SIX

The Arabian Peninsula

40

THE CARMATHIAN OR QARMATl RULERS OF THE LINE OF ABŪ SA‘ĪD AL-JANNĀBĪ

c. 273–470/c. 886–1078

Originally in the Syrian Desert region and Iraq, then in eastern Arabia

| 273/886 or 281/894 | al-Hasan b. Bahrāin al-Jannābī, Abū Sa’īd |

| 301/913 | Sa‘īd b. Abī Sa‘īd al-Jannābī, Abu 1-Qāsim |

| 305/917 | Sulaymān b. Abī Sa’īd, Abū Tahir |

| 332/944 |

|

| ⊘ (by 351/962 | al-Ḥasan b. Aḥmad b. Abī Sa‘īd, Abū ‘Alī al-A‘ṣam, in Syria, d. 366/977) |

| 361/972 | Yūsuf, Abū Ya’qūb, d. 366/977 |

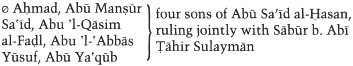

| 366/977 | joint rule of six of Abū Sa’īd al-Ḥasan’s grandsons, al-sāda al-ru’ asā’ |

| 470/1078 | Conquest of al-Aḥsā by the ‘Uyūnid family of the Banū Marra |

The Carmathian or Qarmatī movement was one of the manifestations of messianic, radical Shfī‘sm arousing out of the Ismā‘llism which took shape in the later eighth and ninth centuries, towards the end of which period a dā‘ī or missionary called Harndān Qarmat allegedly worked in Iraq. At the opening of the tenth century, the Syrian Desert fringes were agitated by the revolutionary movement of Zakaruya or Zakrawayh until it was suppressed in 293/906. This Carmathian da‘wa had split from the main Ismā‘īlī group in Syria in 186/899, unwilling to recognise the claims of the Fātimids (see above, no. 27), with the ‘Old Believer’ Carmathians now claiming to represent the claims of Ismā‘īl, son of the Sixth Imām Ja‘far al-Ṣādiq, as conveyed through Ismā‘īl’s son Muḥammad; the split with the Fāṭimids was never to be really healed.

Instead, the Carmathians established themselves in lower Iraq, where the Zanj or black slave rebellion of the later ninth century had left behind much social and religious discontent, and among the Bedouin of north-eastern Arabia, in the region of al-Aḥsā or Bahrayn. Here, Abū Sa‘ld al-Jannābī built up an enduring principality, often described later as that of the Abū Sa‘īdīs. The organisation of the Carmathian community there was sufficiently different from the norm of Islamic states at that time to excite the deep suspicion of orthodox Sunnī observers. It seems that there were tentative experients with the communal ownership of property and goods, soon abandoned; in any case, the economic foundation of the Carmathian principality rested on black slave labour. The rulers of Abū Sa‘īd’s family were backed by a council of elders, the ‘Iqdāniyya ‘those who have power to bind [and loose]’; contemporary travellers and visitors to al-Aḥsā praised the justice and good order prevailing there.

The relations of the Carmathians, in their earlier, activist phase, with the Fāṭimids continued to be tense. They raided into Iraq and as far as the coast of Fars (Fārs) and harried the fringes of Syria and Palestine; they had adherents in Yemen, and at one point conquered Oman (‘Umān). Their greatest coup of all was in 317/930 carrying off the Black Stone from the Ka‘ba in Mecca, considering it to be a mere object of superstitious reverence, it was twenty years later before, at the Fāṭimid caliph al-Manṣūr’s pleading, they agreed to replace it. Towards the end of the tenth century, the Carmathians grew more moderate in tone, and their principality evolved into something like a republic, with a council of elders in which the house of Abū Sa‘íd al-Jannābī was still notable. It seems to have lasted thus until the later eleventh century and the end of the Carmathian state as an independent entity through joint operations by a Seljuq-Abbāsid army from Iraq and a local Bedouin chief, founder of the subsequent line of ‘Uyūnids in eastern Arabia. The surviving Carmathians probably then gave their adherence to the Fāṭimids, but descendants of Abū Sa‘īd, called sayyids, were to be found in al-Aḥsā two or three centuries later.

Ismā‘īlism has long disappeared from eastern Arabia, but it may have left a distant legacy in the present existence there, within modern Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Bahrayn Island, of significant Twelver Shī‘ī communities.

Coins of the Carmathians are extant from the second half of the tenth century, but seem to have been minted by their governors and commanders on the borders of Palestine and Syria rather than in al-Aḥsā.

Zambaur, 116; Album, 20.

EI2 ‘Isma‘īliyya’, ‘Ḳarmati’ (W. Madelung).

M. J. de Goeje, ‘La fin de l’empire des Carmathes du Bahraïn’, JA, 9th series, 5 (1895), 1–30.

W. Madelung, ‘Fatimiden und Baḥrainqarmaten’, Der Islam, 34 (1959), 34–88, English tr. The Fatimids and the Qarmaṭīs of Bahrayn’, in F. Daftary (ed.), Medieval Isma‘ili History and Thought, Cambridge 1996, 21–83.

George T. Scanlon, ‘Leadership in the Qarmatian sect’, BIFAO, 59 (1959), 29–48, with a provisional genealogical table at p. 35.

François de Blois, ‘The ‘Abu Sa‘īdīs or so-called “Qarmatians” of Bahrayn’, Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, 16 (1986), 13–21.

F. Daftary, The Ismā‘ills, their History and Doctrines, Cambridge 1990, 103–34, 160–5, 17–6, 220–2.

H. Halm, Shiism, Edinburgh 1991, 166–77.

284–1382/897–1962

Generally in Highland Yemen, with seats in Ṣa‘da or Ṣan‘ā‘; in the twentieth century uniting all Yemen

1. The early period: the Rassid line

al-Qāsim b. Ibrāhīm al-Ḥasanī al-Rassī, d. 246/860 in Medina |

|

al-Ḥusayn b. al-Qāsim, also resident in Medina |

|

| ⊘ 284/897 | Yaḥyā b. al-Ḥusayn, al-Hādī ilā ‘l-Ḥaqq, in Ṣa’‘da |

| 298/911 | Muḥammad b. Yaḥyā, al-Murtaḍā, d. 310/922 |

| ⊘ 301/913 | Aḥmad b. Yaḥyā, al-Nāṣir |

| 322/934 | Yaḥyā b. Aḥmad, d. 345/956 |

| 358/968 | Yūsuf b. Yaḥyā, al-Manṣūr al-Dāī, d. 403/10122 |

| 389/998 | al-Qāsim b. ‘Alī al-‘Iyāní, Abu l-Ḥusayn al-Manṣūr, d. 393/1003 |

| 401/1010 | al-Ḥusayn b. al-Qāsim, al-Mahdī, d. 404/1013 |

| 413/1022 | Ja‘far b. al-Qāsim |

| 426/1035 | al-Ḥasan b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān, Abū Hāshim d. 431/1040 |

| 437/1045 | Abu l-Fath b. al-Ḥusayn, al-Daylamī al-Nāṣir |

Period of weakness for the Zaydī Imāms, with the Sulayhids capturing Ṣan‘ā‘ in 454/1062 and the Hamdānid line of Ḥātim h. al-Ghashīm ruling there in 492/1099 |

|

| ? | Ḥamza b. Abi Hāshim, d. 458/1066 |

| 458/1067 | al-Fāḍil b. Ja‘far, d. 460/1068 |

| ? | Muḥammad b. Ja‘far, d. 478/1085 |

| 511/1117 | Yaḥyā b. Muḥammad, Abū Ṭālib |

| 531/1137 | ‘Alīb. Zayd |

| 532/1138 | Aḥmad b Sulaymān, al-Mutawakkil, d. 566/1171 |

| 566/1171 | Hamdānid occupation of Ṣan’ā’ |

| 569–626/1174–1229 | Ayyūbid conquest and occupation of Yemen |

| ⊘ 583/1187 | ‘Abdallāh b. Ḥamza, al-Manṣūr, d. 614/1217 |

| 614/1217 | Yaḥyā b. Ḥamza, Najm al-Dīn al-Hādī ilā ‘l-Ḥaqq, in Ṣa‘da |

| 614/1217 | Muḥammad b. ‘Abdallāh, ‘Izz al-Dln al-Nāṣir, in the southern districts until 623/1226 |

| 626– 11229– | Rasūlid rule established in Ṣan‘ā’ |

| ⊘ 646–56/1248–58 | Aḥmad b. al-Ḥusayn, al-Mahdī al-Mūṭi’ |

The Zaydī imamate held by members of a collateral branch |

2. The more recent period: the Qāsimid line

The Zaydīs are a moderate branch of the Shī‘a, and they held that the caliph ‘Alī had been designated by the Prophet Muḥammad as Imām of the Community of the Faithful through his personal merits rather than through a divine ordinance or nass, and also that the Fifth Imām of the Shī‘a should rightfully have been not Muḥammad al-Bāqir but his brother Zayd, martyred during the reign of the Umayyad caliph Hishām (see above, no. 2). The descendants and partisans of Zayd later won over by their propaganda the Persian peoples of Daylam and the south-western coastlands of the Caspian Sea, a region sufficiently inaccessible (and, indeed, hardly at that time Islamised) for this work to be carried out without impediment.

