FOURTEEN

Persia after the Mongols

643–791/1245–1389

Eastern Khurasan and northern Afghanistan

| 643/1245 | Muḥammad b. Abī Bakr Rukn al-Dīn b. ‘Uthmān Marghānī, Shams al-Dīn I, k. 676/1278 |

| 676/1277 | Rukn al-Dīn or Shams al-Dīn II b. Muḥammad Shams al-Dīn I, d. 705/1305 |

| 694/1295 | Fakhr al-Dīn b. Rukn al-Dīn or Shams al-Dīn II |

| 707/1308 | Ghiyāth al-Dīn I b. Rukn al-Dīn or Shams al-Dīn II |

| 729/1329 | Shams al-Dīn III b. Ghiyāth al-Dīn I |

| 730/1330 | Ḥāfiẓ b. Ghiyāth al-Dīn I |

| ⊘ 732/1332 | Pīr Ḥusayn Muḥammad b. Ghiyāth al-Dīn I, Mu‘izz al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 772–91/1370–89 | Pīr ‘Alī b. Pīr Ḥusayn Muḥammad Mu‘izz al-Dīn, Ghiyāth al-Dīn II |

| 791/1389 | Annexation by Tīmūr |

The Karts (a presumably Iranian name of unknown significance) were an indigenous line of Maliks of Afghan stock, from the clan or family of the Shansabānīs of Ghūr (see below, no. 159); the founder, Shams al-Dīn Muḥammad I, had married a Ghūrid princess, so that the Karts could claim to be, in some measure, heirs of the Ghūrids, ruling also as they did from the former centres of the Ghūrids, Herat and fortresses within Ghūr.

The incoming Mongols allowed Shams al-Dīn I Muḥammad to retain his lands as a vassal prince, and, ensconced in their nucleus of territories in Herat and the inaccesible mountains of Ghūr, the Karts generally remained loyal allies of the II Khāns. The decay of II Khānid power in Khurasan after Abū Sa‘īd’s death enabled Mu‘izz al-Dīn Pīr Ḥusayn Muḥammad to raise his principality, which now reached to western Khurasan and the Sarbadārid territories (see below, no. 143), to new heights of power and splendour. But the rise of Tīmūr cut short Kart power, and, on the death of his tributary Ghiyāth al-Dīn II Pīr ‘Alī, Tīmūr annexed the Kart territories to his empire.

Lane-Poole, 252; Zambaur, 256–7; Album, 50.

EI2 ‘Kart’ (T. W. Haig and B. Spuler); EIr Āl-e Kart’ (B. Spuler).

B. Spuler, Die Mongolen in Iran. Politik, Verwaltung und Kultur der Ilchanzeit 12201350, 4th edn, 129–33.

L. G. Potter, The Kart Dynasty of Herat. Religion and Politics in medieval Iran, Ph.D diss., Columbia University, New York 1992, unpubl. (UMI Dissertation Services, Ann Arbour).

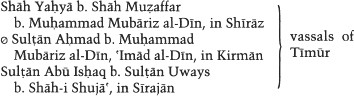

713–95/1314–93

Southern and western Persia

| ⊘ 713/1314 | Muḥammad b. Muẓaffar Sharaf al-Dīn, Mubāriz al-Dīn, d. 765/1363 |

| ⊘ 759/1358 | Shāh-i Shujā‘ b. Muḥammad Mubāriz al-Dīn, Abu ’l-Fawāris Jamāl al-Dīn, first reign |

| ⊘ 765/1364 | Shāh Maḥmūd b. Muḥammad Mubāriz al-Dīn, Quṭb al-Dīn, d. 776/1375 |

| 767/1366 | Shāh-i Shujā‘, second reign |

| ⊘ 786/1384 | Zayn al-‘Ābidīn ‘Alī b. Shāh-i Shujā‘, Mujāhid al-Dīn |

| 789/1387 |

|

| ⊘ 793–5/1391–3 | Shāh Manṣūr b. Shāh Muẓaffar |

| 795/1393 | Tīmūrid conquest |

| before 810/1407 |

|

| or 812/1409 | Sulṭān Mu‘taṣim b. Zayn al-‘Abidīn, attempted to seize Iṣfahān |

The Muẓaffarids, distantly of Khurasanian Arab origin, rose to power in Kirman, Fars and ‘Irāq-i ‘Ajam or Jibāl as the Il Khānid empire declined. Sharaf al-Dīn Muẓaffar was in the service of the Mongols, and was appointed by the Il Khān Ghazan to be commander of 1,000, with military and police duties in southern Persia. His son Mubāriz al-Dīn Muḥammad was the second founder of the dynasty. From a base at Yazd, during the chaos attendant on Abū Sa‘d’s death he expanded his possessions into Fars after protracted strugles with the Inju‘id Abū Isḥāq (see below, no. 141). A marriage to the daughter of the last Qutlugh Khānid ruler of Kirman (see above, no. 105) brought that province to him. By 758/1356 he was undisputed master of Fars and Iraq, and was tempted into invading Azerbaijan, where he captured Tabriz (Tabrīz) but was unable to hold on to it. Muḥammad was deposed by his own son Shāh-i Shujā‘, but Shāh Shuja‘ was involved in disputes with his brother Shāh Maḥmūd, governor in Iṣfahān, until the latter’s death. Shāh Maḥmūd had sought the help of the Muẓaffarids’ old enemies, the Jalāyirids (see below, no. 142), and, when he had at last secured Iṣfahān, Shāh-i Shujā‘ led an expedition into Azerbaijan against the Jalāyirid Ḥusayn b. Uways. But the shadow of Tīmūr was now falling across Persia. Shāh-i Shujā‘ hastened to submit to the great conqueror. His successors, however, were less circumspect. Before his death in 786/1384 Shāh-i Shujā‘ had divided his Kirman and Fars dominions among his relatives, and dynastic disputes were now fatally to weaken the dynasty. In Fars, Zayn al-‘Ābidīn ‘Alī submitted at first to Tīmūr, but Tīmūr later sacked Iṣfahān after his tax-collectors there had been killed in a popular uprising. The last Muẓaffarid, Shāh Manṣūr, was ruler over all Fars and Iraq when Timūr in 795/1393 resolved to extinguish the independent powers of western Persia; Shāh Manṣūr was killed in battle and most of the surviving Muẓaffarids massacred.

Although much of the Muẓaffarid period was racked by family strife, they were nevertheless patrons of such great figures as the poet Ḥāfiẓ and the theologian ‘ Aḍud al-Dīn Ījī, so that their cultural significance well outweighs their mediocre political aptitudes.

Justi, 460; Lane-Poole, 249–50; Zambaur, 254; Album, 48–9.

EI2 ‘Muẓaffarids’, ‘Shāh-i Shudiā’ (P. Jackson).

