He was awarded Kirman, and this became the centre of the line’s power for nearly a century. His kinsmen and successors were closely connected with the Mongols, serving them in their far-flung empire and latterly governing Kirman as vassals of the Il Khānids. Notable is the role among them of two forceful women, the regent Qutlugh Terken and Pādishāh Khātūn. The last Qutlughkhānid, Shāh Jahān b. Soyurghatmïsh, fell into arrears with the tribute due to the Il Khānids, and was deposed by Öljeytü. His daughter later married Mubāriz al-Dīn Muḥammad, the real founder of Muẓaffarid power in Fars (see below, no. 140), who subsequently took possession of Kirman.

Lane-Poole, 179–80; Zambaur, 237.

EI2 ‘Kirmān. History’ (A. K. S. Lambton); ‘Kutlugh-Khānids’ (V. Minorsky).

421–c. 949/1030–c. 1542

Sistan

| 421–2/1030–1, | |

| 425–7/1034–6, | |

| 429–65/1038–73 | Naṣr b. Aḥmad, Abu ’1-Faḍl Tāj al-Dīn I |

| 465/1073 | Ṭāhir b. Naṣr Tāj al-Dīn I, Bahā’ al-Dawla |

| 480/1088 | Abu ’l-‘Abbās b. Naṣr Tāj al-Dīn I, Badr al-Dawla |

| 482/1090 | Khalaf b. Naṣr Tāj al-Dīn I, Bahā’ al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 499/1106 | Naṣr b. Khalaf, Abu ’1-Faḍl Tāj al-Dīn II |

| ⊘ 559/1164 | Muḥammad or Aḥmad b. Naṣr Tāj al-Dīn II, Shams al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 564/1169 | Ḥarb b. Muḥammad ‘Izz al-Mulūk b. Naṣr, Tāj al-Dīn III |

| 610/1213 | Bahrām Shāh b. Ḥarb Tāj al-Dīn III, Yamīn al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 618–19/1221–2 | Nuṣrat or Naṣr b. Bahrām Shāh Yamīn al-Dīn, Tāj al-Dīn IV |

| 618/1221 | Maḥmūd b. Ḥarb Tāj al-Dīn III, Shihāb al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 618–19/1221–2 | Maḥmūd b. Bahrām Shāh Yamīn al-Dīn, Rukn al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 619/1222 | ‘Alī b. Ḥarb Tāj al-Dīn III, Abu ’1-Muẓaffar |

| 620/1223 | Aḥmad b. ‘Uthmān Nāṣir al-Dīn b. Ḥarb Tāj al-Dīn III, ‘Alā’ al-Dīn |

| 622/1225 | ‘Uthmān Shāh b. ‘Uthmān Nāṣir al-Dīn |

| 622/1225 | Seizure of power by Inaltigin Khwārazmī |

| 633/1236 | ‘Alī b. Mas‘ūd b. Khalaf b. Mihrabān, Shams al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 653/1255 | Muḥammad b. Abi ’1-Fath Mubāriz al-Dīn, Nāṣir al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 718/1318 | Muḥammad b. Muḥammad Nāṣir al-Dīn, Nuṣrat al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 731/1330 | Muḥammad b. Maḥmūd Rukn al-Dīn, Quṭb al-Dīn I |

| ⊘ 747/1346 | Tāj al-Dīn b. Muḥammad Quṭb al-Dīn I |

| ⊘ 751/1350 | Maḥmūd b. Maḥmūd Rukn al-Dīn, Jalāl al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 753/1352 | ‘Izz al-Dīn Karmān b. Maḥmūd Rukn al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 782/1380 | Quṭb al-Dīn II b. ‘Izz al-Dīn |

| 788/1386 | Shāh-i Shāhān Abu ’1-Fatḥ b. Mas‘ūd Shiḥna, Tāj al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 806/1404 | Muḥammad b. ‘Alī Shams al-Dīn, Quṭb al-Dīn III |

