SIXTEEN

Afghanistan and the

Indian Subcontinent

366–582/977–1186

Afghanistan, Khurasan, Baluchistan and north-western India

⊘ 366/977 |

Sebüktigin b. Qara Bechkem, Abū Manṣūr Nāṣir al-Dīn wa ’l-Dawla, governor in Ghazna for the Sāmānids |

⊘ 387/997 |

Ismā‘īl b. Sebüktigin |

⊘ 388/998 |

Maḥmūd b. Sebüktigin, Abu ’1-Qāsim Sayf al-Dawla, Yamīn al-Dawla wa-Amīn al-Milla |

⊘ 421/1030 |

Muḥammad b. Maḥmūd, Abū Aḥmad Jalāl al-Dawla, first reign |

⊘ 421/1031 |

Mas‘ūd I b. Maḥmūd, Abū Sa‘īd Shihāb al-Dawla |

432/1040 |

Muḥammad b. Maḥmūd, second reign |

⊘ 432/1041 |

Mawdūd b. Mas‘ūd, Abu’1-Fath Shihāb al-Dawla |

? 440/1048 |

Mas‘ūd II b. Mawdūd, Abū Ja‘far |

? 440/1048 |

‘Alī b. Mas‘ūd, Abu’1-Ḥasan Bahā’ al-Dawla |

⊘ ? 440/1049 |

‘Abd al-Rashīd b. Maḥmūd, Abū Mansūr ‘Izz al-Dawla wa-Zayn al-Milla |

⊘ 443/1052 |

Usurpation in Ghazna of the slave commander Abū Sa‘īd Ṭoghrïl, Qiwām al-Dawla |

⊘ 443/1052 |

Farrukhzād b. Mas‘ūd I, Abū Shujā‘ Jamāl al-Dawla wa-Kamāl al-Milla |

⊘ 451/1059 |

Ibrāhīm b. Mas‘ūd, Abu ’1-Muzaffar Zahīr al-Dawla wa-Nāūṣir al-Milla |

⊘ 492/1099 |

Mas‘ūd III b. Ibrāhīm, Abū Sa‘d Abu’1-Mulūk ‘Alā’al-Dawla wa’l-Dīn |

508/1115 |

Shīrzād b. Mas‘ūd III, ‘Adud al-Dawla, Kamāl al-Dawla |

⊘ 509/1116 |

Malik Arslan or Arslan Shāh b. Mas‘ūd III, Sultān al-Dawla |

510/1117 |

Seljuq occupation of Ghazna |

0511/1117 |

Bahrām Shāh b. Mas‘ūd III, Abu’ 1-Muẓaffar Yamīn al-Dawla wa-Amīn al-Milla, first reign |

545/1150 |

Ghūrid occupation of Ghazna |

547/1152 or after |

Bahrām Shāh b. Mas‘ūd III, second reign |

⊘ ? 552/1157 |

Khusraw Shāh b. Bahrām Shāh, Mu‘izz al-Dawla, latterly in north-western India only |

⊘ 555–82/1160–86 |

Khusraw Malik b. Khusraw Shāh, Abu’1-Muzaffar Tāj al-Dawla, in north-western India, k. 587/1191 |

582/1186 |

Ghūrid conquest |

On the death in 350/961 of the Sāmānid Amīr ‘Abd al-Malik (see above, no. 83), the Turkish slave commander of the Sāmānid army in Khurasan, Alptigin, attempted to manipulate the succession at Bukhara in his own favour. He failed, and was obliged to withdraw with some of his troops to Ghazna in what is now eastern Afghanistan. Here on the periphery of the Sāmānid empire, and facing the pagan subcontinent of India, a series of Turkish commanders followed Alptigin, governing nominally for the Sāmānids, until in 366/977 Sebüktigin came to power. Under him, the Ghaznawid tradition of raiding the plains of India in search of treasure and slaves was established, but it was his son Maḥmüd who became fully independent and who achieved a reputation throughout the eastern Islamic world as hammer of the infidels, penetrating down the Ganges valley to Muttra (Mat‘hurā) and Kanawj and into the Kathiawar (Kāt́lāār) peninsula to attack the famous idol temple there of Somnath (Sūmanāt). In the north, he set up the Oxus as his frontier with the rival power of the Qarakhanids (see above, no. 90), and annexed Khwārazm. The former Sāmānid province of Khurasan was taken over and, towards the end of his life, Maḥmüd’s armies marched into northern and western Persia and overthrew the Būyid amirate there (see above, no. 75, 1).

Maḥmūd’s empire at his death was thus the most extensive and imposing edifice in eastern Islam since the time of the Ṣaffārids (see above, no. 84), and his army the most effective military machine of the age. With the adoption of Persian administrative and cultural ways, the Ghaznawids threw off their original Turkish steppe background and became largely integrated with the Perso-Islamic tradition. But under his son Mas‘ūd I, Maḥmūd’s empire – essentially a personal creation – could not be maintained in the west against the Seljuqs (see above, no. 91), and Khwārazm, Khurasan and northern Persia were lost to the incomers. The middle years of the eleventh century were largely spent in warfare with the Seljuqs over possession of Sistan and western Afghanistan. At the accession of Ibrahim b. Mas‘ūd in 451/1059, a modus vivendi was worked out with the Seljuqs, and peace reigned substantially for over half a century.

Reduced as it now was to eastern Afghanistan, Baluchistan and north-western India, the Ghaznawid empire was still an imposing and powerful one. It inevitably acquired a more pronounced orientation towards India, but the courts of the sultans of the twelfth century were centres of a splendid Persian culture, with such luminaries as the mystical poet Sanā‘ī. In the early part of that century, the Ghaznawid Bahrām Shāh became tributary to the Seljuqs, for Sanjar had helped Bahrām Shāh secure his throne. Towards the end of the latter’s reign, the capital Ghazna suffered a frightful sacking by the ‘World Incendiary’, the Ghūrid ‘Alā’ al-Dīn Husayn (see below, no. 159). The rise of the Ghūrids in fact reduced the power of the last Ghaznawids, and their rule was latterly confined to the Punjab (Panjāb) until the Ghūrid Mu‘izz al-Dīn Muḥammad finally extinguished the line in 582/1186.

Justi, 444; Lane-Poole, 285–90; Zambaur, 282–3; Album, 36–7.

EI2 ‘Ghaznawids’ (B. Spuler); EIr ‘Ghaznavids’ (C. E. Bosworth).

C. E. Bosworth, The titulature of the early Ghaznavids’, Oriens, 15 (1962), 210–33. idem, The Ghaznavids. Their Empire in Afghanistan and Eastern Iran 994:1040, Edinburgh 1963.

idem, The early Ghaznavids’, in The Cambridge History of Iran, IV, 162–97.

idem, The Later Ghaznavids: Splendour and Decay. The Dynasty in Afghanistan and Northern India 1040–1186, Edinburgh 1977.

Early fifth century to 612/early eleventh century to 1215 Ghūr, Khurasan and north-western India

1. The main line in Ghūr and then also in Ghazna

? |

Muḥammad b. Sūrī Shansabānl, chief in Ghūr |

401/1011 until |

|

the 420s/1030s |

Abū ‘Alī b. Muḥammad, Ghaznavid vassal |

? |

‘Abbās b. Shīth |

after 451/1059 |

Muḥammad b.‘Abbās |

? |

Ḥasan b Muḥmmad, Quṭb al-Dīn |

493/1100 |

Ḥusayn I b. Ḥasan, Abu ’1-Mulūk ‘Izz al-Dīn |

540/1146 |

Sūri b. Husayn I, Sayf al-Dīn, in Flrūzkūh as Malik al-Jibāl |

544/1149 |

Sām I b. Husayn I, Bahā’ al-Dīn |

⊘ 544/1149 |

Husayn II b. Husayn I, ‘Alā’ al-Dīn Jahān-sūz |

⊘ 556/1161 |

Muḥammad b. Husayn II, Sayf al-Dīn |

⊘ 558/1163 |

Muḥammad b. Sām I Bahā’ al-Dīn, Abu ’1-Fath Shams al-Dīn, Ghiyāth al-Dīn, supreme sultan in Flrūzkūh |

⊘ (569–99/1173–1203 |

Muḥammad b. Sām I, Shihāb al-Dīn, Mu‘izz al-Dīn, ruler in Ghazna) |

⊘ 599/1203 |

Muḥammad b. Sām I, supreme sultan in Ghūr and India |

⊘ 602/1206 |

Maḥmūd b. Muḥammad Ghiyāth al-Dīn, Ghiyāth al-Dīn |

⊘ (602–11/1206–15 |

Yïldïz Mu‘izzi, Tāj al-Dīn, governor in Ghazna for Maḥmūd Ghiyāth al-Dīn) |

609/1212 |

Sām II b. Maḥmūd, Bahā’ al-Dīn |

610/1213 |

Atsïz b. Husayn II, ‘Alā’ al-Dīn, vassal of the Khwārazm Shāh |

611–12/1214–15 |

Muḥammad b.‘Alī Shujā‘ al-Dīn b. ‘Alī ‘Alā’ al-Dīn b. Husayn I, Diyā’ al-Dīn, ‘Alā’ al-Dīn, vassal of the Khwārazm Shāh |

612/1215 |

Khwdrazmian conquest |

2. The line in Bāmiyān, Tukhāristān and Badakhshān

⊘ 540/1145 |

Mas‘ūd b. Husayn I ‘Izz al-Dīn, Fakhr al-Dīn |

⊘ 558/1163 |

Muḥammad b. Mas‘ūd Fakhr al-Dīn, Shams al-Dīn |

⊘ 588/1192 |

Sām b. Muḥammad Shams al-Din, Bahā’ al-Dīn |

⊘ 602–12/1206–15 |

‘Alī b. Sām Bahā’ al-Dīn, Jalāl al-Dīn |

612/1215 |

Khwārazmian conquest |

The remote, mountainous region of what is now Afghanistan, called Ghūr, was almost wholly terra incognita to the early Islamic geographers, known only as a source of slaves and as the home of a race of bellicose mountaineers who remained pagan until well into the eleventh century. At this time, the Ghaznawids (see above, no. 158) led raids into Ghūr and made the local chiefs of the Shansabānī family their vassals; but in the early twelfth century, the fortunes of the Ghaznawids waned and Seljuq influence now spread through Ghūr, so that ‘Izz al-Dīn Husayn, the first fully historical figure of the family, paid tribute to Sultan Sanjar (see above, no. 91, 1). Attempts by Sultan Bahrām Shāh to reassert Ghaznawid influence led to the Ghūrids’ sack of Ghazna in 545/1150 and the eventual acquisition by them of all the Ghaznawid possessions on the Afghan plateau. In the west, Ghūrid expansionist policies were at first checked by Sanjar, but the collapse of Seljuq power in Khurasan allowed the Sultans to establish an empire, centred on Firūzkūh in Ghūr, stretching almost from the Caspian Sea to northern India, where the Ghaznawid traditions of jihād against the infidels were inherited and kept up.

The joint architects of this achievement were the two brothers Ghiyāth al-Dīn Muḥammad and Mu‘izz al-Dīn Aḥmamad, the former campaigning mainly in the west and the latter in India. Bāmiyān and the lands along the upper Oxus were ruled by another branch of the Ghūrid family. Ghiyāth al-Dīn contested possession of Khurasan with the Khwārazm Shāhs and the latter’s suzerains, the Qara Khitay (see above, no. 89, 4); at one point he invaded Khwārazm itself, and by his death held all Khurasan as far west as Bisṭām.

