NINE

The Caucasus and the Western

Persian Lands before the Seljuqs

83 to early eleventh century /799 to early seventeenth century

Sharwān in eastern Transcaucasia, with their original centre at Yazīdiyya

1. The first line of Yazīdī Shahs

| ⊘ 780/1378 | Ibrāhīm I b. Muḥammad b. Kay Qubādh |

| ⊘ 821/1418 | Khalīl I b. Ibrāhīm I |

| ⊘ 867/1463 | Farrukhsiyar b. Khalīl I |

| 905/1500 | Bayram b. Farrukhsiyar |

| 907/1502 | Ghāzī b. Farrukhsiyar |

| ⊘ 908/1503 | Maḥmūd b. Ghāzī |

| ⊘ 908/1503 | Ibrāhīm II or Shaykh Shāh, uncle of Maḥmūd b. Ghāzi |

| ⊘ 930/1524 | Khalīl II b. Ibrāhīm II |

| ⊘ 942/1535 | Shāh Rukh b. Farrukh b. Ibrahim II, k. 946/1539 |

| 945/1538 | Ṣafawid occupation |

| 951/1544 | Abortive revanche by Burhān ‘Alī b. Khalīl II, d. 958/1551 |

| 958/1551 | Safawid occupation |

| 987-?/1579-? | Abū Bakr b. Burhān ‘Alī as governor for the Ottomans |

| 1016/1607 | Safawid rule definitively established |

The title of Sharwān Shāh may well go back to Sāsānid times. The Islamic line of Arab Sharwān Shāhs began with the governor Yazīd b. Mazyad, among whose extensive territories in Armenia, north-western Persia and eastern Transcaucasia was the region of Sharwān between the south-eastern spur of the Caucasus mountains and the lower Kur river valley.

Haytham b. Muhammad is said to have been the first governor specifically of Sharwān, one by now in effect independent and succeeding hereditarily, to assume the actual title of Sharwān Shāh. From the early fourth/tenth century, the Shāhs had their capital in Yazidiyya, perhaps the earlier Shammakhi, but they were also often to intervene in, and at times control, Bāb al-Abwāb or Darband on the Caspian coast (see below, no. 68). Over the decades, the Shāhs had to fight off the Georgians to their west, and, in the fifth/eleventh century, incursions from northern Persia of the Turkmens. After the notable reign of Fariburz I b. Sallār, the chronology and nomenclature of the succeeding Shāhs become somewhat fragmentary and tentative, for the detailed source for the history of the earlier period, a local history of Sharwān and Bāb al-Abwāb preserved in a later Ottoman historian, comes to an end; for subsequent rulers, we depend largely on literary references from the lands outside Sharwān and the evidence from coins. These Shahs seem to have been known as the Kasrānids (it has been suggested that this was a name or title of Farīdūn I b. Farīburz), though clearly connected with their predecessors; already, as is apparent from their onomastic, these original Arabs had by now become profoundly Iranised, and in fact claimed descent from Bahrām Gūr.

The line came to an end at the time of Tīmūr’s conquests, but the later Ottoman historian Münejjim Bashï supplies details of what he calls the second line of Sharwān Shāhs, carrying these up to the late sixteenth century, and coins are known from several of these rulers. During that century, possession of Sharwān oscillated periodically between Safawids and Ottomans, until by the early seventeenth century the indigenous Shāhs had finally disappeared and Sharwān became for some two centuries a governorate of the Safawid empire.

Justi, 454; Sachau, 12 no. 18; Zambaur, 181–2; Album, 53.

EI2 ‘al-Kabk’ (C. E. Bosworth); ‘Shírwān Shāhs (W. Barthold and Bosworth).

V. Minorsky, A History of Sharvān and Darband in the 10th-llth centuries, Cambridge 1958.

D. K. Kouymjian, A Numismatic History of Southeastern Transcaucasia and Adharbayjān based on the Islamic Coinage of the 5th/11th to the 7th/13th Centuries, Columbia University Ph.D. thesis 1969, unpubl. (UMI Dissertation Services, Ann Arbor), 61–6, 136–242, with a genealogical table at p. 242.

W. Madelung, ‘The minor dynasties of northern Iran’, in The Cambridge History of Iran. IV. From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs, ed. R. N. Frye, Cambridge 1975, 243–9.

255–468/869–1075

Bāb al-Abwāb or Barbaria and its hinterland

| 255/869 | Hāshim b. Surāqa al-Sulamī, governor for the ‘Abbāsids, proclaimed himself independent |

| 271/884 | ‘Umar b. Hāshim |

| 272/885 | Muḥammad b. Hāshim |

| 303/916 | ‘Abd al-Malik b. Hāshim |

| 327/939 | Aḥmad b. ‘Abd al-Malik, first reign |

| (327/939 | Haytham b. Muhammad of Sharwān, first reign) |

| 339/941 | Aḥmad b. ‘Abd al-Malik, second reign |

| (330/941 | Haytham b. Muḥammad, second reign) |

| (330/942 | Aḥmad b. Yazīd of Sharwān) |

| (342/953 | *Khashram Aḥmad b. Munabbih, of Lakz) |

| 342/954 | Aḥmad b. ‘Abd al-Malik, third reign |

| 366/976 | Maymūn b. Aḥmad |

| 387/997 | Muḥammad b. Aḥmad |

| 393/1003 | Manṣūr b. Maymūn, first reign |

| (410/1019 | Yazīd b. Aḥmad of Sharwān, first reign) |

| 412/1021 | Manṣūr b. Maymūn, second reign |

| (414/1023 | Yazīd b. Aḥmad of Sharwān, second reign) |

| 415/1024 | Manṣūr b. Maymūn, third reign |

| 425/1034 | ‘Abd al-Malik b. Manṣūr, first reign |

| (425/1034 | ‘Ali b. Yazīd of sharwān) |

| 426/1035 | ‘Abd al-Malik b. Manṣūr, second reign |

| 434/1043 | Manṣūr b.‘Abd al-Malik, first reign |

| 446/1054 | Lashkarī b. ‘Abd al-Malik |

| 447/1055 | Manṣūr b. ‘Abd al-Malik, second reign |

| 457/1065 | ‘Abd al-Malik b. Lashkarī, first reign, as vassal of Farīburz b. Sallār of Sharwān |

| (461/1068 | Farīburz b. Sallār, of Sharwān) |

| 463/1070 | ‘Abd al-Malik b. Lashkarī |

| 468/1075 | Maymūn b. Manṣūr |

| 468/1075 | Occupation of Bāb al-Abwāb by the Seljuq commander Sāwtigin |

Bāb al-Abwāb or Darband commanded the very narrow coastal route between the western shore of the Caspian and the mountains of Dāghistān, and thus enjoyed a very important strategic position. Hence it was a well-fortified bastion of Islam, a thaghr, against such steppe peoples to the north as the Turkish Khazars. It was furthermore a busy port, and this Caspian Sea trade plus the traffic in slaves from the South Russian steppes combined to make it highly prosperous.

The origins of the line of Hāshimids (who may have been clients of the Banū Sulaym rather than pure-born Arabs) go back to Umayyad times, when they seem first to have been appointed governors in Darband. With the internal chaos of the ‘Abbāsid caliphate in the mid-ninth century, Hāshim b. Surāqa was able to make himself independent in Darband, and his descendants exercised power, with frequent interruptions, for over two centuries. The fortunes of Darband were indeed closely intertwined with those of neighbouring Sharwān, whose Shāhs (perhaps with the cachet of superior social status: see above, no. 67) intervened in Darband on numerous occasions. A basic cause, however, of the instability of Hāshimid rule was the strength within Darband of a strong and influential body of notables, forming an urban aristocracy, who frequently and often successfully challenged the amīrs’ authority. The line was finally brought to an end, it seems, when the Seljuq sultan Alp Arslan awarded the Transcaucasian lands to his slave commander Sāwtigin, after which the Hāshimids apparently disappeared.