The region of Yemen in the south-western corner of the Arabian peninsula was likewise remote from control by the ‘Abbāsid caliphs, and here Tarjumān al-Din al-Qasim b. Ibrahim Ṭabāṭabā, a descendant of the Second ‘Alid Imām al-Hasan, came from Medina and established himself during al-Ma’mūn’s caliphate; it was he who founded the legal and theological school of the Zaydiyya. The name ‘Rassids’, conveniently used by Western scholars to designate the ensuing line of Imāms, is geographical in origin and derived from al-Rass, a place in the Hijāz,; the term is not commonly used by indigenous Yemeni historians.

The Rassids thus settled at Ṣa’da in northern Yemen, and maintained themselves there against the local Khārījis, Qarmaṭīs and other opponents of their rule. As well as possessing Ṣa’da, they frequently held Ṣan‘ā’ also. Over the next century, Yemen remained the centre of the Zaydi da’wa, with missionaries going to the Caspian provinces and to other parts of the Islamic world. Ṣan‘ā’ was taken by the Ṣulayhids (see below, no. 45) in the second half of the eleventh century, and in the next century it was held by Arab chiefs of the Banū Hamdān (see below, no. 47) for fifty years; only briefly were Zaydī fortunes restored under Aḥmad b. Sulaymān, al-Mutawakkil, a descendant of the tenth-century Imām Aḥmad b. Yaḥyā, al-Nāsir. The Ayyūbid conquest of Yemen in 569/1174 and their domination there for over half a century (see above, no. 30, 8) considerably restricted the authority of the Imāms; they revived somewhat under the first Rasūlid rulers of Yemen (see below, no. 49), until internal disputes and civil strife brought about the eclipse of their power in Yemen.

After this time, the names of various Imāms are known, but the succession seems to have been interrupted by the intrusion of several Imāms from other Ḥasanid lines and of various claimants and counter-Imāms. A more definitely-known sequence appears after around 1000/1592 with the line of al-Qāsim b. Muḥammad. Before this, Yemen had been conquered by the Turks, with Özdemir Pasha entering San‘ā’ in 954/1547, after which Yemen became a province of the Ottoman empire, with the Zaydī Imāms recognising Ottoman suzerainty and left with considerable internal freedom of action. But the Turkish yoke was thrown off by 1045/1635, the Imāms having been reinstalled at San‘ā’ after 1038/1629. The internal history of Yemen over the next two and a half centuries continued to be confused until the Ottomans returned in the later nineteenth century to ‘Asīr, the region immediately to the north of Yemen, and then in 1288/1871 took San‘ā’. The hold of the Zaydī Imāms on the countryside of highland Yemen remained, however, firm, and on occasion they occupied San‘ā’ temporarily. The Turks left Yemen at the end of the First World War, and the Imāms were able to impose their authority over the whole country and enjoy an internationally-recognised independence. But a closed society and a traditional type of autocratic rule became increasingly difficult to maintain after the Second World War, and in 1962 a military coup brought with it the proclamation of a republic. A protracted and bloody civil war followed, until in 1970 the rule of the Hamid al-Dīn family was replaced by a coalition republican régime.

Sachau, 22 no. 45; Zambaur, 122–4 and Table B.

EL1 ‘Zaidīya’ (R. Strothmann); EL2 ‘Ṣan‘ā’’ (G. R. Smith).

H. C. Kay, Y aman: Its Early Mediaeval History, London 1892, with a detailed genealogical table at p. 302.

‘Abd al-Wāsi‘ b. Yaḥyā al-Wās‘ī Furjat al-humūm wa ‘1-huzn flhawddith wa-ta’rlkh al-Yaman, Cairo 1346/1927–8.

Ramzi J. Bikhazi, ‘Coins of al-Yaman 139–569 AH.’, al-Abhāth, 23 (1970), 17–127.

G. R. Smith, The Ayyūbids and Early Rasūlids in the Yemen (567–694/1173–1295), London 1974–8, II, 76–81, with a list of Imāms and a genealogical table at pp. 76–7, 81.

203–409/818–1018

Yemen, with their capital at Zabīd

| 203/818 | Muḥammad b. Ziyād |

| 245/859 | Ibrāhīm b. Muḥammad |

| 283/896 | Ziyād b. Ibrāhīm |

| 289/902 | (Ibn) Ziyād |

| ⊘ 299/911 | Isḥāq b. Ibrāhīm, Abu ’l-Jaysh |

| 371/981 | ‘Abdallāh or Ziyād (?) b. Isḥāq |

| 402–9/1012–18 | Ibrāhīm or ‘Abdallāh b. ‘Abdallāh |

| 409/1018 | Succession of the Ziyādids’ slave ministers, including the Najāḥids, in the northern territories of the Ziyādids |

The founder of this line, Muḥammad b. Ziyād, claimed descent from the great Umayyad governor of Iraq, Ziyād b. Abīhi, but such a connection is speculative. He was appointed by the‘Abbāsid caliph al-Ma’mūn as governor of Yemen, in the hope of restraining Shf I dissent there, and the Ziyādids always recognised the overlordship of Baghdad. Muḥammad’s centre of power was Zabid in Tihāma or coastal lowlands of Yemen, and he managed to extend his authority eastwards into Hadramawt and over some parts of highland Yemen, although the Yu‘firids (see below, no. 43) eventually established themselves in Ṣan‘ā’. The subsequent Ziyādids were threatened by the Yu‘firids and other local potentates, and only with the long reign of Abu ’1-Jaysh Isḥāq did Ziyādid fortunes revive somewhat. The last Ziyādids, whose dates are uncertain, were really fainéants, and in the early eleventh century power passed in Zabīd to their black Habashī slave ministers, one of whom was to found the dynasty of the Najāḥids (see below, no. 44).

Lane-Poole, 90–1; Zambaur, 115; Album, 26.

EI1 ‘Ziyādis’ (R. Strothmann).

H. C. Kay, Y aman: Its Early Mediaeval History, 2–18, 234ff.

Ramzi J. Bikhazi, ‘Coins of al-Yaman 139–569 A.H.’, 64ff.

G. R. Smith, in W. Daum (ed.), Yemen: 3000 Years of Art and Civilisation in Arabia Felix, Innsbruck n.d. [c. 1988], 130, 138, with a list of rulers.

232–387/847–997

Yemen, with their centres at Ṣan‘ā’ and Janad

| 232/847 | Yu‘fir b. ‘Abd al-Rahmān al-Hiwāll al-Himyarí |

| 258/872 | Muḥammad b. Yu‘fir, d. 269/882 |

(Ibrāhīm b. Muḥammad, Abū Yu‘fir, as deputy ruler) |

|

| 269/882 | Ibrāhīm b. Muḥammad, as sole ruler, d. 273/886 |

| 273/886 | Period of confusion |

| c. 285/c. 898 | As‘ad b. Ibrāhīm, Abū HasṢan, first reign |

Period of confusion, with power in Ṣan‘ā‘ seized at times by the Zaydī Imāms and pro-Fāṭimid chiefs |

|

| ⊘ 303/915 | As‘ad b. Ibrāhīm, second reign |

| 332/944 | ? Muḥammad b. Ibrāhīm |

| 344–87/955–97 | ‘Abdallāh b. Qahtān, with his power disputed |

| 387/997 | The Yu‘firids reduced to the status of petty, local chiefs |

In the mid-ninth century, Yu‘fir b. ‘Abd al-Rahmān assrted his independence of the ‘Abbāsid governors in the Yemen highlands, occupying Ṣan‘ā‘ and Janad and becoming the first local dynasty to achieve power there. His family came from Shibām to the north-west of Ṣan‘ā‘, and claimed a distant descent from the Tubba‘ kings of pre-Islamic times. Yu‘fir was still, however, careful to maintain his own allegiance to the ‘Abbāsid caliphs. Subsequent members of the family became involved with rival powers in confused struggles for the control of Ṣan‘ā‘ and northern Yemen; a new element here was the arrival in 284/897 of the Zaydī Imāms (see above, no. 41) and, shortly afterwards, the appearance of the Qarmatis, supporters of the Fātimids (see above, nos 27, 40). Relative stability was achieved under As‘ad b. Ibrāhīm, but after his death the family was rent by dissensions and by 387/997 lost their ruling power, though apparently surviving in Yemen as obscure, local lords.