Yet it seems that the Ghūrids’ resources of manpower were inadequate for holding this empire together, whereas their Khwārazmian adversaries could draw freely on the Inner Asian steppes for troops. After Mu‘izz al-Dīn Aḥammad’s death in 602/1206, the dynasty was rent by internal squabbles. A group of their Turkish soldiers made themselves independent in Ghazna under Tāj al-Dīn Yïldïz, and could not be dislodged by the sultans in Firūzkūh and Bāmiyān. The Khwārazm Shāh Jalāl al-Dīn was therefore able to step in and incorporate the Ghūrid lands into his own empire. But this Khwārazmian domination was only of brief duration, for the whole eastern Islamic world was shortly afterwards overwhelmed by Chingiz Khān’s Mongols (see above, no. 131). Moreover, the Turkish generals of Mu‘izz al-Dīn Muḥammad continued to uphold Ghūrid policies and traditions in northern India, where Quṭb al-Dīn Aybak was installed as ruler in Lahore (Lāhawur) by one of the last Ghūrids (see below, no. 160, 1).

The coinage of the Ghūrids is particularly interesting, in that Mu‘izz al-Dīn Muḥammad minted coins for his Indian lands with the Islamic shahāda and its proclamation of tawhīd, the indivisible unity of God, on one side, and on the other side Sanskrit inscriptions and the likeness of the Hindu goddess Lakśmi.

Justi, 455–6; Lane-Poole, 291–4; Zambaur, 280–1, 284; Album, 39–40.

EI2 ‘Ghūrids’ (C. E. Bosworth); EIr ‘Ghurids’ (C. E. Bosworth).

G. Wiet, in André Maricq and Gaston Wiet, Le minaret de Djam. La découverte de la capital des sultans ghorides (XIIe-XIIIe siècles), Méms DAFA, 16, Paris 1959, 31–54.

C. E. Bosworth, The eastern fringes of the Iranian world: the end of the Ghaznavids and the upsurge of the Ghūrids’, in The Cambridge History of Iran, IV, 157–66.

602–962/1206–1555

Northern India and, at times, the northern Deccan

1. The Mu‘izzī or Shamsī Slave Kings

⊘ 602/1206 |

Aybak, Qutb al-Dīn, Malik of Hindūstān in Lahore for the Ghūrids |

607/1210 |

Ārām Shāh, protégé, dubiously the son, of Aybak, in Lahore |

⊘ 607/1211 |

Iltutmish b. Ham Khān, Shams al-Dīn, sultan in Delhi (Dihlī) |

⊘ 633/1236 |

Fīrūz Shāh I b. Iltutmish, Rukn al-Dīn |

⊘ 634/1236 |

Radiyya Begum b. Iltutmish, Jalālat al-Dīn |

⊘ 637/1240 |

Bahrām Shāh b. Iltutmish, Mu‘izz al-Dln |

⊘ 639/1242 |

Mas‘ūd Shāh b. Fīrūz Shāh I, ‘Alā’ al-Dīn |

⊘ 644/1246 |

Maḥm‘ūd Shāh I b. Nāṣir al-Dīn b. Iltutmish, Nāṣir al-Dīn |

⊘ 664/1266 |

Balban, Ulugh Khān, Ghiyāth al-Dīn, already viceroy [nā‘ib-i mamlakat) in the previous reign |

⊘ 686/1287 |

Kay Qubādh b. Bughra Khān b. Balban, Mu‘izz al-Dīn |

⊘ 689/1290 |

Kayūmarth b. Mu‘izz al-Dīn Kay Qubādh, Shams al-Dīn |

⊘ 689/1290 |

Fīrūz Shāh II Khaljī b. Yughrush, Jalāl al-Dīn |

⊘ 695/1296 |

Ibrāhīm Shāh I Qadïr Khān b. Fīrūz Shāh II, Rukn al-Dīn |

⊘ 695/1296 |

Muḥammad Shāh I ‘Alī Garshāsp b. Mas‘ūd b. Yughrush, ‘Alā’ al-Dīn |

⊘ 715/1316 |

‘Umar Shāh b. Muḥammad Shāh I, Shihāb al-Dīn |

⊘ 716–20/1316–20 |

Mubārak Shāh b. Muḥammad Shāh I, Qutb al-Dīn |

⊘ 720/1320 |

Usurpation of Khusraw Khan Barwāri, Nāsir al-Dīn |

817/1414 |

Khiḍr Khān b. Sulaymān, Rāyat-i A‘lā |

⊘ 824/1421 |

Mubārak Shāh II b. Khiḍr, Mu‘izz al-Dīn |

⊘ 837/1434 |

Muḥammad Shāh IV b. Farld b. Khidr |

⊘ 847–55/1443–51 |

‘Ālam Shāh b. Muḥammad IV, ‘Alā’ al-Dīn, 855–83/1451–78 ruler in Badaon (Badā‘ūn) |

⊘ 855/1451 |

Bahlūl b. Kālā b. Bahrām Lōdī |

⊘ 894/1489 |

Sikandār II Niẓām Khan b. Bahlūl |

⊘ 923–32/1517–26 |

Ibrahīm II b. Sikandar II |

932/1526 |

Mughal victory |

⊘ 947/1540 |

Shīr Shāh Sūr b. Miyān Hasan, Farīd al-Dīn |

⊘ 952/1545 |

Islām Shāh Sur b. Shīr Shāh |

⊘ 961/1554 |

Muḥammad V Mubāriz Khān ‘Ādil Shāh b. Nizām Khān b. Ismā‘īl |

⊘ 961/1554 |

Ibrāhīm Khān III b. Ghāzi b. Ismā‘īl |

⊘ 962/1555 |

Aḥammad Khān Sikandar Shāh III b. Ismā‘ll, in Lahore |

962/1555 |

Mughal conquest |

Islam was first implanted in the lower Indus valley by the Arab governors of the East for the Umayyad caliphs; in 92/711, Sind was conquered by the commander Muḥammad b. al-Qāsim al-Thaqafī. This foothold was retained during the next three centuries, a period in which some of the Muslim communities there were affected by the propaganda of Ismā‘īli Shī‘ī missionaries, who were working intensively on behalf of the Fāṭimids (see above, no. 27) in many parts of the Islamic world, from North Africa to Yemen and the fringes of India. There were also trade contacts between Arabia and the Persian Gulf region and the coastlands of peninsular India, namely Gujarāt, Bombay and the Deccan coasts, just as there had been in classical times; but these sporadic and superficial contacts hardly affected the interior, the overwhelming land mass of the subcontinent.

It was the Turkish Ghaznawids who first brought the full weight of Muslim military power into northern India, overthrowing powerful native dynasties like the Hindūshāhīs of Wayhind, reducing many of the Rājput rulers to tributary status and raiding as far as Somnath and Benares (Baāaras, Varanasi), although most of those rulers who submitted threw off their obligations as soon as the Ghaznawid armies went back. Maḥmūd of Ghazna became an Islamic hero for his attacks on infidel Hindustan, but it is clear that the sultan was not a fanatical zealot, bent on the conversion or extermination of the Hindus - a palpably impossible task – since he used Indian troops in his own armies, and it does not seem that conversion to Islam was a condition of recruitment. The Ghaznawids interest in India was primarily financial, the subcontinent being regarded as an almost inexhaustible reservoir of slaves and treasure; but they did take over the Punjab and make it a permanent base for the extension of Muslim power through northern India, and towards the end of the dynasty’s life Lahore became the sultans’ capital (see above, no. 158).

Hence there existed there a springboard for the Indian conquests of Mu‘izz al-Dln Muḥammad Ghūrī and his Turkish slave generals in the last years of the twelfth century and at the beginning of the thirteenth. After eliminating the last Ghaznawids, he expanded into the Gangetic plain, attacking local Rājput princes, such as the Chāhamāna or Chawhān king of Ajmer and Delhi (Dihlī) and then the Gāhadavāla king of Benares and Kanawj. Among Mu‘izz al-Dīn’s commanders, Qutb al-Dīn Aybak was placed in charge of the Indian conquests during his master’s lifetime, when the sultan was involved in Khurasan and elsewhere. Aybak held on to the Ghūrid conquests in the Punjab and the Ganges-Jumna Do‘āb, and raided as far as Gujarat. Another general, Ikhtiyār al-Dīn Muḥammad Khaljī, penetrated into Bihār and Bengal (Bangāla), making Gawr or Lakhnawatī his base there, and he even attacked Assam (see below, no. 161, 1). It is thus in the period of the Ghūrids and their commanders that the permanent establishment of Islam in northern India begins: long-established Hindu dynasties were humbled and the foundations of various Muslim sultanates laid. On the other hand, throughout the period of the Delhi Sultanate and after, many local Hindu chiefs retained their power, especially away from the main centres of Turco-Afghan military concentration, and Hindus always played important roles in the administrations and armies of Muslim potentates.

When Mu‘izz al-Dīn died in 602/1206, Aybak assumed power in Lahore as Malik or ruler on behalf of the Ghūrid sultan in Fīrūzkūh. Henceforth, Ghazna and the Afghan provinces of the Ghūrid empire were severed from India, falling briefly to the Khwārazm Shāhs and then to the Mongols, but Ghūrid traditions of both civil authority and military organisation lived on in northern India under the succeeding Muslim rulers there. Aybak and his successors up to 689/1290 are often called the Slave Kings, although only three of them, Aybak, Iltutmish and Balban, were of servile origin and all had in any case been manumitted by their masters before achieving power. Nor did these rulers belong to a single line, but to three distinct ones. Under Iltutmish, the real architect of an independent sultanate in Delhi, Sind, formerly in the hands of the Mu‘izzī general Nāṣir al-Dīn Qabācha, was added to the Delhi Sultanate. He also managed to keep the Khwārazmians out of his dominions, but the Mongols overran the Punjab in 639/1241, sacking Lahore and advancing as far as Uch (Uchchh). A succession of weaker sultans brought internal discord, and the unity of the Sultanate was only assured first by the regency and then by the independent rule of the capable Balban, who had been originally one of the famous band of Turkish miltary slaves, the Chihilgān (in the surmise of Dr Peter Jackson, so called because they each themselves commanded forty military slaves) of Iltutmish. Balban continued the work of his master, placing the Sultanate on a firm military and governmental basis by his reforms, and exalting the authority of the sovereign on traditional Perso-Islamic lines. Spiritual links with the rest of the Islamic world were strengthened. Already, Iltutmish had sought investiture from the ‘Abbāsid caliph al-Mustansir;after the demise of the last caliph in Baghdad, al-Musta‘sim, the Mu‘izzī sultans long continued to keep his name on their coins. In this way, one can discern the motif of identification with the wider world of Sunnī Islam and acknowledgement of the moral leadership of the caliphate; such threads run through much of the history of Indian Islam and reflect its struggle to maintain its identity against the pressures of the enveloping Hindu environment. Important, too, as a fertilising influence in the culture of this period were the waves of refugees – scholars and religious figures – from Transoxania and Persia, who fled before the Mongols and found their way to India during such reigns as those of Iltutmish and Balban; and in later times also, such as the reign of Muḥammad II b. Tughluq, infusions of fresh blood continued to revitalise Indo-Muslim religious life and culture.