H. R. Roemer, ‘The Jalayirids, Muẓaffarids and Sarbadārs’, in The Cambridge History of Iran. VI. The Timurid and Safavid Periods, Cambridge 1986, 11–16, 59–64.

c. 725–54/c. 1325–53

Fars

| c. 725/c. 1325 | Maḥmūd Shāh Inju, Sharaf al-Dīn |

| 736/1336 | Mas‘ūd Shāh b. Maḥmūd Shāh, Jalāl al-Dīn, with his power contested until 739/1338 by Ghiyāth al-Dīn Kay Khusraw b. Maḥmūd Shāh |

| 739/1339 | Muḥammad b. Maḥmūd Shāh, Shams al-Dīn, k. 740/1340 |

| ⊘ 743–54/1343–53 | Abū Ishāq b. Maḥmūd Shāh, Jamāl al-Dīn, k. 758/1357 |

| 754/1353 | Occupation of Shiraz (Shīrāz) by the Muẓaffarids |

The Inju’ids derived their name from the fact that the founder of this short line, Sharaf al-Dīn Maḥmūd, was sent to Fars by the Il Khan Öljeytü to administer the royal states there (called in Turkish, and thence in Mongolian, injü). During Abū Sa‘īd’s reign, he consolidated his power at Shiraz and made himself virtually the independent ruler of Fars before being executed by the new Il Khān, Arpa Ke’ün (see above, no. 133). His sons squabbled over possession of Fārs, and when the last one, Jamāl al-Dīn Abū Isḥāq, tried to extend his power to Yazd and Kirman, he came up against the Muẓaffarids (see above, no. 140), who captured Shiraz in 754/1353, the fugitive Abū Isḥāq being killed shortly afterwards.

Sachau, 28 no. 73; Zambaur, 255; Album, 48.

EI2 ‘Indjū’ (J. A. Boyle).

B. Spuler, Die Mongolen in Iran, 4th edn, 122.

740–835/1340–1432

Iraq, Kurdistan and Azerbaijan

| ⊘ 740/1340 | Shaykh Ḥasan-i Buzurg b. Ḥusayn, Tāj al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 757/1356 | Shaykh Uways I b. Ḥasan-i Buzurg |

| ⊘ 776/1374 | Ḥusayn I b. Shaykh Uways I, Jalāl al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 784/1382 | Sulṭān Aḥmad b. Shaykh Uways I, Ghiyāth al-Dīn, k. 813/1410 |

| (784–5/1382–3 | Bāyazīd b. Shaykh Uways I, in Kurdistan) |

| 813/1410 | Shāh Walad b. ‘Alī b. Shaykh Uways I |

| 814/1411 | Maḥmūd b. Shāh Walad, first reign, under the tutelage of Tandu Khātūn |

| ⊘ 814/1411 | Uways II b. Shāh Walad |

| ⊘ 824/1421 | Muḥammad b. Shāh Walad |

| 824/1421 | Maḥmūd b. Shāh Walad, second reign |

| ⊘ 828–35/1425–32 | Ḥusayn II b. ‘Alā’ al-Dawla b. Sulṭān Aḥmad |

| 835/1432 | Qara Qoyunlu conquest of southern Iraq |

The Jalāyirids were one of the successor-states to the II Khānids, succeeding to their territories in Iraq and Azerbaijan. The Jalāyir were, it seems, originally a Mongol tribe in Hülegü‘s following. The founder of the dynasty‘s fortunes was Ḥasan-i Buzurg (called ‘Great’ to distinguish him from his enemy and rival from the Chopanid family of Amīrs, Ḥasan-i Kūchik ‘the Small’), who had been governor of Anatolia under the Il Khān Abū Sa‘īd. He eventually prevailed over the Chopanids and made Baghdad the centre of his power; nevertheless, he continued to recognise various Il Khānid fainéants up to 747/1346, and it was left to his son Shaykh Uways to assume full personal sovereignty.

Shaykh Uways at first recognised the dominion of the Golden Horde (see above, no. 134) over Azerbaijan, but then in 761/1360 conquered it for himself. He also imposed his overlordship in Fars on the disputing Muẓaffarids (see above, no. 140), but his successors had to cope with the rising power of the Qara Qoyunlu Türkmens in Diyār Bakr (see below, no. 145) and an invasion through the Caucasus into Azerbaijan of the Golden Horde Khāns. Shaykh Uways’s son Sulṭān Aḥmad opposed Tīmūr when the latter appeared in northern Persia and Iraq, and had to flee into exile with the Mamlūks in Syria, and he only returned permanently to his capital Baghdad after Tīmūr’s death in 807/1405. However, the shock of the Tīmūrid invasions had much weakened the Jalāyirids‘ position. Azerbaijan quickly fell to the Qara Qoyunlu, and Baghdad itself was captured by them in 814/1411. Only in Lower Iraq, at Wāsit, Basra and Shushtar, did minor Jalāyirid princes survive as vassals of the Tīmūrid Shāh Rukh, until Ḥusayn II was killed at Ḥilla in 835/1432.

The Jalāyirids, on the evidence of their preferences for personal names, may have had some Shī‘ī sympathies, although this evidence is not in general strong. Their rule and patronage in Baghdad and Tabriz was of considerable cultural sigificance, especially in such spheres as architecture and miniature painting, traditions which were regrettably uprooted by the devastations and deportations of Tīmūr.

Lane-Poole, 246–8; Zambaur, 253; Album, 49.

EI2 ‘Djalāyir, Djalāyirid’ (J. M. Smith Jr).

H. R. Roemer, in The Cambridge History of Iran, VI, 5–10, 64–7.

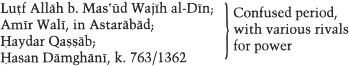

737–88/1337–86

Western Khurasan

| 737/1332 | ‘Abd al-Razzāq b. Faḍl Allāh |

| 738/1338 | Mas‘ūd b. Faḍl Allāh, Wajīh al-Dīn |

| 743/1343 | Muḥammad Ay Temür, k. 747/1346 |

| ⊘ 748/1347 | ‘Alī b. Shams al-Dīn Chishumī, Khwāja Tāj al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 752/1351 | Yaḥyā Karāwī, k. 759/1357 |

|

|

| ⊘ 763/1362 | Khwāja ‘Alī b. Mu’ayyad, first reign |

| 778/1376 | Rukn al-Dīn |

| 781–8/1379–86 | Khwāja ‘Alī, second reign |

| 788/1386 | Division of territories among several commanders of the Tīmūrids |

The Sarbadārids (roughly interpretable as ‘reckless ones’) ruled in the Bayhaq or Sabzawār district of Khurasan during the period between the death of the Il Khānid Abū Sa‘īd and the steep decline of his dynasty’s power (see above, no. 133) and the rise of Tīmūr. Rather than being a ‘bandit state’ or a millenarian Shī‘ī movement, the Sarbadārids represented an attempt by the local populations of western Khurasan to preserve some order and security there in the aftermath of Mongol rule over Persia; thus in some ways they form a later, and shorter-lived, counterpart to the earlier constituting of the Kart Maliks’ principality in eastern Khurasan (see above, no. 139).

The Sarbadārids movement began as a rising in 737/1332 against fiscal oppression under the Chingizid Toqay Temür. The rebels soon afterwards made an uneasy alliance with local Shī‘ī shaykhs. In 754/1353 they succeeded in overthrowing and killing Toqay Temür, the last of his line. Leadership within the Sarbadār movement was unstable and often contested. Under the last leader, Khwāja ‘Alī, Shī‘ism was explicitly adopted, but Khwāja ‘Alī also submitted to Tīmūr. When the former died in 788/1386, the Sarbadārids lands were divided among several commanders who also served Tīmūr.

Lane-Poole, 251; Zambaur, 258; Album, 50.