Lane-Poole, 91; Zambaur, 116;

EI1 ‘Ya‘fur b. Abd al-Rahmān‘ (R. Strothmann).

H. C. King, Yaman: Its Early Mediaeval History, 5–6, 223ff.

H. F. al-Hamdānl and H. S. M. al-Juhanī, al-Ṣulayḥiyyūn wa ‘1-ḥaraka al-Fāṭimiyya fi ‘l-Yaman, with a genealogical table at p. 333.

G. R. Smith, in W. Daum (ed.), Yemen: 3000 Years of Art and Civilisation in Arabia Felix, 130–1, 138.

412–553/1022–1158

Yemen, with their capital at Zabīd

| ⊘ 412/1022 | Najāh, al-Mu‘ayyad Nāsir al-Dīn |

| c. 452/c. 1060 | Sulayhid occupation of Zabīd |

| 473/1081 | Sa‘īd b.Najāh, al-Aḥwal, first reign |

| 475/1083 | Ṣulayhid revanche |

| 479/1086 | Sa‘īd b. Najāh, second reign |

| ⊘ 482/1089 | Jayyāsh b. Najāh, Abū Tāmi |

| c. 500/c. 1107 | Fātik I b. Jayyāsh |

| 503/1109 | al-Manṣūr b. Fātik I |

| 518/1124 | Fātik II b. al-Manṣūr |

| 531/1137 | Fātik III b. Muḥammad |

| c. 553/c. 1158 | Fdtik III deposed by the Zaydī Imām, and Zabīd seized by the Mahdids in 554/1159 |

With the demise of the Ziyādids (see above, no. 42), one of their black Ḥabashī viziers, Najāḥ, managed to kill a rival and establish himself in Zabīd as an independent ruler, acquiring honorifics from the ‘Abbāsid caliph, whom he acknowledged, and extending his dominion northwards through Tihāma. Najāḥ and his successors, like the Ziyādids before them, imported into Yemen contingents of Abyssinian military slaves to support their power, thereby contributing to the mixture of races to be found until today in lowland Yemen. Sa‘id b. Najāḥ was on more than one occasion dispossessed by the Ṣulayhids (see below, no. 45), and al-Manṣūr b. Fātik I reigned as one of their vassals. The Najāḥids of the twelfth century ruled amid growing confusion and under increasing pressure, latterly from the Mahdids (see below, no. 48), and despite the deposition of Fātik III b. Muḥammad as the price of military help from the Zaydī Imām Aḥmad b. Sulaymān al-Mutawakkil, the Mahdids entered Zabīd in 554/1159.

Lane-Poole, 92–3; Zambaur. 117–18; Album, 26.

EI2 ‘Nadjāḥids‘ (G. R. Smith).

H. C. Kay, Yaman: Its Early Mediaeval History, 14ff.

H. F. A. al-Hamdani and Ḥ. S. M. al-Juhanī, al-Ṣulayḥiyyūn wa ‘l-haraka al-Fāṭimiyya fi ‘1-Yaman, with a genealogical table at p. 339.

G. R. Smith, The Ayyūbids and Early Rasūlids in the Yemen (567–694/1173–1295), II, 559.

idem, in W. Daum (ed.), Yemen: 3000 Years of Art and Civilisation in Arabia Felix, 131– 2, 138.

439–532/1047–1138

Yemen, with their capital at Ṣan‘ā‘ and then at Dhū Jibia

| ⊘ 439/1047 | ‘Alī b. Muḥammad al-Ṣulayḥi, Abū Kāmil al-Dā‘ī |

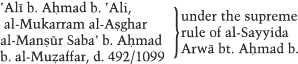

| ⊘ 459/1067 or 473/1080 | Aḥmad b. ‘Alī, al-Mukarram |

| ⊘ 467/1075 or 479/1086 |

|

| c. 484/c. 1091 | |

| ⊘ 492–8532/1099–1138 | al-Sayyida Arwā bt. Aḥmad |

| 532/1138 | Power assumed by the Zuray‘ids of Aden |

As well as becoming, because of its remoteness from the centre of the caliphate in Iraq, a centre for Zaydī Shī‘sm (see above, no. 41), Yemen also proved fertile ground for the Ismā‘īlī Shī‘ī da‘wa, and Carmathian or Qarmaṭī activity (see above, no. 40) is mentioned there from the early tenth century onwards. Once the Fatimids became established in Egypt in the second half of the tenth century (see above, no. 27), with the Holy Cities of the Hijāz acknowledging the new caliphs in Cairo, relations between Egypt and Yemen became close.

The Ṣulayhids ruled in Yemen as adherents of Ismā‘īlism and as nominal vassals of the Fātimids.‘ Alī b. Muḥammad, a member of the South Arabian tribe of Harndan and the son of a local Shāffi‘ī qādī or judge, became the khalifa or deputy of the chief Fātimid dffi in Yemen, Sulaymān b.‘ Abdallāh al-Zawahl, and was thus able to set up a principality in the Yemen highlands. He defeated the Abyssinian slave dynasty of the Najāḥids of Tiharna (see above, no. 44); by 455/1063 he had captured Ṣan‘a’ from the Zaydī Imāms and invaded the Hijāz; and in the next year, he took Aden from the Banū Ma‘n. Under his son al-Mukarram Aḥmad, the Ṣulayhid dominions reached their maximum extent. Yet these conquests could not be held beyond the eleventh century. The Najāḥids revived, Aden was usually independent, and the Zaydī Imāms remained at their centre of Sa‘da in northern Yemen. From the latter part of Aḥmad’s reign until her own death in 532/1138, effective authority was exercised by his capable and energetic consort, al-Sayyida Arwā. It was she who moved the Ṣulayhid capital to Dhū Jibia, controlling from there southern Yemen and Tihāma in a reign of some brilliance as the ‘Second Bilqis’.

After her death at the advanced age of 92, power passed to the Zuray‘ids, who were to hold it until the advent in 569/1174 of the Ayyūbid Turan Shāh (see above, no. 30, 8), although some Ṣulayhid princes continued to hold fortresses in Yemen down to the end of the twelfth century.

Lane-Poole, 94; Zambaur, 118–19 (both very inaccurate); Album, 26.

EI2 ‘Ṣulayḥids‘ (G. R. Smith).

H. C. Kay, Y aman: Its Early Mediaeval History, 19–64, with a detailed genealogical table at p. 335.

H. F. A. al-Hamdani and H. S. M. al-Juhanī, al-Ṣulayḥiyyūn wa ‘l-haraka al-Fdtimiyya fi‘l-Yaman, with a detailed genealogical table at p. 335.

Ramzi J. Bikhazi, ‘Coins of al-Yaman 139–569‘, 77ff.