In 689/1290, the Mu‘izzī sultans were succeeded by the line of Jalāl al-Dln Fīrūz Shāh II Khaljī. The Khalaj were originally a Turkish people (or perhaps a Turkicised people of a different ethnic origin) inhabiting eastern Afghanistan; it seems likely that the later Ghilzay Afghans were descended from them. During the reign of Mu‘izz al-Dīn Muḥammad Ghūrī, the Khalaj had played a prominent part in the invasions of India, with Ikhtiyār al-Dīn Muḥammad KhaljI especially notable for bringing Islam to eastern India and Bengal (see above). The pressing task for Fīrūz Shāh II was to keep out the Mongols; it was, nevertheless, during his reign that large numbers of Mongols converted to Islam were allowed to settle in the Delhi area. The outstanding figure of the dynasty is undeniably ‘Alā’ al-Dīn Muḥammad Shāh I, who considered himself a second Alexander the Great and had grandiose dreams of assembling a vast empire. In actuality, he had to cope with the threat from the Chaghatayid Mongols, who several times raided as far as Delhi, but his ambitions found their main outlet in South India, the rich area south of the Vindhya Mountains as yet untouched by Muslim arms. An attack in 695/1296 on Deogir or Devagiri in the north-western Deccan, capital of the Yādavas, brought him the wealth which he afterwards used to win the sultanate for himself, and when he was firmly established on the throne he sent further armies to the southernmost tip of the Deccan. ‘Alā’ al-Din Muḥammad continued to use the traditional designation of Nāṣir Amīr al-Mu‘minīn ‘Helper of the Commander of the Faithful’; the first and last Indo-Muslim ruler to appropriate for himself the caliphal title of Amīr al-Mu‘minīn was his son Qutb al-Dīn Mubarak Shāh I.

The Khaljī line collapsed when Khusraw Khān, a Gujarātī convert from Hinduism and favourite of the last Khaljī sultan, possibly apostasised from Islam and certainly briefly usurped the throne in Delhi. Muslim control was reestablished by the Turco-Indian Tughluq Shāh I and his son Muḥammad Shāh II, who in 720/1320 inaugurated the reign of the Tughluqid sultans. The first did much to restore the stability of the Sultanate and to reimpose Muslim control over the Deccan. Muḥammad Shāh II is an enigmatic figure: a skilful general whose behaviour was nevertheless often erratic and his judgement poor. Increases of taxation necessary to run the sultanate and to finance warfare made him unpopular, but his decision of 727/1327 to transfer the capital from Delhi southwards to Deoglr, now renamed Dawlatābād, proved disastrous. On the other hand, he did successfully repel a Chaghatayid invasion from Transoxania, but his project for taking advantage of Chaghatayid weakness, perhaps in concert with the II Khānids, and for invading Central Asia via the Pamirs (if such really was his intention, the sources being vague over this), was a chimera. Muḥammad Shāh II had diplomatic relations with the Islamic world outside India, including with the Mamlūks of Egypt (see above, no. 31), and sought investiture from the ‘Abbāsid puppet caliph in Cairo (see above, no. 3, 3). The diversion of energies to unrealistic military projects on the northern frontiers of the subcontinent led to a weakening of the Tughluqid hold over the Deccan. An independent Muslim sultanate arose in Ma‘bar or Madura in the extreme south (see below, no. 166), and in 748/1347 the Bahmanid kingdom of the central Deccan was founded by Alā’ al-Dīn Ḥasan Bahman Shāh (see below, no. 167, 1). Later, Fīrūz Shāh III restored sultanal authority in Sind and Bengal, but made no attempt to touch the Deccan. The last Tughluqids were weaklings, so that Tīmūr was able to invade India in 801/1398–9 and wreak great devastation; as a result, the political unity of the Sultanate was dissolved, and various Muslim leaders seized independent power in the provinces.

For rather less than forty years, power was in the hands of the line of Khiḍr Khān, former governor of Multan (Multān), first for the last Tughluqids and then for Tīmūr. Khidr Khan ruled in the names of Tīmūr and his son Shāh Rukh, contenting himself with the title Rāyat-i A‘la ‘Exalted Banner’; because of their claim to a fictitious descent from the Prophet, his line acquired the name of Sayyids. The effective authority of the Sayyids was reduced to a small area round Delhi, and with their initial dependence on the Timūrids they were unpopular with the Turkish and Afghan military classes in the capital. In 855/1451, their line was replaced by that of Bahlūl Khān, a chief of the Afghan tribe of the Lōdīs and formerly governor of Sirhind and Lahore. Bahlūl was the equal in vigour of the great Tughluqī sultans, and did much to restore Muslim prestige in India; the authority of Delhi was imposed over much of Central India, and the Sharqī rulers of Jawnpur (see below, no. 164) overthrown in 881/1477. His son Sikandar II conducted operations against the Rājput princes with some success, and moved his capital to Agra as being a better base for these attacks. However, the last Lōdī, Ibrahīm II, alienated many of his nobles and commanders, and certain of these invited the Chaghatayid Mughal Bābur, then in Kabul, to intervene.

Bābur’s victory at the first battle of Pānīpat, to the north of Delhi, in 932/1526 resulted in Ibrahīm’s death, the end of the Lōdī line and the first appearance of the dynasty of the Mughals in India. But this did not mean the permanent establishment yet of Bābur’s line, for his son Humāyūn’ reign was interrupted by the fifteen-year restoration of Afghan rule in India by Shir Shāh Sur. Operating from Bihar, Shir Shāh defeated Humāyūn at Kanawj, thus negating all Bābur’s work. As well as being a fine general, Shir Shāh introduced important fiscal and land reforms. But for his premature death, a strong Afghan sultanate might have been implanted in India; discouraging Humāyūn from trying his fortunes once more; as it was, the weakness of Shīr Shāh’s ephemeral successors facilitated a successful Mughal revanche.

Justi, 464–5; Lane-Poole, 295–303; Sachau, 32 no. 87 (Khaljīs), 33 no. 93 (Sūrīs); Zambaur, 285–8.

EI2 ‘Dihlī Sultanate’ (P. Hardy), ‘Hind. IV. History’ (J. Burton-Page); ‘Khaldjīs’ (S. Moinul Haq), ‘Lōdīs’ (S. M. Imamuddin), ‘Sayyids’ (K. A. Nizami), ‘Sūrīs’ (I. H. Siddiqi).

H. Nelson Wright, The Coinage and Metrology of the Sulṭāns ofDehlī Incorporating a Catalogue of the Coins in the Author’s Cabinet now in the Dehlī Museum, Delhi 1936.

K. S. Lal, History of the Khaljis A.D. 1290–1320, revised edn, New Delhi 1980.

(Agha) Mahdi Husain, Tughluq Dynasty, Calcutta 1963.

Abd ul-Halim, History of the Lodi Sultans of Delhi and Agra, Dacca 1961.

I. H. Siddiqi, History of Sher Shah Sur, Aligarh 1971.

R. C. Majumdar, A. D. Pusalker and A. K. Majumdar (eds), The History and Culture of the Indian People. V. The Struggle for Empire, Bombay 1957, chs 4–5.

eidem (eds), VI. The Delhi Sultanate, Bombay 1960, chs 2-9, 14.

Majumdar (ed.), VII. The Mughul Empire, Bombay 1974, ch. 4.

Mohammad Habib and Khaliq Aḥammad Nizami (eds), A Comprehensive History of India. V. The Delhi Sultanat (A.D. 1206–1526), Delhi 1970, chs 2-7.

161

THE GOVERNORS AND SULTANS OF BENGAL

594–984/1198–1576

Bengal and Bihār

1. The governors for the Delhi Sultans, often ruling as independent sovereigns

⊘ 594/1198 |

Muḥammad Bakhtiyār Khaljī, Ikhtiyār al-Dīn, conqueror of Bihār and Bengal |

603/1206 |

‘Alī Mardān, first term of office |

603/1207 |

Muḥammad Shirān Khān, ‘Izz al-Din |

⊘ 604/1208 |

‘Iwad, Husām al-Dīn, first term of office |

607/1210 |

‘Alī Mardān, ruling title ‘Alā’ al-Dīn, second term of office |

⊘ 610/1213 |

‘Iwad, Husām al-Dīn, ruling title Ghiyāth al-Dīn |

⊘ 624/1227 |

Maḥmūd b. Iltutmish, Nāsir al-Din, Malik al-Sharq |

626/1229 |

Bilge Khan b. Mawdūd, Ikhtiyār al-Dīn, ruled as Dawlat Shāh |

629/1232 |

Mas‘ūd Jānī, ‘Alā’ al-Dīn, first term of office |

⊘ 630/1233 |

Aybak Khitā‘ī, Sayf al-Dīn |

633/1236 |

A‘or Khan Aybak |

633/1236 |

Toghrïl Toghan Khān, ‘Izz al-Din |

642/1244 |

Temür Qirān Khān, Qamar al-Dīn |

645/1247 |

Mas‘ūd Jānī b. Mas‘ūd Jānī, Jalāl al-Dīn, first term of office |

⊘ 649/1251 |

Yuzbak, Ikhtiyār al-Dīn, with the ruling title Abu ‘1-Muzaffar Ghiyāth al-Dīn |

655/1257 |

Balban Yuzbakī, ‘Izz al-Dīn, first term of office |

657/1259 |

Mas‘ūd Jānī b. Mas‘ūd Jānī, second term of office |

657/1259 |

Balban Yuzbakī, second term of office |

657/1259 |

Muḥammad Arslan Khān Sanjar, Tāj al-Dīn |

663/1265 |

Tātār Khān b. Muḥammad Arslan |

666/1268 |

Shīr Khān |

670–80/1272–81 |

Toghrïl, with the ruling title Mughlth al-Dīn |

2. The governors, and then independent rulers, of Balban’s line

| ⊘ 740/1339 | Ilyās Shāh, Shams al-Dīn, originally in Sātgā‘on |

| ⊘ 759/1358 | Sikandar Shāh I b. Ilyās Shāh |

| ⊘ 792/1390 | A‘zam Shāh b. Sikandar Shāh I, Ghiyāth al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 813/1410 | Hamza Shāh b. A‘zam Shāh, Sayf al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 815/1412 | Bāyazid Shāh b. A‘zam Shāh, Sayf al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 817/1414 | Fīrūz Shāh b. Bāyazīd Shāh |

4. The line of Rājā Ganeśa (Ganesh)

| 817/1414 | Jadu, son of Rājā Ganeśa, first reign under the regency of his father |

| ⊘ 819/1416 | Rājā Ganeśa, as Danūj Mardan Deva |

| ⊘ 821/1418 | Mahendra Deva, son of Rājā Ganeśa |

| ⊘ 821/1418 | Jadu, now Muḥammad Shāh, Jalāl al-Din, second reign |

| ⊘ 836–40/1433–7 | Aḥammad Shāh b. Muḥammad Shāh |

5. The line of Ilyās Shāh restored

| ⊘ 841/1437 | Maḥmūd Shāh, descendant of Ilyās Shāh, Abu ‘l-Muẓaffar Nāṣir al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 864/1460 | Barbak Shāh b. Maḥmūd Shāh, Rukn al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 879/1474 | Yūsuf Shāh b. Barbak Shāh, Shams al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 886/1481 | Sikandar Shāh II (b) b. Yūsuf Shāh |

| ⊘ 886–92/1481–7 | Husayn Fath Shāh b. Maḥmūd Shāh, Jalāl al-Dīn |

6. The domination of the Habashis

| ⊘ 892/1487 | Sulṭān Shāhzāda Barbak Shāh |

| ⊘ 892/1487 | ‘Andil, ruled as Aḥammad Firūz Shāh Sayf al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 895/1490 | Maḥmūd Shāh (?) b. Aḥammad Firūz Shāh, Nāṣir al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 896–8/1491–3 | Dīwāna, ruled as Muẓaffar Shams al-Dīn |