| ⊘ 822/1419 | ‘Alī b. Muḥammad Quṭb al-Dīn III, Shams al-Dīn or ‘Alā’ al-Dīn |

| 842/1438 | Yaḥyā b. ‘Ali Shams al-Dīn or ‘Alā’ al-Dīn, Niẓām al-Dīn, d. 885/1480 |

| ? c. 890/c. 1485 | Muḥammad b. Yaḥyā Niẓām al-Dīn, Shams al-Dīn |

| ? 900/1495 | |

| or 906/1501 | Sulṭān Maḥmūd b. Yaḥyā Niẓām al-Dīn, d. in Shāh Ṭahmāsp I Ṣafawī’s reign, possibly as late as 949/1542 |

Incorporation of Sīstān into the Ṣafawid realm |

Zambaur considered that these Maliks of Nīmrūz (an ancient name for Sistan which was revived and became increasingly used at this time) formed third and fourth lines of the earlier Ṣaffārids (see above, no. 84). However, the anonymous author of the almost contemporary local history, the Ta’rīkh-i Sīstān, considered that the true Ṣaffārids came to an end with the Ghaznawid occupation of his province in 993/1003. From the pages of his continuator(s) and from those of the other, later, local history of Sistan, Malik Shāh Ḥusayn’s Iḥyā’ al-mulūk, it is clear that we are now dealing with two entirely separate lines of Maliks, the Naṣrids and the Mihrabānids, with no apparent connections with earlier rulers; both must have stemmed from the local landowning families of Sistan.

The Naṣrids rose to power as discontent in Sistan with alien Ghaznawid rule increased in the early decades of the eleventh century. Content with only a local authority, the Naṣrids skilfully exchanged Ghaznawid suzerainty for that of the incoming Seljuqs, and during the twelfth century the Maliks at times provided troop contingents for the Seljuq armies. They also managed to ward off incursions by the Ismā’īlīs of neighbouring Quhistān. To Tāj al-Dīn II Abu ’1-Faḍl Naṣr is attributed the building of the fairly recently-collapsed Mīl-i Qāsimābād in Sīstān. Towards the end of the twelfth century, Sistan fell under the shadow of the Ghūrids (see below, no. 159), then in the early thirteenth century briefly under that of the Khwārazm Shāhs, but the appearance of the Mongols in Sistan in 619/1222 and the resultant destruction there spelt the end for the Naṣrids.

The first Mihrabānids were vassals of the Mongol Great Khāns and then of the Il Khānids, whose protection, in return for tribute, they needed against the expansionist policies of the Kart Maliks of Herat (see below, no. 139) and against the depredations of anarchic, plundering bands of Turco-Mongol freebooters, such as the Negüders or Nīkūdārīs. The Mihrabānids were, in any case, rarely free from internal challenges by members of rival leading families of Sistan. For these Maliks, the Iḥyā’ al-mulūk (see above) becomes virtually the only source after c. 718/c. 1318, for Sistan now began to sink into the obscurity and the social and economic decline which have characterised it until recent times. This decay was aggravated by the ravages at the end of the fourteenth century of Tīmūr and his troops, with devastation to Sistan’s irrigation system. The province was tributary to the Tīmūrids of Herat and then under pressure from the Aq Qoyunlu (see below, no. 146), and finally passed into the Ṣafawid orbit. The last decades of the Mihrabānids are obscure, but the increased threat to the Ṣafawids’ eastern frontiers from the Özbegs seems to have persuaded Shāh Ṭahmāsp I to appoint his own Qïzïl Bash amīrs over Sistan. Because of the paucity of source material, both literary and numismatic, much in the succession and genealogical connections of the Mihrabānids still remains obscure.

Justi, 439 (the Naṣrids only); Zambaur, 200–1 (sketchy and unreliable); Album, 50.

EI2 ‘Sīstān’ (C. E. Bosworth).

C. E. Bosworth, The History of the Saffarids of Sistan and the Maliks of Nimruz (247/861 to 949/1542–3), 365–477, Costa Mesa CA and New York, 1994, with genealogical tables at pp. xxv–xxvi.