However, in the twelfth century, we have some sketchy knowledge of another line of Maliks of Darband (who may possibly have claimed descent from the previous dynasty), mainly from their coins. This line seems to have come to an end in the opening years of the thirteenth century when Darband came under the rule of the Sharwān Shāhs.

Sachau, 13–14 no. 21; Zambaur, 185.

EI1 ‘Derbend’ (W. Barthold); EI2 ‘Bāb al-Abwāb’ (D. M. Dunlop); ‘al-Kabk’ (C. E. Bosworth)

V. Minorsky, A History of Sharwān and Darband.

D. K. Kouymjian, A Numismatic History of Southeastern Caucasia and Adharbayjān, 66–8, 243–87, with a genealogical table at p. 287 (on the twelfth-century Maliks).

W. Madelung, in The Cambridge History of Iran, IV, 243–9.

Late second century to fifth century/late eighth century to eleventh century

Daylam, with their centre in the Rūdbār-Shāh Rūd valleys

| 175/791 | the ‘King of Daylam’ (? Justān I), sheltering ‘Alids |

| 189/805 | Marzubān b. Justan I, recognised the caliph Hārūn al-Rashīd at Rayy |

| ? | Justān II b. Marzubān, d. c. 251/c. 865 |

| c. 251–c.292/ |

|

| c. 865–c. 905 | Wahsūdān b. Justān II |

| c. 292/c. 905 | Justān III b. Wahsūdān, killed c. 304/c. 916 |

| 307/919 | ‘Alī b. Wahsūdān, in ‘Abbāsid service at Iṣfahān and Rayy from c. 300/c. 913 onwards |

| ? | Khusraw Fīrūz b. Wahsūdān, ruler in Rūdbār, killed after 307/919 |

| ? | Mahdī b. Khusraw Fīrūz, in Rūdbār |

| ? | Justān IV, d. 328/940, ? father of Manādhār |

| 336/947 | Manādhar b. Justān IV, ruling in Rūdbār, ? died between 358/969 and 361/972 |

| ⊘361–3/972–4 | Khusraw Shāh b. Manādhar, ruling in Rūdbār, ? died between 392/1002 and 396/1006 |

Disappearance of the dynasty in the course of the fifth/eleventh century |

The Justānids appear as ‘Kings of Daylam’ towards the end of the eighth century, wih their centre in the Rūdbār of Alamūt, running into the valley of the Shāh Rūd, to become notorious two centuries or so later as the main centre of the Nizārī Ismā‘īlīs in Persia (see below, no. 101); but they may well have been ruling in Daylam before this. They appear in Islamic history as part of an upsurge of the hitherto submerged indigenous peoples of north-western Persia – Daylamīs, Kurds, etc. The ‘Daylamī intermezzo’, of which the Justānids and several other dynasties, culminating in the Būyids (see below, no. 75), formed part, spanned the history of western and central Persia between the disintegration of the Abbāsid caliphate’s unity and their Arab governors in western Persia and the constituting of the Great Seljuq empire (see below, no. 91, 1) across the Middle East.

After Marzubān b. Justān (I) became a Muslim in 189/805, the fortunes of the ancient family of Justānids then became connected with the Zaydī Alids of the Daylam region, and they seem to have adopted Shī‘ism. In the tenth century, they tended to be eclipsed by the vigorous and expanding sister Daylamī dynasty of the Musāfirids or Sallārids of Ṭārum (see below, no. 71, 2), with whom the Justānids had close marriage ties, although they preserved their seat at Rūdbār in the highlands of Daylam as allies of the Būyids. In the eleventh century, the Justānids are sporadically mentioned as recognising the suzerainty of the Ghaznavids and then of the incoming Seljuqs, but thereafter they fade from history.

Justi, 440; Zambaur, 192 (both of them fragmentary and defective).

EI2 ‘Daylam’ (V. Minorsky).

R. Vasmer, ‘Zur Chronologie der Ǧastāniden und Sallāriden’, Islamica, 3 (1927), 165–70, 177–9, 482–5, with a genealogical table at p. 184 correcting Zambaur.

Sayyid Aḥmad Kasravī, Shahriyārān-i gum-nām, Tehran 1307/1928, I, 22–34, with a genealogical table at p. 111.

W. Madelung, in The Cambridge History of Iran, IV, 208–9, 223–4.

276–312/889–929

Azerbaijan (Ādharbāyjān)

| 276/889 | Muḥammad b. Abi ’1-Sāj Dīwdād I b. Dīwdast |

| 288/901 | Dīwdād II b. Muḥammad, Abu ’1-Musāfir |

| ⊘ 288/901 | Yūsuf b. Abi ’1-Sāj Diwdād I, Abu ’1-Qāsim |

| ⊘ 315–17/928–9 | Fath b. Muḥammad b. Abi ’1-Sāj, Abu ’1-Musāfir |

| 317/929 | End of the line of governors |

The Sājids were a line of caliphal governors in north-western Persia, the family of a commander in the ‘Abbāsid service of Soghdian descent which became culturally Arabised. Abu ’1-Sāj Dīwdād I was governor in Baghdad and Khūzistān, but with his son Muḥammad’s appointment to Azerbaijan in 276/889, the family acquired what was to be its power-base for some forty years. During their tenure of power, the Sājids led numerous campaigns against such Armenian princes as the Bagratids and the Ardzrunids of Vaspurakan and extended their suzerainty over them. After the murder of Abu ’1-Musāfir Fath, however, their rule in Azerbaijan ended, and control of the region passed to various Daylamī and Kurdish chiefs.

Sājid rule was thus important for the extension of Arab political and cultural influence over the Armenian provinces of eastern Transcaucasia; but, like the Tāhirids (see below, no. 82), the Sājids always remained faithful to their ‘Abbāsid masters and must be considered as autonomous but not independent of Baghdad.

Lane-Poole, 126; Zambaur, 179; Album, 33.

EI2 ‘Sādjids’ (C. E. Bosworth). Eir ‘Banu Saj’ (W. Madelung).