7. The line of Sayyid Husayn Shāh

| ⊘ 898/1493 | Sayyid Husayn Shāh, ‘Alā’ al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 925/1519 | Nusrat Shāh b. Husayn Shāh, Nāṣir al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 939/1533 | Fīrūz Shāh b. Husayn Shāh, ‘Alā’ al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 940–4/1534–7 | Maḥmūd Shāh b. Husayn Shāh, Ghiyāth al-Dīn |

| 944/1537 | Shir Shāh Sūr |

| (947/1540 | Khiḍr Khān, governor for Shīr Shāh) |

| ⊘ 952/1545 | Muḥammad Khān Sur, Shams al-Dīn, independent in 960/1553 |

| ⊘ 962/1555 | Khḍr Khān Bahadur Shāh b. Muḥammad Khān Sūr, Ghiyāth al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 968–71/1561–4 | Jalāl Shāh b. Muḥammad Khān Sūr, Abu’ l-Muzaffar Ghiyāth al-Dīn |

| 971 /1564 | Sulaymān Kararānī |

| 980/1572 | Bāyazīd Kararāni b. Sulaymān |

| ⊘ 980–4/1572–6 | Dāwūd Kararānī b. Sulaymān |

| 984/1576 | Mughal conquest |

The conquest of the easternmost provinces of India, Bihār and Bengal, was the achievement of Mu‘izz al-Dīn Muḥammad Ghūrī’s commander Muḥammad Bakhtiyār Khaljī, who raided as far as the mountain barrier beyond which lay Tibet, and founded a capital at Lakhnawati or Gawr in the frontier zone between Bihar and Bengal. Subsequently, governors of the Delhi Sultans made other towns into centres of government, Sātgā‘on in south-western Bengal and Sonārgā‘on in the east (near modern Dacca or D́hākā), until Ilyās Shāh integrated all these into the independent Bengal sultanate. Because of the province’s richness and its distance from Delhi, Bengal had always been difficult for the Sultans to administer, and central government control was often sporadic. In the first half of the fourteenth century, Muslim troops penetrated across the Brahmaputra into Sylhet (Silhet) and Assam and to Chittagong on the Bay of Bengal, and it was from this time that a steady process of conversion to Islam of low-caste Hindus began, leading to the eventual preponderance of Muslims over much of Bengal.

In the time of Muḥammad b. Tughluq, Bengal came to be ruled by Fakhr al-Dīn Mubārak Shāh at Sonārgā‘on in the east and ‘Alā’ al-Dīn ‘All at Lakhnawatī in the west, and henceforth for over two centuries independent sultans controlled Bengal. Under the Ilyāsids, the Islamic arts and sciences flourished, and commerce in Bengal’s textiles and foodstuffs was encouraged. In the first decade of the fifteenth century, Ghiyāth al-Dīn A‘zam Shāh renewed old diplomatic and cultural links with China, and the growth of the port of Chittagong probably reflects increased trade with the lands farther east. The reign of the Ilyāsids was interrupted for over twenty years by the seizure of power by Rājā Ganeśa, a local Hindu landlord of Bengal; his son became a Muslim and ruled as Jalāl al-Dīn Aḥammad, and despite their Hindu origins the family was able to rule with some Muslim support. Under the restored Ilyāsids, the influence of Habashī or black palace guards grew, until in 892/1487 their commander, the eunuch Sulṣān Shāhzāda, murdered the last Ilyāsid and seized power for himself.

Order was eventually restored by Sayyid ‘Alā’ al-Din Husayn Shāh, whose enlightened rule came opportunely after the chaos of the Habashi period. Bihār was annexed; asylum given to the Sharqī ruler of Jawnpur, dispossessed by the Lōdīs of Delhi (see below, no. 164, and above, no. 160, 5), and the Jawnpur troops added to the Bengal army. The growth of a vernacular Bengali literature was a process continuing during these centuries, and royal encouragement is seen in Nuṣrat Shāh b. Sayyid Ḥusayn’s patronage of a Bengali translation of the Mahābhārata. The line of Sayyid Ḥusayn was ended by the meteoric rise of the Afghan chief Shīr Shāh Sūr, who took over Bengal and used it as a base from which to eject the Mughal Humāyūn from India (see above, no. 160, 6, and below, no. 175). But once the Mughals were firmly re-established in Lahore and Delhi and the Afghans defeated, Mughal influence began to be felt in Bengal. Sulaymān Kararānī, the former governor of southern Bihār, acknowledged the suzerainty of Akbar, and in 984/1576 Bengal was overrun and incorporated in the Mughal empire, becoming one of its ṣūbas or provinces.

Lane-Poole, 305–8; Zambaur, 286, 289.

EI2 ‘Bangāla’ (A. H. Dani); ‘Hind. IV. History’ (J. Burton-Page).

R. C. Majumdar et al. (eds), The History and Culture of the Indian People. VI. The Delhi Sultanate, ch. 10 E.

M. Habib and K. A. Nizami (eds), A Comprehensive History of India. V. The Delhi Sultanat (A.D. 1206–1526), chs 2 iv and 19.

Sir Jadu-Nath Sarkar, The History of Bengal Muslim Period 1200–1757, Patna 1973, chs 2-7.

Mohammad Yusuf Siddiq, Arabian and Persian Texts of the Islamic Inscriptions of Bengal, Watertown MA 1991.

idem, al-Nuqūsh al-‘arabiyya fī ’l-Banghdl wa-atharuhd al-ḥaḍarī, Beirut 1996.

739–996/1339–1588

| 739/1339 | Shāh Mīr Swātī, Shāms al-Dīn |

| 743/1342 | Jamshīd b. Shāh Mīr |

| 745/1344 | ‘Alī Shīr b. Shāh Mīr, ‘Alā’ al-Dīn |

| 755/1354 | Shirāshāmak b. ‘Alī Shīr, Shihāb al-Dīn |

| 775/1374 | Hindal b. ‘Alī Shīr, Quṭb al-Dīn |

| 792/1390 | Sikandar b. Hindal, But-shikan, until 795/1393 under the regency of his mother Sura |

| ⊘ 813/1410 | ‘Alī Mīr Khān b. Sikandar, ruled as ‘Alī Shāh |

| ⊘ 823/1420 | Shāhī Khān b. Sikandar, ruled as Sultan Zayn al-‘Ābidīn, called Bud Shāh ‘Great King’ |

| ⊘ 875/1470 | Ḥājji Khān b. Zayn al-‘Ābidīn, ruled as Haydar Shāh |

| ⊘ 876/1472 | Ḥasan Shāh b. Ḥaydar |

| 889/1484 | Muḥammad Shāh b. Ḥasan, first reign |

| ⊘ 892/1487 | Fatḥ Shāh b. Ad‘ham Khān b. Zayn al-‘Ābidīn, first reign |

| ⊘ 904/1499 | Muḥammad b. Ḥasan, second reign |

| 910/1505 | Fatḥ Shāh b. Ad’ham Khān, second reign |

| 922/1516 | Muḥammad Shāh b. Ḥasan, third reign |

| 934/1528 | Ibrāhīm Shāh b. Muḥammad, first reign |

| 935/1529 | Nāzūk or Nadir Shāh b. Fatḥ |

| ⊘ 936/1530 | Muḥammad Shāh b. Ḥasan, fourth reign |

| 943/1537 | Shams al-Dīn b. Muḥammad |

| 947/1540 | Ismā‘īl Shāh b. Muḥammad, first reign |

| 947–58/2 540–51 | Mīrzd Ḥayāar Dughlat, governor for the Mughal Humdyūn |

| 958/1551 | Nāzūk Shāh b. Ibrāhīm, second reign |

| ⊘ 959/1552 | Ibrāhīm Shāh b. Muḥammad, second reign |

| ⊘ 962/1555 | Ismā‘īl Shāh b. Muḥammad, second reign |

| 964–8/1557–61 | Habib Shāh b. Ismā‘ll, deposed by Ghāzi Khān Chak |

2. The line of Ghāzi Shāh Chak

| 968/1561 | Ghāzī Khān Chak, ruled as Muḥammad Nāsir al-Dīn |

| 971/1563 | Ḥusayn Shāh, Nāṣir al-Dīn, brother of Muḥammad Ghāzī |

| 978/1570 | Muḥammad ‘Alī Shāh, Ẓahīr al-Dīn, brother of Muḥammad Ghāzī and Ḥusayn |

| ⊘ 987/1579 | Yūsuf Shāh b. ‘Alī, Nāṣir al-Dīn, d. in Bīhar 1000/1592 |

| 994–6/1586–8 | Ya‘qūb Shāhb. Yūsuf, d. 1001/1593 |

| 996/1588 | Definitive Mughal conquest |

Because of its geographical position, separated by high mountain barriers from the plains of northern India, Kashmīr was long sheltered from Muslim raids. It remained under its own dynasty of Hindu rulers long after most of northern India had passed under Muslim control. Maḥmūd of Ghazna (see above, no. 158) made two attempts to invade Kashmīr from the south, but was held up on both occasions by the fortress of Lohkot. However, Muslim Turkish mercenaries [Turuśka) began to be employed by the Hindu kings of Kashmīr, and the process of Islamisation, which has given the province today an overwhelmingly Muslim population, must have tentatively begun.

In 735/1335, the throne there was seized by Shāh Mīr Swātī, a Muslim adventurer who was probably of Pathan origin and who had been minister to Rājā Sinha Deva. The régime of Shāms al-Dīn (this being the honorific which Shāh Mīr adopted) was tolerant and mild towards the majority Hindus, but his grandson Sikandar was a Muslim zealot who patronised the ‘ulamā’ and scholars and who persecuted the Hindus, destroying their temples and earning for himself the epithet But-shikan Idol-breaker’. Already before this, the Kubrawī ṣūfī saint ‘All Hamadhānī and many Sayyids had arrived in Kashmīr, and during Sikandar’s reign the group of Bayhaqī Sayyids, who were to play a prominent role in the religious and intellectual life of the province, migrated from Delhi to Kashmīr. However, his son Zayn al-‘Ābidīn reversed this rigorist policy, and his long and enlightened reign was something of a Golden Age for Kashmīr; under his patronage, the Mahābhārata and Kalhana’s twelfth-century metrical chronicle of Kashmīr, the Rājataranginī, were translated into Persian. Unfortunately, his descendants were lesser men, and much internecine strife now followed; various provincial chiefs took advantage of the mountainous and difficult terrain and established a virtual independence. In particular, the influence of the powerful Chak tribe, originally immigrants from Dardistān, grew, its leaders serving as ministers and commanders for the last feeble fainéant rulers of Shāh Mīr’s line. The Mughal prince Ḥaydar Dughlat invaded Kashmīr in 947/1540, and ruled in Srinagar for ten years on behalf of his kinsman Humāyūn, until he was killed in an uprising. The Chak family was now again in the ascendant, and after 968/1561 they ruled as sovereigns themselves, assuming the title Pīdishāh ’Monarch’ in imitation of the Mughals; their religious inclinations were towards Shī‘ism. However, the last two Chaks had to rule as vassals of Akbar until they were finally deposed and Kashmīr fully incorporated into the Mughal empire.

Justi, 478; Sachau, 32–3 nos 89 and 90; Zambaur, 293–4.