G. R. Smith, in W. Daum (ed.), Yemen: 3000 Years of Art and Civilisation in Arabia Felix, 132, 138.

46

THE ZURAY‘IDS OR BANU ‘L-KARAM

473–571/1080–1175

Southern Yemen, with their capital at Aden

| 473/1080 | al-‘Abbas b. al-Mukarram or al-Makram or al-Karam b. al-Dhi‘b and al-Mas‘ūd b. al-Mukarram, joint vassals of the Ṣulayhids |

| 477/1084 | al-Mas‘ūd b. al-Mukarram and Zuray‘ b. al-‘Abbās, joint rulers |

| 504–32/1110–38 | Confused period of rivalry between the two branches of the family, the sons of al-Mas‘ūd and the sons of Zuray*: rule at unspecified dates of Abu ‘l-Su‘ūd b. Zuray‘ and Abu ‘1-Ghārāt b. al-Mas‘ūd, ⊘ Saba‘ b. Abi ‘l-Su‘ūd and Muḥammad b. Abi ‘1-Ghārāt, and then ‘Alī b. Muḥammad |

| c. 532/c. 1138 | Saba‘ b. Abi ‘l-Su‘ūd, sole ruler in Aden, d. 533/1139 |

| 533/1139 | ‘Ali b. Saba‘, al-A‘azz (? al-Agharr) |

| ⊘ 534/1140 | Muḥammad b. Saba‘, al-Mu‘azzam |

| ⊘ c. 548/c. 1153 | ‘Imrān b. Muḥammad, d. 561/1166 |

| 561/1166 | Rule of ḥabashī viziers, including fawhar al-Mu‘azzami as regent for ‘Imraris young sons |

| 571/1175 | Ayyūbid conquest of Aden |

The Zuray‘ids belonged to the Jusham branch of the Banū Yarn, and were, like the Ṣulayhids (see above, no. 45), partiṢans of the Ismā‘īliyya, acknowledging the overlordship of the Fāṭimids. Their fortunes came from the Ṣulayhid Aḥmad al-Mukarram‘s driving out the Banū Ma‘n from Aden and his then installing the two brothers al-‘ Abbās and al-Mas‘ūd as joint rulers there in return for their services to the Fātimid cause. They paid tribute to the Ṣulayhid queen, al-Sayyida Arwā, until, when she was distracted by internal problems after al-Mukarram Aḥmad‘s death in 484/1091, the two cousins Abu ‘1-Ghārāt and Zuray‘ (after whom the dynasty is usually named, though some Yemeni historians use the designation Banu ‘1-Karam for the family) threw off Ṣulayhid control. Henceforth, the Zuray ‘ids ruled over their principality around Aden as, in effect, an independent power, while still under the distant overlordship of the Fāṭimids.

The ensuing decades were, however, filled with dispute and civil warfare between the two branches of the family, the descendants of al-Mas‘ūd on one side and those of al-‘ Abbās and Zuray‘ on the other. The names of successive rulers are known, but not the exact dates when they exercised power. It was not until c. 532/c. 1138 that Saba‘ b. Abi ‘1-Su‘ūd b. Zuray‘ managed to impose a unified authority over the region of Aden, and this authority henceforth remained within his branch of the family. A marriage alliance with al-Sayyida Arwā brought to the Zuray‘ids various Ṣulayhid towns and fortresses, but when Tmrān, head of the dynasty and chief da‘i in Yemen, died, his young sons came under the tutelage of Abyssinian slave viziers. The Ayyūbids occupied Aden in 5 71 /1175 (see above, no. 30, 8) and effectively ended the independent power of the Zuray‘ids.

Lane-Poole, 97; Zambaur, 117; Album, 26.

H. C. Kay, Y aman: Its Early Mediaeval History, 158–61, 307–8, with a genealogical table at p. 307.

Ramzi J. Bikhazi, ‘Coins of al-Yaman 139–569 A.H/, 102ff.

G. R. Smith, The Ayyūbids and the Early Rasūlids in the Yemen, II, 63–7, with a genealogical table at p. 63.

idem, in W. Daum (ed.), Yemen: 3000 Years of Art and Civilisation in Arabia Felix, 133, 138, with a list at p. 138.

492–570/1099–1174

Northern Yemen, with their capital at Ṣan‘ā

1. The first line of the Banū Ḥātim

| 492/1099 | Hātim b. al-Ghashim al-Hamdānī |

| 502/1109 | ‘Abdallāh b. Hātim |

| 504–10/1111–16 | Ma‘n b. Hātim |

2. The line of the Banu ‘1-Qubayb

| 510/1116 | Hishām b. al-Qubayb b. Rusaḥ |

| 518/1124 | al-Humās b. al-Qubayb |

| 527–33/1132–9 | Ḥātim b. al-Ḥumās |

3. The second line of the Banū Ḥātim

| 533/1139 | Ḥātim b. Aḥmad, Hamid al-Dawla |

| 556–70/1161–74 | ‘Alī b. Ḥātim, al-Waḥīd |

| 570/1174 | Ayyūbid conquest of Ṣari ā‘ |

This dynastic title includes three short lines, all stemming from the tribe of Hamdān, the first two of which were probably adherents of the Fāṭimids and the third line certainly so. Hātim b. al-Ghashim, a powerful tribal chief, took over Ṣan‘ā‘ when in 492/1099 the Ṣulayhids lost effective control of the city (see above, no. 45). Subsequently, Hamdāni tribal discontent led to the deposition of Ma‘n and the end of the first line, and the coming to power of the sons of al-Qubayb, forming the second line.

However, when the sons of Hātim b. al-Humās fell into dissension after his death, the tribal leaders of Hamdān raised to power Hātim b. Aḥmad, who became the greatest leader of the dynasty, defending Ṣan‘ā‘ against the Zaydī Imām Aḥmad b. Sulaymān al-Mutawakkil. His line succeeded in retaining control of much of northern Yemen and in 569/1174 drove back the Mahdids (see below, no. 48) from Aden. Like other Yemeni lines, they were however threatened by the arrival of the Ayyūbids, who entered Ṣan‘ā‘ in 570/1174 and took it over (see above, no. 30, 8), although Hamdāni tribal elements continued to be a factor in the military history of northern Yemen for at least the next twenty years.

Lane-Poole, 94; Zambaur, 119.

EI2 ‘Hamdānids‘ (C. L. Geddes).

G. R. Smith, The Ayyūbids and Early Rasūlids in the Yemen, II, 68–75, with a genealogical table at pp. 68–9.

idem, in W. Daum (ed.), Yemen: 3000 Years of Art and Civilisation in Arabia Felix, 133–4, 138, with a list of rulers at p. 138.

554–69/1159–73

Yemen, with their capital at Zabīd

| 531/1137 | ‘Alī b. Mahdi al-Ru‘ayni al-Himyari, Abu ‘1-Hasan, with his own da‘wa in Tihama, 554/1159 in Zabīd |

| 554/1159 | Mahdi b. ‘Alī (? jointly with his brother ‘Abd al-Nabi) |

| ⊘ 559–69/1163–74 | ‘Abd al-Nabi b. ‘Ali, k. 571/11762 |

| 569/1174 | Ayyūbid capture of Zabīd |

‘Alī b. Mahdi traced his ancestry back, like so many other Yemeni leaders, to the pre-Islamic Tubba‘ kings. He acquired a reputation in Tihāma as the preacher of an ascetic and rigorist Islamic message, although it does not seem correct to describe him – somewhat anachronistically, anyway – as a Khāriji. ‘Alī designated his followers Ansar and Muhājirūn, and with them he began a series of violent attacks, including on the by now declining Najāḥids (see above, no. 44), finally capturing Zabīd and toppling the older dynasty. The expansionary ambitions of ‘ Alī and his sons led them into a series of attacks in both lowland Yemen, including on Aden, and in the southern part of the highlands, including Ta‘izz. Mahdid excesses may have been one of the factors inducing the Ayyūbid Turan Shāh to intervene in Yemen (see above, no. 30, 8). At all events, the Ayyūbid army speedily defeated the Mahdids, and in 571/1176 ‘Abd al-Nabi and one of his brothers were executed by the Ayyūbids after an apparent Mahdid attempt to regain Zabīd.

Lane-Poole, 96; Zambaur, 118; Album, 26.

EI2 ‘Mahdids‘ (G.R. Smith).

H. C. Kay, Yaman: Its Early Mediaeval History, 124–34.

G. R. Smith, The Ayyūbids and Early Rasūlids in the Yemen, II, 56–62, with a genealogical table at p. 56.

idem, in W. Daum (ed.), Yemen: 3000 Years of Art and Civilisation in Arabia Felix, 134–5, 138, with a list of rulers at p. 138.