C. Defrémery, ‘Mémoire sur la famille des Sadjides’, JA, 4th series, 9 (1847), 409–16; 10 (1847), 396–436.

W. Madelung, in The Cambridge History of Iran, IV, 228–32.

Before 304–c. 483/before 916–c. 1090

Daylam, with their centres at Ṭārum and Samīrān, and then in Azerbaijan and Arrān also

| before 304/before 916 | Muḥammad b. Musāfir |

Division of the family into two branches

| ⊘ 330/941 | Marzubān I b. Muḥammad, d. 346/957 |

| ⊘ 346–9/957–60 | Justān I b. Marzubān I |

| ⊘ 349/960 | Ismā‘īl b. Wahsūdān |

| ⊘ 351–73/962–83 | Ibrāhīm I b. Marzubān I |

| ⊘ 355/966 | Nūḥ b. Wahsūdān, Abu ’1-Hasan, in Ardabīl, thereafter in Samīrān until c. 379/c. 989 |

| 373/983 | Conquest of the greater part of Azerbaijan by the Rawwādids |

| 373–4/983–4 | Marzubān II b. Ismā’īl b. Wahsūdān, ruled over a small part of Azerbaijan (? Miyāna) until dispossessed by the Rawwādids |

| ⊘ 330/941 | Wahsūdān b. Muḥammad, Abū Manṣūr, first reign |

| (c. 354/c. 965 | Būyid occupation of Ṭārum) |

| 355/966 | Wahsūdān b. Muhammad, second reign |

| ? | Marzubān II b. Ismā‘il b. Wahsūdān |

| 387/997 | Ibrāhīm II b. Marzubān II, briefly dispossessed by the Ghaznawids in 420/1029 |

| ? | Justan II b. Ibrahim II, Abū Ṣālih, reigning in 437/1045 |

| ? | Musāfir b. Ibrāhim II, reigning in 454/1062 |

| ? | Dynasty extinguished by the Ismā‘īlīs of Alamūt |

The Daylamī Musāfirids were a sister-dynasty of the Justānids and were closely linked with them (see above, no. 69), but, as a newer and, it seems, more vigorous family, were to direct their energies outside Daylam as well as within it. Whereas the Ziyārids and Būyids (see below, nos 81, 75) strove to control the rich lands of northern Persia and, in the case of the latter family, southern Persia and Iraq also, the Musāfirids expanded westwards into Azerbaijan and the eastern fringes of Armenia, where the collapse of the line of Sājid governors (see above, no. 70) had left a vacuum. ‘Musāfir’ is apparently an attempt to Arabise Persian Asfār/Asvār, but other names for the dynasty are found in the sources: Sallarids (< Pers. sālār ‘military commander’) and Langarids (probably from a personal name, this form being more probable, it appears, than that of Kangarids).

Muhammad b. Musāfir, the first member of the line to appear in history, held the key fortresses of Ṭārum and Samīrān in the Safīd Rūd valley of Daylam, and from these he increased his power at the expense of the older dynasty of the Justānids. After the imprisonment of Muhammad by his sons in 330/941, the family split into two branches, with Wahsūdān remaining in Ṭārum while his brother Marzubān extended his power northwards and westwards into Azerbaijan, Arrān, some districts of eastern Armenia and as far as Darband on the Caspian coast. Around this time, the Musāfirids seem to have espoused Ismā‘īlī Shī‘ī doctrines, which were spreading within Daylam. The two branches frequently squabbled, and the latter failed to maintain itself in face of the growing power of the Rawwādids of Tabrīz (see below, no. 72). The Daylam branch was also for a while hard pressed by the Būyids, and for a time lost Shamīrān to Fakhr al-Dawla of Rayy. Their fortunes subsequently revived, and they were able to expand as far south as Zanjan. But the dynasty’s history now becomes obscure and fragmentary. It survived confrontation with the Ghaznawids (see below, no. 158) and later submitted to the Seljuq Ṭoghrïl Beg. After this comes only silence, but it is probable that the last obscure Musāfirids were ended by the Ismā‘īlīs of Alamūt (see below, no. 101).

Justi, 441 (linking the Musāfirids with the Rawwādids under the common designation of Wahsūdānids); Sachau, 14 no. 23; Zambaur, 180 (defective); Album, 33–4.

EI2 ‘Musafirids’ (V. Minorsky).

R. Vasmer, ‘Zur Chronologie der Ǧastāniden und Sallāriden’, 170–81, with a genealogical table at p. 184 correcting Zambaur.

Sayyid Ahmad Kasravī, Shahriyārān-i gum-nām, I, 52–120, with a genealogical table at p. 112.

V. Minorsky, Studies in Caucasian History, London 1953.

C. E. Bosworth, ‘The political and dynastic history of the Iranian world (A.D. 1000–1217)’, in The Cambridge History of Iran. V. The Saljuq and Mongol Periods, ed. J. A. Boyle, Cambridge 1968, 30–2.

W. Madelung, in The Cambridge History of Iran, IV, 232–6.

Early fourth century to 463/early tenth century to 1071

Azerbaijan, with their centre at Tabriz (Tabrīz)

| ? | Muḥammad b. Ḥusayn al-Rawwādī |

| 344/955 | Ḥusayn I b. MuḤammad, Abu ‘1-Hayjā’ |

| ⊘ 378/988 | Mamlān or Muḥammad I b. Husayn, Abu ‘1-Hayja’ |

| 391/1001 | Ḥusayn II b. Mamlān I, Abū Naṣr |

| 416/1025 | Wahsūdān b. Mamlān I, Abū Manṣūr |

| 451/1059 | Mamlān or Muḥammad II b. Wahsūdān, Abū Naṣr |

| (463/1071 | Seljuq occupation of Azerbaijan) |

| ? | Ahmadīl b. Ibrāhīm b. Wahsūdān, died in Marāgha 510/1116 |

| 510/1116 | Aḥmadīlī Atabegs of Marāgha |

Although Daylamīs were most prominent in the upsurge in northern Persian of Iranian peoples in the tenth century, the role of other races was not negligible. The Shaddādids of Arrān (see below, no. 73) were probably of Kurdish origin, while the Rawwādids (the form ‘Rawādi’ later becomes common in the sources) were in the tenth century accounted Kurdish. In reality, the family was probably Arab in origin, from the Yemeni tribe of Azd, and in the early ‘ Abbāsid period they had been governors of Tabriz; but, just as the Yazīdī Sharwān Shāhs became Iranised (see above, no. 67), so the Rawwadids became Kurdicised, with such names as ‘Mamlān’ and ‘Ahmadīl’ being characteristic Kurdish versions of the familiar Arabic names ‘Muhammad’ and ‘Ahmad ’.

Like their Musāfirid neighbours, the Rawwādids took advantage of the confused state of post-Sājid Azerbaijan. Despite help from the Būyids, that branch of the Musāfirids which had installed itself in Azerbaijan (see above, no. 71, 1) was gradually driven out by Abu ‘1-Hayjā’ Mamlān I, so that by 374/984 all the region was in Rawwādid hands. In the next century, the most outstanding member of the dynasty was Wahsūdān b. Mamlān I. With the help of Kurdish neighbours, he successfully coped with the first incursions of the Oghuz Turkmens, but in 446/1054 submitted to Ṭoghrïl Beg. Thereafter, the Rawwādids ruled as Seljuq vassals until Alp Arslan returned from his Anatolian campaigns and deposed Mamlān II b. Wahsūdān. However, at least one later member of the family is known, Aḥmadīl of Marāgha, and his name was perpetuated in the twelfth century by a line of his Turkish ghulāms, called after him the Aḥmadīlīs see below, no. 98).

Justi, 441; Zambaur, 180 (like Justi, erroneously taking the Rawwādids to be a branch of the Musāfirids); Album, 34.

EI1 ‘Tabrīz’ (V. Minorsky); EI2 ‘Rawwādids (C. E. Bosworth).

Sayyid Aḥmad Kasravī, Shahriyārān-i gum-nām, II, 130–58.