EI2 ‘Hind. IV. History’ (J. Burton-Page), ‘Kashmīr. I. Before 1947’ (Mohibbul Ḥasan), Suppl. ‘Caks’ (idem).

Sir T. W. Haig, ‘The chronology and genealogy of the Aḥmadan Kings of Kashmir’, JKAS (1918), 451–68.

Mohibbul Ḥasan, Kashmir under the Sultans, Calcutta 1959.

R. C. Majumdar et al. (eds), The History and Culture of the Indian People. VI. The Delhi Sultanate, ch. 13 C.

M. Habib and K. A. Nizami (eds), A Comprehensive History of India. V. The Delhi Sultanat (A.D. 1206–1526), ch. 9.

806–980/1403–1573

Western India

| (793/1391 | Ẓafar Khān b. Wajīh al-Mulk, governor with the title of Muẓaffar Khān) |

| 806/1403 | Tātār Khān b. Muẓaffar, proclaimed himself Sultan with the title of Muḥammad Shāh (I) |

| 810/1407 | Muẓaffar Khān, proclaimed Sultan with the title of Muẓaffar Shāh (I) |

| ⊘ 814/1411 | Aḥmad Shāh I b. Muḥammad b. Muẓaffar, Shihāb al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 846/1442 | Muḥammad Shāh II Karīm b. Aḥmad |

| ⊘ 855/1451 | Jalāl Khān b. Muḥammad II, succeeded as Aḥmad Shāh (II), Quṭb al-Dīn |

| 862/1458 | Dāwūd Khān b. Aḥmad I |

| ⊘ 862/1458 | Fatḥ Khān b. Muḥammad II, succeeded as Maḥmūd Shāh I, Begrā, Sayf al-Dīn |

| 0917/1511 | Khalīl Khān b. Maḥmūd, succeeded as Muẓaffar Shāh II |

| 932/1526 | Sikandar b. Muẓaffar II |

| 932/1526 | Nāṣir Khān b. Muẓaffar II, succeeded as Maḥmūd Shāh (II) |

| ⊘ 932/1526 | Bahādur Shāh b. Muẓaffar II, first reign |

| 942–2/2535–6 | Mughal occupation |

| 942–3/1536–7 | Bahādur Shāh, second reign |

| ⊘ 943/1537 | Maḥmūd Shāh III b. Latif Khān b. Muẓaffar II |

| ⊘ 962/1554 | Aḥmad Shāh III, descendant of Aḥmad I, Raḍi ‘l-Mulk |

| ⊘ 968/1561 | Muẓaffar Shāh III b. ? Maḥmūd III, first reign |

| 980/1573 | Mughal conquest |

| ⊘ (991/1583 | Muẓaffar Shāh III, brief second reign, d. 1001/1593) |

| 991/1583 | Definitive Mughal conquest |

The mediaeval province of Gujarāt on the western coastland of India comprised both a mainland section lying to the east of the Rann of Cutch (Kachchh) and also the peninsula of Kathiawar. Because of its commercial and maritime connections with the other shores of the Indian Ocean, Gujarāt was a particularly rich province; but although Maḥmūd of Ghazna had marched through it en route for Somnath (see above, no. 158), permanent Muslim conquest was quite long delayed. Only in 697/1298 did the troops of ‘Alā’ al-Dīn Muḥammad Khalji defeat the main local Hindu dynasty, the Vāghelās of Anahilwāra. During the fourteenth century, Gujarāt was ruled by governors appointed by the Delhi Sultans, until in 793/1391 the Tughluqid Muḥammad III sent out Ẓafar Khān. As the Tughluqids fell into palpable decline, Ẓafar Khān became in effect independent, and his son and he claimed the insignia of royalty and the title of Shāh. The new sultanate was consolidated by the founder’s grandson Aḥmad I, much of whose reign was occupied by warfare against the Hindu Rājās of Gujarāt and Rājputānā and against his fellow-Muslim sovereigns of Mālwa, Khāndesh and the Deccan. It was he who built for himself the new capital of Aḥmadābād, which replaced that of Anahilwāra. The fifty-five years of Maḥmūd Begŕā’s reign (862–917/1458–1511) were the greatest in the history of the Gujarāt Sultanate. Campaigns against the Hindu princes led, among other things, to the capture of the fortress of Chāmpānēr, now renamed Maḥmūdābād and made the sultan’s capital; indeed, during his reign the Sultanate attained its greatest extent before the subsequent annexation of Mālwa (see below, no. 165)

A new factor in the politics of western and southern India appeared before the end of Maḥmūd’s reign, namely the Portuguese. After Vasco da Gama appeared at Calicut (Kalikat) in 1498, the Portuguese began to divert much of the Indian Ocean commerce into their own hands, thus bypassing the traders of Egypt and Gujarāt. Hence in 914/1508 Maḥmūd allied with the Mamlūk Sultan Qānṣūḥ al-Ghawrī (see above, no. 31, 2), but despite the initial Muslim naval victory near Bombay over Dom Lourenço de Almeida, the Portuguese captured Goa from the neighbouring ‘Ādil Shāhīs of Bījapur (see below, no. 170) and Maḥmūd was compelled to make peace. The last great sultan of Gujarāt was Maḥmūd’s grandson Bahādur Shāh, who assumed the offensive against the Hindus and also conquered Mālwa, only to lose it and part of his own dominions to the Mughal Humāyūn. The menace from the Portuguese revived, and despite the grant to them of Diu (Dīw) they treacherously killed Bahādur Shāh in 943/1537. The unity of Gujarāt now crumbled; dynastic quarrels broke out, and the kingdom began to split up among various nobles. In despair, the Mughals were called in so that Akbar took over Gujarāt in 980/1572–3 and made it into a province of his empire, although the last sultan of Gujarāt, Muẓaffar III, made several attempts at a revanche up to his death in 1001/1593.

Justi, 476; Lane-Poole, 312–14; Zambaur, 296.

EI2 ‘Gudijārāt’ (J. Burton-Page), ‘Hind. IV. History’ (idem).

G. P. Taylor, ‘The coins of the Gujarāt saltanat’, JBBRAS, 21 (1903), 278–338, with a genealogical table at p. 308.

M. S. Commissariat, History of Gujarat. Including a Survey of its Chief Architectural Monuments and Inscriptions. I. From A.D. 1297–8 to A.D. 1573, Bombay etc. 1938, with a chronological table and chronological list of rulers at pp. 564–5.

R. C. Majumdar et al. (eds), The History and Culture of the Indian People. VI. The Delhi Sultanate, ch. 10 A.

M. Habib and K. A. Nizami (eds), A Comprehensive History of India. V. The Delhi Sultanat (A.D. 1206–1506), ch. 11.

164

THE SHARQĪ SULTANS OF JAWNPUR

796–888/1394–1483

East-central northern India

| 796/1394 | Malik Sarwar, Khwāja-yi Jahān |

| ⊘ 802/1399 | Malik Qaranful Mubārak Shāh, adopted son of Malik Sarwar |

| ⊘ 804/1401 | Ibrāhīm, Shams al-Dīn, brother of Mubārak Shāh |

| ⊘ 844/1440 | Maḥmūd Shāh b. Ibrāhīm |

| ⊘ 862/1458 | Bhikan Khan b. Maḥmūd Shāh, ruled as Muḥammad Shāh |

| ⊘ 862–88/1458–83 | Ḥusayn Shāh b. Maḥmūd Shāh, d. 911/1505 |

| 888/1483 | Conquest by the Delhi Sultans |

Jawnpur lies on the Gumtī river to the north of Benares, between what were later the provinces of Bihār and Oudh (Awadh), hence in what is now the eastern part of Uttar Pradesh State, and is traditionally said to have been founded in 762/1359 by the Tughluqid Fīrūz Shāh III and named after his cousin and patron Muḥammad b. Tughluq, one of whose names was Jawna (< Yāvana ‘foreigner’) Shāh. In the fifteenth century it became the centre of a powerful Muslim state, situated between the Sultanates of Delhi and Bengal, and the Sultans of Jawnpur played a significant role in developing the Islamic culture of the region; Jawnpur, indeed, became known as ‘the Shīrāz of the East’.

The dynasty was founded by one Malik Sarwar, the eunuch slave minister of the last Tughluqid Maḥmūd Shāh II, who conquered Oudh on behalf of his master in 796/1394 and then remained there as virtual ruler, persuading the sultan to grant him the title of Malik al-Sharq ‘King of the East’, whence the name of the dynasty. Helped by the chaos which followed Tīmūr’s invasion of India, his adopted son Mubārak Shāh behaved as a fully independent ruler, minting his own coins and having the bidding prayers in the khuṭba or Friday sermon made in his own name alone. His brother Ibrāhīm was the greatest of the Sharqīs, and during his reign of nearly forty years the dynasty reached a peak of affluence and power. A particularly fine school of Indo-Muslim architecture developed in Jawnpur, and, being himself a man of culture, Ibrāhīm encouraged scholars and literary men at his court. His successors were drawn into warfare with the Lōdī Sultans of Delhi and raided Gwalior (Gwāliyār), but were most successful in attacking Orissa (Uŕīsā). According to Muslim chronicles, Jawnpur had at this time one of the largest armies in India. The last Sharqī sultan, Ḥusayn Shāh, reached the gates of Delhi on one occasion, but Bahlūl and Sikandar Lōdī were in the end too much for him. Sikandar defeated Ḥusayn, who fled to Bengal and lived out his life in a small district granted to him by the Bengal Sultan ‘Alā’ al-Dīn Ḥusayn Shāh (see above, no. 161, 7). Jawnpur thus passed under the control of the Lōdl Sultan, who deliberately destroyed the city’s fine buildings left by the Sharqīs. Ḥusayn Shāh’s descendants had irredentist hopes of regaining the kingdom, hopes which the Mughals were not disposed to satisfy, although Bābur and Humāyūn did permit them to style themselves sultans.

Lane-Poole, 309; Zambaur, 292.

EI1 ‘Djawnpur’ (J. Burton-Page), ‘Hind. IV. History’ (idem), ‘Sharkīs’ (K. A. Nizami).

H. M. Whittell, ‘The coinage of the Sharqī Kings of Jaunpū’, JASB, new series, 18 (1922), Numismatic Suppl., pp. N.10-N.35.

M. M. Saeed, The Sharqi Sultanate of Jaunpur: A Political and Cultural History, Karachi 1972, with Appx A on coinage at pp. 293–301 and a genealogical table as Appx C at pp. 306–7.