626–858/1228–1454

Southern Yemen and Tihāma, with their capital at Ta‘izz

| ⊘ 626/1229 | al-Malik al-Manṣūr ‘Umar I b. ‘Alī b. Rasūl, Nūr al-Dīn al-Ghassani |

| ⊘ 647/1250 | al-Malik al-Muzaffar Yūsuf I b. ‘Umar I, Shams al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 694/1295 | al-Malik al-Ashraf ‘Umar II b. al-Muzaffar, Abu ‘1-Fath |

Mumahhid al-Dīn |

|

| ⊘ 696/1296 | al-Malik al-Mu‘ayyad Dāwūd b. Yūsuf I, Hizabr al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 721/1321 | al-Malik al-Mujāhid ‘Alī b. Dāwūd, Sayf al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 764/1363 | al-Malik al-Afdal al-‘Abbās b. ‘Alī, Dirghām al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 778/1377 | al-Malik al-Ashraf Ismā‘īl I b. al-‘Abbās |

| ⊘ 803/1400 | al-Malik al-Nāsir Aḥmad b. Ismā‘īl I, Salāh al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 827/1424 | al-Malik al-Manṣūr ‘Abdallāh b. Aḥmad |

| ⊘ 830/1427 | al-Malik al-Ashraf Ismā‘īl II b. ‘Abdallāh |

| ⊘ 831/1428 | al-Malik al-Zāhir Yaḥyā b. Ismail II |

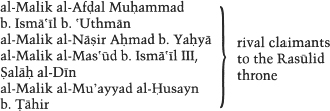

| 842/1439 | al-Malik al-Ashraf Ismail III b. Yaḥyā |

| 845–58/1442–54 | al-Muzaffar Yūsuf II b. ‘Umar |

| 846/1442 |

|

846/1442 |

|

847–58/1443–54 |

|

855–8/1451–4 |

|

858/1454 |

Ṭāhirid capture of Aden |

Obliging historians and genealogists concocted for the Rasūlids a descent from the royal house of the pre-Islamic Ghassānids and, ultimately, from Qahtān, progenitor of the South Arabs. But it is more probable that they came from the Menjik clan of the Oghuz Turks, who had participated in the Turkish invasions of the Middle East under the Saljuqs, and that the original Rasūl had been employed as an envoy [rasūl) by the ‘ Abbāsid caliphs.

A number of amirs from the Rasūlid family accompanied the first Ayyūbids to Yemen (see above, no. 30, 8), and, when the last Ayyūbid, al-Malik al-Kāmil’s son al-Malik al-Mas’ūd Salāh al-Dīn Yūsuf, left Yemen for Syria in 626/1229, he left Nūr al-Dīn ‘Umar al-Rasūlí as his deputy. In the event, no Ayyūbid ever reappeared in Yemen, so the Rasūlids now began to rule independently in Tihāma and the southern highlands, acknowledging the Ayyūbids and the ‘Abbāsid caliphs as their overlords; Ayyūbid traditions remained strong in the new state, seen for example in their royal titulature. Very soon, the strongly Sunni Rasūlids were able to extend their power and to capture Ṣan‘ā‘ from the Zaydī Imāms, holding it for a few decades, and as far eastwards in Hadramawt and Zufār as modern Sālala in the southern part of the sultanate of Oman. The later thirteenth and fourteenth centuries saw the zenith of Rasūlid political power and cultural splendour. The sultans were great builders in such cities as Ta‘ izz and Zabīd, and were munificent patrons of Arabic literature, with not a few of the sultans themselves proficient authors. From Aden, a far-flung trade was conducted to India, South-East Asia, China and East Africa, and an embassy from Yemen to China is recorded, doubtless stimulated by these trade links with the Far East. But after the death of Salāh al-Dīn Aḥmad in 827/1424, the Rasūlid state began to show signs of disintegration, with indiscipline among the Rasūlids’ slave troops, a series of short-reigned rulers and internecine warfare among several pretenders. Thus when the Rasūlid amir of Aden, al-Ḥusayn b. Tahir, surrendered his city to the Tāhirids (see below, no. 50) and Salāh al-Dīn b. Ismā‘īl III left for Mecca, the rule of the family came to an end after more than two centuries.

Lane-Poole, 99–100; Zambaur, 120; Album, 27.

EI2 ‘Rasūlids‘ (G. R. Smith).

G. R. Smith, The Ayyūbids and Early Rasūlids in the Yemen, II, 83–90, with genealogical tables at pp. 83–4.

idem, in W. Daum (ed.), Yemen: 3000 Years of Art and Civilisation in Arabia Felix, 1367, 139, with a list of rulers at p. 139.

858–923/1454–1517

Southern Yemen and Tihāma, with their capitals at al-Miqrāna and Juban

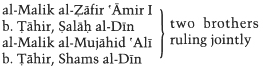

| 858/1454 |

|

| 864/1460 | al-Malik al-Mujāhid ‘Alī b. Tāhir, Shams al-Dīn, as sole ruler |

| ⊘ 883/1478 | al-Malik al-Manṣūr ‘Abd al-Wahhāb b. Dāwūd b. Tāhir, Tāj al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 894–923/1489–1517 | al-Malik al-Zāfir ‘Āmir II b. ‘Abd al-Wahhāb, Salāh al-Dīn |

| 923/1517 | Conquest of the Yemen by the Egyptian Mamlūks |

| (924–45/1518–38 | Persistence of some Tāhirid princes in fortresses of the highlands of Yemen; five of them are mentioned, from Aḥmad b. ‘Āmir II to ⊘ ‘Āmir III b. Dāwūd) |

The Ṭāhirids were a native Yemeni, Sunnī family who rose to prominence in the last days of the Rasūlids (see above, no. 49) and took over the Rasūlid lands in southern Yemen and Tihāma on the demise of that dynasty. Four sultans ruled jointly or succeeded each other, maintaining the administrative traditions of their former patrons. They also inherited the Rasūlids‘ role as great builders: in such towns as Zabīd, the religious centre of Yemeni Sunnism, they erected mosques and madrasas; in Aden, the principal port of Yemen and bastion against the Egyptian Mamlūks and the Portuguese (it was first besieged by Afonso d‘Albuquerque in 919/1513), they built commercial premises and fortifications. In highland Yemen, they extended their power against the Zaydī Imāms and captured Ṣan‘ā‘. But the Egyptian Mamlūks wished to control Yemen as a base for operations in the Indian Ocean against the Portuguese, and after 921/1515 Egyptian attacks began, leading to the Mamlūks ‘occupation of much of Yemen and the end of the Tāhirids. Only a few Tāhirid chiefs seem to have survived in the highland zone until the Ottoman governor Süleymān Pasha executed the last one, ‘Āmir III b. Dāwūd, in 945/1538.

Lane-Poole, 101; Zambaur, 121; Album, 27.

G. R. Smith, in W. Daum (ed.), Yemen: 3000 Years of Art and Civilisation in Arabia Felix, 137–9, with a list of rulers at p. 139.

Venetia A. Porter, The History and Monuments of the Tahirid Dynasty of the Yemen 858923/1454–1517, University of Durham Ph.D. thesis 1992, unpubl., I, with genealogical tables at pp. 295–7.

First to second/seventh to eighth centuries

Oman

Sa‘īd and Sulaymān b. ‘Abbād b. ‘Abd b. al-Julandā, joint rulers, abandoned Oman during the caliphate of ‘Abd al-Malik |

|

| 131–3/748–51 | al-Julandā b. Mas‘ūd b. Ja‘far b. al-Julandā, first Ibādī Imām in Oman |

| ? –177/? –793 | Rashīd b. al-Nazr and Muḥammad b. Zā‘ida, joint rulers on behalf of the ‘Abbāsids |

End of the second century/beginning of the ninth century Decline of Julandi power in Oman |

The Āl al-Julandā were a line of obvious importance in the pre-Islamic and early Islamic history of Oman, but one for which it seems impossible to construct a firm chronology of rule, since they impinged on the Islamic historical sources at only a few key points in their history. The line was of Azdi origin, and must have arrived in Oman as part of the general migrations of the Azd from Hijāz in pre-Islamic times, reaching there at a time when the coastlands at least of Oman were controlled by Sāsānid Persia, After the extension of Arab-Muslim control over eastern Arabia, the Julandā chiefs became representatives of the Medinan government. But Oman‘s role as a refuge area for Khārijls and other dissidents provoked an expedition during al-Hajjāj b. Yūsuf‘s governorship of Iraq and the East which ejected the Julandi brothers Sa‘īd and Sulaymān and forced them to flee to East Africa.

Al-Julandā b. Mas‘ūd was won over by the local Ibāḍī Khārijīs (see on the Ibādiyya, above, no. 9) and became their first Imām in Oman (the beginning of what was to be a tradition of allegiance to Ibāḍī doctrines there which has lasted to this day), but he was killed in 133/751 by a punitive expedition sent by the ‘Abbāsid caliph al-Saffāh (see above, no. 3, 1). Thereafter, the Āl al-Julandā seem to have abandoned leadership of the Ibādiyya, but the joint rulers Rashid and Muḥammad were overthrown in a tribal revolt in 177/793, and Julandi power then declined, after having been influential in Oman for three centuries; only odd members of the family are mentioned in the ninth century.