EI2 ‘Sarbadārids’ (C. P. Melville).

J. Masson Smith Jr, The History of the Sarbadār Dynasty 1336–1381 A.D. and its Sources, The Hague 1970, with a list and discussion of the confused chronology of the Sarbadārids commanders, and the contradictory information of the sources, at pp. 52–4.

A. H. Morton, ‘The history of the Sarbadārs in the light of new numismatic evidence’, NC, 7th series, 16 (1976), 255–8.

H. R. Roemer, in The Cambridge History of Iran, VI, 16–39.

771–913/1370–1507

Transoxania and Persia

| ⊘ 771/1370 | Tīmūr-i Lang (Tamerlane) b. Taraghay Barlas, Küreken |

| ⊘ 807–9/1405–7 | Pīr Muḥammad b. Jahāngirb. Tīmūr, in Kandahar (Qandahār) |

| ⊘ 807–11/1405–9 | Khalīl Sulṭān b. Mīrān Shāhb. Tīmūr, in Samarkand, d. 814/1411 |

| ⊘ 807–11/1405–9 | Shāh Rukh b. Tīmūr, in Khurasan only |

| ⊘ 811/1409 | Shāh Rukh, in Transoxania, eastern and central Persia and then western Persia |

| ⊘ 850/1447 | Ulugh Beg b. Shāh Rukh, in Transoxania and Khurasan |

| ⊘ 853/1449 | ‘Abd al-Laṭīf b. Ulugh Beg, in Transoxania |

| ⊘ 854/1450 | ‘Abdallāh b. Ibrāhīm b. Shāh Rukh, in Transoxania |

| ⊘ 855/1451 | Abū Sa‘īd b. Muḥammad b. Mīrān Shāh, in Transoxania, eastern, central and western Persia as far as ‘Irāq-i ‘Ajam |

| ⊘ 873/1469 | Sulṭān Aḥmad b. Abī Sa‘īd, in Transoxania |

| ⊘ 899/1494 | Maḥmūd b. Abī Sa‘īd, in Transoxania |

|

|

| 906/1500 | Özbeg conquest of Transoxania and Farghāna |

2. The rulers in Khurasan after Ulugh Beg’s death

| ⊘ 851/1447 | Bābur b. Baysonqur, Abu ’l-Qāsim |

| ⊘ 861/1457 | Shāh Maḥmūd b. Bābur |

| ⊘ 861/1457 | Ibrāhīm b. ‘Alā’ al-Dawla b. Baysonqur |

| ⊘ 863/1459 | Abū Sa‘īd b. Muḥammad b. Mīrān Shāh |

| ⊘ 873/1469 | Ḥusayn b. Manṣūr b. Bayqara b. ‘Urnar Shaykh b. Tīmūr, first reign |

| ⊘ 875/1470 | Yādgār Muḥammad b. Sulṭān Muḥammad b. Baysonqur, protégé of the Aq Qoyunlu Uzun Ḥasan in Herat, k. 875/1470 |

| ⊘ 875/1470 | Ḥusayn b. Manṣūr b. Bayqara, second reign |

| 911/1506 |

|

| 913/1507 | Özbeg conquest of Herat |

3. The rulers in western Persia and Iraq after Tīmūr

Tīmūr arose from the Barlas clan of Turkicised Mongols which had nomadised within the Chaghatayid ulus (see above, no. 132). Although his family may subsequently have claimed Chingizid descent, Tīmūr personally never did, and always contented himself with the Arab-Islamic title of Amīr, and not the Turkish one of Khān. He did, however, acquire the title güregen/küreken, in Mongolian ‘royal son-in-law’, by virtue of his marriage to a Chingizid princess. He put together a vast military empire in central, western and southern Asia. But Tīmūr’s interests were in the settled lands of ancient Islamic or Indian culture rather than in the steppes and mountains of Inner Asia, thus marking him off from the earlier Mongol steppe conquerors. He eventually built himself a permanent capital, Samarkand; and though clearly not a religious man, he found the religious ideology of Islam a useful aid in his campaigns into such regions as the Caucasus and India.

Tīmūr’s rise to power took place in a fragmented Transoxania, weakened by the decay of the Chaghatayids of the west, during which various attempts from Mogholistan to re-establish the ulus failed. There was still a certain feeling, however, for the legitimacy of Mongol rule, and when Tīmūr first came to power he installed puppet Chingizid khāns in Transoxania, including a descendant of the Great Khan Ögedey, Soyurghatmïsh, and his son.

His first campaigns were in Khwārazm and Khurasan, after which he began the conquest of Persia in earnest. During the ‘Five Years’ War’ beginning 797/1395, the Muẓaffarids of Fars were destroyed and the Jalāyirid Aḥmad b. Shaykh Uways driven from Iraq. Tīmūr’s northern frontier was an open one, and his great rival in the steppes was Toqtamïsh, Khān of the White Horde, by now supreme across the whole Qïpchaq steppe of South Russia and south-western Siberia (see above, no. 134). Tīmūr accordingly invaded Qïpchaq in 797/1395, penetrating as far as Astrakhan and Muscovy. But his main efforts were directed aganst the Islamic heartlands, where his campaigns had a cataclysmic effect on the political structures of the time. During the Indian campaign of 800/1398–9, Delhi was sacked and the end of the Tughluqids hastened (see below, no. 160, 3), facilitating in the fifteenth century the rise of independent provincial sultanates such as those of Jawnpūr, Gujarāt, Mālwa and Khāndesh (see below, Chapter Sixteen). In the west, Tīmūr’s defeat of Sultan Bāyazīd I at Ankara in 805/1402 meant the restoration for a few decades longer of many of the Anatolian beyliks absorbed by the Ottomans (see above, Chapter Twelve).

Before his death, which occurred just as he was about to leave for China, Tīmūr had divided up his territories among his sons and grandsons. The steppe tradition that an empire was not the personal property of the supreme ruler, but belonged to all male members of the ruling family, meant the parcelling-out of the Tīmūrid empire among its numerous princes, and in the absence of a clear succession principle left the field open for disputes and fragmentation. Three lines of Tīmūrids are listed above, but there were several other members of the family ruling either with varying degrees of independence or as vassals of other Tīmūrids in regions as far apart as the Caspian provinces, Kirman, and Kabul and Kandahar in eastern Afghanistan. And although possession of Tīmūr’s old capital Samarkand conferred prestige within the dynasty, it did not automatically entail headship or supremacy; thus Ḥusayn b. Manṣūr Bayqara was, in his time, the greatest ruler among the later Tīmūrids, but reigned at Herat and not Samarkand.

Once the terror inspired by Tīmūr was gone, the later Tīmūrids eventually sank to the status of local rulers in Khurasan and Transoxania, with the western lands abandoned to the rising power of Türkmen dynasties like the Qara Qoyunlu and Aq Qoyunlu (see below, nos 145, 146). At first, there were two great kingdoms, in western Persia and Iraq, and in Khurasan and Transoxania, these latter two regions being first united by Tīmūr’s son Shāh Rukh and then with his suzerainty extended over the western lands as well. Shāh Rukh’s great-nephew Abū Sa‘īd was, next to the Ottoman Muḥammad the Conqueror, the most powerful monarch of his age, although he was unable to prevent the Özbegs, the ultimate destroyers of Tīmūrid power, from raiding across the Oxus (see below, no. 153), and his campaign of 872/1468 to help the Qara Qoyunlu against the rising power of the Aq Qoyunlu leader Uzun Ḥasan, with the hope also of regaining the former western territories of the Tīmūrids, ended in disaster.