R. C. Majumdar et al. (eds), The History and Culture of the Indian People. VI. The Delhi Sultanate, ch. 10 D.

M. Habib and K. A. Nizami (eds), A Comprehensive History of India. V. The Delhi Sultanat (A.D. 1206–1506), ch. 8.

165

THE SULTANS AND RULERS OF MĀLWA

804–969/1402–1562

Central India

| (793/1391 | Dilāwar Khān Ḥasan Ghūrī, governor for the Delhi Sultans) |

| 804/1402 | Dilāwar Khān, as ‘Amīd Shāh Dāwūd |

| ⊘ 809/1406 | Alp Khān b. Dilāwar, succeeded as Hūshang Shāh |

| 838/1435 | Ghāznī Khān b. Alp, succeeded as Muḥammad Shāh Ghūrī |

| 839/1436 | Mas‘ūd Khān b. Muḥmmad |

| ⊘ 839/1436 | Maḥmūd Khān, succeeded as Maḥmūd Shāh (I) Khaljī |

| ⊘ 873/1469 | Ghiyāth al-Dīn Shāh b. Maḥmūd |

| ⊘ 906–16/1501–10 | Nāṣir al-Dīn Shāh b. Ghiyāth al-Dīn, ‘Abd al-Qādir |

| ⊘ 917–37/1511–31 | Maḥmūd Shāh II b. Nāsir al-Dīn, after 924/1518 as a vassal of the Sultans of Gujarāt |

| 937–41/1531–5 | Occupation by Gujarāt |

3. Various governors and independent rulers

| 939/1533 | Mallū Khān, governor for Gujarāt in 939/1533 and then independent as Qādir Shāh |

| 949/1542 | Shajā‘at Khān, governor for the Delhi Sultan Shīr Shāh Sūr, first period of power |

| 952/1545 | ‘Īsā Khān, governor for Islām Shāh Sūr |

| 961/1554 | Shajā‘at Khān, governor for Muḥammad ‘Ādil Shāh Sūr, second period of power, independent in 962/1555 |

| ⊘ 962–9/1555–62 | Miyān Bāyazīd b. Shajā‘at Khān, Bāz Bahādur |

| 969/1562 | Definitive Mughal conquest |

Mediaeval Indian Mālwa was the plateau region of western Central India, which formed a triangle with the Vindhya range as its base, hence it corresponded to what is now largely within the westernmost part of Madhya Pradesh State. Muslim rule was only established there after long and bloody struggles with the local Rājput rulers of Chitōr and Ujjain. In 705/1305, the Delhi Sultan ‘Alā’ al-Dīn Khaljī despatched an army which subjugated Mālwa, and thereafter governors were sent out to the region from Delhi. The Afghan governor Dilāwar Khān Ghūrī sheltered the refugee Tughluqid Maḥmūd Shāh II during Tīmūr’s invasion of northern India in 801 /1398–9, but the shock to the fabric of the Delhi Sultanate at this time permitted Dilāwar Khān shortly afterwards to declare his independence and assume the insignia of royalty. The circumstances of Mālwa’s achievement of independence thus parallel those of the rise of the Sharqīs in Jawnpur (see above, no. 164). The Mālwa Sultans made their capital the inaccessible and heavily-defended fortress of Mānd́ū, and adorned the city which grew up there with many splendid buildings.

At one point, the Ghūrī sultans undertook a raid as far as Hindu Orissa, but most of their military activity was against nearby Rājput chiefs and neighbouring Muslim rulers, including the Sharqis, the Gujarāt Sultans, the Sayyid Sultans of Delhi and the Bahmanids of the Deccan; in this warfare against Muslim rivals, they did not hesitate to ally with Hindu princes. In 839/1436, the chief minister Maḥmūd Khān took over the throne in Mālwa (the last Ghūrī sultan fleeing to Gujarāt) and began the line of the Khaljīs there. Maḥmūd I Khaljī was the greatest of the Mālwa Sultans, and despite several setbacks in his campaigns against the Rājputs of Chitōr and the Bahmanids he expanded his territories considerably. His fame spread beyond the subcontinent; he received a formal investiture of power from the fainéant ‘Abbāsid caliph in Cairo al-Mustanjid (see above, no. 3, 3), and embassies were exchanged with the Tīmūrid sultan in Herat, Abū Sa‘id (see above, no. 144, 1). But during the reign of his great-grandson Maḥmūd II, there arose an ascendancy of Rājput ministers and courtiers in the state, such as that of the sultan’s vizier Mēdinī Rā‘ī, and tensions between Muslim and Hindu elements grew. At one point, Maḥmūd was captured by the Rājā of Chitōr, and, though he was restored in Mālwa, his kingdom fell in 93 7/1531 to Bahādur Shāh of Gujarāt (see above, no. 163).

During the next three decades, there were several governors acting for the Gujarat Sultans and then the Delhi Sultans, some of whom managed to make themselves at times independent, until the last such ruler, Bāz Bahādur, was defeated by Akbar’s forces and Mālwa was incorporated into the Mughal empire as one of its provinces.

Justi, 477; Lane-Poole, 310–11; Zambaur, 292.

EI2 ‘Hind. IV. History’ (J. Burton-Page), ‘Mālwa’ (T. W. Haig and Riazul Islam).

L. White King, ‘History and coinage of Malwa’, NC, 4th series, 3 (1903), 356–98, with a genealogical table and a chronological list of rulers at pp. 359–60; also 4 (1904), 62–100.

U. N. Day, Medieval Malwa: A Political and Cultural History 1401–1557, Delhi 1965.

R. C. Majumdar et al. (eds), The History and Culture of the Indian People. VI. The Delhi Sultanate, ch. 10 C.

M. Habib and K. A. Nizami (eds), A Comprehensive History of India. V. The Delhi Sultanat (A.D. 1206–1526), ch. 12.

166

THE SULTANS OF MA‘BAR OR MADURA

734–79/1334–77

The southernmost Deccan

| ⊘ 734/1334 | Sharīf Aḥsan, Jalāl al-Dīn, governor since 723/1323, then independent |

| ⊘ 739/1338 | ‘Alā’ al-Dīn Udayji |

| ⊘ 740/1339 | Fīrūz Shāh, Quṭb al-Dīn, nephew and son-in-law of ‘Alā’ al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 740/1339 | Muḥammad Dāmghān Shāh, Ghiyāth al-Dīn, son-in-law of Sharīf Aḥsan |

| ⊘ 745/1344 | Maḥmūd Dāmghān Shāh, Nāṣir al-Dīn, nephew and son-in-law of Muḥammad Dāmghān Shāh |

| ⊘ by 757/1356 | ‘Ādil Shāh, Abu ’l-Muẓaffar Shams al-Dīn |

| ⊘ by 761/1360 | Mubārak Shāh, Fakhr al-Dīn, possibly a Bahmanid |

| ⊘ c. 774–9/c. 1372–7 | Sikandar Shāh, ‘Alā’ al-Dīn |

| c. 779/c. 1377 | Conquest hy Vi]ayanagara |

The region known to the mediaeval Islamic geographers as Ma‘bar covered the lower south-eastern coastland of the Deccan, roughly corresponding to the later Coromandel. Madura, which became its capital, was conquered by an army sent by the Delhi Sultan Muḥammad b. Tughluq in 723/1323, and the governor installed there began some years later an independent line of Sultans of Ma‘bar. The Moroccan traveller Ibn Baṭṭūṭa stayed there in 743/1342 after being at the Tughluqid court in Delhi, en route for China, and married a princess of the Ma‘bar ruling family. By the mid-fourteenth century, the Sultans seem also to have controlled the southern tip of the Deccan round westwards as far as Cochin. The Sultanate was always under threat from powerful Hindu neighbours, in particular, from the early 1350s onwards, from the kingdom of Vijayanagara situated to its north, and this last seems to have overwhelmed the Sultanate by 779/1377 or shortly afterwards.

EI2 ‘Hind. IV. History’ (J. Burton-Page), ‘Ma‘bar’ (A. D. W. Forbes).

R. C. Majumdar et al. (eds), The History and Culture of the Indian People. VI. The Delhi Sultanate, ch. 10 H.II.

M. Habib and K. A. Nizami (eds), A Comprehensive History of India. V. The Delhi Sultanat (A.D. 1206–1526), ch. 15.

Haroon Khan Sherwani and P. M. Joshi (eds), History of Medieval Deccan (1295–1724), Hyderabad 1973, 1, 57–75.

748–934/1347–1528

The northern Deccan

1. The rulers at Aḥsanābād-Gulbargā

| (746/1346 | Ismā’īl Mukh, elected king as Abu ’l-Fatḥ Ismā‘īl Shāh Nāṣir al-Dīn) |

| ⊘ 748/1347 | Ẓafar Khān, elected king as Abu ’l-Muẓaffar Ḥasan Gangu ‘Alā’ al-Dīn Bahman Shāh |

| ⊘ 759/1358 | Muḥammad I Shāh b. Ḥasan Gangu Bahman Shāh, Abu ’l-Muẓaffar Ẓafar Khān |

| ⊘ 776/1375 | Mujāhid b. Muḥammad I, Abu ’l-Maghāzī ‘Alā’ al-Dīn Mujāhid Shāh |

| 780/1378 | Dāwūd I Shāh, cousin of Mujāhid |

| ⊘ 780/1378 | Muḥammad II Shāh, grandson of Ḥasan Gangu Bahman Shāh |

| ⊘ 799/1397 | Ghiyāth al-Dīn Tahamtan b. Muḥammad II, Abu ’l-Muẓaffar |

| ⊘ 799/1397 | Dāwūd II Shāh, step-brother of Tahamtan Ghiyāth al-Dīn, Shams al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 800/1397 | Fīrūz Shāh, son-in-law of Muḥammad II, Tāj al-Dīn |

2. The rulers in Aḥmadābād-Bīdar

| ⊘ 825/1422 | Aḥmad I Shāh, son-in-law of Muḥammad II, Walī Shihāb al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 839/1436 | Aḥmad II b. Aḥmad I, Abu ’l-Muẓaffar ‘Alā’ al-Dīn Ẓafar Khān |

| ⊘ 862/1458 | Humāyūn Shāh b. Aḥmad II, Abu ’l-Maghāzī ‘Alā’ al-Din Ẓālim |

| ⊘ 865/1461 | Aḥmad III Shāh b. Humāyūn, Abu ’l-Muẓaffar Niẓām al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 867/1463 | Muḥammad III Shāh b. Humāyūn, Shams al-Dīn Lashkarī |

| ⊘ 887/1482 | Maḥmūd Shāh b. Muḥammad III, Abu ’l-Maghāzī Shihāb al-Dīn |

|

|

| 934/1528 | Dissolution of the Bahmanid Sultanate into five local sultanates of the Deccan |

As the authority of Muḥammad b. Tughluq waned in the second half of his reign, the recently-conquered parts of the Deccan began to fall away from the control of Delhi. The governor of Ma‘bar in the extreme south proclaimed himself independent and founded the Sultanate of Ma‘bar or Madura (see above, no. 166). Much more powerful and enduring was the state founded on the table-land of the northern Deccan by the Amīr Ḥasan Gangu. Ḥasan’s origins are very obscure, but they seem to have been humble ones; the claim to Persian descent, seen in his assumption of the old Iranian name of Bahman (in the Iranian national epic, son of Isfandiyār), should not be taken seriously. After his successful rebellion in Dawlatābād, Ḥasan transferred his capital southwards to Gulbargā, and for over eighty years this remained the Bahmanid capital.

The rise of the Bahmanids meant that a strong and aggressive Muslim power now confronted the two chief Hindu kingdoms of the southern Decca, Warangal and Vijayanagar. For the next century or so, warfare was frequent, ending in the case of Warangal by its overthrow in 830/1425 by Aḥmad Shāh I and its incorporation into the Bahmanid Sultanate; Vijayanagar, on the other hand, which had already overwhelmed the Sultanate of Ma‘bar or Madura (see above, no. 166), was never conquered at this time.

A point of note in this warfare was the use from the second half of the fourteenth century onwards of artillery and firearms, knowledge of these weapons being acquired through South India’s connections with lands further west. After the conquest of Warangal, Aḥmad moved his capital to the more central Bīdar, and he also carried the war northwards against the Muslim rulers of Gujarāt and Mālwa. The Bahmanid Sultanate was until the second half of the fifteenth century essentially a land-locked kingdom of the northern Deccan, but Muḥammad Shāh III’s energetic chief minister, the Khwāja-yi Jahān Maḥmūd Gāwān, who was of Persian origin, allied with Gujarāt against the Sultanate’s enemies, intervened successfully in Orissa and extended the kingdom’s eastern boundary to the Bay of Bengal, and extended its western one over the Western Ghats to Goa and the Arabian Sea coast.