Zambaur, 125–6.

G. P. Badger, History of the Imâms and Seyyids of ‘Omân, by Salîl Ibn Razîk, from A.D. 661–1856, London 1871.

J. C. Wilkinson, The Julanda of Oman‘, Journal of Oman Studies, 1 (1975), 97–108, with a genealogical table at p. 106.

‘Isam ‘Alī Ahmed al-Rawas, Early Islamic Oman (ca. 622–1280/893), Durham University Ph.D. thesis 1992, unpubl, 166ff.

c. 390–443/c. 1000–40

Coastal Oman

| between 390 and 394/ |

|

| between 1000 and 1004 | al-Ḥusayn b. Mukram, Abū Muḥammad I |

| ⊘ before 415/1024 | ‘Alī b. al-Ḥusayn, Abu ‘1-Qāsim Nāsir al-Dīn, d. 428/1037 |

| ⊘ 428/1037 | Abu ‘l-Jaysh b. ‘Alī, Nāsir al-Dīn, d. soon after becoming governor |

| 431–3/1040–2 | Abū Muḥammad II b. ‘Alī |

| 433/1042 | Assumption of direct rule by the Būyids |

The Mukramids were presumably a local Omani family, who around the beginning of the eleventh century were appointed governors in coastal Oman, with their capital at Ṣuḥār, by the Būyids of Persia (see below, no. 75). The interior of Oman must have been held by the Imāms elected by the Ibādl Khārijī community there. The Mukramid Abū Muḥammad I al-Ḥusayn subsequently served the Būyid Amirs in Fars. The end of this brief line of hereditary governors came after a revolt against his suzerain by Abū Muḥammad II, so that in 433/1042 a Būyid prince was installed as governor in Oman.

S. M. Stern and A. D. H. Bivar, ‘The coinage of Oman under Abū Kālijār the Buwayhid‘, NC, 6th series, 18(1958), 147–56, with a genealogical table of the Mukramids at p. 149.

1034–1156/1625–1743

Oman, with their centre at al-Rustdā

| 1034/1625 | Nāṣir b. Murshid |

| 1059/1649 | Sulṭān lb. Sayf |

| c. 1091–1103/c. 1680–92 | Abu Arab b. Sayf, in Jabrin |

| 1103/1692 | Sayf I b. Sulṭān I, in al-Rustāq |

| 1123/1711 | Sulṭān II b. Sayf I, in al-Hazm |

| 1131/1719 |

|

1134/1722 |

|

| 1137–40/1724–8 | Muḥammad b. Nāṣir al-Ghāfirí, guardian of Sayf II, proclaimed Imām |

| 1151/1738 | Sulṭān b. Murshid, rival Imām |

| 1167/1754 | Succession to power of the Āl Bū Sa‘īd |

The Ya‘rubī chiefs rose to prominence as Imāms of the Ibāḍīs at a time when coastal Oman was threatened by the Portuguese and when interior Oman had been largely taken over by other, non-Ibāḍī Arab groups like the Nabhānīs and immigrants from Bahrayn and Persia. In the two or three decades after Nāṣir b. Murshid‘s accession in 1034/1625, the Ya‘rubīs secured their power against external enemies like the Portuguese and the Persian Ṣafawids. But in the early eighteenth century, the succession of a minor, Sayf II b. Sulṭān II, led to internal disputes between the tribal groups of the Ḥināwīs and the Ghāfirīs, with rival candidates for the Imamate and intervention by the Persians at Muscat (Masqat) and Ṣuḥār. It now fell to the rising power of the Āl Bū Sa‘īdīs to eject the intruders, replace the quarrelling last Ya‘rubids and make firm their own authority in both Oman and the East African coast (see below, nos 54, 65).

Zambaur, 128.

EI1 ‘Ya‘rub‘ (A. Grohmann).

R. D. Bathurst, The Ya‘rubī Dynasty of Oman, Oxford University D.Phil, thesis 1967, unpubl.

J. C. Wilkinson, The Imamite Tradition of Oman, Cambridge 1987, 12–13, with a genealogical table at p. 13.

c. 1167-/c. 1754-

Muscat and then Zanzibar, at present in Oman

| c. 1167/c. 1754 | Aḥmad b. Sa‘īd, elected Imām of the Ibādiyya |

| 1198/1783 | Sa‘īd b. Aḥmad, Imām |

| c. 1200/c. 1786 | Ḥāmid b. Sa‘īd, Sayyid, regent |

| 1206/1792 | Sulṭān b. Aḥmad |

| 1220/1806 | Sālim b. Sulṭān, jointly with Sa‘īd b. Sulṭān until the former‘s death in 1236/1821 |

| 1236/1821 | Sa‘īd b. Sulṭān, sole ruler |

| 1273/1856 | Division of the sultanate on Sa‘īd‘s death |

2. The line of sultans in Oman

| 1273/1856 | Thuwaynī b. Sa‘īd |

| 1282/1866 | Sālim b. Thuwaynī |

| 1285/1868 | ‘Azzānb. Qays |

| 1287/1870 | Turkī b. Sa‘īd |

| ⊘ 1305/1888 | Fayṣal b. Turkī |

| 1331/1913 | Taymūr b. Fayṣal |

| ⊘ 1350/1932 | Sa‘īd b. Taymūr |

| ⊘ 1390- /1970- | Qābūs b. Sa‘īd |

3. The line of sultans in Zanzibar (see below, no. 65)

The Bū Sa‘īdīs succeeded to the heritage of the preceding line of Ya‘rubid Imāms (see above, no. 53) in both Oman and the East African coastlands. Aḥmad b. Sa‘īd began as governor of Ṣuḥār in coastal Oman when the last Ya‘rubids were embroiled in their family quarrels, and soon became de facto ruler of Oman. Hence the Ibāḍī ‘ulamā‘ formally elected him Imām in c. 1167/c. 1754. His son and successor Sa‘īd also had the title of Imām, but thereafter the Bū Sa‘īdī rulers styled themselves Sayyids, while being generally known to the outside world as Sultans.

Muscat, which eventually became the Bū Sa‘īdī capital, had long been a port of international significance and had played an important role in the struggles of the Portuguese and then the Dutch for the commercial control of the Persian Gulf. Sulṭān b. Aḥmad pursued an expansionist policy there as far as Bahrayn island and as far as Bandar ‘Abbās, Kishm and Hurmuz along the southern coasts of Fars. However, the Sayyids‘ position was menaced in the early nineteenth century by the aggressive Wahhābīs of Najd. They countered this by an alliance with Britain, which was concerned that Muscat, lying as it did near the route to India, should remain in friendly hands. In 1212/1798, the first treaty with the East India Company was made; later, in the nineteenth century, Britain used her influence at Muscat to control and then end the slave trade in the Gulf.

The Ya‘rubid possessions on the East African coast had been largely lost in the wars with Persia of the late eighteenth century, with virtually only Zanzibar, Pemba and Kilwa remaining to the Bū Sa‘īdīs. But Sa‘īd b. Sulṭān during his long reign extended his suzerainty over all the Arab and Swahili colonies from Mogadishu in the north to Cape Delgado in the south, effectively ruling in Zanzibar from 1242/1827 onwards. After his death in 1273/1856, the Bū Sa‘īdī dominions were divided into two separate sultanates, with Thuwaynī ruling over Oman from Muscat and his brother Mājid ruling over Zanzibar and the East African coastland respectively; for this last branch of the family, see below, no. 65.

Oman itself was then racked by family discord, and in the early twentieth century the rigorist Ibāḍī ‘ulama? of the interior dissociated themselves from what they regarded as the corrupt rule of the Bū Sa‘īdīs in the coastal regions. They restored the Imāmate in 1331/1913 and erupted into rebellion against the Sultan and what they regarded as his British protectors. But confined as it was to the interior, and with a totally backward-looking aspect which contrasted with the adaptability to new conditions of the Su‘ūdīs and their Wahhābī followers, the Imāmate represented a last stand of tribal elements. The armed insurrection of the 1950s, in which the Imām Ghālib b. ‘Alī had Su‘ūdī and Egyptian backing, was largely extinguished by the end of the decade; and the deposition of the reactionary and parsimonious Sa‘īd b. Taymūr by his son Qābūs in 1390/1970 at last opened up Oman to the world around it and, eventually, led to a reconciliation of elements within the country.

Zambaur, 129 and Table M.