V. Minorsky, Studies in Caucasian History, 167–9, with genealogical table at p. 167.

C. E. Bosworth, in The Cambridge History of Iran, V, 34–5.

W. Madelung, in ibid., IV, 239–43.

c. 340–570/c. 951–1174

Arrān and eastern Armenia

1. The main line in Ganja and Dvīn

| c. 340/c. 951 | Muḥammad b. Shaddād b. Q.r.t.q, in Dvīn |

| 360/971 | ‘Alī Lashkarī b. Muḥammad, in Ganja |

| 368/978 | Marzubān b. Muḥammad |

| ⊘ 375/985 | Faḍl I b. Muḥammad |

| 422/1031 | Mūsā b. Faḍl I, Abu ‘l-Fatḥ |

| 425/1034 | ‘Ali Lashkarī II b. Mūsā |

| 440/1049 | Shāwur I b. Faḍl I, Abu ’1-Aswār, from 413/1022 in Dvīn, from 441/1049 in Ganja also |

| 459/1067 | Faḍl II b. Abu ‘1-Aswār Shāwur I |

| 466–8/1073–5 | Faḍl III (Faḍlūn) b. Faḍl II |

| 468/1075 | Occupation of Arrān by the Seljuq commander Sāwtigin |

| c. 465/c. 1072 | Manūchihr b. Abi ’1-Aswār Shāwur I, Abū Shuj‘ |

| c. 512/c. 1118 | Shāwur II b. Manūchihr, Abu ’1-Aswār |

| 518/1124 | Georgian occupation |

| c. 519/c. 1125 | Faḍl IV (Faḍlūn) b. Abi ’1-Aswār Shāwur II, d. 524/1130 |

| c. 525/c. 1131 | Khūshchihr b. Abi ’1-Aswār Shāwur II |

| ? | Maḥmūd b. Abi ’1-Aswār Shāwur II |

| ? | Shaddād b. Maḥmūd, Fakhr al-Dīn, ruling in 549/1154 |

| 550/1155 | Faḍl V b. Maḥmūd |

| 556/1161 | Georgian occupation |

| ⊘ 559–70/1164–74 | Shāhanshāh b. Maḥsmūd |

| 570/1174 | Georgian occupation |

| ? | Sulṭān (? = Shāhanshāh) b. Maḥmūd, mentioned in 595/ 1199 |

The Shaddādids were another of the dynasties which arose in north-western Persia during the ‘Daylami interlude’, and it is probable that they were of Kurdish origin. In such a linguistically and ethnically confused region as north-western Persia and the adjacent Caucasus, onomastic was also varied; the Shaddādids’ need to find a place for themselves between the Daylamīs of Azerbaijan on one side, and the Christian Armenians and Georgians on the other, doubtless explains why Daylamī names like Lashkarī and Armenian ones like Ashūṭ/Ashot are found in the Shaddādids’ genealogy.

In the middle years of the tenth century, the Kurdish adventurer Muḥammad b. Shaddād established himself at Dvīn (near Erivan in the modern Armenian Republic), a town at that time in the possession of the Musāfirids (see above, no. 71). Despite an attempt to secure Byzantine aid, Muḥammad could not prevent the Daylamīs from regaining Dvīn, but in 360/971 his sons successfully ejected the Musāfirids from Ganja in Arrān (the region of Transcaucasia between the Kur and Araxes rivers), and Ganja (the later Imperial Russian Elizavetapol, now in the Azerbaijan Republic) then became the capital of the main line of Shaddādids for a century. They now undertook with vigour the defence of Islam in this region, fighting the Georgian Bagratids, various Armenian princes, the Byzantines, the Alans or Ossetians, and the Rūs from beyond the Caucasus; in particular, Abu ’l-Aswār Shāwur I, most eminent of his house, acquired a great contemporary renown as a fighter for the faith. The Shaddādids submitted to the Seljuq Ṭoghrïl Beg when he first appeared in the Transcaucasian region, but in 468/1075 Alp Arslan’s general Sāwtigin invaded Arrān and forced Faḍl III or Faḍlūn to yield up his ancestral territories. However, another branch was installed in Ānī, capital of the Armenian Bagratids, after its capture by the Seljuqs in 465/1072, and it lasted through many vicissitudes up to the Georgian resurgence in the second half of the twelfth century; a Shaddādid is still mentioned in a Persian inscription from Ānī at the end of the century.

Justi, 443; Sachau, 14 no. 22; Zambaur, 184–5 (all incomplete); Album, 34.

EI2 ‘Shaddādids’ (C. E. Bosworth).

Sayyid Aḥmad Kasravī, Shahriyārān-i gum-nām, III, 270–332, with a genealogical table at pp. 328–9.

V. Minorsky, Studies in Caucasian History, with genealogical tables at pp. 6, 106.

C. E. Bosworth, in The Cambridge History of Iran, V, 34–5.

W. Madelung, in ibid., IV, 239–43.

Early third century to 284/early ninth century to 897

Central Jibāl, with their centre at Karaj

al-Qāsim b.‘Īsā al-‘Ijlī, Abū Dulaf, governor of Jibāl, d. c. 225/c. 840 |

|

| ⊘ c. 225/c. 840 | ‘Abd al-‘Azīz b. Abī Dulaf |

| ⊘260/874 | Dulaf b. ‘Abd al-‘Azīz |

| ⊘ 265/879 | Aḥmad b. ‘Abd al-‘Azīz, Abu ’l-‘Abbās |

| ⊘ 280/893 | ‘Umar b. ‘Abd al-‘Azīz |

| 283–4/896–7 | al-Ḥārith b. ‘Abd al-Azīz, Abū Laylā |

| 284/897 | Reversion of their territories to the caliphate |

Abū Dulaf came of ancient Arab tribal stock, and from a family with a tradition of service to the ‘Abbāsids. Hārūn al-Rashīd appointed him governor of Jibāl or Media, and he served subsequent caliphs there, acquiring a reputation both as a brave military commander and as a littérateur and maecenas. His centre of power became the fief, an īghār or hereditary, tax-free concession, centred on Karaj between Hamadan (Hamadhān) and Isfahan (Iṣfahān), a place which henceforth became known as Karaj Abī Dulaf. His son‘Abd al-‘Aziz and the latter’s sons, all functioning as governors for the ‘Abbāsids and exercising their military skills, succeeded him in succession, confirmed by the caliphs (to whom they remained firmly loyal) but minting their own coins, until al-Ḥārith b. ‘Abd al-‘Aziz was killed in battle in 284/897. The district then erverted to direct ‘Abbāsid control, although descendants of the Dulafids continued to be prominent in the public affairs of the caliphate for well over a century.

Lane-Poole, 125; Zambaur, 199; Album, 32.

EI2 ‘Dulafids’ (E. Marin); ‘al-Kāsim b.‘Īsa’ (J. E. Bencheikh); EIr ‘Abū Dolaf ‘Ejlī’ (F. M. Donner).