The Tīmūrids were the last great Islamic dynasty of steppe origin. After their time, the rise of powerful settled states like those of the Ottomans, the Ṣafawids and the Mughals, all employing firearms and more advanced military techniques, tilted the balance against any further large-scale invasions by horsemen from the Inner Asian steppes. The Tīmūrid period of Transoxanian and Persian history, essentially the fifteenth century, was also one of the most glorious ones of mediaeval Islamic art and culture, with outstanding schools of Persian and Chaghatay Turkish literature and of architecture, painting and book production, and with a final flowering at the court in Herat of Ḥusayn b. Manṣūr b. Bayqara, where the poets Jāmī and ‘Alī Shīr Nawā’ī and the painter Bihzad worked.

Justi, 472–5; Lane-Poole, 265–8; Sachau, 30–1, nos 78–83; Zambaur, 269–70 and Table T; Album, 50–3.

R. M. Savory, ‘The struggle for supremacy in Persia after the death of Tīmūr’, Der Islam, 40 (1964), 35–54.

H. R. Roemer, ‘Tīmūr in Iran’, ‘The successors of Tīmūr’, in The Cambridge History of Iran, VI, 42–146, with genealogical tables at p. 146.

Beatrice Forbes Manz, The Rise and Rule of Tamerlane, Cambridge 1989, with a genealogical table at p. 166.

Robert C. Grossman, ‘A numismatic “King-List” of the Timurids’, Oriental Numismatic Society Information Sheet no. 27, September 1990.

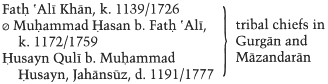

752–874/1351–1469

Eastern Anatolia, Azerbaijan, Iraq and western Persia

| 752/1351 | Bayram Khōja, vassal of the Jalāyirids in northern Iraq and eastern Anatolia |

| 782/1380 | Qara Muḥammad b. Türemish, nephew of Bayram Khōja, after 784/1382 independent of the Jalāyirids, k. 791/1389 |

| c. 792/c. 1390 | Qara Yūsuf b. Qara Muḥammad, Abū Naṣr, first reign |

| 802/1400 | Invasion of Tīmūr |

| ⊘ 809/1406 | Qara Yūsuf, second reign, d. 823/1420 |

| ⊘ (814–21/1411–18 | Pīr Budaq b. Qara Yūsuf, governor of Azerbaijan under his father’s regency) |

| ⊘ 823–41/1420–38 | Iskandar b. Qara Yūsuf, k. 841/1438 |

| (832–3/1429–30 | Abū Sa‘īd b. Qara Yūsuf, vassal of the Tīmūrids in Azerbaijan |

| ⊘ 836/1433 | Ispan (?) b. Qara Yūsuf, Tīmūrid vassal in Iraq |

| ⊘ 837/1434 | Jahān Shāh b. Qara Yūsuf, Tīmūrid vassal in eastern Anatolia) |

| ⊘ 843/1439 | Jahān Shāh b. Qara Yūsuf, up to 853/1449 as a Tīmūrid vassal |

| ⊘ 872/1467 | Ḥasan ‘Alī b. Jahān Shāh |

| ⊘ 873–4/1469 | Abū Yūsuf b. Jahān Shāh, ruler in Fars only |

| 874/1469 | Aq Qoyunlu conquest |

The confederation of the Qara Qoyunlu ‘[those with] black sheep’ arose out of Türkmen elements pushed westwards by the Mongol invasions. Their ruling family seems to have come from the Yïwa or Iwa clan of the Oghuz, and the seats of their power in the fourteenth century lay to the north of Lake Van and in the Mosul region of northern Iraq.

The confederation was in many ways similar to that of the Jalāyirids (see above, no. 142), and came to think of itself as the successor to the Jalāyirids, with their traditions and connections going back to Chingizid times. The first Qara Qoyunlu leaders were vassals of the older Türkmen line, until in 784/1382 Qara Muḥammad made himself independent of the Jalāyirids, basing his power on Tabriz in Azerbaijan and on eastern Anatolia. The greatest ruler of the dynasty, Qara Yūsuf, opposed Tīmūr, and had to flee first to the Ottomans and then to Mamlūk Syria, only returning in 809/1406 and then ending the power of the Jalāyirids in Azerbaijan and Iraq. Qara Yūsuf now undertook warfare against his Aq Qoyunlu rivals (see below, no. 146) in Diyār Bakr, against the Georgians and the later Shīrwān Shāhs (see above, no. 67, 2) in the Caucasus, and against the Tīmūrid suzerains in western Persia. Once the forceful Shāh Rukh was dead, Jahān Shāh extended his rule to Fars, Kirman and even Oman, and made the Qara Qoyunlu an imperial power, adopting for himself such titles as khān and sulṭān. Finally, he attacked the redoubtable Aq Qoyunlu ruler Uzun Ḥasan, but was defeated and lost his life. His son Ḥasan ‘Alī was unable to secure his position as leader of the Qara Qoyunlu, and killed himself in 873/1469, so that all the Qara Qoyunlu territories passed into the hands of the Aq Qoyunlu.

The constituting of the Qara Qoyunlu confederation was part of the interlude of Türkmen domination over the central part of the northern tier of the Middle East, from Anatolia to Khurasan, during the period between the decay of the Il Khānids and the rise of the Ottomans, Ṣafawids and Özbegs. Ethnically, the rule of Türkmens accelerated the process, already well advanced, whereby Azerbaijan and parts of Fars became strongly Turkish in race and speech. As to the religious affiliations of the Qara Qoyunlu, although some of the later members of the family had Shī‘ī-type names and there were occasional Shī‘ī coin legends, there seems no strong evidence for definite Shī‘ī sympathies beyond possible influences from a general climate of such sympathies among many Türkmen elements of the time.

Lane-Poole, 253; Zambaur, 257; Album, 53.

İA ‘Kara-Koyunlular’ (Faruk Sümer), with a detailed genealogical table; EI2 ‘Ḳarā-Ḳoyunlu’ (F. Sümer), with a detailed genealogical table.

R. M. Savory, ‘The struggle for supremacy in Persia after the death of Tīmūr’, 35–50.

Faruk Sümer, Kara-Koyunlular (başlangıştan Cihan-Şah’a kadar), I, Ankara 1967.