EI2‘ Bū Sa‘īd (C. F. Beckingham), with a genealogical table which corrects Zambaur’s list in several places; ‘Maskat’ (J. C. Wilkinson).

J. C. Wilkinson, The Imāmate Tradition of Oman, with a genealogical table at p. 14.

1148-/1735-

Originally in south-eastern Najd; in the twentieth century kings of Hijāz and Najd and then of Su‘ūdī (Saudi) Arabia

| 1148/1735 | Muḥammad b. Su‘ūd b. Muḥammad, amir of Dir‘iyya |

|

| 1179/1765 | ‘Abd al-‘Azīz I b. Muḥammad |

|

| 1218/1803 | Su‘ūd I b. ‘Abd al-‘Azīz |

|

| 1229/1814 | ‘Abdallāh Ib. Su‘ūd I, k. 1234/1819 |

|

| 1233–8/1818–22 | First Turco-Egyptian occupation |

|

| 1237/1822 | Turkī b. ‘Abdallāh b. Muḥammad |

|

| 1249/1834 | Mushārī b. ‘Abd al-Rahmān |

|

| 1249/1834 | Fayṣal I b. Turkī, first reign |

|

| 1254–9/1838–43 | Second Turco-Egyptian occupation |

|

| 1254/1838 | Khālid b. Su‘ūd I |

|

1257/1841 |

|

|

| 1259/1843 | Fayṣal I, second reign |

|

| 1282/1865 | ‘Abdallāh III b. Fayṣal I, first reign |

|

| 1288/1871 | Su‘ūd II b. Fayṣal I |

|

| 1291/1874 |

|

|

| (? 1288/1871) | ‘Abdallāh III b. Fayṣal I, second reign |

|

| 1305/1887 | Muḥammad b. Su‘ūd II |

|

| 1305/1887 | Conquest of Riyāḍ by Muḥammad b. ‘Abdallāh Ibn Rashīd of Hā‘il, with ‘Abdallāh III as governor of Riyāḍ until 1307/1889 |

|

| 1307/1889 | ‘Abd al-Raḥmān b. Fayṣal I as governor in Riyāḍ under the Ā1 Rashīd |

|

| 1309/1891 | Muḥammad b. Fayṣal I, al-Mutawwi‘, as vassal governor under the Ā1 Rashīd |

|

| 1309/1891 | Direct rule in Riyāḍ of Muḥammad Ibn Rashīd |

|

| ⊘ 1319/1902 | ‘Abd al-‘Azīz II b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān, amīr in Riyāḍ, King of Hijāz and Najd 1344/1926 and King of Su‘ūdī Arabia in 1350 or 1351/1932 |

|

| ⊘ 1373/1952 | Su‘ūd III b. ‘Abd al-‘Azīz |

|

| ⊘ 1384/1964 | Fayṣal II b. ‘Abd al-‘Azīz |

|

| ⊘ 1395/1975 | Khālid b. ‘Abd al-‘Azīz |

|

| ⊘ 1401– /1982– | Fahd b. ‘Abd al-‘Azīz |

|

Su‘ūd b. Muḥammad b. Muqrin (d. 1148/1735), from the ‘Anaza tribe, was amīr of Dir‘iyya in the Wādī Hanīfa district of Najd, and Dir‘iyya remained the seat of the Su‘ūd family until its destruction by Ibrāhīm Pasha in the early nineteenth century and the end of the first Su‘ūdī state. The rise of the family was connected with the movement of Muḥammad b. ‘Abd al-Wahhāb, a puritanical reformer in the conservative legal tradition of Ḥanbalism and the thirteenth-fourteenth-century religious leader in Damascus, Ibn Taymiyya. He stressed the unity and transcendence of God and the duty of avoiding all forms of shirk, associating other persons or things with God, one practical effect of this being hostility to such aspects of popular religion in Arabia as the cult of saints and their shrines; when the Su‘ūdī-led Wahhābīs extended their power through much of the peninsula, they systematically destroyed such manifestations of (to them) bid‘a, heretical innovation. It seems that the Su‘ūdī amīrs saw the material advantages of harnessing Wahhābī enthusiasm for their plans of political expansion in Najd. By the end of the eighteenth century, all Najd was controlled by them, and raids were made against Ottoman Syria and Iraq, culminating in the sack of the Shī‘ī holy city of Karbalā‘ in 1218/1803, regarded as an object of superstitious veneration; and the Holy Cities of Mecca and Medina were seized and purged of idolatrous features.

The collapse of this power and of the first Su‘ūdī state came as a result of these Su‘ūdī provocations of the Ottomans. The sultan deputed the governor of Egypt, Muḥammad ‘Alī Pasha (see above, no. 34), to deal with the Arabian situation. Hence in 1233/1818 the latter‘s son Ibrāhīm took Dir‘iyya and destroyed it utterly, carrying off the Su‘ūdī amīr for execution in Istanbul. The second Su‘ūdī amirate revived cautiously in eastern Arabia during the middle years of the century. From his capital Riyāḍ, Fayṣal I extended his power over al-Ahsā in the eastern Arabian coastland, but a second Turco-Egyptian occupation took place in 1254–9/1838–43, with Fayṣal carried off to Egypt and Su‘ūdī vassals of the Ottomans placed on the throne. Fayṣal escaped from captivity, and in 1259/1843 successfully regained power in his homeland, with this second reign marking a high point in Su‘ūdī fortunes. But after his death, the family was rent by internal disputes; al-Ahsā was occupied by the Ottoman governor of Iraq, Midḥat Pasha; and the second Su‘ūdī state came to an end in 1305/1887 when the Su‘ūdīs‘ rival Muḥammad Ibn Rashīd of Hā‘il (see below, no. 57) occupied Riyāḍ, so that the Su‘ūdis had to take refuge in Kuwait.

The establishment of the third, and present, Su‘ūdī state in the twentieth century is connected with the long-lived and remarkable figure of ‘Abd al-‘Azīz Ibn Su‘ūd, who, with tacit British support, eventually subdued the pro-Ottoman Ā1 Rashīd, annexed ‘Asīr, prevented the Sharif Ḥusayn from setting himself up as caliph in 1924 (see below, no. 56), took over Hijāz shortly afterwards, and became King of Hijāz and Najd and then of Su‘ūdī Arabia, controlling by then nearly three-quarters of the peninsula. The large-scale exploitation of oil in eastern Arabia, begun in Ibn Su‘ūd‘s time, has transformed what was originally a desert state into a power of international economic significance, especially after the 1970s’ oil-price boom, but has also brought to the country internal religious and social tensions.

Zambaur, 124 and Table L.

EI1 ‘Ibn Sa‘ud‘ (J. H. Mordtmann); EI2 ‘Su‘ūd, Āl‘ (Elizabeth M. Sirriyyeh).

Naval Intelligence Division, Geographical Handbook series, Western Arabia and the Red Sea, London 1946, 265–70, 283–6, with a genealogical table at p. 286.

H. St J. Philby, Arabian Jubilee, London 1952, with detailed genealogical tables at pp. 250–71.

idem, Saudi Arabia, London 1955.

R. Bayley Winder, Saudi Arabia in the Nineteenth Century, London 1965.

56

THE HĀSHIMITE SHARĪFS OF MECCA FROM THE ‘AWN FAMILY

1243–1344/1827–1925

Mecca and Hijāz latterly, with branches in the Fertile Crescent countries

1. The original line in Western Arabia

| 1243/1827 | ‘Abd al-Muṭṭalib b. Ghālib, of the Zayd branch of Sharīfs, first reign) |

| 1243/1827 | Muḥammad b. ‘Abd al-Mu‘īn b. ‘Awn, first Sharīfian amīr in Mecca of the ‘Abādila branch of the ‘Awn family, first reign |

| (1267/1851 | ‘Abd al-Muṭṭalib b. Ghālib, second reign) |

| 1272/1856 | Muḥammad b. ‘Abd al-Mu‘in, second reign |

| 1274/1858 | ‘Abdallāh b. Muḥammad |

| 1294/1877 | al-Ḥusayn b. Muḥammad |

| (1297/1880 | ‘Abd al-Muṭṭalib b. Ghālib, third reign) |

| 1299/1882 | ‘Awn al-Rafiq b. Muḥammad |

| 1323/1905 | ‘Ali b. ‘Abdallāh |

| ⊘ 1326/1908 | Ḥusayn b. ‘Alī, until 1335/1916 Sharīf of Mecca and Hijāz, thereafter King of Hijāz, assumed the title of caliph in 1343/1924, d. 1350/1931 |

| 1343/1925 | ‘Alī b. Ḥusayn, d. 1353/1934 |

| 1344/1925 | Conquest of Hijāz by ‘Abd al-‘Azīz Ibn Su‘ūd |

2. The post-First World War branches of the Ḥashimite family

in the Fertile Crescent countries

| ⊘ 1338/1920 | Fayṣal b. Ḥusayn b. ‘ Alī, elected King of Greater Syria, subsequently King of Iraq |

| 1338/1920 | French Mandate imposed on Syria |

| ⊘ 1340/1921 | Fayṣal I b. Ḥusayn, appointed King of Iraq |

| ⊘ 1352/1933 | Ghāzī b. Fayṣal |

| ⊘ 1358–77/1939–58 | Fayṣal lib. Ghāzī |

| 1377/1958 | Overthrow of the monarchy and its replacement by a republican régime |