M. Canard, Histoire de la dynastie des H’amdanides de Jazîra et de Syrie, I, Algiers 1951, 311–13.

320–454/932–1062

Northern, western and southern Persia and Iraq

| ⊘320/932 | ‘Alī b. Būya, Abu ’1-Ḥasan ‘Imād al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 335–66/947–77 | Ḥasan b. Būya, Abū ‘Alī Rukn al-Dawla |

(a) The branch in Hamadan and Isfahan

| ⊘ 366/977 | Būya b. Rukn al-Dawla Ḥasan, Abū Manṣūr Mu’ayyid al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 373/983 | ‘Alī b. Rukn al-Dawla Ḥasan, Abu ’1-Ḥasan Fakhr al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 387/997 | Fulān b. Fakhr al-Dawla ‘Ali, Abū Ṭāhir Shams al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 412–c. 419/ |

|

| 1021–c. 1028 | Fulān b. Shams al-Dawla, Abu ’1-Ḥasan Samā’ al-Dawla, under Kākūyid suzerainty |

| ⊘ 366/977 | ‘Alī b. Rukn al-Dawla Ḥasan, Abu ’1-Hasan Fakhr al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 387–420/997–1029 | Rustam b. Fakhr al-Dawla ‘Alī, Abū Ṭālib Majd al-Dawla |

| 420/1029 | Ghaznawid conquest |

2. The line in Fars (Fārs) and Khūzistān

| ⊘ 322/934 | ‘Alī b. Būya, Abu ’1-Hasan ‘Imād al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 338/949 | Fanā Khusraw b. Rukn al-Dawla Ḥasan, Abū Shujā‘ ‘Aḍud al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 372/983 | Shīrzīl b. Fanā Khusraw ‘Aḍud al-Dawla, Abu ’1-Fawāris Sharaf al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 380/990 | Marzubān b. Fanā Khusraw ‘Adud al-Dawla, Abū Kālijār Ṣamṣām al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 388/998 | Fīrūz b. Fanā Khusraw ‘Aḍud al-Dawla, Abū Naṣr Bahā’ al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 403/1012 | Abū Shujā‘ b. Fīrūz Bahā’ al-Dawla, Sulṭān al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 415/1024 | Abū Kālījār Marzubān b. Abī Shujā‘ Sulṭān al-Dawla, ‘Imād al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 440/1048 | Khusraw Fīrūz b. Marzubān ‘Imād al-Dīn, Abū Naṣr al-Malik al-Raḥīm |

| 447–54/1055–62 | Fūlād Sutūn b. Marzubān ‘Imād al-Dīn, Abū Manṣūr, in Fārs only |

| 454/1062 | Power in Fars seized by the Shabānkāra’ī Kurdish chief Faḍlūya |

3. The line in Kirman (Kirmān)

| 324/936 | Aḥmad b. Būya, Abu ’l-Ḥusayn Mu‘izz al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 338/949 | Fanā Khusraw b. Ḥasan Rukn al-Dawla, Abū Shujā‘ ‘Aḍud al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 372/983 | Marzubān b. Fanā Khusraw ‘Aḍud al-Dawla, Abū Kālījār Ṣamṣām al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 388/998 | Fīrūz b. Fanā Khusraw ‘Aḍud al-Dawla, Abū Naṣr Bahā’ al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 403/1012 | Abu ’1-Fawāris b. Fīrūz Bahā’ al-Dawla, Qawām al-Dawla |

| 419–40/1028–48 | Marzubān b. Abī Shujā‘ Sulṭān al-Dawla, Abū Kālījār ‘Imād al-Din |

| 440/1048 | Seljuq line of Qāwurd |

| ⊘ 334/945 | Aḥmad b. Būya, Abu ’l-Ḥusayn Mu‘izz al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 356/967 | Bakhtiyār b. Aḥmad Mu‘izz al-Dawla, Abū Manṣūr ‘Izz al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 367/978 | Fanā Khusraw b. Ḥasan Rukn al-Dawla, Abū Shujā‘ ‘Aḍud al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 372/983 | Marzubān b. Fanā Khusraw ‘Aḍud al-Dawla, Abū Kālījār Ṣamṣām al-Dawla |

| 376/987 | Shīrzīl b. Fanā Khusraw ‘Aḍud al-Dawla, Abu ’1-Fawāris Sharaf al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 379/989 | Fīrūz b. Fanā Khusraw ‘Aḍud al-Dawla, Abū Naṣr Bahā’ al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 403/1012 | Abū Shujā‘ b. Fīrūz Bahā’ al-Dawla, Sulṭān al-Dawla |

| 412/1021 | Ḥasan b. Fīrūz Bahā’ al-Dawla, Abū ‘Alī Musharrif al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 416/1025 | Shīrzīl b. Fīrūz Bahā’ al-Dawla, Abū Ṭāhir Jalāl al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 435/1044 | Marzubān b. Abī Shujā‘ Sulṭān al-Dawla, Abū Kālījār ‘Imād al-Dīn |

| 440–7/1048–55 | Khusraw Fírūz b. Marzubān ‘Imād al-Din, Abū Nasr |

| 447/1055 | Seljuq occupation of Baghdad |

5. The rulers of the dynasty acknowledged by local chiefs in Oman

| ⊘ by 361/972 | Fanā Khusraw, Abū Shujā‘ ‘Aḍud al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 380/990 | Marzubān, Abū Kālījār Ṣamṣām al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 388/998 | Fīrūz, Abū Naṣr Bahā’ al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 403/1012 | Abū Shujā‘ Sulṭān al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 415–42/1024–50 | Marzubān, Abū Kālījār ‘Imād al-Din |

| 442/1050 | Power seized by a leader of the local Ibāḍīs |

Out of the Daylamī dynasties which formed in the Persian world as the ‘Abbāsid grip over the provinces of the caliphate weakened, the Būyids were the most powerful and ruled over the greatest extent of territories. They began modestly enough as commanders in the army of the successful Daylami condottieri, Mardāwīj b. Ziyār, founder of the Ziyārid dynasty (see below, no. 81). The eldest of the three sons of Būya, ‘Ali, held Iṣfahān at the time of Mardāwīj’s assassination, and shortly afterwards seized the whole of Fars, while Ḥasan held Jibāl and Aḥmad held Kirman and Khūzistān. In 339/945 Aḥmad entered Baghdad, and the ‘Abbāsids began a 110-year period of tutelage under Būyid amīrs (who normally held the title in Iraq of Amīr al-Umarā’ ‘Supreme Commander’), during which the caliphate was to reach its lowest ebb. In the third quarter of the tenth century, Mu‘izz al-Dawla Aḥmad’s son ‘Aḍud al-Dawla united under his rule what had originally been the three Būyid amirates, comprising southern and western Persia and Iraq, even extending his power across the Persian Gulf to Oman, where his successors were acknowledged as suzerains by such local chiefs as the Mukramids (see above no. 52); his reign marks the zenith of Būyid power. ‘Aḍud al-Dawla pursued a vigorously expansionist policy, utilising his armies of Daylamī infantry and Turkish cavalry, in the east against the Ziyārids of Ṭabaristān and Gurgān and against the Sāmānids of Khurasan, and in the west against the Ḥamdānids of Jazīra.

However, a patrimonial conception of power, doubtless stemming from the tribal past of the Daylamis, was strong among the various Būyid princes, with tendencies towards fragmentation apparent when strong rule was relaxed. After ‘Aḍud al-Dawla’s death, there was much civil strife within the dynasty. This disunity allowed petty Kurdish and Daylamī principalities to constitute themselves within the Zagros mountains and in Jibāl, and facilitated Maḥmūd of Ghazna’s annexation of Rayy and much of Jibāl from the Būyids in 420/1029. It then left them weakened in the face of incursions of the Turkmen Oghuz and the westward drive of the Seljuq Ṭoghrïl Beg, who was able to arouse orthodox Sunnī religious and constitutional feeling and claim that he was liberating the western lands or Persia and Iraq from Shī‘ī heretics. Baghdad was occupied in 447/1055, but the Būyid prince in Fars retained power for seven more years until his lands were seized by local Shabānkāra’ī Kurds, only to fall into the Seljuqs’ hands shortly afterwards.