H. R. Roemer, ‘The Türkmen dynasties’, in The Cambridge History of Iran, VI, 150–74.

798–914/1396–1508

Diyār Bakr, Eastern Anatolia, Azerbaijan and, later, western Persia,

Fars and Kirman

| c. 761/c. 1360 | Qutlugh b. Ṭūr ‘Alī b. Pahlawān, Fakhr al-Dīn |

| 791/1389 | Aḥmad b. Qutlugh, nominal head of the confederation until 805/1403 |

| ⊘ 805/1403 | Qara Yoluq ‘Uthmān b. Qutlugh, Fakhr al-Dīn, de facto head of the confederation since 798/1396 |

| ⊘ 839/1435 | ‘Alī b. Qara ‘Uthmān, Jalāl al-Dīn, in dispute with his brothers Ḥamza and Ya‘qūb |

| ⊘ 841/1438 | Ḥamza b. Qara ‘Uthmān, Nūr al-Dīn, in dispute with Ya‘qūb and Ja‘far b. Ya‘qūb |

| ⊘ 848/1444 | Jahāngīr b. ‘Alī, Mu‘izz al-Dīn |

| (855–6/1451–2 | Qïlïch Arslan b. Aḥmad b. Qutlugh, in eastern Anatolia) |

| ⊘ 861/1457 | Uzun Ḥasan b. ‘Alī, Abu ’l-Naṣr |

| ⊘ 882/1478 | Sulṭān Khalīl b. Uzun Ḥasan, Abu ’l-Faṭh |

| ⊘ 883/1478 | Ya‘qūb b. Uzun Ḥasan, Abu ’l-Muẓaffar |

| ⊘ 896/1490 | Baysonqur b. Ya‘qūb, Abu ’l-Faṭh, in dispute with Masīḥ Mīrzā b. Uzun Ḥasan, k. 896/1491 |

| ⊘ 898/1493 | Rustam b. Maqṣūd b. Uzun Ḥasan, Abu ’l-Muẓaffar |

| ⊘ 902/1497 | Aḥmad Gövde b. Ughurlu Muḥammad b. Uzun Ḥasan, Abu ’l-Naṣr |

| ⊘ 903/1497 | Alwand b. Yūsuf b. Uzun Ḥasan, Abu ’l-Muẓaffar, in Diyār Bakr and then in Azerbaijan until 908/1502, d. 910/1504 |

| ⊘ 903/1497 | Muḥammadī b. Yūsuf b. Uzun Ḥasan, Abu ’l-Makārim, in Iraq and southern Persia, k. 905/1500 |

| ⊘ 905–14/1500–8 | Sulṭān Murād b. Ya‘qūb b. Uzun Ḥasan, Abu ’l-Muẓaffar, in Fars and Kirman until 914/1508, d. 920/1514 |

| ⊘ 910–14/1504–8 | Zayn al-‘Ābidīn b. Aḥmad b. Ughurlu Muḥammad, in Diyār Bakr |

| 914/1508 | Ṣafawid conquest |

The Aq Qoyunlu ‘[those with] white sheep’ were a nomadic confederation of Türkmens centred on Diyār Bakr, with their ruling stratum drawn from the ancient Oghuz clan of the Bayundur. Already in the mid-fourteenth century they were raiding the Byzantine principality of Trebizond and were able to force marriage alliances on the Greek rulers. It was from the Türkmen-Byzantine marriage of 753/1352 that there arose the real founder of the confederation’s fortunes, Qara Yoluq ‘Uthmān, and relations between the two powers remained close for a century. Unlike their rivals the Qara Qoyunlu (see above, no. 145), the Aq Qoyunlu submitted to Tīmūr, and Qara ‘Uthmān fought for him against the Ottoman Bāyazīd I at Ankara, being rewarded by the grant of Diyār Bakr. Expansion eastwards was blocked first by the Jalāyirids (see above, no. 142) and then by the Qara Qoyunlu, but Uzun Ḥasan, a military commander and statesman of genius, at last crushed Jahān Shāh in 872/1467 and incorporated many of the Qara Qoyunlu sub-tribes into his own horde, and after defeating the Tīmūrid Abū Sa‘īd was able to extend his rule as far as Khurasan and down to Iraq and the Persian Gulf shores.

Uzun Ḥasan’s prime enemy in the west was, however, the Ottomans, who were at this time mopping up the remaining beyliks of Anatolia (see above, Chapter Twelve) and pressing eastwards. Anti-Ottoman common interest made him ally with the Qaramānids (see above, no. 124), and he also tried to save Trebizond, to whose rulers he was related through his Byzantine wife Despina, from the attacks of Muḥammad the Conqueror. The Aq Qoyunlu were now a power of international significance. In 868/1464, diplomatic relations were opened up with the Ottomans’ Venetian enemies, and arms and munitions were despatched from Venice via southern Anatolia. Yet Uzun Ḥasan’s cavalrymen were no match for Ottoman firepower at Tercan (Terjān) in 878/1473, and the Aq Qoyunlu leader was crushingly defeated. His son Ya‘qūb carried on the struggle, but the dynasty went into a terminal period of division, internecine strife and succession disputes. The Qaramānids had fallen to the Ottomans, and, despite the fact that there had been a marriage link between Uzun Ḥasan and the head of the Ṣafawiyya order, Shaykh Junayd (see below, no. 148), Shī‘ī propaganda was being spread among the Sunnī Aq Qoyunlu’s Türkmen followers in eastern Anatolia. In 906/1501, Alwand was defeated by the Ṣafawid Shāh Ismā‘īl I, and the last Aq Qoyunlu, Sulṭān Murād, was forced to flee to the Ottomans. The dynasty’s rule was now finished everywhere, but had left behind in such places as Uzun Ḥasan’s capital at Tabriz a distinguished tradition of cultural and literary patronage.

Lane-Poole, 254; Zambaur, 258–9; Album, 53–4.

İA ‘Aḳ Ḳoyunlular’ (M. H. Yınanç), with a genealogical table; EI2 ‘Aḳ Ḳoyunlu’ (V. Minorsky).

R. M. Savory, The struggle for supremacy in Persia after the death of Tīmūr’, 50–65.

John E. Woods, The Aqquyunlu. Clan, Confederation, Empire. A Study in 15th/9th Century Turko-Iranian Politics, Minneapolis and Chicago 1976, with Appendix C of genealogical tables.

H. R. Roemer, in The Cambridge History of Iran, VI, 147–88.

839–1342/1435–1924

‘Arabistan, in south-western Persia

The Musha‘sha‘ī movement arose in the fifteenth century in southern Khūzistān, in the region which in more recent times has come to be known as ‘Arabistān. Although this region at the head of the Persian Gulf was ethnically Arab, it became the home of a typically Persia extremist Shī‘ī millenarian movement; and the Musha‘sha‘ family, throughout nearly 500 years of its existence, was always linked politically with the rulers of Persia rather than with those in Iraq (latterly, in fact, the Ottomans). Sayyid Muḥammad b. Falāḥ proclaimed his ẓuhūr or manifestation as the ḥijāb or ‘shield ’ of the Expected Imām, in opposition to the Qara Qoyunlu rulers of Iraq (see above, no. 145); the name Musha‘sha‘ seems to have connotations (cf. shu‘ā‘ ‘ray of light’) of illuminationism, a perceptible strain within Shī‘ism as it was to develop in Ṣafawid Persia.

During the fifteenth century, the Musha‘sha‘ were independent local rulers based on Ḥuwayza or Ḥawāza, and this was their heyday as a religio-political movement. Once the Ṣafawid Shāh Ismā‘īl I (see below, no. 148) had extended his power into Khūzistān in 920/1514, the Musha‘sha‘ were reduced to submission, and over the next centuries generally functioned as walls or governors for the Persian monarchs. At the end of the nineteenth century, their local influence was overshadowed by the rise of the rulers of Muḥammara from the Arab Banū Kalb, but the Musha‘sha‘ family nevertheless managed to survive up to the time of Riḍā Shāh Pahlawi (see below, no. 152).