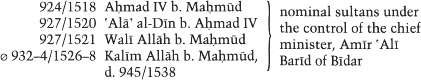

The Bahmanids thus acquired considerable fame in the Islamic world at large, especially as they made their court a great centre of learning; it was also under them that a specific Deccani style of Indo-Muslim architecture evolved. The Bahmanids were the first power of the subcontinent to exchange ambassadors with the Ottomans (between Muḥammad Shāh III and Muḥammad II Fātiḥ). The Bahmanid state, as well as being militarily powerful, had an effective civil administrative system. There was, accordingly, a need for skilled personnel, and many Turks, Persians, Arabs, etc., entered the sultans’ service. It was through this influx that there arose in the fifteenth century tensions between the native Deccani Muslims (the Dakhnīs or Deshīs) and the ‘outsiders’ (the Āfāqīs or Gharībdn or Par deshīs). Mounting internal chaos in the state and increasing ineffectiveness of the rulers are in part explicable by these rivalries. Toward the end of the fifteenth century, after the unwise execution by the sultan of Maḥmüd Gāwān, signs of disintegration began to appear. The last four sultans were fainéants under the tutelage of the Turkish amīr ‘Alī Barīdī; the fourth of these, Kalīm Allāh, appealed unsuccessfully to the Mughal Bābur for help in throwing off the yoke of the Barīdīs, and finally had to abandon his dominions for exile in Bījapur.

From the ruins of the Bahmanid Sultanate there emerged in the Muslim Deccan five successor states, all sprung from the commanders or officials of the Bahmanids: the ‘Imād Shāhīs of Berār, the Band Shāhīs of Bīdar, the ‘Ādil Shāhīs of Bījapur, the Niẓām Shāhīs of Aḥmadnagar and the Quṭb Shāhīs of Golconda (Golkondā) (see below, nos 169–73). The ‘Imād Shāhīs were absorbed by the Niẓām Shāhīs in the later sixteenth century, but the other four sultanates continued into the seventeenth century, in two instances until the time of the Mughal Awrangzīb, all of them eventually forming part of that Emperor’s vast but ephemeral empire.

Justi, 470; Lane-Poole, 316–21; Zambaur, 297–9.

EI2 ‘Bahmanīs’ (H. K. Sherwani).

E. E. Speight, ‘The coins of the Bahmani Kings of the Deccan’, IC, 9 (1935), 268–307.

Haroon Khan Sherwani, The Bahmanis of the Deccan: An Objective Study, Hyderabad-Deccan 1953, with a chronology of events and the rulers at pp. 435–44 and a detailed genealogical table at the end.

R. C. Majumdar et al. (eds), The History and Culture of the Indian People. VI. The Delhi Sultanate, ch. 11.

M. Habib and K. A. Nizami (eds), A Comprehensive History of India. V. The Delhi Sultanat (A.D. 1206–1526), ch. 14.

H. K. Sherwani and P. M. Joshi (eds), History of Medieval Deccan (1295–1724), 1,141–222, with a detailed genealogical table at p. 142, II, 432–9.

168

THE FĀRŪQĪ RULERS OF KHĀNDESH

c. 784–1009/c. 1382–1601

The north-west Deccan

| c. 784/c. 1382 | Malik Rājā Aḥmad Fārūqī b. ? Khwāja-yi Jahān A‘ẓam Humāyūn |

| ⊘ 801/1399 | Nāṣir Khān b. Rājā Aḥmad |

| 841/1437 | Mīrzā ‘Ādil Khān I b. Nāṣir |

| 844/1441 | Mīran Mubārak Khān I b. ‘Ādil I |

| 861/1457 | ‘Ādil Khān II ‘Aynā b. Mubārak |

| 907/1501 | Dāwūd Khān b. Mubārak |

| 914/1508 | Ghaznī Khān b. Dāwūd |

| 914/1508 | ‘Ālam Khān, of Aḥmadnagar |

| 914/1509 | ‘Ādil Khān III ‘Ālam Khān A‘ẓam Humāyūn b. Aḥsan Khān, descendant of Nāṣir Khān’s brother Iftikhār Khān Ḥasan b. Rājā Aḥmad |

| 926/1520 | Mīrān Muḥammad Shāh I b. ‘Ādil III |

| 943/1537 | Aḥmad Shāh b. Muḥammad I |

| 943/1537 | Mubārak Shāh II b. ‘Ādil III |

| 974/1566 | Mīrhān Muḥammad Shāh II b. Mubārak II |

| 984/1576 | Rājā ‘Ali Khān ‘Ādil Shāh IV |

| 1005–9/1597–1601 | Bahādur Shāh b. ‘Ādil Shāh IV, d. 1033/1624 |

| 1009/1600–1 | Mughal conquest |

Mediaeval Islamic Khāndesh was essentially the region in the north-west of the Deccan south of the Narbadā river and straddling the middle and upper basin of the Tāptī; its neighbours on the north were Gujarhāt and Mālwa, and on the south the Bahmanids and their successors. It owed its name ‘Land of the Khāns’ to its Fārūqī rulers, who were not admitted to the rank of Sultan by their more powerful neighbours but were known by the lesser title of Khān and often referred to by the other powers as hākim or wālī. Before the first Muslim conquest, the region had been held by the Yādavas or the Chawhāns.

The founder of the Muslim line, Malik Rājā Aḥmad, had a background of service with the Bahmanids, but then transferred to the court of the Delhi Sultan Fīrūz Shāh III and was appointed by the latter governor over certain districts in the northern Deccan. In the confusion of the declining years of the Tughluqids, Malik Rājā followed the example of his neighbour in Mālwa, Dilāwar Khān (see above, no. 165), and asserted his independence. Since he claimed descent from the second caliph ‘Umar b. al-Khattāb, who had the by-name al-Fārūq ‘the Just‘ (see above, no. 1), his successors called themselves the Fārūqīs. His son Nāṣir Khān captured the fortress of Asīrgaŕh from its Hindu chief, and built close by it the town of Burhānpur, henceforth the capital of the rulers of Khāndesh. Under ‘Ādil Khān II, Khāndesh flourished exceedingly; he failed to throw off the suzerainty of the Sultans of Gujarāt, but he did extend his power eastwards against the Hindu Rājās of Gondwāna and Jhārkand, and his exploits earned him the title Shāh-i Jhārkand ‘King of the Forest’.

In the early years of the sixteenth century, Khāndesh was racked by succession disputes, which conduced to the intervention of outside powers, especially of the Gujarāt Sultans and the successors of the Bahmanids in Aḥmadnagar, the Niẓām Shāhis of Berār (see below, no. 171). With limited manpower and economic resources available to them, the Fārūqīs only survived while they could pursue an adroit diplomatic policy between their mightier neighbours. This often involved conciliating the Sultans of Gujarāt, and at one point Mīrān Muḥammad I was designated heir-presumptive to the throne in Gujarāt; he died, however, before this claim could be consolidated. The first clash of the Fārūqīs with the Mughals came in 962/1555, and ten years later the Fārūqīs became vassals of Akbar. After c. 993/c. 1585, direct Mughal pressure grew. Bahadur Shāh offended the Mughals, and his fortress of Asīrgaŕh was in 1009/1600 captured by Akbar and the surviving Fārūqīs carried off into exile. Khāndesh now became a province of the Mughal empire, for a time renamed Dāndesh after Akbar’s son Dāniyāl.

Justi, 477; Lane-Poole, 315; Zambaur, 295.

EI2 ‘Fārūkids’ (P. Hardy), ‘Hind. IV. History’ (J. Burton-Page), ‘Khāndesh’ (idem).

T. W. Haig, ‘The Faruqi dynasty of Khāndesh’, The Indian Antiquary, 47 (1918), 113–24, 141–9, 178–86.

R. C. Majumdar et al. (eds), The History and Culture of the Indian People. VI. The Delhi Sultanate, ch. 10 B.

M. Habib and K. A. Nizami (eds), A Comprehensive History of India. V. The Delhi Sultanat (A.D. 1206–1526), ch. 11.

H. K. Sherwani and P. M. Joshi (eds), History of Medieval Deccan, I, 491–516, with a genealogical table at p. 493.

c. 892–1028/c. 1487–1619

Bīdar

| (892/1487 | Qāsim I Barīd, chief minister of the Bahmanid Sultan) |

| 910/1504 | Amīr Band I b. Qāsim, nominal vassal of the last Bahmanids |

| 950/1543 | ‘Alī b. Amīr Barīd, proclaimed his independence as Malik al-Mulūk |

| ⊘987/1579 | Ibrāhīm b.‘Alī |

| ⊘ ?997/1589 | Qāsim II |

| ? 1000/1592 | Mīrzā ‘Alī b. Qāsim II |

| ⊘? 1018/1609 | Amīr Barīd II |

| ? 1018–28/1609–19 | Mīrzā Wālī Amīr Barīd III |

| 1028/1619 | Annexation by the ‘Ādil Shahīs |

Bīdar lay in the central Deccan, to the north-west of Hyderabad City, and is now just within the north-eastern tip of Karnataka State. Qāsim Barīd was originally a Turkish slave in the service of the Bahmanids, but towards the end of the fifteenth century rose to become one of the dominating influences in the decaying Sultanate. His family continued to recognise the last titular rulers of the Bahmanids, until‘Alī Barīd finally proclaimed himself an independent prince. Bīdar had a strategically important situation, and the Bahmanids had adorned it with fine buildings, a process continued by the Barīd Shāhīs. The fortunes of these last – who remained, unlike some others of their fellow-princes of the Deccan, resolutely Sunnī in faith – declined after ‘Alī’s death, and the ‘Ādil Shāhīs of Bījapur (see below, no. 170) seized Bīdar in 1028/1619 and ended the Band Shāhīs; thirty-seven years later, Bīdar fell to the Mughal Awrangzīb.

Lane-Poole, 318, 321; Zambaur, 298.

EI2 ‘Barīd Shāhīs’ (H. K. Sherwani), ‘Bīdar’ (H. K. Sherwani and J. Burton-Page); ‘Hind. IV. History’ (Burton-Page).

Gulam Yazdani, Bidar: Its History and Monuments, Oxford 1947, ch. 1.

H. K. Sherwani and P. M. Joshi (eds), History of Medieval Deccan (1295–1724), 1,289–394, with a genealogical table at p. 290, II, 446–7.

R. C. Majumdar (ed.), The History and Culture of the Indian People. VII. The Mughul Empire (1526–1707 A.D.), Bombay 1974, ch. 14 V.