Like most of the Daylamīs, the Būyids were Shī‘īs, probably Zaydīs to begin with and then Twelvers or Ja‘farīs. The traditional Shī‘ī festivals and practices were introduced into their territories, and Shī‘ī scholars laboured at the systema-tisation and intellectualisation of Shī‘ī theology and law, previously somewhat vague and emotional in content. This Shī‘ism may have been in part a manifestation of anti-Arab, pro-Iranian national feeling, with which attempts to provide the Būyids with a respectable genealogy going back to the Sāsānids and the adoption of an ancient Persian imperial title like Shāhānshāh may be connected. The Baghdad caliphs’ material power and resources were inevitably circumscribed by their alleged protectors, yet the Būyids made no attempt to extinguish the caliphate and they showed themselves hostile to their rivals in the west, the Ismā‘īlī Fāṭimids. Culturally, the domination of Shī‘ism in the Būyid territories was accompanied by a wide tolerance of other faiths like Christianity, Judaism and Zoroastrianism, allowing their communities to flourish and bringing about a lively intellectual ferment in the various Būyid provincial capitals; this learning was nevertheless essentially Arabic-centred, and the Būyids evinced little interest in or encouragement of the New Persian literary and cultural renaissance which was beginning in the eastern Persian lands.

Justi, 442; Lane-Poole, 139–44; Zambaur, 212–13 and Table Q; Album, 35–6.

EI2 ‘Buwayhids’ (Cl. Cahen); EIr ‘Buyids’ (Tilman Nagel).

R. Vasmer, ‘Zur Geschichte und Münzkunde von ‘Omān im X. Jahrhundert’, ZfN, 37 (1927), 274–87.

H. Bowen, ‘The last Buwayhids’, JRAS (1929), 229–45.

S. M. Stern and A. D. H. Bivar, ‘The coinage of Oman under Abū Kālījār the Buwayhid’, NC, 6th series, 18 (1958), 147–56.

H. Busse, Chali fund Groβkönig, die Buyiden im Iraq (945–1055), Beirut and Wiesbaden 1969, with genealogical tables at p. 610.

idem, ‘Iran under the Būyids’, in The Cambridge History of Iran, IV, 250–304.

C. E. Bosworth, in ibid., V, 36–53.

76

THE ḤASANŪYIDS OR ḤASANAWAYHIDS

c. 350–406/c. 961–1015

Southern Kurdistan

| c. 350/c. 961 | Ḥasanawayh b. Ḥusayn al-Barzīkānī, Abu ’1-Fawāris, d. 369/979 |

| ⊘ 370/980 | Badr b. Ḥasanawayh, Abu ’1-Najm Nāṣir al-Dīn, d. 405/1014 |

| 404/1013 | Ṭāhir or ẓāhir b. Hilāl b. Badr, in Shahrazūr |

| 405/1014 | Hilāl b. Badr |

| 405–6/1014–15 | Ṭāhir b. Hilāl |

| 406/1015 | Conquest by the ‘Annāzids |

Ḥasanawayh was a chief of the Kurdish Barzīkānī tribe who built up for himself a principality in the region round Qarmāsīn (the later Kirmānshāh). He and his son Badr skilfully maintained their power as vassals of the Būyids (see above, no. 75) by supporting various contenders for power in the struggles between Fakhr al-Dawla of the northern Būyid amirate on the one hand and ‘Aḍud al-Dawla and his successors in Fārs and Iraq on the other. They also achieved contemporary reputations for their just and beneficent rule among a Kurdish people whose very name was synonymous with violence and rapacity. Latterly, however, the Ḥasanūyids were overshadowed by a rival family of Kurdish chiefs, the ‘Annāzids (see below, no. 77), who killed Ṭāhir b. Hilāl and generally replaced the Ḥasanūyids in central Kurdistan. The family only managed to hold on to a few fortresses like that of Sarmāj near Bīsutūn until a descendant of Badr’s died there in 439/1047.

Lane-Poole, 138; Zambaur, 211; Album, 36.

EI2 ‘Ḥasanawayh’ (Cl. Cahen).

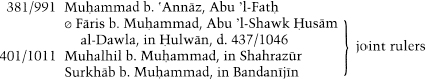

381 to later sixth century/991 to later twelfth century

Southern Kurdistan and Luristān

|

|

| 437– /1046 – | Muhalhil b. Muḥammad, sporadic rule, d. c. 447/c. 1055 |

| 438– /1046– | Sa‘dī or Su‘dā b. Fāris, sporadic rule, d. after 446/1054 |

| 447/1055 | Kurdistan under Seljuq control |

| ? | Surkhāb b. Badr b. Muhalhil, d. 500/1107 |

| 500–?/1107–? | Abū Manṣūr b. Surkhāb |

later sixth century/ |

|

later twelfth century Surkhāb b. ‘Annāz |

|

The ‘Annāzids were another Kurdish line, like the Ḥasanūyids (see above, no. 76), with their power-base in the Shādhanjān tribe. The founder, Abu ’1-Fatḥ Muḥammad, ruled from Ḥulwān, but his three sons and successors ruled in various other parts of southern Kurdistan, maintaining themselves against the Būyids and the Kākūyids (see below, no. 78), but with their dominions suffering increasingly from Oghuz Türkmen incursions led by the Seljuq Ibrāhīm Inal. The history of the ‘Annāzids in these decades is confused and chaotic, for the family had several branches and the territorial extent of their rule was often shifting. After Ṭoghrïl Beg came to Iraq in 447/1055, the sources are largely silent on the ‘Annāzids, except for occasional references which indicate that some members of the family retained a certain amount of power in Kurdistan and Luristān until some time after 570/1174.

Zambaur, 212.

EI2 ‘Annāzids (V. Minorsky); EIr ‘‘Annāzids’ (K. M. Aḥmad).

c. 398–443/c. 1008–51 independent rulers; thereafter, feudatories of the Seljuqs until the mid-sixth/mid-twelfth century

Jibāl and Kurdistan

| ⊘ before 398/before 1008 | Muḥammad b. Rustam Dushmanziyār, Abū Ja‘far ‘Alā’ al-Dawla, in Isfahan |

| ⊘ 433–43/1041–51 | Farāmurz b. Muḥammad,‘Abū Manṣūr Ẓahīr al-Dīn Shams al-Mulk, in Isfahan, d. after 455/1063 |

| 433-c. 440/1041-c. 1048 | Garshāsplb.Muḥammad, Abū Kālījār ‘Alā’ al-Dawla, in Hamadan and Nihāwand, d. 443/1051 |

| ? – 488/? – 1095 | ‘Alī b. Farāmurz,‘Abū Manṣūr Mu’ayyid al-Dawla or ‘Alā’ al-Dawla, in Yazd |

| 488-?536/1095-? 1141 | Garshāsp II,‘Abū Kālījār ‘Alā’ al-Dawla ‘Aḍud al-Dīn |

Succession of the Atabegs of Yazd |

The Kākūyids were one of the petty Kurdish and Daylamī dynasties of the Zagros region which arose when the grip of the Būyids (see above, no. 75) was becoming relaxed, only to lose their independence and be reduced to vassalage by the rising power in Persia of the Seljuqs. Dushmanziyār had been in the service of the Būyids of Rayy, and his son Muḥammad (known as Ibn Kākūya in the sources, explained as being from a Daylamī dialect word for ‘maternal uncle’, since Muḥammad was the maternal uncle of the Būyid Amīr Majd al-Dawla) was by 398/1008 governor of Isfahan. Soon he expanded to Hamadan and into Kurdistan, building up a principality which was of some political significance for a while and forming a court circle which included the philosopher Ibn Slnā (Avicenna), who functioned as his vizier. Ghaznawid expansion into Jibāl after 420/1029 forced him temporarily to submit, but when the Ghaznawids found it difficult to retain these distant conquests he resumed his independence and even occupied Rayy for a while.