Album, 54.

EI2 ‘Musha‘sha‘’ (P. Luft).

W. Caskel, ‘Ein Mahdī des 15. Jahrhunderts. Saijid Muḥammad ibn Falāḥ und seine Nachkommen’, Islamica, 4 (1931), 48–93, with a genealogical stem at p. 75.

idem, ‘Die Wall’s von Ḥuwēzeh’, Islamica, 6 (1934), 415–34, with a genealogical stem and list at pp. 424–32.

907–1135/1501–1722, thereafter as fainéants and pretenders until 1179/1765

Persia

| ⊘ 907/1501 | Ismā‘īl I b. Haydar b. Junayd, Abu ’l-Muẓaffar |

| ⊘ 930/1524 | Ṭahmāsp I b. Ismā‘īl I |

| ⊘ 984/1576 | Ismā‘īl II b. Ṭahmāsp I |

| ⊘ 985/1578 | Muḥammad Khudābanda b. Ṭahmāsp I, d. 1003/1595 or 1004/1596 |

| ⊘ 995/1587 | ‘Abbās I b. Muḥammad Khudābanda |

| ⊘ 1038/1629 | Ṣafī I, Sām Mīrzā b. Ṣafī Mīrzā |

| ⊘ 1052/1642 | ‘Abbās II, Sulṭān Muḥammad Mīrzā b. Ṣafī I |

| ⊘ 1077/1666 | Ṣafī II b. ‘Abbās II, re-enthroned in 1078/1668 as Sulaymān I |

| ⊘ 1105/1694 | Ḥusayn I b. Sulaymān I, Mulla |

| 1135/1722 | Afghan invasion |

| ⊘ 1135/1722 | Ṭahmāsp II b. Ḥusayn I, k. 1153/1740 |

| ⊘ 1145/1732 | ‘Abbās III b. Ṭahmāsp II, k. 1153/1740 |

| 1148/1736 | Nādir Shāh Afshār 1161/1748 Shāh Rukh, Afshārid, first reign |

| ⊘ 1163/1750 | Sulaymān II, Sayyid Muḥammad, grandson of Sulaymān I, at Mashhad |

| 1163/1750 | Shāh Rukh, second reign, in Khurāsān |

| ⊘ 1163–79/1750–65 | Ismā‘īl III b. Sayyid Murtadā, Abū Turāb, in Iṣfahān as a puppet of the Zands, d. 1187/1773 |

The origins of the Ṣafawids are obscure, and their elucidation is not helped by the production, by at least the first half of the sixteenth century, of an ‘official’ version of Ṣafawid genealogy and early history. It does, however, seem probable that they hailed from Persian Kurdistan, and, as Turkish speakers, they seem to be part of the Türkmen resurgence of post-Mongol times. The family headed a Ṣūfi order, the Ṣafawiyya, based on Ardabīl in Azerbaijan, originally orthodox Sunnī in complexion, but in the mid-fifteenth century the leader of the order, Shaykh Junayd, embarked on a campaign for material power in addition to spiritual authority. In the atmosphere of heterodoxy and Shī‘ī sympathies among the Türkmen of Anatolia and Azerbaijan, the Safawiyya gradually became Shī‘ī in emphasis.

The political ambitions of the first Ṣafawids brought them up against the other Türkmen powers of eastern Anatolia, Iraq and Persia, but in 905/1501 Ismā‘īl I defeated the Aq Qoyunlu (see above, no. 146), seized Azerbaijan and brought the whole of Persia under his control during the ensuing ten years, and thus established the Ṣafawid theocracy, for not only did Ismā‘īl and his successors claim to be lineal descendants of ‘Alī through the Seventh Imām Mūsā al-Kāẓim, but Ismā‘īl, at least, on the evidence of his poetry, also claimed divine status in the extremist Shī‘I ghulāt tradition. Their Türkmen tribal followers, the so-called Qïzïl Bash or ‘red heads’ (from the red caps which they wore) thus owed a spiritual as well as a political allegiance. Shī‘ism was imposed as the state religion on a country which up until then had been, at least officially, predominantly Sunnī. The Ṣafawid period is thus of supreme importance in Persian history because of this consolidation of Shī‘ism there; in the process, Persia acquired a new sense of solidarity and nationhood which enabled her to survive into modern times with her national spirit and the integrity of Persian territory substantially unimpaired.

Militarily, the early Safawids had to face the strenuous hostility of their Sunnī neighbours, the Ottomans in the west and the Özbegs in the north-east. On the north-eastern frontier, the Shāhs just managed to hold their own, with cities like Herat, Mashhad and Sarakhs frequently changing hands; but Türkmen incursions for plunder and slaves continued well into the nineteenth century. The Ottomans were especially dangerous, being at the peak of their military strength in the sixteenth century. Sultan Selīm I’s victory over the Ṣafawids at Chāldirān in 920/1514 was a triumph of logistics and superior firepower for the Ottomans (like the Mamlūks of Egypt, the Ṣafawids were slow to adopt artillery and handguns), and also impaired the Ṣafawids’ supporters’ beliefs in the divine invincibility of their masters. Soon afterwards, Kurdistan, Diyār Bakr and Baghdad passed into Ottoman hands, and Azerbaijan was frequently invaded; later, the Ṣafawid capital was moved from vulnerable Tabriz to Qazwīn and then to Iṣfahān.

The reign of Shāh ‘Abbās I, near-contemporary of such great rulers as Elizabeth I of England, Philip II of Spain, Ivan IV (‘The Terrible’) of Russia and the Mughal emperor Akbar, marks the apex of Ṣafawid military power and also Ṣafawid culture and civilisation, some of whose manifestations are visible in the architectural glories of Iṣfahān. During his reign, the Ottomans were ejected from Azerbaijan, and Persian control over the Caucasus and the Gulf strengthened. Diplomatic contacts with Europe were established (although a Ṣafawid-Euro-pean grand alliance against the Ottomans never materialised), and commercial and cultural contacts grew. In order to counteract the influence in the state of the Qïzïl Bash, ‘Abbās recruited Georgian and Circassian converts as slave guards, and favoured the formation of a group of Türkmen owing allegiance to himself personally and not to the tribal chiefs (the Shāh seven or ‘Lovers of the Shāh’).

After the death of Shāh ‘Abbās II in 1077/1666, there was a perceptible decline in the personal qualities of the rulers. Ṣafawid authority had at times stretched as far as eastern Afghanistan, but Sunnī Afghan sentiment was opposed to the strongly Shī‘ī policies of the Shāhs, and in the early eighteenth century the governor for the Ṣafawids there, Mīr Uways, declared himself independent. In 1135/1722, his son Maḥmūd invaded Persia; Ṣafawid resistance collapsed, and for several years until the rise of Nādir Shāh Afshār (see below, no. 149), the Ghilzay Afghans occupied much of Persia. The subsequent holders of power in Persia at times felt a need to nominate Ṣafawid descendants or claimants as puppet rulers, but the effective rule of the dynasty disappeared with Ṭahmāsp II.

Justi, 479; Lane-Poole, 255–9; Zambaur, 261–2; Abum, 54–7.

EI2 ‘Ṣafawids. 1. Dynastic, political and military history’ (R. M. Savory).