895–1097/1490–1686

Bījapur

| 895/1490 | Yūsuf ‘Ādil Khān, previously governor for the Bahmanids in Dawlatābād by 874/1470 |

| 916/1510 | Ismī‘īl b. Yūsuf |

| 941/1534 | Mallū b. Ismī‘īl |

| 941/1535 | Ibrāhīm I b. Ismā‘īl |

| ⊘ 965/1558 | ‘ Alī I b. Ibrāhīm I |

| ⊘ 987/1579 | Ibrāhīm II b. Ṭahmasp b. Ibrāhīm I |

| ⊘ 1035/1626 | Muḥammad b. Ibrāhīm II |

| 1066/1656 | ‘Alī II b. Muḥammad |

| 1083–97/1672–86 | Sikandar b. ‘Alī, d. 1111/1700 |

| 1097/1686 | Mughal conquest |

Bījapur was situated in the western part of the Bahmanid Sultanate, and is now near the northern boundary of Karnataka State. Like the founder of the ‘Imād Shāhīs, Daryā Khān (see below, no. 172), Yūsuf Khān was a commander and provincial governor for the Bahmanids, originally a slave in the service of Muḥammad III’s minister Maḥmüd Gāwān (see above, no. 167), who proclaimed his independence in 895/1489. He may well have been of Persian origin, though the story in historians partial to the ‘Ādil Shāhīs that he was of Ottoman royal blood is fanciful. He was certainly the first ruler to introduce Shī‘ism into South India, and this became the faith of three out of the five successor-states to the Bahmanids there.

The history of the ‘Ādil Shāhīs is one of almost continuous warfare with their Muslim neighbours and with the Hindu kingdom of Vijayanagar. The capital Bījapur nevertheless became a splendid centre for learning and the arts, adorned with fine buildings erected by the Shāhs, while the florescence there of Persian literature accelerated the process whereby much of Muslim South India became culturally Persianised. By the mid-seventeenth century, Bījapur was under pressure from the militant Marāt́hās, and from 1046/1636 its rulers had to acknowledge Mughal suzerainty; then inl097/1686 Awrangzīb captured Bījapur, brought the line of Shāhs to an end and incorporated their dominions into his own empire.

Justi, 470; Lane-Poole, 318, 321; Zambaur, 298–9.

EI2 ‘Ādil-Shāhīs’ (P. Hardy), ‘Bīdiāpūr’ (A. S. Bazmee Ansari), ‘Hind. IV. History’ (J. Burton-Page).

H. K. Sherwani and P. M. Joshi (eds), History of Medieval Deccan (1295–1724), 1,289–394, with a genealogical table at p. 290, II, 441–3.

R. C. Majumdar (ed.), The History and Culture of the Indian People. VII. The Mughul Empire, ch. 14 III.

895–1046/1490–1636

Aḥmadnagar

| 895/1490 | Aḥmad Niẓām Shāh Bahrī b. Timma Bhat́t́ Niẓām al-Mulk Hasan, minister of the Bahmanids, proclaimed his independence |

| 915/1509 | Burhān I b. Aḥmad |

| 961/1554 | Ḥusayn I b. Burhān |

| 972/1565 | Murtaḍā I b. Ḥusayn I |

| 997/1589 | Ḥusayn II b. Murtaḍā I |

| 998/1590 | Ismā‘īl b. Burhān II, cousin of Ḥusayn II |

| 999/1591 | Burhān II b. Ḥusayn b. Burhān I |

| 1003/1595 | Ibrāhīm b. Burhān II |

| 1004–9/1595–1600 | Bahadur b. Ibrāhīm |

| 1009/1600 | Mughal capture of Aḥmadnagar |

| 1009/1600 | Murtaḍā II b. ‘Alī b. Burhān I |

| 1019/1610 | Burhān III |

| 1041–3/1632–3 | Ḥusayn III b. Murtaḍā II |

| 1046/1636 | Division of the Niẓām Shāhī territories between the Mughals and the Ādil Shāhīs |

Aḥmadnagar is on the Deccan plateau to the east of Bombay in what is now Maharashtra State. It was founded as the capital of the Bahmanid successor state by Aḥmad Niẓām, son of the vizier to Maḥmūd Bahman Shāh, and named after himself. Aḥmad asserted his independence at Aḥmadnagar during the years of the dynasty’s decline. His son Burhān adopted Shī‘ism, thus aligning his principality with those of the ‘Ādil Shāhīs and Quṭb Shāhīs, and the ruling family was henceforth intermittently Shī‘ī. During the sixteenth century, the Niẓām Shāhīs were involved in fighting with their Muslim rivals and with Vijayanagar, but from the end of that century decline set in, there was a rapid turnover of rulers, and the Mughals captured Aḥmadnagar in 1009/1600. The last Niẓām Shāhis ruled under the ascendancy of the Ḥabashī or black African slave commander Malik‘Ambar, under whose able direction the Niẓām Shāhī fortunes revived. But after his death in 1035/1626, Mughal pressure became intense, andin 1046/1636 the Emperor Shāh Jahān and Muḥammad ‘Ādil Shāhī, alarmed at the Marāt́hā threat, divided the Niẓām Shāhī territories between themselves.

Justi, 471; Lane-Poole, 318, 329; Zambaur, 298–9.

EI2 ‘Hind. IV. History’ (J. Burton-Page), ‘Niẓām Shāhīs’ (Marie H. Martin).

Radhey Shyam, The Kingdom of Aḥmadnagar, Varanasi 1966.

H. K. Sherwani and P. M. Joshi (eds), History of Medieval Deccan (1295–1724), I, 223–77, with a genealogical table at p. 225, II, 439–41.

R. C. Majumdar (ed.), The History and Culture of the Indian People. VII. The Mughul Empire, ch. 14 II.

896–982/1491–1574

Berār

| 890/1485 | Fatḥ Allāh Daryā Khān, Imād al-Mulk, governor for the Bahmanīs in Berār since 876/1471 |

| 890/1485 | ‘Alā’ al-Dīn b. Fatḥ Allāh, assumed the title of Shāh in 896/1491 |

| 939/1533 | Daryā b. ‘Alā’ al-Dīn |

| 969–82/1562–74 | Burhān b. Daryā, under the regency of Tufāl Khān Dakhni |

| 982/1574 | Conquest by the Niẓām Shāhīs |

The extensive district of Berār comprised the northern region of the Bahmanid Sultanate, now the easternmost part of Maharashtra State. The founder of the ‘Imād Shāhī principality there, Daryā Khān, was a Hindu convert in the service of the Bahmanids, who was made governor of Berār and who became latterly one of the powers behind the throne as the Sultanate became increasingly enfeebled. He eventually asserted his independence as ruler of Berār, with his capital at Elichpur. Together with that of the Band Shāhls (see above, no. 169), Daryā Khān’s was the only Sunnī principality among the Deccani successor-states to the Bahmanids. The history of the ‘Imād Shāhīs during the eighty years or so of their independence was filled with warfare with their neighbours, such as the ‘Ādil Shāhīs and Niẓām Shāhīs. Eventually, the Niẓām Shāhīs absorbed the ‘Imād Shāhīs, but in the early seventeenth century Berār was conquered by Akbar and passed into Mughal hands.

Lane-Poole, 318, 320; Zambaur, 298.

EI2 ‘Berār’ (C. Collin Davies), ‘Hind. IV. History’ (J. Burton-Page), ‘Imād Shāhīs’(A. S. Bazmee Ansari), Suppl. ‘Eličpur’ (C. E. Bosworth).

H. K. Sherwani and P. M. Joshi (eds), Histoiy of Medieval Deccan (1295–1724), I, 278–87, with a genealogical table at p. 278.

R. C. Majumdar (ed.), The Histoiy and Culture of the Indian People. VII. The Mughul Empiie, ch. 14 IV.

901–1098/1496–1687

Golconda-Muḥammadnagar

| 901/1496 | Sulṭān Qulī Khawāṣṣ Khān Bahārlu, Quṭb al-Mulk |

| ⊘ 950/1543 | Yār Qulī Jamshīd b. Sulṭān Qulī |

| ⊘ 957/1550 | Ṣubḥān b. Jamshīd |

| ⊘ 957/1550 | Ibrāhīm b. Sulṭān Qulī |

| ⊘ 988/1580 | Muḥammad Qulī b. Ibrāhīm |

| ⊘0 1020/1612 | Muḥammad b. Muḥammad Amīn b. Ibrāhīm |

| ⊘ 1035/1626 | ‘Abdallāh b. Muḥammad |

| ⊘1083–98/1672–87 | Abu ‘1-Ḥasan, son-in-law of ‘Abdallāh |

| 1098/1687 | Mughal conquest |

The Quṭb Shāhīs ruled over the east-central, largely Telugu-speaking part of the Deccan (now Andhra Pradesh State) from the ancient hill-fort of Golconda and then from their new city of Hyderabad (Ḥaydarābād), which was adjacent to the fortress and planned by Muḥammad Qulī in 997/1589, and to which the state capital was moved some time afterwards.

The founder of the line, Sulṭān Qulī, was a Türkmen from western Persia who was descended from the Qara Qoyunlu (see above, no. 145) and who migrated to seek his fortune in South India soon after the fall of the Türkmen dynasty. He became one of Maḥmüd Shāh Bahmanī’s chief ministers and governor of Tilang Andhra or Telingana, the eastern part of the Bahmanid Sultanate and nucleus of the future Quṭb Shāhī principality. His successors turned what had been de facto independence into the reality of sovereign power. Sulṭān Qulī Quṭb Shāh had vigorously proclaimed his Twelver Shl‘ism, eventually recognising the Safawid Shāh ‘Ismā‘īl I (see above, no. 148) as his spiritual suzerain, and the Quṭb Shāhī court became a vigorous centre for Persian literature and culture in general. The Quṭb Shāhīs were almost continuously involved in warfare with the other successor-states to the Bahmanids, the ‘Ādil Shāhīs and the Niẓām Shāhīs (see above, nos 170, 171), and with Vijayanagar, until Shāh Jahān intervened in 1045/1636 and forced on the Quṭb Shāhīs their recognition of Mughal suzerainty, in the shape of tribute and a treaty of submission (inqiyād-nāma) which, inter alia, banned the public celebration of Shī’ī practices and festivals. Some fifty years later, Awrangzīb ended the Shāhs’semi-independent status completely and incorporated their lands into his empire.

Justi, 471; Lane-Poole, 318, 321; Zambaur, 298–9.

EI2 ‘Golkond́ā’ (H. K. Sherwani), ‘Haydarābād. a. City’ (J. Burton-Page), ‘Hind. IV. History’ (idem), ‘Kuṭb Shāhī‘’ (R. M. Eaton).

H. K. Sherwani and P. M. Joshi (eds), History of Medieval Deccan (1295–1724), I, 411–90, with a genealogical table at p. 413, II, 446–7.

Haroon Khan Sherwani, History of the Qutb Shāhī Dynasty, New Delhi 1974, with a genealogical table at the end.

R. C. Majumdar (ed.), The History and Culture of the Indian People. VII. The Mughul Empire, ch. 14 IV.

926–99/1520–91

Multan and Sind

| c. 880/c. 1475 | Dhu ‘1-Nūn Beg Arghūn, governor of Kandahar and northeastern Baluchistan for the Tīmūrids |

| ⊘ (913/1507 | Shāh Beg b. Dhi ‘1-Nūn, governor in Kandahar for the Shïbānids) |

| 926/1520 | Shāh Beg, now as ruler in Upper Sind and then the whole province |

| 930–61/1524–54 | Shāh Ḥusayn b. Shāh Beg, d. 963/1556 |

2. The line of Muḥammad ‘Īsā Tarkhān

| 961/1554 | Muḥammad ‘Īsā Tarkhān b. ‘Abd al-‘Alī, in Lower Sind (Maḥmūd Gokaltāsh, in Upper Sind until 982/1574) |

| 975/1567 | Muḥammad Bāqī b. Muḥammad Īsā |

| 993–9/1585–91 | Jānī Beg b. Muḥammad Bāqī, d. 1008/1599 |

| 999/1591 | Mughal conquest of Lower Sind |