The invasions of the Turkmen Oghuz and their flocks changed the political and economic situation of northern Persia and forced the Kākūyids, like other Daylamī and Kurdish powers, on to the defensive. Farāmurz b. Muḥammad was obliged to yield Isfahan to Ṭoghrïl, who after 443/1051 made it the Seljuq capital but awarded Abarqūh and Yazd in compensation for the Kākūyids. His brother Garshāsp I fled from Kurdistan to the Būyids in Fars. With their little niche in central Persia, the later Kākūyids adapted themselves comfortably to the Great Seljuq régime, being frequently linked by marriage to the ruling sultans. After Garshāsp II, the history of the family becomes obscure, but Garshāsp’s daughter was to be linked through marriage to the line of Turkish Atabegs which succeeded in Yazd and lasted until the thirteenth century and the time of the II Khānids (see below, no. 133)

Justi, 445; Lane-Poole, 145; Zambaur, 216–17; Album, 36.

EI2 ‘Kākūyids’ (CE. Bosworth).

G. C. Miles, ‘The coinage of the Kākwayhid dynasty,’ Iraq, 5 (1938), 89–104.

idem, ‘Notes on Kākwayhid coins, ANS, Museum Notes, 9 (1960), 231–6.

C. E. Bosworth, ‘Dailamīs in central Iran: the Kākūyids of Jibāl and Yazd,’ Iran, JBIPS, 8 (1970), 73–95.

c. 19–144/c. 640–761

Gīlān, Rūyān and the Ṭabaristān coastlands, with their centre at Sārī

| c. 19/c. 640 | Gīl b. Gīlānshāh, Gāwbāra, Gīl-i Gīlān Farshwādgarshāh |

| c. 40/c. 660 | Dābūya b. Gāwbāra |

| c. 56/c. 676 | Khurshid I b. Gāwbāra |

| ⊘ 93/712 | FarrukhānIb. Dābūya, Dhu 1-Manāqib, Farrukhān-i Buzurg |

| ⊘ after 110/after 728 | Dādburzmihr b. Farrukhān I |

| 123/741 | Farrukhān II b. Farrukhān I, Farrukhān-i Kūcḥik, Kubālī |

| ⊘ 131–43/749–60 | Khurshīd II b. Dādburzmihr, d. 144/761 |

| 143/760 | ‘Abbāsid conquest of Ṭabaristān |

The Caspian coastlands of Gīlān and of Māzandarān (in earlier Islamic times, Ṭabaristān), and the massive barrier of the Elburz Mountains which separates them from the central plateau of Persia, have always been a region of Persia with a very distinct character of their own. In particular, they have been a refuge area for peoples and ideas, so that ethnic splinter-groups, old or aberrant religious beliefs, ancient languages and scripts, and social ways, have often survived there after they have disappeared from the more accessible and open parts of Persia. Islam was late arriving in the Caspian region, and for several centuries after this time various petty dynasties lingered on there, some with roots in the late Sāsānid past. One of these, the Bāwandids, endured for six or seven centuries until II Khānid times (see below, no. 80), and the Bāduspānids (see below, no. 100) persisted from Seljuq times until the reign of the Ṣafawid Shāh ‘ Abbās I (i.e. until the end of the sixteenth century: see below, no. 148), when the line was suppressed and the Caspian provinces were fully integrated into the rest of the kingdom.

The Dābūyids were a line of Ispahbadhs (lit. ‘military chief, here ‘local prince’) who apparently arose in the south-western Caspian highlands region of Gīlān in late Sāsānid times. They were local governors for the Emperors, and themselves claimed Sāsānid descent, but from the time of Farrukhān I they moved eastwards and also controlled Ṭabaristān at the south-eastern corner of the Caspian lands, residing now at Sārī. The history of the dynasty is largely known from the historian of the Caspian lands, Ibn Isfandiyār, and his information on the succession and chronology of the early Dābūyids must be regarded as only semi-historical. Arabic raids into Ṭabaristān began in the caliphate of ‘Uthmān, but that of the governor of Iraq and the East, Yazid b. al-Muhallab, in 98/716, was the first serious attack. The Dābūyid Khurshīd II aided Abū Muslim against the ‘Abbāsid caliph al-Manṣūr and then the Zoroastrian rebel in Khurasan, Sunbādh. Hence in the caliph undertook the definitive conquest of Ṭabaristān, successfully drove out Khurshīd II and ended the dynasty of the Dābūyids (who, as Zoroastrians, had never accepted Islam; they are included here as precursors of the local Caspian dynasties who did, during the years shortly afterwards, accept the new faith, and as being historically involved with the Islamic caliphs).

Justi, 430; Zambaur, 186.

EI2‘Dābūya’ (B. Spuler); EIR ‘Dabuyids’ (W. Madelung).

H. L. Rabino, ‘Les dynasties du Māzandarān de l’an 50 avant l’Hégire à l‘an 1006 de l’Hégire (572 à 1597–1598) d‘après les chroniques locales’, JA, 228 (1936), 437–43, with a

genealogical table at p. 438.

W. Madelung, in The Cambridge History of Iran, IV, 198–200.

45–750/665–1349

The highlands of Ṭabaristān and Gīlān

1. The line of the Kawusiyya (Ṭabaristān), with their centre at Firrīm

| 45/665 | Bāw, ? Ispahbadh of Ṭabaristān |

| 60/680 | Interregnum of Walash |

| 68/688 | Surkhāb I b. Bāw |

| 98/717 | Mihr Mardān b. Surkhāb I |

| 138/755 | Surkhāb II b. Mihr Mardān |

| 155/772 | Sharwín I b. Surkhāb II |

| before 201/before 817 | Shahriyār I b. Qārin |

| 210/825 | Shāpūr or Ja‘far b. Shahriyār I |

| 210–24/825–39 | Seizure of power by Māzyār b. Qārin b. Wandād-Hurmuzd |

| 224/839 | Qārin I b. Shahriyār I, Abu ‘1-Mulūk |

| 253/867 | Rustam I (? b. Surkhāb) b. Qārin |

| 282/895 | Sharwīn II b. Rustam I |

| 318/930 | Shahriyār II b. Sharwīn II |

| ⊘ c. 353–69/c. 964–80 | Rustam II b. Sharwīn II |

| 358/969 | Dārā b. Rustam II |

| ⊘ c. 376/c. 986 | Shahriyār III b. Dārā |

| 396/1006 | Rustam III b. Shahriyār III |

| 449–66/1057–74 | Qārin II b. Shahriyār III |

| 466/1074 | Disappearance of their rule |

2. The line of the Ispahbadhiyya (Ṭabaristān and Gīlan), with their centre at Sārī

| ⊘ c. 466/c. 1074 | Shahriyār b. Qārin, Husām al-Dawla |

| c. 508/c. 1114 | Qārin b. Shahriyār, Najm al-Dawla |

| 511/1117 | Rustam I b. Qārin, Shams al-Mulūk |

| ⊘ 511/1118 | ‘Alī b. Shahriyār, ‘Alā’ al-Dawla |

| ⊘ c. 536/c. 1142 | Shāh Ghāzi Rustam b. ‘Alī, Nuṣrat al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 560/1165 | Ḥasan b. Shāh Ghāzi Rustam, ‘Alā’ al-Dawla Sharaf al-Mulūk |

| 568/1173 | Ardashīr b. Ḥasan, Ḥusām al-Dawla |

| 602–6/1206–10 | Rustam II b. Ardashīr |

| 606/1210 | Khwārazmian and then Mongol rule in Ṭabaristān |

3. The line of the Kīnkhwāriyya (vassals of the Il Khānids), with their centre at Āmul

The Bāwandids were the longest-lived of the petty Caspian dynasties, with a history extending over some six or seven centuries, a remarkable demonstration of how the region’s isolation from the mainstreams of Islamic Persian life allowed a degree of family continuity unusual in the Islamic world. They claimed descent from one Bāw and traced their genealogy back beyond this to the Sāsānid emperor Kawādh. Their original centre was at Firrīm in the eastern section of the Elburz chain running through Ṭabaristān.