J. R. Perry, ‘The last Ṣafavids, 1722–1773’, Iran, JBIPS, 9 (1971), 59–69.

Roger Savory, Iran under the Safavids, Cambridge 1980.

H. R. Roemer, ‘The Safavid period’, in The Cambridge History of Iran, VI, 189–350.

1148–1210/1736–96

Persia

| ⊘ 1148/1736 | Nadr Qulī b. Imām Qulī, Tahmāsp Qulī, Nādir Shāh Afshār, since 1144/1732 regent for Shāh Ṭahmāsp II |

| ⊘ 1160/1747 | ‘Alī Qulī b. Muḥammad Ibrāhīm b. Imām Qulī, ‘Ādil Shāh, k. 1160/1747 |

| ⊘ 1161/1748 | Ibrāhīm b. Muḥammad Ibrāhīm, in central and western Persia |

| ⊘ 1163/1750 | Shāh Rukh b. Ridā Qulī b. Nādir Shāh, in Khurasan, first reign, deposed 1163/1750 |

| ⊘ 1163/1750 | Shāh Rukh, second reign |

| 1168–1210/1755–96 | Shāh Rukh, third reign, at first as the puppet of the Abdālī or Durrānī Afghans |

| 1210/1796 | Succession of the Qājārs |

| (1210–18/1796–1803 | Nādir Mīrzāb. Shāh Rukh, holder of power in Mashhad) |

Nadr or Nādir was a chieftain of the Afshār, a Türkmen tribe settled in northern Khurasan; it was in this home territory that he later constructed his stronghold and treasury, the Qal‘at-i Nādirī. In this period of Ṣafawid decay, when much of Persia was in the hands of the Ghilzays, the national unity of Persia, which had been built up by the earlier Ṣafawids, seemed likely to disintegrate. It was to be Nādir‘s achievement temporarily to restore the territorial integrity of Persia, albeit at the price of leaving the country financially and economically exhausted. His ascent to power began through service with the ineffective Ṣafawid Shāh Ṭahmāsp II (whence the name which he adopted, ‘slave of Ṭahmāsp’). He began systematically to clear the Afghan invaders from Persia, and when by 1140/1727 this had been achieved, the Shāh rewarded him wth the governorship of Khurasan, Kirman, Sistan and Māzandarān. With such extensive lands under his personal control, Nādir began to act like an independent ruler, now minting his own coins. Turning to external enemies, he drove the Ottomans out of Azerbaijan and Kurdistan, and penetrated through the Caucasus as far as Dāghistān. Ṭahmāsp’s conclusion of a treaty with Turkey and Russia unfavourable to Persia’s interests provided Nādir with a pretext to depose him, setting up another Ṣafawid prince as puppet ruler, until in 1148/1736 he was himself proclaimed Shāh. Nādir seems at this point to have sought an end to the ancient Shī‘ī-Sunnī hostility between Persia and Turkey, and he announced the abandonment of Twelver Shī‘īsm as the state religion and the establishment instead of much-attenuated form of Shī‘ism whose spiritual head was to be the Sixth Imām, Ja‘far al-Ṣādiq; in practice, this conciliatory move pleased no-one and did not bring about détente with the Ottomans.

The expense of continual warfare drove Nādir into his brilliantly successful Indian campaign of 1151–2/1738–9, as a result of which the Mughal emperor Muḥammad Shāh (see below, no. 175) had to cede all his provinces north and west of the Indus and to pay an enormous tribute; because of this last, Nādir declared the people of Persia exempt from taxation for three years. An assassination attempt on him in 1154/1741, in which Nādir suspected the complicity of his son Riḍā Qulī, caused a deterioration in his character, so that his policies became more and more cruel and erratic. Rebellions broke out in the provinces against his exactions, and in 1160/1747 a group of Afshār and Qājār Türkmen chiefs finally murdered him. Two of his nephews reigned briefly, and then his blinded grandson Shāh Rukh ruled as a puppet of military commanders in Khurasan, until Agha Muḥammad Qājār (see below, no. 151) extended his power eastwards from northern Persia in 1210/1796 and ended what remained of the authority of the Afshārids.

Lane-Poole, 257–9; Zambaur, 261; Album, 57–8.

EI2 ‘Nādir Shāh Afshār’ (J. R. Perry).

Peter Avery, ‘Nādir Shāh and the Afsharid legacy’, in The Cambridge History of Iran. VII. From Nadir Shah to the Islamic Republic, Cambridge 1991, 3–62.

1164–1209/1751–94

Persia, excepting Khurasan

| ⊘ 1164/1751 | Muḥammad Karīm Khān b. Inaq Khān, as wakīl or regent for Ismā‘īl III Safawī |

| ⊘ 1193/1779 |

|

| ⊘ 1193/1779 | Muḥamad Ṣādiq b. Inaq, in Shiraz |

| ⊘ 1195/1781 | ‘Alī Murād b. Allāh Murād or Qaydar Khān, in Isfahan |

| ⊘ 1199/1785 | Ja‘far b. Muḥammad Ṣādiq, at first in Isfahan, latterly in Shiraz |

| ⊘ 1204–9/1789–94 | Lutf ‘Alī b. Ja‘far, in Shiraz |

| 1209/1794 | Succession of the Qājārs |

In the chaos which followed Nādir Shāh’s death, various military chiefs seized power in the provinces of Persia. His Afghan commander Aḥmad Abdālī founded in Kandahar an important Afghan state, whose territories included Nādir’s conquests in north-western India (see below, no. 175). In Khurasan, the Afshārid Shāh Rukh retained a precarious power as the puppet of local commanders. In the Caspian provinces, the Qājārs maintained their power-base (see below, no. 151), while in Azerbaijan another of Nādir’s Afghan generals, Āzād, established himself. In southern Persia, the main force was initially the Bakhtiyārī leader ‘Alī Mardān, who had taken Isfahan and raised to the throne there a fainéant Ṣafawid, Ismā‘īl III (1163/1750) (see above, no. 148). ‘Alī Mardan’s lieutenant and sardār or commander of the forces was Muḥammad Karīm Zand, from a minor tribe of Lurs in the central Zagros Mountains; and when ‘Alī was murdered, Muḥammad Karīm made himself sole ruler in southern Persia.

He still had a lengthy struggle with the Qājār Muḥammad Ḥasan Khān before his authority over the greater part of Persia outside Khurasan was made firm. Muḥammad Karīm never himself assumed the title of Shāh, but reigned from Shiraz as wakīl al-dawla or regent for Ismā‘īl III. His reign of almost thirty years was one of clemency and moderation, and the land flourished under his enlightened rule; among other things, commercial relations with Britain via Bushire (Būshahr) on the Persia Gulf were encouraged. But his death was the signal for disastrous succession disputes to break out within the Zand family. ‘Alī Murād finally secured the throne, but died soon afterwards, and in the reign of Ja‘far the power of the Zands’ rivals the Qājārs grew until the Zands had to abandon Iṣfahān to them. The last Zand, Lutf ‘Alī Khān, a popular ruler and an able general, took up arms against the Qājārs and was successful for a while. But in 1209/1794 he was captured at Kirmān by Agha Muḥammad Khān Qājār and brutally murdered; the whole of Persia now became united under one monarch for the first time since the brief career of Nādir Shāh and the heyday of the Ṣafawids.