(c) The line in Transjordan and then Jordan

| ⊘ 1339/1921 | ‘Abdallāh b. Ḥusayn, declared Amīr of Transjordan, and in 1365/1946 King of Transjordan, later Jordan |

| 1370/1951 | Ṭalāl b. ‘Abdallāh, d. 1392/1972 |

| ⊘ 1371– /1952– | Ḥusayn b. Talāl |

The Hāshimite Sharīfs (‘noble ones’) of Mecca traced their descent directly back to the Prophet Muḥammad and his clan in Mecca of Hāshim. The Sharīfs held power in the Holy City from the tenth century onwards, in later times under Mamlūk and then Ottoman protection. In the early nineteenth century they were subjected to attacks by the Wahhābls of Najd under the amīr Su‘ūd b. ‘Abd al-‘Azīz, who captured Mecca in 1218/1803 (see above, no. 55). Liberated in 1228/1813 by Ibrāhīm b. Muḥammad ‘Alī of Egypt‘s army, the Sharīfate alternated during the nineteenth century between the Zayd and ‘Awn branches, not finally settled in favour of the ‘Abādila of the ‘Awn until 1299/1882, by which time the Ottomans had for some four decades been controlling Ḥijāz as a province of their empire.

With Turkey‘s involvement in the First World War on the side of the Central Powers, the Sharīf Ḥusayn became caught up in the Arab Revolt of 1916 which cleared all Ḥijāz except Medina of Ottoman troops and which, in concert with the British army advance from Egypt, eventually freed Greater Syria from Turkish control. Early in the Revolt, Ḥusayn proclaimed himself ‘King of the Arab lands‘, but the Allies would only recognise him as King of Ḥijāz. After 1918 his authority was confined to Ḥijāz, where he came to arouse much Arab hostility by an ill-judged attempt in 1924 to assume the caliphate personally after Muṣṭafa Kemāl‘s abolition of that institution in Turkey. His eldest son and successor ‘Alī had to abandon Ḥijāz to the Su‘ūdī invader ‘Abd al-‘Azīz b Su‘ūd, who soon afterwards formed his united kingdom of Ḥijāz and Najd (see above, no. 55).

In the post-First World War arrangements for the Arab lands of the former Ottoman empire, other sons of Ḥusayn were, however, to play a prominent role. The third son Fayṣal from 1918 onwards endeavoured to assume power in the Greater Syria region, and in 1920 was elected King of a united Syria by the Second Syrian General Arab Congress, but had to leave there shortly afterwards when Syria passed under French Mandatary tutelage. Instead, in 1921 and with British support, he became King of Iraq, under a British Mandate; the Hāshimites had no particular connection with Iraq, but no more suitable candidate presented himself. The Ḥashimite monarchy in Iraq, although ruling the first Arab country to free itself from Mandatary control, never put down deep roots, and in 1958 was overthrown by a bloody army coup led by ‘Abd al-Karlm al-Qāsim in which Fayṣal II was killed. More successful and enduring was the establishment of Ḥusayn‘s second son ‘Abdallāh as amīr of the Trans Jordanian lands separate from Mandatary Palestine, which after the Second World War became the independent Hāshimite Kingdom of Jordan, still ruled until today by one of the great survivors of Middle Eastern politics, ‘Abdallāh’s grandson King Ḥusayn.

Zambaur, 23.

EI2 ‘Hāshimids’ (C. E. Dawn); ‘Ḥusayn b. Alī‘ (S. H. Longrigg); ‘Makka. 2. From the Abbāsid to the modern period’ (A. J. Wensinck and C. E. Bosworth).

C. Snouck Hurgronje, Mecca in the Later Part of the Nineteenth Century, Leiden 1931.

Naval Intelligence Division, Geographical Handbook series, Western Arabia and the Red Sea, 268ff., with a genealogical table at p. 282.

Gerald de Gaury, Rulers of Mecca, London 1951, with a list of rulers of Mecca at pp. 288–93.

1252–1340/1836–1921

Northern Najd

| (c. 1248/c. 1832 | ‘Abdallāh b. ‘Alī b. Rashīd, as governor for the Wahhābīs) |

| 1252/1836 | ‘Abdallāh b. ‘Alī, as independent ruler |

| 1264/1848 | Ṭalāl b. ‘Abdallāh |

| 1285/1868 | Mut‘ab (colloquially, Mit‘ab) I b. ‘Abdallāh |

| 1286/1869 | Bandar b. Ṭalāl |

| 1286/1869 | Muḥammad b. ‘Abdallāh |

| 1315/1897 | ‘Abd al-‘Azīz b. Mut‘ab |

| 1324/1906 | Mut‘ab (Mit‘ab) II b. ‘Abd al-‘Azīz, k. 1324/1906 |

| 1325/1907 | Sulṭān b. Ḥammūd |

| 1325/1908 | Su‘ūd I b. Ḥammūd |

| 1328/1910 | Su‘ūd II b. ‘Abd al-‘Azīz, k. 1338/1920 |

| 1339/1920 | ‘Abdallāh b. Mut‘ab II, d. |

| 1339/1921 | Muḥammad b. Ṭalāl, d. |

| 1340/1921 | Su‘ūdī conquest |

The Rashīd family were chiefs of the ‘Abda clan of the Shammar tribal confederation in the Jabal Shammar region of northern Arabia, with their centre at Ḥā‘il. ‘Abdallāh b. ‘Alī achieved power in Ḥā‘il with the support of Fayṣal b. Turkī of the Su‘ūdi rulers of Riyāḍ (see above, no. 55), displacing his kinsmen of the Ā1 Ibn ‘Alī, and he was, like the Su‘ūdīs, an adherent of Wahhābism, but in its religious rather than political aspect. The Rashīdī shaykhdom reached a peak of prosperity in the mid-nineteenth century, with a prosperous caravan trade based on Ḥā‘il, and Muḥammad b. ‘Abdallāh extended his authority northwestwards through the Wādī Sirḥān and as far as Palmyra in Syria, and south-eastwards to Qaṣim in the heart of Najd. He temporarily captured Riyāḍ from the Su‘ūdīs and expelled them altogether from Najd to Kuwait in 1309/1891; the port of Kuwait was itself coveted by the Rashīdīs for the import of arms into their landlocked principality.

The whole history of the Ā1 Rashīd was marked by violence and fratricidal strife (the great majority of the amīrs died either by assassination or in battle), and after Muḥammad‘s death their power declined because of savage internal quarrels plus pressure from the renascent power of the Su‘ūdīs under ‘Abd al-‘Azīz b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān Ibn Su‘ūd. The general backing of the Ottomans, including the despatch of regular Turkish troops to support them in Najd, did not save them, and Ibn Su‘ūd was finally able to capture Ḥā‘il in 1340/1921. The Rashīdī territories were incorporated into what now became the united principality of Najd and, soon afterwards, the Su‘ūdī kingdom of Ḥijāz and Najd (see above, no. 55), and the members of the Ā1 Rashīd were exiled to Riyāḍ.

None of the amīrs of the Ā1 Rashīd issued coins.

Zambaur, 125–6.

EI2 ‘Ḥāyū‘ (J. Mandaville); ‘Rashīd, ĀF (Elizabeth M. Sirriyyeh).

Naval Intelligence Division, Geographical Handbooks Series, Western Arabia and the Red Sea, 269ff., with a genealogical table at p. 286.

H. St J. Philby, Saudi Arabia, London 1955.

Madawi Al-Rasheed, Politics in an Arabian Oasis: The Rashidi Tribal Dynasty, London 1991, with a genealogical table and list of the amīrs at pp. 55–6.