That part of the dynasty’s history which can be reasonably well documented only begins with the Arab invasions of Ṭabaristān in the opening years of the ‘Abbāsid caliphate. This was the time when the Bāwandids and the rival house of the Qārinids were vying for power there, a rivalry which in the ninth century was to end spectacularly in the rebellion and fall of Māzyār b. Qārin (224/839). It was also at this last juncture that the Ispahbadhs at last became definitively Muslim. Subsequently, they opposed the Zaydi Imams in lowland Ṭabaristān, and were involved during the tenth century in the struggles of the Būyids and the Ziyārids (see above, no. 75, and below, no. 81) for control of northern Persia, being linked with both these houses through marriage; it was during the times when they became vassals of the Būyids that the Bāwandids adhered to Twelver Shī’ims.

This first line faded out, and the affiliation to it of the subsequent line is not certain. These Ispahbadhiyya were firmly Twelver Shī’īs. Within a framework of vassalage to the Great Seljuqs, they managed to preserve their local authority; at times they sheltered Seljuq claimants and made high-level marriages with the Seljuqs. The decline of Great Seljuq power in the mid-twelfth century allowed the vigorous and assertive Shāh Ghāzī Rustam to became a major, independent figure in the politics of northern Persia; he combated the Ismā’īlīs of Alamūt (see below, no. 101) and pursued an independent policy aimed at extending his principality south of the Elburz. However, the rising power of the Khwārazm Shāhs (see below, no. 89) in the early years of the thirteenth century brought this line to an end, with direct power exercised in Māzandarān (as Ṭabaristān becomes generally called after the twelfth century).

The Bāwandids were restored after an interval of three decades in the shape of a collateral branch, the Kīnkhwāriyya, who ruled as vassals of the Mongol Il Khānids, with their capital at Āmul, until another local family of Māzandarān, that of Kiyā Afrāsiyāb Chulābl, overthrew them and ended Bāwandid rule for ever.

Justi, 431–2; Sachau, 5–7 nos 3–5; Zambaur, 187–9; Album, 34–5.

EI2‘Bāwand’ (R. N. Frye); EIr ‘Āl-e Bāvand’ (W. Madelung).

H. L. Rabino, Tes dynasties du Māzandarān’, 409–37, with a genealogical table at p. 416.

G. C. Miles, The coinage of the Bāwandids of Ṭabaristān’ in C. E. Bosworth (ed.), Iran and Islam, in memory of the late Vladimir Minorsky, Edinburgh 1971, 443–60.

W. Madelung, in The Cambridge History of Iran, IV, 200–5, 216–18.

319–c. 483/931–c. 1090

Ṭabaristān and Gurgān

| ⊘ 319/931 | Mardāwīj b. Ziyār, Abu ‘1-Hajjāj |

| ⊘ 323/935 | Wushmgīr b. Ziyār, Abū Manṣūr Ẓahir al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 356/967 | Bīsutūn b. Wushmgīr, Abū Manṣūr Ẓahir al-Dawla |

| ⊘ 367/978 | Qābūs b. Wushmgīr, Abu ‘1-Ḥasan Shams al-Ma‘ālī, first reign |

| 371–87/981–97 | Būyid occupation |

| ⊘ 387/997 | Qābūs b. Wushmgīr, second reign |

| ⊘ 402/1012 | Manūchihr b. Qābūs, Falak al-Ma‘ālí |

| 420/1029 | Anūshirwānb. Manūchihr, Abū Kālijār, d. ? 441/1049 |

| 426/1035 | Dārā b. Qābūs, governor for the Ghaznawids in Ṭabaristān and Gurgān) |

| 441/1049 | Kay Kāwūs b. Iskandar b. Qābūs, ‘Unṣur al-Ma‘āli, d. c. 480/c. 1087 |

| c. 480-c. 483/ |

|

| c. 1087-c. 1090 | Gīlān Shāh b. Kay Kāwūs |

Seljuq governors in lowland Ṭabaristān and Gurgān |

In the early years of the tenth century, the backward and remote highland region of Daylam at the south-western corner of the Caspian Sea sent forth large numbers of its menfolk as soldiers of fortune in the armies of the caliphate and elsewhere. The Ziyārids arose out of one of the fiercest of these condottieri, Mardāwīj b. Ziyār, who was descended from the royal clan of Gīlān. On the rebellion of the commander Asfār b. Shīrūya, a general in the Sāmānid armies, Mardāwīj took the opportunity to seize most of northern Persia. His power soon extended as far south as Iṣfahān and Hamadān, but in he was murdered by his own Turkish slave troops and his transient empire fell apart. Only in the eastern Caspian provinces did his brother Wushmgīr retain a foothold, acknowledging the Sāmānids as his overlords, and in the ensuing decades the Ziyārids were closely involved with the Sāmānid-Būyid struggle for control of northern Persia. In Qābūs b. Wushmgīr, the dynasty produced an outstanding figure of the florescence of Arabic learning in Khurasan and the East, which his seventeen-year exile in Nishapur, while the Būyids occupied his lands, facilitated. A point which marks off the Ziyārids from almost all the other DaylamI dynasties of the time was their adherence, at least latterly, to SunnI and not Shī‘ī Islam.

In the early eleventh century, the Ziyārids had to recognise the overlordship of the new and vigorous power of the Ghaznawids (see below, no. 158), and the two families became linked by marriage alliances. The incoming Seljuqs appeared in Gurgān in and took over the coastlands, but the Ziyārids seem to have survived, in obscure circumstances as vassals of the Seljuqs, in the highland region. One of the last amirs, Kay Kāwūs b. Iskandar, achieved fame as the author of a celebrated ‘Mirror for Princes’ in Persian, the Qābūs-nāma, named after his illustrious grandfather. His son Gīlān Shāh was the last known member of his line to rule. He was apparently overthrown by the Nizārī Ismā’īlīs, who were spreading their power through the Elburz region (see below, no. 101), and with him the dynasty disappears from history.

Justi, 441; Lane-Poole, 136–7; Justi, 441; Zambaur, 210–11; Album, 35.

EI1 ‘Ziyārids’ (Cl. Huart); EI2 ‘Mardāwīdj’ (C. E. Bosworth). (The earlier acounts of the dynasty are all confused and unreliable in their chronology of the later Ziyārids.)

CE. Bosworth, ‘On the chronology of the later Ziyārids in Gurgān and Ṭabaristān’, Der Islam, 40 (1964), 25–34, with a genealogical table at p. 33.

G. C. Miles, ‘The coinage of the Ziyārid dynasty of Ṭabaristān and Gurgān’, ANS, Museum Notes, 18 (1972), 119–37.

W. Madelung, in The Cambridge History of Iran, IV, 212–16.