Lane-Poole, 260, 262; Zambaur, 261, 264; Album, 58–9.

John R. Perry, Karim Khan Zand. A History of Iran, 1747–1779, Chicago and London 1979, with a genealogical table at p. 296.

idem, ‘The Zand dynasty’, in The Cambridge History of Iran, VII, 63–103, and Gavin R. G. Hambly, ‘Āghā Muḥammad Khān and the establishment of the Qājār dynasty’, in ibid., 104–26, with a genealogical table at p. 961.

1193–1344/1779–1925

Persia

|

|

| ⊘ 1193/1779 | Agha Muḥammad b. Muḥammad Ḥasan, ruler in northern and central Persia, after 1209/1794 ruler in southern Persia also, after 1210/1796 ruler in Khurasan also |

| ⊘ 1212/1797 | Fath ‘Alī b. Ḥusayn Qulī, Bābā Khān |

| ⊘ 1250/1834 | Muḥammad b. ‘Abbās Mīrzā b. Fatḥ ‘Alī |

| ⊘ 1264/1848 | Nāṣir al-Dīn b. Muḥammad |

| ⊘ 1313/1896 | Muẓaffar al-Dīn b. Nāṣir al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 1324/1907 | Muḥammad ‘Alī b. Muẓaffar al-Dīn, d. 1343/1925 |

| ⊘ 1327–44/1909–25 | Aḥmad b. Muḥammad ‘Alī, d. 1347/1929 |

| 1344/1925 | Succession of the Pahlawīs |

The Qājār tribe of Türkmens had probably been settled near Astarābād in the Caspian coastlands since Mongol times; later, they were one of the seven great Türkmen tribes supporting the early Ṣafawids and comprising the Qïzïl Bash. With the disintegration of the Ṣafawid empire in the early eighteenth century, the Qājārs began to play a more-than-local part in Persian affairs. The chiefs of the Qoyunlu clan of the Qājārs expanded across northern Persia in an endeavour to take over Nādir Shāh’s western territories, but it was not until 1209/1794 that Agha Muḥammad was finally victorious over the Zands (see above, no. 150); soon afterwards, Persian suzerainty was re-established, albeit temporarily, over Georgia, and the last Afshārid removed from Khurasan (see above, no. 149). The frightful Agha Muḥammad, whose excesses are doubtless in part explicable by the fact that, as a boy, he had been castrated by Nādir’s nephew ‘Ādil Shāh, was thus the founder of the dynasty under which Persia was to move definitely into the modern world, acquiring an important strategic and economic rôle in the international states-system. It was also under the first Qājār Shāh that Tehran (Tihrān), previously a town of only modest importance, became the capital (1200/1786); in this way began the movement of all life towards the centre which has characterised modern Persia.

Regular diplomatic relations with the European powers date from Fath ‘Alī Shāh’s reign, when Persia was courted by Britain on one side and by Napoleonic France on the other on account of her strategic position across the routes to the East. A by-product of this attention from the West was the introduction of European techniques and training into the Persian army. This was all the more necessary for Persia in that, during the nineteenth century, Imperial Russia, advancing now into the Caucasus and into Central Asia, was a continuing threat; by the humiliating Treaty of Turkmanchay in 1243/1828, Persia had had to relinquish all claims to territories in eastern Armenia and the Caucasus and had had to facilitate Russian commercial penetration of Persia. For their part, the Qājārs were for long reluctant to renounce the heritage of eastern conquests made by the Ṣafawids and by Nādir, and disputes with Afghanistan continued until the later nineteenth century (see below, no. 180).

Through the mutual rivalries of the European powers and the astuteness of Nāṣir al-Dīn Shāh, the geographically-compact land of Persia was much more successful than the disparate Ottoman empire in maintaining its territorial integrity. Nevertheless, the cost of warfare and royal extravagance were plunging the nation deeply into foreign indebtedness, thereby increasing the economic stranglehold of the European creditor nations. During the reign of Muẓaffar al-Dīn Shāh, there arose a movement demanding some degree of political liberalism and the granting of a constitution, demands which had to be met in 1906. The prestige and power of the Qājārs were now perceptibly failing. During the First World War, Persia remained officially neutral, but despite this, Turkish, Russian and British troops fought over her soil, and, at the end of the war, various local rebellions and separatist movements arose in the provinces. Accordingly, it was not difficult for a decisive military leader like Riḍā Khān to get the National Assembly to depose the Qājārs in 1925 (see below, no. 152).

Lane-Poole, 260; Zambaur, 261–3; Album, 59–61.

EI2 ‘Kādjār’ (A. K. S Lambton).

Gavin R. G. Hambly, ‘Āghā Muḥammad Khān and the establishment of the Qājār dynasty’, idem, ‘Iran during the reigns of Fath ‘Alī Shāh and Muḥammad Shāh’, and Nikki Keddie and Mehrdad Amanat, ‘Iran under the later Qājārs, 1848–1922’, in The Cambridge History of Iran, VII, 104–212, with a genealogical table at p. 962.

1344–98/1925–79

Persia

| ⊘ 1344/1925 | Riḍā b. ‘Abbās ‘Alī, d. 1365/1944 |

| ⊘ 1360–98/1941–79 | Muḥammad b. Riḍā, d. 1399/1980 |

| 1398/1979 | Islamic Republic |

Riḍā Khān was a soldier in the Persian army who had participated in the coup d’état of 1921 which began the process of the ousting of the Qājārs (see above, no. 151). In December 1925, the Majlis or National Assembly voted him in as Shāh in succession to Aḥmad Qājār, who had left the country two years previously; Riḍā had already assumed the family name of Pahlawī, redolent of ancient Persian glories.

Riḍā’s sixteen-year rule in many ways resembled other military dictatorships which emerged in both the Middle East (such as that of Muṣṭafā Kemāl Atatürk in Turkey) and Europe. His driving aim was the modernisation of his country so that it could stand on its own feet against outside pressures, and this involved the centralisation of power and the bureaucratisation of many aspects of Persian life. During his reign, the country made immense strides in industrialisation, the provision of modern communications and the introduction of modern, secular educational and legal systems; but all this was at the price of individual liberty and freedom of expression. Riḍā Shāh’s pro-German stance in the early part of the Second World War led to his deposition under British and Russian pressure and his replacement by his son Muḥammad. Muḥammad wished to continue his father’s policies, but was involved in disputes with his Majlis and with both nationalist and communist factions. Educational and land reforms were nevertheless successful while Persia was benefiting from rising oil revenues, but after 1975 lower oil prices brought inflation and economic hardship to the country. Popular discontent was utilised by a wide spectrum of opposition forces, including the Shī‘ī clergy, and, unwilling to use military force against his own people, the Shāh, already very sick, left his throne for exile in January 1979. The Pahlawī monarchy was then replaced by an Islamic Republic hostile to virtually everything which the Pahlawīs had sought to achieve.

EI2 ‘Muḥammad Riḍā Shāh Pahlawī’ (R. M. Savory), ‘Riḍā Shāh’ (G. R. G. Hambly).

Gavin R. G. Hambly, ‘The Pahlavī autocracy: Rizā Shāh, 1921–1941’, idem, ‘The Pahlavī autocracy: Muḥammad Rizā Shāh, 1941–1979’, in The Cambridge History of Iran, VII, 213–93.